Turning the Tide

by

Noam Chomsky

Published 14 Sep 2015

It is important to recognize that little that is happening today is new. The United States has been tormenting Central America and the Caribbean for well over a century, generally in alleged defense against “outside threats.” In the late 1920s, the Marines invaded Nicaragua in defense against the “Bolshevik threat” of Mexico. Secretary of State Frank Kellogg warned that The Bolshevik leaders have had very definite ideas with respect to the role which Mexico and Latin America are to play in their general program of world revolution. They have set up as one of their fundamental tasks the destruction of what they term American imperialism as a necessary prerequisite to the successful development of the international revolutionary movement in the New World...Thus Latin America and Mexico are conceived as a base for activity against the United States.

…

They have set up as one of their fundamental tasks the destruction of what they term American imperialism as a necessary prerequisite to the successful development of the international revolutionary movement in the New World...Thus Latin America and Mexico are conceived as a base for activity against the United States. “Mexico was on trial before the world,” President Coolidge declared as he sent the Marines to Nicaragua, once again.2 Now Nicaragua is the base for the Bolshevik threat to Mexico, and ultimately the United States. It requires no great originality, then, when Reagan, speaking on national television, warns of Soviet intentions to surround and ultimately destroy America by taking over Latin American states, as proven by a statement by Lenin, which, he said, “I have often quoted,” but which happens not to exist;3 or when his speech writers have him say that “Like a roving wolf, Castro’s Cuba looks to peace-loving neighbors with hungry eyes and sharp teeth” and that the troubles in Central America are “a power play by Cuba and the Soviet Union, pure and simple”; or when the White House condemns Nicaragua for its “increased aggressive behavior” against Honduras and Costa Rica as the US proxy army attacks Nicaragua from Honduras and Costa Rica and Secretary of State George Shultz thunders that “we have to help our friends to resist the aggression that comes from these arms” that Nicaragua is acquiring to defend itself from the American onslaught, one act of a drama involving fabricated arms shipments to Nicaragua in a successful exercise in media management to deflect attention from unwanted elections there.4 The media have yet to comment on the similarity to earlier episodes, for example, Hitler’s anger at the “increased aggressive behavior” of Poland as his forces attacked in self-defense.

…

Woodrow Wilson, the revered apostle of self-determination, invaded Mexico and sent his warriors to Haiti and the Dominican Republic, where they blocked constitutional government, reinstituted virtual slavery, tortured, murdered and destroyed, leaving a legacy of misery that remains until today. Evidently, there could be no Bolshevik threat at the time, so we claimed we were defending ourselves against the Huns. Marine Commander Thorpe told new Marine arrivals that the war would last long enough “to give every man a chance against the Hun in Europe as against the Hun in Santo Domingo.” The hand of the Huns was particularly evident in Haiti, he explained: “Whoever is running this revolution is a wise man; he certainly is getting a lot out of the niggers...It shows the handwork of the German.”

Culture of Terrorism

by

Noam Chomsky

Published 19 Oct 2015

They were addressed in the first major publication of the Trilateral Commission, formed at the initiative of David Rockefeller to bring together liberal elites from the United States, Europe and Japan; it is their 1975 study of “the crisis of democracy” that I have been quoting and paraphrasing.22 Every major war of this century has evoked a similar reaction on the part of dominant social groups: business, the political elites that are primarily business-based, the corporate media, and the privileged intelligentsia generally, serving as ideological managers. During and after World War I, the Wilson administration, under the pretext of a Bolshevik threat, launched a “Red Scare” that succeeded in deterring the threat of democracy (in the true sense of the word) while reinforcing “democracy” in the technical Orwellian sense. With broad liberal support, the Red Scare succeeded in undermining the labor movement and dissident politics, and reinforcing corporate power.

…

To induce fear, the propaganda system must be put to work to conjure up whoever happens to be the current Great Satan. Other powers have their own favorites; at various moments of U.S. history the enemy invoked to justify aggression, subversion and the resort to terror has been Britain, Spain or the Huns, but since 1917 the Bolshevik threat has been the device most readily at hand. Hence the renewed appeal under Reagan to the threat of the Evil Empire, advancing to destroy us. At this point, however, a new problem arises: confrontations with the Evil Empire might prove costly to us, and therefore must be avoided. The problem is to confront an enemy frightening enough to mobilize the domestic population, but weak enough so that the exercise carries no cost—for us, that is.

