Fire in the Valley: The Birth and Death of the Personal Computer

by

Michael Swaine

and

Paul Freiberger

Published 19 Oct 2014

He was selling all the Altairs he could get, between 10 and 50 a month, plus anything else he could get from IMSAI and Proc Tech. The MITS edict, Terrell concluded, was not only pointless but, if he followed it, financially harmful as well. * * * Figure 51. Byte Shop The original Mountain View Byte Shop (Courtesy of Paul Terrell) It wasn’t long before David Bunnell, then MITS vice president of marketing, called to cancel Byte Shop’s Altair dealership. Terrell argued that MITS should regard Byte Shop as something like a stereo store that carried many different brands and could turn a profit for them all. Bunnell waffled. It was Roberts’s decision, he said. At the World Altair Computer Convention in March 1976, Terrell approached Roberts directly about his being dropped from the roster of MITS dealers.

…

Check in hand, Terrell would ask, “You want cash on the barrelhead, boys?” It was hardware war. Terrell had opened Byte Shop in December 1975. By January, people who wanted to open their own stores were approaching him. He signed dealership agreements with them in which he would take a percentage of their profits in exchange for the name and business guidance. Other Byte Shops soon appeared in Santa Clara, San Jose, Palo Alto, and Portland. In March 1976, Terrell incorporated as Byte, Inc. Terrell was part of the hobbyist community. He named his store after the leading hobbyist magazine, and he insisted that Byte Shop managers in the Northern California area attend meetings of the Homebrew Computer Club.

…

But unlike computer design, which can be done for love or for money, retailing is necessarily a commercial venture. Computer retailing quickly attracted individuals more aggressive than Heiser, including Paul Terrell. Byte Shop Paul Terrell’s friends warned him that retailing computers would never work. Some people, Terrell mused, also said it never snowed in Silicon Valley. Terrell recalled his friends’ warnings as he watched snow drifting down on December 8, 1975—the day he opened his Mountain View Altair dealership, Byte Shop, in the heart of Silicon Valley. Like all the other Altair dealers, Terrell soon ran headlong into the MITS exclusivity policy, except that Terrell chose to ignore it.

Troublemakers: Silicon Valley's Coming of Age

by

Leslie Berlin

Published 7 Nov 2017

Early in 2016, he asserted, “I have never protested anything in my life.”3 But, he says of that day in the garage four decades ago, “What was there far overshadowed how they might be dressed.”4 Jobs and Wozniak had transformed the garage into a makeshift manufacturing line for the final assembly of the circuit boards for a computer they were calling the Apple I.IX Thus far they had sold 100 boards at $500 each to the Byte Shop, a tiny new store in a strip mall in Mountain View. The Byte Shop would add a keyboard and screen and resell the computer to customers, mostly young white guys whom one early visitor described as “a handful of geeks having technical conversations with each other.”5 Markkula, stepping carefully among the boxes of parts on the garage’s cement floor, had no interest in the Apple I.VIII The machine required that its users possess not only a monitor, keyboard, and tape drive from which to reload every bit of software every time the machine turned on, but also to have familiarity with hexadecimal code and a soldering iron.

…

He suggested that Xerox could pursue seven possible applications for the Alto (“super calculators” for specific user communities; a custom message system for the military; and systems for accounting, computer research, personnel management, stenotype, and publishing). There Are No Standards Yet MIKE MARKKULA Even by the time Mike Markkula visited Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak in the garage in the fall of 1976, Apple was a profitable, albeit very small and very amateur, operation. The circuit boards sold to the Byte Shop for $500 each cost Apple about $220 to assemble.1 Before Markkula, however, Apple was a business by only the loosest definition. The family bedrooms and garage were rent free. The sales force was Jobs and Wozniak driving around to electronics stores and asking the owners if they wanted to sell Apple computers.2 The only two people being paid for their labor were Jobs’s sister and a friend, Dan Kottke, who earned $1 per board and $4 per hour, respectively, for their work.

