Blood, Iron, and Gold: How the Railways Transformed the World

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 1 Mar 2010

The Germans briefly considered the idea of an extension to meet the Cape to Cairo and run a line through to the Congo Free State, but realized there was no economic justification since the rich minerals from Katanga would never be transported in an easterly direction. Or at least not until sixty years later, when the Chinese took an interest, building the Tazara Railway to enable Zambia to export its copper without going through South Africa or Rhodesia. Sections of the line are actually on the route the Cape to Cairo might have taken had the Kaiser not blocked its path, and as a result the dream of a Cape to Cairo railway is not entirely dead.

…

.), The Great Trains, Crown Publishers, New York, 1973, p. 149. 16 The colour of Britain’s colonies on maps of the day. 17 George Tabor, The Cape to Cairo Railway and River Routes, Genta Publications, 2003, p. 3. 18 Quoted in ibid., p. 11. 19 Ibid., p. 83. 20 These friendly looking herbivore hippos are, in fact, the biggest killer in Africa today as they are incredibly fierce if they feel threatened. 21 Quoted in George Tabor, The Cape to Cairo Railway and River Routes, p. 87. 22 Ibid., p. 85. 23 Ibid., p. 85. 24 Now Mutane. 25 George Tabor, The Cape to Cairo Railway and River Routes, p. 95. 26 Now Zimbabwe. 27 Technically, the second Boer War as there had been a brief one in 1880–81 when the Boers successfully resisted a British attempt to take over the Transvaal.

…

The second war lasted to 1902 and ultimately resulted in the creation of the Union of South Africa. 28 George Tabor, The Cape to Cairo Railway and River Routes, p. 150. 29 From his journal, quoted in George Tabor, The Cape to Cairo Railway and River Routes, p. 175. 30 Now in the Democratic Republic of Congo. 31 Now Ilebo. 32 Now Shaba. 33 Then Portuguese East Africa. 34 Although it was not until a battle further south in November 1899 at Umm Diwaykarat that the Mahdi’s forces were finally defeated. 35 About which he wrote a book, The River War: An Historical Account of the Reconquest of the Sudan, Longmans, Green & Co., 1899. 36 George Tabor, The Cape to Cairo Railway and River Routes, p. 237. 37 M.F.

Crossing the Heart of Africa: An Odyssey of Love and Adventure

by

Julian Smith

Published 7 Dec 2010

“In the course of a chequered career I have seen many unwholesome spots,” he wrote in From the Cape to Cairo, “but for a God-forsaken, dry-sucked, fly-blown wilderness, commend me to the Upper Nile; a desolation of desolations, an infernal region, a howling waste of weed, mosquitoes, flies, and fever, backed by a groaning waste of thorn and stones—waterless and waterlogged. I have passed through it, and have now no fear for the hereafter.” Ewart Scott Grogan died quietly on August 16, 1967, in Cape Town, aged ninety-two. His grave faces Table Mountain, the starting point of his great African adventure so many years before. Grogan’s Cape-to-Cairo trek was the last great journey of the Golden Age of Exploration in Africa.

…

Her family had dismissed him as a ne’er-do-well who would be unable to keep their daughter in the manner to which they thought she should be accustomed. Grogan banked on the fame (if not the fortune) that a dramatic adventure would bring him to persuade them to reconsider. That was it: three sentences, nothing more. But I had to know more. I tracked down the few biographies of Grogan and his firsthand account of the journey, From the Cape to Cairo. The more I read, the more the adventure and romance of his story captivated me. The proud tradition of men doing crazy things for love goes back at least to the Trojan War, triggered when Paris eloped with Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world (and someone else’s wife). A seventeenth-century Mughal emperor built the Taj Mahal as a memorial to his favorite wife, who had died in childbirth.

…

The captain spent more time in his bunk than piloting the ship, Grogan wrote. “His only anxiety was lest he should oversleep himself and miss a meal.” They had left Kituta on April 2, 1899, six days after the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi sent the first wireless message across the English Channel. One of the official goals of the journey, scouting a route for a Cape-to-Cairo telegraph line, was on the verge of becoming obsolete. Grogan seemed to be going back in time, but the outside world was surging forward. The Good News shoelaced from shore to shore as it steamed north up the lake. At a French mission station on the eastern side, the passengers were paddled ashore in forty-foot dugout canoes, and the Catholic fathers filled the canoes to bursting with fresh fruit, beef stew, and Algerian wine.

