Apple II

description: an early personal computer released by Apple in 1977, which became one of the first highly successful mass-produced microcomputers.

99 results

Valley of Genius: The Uncensored History of Silicon Valley (As Told by the Hackers, Founders, and Freaks Who Made It Boom)

by

Adam Fisher

Published 9 Jul 2018

Andy Hertzfeld: It was an incredible advance costwise, because to get a computer monitor to do that would have cost as much as the rest of the computer pretty much. But Woz designed it to use a standard color television set, which could be gotten very cheaply. Steve Wozniak: It made it possible for a little one-dollar chip to generate color instead of a thousand-dollar color-generation board. Lee Felsenstein: Nobody had to pay for that additional hardware to do all that vector generation and phasing and so forth. Andy Hertzfeld: It was the single cleverest thing in the Apple II. That was one of the first revolutions. Steve Wozniak: And then I thought, I wonder if I can write a game that’s playable with my slow BASIC? Dan Kottke: A video game has to move fast.

…

And the Apple II was literally full of stuff like that, where by just using tiny little bits of resources it could do amazing stuff. In fact, just looking at the Apple II design gave you the feeling that anything was possible, if you were just clever enough. That’s what the main lesson of the Apple II is: that it had infinite horizons. Steve Wozniak: So I programmed Breakout, and in half an hour I had tried a hundred variations that would have taken me ten years in hardware if I could’ve even done it. So I called Steve Jobs over to my apartment, and we sat down on the floor next to the cable snaking into my TV that had the back off of it so I could get the wires inside. And I showed him how I could change the colors of things and change the shape of the paddle and change the speed of the balls.

…

If you can do this with this machine, imagine what could you do on a more serious machine—like the Alto or the machines that were coming. Chuck Thacker: VisiCalc was a thing that was useful to businesspeople, and a lot of them. And did increase the productivity of people who did who use that kind of tool—enormously. Butler Lampson: It was a success of the Apple II and VisiCalc that created the whole personal computer industry, really. Steve Wozniak: The Apple II was the only one of those computers, the three of them that existed, that had enough memory to run VisiCalc. So they had to write it for this computer only. Everybody else had to go back to the drawing board and make computers that could add floppy disks and more memory.

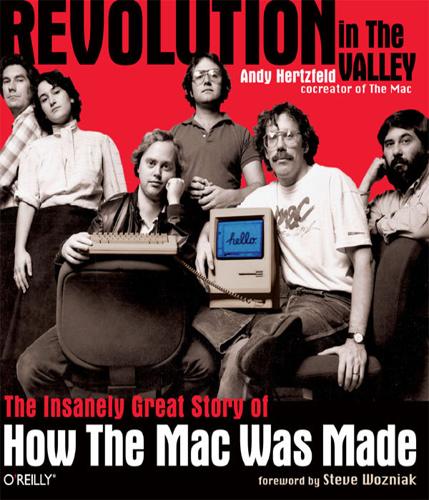

Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made

by

Andy Hertzfeld

Published 19 Nov 2011

We’ll See About That November 1979 Burrell proves his mettle with the 80K language card Burrell Smith was a 23-year-old, self-taught engineer, without a college degree, who was drawn to Apple by the sheer elegance of the Apple II design. Apple hired him in February 1979 as employee #282, a lowly service technician responsible for fixing broken Apple IIs that were returned by customers. As he debugged broken logic boards, sometimes more than a dozen in a single day, he developed a profound respect and empathy for Steve Wozniak’s unique and creative design techniques. Meanwhile, the Lisa software team was writing their first code in Pascal running on Apple IIs because the Lisa hardware wasn’t ready yet. They had been at it for almost a year and had written more code than would fit in the 64K bytes of memory in a standard Apple II.

…

As I taught myself 6502 assembly language from the monitor listing that came with the machine, it became clear to me this was no ordinary product: the coding style was crazy, whimsical, and outrageous, just like every other part of the design—especially the hi-res color graphic screen. It was clearly the work of a passionate artist. Eventually, I became so obsessed with the Apple II that I had to go to work at the place that created it. I abandoned graduate school and started work as a systems programmer at Apple in August 1979. Even though the Apple II was overflowing with both technical and marketing genius, the best thing about it was the spirit of its creation. It was not conceived or designed as a commercial product in the usual sense. Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak was just trying to make a great computer for himself and impress his friends at the Homebrew Computer Club.

…

Making the transition from an ardent Apple II hobbyist to an Apple employee was like ascending Mount Olympus, walking among the gods, working alongside my heroes. The early team at Apple was full of amazing individuals, people like Steve Wozniak, Rod Holt, and Mike Markkula. It was a privilege to get to know them and learn the company mythology firsthand. Apple’s other co-founder, Steve Jobs, had no shortage of vision or ambition. Flush with the rapidly growing success of the Apple II, Apple initiated two new projects in the fall of 1978 (codenamed Sara and Lisa), which were aimed beyond the hobbyist market. Sara was a souped-up successor to the Apple II, using the same microprocessor with an 80-column display and additional memory, intended for small businesses.

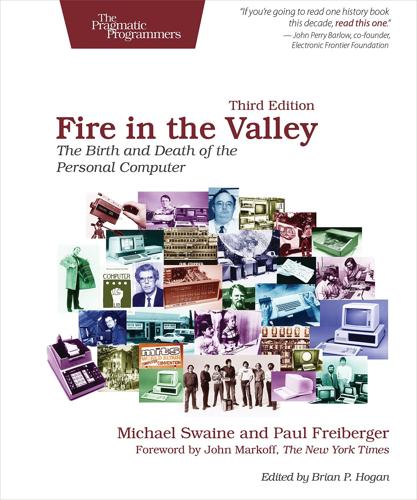

Fire in the Valley: The Birth and Death of the Personal Computer

by

Michael Swaine

and

Paul Freiberger

Published 19 Oct 2014

He told Woz and Jobs that neither of them had the experience to run a company and hired a president: Michael Scott, nicknamed Scotty, a seasoned executive who had worked for him at Fairchild. Designing the Apple II By the fall of 1976, Woz had already made progress on the design of his new computer. The Apple II would embody all the engineering savvy he could bring to it. It would be the embodiment of Steve Wozniak’s dream computer, one he would like to own himself. He had made it considerably faster than the Apple I. There was a clever trick he wanted to try that would give the machine a color display, too.

…

The Debut The young company faced a more modest challenge than tackling the company that had defined computer for generations: they had to finish the Apple II design in time for Jim Warren’s first West Coast Computer Faire in April and get it ready for production shortly thereafter. Markkula was already signing up distributors nationwide, many of whom were eager to work with a company that would give them greater freedom than microcomputer manufacturer MITS had, as well as provide a product that actually did something. * * * Figure 62. Steve Wozniak Woz scrambles for a phone in one of Apple’s early offices. (Courtesy of Margaret Kern Wozniak) Steve Wozniak is justly credited with the technical design of the Apple I and Apple II.

…

When the programmer returned, it took him more than a few minutes to figure out why his Apple was squeaking. Meanwhile, without the singular vision of a Steve Wozniak, the Apple III project was floundering. Delays in the Apple III were soon causing concern in the marketing department. The young company was beginning to feel growing pains at last. When Apple was formed, the Apple II was already near completion. The Apple III was the first computer that Apple—as a company—had designed and built from scratch. The Apple III was also the first Apple not conceived by Steve Wozniak in pursuit of his personal dream machine. Instead the Apple III was a bit of a hodgepodge, pasted together by many hands and designed by committee.

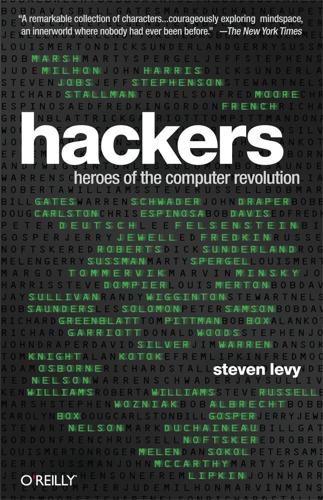

Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution - 25th Anniversary Edition

by

Steven Levy

Published 18 May 2010

While the selling was going on, Steve Wozniak began working on an expanded design of the board, something that would impress his Homebrew peers even more. Steve Jobs had plans to sell many computers based on this new design, and he started getting financing, support, and professional help for the day the product would be ready. The new version of Steve Wozniak’s computer would be called the Apple II, and at the time no one suspected that it would become the most important computer in history. • • • • • • • • It was the fertile atmosphere of Homebrew that guided Steve Wozniak through the incubation of the Apple II. The exchange of information, the access to esoteric technical hints, the swirling creative energy, and the chance to blow everybody’s mind with a well-hacked design or program . . . these were the incentives which only increased the intense desire Steve Wozniak already had: to build the kind of computer he wanted to play with.

