On the Slow Train: Twelve Great British Railway Journeys

by

Michael Williams

Published 1 Apr 2010

Virtually unchanged since it was built in 1852, with granite buildings, wooden canopies and semaphore signals (authentically ‘lower quadrant’ in the GWR style), it looks for all the world as though it has been transplanted from a model railway exhibition. With half an hour to go till departure, I buy the local morning paper, the Western Morning News, whose headline reads, ‘Future bright for delightful railway lines’. Although the future is less bright, I think, for newspapers like this one, who are undergoing their own Beeching axe all over the country as declining circulations put the parish pump out of business and the Internet takes over. Who would have bet, back in 1963, that the St Ives line would prosper, yet newspapers, like this once-mighty daily paper of Devon and Cornwall would face oblivion? ‘There were few pleasures in England that could beat the small three-coach branch-line train like this one from St Erth to St Ives,’ wrote Paul Theroux in his 1983 book The Kingdom by the Sea.

…

This is the route that Chaucer’s pilgrims took – and from the train there is a fine panorama of downland, woodland, orchards, lakes, dykes and marshland. Running through the villages of Wye, Chilham and Chartham, this is as beautiful as any secondary railway in Britain – lucky it was electrified in British Rail’s 1955 Modernisation Plan, since this almost certainly saved it from the Beeching axe. But Graeme Bunker, the man in charge of the Cathedrals Express, is less interested in the scenery than whether we’re going to get to Canterbury on time. The appropriately-named Bunker is a fully qualified steam fireman, he tells me, ‘though you can tell from my newly pressed shirt today that I won’t be doing any firing.

…

By the end of the 1950s, the infrastructure of the old North London was like something from a Gothic horror movie. Water dripped through ceilings, algae ate away at elegant carvings, slates dropped from roofs and once-splendid wooden structures mouldered away with dry rot. Weeds grew through cracks in the platforms. It was the perfect scenario for the Beeching axe. But change was in the air. There were the first inklings that the endless advance of the motor car might end up strangling London, and local authorities along the line roused themselves to save it from closure. Jo Grimond, leader of the Liberal Party, wrote an article in the Manchester Guardian suggesting that it should be incorporated in the Tube map, a status it has only recently fully achieved, nearly half a century later.

British Rail

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 9 Jun 2022

Oddly, far from producing a series of recommendations, the report put forward a series of options – always, in PR terms, a bad idea – that were in direct conflict with one another. For example, it recommended boosting freight services on lines that elsewhere it sought to close and suggested shutting the line between Spalding and March, which had already fallen foul of the Beeching axe. The Guardian did not hold back, calling it ‘a really rotten report’.23 It was the second part, which considered a series of options for cuts, that would ensure the report would soon be consigned to the dustbin of history and put Serpell up there with Beeching and Marples in a list of trainspotters’ hate figures.

…

More fundamental forces were at work and the organization’s growing deficit was the result of the high capital debt incurred at nationalization, rising staff costs (labour shortages were understandably exploited by well-organized unions) and, crucially, increased competition from cars and lorries which led to a decline in passenger and freight revenues. A failure to grasp the principles of railway economics was to lead to the most infamous period in British Railways’ history: the publication in 1963 of the Beeching report and its aftermath. If the Modernisation Plan was a positive outcome of the conjunction of a number of political factors, the arrival of Dr Richard Beeching at the head of British Railways was precisely the opposite. There were malign forces behind his arrival, and they were largely instigated by the appointment in 1959 of his boss, Ernest Marples, as transport minister.

…

As David Henshaw puts it, ‘The report completely ignored [implementing] various cost-measures that had been under consideration both at home and abroad for several decades; measures that might have turned marginal lines into profitable concerns.’14 Indeed, in the run-up to the publication of Beeching’s Reshaping of British Railways report on 27 March 1963, government ministers made sure that the perception of the railway as a failing industry would be the core message picked up by the media.15 In a report to a Cabinet meeting in early March, Marples set out precisely how he wanted the Beeching report to be presented and acted upon. Speed was of the essence in implementing his plan, and basically what he considered the busybodies of the local Transport Users’ Consultative Committees were neutered by limits on the amount of time they could spend considering the impact of closures. The Cabinet agreed that the British Railways Board’s proposals as set out in the report should be implemented as soon as possible.

Fire and Steam: A New History of the Railways in Britain

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 1 Mar 2009

These electrification schemes were definitely the exception, and BR was similarly slow to make use of diesel technology. The failure to convert many local and branch services to diesel was a missed opportunity given that the resulting cost economies could have made these lines far more resistant to the Beeching axe wielded in the 1960s. This was not for lack of available technology. As far back as 1921, one of Colonel Stephens’s railways, the Weston Clevedon and Portishead, had introduced a petrol-engined railcar on its fourteen-mile length and in Ireland the first diesel railcars in the British Isles started running on the small County Donegal Railways in 1926.

…

And because British Railways was now run by powerful regional managers, who were all vying for the largest slice of the cake for their patch, there was never any coherent programme to focus the investment where it was most needed. Local managers came up with crazy schemes such as electrifying vast swathes of line in the Eastern Region that served remote communities in the Lincolnshire fens (which soon fell to the Beeching axe). The London Midland Region tried to bid for the ridiculous number of 660 electric locomotives for the West Coast Main Line when 100 later sufficed. Such proposals were rejected but other daft schemes went ahead, notably the £1.6m (£30m today) Bletchley flyover on the West Coast line which was never used and survives today as a monument to incompetent planning.

…

Inevitably, given the line was a risky financial proposition from the start, the company that built it quickly became incorporated into its bigger neighbour, the Great Eastern, with the shareholders losing much of their investment. The line, like so many built in this period, was closed following the Beeching Report, with passenger services ceasing in 1964 and freight the following year. There were, quite literally, hundreds of similar lines spreading around Britain. Even the Isle of Wight, an island just fifteen by ten miles, acquired thirty-two miles of railway by 18754 and eventually fifty-five by the end of the century, built by no fewer than eight different companies.

