Baxter: Rethink Robotics

description: industrial robot built by Rethink Robotics, a start-up company founded by Rodney Brooks

18 results

Machines of Loving Grace: The Quest for Common Ground Between Humans and Robots

by

John Markoff

Published 24 Aug 2015

Shockley’s prescience was so striking that when Rodney Brooks, himself a pioneering roboticist at the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory in the 1970s, read Brock’s article in IEEE Spectrum in 2013, he passed Shockley’s original 1951 memo around his company, Rethink Robotics, and asked his employees to guess when the memo had been written. No one came close. That memo predates by more than a half century Rethink’s Baxter robot, introduced in the fall of 2012. Yet Baxter is almost exactly what Shockley proposed in the 1950s—a trainable robot with an expressive “face” on an LCD screen, “hands,” “sensory organs,” “memory,” and, of course, a “brain.” The philosophical difference between Shockley and Brooks is that Brooks’s intent has been for Baxter to cooperate with human workers rather than replace them, taking over dull, repetitive tasks in a factory and leaving more creative work for humans.

…

The technical term for this relationship is “compliance,” and there is widespread belief among roboticists that over the next half decade these machines will be widely used in manufacturing, distribution, and even retail positions. Baxter is designed to be programmed easily by nontechnical workers. To teach the robot a new repetitive task, humans only have to guide the robot’s arms through the requisite motions and Baxter will automatically memorize the routine. When the robot was introduced, Rethink Robotics demonstrated Baxter’s capability to slowly pick up items on a conveyor belt and place them in new locations. This seemed like a relatively limited contribution to the workplace, but Brooks argues that the system will develop a library of capabilities over time and will increase its speed as new versions of its software become available.

…

Abbeel, Pieter, 268 Abelson, Robert, 180–181 Abovitz, Rony, 271–275 Active Ontologies, 304 Ad Hoc Committee on the Triple Revolution, 73–74 agent-based interfaces, 195–226. see also Siri (Apple) avatars, 304, 305 Baxter (robot), 195–196, 204–205, 205, 207 Brooks and, 201–204 CALO, 31, 297, 302–304, 310, 311 chatbots, 221–225, 304 early personal computing and, 196–201 ethics of, 339–342 “golemics” and, 208–215 Google and, 12–13, 341 Microsoft and, 187–191, 215–220 Rethink Robotics and, 204–208 singularity and, 220–221 Agents, Inc., 191–192 aging, of humans, 93–94, 236–237, 245, 327–332 “Alchemy and Artificial Intelligence” (Dreyfus), 177 Allen, Paul, 267, 268, 337 Alone Together (Turkle), 173, 221–222 Amazon, 97–98, 206, 247 Ambler (robot), 33, 202 Anderson, Chris, 88 Andreessen, Marc, 69 Apocalypse AI (Geraci), 85, 116–117 Apple. see also Siri (Apple) early history of, 7, 8, 214, 279–281, 307 iPhone, 23, 93, 239, 275, 281 iPod, 194, 275, 281 Jobs and, 13, 35, 112, 131, 194, 214, 241, 281–282, 320–323 Knowledge Navigator, 188, 300, 304, 305–310, 317, 318 labor force of, 83–84 Rubin and, 240 Sculley and, 35, 280, 300, 305, 306, 307, 317 Architecture Machine, The (Negroponte), 191 Architecture Machine Group, 306–307, 308–309 Arkin, Ronald, 333–335 Armer, Paul, 74 Aronson, Louise, 328 Artificial General Intelligence, 26 artificial intelligence (AI). see artificial intelligence (AI) history; autonomous vehicles; intelligence augmentation (IA) versus AI; labor force; robotics advancement; Siri (Apple) artificial intelligence (AI) history, 95–158. see also intelligence augmentation (IA) versus AI AI commercialization, 156–158 AI terminology, xii, 105–109 AI Winter, 16, 130–131, 140 Breiner and, 125–135 deep learning neural networks, 150–156, 151 early neural networks, 141–150 expert systems, 134–141, 285 McCarthy and, 109–115 Moravec and, 115–125 Silicon Valley inception, 95–99, 100, 256 SRI inception, 99–105 Strong artificial intelligence, 12, 26, 272 “Artificial Intelligence” (Lighthill), 130 “Artificial Intelligence of Hubert L.

The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies

by

Erik Brynjolfsson

and

Andrew McAfee

Published 20 Jan 2014

We got a sneak peek at these potential paradox-busters shortly before Rethink’s public unveiling of their first line of robots, named Baxter. Brooks invited us to the company’s headquarters in Boston to see these automatons, and to see what they could do. Baxter is instantly recognizable as a humanoid robot. It has two burly, jointed arms with claw-like grips for hands; a torso; and a head with an LCD face that swivels to ‘look at’ the nearest person. It doesn’t have legs, though; Rethink sidestepped the enormous challenges of automatic locomotion by putting Baxter on wheels and having it rely on people to get from place to place. The company’s analyses suggest that it can still do lots of useful work without the ability to move under his own power.

…

Entrepreneurs and managers are constantly making these types of decisions, weighing the relative costs of each type of input, as well as the effects on the quality, reliability, and variety of output that can be produced. Rod Brooks estimates that the Baxter robot we met in chapter 2 works for the equivalent of about four dollars per hour, including all costs.33 As we discussed at the start of this chapter, to the extent that a factory owner previously employed a human to do the same task that Baxter could do, the economic incentive would be to substitute capital (Baxter) for labor as long as the human was paid more than four dollars per hour. If output stays the same, and assuming no new hires are made in engineering, management, or sales at the company, it would increase the ratio of capital to labor input.* Compensation of the remaining workers could go up or down in the wake of Baxter’s arrival.

…

This imprecision presents no problem to a person (who simply sees the jars in the box, grabs them, and puts them on the conveyor belt), but traditional industrial automation has great difficulty with jelly jars that don’t show up in exactly the same place every time. In 2008 Brooks founded a new company, Rethink Robotics, to pursue and build untraditional industrial automation: robots that can pick and place jelly jars and handle the countless other imprecise tasks currently done by people in today’s factories. His ambition is to make some progress against Moravec’s paradox. What’s more, Brooks envisions creating robots that won’t need to be programmed by high-paid engineers; instead, the machines can be taught to do a task (or retaught to do a new one) by shop floor workers, each of whom need less than an hour of training to learn how to instruct their new mechanical colleagues.

Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future

by

Martin Ford

Published 4 May 2015

A Versatile Robotic Worker Industrial Perception’s robot is a highly specialized machine focused specifically on moving boxes with maximum efficiency. Boston-based Rethink Robotics has taken a different track with Baxter, a lightweight humanoid manufacturing robot that can easily be trained to perform a variety of repetitive tasks. Rethink was founded by Rodney Brooks, one of the world’s foremost robotics researchers at MIT and a co-founder of iRobot, the company that makes the Roomba automated vacuum cleaner as well as military robots used to defuse bombs in Iraq and Afghanistan. Baxter, which costs significantly less than a year’s wages for a typical US manufacturing worker, is essentially a scaled-down industrial robot that is designed to operate safely in close proximity to people.

…

Companies of all sizes were on hand to showcase robots designed to perform precision manufacturing, transport medical supplies between departments in large hospitals, or autonomously operate heavy equipment for agriculture and mining. There was a personal robot named “Budgee” capable of carrying up to fifty pounds of stuff around the house or at the store. A variety of educational robots focused on everything from encouraging technical creativity to assisting children with autism or learning disabilities. At the Rethink Robotics booth, Baxter had received Halloween training and was grasping small boxes of candy and then dropping them into pumpkin-shaped trick-or-treat buckets. There were also companies marketing components like motors, sensors, vision systems, electronic controllers, and the specialized software used to construct robots.

…

In contrast to industrial robots, which require complex and expensive programming, Baxter can be trained simply by moving its arms through the required motions. If a facility uses multiple robots, one Baxter can be trained and then the knowledge can be propagated to the others simply by plugging in a USB device. The robot can be adapted to a variety of tasks, including light assembly work, transferring parts between conveyer belts, packing products into retail packaging, or tending machines used in metal fabrication. Baxter is particularly talented at packing finished products into shipping boxes. K’NEX, a toy construction set manufacturer located in Hat-field, Pennsylvania, found that Baxter’s ability to pack its products tightly allowed the company to use 20–40 percent fewer boxes.5 Rethink’s robot also has two-dimensional machine vision capability powered by cameras on both wrists and can pick up parts and even perform basic quality-control inspections.

