Computer: A History of the Information Machine

by

Martin Campbell-Kelly

and

Nathan Ensmenger

Published 29 Jul 2013

What brought together these two groups, with such different perspectives, was the arrival of the first hobby computer, the Altair 8800. THE ALTAIR 8800 In January 1975 the first microprocessor-based computer, the Altair 8800, was announced on the front cover of Popular Electronics. The Altair 8800 is often described as the first personal computer. This was true only in the sense that its price was so low that it could be realistically bought by an individual. In every other sense the Altair 8800 was a traditional minicomputer. Indeed, the blurb on the front cover of Popular Electronics described it as exactly that: “Exclusive! Altair 8800. The most powerful minicomputer project ever presented—can be built for under $400.”

…

Almost all of these start-up companies consisted of two or three people—mostly computer hobbyists hoping to turn their pastime to profit. A few other entrepreneurs developed software for the Altair 8800. The most important of the early software entrepreneurs was Bill Gates, the co-founder of Microsoft. Although his ultimate financial success was extraordinary, his background was quite typical of a 1970s software nerd—a term that conjures up an image of a pale, male adolescent, lacking in social skills, programming by night and sleeping by day, oblivious to the wider world and the need to gain qualifications and build a career.

…

Although he had toyed with the idea of a general-purpose computer for some time, it was only when the more obvious calculator market faded away that he decided to take the gamble. The Altair 8800 was unprecedented and in no sense a “rational” product; it would appeal only to an electronics hobbyist of the most dedicated kind, and even that was not guaranteed. Despite its many shortcomings, the Altair 8800 was the grit around which the pearl of the personal-computer industry grew during the next two years. The limitations of the Altair 8800 created the opportunity for small-time entrepreneurs to develop “add-on” boards so that extra memory, conventional teletypes, and audiocassette recorders (for permanent data storage) could be added to the basic machine. Almost all of these start-up companies consisted of two or three people—mostly computer hobbyists hoping to turn their pastime to profit.

Fire in the Valley: The Birth and Death of the Personal Computer

by

Michael Swaine

and

Paul Freiberger

Published 19 Oct 2014

Roberts had other machines in mind, and each of them required new software. Meanwhile, Allen and Gates were putting increased effort into their own company, Microsoft. Throughout 1975, Gates, Allen, and Rick Wyland, who was hired to write 6800 BASIC, were branching out with their versions of BASIC, including developing versions for other companies. The relationship between Microsoft and MITS was becoming less clearly defined as the two companies grew. The fact that Bill Gates had yet to write the disk code for the Altair 8800 didn’t help matters, especially because Gates, on leave from Harvard, was considering returning to school. Paul Allen, in his role as MITS software director, nagged Gates about finishing the code.

…

And your home computer is kind of small, not too much memory. Maybe it’s a Mark-8 or an Altair 8800 with less than 4K bytes and a TV Typewriter for input and output. You would like to use it for homework, math recreations, and games like NUMBER, STARS, TRAP, HURKLE, SNARK, BAGELS. Consider, then, Tiny BASIC. “It’s Going to Happen!” Many of Dr. Dobb’s and PCC’s readers did more than consider Tiny BASIC. They took Allison’s program as a starting point and modified it, often creating a more capable language. Some of those early Tiny BASICs allowed large numbers of programmers to start using the microcomputers.

…

We’ll have two instruction sets to support. That just doubles our headaches.” Roberts prevailed. MITS did develop a 6800 machine, starting work on it late in 1975. Named the Altair 680b and attractively priced at $293, that computer was substantially different from the original Altair 8800. Components from the 8800 could not be used in the 680b, nor could the original Altair BASIC. When the new computer magazine Byte unveiled Southwest Tech’s 6800 computer in November 1975, the announcement was soon followed by MITS’s announcement of its 680b. Additional engineers were hired to work on the new design, and new employees were added.

The Singularity Is Nearer: When We Merge with AI

by

Ray Kurzweil

Published 25 Jun 2024

BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 90 Rick Porter, “TV Long View: Five Years of Network Ratings Declines in Context,” Hollywood Reporter, September 21, 2019, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/live-feed/five-years-network-ratings-declines-explained-1241524; Sapna Maheshwari and John Koblin, “Why Traditional TV Is in Trouble,” New York Times, May 13, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/13/business/media/television-advertising.html. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 91 For more on the transformative impact of the Altair 8800, see Jason Fitzpatrick, “The Computer That Changed Everything (Altair 8800),” Computerphile, YouTube video, May 15, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cwEmnfy2BhI; “The PC That Started Microsoft & Apple! (Altair 8800),” ColdFusion, YouTube video, March 18, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X5lpOskKF9I. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 92 US Census Bureau, Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1957 (Washington, DC: US Government Publishing Office, 1960), 491, https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Historical_Statistics_of_the_United_Stat/hyI1AAAAIAAJ; US Census Bureau, “Total Households (TTLHH)”; Steinberg, TV Facts, 142; Plunkett, Plunkett’s Entertainment & Media Industry Almanac 2006, 35; “Nielsen: 109.6 Million TV Households in the U.S.,” HispanicAd.com, July 30, 2004, http://hispanicad.com/blog/news-article/had/research/nielsen-1096-million-tv-households-us; “Late News,” AdAge, August 29, 2005, https://adage.com/article/late-news/late-news/104427; TVTechnology, “Nielsen Reports Slight Increase in TV Households,” TV Tech, August 28, 2006, https://www.tvtechnology.com/news/nielsen-reports-slight-increase-in-tv-households; Variety Staff, “TV Nation: 112.8 Million Strong,” Variety, August 23, 2007, https://variety.com/2007/tv/opinion/tv-nation-1128-22127/?

…

Performance source: Intel, Intellec 8 Reference Manual, rev. 1 (Santa Clara, CA: Intel, 1974), xxxxiii, https://archive.org/details/bitsavers_intelMCS8InceManualRev1Jun74_14022374. 1975 Altair 8800 Real price: $3,481.85 Computations per second: 500,000 Computations/second/dollar: 144 Price source: “MITS Altair 8800: Price List,” CTI Data Systems, July 1, 1975, http://vtda.org/docs/computing/DataSystems/MITS_Altair8800_PriceList01Jul75.pdf. Performance source: MITS, Altair 8800 Operator’s Manual (Albuquerque, NM: MITS, 1975), 21, 90, http://www.classiccmp.org/dunfield/altair/d/88opman.pdf. 1984 Apple Macintosh Real price: $7,243.62 Computations per second: 1,600,000 Computations/second/dollar: 221 Price source: Regis McKenna Public Relations, “Apple Introduces Macintosh Advanced Personal Computer,” press release, January 24, 1984, https://web.stanford.edu/dept/SUL/sites/mac/primary/docs/pr1.html.

…

Plunkett, Plunkett’s Entertainment & Media Industry Almanac 2006 (Houston, TX: Plunkett Research, 2006); Nielsen Company Unlike radio and television, which allow passive media consumption, computers open up wider possibilities because they are interactive. Personal computers started entering American homes during the 1970s, with machines such as the Kenbak-1, and in 1975 the wildly popular Altair 8800, which was sold in build-it-yourself kits.[92] By the end of the decade companies like Apple and Microsoft were transforming the market with user-friendly personal computers that ordinary people could learn to operate in an afternoon.[94] Apple’s famous 1984 Super Bowl commercial got the whole country talking about computers, and the proportion of US households with a computer nearly doubled within five years of its airing.[95] During that period people mostly used computers for things like word processing, data entry, and simple gaming.

From Airline Reservations to Sonic the Hedgehog: A History of the Software Industry

by

Martin Campbell-Kelly

Published 15 Jan 2003

They were established before the personal computer was a reality, at a time when the microcomputer was still perceived as either a dedicated controller or a low-cost minicomputer. Programming Languages Microsoft got its start developing the first programming languages for microcomputers.4 The first microprocessor-based computers were so simple that they did not require an operating system, but programmers did need a programming language to develop application programs. Bill Gates and Paul Allen filled this void in 1975 by providing a programming language for the MITS Altair 8800. Gates was born in 1955 into a well-to-do and socially accomplished Seattle family. He was educated in private schools.

…

Between this experience and the day Gates went off to Harvard, he and Allen were summer interns at the systems integrator TRW, further honing their programming skills.5 According to Gates and his many biographers, in his sophomore year at Harvard he saw the January 1975 issue of Practical Electronics, which had the Altair 8800 kit on the cover, and saw in a flash the opportunity to The Personal Computer Software Industry 205 become the leading vendor of programming languages for microcomputers.6 The Altair 8800 used the Intel 8008 microprocessor, with which Gates and Allen were already familiar. Working mainly at night, Gates and Allen wrote a BASIC compiler for the Altair during the next month. Although a considerable achievement, writing a BASIC translator was a task that a first-rate senior undergraduate at any good computer science school could have been expected to accomplish.

…

Although some professional software development practices diffused into microprocessor programming, much of the software technology was cobbled together or re-invented, an amateurish legacy that the personal computer software industry took several years to shake off. The first microprocessor-based computer (or certainly the first influential one) was the Altair 8800, manufactured by Micro Instrumentation Telemetry Systems (MITS). This machine was sold in kit form for assembly by computer hobbyists, and its appearance on the cover of Popular Electronics in January 1975 is perhaps the best-known event in the folk history of the personal computer. The cover reads: “Exclusive! Altair 8800. The most powerful minicomputer project ever presented—can be built for under $400.”3 The Altair computer was positioned in the market as a minicomputer.

Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution - 25th Anniversary Edition

by

Steven Levy

Published 18 May 2010

Roberts and his design helper Bill Yates wrote an article describing it. In January 1975, Solomon published the article, with the address of MITS, and the offer to sell a basic kit for $397. On the cover of that issue was a phonied-up picture of the Altair 8800, which was a blue box half the size of an air conditioner, with an enticing front panel loaded with tiny switches and two rows of red LEDs. (This front panel would be changed to an even spiffier variation, anchored by a chrome strip with the MITS logo and the legend “Altair 8800” in the variegated type font identified with computer readouts.) Those who read the article would discover that there were only 256 bytes (a “byte” is a unit of eight bits) of memory inside the machine, which came with no input or output devices; in other words, it was a computer with no built-in way of getting information to or from the world besides those switches in front, by which you could painstakingly feed information directly to the memory locations.