Why the Allies Won

by

Richard Overy

Published 29 Feb 2012

The regime imposed ever more draconian terror on its own forces to keep them fighting until the very end of the war when Hitler, amidst the dying embers of his Reich, ordered any saboteur or deserter shot on the spot.80 The effect of Germany’s conduct of war in the east on the rest of world opinion was bleak. The Allies were able to stoke up the fires of moral indignation almost effortlessly with the string of well-attested atrocities laid at Germany’s door. Though German allies and sympathisers – Italy, Spain, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia – sent troops to help fight the Bolshevik threat, their treatment at German hands was arrogant and discriminatory. Germany was feared and hated by most of Europe, and everything it did in the Soviet Union reinforced this image, even among those non-Russian nationalities who had at first welcomed the German armies as liberators from Russian-dominated communism.

…

One neutral observer noticed in the mood of ‘desperation’ and ‘anxiety’ an open willingness to blame Hitler for what had gone wrong.86 The regime made a virtue of necessity and used the crisis as an opportunity to shift the moral ground of the conflict from uncritical confidence in victory to a sombre defence of the homeland against the barbaric Bolshevik threat. Goebbels was the inspiration behind the change. Hitler disliked the idea of a war of defence, since it smacked of weakness, but he accepted Goebbels’s suggestion that moral justification should now be based on the idea of a life or death struggle between European civilisation, shielded by Germany, and Asiatic barbarism.

The Chomsky Reader

by

Noam Chomsky

Published 11 Sep 1987

In 1926, the marines were sent back to Nicaragua, which they had occupied through much of the century, to combat a Bolshevik threat. Then Mexico was a Soviet proxy, threatening Nicaragua, ultimately the United States itself. “Mexico was on trial before the world,” President Coolidge proclaimed as he sent the marines to Nicaragua once again, an intervention that led to the establishment of the Somoza dictatorship with its terrorist U.S.-trained National Guard and the killing of the authentic Nicaraguan nationalist Sandino. Note that though the cast of characters has changed, the bottom line remains the same: kill Nicaraguans. What did we do before we could appeal to the Bolshevik threat? Wood-row Wilson, the great apostle of self-determination, celebrated this doctrine by sending his warriors to invade Haiti and the Dominican Republic, where they reestablished slavery, burned and destroyed villages, tortured and murdered, leaving in Haiti a legacy that remains today in one of the most miserable corners of one of the most miserable parts of the world, and in the Dominican Republic setting the stage for the Trujillo dictatorship, established after a brutal war of counterinsurgency that has virtually disappeared from American history; the first book dealing with it has just appeared, after sixty years.

The Cold War: A World History

by

Odd Arne Westad

Published 4 Sep 2017

Behind German lines many civilians collaborated freely, especially in the Baltic states and in Ukraine, where significant portions of the population saw the German occupation as a liberation from Soviet rule. Atrocities against Jews were common. Hitler equated Bolshevism with Jewish rule and called his war against Stalin a “crusade to save Europe” from a Judeo-Bolshevik threat. Romanian, Hungarian, Croatian, Slovak, Finnish, and Spanish forces joined the Germans in the first months of the offensive. The German attack on the Soviet Union also brought Britain and the United States closer together. Roosevelt regarded (rightly, based on past performance) his new British colleague as a jingoist and buffoon, who would not be an easy partner for any foreign nation.