The scramble for Africa, 1876-1912

by

Thomas Pakenham

Published 19 Nov 1991

Belgium was thrown a picturesque bone: Ruanda-Urundi, hidden away beside the Mountains of the Moon. None of the Powers grew fat on the ex-German colonies. Apart from little Togo, the colonies had all needed large hand-outs from Berlin. Of course the changes seemed to make sense on the map. Cape-to-Cairo, the ‘all-red’ route across Africa, was now a reality. But the great trans-African railway, the stuff of Rhodes’s Cape-to-Cairo dream, did not materialize. Africa was too poor for anything but a potholed motor track across its spine. Prestige apart, the chief benefit for Britain lay in improved security for her Empire. Bismarck had mischievously stuck his four German colonies like thorns into the side of four isolated British territories: the Gold Coast (later Ghana), Nigeria, South Africa and British East Africa (Kenya).

…

‘Well: all I can say is, it is a very extraordinary proceeding.’4 Extraordinary the ideas certainly were, in every sense. Inspired by Salisbury, The Times piece is the clearest sketch we have of Salisbury’s positive ideas for Africa. There were two globe-rocking proposals that neatly coincided. The first would soon be famous as ‘Cape-to-Cairo’: a plan to bridge the 3,000-mile gap between British South Africa and British-controlled Egypt. This would mean taking the Sudan, Equatoria (‘Emin’s territory’, Johnston called it), a corridor west of German East Africa, and then the whole ‘vacant’ area north of the Transvaal, including ‘Zambezia’, and the African territories sandwiched between Angola and Mozambique.

…

In 1876 Lord Carnarvon had proposed to cede Gambia to the French, but it had proved too much for Parliament to stomach. There would be even more parliamentary opposition now, with the Conservatives dependent on the favours of the Liberal Unionists, and the Irish Party hell-bent on obstruction. On the other hand, the much more radical ‘Cape-to-Cairo’ idea was not as vulnerable in Parliament, simply because it did not involve an exchange of territory. The plan had far more to commend it in Lord Salisbury’s eyes as well. Above all, it fitted his overriding diplomatic aims in Africa. They must protect the Empire by protecting Egypt, which meant extending the Empire 2,000 miles south of the Mediterranean, to the head-waters of the Nile.

Engines of War: How Wars Were Won & Lost on the Railways

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 1 Nov 2011

Since Wadi Haifa could be reached by ships on the Nile from Luxor, the line was the last link in the line of communication between the two capitals, Cairo and Khartoum. However, this time the scale of ambition was far greater as not only was the line planned to be a military railway enabling the British to retake Sudan from the Mahdis, but it was also part of the ambitious Cape to Cairo project promoted by Cecil Rhodes to build a railway line across the whole continent. After much prevarication following the disaster of Gordon’s fall, Herbert (later Lord) Kitchener, then the commander-in-chief of the Egyptian Army, obtained permission from the British government to build the line in order to quell the Mahdi rebellion once and for all.

…

In a long section in the book, he concludes that while bravery and discipline may often result in unexpected victories, ‘in savage warfare in a flat country the power of modern machinery is such that flesh and blood can scarcely prevail and the chances of battle are reduced to a minimum. Fighting the Dervishes was primarily a matter of transport. The Khalifa was conquered on the railway.’16 At the other end of the putative but never completed Cape to Cairo,17 the railways were also about to play a major, if very different, part in a war. The Boer War18 was another eminently preventable clash which started off with patriotic cheers, and ended with much soul searching about the state of the British Empire. At the turn of the century, the current Republic of South Africa was divided into four territories: Natal and the Cape Colony, which were British colonies, and two Boer republics, the Transvaal and Orange Free State.19 To the north, Rhodes had created the British South Africa Company, which became Rhodesia.

…

In addition to opening up markets and ensuring sources of supply of minerals and agricultural produce, railways unified political territories4 and made the job of policing an area far easier. Railways, it was recognized, were both the economic lifeline of remote regions and the physical demonstration of military domination by the colonial power. The Russo-Japanese War had grown precisely out of a struggle between competing powers and in Africa the efforts by Rhodes to build a Cape to Cairo railway had almost resulted in a war with the French over their rival plans in the immediate sub-Saharan area. As a historian of the Middle East in the pre-war period suggests, ‘railways having become so important, it was soon merely sufficient for one nation to announce the preliminary plans for a new railway to engender suspicion, hostility and jealousy in other powers’.5 The collapse of the Ottoman Empire offered a country such as Germany, which had come rather too late to establish direct control of huge swathes of land, the opportunity to carve out an area where it could exert economic domination.