Superminds: The Surprising Power of People and Computers Thinking Together

by

Thomas W. Malone

Published 14 May 2018

The photograph is from the above paper and is available online at https://tangible.media.mit.edu/project/soundform, where you can also see a fascinating video of the system in operation. Photograph © Tangible Media Group, MIT Media Lab. Reprinted with permission. 13. Erico Guizzo and Evan Ackerman, “How Rethink Robotics Built Its New Baxter Robot Worker,” IEEE Spectrum, September 18, 2012, http://spectrum.ieee.org/robotics/industrial-robots/rethink-robotics-baxter-robot-factory-worker. 14. Robert Lee Hotz, “Neural Implants Let Paralyzed Man Take a Drink,” Wall Street Journal, May 21, 2015, http://www.wsj.com/articles/neural-implants-let-paralyzed-man-take-a-drink-1432231201; Tyson Aflalo, Spencer Kellis, Christian Klaes, Brian Lee, Ying Shi, Kelsie Shanfield, Stephanie Hayes-Jackson, et al., “Decoding Motor Imagery from the Posterior Parietal Cortex of a Tetraplegic Human,” Science 348, no. 6,237 (May 22, 2015): 906–910, http://science.sciencemag.org/content/348/6237/906.full, doi:10.1126/science.aaa5417.

…

Second, we may create robots that look like people just to satisfy our human desire to interact with humanlike creatures. For instance, Baxter is an industrial robot from Rethink Robotics designed to do the kind of physical tasks in factories that human workers do today. And it’s probably no accident that Baxter has a humanlike face mounted on its body between its humanlike arms, right where a human head would be. There’s no technical reason why a face or head is needed there, but presumably the designers of Baxter thought the humans in a factory would be more comfortable around a robot that sort of looked like a person. And if the future of AI is anything like the history of other information technologies, it will almost certainly be used for erotic purposes, too.

…

Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig, Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (New York: Prentice Hall, 1995). 2. Alan Turing, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” Mind 59 (1950): 433–60. 3. Wikipedia, s.v. “artificial intelligence,” accessed August 8, 2016, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_intelligence. 4. Rodney Brooks, “Artificial Intelligence Is a Tool, Not a Threat,” Rethink Robotics, November 10, 2014, http://www.rethinkrobotics.com/blog/artificial-intelligence-tool-threat. 5. David Ferrucci, e-mail message to the author, August 24, 2016. Ferrucci was the leader of the IBM team that developed the Watson technology. 6. See, for example, a review of this literature in Russell and Norvig, Artificial Intelligence, chapter 26. 7.

The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future

by

Kevin Kelly

Published 6 Jun 2016

To demand that artificial intelligence be humanlike is the same flawed logic as demanding that artificial flying be birdlike, with flapping wings. Robots, too, will think different. Consider Baxter, a revolutionary new workbot from Rethink Robotics. Designed by Rodney Brooks, the former MIT professor who invented the bestselling Roomba vacuum cleaner and its descendants, Baxter is an early example of a new class of industrial robots created to work alongside humans. Baxter does not look impressive. Sure, it’s got big strong arms and a flat-screen display like many industrial bots. And Baxter’s hands perform repetitive manual tasks, just as factory robots do. But it’s different in three significant ways.

…

See also books; ebooks and readers realism, 211–14, 216 real time, 66, 88, 104, 114–17, 131, 145 recommendation engines, 169 Red Dead Redemption, 227–30 Reddit, 136, 140, 143, 149, 264 Red Hat, 69 reference transactions, 285 relationship network analysis, 187 relativity theory, 288 remixing of ideas, 193–210 and economic growth, 193–95 and intellectual property issues, 207–10 legal issues associated with, 207–10 and reduced cost of creating content, 196–97 and rewindability, 204–7 and visual media, 197–203 remixing video, 197–98 renting, 117–18 replication of media, 206–9 Rethink Robotics, 51 revert functions, 270 reviews by users/readers, 21, 72–73, 139, 266 rewindability, 204–7, 247–48, 270 RFID chips, 283 Rheingold, Howard, 148–49 ride-share taxis, 252 ring tones, 250 Ripley’s Believe It or Not, 278 robots ability to think differently, 51–52 Baxter, 51–52 categories of jobs for, 54–59, 60 and digital storage capacity, 265 dolls, 36 emergence of, 49 industrial robots, 52–53 and mass customization, 173 new jobs related to, 57–58 and personal success, 58–59 personal workbots, 58–59 stages of robot replacement, 59–60 training, 52–53 trust in, 54 Romer, Paul, 193, 209 Rosedale, Phil, 219 Rowling, J.

…

Optimally, workers should be able to get materials to and from the robot or to tweak its controls by hand throughout the workday; isolation makes that difficult. Baxter, however, is aware. Using force-feedback technology to feel if it is colliding with a person or another bot, it is courteous. You can plug it into a wall socket in your garage and easily work right next to it. Second, anyone can train Baxter. It is not as fast, strong, or precise as other industrial robots, but it is smarter. To train the bot, you simply grab its arms and guide them in the correct motions and sequence. It’s a kind of “watch me do this” routine. Baxter learns the procedure and then repeats it. Any worker is capable of this show and tell; you don’t even have to be literate.

Free Money for All: A Basic Income Guarantee Solution for the Twenty-First Century

by

Mark Walker

Published 29 Nov 2015

Another example of robotic progress is Baxter from Rethink Robotics. Baxter is an industrial robot designed by Rodney Brooks, inventor of the Roomba robot. Let us consider the cost first. Unimate is usually credited with the installation of the first industrial robot in 1961.13 This robotic arm worked at a General Motors factory with hot die cast metal sorting and stacking. Unimate sold the robot at a loss: it cost $65 million to make and Unimate sold it for a paltry $18 million. Baxter costs more than 1,000 times less, retailing at $22,000. Even compared to many of its contemporary competitors, Baxter is a giant leap forward.

…

For example, a typical industrial robot that costs $100,000 at present might use an additional $400,000 in labor fees to have programmers write and debug code to instruct the robot how to perform its task. Baxter, in contrast, can be trained by factory workers: it is simply a matter of guiding Baxter’s arm to show it what needs to be done. Baxter learns by doing, rather than having new code input. This makes the lifetime cost of Baxter cheaper than many of its competitors ($22,000 versus $500,000). Robots like Baxter will revolutionize industrial production. As mentioned above, the robotic revolution is being spearheaded by specific purpose-built machines. And because of this, there are very few who are able to see the revolution in all its clarity, as it requires knowledge of developments in a number of specialized domains.

…

As mentioned above, the robotic revolution is being spearheaded by specific purpose-built machines. And because of this, there are very few who are able to see the revolution in all its clarity, as it requires knowledge of developments in a number of specialized domains. For example, when a reporter asked Rodney Brooks, inventor of both the aforementioned Roomba and Baxter robots, how long it might be before robots could replace McDonald’s workers, his response was very telling. Brooks claimed that “it might be 30 years before robots will cook for us.”14 His reasoning for this prediction is also interesting, “In a fast food place you’re not doing the same task very long. You’re always changing things on the fly, so you need special solutions.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution

by

Klaus Schwab

Published 11 Jan 2016

Positive impacts – Supply chain and logistics, eliminations – More leisure time – Improved health outcomes (big data for pharmaceutical gains in research and development) – Banking ATM as early adopter – More access to materials – Production “re-shoring” (i.e. replacing overseas workers with robots) Negative impacts – Job losses – Liability, accountability – Day-to-day social norms, end of 9-to-5 and 24-hour services – Hacking and cyber-risk The shift in action An article from The Fiscal Times appearing on CNBC.com states that: “Rethink Robotics released Baxter [in the fall of 2012] and received an overwhelming response from the manufacturing industry, selling out of their production capacity through April … [In April] Rethink launch[ed] a software platform that [allows] Baxter to do a more complex sequencing of tasks – for example, picking up a part, holding it in front of an inspection station and receiving a signal to place it in a ‘good’ or ‘not good’ pile.

…

Positive impacts – Supply chain and logistics, eliminations – More leisure time – Improved health outcomes (big data for pharmaceutical gains in research and development) – Banking ATM as early adopter – More access to materials – Production “re-shoring” (i.e. replacing overseas workers with robots) Negative impacts – Job losses – Liability, accountability – Day-to-day social norms, end of 9-to-5 and 24-hour services – Hacking and cyber-risk The shift in action An article from The Fiscal Times appearing on CNBC.com states that: “Rethink Robotics released Baxter [in the fall of 2012] and received an overwhelming response from the manufacturing industry, selling out of their production capacity through April … [In April] Rethink launch[ed] a software platform that [allows] Baxter to do a more complex sequencing of tasks – for example, picking up a part, holding it in front of an inspection station and receiving a signal to place it in a ‘good’ or ‘not good’ pile. The company also [released] a software development kit … that will allow third parties – like university robotics researchers – to create applications for Baxter.” In “The Robot Reality: Service Jobs Are Next to Go”, Blaire Briody, 26 March 2013, The Fiscal Times, http://www.cnbc.com/id/100592545 Shift 16: Bitcoin and the Blockchain The tipping point: 10% of global gross domestic product (GDP) stored on blockchain technology By 2025: 58% of respondents expected this tipping point to have occurred Bitcoin and digital currencies are based on the idea of a distributed trust mechanism called the “blockchain”, a way of keeping track of trusted transactions in a distributed fashion.

