Apollo 13

description: a 1970 NASA mission that suffered a critical failure but returned safely to Earth

152 results

Apollo 13

by

Jim Lovell

and

Jeffrey Kluger

Published 14 Jun 2000

Without the considerable talents and limitless enthusiasm of Joy Harris, of the Lantz-Harris Literary Agency, and Mel Berger, of the William Morris Agency, there would have been no Apollo 13. And without the practiced eye and editorial guidance of John Sterling of Houghton Mifflin Company, the Apollo 13 we initially envisioned would never have been improved and focused into the Apollo 13 that ultimately appeared. While nearly all of our thanks are extended jointly, each of us would also like to acknowledge some folks individually. Jim Lovell could never have made it through Gemini 7, Gemini 12, Apollo 8, and, especially, Apollo 13, without the love and support of Marilyn, Barbara, Jay, Susan, and Jeffrey, and could never have undertaken the effort to tell the story of those flights without the same love and support of the same people.

…

Contents * * * Title Page Contents Copyright The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13 Frontispiece Dedication Preface Prologue 1 2 3 4 5 6 Photos 7 8 9 10 11 12 Epilogue Apollo 13 Mission Timeline Apollo 13 Dramatis Personae The Manned Apollo Missions Authors’ Notes Index About the Authors Connect with HMH Preface copyright © 2000 by Jim Lovell and Jeffrey Kluger Copyright © 1994 by Jim Lovell and Jeffrey Kluger All rights reserved For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to trade.permissions@hmhco.com or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

…

But when you find yourself in space, eyeball to eyeball with death, and through imagination, resourcefulness, and flat-out fine flying see to it that death is the one who blinks, you’ve achieved something truly extraordinary. Measured by that yardstick, the mission of Apollo 13 deserved to be thought of as far more than the forgotten child of NASA’s lunar program; it might well have been thought of as its favorite son. That was the point we hoped to make and the tale we hoped to tell when we set about writing Lost Moon (now Apollo 13) in 1992. In a popular environment that was intolerant of the fallibility of human beings and their machines and was content to limit space exploration to paddling about in the familiar harbor of near-Earth orbit, the tale of Apollo 13 would not have had much appeal. But by the final decade of the millennium—and the fourth decade of humanity’s travels in space—that had already begun to change.

Go, Flight!: The Unsung Heroes of Mission Control, 1965-1992

by

Rick Houston

and

J. Milt Heflin

Published 27 Sep 2015

See Alignment Optical Telescope (AOT) Apollo 1, 95–101 Apollo 8, 110–21 Apollo 9, 135–42 Apollo 10, 135, 142–50 Apollo 11, xi–xiv, 151–79 Apollo 12, 180–98 Apollo 13, 2–3, 199–47 Apollo 13 (documentary), 245, 311 Apollo 13 (motion picture), xv, 26, 203, 312–14 Apollo 14, 250–60 Apollo 15, 260 Apollo 16, 268 Apollo 17, 4, 268, 273, 277–78 Apollo EECOM (Liebergot), 216, 265, 315 Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package (ALSEP), 256–57 Apollo program, 17, 96–97, 274, 277 Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, 260 Aquarius (Apollo 13 Lunar Module), 207, 218, 220, 223–24, 226–29, 234, 237 Arabian, Donald D., 38 ARIA. See Advanced Range Instrument Aircraft (ARIA) Armstrong, Lawrence L.

…

Flight controllers during Apollo 9 landing and recovery operations 12. Snoopy and Charlie Brown dolls overlook Charlie Duke 13. Jack Garman’s computer alarm cheat sheet 14. Charlie Duke during Apollo 11 landing 15. Dave Reed gets his launch plot board signed 16. Ken Mattingly during Apollo 13 launch 17. Mission control moments before start of Apollo 13 crisis 18. Glynn Lunney and Gene Kranz celebrate Apollo 13 splashdown 19. Sy Liebergot and Bill Moon 20. Charlie Harlan discusses a probe mockup with Gene Cernan and John Young 21. Ed Fendell 22. Neil Hutchinson, Gene Kranz, and Gerry Griffin 23. Apollo 17 Lunar Module Challenger lifts off of the lunar surface 24.

…

A 28 April 1970 article in Fredericksburg, Virginia’s Free Lance-Star about her contributions to the flight of Apollo 13 ran a similar headline, except this one called her a “girl.” The first couple of paragraphs were a far cry from the politically correct climate of the next century. “A former beauty contestant whose name has been linked romantically with Astronaut John Swigert Jr., played a key role in bringing the Apollo 13 crew home safely,” wrote reporter Will McNutt. “Bachelor girl Poppy Northcutt, 26, a tall, winsome blonde mathematician, was the only female working inside the Mission Control Center during the Apollo 13 emergency.” The story went on to detail the fact that Northcutt had no plans for marriage, dished more on her supposed romance with Swigert—there was none, according to the writer—and how she was a “popular, fun-loving girl” who liked to “swim, dance, ski or sail.

A Man on the Moon

by

Andrew Chaikin

Published 1 Jan 1994

Six hundred feet away, on the crater rim, the lunar module Intrepid looks like a tiny scale model. To its right is a collapsible communications antenna. APOLLO 13 above left: Ken Mattingly, grounded by NASA doctors three days before launch because of a suspected case of German measles, studies a flight plan in mission control. For now, Apollo 13 is still a normal mission. above right: Soon after the explosion of an oxygen tank aboard Apollo 13, astronauts and flight controllers study data in mission control. From left: Tony England, flight controller Raymond Teague, Joe Engle, Gene Cernan, Ed Mitchell, Al Shepard, and Ron Evans.

…

He could have gone on until NASA said he was too old to fly any more, but he knew that when he came back from Apollo 13 he would face a long wait, perhaps several years, before he flew again. Well aware of the astronauts still waiting for their first flights, he decided he would not get back on line for a fifth. Apollo 13 would be a great finale to a long spaceflight career. Like every commander, Lovell wanted his mission to stand out, but he couldn't see why people would remember the third lunar landing. And that was fine with him. He wanted badly to land on the moon, and he was glad for the chance to make a contribution to science. The Apollo 13 mission patch read “Ex Luna, Scientia” —From the moon, knowledge—and Lovell thought of that when he christened his lunar module Aquarius, after the god of the ancient Egyptians who brought life to the Nile Valley (not to mention the popular song from the Broadway musical Hair).

…

In an out-of-court settlement, the Justice Department directed NASA to return the covers, and according to Worden, one official told him that the Apollo 15 crew had committed no wrongdoing by their actions regarding the first-day covers before and after their flight. 562 he would rather have been the last man to walk on the moon: Many astronauts have shared Anders’s regret at not having walked on the moon. For Apollo 13’s Fred Haise, the disappointment was compounded by the experience of a failed mission. But Haise’s commander has a different attitude. If Jim Lovell could pick the flights he would like to be on, even with clear hindsight, one of them would be Apollo 13. It doesn’t take anything extraordinary to do what is expected of you, Lovell says, but fighting for his life 200,000 miles from home tested him in ways that even a lunar landing wouldn’t have. Says Lovell, “Apollo 13 was a test pilot’s mission.” He regrets that the Society of Experimental Test Pilots never recognized him and his crew for their performances.

"Live From Cape Canaveral": Covering the Space Race, From Sputnik to Today

by

Jay Barbree

Published 18 Aug 2008

Flight controllers took the temperature of Apollo 13’s life-support systems. Liquid oxygen had to remain at a critical 297 degrees below zero, and the liquid hydrogen tanks even colder, an unbelievable 423 degrees below, if the fuel cells were to continue supplying power and oxygen and water to the astronauts. Apollo 13 continued its wild flight toward the moon. It looked as if the assembly of space vehicles could be breaking apart. The alarms wailed, the lights flashed while the crew and Mission Control clung to the belief that electrical glitches were causing the problems. No one wanted to believe Apollo 13’s astronauts were in mortal peril as the three quickly moved through their emergency list.

…

The guidance platform was a collection of gyroscopes and instruments needed to keep the spaceship aligned precisely with Earth and the moon—to keep Apollo 13’s location known to Mission Control every moment of the flight. Even though Apollo 13’s crew would now be sustained by the lunar module, the astronauts would need to return to the cold, damp, hibernating command ship for food and bathroom facilities. It promised to be an uncomfortable ride. Flight director Gene Kranz and his team decided to use the lunar-module descent engine for needed propulsion. They worked out a couple of rocket burns that should bring the Apollo 13’s crew safely home: “We’ll go for a brief burn a few hours from now before they reach the moon.

…

Mission Control was a church of silence. Squawk boxes crackled. A tracking aircraft over the Pacific radioed. It had picked up a signal from Apollo 13. No one cheered. Not yet. What about the heat shield? Had it held? Or was it damaged in the explosion? And what about the parachutes? Had they opened? Apollo 13 broke through a cloud deck two thousand feet above the ocean riding beneath three huge orange-and-white parachutes. Mission Control went mad with relief, applause, and cheering. Unbelievably, Apollo 13 splashed down only three miles from the Iwo Jima. Jim Lovell and crew were lifted by helicopter to the deck of their prime recovery ship, and splashdown parties worldwide burst into wild and thankful celebrations.

Moon Shot: The Inside Story of America's Apollo Moon Landings

by

Jay Barbree

,

Howard Benedict

,

Alan Shepard

,

Deke Slayton

and

Neil Armstrong

Published 1 Jan 1994

If you continue to go along without any heart episodes, well . . . ” “Well, what?” Deke demanded. Berry looked up as if he could see beyond the sky, then back to Deke. “Maybe, my friend, just maybe . . . ” Maybe . . . CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE Apollo 13: NASA’s Finest Hour IT WAS TIME TO STIR the frigid broth deep inside Apollo 13. Four large circular tanks contained super-cold liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen, the “soup of life” for the ship and its crew of three. Apollo 13 was a vessel of long-range exploration, and tiny fans stirred the tanks of liquid oxygen and hydrogen that kept its three astronauts supplied with breathing air, drinking water, and electricity for their ship.