…

See Cultural Revolution Great-Russian chauvinism, 280 Greece, 75–76, 91, 215, 371, 517 Greek People’s Liberation Army (ELAS), 75–76 Green parties, 521–522 Grigorenko, Piotr, 514 Gromyko, Andrei, 305, 534, 536 Grósz, Károly, 585 Group of 77, 391–392, 436 GRU (Main Intelligence Directorate of the Red Army), 121, 359 Guam, 21 Guatemala, 224, 301, 340, 345–347, 358 Guevara, Ernesto “Che,” 298–299, 302, 326, 352–353, 361, 379 Guinea, 277 Guinea-Bissau, 338, 481–482 GULag system, 122, 192, 195 Gulf of Tonkin resolution, 321 Gulf War, 610 Guomindang (National People’s Party), 32, 130, 139–142, 148, 279 Guthrie, Woody, 48 Hanson, Ole, 30–31 Havel, Václav, 513–514, 522, 595–596 Hekmatyar, Gulbuddin, 577 Helms, Richard, 356 Helsinki Accords (1975), 514 Helsinki Final Act, 390–391 Helsinki process, 504, 522 Helsinki Watch, 574 Heym, Stefan, 109, 193 Hirohito (Emperor), 136 Hiroshima, 6, 134 Hitler, Adolf, 36–42, 44, 58, 74, 627 Hizb-i-Islami, 531 Ho Chi Minh, 26, 32, 56, 147–150, 264, 278, 313–316 Ho Chi Minh trail, 316 Holocaust, 71, 451 Honecker, Erich, 546, 590–591 Hong Kong, 403, 561 Hopkins, Harry, 62, 79 Horn of Africa crisis, 489 hostage crisis, Iranian, 493–494 Hu Yaobang, 586–587 human rights abuses in Latin America, 358, 574 Argentina, 571, 574 Carter and, 485, 487, 489 Chile, 574 crisis in post-WWII Europe, 72 decolonization and, 432–433 defense of, 514 El Salvador, 570 Most Favored Nation trading status, 476 National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), 567 human rights nongovernmental organizations, 573–574 Soviet Union and, 476, 485, 487 Human Rights Watch, 574 Humphrey, Hubert, 440 Hungarian Communist Party, 184, 203, 585, 594 Hungarian revolution, 202–205, 229, 242 Hungarian Soviet Republic, 33–34, 86 Hungarian Writer’s Union, 202 Hungary Communists in, 79, 86–87, 203–204, 522, 585–586 conditions in 1980s, 513 elections of 1990, 594 killings under Communist rule, 185 liberalization in late-1980s, 585–586 post-WWII period in, 85–87 protests (1956), 185, 201–206, 219, 241–242 Soviet occupation, 77, 273, 435 western loans, 513 hunger, in post-WWII Europe, 71–73 Husák, Gustáv, 376, 595 Hussein, Saddam, 469, 565, 610 Hussein (King), 462 hydrogen bomb (H-bomb), 102, 303 Iakovlev, Aleksandr, 542 Ianaev, Gennadii, 608, 611 Iazov, Dmitrii, 602 ICBMs (intercontinental ballistic missiles), 225 identity politics, 7 identity talk, 575 imperialism, United States, 245, 275, 350, 377, 383 Inchon, Korea, 171 India, 423–447, 627 anti-Chinese propaganda by, 249 anticolonial movements, 24 Bandung Conference, 271, 424, 428 Bangladesh war, 441–444 border war with China, 246, 249–250, 436–438 Chinese revolution, view of, 145 Communists in, 153, 424–425 Congo crisis (1960–1961), 435 Delhi Declaration, 564–565 foreign policy, 424–429, 432–437, 563 independence, 106, 129, 151–152, 423, 425 Kashmir, 425, 430, 437–438 Korean War, reaction to, 177, 181–182 Non-Aligned Movement, 249 nuclear test, 444 partition of (1947), 425 relations with China, 430–432, 438–439 relations with United States, 439–440 Second Five Year Plan, 429 self-government, 55–56 Soviet Union and, 281–282, 429–430, 434–435, 438–439, 443–447, 487, 564–565 Tibet and, 430–431 Tito visit, 433 trade unions, 131 Yugoslavia and, 433–434 Indian National Congress, 14, 130, 151–152, 263 Indonesia at Bandung Conference, 271, 327 Communists in, 131, 148, 278, 327–329 counterrevolution, 325 coup, 328–329 independence, 56, 129, 147–148, 326–327 as indigenous, Muslim state, 130 killings after coup (1965), 329 Soviet Union and, 328 state planning, 130 industrialization, 9, 187, 219 information, global spread of, 553–554 inheritance of acquired characteristics, 207 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), 225, 303 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 67 International Department of the Communist Party, 488–489 International Imperialism and Colonialism, 279 International Monetary Fund (IMF), 67, 100, 554 International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, 628 Internet, 525 internment of Japanese-Americans, 120 Iran British occupation, 56, 131, 154 Communists in, 32, 155, 269, 451, 493 Eisenhower and, 224 hostage crisis, 493–494 oil, 268–269 revolution, 493–494, 576 secular and religious political conflict, 450–451 