…

Who’s Who: The Wizards and Their Machines Bob Albrecht. Founder of People’s Computer Company who took visceral pleasure in exposing youngsters to computers. Altair 8800. The pioneering microcomputer that galvanized hardware hackers. Building this kit made you learn hacking. Then you tried to figure out what to do with it. Apple II. Steve Wozniak’s friendly, flaky, good-looking computer, wildly successful and the spark and soul of a thriving industry. Atari 800. This home computer gave great graphics to game hackers like John Harris, though the company that made it was loath to tell you how it worked. Bob and Carolyn Box. World-record-holding gold prospectors turned software stars, working for Sierra On-Line.

…

Filled a small room, but in the late fifties, this $3 million machine was world’s first personal computer—for the community of MIT hackers that formed around it. Jim Warren. Portly purveyor of “techno-gossip” at Homebrew, he was first editor of hippie-styled Dr. Dobbs Journal, later started the lucrative Computer Faire. Randy Wigginton. Fifteen-year-old member of Steve Wozniak’s kiddie corps, he helped Woz trundle the Apple II to Homebrew. Still in high school when he became Apple’s first software employee. Ken Williams. Arrogant and brilliant young programmer who saw the writing on the CRT and started Sierra On-Line to make a killing and improve society by selling games for the Apple computer.

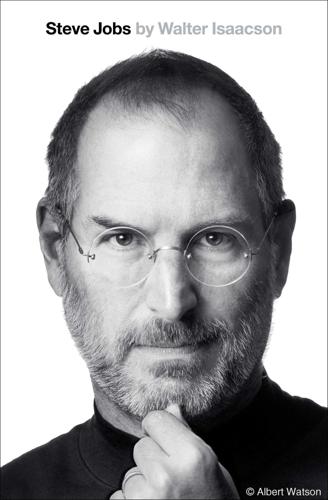

Steve Jobs

by

Walter Isaacson

Published 23 Oct 2011

But the biggest news that month was the departure from Apple, yet again, of its cofounder, Steve Wozniak. Wozniak was then quietly working as a midlevel engineer in the Apple II division, serving as a humble mascot of the roots of the company and staying as far away from management and corporate politics as he could. He felt, with justification, that Jobs was not appreciative of the Apple II, which remained the cash cow of the company and accounted for 70% of its sales at Christmas 1984. “People in the Apple II group were being treated as very unimportant by the rest of the company,” he later said. “This was despite the fact that the Apple II was by far the largest-selling product in our company for ages, and would be for years to come.”

…

Steve Jobs, address to the Aspen Design Conference, June 15, 1983, tape in Aspen Institute archives; Apple Computer Partnership Agreement, County of Santa Clara, Apr. 1, 1976, and Amendment to Agreement, Apr. 12, 1976; Bruce Newman, “Apple’s Lost Founder,” San Jose Mercury News, June 2, 2010; Wozniak, 86, 176–177; Moritz, 149–151; Freiberger and Swaine, 212–213; Ashlee Vance, “A Haven for Spare Parts Lives on in Silicon Valley,” New York Times, Feb. 4, 2009; Paul Terrell interview, Aug. 1, 2008, mac-history.net. Garage Band: Interviews with Steve Wozniak, Elizabeth Holmes, Daniel Kottke, Steve Jobs. Wozniak, 179–189; Moritz, 152–163; Young, 95–111; R. S. Jones, “Comparing Apples and Oranges,” Interface, July 1976. CHAPTER 6: THE APPLE II An Integrated Package: Interviews with Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Al Alcorn, Ron Wayne. Wozniak, 165, 190–195; Young, 126; Moritz, 169–170, 194–197; Malone, v, 103. Mike Markkula: Interviews with Regis McKenna, Don Valentine, Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Mike Markkula, Arthur Rock. Nolan Bushnell, keynote address at the ScrewAttack Gaming Convention, Dallas, July 5, 2009; Steve Jobs, talk at the International Design Conference at Aspen, June 15, 1983; Mike Markkula, “The Apple Marketing Philosophy” (courtesy of Mike Markkula), Dec. 1979; Wozniak, 196–199.

…

He had never been, and would never be, adept at containing his emotions. He told Steve Wozniak that he was willing to call off the partnership. “If we’re not fifty-fifty,” he said to his friend, “you can have the whole thing.” Wozniak, however, understood better than his father the symbiosis they had. If it had not been for Jobs, he might still be handing out schematics of his boards for free at the back of Homebrew meetings. It was Jobs who had turned his ingenious designs into a budding business, just as he had with the Blue Box. He agreed they should remain partners. It was a smart call. To make the Apple II successful required more than just Wozniak’s awesome circuit design.

Insanely Great: The Life and Times of Macintosh, the Computer That Changed Everything

by

Steven Levy

Published 2 Feb 1994

The first computers discussed at the Homebrew Computer Club, Steve Wozniak's home base, had 4K memory, the rough equivalent of four pages of text. When the Apple II shipped with 48K memory, it was deemed an enormous expanse. Later, Apple II users would buy circuit boards to add 16K more, and then they really felt they were humming. So it is not surprising that Jobs felt 128K sufficient. But there were two errors to his thinking. First, since Macintosh was a bit-mapped machine, considerably more memory was required than with the raster-based Apple II or IBM-PC. When one of these displayed a word, it used a shortcut-there was a single one-byte computer code for each letter, and that chunk of code threw the letter on the screen.

…

It filled several low-slung office buildings in Cupertino, and had hundreds of employees. Though the Apple II was wonderful for its time, Apple's leaders realized that the company needed new products to remain competitive. They began work on-the Apple III, a machine roughly as powerful as IBM's personal computer would be. But Steve Jobs had an idea for something even more special-Lisa, a computer that would leapfrog Apple's technology, surpassing not only the Apple II, but Apple III as well. This jump would also vault Apple a generation or so past anything that its competitors were preparing. Begun when Steve Wozniak, at Steve Jobs's request, sketched its architecture on a napkin, Lisa had, in less than a year, evolved to a computer based on the powerful Motorola 68000 microprocessor chip, and was engineered to handle more complicated applications, even running several at the same time, a trick called "multitasking."

…

The stunning visuals produced by Atkinson's work allowed people to see the brain from previously unimagined vistas. Atkinson had experienced a conversion experience when he came across an Apple II in 1977. He easily saw past its limitations (it was much less powerful than the machines he worked with at school), instead appreciating the virtuosity of Steve Wozniak's digital design. He went to work for Apple in 1978-employee number 51-writing applications that would help sell the Apple II. But with Lisa, Atkinson faced his biggest challenge. His ninety-minute exposure to Smalltalk had been somewhat deceiving. While the computer in some ways seemed to have completely solved the challenge of allowing an unschooled worker easy access to the information inside the computer-the furniture of cyberspace-when Atkinson sat down and tried to duplicate the task, he realized that there were gaps as yet unfilled.

Exploding the Phone: The Untold Story of the Teenagers and Outlaws Who Hacked Ma Bell

by

Phil Lapsley

Published 5 Feb 2013

He had spent a total of three months on the inside, where he slopped pigs at the prison’s piggery and tended the prison grounds in a landscaping job. While there, Draper claims, he taught the art of phone phreaking to dozens of other inmates. Draper soon went to work for his friend Steve Wozniak at Apple Computer, designing an innovative product called the Charley Board. Charley was an add-in circuit board for the Apple II that connected the computer to the telephone line. With Charley and a few simple programs you could make your Apple II do all sorts of telephonic tricks. Not only could it dial telephone numbers and send touch tones down the line, it could even listen to the calls it placed and recognize basic telephone signals as the call progressed, signals such as a dial tone or busy signal or a ringing signal.

…

Riches, or promises of riches, or maybe just a fun job that might pay the bills beckoned. In 1976 former phone phreaks Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak were selling Apple I computers to their fellow hobbyists. “Jobs placed ads in hobbyist publications and they began selling Apples for the price of $666.66,” journalist Steven Levy wrote. “Anyone in Homebrew could take a look at the schematics for the design, Woz’s BASIC was given away free with the purchase of a piece of equipment that connected the computer to a cassette recorder.” The fully assembled and tested Apple II followed later that year. By 1977 microcomputers had begun to enter the mainstream.