…

The intense heat caused a buildup of internal pressure which quickly exploded, shredding the tank’s structure. Its dome blew outward with the effect of a shotgun blast, destroying vital lines and systems. Apollo 13 was a ship torpedoed from within. Valves twisted shut, blocking the critical flow of vital liquids as the blast shredded everything in its path. The side of Apollo 13’s service module blew out, and the spacecraft began to die. Until this moment, fifty-five hours and fifty-five minutes after Apollo 13 had been launched from Cape Canaveral, Commander Jim Lovell had judged their Apollo flight as “the smoothest flight of the program.” It had been so uneventful that only a few hours before, CapCom Joe Kerwin had radioed Lovell, complaining, “We’re bored to tears down here.”

…

It didn’t seem possible with a ship that had been functioning perfectly. Fred Haise, the third member of Apollo 13, said to his crewmates, “Maybe we got hit by a meteorite.” The entire spacecraft continued to vibrate badly. All signs indicated that Apollo 13 was breaking apart. The clamor of alarms and flashing lights continued while the crew, and Mission Control, under the direction of veteran Flight Director Gene Kranz, clung to the belief that electrical system glitches were the cause of the crisis indicated by their instruments. They couldn’t accept that Apollo 13 had flown into mortal peril. The astronauts reset their switches, expecting to bring everything back on line.

A Curious Mind: The Secret to a Bigger Life

by

Brian Grazer

and

Charles Fishman

Published 6 Apr 2014

Details here: www.the-numbers.com/person/208890401-Brian-Grazer#tab=summary, accessed October 18, 2014. 3. What parts of the movie Apollo 13 take liberties with what actually happened? If you’re curious, here are a handful of websites that answer the question, including a long interview with T. K. Mattingly, the astronaut who was bumped from the flight at the last minute because he was exposed to German measles: Ken Mattingly on the movie Apollo 13: www.universetoday.com/101531/ken-mattingly-explains-how-the-apollo-13-movie-differed-from-real-life/, accessed October 18, 2014. From the official NASA oral history website: www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/MattinglyTK/MattinglyTK_11-6-01.htm, accessed October 18, 2014.

…

The results have always been surprising, and the connections I’ve made from the curiosity conversations have cascaded through my life—and the movies we make—in the most unexpected ways. My conversation with the astronaut Jim Lovell certainly started me on the path to telling the story of Apollo 13. But how do we convey, in a movie, the psychology of being trapped on a crippled spaceship? It was Veronica de Negri, a Chilean activist who was tortured for months by her own government, who taught me what it’s like to be forced to rely completely on oneself to survive. Veronica de Negri helped us to get Apollo 13 right as surely as Jim Lovell did. Over time, I discovered that I’m curious in a particular sort of way. My strongest sense of curiosity is what I call emotional curiosity: I want to understand what makes people tick; I want to see if I can connect a person’s attitude and personality with their work, with their challenges and accomplishments.

…

I produced a movie called Apollo 13, the true story of what happens when three U.S. astronauts get trapped in their crippled spaceship. I produced a movie called 8 Mile, about trying to be a white rap musician in the black rap world of Detroit. I produced a movie called American Gangster, about a heroin smuggler in Vietnam-era New York. American Gangster isn’t about a gangster—it’s about capability, it’s about talent and determination. 8 Mile isn’t about rap music, it isn’t even about race—it’s about surmounting humiliation, about respect, about being an outsider. Apollo 13 isn’t about aeronautics—it’s about resourcefulness, about putting aside panic in the name of survival.

Never Panic Early: An Apollo 13 Astronaut's Journey

by

Fred Haise

and

Bill Moore

Published 4 Apr 2022

Taylor Designed by Gary Tooth / Empire Design Studio Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Haise, Fred, 1933- author. | Moore, Bill, author. Title: Never panic early : an Apollo 13 astronaut’s journey / Fred Haise with Bill Moore. Identifiers: LCCN 2021053466 (print) | LCCN 2021053467 (ebook) | ISBN 9781588347138 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781588347145 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Haise, Fred, 1933- | United States. National Aeronautics and Space Administration–Biography. | Apollo 13 (Spacecraft) | Astronauts–United States–Biography. | Space flight–History. Classification: LCC TL789.85.H35 A3 2022 (print) | LCC TL789.85.H35 (ebook) | DDC 629.450092 [B]–dc23/eng/20211220 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021053466 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021053467 Ebook ISBN 9781588347145 For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as seen at the end of the image captions.

…

I was the flight director for the successful flight tests of the two lunar modules that Haise developed and tested in the Grumman plant. His description of the Apollo 13 oxygen tank explosion as one of his never panic early experiences relays a close and personal sense of the event. My team and I had faced mission crises before—the Gemini 8 emergency reentry to landing in the West Pacific was the closest call we had ever faced. Apollo 13, however, was a matter of survival. It was as tough a test as could be conceived and put to flight control. If there was any weakness, the team would have crumbled.

…

However, as the launch date approached, we ran segments of flight without any failures to get a feel for the normal mission timeline, without the interruption of things going wrong. In events with the general public, I am often asked how we seemed so controlled in handling the inflight failure on Apollo 13. They were not aware of our training, where dealing with failures was business as usual. Ron Howard, doing his homework before filming the movie Apollo 13, said that he listened to all the air-to-ground transmissions provided by NASA and it never seemed to him that we had a problem. I talked to Jim about expanding the field geology training based on a conversation that I had with astronaut Jack Schmitt.

Thirteen: The Apollo Flight That Failed

by

Henry S. F. Cooper

Published 31 Dec 2013

At the Manned Spacecraft Center, near Houston, Texas, the glow was seen by several engineers who were using a rooftop observatory to track the Apollo 13 spacecraft, which had been launched two days before and was now a day away from the moon and two days from a scheduled moon landing. One of the group, Andy Saulietis, had rigged a telescope to a television set in such a way that objects in the telescope’s field of view appeared on the screen. Above, the sky was clear and black, like deep water, with occasional clouds making ripples across it. Saulietis and his companions—who, incidentally, had no operational connection with the Apollo 13 mission but were following it for a related project—had lost sight of the spacecraft, two hundred and five thousand miles away.

…

However, technology notwithstanding, the men who ply between the earth and the heavens are not doing anything much different from what was done by the explorers who merely used the heavens to steer by. The Apollo 13 astronauts were now in every bit as understandable and distressing a predicament as any seamen aboard a leaky vessel in danger of foundering. This was readily grasped by the estimated third of the world’s population who were following Apollo 13—probably more than had followed any other spaceflight. There was a sort of worldwide shudder of horror, for if these men died they could do so in a way no men ever had before: they could be the first never to return to the dust of this planet.

…

Before going to sleep, one of them told one of the doctors he just didn’t know how much longer they could have kept on going. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I WANT TO THANK those astronauts and flight controllers of Apollo 13 who gave me their stories and who later took the time to make sure I got them straight. Many others have had a hand in this book. In particular, William Shawn, the Editor of The New Yorker, first had the idea that the Apollo 13 mission might offer the best glimpse into the anatomy of a spaceflight and especially into the workings of “those men who sit at those desks” in the Mission Control Room—the flight controllers, whom nobody seemed to know much about.

Failure Is Not an Option: Mission Control From Mercury to Apollo 13 and Beyond

by

Gene Kranz

Published 7 Jan 2000

The song had temporarily replaced “The Stars and Stripes Forever” as my going-to-work music. The version sung by the group called the 5th Dimension was picked up by the Apollo 13 crew and controllers as symbolic of the energy and momentum of the Apollo lunar program. The song’s signature words, “This is the dawning of the Age of Aquarius,” symbolized the first mission of the new decade as well as the challenge and excitement of the increasingly difficult and risky lunar missions. When the Apollo 13 crew named their LM Aquarius, the song moved to the “top of the pops” for the controllers. The CSM was dubbed Odyssey. Lunar exploration began in earnest after the pinpoint landing of Apollo 12.

…

The universal characteristic of a controller is that he will never give up until he has an answer or another option. By the time someone graduated to the front room consoles either he was ready—or he was gone before he got there. The Apollo 13 flight director chemistry was unique. Windler and I were jet fighter pilots; Griffin flew as a radar operator. For the first time we were working together on a mission. Lunney, the fourth flight director, was the last of the original flight dynamics officers, the master of his craft. April 11, 1970, Apollo 13 Milt Windler, a veteran of three Apollo missions, drew the launch flight director’s assignment. He had earned his spurs as a test director in Kraft’s recovery division and not in Mission Control.

…

Since the punch bowls were engraved, the lawyers decided we could keep them.) I think everyone, once in his life, should be given a ticker-tape parade. The Apollo 13 debriefing had few surprises. We learned that the tank failure was due to a combination of a design flaw, mishandling during change-out, a draining procedure after a test that damaged the heater circuit, and a poor selection of the telemetry measurement range for the heater temperatures. The debriefing party at the Hofbraugarten was merciless, beginning with a parody of the mission. The tape prepared by the Apollo 13 backup crew and the CapComs was not for the thin-skinned. The parody began and ended with the “immortal words” Liebergot and I exchanged early in the crisis.

Apollo 11: The Inside Story

by

David Whitehouse

Published 7 Mar 2019

Slayton had to get approval for flight crew assignments from George Mueller, who rejected the Apollo 13 assignments saying the crew was too inexperienced. Slayton then asked Jim Lovell, the backup commander for Apollo 11, and slated to command Apollo 14, if his crew would be willing to fly Apollo 13 instead. He agreed, and Shepard’s inexperienced crew was assigned to the Apollo 14 so that they could get more training. Neither Shepard nor Lovell expected there would be much difference between Apollo 13 and Apollo 14. The failure of Apollo 13 meant that Apollo 14 was delayed until 1971, so that modifications could be made to the spacecraft.

…

We were looking specifically for good coverage of proposed future landing sites, especially Fra Mauro, which was then scheduled for Apollo 13. That’s a rough surface, and we wanted to get the highest resolution photos we could so that the crew of the Apollo 13 mission would have the best training information they could get. As 1970 dawned, so the Apollo program began to diminish. On 14 January NASA announced the cancellation of Apollo 20, which had been scheduled to land near Surveyor 7 in Tycho crater. A day later, writing in the New York Times, George Low said that the decision would waste the nation’s development. Nor, for different reasons, would the astronauts of the ill-fated Apollo 13 ever land on the lunar surface.