…

The sales force was Jobs and Wozniak driving around to electronics stores and asking the owners if they wanted to sell Apple computers.2 The only two people being paid for their labor were Jobs’s sister and a friend, Dan Kottke, who earned $1 per board and $4 per hour, respectively, for their work. Jobs and Wozniak had come up with the $666.66 retail price for the Apple I by adding 30 percent to the $500 they were charging the Byte Shop and rounding so that the price would contain repeating digits—something that Wozniak enjoyed seeing.3 Markkula’s note card commitment had been to help promising entrepreneurs in any way he could one day per week. Standing in Jobs’s garage, Markkula knew that Wozniak’s Apple II computer was a magnificent answer to the hopes of anyone who had ever longed to own a machine.

Steve Jobs

by

Walter Isaacson

Published 23 Oct 2011

But one important person stayed behind to hear more. His name was Paul Terrell, and in 1975 he had opened a computer store, which he dubbed the Byte Shop, on Camino Real in Menlo Park. Now, a year later, he had three stores and visions of building a national chain. Jobs was thrilled to give him a private demo. “Take a look at this,” he said. “You’re going to like what you see.” Terrell was impressed enough to hand Jobs and Woz his card. “Keep in touch,” he said. “I’m keeping in touch,” Jobs announced the next day when he walked barefoot into the Byte Shop. He made the sale. Terrell agreed to order fifty computers. But there was a condition: He didn’t want just $50 printed circuit boards, for which customers would then have to buy all the chips and do the assembly.

…

Terrell was at a conference when he heard over a loudspeaker that he had an emergency call (Jobs had been persistent). The Cramer manager told him that two scruffy kids had just walked in waving an order from the Byte Shop. Was it real? Terrell confirmed that it was, and the store agreed to front Jobs the parts on thirty-day credit. Garage Band The Jobs house in Los Altos became the assembly point for the fifty Apple I boards that had to be delivered to the Byte Shop within thirty days, when the payment for the parts would come due. All available hands were enlisted: Jobs and Wozniak, plus Daniel Kottke, his ex-girlfriend Elizabeth Holmes (who had broken away from the cult she’d joined), and Jobs’s pregnant sister, Patty.

…

“She just wanted him to be healthy, and he would be making weird pronouncements like, ‘I’m a fruitarian and I will only eat leaves picked by virgins in the moonlight.’” After a dozen assembled boards had been approved by Wozniak, Jobs drove them over to the Byte Shop. Terrell was a bit taken aback. There was no power supply, case, monitor, or keyboard. He had expected something more finished. But Jobs stared him down, and he agreed to take delivery and pay. After thirty days Apple was on the verge of being profitable. “We were able to build the boards more cheaply than we thought, because I got a good deal on parts,” Jobs recalled. “So the fifty we sold to the Byte Shop almost paid for all the material we needed to make a hundred boards.” Now they could make a real profit by selling the remaining fifty to their friends and Homebrew compatriots.

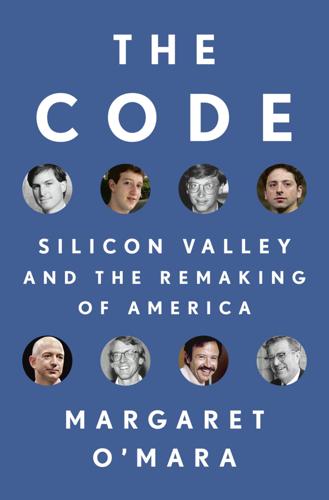

The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America

by

Margaret O'Mara

Published 8 Jul 2019

Dobb’s he helped fill the gap between increased availability of computers and a lack of off-the-shelf software to go with it.10 Then there were retailers, who’d popped up on the scene as distributors of Altair kits, and quickly morphed into far more. Paul Terrell started the Byte Shop in Mountain View at the end of 1975, disregarding the advice of friends who thought he’d never find customers. When sixteen people showed up one day for a seminar at the store on “Introduction to Computers,” Terrell realized that computer courses needed to be a regular feature at the Byte Shop. How-to classes translated into sales, which were so brisk that Terrell opened a second location four months later, and had sixty stores nationwide by the end of 1977.

