Lotharingia: A Personal History of Europe's Lost Country

by Simon Winder · 22 Apr 2019

find. The theme of this book is defined by one of the most important if accidental moments in European history. Charles I ‘the Great’ (Charlemagne) spent a long and enjoyable career carving out a huge empire across much of north-west mainland Europe. It was very much a personal achievement

…

, whose only asset was ownership of a pair of sandals once owned – and rather scuffed up – by Jesus and given to the monks by Charlemagne’s father Pippin, kept its semi-independence and attracted an endless stream of pilgrims with surprising success for many centuries, only totally losing its status

…

number of acts of eradicatory chauvinism and counter-chauvinism. A further complication for France is that the Duchy of Flanders in the original division of Charlemagne’s Empire was made part of ‘West Francia’, i.e. France, but its counts were often able to maintain a sort of semi-independence.

…

crowning of the King of the French in Rheims (he only officially became Emperor when crowned by the Pope). As the equally legitimate successor to Charlemagne, the Emperor/King had his own historical explanation for Lotharingia, seeing it all as uncontestably part of the Holy Roman Empire. The Emperor had

…

of St Brice in the 1650s of the tomb of Childeric I. This accidental find catapulted everything back some two hundred and fifty years before Charlemagne, to the century after the Western Roman Empire had collapsed, a world which must have still been densely Roman in its appearance, probably with

…

towns and more limited trade. Childeric’s son, Clovis I, was baptized, united the Frankish tribes and founded the Merovingian dynasty which lasted until Charlemagne’s dad put the last of them into a monastery. The management of Childeric’s rediscovered tomb has not exactly been a curatorial model. It

…

to pray here (and was an important patron, giving thanks here after he defeated an Ummayad army at Narbonne in 737 on Servatius’s birthday); Charlemagne, Charles V, Philip II, most recently John Paul II. The church above it has been swept aside repeatedly by invaders and accidents, but somehow

…

nothing would have survived – we would be wholly ignorant of Tacitus and his friends. One curiosity was the role of Irish monks, particularly at Charlemagne’s court. When the Irish had been converted to Christianity they had no written language of their own, so took the shaping and purity of

…

ancient lichen and facial repairs. Eaten at by centuries of smoke and guano, nearly killed off by a huge fire in the eighteenth century, this Charlemagne is a figure who demands respect. It seems a shame not to have ritual bowls filled with floating flowers, guttering oil lamps, temple guards in

…

smart outfits, worshippers pressing their foreheads to the cold stone floor – plus a few bits of bunting and perhaps something dreadful involving animals. Charlemagne, who persuaded the Pope to crown him the new Roman Emperor in a great ceremony on Christmas Day in the propitious year of 800, had

…

, had made himself King of the Franks, the Frankish kingdom being an ancient, sprawling and complex entity, directly if stormily linked to Roman Gaul. Charlemagne’s birthright included most of modern France, all of the Netherlands and much of what is now western Germany. But by his anti-pagan campaigns

…

to make Europe Christian, and aligned with Rome rather than Constantinople. It is hair-raising how thin the thread is by which we know about Charlemagne’s actions – a handful of chronicles, letters and a couple of biographies (one by the enjoyably named Notker the Stammerer), which are fascinating, but

…

frustratingly without any means by which they can be double-checked. Einhard, who worked closely with Charlemagne for many years, wrote his life so that the events of the present would not be ‘condemned to silence and oblivion’ – and it is

…

blank reigns of these centuries appear desolate and poorly managed simply because historians have no vivid sources. Even with what we do have about Charlemagne it is often impossible to know if some tall tale, monk’s failure of memory or ancient lie has become for ever enshrined in

…

oddly intimate link between ourselves and the people who stood in the same place, it feels, really quite recently. Like most of his family, Charlemagne came from the modern German–Dutch–Belgian border area. He both inherited a huge swath of land and extended it through campaigning into the east