The Economic Singularity: Artificial Intelligence and the Death of Capitalism

by

Calum Chace

Published 17 Jul 2016

But the industrial robotics industry is changing: as well as growing quickly, its output is getting cheaper, safer and far more versatile. A landmark was reached in 2012 with the introduction of Baxter, a 3-foot tall robot (6 feet with his pedestal) from Rethink Robotics. The brainchild of Rodney Brooks, an Australian roboticist who used to be the director of the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, Baxter is much less dangerous to be around. By early 2015, Rethink had received over $100m in funding from venture capitalists, including the investment vehicle of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. Baxter was intended to disrupt the industrial robots market by being cheaper, safer, and easier to programme.

…

He is easier to programme because an operator can teach him new movements simply by physically moving his arms in the intended fashion. Baxter's short life has not been entirely plain sailing. Sales did not pick up as expected, and in December 2013, Rethink laid off around a quarter of its staff. One of the competitors stealing sales from Rethink is Universal Robots of Denmark, a manufacturer of small- and medium-sized robot arms. Universal increased sales to €30m in 2014, and aims to double its revenues every year until 2017. But Rethink remains well-funded, and in March 2015 it introduced a smaller, faster, more flexible robot arm called Sawyer. It can operate in more environments than Baxter, and can carry out more intricate movements.

…

In the initial event in 2004 the winning car drove just seven of the 150 miles of the track before crashing. A dozen years later, self-driving cars are demonstrably superior to human drivers in almost all circumstances, and they are closing the remaining gap fast. As far as robotics is concerned, we are at 2004 again. And don't forget the power of exponential improvement. In chapter 2.3 we met Baxter, a new generation of industrial robot, which is beginning to demonstrate that robots can be flexible, adaptable, and easy to instruct in new tasks. Research teams around the world are teaching robots to do intricate tasks. In October 2015, a consortium of Japanese companies unveiled the Laundroid, a robot capable of folding a shirt in four minutes.

Architects of Intelligence

by

Martin Ford

Published 16 Nov 2018

Now that we’re seeing the proliferation of AI impacting so many aspects of our society, people are appreciating that this field of AI and robotics is no longer just a computer science or engineering endeavor. The technology has come into society in a way that we have to think much more holistically around the societal integration and impact of these technologies. Look at a robot like Baxter, built by Rethink Robotics. It’s a manufacturing robot that’s designed to collaborate with humans on the assembly line, not to be roped off far from people but to work shoulder-to-shoulder with them. In order to do that, Baxter has got a face so that coworkers can anticipate, predict, and understand what the robot’s likely to do next. Its design is supporting our theory of mind so that we can collaborate with it.

…

RODNEY BROOKS We don’t have anything anywhere near as good as an insect, so I’m not afraid of superintelligence showing up anytime soon. CHAIRMAN, RETHINK ROBOTICS Rodney Brooks is widely recognized as one of the world’s foremost roboticists. Rodney co-founded iRobot Corporation, an industry leader in both consumer robotics (primarily the Roomba vacuum cleaner) and military robots, such as those used to defuse bombs in the Iraq war (iRobot divested its military robotics division in 2016). In 2008, Rodney co-founded a new company, Rethink Robotics, focused on building flexible, collaborative manufacturing robots that can safely work alongside human workers.

…

In 2017, the company recorded full-year revenue of $884 million and has, since launch, shipped over 20 million units. I think it’s fair to say the Roomba is the most successful robot ever in terms of numbers shipped, and that was really based on the insect-level intelligence that I had started developing at MIT around 1984. When I left MIT in 2010, I stepped down completely and started a company, Rethink Robotics, where we build robots that are used in factories throughout the world. We’ve shipped thousands of them to date. They’re different from conventional industrial robots in that they’re safe to be with, they don’t have to be caged, and you can show them what you want them to do. In the latest version of the software we use, Intera 5, when you show the robots what you want them to do, they actually write a program.

Humans Are Underrated: What High Achievers Know That Brilliant Machines Never Will

by

Geoff Colvin

Published 3 Aug 2015

Many more examples are appearing. You can train a Baxter robot (from Rethink Robotics) to do all kinds of things—pack or unpack boxes, take items to or from a conveyor belt, fold a T-shirt, carry things around, count them, inspect them—just by moving its arms and hands (“end-effectors”) in the desired way. Many previous industrial robots had to be surrounded by safety cages because they could do just one thing in one way, over and over, and that’s all they knew; if you got between a welding robot and the piece it was welding, you were in deep trouble. But Baxter doesn’t hurt anyone as it hums about the shop floor; it adapts its movements to its environment by sensing everything around it, including people.

…

This is known as Moravec’s paradox; see, among many discussions of this topic, Hans Moravec, Mind Children (Harvard University Press, 1988), and Pamela McCorduck, Machines Who Think (A. K. Peters Ltd., 2004). Google’s autonomous cars . . . Jennifer Cheeseman Day and Jeffrey Rosenthal, “Detailed Occupations and Median Earnings: 2008.” U.S. Census Bureau, http://www.census.gov/people/io/files/acs08_detailedoccupations.pdf. You can train a Baxter robot . . . http://www.rethinkrobotics.com/baxter/. Robots went into the wreckage . . . “Meet the Robots of Fukushima Daiichi,” IEEE Spectrum, 28 February 2014, http://spectrum.ieee.org/slideshow/robotics/industrial-robots/meet-the-robots-of-fukushima-daiichi. By 2008 about 12,000 combat robots . . . “Pushing the Boundaries of Traditional HRI,” Science and Technology Innovations, Fall 2013, p. 7.

The Deep Learning Revolution (The MIT Press)

by

Terrence J. Sejnowski

Published 27 Sep 2018

Elephants are highly social, have great memories, and are mechanical geniuses,13 but they don’t play chess.14 In 1990, Brooks went on to found iRobot, which has sold more than 10 million Roombas to clean even more floors. Industrial robots have stiff joints and powerful servomotors, which makes them look and feel mechanical. In 2008, Brooks started Rethink Robotics, a company that built a robot called “Baxter” with pliant joints, so its arms could be moved around (figure 12.3). Instead of having to write a program to move Baxter’s arms, each arm could be moved through the desired motions, and it would program itself to repeat the sequence of motions. Movellan went one step further than Brooks and developed a robot baby called “Diego San” (manufactured in Japan),15 whose motors were pneumatic (driven by air pressure) and all of whose forty-four joints were compliant compared to the stiff torque motors used in most industrial robots (figure 12.4).

…

And, indeed, it takes about twelve months before a baby biped human starts walking without falling over. Rodney Brooks (figure 12.3), who made a brief appearance in chapter 2, Figure 12.3 Rodney Brooks oversees Baxter, who is preparing to place a plug into a hole on the table. Brooks is a serial entrepreneur who previously founded iRobot, which makes Roombas, and now Rethink, which makes Baxters. Courtesy of Rod Brooks. 178 Chapter 12 wanted to build six-legged robots that could walk like insects. He invented a new type of controller that could sequence the actions of the six legs to move his robo-cockroach forward and remain stable.

…

See also TD-Gammon backgammon board, 144f learning how to play, 143–146, 148–149 Backpropagation (backprop) learning algorithm, 114f, 217, 299n2 Backpropagation of errors (backprop), 111b, 112, 118, 148 Bag-of-words model, 251 Ballard, Dana H., 96, 297nn11–12, 314n8 Baltimore, David A., 307n5 Bar-Joseph, Ziv, 319n13 Barlow, Horace, 84, 296n8 Barry, Susan R., 294n5 Bartlett, Marian “Marni” Stewart, 181–182, 181f, 184, 308nn19–20 Barto, Andrew, 144, 146f Bartol, Thomas M., Jr., 296n14, 300n18 Basal ganglia, motivation and, 151, 153–154 Bates, Elizabeth A., 107, 298n24 Bats, 263–264 Index Bavelier, Daphne, 189–190, 309n33 Baxter (robot), 177f, 178 Bayes, Thomas, 128 Bayes networks, 128 Bear off pieces, 148 Beck, Andrew H., 287n17 Beer Bottle Pass, 4, 5f Bees, learning in, 151 Behaviorism and behaviorists, 149, 247–248 cognitive science and, 248, 249f, 250, 253 Behrens, M. Margarita, 299n27 Belief networks, 52 Bell, Anthony J., 82 infomax ICA algorithm, 81, 83, 83f, 84, 86 neural nets and, 82, 90, 296n15 photograph, 83f on water structure, 296n15 writings, 79, 85f, 295n2, 295n4, 295n6, 296n9, 306n24 Bellman, Richard, 145, 304n4 Bellman equation.

