The Way We Eat: Why Our Food Choices Matter

by Peter Singer and Jim Mason · 1 May 2006 · 400pp · 129,320 words

WAY W E EAT WHY OUR FOOD CHOICES MATTER PETER SINGER 11M MASON CONTENTS PREFACE ...........................................................................................V INTRODUCTION: FOOD AND ETHICS .................................................3 PART I: EATING THE STANDARD AMERICAN DIET 1. Jake and Lee ...............................................................................15 2. The Hidden

…

Animal Factories stirred up subsided without any significant changes taking place. Although the new animal movement, which some say was triggered by my earlier book, Animal Liberation, was starting to make an impact, in America most activists were still very much focused on animals used in research, for fur, and in circuses

…

that would respond to the widespread interest in taking an ethical approach to all our food choices. This book is the outcome of that discussion. -Peter Singer, Princeton, New Jersey I was delighted when Peter returned to the United States so that we could continue our work together exploring the issues surrounding

…

for Friends of Animals. That put me in touch with Peter, who was living in New York at the time. As soon as his book, Animal Liberation, came out in 1975, 1 sug gested that we write a book on factory farming. Peter agreed and proposed that we include photographs as they

…

working on this book. The email correspondence went like this: January 24, 2005 Hello Steve Kopperud, Perhaps you remember my name from my book with Peter Singer, Animal Factories. We're at work on a new book now that will cover a wide range of ethical concerns that consumers have today about

…

, as he later told an interviewer, "I read a dozen books about how animals are raised in this country, going all the way back to Peter Singer's Animal Liberation in 1975. The more I read, the more I was interested in it. I said, `Damn, these people are right. This is terrible."' At

…

have been produced on the Scruton farm. "That's Singer," declares Roger, pointing at a plate of leftover sausages. Singer the pig, mischievously named after Peter Singer, the philosopher and animal-rights theorist, has been "ensausaged" personally by his former owner.' Nevertheless, Scruton flatly rejects factory farming. "A true morality of animal

…

Roger Scruton. Pollan's The New York Times Sunday Magazine essay "An Animal's Place," begins with the line: "The first time I opened Peter Singer's Animal Liberation, I was dining alone at the Palm, trying to enjoy a ribeye steak cooked medium-rare." From there he goes on to describe factory farming

…

generations worse off. 3. Humanity: Inflicting significant suffering on animals for minor reasons is wrong. Most people, even those opposed to more radical ideas of "animal liberation" or "animal rights," agree that we should try to avoid causing pain or other forms of distress on animals. Kindness and compassion toward all, humans

…

have discussed some of Pollan's writing in the preceding pages. This is his fullest statement on our food choices. ANIMAL AGRICULTURE Jim Mason and Peter Singer, Animal Factories: What Agribusiness Is Doing to the Family Farm, the Environment and Your Health (New York: Harmony Books, rev. ed. 1990). Although now out

…

and Berkeley, 2002. See also www.foodpolitics.com. 5 See www.supersizeme.com. 6 For a full account of how veal calves are kept, see Peter Singer, Animal Liberation, Ecco, New York, 2001 (first published 1975). On the decline in veal consumption, see USDA Economic Research Service, Food availability spreadsheets: Beef, veal, pork, lamb

…

. 15 See Scientific Veterinary Committee, Animal Welfare Section, The Welfare of Intensively Kept Pigs, 1997, and Clare Druce and Philip Lymbery, "Outlawed in Europe," in Peter Singer, ed., In Defense of Animals: The Second Wave, Blackwell, Oxford, 2005. 16 In the European Union, 242 million pigs were slaughtered in 2005, compared to

…

24 Richard Posner, Catastrophe: Risk and Response, Oxford University Press, New York, 2004. 25 For further discussion of climate change as an ethical issue, see Peter Singer, One World, Yale University Press, 2002, chapter 2. 26 John Hendrickson, "Energy use in the U.S. Food System: A summary of existing research and

…

.pdf. S M. Ataman Aksoy and John Beghin, eds., Global Agricultural Trade and Developing Countries, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2005. 6 Charles Walaga, email to Peter Singer, April 2005. See also Paul Collier and Ritva Reinikka (eds), Uganda's Recovery: The Role of Farms, Firms and Government, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2001

