Game Over Press Start to Continue

by

David Sheff

and

Andy Eddy

Published 1 Jan 1993

As always, Nintendo did best of all, though it is impossible to calculate exactly how much it made from “Tetris,” since there is no way to measure accurately how much “Tetris” contributed to the success of Game Boy. Three million “Tetris” cartridges for the NES were sold, plus all those Game Boy units. Once a customer bought one, Nintendo could sell more games, an average of three a year, at $35 a pop. Not counting Game Boy, “Tetris” brought Nintendo at least $80 million. Counting Game Boy, the figure is in the billions of dollars (in both 1991 and 1992, Game Boy earned nearly $2 billion). Alexey Pajitnov made very little money directly from “Tetris” royalties or advances. Elorg had made and then canceled a side deal that would have granted him the “Tetris” merchandising rights (Nintendo eventually got them, too), so he ended up getting nothing on the “Tetris” watches, clocks, board games, and the like.

…

In his next telex to the Soviets, sent on November 5, 1986, Stein offered a firm deal: the Russians would get 75 percent of whatever he collected for “Tetris.” This sum would be a percentage of gross sales. He also offered a $10,000 advance. Pajitnov responded favorably to the offer in a telex on November 13. Signed by the Computer Center’s Evtushenko, it said that the Academy of Science was ready to transfer the copyright to Andromeda. In another telex, Stein had offered to pay the Computer Center, in part, with Commodore computers, and the Soviets agreed to this as well. They also noted that the deal was for the IBM-compatible version of “Tetris” only; they would consider non-IBM versions of “Tetris” in the future. Alexey Pajitnov now claims he indicated only that the deal sounded good.

…

As Nintendo has known since last year, Tengen received all NES rights to the game ‘Tetris’ in early 1988. These rights are, in Tengen’s view, clear and unequivocal.…” Howard Lincoln offered to discuss things further, but by then, on April 13, Atari Games had filed an application for a copyright on the “audiovisual work, the underlying computer code and the soundtrack” for “Tetris” for the Nintendo system. Atari did not inform the Copyright Office that its version of “Tetris” was simply a spruced-up version of Alexey Pajitnov’s game, or that Nintendo had informed Atari that it held the exclusive rights to the game.

All Your Base Are Belong to Us: How Fifty Years of Video Games Conquered Pop Culture

by

Harold Goldberg

Published 5 Apr 2011

FALLING BLOCKS, RISING FORTUNES Based on long interviews I had with Henk Rogers, early Nintendo maven and spokesperson Howard Phillips, Alexey Pajitnov, and Minoru Arakawa, and conversations with Jason Kapulka and others who spoke on background. 1 Russia was not an easy place to live while Pajitnov was growing up. See Hedrick Smith’s The Russians and The New Russians, both landmark tomes, to read more about the tenor of the times during the Soviet Union’s heyday and what came after. 2 Vadim Gerasimov tells his side of the Tetris story at length at http://vadim.oversima.com/Tetris.htm. 6. THE RISE OF ELECTRONIC ARTS Based on interviews I conducted with Trip Hawkins, Ray Tobey, Mark Cerny, and Jason Rubin, as well as conversations with Steven L.

…

On the other hand, Jeff saw limitless possibilities in the city planning game. He couldn’t contain his ebullience. He wasn’t talking fonts anymore; he was talking games to anyone who would lend an ear. Everything looked brighter then. Just as Henk Rogers envisioned the unlimited potential in Alexey Pajitnov’s Tetris, Braun saw the potential in SimCity (the game’s new name). He and Wright went on to retrieve the rights from Broderbund and to raise $50,000 to start their new venture. To name their company, Braun decided to hold a contest, asking friends and family for a two-syllable name that meant nothing (like Kodak or Sony), but sounded good when you said it.