…

I believe their story—their vision, their intimacy with the machine itself, their experiences inside their peculiar world, and their sometimes dramatic, sometimes absurd “interfaces” with the outside world—is the real story of the computer revolution. Who’s Who: The Wizards and Their Machines Bob Albrecht. Founder of People’s Computer Company who took visceral pleasure in exposing youngsters to computers. Altair 8800. The pioneering microcomputer that galvanized hardware hackers. Building this kit made you learn hacking. Then you tried to figure out what to do with it. Apple II. Steve Wozniak’s friendly, flaky, good-looking computer, wildly successful and the spark and soul of a thriving industry. Atari 800.

…

You could put in a program only by flicking octal numbers into the computer by those tiny, finger-shredding switches, and you could see the answer to your problem only by interpreting the flickety-flock of the LED lights, which were also laid out in octal. Hell, what did it matter? It was a start. It was a computer. Around the People’s Computer Company, the announcement of the Altair 8800 was cause for celebration. Everybody had known about the attempts to get a system going around the less powerful Intel 8008 chip; the unofficial sister publication of PCC was the Micro-8 Newsletter, a byzantinely arranged document with microscopic type published by a teacher and 8008 freak in Lompoc, California.

The Road Ahead

by

Bill Gates

,

Nathan Myhrvold

and

Peter Rinearson

Published 15 Nov 1995

We're still late with projects sometimes but a lot less often than we would have been if we hadn't had those scary baby-sitters. Microsoft started out in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1975 because that's where MITS was located. MITS was the tiny company whose Altair 8800 personal-computer kit had been on the cover of Popular Electronics. We worked with it because it had been the first company to sell an inexpensive personal computer to the general public. By 1977, Apple, Commodore, and Radio Shack had also entered the business. We provided BASIC for most of the early personal computers. This was the crucial software ingredient at that time, because users wrote their own applications in BASIC rather than buying packaged applications.

…

January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics On the magazine's cover was a photograph of a very small computer, not much larger than a toaster oven. It had a name only slightly more dignified than Traf-O-Data: the Altair 8800 ("Altair" was a destination in a Star Trek episode). It was being sold for $397 as a kit. When it was assembled, it had no keyboard or display. It had sixteen address switches to direct commands and sixteen lights. You could get the little lights on the front panel to blink, but that was about all. Part of the problem was that the Altair 8800 lacked software. It couldn't be programmed, which made it more a novelty than a tool. What the Altair did have was an Intel 8080 microprocessor chip as its brain.

…

It would ensure that if Aunt Bessie invested in a set-top box, she could be confident it would work if she moved to another part of the country. Compatibility is important. It makes the consumer-electronics and personal-computer businesses thrive. When the PC industry was new, many machines came and went. The Altair 8800 was superseded by the Apple I. Then came the Apple II, the original IBM PC, the Apple Macintosh, IBM PC AT, 386 and 486 PCs, Power Macintoshes, and Pentium PCs. Each of these machines was somewhat compatible with the others. For instance, all were able to share plain-text files. But there was also a lot of incompatibility because each successive computer generation showcased fundamental breakthroughs the older systems didn't support.

Commodore: A Company on the Edge

by

Brian Bagnall

Published 13 Sep 2005

MOS Technology released the KIM-1 in 1975, the same year as the Altair 8800 computer. The Altair has come to be known as the first personal computer system in North America to herald the new microcomputer revolution. The differences between the KIM-1 and the Altair computer illustrate a split in design philosophy within the computer world. The KIM-1 was a single-board computer, with all components mounted on a single printed-circuit board. It had room for expansion, but there were no slots to insert adapter cards. This design philosophy reduced production costs and thus gave the KIM-1 a major pricing advantage over the Altair. The Altair 8800 used an Intel 8080 chip, which retailed for $360, but inventor Ed Roberts was able to negotiate the price down to $75 each in bulk.

…

“They had their little Gnome synthesizer, which was forty bucks. It wasn’t really a music instrument but it made some interesting sounds,” he says. Crude as the kits were, Yannes was learning valuable lessons about sound. After high school, Yannes attended Villanova University. The same year, MITS released the low-cost Altair 8800 microcomputer. “When the first Altair 8800 computer came out back in ’75, a friend of mine got one and that really got me into microcomputers,” he says. Yannes began devouring computer magazines. “Byte was a great magazine,” he recalls. “In the early days, it was pure hackers and hobbyists. It wasn’t a mainstream magazine but it was published like one.

…

Users had to develop their own software, and BASIC was the simplest path. To acquire BASIC, Commodore would make a deal with a small company called Micro-Soft. At the time, Micro-Soft did not own an operating system. Instead, it sold programming languages, principally its well-regarded version of BASIC. A young Bill Gates led the company. Some people mistakenly believe Gates invented BASIC, but John Kemeny and Thomas Kurtz invented it in 1964 at Dartmouth College. Peddle finds the misconception amusing. “I knew BASIC when Gates was still in * grammar school,” he laughs. Bill Gates and Paul Allen were still new to business.

Exploding the Phone: The Untold Story of the Teenagers and Outlaws Who Hacked Ma Bell

by

Phil Lapsley

Published 5 Feb 2013

Hacking on microcomputers had another advantage over hacking phones because you might actually be able to make money at it. The Altair 8800, for example, quickly caught the attention of a couple of undergraduates from Harvard University. Sensing a business opportunity, the duo proposed to write an interpreter for the BASIC computer language, something that would make the Altair far more useful. Upon seeing demo code from the pair, MITS took them up on the deal. The Harvard students—two kids named Bill Gates and Paul Allen—dropped out and started a company called Micro-Soft to pursue the opportunity. Intel’s 8080 found itself at the center of a competitive whirlpool of other companies’ microprocessor chips: the Motorola 6800, the MOS Technology 6502, the Zilog Z80.

…

Intel didn’t know it yet but that chip would be the thing that started the home computer revolution and would lead to Intel’s eventual domination of the microprocessor market. In January 1975 Popular Electronics, a geeky electronic hobbyist magazine, offered its readers an unbelievable chance to own their own slice of high-tech heaven. “Project Breakthrough!” the cover fairly shouted. “World’s First Minicomputer Kit to Rival Commercial Models . . . ‘Altair 8800.’” The cover’s photo showed a large metal box—blue, as it happened—about the size of three toasters, its nerd-sexy front panel festooned with dozens of tiny toggle switches and red LEDs. The computer had an Intel 8080 processor and 256 bytes of memory. It had no screen or keyboard, not even a teletype.

…

It came as a kit, consisting of empty circuit boards and bags full of electronic components you had to solder together. The price? A mere $397, mail-ordered from a company no one had ever heard of: MITS in Albuquerque, New Mexico. MITS’s phone began ringing off the hook. Within weeks thousands of orders were called in for the Altair 8800, more than four hundred in a single day. The Popular Electronics editor Les Solomon said later, “The only word which could come into mind was ‘magic.’ You buy the Altair, you have to build it, then you have to build other things to plug into it to make it work. You are a weird-type person. Because only weird-type people sit in kitchens and basements and places all hours of the night, soldering things to boards to make machines go flickety-flock.”

What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry

by

John Markoff

Published 1 Jan 2005

In the Whole Earth Catalog spirit, Tesler’s activist neighbor argued with him that people were eventually going to build their own computers. Tesler wasn’t so sure about that, but when he saw an advertisement in the local paper announcing the visit of a van to Palo Alto to show off the new MITS Altair 8800 computer kit, he thought he would go take a look. It had been only six months since Popular Electronics magazine had published a cover story on the Altair, a blue-edged metal box with lights and switches and not much else. Now the Albuquerque, New Mexico, company that manufactured it was sending a bus on tour around the country to demonstrate it.

…

The group had bought a handful of CDC 3800 computers that had been sold as surplus by the nearby Air Force Satellite Control Facility in Sunnyvale. At the time, the machines were the cheapest computing system you could possibly purchase. Their business plan positioned them to be a Tymshare competitor for one-third the price. When in early 1975 an Altair 8800 computer showed up at the PCC office, Allison carefully looked at its specifications, and what he discovered horrified him. “Two hundred fifty-six bytes of memory! You can’t do anything with this machine,” he said. He had been a consultant at Intel on the first microprocessor, the 4004, and so he had a clear sense of how much code was necessary to make the newer 8080 microprocessor do anything useful.

…

Although the company was planning on selling the machines by mail order, Terrell met with MITS’s founder Ed Roberts at the National Computer Conference in Anaheim, California, in 1975 and reached an agreement where he would promote Altairs in northern California and in return receive a commission on the machines sold in the region. MITS planned a nationwide bus tour for its Altair 8800, giving many people their first hands-on experience with a personal computer. The company had equipped a van as a mobile showcase, and Terrell reserved a conference room at Rickey’s Hyatt House, a Palo Alto hotel. The room held eighty people, but more than two hundred showed up in response to advertisements in local newspapers, including Larry Tesler, who would later unsuccessfully try to convince his colleagues that he had seen the future.

A People’s History of Computing in the United States

by

Joy Lisi Rankin

Albrecht and the People’s Computer Company were central to the Bay Area home computer endeavor; in fact, one of Albrecht’s People’s Computer Company instructors, Fred Moore, founded the Homebrew Computer Club.17 When MITS (Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems) publicized its Altair 8800 microcomputer in 1975, Albrecht and the People’s Computer Company recognized its “home computer” promise; a People’s Computer Company cover featured the Altair, but more importantly, the People’s Computer Company recognized the need for a BASIC for the Altair.18 In the issue immediately following its Altair- cover issue, the People’s Computer Company put out a call to its community of computing p eople. Under the heading “Build Your Own BASIC,” they proposed a pared-down language called “TINY BASIC,” and urged, “We’d like everyone interested to participate in the design. . . .