…

Avar Empire, which had controlled Central Europe for some two centuries, bringing back to Aachen ‘fifteen oxcarts’ of Avar treasure. However, to think of Charlemagne as the acknowledged ruler of everywhere between the Pyrenees and Denmark, the mountains of Bohemia and central Italy, would be a mistake. Many of these

…

imposing his will – sometimes only temporarily – from Spain to the Baltic. Just as his grandfather Charles Martel had ended serious Arab incursions into France, so Charlemagne carved out new Christian areas in Central Europe and fought back the ‘Northmen’. With these last, it gets a bit awkward as an accidental side

…

had time on their hands and could lean back on their rough-hewn stools, wondering whether their berserkers might enjoy going abroad for a bit. Charlemagne had not been buried long before his children and grandchildren learned a lot more about these seafaring tourists. CHAPTER TWO The split inheritance » Margraves,

…

As mentioned at the beginning of the comparatively cheap book you are currently reading, Lotharingia (initially known as Middle Francia) emerged from the manoeuvres of Charlemagne’s grandsons. We probably have more grounds for regretting the fall of the old empire than its inhabitants did. Historians love large political units because

…

Duke of Württemberg later on. Sticking to the post-Treaty of Ribemont world of 880, this was the last partition of what was still recognizably Charlemagne’s inheritance. It enshrined Lotharingia – Middle Francia – as a huge zone which both the French king and German king could equally lay dynastic claim

…

The treaty was signed by Louis III for West Francia and Louis III for East Francia, respectively great-great-grandson and great-grandson of Charlemagne, each named after Charlemagne’s first successor Louis I ‘the Pious’. Each twist and turn over the coming centuries, as the digits piled up after each further

…

choose to know nothing at all about, say, the Battles of Formigny and Castillon, which threw the English out of France. As discussed earlier, Charlemagne’s inheritors had in West Francia and East Francia created two opposing blocs and in Lotharingia an intermediate bloc linked to East Francia. But Lotharingia

…

, and where Otto is buried – a vast jump forward, some three hundred miles east from the old stamping ground at Aachen. In parallel with Charlemagne’s wars with the Saxons and Avars and Otto’s further march east in the following century, although with very tangled and widely variegated roots

…

and of a seemingly limitless supply of mean, disloyal vassals. By 882, in a thoughtful piece of symbolic redecoration, a Viking army had converted Charlemagne’s chapel at Aachen into stables. The Emperor and the Pope and their fates were so entangled that their tumbling prestige dragged everyone down into

…

Here was Philip associating himself with expiatory chivalry (despite backing out of his single combat with Duke Humphrey), and with the power and glamour of Charlemagne. It is hard not to wonder whether the Dukes (and indeed other rulers of the period) and their guests got a bit bored with being

…

compared to the same people over and over – there is always a tapestry of Godefroy of Bouillon or Charlemagne. But perhaps the static nature of the iconography was the point: that greatness and legitimacy created a permanent present, where both dynastic heroes and

…

like to think that Bosch and his anonymous sculptor vied with one other for rival compelling mutant effects in their different media. As with the Charlemagne sculpture in Zürich, there can be few more atmospheric objects than statues designed for high places but now brought down after centuries of erosion

…

Constantinople made noises suggesting that Rome was merely its Johnny-come-lately low-comedy offshoot. Much of the elaborate ceremony around the Pope crowning Charlemagne and his successors as Roman Emperor and the elaborate iconography around the Theban Legion martyrs and ancient sites associated with Constantine was to counter the

…

violent anti-Protestant edict, wrote to the Pope that ‘no Roman pontiff has received such a harvest of joys from Germany since the time of Charlemagne’ – in other words directly comparing Protestants to pagan Saxons and Avars. As Ferdinand’s advisers flapped their arms about with excitement, not knowing whether

…

Emperor of Austria as, confusingly, Francis I. Both Napoleon and Franz could draw on the Treaty of Verdun as the French and German inheritors of Charlemagne, although Napoleon had pole position in now owning Aachen and the Rhineland imperial sites. The Holy Roman Empire, with its ancient, confused roots, was