Soviet occupation, 131, 154–155, 269 US post-WWII views on, 132 war with Iraq, 565 Iran-Contra scandal, 570, 580 Iraq, 153 Ba’ath Party, 455, 458, 469 Britain and, 452 Iran war, 565 revolution, 455–456 Soviet Union and, 469, 487, 565 United States and, 610, 618 Irgun, 468 Iron Curtain, 62, 89–90, 226, 592, 603 Islamic Brotherhood, 531 Islamists, 450 Afghan, 494–496, 498, 530–531, 539 in Egypt, 453, 471 Muslim Brotherhood, 453, 471 revolution in Iran, 576 terrorists, 471, 533 United States view on, 472 Ismay, Lord, 119 Israel, 154, 457–472 Camp David accords, 492 October War (1973), 464–466 politics in, 468 Soviet Union and, 156, 370, 451, 457 Suez crisis, 272 US support, 337, 451, 457–458, 460, 463–470 Italy Brigate Rosse, 520 Communists in, 74, 113, 219, 372–373, 502 economic growth, post-WWII, 218 European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), 215–217 Fascists, 27, 36 Gorbachev and, 547 Soviet Union and, 503 worker migration, 371 Iudin, Pavel, 245 Jackson, Henry, 476 Jackson-Vanik amendment to the Trade Act, 529 Jakeš, Miloš, 595 James, Henry, 17 Japan attack on United States, 43, 47 Communists in, 131, 136–137 conditions after World War II, 129, 134 constitution, postwar, 135 dependence on oil, 268 economic growth, 395–396, 401–402, 560–561 expansion, 136, 159 “Give Us Rice” mass meetings, 135 Japan-China relations in 1980s, 561 Korean War, reaction to, 177 military production in WWII, 50 Japan Nixon Shocks of 1971, 412–413 post-WWII industrial production, 66 reforms, postwar, 135–139 reverse course by Americans on, 137 surrender/capitulation, 132, 140, 149, 163 trade unions, 136, 137, 400, 401, 413 United States occupation, 135–139 US-Japan alliance, 138–139, 401, 428 war against Russia, 16, 24 war with China, 47, 49–50, 139–140, 159 war with Soviet Union, 50, 59, 131, 140, 163 in World War II, 47 Japanese-Americans, internment of, 120 Japanese Red Army, 521 Jaruzelski, Wojciech, 512, 583–585 Jeju Island, 166 Jews Hitler’s atrocities against, 45, 46, 71 Israel creation, 153–154 murders in eastern Europe, 81, 184 Soviet Union and, 124, 370 Stalin’s distrust of Hungarian, 86 US Jewish lobby, 485–486 Jiang Qing, 251, 256, 557 Jiménez de Aréchaga, Justino, 347 John Paul II, 511 Johnson, Lyndon B. Brazil and, 351–352 Congo and, 326 domestic issues, 319, 372 Indonesia and, 329 invasion of Czechoslovakia, 376 Israel support, 337 Latin America and, 350 Pakistan and, 438 on US troops in Europe, 383 Vietnam and, 318–323, 330, 335–336, 377 Jordan, 154, 460–462 Judeo-Bolshevik threat, 45 Kádár, János, 205–206, 513, 585 Kaganovich, Lazar, 206 Kania, Stanislaw, 512 Karmal, Babrak, 530 Kashmir, 425, 430, 437–438 Kennan, George F., 90–91, 99, 103, 108, 136–137, 345 Kennan’s Long Telegram, 90–91, 99 Kennedy, John F., 287–311 Alliance for Progress, 349–350 assassination, 309, 318 background of, 288–289 Brazil and, 351 on Chinese Communists, 311 Cuba and, 290, 297–310 Eisenhower and, 228, 230–231 inaugural address, 289 India-China conflict, 437 Khrushchev and, 290, 292–298 Laos and, 288, 291–292, 317 Latin America and, 349 nuclear response plan, 303–304 nuclear weapons, 303–309 Peace Corps, 291 US relationship with Third World, 290–292 Vietnam and, 317–318 visions for Europe, 292 winning the Cold War, 288–289, 291, 310 Kennedy, Paul, 560 Kennedy, Robert, 302–303, 308, 398 Kenyatta, Jomo, 266 KGB, 121, 359, 369, 508, 528, 603–604, 612–613 Khan, Yahya, 442, 444 Khmer Rouge, 481, 490–491, 532, 562 Khomeini, Ayatollah Ruhollah, 493 Khrushchev, Nikita, 194–208 background of, 195–196 Berlin and, 292–297, 367 Brezhnev and, 366 charm offensive, 228 China and, 196, 237–238, 246–248 China-India dispute, 246 at Communist Party Congresses, 198–199, 241, 244, 434 Congo crisis, 283 coup attempt (1957), 206 criticism of Stalin, 199–200, 281 eastern Europe and, 196 Hungary and, 203–207 India and, 429–430 Kennedy and, 290, 292–298 Laos and, 292 Mao meetings, 245–247 Middle East and, 456–457 nuclear weapons and, 303–309 Paris summit (1959), 229–230 on Poland, 202–203 reform program, 196–197 replacement of, 366–367 Vietnam and, 315, 317 virgin lands campaigns, 207–208 visit to United States (1959), 246 Yugoslavia and, 197–198 Kim Il-sung, 145, 162–169, 191, 244 King, Martin Luther, Jr., 335, 398, 405 Kirkpatrick, Jeane, 417, 486, 