…

. 7 Charles Walaga, email to Peter Singer, April 2005. 8 Oxfam International, Rigged Rules and Double Standards: Trade, Globalisation and the Fight Against Poverty, Oxfam, 2002, pp. 10, 48, 53-55. www

…

-E.pdf. We owe this reference to Sophia Murphy, whose report Agriculture Inc. is currently in preparation for Oxfam America. 9 Brian Halweil, email to Peter Singer, February 2005. 10 For Kenya and Zimbabwe, see C. Dolan, J. Humphrey, and C. Harris-Pascal, "Value Chains and Upgrading: The Impact of U.K

…

. The figure for banana workers is from FAO, The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets: 2004. FAO, Rome, 2004, p. 31. 11 Charles Walaga, email to Peter Singer, April 2005 and "The Development of the Organic Agriculture Sector in Africa: Potentials and Challenges," Ecology and Farming, no. 29, January-April, 2002. 12 Fairtrade

…

Defending Democratic Governance?" Law and Policy, vol. 25 (2003) pp. 269-297; for details of SA8000, see www.sa8000.org. 16 Michael Mitchell, email to Peter Singer, March 8, 2005. 17 International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, "Summary of Findings from the Child Labor Surveys in the Cocoa Sector of West Africa: Cameroon

…

, Los Angeles, May 3, 2004, reprinted as John Mackey, Karen Dawn, and Lauren Ornelas, "The CEO as Animal Activist: John Mackey and Whole Foods," in Peter Singer, ed., In Defense of Animals, Blackwell, Oxford, 2005. www. animalcompassionfoundation.org; www.wholefoodsmarket.com; Jon Gertner, "The Virtue in $6 Heirloom Tomatoes," The New York

…

Being a Burt hen to Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Public, first published 1729, reprinted in Tom Regan and Peter Singer, eds., Animal Rights and Human Obligations, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1976, pp. 234-237. 11 For a powerful argument for this position, see Paola

…

Salt, "The Logic of the Larder," first published in Henry Salt, The Humanities of Diet, The Vegetarian Society, Manchester, 1914, reprinted in Tom Regan and Peter Singer, Animal Rights and Human Obligations, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1976, p 186. 1S See Derek Parfit, Reasons and Persons, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1984, Part

The omnivore's dilemma: a natural history of four meals

by Michael Pollan · 15 Dec 2006 · 467pp · 503 words

deeply shadowed again by the omnivore 's dilemma. • 303 SEVENTEEN THE ETHICS OF EATING ANIMALS 1. THE STEAKHOUSE DIALOGUES The first time I opened Peter Singer's Animal Liberation I was dining alone at the Palm, trying to enjoy a rib-eye steak cooked medium rare. If that sounds like a recipe for cognitive

…

lives has opened a space in which there's no reality check on the sentiment or the brutality; it is a space in which the Peter Singers and the Frank Purdues of the world fare equally well. A few years ago the English writer John Berger wrote an essay called "Why Look

…

completely off the table. Which might explain how it was I found myself attempting to read Peter Singer in a steakhouse. THIS IS NOT something I'd recommend if you're determined to con- tinue eating meat. Animal Liberation, comprised of equal parts philosophical argument and journalistic description, is one of those rare books

…

you either defend the way you live or change it. Because Singer is so skilled in argument, for many readers it is easier to change. .Animal Liberation has converted countless thousands to vegetarianism, and it didn't take me long to see why: within a few pages he had succeeded in throwing

…

choice is not between the baby and the chimp but between the pig and the tofu. Even if we reject the hard utilitarianism of a Peter Singer, there remains the question of whether we owe animals that can feel pain any moral consideration, and this seems impossible to deny. And if we

…

do either? I guess you have to try to determine if the animals you're eating have really endured a lifetime of suffering. According to Peter Singer I can't hope to answer that question ob- THE ETHICS O F EATING ANIMALS jectively as long as I'm still eating meat. "We

…

mollusks, on the theory that they're not sufficiently sentient to suffer. No, this isn't "facist" of me: Many scientists and animal rights philosophers (Peter Singer included) draw the line of sentience at a point just north of scallop. No one knows for absolute certain if this is right, but I