…

Wellington were in attendance, with other figures such as Goethe and some senior Rothschilds. There was a fun visit to see the sacred relics of Charlemagne, effectively, in the wake of Napoleon’s visit there, decontaminating the place with a strong spray of hysterical reactionary mysticism. There were discussions about

…

Nietzsche and Wagner were both knitting together different cultures in much the same way Philipp Franz von Siebold had linked things Dutch and Japanese. Charlemagne’s regular invasions of the Ruhr to kill Saxons had unfortunately deprived Germany of paganism and had indeed been so thorough that no trace of

…

and a horned helmet just to buy a stamp from it, and one of the world’s very few medieval-style water-towers. With its Charlemagne Hall, mythological, faux-runic carvings and hunkered down Romanesque clock-tower, the station is almost lovable, even if originally designed just as a backdrop

…

to compete with the real Monkey Island of the Schloß. Wilhelm would hang out here with his friends, surrounded by pictures of his great predecessors Charlemagne, Godefroy of Bouillon, King Arthur and King David, with stuffed capercaillies and hundreds of old weapons. Guests would come in through the carved gateway

…

and lies of the mongrel Allied coalition. CHAPTER FOURTEEN Dreams of Corfu » Walls and bridges » The Kingdom of Mattresses » The road to Strasbourg » Armageddon » Charlemagne comes home Dreams of Corfu A few miles outside Utrecht is a grand house which must have a fair claim to be one of the

…

themselves in places they no longer recognized, sometimes with wives who had long settled down with someone else. One final collaborationist flourish was the SS Charlemagne Division of French Fascist volunteers. The number of men actively fighting with the Germans was never huge – the ‘Rexist’ Belgian leader Léon Degrelle’s

…

Walloon Legion was only a few thousand men, mostly killed on the Eastern Front.5 The Charlemagne Division was almost self-consciously set up to perform a last stand in 1944, filled with brutalized scrapings from the collapsing Vichy regime, while the

…

senior political leaders escaped to the Swabian castle of Sigmaringen to await their fates. Members of the Charlemagne Division found a sort of martyrdom as the very last defenders of Hitler’s bunker. I mention it here because of its curious badge.

…

Avar gold than with this engineering marvel, but in other ways, of course, it is an inspired name. This refreshed and overhauled symbolism around Charlemagne came together in the early 1950s. It turned out that the future did not lie in France trying to pinch places like the Saarland, but

…

enmity by joining together. They would go on to make three core Lotharingian cities into their capitals: Brussels, Luxembourg and Strasbourg. In addition the Charlemagne Prize was set up by the City of Aachen to be awarded to whoever its judges viewed as contributing most to the promotion of unity

…

Prussia (London, 2006) Richard Cobb, French and Germans, Germans and French (Hanover, NH, 1983) Alexander Cockburn, Corruptions of Empire (New York, 1988) Roger Collins, Charlemagne (Basingstoke, 1998) Philippe de Commynes, Memoirs: The Reign of Louis XI, 1461–83, trans. Michael Jones (Harmondsworth, 1972) Philip Conisbee (ed.), Georges de la Tour

…

, Diary of His Journey to the Netherlands, introduced by J.-A. Goris and G. Marlier (London, 1971) Einhard and Notker the Stammerer, Two Lives of Charlemagne, trans. David Ganz (London, 2008) Carlos M. N. Eire, Reformations: The Early Modern World, 1450–1650 (New Haven, 2016) Amos Elon, The Pity of

…

1300–1914 (Cambridge, 2000) Stefan Fischer, Hieronymus Bosch (Köln, 2016) John B. Freed, Frederick Barbarossa: The Prince and the Myth (New Haven, 2016) Johannes Fried, Charlemagne (Cambridge, MA, 2016) Robert Gerwarth, The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End, 1917–1923 (London, 2016) Robert Gildea, Children of the Revolution