508 Kishi Nobusuke, 401 Kissinger, Henry, 399 Angola and, 483–484 Beijing visit (1971), 408–409, 441–442 Chile and, 356 on difference in the Russians and the China, 408 Egypt and, 463 in Ford Administration, 420 India and, 443–444 Israel and, 464–465, 466 Mao and, 412 Middle East and, 466–467 nuclear talks with Soviet Union, 408 Soviet Union and, 408, 477 Kiszczak, Czeslaw, 584 Kohl, Helmut, 516, 522, 547, 590, 593–594, 605–606 Komer, Robert, 326, 329–330, 337–338 konfrontasi, 327 Koo, Wellington, 142 Korea, 159–182 Communists in, 129, 145, 161–162, 164 in Japanese empire, 159–160 nationalism, 160–162 Soviet occupation, 131, 167 strategic importance, 164–165 trade unions, 164 US occupation, 131 in World War I, 160 Korean War, 138, 144, 169–182 armistice, 179–182, 224 atrocities, 169 China and, 144, 146, 172–176, 233–235 destruction of, 179, 182 Inchon landings, 171 international reaction, 169–170, 176–178 Japan and, 400 nationalism and, 158 North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and, 181, 213 North Korean attack of South (1950), 169–171 nuclear warfare fears, 177 origins, 159 prisoners of war, 180 Stalin’s sanction of, 167–169 United Nations and, 170, 174–175, 178 war scare in United States, 175–176 Kosovo, 607 Kostov, Traicho, 125 Kosygin, Aleksei, 368–369, 373, 375, 465 Kravchuk, Leonid, 609 Krenz, Egon, 591 Kriuchkov, Vladimir, 603, 613 Kubitschek, Juscelino, 351 Kuril Islands, 138 Kuwait, 456, 616 labor camps China, 242, 253, 404 North Vietnam, 315 Soviet Union, 37, 123, 185, 191–192, 195, 280, 418 labor unions, 105, 146, 222 Lancaster House Agreement, 566 land reform Chile, 356 Cuba, 299 Guatemala, 346 Nicaragua and, 498 North Korea, 165–166 Vietnam, 315 Laos, 288, 291–292, 317, 407 Lassalle, Ferdinand, 24 Latin America, 339–363 Alliance for Progress, 349–350 civilian role in 1980s, 571 Communists in, 348, 359 debt crisis of 1980s, 571–573 good neighbor policy, 344 human rights violations, 574 La Década Perdida, 573 military regimes, 350, 357–358, 361–363 nationalism, 339, 342–343, 353–354, 360 populism, 343 republicanism in, 341–342 US hegemony in, 339–340 US military intervention, 344, 359 in WWII, 344 Lattimore, Owen, 120 Latvia, 123, 600–601 Le Duan, 316–317, 333–334, 405, 479 League Against Imperialism, 33 League of Nations, 29 Leahy, William, 83 Lebanon, 452, 456–457, 461 Lee Kuan Yew, 403 Lend-Lease agreements, 46, 62 Lenin, Vladimir, 5, 12, 23–24, 27–28, 31–35, 108, 278, 280 Li Da’an, 180 Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), 400–401, 412–413 liberalism, post-WWI, 31 Liberia, 566 Libya, 466 Liebknecht, Karl, 26, 33 Lin Biao, 141, 251, 255–257, 409 Lin Xuepu, 180 Lithuania, 123, 582, 600–601 “little Stalins,” 191, 197 Liu Shaoqi, 235, 242, 248, 250, 251–252, 258, 292, 409 Lomè Conventions, 393 loyalty boards, 176 Lula, 361–363 Lumumba, Patrice, 282–283, 293, 325–326 Lutte Ouvrière, 380 Lysenko, Trofim, 207 Maastricht agreement of 1992, 593 MacArthur, Douglas, 171, 174–175 Maclean, Donald, 310 Macmillan, Harold, 266 Mahalanobis, Prasanta Chandra, 429 Malaka, Tan, 278 Malaysia, 147, 270, 327 Malcolm X, 285 Malenkov, Georgii, 194, 198, 206 Mallaby, Aubertin, 147–148 Man of Marble (film), 189 Manchuria, 140–142, 162, 165, 167, 172 Mandela, Nelson, 285, 429, 566, 575 Mandelstam, Osip, 54 Mansfield, Mike, 383 Mao Anying, 178 Mao Zedong, 139–140, 233–259 Cultural Revolution, 235, 379 Great Leap Forward, 242–244, 246–248, 256 India and, 431 Indonesia and, 328 Khrushchev and, 234 on Kissinger, 412 Korea and, 167–168, 171–175 nationalism, 248 People’s Republic of China (PRC) declared, 143 personal dictatorship, 191, 250 poetry, 248 public hero-worship of, 248 push for advanced socialism, 241–242 revolution and, 144 shelling of Taiwan, 245–246 Soviet Union and, 143, 154–155, 245–246, 255–256, 409 on Stalin, 200 travel of 1965–1966, 250 US relations and, 244, 556 Vietnam and, 322, 333, 404, 413 Mariam, Mengistu Haile, 488–489 Marshall, George C., 92–94, 140, 142 Marshall Plan, 94–95, 102, 110–113, 115, 210–212, 214–215, 217, 219 Marx, Karl, 10–11, 24 Mazowiecki, Tadeusz, 588 McCarthy, Joseph, 120–121, 146, 176, 191, 225–226 McKinley, William, 12 McNamara, Robert, 303–304, 308, 320 Mehta, Jagat Singh, 446 Meir, Golda, 461, 464, 466–467 Mendès-France, Pierre, 151 Menon, K.