Only Humans Need Apply: Winners and Losers in the Age of Smart Machines

by

Thomas H. Davenport

and

Julia Kirby

Published 23 May 2016

Jim Lawton, whom we also mentioned in Chapter 2, is chief product and marketing officer at Rethink Robotics, a “collaborative robotics” manufacturer in Boston. Rethink was founded and is led by Rodney Brooks, a former MIT professor, who also plays the role of chief technology officer. He handles the vision and the research. It is Lawton’s job to understand what customers want from robots and translate that into product capabilities. He’s also an evangelist for the idea that robots and people can collaborate with each other. Rethink’s robot models, which now include the cutely named Baxter and Sawyer, don’t require a lot of detailed programming.

…

As robots develop more intelligence, better machine vision, and greater ability to make decisions, they will become a combination of other types of cognitive technologies, but with the added ability to transform the physical environment (remember the “Great Convergence” toward the right in the chart at the beginning of this chapter). There are already, as we have discussed, systems to understand text and speech, systems to engage in intelligent Q&A with humans, and systems to recognize a variety of images. It’s just that they’re not yet embedded in the brain of a robot. Jim Lawton, the head of products at Rethink Robotics, commented to us in an interview: “An important area of experimentation today is around the intersection of collaborative robots, big data, and deep learning. The goal is to combine automation of physical tasks and cognitive tasks. For example, a robot could start combining all the information about how much torque is applied in a screw.

…

Rule-based underwriting in insurance has also been expanded to new areas—for example, medical and life insurance underwriting—from its initial base in property and casualty insurance. Another domain of automation in which transparency and ease of use are increasing is robotics. We mentioned the company Rethink Robotics (and their head of product and marketing, Jim Lawton) earlier in this chapter. That company and several others focus on the “collaborative robots” segment, in which humans and robots can work closely alongside each other. Whereas with a traditional robot, changing the pattern of movements and actions would require changes to a complex programming language, changing the behaviors of collaborative robots typically involves simply demonstrating the required movements to the robot.

Scrum: The Art of Doing Twice the Work in Half the Time

by

Jeff Sutherland

and

Jj Sutherland

Published 29 Sep 2014

For many years he was the head of robotics and artificial intelligence at MIT, and that spidery robot I met, dubbed “Genghis Khan,” now sits in the Smithsonian as a collector’s item. By now you’re probably familiar with one of Brooks’s companies, iRobot, which makes the Roomba vacuum cleaner and uses the same adaptive intelligence to clean your floors that Genghis Khan used to chase me around my office. His latest innovation at Rethink Robotics, the Baxter robot, can work collaboratively with humans in a common workspace. I was inspired by Brooks’s work. And in 1993 I took those ideas with me to a company called Easel, where I was hired as VP of Object Technology. The executives at Easel wanted my team to develop a completely new product line in six months that would be aimed at some of their biggest customers—such as the Ford Motor Company, which used their software to design and build internal applications.

…

Olympic Basketball team, 2004 U.S., 7.1 Omaha Beach OODA loop, 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 8.1, 185, 8.2, 8.3 OpenView Venture Partners, 1.1, 3.1, 5.1, 8.1 Org Chart Orient, 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 8.1, 185 output, as measurable standard Overburden Palm paper airplanes, PDCA cycle in making Pashler, Harold passivity, elimination of PatientKeeper, 7.1, 7.2 patterns: negative in Scrum PDCA cycle (Plan, Do, Check, Act), 2.1, 2.2, 5.1, 7.1 peer review “Perils of Obedience, The” (Milgram) Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs) personal growth Petraeus, David Pets.com, 8.1 planning, 1.1, 6.1 Waterfall, see Waterfall method weddings, 6.1, 6.2, 6.3 Planning Poker, 6.1, 6.2, 9.1 Porath, Christine Portal poverty, 9.1, 9.2, 9.3 prioritization, 1.1, 7.1, 7.2, 8.1 process, happiness in product attributes, 172 Product Backlog, see Backlog product development: incremental value in productivity happiness and hours worked and, 5.1, 103, 8.1 Scrum and Product Marketing Product Owner, 2.1, 8.1, 8.2, app.1, app.2 essential characteristics of feedback and, 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4 incremental value and as internal customer product vision, 8.1, 172, 8.2 Backlog and profit margins Progress Out of Poverty Index projects, prioritizing between, 93 ProPublica, purpose, 2.1, 7.1 Putnam, Lawrence Quattro Pro for Windows Rand Corporation, 6.1, 6.2 rat race Reasonableness, 5.1, 5.2, 5.3 relative size, 6.1, 6.2, 6.3 releases, incremental, see incremental development and delivery renovations, time frame for Rethink Robotics retrospective revenue, 8.1, 8.2, 8.3 in venture capital review rituals re-work RF-4C Phantom reconnaisance jet rhythm, 5.1, 5.2 risk robots, 2.1, 4.1, 9.1 rockets Rodner, Don Rogers Commission Roomba Roosevelt, Theodore rugby as analogy New Zealand All Blacks team in Rustenburg, Eelco Said, Khaled Salesforce.com, 1.1, 3.1 Agile practices at sales teams Sanbonmatsu, David Schwaber, Ken Scrum Backlog as power of freedom and rules in and Heathcare.gov, 1.1 implementing in Japan, 2.1 managers’ difficulty with and Medco, 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, 6.4 at NPR at OpenView origins at Easel, 2.1, 4.1, 4.2, 4.3 origins in software development of positive behavior rewarded in productivity increases with reaching greatness with at Salesforce.com, 3.1 system examined and fixed in team size in time conceptualized in transparency in at Valve workweek and, 103 Scrum board, 7.1, 7.2, 8.1, 9.1, app.1 in education “SCRUM Development Process” (Sutherland and Schwaber) Scrum Master, 3.1, 4.1, 7.1, 8.1, 8.2, app.1, app.2, app.3 “Secret Weapon: High-value Target Teams as Organizational Innovation” (Lamb and Munsing) self-control, decision making and Senate Judiciary Committee set-based concurrent engineering Shook, John short cycles short term memory, retention in Shu Ha Ri, 2.1, 9.1 single-tasking sizing, relative, 6.1, 6.2 skills small teams, superiority of, 3.1, 3.2 SMART government Smithsonian Institution soccer social motivation software, fixing bugs in software development, 2.1, 3.1 Sony Soviet Union space travel, private specialization, communication damaged by, 4.1, 4.2 Special Operations Forces (SOF), U.S.

…

Ashram College assholes, 5.1, 5.2, 7.1 Association for Computing Machinery AT&T ATMs (Automatic Teller Machines) autonomy, 2.1, 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 7.1 avionics Backlog, 2.1, 4.1, 6.1, 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4, 8.5, app.1 priorities and, 8.1, 8.2, 8.3 and product vision Bailar, John bandwagon effect, 6.1, 6.2, 6.3 Bangladesh banks, financial crisis and, 9.1, 9.2 barriers Barton, Brent, 6.1, 6.2 Baxter robot Bell, Steve Bell Labs, 2.1, 4.1 BellSouth Ben-Shahar, Tal, 7.1, 7.2 Big Picture Bikhchandani, Sushil blame, in teams, 3.1, 3.2 BMW Booz Allen Hamilton, Katzenbach Center at Borland Software Corporation Boston, Mass., 1.1, 3.1, 3.2 Boston Celtics Bowens, Maneka Boyd, John, 8.1, 8.2 brain mapping, multitasking and Brooks, Fred Brooks, Rodney, 2.1, 9.1 Brooks’s Law Brown, Rachel bureaucracy, 9.1, 9.2 Burndown Chart, 8.1, 9.1, 9.2, app.1 cabals Cairo call center, Zappos cell phones, 5.1, 9.1 driving and, 5.1, 5.2 Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), 3.1, 6.1 Challenger disaster, 3.1, 3.2 Change Control Boards, 8.1, 9.1 Change for Free change orders Change or Die Chicago Tribune, churches, Scrum at Cohn, Mike Cold War collaboration, 7.1, 7.2 Colorado, Sunshine laws in Colorado, University of, Medical School communication saturation, 4.1, 4.2, 8.1 Community Knowledge Workers (CKWs) complacency, dangers of complex adaptive systems, 2.1, 2.2 Cone of Uncertainty, 119 “Constant Error in Psychological Ratings, A” (Thorndike) context switching, loss to continuous improvement Happiness Metric and happy bubbles and, 7.1 contracts Change for Free in government Coomer, Greg Copenhagen Coplien, Jim Coram, Robert corporate culture change in cost overruns Cowan, Nelson cross-functionality, 2.1, 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, 7.1, 8.1 Crozier, William customer-responsive models customers: external vs. internal wants of cynicism Daily Stand-Ups (Daily Scrum), 3.1, 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 7.1, 7.2, 8.1, 8.2, app.1 Dalkey, Norman D-day DeAngelo, Michael Decide, 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 8.1, 185 decision loop decision making Product Owner and self-control and Declaration of Independence Delivering Happiness (Hsieh), Delphi method, 6.1, 6.2 Deming, W.