Empire: What Ruling the World Did to the British

by

Jeremy Paxman

Published 6 Oct 2011

In 1887, for example, he told the House of Assembly in Cape Town that ‘the native is to be treated as a child and denied the franchise … We must adopt a system of despotism in our relations with the barbarians of South Africa.’ It is as redundant to wonder whether Rhodes was a racist as to question whether he wore a moustache on his self-satisfied face, for the evidence is overwhelming. When he plotted his Cape-to-Cairo railway or, as prime minister of the Cape, cast lustful imperial eyes on the lands beyond the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers he was not thinking of the welfare of anyone but ‘the Anglo-Saxon race’. Rhodes – whose African ambitions meant he acquired the inevitable nickname ‘Colossus’ – was an empire-builder on the scale of Clive of India, and when he wanted to exploit the mineral rights obtained from the Matabele king, Lobengula (in exchange for a promise of money, a thousand rifles and a boat), the British government gave him a chartered company similar to the old East India Company.

…

As he approached Fashoda on 18 September 1898, the identity of the intruders was settled, for he was greeted by soldiers carrying a letter from a Major Jean-Baptiste Marchand. It had the impertinence to welcome him, in the name of France. The British Empire in Africa was hung on a north–south axis, along the lines of Cecil Rhodes’s dream of a railway line from the Cape to Cairo. French possessions in Africa were concentrated on the Atlantic coast of west Africa, although the French had recently taken control of the fly-blown but strategically important territory of Djibouti on the Horn of Africa. Paris dreamed of linking the two and Fashoda was the point where the British north–south line crossed the French east–west line.

…

.* The site chosen for his headquarters was called the Hill of Evil Counsel. The spoils of war may have broadened the empire. But the effects of war weakened it. It was true that the acquisition of most of what had been German East Africa almost made possible Cecil Rhodes’s dream of a railway line from the Cape to Cairo on British territory, should anyone ever get around to building it. Lord Curzon, who had served in Lloyd George’s War Cabinet, sighed that ‘The British flag never flew over more powerful or united an empire than now.’ Figures like Curzon expected that the experience of shared hardship might have deepened the unity of empire.

Diamonds, Gold, and War: The British, the Boers, and the Making of South Africa

by

Martin Meredith

Published 1 Jan 2007

He proposed that Frere should go out to the Cape ‘nominally as Governor, but really as the Statesman who seems to me most capable of carrying my scheme of Confederation into effect’. Frere’s reward was to be appointed the first governor-general of a new British dominion. But Carnarvon’s ambition did not stop there. He began to fashion the idea of a ‘Cape to Cairo’ policy, envisaging even greater swathes of Africa coming under British control, out of reach of other European powers. In a letter to Frere on 12 December 1876, he wrote: I should not like anyone to come too near us either on the South towards the Transvaal, which must be ours; or on the North too near to Egypt and the country which belongs to Egypt.

…

Livingstone’s lonely death in central Africa in 1873 while searching in vain for the source of the Nile unleashed a burst of imperial sentiment that mixed a world power’s responsibility for trusteeship with a strong dose of economic opportunism. Disraeli’s surge of imperial activity during the 1870s - acquiring Cyprus, Fiji and a large bulk of shares in the Suez Canal - won popular support. In a pamphlet written in 1876, Edwin Arnold, editor of the Daily Telegraph, used the phrase ‘from the Cape to Cairo’ to demonstrate the scale of imperial ambition. Queen Victoria herself was particularly pleased when, at her own suggestion, Parliament in 1877 bestowed on her the title of Empress of India. That same year, at the age of twenty-four, after completing his first full year at Oxford, Rhodes drew up what he later called ‘a draft of some of my ideas’, giving it the title ‘Confession of Faith’.

…

While conceding that other European powers had ‘legitimate’ interests in Africa - the French and the Italians in north Africa, for example - he argued that it was essential for the sake of British commerce that Britain should extend its control ‘over a large part of Africa’. Picking up Edwin Arnold’s original idea for a ‘Cape-to-Cairo’ policy, he urged the linking of Britain’s possessions in southern Africa with its sphere in east Africa and the Egyptian Sudan ‘by a continuous band of British dominion’. Impressed by Johnston’s zeal, Salisbury appointed him as consul in Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique). His remit was to secure for Britain territory in the interior which Salisbury was interested in acquiring by signing treaties with African chiefs before the Portuguese or the Germans or the Belgians got there.