…

, is the cause of much anguished hand-wringing in the animal rights literature. "It must be admitted," Peter Singer writes, "that the existence of carnivorous animals does pose one problem for the ethics of Animal Liberation, and that is whether we should do anything about it." (Talk about the need for peacekeeping forces!) Some

…

of a reasonable creature as one who can come up with reasons for whatever he wants to do. So I decided I would track down Peter Singer and ask him what he thought. I hatched a scheme to drive him down from Princeton to meet Joel Salatin and his animals, but Singer

…

and slaughtered animals. Eating a wild animal that had been cleanly shot presumably would fall under the same dispensation. Singer himself suggests as much in Animal Liberation, when he asks, "Why . . . is the hunter who shoots a deer for venison subject to more criticism than the person who buys a ham at

…

place where we feel our only choice is either to look away or give up meat. National Beef is happy to serve the first customer, Peter Singer the second. My own wager is that there might still be another way open to us, and that finding it will begin with looking once

…

3 - 2 9 ; the quote is on page 2 2 7 . Regan, Tom. The Case for Animal Rights (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983). , and Peter Singer, eds. Animal Rights and Human Obligations (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1989). Scully, Matthew. Dominion: The Power of Man, the Suffering of Animals, and the

…

to Mercy (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2002). An eloquent defense of animals, and an indictment of factory farming, from the right. Singer, Peter. Animal Liberation (NewYork: Ecco, 2002). 43 4 * SOURCES . Practical Ethics (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1999). , ed. In Defense of Animals (New York: Basil Blackwell, 1

…

amanita, 376, 377 AMC (argument from marginal cases), 308,311-12 American paradox, 3-5 amino acids, 20, 42 ammonium nitrate, 4 1 , 4 4 Animal Liberation (Singer), 304, 307-9, 328 animal rights: and animal happiness, 319—25, 328 and animal suffering, 308, 310, 312-13,315-19,328 arguments with

The Most Good You Can Do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically

by Peter Singer · 1 Jan 2015 · 197pp · 59,656 words

. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Singer, Peter, 1946– The most good you can do: how effective altruism is changing ideas about living ethically / Peter Singer. pages cm. — (Castle lectures in ethics, politics, and economics) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-18027-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Altruism

…

of reason and emotion in motivating altruism can be found in chapter 2 of Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek and Peter Singer, The Point of View of the Universe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014). Peter Singer University Center for Human Values, Princeton University & School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne PART ONE EFFECTIVE

…

other, more traditional approaches are worth what they cost.8 I first met Henry Spira in 1974, when he attended an adult education course on animal liberation that I taught at New York University. He had spent most of his life working for the weak and oppressed, taking part in civil rights

…

him that nonhuman animals might be included among the weak and oppressed, but the cat prepared him to be receptive to my first essay on animal liberation, which appeared around that time.9 He heard about the course, came to all the sessions, and at the end of it stood up and

…

own situation, in 1972–73, when I wrote about two separate causes: global poverty, in “Famine, Affluence and Morality,” and the treatment of animals, in “Animal Liberation.”1 These were not the only issues around at the time—the Vietnam War was still being fought, and the threat of nuclear war between

…

, does the suffering of the animal matter as much as the suffering of the human? The answer to the ethical question should be yes. In Animal Liberation I argue that to give less consideration to the interests of nonhuman animals, merely because they are not members of our species, is speciesism and

…

giving to the poor, see Luke 10:33, 14:13, and Matthew 25:31–46. 7. See www.aaronmoore.com.au. The statement is from Peter Singer, Practical Ethics, 3d ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 200. A similar statement appears in my “Famine, Affluence and Morality,” Philosophy and Public Affairs 1

…

R. M. Hare, Essays in Ethical Theory (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), 219n. 13. Anonymous comment made in a discussion forum about earning to give on Peter Singer’s Practical Ethics online course, April 2014. 14. It is possible to value equality for its own sake and still be very supportive of effective

…

/buddhist-organization-sandy-victims–600-debit-cards-article–1.1204224. 8. Paul Niehaus provided information for this section. 9. Peter Singer, “Animal Liberation,” New York Review of Books, April 5, 1973. 10. For details, see Peter Singer, Ethics into Action: Henry Spira and the Animal Rights Movement (Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1998). Chapter 6. Giving