Near and Distant Neighbors: A New History of Soviet Intelligence

by

Jonathan Haslam

Published 21 Sep 2015

Their continued and uncritical purchase of dubious official documents fabricated for this undiscriminating market inadvertently provided welcome dividends for the Soviet Union’s needy foreign exchange reserves. The Russians, of course, noticed how active the British were. Not only did MI6 carry out espionage on its own account, but it could also rely on help from foreign countries similarly preoccupied by the Bolshevik threat. The KRO report for 1923–1924 noted, “So, for example, the intelligence services of Estonia, Finland, Latvia and Lithuania, and, to a certain extent, those of Poland, and recently the Swedes and Norwegians, work especially and exclusively for England. The Poles and the Romanians work for the French.

Year 501

by

Noam Chomsky

Published 19 Jan 2016

The October revolution also provided the framework for Third World intervention, which became “defense against Communist aggression,” whatever the facts might be. Avid US support for Mussolini from his 1922 March on Rome, later support for Hitler, was based on the doctrine that Fascism and Nazism were understandable, if sometimes extreme, reactions to the far more deadly Bolshevik threat—a threat that was internal, of course; no one thought the Red Army was on the march. Similarly, the US had to invade Nicaragua to protect it from Bolshevik Mexico, and 50 years later, to attack Nicaragua to protect Mexico from Nicaraguan Bolshevism. The supple character of ideology is a wonder to behold.

Killing Hope: Us Military and Cia Interventions Since World War 2

by

William Blum

Published 15 Jan 2003

In 1918, the barons of American capital needed no reason for their war against communism other than the threat to their wealth and privilege, although their opposition was expressed in terms of moral indignation. During the period between the two world wars, US gunboat diplomacy operated in the Caribbean to make "The American Lake" safe for the fortunes of United Fruit and W.R. Grace & Co., at the same time taking care to warn of "the Bolshevik threat" to all that is decent from the likes of Nicaraguan rebel Augusto Sandino. By the end of the Second World War, every American past the age of 40 had been subjected to some 25 years of anti-communist radiation, the average incubation period needed to produce a malignancy. Anti-communism had developed a life of its own, independent of its capitalist father.