Last Trains: Dr Beeching and the Death of Rural England

by

Charles Loft

Published 27 Mar 2013

The Treasury’s ultimate responsibility for the investment programmes of nationalised industries fostered a belief that it needed to develop a picture of future needs against which to judge those programmes. Efforts to apply this principle to transport spending were central to the policy behind the Beeching Report. In turn, the report was one of a series of measures the Conservatives hoped would convince the electorate that they were the standard-bearers of modernisation, and Labour’s opposition to closures sat uncomfortably with Harold Wilson’s attempts to present himself as the moderniser par excellence. This book argues that the Beeching Report was the outcome of a genuine modernisation of Whitehall’s management of the economy. Its form and presentation were a reflection of what was imagined to be wrong with Britain; its limitations reflected the difficulties of modernising Britain.

…

Barbara Castle and the stable network 12 Aftermath: the management of decline 13 Conclusion: ultra-modern horror Glossary Acknowledgements Select bibliography Notes Index Plates Copyright Chapter 1 Introduction: a wound that has not healed On a September evening in 1964, a branch line terminus in the north of England waited for the Beeching Axe to fall. As the last train from Carlisle pulled into the tiny terminus at Silloth, the usual diesel replaced by a steam locomotive for the occasion, passengers in the packed coaches gasped to see a crowd of between 5,000 and 9,000 people spilling across the tracks and a group of folk singers performing ‘The Beeching Blues’.

…

The Commission had missed an opportunity to provoke a different conclusion, but it had had little incentive to take it. Even if the Commission had been interested in pursuing social subsidies, would it have made any difference to Melton Constable? Unsurprisingly, the line there from Sheringham did not survive the Beeching Axe, inflicting the limited, if intensely felt, hardship discussed in Chapter 1. Given the small numbers involved it is hard to imagine that any kind of social analysis would have justified keeping it open. By the 1980s only the Sheringham to Cromer line remained, the population of Melton had roughly halved and the heart of the M&GN was reduced to some relics in an industrial estate and a couple of iron brackets from the station incorporated into a bus shelter.

Rush Hour: How 500 Million Commuters Survive the Daily Journey to Work

by

Iain Gately

Published 6 Nov 2014

Passenger rail journeys fell from a peak of over 1.1 billion in 1959 to around 650 million in 1980. A proportion of the fall was caused by the so-called ‘Beeching cuts’, named after Dr Richard Beeching, who produced two reports, in 1963 and 1965, which recommended that British Railways’ network should be pruned back to trunk lines and major branches. Several thousand miles of tracks were closed, including some commuter lines, although the Beeching axe fell mainly on rural stations, many of which had never been popular or profitable. The cuts were resented by the public, some of whom looked beyond the present inconvenience of losing their local station.*3 In April 1964, for instance, Barbara Preston had a letter published in the Guardian protesting about the planned closure of some of Manchester’s commuter routes: ‘is this what is really necessary here and now?’

…

Trams, trolleybuses and railways augmented these subway systems. The first two were for short-hop journeys; the latter, in theory, enabled every citizen to expand his or her range to the horizon and beyond. The Soviet rail system was growing while its counterparts in the West were contracting. In the 1960s, when the Beeching cuts removed several thousand miles of track from service in Britain, the USSR added nearly 500 kilometres every year. However, these were mostly for moving freight rather than people. Indeed, the freedom of movement that commuting implied was discouraged by the Soviets. Factories were built in wildernesses and tower-block suburbs were built around them, with dedicated transit systems to carry workers between the two.

…

It was once the seat of the Bishops of Winchester, in whose palace Henry V prepared himself before leaving for France and the Battle of Agincourt, and where Queen Mary I waited for King Philip of Spain to arrive in the country for their wedding. It’s now something of a commuter-shed serving the nearby cities of Winchester, Portsmouth and Southampton. Its railway station was closed in the Beeching cuts of the 1960s, and the nearest surviving station at Botley is four miles away along a twisting country road that has several crosses, with bunches of flowers scattered around them, where recent fatal accidents have occurred. There’s a limited bus service, which takes forever to go anywhere. There are no designated cycle paths.

On the Slow Train Again

by

Michael Williams

Published 7 Apr 2011

There’s the sound of blackbirds singing on this warm spring morning, high in the ancient trees around us, but there’s also the unmistakable staccàto of a train door slamming. In the little loop line platform is a 3-CIG three-coach electric train named Farringford built in 1963, the year of the infamous Beeching Report, retired from its duties on express trains to Brighton and Portsmouth and serving out its final days shuttling up and down the five-and-a-half-mile branch line from Brockenhurst to Lymington. Anoraks will know that CIG stands for ‘corridor express train running on the Brighton line’, the Brighton route having the operating code IG.

…

Then through Trowbridge, the pretty county town of Wiltshire, birthplace of Sir Isaac Pitman, whose system of shorthand bears his name, and winding past Freshford, which played the part of Titfield in the famous Ealing comedy. Sadly the tracks of the old Bristol and North Somerset Railway, where the film was shot, are now lifted, though the capers of Stanley Holloway, John Relph and Sid James live on in the iconography of those who fought the Beeching cuts for real. At Bathampton Junction we join Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s direct main line from London into Bath. Nowhere in Britain did the builder of a railway tread so sensitively on the approaches to a city. To take his track through Georgian Bath, Brunel built a variety of bridges, tunnels and viaducts, which he designed with even greater care than usual to ensure the greatest possible degree of harmony.

…

Judging by the deafening hiss of steam, this is no mirage. Schools Class No. 30926 Repton is preparing to depart at the head of a train of Pullman coaches along the preserved North Yorkshire Moors Railway, which forms a junction here. The eighteen-mile line to Pickering – once the direct route from Whitby to York and London until Beeching cut the service in 1965 – carries around 350,000 passengers a year, figures undreamt of in British Railways days. Some reckon it to be the busiest heritage railway in the world. There are other claims to fame too: the village of Goathland, one of the line’s intermediate stations, is the setting for the ITV television series Heartbeat, and not far from here it is possible to walk through the world’s first ever railway tunnel.