…

Keith 1, 2 Glushko, Valentin 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Goddard, Robert 1 Gordon, Dick 1, 2, 3 Göring, Hermann 1 Greaves, Jim 1 Grechko, Georgi 1 Grishin, Lev 1 Grissom, Gus 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Grizodubova, Valentina 1 Gromov, Mikhail 1 Grumman Aerospace Corporation 1, 2, 3 ‘Gumdrop’ (Apollo 9 Command Module) 1 H Hadley Rille 1 Hagerty, James C. 1 Haise, Fred 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 quotes 1, 2 Haise, Mary 1 heat shields 1, 2, 3 Himmler, Heinrich 1, 2, 3 Hitler, Adolf 1, 2, 3 Hodge, John 1, 2 Holmes, Brainerd 1, 2 Hornet, USS 1 Houbolt, John 1 House, William F. 1 House Rock 1 Humphrey, Hubert 1, 2 Huntsville (Alabama) 1, 2 I Igla docking system 1, 2 Inter-Continental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) 1 International Geophysical Year (IGY) 1, 2, 3 ‘Intrepid’ (Apollo 12 Lunar Module) 1 Irwin, Jim 1 Ivanovsky, Oleg 1 J J-2 engines 1 Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) 1 Johnson, Lady Bird 1 Johnson, Lyndon B. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 quotes 1, 2 and space race 1, 2, 3 Jupiter-C rocket 1, 2, 3 K Kamanin, Nikolai 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 quotes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and Soyuz program 1, 2 and Voshkod project 1, 2 Kammler, Hans 1 Katys, Georgi 1 Keldysh, Mstislav 1, 2 Kelly, Fred 1 Kennedy, Jackie 1 Kennedy, John F. letter to 1 and Moon mission 1, 2, 3, 4 note at grave 1 and space race 1, 2, 3 Kennedy, Robert 1 Kerwin, Joe 1, 2 Khrunov, Yevgeny 1 Khruschev, Nikita 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and lunar probes 1 and manned flights 1, 2, 3, 4 Khruschev, Sergei 1 King, Martin Luther 1 Kistiakowsky, George 1 ‘Kitty Hawk’ (Apollo 14 Command Module) 1 Kolyma death camp 1 Komarov, Vladimir 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Kondratyuk, Yuri Vasilyevich 1 Korolev, Sergei background 1 death 1, 2 and first manned flight 1, 2, 3, 4 health problems 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 imprisonment 1 and lunar probes 1, 2 and rockets 1, 2, 3 and satellites 1, 2 and Voshkod project 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and Vostok program 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Korp, Christina 1 Kosygin, Alexei 1 Kraft, Chris 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Kranz, Gene 1, 2, 3 and Apollo 11 1 and Apollo program 1, 2 and Gemini program 1, 2 quotes 1, 2, 3, 4 on Apollo 11 1 on Apollo 13 1, 2, 3 Kuznetsova, Tatyana 1 L L1 Moon program 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 L3 project 1, 2 Laika (Kudryavka) 1 Leonov, Aleksai 1, 2, 3, 4 ‘Liberty Bell 7’ (Mercury capsule) 1 Liebergot, Sy 1 lifeboat, Lunar Module as 1 Lindbergh, Charles 1, 2 Lisa (dog) 1 lithium hydroxide 1, 2 Lousma, Jack 1, 2 Lovelace, William 1 Lovell, Jim Apollo 8 1, 2, 3 and Apollo 11 1 Apollo 13 1, 2, 3, 4 and Armstrong 1 Gemini 7 1, 2 quotes 1, 2, 3, 4 on Apollo 13 1, 2, 3, 4 recruitment 1, 2 Lovell, Marilyn 1 Low, George 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Luna probes 1, 2, 3 Luna 15 1, 2, 3 Lunar Landing Reserve Vehicle (LLRV) 1 Lunar Module (LM) 1, 2, 3, 4 Apollo 8 1, 2 Apollo 9 (‘Spider’) 1 Apollo 10 (‘Snoopy’) 1, 2 Apollo 11 (‘Eagle’) 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 communication problems 1, 2 computer alarms 1 landing 1, 2 lift-off and docking 1 Apollo 12 (‘Intrepid’) 1 Apollo 13 (‘Aquarius’) 1, 2, 3 Apollo 14 (‘Antares’) 1, 2 Apollo 15 (‘Falcon’) 1 Apollo 17 (‘Challenger’) 1, 2 first flight test 1 as lifeboat 1 LM-4 1 LM-5 1 lunar-orbit rendezvous 1, 2 Lunar Orbiter missions 1 Lunar Orbiter 1 1 Lunar Orbiter 2 1 Lunar Orbiter 4 1 Lunar Orbiter 5 1 Lunar Orbiter spacecraft 1 lunar probes 1, 2 Lunar Rover 1, 2, 3, 4 lunar scoop spacecraft 1 Lunney, Glynn 1, 2 M MacLeish, Archibald 1 Man in Space films 1 Manned Spacecraft Center 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Mare Cognitum 1 Mare Imbrium 1 Mariner spacecraft 1 Mars 1 mass concentrations (mascons) 1 Mathews, Charles 1 Mattingly, Ken 1, 2, 3 Mayer, Johnny 1 McDivitt, Jim 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 recruitment 1 McDivitt, Patricia 1 McDonnell, Jim 1 McDonnell Aircraft Corporation 1, 2 McElroy, Neil 1 Medaris, John B. 1 Ménière’s disease 1, 2 Menshikov 1 Mercury 13 1 Mercury program 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Mercury Seven 1, 2, 3 Merritt Island 1 MET 1 Mishin, Vasili 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Mitchell, Edgar 1 Modular Equipment Stowage Assembly (MESA) 1 Modularized Equipment Transporter (MET) 1 Mondale, Walter 1 Moon composition data collection 1 dark side 1 first artificial satellite 1 first probe to strike 1 first soft landing 1 geology 1 magnetic field 1 moonwalks 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Moore, John 1 Morrow, Lola 1 Mueller, George 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Muller, Paul 1 N N1 booster 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 NASA creation 1, 2 and government cuts 1 NASA Center 1 National Air and Space Museum 1 Nedelin, Mitrofan 1, 2, 3, 4 Nelyubov, Grigori 1, 2, 3, 4 New Nine 1 night-time launch, first 1 Nikolayev, Andriyan 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Nixon, Richard M. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 North American Aviation 1, 2, 3 North American Rockwell 1, 2 North Ray Crater 1 O Oberammergau 1 Oberth, Hermann 1, 2 Object D 1 Obraztsov (Academician) 1 Ocean of Storms 1, 2, 3 ‘Odyssey’ (Apollo 13 Command Module) 1, 2, 3 O’Hara, Dee 1, 2 ‘one small step’ 1, 2 Outer Space Treaty 1 P Paine, Thomas 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Pashkov, Giorgi 1 peace 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Peenemunde 1, 2 Petrone, Rocco 1 Petrovsky, Boris 1 Phillips, Sam 1, 2 Pickering, William 1 Pioneer probes 1 Pioneer 1 1 Pioneer 2 1 Ponomareva, Valentina 1, 2, 3, 4 Popovich, Marina 1 Popovich, Pavel 1, 2, 3 Powers, Shorty 1 Presidential Medal of Freedom 1 Propst, Gary 1 Proton rocket 1, 2, 3, 4 R R-5 rocket 1 R-7 rocket 1, 2, 3, 4 R-16 rocket 1 Ranger spacecraft 1 Redstone rocket 1, 2, 3 regolith 1 Roosa, Stuart 1 S satellites early development 1 first in orbit 1 see also Explorer 1; Sputnik Saturn rocket 1 Saturn 1B 1 Saturn 5 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Savitskaya, Svetlana 1 Schirra, Walter (Wally) 1, 2 Apollo 7 1 first space flight 1 Gemini 6 1 quotes 1, 2, 3 Schmitt, Harrison 1 Schweickart, Russell 1 Scott, David (Dave) 1, 2 Apollo 15 1 Paris Air Show 1 quote 1 Sea of Rains 1 Sea of Tranquillity 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Seamans, Robert (Bob) 1, 2, 3 Sedov, Leonid 1, 2 See, Elliot 1 seismic response experiments 1 Service Module (SM) 1, 2 Apollo 10 1, 2 Apollo 13 1, 2 Apollo 16 1 test in space 1 Service Propulsion System 1 Severin, Guy 1 Shatalov, Vladimir 1, 2 Shea, Joe 1 Sheer, Julian 1 Shelley, Percy Bysshe 1 Shepard, Alan Apollo 14 1 at White House 1 background 1 first space flight 1 and Gemini program 1 Ménière’s disease 1, 2 in Mercury Seven 1, 2, 3 oldest to walk on Moon 1 quotes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Shepard, Louise 1 Shoemaker, Gene 1 Shonin, Georgi 1 ‘Sigma 7’ (Mercury capsule) 1 Sinus Medii 1 Sjogren, William 1 Slayton, Deke and Apollo 1 disaster 1 and Apollo 11 1, 2 Apollo-Soyuz docking mission 1 and astronaut recruitment 1, 2, 3 and astronaut selection 1, 2, 3 and Gemini program 1, 2 grounded 1 in Mercury Seven 1 quotes 1, 2, 3 Smoky Mountains 1 ‘Snoopy’ (Apollo 10 Lunar Module) 1 Society of Experimental Test Pilots 1 solar-wind experiment 1 Solovyeva, Irina 1, 2, 3, 4 Soyuz program 1, 2, 3, 4 Soyuz 1 1 Soyuz 2 1, 2 Soyuz 3 1 Soyuz spacecraft 1, 2 space endurance record 1 Space Shuttle 1 Space Task Group 1, 2 Spacecraft 12 1 spacesuit overheating 1 spacewalks 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 ‘Spider’ (Apollo 9 Lunar Module) 1 Sputnik 1 Sputnik 2 1 Stafford, Tom 1 Apollo 10 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 first Moon landing contender 1 and Gemini program 1, 2, 3 quotes 1, 2 recruitment 1 Stalin, Joseph 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Staver, Robert 1 Stone Mountain 1 Surveyor spacecraft 1, 2 Surveyor 3 1, 2 Surveyor 4 1 Surveyor 5 1 Surveyor 6 1 Surveyor 7 1, 2 Swigert, Jack 1, 2, 3 T Taurus-Littrow highlands 1, 2 Teller, Edward 1 Tereshkova, Valentina 1, 2, 3 Thor–Able rocket 1 ‘thumper’ 1 Tikhonravov, Mikhail 1, 2 Titan rocket 1 Titov, Gherman 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Toftoy, Holger 1, 2 tortoises, in space 1 Triplet craters 1 Truman, Harry S. 1 Tsander, Friedrikh 1, 2 Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Tsygan (dog) 1 Tukhachevski, Marshal 1 Tupolev, Andrei 1, 2 Tycho crater 1 Tyulin, Georgi 1, 2 U urination 1 Ustinov, Dimitri 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 V V-2 rocket 1 Van Allen, James 1 Van Allen radiation belts 1 Vanguard rocket 1, 2 Vavilov, Anatole 1 Venus 1 Verne, Jules 1 Vertical Assembly Building (VAB) 1 Vietnam 1 Vishnevsky, Dr 1 Voloshin, Valeri 1 Volynov, Boris 1, 2 von Braun, Magnus 1 von Braun, Wernher 1 and Apollo program 1, 2, 3 at White Sands 1, 2 background 1 and first US manned flight 1, 2 on Russian Moon mission 1 and satellites 1, 2, 3 space travel vision 1 and V-2 1, 2 Voshkod project 1, 2, 3 Voshkod 2 1, 2 Voshkod 3 1, 2, 3 Voshkod 4 1 Voshkod 5 1, 2 Vostok program 1, 2 first manned flight 1 test flights 1, 2, 3 Vostok 3 1 Vostok 4 1 Vostok 5 1 Vostok 6 1 W Webb, James 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and Apollo program 1, 2, 3 departure from NASA 1 and Gemini program 1, 2 quotes 1 and rocket assembly 1 Weird crater 1 Welles, Orson 1 Wendt, Guenter 1, 2 White, Ed 1, 2, 3, 4 White, Patricia 1, 2 Wiesner, Jerome 1, 2 Williams, Walt 1 Y Yangel, Mikhail 1, 2 ‘Yankee Clipper’ (Apollo 12 Command Module) 1, 2 Yazdovsky, Vladimir 1 Yeager, Chuck 1 Yegorov, Boris 1 Yeliseyev, Aleksei 1 Yerkina, Zhanna 1, 2 Yesenin, Tolya 1 Yezhov, Nikolai 1 Young, John Apollo 10 1, 2 Apollo 16 1 Gemini 3 1 Gemini 10 1 quote 1 recruitment 1 Z Zond 4 1, 2 Zond 5 1, 2, 3 Zond 6 1 Zvezdny Gorodok 1 The ‘Mercury 7’ astronauts photographed on 9 April 1960.