…

Excerpt from IWOZ: COMPUTER GEEK TO CULT ICON: HOW I INVENTED THE PERSONAL COMPUTER, COFOUNDED APPLE, AND HAD FUN DOING IT by Steve Wozniak and Gina Smith. Copyright © 2006 by Steve Wozniak and Gina Smith. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9375-9 Grove Press an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc. 841 Broadway New York, NY 10003 Distributed by Publishers Group West www.groveatlantic.com 13 14 15 16 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To the men and women of the Bell System, and especially to the members of the technical staff of Bell Laboratories, without whom none of this would have been possible CONTENTS FOREWORD BY STEVE WOZNIAK A NOTE ON NAMES AND TENSES CHAPTER 1 FINE ARTS 13 CHAPTER 2 BIRTH OF A PLAYGROUND CHAPTER 3 CAT AND CANARY CHAPTER 4 THE LARGEST MACHINE IN THE WORLD CHAPTER 5 BLUE BOX CHAPTER 6 “SOME PEOPLE COLLECT STAMPS” CHAPTER 7 HEADACHE CHAPTER 8 BLUE BOX BOOKIES CHAPTER 9 LITTLE JOJO LEARNS TO WHISTLE CHAPTER 10 BILL ACKER LEARNS TO PLAY THE FLUTE CHAPTER 11 THE PHONE FREAKS OF AMERICA PHOTO INSERT CHAPTER 12 THE LAW OF UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES CHAPTER 13 COUNTERCULTURE CHAPTER 14 BUSTED CHAPTER 15 PRANKS CHAPTER 16 THE STORY OF A WAR CHAPTER 17 A LITTLE BIT STUPID CHAPTER 18 SNITCH CHAPTER 19 CRUNCHED CHAPTER 20 TWILIGHT CHAPTER 21 NIGHTFALL EPILOGUE SOURCES AND NOTES ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INDEX THE PLAYGROUND Phone phreak (n.) 1.

Founders at Work: Stories of Startups' Early Days

by

Jessica Livingston

Published 14 Aug 2008

We put out manuals that had just hundreds of pages of listings of code, descriptions of circuits, examples of boards that you would plug in—so that Steve Wozniak 51 anyone could look at this and say, “Now I know how I would do my own.” They could type in the programs on their own Apple II and then see “that’s how that works” instantly, and know how to write their own programs. Running cards was the most important thing. All these companies started up making cards that you could plug into your Apple II and write a little software (mostly games at first) on cassette tapes. You’d go to the store and they’d just have all this stuff that you could buy to enhance the Apple II. So one of our big keys to success was that we were very open.

…

He said, “Alright, you’ll be productive only in the afternoon. Take the morning off.” Little did he know that I was actually up all night writing a business plan, not partying. C H A P T 3 E R Steve Wozniak Cofounder, Apple Computer If any one person can be said to have set off the personal computer revolution, it might be Steve Wozniak. He designed the machine that crystallized what a desktop computer was: the Apple II. Wozniak and Steve Jobs founded Apple Computer in 1976. Between Wozniak’s technical ability and Jobs’s mesmerizing energy, they were a powerful team. Woz first showed off his home-built computer, the Apple I, at Silicon Valley’s Homebrew Computer Club in 1976.

…

Mike figured out that we were going to need some cash, we were going to be so fast growing. And when you are fast growing, you need more cash right away. So we did have a venture deal in place from well before we shipped an Apple II. And sometime after we were shipping the Apple IIs, we got, I think, $800,000 or $300,000—some large amount—from one venture capital place. Steve Wozniak 57 Livingston: On the East Coast? Wozniak: I believe that’s where we arranged it. Mike Markkula had worked with this guy Hank Smith at Intel, so that’s how they knew each other. And I think Don Valentine actually put some money in, but then it came to a point where he wanted to make some good money and buy some stock off Steve Jobs for like $5.50 before we went public. $5.50 a share, and Steve thought it was too low.

The Innovators: How a Group of Inventors, Hackers, Geniuses and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution

by

Walter Isaacson

Published 6 Oct 2014

To listen to Dompier’s Altair play “Fool on the Hill,” go to http://startup.nmnaturalhistory.org/gallery/story.php?ii=46. 32. After they became successful, Gates and Allen donated a new science building to Lakeside and named its auditorium after Kent Evans. 33. Steve Wozniak’s unwillingness to tackle this tedious task when he wrote BASIC for the Apple II would later force Apple to have to license BASIC from Allen and Gates. 34. Reading a draft version of this book online, Steve Wozniak said that Dan Sokol made only eight copies, because they were hard and time-consuming to make. But John Markoff, who reported this incident in What the Dormouse Said, shared with me (and Woz and Felsenstein) the transcript of his interview with Dan Sokol, who said he used a PDP-11 with a high-speed tape reader and punch.

…

Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn complete TCP/IP protocols for the Internet. 1974 Intel 8080 comes out. 1975 Altair personal computer from MITS appears. Paul Allen and Bill Gates write BASIC for Altair, form Microsoft. First meeting of Homebrew Computer Club. Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak launch the Apple I. 1977 The Apple II is released. 1978 First Internet Bulletin Board System. 1979 Usenet newsgroups invented. Jobs visits Xerox PARC. 1980 IBM commissions Microsoft to develop an operating system for PC. 1981 Hayes modem marketed to home users. 1983 Microsoft announces Windows.

…

Author’s interview with Lee Felsenstein. 81. Bill Gates interview, Playboy, July 1994. 82. This section draws from my Steve Jobs (Simon & Schuster, 2011), which was based on interviews with Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Nolan Bushnell, Al Alcorn, and others. The Jobs biography includes a bibliography and source notes. For this book, I reinterviewed Bushnell, Alcorn, and Wozniak. This section also draws on Steve Wozniak, iWoz (Norton, 1984); Steve Wozniak, “Homebrew and How the Apple Came to Be,” http://www.atariarchives.org/deli/homebrew_and_how_the_apple.php. 83. When I posted an early draft of parts of this book for crowdsourced comments and corrections on Medium, Dan Bricklin offered useful suggestions.

Troublemakers: Silicon Valley's Coming of Age

by

Leslie Berlin

Published 7 Nov 2017

Harriet Stix, “A UC Berkeley Degree Is Now the Apple of Steve Wozniak’s Eye,” Los Angeles Times, May 14, 1986. 18. Marilyn Chase, “Technical Flaws Plague Apple’s New Computer,” Wall Street Journal, April 15, 1981. Apple III prices ranged from $4,300 to nearly $8,000, compared to the Apple II systems at about half the cost. 19. Apple fixed the problems and brought the Apple III back in late 1981—“Let me re-introduce myself,” one advertisement began—but not much software was written for the machine, and it was not anywhere near as popular as the Apple II. (Sales were around 1,000 per month versus the Apple II’s 15,000.) By one estimate (Brent Schlender and Rick Tetzeli, Becoming Steve Jobs: The Evolution of a Reckless Upstart into a Visionary Leader [New York: Crown Business, 2015]: 72), before the Apple III was discontinued in 1984, only 120,000 had been sold.

…

The only people who seemed obvious choices for their jobs were Steve Wozniak, who ran engineering, and Mike Scott, in his capacity as manufacturing head. But it worked. Occasionally lost in the stories of Jobs’s bare feet and Wozniak’s practical joking is the reality of how hard and effectively the young men and their older semiconductor colleagues worked together. The birth of Apple’s floppy disk drive almost exactly a year after the company incorporated, and six months after it began shipping Apple IIs, offers a fine illustration. The Apple II was selling well, but Markkula was convinced it would never make the leap to a broad consumer market unless there were some way to make it load software faster.

…

The first outside backer of Electronic Arts was Don Valentine, the venture capitalist who had funded Atari and introduced Mike Markkula to Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. Ben Rosen, the optimistic technology analyst, was another early backer.IV Electronic Arts had its first big hit in October 1983 with Doctor J and Larry Bird Go One-on-One, a basketball game featuring two of the sport’s biggest stars. The title was one of the most popular games for the Apple II and an early indicator of the enormous market for licensed sports video games. (Electronic Arts would exploit this market with great success five years later with the release of John Madden Football.III) But in the wake of the 1983 crash, even Electronic Arts, which made games for computers, not dedicated consoles or arcades, had to retrench.

Commodore: A Company on the Edge

by

Brian Bagnall

Published 13 Sep 2005

“The PET and the TRS-80 both came with their own monitors, so they were a more appropriate solution for most people than the Apple II was,” says Yannes. The original design by Steve Wozniak also had several flaws. “Right after the Apple II came out, Electronic Engineering Times wrote a story about the three major design flaws that Woz made on the Apple II,” says Peddle. “He didn’t understand the ways the [6502] chipset worked and some other electronics stuff.” In response to these problems, Apple hired an engineer to redesign Wozniak’s motherboard. “There was a guy who was hired at Apple to redesign the Apple II and make it real engineering without offending Woz,” explains Peddle.

…

In 1981, the nine-year-old received a VIC-20 from his grandfather and used it to learn BASIC programming. He was taking the first steps which eventually led him to create a revolution with Linux. [7] Time magazine, “The Hottest-Selling Hardware” (January 3, 1983), p. 37. [8] Steve Wozniak has attempted to claim the Apple II was the first to a million. On BBC World’s Most Powerful, aired December 2003, Wozniak claimed, “Sales shot sky high. Apple was the first company to sell a hundred thousand computers—a million computers.” CHAPTER 29 Selling the Revolution 1982 With the engineering job complete (or at least good enough), Charlie Winterble’s team reluctantly stepped away from the Commodore 64.