…

It featured Isaac Newton sitting under a tree, surrounded by words uttered not by Newton, but by William Wordsworth: “A mind forever voyaging through strange seas of thought—alone.” The inaugural sales flyer was similarly loopy, with a typo in the first sentence.7 Jobs persuaded Paul Terrell at the Byte Shop to buy fifty units of the Apple I, which Terrell agreed to do under one condition: no kits. The machines needed to be fully assembled. In a move that Apple’s marketers later made sure to burnish into company legend, Jobs sold his VW microbus and Woz sold two HP calculators to finance the start-up costs.

…

“The truth is that one of the main problems—perhaps the main problem—of the time is that our world suffers from information overload, and can no longer handle it unaided,” wrote British futurist Christopher Evans in his prescient 1979 bestseller, The Micro Millennium. “The world needs computers now, and it will need them more in the future; and because it needs them, it will have them.”26 CHAPTER 12 Risky Business As hundreds crowded into Homebrew meetings, long lines formed outside Byte Shops and Computer Faire booths, as subscriptions soared to Byte and tens of thousands of copies of 101 BASIC Computer Games flew off bookstore shelves, it certainly felt like a revolution was on its way. But as 1977 rolled into 1978, few of the rangy little companies sprouting out of the computer-club world had managed to do what Apple had done: grab the outside funding and management expertise needed to turn a neophyte’s garage start-up into a scaled-up operation aimed at a broader consumer market.

So Good They Can't Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work You Love

by

Cal Newport

Published 17 Sep 2012

Jobs wanted to sell one hundred, total, which, after removing the costs of printing the boards, and a $1,500 fee for the initial board design, would leave them with a nice $1,000 profit. Neither Wozniak nor Jobs left their regular jobs: This was strictly a low-risk venture meant for their free time. From this point, however, the story quickly veers into legend. Steve arrived barefoot at the Byte Shop, Paul Terrell’s pioneering Mountain View computer store, and offered Terrell the circuit boards for sale. Terrell didn’t want to sell plain boards, but said he would buy fully assembled computers. He would pay $500 for each, and wanted fifty as soon as they could be delivered. Jobs jumped at the opportunity to make an even larger amount of money and began scrounging together start-up capital.

…

It follows that if you want a great job, you need something of great value to offer in return. If this is true, of course, we should see it in the stories of our trio of examples—and we do. Now that we know what to look for, this transactional interpretation of compelling careers becomes suddenly apparent. Consider Steve Jobs. When Jobs walked into Paul Terrell’s Byte Shop he was holding something that was literally rare and valuable: the circuit board for the Apple I, one of the more advanced personal computers in the fledgling market at the time. The money from selling a hundred units of that original design gave Jobs more control in his career, but in classic economic terms, to get even more valuable traits in his working life, he needed to increase the value of what he had to offer.

Valley of Genius: The Uncensored History of Silicon Valley (As Told by the Hackers, Founders, and Freaks Who Made It Boom)

by

Adam Fisher

Published 9 Jul 2018

And I was trying to sell the rest of them so that we could get our microbus and calculator back. Steve Wozniak: And for a while we were getting the parts on thirty days’ credit with no money and we built the computers in ten days and sold them for cash at the Byte Shop. Trip Hawkins: The Byte Shop was the first of the chain computer stores. In the Byte Shop basically you’ve got a whole bunch of card tables set up that had a bunch of circuit boards on it, and a bunch of really smelly geeky people talking jargon. Steve Wozniak: So that was how we ran for, you know, a good year with the Apple I computer. Trip Hawkins: It was not really a commercial product.

Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution - 25th Anniversary Edition

by

Steven Levy

Published 18 May 2010

Without computer access, Mark Duchaineau later said, “there would have been this big void . . . it would be like you didn’t have your sight, or hearing. The computer is like another sense or part of your being.” Coming to this discovery in the late seventies, Mark was able to get access to computers for his personal use and become a hacker of the Third Generation. While still in high school, he landed a job at the Byte Shop in Hayward. He loved working at the computer shop. He’d do some of everything—repairs, sales, and programming for the store owner as well as the customers who needed custom programs. The fact that he was getting no more than three dollars an hour didn’t bother him: working with computers was pay enough.