Future Crimes: Everything Is Connected, Everyone Is Vulnerable and What We Can Do About It

by

Marc Goodman

Published 24 Feb 2015

Industrial robots are growing exponentially cheaper, more efficient, and more user-friendly, and perhaps no other robot exemplifies this trend as much as Baxter, the cute low-cost industrial bot from Rethink Robotics. At $22,000, it is a tenth of the price of its predecessors. More impressive is the fact that it works right out of the box and can be up and running in just an hour, as opposed to the eighteen months it took to integrate the previous generations of industrial robots into a factory operation. Baxter can learn to do simple tasks, such as “pick and place” objects on an assembly line, in just five minutes. It has an adorable face on its head-mounted display screen and two highly dexterous arms, which can move in any direction required to get a task done.

…

ROS is free and open source, providing modules for robotics simulation, movement, vision, navigation, perception, facial recognition, and so forth. It is exactly these types of open-source community efforts and shared experience building, barely conceivable just a few years ago, that allow companies like Rethink Robotics to offer Baxter for $22,000 instead of $200,000. ROS, originally developed at Willow Garage in 2007, is now maintained by the Open Source Robotics Foundation and runs on everything from small toys to large industrial robots. As noted numerous times throughout this book, there has never been a computer that could not be hacked, a dictum that applies to robots as well, with important implications for our common security.

…

It has an adorable face on its head-mounted display screen and two highly dexterous arms, which can move in any direction required to get a task done. Baxter requires no special programming and learns by using its computer vision to watch an employee perform a task, which the bot can repeat ad infinitum. As costs drop even further, these robots will be competitively priced compared with cheap overseas labor, and many hope a rise in domestic robotics use may lead to a renaissance in American manufacturing. Today robots are showing up everywhere from restaurants to hospitals. In more than 150 medical centers, Aethon’s TUG robots can be summoned by a smart-phone app to autonomously travel throughout the corridors to deliver medicines, patient meals, and laundry, replacing work previously done by orderlies.

Exponential Organizations: Why New Organizations Are Ten Times Better, Faster, and Cheaper Than Yours (And What to Do About It)

by

Salim Ismail

and

Yuri van Geest

Published 17 Oct 2014

As outlined in our Chapter One table on falling technology costs, ten years ago it cost $100,000 to establish a DNA synthesis lab; today that price is down to about $5,000. And while an industrial robot would set you back a million bucks a decade ago, the latest model of that same robot (Rethink Robotics’ Baxter robot) is now available for $22,000. In the realm of MEMS sensors, the outlay for accelerometers, microphones, gyroscopes, cameras and magnetometers has dropped 80 percent or more compared to five years ago, according to McKinsey. Finally, a 3D printer carried a $40,000 price tag seven years ago; today it costs just $100.

…

AI production monitoring Leverage sensor data, algorithms and AI to detect early faults in production and resolve them long before the product comes to market, thus radically reducing repairs, returns and recalls. Customizable and programmable robots Easily programmable and customizable robots for manufacturing, helping workers or removing the need for them to do repetitive and heavy tasks altogether (e.g., Baxter, Unbounded Robotics, Otherlab). Sustainable production and logistics Greener and more self-sufficient production driven by robo-transport, sensors, AI, flexible solar panels and perovskite solar cells. Nanomaterials (graphene) that can be added to buildings, vehicles, machines and equipment. Transformation in Logistics (road, water and air transport).

The Job: The Future of Work in the Modern Era

by

Ellen Ruppel Shell

Published 22 Oct 2018

“For Amazon and all Internet retailers, moving things from one place to another is just about their entire cost,” he told me. “Basically people in that industry are used as an extension of a forklift. Human forklift extenders are pretty expensive. Robot arms cut that cost drastically.” Sawyer, an industrial robot created by Boston-based Rethink Robotics, offers an impressive illustration of how all-embracing those arms can be. Sawyer is the brainchild of Rodney Brooks, the inventor of both Roomba, the vacuum-cleaning robot, and PackBot, the robot used to clear bunkers in Iraq and Afghanistan and the World Trade Center after 9/11. Unlike Roomba and PackBot, Sawyer looks almost human—it has an animated flat-screen face and wheels where its legs should be.

…

every human on the Amazon payroll See, for example, Olivia LaVecchia and Stacy Mitchell, “Report: How Amazon’s Tightening Grip on the Economy Is Stifling Competition, Eroding Jobs, and Threatening Communities,” Institute for Local Self-Reliance, November 29, 2016, https://ilsr.org/amazon-stranglehold/. “Labor is the highest-cost factor” Tim Linder, “New Patent Report,” Connected World Magazine, January 28, 2014, https://connectedworld.com/new-patent-report-january-28-2014/. Sawyer (and his older brother, the two-armed Baxter robot) Dr. Brooks gave $4 per hour as the approximate cost of employing Baxter in response to a question at the Technonomy 2012 Conference in Tucson. See John Markoff, Andrew McAfee, and Rodney Brooks, “Where’s My Robot?,” Techonomy, November 2012, http://techonomy.com/conf/12-tucson/future-of-work/wheres-my-robot/. the Weather Channel broadcasts 18 million forecasts John Koetsier, “Data Deluge: What People Do on the Internet, Every Minute of Every Day,” Inc.com, July 25, 2017, https://www.inc.com/john-koetsier/every-minute-on-the-internet-2017-new-numbers-to-b.html.

…

The robot can sense and manipulate objects almost as quickly and as fluidly as a human and demands very little in return: while traditional industrial robots require costly engineers and programmers to write and debug their code, a high school dropout can learn to program Sawyer in less than five minutes. Brooks once estimated that, all told, Sawyer (and his older brother, the two-armed Baxter robot) would work for a “wage” equivalent to less than $4 an hour. Robots loom large in discussions of work and its future, a conversation that can get mired in false assumptions. Until recently, many economists were skeptical that automation could permanently displace human workers on a large scale.

Frugal Innovation: How to Do Better With Less

by

Jaideep Prabhu Navi Radjou

Published 15 Feb 2015

It works with innovators outside the group, with a view to building a global additive manufacturing ecosystem to spread the use of the technology. The main challenge is developing sufficient capacity for large- and small-scale industrial needs; if achieved, this will create many new manufacturing businesses and jobs. In addition to 3D printing, the plummeting cost of industrial robots – such as Baxter, a $25,000 humanoid robot sold by Rethink Robotics – is unleashing a wave of automation in factories that could not only boost manufacturers’ productivity and quality but also their agility. SRI International, a research institute based in Silicon Valley, is working on a project funded by DARPA (Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency) to develop nimbler, smaller and lighter robotic arms that will be ten times cheaper and consume 20 times less energy than existing industrial robots, and yet perform complex tasks in dynamic settings more reliably.