…

See Better Chance, A (ABC) program Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), 9, 190, 194–195, 201–205, 207, 225, 233; ARPANET and, 9, 107, 109, 135–137, 194–195, 205–207, 224–225; Licklider’s role in, 114; Multics and, 116; myt hology of, 107 African American. See Race Albrecht, Bob, 95, 102, 229, 234–236; role in spreading BASIC, 7, 68–69, 94–100, 105–106, 154 Allen, Paul, 2, 236 Allerton Park, Illinois, 174 ALOHA (network), 136–137 Altair 8800 microcomputer. See Microcomputers Alternative Futures Project. See under Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations (PLATO): politics and Anderson, Harlan, 100 Anderson, Wendell, 155 Apple Computers: Apple Macintosh, 189–191; Apple II microcomputer, 100, 237–240; BASIC in history of, 9, 105, 237–238; education and, 238–240; Steve Jobs and, 2, 9, 189–191, 237–239; myt hology of, 2, 190–192; The Oregon Trail on, 8–9, 139–140; personal com puters and, 105, 189, 191 ARPA.

…

US Gamer, April 19, 2017. http://w ww.usgamer.net/articles/t he-oral-history-of -oregon-t rail. Roberts, H. Edward, and William Yates. “ALTAIR 8800: The Most Powerf ul Minicomputer Project Ever Presented—Can Be Built for U nder $400.” Popular Electronics 7, no. 1 (January 1975): 33–38. Rome, Adam. The Genius of Earth Day: How a 1970 Teach-In Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation. New York: Hill and Wang, 2013. Rosegrant, Susan, and David Lampe. Route 128: Lessons from Boston’s High-Tech Community. New York: Basic Books, 1992. Rothman, Josh. “The Origins of ‘The Oregon Trail.’ ” Boston Globe, March 21, 2011. http://archive.boston.com / bostonglobe/ideas/ brainiac/2011/03/t he _origins_of_2.html.

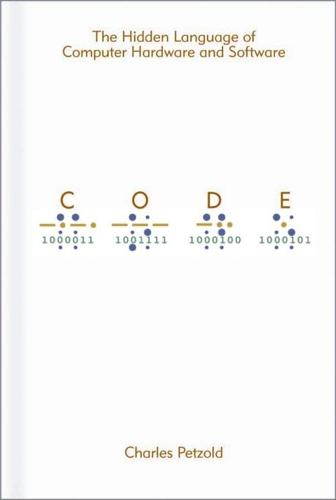

Code: The Hidden Language of Computer Hardware and Software

by

Charles Petzold

Published 28 Sep 1999

An interpreter, however, reads source code and executes it directly as it's reading it without creating an executable file. Interpreters are easier to write than compilers, but the execution time of the interpreted program tends to be slower than that of a compiled program. On home computers, BASIC got an early start when buddies Bill Gates (born 1955) and Paul Allen (born 1953) wrote a BASIC interpreter for the Altair 8800 in 1975 and jump-started their company, Microsoft Corporation. The Pascal programming language, which inherited much of its structure from ALGOL but included record handling from COBOL, was designed in the late 1960s by Swiss computer science professor Niklaus Wirth (born 1934).

…

Despite neither method being intrinsically "right," the difference does create an additional incompatibility problem when sharing information between systems based on little-endian and big-endian machines. What became of these two microprocessors? The 8080 was used in what some people have called the first personal computer but which is probably more accurately the first home computer. This is the Altair 8800, which appeared on the cover of the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics. When you look at the Altair 8800, the lights and switches on the front panel should seem familiar. This is the same type of primitive "control panel" interface that I proposed for the 64-KB RAM array in Chapter 16. The 8080 was followed by the Intel 8085 and, more significantly, by the Z-80 chip made by Zilog, a rival of Intel founded by former Intel employee Federico Faggin, who had done important work on the 4004.

…

Bibliography SPECIAL OFFER: Upgrade this ebook with O’Reilly Code: The Hidden Language of Computer Hardware and Software Charles Petzold Copyright © 2009 Charles Petzold (All) Microsoft Press books are available through booksellers and distributors worldwide. For further information about international editions, contact your local Microsoft Corporation office or contact Microsoft Press International directly at fax (425) 936-7329. Visit our Web site at mspress.microsoft.com. Send comments to mspinput@microsoft.com. Macintosh is a registered trademark of Apple Computer, Inc. Microsoft, MS-DOS, and Windows are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and/or other countries.

Dealers of Lightning

by

Michael A. Hiltzik

Published 27 Apr 2000

January 1: Xerox establishes the System Development Division, its most comprehensive attempt to commercialize PARC technology. More than five years later, SDD will launch its masterwork, the Xerox Star. January: The Altair 8800, a hobbyist’s personal computer sold as a mail-order kit, is featured on the cover of Popular Electronics, enthralling a generation of youthful technology buffs—among them, Bill Gates—with the possibilities of personal computing. February: PARC engineers demonstrate for their colleagues a graphical user interface for a personal computer, including icons and the first use of pop-up menus, that will develop into the Windows and Macintosh interfaces of today.

…

Lastly, I owe more than I can express to my wonderful sons, Andrew and David, who will inherit the world PARC made. Index Abramson, Norman, 186 Adobe Systems, 374, 396 Advanced Research Projects Agency. See ARPA Advanced Systems Division (ASD), 282–84, 357commercialization of Alto and, 278, 283–86 Alarm clock worm, 298 ALOHAnet, xiv, 186–87, 189 Alpha, 198 Altair 8800, xvi, 323, 333, 334 Alto, xv, xix–xxiv, xxvii, 141, 163, 167–77, 212, 224–25, 233, 261, 274, 303, 321, 324, 326, 330, 333, 357, 389, 395 Apple and, 335–36, 338–43asynchronous architecture and, 252–53 Bilbo and, 326 Bravo and, 194–95, 198–200, 208–9, 210, 283, 310 BravoX and, 283commercialization of, xvi, xxvii, 278, 282–88, 357, 392–93 Cookie Monster and, xv, xxii–xxiii, 81, 198, 231, 233cost of, 176diagnostic program for, 294display of, 171, 172–75, 176, 239 Draw and, 212 Elkind and, 168, 175, 278, 282–84 Ellenby and, 261–65, 268, 278, 283, 284–88 Ethernet and, 141, 176, 184–93, 212, 250, 251, 343 Futures Day and, 266, 271–72, 278, 280, 393 Goldman and, 278, 282–83 Gypsy and, 194–95, 207–10, 283interactivity and, xxi, 169, 170–71, 172–73 Kay and, xv, xxi, 167–68, 169, 170, 175, 220–28, 239, 283, 316 Kearns and, 286, 287, 288 Lampson and, xv, 141, 167–68, 171, 173–74, 175–76, 194, 195, 198, 206, see also Bravomanufacturing process and, 261–62 Markup and, 212 MAXC and, 175, 176 McCreight and, 141, 169, 176–77musical synthesizer and, 221 OfficeTalk and, 285 Penguin and, 285 POLOS and, 205–7, 210, 307at public school, 222–24, 314–15reset switch and, 289 SIL and, 212, 319 Simonyi and, 283, 284, 357 Smalltalk and, 220–21, 222–23software course for executives using, 274–75success of, 211–12 Taylor and, 3, 170–71, 205–6, 211text editor for, 194, 195, 198, see also Bravo Thacker and, xv, xix–xxiv, 4, 141, 163, 167–77, 174, 175, 212, 250–51, 289 Twang and, 221–22 Worm crashing, 289–90, 294–98 Xerox and, 285–88, 392, 393, 395 Xerox Model 850 versus, 264, 265, 274 Alto II, 262–63 Alto III, 263–65, 268, 350 850 word processor versus, 264, 265, 283 Ames Research Center, 197 Apple Computer, 329, 369–70 Apple II and, 332, 357, 358eMate and, 321 Goldberg and, 330, 335–36, 337, 338–40 Hall and, 334–35, 337, 338, 339, 340 Jobs and, xvi, xvii, xxiii, 329–45, 369–70, 389, 391 Lisa and, xvii, xviii, 337–38, 341–42, 343, 344 Macintosh and, xvi, xvii, xviii, xxiv, 329, 340, 341–42, 343, 344, 370, 389, 391, 395–96 Microsoft versus, xxv, 395–96size of, 392 Smalltalk and, 335–36, 338–43 Tesler and, 330, 333–34, 335, 336, 337, 338, 339, 340–41, 342, 344–45 VisiCalc and, 332 Wozniak and, xvi, 332 Architecture of information, 394 Archival memory, 123 Argus 700, 262 ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency), 11–12, 13, 14, 42–43, 118 ARPANET and, 43–46, 48, 78 Augmentation Research Center and, 64, 65 Berkeley 500 and, 78grants of, 61graphics and, 43, 231 Illiac IV and, 197 Licklider and, 11, 12–14, 18, 44 LINC and, 42 Mansfield Amendment and, 47–48 PDP—10 and, 98 Pup shared with, 291–93research conferences and, 16–17 Taylor and, 14–20, 42–43, 90, 146 University of Utah and, 90 Vietnam War and, 45–47 See also IPTO ARPANET, xiii, 48, 78, 171, 180, 184, 266 IMPs and, 118, 320as “internet,” 291–93 MAXC and, 115, 183–84 PDP—10 and, 98 POLOS Novas and, 189 Pup and, 291–93 Taylor and, 8, 43–45, 48 VLSI and, 310 Artificial intelligence, 91, 98 Bobrow and, 121, 237, 261 ASCII, 135, 139 “As We May Think” (Bush), 63 Asynchronous architecture, 252–53 Atkinson, Bill, 340, 342–43 Atlantic Richfield Company, 284 AT&T, 30, 53, 57, 391 Augmentation Research Center, 63–67 Aurora Systems, 241 Ballmer, Steve, 358–59 Bardeen, John, 57, 160 Barker, Ben, 180 Bates, Roger, 173 Bauer, Bob, 59 Beat the Dealer (Thorp), 146 Beaudelaire, Patrick, 212, 231 Becker, Joe, 369 Bell, Alexander Graham, xxiii Belleville, Bob, 250–52, 253, 369–70 Bendix LGP30 computer, 70 Berkeley Computer Corporation, xiv, 68–69, 73–79, 106, 107–8, 197, 230 500 computer and, 76, 78, 109 Genie and, 69, 70, 72–73 1 computer and, 74–76 Biegelsen, David, 52–53, 58, 152 “Biggerism,” Thacker and, xx, 75 Bilbo, 326 Billboard worm, 298 BitBlt, Ingalls and, xv, 226–28, 342 Bitmapped screen Alto and, 173–74, 272 Star and, 362, 364 Blue books, 291 Bobrow, Daniel G., 261, 376, 399artificial intelligence and, 121, 237, 261 Bolt, Beranek & Newman and, 121, 280, 301 Elkind and, 280, 281, 282 Boeing Corporation, 284 Boggs, David R., 178–79, 399 Alto and, 294 Ethernet and, 141, 176, 187–92 Futures Day and, 267, 272 Novas and, 188 Worm and, 290–91 Bolt, Beranek & Newman, 76, 118, 119, 120, 121, 180, 265–66, 280, 301, 320 Boolean logic, 109, 304 “Bose Conspiracy,” 152–53 Box Named Joe, A, 222 Brand, Stewart Rolling Stone and, xv, 155–62, 204, 223 Whole Earth Catalog and, 157 Bravo, 208–9, 210, 227, 283, 310, 373 Lampson and, 194, 195, 198, 199, 201 Simonyi and, xv, 194–95, 198–201 BravoX, 283–84, 285, 364 Simonyi and, 283, 357, 360 Brittain, William, 57 Brooks, Frederick, 74, 76 Brown, John Seely, 302, 386, 399 Brunner, John, 295–96, 297, 298–99 Brushes, Alto and, 174 Building 34, 140 Burroughs, 24, 89, 101 Bush, Vannevar, 63–64, 67, 122 Buvall, Bill, 64 C++, xiv Campbell, Sandy, 381–82 “Capability Investment Proposal” (Ellenby), 285, 286–87, 288 Card, Stuart, 302 Carlson, Chester, 22, 35, 130, 350, 393 Carnegie-Mellon, 43 Carter, Jimmy, 283–84 Carter, Shelby H., 285–86, 287, 363 CD-ROM, 55, 123 Cedar, 325 Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), 336 Character generator.