…

Methods of Ethics, 382. The following account of Sidgwick’s view of how ethical judgments can be motivating draws on Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek and Peter Singer, The Point of View of the Universe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014). 17. The Methods of Ethics, 40, 500. Chapter 8. One Among Many 1

…

Chicago Press, 2012). Asma acknowledges his indebtedness to Williams on page 183, note 22. 2. For a fuller account, see Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek and Peter Singer, “The Objectivity of Ethics and the Unity of Practical Reason,” Ethics 123 (2012): 9–31; for critical discussion, see http://peasoup.typepad.com/peasoup/2012

…

/12/ethics-discussions-at-pea-soup-katarzyna-de-lazari-radek-and-peter-singer-the-objectivity-of-ethics–1.html, and Guy Kahane, “Evolution and Impartiality,” Ethics 124 (2014): 327–41. 3. Rachel Maley, “Choosing to Give,” The Life

…

Self-Esteem (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 1996), 7. 17. T. M. Scanlon, What We Owe to Each Other (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998). 18. Peter Singer, Ethics into Action: Henry Spira and the Animal Rights Movement (Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1998), 197. 19. For discussion, see Shih Chao-hwieh, Buddhist

…

the same issue, pages 23–24. For discussion of the broader question of the methods used to reach such figures, see John McKie, Jeff Richardson, Peter Singer, and Helga Kuhse, The Allocation of Health Care Resources: An Ethical Evaluation of the “QALY” Approach (Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate Publishing, 1998). 3. For research

…

-to-death/. 6. Animal Charity Evaluators, FAQ, Position Statement. See http://www.animalcharityevaluators.org/about/faq/ and http://www.animalcharityevaluators.org/about/position-statement/. 7. Peter Singer, Animal Liberation (1975; reprint, New York: Harper, 2009), chap. 1; for support for my claim that at a philosophical level the argument against speciesism is “won,” see

…

. 4, 5. Note, however, that since writing that I have become more sympathetic to hedonism rather than preference utilitarianism. See Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek and Peter Singer, The Point of View of the Universe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), chaps. 8, 9. For other views on the killing of animals, see Jeff

…

(2013), no. 9, http://www.existential-risk.org/faq.html. 9. Henry Sidgwick, The Methods of Ethics, 7th ed. (London: Macmillan, 1907), 415. 10. See Peter Singer, Practical Ethics, 3d ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 88–90, 107–19; for a more recent account of my views on this topic that

…

is fuller than I can present here, see Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek and Peter Singer, The Point of View of the Universe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 361–77. 11. The most influential critique of views that give priority to

…

, archbishop of Milan, (i) Angola, corruption in, (i) Animal Activists’ Handbook, The (Ball and Friedrich), (i) Animal Charity Evaluators (ACE), (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Animal Liberation (Singer), (i) “Animal Liberation” (Singer), (i), (ii) animal rights, (i), (ii) animal suffering: emotion and reason in response to, (i); pets vs. farm animals, (i), (ii), (iii); product

…

), (ii) Zaki, Radi, (i) Parts of this book were given as the Castle Lectures in Yale’s Program in Ethics, Politics, and Economics, delivered by Peter Singer at Yale University in 2013. The Castle Lectures were endowed by Mr. John K. Castle. They honor his ancestor the Reverend James Pierpont, one of

The Three-Body Problem (Remembrance of Earth's Past)

by Cixin Liu · 11 Nov 2014 · 420pp · 119,928 words

rough-hewn bed and kitchen implements. A pile of books, most of which dealt with biology, sat on his bed. Ye noticed a copy of Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation. The only sign of modernity was a small radio set, hooked up to an external D battery. There was also an old telescope. Evans

The God Delusion

by Richard Dawkins · 12 Sep 2006 · 478pp · 142,608 words

intuitions. Surely, if we get our morality from religion, they should differ. But it seems that they don’t. Hauser, working with the moral philosopher Peter Singer,87 focused on three hypothetical dilemmas and compared the verdicts of atheists with those of religious people. In each case, the subjects were asked to