…

Much like the early days of the music industry, when R&B stars and master bluesmen received a Cadillac in lieu of millions in royalties, the videogame world was still full of carpetbaggers and snake oil salesmen. These Bastards of the Universe were game developer manipulators extraordinaire. And young Alexey Pajitnov, the man responsible for the biggest game phenomenon since Miyamoto’s Super Mario Bros., was about to be ripped off. If this had happened to a US developer like Nolan Bushnell, he would have yelled and moaned about unscrupulous business practices that were akin to torture. But Alexey Pajitnov, born in Soviet era Moscow, to middle class parents who were writers, wasn’t like that. Pajitnov was steeped in popular art from an early age, and he respected it.

Marx at the Arcade: Consoles, Controllers, and Class Struggle

by

Jamie Woodcock

Published 17 Jun 2019

c=y. 46Quoted in Keith Stuart, “Richard Bartle: We Invented Multiplayer Games as a Political Gesture,” Guardian, November 17, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/nov/17/richard-bartle-multiplayer-games-political-gesture. 47Stuart, “Richard Bartle.” 48Quoted in Stuart, “Richard Bartle.” 49Stephen Kline, Nick Dyer-Witheford, and Greig de Peuter, Digital Play: The Interaction of Technology, Culture, and Marketing (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003), 96. 50“Video Game History Timeline.” 51Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 13. 52Daniel Joseph, “Code of Conduct: Platforms Are Taking over Capitalism, but Code Convenes Class Struggle as Well as Control,” Real Life, April 12, 2017, http://reallifemag.com/code-of-conduct. 53Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 13. 54Mary Aitken, The Cyber Effect: A Pioneering Cyberpsychologist Explains How Human Behaviour Changes Online (London: John Murray, 2016). 55Drew Robarge, “From Landfill to Smithsonian Collections: ‘E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial’ Atari 2600 Game,” Smithsonian, December 15, 2014, http://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/landfill-smithsonian-collections-et-extra-terrestrial-atari-2600-game. 56Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 14. 57Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 14. 58Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 15. 59Dal Yong Jin, Korea’s Online Gaming Empire (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010). 60Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 16. 61Nintendo, “Historical Data: Consolidated Sales Transition by Region,” last modified October 26, 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20171026163943/https://www.nintendo.co.jp/ir/finance/historical_data/xls/consolidated_sales_e1703.xlsx. 62Joseph, “Code of Conduct.” 63Nintendo, “Historical Data.” 64Emily Gera, “This Is How Tetris Wants You to Celebrate for Its 30th Anniversary,” Polygon, May 21, 2014, www.polygon.com/2014/5/21/5737488/tetris-turns-30-alexey-pajitnov. 65“Yearly Market Report,” Famitsu Weekly, June 21, 1996. 66Nintendo, “Historical Data.” 67“Video Game History Timeline.” 68Sony Computer Entertainment, “PlayStation Cumulative Production Shipments of Hardware,” May 24, 2011, https://web.archive.org/web/20110524023857/http://www.scei.co.jp/corporate/data/bizdataps_e.html. 69Nintendo, “Historical Data.” 70“Video Game History Timeline.” 71Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 20. 72Sony Computer Entertainment, “PlayStation 2 Worldwide Hardware Unit Sales,” November 1, 2013, https://web.archive.org/web/20131101120621/http://www.scei.co.jp/corporate/data/bizdataps2_sale_e.html. 73Nintendo, “Historical Data.” 74Colin Moriarty, “Vita Sales Are Picking Up Thanks to PS4 Remote Play,” IGN, November 17, 2014, http://uk.ign.com/articles/2014/11/17/vita-sales-are-picking-up-thanks-to-ps4-remote-play. 75Xbox.com, “Gamers Catch Their Breath as Xbox 360 and Xbox Live Reinvent Next-Generation Gaming,” May 10, 2006, https://web.archive.org/web/20070709062832/http://www.xbox.com/zh-SG/community/news/2006/20060510.htm. 76Eddie Makuch, “E3 2014: $399 Xbox One Out Now, Xbox 360 Sales Rise to 84 million,” GameSpot, June 9, 2014, https://web.archive.org/web/20141013194652/http://www.gamespot.com/articles/e3-2014-399-xbox-one-out-now-xbox-360-sales-rise-to-84-million/1100-6420231/. 77“Video Game History Timeline.” 78Sony Computer Entertainment, “Q4 FY2014 Consolidated Financial Results Forecast (Three Months Ended March 31, 2015),” April 30, 2015, www.sony.net/SonyInfo/IR/financial/fr/14q4_sonypre.pdf. 79Nintendo, “Historical Data.” 80“Video Game History Timeline.” 81“Video Game History Timeline.” 82Nintendo, “Historical Data.” 83“Dedicated Video Game Sales Units,” Nintendo, January 31, 2018, www.nintendo.co.jp/ir/en/finance/hard_soft/index.html. 84Aernout, “Minecraft Sales Reach 144 Million Across all Platforms; 74 Million Monthly Players,” Wccftech, January 22, 2018, https://wccftech.com/minecraft-sales-144-million/. 85Eugene Kim, “Amazon Buys Twitch for $970 Million in Cash,” Business Insider, August 25, 2014, www.businessinsider.com/amazon-buys-twitch-2014-8. 86Craig Smith, “50 Interesting Fortnite Stats and Facts (November 2018) by the Numbers,” DMR, November 17, 2018, https://expandedramblings.com/index.php/fortnite-facts-and-statistics/.