…

See PARC Papert, Seymour, 218 LOGO and, 91–92, 164, 222 Parallel processing, Worm and, 289–90, 293–99 Paramount Pictures, Futures Day and, 267 PARC (Palo Alto Research Center), xivambiance of, 277–78 Bardeen saving, 57, 160collegiality at, 57–59, 150–53at Coyote Hill Road, xv, xvi, 254–55creative method of, 107dedication of, 53–54division of, 356, 372, 374–75evaluation of Xerox’s role with, xxvi–xxvii, 55–57, 60–61, 95–96, 373, 389–98future and, 122–24 Goldman’s proposal for, xiii, 29–32governing principle of, xxii, xxviinternal conflicts in, 372–73invention at, xxiv–xxvlost decade and, 55–57, 394money earned for Xerox by, xxvi, 128, 144 name of, 30, 38office of the future and, 123, 165, 233, 235, 237opening of, 40research agenda of, 55, 386site of, 31, 32, 37–40 PARC Universal Packet. See Pup Pattern sensitivity, Intel 1103 memory chip and, 114 PDP-1, 71, 72 PDP-10, 98, 99, 100, 103, 104–6, 108, 121, 124, see also MAXC PDP-11, 248 Peeker, 298 Pendery, Don, 121–22, 143 Pendery Papers, 122–24 Penguin, 285 Personal computer, xxiii, 95, 391 Altair 8800 and, xvi, 323, 333, 334 Dorado and, xvii, 318–21, 322, 324–26, 327 Dynabook and, xiii, 94, 163–67, 175, 211, 216, 321, 327, 336 IBM PC and, xviii, xxiv, 212, 360, 368–69, 370, 389, 391, 395 Kay and, 81, 89, 93–94, 95 Minicom and, 163–67 Taylor and, 5, 8, 49 See also Alto; Lisa; Macintosh Photoconductor fatigue, 130–31 Piaget, Jean, 91 Piece tables, 199 Pimlico, 271 Pirtle, Mel, 72, 73–74, 76, 77, 78, 197 Pixar, 240 Pixels, xxii, 164, 165 POLOS (PARC On-line Office System), 166, 170, 173, 176, 307 Alto and, 205–7, 210, 307 English and, 307 Fairbairn and, 307 Mott and, 203–5, 206 Novas and, 184–85, 188, 189, 202, 206as obsolete, 206–7, 210 Tesler and, 201–3 Pop-up menus, xvi, 209 BitBlt and, xv, 227–28 Portable computer.

Track Changes

by

Matthew G. Kirschenbaum

Published 1 May 2016

While the story about Xerox’s failure to effectively commercialize those ideas is well known, the sequence of events behind the actual systems and their development is complex, involving multiple generations of hardware and software.15 The computer that Jobs famously saw demonstrated at PARC in 1979 (by none other than Larry Tesler, who had by then been working there for the past six years) was called the Alto, which had been prototyped as early as 1973.16 The Xerox Alto is not to be confused with the Altair 8800, the machine that famously graced the cover of Popular Electronics in January 1975 and (so the story goes) motivated Bill Gates to leave Harvard. (The Altair communicated its output to users, not on a screen or even on paper, but through gnomic blinking LED lights, the epitome of the “digital black-magic box” mentioned by the Homebrew Computer Club.)17 Unlike the Altair, then, the Alto was a fully functioning graphical computer system, years ahead of its time.

…

So last, I am grateful to everyone who has taken the time to tell me about their first word processor. INDEX Abe, Kōbō, 194, 221 Ackerman, Patricia Freed, 143–144, 153, 297n16 Adams, Douglas, 111–112, 221, 289n87, 321n71 Altair 8800, 51, 123, 291n17 Amazon.com, 88; Kindle, 27, 84. See also E-readers American Management Association (AMA), 34–36, 41, 145–148, 153, 161, 182 Analog (magazine), 39, 94, 109, 110 Anderson, Kevin J., 222 Anthony, Piers, 20, 25, 207, 260n38 Anzaldúa, Gloria Evangelina, 22, 262n59 Apple, 43, 114, 127; AppleTalk, 201; BASIC, xi, 105, 106, 107; HyperCard, 10, 24, 257n35, 263n67; Imagewriter, 195; iPad 4, 18, 23, 307n3; Lisa, 142; MacBook Air, 76; Macintosh, xiv, 112, 127, 185, 195–202, 235, 236; Macintosh IIe, x, xi, 115; Macintosh IIsi, 185; Macintosh SE, 201; Macintosh SE/30, 202, 320n61; MacPaint, 295; Mac Performa, 215; Mac PowerBook, 26, 75, 184–185; MacWrite, xiv, 40, 201 Apricot (computer), 111, 274n84 Aquinas, Thomas, 252n5 Archives: computers and, 8, 33, 158, 198, 200, 209, 210, 213–215, 239 Archives, Inc., 67–68 ARPANET, 69, 96 ASCII, 94, 100, 120, 272n75, 307n52 Ashbery, John, 75, 76 Asimov, Isaac, 56–59, 62, 71, 92–95, 98, 141, 143, 238, 275n13, 275n14, 282n2 Atari, 140, 282n2 Atwood, Margaret, 16, 19, 161, 208, 302n85 Austen, Jane, 7, 8, 191, 192, 194 Auster, Paul, 8–9, 13, 20–22, 27, 261n48, 285n31 Austerityware, 237–238 Automation: and archives, 239; and efficiency, 29, 40, 47, 55, 99, 159, 182; fears surrounding, 37–39, 43, 44, 192, 268n27, 270n57; and the workplace, 147–153, 176; and writing, 38, 39, 44, 49, 144, 159, 192, 290n107 Avant-garde, 25, 72, 160, 173, 179, 192, 196, 202 Babbage, Charles, 14, 115 Bad Sector (users’ group), 64–66, 219 Baen, Jim, 102, 283n17, 287n50 Baker, Nicholson, 32, 87, 285n31 Baker, Russell, 35 Baker Josephs, Kelly, 313n65 BAKUP (users’ group), 64, 66 Ballard, J.

…

Disks themselves were literally floppy—5¼- or 8-inch black squares that actually waggled up and down; the smaller 3½-inch floppies (which were not floppy but rigid) did not yet exist. Hard drives existed, but were seen only rarely on the sorts of machines most consumers would buy. Time magazine was still more than a year away from declaring the personal computer its “Machine of the Year.” Popular Electronics had featured the Altair 8800—usually considered the world’s first microcomputer—on its cover in January 1975, but in 1981 was still a year away from renaming itself Computers and Electronics. Tron and War Games had not yet made it to movie theaters, and William Gibson had not yet coined the term “cyberspace” in his fiction.

The Innovators: How a Group of Inventors, Hackers, Geniuses and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution

by

Walter Isaacson

Published 6 Oct 2014

According to Solomon, his daughter, a Star Trek junkie, suggested it be named after the star that the spaceship Enterprise was visiting that night, Altair. And so the first real, working personal computer for home consumers was named the Altair 8800.113 “The era of the computer in every home—a favorite topic among science-fiction writers—has arrived!” the lede of the Popular Electronics story exclaimed.114 For the first time, a workable and affordable computer was being marketed to the general public. “To my mind,” Bill Gates would later declare, “the Altair is the first thing that deserves to be called a personal computer.”115 The day that issue of Popular Electronics hit the newsstands, orders started pouring in.