Bike Boom: The Unexpected Resurgence of Cycling

by

Carlton Reid

Published 14 Jun 2017

The “Middlesbrough Cycleway” scheme had ambitious intent (officials had consulted with the Bureau and with Claxton) and was to form a backbone of routes that could, in time, have led to a granular network, but only a few stretches were built in 1978 to the “innovatory” standard that had been envisaged, and the would-be network failed to attract cyclists in sufficient numbers for the trial to be rolled out further. FOLLOWING THE 1963 publication of Dr. Beeching’s report mentioned earlier, the motor-centric government of the day wielded the “Beeching Axe” and ripped out more than 5,000 miles of track from Britain’s historic and world-famous rail network. The steel rails may have been removed but the track beds remained and, in time, some of these rights-of-way were transformed into cycle trails. The UK’s current “National Cycle Network”—14,000 miles of traffic-free and quiet routes administered by a charity called Sustrans, founded by a visionary called John Grimshaw—sprang from one fifteen-mile stretch of former railway line.

…

Grimshaw wasn’t the first to lobby for the cycle-conversion of Britain’s (not at all) Permanent Way. That distinction goes to Michael Dower, a conservationist who, in 1992, became director general of Britain’s Countryside Commission. In 1963, writing in Architectural Review, Dower proposed that the track beds left after the Beeching cuts should form a national system of “greenways,” and that it would be cyclists who would be the greatest beneficiaries of them. The idea lay fallow until a 1970 government report picked up on the suggestion. Written by J. H. Appleton for, as it happens, the Countryside Commission, Disused Railways in the Countryside of England and Wales suggested that the track beds might also be used as refuse dumps, shooting ranges, nature reserves, linear campsites, running tracks, and—in Cambridgeshire—as an access road to a radio telescope.

On the Wrong Line: How Ideology and Incompetence Wrecked Britain's Railways

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 29 May 2005

Although the government rejected the report and chose not to renew Beeching’s tenure at the British Railways Board, it nevertheless proceeded with a series of closures that were to prove the most damaging to the railways in the long term. When they had been completed about 10,500 route miles had survived. Closures set out in the first Beeching Report, in fact, continued throughout the 1960s but slowed to a trickle by the mid-1970s and then dried up altogether by 1977. In fact, the attempt by BR to close major sections of the railway only ended in the 1980s with the unsuccessful and highly dishonest attempt to shut the Carlisle to Settle railway, now intensively used by freight and passenger trains and as a diversionary route.

…

The Act also denationalised road haulage, resulting in the sale of 24,000 lorries to small road hauliers who were able to compete, without any restriction on their charges, against BR which had its rates fixed by the government. The investment programme was hamstrung by the need to make interest payments to the former shareholders, which increased losses. As David Henshaw notes in his ground-breaking analysis of the Beeching cuts, ‘Whereas a private company would have paid little or no dividend in lean years, the return on British Transport Stock was guaranteed ... the railways were obliged to pay a fixed sum of around £40 million per year - even when they were making substantial losses.’⁵ That money would have been much better spent on improving the railways.

…

The chief casualties, which were either partially or wholly dismantled, were the Great Central which provided an alternative route from London to the Midlands and north-west, the Somerset & Dorset between Bath and Bournemouth, Oxford-Cambridge and the alternative Exeter-Plymouth line. The failure of those who carried out the Beeching cuts to consider the railway within a wider context seems, in retrospect, almost inexplicable. For example, at the very time that the Oxford-Cambridge line was being axed, the government was busily drawing up plans to turn Milton Keynes, within easy reach of the line, into the nation’s fastest growing city.

The Railways: Nation, Network and People

by

Simon Bradley

Published 23 Sep 2015

Barnum, Written by Himself (1888) Barringer: Tim Barringer, Men at Work: Art and Labour in Victorian Britain (2005) Barson: Susie Barson, ‘“A Little Grit and Ginger”’, in Holder and Parissien, 47–73 Baxter: Alan Baxter & Associates, Great Western Main Line Route Structures Gazetteer (2012) BDP: Birmingham Daily Post Bede: Cuthbert Bede, The Adventures of Mr Verdant Green (1853–7) Beebe: Lucius Beebe, Mansions on Rails: The Folklore of the Private Railway Car (1959) Beeching: The Reshaping of British Railways (The Beeching Report) (1963) Beer: Patricia Beer, Mrs Beer’s House (1968) Beerbohm 1: Max Beerbohm, And Even Now (1924) Beerbohm 2: Max Beerbohm, More (1898) Beerbohm 3: Max Beerbohm, Yet Again (1909) Belloc: Hilaire Belloc, On Nothing and Kindred Subjects (1908) Bennett: Arnold Bennett, ‘The Death of Simon Fuge’, in The Grim Smile of the Five Towns (1907) Betjeman 1: John Betjeman, First and Last Loves (1952) Betjeman 2: John Betjeman, Trains and Buttered Toast: Selected Radio Talks, ed.

…

Crumlin viaduct, Monmouthshire, built 1853–7. The valley below is threaded through with railways at multiple levels, all still in use in this photograph of 1961 20. Whitemoor marshalling yard explained, on a British Railways poster of c. 1950 21. The notorious closure map from Reshaping Britain’s Railways, alias the Beeching Report, 1963 22. Adlestrop station, Gloucestershire, c. 1905. The main building of 1853 is on the up platform (right), the platform shelter on the down platform, with the stationmaster’s house behind 23. The Great Western Hotel at Paddington station, opened 1854, in a Photochrom carriage picture of c. 1900 24.