…

It sold 64 million units, and with the launch of the Game Boy Color in 1998 (after which the sales numbers were only released as combined figures), then sold a total of just under 120 million units.63 The original Game Boy came bundled with Tetris, the most successful videogame to date with an estimated 170 million sales.64 The game was originally created by Alexey Pajitnov and was leaked out from the Soviet Union—an ironic success considering it came from the losing side of the Cold War. That same code traveled a far way to the staircase of my family friend’s home so that I could play the game. Another successful puzzle game, Solitaire, was bundled with Windows 3.0 on the PC in 1990, leading to millions of new players, many of whom may have never played on consoles.

…

I also, for reasons I never quite understood, explored the Fantasy World of that anthropomorphized egg with a hat, Dizzy. Then there were the videogames like the platformer Duke Nukem, in which I shot my way through levels. All of these games were passed along by someone who programmed computers for a living. I was taught to play Tetris on a Nintendo Game Boy while sitting on the staircase of a family friend’s home. Another friend taught me to play console games, introducing me to Sonic, Mario, and others. I remember sitting on the floor, poring over the paper manuals while Civilization installed, wondering whether the installer had crashed or if the loading bar could really take so long.

Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked

by

Adam L. Alter

Published 15 Feb 2017

This sense of hardship is an ingredient in many addictive experiences, including one of the most addictive simple games of all time: Tetris. — In 1984, Alexey Pajitnov was working at a computer lab at the Russian Academy of Science in Moscow. Many of the lab’s scientists worked on side projects, and Pajitnov began working on a video game. The game borrowed from tennis and a version of four-piece dominoes called tetrominoes, so Pajitnov combined those words to form the name Tetris. Pajitnov worked on Tetris for much longer than he planned because he couldn’t stop playing the game. His friends remember him chain-smoking and pacing back and forth along the lab’s polished concrete floors.

…

The addict self wants more power and more speed, easier accessibility, the latest and greatest. So I pat my non-addict self on the back and say, ‘good job’—you didn’t go and buy the new iPhone; you haven’t upgraded your computer.” — Not everyone avoids temptation so assiduously. Like Alexey Pajitnov thirty years earlier, an Irish game designer named Terry Cavanagh played one of his own games incessantly. Cavanagh is a prolific designer, but he’s best known for a game called Super Hexagon. The game belongs to a genre known as “twitch” games, because it requires you to develop almost superhuman reflexes and motor responses.