…

Levy, Hackers, 187. 112. Levy, Hackers, 187. 113. Les Solomon, “Solomon’s Memory,” Atari Archives, http://www.atariarchives.org/deli/solomons_memory.php; Levy, Hackers, 189 and passim; Mims, “The Altair Story.” 114. H. Edward Roberts and William Yates, “Altair 8800 Minicomputer,” Popular Electronics, Jan. 1975. 115. Author’s interview with Bill Gates. 116. Michael Riordan and Lillian Hoddeson, “Crystal Fire,” IEEE SCS News, Spring 2007, adapted from Crystal Fire (Norton, 1977). 117. Author’s interviews with Lee Felsenstein, Steve Wozniak, Steve Jobs, and Bob Albrecht. This section also draws from the accounts of the Homebrew Computer Club origins in Wozniak, iWoz (Norton, 2006); Markoff, What the Dormouse Said, 4493 and passim; Levy, Hackers, 201 and passim; Freiberger and Swaine, Fire in the Valley, 109 and passim; Steve Wozniak, “Homebrew and How the Apple Came to Be,” http://www.atariarchives.org/deli/homebrew_and_how_the_apple.php; the Homebrew archives exhibit at the Computer History Museum; the Homebrew newsletter archives, http://www.digibarn.com/collections/newsletters/homebrew/; Bob Lash, “Memoir of a Homebrew Computer Club Member,” http://www.bambi.net/bob/homebrew.html. 118.

…

Torvalds: © Jim Sugar/Corbis Berners-Lee: CERN Andreessen: © Louie Psihoyos/Corbis Case: Courtesy of Steve Case Hall: Courtesy of Justin Hall Kasparov: Associated Press Brin and Page: Associated Press Williams: Courtesy of Ev Williams Wales: Terry Foote via Wikimedia Commons IBM Watson: Ben Hider/Getty Images INDEX Abbate, Janet, ref1 Aberdeen Proving Ground, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6 Abound, ref1 Acid Tests, ref1 acoustic delay line, ref1 “Action Office” console, ref1 Ada, Countess of Lovelace, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 in affair with tutor, ref1, ref2 algorithms worked out by, ref1 Analytical Engine business plan of, ref1 Analytical Engine potential seen by, ref1 Babbage requested to be tutor of, ref1 Babbage’s first meeting with, ref1 at Babbage’s salons, ref1, ref2 Bernoulli numbers computed by, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 on “Combining Faculty,” ref1 on connection between poetry and analysis, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8 as doubtful about thinking machines, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9 on general purpose machines, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7 illnesses of, ref1, ref2, ref3 marriage of, ref1 “Notes” of, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 opiates taken by, ref1, ref2, ref3 programming explored by, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7 on subroutines, ref1, ref2 temperament and mood swings of, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6 tutored in math, ref1, ref2, ref3 Ada (programming language), ref1 Adafruit Industries, ref1n Adams, John, ref1 Adams, Samuel, ref1 Adams, Sherman, ref1 Adcock, Willis, ref1 advertising, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 Age of Wonder, The (Holmes), ref1 Aiken, Howard, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9, ref10 Difference Engine of, ref1, ref2, ref3 and operation of Mark I, ref1 stubborness of, ref1 Aiken Lab, ref1, ref2, ref3 Air Force, U.S., ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6 Albert, Prince Consort, ref1 Albrecht, Bob, ref1, ref2 Alcorn, Al, ref1, ref2 algebra, ref1, ref2 algorithms, ref1 Allen, Paul, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9, ref10 BASIC for Altair designed by, ref1, ref2 8008 language written by, ref1 electronic grid work of, ref1 Gates’s disputes with, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 in Lakeside Programming Group, ref1 PDP-10 work of, ref1, ref2 “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace” (Brautigan), ref1, ref2 ALOHAnet, ref1 Alpert, Dick, ref1 Altair, ref1, ref2, ref3 Altair 8800, ref1, ref2, ref3 BASIC program for, ref1, ref2, ref3 exhibition of, ref1 AltaVista, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac, ref1 American Physical Society, ref1 American Research and Development Corporation (ARDC), ref1 America Online (AOL), ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6 Ames Research Center, ref1 Ampex, ref1, ref2 analog, ref1 digital vs., ref1, ref2, ref3 Analytical Engine, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9, ref10 Differences Engine vs., ref1 Lovelace’s business plan for, ref1 Lovelace’s views on potential of, ref1 Menabrea’s notes on, ref1 punch cards and, ref1, ref2 as reprogrammable, ref1 Analytical Society, ref1 “Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine, The” (Brin and Page), ref1 Anderson, Sean, ref1 Andreessen, Marc, ref1, ref2, ref3 Android, ref1 A-O system, ref1 Apollo Guide Computer, ref1 Apollo program, ref1, ref2, ref3 Apple, ref1n, ref2, ref3n, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9 creativity of, ref1 headquarters of, ref1, ref2 Jobs ousted from, ref1, ref2 lawsuits of, ref1 Microsoft’s contract with, ref1 patents of, ref1 Apple I, ref1 Apple II, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 AppleLink, ref1 Apple Writer, ref1 Applied Minds, ref1 Aristotle, ref1 Armstrong, Neil, ref1 ARPA, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8 funding for, ref1 ARPANET, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9, ref10, ref11, ref12 bids on minicomputers for, ref1 connected to Internet, ref1 distributed network of, ref1, ref2 first four nodes of, ref1, ref2 military defense and, ref1 start of, ref1 ARPANET News, ref1 arsenic, ref1 artificial intelligence, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8 human-machine interaction and, ref1, ref2 as mirage, ref1, ref2, ref3 video games and, ref1 Artificial Intelligence Lab, ref1 Asimov, Isaac, ref1 assembly code, ref1 assembly line, ref1, ref2 Association for Computing Machinery, ref1n “As We May Think” (Bush), ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8 Atanasoff, John Vincent, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8 influence of, ref1, ref2 Atanasoff, Lura, ref1 Atanasoff-Berry computer, ref1 AT&T, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6 Atari, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6 founding of, ref1 Atari 800, ref1 Atkinson, Bill, ref1, ref2 Atlantic, ref1, ref2 atom bomb, ref1, ref2 Atomic Energy Commission, ref1 atomic power, ref1 ATS-3 satellite, ref1 Augmentation Research Center, ref1, ref2, ref3 augmented intelligence, ref1 “Augmenting Human Intellect” (Engelbart), ref1, ref2 Auletta, Ken, ref1 Autobiography (Franklin), ref1 automata, ref1 Automatic Computing Engine (ACE), ref1, ref2 automobile industry, ref1 Aydelotte, Frank, ref1 Baba, Neem Karoli, ref1 Babbage, Charles, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9, ref10, ref11, ref12, ref13, ref14, ref15 Ada’s first meeting with, ref1 government attack published by, ref1 limits of Analytical Engine mistaken by, ref1 logarithm machine considered by, ref1, ref2 Lovelace given credit by, ref1 Lovelace’s Analytic Engine business plan and, ref1 programming as conceptual leap of, ref1 weekly salons of, ref1, ref2, ref3 Babbage, Henry, ref1 BackRub, ref1 Baer, Ralph, ref1 Baidu, ref1 ballistic missiles, ref1, ref2 Ballmer, Steve, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 Bally Midway, ref1, ref2, ref3 Baran, Paul, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8 packet-switching suggested by, ref1 Bardeen, John, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7 in dispute with Shockley, ref1, ref2, ref3 Nobel Prize won by, ref1 photovoltaic effect studied by, ref1 solid-state studied by, ref1 surface states studied by, ref1 Barger, John, ref1 Bartik, Jean Jennings, see Jennings, Jean BASIC, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9 for Altair, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 batch processing, ref1 BBC, ref1 Beatles, ref1 Bechtolsheim, Andy, ref1 Beckman, Arnold, ref1, ref2, ref3 Beckman Instruments, ref1 Bell, Alexander Graham, ref1, ref2, ref3 Bell & Howell, ref1 Bell Labs, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9, ref10, ref11, ref12, ref13, ref14, ref15, ref16, ref17, ref18, ref19, ref20, ref21 founding of, ref1 Murray Hill headquarters of, ref1 patents licensed by, ref1 solid-state physics at, ref1, ref2, ref3 transistor invented at, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 Bell System, ref1 Benkler, Yochai, ref1, ref2 Berkeley Barb, ref1, ref2 Berners-Lee, Tim, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7 background of, ref1 and creation of browsers, ref1 hypertext created by, ref1 and micropayments, ref1 religious views of, ref1 Bernoulli, Jacob, ref1n Bernoulli numbers, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 Berry, Clifford, ref1, ref2 Beyer, Kurt, ref1, ref2 Bezos, Jeff, ref1 audaciousness celebrated by, ref1 Bhatnagar, Ranjit, ref1 Big Brother and the Holding Company, ref1, ref2 Bilas, Frances, ref1, ref2 Bilton, Nick, ref1 Bina, Eric, ref1, ref2 binary, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 in code, ref1 in German codes, ref1 on Z1, ref1 Bitcoin, ref1n bitmapping, ref1 Bletchley Park, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7 Blitzer, Wolf, ref1 Bloch, Richard, ref1, ref2, ref3 Blogger, ref1, ref2 Blogger Pro, ref1 blogs, ref1 coining of term, ref1 McCarthy’s predictions of, ref1 Blue, Al, ref1 Blue Box, ref1, ref2 Board of Patent Interferences, ref1 Bohr, Niels, ref1 Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN), ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9 bombe, ref1 BOMIS, ref1, ref2 Bonneville Power Administration, ref1 Boole, George, ref1, ref2 Boolean algebra, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 Borgia, Cesare, ref1 boron, ref1 Bowers, Ann, ref1 brains, ref1, ref2 Braiterman, Andy, ref1, ref2 Braithwaite, Richard, ref1 Brand, Lois, ref1 Brand, Stewart, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9, ref10 Brattain, Walter, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7 in dispute with Shockley, ref1, ref2, ref3 Nobel Prize won by, ref1 photovoltaic effect studied by, ref1 solid-state studied by, ref1 in World War II, ref1, ref2 Brautigan, Richard, ref1, ref2, ref3 Breakout, ref1, ref2 Bricklin, Dan, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 Brilliant, Larry, ref1, ref2 Brin, Sergey, ref1, ref2, ref3 Google founded by, ref1, ref2, ref3 PageRank and, ref1 personality of, ref1 Bristow, Steve, ref1 British Association for the Advancement of Science, ref1 Brookhaven National Lab, ref1, ref2 Brown, Ralph, ref1 browsers, ref1 bugs, ref1 Bulletin Board System, ref1 Burks, Arthur, ref1 “Burning Chrome” (Gibson), ref1 Burns, James MacGregor, ref1 Bush, Vannevar, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9, ref10, ref11, ref12, ref13, ref14, ref15, ref16, ref17 background of, ref1 computers augmenting human intelligence foreseen by, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8, ref9, ref10, ref11 linear model of innovation and, ref1 personal computer envisioned by, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4 technology promoted by, ref1, ref2 Bushnell, Nolan, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6 venture capital raised by, ref1 Busicom, ref1 Byrds, ref1 Byron, George Gordon, Lord, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 incest of, ref1, ref2 Luddites defended by, ref1, ref2, ref3 portrait of, ref1, ref2, ref3 Byron, Lady (Annabella Milbanke), ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 Cailliau, Robert, ref1, ref2 Caine Mutiny, The, ref1 calculating machines: of Leibniz, ref1 of Pascal, ref1, ref2 calculators, pocket, ref1, ref2, ref3 calculus, ref1, ref2 notation of, ref1 California, University of, at Santa Barbara, ref1 Call, Charles, ref1 Caltech, ref1, ref2 CamelCase, ref1 capacitors, ref1 CapitalLetters, ref1 Carey, Frank, ref1 Carlyle, Thomas, ref1 Cary, Frank, ref1 Case, Dan, ref1, ref2 Case, Steve, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 background of, ref1 Cathedral and the Bazaar, The (Raymond), ref1, ref2 cathode-ray tubs, ref1 Catmull, Ed, ref1 Caufield, Frank, ref1, ref2 CBS, ref1, ref2, ref3 CB Simulator, ref1 Census Bureau, U.S., ref1, ref2 Centralab, ref1 central processing unit, ref1 Cerf, Sigrid, ref1 Cerf, Vint, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6, ref7, ref8 background of, ref1 internet created by, ref1 nuclear attack simulated by, ref1 CERN, ref1, ref2 Cézanne, Paul, ref1 Cheatham, Thomas, ref1 Cheriton, David, ref1 Chicago Area Computer Hobbyists’ Exchange, ref1 Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (Byron), ref1, ref2 Chinese Room, ref1, ref2 Christensen, Clay, ref1 Christensen, Ward, ref1 Church, Alonzo, ref1, ref2 circuit switching, ref1 Cisco, ref1 Clark, Dave, ref1 Clark, Jim, ref1 Clark, Wes, ref1, ref2, ref3 Clinton, Bill, ref1n Clippinger, Richard, ref1 COBOL, ref1, ref2n, ref3, ref4, ref5, ref6 Cold War, ref1 Collingwood, Charles, ref1 Colossus, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 as special-purpose machine, ref1 Command and Control Research, ref1 Commodore, ref1 Community Memory, ref1, ref2, ref3 Complex Number Calculator, ref1, ref2, ref3 Compton, Karl, ref1 CompuServe, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4, ref5 computer, ref1, ref2 debate over, ref1, ref2, ref3 “Computer as a Communication Device, The” (Licklider and Taylor), ref1 Computer Center Corporation (C-Cubed), ref1 Computer Quiz, ref1 Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, ref1 computers (female calculators), ref1, ref2 Computer Space, ref1, ref2, ref3 “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” (Turing), ref1 Conant, James Bryant, ref1, ref2 condensers, ref1, ref2 conditional branching, ref1 Congregationalist, ref1 Congress, U.S., ref1 Congress of Italian Scientists, ref1 Constitution, U.S., ref1n content sharing, ref1 Control Video Corporation (CVC), ref1, ref2 copper, ref1 Coupling, J.