…

to search for terms of interest. For your reference, the terms that appear in the print index are listed below. Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle) and Charlemagne Charlemagne Prize Congress of (1818) coronations in and famine and Napoleon Treasury and the Vikings Aare, River Aargau abbeys Acre, fall of (1291) Adam Adelaide

…

on the Rhine fossils Fouquet, Jean France Arab incursions into and the Austrian Netherlands and the Black Death and Britain and Burgundy Capetian dynasty and Charlemagne Concordat of Worms (1122) and England and the First World War and Flanders and the ‘Fronde’ rebellion geography and Germany and the Holy Roman

…

King Neerwinden, Battle of (1793) Nether Rhine River Netherlands, Kingdom of the and Albrecht Dürer and Amsterdam and Baarle-Hertog and Belgium and Britain and Charlemagne and England and the First World War and flooding and France and Margaret of Austria and Neutral Moresnet northern partitioning (1640s) and religion St Elizabeth

…

Spanish Road Spanish Succession, War of the (1701–14) Spanish Truce see Twelve Years Truce spas Speyer Cathedral Spinola, Ambrogio Splinter Sands, Dunkirk SS Charlemagne Division Stanley, Henry Morton Statue of Liberty Stavelot Stavelot Abbey Stavelot-Malmédy Stellingabund Sterne, Laurence A Sentimental Journey Tristram Shandy Stevinus, Simon Stiftskirche, Baden-Baden

…

Red, yellow and blue » Shame on the Rhine Chapter Fourteen Dreams of Corfu » Walls and bridges » The Kingdom of Mattresses » The road to Strasbourg » Armageddon » Charlemagne comes home Postscript Notes Acknowledgements Bibliography Index Illustration Credits Also by Simon Winder A Note About the Author Copyright Farrar, Straus and Giroux 175 Varick

The Eternal City: A History of Rome

by Ferdinand Addis · 6 Nov 2018

dream that had been born in Rome a century earlier: the imperial dream of Charles the Great, king of the Franks, known to history as Charlemagne. Of all the Germanic states that had emerged from the ruin of the Roman empire in the west, it was the kingdom of the Franks

…

new religion, Islam. At the Battle of Tours, in AD 732, it was Franks who finally halted the Muslim advance into Europe – Franks led by Charlemagne’s grandfather, Charles ‘the Hammer’ Martel. Rome, up until those years, had remained under the precarious authority of the eastern emperors in Constantinople – ‘Roman emperors

…

king. His son, Charles, was determined to be even greater. And so indeed he proved. By the time of his death in AD 814, Charles – Charlemagne – had established the largest dominion western Europe had seen since the fall of the Roman empire, a territory that encompassed most of modern France, Germany

…

and Italy, stretching from the Elbe to the Pyrenees. With vast territory came vast ambition: Charlemagne had a vision, a dream of power that was not just the power of the mailed fist and the lance. He was not content merely

…

to be a warlord. Frankia, in Charlemagne’s dream, was a new Israel. Charlemagne himself was David or Josiah, a holy monarch, set on high by the Lord to lead his people to a new state

…

stations as the choirs of angels and saints in paradise took their places before God. A perfect kingdom should practise a perfect Christianity. ‘Exert yourselves,’ Charlemagne commanded his clerics in AD 789, ‘to bear the erring sheep back within the walls of the ecclesiastical fortress… lest the wolf who lies in

…

fragmentation. Christianity in Ireland, for example, isolated even before the empire fell, developed in a quite different way to Christianity in Frankia or Visigothic Spain.† Charlemagne, conqueror of many nations, found many incompatible Christianities practised by his subjects. To bring these into order – to build his perfect kingdom, in other words

…

from Germany to Spain, some religious authority had to be found that would transcend the merely national. There was only one answer. Charlemagne turned to Rome. In AD 774, Charlemagne’s armies wrapped up the conquest of the Lombard kingdom of Italy. It was surprisingly straightforward; no army could stand against the