…

Wilson and others, “Just Think: The Challenges of the Disengaged Mind,” Science 345, no. 6192 (July 2014): 75–77. In 1984, Alexey: On Pajitnov and Tetris: Jeffrey Goldsmith, “This Is Your Brain on Tetris,” Wired, May 1, 1994, archive.wired.com/wired/archive/2.05/tetris.html; Laurence Dodds, “The Healing Power of Tetris Has Its Dark Side,” Telegraph, July 7, 2015, www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/video-games/11722064/The-healing-power-of-Tetris-has-its-dark-side.html; Guinness World Records, “First Videogame to Improve Brain Functioning and Efficiency: Tetris,” n.d., www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/first-video-game-to-improve-brain-functioning-and-efficiency; Richard J.

Fun Inc.

by

Tom Chatfield

Published 13 Dec 2011

This perfection is perhaps most clearly visible when it takes on a distinctly unreal form, and one of the most distinctively Platonic forms any game has ever achieved can be found in what would be many people’s nomination for the greatest single-player game of all time, Tetris. Devised in 1984 by the Russian computer scientist Alexey Pajitnov, Tetris features just seven pieces, each composed of four blocks (collectively known as ‘tetriminoes’). The player has to fit them together into a perfectly solid structure as they fall one by one down the screen in a random, unending sequence. The only method of control is rotation and horizontal motion.

…

It’s a perfect demonstration of the ability of digital media to give an unprecedented form to a very ancient human fascination; and to generate the kind of complexity that in the days before computers could only come from locking horns with another person. Why, though, is Tetris’s brand of complexity quite so enjoyable? Part of the answer lies, once again, in its combination of great sophistication with immaculate simplicity. You can work out how to play Tetris in seconds. But the challenge it represents is not just hard, but fiendish. Mathematically speaking, it’s known as an NP-hard problem (which stands for a ‘non-deterministic polynomial hard’ problem). In practice this means that there is no way of ‘solving’ Tetris in any conceivable amount of time by generalising from a set of rules. The optimum way to play can only be understood by an exhaustive analysis of every possible move available at any particular moment in time.

…

And yet this simple creation has outsold the biggest movie blockbusters, made more money than the most expensive artworks, and accounted for more human hours than even the most compelling soap operas, thanks to 70 million global sales of the original and several times as many sales again of its clones, sequels and variations. In a sense, Pajitnov didn’t so much invent Tetris as discover it. The game is based on an ancient Roman puzzle involving pieces composed of five squares (known as pentominos), itself based on Greek and other more ancient forms of play. Crucially, though, Tetris translated a sophisticated mathematical recreation into real time and into the tiny universe of a computer, where score can be kept and pieces thrown at the player in an endless stream. It’s a perfect demonstration of the ability of digital media to give an unprecedented form to a very ancient human fascination; and to generate the kind of complexity that in the days before computers could only come from locking horns with another person.

Hacking Vim 7.2

by

Kim Schulz

Published 29 Apr 2010

If you want to play this fine game, then you can find the script and installation instructions on the Vim online community site at this address: http://www.vim. org/scripts/script.php?script_id=211. [ 205 ] Vim Can Do Everything Tetris The final game for Vim that I am going to mention in this appendix is a real classic—Tetris, where blocks of different sizes and shapes fall down and need to be placed properly to produce complete rows. This game can be dated back to 1985; the Russian Alexey Pajitnov designed and created it. Since then, the game has been implemented for almost any platform, and in hundreds of different variations over the same theme. In 2002, Gergely Kontra decided to implement this game in Vim script and this turned into yet another fine implementation of this classic game.

…

Printing longer lines Debugging Vim scripts Distributing Vim scripts Making Vimballs [ iv ] 175 175 176 176 177 178 180 180 182 182 183 183 185 186 189 190 Table of Contents Remember the documentation Using external interpreters Vim scripting in Perl Vim scripting in Python Vim scripting in Ruby Summary 191 194 195 196 198 199 Appendix A: Vim Can Do Everything 201 Appendix B: Vim Configuration Alternatives 215 Index 223 Vim games Game of Life Nibbles Rubik's cube Tic-Tac-Toe Mines Sokoban Tetris Programmers IDE Mail program Chat with Vim Using Vim as a Twitter client Tips for keeping your vimrc file clean A vimrc setup system Storing vimrc online [v] 201 202 202 203 204 204 205 206 206 210 211 212 215 217 221 Preface Back in the early days of the computer revolution, system resources were limited and developers had to figure out new ways to optimize their applications.