Gambling Man

by

Lionel Barber

Published 3 Oct 2024

‘It was exactly that same feeling. I was tingling all over and warm tears were rolling down my face.’ Masa’s account – repeated endlessly in interviews and biographies – is almost identical to Bill Gates’s story of being shown a copy of Popular Electronics magazine in January 1975. Gates, then a second-year student at Harvard, was so blown away reading about the Altair 8800 microprocessor that he dropped out and co-founded his own company – Microsoft – in Albuquerque, New Mexico. ‘I was genuinely moved,’ Gates recalled. ‘In my opinion, Popular Electronics completely changed the relationship between humans and computers.’14 Whether Masa’s story is true or a copycat experience is less important, perhaps, than the fact that the young Japanese student was following Den Fujita’s advice and fast developing an interest in technology.

…

/Softbank (2005), 174–7; Goldman Sachs exits, 171; managing of SoftBank’s stake in, 306, 307, 308, 309, 322; Masa’s deal (1999), 142–4, 147, 236, 262, 278; Masa’s investment in, 4, 144, 147, 169–71, 174–7, 262, 278, 296, 306–7, 314; Masa’s long-term faith in, 170–71, 176, 315; psychological impact on Masa, 147, 278; SoftBank as overly dependent on, 177, 321, 322; Taobao launched (May 2003), 169–71 Alta Vista, 101 Altman, Sam, 327, 330, 335 Amazon, 101, 132, 307, 312, 329 Ambani, Anil, 182 America Online (AOL), 2, 102 Anderson, James, 253 Anderson Mori & Tomotsune (law firm), 311, 314 Andreessen Horowitz, 282, 283 Ansett Airlines, 113 Apax (private equity firm), 241 Apple Computer, 35, 48, 56, 89, 178, 190, 307, 312; Apple II, 72, 73; and ARM chips, 244, 245, 247, 330; Foxconn manufactures iPhone, 268, 286; iPad, 192; iPhone, 4, 190–91, 192–3, 227–8, 268, 286; Jobs’ return to, 102–3, 190; Think Different advertising campaign (1997), 189; and Vision Fund, 266, 289 Aramco oil company, 260, 264 Argentina, 295 Ariburnu, Dalinc, 259 Arimori, Takashi, Net Bubble (2000), 163 ARM Holdings, 242, 244–55, 259, 265–6, 323, 329–31 Arora, Nikesh, 232, 233–5, 236–43, 259, 287, 288–9 artificial intelligence (AI): AGI (artificial generative intelligence), 328–32; and ARM Holdings, 265, 323, 329–31; ‘first wave’ of AI-related companies, 328–9; Masa’s current plans, 327–31, 334–5; Masa’s embrace of/optimism about, 203, 210, 211, 265, 319, 323, 327–35; Masa’s new chip-making venture, 329–30, 334–5; next generation of computer graphics chips, 304–5, 308, 323, 329–31, 334–5; and Nvidia, 304–5, 305*, 323, 330–31; and surveillance/security, 265–6; today’s dark debates about, 331, 332 Asahi Shimbun newspaper, 56, 64, 149–50 Asahi Weekly magazine, 56, 149 ASCII (Japanese computer magazine), 65 Asian Cup football tournament, 175 AstraZeneca, 248, 249 AT&T, 75, 165, 192, 224, 225–6, 227 BAE Systems, 249 Baillie Gifford, 253 Bain Capital, 288 Baker III, James A., 70 Bartz, Carol, 232, 233 baseball, 188, 196–7 Al-Bassam, Nizar, 259–60, 262, 263–4, 269 Bear Stearns, 193–4 Beijing, 142–3, 175–6, 226, 324 Bell Laboratories, 74, 75 Benchmark Capital (VC company), 283, 301 Berkeley, University of California, 27, 36–9, 40–43, 55–6, 101, 102 Berkshire Hathaway, 273–4, 296–7 Bezos, Jeff, 307 Bhanji, Nabeel, 296, 301 Bit Valley Association, 1, 3 BlackRock, 290 Blackstone, 167, 268, 288 Blair, Tony, 294 Blavatnik, Len, 239–40 Blodget, Henry, 132 Bonfield, Sir Peter, 156–7 Boston Dynamics, 275 Braun, Markus, 305–6 Brightstar, 227–8 Brin, Sergey, 232–3, 235 British Telecom (BT), 156–7, 172, 235 BSkyB, 112, 116, 117 Buffett, Warren, 84–5, 273–4, 296–7 Businessland, 83 Buzzfeed, 237–8 Cadbury, 248 California, 27–8, 33–4, 101–2, 108–9, 133, 174–5; academic-entrepreneur model on university campuses, 27–8, 37, 101–2; Berkeley, University of California, 27, 36–9, 40–43, 55–6, 101, 102; Fairmont Hotel, San Jose, 140, 148; Masa’s education in, 30–34, 35, 36–9, 40–47 see also Oakland, California; Silicon Valley, California Cameron, David, 250, 251, 294 Canon, 43 Carlson, Chuck, 41, 45 Casio, 43 Cayman Islands, 308 Centricus, 259–60 Cerberus, 185 Chambers, John, 162 Chambers, Stuart, 245–7, 249–50, 252 ChatGPT, 327, 328 Cheng Wei, 273 China: (B2C) consumer market in, 169–71, 174–7; ByteDance, 284, 321, 328; China Mobile, 225, 235; Communist party, 5–6, 144, 175, 314, 321–2; confrontation with Trump, 320; Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, 144; Didi Chuxing ride-hailing app, 273, 284, 321, 328; geopolitical impact of Xi Jinping, 314, 321–2, 324; and the internet, 4, 142–4, 145–6, 147, 158, 168–71, 174–7, 284, 328; iPhone manufactured in, 286; Japanese invasion of (1937), 11; Masa as largest foreign investor, 4–5; Masa as minor celebrity in, 142–3; Masa’s first visit to (1995), 144–5; relations with Japan, 175–6; SoftBank’s venture capital fund in, 142–3; stimulus programme (2009), 201; and Taiwan, 17; Tencent, 307; Tsinghua University in Beijing, 102*; UTStarcom, 145–6, 158; World Trade Organization entry, 147 Chudnofsky, Jason, 95 Cisco Japan, 89–90, 103, 162 Cisco Systems, 89–90, 137, 139, 143, 162 Claridge’s hotel, 261 Claure, Marcelo, 227–31, 240, 242, 287–8, 289, 316–17, 318, 323–4 Clearwire, 231 CNET, 164 Colao, Vittorio, 180 Collins, Tim, 171–4 Columbia Pictures, 80, 101, 119–20 Comcast, 240 Compuserve, 102 computer technology: AI-driven computer graphics chips, 304–5, 308, 323, 329–31, 334–5; Altair 8800 microprocessor, 33; ARM chip, 244–5, 247–8, 253, 265–6, 308, 323, 329–30; chips as scarce and most crucial resource, 331; Comdex (trade fair in Las Vegas), 72, 89, 93, 94–6, 97, 124, 189, 267–8; electronic speech translators, 37, 39–45, 48, 114, 171*; Fujita’s advice to Masa, 26; innovation in 1970s California, 27–8, 33–4, 37, 101–2; Intel 4004 chip, 35; Intel 8080 microprocessor, 33; ‘internet of things’, 244, 245, 246, 253, 254–5; invention of integrated circuit, 27; Masa at Berkeley, 36–9; memory board manufacturers, 108–11; Microsoft-Novell rivalry, 76–7; Mozer’s talking calculator, 37; networking hardware/software, 77, 89–90, 143; Novell’s ‘netware’, 76–7; personal computer revolution, 49, 51, 53–4, 74–5; Unix operating system, 75 see also artificial intelligence (AI); internet; mobile internet; software technology; telecoms Computer Weekly, 78 Confucian thought, 119, 146, 147 Costner, Kevin, 129–30 Cotsakos, Christos, 134 Coupang, 236, 319 Covid-19 pandemic, 298–302, 303, 306, 312, 314, 315, 320, 326*, 328 credit rating agencies, 184–5, 229, 306 Credit Suisse, 306, 319 Cringely, Robert X., Accidental Empires, 163 Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank, 55, 61, 63, 98 Daoist thought, 146 DataNet (magazine publishing company), 69 Davos, World