…

In fact, he found it virtually impossible to retain what he called “the little nitpicking things that I knew I’d never need” that were unfortunately essential for success in Berkeley’s computer science department. So like many Third-Generation hackers, he did not get the benefit of the high-level hacking that took place in universities. He dropped out for the freedom that personal computers would provide, and went back to the Byte Shop. An intense circle of pirates hung out at the shop. Some of them had even been interviewed in an article about software piracy in Esquire that made them seem like heroes. Actually, Mark considered them kind of random hackers. Mark, however, was interested in the kinds of discoveries that it took to break down copy protection and was fairly proficient at breaking copy-protected disks, though he really had no need for the programs on the disks.

…

Wizards Buchanan, Bruce, Life Budge, Bill, Summer Camp Bueche, Chuck, Frogger, Applefest, Applefest Bug (robot) program, Winners and Losers, Winners and Losers Bunnell, David, Every Man a God Burnstein, Malcolm, Revolt in 2100 Burroughs computer, The Wizard and the Princess Byte (measurement), Every Man a God Byte magazine, Tiny BASIC, Tiny BASIC Byte Shop, Applefest C California Polytechnic, Pomona Campus, The Wizard and the Princess Call Computer service, Woz Cambridge urchins, The Tech Model Railroad Club Captain Crunch, Woz, Woz, Secrets, The Brotherhood, Applefest Carlston, Doug, The Brotherhood, The Brotherhood, Applefest Carlston, Gary, The Brotherhood, The Brotherhood Carmack, John, Afterword: 2010 Carnegie-Mellon University, Life, Life Carpetbaggers, The (Robbins), The Wizard and the Princess Cassette recorders, The Brotherhood CBS opening, Spacewar Charles Adams Associates, Greenblatt and Gosper, Greenblatt and Gosper Chat program, Woz Chess program, The Tech Model Railroad Club, The Hacker Ethic Chicken Hawk system, Every Man a God Chinese food, Greenblatt and Gosper Choplifter game, Frogger Christie, Agatha, The Wizard and the Princess Circle Algorithm hack, Spacewar CL 9, Afterword: 2010 Clements, Bob, The Midnight Computer Wiring Society Clue board game, The Wizard and the Princess Coarsegold, The Wizard and the Princess, The Third Generation Coats, Tracy, Wizard vs.

Becoming Steve Jobs: The Evolution of a Reckless Upstart Into a Visionary Leader

by

Brent Schlender

and

Rick Tetzeli

Published 24 Mar 2015

Steve had a kind of hyperawareness of his surroundings that allowed him to leap at opportunities that presented themselves. So when Paul Terrell, the owner of the Byte Shop computer store in nearby Mountain View, introduced himself to Steve and Woz after the presentation and let them know he was impressed enough to want to talk about doing some business together, Steve knew exactly what to do. The very next day he borrowed a car and drove over to the Byte Shop, Terrell’s humble little store on El Camino Real, Silicon Valley’s main thoroughfare. Terrell surprised him, saying that if the two Steves could deliver fifty fully assembled circuit boards with all the chips soldered into place by a certain date, he would pay them $500 a pop—in other words, ten times what Steve and Woz had been charging club members for the printed circuit boards alone.

Computer: A History of the Information Machine

by

Martin Campbell-Kelly

and

Nathan Ensmenger

Published 29 Jul 2013

Some of them, such as Byte and Popular Computing, followed in the tradition of the electronics hobby magazines, while others, such as the whimsically titled Dr. Dobb’s Journal of Computer Calisthenics and Orthodontia, responded more to the computer-liberation culture. The magazines were important vehicles for selling computers by mail order, in the tradition of hobby electronics. Mail order was soon supplanted, however, by computer stores such as the Byte Shop and ComputerLand, which initially had the ambiance of an electronics hobby shop: full of dusty, government-surplus hardware and electronic gadgets. Within two years, ComputerLand would be transformed into a nationwide chain, stocking shrink-wrapped software and computers in colorful boxes. While it had taken the mainframe a decade to be transformed from laboratory instrument to business machine, the personal computer was transformed in just two years.