…

There were about thirty of these in all, plain buildings of brick with hipped roofs, composed in a lopsided way: a two-storeyed residential side, attached to a single-storey section housing the public facilities. The standard provision of rooms – three bedrooms, parlour, kitchen – was the same as at the Birmingham, Wolverhampton & Dudley’s stations of the 1850s. The humorist and broadcaster Paul Jennings (1918–89), investigating the aftermath of the Beeching cuts in the late 1960s, found a retired stationmaster named Mr Purdie still living in his 1865-built home at Linton in Cambridgeshire. The station house had 14ft-high ceilings, an ‘elegant curved staircase’, and rusting rails as yet unlifted next to the empty platform. Following the same defunct route into Suffolk, Jennings visited the boarded-up and doomed Haverhill station, with its garden of ‘straggly rosebeds and vague asters’.

Winds of Change

by

Peter Hennessy

Published 27 Aug 2019

It was the year when young British adolescent males such as I, and great swathes of the population at large, realized that the Sixties were going to be different. When a nation’s mood music changes it is often a mixture of elegy and excitement – sometimes both in the same musical passage. The Beeching Report’s death sentence on steam and branch line – the most elegiac coupling the Industrial Revolution produced – tinged with a bit of anticipated pleasure about faster, cleaner services in the trade-off between romance and efficiency. But romance inspires deep affection; you can admire – but never love – efficiency.

…

Derek could never decide if this was a Reggie joke. ‘If it wasn’t,’ he said, with a beautiful smile, ‘I find it rather depressing.’ Maudling should have his place in the Conservative pantheon for that remark alone. Even if there is now little or no public memory of Maudling and the April 1963 Budget, the Beeching Report of March 1963 is not forgotten. As Matthew Engel wrote forty-six years later, after taking a nationwide ‘train journey to the soul of Britain’, 1963 was ‘the year when Britain finally and officially fell out of love with the railways … the name Beeching still has instant recognition to generations unborn in the 1960s … When I started telling people I was writing a book about Britain’s railways, several just shrieked “Oh, Beeching!”

…

Nevertheless, the ‘fact that the growth of new industries, more suited to road transport than rail, and the rising standard of living, expressed through increased car ownership, were important factors in the railways’ decline did not prevent that decline from being presented as indicative of a national problem’.87 Hence the talismanic property of the Beeching Report at the time and since. What was the philosophy behind the Beeching approach and the remedies he so confidently proposed? Beeching was well aware of the factors that had made rail the technological pacemaker, the engine of economic growth and the transformer of society in the nineteenth century from the 1840s onwards, though he rather lacked the poetry the railways so easily inspire: Railways are distinguished by the provision and maintenance of a specialised route system for their own exclusive use.

Small Men on the Wrong Side of History: The Decline, Fall and Unlikely Return of Conservatism

by

Ed West

Published 19 Mar 2020

Dad was right about what a menace cars are, usually the most dangerous and disruptive thing in a child’s life. Cars were supposed to represent freedom and independence, in this adolescent interpretation of conservatism in which only Lefties care about the environment. In Britain, it was the Tories who came up with the Beeching Axe that unnecessarily destroyed so many railway lines, a day that will live in infamy; Euston Station was demolished under a Tory government and St Pancras would have gone the same way if it wasn’t for John Betjeman’s campaign. As Peter Hitchens says, railways are beautiful, civilised and ordered, the very epitome of conservative values, and give us an appreciation of the landscape that cars will never manage.17 Also, as he doesn’t mention, you can drink beer on them too.