After Apollo?: Richard Nixon and the American Space Program

by

John M. Logsdon

Published 5 Mar 2015

Low left the meeting with the feeling that “our request for reconsideration on . . . the shuttle would be denied.”23 Richard Nixon, Apollo 13, and Apollo 17 What Low did not know as he met with Weinberger on December 14 was that Richard Nixon was having second thoughts about going ahead with the Apollo 17 mission. The president had somehow gotten the impression that Apollo 17 was even more risky than the three missions scheduled to precede 154 A f t e r A p o l l o? it. Nixon did not want a repeat of the Apollo 13 experience, particularly in mid-1972, when the Apollo 17 launch was then scheduled, not least of all because it would come as he was campaigning for reelection. The neartragedy of Apollo 13 had made a strong impression on the president, and provided the background against which he decided that Apollo 17 should be canceled.

…

Even as they planned how the president would deal with the unfolding crisis, they made sure that his involvement would reflect well on Nixon as a national leader. In the days after the safe return of the Apollo 13 crew, the White House approached Life magazine senior correspondent Hugh Sidey about “doing an inside story on the President’s involvement in and the attitudes, etc. during the Apollo 13 crisis.” It took several months for this suggestion to bear fruit, but eventually Sidey wrote a very positive account, saying that “the near tragedy of Apollo 13, a deeply emotional drama for all Americans, was even more so for the President.” The Apollo astronauts, Sidey suggested, were an “obsession” for Nixon, who viewed them “as more than heroes.”

…

With respect to the plausibility of Reeve’s description of Nixon drinking in his excitement at the successful conclusion of the Apollo 13 mission, there are many accounts of Nixon enjoying alcohol in the evening both as he sat alone reviewing his paperwork and on yacht cruises on the Potomac, but less evidence that Nixon on occasion also drank during the day. 29. Office of the White House Press Secretary, “Remarks of the President upon the Presentation of the Medal of Freedom to the Apollo 13 Mission Operations Team” and “Exchange of Remarks between the President and Captain James Arthur Lovell, Jr., USN, upon the Presentation of the Medal of Freedom to the Apollo 13 Astronauts,” April 18, 1970, Box 61, Papers of Edwin Harper, RNPL. 30. Memorandum from Dwight Chapin to H.R. Haldeman, “Apollo 13 – White House Activity,” April 21, 1970, Outer Space-3 Files, RNPL; Hugh Sidey, “Marshaling the Good Guys,” Life, August 21, 1970, 28. Notes 323 31.

Apollo

by

Charles Murray

and

Catherine Bly Cox

Published 1 Jan 1989

As the finishing touch, Arabian took an identical O2 tank, subjected it to exactly the sequence of events that he believed to have caused the Apollo 13 anomaly, and produced exactly the same result. This is what had happened: In October 1968, when the O2 Tank 2 used in Apollo 13 was at North American, it was dropped. It was only a two-inch drop, and no one could detect any damage, but it seems likely that the jolt loosened the fill tube that put liquid oxygen into the tank. In March 1970, three weeks before the flight, Apollo 13 underwent its Countdown Demonstration Test that, like all C.D.D.T.s, involved loading all the cryos. When the test was over, O2 Tank 2 was still 92 percent full, and it wouldn’t detank normally—probably because of the loose fill tube.

…

Despite the controllers’ optimism, which to some degree was part of their job description, the design engineers were right about how closely the margins had been shaved. A senior engineer in the Test Division, speaking just a few days after Apollo 13 had landed, said that when he heard the news about the accident he assumed the Apollo 13 crew were goners. “If you had asked [before the accident] what would happen if we lost both oxygen tanks fifty-eight hours into the mission, we’d have said, ‘Well, you can kiss those guys goodbye.’” 4 Each of the major participants in Apollo 13 remembered a different moment that, to him, represented ultimate crisis. For Lunney it was the final few minutes of the transfer from Odyssey to Aquarius.

…

(Courtesy of Sy Liebergot) We can’t be sure, but this photograph was probably taken about an hour into the crisis on Apollo 13, as Don Arabian outlined the minimum voltages for operating the C.S.M. equipment to Gene Kranz. Sam Phillips (seated), head of the entire Apollo Program, watches. Glynn Lunney during the transfer of the crew into the LEM after the Apollo 13 explosion. Those surrounding Lunney include Chuck Dieterich (behind Lunney), Jerry Bostick (face partially hidden), Bill Tindall (seated), and Chris Kraft (with cigar). (NASA) Odyssey splashes down safely at the end of Apollo 13. Gerry Griffin, Gene Kranz, and Glynn Lunney lead the cheering.

Into the Black: The Extraordinary Untold Story of the First Flight of the Space Shuttle Columbia and the Astronauts Who Flew Her

by

Rowland White

and

Richard Truly

Published 18 Apr 2016

Combining outstanding technical ability with an easygoing, genial nature, Freddo was a dependable, popular figure inside the Astronaut Office. To his delight, he was assigned the job of lunar module pilot on Apollo 13. The launch on April 11, 1970, wasn’t entirely uneventful. The second-stage center engine experienced an unstable fuel flow which caused it to pogo, sending a powerful, persistent vertical chug resonating through the stack. It was enough to trip out an accelerometer that shut down the engine before the vibration could do any more damage. But soon that was behind them. Still able to make orbit, Apollo 13 was on its way to the moon. Haise was alone in the lunar module, Aquarius, packing away equipment he, Jim Lovell (the mission’s commander) and Jack Swigert (the command module pilot) had used to film a TV broadcast back to Earth.

…

Then the crew discovered that the second oxygen tank was leaking. • • • In the glassed-off VIP area at the back of Mission Control, John Young had been watching the television footage beamed back from the spacecraft with the Apollo 13 wives. Young was commander of the mission’s backup crew. Watching Jack Swigert had not been part of the plan. Until just three days earlier, Swigert had been Young’s own command module pilot until a fear that the Apollo 13 primary CM pilot, T. K. Mattingly, might have contracted German measles had, despite Young’s resistance, seen the two crewmen swapped. At the end of the broadcast, Young had said good-bye to Jim Lovell’s wife, Marilyn.

…

On that basis, even if they ran out of water five hours before they reentered, Haise and his crewmates were going to make it home. An exhausted Haise was told by Lovell to try to get some sleep. But Apollo 13 was hardly out of the woods. Ahead lay two further engine burns, course corrections, half an hour in a communications blackout on the dark side of the moon, near freezing temperatures and, critically, the construction of ad hoc air filters to scrub poisonous carbon dioxide from the cabin—a job not finished before CO2 levels had risen high enough to trigger a master alarm. And yet the crew of Apollo 13 eventually splashed down safely around one thousand miles southeast of Fiji on April 17. In surviving their eight-day mission, Lovell, Haise and Swigert traveled farther from Earth than anyone before or since.

The Last Man on the Moon: Astronaut Eugene Cernan and America's Race in Space

by

Eugene Cernan

and

Donald A. Davis

Published 1 Jan 1998

TV networks, which only a few hours before the explosion had refused telecast time, now stampeded toward the drama of what was happening to Apollo 13. I was later horrified to learn that the Number 2 oxygen tank that exploded was one of those that had been replaced on our Apollo 10 spacecraft. As for the corps of astronauts, we all jumped into this one together. Any pettiness, bias or personal disagreement, anything not directly connected to bringing Apollo 13 back safely was put on the shelf, and everyone threw away their badges of difference. Our three guys were in jeopardy far, far away, and we all fought to get them home. Breathable oxygen soon began to run out in Apollo 13’s command module, which was the crew’s living quarters, and the damaged fuel cells were unable to generate the electricity needed to run the spacecraft.

