Abacus Federal Savings

description: community bank primarily serving the Chinese-American community in New York City, known for its personal banking services, small business loans, and involvement in a notable legal case featured in the documentary "Abacus: Small Enough to Jail"

1 results

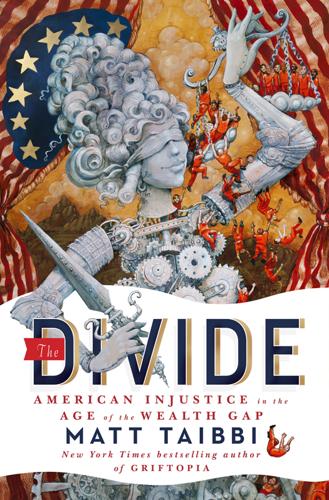

The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap

by

Matt Taibbi

Published 8 Apr 2014

So surely one of these banks in those big skyscrapers a few blocks south of here must be the one on trial. Nope. In the end, the one bank to get thrown on the dock was not a Wall Street firm but one housed in the opposite direction, a little to the north—a tiny family-owned community bank in Chinatown called Abacus Federal Savings Bank. As a symbol of the government’s ambitions in the area of cleaning up the financial sector, Abacus presents a striking picture. Instead of a fifty-story glass-and-steel monolith, Abacus is housed in a dull gray six-story building wedged between two noodle shops at the southern end of New York’s legendary Bowery, once the capital of American poverty.

…

Which offending megabank, lender, or ratings agency offered the best chance to score a high-profile symbolic prosecution? Who would be first on the dock? The federal government never really stepped up to the plate. The job was left to the states, and even they could come up with only one target. That target, it turned out, was Abacus Federal Savings Bank. There were a million ironies in the choice of this particular institution, but one of the most striking was that the case grew out of an incident that the bank itself had reported to the authorities. On December 11, 2009, Vera Sung, the forty-three-year-old daughter of the bank’s founder and a former New York City prosecutor, was on the sixth floor of the Abacus offices.

…

Some of these individual employees, like Yu, became embroiled in local criminal investigations, which seemed entirely appropriate, even to the Sungs. But as far as the company itself went, the OTS didn’t recommend a fine. And though the federal regulator had the power to force the Sung family to sell the business, or demand wholesale changes to the executive management of Abacus Federal Savings, it did neither. The system seemed to work the way Wall Street and the financial community is always telling us things can work: companies self-report their ethical issues, then work together with regulators to correct problems while preserving viable, job-creating businesses going forward.