…

Norton, 1979). 25 http://anepigone.blogspot.com/2018/06/centrists-find-politics-boring-wish-it.html. 26 https://medium.com/@ryanfazio/politics-are-not-the-sum-of-a-person-378102f25334. 27 Burton Egbert Stevenson, The Macmillan Book of Proverbs, Maxims, and Famous Phrases (London: Macmillan, 1948) INDEX 28 Days Later (2002) 185 Abbott, Jack 121 abortion 166, 168, 202, 217, 241, 363 Abortion Act 217 Abramson, Lyn Yvonne 30 academia 7–8, 12, 16–17, 136–8, 319–26 activism 7, 316–17, 326 actors 186–7 Adam 33, 219 Adam, Corinna 18 Adams, Henry 90–1 Adams, John 281 Adams, Samuel 281, 331 Adorno, Theodor 135 The Authoritarian Personality 104–7, 143 Aesop’s Fables 260 Africa 15 Agamemnon 187 Agnew, Spiro 154 agnostics 216 agreeableness 108 Aids 125 Ailes, Roger 313, 346 al-Qaida 13, 125, 201 al-Sahaf, Mohammed Saeed 353 alcohol consumption 112–13, 133 Aldred, Ebenezer 61 Alexander, Scott 118, 315–16, 342–3 Allen, William 92 Allen, Woody 102 Alloy, Lauren 30 ‘Alt-Right’ 345, 347 Altemeyer, Bob 107, 333 American Beauty (1999) 106, 184 American Civil Liberties Union 201–2 American constitution 345 American independence 53, 55, 305 American National Election Studies 303 American Political Science Association 300 ‘American Religion’ 222 American Revolution 55, 280–1 Amnesty International 99, 201, 202, 212 ANC 16, 89, 189 ancien régime 178, 333, 358–9 Andrews, Helen 176 Anglicanism 13, 37, 64, 65, 202, 214, 222 Communion 220 High Church 50, 51 norms 79 supremacy 292 anti-apartheid movement 16 anti-Catholicism 232 anti-communism 22, 211 anti-humanitarianism 74 anti-social behaviour orders (ASBOs) 163 Antichrist 64 Antonia, Lady Fraser 42 apartheid 89, 174 Apollo 29 Aquinas, Thomas 326 Arabs 362 Arbuthnot, Norman 312 aristos 31 Arnold, Matthew 279 art, degenerate 98 Arts Council 197 Aryans 89 ASBOs see anti-social behaviour orders Ashley Madison website 107 Asquith, Robert 168 atheism 52–3, 214–16, 292, 294 see also New Atheism Athelstan, King 126 Athens 31 Atlantic magazine 341, 348, 366 Attenborough, David 195 Attlee, Clement 175 Attlee era 177 Augustine of Hippo 31–3, 35, 349 Augustine, St 110, 291 Auschwitz 98 authoritarian personality 104–7, 118, 334 authoritarianism 140, 148, 208, 262, 329–30, 333–4, 338, 350 autism 138 Ayres, Bill 236 Babeuf, François-Noël 60–1 baby boomers 44, 83, 131, 155 Bad Religion 102 bad-thinkers 144–5, 146, 150, 152 Baldwin, Alec 24 Balfour, Arthur 265 Bank of England 331 Bannon, Steven 152, 309, 347 Baptists 59, 145 barbarism 65, 66, 84 barbarians 12, 131 Bargh, John 115 Barlow, Joel 109 Baron-Cohen, Sacha 333 Barrès, Maurice 95 Basics, Baxter (Viz character) 86, 267 Bastille, storming of the 55, 59, 331 Batbie, Anselme 274 Batek 131 BBC 3, 149, 165, 186, 190–7, 265, 266, 313–14, 337 Beatles 166, 287 beatnik poetry 127 Becker, Ernest 115 Beeching Axe 285 Belgium 303 Belle Époque era 126, 175, 184–5 Benedict, St 373 Benedict XVI, Pope 218, 232, 233 Benn, Tony 18, 21, 42 Bentham, Jeremy 78, 92, 223–4 Berenger, Tom 110 Berlin 20–1, 23, 41–2 Berlin Wall 21, 22, 23, 86 Betjeman, John 285 Bevan, Nye 230 Beyoncé 24 Beyond the Fringe 191 Bible 50, 219, 229, 294 Bible Belt 228 Big Five personality traits 108–13, 137, 363 ‘Big Sort, The’ 295 Bill of Rights 305–6 biological determinism 139 birth control 364 birth rates 362–4 Bishop, Bill 295 Black Death 34–5 Black Lives Matter 338 Black Wednesday 154 Blackadder 331 Blair, Tony 21, 24, 79, 153, 156, 158–61, 163–4, 183, 189, 192, 213, 266–7, 270 Blair era 167, 203–4, 205, 281 ‘Blob, the’ 271 Bloom, Allan 98 Bloom, Paul 321 Bloomsbury 18 ‘blue wave’ 2006 274 Blumenberg, Hans 67 Boas, Franz 133–4 ‘Bobo’ (bohemian bourgeois) 244, 308 Bogart, Humphrey 24 Bolshevik Revolution 303 Bolshevism 226, 246 Borat 333 Bosnia 214 bourgeois 132, 246 bourgeoisie 9, 97, 127, 135 see also Ruling Class Boy Scouts 197 Bradbury, Malcolm 39 brain 116–17 Brando, Marlon 24, 341 Brazil 164 Brecht, Bertolt 186 Breitbart (website) 308, 309, 314, 315, 317–18, 347 Breitbart, Andrew 181, 308 Brennan, Mr 47 Brent, David 192 Brexit 4, 26–7, 103, 186, 195, 270, 346, 353–60, 365, 370 Brexit Referendum (2016) 3, 173, 222, 270, 275, 302, 354–5, 357, 359 Brief Encounter (1945) 162, 168 British Army 9 British Empire 57 British National Party 87 British Potato Council 203 ‘broken windows’ theory 69 Brook 241 Brooke, Heather 298 Brooker, Charlie 249 Brooks, Arthur 82, 191, 299 Who Really Cares 237 Brooks, David 244 ‘brotherhood of man’ 71, 100 Brown, Dan 213 Brown, Gordon 203, 265, 281 Brown era 203–4 Bruinvels, Peter 194 B’Stard, Alan 89 Buchanan, Pat 154–9, 313 Buckley, William F. 68, 295–6, 313 Bullingdon Club 267 Burke, Edmund 47, 53–5, 57–9, 61–3, 65, 66, 68, 70–2, 82, 89–90, 159, 163, 181, 190, 191, 198, 230, 274, 279, 280, 345, 365 Burleigh, Michael 88 Bush, George, Sr 86, 156 Bush, George W. 27, 201, 236, 248, 313 buttons 34–5 Byrne, Liam 266 C2DE social class 5 cable TV 311 Cafod 233 California 4, 320 Calvin, John (Jean) 48, 49, 293 Calvinism 45, 49, 64 Cambridge 49 Cambridge University 52, 55, 145, 151, 326, 348 Camden Labour Party 18 Cameron, David 237, 265, 266, 267, 270, 272, 359 Cameron faction 266, 270, 359 Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) 81 Campbell, Alistair 159–60 Camus, Albert 226 Canada 178, 201 capitalism 15, 64, 78, 93, 97, 280, 339 Caplan, Bryan 275 Capra, Frank 123 Captain America comics 237 Carlson, Tucker 365 Carlyle, Thomas 41, 75, 76 cars 285–6 Cash, Johnny 24 Cassandra 28–9, 62, 373 Catharism 254–5 Cathedral, the 202–3, 271 Catholic Church 48, 116, 212, 212–14, 217–18, 232, 233, 269, 333 Catechism 137 Catholic Emancipation Act 289 Catholic Herald (newspaper) 212, 213, 216, 219, 233, 241, 272, 307, 339 Catholicism 11–13, 33, 37, 41–3, 45, 49, 51–2, 54, 57, 62, 64, 75, 134–5, 142, 155, 158, 176, 199, 202, 211–13, 217–18, 222, 230–1, 241, 243, 272–3, 291–2, 294, 296, 339, 363 see also anti-Catholicism Cato Institute 324 Cavaliers 53, 57 Ceauşecu 46 censorship 148, 166, 188–9, 290, 331 Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) 61 ‘centrist dad’ 8 Chagnon, Napoleon 147 Change 3 Change UK 3 Channel 4 168, 232 charities 57, 199–202, 233, 237 Charles I 49, 55 Charles II 36, 37, 52 Charles-Roux, Fr Jean-Marie 210–11 Chartists 175 Chelsea FC 47 Chesterton, G.