…

See STEVIE STEVIE 9 suffixadd function 62 sum function 170 syntax coloring 142, 143, 147 syntax-color schemes 141 syntax regions 143-146 T tabs, Vim modifying 33-37 tag browser 208 tag list generators about 80 Ctags 80 Hdrtags 80 Jtags 80 Ptags 80 Vtags 80 tag lists about 80 taglist navigation 83 uses 83 using 80-82 taglist.vim 83 templates abbreviations, using 76, 77 about 74 snippets, with snipMate script 78, 79 template files, using 74, 75 Tetris 206 [ 226 ] text, formatting about 121 headlines, marking 125, 126 lists, creating 127-129 text, aligning 124 text, putting into paragraphs 122, 123 The Mail Suite (TMS) 210 Tic-Tac-Toe 204 Tidy, external formatting tools 138 TwitVim 212 U undo branching about 98 using 103-106 unnamed register 100 V variables about 153 dictionary 153 funcref 153 list 153 number 153 string 153 v:folddashes variable 109 v:foldend variable 109 v:foldstart variable 109 vi 9 vi compatibility 14, 15 Vile about 13 features 13 Vim about 7, 11 advanced formatting 121 autocompletion 84 charityware license 15 color scheme, changing 21 command line buffer 26 configuration files 18 download link 8 editor area, personalizing 37 extensibility 141 features 12 fonts, changing 20 hidden markers 71 mail program 210 marks, adding 68 matching 22 menu, adding 29-32 menu, toggling 28, 29 personal highlighting 22, 23 personalizing 17 scripting tips 182 script structure 175 search 63 status line 26 syntax-color schemes 141 tabs, modifying 33-37 toolbar icons, adding 32, 33 toolbar, toggling 28, 29 using, as Twitter client 212 visible markers 68-70 Vimballs creating 190 vimdiff about 112 navigation 113 using, to track changes 111 vimdiff session 112 Vim documentation 191, 193 Vim editor.

Thinking Machines: The Inside Story of Artificial Intelligence and Our Race to Build the Future

by

Luke Dormehl

Published 10 Aug 2016

Now video games presented an end goal in and of themselves. Not only were researchers’ skills in demand, but there was real money on offer too. One such beneficiary was Alexey Pajitnov, a 28-year-old AI researcher then working for the Soviet Academy of Sciences’ Computer Centre in Moscow. In June 1984, Pajitnov created a simple program to test out the lab’s new computer system. Brought to market by a shrewd entrepreneur under the name Tetris, Pajitnov’s falling blocks game proceeded to sell more than 170 million copies worldwide. As the 1980s wore on, video games became increasingly intricate and AI experts were snapped up to help.