The Rules Do Not Apply

by

Ariel Levy

Published 14 Mar 2017

I know (and he suspects) that I have come all this way for an encounter that isn’t worth having, and a story that isn’t worth telling, at least not by me. I have made myself ridiculous. My losing streak continues. And yet. “I have never seen the great migrations. I’ve got a really old Land Rover that I’ve owned since 1986 (and it was old when I bought it). My dream has been to nurse it up through Africa one day—Cape to Cairo, or some version of that epic. Not that it is very reliable; I insist on doing all my own mechanical work, and that is so emphatically not a good idea. But breaking down can be very rewarding. Zen and the art of…that kind of thing.” Here is a third fantasy: I go. My story is real and I believe in my ability to tell it well.

…

He is like a big brother, like Neil Reardon or my editor John Homans (but with silver hair and blue eyes and stories about riding a horse to work in the Transkei to do Caesareans by candlelight). We keep writing to each other after I’ve finished my story and returned home. We are strangely important to each other for the rest of our lives. In this fantasy, he comes to visit me in New York from time to time. A few years after our first meeting, I go with him from the Cape to Cairo in his Land Rover. My kid comes, too. 30 Something is happening. Something very small and very new is sending up a shoot inside of me. It’s a sprout of surrender that feels somehow indistinguishable from safety. It is not emanating from a plan. For the first time in my life, I have no plan.

Better Than Fiction

by

Lonely Planet

Truth be told, he was chasing a woman, a relationship that (like so many born of travel) didn’t work out in the real world. To get his mind off the breakup, Yogerst began taking ever-longer and riskier trips – backpacking solo through the African bush, hitchhiking to northern Namibia, where a furious border war was then in progress, and then undertaking an epic Cape-to-Cairo journey that included his ride on the Scarface Express. That was the start of thirteen years overseas, during which Yogerst worked as a newspaper reporter, magazine editor and freelance writer on three continents. He returned to his native California in 1995 and continues to write about his travels across the globe.

…

Scarface and his men, speaking in Arabic, pointing up and down the street, no doubt trying to figure out which way we had fled. The sergeant barked orders and they began to fan out in different directions. One of them looked around at the café where we were hunkered down, took a tentative step our way … . . . . . . . . . . . It was my ‘year of living dangerously’ in Africa, an overland journey from Cape to Cairo by any means I could find or afford – trains, boats, buses, walking, hitching. I knew the 2000-mile leg between Nairobi and Khartoum would be the most difficult because there wasn’t any public transport and not much in the way of private vehicles that might be willing to give me a ride. Southern Sudan wasn’t an independent nation yet and the country was still plagued by its long civil war.

Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World

by

Niall Ferguson

Published 1 Jan 2002

While some responded by retreating into a defiant jingoism, others were assailed by doubts. Even the most gilt-edged generals and proconsuls exhibited symptoms of what is best described as decadence. And Britain’s most ambitious imperial rival was not slow to scent the opportunity such doubts presented. Cape to Cairo In the mid-nineteenth century, apart from a few coastal outposts, Africa was the last blank sheet in the imperial atlas of the world. North of the Cape, British possessions were confined to West Africa: Sierra Leone, Gambia, the Gold Coast and Lagos, most of them left-overs from the battles for and then against slavery.

…

Without any advantages of position we should have had all the dangers inseparable from its defence. In other words, it was only worth acquiring new territory if it strengthened Britain’s economic and strategic position. It might look well on a map, but the missing link that would have completed Rhodes’s ‘red route’ from the Cape to Cairo did not pass that test. As for those who resided in Africa, their fate did not concern Salisbury in the slightest. ‘If our ancestors had cared for the rights of other people,’ he had reminded his Cabinet colleagues in 1878, ‘the British Empire would not have been made.’ Sultan Bargash was soon to discover the implications of that precept.

…

One by one the nations of Africa were subjugated – the Zulus, the Matabele, the Mashonas, the kingdoms of Niger, the Islamic principality of Kano, the Dinkas and the Masai, the Sudanese Muslims, Benin and Bechuana. By the beginning of the new century, the carve-up was complete. The British had all but realized Rhodes’s vision of unbroken possession from the Cape to Cairo: their African empire stretched northwards from the Cape Colony through Natal, Bechuanaland (Botswana), Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), and Nyasaland (Malawi); and southwards from Egypt, through the Sudan, Uganda and East Africa (Kenya). German East Africa was the only missing link in Rhodes’s intended chain; in addition, as we have seen, the Germans had South West Africa (Namibia), Cameroon and Togo.

Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives

by

Siddharth Kara

Published 30 Jan 2023

He subsequently described the Congo Free State as the “vilest scramble for loot that ever disfigured the history of human conscience” and a land in which “ruthless, systematic cruelty towards the blacks is the basis of administration.” The year after Heart of Darkness was published, the first known person to walk the length of Africa from the Cape to Cairo, E. S. Grogan, described Leopold’s territory as a “vampire growth.” In The Casement Report (1904), Roger Casement, British consul to the Congo Free State, described the colony as a “veritable hell on earth.” Casement’s indefatigable ally in bringing an end to Leopold’s regime, E. D. Morel, wrote that the Congo Free State was “a perfected system of oppression, accompanied by unimaginable barbarities and responsible for the vast destruction of human life.”4 Every one of these descriptions equally conveys conditions in the cobalt mining provinces today.

…

“Cobalt Market Review 2022.” https://www.dartoncommodities.co.uk/market-research/. De Witte, Ludo. (2003). The Assassination of Lumumba. Verso Books. Brooklyn, NY. Franklin, John Hope. (1985). George Washington Williams: A Biography. University of Chicago Press. Chicago. Grogan, Ewart S. (1900). From the Cape to Cairo. Hurst & Blackett. London. Helmreich, Jonathan. (1986). Gathering Rare Ores: The Diplomacy of Uranium Acquisition, 1943–1954. Princeton University Press. Princeton, NJ. Hitzman, M. W., A. A. Bookstrom, J. F. Slack, and M. L. Zientek. (2017). Cobalt—Styles of Deposits and the Search for Primary Deposits.

Heaven's Command (Pax Britannica)

by

Jan Morris

Published 22 Dec 2010

Goldie himself, who claimed to be able to hypnotize people, and carried a phial of poison in his pocket in case he was suddenly struck with an incurable illness, disclaimed all such ambitions, and regarded the scramble for Africa as ‘a game of chess’. 1 Which Rhodes never set eyes on. 2 Rhodes was not the first to foresee a British Cape-to-Cairo corridor. Gladstone himself direly predicted it, five years before Tel-el-Kebir, as an inevitable consequence of intervention in Egypt—‘be it by larceny or be it by emption’. 1 In fact the British north-south corridor was not achieved until after the first world war, when Tanganyika became a British mandated territory, and the Cape-to-Cairo railway was never completed. Nor, except within South Africa, did the British ever control an east-west corridor across Africa. 1 Whom we last met hoisting the flag in Fiji and accepting Cakobau’s war-club for the Queen. 1 Nowadays one may follow the route of Jameson’s raid fairly exactly by car, the cross-road stores one sees often being the sites of his secret supply depots—in those days most of the store-keepers were British.

…

There were spoils still to come, civilizing duties yet to be fulfilled, and activists in all the imperial countries eyed the continent hungrily, some imagining its map swathed with green from coast to coast, some envisaging slabs of Prussian blue, and many conceiving one long strip of British red, veld to delta, Cape to Cairo. Sometimes the Powers seemed likely to clash, as their traders, missionaries or troops advanced into the continent, and often diplomatic exchanges between the chanceries of Europe were prompted by episodes on distant reaches of tropic rivers, or in steamy unmapped banyan swamps: but in 1884 Bismarck, Chancellor of the new Federal Germany, perhaps foreseeing the inflammatory properties of Africa, invited all the leading nations of the world to confer in Berlin about its future.

The Land Grabbers: The New Fight Over Who Owns the Earth

by

Fred Pearce

Published 28 May 2012

Its first director was John Hanks, a veteran of WWF in Africa, who had taken responsibility for Operation Lock when it was exposed in 1991. This foundation has initiated plans for cross-border parks involving every southern African country as far north as Tanzania, and has treaties creating them that involve South Africa, Mozambique, Botswana, Namibia, and Zimbabwe. One journalist hailed it as “an ecological Cape to Cairo dream.” Its main accomplishment on the ground so far is the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park, essentially a cross-border extension of the Kruger Park in South Africa into Mozambique and Zimbabwe. It covers 8.5 million acres. The parks authorities say that it is trying, in Hanks words, to “right the wrongs of the past,” including those from the apartheid era.

…

Virgin boss Branson—yes, him again—owns the 25,000-acre Sabi Sands, one of nine private game reserves that circle the 5-million-acre Kruger National Park, sharing its wildlife. Nicky Oppenheimer, chairman of the de Beers diamond empire founded by Cecil Rhodes, who once dreamed of an African land grab from the Cape to Cairo, has spent some of his $3 billion fortune on the 250,000-acre Tswalu Kalahari game reserve, South Africa’s largest, in the north of the country. And, in case you thought we could get through a chapter without mentioning a Gulf investor, the 60,000-acre Shamwari game reserve in the south, near Port Elizabeth, is owned by Dubai World, a real-estate-grabbing arm of the government of Dubai, which also has luxury beach resorts in Djibouti, Zanzibar, and the tiny Indian Ocean island nation of Comoros.