…

Instead, Deke moved Jim up one flight, with his crew of Ken Mattingly and Fred Haise, to fly Apollo 13. That moved Al back to the open slot on Apollo 14, with another four months to prepare. Neither red-haired Stu Roosa, his command module pilot, nor lunar module pilot Ed Mitchell had yet been in space, so the crew was immediately given the nickname of “The Three Rookies,” a not-so-subtle needle to Al’s ego for having stomped on the rest of us for so many years. By bigfooting Gordo’s chance to fly on Apollo 13, Deke and Al had sure put a dent in the three-mission rotation theory, and the question that occupied my mind was, what next for Tom Stafford, John Young and Gene Cernan?

…

To him, taking the offered CM pilot slot meant that he would just ride in circles around the Moon some more during the flight of 13, while Lovell, as mission commander, and Fred Haise, who replaced Bill as LM pilot, went down to the surface. Anders felt he had done enough lunar orbiting on Apollo 8. And because no one really knew how many flights there would be after Apollo 13, Bill thought the chances of his rotating into a command and an eventual Moon walk were pretty remote. So just as I had passed on the backup LM job, and Mike had turned down a future command, Anders declined the Apollo 13 CM pilot’s job. A perplexed Deke Slayton suddenly had to get used to a bunch of experienced astronauts refusing his offers of Moon trips. Deke asked Anders to help out in the interim by taking a job in Washington with the National Space Council, and Bill reluctantly agreed, with the understanding that he would remain on astronaut flight status and be considered for an assignment that would get him a Moon walk.

The Runaway Species: How Human Creativity Remakes the World

by

David Eagleman

and

Anthony Brandt

Published 30 Sep 2017

New York Times. December 26, 2013. Accessed January 5, 2014. <http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/26/science/in-the-human-brain-size-really-isnt-everything.html?_r=0> NOTES Introduction 1 Gene Kranz, Failure Is Not an Option: Mission Control from Mercury to Apollo 13 and Beyond (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000). 2 Jim Lovell and Jeffrey Kluger, Apollo 13 (New York: Pocket Books, 1995). 3 John Richardson and Marilyn McCully, A Life of Picasso (New York: Random House, 1991). 4 William Rubin, Pablo Picasso, Hélène Seckel-Klein and Judith Cousins, Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1994). 5 A.L.

…

(Barbèy) ref1 Oldenburg, Claes ref1, ref2 Ono, Yoko ref1 open-office plans ref1 “The Open-Office Trap” (article) ref1 The Origins of Continents and Oceans (Wegener) ref1 orthogonal thinking ref1 Otherlab ref1 Otis Elevator Company ref1 “outward bound” model ref1 Painting (1954) (Guston) ref1 Palace of Versailles ref1 Palo Alto innovation center ref1, ref2 parachutes ref1 Paramount ref1 parasols ref1 Parks, Suzan-Lori ref1 Parliament (band) ref1 Patent Office (US) ref1 “Pay-to-See” system ref1 peanut crops ref1, ref2 Pegasus ref1 Pei, I.M. ref1 perfume ref1 Persian carpets ref1 Petit h laboratory (Hermès) ref1 Peugeot Moovie ref1 pharmaceutical industry ref1 Philco ref1 Phillips, Bradford ref1 photocopies ref1, ref2 photography ref1, ref2 Physical (album) ref1 Piazza (Giacometti) ref1 Picasso, Pablo ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8 Les Demoiselles d’Avignon ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 variations on Las Meninas ref1 Pilloton, Emily ref1 Pinter, Harold ref1, ref2 The Pioneers (Cooper) ref1 pixilation, digital ref1 Plantinga, Judy ref1 Playstation, Sony ref1 poetry ref1, ref2, ref3 pointillism ref1 polarization ref1 Pompidou Center (Paris) ref1 Portal, Yago ref1 Porter, Edwin ref1 Portis, Antoinette ref1 possibilities, testing ref1 Postal Telegraph Building (New York) ref1, ref2 precedents ref1 see also history, mining Predicta television ref1 predictability ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 predictions ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 prizes ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 Proctor & Gamble ref1 Project Glass ref1 Proust, Marcel ref1 public reception ref1, ref2 Pulitzer Prize ref1, ref2 Pyramide (Elias) ref1 QWERTY keyboard ref1 Radio Corporation of America (RCA) ref1 Radio Shack advertisement ref1 Raimondi, Marcantonio ref1 Raspberry Pi Foundation ref1 Rauschenberg, Robert ref1 raw materials ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 REALM Charter School ref1 recumbent bicycle ref1 Reggio Emilia institutions ref1 Renaissance ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 repetition suppression ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 “Revolution 9” (song) ref1 rewards ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 prizes ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 Rice University ref1 Richardson, John ref1, ref2, ref3 Riding Around (1969) (Guston) ref1 rigor ref1 RIM ref1 “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” (Coleridge) ref1 risk ref1 arts ref1 creativity practice ref1 encouraging ref1 failure ref1 long time horizons ref1 public reception ref1 Roadable Airplane ref1 Robot B-9 ref1 robotics ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 Rockwell, Norman ref1 Rocky IV (film) ref1, ref2 Rococo art ref1 Rodin, Auguste ref1 Rolling Stone (magazine) ref1 Romeo and Juliet (Shakespeare) ref1 Roosevelt, Eleanor ref1 Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (Stoppard) ref1 Rosie the Riveter (Rockwell) ref1 Rouen Cathedral ref1 Rouen Cathedral, Set 5 (Lichtenstein) ref1 Royal Shakespeare Company ref1 Ruppy the Puppy ref1 “sailing seeds” experiment ref1 Salon des Réfusés ref1 Sand Castle #3 (Muniz) ref1 “sandboxing” ref1 Sanger, Frederick ref1 Sarnoff, David ref1 SceniCruiser ref1 Schleicher, Lowell ref1 Schmidt, Eric ref1 schools ref1 arts, influence of ref1, ref2 audiences ref1 creative capital ref1 imagination ref1 meaningful work ref1 motivation ref1 precedents ref1 prizes ref1 proliferating options ref1, ref2 risk, encouraging ref1 Schubert, Franz ref1 Schulz, Bruno ref1 science blending ref1, ref2, ref3 breaking ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 cultural conditioning ref1, ref2 education ref1 fiction ref1 influence of the arts ref1 Scieszka, Jon ref1 Scofidio, Ricardo ref1 scouting, distances ref1 Scratch software ref1 sea squirt ref1 seeking ref1 Semper, Max ref1 Senz umbrella ref1 September 11, 2001 ref1 Serra, Richard ref1 Seurat, Georges ref1 70/20/10 rule (Google) ref1 Shadow Torso (Rodin) ref1 Shakespeare, William ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8 Shelley, Mary ref1 Shelley, Percy Bysshe ref1 Sheppard, Sheri ref1 Sherlock (tv) ref1 ShipIt Days (Atlassian) ref1 shipping ref1 “The Shipwreck” (Falconer) ref1 Shockley, William ref1 Short, Bobby ref1 Shrinky Dinks ref1 Shuttlecocks (Oldenburg/van Bruggen) ref1 Siemens ref1 silk ref1 Simon (smartphone) ref1 simulating outcomes ref1 see also future Siri ref1 Sistine Chapel ref1 skeuomorphs ref1, ref2 smartphones ref1, ref2, ref3 Blackberry ref1 iPhone ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 Smets, Gerda ref1, ref2 Snowboard Bicycle ref1 Sobel, Dava ref1 social enhancement ref1 Solyndra ref1 Sony Playstation ref1 Sony Walkman ref1 “A Sound of Thunder” (short story) (Bradbury) ref1 SpaceShipOne (Mojave Aerospace) ref1 speculation ref1 Sphinx ref1 spiders ref1 Sprague, Frank J. ref1 stadiums ref1 Starck, Philippe ref1 Starkweather, Gary ref1 steam engine ref1 Still Life with Violin and Pitcher (Braque) ref1 Stoppard, Tom ref1 Stradivari, Antonio ref1 Stradivarius violins ref1 streamlining ref1 The Street of Crocodiles (Schulz) ref1 A Study in Scarlet (Conan Doyle) ref1 A Study in Pink (tv) ref1 Stueckelberg, Ernst ref1 Subscribervision service ref1 Sun Microsystems ref1 Super Mario Clouds (Arcangel) ref1, ref2 super-font ref1 superheroes ref1 surprise ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6 each other ref1, ref2, ref3 sweet potatoes ref1 sweet spot ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 Swift, Philip K. ref1 Swigert, Jack ref1, ref2 symmetry, visual ref1 Symmetry 454 (calendar) ref1 synecdoche ref1 Szilard, Leo ref1 Szotyńscy and Zaleski (company) ref1 The Taking of Pelham 123 (film) ref1 Tata ref1 Tate, Nahum ref1 tech box (IDEO) ref1 technology bending ref1 blending ref1 breaking ref1 education ref1, ref2 flexibility ref1 proliferating options ref1 testing possibilities ref1, ref2, ref3 Telemeter ref1 television (tv) ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7 Teller, Astro ref1 Teller, Edward ref1 three Bs see also bending; blending; breaking ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7 Three Flags (Johns) ref1 Three Studies for Portraits (including Self-portrait) (Bacon) ref1 3M Corporation ref1, ref2 300 (film) ref1, ref2 Tilman, Congressman John Q. ref1 time bending ref1 blending ref1 breaking ref1 “end of time” illusion ref1 release medications ref1 sharing ref1 timelessness ref1 Time (magazine) ref1 Titled Arc (Serra) ref1 To B.W.T. (1950) (Guston) ref1 “Today in 1963” (article) (Bel Geddes) ref1 “Tom’s Diner” (song) ref1 “Too Marvelous for Words” (song) ref1 touchscreens ref1 Toyota Corporation ref1 Toyota FCV Plus ref1 Toyota i-Car ref1 transistors ref1 “transitron” ref1 The Travelers (Catalano) ref1 Tree of Codes (Foer) ref1 Trehub, Sandra ref1 trolley cars ref1 The True Story of the Three Little Pigs (Scieszka) ref1 Turner, Mark ref1 Twain, Mark ref1, ref2 Twitter ref1 Twombly, Cy ref1 umbrellas ref1 Un dimanche après-midi à l’île de la Grande Jatte (Seurat) ref1 unBrella ref1 universal beauty ref1 universal language ref1, ref2 Unrecognized (Abakanowicz) ref1 vacuum cleaners ref1 van Bruggen, Coosje ref1 van Gogh, Vincent ref1 variation ref1 Vega, Suzanne ref1 Velázquez, Diego ref1 Veloso, Manuela ref1 ventilators ref1 verlan (French slang) ref1 Verna, Tony ref1 Versailles, Palace of ref1 Versatile Extra Sensory Transducer Vest ref1 Viktor & Rolf ref1 Violin Concerto (Beethoven) ref1 visual perception ref1 visual symmetry ref1 Volute ref1 Waldorf institutions ref1 Walker, Shirley ref1 Walkman, Sony ref1 Wall-less House ref1 Walsh, Craig ref1 Warped Building (“Krzywy Domek”) ref1 Washington, Denzel ref1 Water Lilies and Japanese Footbridge (Monet) ref1 Wegener, Alfred ref1, ref2 The Well-Tempered Clavier (Bach) ref1 Wells Fargo bank ref1 West Side Story (musical) ref1 Westinghouse ref1 what-ifs ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7 see also future White Album (album) ref1 White Flag (Johns) ref1 White on White (Malevich) ref1 Whitney, Eli ref1, ref2 Wiles, Andrew ref1 Wilson, E.O. ref1, ref2, ref3 Wilson, John Tuzo ref1 Windows 8 ref1 windshields ref1, ref2 Winehouse, Amy ref1 wing warping ref1 The Winstons (band) ref1 Women of Algiers (Delacroix) ref1 workplace changes ref1 World calendar ref1 World Season Calendar ref1 World Wide Web ref1 World’s Fairs ref1 Wright, Orville ref1 Wright brothers ref1, ref2, ref3 Wyler, William ref1 X research and development (Google) ref1, ref2 Xerox Corporation ref1, ref2 XPrize ref1 X-Space library ref1 Yoko Ono ref1 YouTube ref1, ref2 Zamenhof, L.L. ref1 Zen gardens ref1 zombies ref1, ref2 NOTES Introduction 1 Gene Kranz, Failure Is Not an Option: Mission Control from Mercury to Apollo 13 and Beyond (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000). 2 Jim Lovell and Jeffrey Kluger, Apollo 13 (New York: Pocket Books, 1995). 3 John Richardson and Marilyn McCully, A Life of Picasso (New York: Random House, 1991). 4 William Rubin, Pablo Picasso, Hélène Seckel-Klein and Judith Cousins, Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1994). 5 A.L.