…

He and Jobs called it the “Apple,” for reasons that are now lost in time, but possibly as a nod to the Beatles’ record label. While Jobs never cared for the “nit-picking technical debates” of the Homebrew computer enthusiasts, he did recognize the latent market they represented. He therefore cajoled Wozniak into developing the Apple computer and marketing it, initially through the Byte Shop. The Apple was a very crude machine, consisting basically of a naked circuit board and lacking a case, a keyboard, a screen, or even a power supply. Eventually about two hundred were sold, each hand-assembled by Jobs and Wozniak in the garage of Jobs’s parents. In 1976 Apple was just one of dozens of computer firms competing for the dollars of the computer hobbyist.

The Big Score

by

Michael S. Malone

Published 20 Jul 2021

HP settled out of court.) In March 1980, Pizza Time Theaters sued its largest franchiser for $250 million for fraud, unfair competition, and breach of contract—in essence claiming that the franchiser, according to the Pizza Time president, “picked our brains” for technical information to build its own pizza restaurant. Byte Shops personal computer retail store chain sued Apple for dropping it from the licensed distributor list. The most remarkable suit to date came in May 1983, when a former vice president of Advanced Micro Devices sued that firm for $31 million, claiming that AMD had defrauded him by purposefully causing the subsidiary he helped run to fail.

…

Members would work long hours perfecting a new circuit diagram or program to show off before their fellow members. “People at Homebrew openly exchanged [information] that only a few years later would be regarded as company secrets,” said one former member. Adam Osborne was there, as were the future founders of Cromemco Computer and the Byte Shop Computer Stores. There were computer professionals as well as kids. And there was 25-year-old Stephen Wozniak. Besides his already highly regarded technical prowess, Woz had something equally important: the friendship of 20-year-old Steve Jobs. Jobs, on the other hand, had himself a gold mine.

The Innovators: How a Group of Inventors, Hackers, Geniuses and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution

by

Walter Isaacson

Published 6 Oct 2014

Wozniak, however, understood what Jobs contributed to their partnership, and it was worth at least 50 percent. If he had been on his own, Wozniak might not have progressed beyond handing out free schematics. After they demonstrated the computer at a Homebrew meeting, Jobs was approached by Paul Terrell, the owner of a small chain of computer stores called The Byte Shop. After they talked, Terrell said, “Keep in touch,” handing Jobs his card. The next day Jobs walked into his store barefoot and announced, “I’m keeping in touch.” By the time Jobs had finished his pitch, Terrell had agreed to order fifty of what became known as the Apple I computer. But he wanted them fully assembled, not just printed boards with a pile of components.

…

In March 2003 blog as both a noun and a verb was admitted into the Oxford English Dictionary. 44. Tellingly, and laudably, Wikipedia’s entries on its own history and the roles of Wales and Sanger have turned out, after much fighting on the discussion boards, to be balanced and objective. 45. Created by the Byte Shop’s owner Paul Terrell, who had launched the Apple I by ordering the first fifty for his store. 46. The one written by Bill Gates. 47. Gates donated to computer buildings at Harvard, Stanford, MIT, and Carnegie Mellon. The one at Harvard, cofunded with Steve Ballmer, was named Maxwell Dworkin, after their mothers. 48.

Founders at Work: Stories of Startups' Early Days

by

Jessica Livingston

Published 14 Aug 2008

Wozniak and Steve Jobs founded Apple Computer in 1976. Between Wozniak’s technical ability and Jobs’s mesmerizing energy, they were a powerful team. Woz first showed off his home-built computer, the Apple I, at Silicon Valley’s Homebrew Computer Club in 1976. After Jobs landed a contract with the Byte Shop, a local computer store, for 100 preassembled machines, Apple was launched on a rapid ascent. Woz soon followed with the machine that made the company: the Apple II. He single-handedly designed all its hardware and software—an extraordinary feat even for the time. And what’s more, he did it all while working at his day job at Hewlett-Packard.