Economic Forum, 2, 147, 148, 167, 294 Deadwood, South Dakota, 129–30 Democratic Party of Japan, 220 Deng, Wendi, 120–21 Deng Xiaoping, 144 Deutsche Bank, 124, 181–4, 185, 235, 237, 259, 283, 304 Doko, Toshio, 119 Dolotta, Ted, 74–8, 91, 103 Domaine de la Romanee-Conti (DRC) wine, 239, 246, 333 DoorDash, 283, 328 dot-com bubble (1998-2000), 132–6, 138–41, 147–8, 190; AOL-Time Warner merger (2000), 2; bursting of, 4, 145, 148–51, 156, 284, 328; eVentures fund, 121; Masa’s investments during, 133–6, 138–41, 143–4, 148, 284, 328; Masa’s reinvention after crash, 4–5, 156, 201; SoftBank’s stock peaks (February 2000), 3–4; Velfarre disco event (February 2000), 1–3, 148 Dream-Works, 236 Drucker, Peter, 52 E-Access, 160, 225 EachNet, 168, 169 EADS (aerospace company), 249 East, Warren, 245 eBay, 168–9, 174, 176 economy, global: China as ‘last frontier’, 144; Covid disruption, 314; financial crisis (2008), 83, 193–6, 201; hyper-globalization, 4, 5; impact of Russo-Ukraine war, 324; inflation in post-Covid period, 320, 324; and Japan’s economic miracle, 21, 48, 178; Masa and the digital revolution, 1–5, 49, 121, 137–8, 157, 211, 244; new cold war protectionism, 5; Plaza Accord (22 September 1985), 69–70, 80; second oil price shock (1979), 48–9; World Economic Forum (Davos), 2, 147, 148, 167, 294 see also dot-com bubble (1998-2000) Edison, Thomas, 158 Eisner, Michael, 107* Elliott Management (Hedge fund), 295–8, 299–301, 302, 308, 313 Ellison, Larry, 140, 189–90, 235 entrepreneurship: of Sheldon Adelson, 93–5; emerging Chinese class, 142–3; of Den Fujita, 24–6, 33; Japanese resistance to change, 48, 83–4; Masa’s early money-making ventures in USA, 33, 36–7, 39–47, 171*; Masa’s limitless attitude to risk, 5, 54–5, 57, 133–4, 140–41, 159–61, 210–11, 273, 309–13, 331; of Mitsunori, 18–19, 20, 21–4, 54–5; as not consistent with perfection, 6; Sasaki as Silicon Valley mentor, 35; start-up ecosystem in Silicon Valley, 101–7, 127; story of Steve Jobs, 190; ‘term sheet’ convention in Silicon Valley, 284–5; and US universities in 1970s, 27–8, 37, 101–2 see also venture capital (VC) Ericsson, 188 Esrey, William, 172–4 E-trade, 134–5, 138, 139, 162, 164 E-Trade Japan, 138, 164 Excite, 101, 105 EY (accountants), 305, 306 Ezersky, Peter, 91, 93 Facebook (Meta), 236, 259, 297, 303, 307, 329 Fairchild Semiconductor, 101–2 Al-Falih, Khalid, 264 Feld, Brad, 133 Fentress, Chad, 314 film industry, 107*, 119, 129–30, 235, 236; Columbia Pictures, 80, 101, 119–20 Filo, David, 101, 102, 103–4, 105 financial/business sector: Black Monday stock market crash (1987), 108; Buffett on leverage, 297; buy-backs, 296, 297, 298–9, 300–301, 302; call options, 312; collapse of Lehman Brothers (15 September 2008), 194, 196, 197, 235; ‘conglomerate discount’, 295, 296, 308; Covid-19 emergency measures by central banks, 301–2, 312, 316; Dai-Ichi Kangyo loan, 55, 61; financial instruments, 181, 184, 235, 282, 312; hyper-globalization, 4, 5; IRR metrics, 127–8, 308–9; Japanese banks, 61, 80–85, 92, 95–6, 97–9, 136–7, 138–9, 300, 334; Japan’s ‘Little Bang’ (1993), 97–8; Japan’s ultra-low-to-negative interest rate policy, 98–9, 100; Jasdaq over-the-counter market, 76, 85, 90, 131; leveraged buy-outs, 127–8, 184–5, 191, 196, 240, 247, 274, 275, 300; “Man’s pride” (trust) in Japan, 87, 170–71, 195–6, 273; Masa’s use of opaque corporate structures, 123, 125–6, 127–9, 130, 296; Nasdaq stock market, New York, 2, 4, 138, 148, 149; old-school culture in Japan, 64, 82, 89–90, 119, 158, 195–6; preferred equity, 282; private equity, 5, 92, 134–5, 167, 171–4, 180, 185, 241, 288; related-party-transactions/off-balance-sheet dealings, 122–3, 125–6, 127–9, 130, 138, 139; securitization, 181, 185, 187, 193–4, 306; Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE), 64, 76, 85, 90, 128, 131; Wall Street banks, 91, 92, 159, 193–4, 205, 248; ‘whole company securitization’, 185 see also dot-com bubble (1998-2000); venture capital (VC) Fink, Larry, 290, 291 Fisher, Ron, 103, 108–9, 129, 140–41, 219, 276; and Arora, 234, 235–6; at Interactive Systems, 75, 77–8; joins Softbank, 87, 99–100; leaves SoftBank, 317–18; loyalty to Masa, 133–4, 325; on Masa-Jobs relationship, 193; on Masa’s 30-Year Vision speech, 211–12; and Northstar, 309, 311; and sales of SoftBank assets, 158, 162 Flowers, J.

…

But he saw down the end of the line, how the technology would be adapted,’ Gates remembered. ‘He believed these markets would grow and he always wanted to do more. He was very flamboyant, energetic, and understood western things and there were very, very few people in Japan who could do that.’15 On 16 June 1983, Bill Gates and Nishi unveiled their plans for standardization under a system called MSX. From now on, software written in Microsoft’s BASIC programming language could run on computers produced by any hardware manufacturer that paid the relevant licence fee, and built the PCs to agreed specifications. Five days later, Masa, still only 25, rose from his hospital bed and held a press conference, flanked by his own manufacturing allies led by Sharp and Sord, which had the second and fourth largest market share in the Japanese PC market.

All the Money in the World

by

Peter W. Bernstein

Published 17 Dec 2008

A number of companies that later propelled their founders to great riches were, in fact, born in a dorm room. Even though Microsoft founders Bill Gates and Paul Allen both dropped out of college, the seed for what became Microsoft was planted while Gates was still at Harvard. Allen had already dropped out of Washington State University to take a programming job in Boston. The story goes that while visiting Gates, Allen saw a Popular Electronics story describing the MITS Altair 8800, the “World’s First Minicomputer Kit to Rival Commercial Models,” which prompted the duo to talk themselves into dropping everything and starting a company.

…

Now, for the first time, the potential existed for the personal computer to have a role in the business world. Gates and his friend Paul Allen4 had already established a reputation for themselves as whiz kids in high-tech circles when they developed software to run the first personal computer, the Altair 8800, in 1975. Several years later the two were making a comfortable living with Microsoft, their tiny, Seattle-based software company. Now, suddenly, the industry’s Goliath wanted to do business—but only according to IBM’s script, and with Gates only playing a minor role in the corporation’s plans. Gates arrived with Ballmer5 in Miami, Florida, on the red-eye from the West Coast; according to some accounts, they hadn’t slept in thirty-six hours.