…

“They would go around the suite and they would see the development systems, and they would find out how to log onto the timesharing systems so they could develop code,” says Peddle. “Then they would wander away.” If all went well, the engineers and hobbyists would go out into the world and design products with the 6502. Waiting in line outside the MacArthur Suite was Steve Wozniak, who thought he might be able to use the chip for a homebrew computer project. “Woz and Steve Jobs bought their first 6502 and they used it in the Apple I,” says Bill Seiler. Peddle’s documentation undoubtedly influenced Wozniak’s design. The 6502 did not immediately improve MOS Technology’s finances, but it had a major impact on the computer industry.

Start With Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action

by

Simon Sinek

Published 29 Oct 2009

They hung out with hippie types who shared their beliefs, but they saw a different way to change the world that didn’t require protesting or engaging in anything illegal. Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs came of age in this time. Not only was the revolutionary spirit running high in Northern California, but it was also the time and place of the computer revolution. And in this technology they saw the opportunity to start their own revolution. “The Apple gave an individual the power to do the same things as any company,” Wozniak recounts. “For the first time ever, one person could take on a corporation simply because they had the ability to use the technology.” Wozniak engineered the Apple I and later the Apple II to be simple enough for people to harness the power of the technology.

…

Disney and the Creation of an Entertainment Empire. New York: Disney Editions, 1998. 142 Herb Kelleher was able to personify and preach the cause of freedom: Kevin Freiberg and Jackie Freiberg, Nuts! Southwest Airlines’ Crazy Recipe for Business and Personal Success. New York: Broadway, 1998. 142 Steve Wozniak is the engineer who made the Apple work: Steve Wozniak, personal interview, November 2008. 143 Bill Gates and Paul Allen went to high school together in Seattle: Randy Alfred, “April 4, 1975: Bill Gates, Paul Allen Form a Little Partnership,” Wired, April 4, 1975, http://www.wired.com/science/discoveries/news/2008/04/dayintech_0404. 145 Oprah Winfrey once gave away a free car: Ann Oldenburg, “7M car giveaway stuns TV audience,” USA Today, September 13, 2004, http://www.usatoday.com/life/people/2004-09-13-oprah-cars_x.htm. 150 the Education for Employment Foundation: http://www.efefoundation.org/homepage.html; Lisa Takeuchi Cullen, “Gainful Employment,” Time, September 20, 2007, http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1663851,00.html; Ron Bruder, personal interview, February 2009.

…

But it wasn’t until 1976, nearly three years after the end of America’s military involvement in the Vietnam conflict, that a different revolution ignited. They aimed to make an impact, a very big impact, even challenge the way people perceived how the world worked. But these young revolutionaries did not throw stones or take up arms against an authoritarian regime. Instead, they decided to beat the system at its own game. For Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs, the cofounders of Apple Computer, the battlefield was business and the weapon of choice was the personal computer. The personal computer revolution was beginning to brew when Wozniak built the Apple I. Just starting to gain attention, the technology was primarily seen as a tool for business.

The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires

by

Tim Wu

Published 2 Nov 2010

It made it possible to write and sell one’s programs directly, creating what we now call the “software” industry. In 2006, I briefly met with Steve Wozniak on the campus of Columbia University. “There’s a question I’ve always wanted to ask you,” I said. “What happened with the Mac? You could open up the Apple II, and there were slots and so on, and anyone could write for it. The Mac was way more closed. What happened?” “Oh,” said Wozniak. “That was Steve. He wanted it that way. The Apple II was my machine, and the Mac was his.” Apple’s origins were pure Steve Wozniak, but as everyone knows, it was the other founder, Steve Jobs, whose ideas made Apple what it is today.

…

For while founders do set the culture of a firm, they cannot dictate it in perpetuity; as Wozniak withdrew from the operation, Apple became more and more concerned with, as it were, the aesthetics of radicalism than with its substance. Steve Wozniak is not the household name that Steve Jobs is, but his importance to communications and culture in the postwar period merits a closer look. While Apple’s wasn’t the only personal computer invented in the 1970s, it was the most influential. For the Apple II took personal computing, an obscure pursuit of the hobbyist, and made it into a nationwide phenomenon, one that would ultimately transform not just computing, but communications, culture, entertainment, business—in short, the whole productive part of American life.

…

Theirs was to be a union that could move mountains—or at least break down the old barriers and create a perfect new world.2 The two moguls plotting the future of the Internet had something else in common: neither was what you might call a natural computer geek, in the manner of Bill Gates or Steve Jobs. Entrepreneurs like Apple’s Steve Wozniak got started by programming and soldering; Case was an assistant brand manager at Procter & Gamble in Kansas. He might have languished somewhere in upper middle management had he not resolved to grab the ring. Case took a job at a risky computer networking firm named the Control Video Corporation that had already failed twice.

Becoming Steve Jobs: The Evolution of a Reckless Upstart Into a Visionary Leader

by

Brent Schlender

and

Rick Tetzeli

Published 24 Mar 2015

I was thirty-two years old; Jobs was thirty-one and already a global celebrity, hailed, along with Bill Gates, for having invented the personal computer industry. Long before Internet mania started churning out wunderkinds of the week, Jobs was technology’s original superstar, the real deal with an astounding, substantial record. The circuit boards he and Steve Wozniak had assembled in a garage in Los Altos had spawned a billion-dollar company. The personal computer seemed to have unlimited potential, and as the cofounder of Apple Computer, Steve Jobs had been the face of all those possibilities. But then, in September of 1985, he had resigned under pressure, shortly after telling the company’s board of directors that he was courting some key Apple employees to join him in a new venture to build computer “workstations.”

…

Rock loved order, he loved processes, he believed that tech companies grew in certain ways according to certain rules, and he subscribed to these beliefs because he’d seen them work before, most notably at Intel, the great Santa Clara chipmaker that he had backed early on. Rock was perhaps the most notable tech investor of his time, but he in fact had been reluctant to back Apple at first, largely because he’d found Steve and his partner Steve Wozniak unpalatable. He didn’t see Apple the way Jobs saw it—as an extraordinary company that would humanize computing and do so with a defiantly unhierarchical organization. Rock simply viewed it as another investment. Steve found board meetings with Rock enervating, not invigorating; he had looked forward to a long, fast drive to Marin with the top down to get rid of the stale stench of seemingly endless discussion.

…

“I was inventing new stuff. I figured I’d just stay on here. I’d had a pretty miserable experience at Disney.” He told Schneider that there was only one way that he’d consider working with Disney—the studio would have to make a movie with Pixar. The Evolution of a CEO Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak in 1979. The two had founded Apple four years earlier, and the company was growing like crazy. But the best years of their collaboration were already over. Ted Thai/Polaris A 1979 gathering of the Seva Foundation, which Steve backed with a $5,000 donation. His close friend Larry Brilliant is at the center with his baby boy, Joseph; Brilliant’s wife, Girija, is to the right, arms crossed and leaning back.

The Everything Blueprint: The Microchip Design That Changed the World

by

James Ashton

Published 11 May 2023

v=KrTmvqwpZF8 8 Brian Merchant, The One Device, Little, Brown, 2017,p. 155. 9 https://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/access/text/2012/06/102746190-05-01-acc.pdf 10 https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/the_legacy_of_bbc_micro.pdf 11 https://www.nytimes.com/1962/11/03/archives/pocket-computer-may-replace-shopping-list-inventor-says-device.html 12 https://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/access/text/2014/08/102739939-05-01-acc.pdf 13 https://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/access/text/2014/08/102739939-05-01-acc.pdf 14 https://web.archive.org/web/20120721114927/http://www.variantpress.com/view.php?content=ch001 15 https://web.archive.org/web/20120721114927/http://www.variantpress.com/view.php?content=ch001 16 Steve Wozniak, iWoz, Headline, 2007 17 Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs, Simon & Schuster, 2011, p. 58. 18 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apple_II#/media/File:Apple_II_advertisement_Dec_1977_page_2.jpg 19 Berlin, The Man Behind the Microchip, p. 251. 20 Isaacson, Steve Jobs, p. 84. 21 https://archive.computerhistory.org/resources/access/text/2014/08/102746675-05-01-acc.pdf 22 https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/the_legacy_of_bbc_micro.pdf 23 http://www.naec.org.uk/organisations/bbc-computer-literacy-project/towards-computer-literacy-the-bbc-computer-literacy-project-1979-1983 24 https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/104609 25 https://www.theregister.com/2011/11/30/bbc_micro_model_b_30th_anniversary/?