…

We did use the garage at his place—we had a lab bench there and we would plug in the PC boards of the Apple Is and test them on a keyboard. If they worked, we’d put them in a box. If they didn’t work, we’d fix them and put them in a box. Eventually, Steve Steve Wozniak 45 would drive the boxes down to the Byte Shop in Mountain View or wherever and get paid, in cash. We had the parts on credit and we got paid in cash. That was the only way we could do the Apple Is. Livingston: So you’d keep self-funding? Wozniak: Yes, we kept self-funding and we probably built up a bank account of about $10,000. Not a huge amount, but it was enough to move into an office.

The Dream Machine: J.C.R. Licklider and the Revolution That Made Computing Personal

by

M. Mitchell Waldrop

Published 14 Apr 2001

Not only were new brands of machines flooding the market by the dozens, if not by the hundreds, there were also users' groups for every microcomputer imaginable, as well as pan-micro groups such as the legendary Homebrew Computer Club, which held its first meeting in a Palo Alto garage in March 1975. There were magazines such as Byte, which debuted in August 1975, and the software periodical Dr. Dobbs Journal of Computer Calisthenics and Orthodontia (motto: "Running Light without Over- byte"), which published its first issue in 1976. There were specialty stores like the Byte Shop and ComputerLand, the latter soon to be a nationwide chain. And increasingly there were young entrepreneurs who were beginning to imagine that consumers might want to use these machines-people who weren't hobbyists, who weren't technically sophisticated, and who had no desire to pick up a soldering iron.