The Story of Crossrail

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 5 Sep 2018

The other early London railway on the east–west axis was the North London Railway, which is described by the chronicler of its rather chequered history as having ‘precious little to do with north London or the needs of its citizens at all’.2 This is rather harsh but, in truth, reflects the fact that its original purpose was to provide access from the west to the economically important London docks and markets rather than serve local passengers. The railway was built in bits and pieces, and has had various incarnations, as well as the threat of closure, as recommended in the Beeching report of the early 1960s, hanging over it for several years. However, now it is an incredibly busy link between various north and northwestern suburbs and the eastern side of the City. The first section opened in 1850 between Bow Junction and Islington, and was soon extended to Camden and a junction with the London & North Western Railway, which owned the line (now the West Coast Main Line) in the west, and to Poplar Dock in the east.

…

The 1974 study scored a massive own goal by playing down the need for major new schemes: none of the ideas for extending London’s rail network could, it asserted, ‘be justified either on financial grounds or on a conventional social cost/benefit assessment of their transport effects’. Indeed, it is salutary to note that various sections of railway line in London were closed in the wake of the Beeching report of 1963. The North London line, which can be considered a cross-London line linking east and west, was actually slated for closure by Beeching and only saved after a lengthy campaign. Even then, it was run in a half-hearted way – first by British Rail and later under privatization in 1997. However, it would later become well patronized following considerable investment by Transport for London (TfL) in its track, stations and trains.

…

Abbey Wood 98, 99, 127, 154, 236, 242, 280 Abercrombie report (Greater London Plan) 25–6 Adonis, Lord 53, 126, 153–6, 158, 268, 280 agglomeration effects 38, 48, 152–3 Airport Junction 126 apprenticeships 276–7 archaeological finds, during Crossrail construction 199–202 articulated trains 240 artwork at Crossrail stations 220–2 ATP (Automatic Train Protection) systems 245–6, 247 Aventra trains 243–4 Aviation White Paper 100 AVIS (automatic vehicle inspection system) 242 BAA plc 125, 146, 149–50 Baker Street 123, 124 Bakerloo line 19–20, 31, 62, 73, 125 Bam Ferrovial Kier 229 Banks, Matthew 84 Barbara, St 188–9 Barbican Centre 122 Batty, Ed 195 Bechtel 166–7 Beeching report (1963) 5, 31 behavioural safety 170 benefit–cost ratios Crossrail project 83, 99, 153, 273 and the Chelsea–Hackney Line 70, 71 Kingston branch 105, 106 potential cross-London railways 91–2 transport megaprojects 45–54, 59 Bennett, Simon 143 Berkeley Homes 139, 149, 151, 154 Berryman, Keith 164–5 Bethlem Hospital cemetery, skeletons found at 201–2 bi-mode trains 126 Big Bang (financial services) 38, 40, 123 Binley, Brian 134 Binns, Chris 248, 254, 259, 264–5 Black, Mike 175, 186, 211–12 Blair, Tony 47, 109–10, 114, 146 Bombardier 128, 237, 239, 240–1, 243, 262 Bond Street 119–20, 128, 141 platforms 242 station construction 211, 221 tunnel construction 182–3, 187 Boyd-Carpenter, John 27 British Land 136, 141, 221 British Rail 74 A Cross-London Rail Link?

Are Trams Socialist?: Why Britain Has No Transport Policy

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 19 May 2016

The last throes of the ‘shut it down’ brigade was the attempt in the late 1980s to close the Settle–Carlisle railway on the spurious grounds that it was too expensive to maintain – a plan that was eventually killed off by a spirited campaign by local opponents and the arrival of Michael Portillo, later to become a true rail buff, at the Department of Transport in 1988. Faulkner and Austin summarize the period by suggesting that, while the build-up to the Beeching report is well known, what is remarkable – and shocking – is the discovery of just how determined the railway managers and civil servants of particularly the 1970s, and also the 1980s, were to reduce the size of the network with which they were entrusted, even after public opinion had turned against major closures, and politicians had wisely followed them.¹⁷ Again, this demonstrates the incoherence of government policies on the railways and on transport in general.

Driverless Cars: On a Road to Nowhere

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 18 Jan 2018

As transport expert Lynn Sloman summarized in 2006: In less than forty years, the car has become so intrinsic to the way we work, shop and spend our leisure time that it is almost inconceivable that we once managed without it.3 Other transport modes suffered. While the cuts resulting from the Beeching report are the most infamous, the wiping out of all the nation’s trolleybus schemes, all but one of its tramways (the one in Blackpool was saved), and many of its bus routes and suburban railways resulted in an ever-greater dependence on the car. Even parts of the London Underground, which saw a decline in passenger numbers, were being considered for closure.

The World's First Railway System: Enterprise, Competition, and Regulation on the Railway Network in Victorian Britain

by

Mark Casson

Published 14 Jul 2009

This illustrates a general pattern: that earlier routes generally Introduction and Summary 15 follow better alignments than later competing routes. Being Wrst in the Weld, their promoters had the widest choice, although there are some cases where the Wrst mover did not appear to choose wisely. A similar pattern was evident in the selection of the Beeching cuts of the 1960s: the lines that were Wrst to be closed were often those that were the last to be constructed, suggesting that they followed inferior alignments. The counterfactual trunk line system has a striking similarity to the modern motorway network. The lines from London to the north, for example, replicate the M1, M6, and M45 motorways, while the down-grading of the East Coast route is reXected in the relatively lowly status of the A1 road.