…

MacArthur Foundation 14 John Deere 67 John Lewis 195 Johnson & Johnson 100, 111 Johnson, Warren 98 Jones, Don 112 jugaad (frugal ingenuity) 199, 202 Jugaad Innovation (Radjou, Prabhu and Ahuja, 2012) xvii, 17 just-in-time design 33–4 K Kaeser, Joe 217 Kalanick, Travis 163 Kalundborg (Denmark) 160 kanju 201 Karkal, Shamir 124 Kaufman, Ben 50–1, 126 Kawai, Daisuke 29–30 Kelly, John 199–200 Kennedy, President John 138 Kenya 57, 200–1 key performance indicators see KPIs Khan Academy 16–17, 113–14, 164 Khan, Salman (Sal) 16–17, 113–14 Kickstarter 17, 48, 137, 138 KieranTimberlake 196 Kimberly-Clark 25, 145 Kingfisher 86–7, 91, 97, 157, 158–9, 185–6, 192–3, 208 KissKissBankBank 17, 137 Knox, Steve 145 Knudstorp, Jørgen Vig 37, 68, 69 Kobori, Michael 83, 100 KPIs (key performance indicators) 38–9, 67, 91–2, 185–6, 208 Kuhndt, Michael 194 Kurniawan, Arie 151–2 L La Chose 108 La Poste 92–3, 157 La Ruche qui dit Oui 137 “labs on a chip” 52 Lacheret, Yves 173–5 Lada 1 laser cutters 134, 166 Laskey, Alex 119 last-mile challenge 57, 146, 156 L’Atelier 168–9 Latin America 161 lattice organisation 63–4 Laury, Véronique 208 Laville, Elisabeth 91 Lawrence, Jamie 185, 192–3, 208 LCA (life-cycle assessment) 196–7 leaders 179, 203–5, 214, 217 lean manufacturing 192 leanness 33–4, 41, 42, 170, 192 Learnbox 114 learning by doing 173, 179 learning organisations 179 leasing 123 Lee, Deishin 159 Lego 51, 126 Lego Group 37, 68, 69, 144 Legrand 157 Lenovo 56 Leroy, Adolphe 127 Leroy Merlin 127–8 Leslie, Garthen 150–1 Lever, William Hesketh 96 Levi Strauss & Co 60, 82–4, 100, 122–3 Lewis, Dijuana 212 life cycle of buildings 196 see also product life cycle life-cycle assessment (LCA) 196–7 life-cycle costs 12, 24, 196 Lifebuoy soap 95, 97 lifespan of companies 154 lighting 32, 56, 123, 201 “lightweighting” 47 linear development cycles 21, 23 linear model of production 80–1 Link 131 littleBits 51 Livi, Daniele 88 Livi, Vittorio 88 local communities 52, 57, 146, 206–7 local markets 183–4 Local Motors 52, 129, 152 local solutions 188, 201–2 local sourcing 51–2, 56, 137, 174, 181 localisation 56, 137 Locavesting (Cortese, 2011) 138 Logan car 2–3, 12, 179, 198–9 logistics 46, 57–8, 161, 191, 207 longevity 121, 124 Lopez, Maribel 65–6 Lopez Research 65–6 L’Oréal 174 Los Alamos National Laboratory 170 low-cost airlines 60, 121 low-cost innovation 11 low-income markets 12–13, 161, 203, 207 Lowry, Adam 81–2 M m-health 109, 111–12 M-KOPA 201 M-Pesa 57, 201 M3D 48, 132 McDonough Braungart Design Chemistry (MBDC) 84 McDonough, William 82 McGregor, Douglas 63 MacGyvers 17–18, 130, 134, 167 McKelvey, Jim 135 McKinsey & Company 81, 87, 209 mainstream, frugal products in 216 maintenance 66, 75, 76, 124, 187 costs 48–9, 66 Mainwaring, Simon 8 Maistre, Christophe de 187–8, 216 Maker Faire 18, 133–4 Maker platform 70 makers 18, 133–4, 145 manufacturing 20th-century model 46, 55, 80–1 additive 47–9 continuous 44–5 costs 47, 48, 52 decentralised 9, 44, 51–2 frugal 44–54 integration with logistics 57–8 new approaches 50–4 social 50–1 subtractive method 48 tools for 47, 47–50 Margarine Unie 96 market 15, 28, 38, 64, 186, 189, 192 R&D and 21, 26, 33, 34 market research 25, 61, 139, 141 market share 100 marketing 21–2, 24, 36, 61–3, 91, 116–20, 131, 139 and R&D 34, 37, 37–8 marketing teams 143, 150 markets 12–13, 42, 62, 215 see also emerging markets Marks & Spencer (M&S) 97, 215 Plan A 90, 156, 179–81, 183–4, 186–7, 214 Marriott 140 Mars 57, 158–9, 161 Martin Marietta 159 Martin, Tod 154 mass customisation 9, 46, 47, 48, 57–8 mass market 189 mass marketing 21–2 mass production 9, 46, 57, 58, 74, 129, 196 Massachusetts Institute of Technology see MIT massive open online courses see MOOCs materials 3, 47, 48, 73, 92, 161 costs 153, 161, 190 recyclable 74, 81, 196 recycled 77, 81–2, 83, 86, 89, 183, 193 renewable 77, 86 repurposing 93 see also C2C; reuse Mayhew, Stephen 35, 36 Mazoyer, Eric 90 Mazzella, Frédéric 163 MBDC (McDonough Braungart Design Chemistry) 84 MDI 16 measurable goals 185–6 Mechanical Engineer Laboratory (MEL) 52 “MEcosystems” 154–5, 156–8 Medicare 110 medication 111–12 Medicity 211 MedStartr 17 MEL (Mechanical Engineer Laboratory) 52 mental models 2, 193–203, 206, 216 Mercure 173 Merlin, Rose 127 Mestrallet, Gérard 53, 54 method (company) 81–2 Mexico 38, 56 Michelin 160 micro-factories 51–2, 52, 66, 129, 152 micro-robots 52 Microsoft 38 Microsoft Kinect 130 Microsoft Word 24 middle classes 197–8, 216 Migicovsky, Eric 137–8 Mikkiche, Karim 199 millennials 7, 14, 17, 131–2, 137, 141, 142 MindCET 165 miniaturisation 52, 53–4 Mint.com 125 MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) 44–5, 107, 130, 134, 202 mobile health see m-health mobile phones 24, 32, 61, 129–30, 130, 168, 174 emerging market use 198 infrastructure 56, 198 see also smartphones mobile production units 66–7 mobile technologies 16, 17, 103, 133, 174, 200–1, 207 Mocana 151 Mochon, Daniel 132 modular design 67, 90 modular production units 66–7 Modularer Querbaukasten see MQB “mompreneurs” 145 Mondelez 158–9 Money Dashboard 125 Moneythink 162 monitoring 65–6, 106, 131 Monopoly 144 MOOCs (massive open online courses) 60, 61, 112, 113, 114, 164 Morieux, Yves 64 Morocco 207 Morris, Robert 199–200 motivation, employees 178, 180, 186, 192, 205–8 motivational approaches to shaping consumer behaviour 105–6 Motorola 56 MQB (Modularer Querbaukasten) 44, 45–6 Mulally, Alan 70, 166 Mulcahy, Simon 157 Mulliez family 126–7 Mulliez, Vianney 13, 126 multi-nodal innovation 202–3 Munari, Bruno 93 Murray, Mike 48–9 Musk, Elon 172 N Nano car 119, 156 National Geographic 102 natural capital, loss of 158–9 Natural Capital Leaders Platform 158–9 natural resources 45, 86 depletion 7, 72, 105, 153, 158–9 see also resources NCR 55–6 near-shoring 55 Nelson, Simon 113 Nemo, Sophie-Noëlle 93 Nest Labs 98–100, 103 Nestlé 31, 44, 68, 78, 94, 158–9, 194, 195 NetPositive plan 86, 208 networking 152–3, 153 new materials 47, 92 New Matter 132 new technologies 21, 27 Newtopia 32 next-generation customers 121–2 next-generation manufacturing techniques 44–6, 46–7 see also frugal manufacturing Nigeria 152, 197–8 Nike 84 NineSigma 151 Nissan 4, 4–5, 44, 199 see also Renault-Nissan non-governmental organisations 167 non-profit organisations 161, 162, 202 Nooyi, Indra 217 Norman, Donald 120 Norris, Greg 196 North American companies 216–17 North American market 22 Northrup Grumman 68 Norton, Michael 132 Norway 103 Novartis 44–5, 215 Novotel 173, 174 nudging 100, 108, 111, 117, 162 Nussbaum, Bruce 140 O O2 147 Obama, President Barack 6, 8, 13, 134, 138, 208 obsolescence, planned 24, 121 offshoring 55 Oh, Amy 145 Ohayon, Elie 71–2 Oliver Wyman 22 Olocco, Gregory 206 O’Marah, Kevin 58 on-demand services 39, 124 online communities 31, 50, 61, 134 online marketing 143 online retailing 60, 132 onshoring 55 Opel 4 open innovation 104, 151, 152, 153, 154 open-source approach 48, 129, 134, 135, 172 open-source hardware 51, 52, 89, 130, 135, 139 open-source software 48, 130, 132, 144–5, 167 OpenIDEO 142 operating costs 45, 215 Opower 103, 109, 119 Orange 157 Orbitz 173 organisational change 36–7, 90–1, 176, 177–90, 203–8, 