Lonely Planet Cape Town & the Garden Route (Travel Guide)

by

Lucy Corne

Published 1 Sep 2015

oCape Union Mart Adventure CentreOUTDOOR GEAR ( MAP GOOGLE MAP ; www.capeunionmart.co.za; Quay 4, V&A Waterfront; h9am-9pm; gNobel Square) This emporium is packed with backpacks, boots, clothing and practically everything else you might need for outdoor adventures, from a hike up Table Mountain to a Cape-to-Cairo safari. There's also a smaller branch in Victoria Wharf, as well as in the Gardens Centre and Cavendish Square malls. oEverard ReadART ( MAP GOOGLE MAP ; %021-418 4527; www.everard-read-capetown.co.za; 3 Portswood Rd, V&A Waterfront; h9am-6pm Mon-Fri, to 4pm Sat; gNobel Square) Very classy gallery showcasing the best of contemporary South African art, including works by the contemporary realist John Meyer, and Velaphi Mzimba, who works in mixed media.

…

The climate obviously agreed with Rhodes, as he not only recovered his health but went on to found the De Beers mining company (which in 1891 owned 90% of the world’s diamond mines) and become prime minister of the Cape at the age of 37, in 1890. As part of his dream of building a railway from the Cape to Cairo (running through British territory all the way), Rhodes pushed north to establish mines and develop trade. He established British control in Bechuanaland (later Botswana) and the area that was to become Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe). His grand ideas of empire went too far, though, when he became involved in a failed uprising in the Boer-run Transvaal Republic in 1895.

Happy Valley: The Story of the English in Kenya

by

Nicholas Best

Published 9 Aug 2013

Grogan was to remain active in Kenya politics from the turn of the century right through to the 1960s. He had first heard about Africa while an undergraduate at Cambridge, just before being sent down for locking a goat in a don’s rooms. Later he had set out to walk the length of the continent, from the Cape to Cairo. By his own account, he had fallen in love with a girl and made the journey to prove his worth to her father. By other accounts, the girl was just a cover and he was on a mission for the British secret service, keeping an eye on French ambitions in Africa. Whatever the truth, Grogan managed to complete his extraordinary journey, so achieving, as Cecil Rhodes pointed out, ‘that which the ponderous explorers of the world have failed to accomplish’.

The Ages of Globalization

by

Jeffrey D. Sachs

Published 2 Jun 2020

title=File:Colonial_Africa_1913_map.svg&oldid=367487165 (accessed October 27, 2019). Anglo-American Hegemony By the end of the nineteenth century, Britain was first among the imperial powers, with Queen Victoria reigning over the British Isles, India, Burma, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Malaya, much of Africa (“Cape to Cairo”), New Guinea, and dozens of islands and smaller possessions around the world. Many of these served as fueling stations for the Royal Navy, which had unrivaled dominance over the oceans. The British navy, by far the most powerful in the world, policed the sea lanes of the Indian Ocean that connected Britain and India through the Suez Canal (which opened in 1871).

To the Edge of the World: The Story of the Trans-Siberian Express, the World's Greatest Railroad

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 4 Aug 2014

Masons, most of whom were Italian, could earn up to 100 roubles (around £10) per month by working hard, an excellent wage at the time. It was, inevitably, dangerous work. The death rate, for which the best estimate is two per cent, may be shocking in today’s terms, but compared favourably with other contemporary massive projects, such as construction of the (never completed) Cape to Cairo railway or the digging of the Panama Canal, when at times it reached thirty per cent. The estimate, however, could be either an underestimate or, equally, an overestimate, as it was subject to inaccuracy in either direction. On the one hand, the Soviet historians who documented the story of the construction of the line after the Revolution tended to exaggerate the harshness of the conditions for their own political ends, seeking to portray the evil regime of the tsar as negatively as possible.

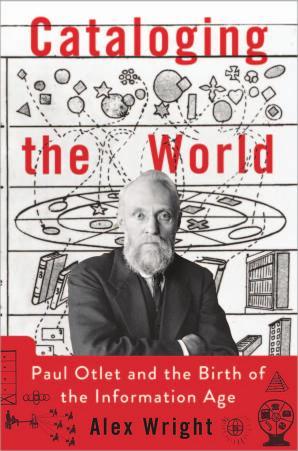

Cataloging the World: Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age

by

Alex Wright

Published 6 Jun 2014

For others, it looked like one big gold mine, both literally and figuratively. For the 50 T he D rea m o f the L ab y rinth increasingly industrialized European powers, the temptations would prove irresistible. After the Congress of Berlin, Great Britain came away with a string of territories stretching in an almost unbroken chain from the Cape to Cairo (including present-day Egypt, Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and South Africa, as well as Nigeria and Ghana); Germany staked its claim in East Africa (Namibia and Tanzania); while France consolidated control over much of western Africa (Chad, Mauritania, and French Equatorial Africa).