…

Some lost out to rival schemes, and others had to be scaled down because they were too ambitious. Perhaps the best example of his work was the York–DriYeld–Selby–Hull system in East Yorkshire, which had a four-way hub at Market Weighton. It was eventually built in full, although most of it was closed down during the Beeching cuts of the 1960s. The construction of integrated regional schemes was encouraged by the Railway Committee of the Board of Trade, although this did no good for the promoters of such schemes for, as we have seen, Parliamentary support for the Railway Committee soon evaporated. Some of these schemes were seen, rather cynically, as just an attempt to monopolize a region by courting favour with the Board of Trade.

…

The construction costs were sunk—they could not be recovered if the line was closed (apart from iron bridges, which were used for scrap). As the network expanded, some lines became obsolete, however—for example, the Birmingham and Derby Junction line from Whitacre to Hampton-in-Arden— but most were simply downgraded to local use rather than closed altogether. It was not until the Beeching cuts of the 1960s that wholesale closures occurred. Closures were so unusual that promoters could count on existing railways staying open—indeed, building a connection to a line would improve its chance of survival by bringing extra traYc to it. Path dependence can explain the alignments of many branch lines.

The Trains Now Departed: Sixteen Excursions Into the Lost Delights of Britain's Railways

by

Michael Williams

Published 6 May 2015

Where the old station once stood, buzzing with the ferment of Brummie commercial life, is a depressing multi-storey car park with a large sign reading, WELCOME TO THE SNOW HILL CAR PARK – BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL. Goodness, those councillors must be proud of themselves! The fate of the old Snow Hill is a case history of what happens when railways fall out of fashion. The 1963 Beeching Report, which promoted blinkered short-term economic demand above community need, ripped, as one commentator put it, the steel backbone out of the nation. More than two thousand stations were lost as a result. Bad enough, but in their misguided quest for modernity architects and planners inflicted equal damage on many of the stations that survived.

…

Unlike the Settle & Carlisle line – the only surviving British main-line rival to the Waverley route for scenic grandeur, luckily saved in 1989 after a long and hard-fought campaign – the official axe fell swiftly on the Edinburgh–Carlisle line as the mandarins in London, set on closure, outsmarted the locals. The first indication of doom came in the 1963 Beeching Report, where the railway was identified as one, in the anodyne phraseology of the time, from which it was ‘intended to withdraw passenger train services’. Beeching hammered an especially devastating nail into its coffin by describing the Waverley route as ‘the biggest money-loser in the British railway system’.

The Secret Life of Bletchley Park: The WWII Codebreaking Centre and the Men and Women Who Worked There

by

Sinclair McKay

Published 24 May 2010

Bletchley was both far enough away yet convenient enough to reach to make it an ideal location. And the town and surrounding villages were reckoned to have sufficient space for billeting all the codebreakers and translators. Bletchley Park itself was (and is) next to what is now referred to as the West Coast railway line. And in the days before Dr Beeching axed so much of the network, Bletchley station teemed with activity. To the west, the railways reached Oxford; to the east Cambridge. Meanwhile, anyone travelling from London, Birmingham, Lancashire or Glasgow could get to the town with ease. ‘Or relative ease,’ says Sheila Lawn, who became used to these long-distance hauls.

The Measure of Progress: Counting What Really Matters

by

Diane Coyle

Published 15 Apr 2025

Centre for Time Use Research. https://10.5255 /UKDA-SN-8741-4 Gershuny, J., Vega-R apun, M., and Lamote, J. (2020). Multinational time use study. Centre for Time Use Research, Institute of Education, University College London. 278 R efer e nce s Gibbons, S., Heblich, S., and Pinchbeck, T. (2018). The spatial impacts of a massive rail disinvestment program: The Beeching axe (CEP Discussion Papers dp1563). Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics. Giles, C. (2017, July 20). The benefits of repairing Britain’s broken retail prices index. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/b71eabae-6c7f-11e7-bfeb-33fe0c5b7eaa Goodridge, P., and Haskel, J. (2023).

Who Owns England?: How We Lost Our Green and Pleasant Land, and How to Take It Back

by

Guy Shrubsole

Published 1 May 2019

For three decades, the post-war Keynesian consensus held sway, with both major parties accepting the need for a high level of state intervention in the economy – and for the public sector to own an expanded estate in land. But increasingly the free-market right demanded the state be pared back. In 1963, under the auspices of a faltering Conservative administration, Dr Richard Beeching presented the findings of his government-commissioned review into the future of British railways. The ‘Beeching Axe’, as it was quickly termed, would fall sharply: a third of the existing railway network was to be closed. Despite a storm of protest from the rural communities affected, who rightly feared being marooned if they lost their local branch line, the government went along with his proposals. Beeching’s Axe proved short-sighted.

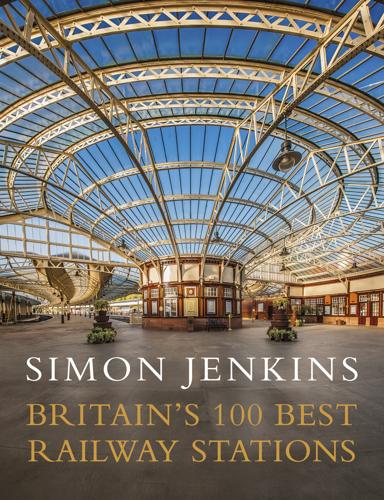

Britain's 100 Best Railway Stations

by

Simon Jenkins

Published 28 Jul 2017

The opportunity has also been taken for a more general railway exhibition, with the usual heritage clutter of a 1940s ticket office, luggage, signs and advertisements, and some rather sad bunting. None of this came easily. The handsome main station building was designed in 1846 by Sir William Tite for the Lancashire & Carlisle Railway. By the 1990s, a combination of Beeching cuts and British Rail neglect had reduced it to dereliction. Only Herculean efforts by the Carnforth Railway Trust brought it and the island platform back to life, and equipped a museum. The Carnforth Station Heritage Centre opened in 2003, with another film telling the story of this, more protracted, encounter.