…

and women and, in Nazi Germany, Jews and gypsies have been treated badly is that they were not perceived as fully human. The philosopher Peter Singer, in Animal Liberation, is the most eloquent advocate of the view that we should move to a post-speciesist condition in which humane treatment is meted out to

…

Society. Silver, L. M. (2006). Challenging Nature: The Clash of Science and Spirituality at the New Frontiers of Life. New York: HarperCollins. Singer, P. (1990). Animal Liberation. London: Jonathan Cape. Singer, P. (1994). Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Smith, K. (1995). Ken’s Guide to the Bible. New York: Blast Books. Smolin

The Unpersuadables: Adventures With the Enemies of Science

by Will Storr · 1 Jan 2013 · 476pp · 134,735 words

nations: ‘Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin helped to end slavery in the United States, and descriptions of animal suffering in Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation and elsewhere have been powerful catalysts for the animal-rights movement.’ Stories change us first, and then they change the world. * The mind is

Life You Can Save: Acting Now to End World Poverty

by Peter Singer · 3 Mar 2009 · 190pp · 61,970 words

ALSO BY PETER SINGER Democracy and Disobedience Animal Liberation Practical Ethics Marx Animal Factories (with James Mason) The Expanding Circle Hegel The Reproduction Revolution (with Dean Wells) Should the Baby Live? (with Helga Kuhse)

…

the end, and look honestly and carefully at our situation, assessing both the facts and the ethical arguments, you will agree that we must act. PETER SINGER THE ARGUMENT 1. Saving a Child On your way to work, you pass a small pond. On hot days, children sometimes play in the pond

…

world so that we come to see helping those in great need as an indispensable part of what it is to live an ethical life. PETER SINGER June 2010 Acknowledgments An invitation from Professor Julian Savulescu to give the 2007 Uehiro Lectures in Practical Ethics at Oxford University got me started on

…

. Is It Wrong Not to Help? 1. Peter Unger, Living High and Letting Die (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996). 2. For further discussion see Peter Singer, The Expanding Circle, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981), pp. 136, 183. For futher examples, see www.unification.net/ws/theme015.htm. 3. Luke 18:22-25

…

OECD or the Giving USA data. See Center for Global Prosperity, Index of Global Philanthropy, Hudson Institute, 2008, available at http://gpr.hudson.org/. 4. Peter Singer, “The Singer Solution to World Poverty,” The New York Times Sunday Magazine, September 5, 1999. 5. Glennview High School is Seider’s fictional name for

…

. 22. Alan Ryan, as quoted by Michael Specter in “The Dangerous Philosopher,” The New Yorker, September 6, 1999. 23. http://www.muzakandpotatoes.com/2008/02/peter-singer-on-affluence.html. 4. Why Don’t We Give More? 1. C. Daniel Batson and Elizabeth Thompson, “Why Don’t Moral People Act Morally? Motivational

…

, The Unresponsive Bystander (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1970), p. 58.1 am grateful to Judith Lichtenberg, “Famine, Affluence and Psychology,” in Jeffrey Schaller, ed., Peter Singer Under Fire (Chicago: Open Court, forthcoming 2009) both for suggesting the relevance of this research and for this and other references. 20. Bib Latane and

…

. Elizabeth Corcoran, “Ruthless Philanthropy,” www.Forbes.com, June 23, 2008. 26. For a fuller discussion of the relevance of our evolved psychology to ethics, see Peter Singer, The Expanding Circle: Ethics and Sociobiology (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1981). 5. Creating a Culture of Giving 1. See Bib Latane and John Darley

…

. ed. (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1999), p. 112. 3. See Richard Arneson, “What Do We Owe to Distant Needy Strangers?” in Jeffrey Schaler (ed.), Peter Singer Under Fire (Chicago: Open Court, forthcoming 2009). 4. For Gates’s speech, see www.gatesfoundation.org/MediaCenter/Speeches/Co-ChairSpeeches/BillgSpeeches/BGSpeechWHA-050516.htm?version

…

. 5831 (June 15, 2007), pp. 1622-25. 24. For more information about Henry Spira, see Peter Singer, Ethics into Action: Henry Spira and the Animal Rights Movement (Lanham, MD.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1998). ABOUT THE AUTHOR PETER SINGER was born in Melbourne, Australia, in 1946, and educated at the University of Melbourne and the