Skyfaring: A Journey With a Pilot

by

Mark Vanhoenacker

Published 1 Jun 2015

During those ten long days we came to joke about, and then imagine, a Europe devoid of aviation. How would we get home? The size of Africa, of the world, has never been so apparent to me as it was that week, when the mechanism that brought us across it was so precipitously withdrawn. We mused aloud about various overland routes across Africa. Whatever happened to the Cape-to-Cairo railway? Or might we ride by motorcycle up the west coast of Africa, and wash up, in our torn and dusty uniforms, as exiles in Casablanca, where we would wait for passage to Europe? Our forlorn 747 was parked patiently at Cape Town’s airport. We joked about phoning London to ask for permission to take the cabin crew up for a morning spin over Table Mountain or up along Namibia’s Skeleton Coast or perhaps over Victoria Falls.

The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and Its Solutions

by

Jason Hickel

Published 3 May 2017

The Berlin Conference added considerable impetus to the scramble for Africa. In 1870, only 10 per cent of Africa was under the control of Europeans; by 1914 they had extended their reach across 90 per cent of the continent. Britain controlled a huge swathe of land stretching all the way from the Cape to Cairo, plus Nigeria and a few outposts along the north-west coast. France controlled most of West Africa, Madagascar and part of the equatorial region. Germany took Namibia, Tanzania and Cameroon, while the Portuguese laid claim to Angola and Mozambique, and Belgium ended up with the Congo. Once the dust had settled, only Ethiopia and Liberia remained independent.

Empireland: How Imperialism Has Shaped Modern Britain

by

Sathnam Sanghera

Published 28 Jan 2021

A firm called Mahlatini sells ‘colonial-style safaris’ which ‘offer a taste of a bygone era where decadence, exploration and adventure were the spirit of the day’ (with no mention of the violent racial suppression of the era) and allow you to stay at the Victoria Falls Hotel in Zimbabwe, which apparently has a ‘colonial era … ambience’ reminiscent of a time when, they say, Cecil Rhodes dreamed of building a railway from the ‘Cape to Cairo’ (no mention of Rhodes’ other stated dream, ‘the furtherance of the British empire and the bringing of the whole uncivilized world under British rule, for the recovery of the United States, and for making the Anglo-Saxon race but one empire’). Meanwhile, the Oxford Union flogged a cocktail called the Colonial Comeback during a debate about slavery reparations in 2015, Gourmet Burger Kitchen launched a burger called the Old Colonial in 2016, a London rum bar decided to call itself The Plantation in the same year and, incredibly, in 2020, the East India Company exists as a retail outlet.

Rummage: A History of the Things We Have Reused, Recycled and Refused To Let Go

by

Emily Cockayne

Published 15 Aug 2020

Dawes and his ilk, but instead to the popular entertainer Syd Walker. ‘What would you do, chums?’ 4 Darn (1900s–1930s) One evening in 1917, Lady Agnes Fox, the wife of the civil engineer Sir Francis Fox, watched as strips of paper ascended to the surface of her lily pond. They were saturated portions of blueprints, sections of the Cape-to-Cairo railway that had been separated from their backings. Fished out by Lady Fox, these fabric backings, and not the old drawings, were the real bounty. Earlier that day, her husband had rummaged through the many mounted drawings and maps in his office. Each was reinforced with ‘fabrics of various kinds’, including ‘nainsook, butter muslin, brown Holland, linen, and the like’.

Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization

by

Iain Gately

Published 27 Oct 2001

The British preferred Woodbines, Players and Gold Flake, the Americans Camels, Luckies and Chesterfields. Regrettably, the manufacturers’ war efforts could not keep up with their tastes and the cigarettes in ration packs were often government made. Among other horrors forced upon Commonwealth front line troops in their combat rations were ‘Cape to Cairo’ (made in Egypt), ‘V’, made in India, and ‘RAF’ made in England out of the cigarette butts swept up from cinema floors. Clearly, the pictures on the packets were important to the troops. They were a bond to their homes and past lives as civilians. Cigarettes were almost unique among the disposable items soldiers carried into battlefields, in that they used the same branded product every day in peacetime too.