…

(TV show) 135–9, 162, 189–90, 225, 254 Jobs, Steve 6–7, 32, 35, 108, 113, 181, 193, 231 Jochem, Todd 55–6 judges 153–4 Kasparov, Garry 137, 138–9, 177 Katz, Lawrence 159–60 Keck, George Fred 81–2 Keynes, John Maynard 139–40 Kjellberg, Felix (PewDiePie) 151 ‘knowledge engineers’ 29, 37 Knowledge Narrator 110–11 Kodak 238 Kolibree 67 Koza, John 188–9 Ktesibios of Alexandria 71–2 Kubrick, Stanley 2, 228 Kurzweil, Ray 213–14, 231–3 Landauer, Thomas 201–2 Lanier, Jaron 156, 157 Laorden, Carlos 100, 101 learning 37–9, 41–4, 52–3, 55 Deep 11–2, 56–63, 96–7, 164, 225 and email filters 88 machine 3, 71, 84–6, 88, 100, 112, 154, 158, 197, 215, 233, 237, 239 reinforcement 83, 232 and smart homes 84, 85 supervised 57 unsupervised 57–8 legal profession 145, 188, 192 LegalZoom 145 LG 132 Lickel, Charles 136–7 ‘life logging’ software 200 Linden, David J. 213–14 Loebner, Hugh 102–3, 105 Loebner Prize 102–5 Lohn, Jason 182, 183–5, 186 long-term potentiation 39–40 love 122–4 Lovelace, Ada 185, 189 Lovelace Test 185–6 Lucas, George 110–11 M2M communication 70–71 ‘M’ (AI assistant) 153 Machine Intelligence from Cortical Networks (MICrONS) project 214–15 machine learners 38 machine learning 3, 71, 84–6, 88, 100, 112, 154, 158, 197, 215, 233, 237, 239 Machine Translator 8–9, 11 ‘machine-aided recognition’ 19–20 Manhattan Project 14, 229 MARK 1 (computer) 43–4 Mattersight Corporation 127 McCarthy, John 18, 19, 20, 27, 42, 54, 253 McCulloch, Warren 40–2, 43, 60, 142–3 Mechanical Turk jobs 152–7 medicine 11, 30, 87–8, 92–5, 187–8, 192, 247, 254 memory 13, 14, 16, 38–9, 42, 49 ‘micro-worlds’ 25 Microsoft 62–3, 106–7, 111–12, 114, 118, 129 mind mapping the 210–14, 217, 218 ‘mind clones’ 203 uploads 221 mindfiles 201–2, 207, 212 Minsky, Marvin 18, 21, 24, 32, 42, 44–6, 49, 105, 205–7, 253–4 MIT 19–20, 27, 96–7, 129, 194–5 Mitsuku (chatterbot) 103–6, 108 Modernising Medicine 11 Momentum Machines, Inc. 141 Moore’s Law 209, 220, 231 Moravec’s paradox 26–7 mortgage applications 237–8 MTurk platform 153, 154, 155 music 168, 172–7, 179 Musk, Elon 149–50, 223–4 MYCIN (expert system) 30–1 nanobots 213–14 nanosensors 92 Nara Logics 118 NASA 6, 182, 184–5 natural selection 182–3 navigational aids 90–1, 126, 127, 128, 241 Nazis 15, 17, 227 Negobot 99–102 Nest Labs 67, 96, 254 Netflix 156, 198 NETtalk 51, 52–3, 60 neural networks 11–12, 38–9, 41, 42–3, 97, 118, 164–6, 168, 201, 208–9, 211, 214–15, 218, 220, 224–5, 233, 237–8, 249, 254, 256–7 neurons 40, 41–2, 46, 49–50, 207, 209–13, 216 neuroscience 40–2, 211, 212, 214, 215 New York World’s Fair 1964 5–11 Newell, Alan 19, 226 Newman, Judith 128–9 Nuance Communications 109 offices, smart 90 OpenWorm 210 ‘Optical Scanning and Information Retrieval’ 7–8, 10 paedophile detection 99–102 Page, Larry 6–7, 34, 220 ‘paperclip maximiser’ scenario 235 Papert, Seymour 27, 44, 45–6, 49 Paro (therapeutic robot) 130–1 patents 188–9 Perceiving and Recognising Automation (PARA) 43 perceptrons 43–6 personality capture 200–4 pharmaceuticals 187–8 Pitts, Walter 40–2, 43, 60 politics 119–2 Pomerlau, Dean 54, 55–6, 90 prediction 87, 198–9 Profound Hypothermia and Circulatory Arrest 219–20 punch-cards 8 Qualcomm 93 radio-frequency identification device (RFID) 65–6 Ramón y Cajal, Santiago 39–40 Rapidly Adapting Lateral Position Handler (RALPH) 55 ‘recommender system’ 198 refuse collection 142 ‘relational agents’ 130 remote