We Are Bellingcat: Global Crime, Online Sleuths, and the Bold Future of News

by

Eliot Higgins

Published 2 Mar 2021

A tank commander, confounded by the order to do nothing to protect the innocent, thrust a gun in his mouth, threatening to kill himself rather than stand by. Other soldiers just abandoned their posts. By night, pitched battles still flared, but many reporters had left to file their stories. With the battle lines surging and receding, those who roamed outside faced injury. One journalist, Andy Carvin of National Public Radio, held his position that entire day, piecing together a running narrative of the Battle of the Camel. He never needed to take cover or press a vinegar-soaked rag to his mouth against the tear gas. He sat at a computer in Washington DC, chronicling the Arab Spring through social media.

…

My Twitter followers numbered around 1,500 people – far higher than months before, but still too few for my tweets to reverberate widely. Somehow, I needed to attract high-level attention, so tweeted a link to my blog article to any account that I thought might be interested, from Chivers of the New York Times to Amnesty International, to Human Rights Watch, to a reporter at the Guardian, to Andy Carvin of NPR, even members of the UK parliament whom I had come across for their role in confronting the phone-hacking scandal. For good measure, I sent a link to the top diplomat in Britain, Foreign Secretary William Hague. Chivers cited my findings on his own blog, rightly cautioning that my analysis was preliminary.

…

At best, I consider WikiLeaks a potential source among many that I would need to cross-reference. By the Tactical Tech retreat in the summer of 2013, the open-source investigative community amounted to a loose grouping that had formed organically, most of us amateurs plus a few pioneering professionals such as Andy Carvin, who had harnessed social media during the Arab Spring; Josh Lyons of Human Rights Watch, a master of satellite-imagery analysis; Christoph Koettl of Amnesty International, who pored over aerial photos of North Korean prison camps; and former computer programmer Malachy Browne of Storyful, a company that was among the first to monitor social-media feeds for facts that had yet to make it into the news.

WikiLeaks and the Age of Transparency

by

Micah L. Sifry

Published 19 Feb 2011

Ethan Zuckerman has a comprehensive write-up recounting the lessons of the post-Katrina efforts of volunteer coders on his blog, My Heart’s in Accra: “Recovery 2.0 – thoughts on what worked and failed on PeopleFinder so far,” September 6, 2005, www.ethanzuckerman.com/ blog/2005/09/06/recovery-20-thoughts-on-what-worked-and-failed-onpeoplefinder-so-far. Al Tompkins, “NPR’s Andy Carvin on the Role of Social Media in Gustav Coverage,” Poynter, September 1, 2008, www.poynter.org/latest-news/ als-morning-meeting/91234/nprs-andy-carvin-on-the-role-of-socialmedia-in-gustav-coverage. Nina Keim and Jessica Clark, “Public Media 2.0 Field Report: Building Social Media Infrastructure to Engage Publics,” October 2009, Center for Social Media, www.centerforsocialmedia.org/future-public-media/ documents/field-reports/public-media-20-field-report-building-socialmedia-infra.

…

In its first three months of existence, Ushahidi logged thousands of reports, which they diligently worked to verify with local nongovernmental groups, and ultimately counted about 45,000 unique users in Kenya. As Hersman was quick to admit, what he and his fellow programmers built wasn’t all that original. After the 2004 tsunami that ravaged much of South Asia, online activists like American Andy Carvin created sites like Tsunami-Info.org, using RSS feeds to aggregate information meant to help relief efforts. In 2005, an ad hoc collaboration of a number of data mavens, including Carvin and Ethan Zuckerman, David Geilhufe, Zack Rosen, and Jon Lebkowsky, rallied coders and other volunteers to build a “PeopleFinder” database to aggregate reports of missing and displaced persons, as well as the “Katrina Aftermath” blog,9 to capture and highlight people’s stories of the disaster.10 In August of 2008, as Hurricane Gustav threatened the Gulf Coast, Carvin led five hundred volunteers in building a similar crisis relief site—only this time the hard work was done in advance.11 92 MICAH L.