Railways & the Raj: How the Age of Steam Transformed India

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 3 Oct 2018

Increasing concerns of the Government of India about the poor economic performance of the railways led, in 1936, to the establishment of yet another committee, this time to ‘examine the position of Indian state-owned railways’ (which by then were the majority), in order to suggest ways of improving profits and ‘at a reasonable and early date place railway finances on a sound and remunerative basis’.2 This was the type of enquiry that, incidentally, was paralleled across the world as railways everywhere faced increasing competition from road transport, which was wrecking the economic viability of many networks and placing ever-increasing financial burdens on the governments which owned them. The search for a ‘profitable’ or ‘economic’ railway was akin to seeking the Holy Grail, and discovered almost as rarely. India, in fact, was rather ahead of the game in that work on the infamous Beeching Report, which had a very similar remit in the UK, did not start until a quarter of a century later. The Indian Railway Enquiry Committee was chaired by Sir – of course – Ralph Wedgwood, who, reporting in 1937, found that the tendency to spend lavishly on new projects had surprisingly survived the Depression.

Fuller Memorandum

by

Stross, Charles

Published 14 Jan 2010

I make a right turn into a narrow path. It leads to a tranquil bicycle track, walled in beech and chestnut trees growing from the steep embankments to either side and sporadically illuminated by isolated lampposts. It used to be a railway line, decades ago, one of the many suburban services closed during the Beeching cuts--but it wasn't a commuter line. (I stumbled across it not long after we moved to this part of town, and it caught my attention enough to warrant some digging.) The Necropolis Service ran from behind Waterloo station to the huge Brookwood cemetery in Surrey; tickets were sold in two classes, one-way and return.

The Norm Chronicles

by

Michael Blastland

Published 14 Oct 2013

In Great Britain in 2010 there were 1,400 million journeys, up from 800 million 30 years ago: that’s 4 million journeys a day, totalling 54 billion kilometres over the year.3 This means that each one of 60 million people does on average 900 km (560 miles) a year, or around 10 miles a week, although this is one of those wonderfully misleading ‘averages’ that reflects the experience of nobody. Who travels 10 miles a week by train? There is huge variability, ranging from the dedicated commuter to someone in the countryside, cut off from trains by the Beeching cuts in the 1960s, to whom a train trip is a rare treat (or not). At the bottom of this distribution will be sufferers from ‘siderodromophobia’, the inordinate fear of trains, but most people feel a reassuring solidity and familiarity about train travel, as does Norm, usually. And with good reason – it is extraordinarily safe to be a passenger on a British train.

Commuter City: How the Railways Shaped London

by

David Wragg

Published 14 Apr 2010

Non-stop services between King’s Cross and Edinburgh reinstated. 1956 British Transport Commission plans most future electrification to be 25kv ac overhead. 1960 Inauguration of electric services between Euston and Manchester via Crewe on the London Midland Region, British Railways. 1963 Reshaping of British Railways, the ‘Beeching Report’ published. District Line train conducts trials with automatic driving equipment. 1964 Central Line conducts trials with automatic train operation using Woodford-Hainault shuttle. 1966 Electric service introduced from Euston to Manchester and Liverpool. 1974 Electric services inaugurated between Euston and Glasgow. 1991 Electric services inaugurated between King’s Cross and Edinburgh. 1994 British Rail restructured ready for privatisation.

Blood, Iron, and Gold: How the Railways Transformed the World

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 1 Mar 2010

Branches had started closing in many countries since the 1930s, but the pace accelerated greatly once cars started rolling on to the improved roads in the 1950s and 1960s in huge numbers. The inflexibility of the railways was proving a great burden, as stations and whole lines had to be shut. In Britain there was the infamous Beeching report published in 1963 which led to the closure of 4,000 miles of railway, a quarter of the total, and 3,000 stations, while in France most of the Departmental lines built after the clamouring of local interests in the 1870s were closed in the 1940 and 1950s. There were, however, some heroic attempts to resist the onslaught from cars, lorries and planes.

Fall Out: A Year of Political Mayhem

by

Tim Shipman

Published 30 Nov 2017

The meeting descended further into chaos as the push-button microphones were not working properly. ‘People couldn’t hear what other people were saying,’ the official said. Corbyn, who was supposed to be co-chairing the meeting, chipped in occasionally on obscure issues: ‘It was quite a bizarre afternoon.’ At one point the meeting even agreed to reverse the Beeching Report of the 1950s and rebuild local branch railway lines across the country, though that was never added to the manifesto. Tom Watson pushed for no major changes on the big spending commitments, only asking for a few pet policies to be included. ‘There was a sense that if Jeremy was going to lose, which they assumed, they should let him have his manifesto,’ a moderate in the room said.

A History of Modern Britain

by

Andrew Marr

Published 2 Jul 2009

Hired as the chairman of the railways, he conducted a ‘reshaping plan’ which proposed the closure of 2,361 stations and 5,000 miles of track – and that was just for starters. It was one of the most extreme liquidations in the history of British commerce, on a par with the collapse of the car industry a decade later, or the end of shipbuilding on the Clyde. Suspicions have been heard ever since that the Beeching cuts were politically motivated. They had been prepared for by a secret committee on which sat industrialists but no railway people. They came a few years after a savagely effective strike by two railway unions which had reminded Conservative ministers that while a country could be closed down if it was linked by trains, this was very much harder if it was a lorry and car economy.

Great Britain

by

David Else

and

Fionn Davenport

Published 2 Jan 2007

* * * STEAM RIDES AGAIN Wales’ narrow-gauge railways are testament to an industrial heyday of mining and quarrying. Using steam and diesel engines, these railways often crossed terrain that defied standard-gauge trains. The advent of steam and the rapid spread of the railway transformed 19th-century Britain, but 20th-century industrial decline and road-building left many lines defunct. The infamous Beeching report of 1963 closed dozens of rural branch lines. Five years later, British Rail fired up its last steam engine. Passionate steam enthusiasts formed a preservation group, buying and restoring old locomotives, rolling stock, disused lines and stations – a labour of love financed by offering rides to the public, often with old railway workers helping out.