…

The creative company 12. The creative school 13. Into the future Acknowledgments Image Credits Bibliography Notes Index INTRODUCTION WHAT DO NASA AND PICASSO HAVE IN COMMON? Several hundred people scramble in a control room in Houston, trying to save three humans ensnared in outer space. It’s 1970 and Apollo 13 is two days into its moonshot when its oxygen tank explodes, spewing debris into space and crippling the craft. Astronaut Jack Swigert, with the understatement of a military man, radios Mission Control. “Houston, we’ve had a problem.” The astronauts are over 200,000 miles from Earth. Fuel, water, electricity and air are running out.

Light This Candle: The Life & Times of Alan Shepard--America's First Spaceman

by

Neal Thompson

Published 2 Jan 2004

And they had to quickly become geology experts, training in deserts and canyons to learn how to identify rocks and minerals, which they’d have to collect on the moon, and to practice walking in their bulky space suits across rocky, sandy moonlike terrain. There simply wasn’t enough time for Shepard to catch up and be unambiguously prepared to command Apollo 13, which was scheduled for an early 1970 launch, less than a year away. Slayton had no choice but to pull Shepard off Apollo 13. But instead of giving the flight to Cooper, Slayton asked Jim Lovell—currently assigned to Apollo 14—if he could take Apollo 13. “Sure, why not?” Lovell said. “What could possibly be the difference between Apollo 13 and Apollo 14?” Shepard also saw little difference between the flights. His notorious impatience aside, he was thrilled to have gotten any flight to the moon.

…

Finally, with a billion people around the world glued to radios and televisions, Apollo 13’s haggard crew crawled back into the cold, clammy command module, which Lovell felt looked “forlorn and pitiful,” and separated from Aquarius. “She was a good ship,” Lovell reported with a catch in his voice. Sixty tension-filled minutes later, Apollo 13 was bobbing safely in the Pacific. Incredibly, they had landed within three miles of the recovery ship, USS Iwo Jima, the most accurate landing of the entire space program. Weeks later Shepard met with Jim Lovell back in Houston, and Lovell asked Shepard how he felt now about losing Apollo 13. It would become a persistent joke between Shepard and Lovell.

…

page 399, “It’s something I believe in”: John Noble Wilford, “Apollo 14 Crew Is Fit and Ready,” The New York Times (January 9, 1971), p. 4. page 400, [Training in Bavaria, Germany]: Author interview with Gene Cernan. pages 401–402, [Mexican prostitutes]: Ibid. pages 403–404, [Apollo 13 scenes]: Lovell, Apollo 13; Barbree et al., Moonshot. page 404, “quit worrying and get some sleep”: Barbree et al., Moonshot, p. 270. page 404, “forlorn and pitiful”: Ibid., p. 271. page 404, “She was a good ship”: Ibid., p. 272. page 404, “Anytime you want Apollo 13 back, Al . . .”: Author interview with James Lovell. page 404, [Louise quiet, shy, and sometimes sickly]: Author interview with Dorel Alco Abbot. page 405, “What do you expect from a sailor?”

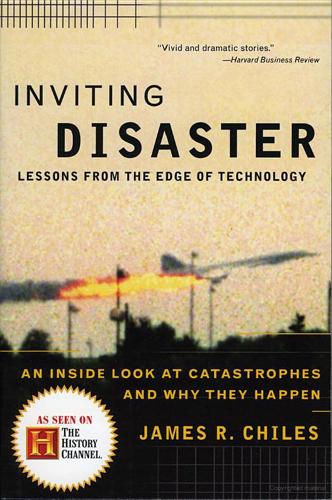

Inviting Disaster

by

James R. Chiles

Published 7 Jul 2008

But in doing so the men at Kennedy missed the only chance they’d ever have to intercept a problem that came very close to snuffing out the astronauts aboard the Apollo 13 flight. As it turned out, the only part of the mission to land on the moon as intended was the fifteen-ton Saturn-IVB third stage, which smashed into the regolith to provide information for a seismometer left on the moon by Apollo 12. We know from the long history of system failures that most problems have been like Apollo 13 in that they offered clues before the full-fledged emergency. “When has an accident occurred which has not had a precursor incident?”

…

While the TV audience thrilled to the way that mission controllers and Apollo crew beat the odds and got the ship back home by rigging up brilliant solutions with the electrical system, navigation, LEM engine, and air purification canisters, the Apollo 13 drama was not something to cheer about. This highly avoidable mishap later strengthened the cause of politicians who opposed Apollo spending and who wanted to end the program before the full suite of flights. And Apollo 13, or its predecessors with the same thermostat problem, could easily have been a complete disaster had the blowout occurred under slightly different circumstances. The lesson that Apollo brought back to Earth is that a quick work-around—in this case the brainstorm that running the heater could empty the oxygen tank fast enough to make the launch deadline—is a good idea only for a machine in which (a) failure doesn’t matter much or (b) somebody first figures out the full effect this method is going to have on the machine.

…

New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1983. Sweet, William. “Chernobyl: What Really Happened.” Technology Review ( July 1989): 43. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Report on the Accident at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Station. Washington, D.C.: U.S. General Printing Office, 1987. Chapter 8 Apollo 13 Review Board. Report of Apollo 13 Review Board. Washington, D.C.: U.S. General Printing Office, 1970. Bower, Bruce. “Seeing Through Expert Eyes.” Science News, July 18, 1998, 44. Bradford, Michael. “Near-Miss Analysis Directs Safety Plan.” Business Insurance, September 27, 1999, 3. Cook, George. “Engineers Assume All Responsibility.”

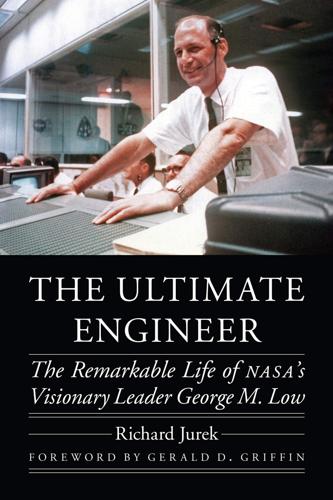

The Ultimate Engineer: The Remarkable Life of NASA's Visionary Leader George M. Low

by

Richard Jurek

Published 2 Dec 2019

“The results of the hearings were quite positive,” Low wrote in his notes, echoing the support Congress showed NASA, McDivitt, the astronauts, and the entire NASA team. “There was no significant criticism of NASA, and only praise for the way NASA handled the Apollo 13 situation. Newspaper and editorial comments ended very soon after these hearings and, insofar as the public and the Congress are concerned, the Apollo 13 situation is just about forgotten.”95 Forgotten. Interest in the space program was at an all-time low until the near tragedy of Apollo 13. The human drama of the event and NASA’s successful handling of it—including allowing the press into mission control to cover every moment of the situation as it unfolded—brought a momentary peak of interest again on a global scale.

…

Always the dirty-hands engineer, he missed being in on the action with Kraft and Slayton; he often found his way to the floor. During the nearly fatal Apollo 13 mission, all hands were made available in the effort to safely bring the astronauts home. Low worked with fellow engineers in mission control and also conducted a number of press conferences to discuss the situation as it unfolded. While those in mission control concerned themselves with Apollo 13’s consumables, he admitted in his notes to being more concerned about their use of the LM as a lifeboat. My main concern during the flight, after the accident, was not the availability of consumables, because this was calculated quite early, but the wellbeing of all of the Lunar Module’s systems.

…

Low at his desk at the MSC in Houston in 1969. Courtesy of the Institute Archives and Special Collections, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York. 26. Low (right, with cigar), Thomas Paine (center of frame), and other NASA officials applauding the successful splashdown of the Apollo 13 mission in the MSC mission controlcenter, located in building 30. Apollo 13 splashed down at 12:07:44 p.m. (CST), 17 April 1970, in the South Pacific Ocean. Courtesy of NASA. 27. Low wearing his T-38 flight jacket during one of his many NASA facility tour visits in the 1970s. Courtesy of the Institute Archives and Special Collections, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York. 28.