working 238–9 reverse engineering 208, 216, 217 rights for AIs 248–51 risks of AI 223–40 accountability issues 240–4, 246–8 ethics 244–8 rights for AIs 248–51 technological unemployment 139–50, 163, 225, 255 robots 62, 74–7, 89–90, 130–1, 141, 149, 162, 217, 225, 227, 246–7, 255–6 Asimov’s three ethical rules of 244–8 robotic limbs 211–12 Roomba robot vacuum cleaner 75–7, 234, 236 Rosenblatt, Frank 42–6, 61, 220 rules 36–7, 79–80 Rumelhart, David 48, 50–1, 63 Russell, Bertrand 41 Rutter, Brad 138, 139 SAINT program 20 sampling (music) 155, 157 ‘Scheherazade’ (Ai storyteller) 169–70 scikit-learn 239 Scripps Health 92 Sculley, John 110–11 search engines 109–10 Searle, John 24–5 Second Life (video game) 194 Second World War 12–13, 14–15, 17, 72, 227 Sejnowski, Terry 48, 51–3 self-awareness 77, 246–7 self-driving 53–6, 90, 143, 149–50 Semantic Information Retrieval (SIR) 20–2 sensors 75–6, 80, 84–6, 93 SHAKEY robot 23–4, 27–8, 90 Shamir, Lior 172–7, 179, 180 Shannon, Claude 13, 16–18, 28, 253 shipping systems 198 Simon, Herbert 10, 19, 24, 226 Sinclair Oil Corporation 6 Singularity, the 228–3, 251, 256 Siri (AI assistant) 108–11, 113–14, 116, 118–19, 125–30, 132, 225–6, 231, 241, 256 SITU 69, 93 Skynet 231 smart devices 3, 66–7, 69–71, 73–7, 80–8, 92–7, 230–1, 254 and AI assistants 116 and feedback 73–4 problems with 94–7 ubiquitous 92–4 and unemployment 141–2 smartwatches 66, 93, 199 Sony 199–200 Sorto, Erik 211, 212 Space Invaders (video game) 37 spectrometers 93 speech recognition 59, 62, 109, 111, 114, 120 SRI International 28, 89–90, 112–13 StarCraft II (video game) 186–7 story generation 169–70 strategy 36 STUDENT program 20 synapses 209 Synthetic Interview 202–3 Tamagotchis 123–5 Tay (chatbot) 106–7 Taylorism 95–6 Teknowledge 32, 33 Terminator franchise 231, 235 Tetris (video game) 28 Theme Park (video game) 29 thermostats 73, 79, 80 ‘three wise men’ puzzle 246–7 Tojan Room, Cambridge University 69–70 ‘tortoises’ (robots) 74–7 toys 123–5 traffic congestion 90–1 transhumanists 205 transistors 16–17 Transits – Into an abyss (musical composition) 168 translation 8–9, 11, 62–3, 155, 225 Turing, Alan 3, 13–17, 28, 35, 102, 105–6, 227, 232 Turing Test 15, 101–7, 229, 232 tutors, remote 160–1 TV, smart 80, 82 Twitter 153–4 ‘ubiquitous computing’ 91–4 unemployment, technological 139–50, 163, 225, 255 universal micropayment system 156 Universal Turing Machine 15–16 Ursache, Marius 193–7, 203–4, 207 vacuum cleaners, robotic 75–7, 234, 236 video games 28–9, 35–7, 151–2, 186–7, 194, 197 Vinge, Vernor 229–30 virtual assistants 107–32, 225–6, 240–1 characteristics 126–8 falling in love with 122–4 political 119–22 proactive 116–18 therapeutic 128–31 voices 124–126, 127–8 Viv Labs 132 Vladeck, David 242–4 ‘vloggers’ 151–2 von Neumann, John 13–14, 17, 100, 229 Voxta (AI assistant) 119–20 waiter drones 141 ‘Walking Cities’ 89–90 Walter, William Grey 74–7 Warwick, Kevin 65–6 Watson (Blue J) 138–9, 162, 189–92 Waze 90–91, 126 weapons 14, 17, 72, 224–5, 234–5, 247, 255–6 ‘wetware’ 208 Wevorce 145 Wiener, Norbert 72–3, 227 Winston, Patrick 49–50 Wofram Alpha tool 108–9 Wozniak, Steve 35, 114 X.ai 116–17 Xbox 360, Kinect device 114 XCoffee 70 XCON (expert system) 31 Xiaoice 129, 130 YouTube 151 Yudkowsky, Eliezer 237–8 Zuckerberg, Mark 7, 107–8, 230–1, 254–5 Acknowledgments WRITING A BOOK is always a bit of a solitary process.

Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction

by

Derek Thompson

Published 7 Feb 2017

Many people will put themselves through quite a bit of disfluent anguish if they expect fluent resolution at the end. Video games, too, are often puzzles whose interactivity offers the wondrous click of recognition or jolt of accomplishment. The most popular video game of all time is Tetris. Alexey Pajitnov was a twenty-eight-year-old computer scientist working at a Soviet R&D center in Moscow when, after buying a set of funny-shaped dominoes, he got an idea for a video game. On June 6, 1984, he released an early version, which he named by combining “tetra,” after the four square blocks of each game piece, with “tennis,” his favorite sport.

…

“The consumer is influenced in his choice”: Ibid., 279. rate paintings by cubist artists: Claudia Muth and C. C. Carbon, “The Aesthetic Aha: On the Pleasure of Having Insights into Gestalt,” Acta Psychologica 144, no. 1 (September 2013): 25–30. most popular video game of all time: “About Tetris,” Tetris.com, http://tetris.com/about-tetris/. second bestselling game of all time: Tom Huddleston, Jr., “Minecraft Has Now Sold More Than 100 Million Copies,” Fortune, June 2, 2016, www.fortune.com/2016/06/02/minecraft-sold-100-million/. Minecraft, where users build shapes: Clive Thompson, “The Minecraft Generation,” New York Times Magazine, April 14, 2016, www.nytimes.com/2016/04/17/magazine/the-minecraft-generation.html.

…

Before long, the game spread across Moscow, hopped over to Hungary, was nearly stolen by a British developer, and went on to become the bestselling video game of all time, selling four hundred million copies. The game is a dance of anticipation and completion. Many novels and mystery stories may be analogous to falling puzzle pieces clicking into place, but Tetris is explicitly just that. The second bestselling game of all time is Minecraft, where users build shapes and virtual worlds from digital bricks. Minecraft is a kind of cultural inheritor to Lego, which was itself an “heir to the heritage of playing with blocks,” as tech journalist Clive Thompson wrote.

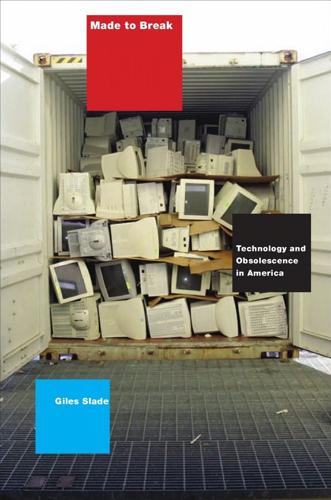

Made to Break: Technology and Obsolescence in America

by

Giles Slade

Published 14 Apr 2006

In a series of clever negotiations and subsequent lawsuits, Nintendo kept its American and European competitors from using the world’s most popular video game, Alexey Pajitnov’s Tetris. Nintendo then released a flas y, updated Game Boy version. David Sheff, author of a corporate history of Nintendo, wrote, “There is no way to measure accurately how much ‘Tetris’ contributed to the success of Game Boy . . . Once a customer bought one, Nintendo could sell more games, an average of three a year at $35 a pop. Not counting Game Boy, ‘Tetris’ brought Nintendo at least $80 million. Counting Game Boy, the figu e is in the billions of dollars.”62 Gradually, the largest pinball manufacturers—Bally, Williams, and Gottlieb—merged or were sold to WMS, a larger electronic concern.