213–14, 216 business models 190–3 mental models 193–203 organisational culture 36–7, 170, 176, 177–9, 213–14, 217 efficacy focus 181–3 entrepreneurial 76, 173 see also organisational change organisational structure 63–5, 69 outsourcing 59, 143, 146 over-engineering 27, 42, 170 Overby, Christine 25 ownership 9 Oxylane Group 127 P P&G (Procter & Gamble) 19, 31, 58, 94, 117, 123, 145, 195 packaging 57, 96, 195 Page, Larry 63 “pain points” 29, 30, 31 Palmer, Michael 212 Palo Alto Junior League 20 ParkatmyHouse 17, 63, 85 Parker, Philip 61 participation, customers 128–9 partner ecosystems 153, 154, 200 partners 65, 72, 148, 153, 156–8 sharing data with 59–60 see also distributors; hyper-collaboration; suppliers Partners in Care Foundation 202 partnerships 41, 42, 152–3, 156–7, 171–2, 174, 191 with SMBs 173, 174, 175 with start-ups 20, 164–5, 175 with suppliers 192–3 see also hyper-collaboration patents 171–2 Payne, Alex 124 PE International 196 Pearson 164–5, 167, 181–3, 186, 215 Pebble 137–8 peer-to-peer economic model 10 peer-to-peer lending 10 peer-to-peer sales 60 peer-to-peer sharing 136–7 Pélisson, Gérard 172–3 PepsiCo 38, 40, 179, 190, 194, 215 performance 47, 73, 77, 80, 95 of employees 69 Pernod Ricard 157 personalisation 9, 45, 46, 48, 62, 129–30, 132, 149 Peters, Tom 21 pharmaceutical industry 13, 22, 23, 33, 58, 171, 181 continuous manufacturing 44–6 see also GSK Philippines 191 Philips 56, 84, 100, 123 Philips Lighting 32 Picaud, Philippe 122 Piggy Mojo 119 piggybacking 57 Piketty, Thomas 6 Plan A (M&S) 90, 156, 179–81, 183–4, 186–7, 214 Planet 21 (Accor) 174–5 planned obsolescence 24, 121 Plastyc 17 Plumridge, Rupert 18 point-of-sale data 58 Poland 103 pollution 74, 78, 87, 116, 187, 200 Polman, Paul 11, 72, 77, 94, 203–5, 217 portfolio management tools 27, 33 Portugal 55, 103 postponement 57–8 Potočnik, Janez 8, 79 Prabhu, Arun 25 Prahalad, C.K. 12 predictive analytics 32–3 predictive maintenance 66, 67–8 Priceline 173 pricing 81, 117 processes digitising 65–6 entrenched 14–16 re-engineering 74 simplifying 169, 173 Procter & Gamble see P&G procurement priorities 67–8 product life cycle 21, 75, 92, 186 costs 12, 24, 196 sustainability 73–5 product-sharing initiatives 87 production costs 9, 83 productivity 49, 59, 65, 79–80, 153 staff 14 profit 14, 105 Progressive 100, 116 Project Ara 130 promotion 61–3 Propeller Health 111 prosumers xix–xx, 17–18, 125, 126–33, 136–7, 148, 154 empowering and engaging 139–46 see also horizontal economy Protomax 159 prototypes 31–2, 50, 144, 152 prototyping 42, 52, 65, 152, 167, 192, 206 public 50–1, 215 public sector, working with 161–2 publishers 17, 61 Pullman 173 Puma 194 purchasing power 5–6, 216 pyramidal model of production 51 pyramidal organisations 69 Q Qarnot Computing 89 Qualcomm 84 Qualcomm Life 112 quality 3, 11–12, 15, 24, 45, 49, 82, 206, 216 high 1, 9, 93, 198, 216 measure of 105 versus quantity 8, 23 quality of life 8, 204 Quicken 19–21 Quirky 50–1, 126, 150–1, 152 R R&D 35, 67, 92, 151 big-ticket programmes 35–6 and business development 37–8 China 40, 188, 206 customer focus 27, 39, 43 frugal approach 12, 26–33, 82 global networks 39–40 incentives 38–9 industrial model 2, 21–6, 33, 36, 42 market-focused, agile model 26–33 and marketing 34, 37, 37–8 recommendations for managers 34–41 speed 23, 27, 34, 149 spending 15, 22, 23, 28, 141, 149, 152, 171, 187 technology culture 14–15, 38–9 see also Air Liquide; Ford; GSK; IBM; immersion; Renault; SNCF; Tarkett; Unilever R&D labs 9, 21–6, 70, 149, 218 in emerging markets 40, 188, 200 R&D teams 26, 34, 38–9, 65, 127, 150, 194–5 hackers as 142 innovation brokering 168 shaping customer behaviour 120–2 Raspberry Pi 135–6, 164 Ratti, Carlo 107 raw materials see materials real-time demand signals 58, 59 Rebours, Christophe 157–8 recession 5–6, 6, 46, 131, 180 Reckitt Benckiser 102 recommendations for managers flexing assets 65–71 R&D 34–41 shaping consumer behaviour 116–24 sustainability 90–3 recruiting 70–1 recyclable materials 74, 81, 196 recyclable products 3, 73, 159, 195–6 recycled materials 77, 81–2, 83, 86, 89, 183, 193 recycling 8, 9, 87, 93, 142, 159 e-waste 87–8 electronic and electrical goods (EU) 8, 79 by Tarkett 73–7 water 83, 175 see also C2C; circular economy Recy’Go 92–3 regional champions 182 regulation 7–8, 13, 78–9, 103, 216 Reich, Joshua 124 RelayRides 17 Renault 1–5, 12, 117, 156–7, 179 Renault-Nissan 4–5, 40, 198–9, 215 renewable energy 8, 53, 74, 86, 91, 136, 142, 196 renewable materials 77, 86 Replicator 132 repurposing 93 Requardt, Hermann 189 reshoring 55–6 resource constraints 4–5, 217 resource efficiency 7–8, 46, 47–9, 79, 190 Resource Revolution (Heck, Rogers and Carroll, 2014) 87–8 resources 40, 42, 73, 86, 197, 199 consumption 9, 26, 73–7, 101–2 costs 78, 203 depletion 7, 72, 105, 153, 158–9 reducing use 45, 52, 65, 73–7, 104, 199, 203 saving 72, 77, 200 scarcity 22, 46, 72, 73, 77–8, 80, 158–9, 190, 203 sharing 56–7, 159–61, 167 substitution 92 wasting 169–70 retailers 56, 129, 214 “big-box” 9, 18, 137 Rethink Robotics 49 return on investment 22, 197 reuse 9, 73, 76–7, 81, 84–5, 92–3, 200 see also C2C revenues, generating 77, 167, 180 reverse innovation 202–3 rewards 37, 178, 208 Riboud, Franck 66, 184, 217 Rifkin, Jeremy 9–10 robots 47, 49–50, 70, 144–5, 150 Rock Health 151 Rogers, Jay 129 Rogers, Matt 87–8 Romania 2–3, 103 rookie mindset 164, 168 Rose, Stuart 179–80, 180 Roulin, Anne 195 Ryan, Eric 81–2 Ryanair 60 S S-Oil 106 SaaS (software as a service) 60 Saatchi & Saatchi 70–1 Saatchi & Saatchi + Duke 71–2, 143 sales function 15, 21, 25–6, 36, 116–18, 146 Salesforce.com 157 Santi, Paolo 108 SAP 59, 186 Saunders, Charles 211 savings 115 Sawa Orchards 29–31 Scandinavian countries 6–7 see also Norway Schmidt, Eric 136 Schneider Electric 150 Schulman, Dan 161–2 Schumacher, E.F. 104–5, 105 Schweitzer, Louis 1, 2, 3, 4, 179 SCM (supply chain management) systems 59 SCOR (supply chain operations reference) model 67 Seattle 107 SEB 157 self-sufficiency 8 selling less 123–4 senior managers 122–4, 199 see also CEOs; organisational change sensors 65–6, 106, 118, 135, 201 services 9, 41–3, 67–8, 124, 149 frugal 60–3, 216 value-added 62–3, 76, 150, 206, 209 Shapeways 51, 132 shareholders 14, 15, 76, 123–4, 180, 204–5 sharing 9–10, 193 assets 159–61, 167 customers 156–8 ideas 63–4 intellectual assets 171–2 knowledge 153 peer-to-peer 136–9 resources 56–7, 159–61, 167 sharing economy 9–10, 17, 57, 77, 80, 84–7, 108, 124 peer-to-peer sharing 136–9 sharing between companies 159–60 shipping costs 55, 59 shopping experience 121–2 SIEH hotel group 172–3 Siemens 117–18, 150, 187–9, 215, 216 Sigismondi, Pier Luigi 100 Silicon Valley 42, 98, 109, 150, 151, 162, 175 silos, breaking out of 36–7 Simple Bank 124–5 simplicity 8, 41, 64–5, 170, 194 Singapore 175 Six Sigma 11 Skillshare 85 SkyPlus 62 Small is Beautiful (Schumacher, 1973) 104–5 “small is beautiful” values 8 small and medium-sized businesses see SMBs Smart + Connected Communities 29 SMART car 119–20 SMART strategy (Siemens) 188–9 smartphones 17, 100, 106, 118, 130, 131, 135, 198 in health care 110, 111 see also apps SmartScan 29 SMBs (small