…

., 68-69, 140 Babbage, Charles, 38, 103 backups, development of, 234 Backus,John, 165, 171n Backus-Naur form notation, 171n Ballistics Research Laboratory, 44,45,425 Balzer, Bob, 282 "Bandwagon, The" (Shannon), 94 Baran, Paul, 276, 278, 469 Barker, Ben, 299, 302 BASIC, 190, 292, 431 BasIc Input/Output System (BIOS), 435 INDEX 491 BasIc Operatmg System (BOS), 252 batch processing, 143-44, 154, 163,171,180,190,202,232, 233,246,254,292,318 Bateson, Gregory, 57, 83 Bausch and Lomb, 347 BCC 500, 346, 350, 364 Bechtolshelm, Andreas, 438n-39n behavlOnsm, 70-74, 96-97, 128, 130-32, 139 BehavIOrism (Watson), 70 Bell, Gordon, 248, 361, 439, 461 Belleville, Bob, 448, 449 Bell Systems TechmcalJournal, 74 Bell Telephone Laboratones, 34-35, 37, 43, 54, 75, 76, 77, 80,101, 118, 161n, 235,252, 253,295,315,417 Bennet, Joe, 107 Beranek, Leo, 13-14, 17, 105, 150,158,179,194,237 Berkeley, U mverslty of Califorma at,211,212,239,256,25 262,264,285,427 Berkeley Computer Corporation, 346 Berkeley System Distribution 4.2 Umx, 427 Berlin, Technical University of, 313 Berlm, Umverslty of, 41 Berlin Blockade, 93, 99 Berners-Lee, Tim, 465-66 Berry, Clifford, 37 Bethe, Hans, 42 Bigelow, JulIan, 54, 86-87 Bma, Enc, 466n bmary anthmetlc, 33, 34-36 binary choice, 32 bmary numbers, 36-37 BIOS (BasIc Input/Output Sys- tem), 435 Blrkenstock, James, 116 "bit," 81 bit-mapping, 366-68 Bitnet, 457 Bletchley Park, 80 Blue, AI, 266-67, 274, 396-97 Bobrow, Damel, 167, 354, 386, 451 Boggs, David, 375, 381-82, 386, 416 Bohr, Niels, 91 Bolt, Richard, 105, 150 Bolt Beranek and Newman, 3, 114, 150-57, 175, 179, 190, 194,237-38,314,320,360, 376,380,394 and ARPA network, 294-304 BOS (BasIc Operating System), 252 Boston Computer SOCiety, 436 Boston Herald, 20 bounded rationality, 134-37 Bowmar Brain, 428 Brand, Stewart, 388, 421 Bravo, 384, 409 Bncklm, Dan, 315 Bntlsh Postal Service, 275 Broca, Paul, 11 Brooks, Fred, 252 Brown, Gordon, 220 Brownstein, Chuck, 462 Bruner, Jerome, 139 "bug," 40 Bulletin of the Atomic Sczenllsts, 85 Burchard, John, 109, 126-27, 149 Burks, Arthur W., 87 Burmaster, David, 307-8, 316, 317n,455 Bush, Vannevar, 23, 24-31, 34, 46,76,82,185,465 desk library Idea of, 27-29 Differential Analyzer and, 25-26 Individual empowerment Idea of, 28-29 Wiener's Idea rejected by, 29-30 Buslcom, 339 "byte," 246-47 Byte, 433 Byte Shop, 433 C (language), 168,319,426 Califorma Network, 226 Cambndge ProJect, 315-17 Cambndge University, 100 Cape Cod System, 115 Card, Stuart, 346, 354, 363, 383 Carlson, Chester, 333 Carnegie Institution, 26-27 Carnegie Mellon U mverslty, 241, 258,340,361,438 Carnegie Tech, 134, 190,209, 239-41,313 cathode-ray tube, 87, 113, 242 Center for Cogmtlve Studies, 139-40 Central IntellIgence Agency (CIA), 316, 339 central processing umt (CPU), 60, 164 Cerf, Vinton, 282, 301, 302, 321, 322-23, 327, 328-29, 331, 375,378-80,381,398,41 420,456 CERN, 465 Ceruzzl, Paul, 429 chaos theory, 124 character generators, 362 Cheadle, Ed, 358, 359 Chomsky, Noam, 130-33, 138 chunklng, 130, 132, 138 Church, Alonzo, 52, 53, 172n CIA (Central Intelligence Agency), 316, 339 CircUits, electronic, 32-33 circuit sWitching, 272 CISCO Systems, 464 Clapp, Verner, 185 Clark, James, 419, 466n Clark, Wesley, 141, 143-45, 147, 149,152,173,188-90,218, 261, 262, 273-74, 337, 341, 343,345, 369n Clarke, Arthur C., 76 Cleven, Buck, 224-25, 256 Cltnton, BIll, 461 clocks, In computers, 234 coaxial cable, 374 Cobol, 168, 246 cognitive neurOSCience, 97, 139-40,181 COgrtlllve RevolutIOn m Psychology, The (Baars), 68 cognItive SCIence, 57, 96-97, 240 Cohen, Danny, 282 command and control systems, 176,200-203,207-8, 217-18,276 Commodore PET, 434 common sense, formaltzlng of, 162 commUnIcation, 23, 56, 76, 82, 184 architecture of, 77 channels of, 78, 79 five stages of, 77-78 see also Information theory communIcation englneenng, 82 CommumcatlOns of the ACM, 240, 426 compact discs, 79 Compaq, 441n Compatible Tlme-Shanng Sys- tem (CTSS), 190-91, 221-24,228-36,243,248, 319,414 as open system, 231 reltabIlIty of, 233-34 compilers, 165 Complex Computer, 35-36, 37 complex mformatlon processing, 136-37, 162 complex numbers, 35 compressIOn algonthms, 267 Compton, Karl, 18, 26, 103 CompuServe,424 