…

, and since 2005, Laureate Professor at the University of Melbourne, attached to the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics. Peter Singer first became well known internationally after the publication of Animal Liberation. He is the author of many other books, as well as of the major entry on ethics in the current edition

…

world.” Singer is married and has three daughters and three grandchildren. His recreations, apart from reading and writing, include hiking and surfing. Copyright © 2009 by Peter Singer All rights reserved. RANDOM HOUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Singer, Peter The life

…

you can save : acting now to end world poverty / Peter Singer p. cm. Includes index. eISBN: 978-1-58836-779-2 1. Charity. 2. Humanitarianism. 3. Economic assistance. 4. Poverty. I. Title. HV48.S56 2009 362

The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature

by Steven Pinker · 1 Jan 2002 · 901pp · 234,905 words

of war, infanticide as a form of birth control, and the legal ownership of women—have vanished from large parts of the world. The philosopher Peter Singer has shown how continuous moral progress can emerge from a fixed moral sense.18 Suppose we are endowed with a conscience that treats other persons

…

it does suggest that something may have been right about the theory of human nature that guided its architects. The left needs a new paradigm. —Peter Singer, A Darwinian Left (1999)43 Conservatives need Charles Darwin. —Larry Arnhart, “Conservatives, Design, and Darwin” (2000)44 What’s going on? That voices of the

…

incomprehension of such deeds may be compared with animal rights activists’ incomprehension of ours. It is no coincidence that Peter Singer, the author of The Expanding Circle, is also the author of Animal Liberation. The observation that people may be morally indifferent to other people who are outside a mental circle immediately suggests an

…

American Medical Association American Psychological Association American Revolution Amnesty International amygdala analogy see also metaphor Anderson, Elijah Anderson, John Anderson, Steven androgens see also testosterone Animal Liberation (Singer) animal rights Annie Hall anthropology Antigones (Steiner) AntZ Apted, Michael archaeology architecture, modernist Ardrey, Robert aristocracy Aristotle Arlo and Janis Arnhart, Larry Art (Bell

The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

by Steven Pinker · 24 Sep 2012 · 1,351pp · 385,579 words

to hold back when it comes to larger circles of neighbors, strangers, foreigners, and other sentient beings. In his book The Expanding Circle, the philosopher Peter Singer has argued that over the course of history, people have enlarged the range of beings whose interests they value as they value their own.136

…

, come to the rescue of other oppressed classes, such as slaves or homosexuals or women.” 272 The real turning point was the philosopher Peter Singer’s 1975 book Animal Liberation, the so-called bible of the animal rights movement. 273 The sobriquet is doubly ironic because Singer is a secularist and a utilitarian, and

…

of farm animals was a major pollutant, particularly methane, the greenhouse gas that comes out of both ends of a cow. Whether you call it animal liberation, animal rights, animal welfare, or the animal movement, the decades since 1975 in Western culture have seen a growing intolerance of violence toward animals. Changes

…

that the oxytocin network is a vital trigger in the sympathetic response to other people’s beliefs and desires. In chapter 4 I alluded to Peter Singer’s hypothesis of an expanding circle of empathy, really a circle of sympathy. Its innermost kernel is the nurturance we feel toward our own children

…

benefits of nonviolence and other forms of reciprocal consideration, and apply them more and more broadly. This is the theory of the expanding circle as Peter Singer originally formulated it.224 Though I have co-opted his metaphor as a name for the historical process in which increased opportunities for perspective-taking

…

in Spencer, 2000, pp. 278–79. 271. Takeoff in the 1970s: Singer, 1975/2009; Spencer, 2000. 272. Brophy: Quoted in Spencer, 2000, p. 303. 273. Animal Liberation: Singer, 1975/2009. 274. Expanding Circle: Singer, 1981/2011. 275. V-Frog: K. W. Burton, “Virtual dissection,” Science, Feb. 22, 2008. 276. Cockfighting: Herzog, 2010