…

He drafted in his wife Shirley to greet engineers and take their money as they delved their hands into a glass jar of chips. One of the people waiting in line was a young computer designer called Steve Wozniak, whose Apple I machine was released the following year featuring the 6502. The Apple Seed When Steve Jobs saw what his best friend had come up with, he was convinced he was on to something. Jobs and Steve Wozniak had met in 1971, united by pranks and electronics even though they were four school years apart. The pair were polar opposites: Jobs, charismatic and brattish, occasionally dabbling in Eastern religions; Wozniak, the shy son of a rocket scientist at the aerospace manufacturer Lockheed.

…

‘And the people he wanted to promote were usually bozos.’36 After Jobs’ resignation in September 1985, Sculley steered a recovery in Apple’s sales. Looking further out, in 1986 the company created an Advanced Technology Group (ATG) to hunt for and incubate cutting-edge ideas. Jobs the visionary was gone, as was a disillusioned Steve Wozniak. ATG looked and felt a lot like ‘AppleLabs’, the mooted development division Jobs could have run if he had opted to stay on, having been freed from managerial responsibility. Larry Tesler, recruited six years earlier in the ‘raid’ on Xerox and having earned a reputation internally as courageous yet cool under pressure, was elevated to vice president.

Inventors at Work: The Minds and Motivation Behind Modern Inventions

by

Brett Stern

Published 14 Oct 2012

Calvert: These are the things that an inventor really needs to learn and work out before taking that big step of sending a patent application to the USPTO—hopefully as the prelude to starting up their own business. 1 www.uspto.gov/inventors/independent/eye/201206/index.jsp 2 www.uiausa.org CHAPTER 23 Steve Wozniak Co-Founder Apple Computer A Silicon Valley icon and philanthropist for more than thirty years, Steve Wozniak helped shape the computing industry with his design of Apple’s first line of products, the Apple I and II, and influenced the popular Macintosh. In 1976, Wozniak and Steve Jobs founded Apple Computer Inc. with Wozniak’s Apple I personal computer. The following year he introduced his Apple II personal computer, featuring a central processing unit, a keyboard, color graphics, and a floppy disk drive. The Apple II was integral to launching the personal computer industry.

…

Curt Croley, Shane MacGregor, Graham Marshall, Mobile Devices Chapter 18. Matthew Scholz, Healthcare Products Chapter 19. Daria Mochly-Rosen, Drugs Chapter 20. Martin Keen, Footwear Chapter 21. Kevin Deppermann, Seed Genomes Chapter 22. John Calvert, Elizabeth Dougherty, USPTO Chapter 23. Steve Wozniak, Personal Computers Index About the Author Brett Stern is an industrial designer and inventor living in Portland, Oregon. He holds eight utility patents covering surgical instruments, medical implants, and robotic garmentmanufacturing systems. He holds trademarks in 34 countries on a line of snack foods that he created.

…

Nonetheless, millions of individuals still cherish the dream of inventing and building a better mousetrap, bringing it to market, and being richly rewarded for those efforts. Americans love their pantheon of garage inventors. Thomas Edison, the Wright Brothers, Alexander Graham Bell, Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard, and Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs are held up as culture heroes, celebrated for their entrepreneurial spirit no less than their inventive genius. This book is a collection of interviews conducted with individuals who have distinguished themselves in the invention space. Some of the inventors interviewed here have their Aha!

Ghost in the Wires: My Adventures as the World's Most Wanted Hacker

by

Kevin Mitnick

Published 14 Aug 2011

Me in my pre-hacking days, around age nine, when my hobby was performing magic tricks (Shelly Jaffe) Me at age twenty-one, with my mother in Stockton, California, 1984 With bride Bonnie Vitello at our wedding reception, June 1987 My hacking partner Lewis De Payne, around the time he and I first met Justin Petersen, aka Eric Heinz, 1992 (Virgil Kasperavicius) Justin Petersen aka Eric Heinz while working as an FBI informant trying to gather evidence against me, 1992 (Count Zero aka John Lester) The Soundex, or driver’s license image, that I obtained of Eric Heinz while he was tailing me The Kinko’s location in Studio City, California, that the DMV investigators chased me from on Christmas Eve, 1992 The cash register building housing the Denver law firm where I worked; in the foreground is the apartment building where I lived (Nick Arnott) In Denver while on the run, April 1993, age twenty-nine The apartment in Seattle where I was raided by the Secret Service and Seattle police, 1994 (Shellee Hale) Mug shot on the day of capture, February 15, 1995, Raleigh, North Carolina My prison ID card from Lompoc FCI, subject of international press after eBay yanked the item for violating “community standards,” vastly raising interest—and raising the value to $4,000 Demonstration by my supporters outside the Miramax offices in 1998 protesting the depiction of me in their feature film Takedown (Emmanuel Goldstein, 2600 magazine) Alex Kasperavicius posting a “Free Kevin” sticker at the Mobil gas station across the street from the Metropolitan Detention Center on my thirty-fifth birthday, August 6, 1998 (Emmanuel Goldstein, 2600 magazine) Holding up a bumper sticker from inside the Metropolitan Detention Center’s inmate law library, in Los Angeles, to a crowd of “Free Kevin” supporters outside, on my thirty-fifth birthday (Emmanuel Goldstein, 2600 magazine) In Lompoc Federal Correctional Institution visiting room, 1999, age thirty-six The day I was released from Lompoc Federal Correctional Institution, January 21, 2000, age thirty-six (Emmanuel Goldstein, 2600 magazine) Gift wrapping on the PowerBook G4 Steve Wozniak gave me in front of television cameras to celebrate the end of my supervised release, January 2003 (Alan Luckow) Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak, me, and Emmanuel Goldstein (founder of 2600 magazine) on the television show The Screen Savers, celebrating the end of my supervised release, making me a completely free man: January 20, 2003, age thirty-nine (Courtesy of G4 TV) Boys will be boys: me before cyberspace (Author’s personal collection) CONTENTS Front Cover Image Welcome Dedication Foreword by Steve Wozniak Prologue PART ONE: The Making of a Hacker 1 Rough Start 2 Just Visiting 3 Original Sin 4 Escape Artist 5 All Your Phone Lines Belong to Me 6 Will Hack for Love 7 Hitched in Haste 8 Lex Luthor 9 The Kevin Mitnick Discount Plan 10 Mystery Hacker PART TWO: Eric 11 Foul Play 12 You Can Never Hide 13 The Wiretapper 14 You Tap Me, I Tap You 15 “How the Fuck Did You Get That?”

…

He has lived a life as exciting and gripping as the best caper movies. Now you’ll be able to share all these stories that I have heard one by one, now and then through the years. In a way, I envy the experience of the journey you’re about to start, as you absorb the incredible, almost unbelievable tale of Kevin Mitnick’s life and exploits. —Steve Wozniak, cofounder, Apple, Inc. PROLOGUE Physical entry”: slipping into a building of your target company. It’s something I never like to do. Way too risky. Just writing about it makes me practically break out in a cold sweat. But there I was, lurking in the dark parking lot of a billion-dollar company on a warm evening in spring, watching for my opportunity.

…

And I appeared to have it, too. It was my first conscious example of social engineering. How did people see me at Monroe High School? My teachers would have said that I was always doing unexpected things. When the other kids were fixing televisions in TV repair shop, I was following in Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak’s footsteps and building a blue box that would allow me to manipulate the phone network and even make free phone calls. I always brought my handheld ham radio to school and talked on it during lunch and recess. But one fellow student changed the course of my life. Steven Shalita was an arrogant guy who fancied himself as an undercover cop—his car was covered with radio antennas.

Equal Is Unfair: America's Misguided Fight Against Income Inequality

by

Don Watkins

and

Yaron Brook

Published 28 Mar 2016

Quoted in Sean Rossman, “Apple’s ‘The Woz’ Talks Jobs, Entrepreneurship,” Tallahassee Democrat, November 6, 2014, http://www.tallahassee.com/story/news/local/2014/11/05/apples-woz-talks-jobs-entrepreneurship/18561425/ (accessed April 13, 2015). 11. Quoted in Alec Hogg, “Apple’s ‘Other’ Steve—Wozniak on Jobs, Starting a Business, Changing the World, and Staying Hungry, Staying Foolish,” BizNews.com, February 17, 2014, http://www.biznews.com/video/2014/02/17/apples-other-steve-wozniak-on-jobs-starting-a-business-changing-the-world/ (accessed April 13, 2015). 12. Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), p. 295. 13. Ibid., pp. 308, 318. 14. Ibid., p. 317. 15.