492 INDEX "Computer as a CommUnIcation Device, The" (Llckltder and Taylor), 264 "Computer In the University, The" (Perils), 180 ComputerLand, 433 computers: analog, 25, 30, 101 business applications for, 188, 447-48 clocks In, 234 digital, 30, 31, 98, 103 emotional Impact of, 64 human symbiosIs with, 4-6, 147-50, 175-86, 194-95, 254,255,262,288,354,363 languages, see languages, com- puter laptop, 387 memory In, see memory, 10 computers microcomputers, 428-38, 452-53 minicomputers, 334, 365, 424, 425,431 notebook, 361-62, 367 open architecture of, 422-23 from operator-supervised to programmable, 37-40 perceptions of, 142-44 personal, 4-5, 116n, 188, 189, 257,261-62,343,358-59, 360,363-70,386,428-3 445-48 real-time, 101-5 and revolt agamst mamframe, 421-28 senal vs. parallel, 61 supercomputers, 425 theory of, 33-34, 47-48, 88-92 von Neumann's functIOnal units of, 60 Wiener's push for, 29-30 see also specific computers Computers and the World of the Future (Licklider), 180 computer SCience, 86 Computer SCIences Laboratory (CSL), 340, 344-45, 351-55, 363,368,370,387,401,444, 450-51 computer utIlities, 292-93, 343, 433 "Computing Machinery and Intelligence" (Tunng), 122 concept manIpulation, 215 Connection Machine, 419 control, Wiener's theory of, 23, 56, 82 Control Data Corporation, 249 Conway, Lynn, 419 Cooper, Robert, 457 cooperative modelIng, 184 Corbato, Fernando, 165-66, 173-75, 190-92, 207, 208, 221,228-30,233-36, 243-47, 249, 250, 251, 253, 25 268, 304,312-14,470 Cornerstone, 436 Corporation for NatIOnal Research InItiatives, 457 Cosmic Cube, 419 Couleur, John, 250 CouncIl on Library Resources, 185 Courant, Richard, 21 Courant Institute, 169 CP/M, 434-35 Crawford, Perry, 102 Cray, Seymour, 249, 425 Cnck, FrancIs, 89 Crocker, Steve, 282, 283-87, 300-303,321-22,372, 394-95,397 Crowther, WIll, 297, 298-301, 321 CRT displays, 347-48 CSL, see Computer SCIences Lab- oratory CSnet, 458-59 CTSS, see Compatible Tlme- Shanng System Curne, Malcolm, 398-99 Curry, Jim, 345 cybernetICs, 82-93, 98, 121-26, 160-61 Cybernetics (Wiener), 84, 91, 92, 121 response to, 95-96 Dahl, Ole-Johan, 357 DanIel, Stephen, 427 DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency), 396 Dartmouth College, 138, 159-60, 167, 190, 292 Data General, 334, 365, 424, 431 DatamatIOn, 292 data vlsualtzatlon, 267 Davies, Donald, 275, 278 dBase, 435 D D R&E (duector of defense research and engmeenng), 198,402 Dealer Meetmgs, 353-54 Dealers of Llghtnmg (HIltzlk), 441 DEC (Digital EqUIpment Corpo- ratIOn), 147, 154-57, 175, 188,210,248,251,261,292, 313,334,350,416,421-24, 428, 431, 439-40, 440n-41n, 454 deCiban, 80 decldabtllty problem, 48-53, 58 decimal math, 34-36 DECnet,416 DECSYSTEM 10,434 DEC Systems Research Center, 451 Defender antiballIstic-missile program, 278 Defense Advanced Research Pro- Jects Agency (DARPA), 396 Defense CommunIcations Agency, 277, 406 Defense Department, U.S., 1-6, 101, 198, 199,224,266, 278-79,280-81 air defense and, 100, 104, 112, 115 Deltamax, 113-14 Dendral, 397-98 DennIs, Jack, 187, 221, 244, 250 Dertouzos, Michael, 412-13, 416-17,453 Descartes, Rene, 22 descnptlon copier, 88-89 desktop publIshmg, 392 Deutsch, Peter, 346 Differential Analyzer, 24, 25-26, 31,32,37,44,62 Digital Research, 434-35 direction centers, 117, 119 director of defense research and englOeenng (DDR&E), 198, 402 Disk Operatmg System (DOS), 252,435 Disney, Walt, 338 displays, 242, 359, 366, 402 desktop, 178-79 DNA, 89 Dr.

Commodore: A Company on the Edge

by

Brian Bagnall

Published 13 Sep 2005

It was big and thick on shiny stock but it was hardly polished. The early days were like the Wild West frontier.” In college, Yannes earned his tuition by assembling computers. “One of the things I would do to earn some money was to build computer kits for the science lab or the computer lab,” he recalls. “At a local Byte Shop, I built these systems and got them working. There were a lot of people coming in who wanted computers but they weren’t interested in building their own and particularly debugging it because a lot of them weren’t very reliable designs back then.” Using some of his earnings, Yannes purchased a more expensive synthesizer kit from PAiA.