and medium-sized businesses) 173, 174, 175, 176 SMS-based systems 42–3 SnapShot 116 SNCF 41–3, 156–7, 167 SoapBox 28–9 social business model 206–7 social comparison 109 social development 14 social goals 94 social learning 113 social manufacturing 47, 50–1 social media 16, 71, 85, 106, 108, 168, 174 for marketing 61, 62, 143 mining 29, 58 social pressure of 119 tools 109, 141 and transaction costs 133 see also Facebook; social networks; Twitter social networks 29, 71, 72, 132–3, 145, 146 see also Facebook; Twitter social pressure 119 social problems 82, 101–2, 141, 142, 153, 161–2, 204 social responsibility 7, 10, 14, 141, 142, 197, 204 corporate 77, 82, 94, 161 social sector, working with 161–2 “social tinkerers” 134–5 socialising education 112–14 Sofitel 173 software 72 software as a service (SaaS) 60 solar power 136, 201 sourcing, local 51–2, 56 Southwest Airlines 60 Spain 5, 6, 103 Spark 48 speed dating 175, 176 spending, on R&D 15, 22, 23, 28, 141, 149, 152, 171, 187 spiral economy 77, 87–90 SRI International 49, 52 staff see employees Stampanato, Gary 55 standards 78, 196 Starbucks 7, 140 start-ups 16–17, 40–1, 61, 89, 110, 145, 148, 150, 169, 216 investing in 137–8, 157 as partners 42, 72, 153, 175, 191, 206 see also Nest Labs; Silicon Valley Statoil 160 Steelcase 142 Stem 151 Stepner, Diana 165 Stewart, Emma 196–7 Stewart, Osamuyimen 201–2 Sto Corp 84 Stora Enso 195 storytelling 112, 113 Strategy& see Booz & Company Subramanian, Prabhu 114 substitution of resources 92 subtractive manufacturing 48 Sun Tzu 158 suppliers 67–8, 83, 148, 153, 167, 176, 192–3 collaboration with 76, 155–6 sharing with 59–60, 91 visibility 59–60 supply chain management see SCM supply chain operations reference (SCOR) model 67 supply chains 34, 36, 54, 65, 107, 137, 192–3 carbon footprint 156 costs 58, 84 decentralisation 66–7 frugal 54–60 integrating 161 small-circuit 137 sustainability 137 visibility 34, 59–60 support 135, 152 sustainability xix, 9, 12, 72, 77–80, 82, 97, 186 certification 84 as competitive advantage 80 consumers and 95, 97, 101–4 core design principle 82–4, 93, 195–6 and growth 76, 80, 104–5 perceptions of 15–16, 80, 91 recommendations for managers 90–3 regulatory demand for 78–9, 216 standard bearers of 80, 97, 215 see also Accor; circular economy; Kingfisher; Marks & Spencer; Tarkett; Unilever sustainable design 82–4 see also C2C sustainable distribution 57, 161 sustainable growth 72, 76–7 sustainable lifestyles 107–8 Sustainable Living Plan (Unilever) 94–7, 179, 203–4 sustainable manufacturing 9, 52 T “T-shaped” employees 70–1 take-back programmes 9, 75, 77, 78 Tally 196–7 Tarkett 73–7, 80, 84 TaskRabbit 85 Tata Motors 16, 119 Taylor, Frederick 71 technical design 37–8 technical support, by customers 146 technology 2, 14–15, 21–2, 26, 27 TechShop 9, 70, 134–5, 152, 166–7 telecoms sector 53, 56 Telefónica 147 telematic monitoring 116 Ternois, Laurence 42 Tesco 102 Tesla Motors 92, 172 testing 28, 42, 141, 170, 192 Texas Industries 159 Textoris, Vincent 127 TGV Lab 42–3 thermostats 98–100 thinking, entrenched 14–16 Thompson, Gav 147 Timberland 90 time 4, 7, 11, 41, 72, 129, 170, 200 constraints 36, 42 see also development cycle tinkerers 17–18, 133–5, 144, 150, 152, 153, 165–7, 168 TiVo 62 Tohamy, Noha 59–60 top-down change 177–8 top-down management 69 Total 157 total quality management (TQM) 11 total volatile organic compounds see TVOC Toyota 44, 100 Toyota Sweden 106–7 TQM (total quality management) 11 traffic 108, 116, 201 training 76, 93, 152, 167, 170, 189 transaction costs 133 transparency 178, 185 transport 46, 57, 96, 156–7 Transport for London 195 TrashTrack 107 Travelocity 174 trial and error 173, 179 Trout, Bernhardt 45 trust 7, 37, 143 TVOC (total volatile organic compounds) 74, 77 Twitter 29, 62, 135, 143, 147 U Uber 136, 163 Ubuntu 202 Uchiyama, Shunichi 50 UCLA Health 202–3 Udacity 61, 112 UK 194 budget cuts 6 consumer empowerment 103 industrial symbiosis 160 savings 115 sharing 85, 138 “un-management” 63–4, 64 Unboundary 154 Unilever 11, 31, 57, 97, 100, 142, 203–5, 215 and sustainability 94–7, 104, 179, 203–4 University of Cambridge Engineering Design Centre (EDC) 194–5 Inclusive Design team 31 Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL) 158–9 upcycling 77, 88–9, 93, 159 upselling 189 Upton, Eben 135–6 US 8, 38, 44, 87, 115, 133, 188 access to financial services 13, 17, 161–2 ageing population 194 ageing workforce 13 commuting 131 consumer spending 5, 6, 103 crowdfunding 137–8, 138 economic pressures 5, 6 energy use 103, 119, 196 environmental awareness 7, 102 frugal innovation in 215–16, 218 health care 13, 110, 208–13, 213 intellectual property 171 onshoring 55 regulation 8, 78, 216 sharing 85, 138–9 shifting production from China to 55, 56 tinkering culture 18, 133–4 user communities 62, 89 user interfaces 98, 99 user-friendliness 194 Utopies 91 V validators 144 value 11, 132, 177, 186, 189–90 aspirational 88–9 to customers 6–7, 21, 77, 87, 131, 203 from employees 217 shareholder value 14 value chains 9, 80, 128–9, 143, 159–60, 190, 215 value engineering 192 “value gap” 54–5 value-added services 62–3, 76, 150, 206, 209 values 6–7, 14, 178, 205 Vandebroek, Sophie 169 Vasanthakumar, Vaithegi 182–3 Vats, Tanmaya 190, 192 vehicle fleets, sharing 57, 161 Verbaken, Joop 118 vertical integration 133, 154 virtual prototyping 65 virtuous cycle 212–13 visibility 34, 59–60 visible learning 112–13 visioning sessions 193–4 visualisation 106–8 Vitality 111 Volac 158–9 Volkswagen 4, 44, 45–6, 129, 144 Volvo 62 W wage costs 48 wages, in emerging markets 55 Waitrose, local suppliers 56 Walker, James 87 walking the walk 122–3 Waller, Sam 195 Walmart 9, 18, 56, 162, 216 Walton, Sam 9 Wan Jia 144 Washington DC 123 waste 24, 87–9, 107, 159–60, 175, 192, 196 beautifying 88–9, 93 e-waste 24, 79, 87–8, 121 of energy 119 post-consumer 9, 75, 77, 78, 83 reducing 47, 74, 85, 96, 180, 209 of resources 169–70 in US health-care system 209 see also C2C; recycling; reuse water 78, 83, 104, 106, 158, 175, 188, 206 water consumption 79, 82–3, 100, 196 reducing 74, 75, 79, 104, 122–3, 174, 183 wealth 105, 218 Wear It Share It (Wishi) 85 Weijmarshausen, Peter 51 well-being 104–5 Wham-O 56 Whirlpool 36 “wicked” problems 153 wireless technologies 65–6 Wiseman, Liz 164 Wishi (Wear It Share It) 85 Witty, Andrew 35, 35–6, 37, 39, 217 W.L.

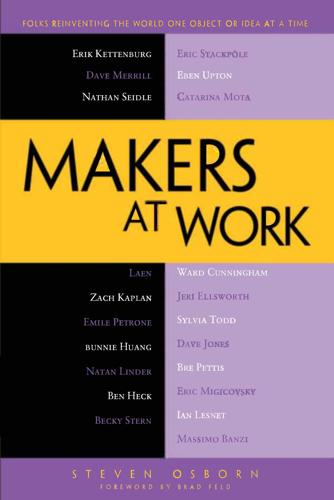

Makers at Work: Folks Reinventing the World One Object or Idea at a Time

by

Steven Osborn

Published 17 Sep 2013

He was cofounder, chairman and CTO of iRobot. You know, Roombas, Packbots and all that. In 2008 he started Heartland Robotics. Rod was looking for a design engineer-type of person to work on the user interface. I ended up being employee number ten and the lead user interface guy, at what is now Rethink Robotics, on the product they now call Baxter—but which at that point in time didn’t really exist. Well, it existed in theory, I guess. Heartland was starting to build it, which was pretty exciting. From that point on, I wasn’t sure if I would end up at MIT, but it didn’t matter because I was doing pretty cool stuff with Rod.