Land: How the Hunger for Ownership Shaped the Modern World

by

Simon Winchester

Published 19 Jan 2021

For sixty frantic years beginning in the last half of the nineteenth century, thousands of settlers and fortune hunters sailed from chilly northern seaports bent on carving out new countries, on establishing new cities, on displacing inconveniently sited peoples, and on establishing mechanisms of governance and administration that paid little heed to the settled customs of those who remained. Linley Sambourne’s 1892 Punch cartoon of Cecil Rhodes bestriding Africa from the Cape to Cairo has long offered an iconic representation of imperial adventuring across the continent and the wholesale seizing of its lands. An entire ancient continent, stretching from the placid Mediterranean waters off Cairo and Tangier down to the icy chill of the Southern Ocean beyond the Cape of Good Hope, was casually and ruthlessly partitioned.

The Rough Guide to Cape Town, Winelands & Garden Route

by

Rough Guides

,

James Bembridge

and

Barbara McCrea

Published 4 Jan 2018

Justin Fox and Alison Westwood Secret Cape Town. Two local travel writers discover the obscure sights that tell the city's hidden stories. Sihle Khumalo Dark Continent, My Black Arse. Insightful and witty account by a black South African who quit his well-paid job to realize a dream of travelling from the Cape to Cairo by public transport. Ben Maclennan The Wind Makes Dust: Four Centuries of Travel in Southern Africa. A remarkable anthology of fascinating travel pieces, meticulously unearthed and researched. Julia Martin A Millimetre of Dust: Visiting Ancestral Sites. Sensitively crafted narrative that begins on the Cape Peninsula and takes the author, her husband and two children on a journey to important archeological sites in the Northern Cape, raising ethical, ecological and philosophical questions along the way.

After Tamerlane: The Global History of Empire Since 1405

by

John Darwin

Published 5 Feb 2008

The Trans-Siberian Railway (1891–1904), the grandest of all these imperial projects, was meant to turn Russia’s Wild East into an extension of Europe. Other lines were planned on a heroic scale but were left unfinished: the Bagdadbahn to connect Hamburg to Basra (and the Persian Gulf); a ‘Trans-Persian’ railway, linking Europe to India; and Cecil Rhodes’s dream, a Cape to Cairo railway running all the way over a British-ruled Africa. The railway, thought the great British geographer Halford Mackinder, would change world history. The ‘Columbian epoch’, when sea power was everything, was about to give way to a new age of great land empires that commanded vast resources and were virtually impregnable.1 By the end of the century, no part of the world could be considered immune from the transforming effects of the communications revolution.

Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World

by

Margaret Macmillan; Richard Holbrooke; Casey Hampton

Published 1 Jan 2001

The British, who were unable to persuade the Portuguese to play along, found themselves in an awkward position. Belgium would not give up its gains without something in return. Unfortunately, that occupied territory included what looked like the best possible route for the north–south railway linking the Cape to Cairo that British imperialists had so long dreamed of building. 22 On May 7, just after the Germans had received their terms, Clemenceau, Lloyd George, Wilson and Orlando met in a room at Versailles and agreed on the final distribution of mandates over the former German colonies. (They still were haggling over the wreckage of the Ottoman empire in the Middle East.)

Africa: A Biography of the Continent

by

John Reader

Published 5 Nov 1998

Rhodes was already immensely rich; he had gained overall control of the Kimberley diamond mines, and had major interests in the development of the gold-mining industry in the Transvaal. Wealth and ruthless business acumen had brought political influence and fuelled grandiose plans for a British Empire in Africa, stretching from the Cape to Cairo, as magnificent as the Indian Raj, ruled by Rhodes and his men. But first he had to have exclusive rights to the land. And at a time when the European powers were scrambling for spheres of influence around the world, that meant keeping others out. The granting of Protectorate status had kept the Germans out of Bechuanaland; an agreement with Lobengula forestalled Boer and Portuguese ambitions in Matabeleland; but what of Barotseland?

The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor

by

David S. Landes

Published 14 Sep 1999

It too was suppos edly based on rational, material interest, but in fact these late acquisi tions promised little. T o be sure, some o f the lands did contain potentially valuable resources, but these treasures were generally un known at the time of annexation. Much of the land-grabbing was strategic (cf. Cape to Cairo) or preemptive (better mine than yours). 7 EMPIRE AND AFTER 429 Subsequent discoveries were happy surprises and sometimes so changed the incentives as to provoke new fighting for control. Thus southern African gold mines drew a flood of rough-and-ready prospec tors to the Transvaal, spawned disputes with the Afrikaner authorities, brought Britain into the quarrel, and led to the Boer War.