…

And it can be amazing for everyone, because it turns out that the way we improve our lives—ingenuity and effort—is not a fixed-sum game, where we battle over a static amount of wealth. We produce wealth, and there is no limit to how much wealth we can produce. Who Created the Modern World? In his autobiography, Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak, or Woz, as he’s usually called, describes how his dad, an engineer, would explain to the four-year-old Woz how electronics worked. “I remember sitting there and being so little, and thinking: ‘Wow, what a great, great world he’s living in,’” Woz recalls. “I mean, that’s all I thought: ‘Wow.’ For people who know how to do this stuff—how to take these little parts and make them work together to do something—well, these people must be the smartest people in the world. . . .

…

Whatever it is, you do productive work in exchange for money, which you use to buy the dizzying array of things that other people produce. But that’s only part of the story. Not all work is equally productive. Some of us create a little wealth. Some of us create a lot. A tiny handful, like Steve Wozniak, create so much that their names go down in the history books. Think of some of the things that make your life wonderful. Your cell phone, your computer, the Internet? You can thank Robert Noyce and Jack Kilby, who invented the integrated circuit. The car that took you to work? You can thank Henry Ford, who transformed the automobile from a curiosity of the rich into a mass-market product.

After Steve: How Apple Became a Trillion-Dollar Company and Lost Its Soul

by

Tripp Mickle

Published 2 May 2022

Working from his parents’ ranch home in Los Altos, California, he and his friend Steve Wozniak, a self-taught engineer, developed one of the first computers for the masses, a gray box with a keyboard and power supply that could display graphics. In 1977, their company became formally incorporated as Apple Computer Inc., a name inspired by Jobs’s favorite band, the Beatles, and their record label, Apple Records. Jobs’s brazen salesmanship of their computers was dismissed by some as all pitch, no substance, but the Apple II computer became one of the first commercially successful PCs, earning the company $117 million in annual sales before it went public in 1980.

…

COOK LANDED AT IBM at the dawn of the PC age. Working from a California garage, his future boss, Steve Jobs, together with Steve Wozniak, had popularized the personal computer. Its widespread appeal had inspired the world’s technology heavyweight, IBM, to broaden its business line from the colossal mainframe machines that businesses and universities used to the computers people were putting into their homes. With a mandate from on high, two IBM managers, Philip “Don” Estridge and William Lowe, led the development of an Apple II rival that buyers could configure as they wished with the software and the disk drive of their choosing.

…

Their critical eyes fueled an unspoken competition, colleagues said. Each wanted to beat the other in catching minor flaws that would make an Apple product fall short of the greatness to which they both aspired. Jobs was skilled at finding creative partners. Apple had sprouted out of his partnership with Steve Wozniak. His relationship with Ive over the next few years would become central to his second act at Apple. They balanced each other like Jobs’s favorite bandleaders, the more cynical John Lennon and the more sentimental Paul McCartney. Whereas Jobs was voluble, direct, and insistent, Ive was quiet, steady, and patient.

The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America

by

Margaret O'Mara

Published 8 Jul 2019

McKenna was unfazed by Apple’s garage setting and the co-founders’ scraggly looks. He’d worked with “lots of strange people” in the Valley already, and he was familiar with the Homebrew scene and the intriguing little enterprises bubbling up from it. The first meeting, however, was a bust. The Steves wanted help placing a Woz-authored article on the Apple II in Byte. It turned out that Steve Wozniak was much better at building elegant motherboards than crafting accessible prose; the piece was a rambling mess better suited for the hobbyist crowd back over at Dr. Dobb’s. McKenna told them it would have to be rewritten, and an offended Woz refused. Then I have nothing to offer you, replied McKenna.9 But Steve Jobs was not one to take no for an answer.

…

“Six people had already built their own computers, and almost everyone else wanted to.”3 The meeting attracted many of the usual suspects. Lee Felsenstein drove down from Berkeley. But it also drew in some new faces. Coming in from Cupertino was a former phone phreaker who’d spent his college years selling marginally legal “blue boxes” door to door in his dorm with a high school buddy. His name was Steve Wozniak, and his buddy’s name was Steve Jobs.4 Part swap meet, part intelligence gathering, part networking session, the biweekly Homebrew meetings quickly morphed into a local phenomenon. The second meeting moved from French’s garage to John McCarthy’s Stanford artificial-intelligence operation, then spilled out to the auditorium at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center on Sand Hill Road, attracting hundreds of people each month.

…

Featuring shakily hand-drawn portraits of club members (beards, long hair, and Coke-bottle glasses predominated), first-name references to meeting participants, and rough-and-ready page layouts, the newsletters echoed the PCC in their chatty informality, even as the Homebrew Computer Club grew in size and influence. Liza Loop stood out in the crowd. She was the only woman on the early Homebrew membership roster, and she was a computer newbie. To encourage swapping and sharing, Moore’s newsletters included blurbs from members about their skills and needs. Steve Wozniak’s was typical, showcasing dizzying technical virtuosity: “have TVT[ypewriter] of my own design . . . have my own version of Pong,” he wrote. “Working on a 17 chip TV chess display (includes 3 stored boards); a 30 chip TV display. Skills: digital design, interfacing, I/O devices, short on time, have schematics.”

A People’s History of Computing in the United States

by

Joy Lisi Rankin

Increasingly, people would have to purchase computers and software (now, devices and apps) for their personal and social computing. BASIC also figures prominently in the history of Apple. Steve Wozniak produced his own “Integer BASIC” for his homemade computer, built around MOS Technology’s 6502 microprocessor chip; he shared Integer BASIC , and he even published programs in Dr. Dobb’s Journal.29 When Wozniak’s high school chum Steve Jobs saw the computer, he proposed they team up to assemble and sell them. They named the computer Apple, and soon began working on a new version, the Apple II. Although Apple declared its philosophy 238 A People’s History of Computing in the United States was “to provide software for our machines f ree or at minimal cost,” Apple sought (aggressively) to sell its hardware.30 W hether they w ere called home computers, hobby computers, microcomputers, or personal computers, they were consumer products, purveyed by Steve Jobs.

…

International Business Machines, much more familiar as IBM, dominated the era when computers were the remote and room-size machines of the military-industrial complex. Then, around 1975, along came the California hobbyists who created personal computers and liberated us from the monolithic mainframes. They were young men in the greater San Francisco Bay Area, and they tinkered in their garages. They started companies: Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak established Apple; Bill Gates and Paul Allen developed Microsoft. Then, in the 1990s, along came the Internet to connect all of t hose personal computers, and the people using them. Another round of eccentric nerds (still all young white men)—Jeff Bezos, Sergey Brin, Larry Page, and Mark Zuckerberg among them—gave us Amazon, Google, Facebook, and the fiefdoms of Silicon Valley.

…

PLATO’s revolutionary plasma screens attracted the investment of the Control Data Corporation, which tried (unsuccessfully) to market its own version of the PLATO system to schools and universities. The BASIC programs shared freely around the Dartmouth network and on the pages of the People’s Computer Company newsletter fueled the imaginations of many—including Steve Wozniak and Bill Gates. Gates first learned to program in BASIC , the language on which he built his Microsoft empire. Wozniak adapted Tiny BASIC into Integer BASIC to program his homemade computer, the computer that attracted the partnership of Steve Jobs and launched Apple. And the Minnesota software library, mostly BASIC programs including The Oregon Trail, proved to be the ideal complement for the hardware of Apple Computers.

Visual Thinking: The Hidden Gifts of People Who Think in Pictures, Patterns, and Abstractions

by

Temple Grandin, Ph.d.

Published 11 Oct 2022

We mostly agree that maintaining and improving infrastructure is critical, but are we identifying, encouraging, and training the builders, welders, machinists, and engineers to manifest it? In other words, where are today’s clever engineers? From there we’ll look at the brilliant collaborations between verbal and visual thinkers, including the work of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, and architect Rem Koolhaas and engineer Cecil Balmond. We’ll look at studies that show how diverse thinkers advantage teams. Then we’ll explore the intersection of genius, neurodiversity, and visual thinking. Here we’ll describe artists and inventors, among them many visual thinkers and some on the autism spectrum as well.

…

Theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking took apart model trains and airplanes before making a simple computer out of recycled clock and telephone parts. Pioneering computer scientist and mathematician Grace Murray Hopper took apart all seven of the clocks in her family home. You probably wouldn’t be happy if your teen took apart your laptop, though you might be happier if he or she turned out to be the next Steve Wozniak. With adults, I suggest taking what I call the IKEA Test to help identify where you fall on the visual-verbal spectrum. It’s not strictly scientific, but it’s a fairly reliable shortcut to separating the more verbally inclined from the more visually inclined. Here’s the test: You buy a piece of furniture and are ready to put it together: Do you read the instructions or follow the pictures?

…

Grandfather liked to say, somewhat judgmentally, that original ideas did not come from company men, because company men all think in a similar way. They can develop, refine, and market an idea but cannot originate it. Of the five major tech companies, four started as a garage operation or in a college dorm room, with two brilliant minds tinkering and dreaming together: Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak created Apple, Bill Gates and Paul Allen created Microsoft, Sergey Brin and Larry Page created Google, and Mark Zuckerberg and Eduardo Saverin created Facebook. In the late 1930s, the Sperry Corporation hired two brothers, Russell and Sigurd Varian, who exemplify the concept of complementary minds.