…

Rockefeller did23 that Bill Gates hasn’t done is use dynamite against his competitors!” he complained.*5 It was a stinging remark, but many others shared his view. Bill Gates had “an incredible desire to win and to beat other people,” ex–Microsoft executive Jean Richardson recalled for a PBS documentary, Triumph of the Nerds. “At Microsoft, the whole idea was that we would put people under.” “My job,”24 said one of Gates’s executives in 1991, just as Microsoft Office was being launched, “is to get a fair share of the software applications market. And to me, that’s 100 percent.” Microsoft, of course, escaped Standard Oil’s fate.

Outliers

by

Malcolm Gladwell

Published 29 May 2017

But they also were given an extraordinary opportu nity, in the same way that hockey and soccer players born in January, February, and March are given an extraordinary opportunity.'1" Now let's do the same kind of analysis for people like Bill Joy and Bill Gates. If you talk to veterans of Silicon Valley, they'll tell you that the most important date in the history of the personal computer revolution was January 1975. That was when the magazine Popular Electronics ran a cover story on an extraordinary machine called the Altair 8800. The Altair cost $397. It was a do-it-yourself contraption that you could assemble at home. The headline on the story read: “PROJECT BREAKTHROUGH! World's First Minicomputer Kit to Rival Commercial Models.”

…

Ideally, you want to be twenty or twenty-one, which is to say, born in 1954 or 1955. There is an easy way to test this theory. When was Bill Gates born? Bill Gates: October 28,1955 That's the perfect birth date! Gates is the hockey player born on January 1. Gates's best friend at Lakeside was Paul Allen. He also hung out in the computer room with Gates and shared those long evenings at ISI and C-Cubed. Allen went on to found Microsoft with Bill Gates. When was Paul Allen born? Paul Allen: January 21, 1953 The third-richest man at Microsoft is the one who has been running the company on a day-to-day basis since 2000, one of the most respected executives in the software world, Steve Ballmer.

…

After graduating from Berkeley, Joy cofounded the Silicon Valley firm Sun Microsystems, which was one of the most critical players in the computer revolution. There he rewrote another computer languageJavaand his legend grew still further. Among Silicon Valley insiders, Joy is spoken of with as much awe as someone like Bill Gates of Microsoft. He is sometimes called the Edison of the Internet. As the Yale computer scientist David Gelernter says, "Bill Joy is one of the most influential people in the modern history of computing/' The story of Bill Joy's genius has been told many times, and the lesson is always the same. Here was a world that was the purest of meritocracies.

The New Geography of Jobs

by

Enrico Moretti

Published 21 May 2012

But on a rainy morning in early January 1979, something happened that changed the history of the city. A Tale of Two Cities Everyone now associates Microsoft with Seattle. However, in the early part of its life, Microsoft was located a world away. In fact, the company was founded in 1975 in Albuquerque, New Mexico. That year it had one product, one client, and three employees. The client was MITS, an Albuquerque hardware firm that was making a successful home computer kit called the Altair 8800; the product used BASIC software to operate the kit. In the following months and years, Microsoft prospered in New Mexico. Its future looked so promising that by the end of 1975 one of the two founders, an intense, preppy-looking twenty-year-old named Bill Gates, took a leave of absence from Harvard to join Paul Allen, the other founder, who was already in Albuquerque.

…

Of course this does not mean that everyone should go to college. The history of technology is dotted with brilliant innovators who dropped out. If you have a groundbreaking idea, it obviously makes sense to pursue your dream. When Bill Gates decided that working for Microsoft was more important than finishing Harvard, it was a turning point for the software industry. If he had finished college first, Microsoft might not have become the dominant force it later became, and Gates himself would have been several billions poorer today. If Mark Zuckerberg had stayed in college, his nemeses, the Winklevoss twins, might have developed a social networking site before him.

…

Its future looked so promising that by the end of 1975 one of the two founders, an intense, preppy-looking twenty-year-old named Bill Gates, took a leave of absence from Harvard to join Paul Allen, the other founder, who was already in Albuquerque. The business took off, and Gates never returned to Harvard to finish his degree. Not that he needed it. Sales were growing exponentially, and by 1978 they had already exceeded the $1 million mark and thirteen employees worked for Microsoft. But the founders were growing increasingly restless, and eventually they decided to relocate. This was not a business decision. Gates and Allen were both from Seattle, and they both wanted to go back to the place where they had grown up.

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World

by

Malcolm Harris

Published 14 Feb 2023

Homebrew’s Steve Dompier was so excited and curious that, after MITS returned half his $4,000 check because the company didn’t actually stock all the products in its catalog yet, he flew to Albuquerque in person, then reported back to the club on the ramshackle state of the New Mexico operation.27 In June of 1975, the MITS caravan literally rolled into Palo Alto, setting up shop at the Hyatt Rickey’s on El Camino.x The road-show Altair was hooked up to a teletype, with which it could load the Micro-Soft BASIC (punched on a roll of paper tape) and then interact with users. If you loaded the BASIC and typed “2+2,” it printed “4.” Without the language, the Altair 8800 was merely a box of switches. The Homebrew Computer Club needed it, but they weren’t about to pay hundreds of dollars each to be able to use the machine they already bought, and perhaps more important, they weren’t going to wait until Altair was ready to start using it. Someone snagged one of the BASIC paper rolls from the MITS box and handed it off to club member Dan Sokol, who worked at the Fairchild spin-off Signetics, where he had access to a PDP-11 with a high-speed tape-copying machine.

…

When the prototype Roberts sent got lost in the mail, Solomon decided to trust the blueprints. Someone—accounts differ—named it the Altair, after the destination planet in an episode of Star Trek.iii In January of 1975, the personal computer era kicked into gear with the glossy national announcement of the Altair 8800, and mail orders, complete with hundreds and even thousands of dollars, poured into Albuquerque.2 Artisanal hippie entrepreneurialism was in the NorCal air, and not just among the early computer hackers: A three-man team led by two Stanford students started selling a beginner’s guide to “juggling for the complete klutz” in late-1970s Palo Alto, adding a second book on the official stoner sport Hacky Sack in 1982.

…

Sokol showed up at the next Homebrew meeting with 50 copies, asking everyone who took one to come back with two to share. The pirated BASIC spread quickly through the small microcomputer community, pushing the platform’s software development forward and enraging Gates, whose company was supposed to be pulling in a royalty for every copy in use. Then 20 years old, Trey Gates was going by the more relatable name Bill, and when he wrote his famous “Open Letter to Hobbyists,” he signed it as “Bill Gates,” without the “III” but with “General Partner, Micro-Soft.” He complained that, though their BASIC was popular, only 10 percent of Altair owners had purchased a licensed copy.

The Everything Blueprint: The Microchip Design That Changed the World

by

James Ashton

Published 11 May 2023

Both had dropped out of college. Jobs worked as a technician at Atari and Wozniak designed calculators at Hewlett-Packard. Both attended the Homebrew Computer Club, where enthusiasts shared ideas about the latest electronics. At the first Homebrew meeting, in a garage in Menlo Park, California, Wozniak enthused over the new Altair 8800 computer and took home a sheet listing the technical specifications for the 8008 microprocessor, inspired to build his own free-standing computer. Altair used Intel’s 8080 chip, but it ‘cost almost more than my monthly rent’ and it was hard for an individual to buy in small quantities.16 Motorola’s 6800, discounted to $40 for HP employees, was Wozniak’s best option, until he heard about a new microprocessor that would be introduced at the Wescon event.

…

In Boston, he introduced himself on stage as ‘chairman and CEO of Pixar’, the animations studio he was officially running, adding that he was one of several people ‘pulling together to help Apple get healthy again’.4 The most surprising addition to that group of supporters was Bill Gates, the chief executive of Microsoft with whom Apple had been battling for years over patent infringements. The pair had not only resolved their legal differences, but Apple would make Microsoft’s Internet Explorer the default browser for the Macintosh. More importantly in the short term, Jobs had negotiated for Microsoft to make a $150m stock investment in his cash-strapped company. ‘We’re pleased to be supporting Apple,’ Gates said, looming over the stage via satellite link to alternate cheers and boos.

…

It happened not just because Intel championed and set about improving the x86 line – it was because hundreds of other companies vied to do the same thing. Together with Microsoft Windows, Intel was installed and licensed across generation after generation of devices. Yoked together, the pair earned billions of dollars every year, even once the catalyst of IBM had faded. Better still, PCs gained fresh impetus when the internet came along. It wasn’t always a cordial relationship. Microsoft’s chief executive Bill Gates and Andy Grove clashed over Intel’s ambition to drive deeper into software. Gates wrote to Grove at one stage, saying that ‘when Intel finds someone who has some humility about developing operating systems and the complexities involved then maybe we can try to work together’.19 ‘Wintel’ – a portmanteau nickname neither party liked – reached its apotheosis in August 1995 when Microsoft debuted its Windows 95 operating system.

The Great Fragmentation: And Why the Future of All Business Is Small

by

Steve Sammartino

Published 25 Jun 2014

It’s the way it’s always been, excluding the 200-year halcyon period of the industrial era. Dad vs daughter I’ve been thrilled to own a 3D printer for a few years now. I purchased one when they hit their Altair moment (the Altair 8800 is regarded as the first affordable personal computer and the spark of the home computer revolution). It’s a pretty impressive party trick introducing someone to the basic idea of 3D printing, helping them work through their initial incredulity, showing them a little video about it, and then helping them print their first item. It’s a social experiment I’ve undertaken on both my 70-year-old father and my four-year-old daughter.

…

These days the GPS is another ‘free’ device we get with our pocket ‘super computer’, the smartphone. The free super computer In fact, most of the important technologies we use today are becoming integrated into the smartphone, which isn’t really a ‘smart phone’ at all — it’s actually the most personal of personal computers. While Bill Gates aimed to have a computer on every desk in every home, Steve Jobs put a super computer in every person’s pocket. The evidence is in the number of uses for the smartphone. The telephone function only gets 22 of the more than 150 interactions we have with our smartphones daily.2 One of the most amazing things about this super computer is that it’s actually free.

…