Digital Apollo: Human and Machine in Spaceflight

by

David A. Mindell

Published 3 Apr 2008

Christmas Eve mission and, 178 computers and, 104–106, 123–143 (see also Computers) Index Eagle landing and, 1–4, 7–8, 217–232 human factors and, 217–227 lack of accuracy and, 235 Medal of Freedom and, 232 congressional support of, 96 pilots’ reasons for manual control and, 259 cost of, 5, 106, 109, 143, 251 pitch over and, 220–221 deaths and, 173 powered descent and, 217–220 decision points and, 103 scientist resignations and, 257 early missions and, 174–177 firmware and, 154–157 simulators and, 217, 220 Apollo 12, 261 G&N System Panel and, 148–149, 160 accuracy and, 235–237 Gemini and, 86 Conrad and, 236–243 guidance systems and, 102–114, 174–180, DELTAH and, 237 243 goal of, 235–236 gyro culture and, 96–97 improvements on, 236 human factors and, 14–15, 160–166 (see also landing point designator (LPD) and, 237–238 Human factors) Instrumentation Laboratory and, 96, 105–121 lunar module (LM) of, 236–237 Noun 69 and, 236–237, 242–243 (see also Instrumentation Laboratory) pilots’ reasons for manual control and, 259 J-missions and, 249–250 pitch over and, 238 Kennedy and, 5–7, 12, 61, 91, 95, 104–105, powered descent initiation (PDI) and, 237 107, 111, 134, 251, 270 procedural changes in, 236–237 landings and, 181–215 reaction control system (RCS) and, 237–238 management conflicts and, 133–137 simulators and, 238 optics issues and, 114–119 Polaris and, 104–105, 110 velocity indicator and, 241–242 Apollo 13, 9, 186, 243 project management and, 169–174 Apollo 13 (film), 9 project-oriented histories of, 9–10 Apollo 14, 233 safety requirements and, 134–135 backup systems and, 248–249 simulators and, 2–3, 51, 54 (see also hardware failure and, 243–248 Simulators) pilot skills and, 248–249 social effects of, 8–10 pilots’ reasons for manual control and, 260 software and, 145–180 (see also Software) sole-source contract and, 107–108 pitch over and, 251 powered descent initiative (PDI) and, 245– Apollo 1, 173 Apollo 4, 174–175 Apollo 5, 175–176, 233 Apollo 6, 176 247 Apollo 15, 250 pilots’ reasons for manual control and, 260 pitch over and, 251–255 Apollo 7, 176–177 Apollo 16, 250–251, 255, 260 Apollo 8, 177–180 Apollo 17, 251 Apollo 10, 190, 217, 256 Apollo 11, 9–10, 251, 261 computer alarms and, 221–227 descent orbit insertion (DOI) and, 217–218 pilots’ reasons for manual control and, 260 pitch over and, 258 scientist-astronauts and, 256–257 Apollo 18, 251 Index Armstrong, Neil, 1–3, 213, 241–242, 259 airmen school and, 29, 31 Apollo 11 and, 217–232 337 information flows and, 162–163 Instrumentation Laboratory courses and, 158–159 confusion of, 226 landings and, 181–215 (see also Landings) digital computers and, 87 literature by, 9 Eagle landing and, 217–232 lunar module (LM) design and, 184–186 Gemini and, 85 manual reentry and, 160 gimbal reliability and, 120 masculinity and, 13–14 instrumentation and, 35, 181, 295n53 Johnsville tests and, 70–72 Mercury and, 73–83 moonwalks and, 83, 268–269 Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV) and, pilot transitions and, 161–166 (see also Pilots) 214 replacement of, 158 Medal of Freedom and, 232 rockets and, 65–66 pilot role and, 80 scientist-astronauts and, 256–257 Society of Experimental Test Pilots (SETP) user errors and, 160 and, 224, 226 women and, 13 X-15 and, 49, 58–59, 61 Army Ballistic Missile Agency, 66 Astronomical Guidance course, 101 AT&T, 37 Artificial horizons, 24 Atlas rocket, 18, 72–77 AS-202, 172 Atomic frequency standards, 138 AS-204, 171 Attitude, 47–48, 77 AS-501, 174–175 Adams’s death and, 59–61 ASPO, 134–135, 139 eight ball and, 159 Astronautical Guidance (Battin), 100–101 landing point designator and, 204–206 Astronauts active role of, 65 pitch over and, 251–255 Automation, 6, 12 age of systems and, 38–41 adaptive control systems and, 57–61 automation and, 158–166 airliners and, 267 as calibrators, 105 Apollo and, 92, 94, 105–109, 119–121, 139– computers and, 66, 160–166 142, 177–180, 243, 258 constraints for, 159–160 astronaut input and, 158–166 control and, 65–66 booster rockets and, 72 dangerous actions and, 159–160 deaths of, 173 computers and, 123–143 (see also Computers) Eagle landing and, 221–227 deployable optics and, 117 future of, 263–271 digital autopilot and, 139–142 Gemini and, 86–88 displays for, 165–169 human factors and, 4–8 (see also Human Eagle landing and, 1–4, 217–232 factors) Explorers Club and, 271 landings and, 181–215 (see also Landings) future of, 263–271 lunar module (LM) and, 193–197, 199–201 Gemini and, 83–88 ‘‘go to moon’’ interface and, 160–161 Mercury and, 73–83 pilots and, 17–21, 26, 43, 66–69, 73–83, human interface and, 4–8, 160–166 (see also Human factors) 139–142, 259–260 Soviet space program and, 88–90, 93–94 338 Automation (cont.) stability augmentation system (SAS) and, 55– 57, 60 systems engineering and, 36–41 Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) and, 267 Aviation Index Bennett, Floyd, 241, 251, 300n47 computer alarms and, 225–226 Exceptional Service Medal and, 240 landing design and, 187–188, 192, 207 technical project summation of, 242–243 Bikle, Paul, 90 airmen vs. chauffeur school and, 21–23 Black boxes, 34–36, 39, 54, 57, 135 control and, 17–22 Blackburn, Al, 35, 39–40, 68 faster-and-higher goal and, 44 High Speed Flight Station and, 43–44 Black Friday, 171 Blade Runner (film), 13 Kitty Hawk and, 44 Blair, Charles, 40–41 National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics Blair-Smith, Hugh, 126, 149 (NACA) and, 6, 26–28 Blind flying, 24–26, 53–54 pilot’s role and, 17–21 (see also Pilots) Bode, Henrik, 33 skill and, 22–23 Boeing, 92, 267 stability and, 17–22 Bomarc missile, 18, 61 Aviation Week and Space Technology, 179, 267 Bonestell, Chesley, 111 Borman, Frank, 84, 169, 179 B-2 bomber, 266–267 Boston Globe, 248 B-17 bomber, 75 Boston Herald, 179 B-52 bomber, 47–48, 50, 54, 63 Bowditch, Philip, 114 Bales, Steven, 3, 222 Bronson, Charles, 62 Ballistic flight paths, 44 Brown, Alexander, 101 Barnstormers, 10, 20 BURNBABY, 218 Basic (Apollo computer language), 149 BASIC (Dartmouth computer language), 149 Bush, Vannevar, 98 Butler, Rhett, 28 Bassett, Preston, 43 Battin, Richard, 104, 127, 170, 194 Cape Canaveral, 134 Apollo 8 and, 178 Capsule Communicator (CAPCOM), 218, 222 computer errors and, 232 Carpenter, Scott, 81, 121 decision points and, 103 Centrifuge tests, 70–72 lunar mission and, 102–103 Century series jets, 32–33 orbital transfers and, 101–102 project management and, 170 Cernan, Gene, 251, 256–260 Cessnas, 267 Q-guidance technique and, 100 Chance-Vought, 30 recursive estimation of, 102–103 Charles Stark Draper Laboratories, 96–97 software and, 145–146, 151, 158 Chauffeur school, 21–23 Bean, Alan, 236–237, 240 Becker, John, 44–45 Apollo and, 160–161 X-15 and, 46–49 Bell Aerosystems, 210–211 Cheatham, Donald, 186–187, 204 Bellcomm, 135 Bellman, Donald, 210 Cherry, George, 189 Chilton, Robert, 264 Bell Telephone Laboratories, 37, 263 Apollo computer and, 128 Index guidance systems and, 96, 104–107 pilot role and, 75–77, 91–93 339 analog, 52–54, 57–58 Apollo 4 and, 174–175 Cockpit, The (magazine), 31 Apollo 5 and, 175 Cockpits, 24–29 Apollo 7 and, 177 Cohen, Aaron, 88, 112–113, 136–137, 142 Apollo 11 and, 221–227 Colliers magazine, 111 Apollo 14 and, 243–249 Collier Trophy, 61 astronaut’s view of, 66, 158–166 Collins, Michael, 1, 10, 265 B-2 stealth bomber and, 266–267 Columbia and, 217–218 guidance systems and, 116, 121 Medal of Freedom and, 232 Block I AGC, 123–136, 143, 172 Block II AGC, 136–143, 149, 154, 171, 175– 176 pilot role and, 82, 87, 93 core logic and, 125–126 simulators and, 209 crashes and, 123–124 symbolism and, 11 digital, 62, 87, 139–142 COLOSSUS, 151 displays and, 152, 165–169 Columbia space shuttle, 49, 217–218, 264–265 Eagle landing and, 1–4, 6, 221–232 Command and service module (CSM), 1, 33, 135, 146 electrical noise and, 2–3 embedded assumptions of, 13–14 AGC interface and, 168 ENIAC, 98 Apollo 12 and, 236–237 firmware and, 154–157 COLOSSUS and, 151 FORTRAN and, 99 Columbia and, 217–218 future of, 263–271 digital autopilot and, 139–142 G&N System Panel and, 148–149 docking and, 186, 192–193 Gemini and, 87–88 future of, 265–266 gimbal reliability and, 120–121 general-purpose, 123 ‘‘go to moon’’ interface and, 160–161 guidance systems operation plan (GSOP) for, guidance systems and, 104–106, 114, 123– 151–152 lunar module (LM) and, 186, 192–193 P40 program and, 150 142 human-machine relationship and, 4–8 (see also Human factors) radar and, 191 humidity effects and, 137–138 simulators and, 208–209 IBM 360, 148 software for, 146 Communications, 2, 15, 77 in-flight repair and, 128–130, 137–138, 159 instrument flying and, 25 Eagle and, 221–227 integrated circuits (ICs) and, 125–127 jamming and, 97, 104, 138 keyboards and, 152, 160–161, 165–169 landings and, 190–191, 221–227 landing integration and, 191 teleprinter and, 108–109 Laning and, 99–102 Compasses, 24 MAC project and, 148 Computers, 15 mainframe, 148 AGC, 126–128, 133, 137, 143 (see also AGC [Apollo guidance computer]) Alonso and, 100, 102 Mars probe and, 99–101, 154 mean time between failure (MTBF) of, 130, 133 340 Computers (cont.) memory issues and, 152, 154, 171–172 Index astronauts and, 65–66 backup systems and, 248–249 MicroLogic-based, 125–126 black boxes and, 54 mini, 123 blind flying and, 24 Mod 3C, 124–126 booster rockets and, 71–72 mundane work and, 14 centrifuge tests and, 70–72 NASA choice of, 5–6 chauffeur school and, 21–23 night-watchman circuit and, 124 cockpit design and, 24–29 onboard, 88 pilots and, 1–7, 19–21, 107, 161–166 damping and, 58–61 dangerous actions and, 159–160 Polaris and, 98–99, 125–127 digital autopilot and, 139–142 programmable, 123 display and keyboard (DSKY) unit and, 165– RAM and, 124–125 169 reliability of, 123–143 early Apollo missions and, 174–180 removable modules and, 129 feedback systems and, 33 ROM and, 124–125 first rendezvous in space and, 84–85 simulation development and, 51–54 software and, 129–131 (see also Software) fly-by-wire and, 79, 81, 140, 266 flying qualities and, 26–28 Soviets and, 90 G&N System Panel and, 148–149, 160, 168– space sextant and, 114–115 169 stability and, 19–21 gain and, 51 symbolism of, 12–13 Gemini and, 83–88 systems engineering and, 36–41, 133–137 Gilruth and, 27–28 time allocation and, 149–150 ‘‘go to moon’’ interface and, 160–161 transistors and, 125–130 user errors and, 160 ground, 62, 108–109, 138 (see also Ground control) vacuum tubes and, 130 instrument flying and, 24–25 (see also variable processing speed and, 106 Guidance systems) Whirlwind, 99, 124 Johnsville tests and, 70–73 workload and, 3 landings and, 181–215, 182–186 (see also Configuration control boards, 152 Landings) Conquest of the Moon (von Braun), 67–69 manual maneuvering and, 84–86 Conrad, Pete, 259 computers and, 140, 158 Mercury and, 74, 77–81 new technologies and, 267–268 landings and, 181, 214, 236–243 pilot induced oscillation and, 50–51 Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV) and, primary navigation and guidance system 214 velocity indicator and, 241–242 Control, 17–18 (PNGS) and, 191 reentry, 55–57 rudder pedals and, 79 Adams’s death and, 59–61 simulation and, 2–3, 32, 51–54 adaptive, 57–61, 77 age of systems and, 36–41 software and, 147 (see also Software) Space Task Group (STG) and, 74–77 airmen school and, 21–23 stability and, 19–21 (see also Stability) Index supersonic flight and, 32–36, 44–45 three-axis stick and, 79 X-15 and, 48–51, 54–61 yaw dampers and, 35 341 Eagle and, 223, 229–231 human factors and, 165–169 landings and, 191, 196–197, 204 Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