The Hacker Crackdown

by

Bruce Sterling

Published 15 Mar 1992

Before computers and their phone-line modems entered American homes in gigantic numbers, phone phreaks had their own special telecommunications hardware gadget, the famous "blue box." This fraud device (now rendered increasingly useless by the digital evolution of the phone system) could trick switching systems into granting free access to long-distance lines. It did this by mimicking the system's own signal, a tone of 2600 hertz. Steven Jobs and Steve Wozniak, the founders of Apple Computer, Inc., once dabbled in selling blue-boxes in college dorms in California. For many, in the early days of phreaking, blue-boxing was scarcely perceived as "theft," but rather as a fun (if sneaky) way to use excess phone capacity harmlessly. After all, the long-distance lines were JUST SITTING THERE....

…

They have funds to burn on any sophisticated tool and toy that might happen to catch their fancy. And their fancy is quite extensive. The Deadhead community boasts any number of recording engineers, lighting experts, rock video mavens, electronic technicians of all descriptions. And the drift goes both ways. Steve Wozniak, Apple's co-founder, used to throw rock festivals. Silicon Valley rocks out. These are the 1990s, not the 1960s. Today, for a surprising number of people all over America, the supposed dividing line between Bohemian and technician simply no longer exists. People of this sort may have a set of windchimes and a dog with a knotted kerchief 'round its neck, but they're also quite likely to own a multimegabyte Macintosh running MIDI synthesizer software and trippy fractal simulations.

…

Furthermore, proclaimed the manifesto, the foundation would "fund, conduct, and support legal efforts to demonstrate that the Secret Service has exercised prior restraint on publications, limited free speech, conducted improper seizure of equipment and data, used undue force, and generally conducted itself in a fashion which is arbitrary, oppressive, and unconstitutional." "Crime and Puzzlement" was distributed far and wide through computer networking channels, and also printed in the Whole Earth Review. The sudden declaration of a coherent, politicized counter-strike from the ranks of hackerdom electrified the community. Steve Wozniak (perhaps a bit stung by the NuPrometheus scandal) swiftly offered to match any funds Kapor offered the Foundation. John Gilmore, one of the pioneers of Sun Microsystems, immediately offered his own extensive financial and personal support. Gilmore, an ardent libertarian, was to prove an eloquent advocate of electronic privacy issues, especially freedom from governmental and corporate computer-assisted surveillance of private citizens.

Whole Earth: The Many Lives of Stewart Brand

by

John Markoff

Published 22 Mar 2022

The deal proved to be a disappointment when the market for how-to computing manuals was quickly oversubscribed, but its magnitude alerted an industry that remained notoriously conservative about using new technologies that there might be a market for books about personal computing. Brockman had come to San Francisco in the spring of 1983 to attend the West Coast Computer Faire, an annual computer hobbyist exhibition. (It had been at the first Faire, held in 1977, that a twenty-two-year-old Steve Jobs and his twenty-six-year-old partner, Steve Wozniak, had introduced the Apple II.) Brockman’s literary agency was focused on scientists and technology writers. Now he embarked on a strategy of trying to find and represent star programmers, selling their work to the new software publishing industry. He had recently added an image of a floppy disk to the logo on his company stationery.

…

When Brand was at Stanford, placing a transistor in contact with the telephone handset and grounding it against the hinges of the phone booth produced a dial tone and—presto!—you were able to make a free phone call. Schooled in basic electronics by his ham-radio-operator father, Brand obtained a stack of the necessary transistors from Zack Electronics, a local supply store, and passed them out freely. He was ahead of his time: thirteen years later Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak would famously meet Captain Crunch (John Draper), an early hacker, who taught them how to build blue boxes, which they then sold in Wozniak’s dormitory at Berkeley. From the start his regular letters home were peppered with optimism and superlatives: “The class this year looks the best ever”; “the top man in the philosophy department”; “the liveliest guy in the classics department”; “experience excellent”; “a damn good man.”

…

When Brand had read the quote in a generally flattering Washington Post profile,[25] the words had stung. The Hackers Conference would become an annual event, drawing together a digital subculture that was passionate about the machines and programs they designed. The first gathering was marked by several heated debates that would continue long after everyone had gone home. While Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak argued that the term hacker represented the child in everyone, a well-known programmer named Brian Harvey warned there was a dark side as well, and the general public would soon come to see the word as synonymous with computer outlaws who broke into computers for sport and profit. Another important debate took place over the economic value of software.

Thinking Machines: The Inside Story of Artificial Intelligence and Our Race to Build the Future

by

Luke Dormehl

Published 10 Aug 2016

CHAPTER 2 Another Way to Build AI IT IS 2014 and, in the Google-owned London offices of an AI company called DeepMind, a computer whiles away the hours by playing an old Atari 2600 video game called Breakout. The game was designed in the early 1970s by two young men named Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, who later went on to start a company called Apple. Breakout is essentially a variation on the bat-and-ball tennis game Pong, except that instead of hitting the square ‘ball’ across the screen to another player, you fire it at a wall of bricks which smash on impact. The goal is to destroy all of the bricks.

…

He insisted on giving it spoken responses – which the original Siri app had not had – and got rid of the ability to type requests as well as just ask them, so as not to complicate the experience of using it. Apple also removed the bad language, and gave Siri the ability to pull information from Apple’s native iOS apps. Early Siri reviews were very positive when the iPhone 4s launched in 2011. Over time, however, cracks began to show. Embarrassingly, Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak – who left Apple decades earlier – was one vocal critic of the service, noting how Apple’s own-brand version seemed less intelligent than the original third-party Siri app. What had won him over about the first Siri, he said, was its ability to correctly answer the questions, ‘What are the five largest lakes in California?’

…

Epub ISBN: 9780753551653 Version 1.0 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 WH Allen, an imprint of Ebury Publishing, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London SW1V 2SA WH Allen is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com Copyright © Luke Dormehl 2016 Cover design: Two Associates Luke Dormehl has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 First published by WH Allen in 2016 www.eburypublishing.co.uk A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 9780753556740 Chapter 1 fn1 The answer, in case you want to prove yourself as smart as an AI, is 162. Chapter 3 fn1 Coffee, as it turns out, is a good starting point for a discussion about smart devices. Apple’s co-founder Steve Wozniak once said that he could never foresee a robot with enough general intelligence to walk into a strange house and make a cup of coffee. Exploring this hypothesis, some researchers now suggest the ‘coffee test’ as a potential measure for AGI, Artificial General Intelligence. I will discuss AGI later on in this book.

The Big Score

by

Michael S. Malone

Published 20 Jul 2021

In fact, though Silicon Valley is often described as a tight, incestuous family, Sporck knows very few of the presidents of the hot new computer, video game, and peripheral companies. Walking with a visitor across the lawn at the center of the company compound, Sporck asks about these young whiz kids, what they’re like. It is a week after Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak’s latest rock concert. Sporck says he doesn’t know any of these people, having only met Steve Jobs at some political event for Jerry Brown which Sporck found idiotic and walked out of. As the visitor describes some of the antics of these young tycoons, Sporck shakes his head. “You know,” he says, “us guys who started out at Fairchild and built all of these semiconductor companies, you know, when you get right down to it, we’re a pretty conservative, old-fashioned bunch.

…

But there has always been that insanity factor in the society of electrical engineers, a structural weakness that, given the right external pressure, can crack and send the individual crashing down into perdition, or at least a good time. Lee De Forest was an early case in point, with his run-ins with courts and his infatuation with movie stars. Shockley is another case, with his racial theories and genius sperm banks. The latter-day case, of course, is Steve Wozniak, with his rock festivals and Datsun commercials. For the most part, these occasional bouts with pixilation in the ranks were overwhelmed by the predominating soberness of the profession as a whole. This changed, however, with the rise of the modern entrepreneur, the man or woman who was just as much a businessperson as a scientist, who not only had to design the product but had to sell it to a skeptical market.

…

This one is built around an Alpha Beta supermarket, a main-line market that gets the folks who can’t afford Petrini’s. This shopping center also sports a Farrell’s Ice Cream Parlor, a Velvet Turtle restaurant, a renowned Szechuan restaurant, a video cassette store, and a thriving computer store owned by Apple founder Steve Wozniak’s brother. The fourth corner contains a bank and the only two-story building around: an office complex that holds, among others, the West Coast bureau of Hayden Publishing (Popular Computing, Electronic Design). Past Mary, Fremont passes another gas station. Unlike its subdued competitor down the road, this one is a self-serve, with an attached quick-stop market.