The New Digital Age: Transforming Nations, Businesses, and Our Lives

by

Eric Schmidt

and

Jared Cohen

Published 22 Apr 2013

But while Scott-Railton was able to garner some popular attention for his tweets, there are limits to what someone with his profile could achieve in terms of influencing policy-makers. Perhaps a more important example is Andy Carvin, who curated one of the most important streams of information in both the Egyptian and Libyan revolutions, with tens of thousands of followers and countless journalists globally who knew that Carvin himself (a senior NPR strategist) had the journalistic standards of a professional reporter and so would tweet or re-tweet only things he could verify. He became a one-man filter of enormous influence, cultivating and vetting sources. Ultimately, though, however talented the Andy Carvins or John Scott-Railtons of the world are, the hard work of revolutionary movements is done on the ground, by the people inside a country willing to take to the streets.

…

Twitter account started by a twenty-something graduate student: Stephan Faris, “Meet the Man Tweeting Egypt’s Voices to the World,” Time, February 1, 2011, http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2045489,00.html. posted updates about the protests: Ibid. @Jan25voices Twitter handle was a major conduit of information: Ibid. Andy Carvin, who curated one of the most important streams of information: Andy Carvin, interview by Robert Siegel, “The Revolution Will Be Tweeted,” NPR, February 21, 2011, http://www.npr.org/2011/02/21/133943604/The-Revolution-Will-Be-Tweeted. they had formed the National Transitional Council (NTC) in Benghazi: “Anti-Gaddafi Figures Say Form National Council,” Reuters, February 27, 2011, Africa edition, http://af.reuters.com/article/idAFWEB194120110227.

The End of Big: How the Internet Makes David the New Goliath

by

Nicco Mele

Published 14 Apr 2013

Storify Another online community, Storify, supports traditional journalism’s news delivery and watchdog roles by offering a place to summarize and collect social media from around the Web to tell a coherent story. If you want to follow a news story on social media, it can be hard, given the dispersed nature of social media platforms. Storify essentially allows anyone, including professional journalists, to pull from a wide range of social media to tell a story. Andy Carvin, who runs online communities for National Public Radio, started using Storify to collect social media while reporting on the shooting of Arizona Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords. He “grabbed” a handful of social media mentions relevant to the story, starting with the last tweet from Congresswoman Giffords before she was shot and including tweets from other eyewitnesses as well as breaking news reports and relevant YouTube videos.42 Carvin went on to organize a number of Storify narratives around the Arab Spring, telling the stories of political uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, and Syria by curating social media from people on the ground who experienced it live.

Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations

by

Clay Shirky

Published 28 Feb 2008

The results were one part ridiculous and three parts depressing; police were waiting in the square and hauled away several of the ice cream eaters, all while being documented in the now-standard pattern as other participants took digital pictures and uploaded them to Flickr, LiveJournal, and other online outlets. These pictures were in turn recirculated by bloggers like Andy Carvin and Ethan Zuckerman, political bloggers who cover the use of technology as a tool for social change. Images of a repressive Belarus thus spread far beyond the borders of Minsk. Nothing says “police state” like detaining kids for eating ice cream. The ice cream mob was not an isolated incident.

Smarter Than You Think: How Technology Is Changing Our Minds for the Better

by

Clive Thompson

Published 11 Sep 2013

Friends and followers worldwide, accustomed to glancing at Eltahawy’s utterances online, instantly learned of the arrest and began talking about it. One was Zeynep Tufekci, an assistant professor who studies technology and society at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; she contacted NPR’s Andy Carvin, a friend who tweets about the Middle East, and the two set up a hashtag—#FreeMona—to coordinate how to help Eltahawy. A mere twenty minutes later, so many supporters were discussing how to help that #FreeMona became a worldwide trending topic. Hundreds more sprang into action: Sarah Badr, a designer, called the U.S. embassy and tweeted her conversation alerting them; Anne-Marie Slaughter, a former director of policy planning at the U.S.

Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest

by

Zeynep Tufekci

Published 14 May 2017

That they were unaware of this limit before they became activists was a testament to how normal and relatively infrequent their previous Twitter use had been. I suggested that they set up an alternate account and authenticate it as theirs before their original account was frozen. Sure enough, they were soon “Twitter jailed” for tweeting too often. At that point, I checked in with a friend, Andy Carvin, NPR’s social media chief at the time. He was also glued to his devices as he undertook an extensive reporting effort about the uprisings that were sweeping through there region from social media, and had been following the travails of @TahrirSupplies. Through contacts at Twitter, Carvin was able to facilitate “unjailing” the account so the group could continue tweeting.

CTOs at Work

by

Scott Donaldson

,

Stanley Siegel

and

Gary Donaldson

Published 13 Jan 2012

If you go to the NPR Facebook page and look at the entry point into NPR.org, a large portion of that is now through social networks, particularly Facebook. I don't know about Twitter on my side of the house. However, Twitter is big on the content side of the house. Our head social media strategist is Andy Carvin who's probably one of the most famous tweeters out there right now doing ground-breaking work in using Twitter as a reporting tool. We're producing a lot of news on the digital side of the house. The digital side of the house is a very interesting discussion. I'll just touch on it. Our distribution model is that we produce programming for the local radio stations, for example WAMU is a great example.

Breaking News: The Remaking of Journalism and Why It Matters Now

by

Alan Rusbridger

Published 14 Oct 2018

It was an idea that was to catch on. These techniques may seem less radical now, but they were virtually unheard of at the time. Some years later the Washington Post’s excellent reporter David Fahrenthold was to win the Pulitzer for his open-source reporting of Donald Trump in 2016. An NPR strategist, Andy Carvin, also broke new ground in 2011 with something clumsily labelled ‘collaborative networked journalism’, to become, for a while at least, the must-read source on the Arab uprisings. A veteran of social media, Carvin had begun retweeting testimonies, pictures and video from the protests in Tunisia – then Egypt and Libya.

Dawn of the Code War: America's Battle Against Russia, China, and the Rising Global Cyber Threat

by

John P. Carlin

and

Garrett M. Graff

Published 15 Oct 2018

The stunning report caused the stock market to tumble; in just one minute, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell by 1 percent—erasing $136 billion in market value.19 It took only a few minutes for the AP to correct the report, explaining it had been hacked, and the stock market recovered quickly. The hack prompted NPR reporter Andy Carvin, who had made a specialty of covering the Arab Spring online through social media, to ask, “When do vandals graduate to cyber terrorists?”20 Even though the stock market recovered, the fake tweet remains the largest financial loss attributed to cyberattacks thus far. By the summer of 2013, SEA was getting even more creative—targeting the IT infrastructure that supported news websites and at one point targeting an Australian company that ran domain names.

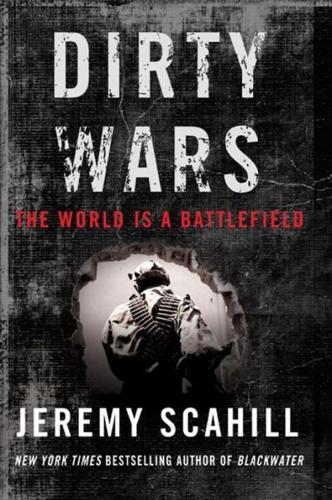

Dirty Wars: The World Is a Battlefield

by

Jeremy Scahill

Published 22 Apr 2013

Among them, Brandon Webb and Jack Murphy at the Special Operations Forces Situation Report, Rob Dubois, Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, Jeff Emanuel, Rob Caruso, Dan Trombly, Joshua Foust, Clint Watts, Matthew Hoh, Andrew Exum, Nada Bakos, Will McCants, Mosharraff Zaidi, Huma and Saba Imtiaz, Omar Waraich, Andy Carvin, Caitlin Fitzgerald, Blake Hounshell, Sebastian Junger, Timothy Carney, Peter Bergen and Chris Albon. Thank you also to David Massoni, whose Thistle Hill Tavern provided me many meals while writing this book. As of this writing, Yemeni journalist Abdulelah Haider Shaye remains locked up in a prison in Sana’a, in part due to the intervention of the White House.