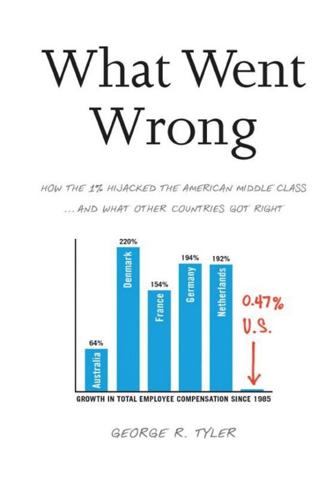

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by

George R. Tyler

Published 15 Jul 2013

For the most part, the great European compromise succeeded.”47 But the default setting remained dictatorship and disrupted commerce, which reemerged in the wake of World War I as inflation, starvation, and the bloody flag of revolution stalked Europe, especially Germany.48 During the disastrous Weimar inflation of the early 1920s, a streetcar ride that had cost a single mark before the war became priced at 15 billion.49 Germany was the world’s third largest economy at the time, and the failure of capitalism there in the early Bolshevik era would have had profound implications, irresistibly thrusting Lenin and later Stalin into the heart of an enfeebled Europe. The armed Bolshevik threat Europe faced down in the tumult following World War I was an existential tipping point for capitalism. There was a pitched uprising in Berlin, bloody insurrections featuring a homegrown Red army occupying the Ruhr in 1920, Saxony, and Thuringia under Bolshevik governments in 1923, and an attempted Communist revolution in conservative Bavaria.50 The westward march of the Red Army itself stalled at the Vistula, thanks to Józef Pilsudski, and southward at the Caucasus, thanks to Kemal Atatürk.51 The weapons were bullets and social reforms, including laws like the eight-hour workday (France 1919) and mandated corporate work councils in 1920, along with unemployment insurance, health, and welfare subsidies.

Ayn Rand and the World She Made

by

Anne C. Heller

Published 27 Oct 2009

She also visited Eugene Lyons of Reader’s Digest, who invited her to a party in his apartment, where she encountered the political idol of her early adolescence, the former Russian prime minister Aleksandr Kerensky. He was now in his sixties, immaculately dressed, with thick glasses and a slight stoop. Introduced, they spoke in Russian. As they discussed their native land, she wondered if he would express second thoughts, or possibly regret, about his government’s failure to take seriously enough the Bolshevik threat in 1917. Instead, she listened, appalled, as he prattled on about how much Russians hated Stalin and how much they had loved Kerensky. Worse, summoning a mystical fatalism she deplored in her native culture, he insisted that the soul of the Russian people would one day set them free. He was a typical Russian sentimental fool, with a fat Russian smile and no capacity for analytic thought.

Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World

by

Margaret Macmillan; Richard Holbrooke; Casey Hampton

Published 1 Jan 2001

They would also try, unsuccessfully, to persuade their friends in Europe, such as Czechoslovakia, Poland and Greece, to accept small armed forces.1 Disarmament was good in itself, but it was difficult to reach agreement on how much of an army Germany should be left with. The new German government had to be able to put down rebellion at home. Should it also be strong enough to hold off the Bolshevik threat from the east? The Allies could not do it for them. Neither could the states of central Europe. They were not only struggling to survive, but, as Hankey said severely, “there has not been the smallest sign of any serious attempt at combined effort to resist the Bolshevists among them. On the contrary, they show all the worst qualities that we have become accustomed to in the Balkan states.”

The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance

by

Ron Chernow

Published 1 Jan 1990

As Coolidge later said, “It would be difficult to imagine a harder assignment. But Mr. Morrow never had any taste for sham battle.”17 American Catholics and oilmen were agitating to break diplomatic relations with Mexico, and some called for a military invasion. Secretary of State Kellogg had already condemned the regime of President Plutarco Elias Calles as a “Bolshevik threat.”18 In American eyes, Mexico had committed multiple sins. It had nationalized church property and closed Catholic schools, defaulted on foreign debt, insisted that oil companies trade in property titles for government concessions, and confiscated American-owned land without compensation. Newspapers were calling Mexico America’s foremost foreign-policy problem.