So Good They Can't Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work You Love

by

Cal Newport

Published 17 Sep 2012

It’s at this point that Jobs’s ascent begins to accelerate. He takes on $250,000 in funding from Mark Markkula and works with Steve Wozniak to produce a new computer design that is unambiguously too good to be ignored. There were other engineers in the Bay Area’s Homebrew Computer Club culture who could match Jobs’s and Wozniak’s technical skill, but Jobs had the insight to take on investment and to focus this technical energy toward producing a complete product. The result was the Apple II, a machine that leaped ahead of the competition: It had color graphics; the monitor and keyboard were integrated inside the case; the architecture was open, allowing rapid expansion of memory and peripherals (such as the floppy disk, which the Apple II was the first to introduce into mainstream use).

…

At one point, he left his job at Atari for several months to make a mendicants’ spiritual journey through India, and on returning home he began to train seriously at the nearby Los Altos Zen Center. In 1974, after Jobs’s return from India, a local engineer and entrepreneur named Alex Kamradt started a computer time-sharing company dubbed Call-in Computer. Kamradt approached Steve Wozniak to design a terminal device he could sell to clients to use for accessing his central computer. Unlike Jobs, Wozniak was a true electronics whiz who was obsessed with technology and had studied it formally at college. On the flip side, however, Wozniak couldn’t stomach business, so he allowed Jobs, a longtime friend, to handle the details of the arrangement.

…

Using this trio as our running example, I can now ask what it is specifically about these three careers that makes them so compelling? Here are the answers that I came up with: TRAITS THAT DEFINE GREAT WORK Creativity: Ira Glass, for example, is pushing the boundaries of radio, and winning armfuls of awards in the process. Impact: From the Apple II to the iPhone, Steve Jobs has changed the way we live our lives in the digital age. Control: No one tells Al Merrick when to wake up or what to wear. He’s not expected in an office from nine to five. Instead, his Channel Island Surfboards factory is located a block from the Santa Barbara beach, where Merrick still regularly spends time surfing. ( Jake Burton Carpenter, founder of Burton Snowboards, for example, recalls how negotiations for the merger between the two companies happened while he and Merrick waited for waves in a surf lineup.)

Apple in China: The Capture of the World's Greatest Company

by

Patrick McGee

Published 13 May 2025

Apple itself could have played this dominant role; in fact, it had played this role. At the behest of Steve Wozniak—overruling Jobs—the Apple II featured an open architecture with eight expansion slots and a floppy drive. This allowed third-party software and hardware companies to build applications for it, widening its appeal beyond hobbyists and gamers to the workplace. That openness gave rise, in October 1979, to a breakthrough digital spreadsheet tool, VisiCalc, the first “killer app” for personal computers. Along with EasyWriter, an early word processor, VisiCalc helped transform the Apple II from a plaything to a workhorse. The openness of the Apple II was a unique feature and proved critical to its success.

…

The Threat from Boca Raton—and Huntsville In a way, it was amazing Apple had made it this far against a field of rivals who could achieve lower cost and better distribution for every computer they sold. Apple’s survival was testament to the twin and somewhat contradictory forces of its founders. The Steve Wozniak–led Apple II computer, released in 1977, was the first personal computer to define a standard for others to follow, and it would be Apple’s number one revenue driver for an entire decade. The second force was the advanced nature of the Macintosh operating system (OS). It really was a decade ahead of its time when, in 1984, a boyish and handsome Steve Jobs, then just twenty-eight, unveiled the Mac with dramatic flair to a packed auditorium.

…

It lacked much third-party support, so it was even more isolated than the Mac. Jobs had commissioned an expensive, inefficient factory capable of handling 10,000 units per month—far more capacity than it would ever need. The poor decisions highlight the difficult-to-grasp nature of his peculiar genius. Whereas the brilliance of Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak was tangible—he could disassemble a computer, then rebuild it to work faster and with fewer parts—Jobs lacked such practical skills. But through instinct, passion, and an uncompromising vision, he could lead a team to build “insanely great” products. When things weren’t going well, however, his idiosyncratic traits felt overbearing and his taste could seem arbitrary.

Intertwingled: The Work and Influence of Ted Nelson (History of Computing)

by

Douglas R. Dechow

Published 2 Jul 2015

Forty years after Computer Lib, computers are far more sophisticated and the networks among digital objects are much richer and more complex. It is time to revisit fundamental assumptions of networked computing, such as the directionality of links, a point made by multiple speakers at the symposium—Wendy Hall, Jaron Lanier, Steve Wozniak, and Rob Akcsyn amongst them.1 Fig. 10.3Ordinary hypertext, with multi-directional links. From Literary Machines (Used with permission) 10.2.3 Managing Research Data Managing research data is similarly a problem of defining and maintaining relationships amongst multi-media objects. Research data do not stand alone.

…

Wing JM (2006) Computational thinking. Commun ACM 49(3) 18. Wozniak S (2014) In “Intertwingled: afternoon session #2.” Chapman University, Orange, California. Video timecode: 58:14. http://ibc.chapman.edu/Mediasite/Play/52694e57c4b546f0ba8814ec5d9223ae1d Footnotes 1For example, as Steve Wozniak said at Intertwingled, “At our computer club, the bible was Computer Lib” — referring to the Homebrew Computer Club, from which Apple Computer and other major elements of the turn to personal computers emerged [18]. 2“Computational thinking is the process of recognising aspects of computation in the world that surrounds us, and applying tools and techniques from Computer Science to understand and reason about both natural and artificial systems and processes” [5]. 3“Computational Media” has recently emerged as a name for the type of work that performs this interdisciplinary integration [15]. 4Kodu is both an influential system itself and the basis of Microsoft’s Project Spark, launched in October 2014. 5The first stage of our work is described in “Say it With Systems” [4].

…

From the age of about three or four I was particularly fascinated by “exclusive or” light switches, where you have a room with the need for switches at two different doors and so they are wired up in such a way that both switches control the light and you can turn it on or off from either door. As a child I then went on to explore in sequence: electricity, electronics, digital electronics and early computers. We had ancient computers at my school. We had a PDP-8 and then an LSI-11 and an Apple II and so on up through the history of computers. I was interested in each level of hardware: how the physics of transistors worked, how digital circuits were put together, and how CPUs operated. When I was young, I designed a simple CPU and a simple operating system. I asked my brother to sit underneath a desk, fed him instructions, and had him execute them.

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by

Klaus Schwab

Published 7 Jan 2021

Governments and companies must invest more in continuous retraining of workers, unions must be stronger but have a cooperative approach to business and government, and workers themselves should be positive and flexible about future economic challenges they and their country face. A Changing Business Landscape Tim Wu was still in elementary school in 1980, when he was one of the first of his class to get a personal computer: the Apple II. The now iconic computer propelled creators Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak to stardom and heralded a new era in technology. But for Tim and his brother, the Apple II was first and foremost an exciting way to get acquainted with a new technology. “My brother and I loved Apple, we were obsessed with it,” Wu told us.31 The two preteens would make it their hobby to get the computers chips out, reprogram them, and put them back in.

…

Kahn, The Yale Law Journal, January 2017 34 “Big Tech Has Too Much Monopoly Power—It's Right to Take It On,” Kenneth Rogoff, The Guardian, April 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/apr/02/big-tech-monopoly-power-elizabeth-warren-technology; Quote: “Here are titles of some recent articles: Paul Krugman's “Monopoly Capitalism Is Killing US Economy,” Joseph Stiglitz's “America Has a Monopoly Problem—and It's Huge,” and Kenneth Rogoff's “Big Tech Is a Big Problem”; “The Rise of Corporate Monopoly Power,” Zia Qureshi, Brookings, May 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2019/05/21/the-rise-of-corporate-market-power/. 35 “Steve Wozniak Says Apple Should've Split Up a Long Time Ago, Big Tech Is Too Big,” Bloomberg, August 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2019-08-27/steve-wozniak-says-apple-should-ve-split-up-a-long-time-ago-big-tech-is-too-big-video. 36 Some scholars do dispute this notion. Yuval Noah Harari, for example, is much less upbeat about the impact of the agricultural revolution on the quality and quantity of food supply on people. 37 A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens, Chapman & Hall, 1859. 38 “The Emma Goldman Papers,” Henry Clay Frick et al., University of California Press, 2003, https://www.lib.berkeley.edu/goldman/PublicationsoftheEmmaGoldmanPapers/samplebiographiesfromthedirectoryofindividuals.html. 39 “Historical Background and Development Of Social Security,” Social Security Administration, https://www.ssa.gov/history/briefhistory3.html. 40 “Standard Ogre,” The Economist, December 1999, https://www.economist.com/business/1999/12/23/standard-ogre. 41 “The Presidents of the United States of America”: Lyndon B.

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by

Klaus Schwab

and

Peter Vanham

Published 27 Jan 2021