…

The Apollo Computer 7 Programs and People 8 Designing a Landing 9 ‘‘Pregnant with alarm’’: Apollo 11 43 65 10 Five More Hands On 123 145 181 217 235 11 Human, Machine, and the Future of Spaceflight Notes 273 Glossary 305 Bibliography 307 Index 335 About the Cover Image 361 263 95 Preface and Acknowledgments On June 14, 1966, a robotic spacecraft had just landed on the moon and begun transmitting images to NASA. Project Gemini was drawing to a close, Apollo hardware was beginning to emerge from factories, and Apollo software was experiencing a crisis. And on that day I was born. I do not remember the first lunar landing of Apollo 11 or the drama of Apollo 13, but I do remember watching the later launches and landings on television. In that sense, I am among the first of a generation—those for whom lunar landings have always been a fait accompli—for whom the twentieth century’s greatest technological spectacle was an accomplishment rather than a dream.

…

Of the twelve men who walked on the moon, at least eight have written, or have had ghostwritten, some kind of memoir, and numerous other Apollo crew members have chimed in as well.8 Lately the ground controllers have gotten into the act, with similar, though delayed, levels of public interest and attention.9 One account used interviews with engineers to tell the story of the technical people behind the scenes.10 A few of Apollo’s engineers have added their own stories as well.11 Numerous other popular accounts cover the project from a variety of angles; one was even made into a TV miniseries, following on the successful feature film Apollo 13.12 With shelves straining from all this Apollo material, what could possibly be left to say? To begin with, histories of the Apollo program are nearly all project oriented— they begin at Apollo’s beginning and end at its end. Other than personal background in memoirs, little is said about Apollo’s connection to larger currents in the history of twentieth-century technology.

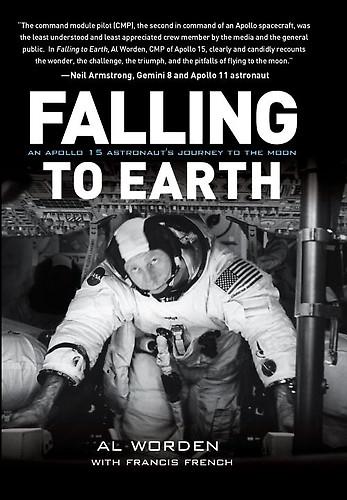

Falling to Earth

by

Al Worden

Published 26 Jul 2011

We were really hitting our stride and showing NASA’s full potential when it came to lunar exploration. After the dangers of Apollo 13, there would be one more of the simpler lunar landing missions: Apollo 14 would carry out the mission Apollo 13 failed to complete. Then we would take Apollo way beyond its original intentions. It was a strange irony, however. Right as we grew in confidence and potential, budget cuts were chopping the program out from underneath us. Our crew felt ready to take on the extra work of an enhanced mission. Not only did we have extra time to train because of the delay after Apollo 13, but we had already been training together for several years.

…

Not long after the fire, I was assigned back to Downey to resume work on the Block II spacecraft. This time, my job was to improve everything we could, based on the lessons of the fire. Jack Swigert, who would later fly on the Apollo 13 mission, joined me in this important duty. Because of his work improving the command module, Jack probably saved his own life years later when Apollo 13’s service module failed and he helped to bring the crippled spacecraft home. A lifelong bachelor, Jack had a party at his house every weekend and dated every woman in sight. He was a real skirt chaser and a playboy. He spent a lot of time in Miami, where Eastern Airlines had a flight attendant school.

…

But I was amused by the buzz in the papers and magazines, which appeared to be more excited about the single astronaut and his “spacey” apartment than I was. If I needed a reminder of the dangers of my job—and I didn’t—one came right after our formal announcement as the Apollo 15 prime crew. Just a month later, in April of 1970, Apollo 13 launched. It was the third manned lunar landing. That was the plan anyway. I had my own mission to train for now and wasn’t involved at all in Apollo 13. I was sitting on my spacey sofa in my apartment watching TV two days after the launch when Jules Bergman, the ABC channel’s space commentator, interrupted the show with a news flash. I listened to his hurried report with alarm.

Think Like a Rocket Scientist: Simple Strategies You Can Use to Make Giant Leaps in Work and Life

by

Ozan Varol

Published 13 Apr 2020

He continued: “I had practiced it and trained for it so many times, I almost dared her, I almost dared her to quit on me.” After repeated practice, the astronaut and the spacecraft had fused into one. “Every breath she breathed,” Cernan recalled, “I breathed with her.”30 When the oxygen tank exploded on the Apollo 13 mission—literally taking the astronauts’ breath away—their training kicked in. The movie Apollo 13 displays a chaotic environment on the spacecraft and in mission control, with rocket scientists and astronauts scrambling to improvise solutions. Because the service module was damaged from the explosion, they had to figure out how to use the lunar module—intended only to shuttle two astronauts to the lunar surface—as a lifeboat for returning all three astronauts back to Earth.

…

Tens of millions break out in laughter as Leslie dumps Leonard because he prefers string theory over loop quantum gravity. For three months, more than three million Americans picked Cosmos over The Bachelor each Sunday night, choosing dark matter and black holes over the drama of a rose ceremony.13 Movies about rocket science—from Apollo 13 to The Martian, from Interstellar to Hidden Figures—consistently top box-office charts and collect countless golden statues. Although we glamorize rocket scientists, there’s an enormous mismatch between what they have figured out and what the rest of the world does. Critical thinking and creativity don’t come naturally to us.

…

A High-Stakes Game of Peekaboo Imagine sitting on top of a rocket, with the explosive power of a small nuclear bomb, not knowing whether it will work. Astronauts call that Tuesday. The Atlas rocket, which launched the Mercury astronauts into space, was feared as too flimsy. “The Atlas boosters were blowing up every other day down at Cape Canaveral,” recalls former astronaut Jim Lovell, who would later become the commander of the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission. “It looked like a very quick way to have a short career. So I took the job.”64 Speaking of the Atlas rocket, Wernher von Braun—a former Nazi who later became a chief architect of the US space program—remarked, “John Glenn is going to ride on that contraption? He should be getting a medal just for sitting on top of it before he takes off.”65 We knew so little about the impact of spaceflight on the human condition that Glenn was instructed to read an eye chart every twenty minutes for fear that weightlessness would distort his vision.

Moondust: In Search of the Men Who Fell to Earth

by

Andrew Smith

Published 3 Apr 2006

“Oh, nooo,” he assures me; “they just came round to get the feel of what an astronaut is really like.” So we’ll take that as a “yes,” especially once we know that Ron Howard and Bill Paxton also came over when they were making Apollo 13, and that at the film’s Hollywood premiere a stream of people came and told Bean how puzzled they’d been to find that Paxton’s portrayal of the Apollo 13 Lunar Module pilot, Fred Haise, reminded them so much of him. I watch it again and they’re absolutely right. The museum district comes on like a pleasant afterthought to the city, manicured green and – with no reason for anyone to go there other than culture – quiet.

…