…

, 27, 511–26. Singer, D. J., & Small, M. 1972. The wages of war 1816–1965: A statistical handbook. New York: Wiley. Singer, P. 1975/2009. Animal liberation: The definitive classic of the animal movement, updated ed. New York: HarperCollins. Singer, P. 1981/2011. The expanding circle: Ethics and sociobiology. Princeton, N.J

…

Shultz, George Shweder, Richard Sidanius, Jim siege, use of term Silence of the Lambs, The (film) Simon, Paul Simon, Robert Simonton, Dean Singapore Singer, Peter: Animal Liberation The Expanding Circle Singer, Tania sins, seven deadly SIPRI (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute) six degrees of separation Skenazy, Lenore skepticism slavery abolition of in

How Much Is Enough?: Money and the Good Life

by Robert Skidelsky and Edward Skidelsky · 18 Jun 2012 · 279pp · 87,910 words

, Long-Range Ecological Movement: A Summary,” in Andrew Dobson (ed.), The Green Reader (London: Deutsch, 1991), p. 243. 31. The term speciesism was popularized by Peter Singer, Animal Liberation (Avon, 1977). 32. Aldo Leopold, “A Sand County Almanac,” in Dobson (ed.), The Green Reader, pp. 240–41. 33. For a persuasive defense of this

…

defense of the importance of gardens and gardening to the good life. 37. Lovelock, The Revenge of Gaia, pp. 169–70. 38. J. Baird Callicott, “Animal Liberation: A Triangular Affair,” in Robert Elliot (ed.), Environmental Ethics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 39. Quoted in Passmore, Man’s Responsibility for Nature, p. 105. CHAPTER

The Vegetarian Myth: Food, Justice, and Sustainability

by Lierre Keith · 30 Apr 2009 · 321pp · 85,893 words

Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution

by Francis Fukuyama · 1 Jan 2002 · 350pp · 96,803 words

Diet for a New America

by John Robbins · 566pp · 151,193 words

Meat: A Benign Extravagance

by Simon Fairlie · 14 Jun 2010 · 614pp · 176,458 words

Anarchy State and Utopia

by Robert Nozick · 15 Mar 1974 · 524pp · 146,798 words

Billion Dollar Burger: Inside Big Tech's Race for the Future of Food

by Chase Purdy · 15 Jun 2020 · 232pp · 63,803 words

Moral Ambition: Stop Wasting Your Talent and Start Making a Difference

by Bregman, Rutger · 9 Mar 2025 · 181pp · 72,663 words

Upstream: The Quest to Solve Problems Before They Happen

by Dan Heath · 3 Mar 2020

Tools of Titans: The Tactics, Routines, and Habits of Billionaires, Icons, and World-Class Performers

by Timothy Ferriss · 6 Dec 2016 · 669pp · 210,153 words

Doing Good Better: How Effective Altruism Can Help You Make a Difference

by William MacAskill · 27 Jul 2015 · 293pp · 81,183 words

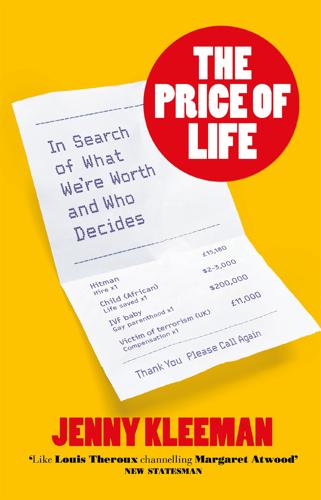

The Price of Life: In Search of What We're Worth and Who Decides

by Jenny Kleeman · 13 Mar 2024 · 334pp · 96,342 words

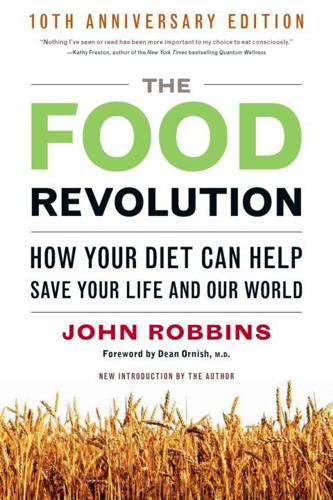

The Food Revolution: How Your Diet Can Help Save Your Life and Our World

by John Robbins · 14 Sep 2010 · 468pp · 150,206 words