…

into border regions or marches, each with its own margrave, appointed by the king. With the Lombards pacified, an intense two-way traffic began between Charlemagne’s court at Aachen and the city of Rome. Heading north were clerics and scholars, even choirmasters to teach the Franks the latest Roman modes

…

from the Lombards were now put firmly into papal possession. The pope could now count himself among the wealthiest magnates in Charlemagne’s kingdom. These gifts did not mean, however, that Charlemagne in any way acknowledged the pope as his superior, or even as an equal. Popes had been trying to establish

…

this world is ruled: ‘the sacred authority of the priests and the royal power. Of these that of the priests is the more weighty.’ But Charlemagne was no believer in the separation of church and state, and far less would he have accepted the idea that the pope might be in

…

still at best, as one historian has put it, no more than Charlemagne’s ‘senior vice president for prayer’. Supreme authority, both temporal and spiritual, would always rest with Charlemagne himself. This was not a novel conception. On the contrary, Charlemagne had only to look east across the Adriatic Sea to find a

…

model: the Byzantine emperor. And indeed, if you thought about it – as Charlemagne doubtless did – there was something absurd about the contrast between that emperor, with his tiny rump state on the Bosphorus, and the king of the

…

lands extended beyond the dreams of the ancient Caesars. This was easily put right. On Christmas Day, AD 800, in the Basilica of St Peter, Charlemagne announced to the world, as if there were any possibility of confusion, what sort of place he really regarded himself as having in God’s

…

holy scheme. There, before the assembled magnates of Frankia, Lombardy and Rome, the deacons and subdeacons, the bishops of suburbicarian sees arranged by rank, Charlemagne was crowned with gold and precious gems and the pope bowed down and prostrated himself before him, and all the grandees and the people together

…

pope in the Lateran ninety-seven years later. Nonetheless, the currents of history flowed towards that grim spring day like water to a plughole, as Charlemagne’s dream of empire rushed to its own undoing. The problem was that in those days of the Early Middle Ages, it was hard, if

…

the Carolingians had enjoyed smooth successions from a strong king to a dominant son who was able quickly and effectively to eliminate any rivals. After Charlemagne, the pattern held for one generation more. Louis the Pious was crowned by his father as co-emperor at Aachen in AD 813, and succeeded

…

Charlemagne as sole ruler of the Frankish empire the year after. By the 830s AD, however, the empire was being pulled apart by Louis’s sons.

…

When Louis died in AD 840, Charlemagne’s great empire was divided between them, in shares corresponding very roughly to Germany, Italy and France. The grandsons and great-grandsons of

…

Charlemagne were soon locked in an endless struggle for supremacy. To win the support of important magnates in their bids for power, they traded away the

…

popes in Rome were once again abandoned. Worse than abandoned. In a pool of post-imperial sharks, the papacy, fattened with estates and revenues by Charlemagne’s generosity, now found itself the plumpest fish. By the end of the ninth century, half the great magnates in Italy, descendants of

…

Charlemagne’s Frankish lords, were queuing up to bite off chunks of papal territory for themselves. Pope Formosus, before he became a horror story, had been

…

corpse was carried to its final resting place, the images of the saints on the walls are said to have bowed their heads in sorrow. Charlemagne’s empire was a shattered ruin. The papacy, which was meant to raise that empire up to God, had been debased by the ambitions of

…

, Marozia could have her son, Pope John XI, crown Hugh emperor. Hugh was, on his mother’s side, a very distant descendant of Charlemagne; perhaps Marozia hoped that Charlemagne’s imperial dream could be resurrected, with Marozia herself triumphant at the new emperor’s side. Things turned out quite otherwise: ‘At the

…

the little lights of people sheltering under the arches. All in all, the city could make a bleak impression. The English scholar Alcuin, visiting with Charlemagne, had been moved to verse: ‘Roma caput mundi, mundi decus, aurea Roma / nunc remanet tantum saeva ruina tibi’ – ‘Rome, the world’s capital, world’s

…

the north, after generations of political disorder, the lords of East Frankia and Germany had finally produced a leader fit to inherit the ambitions of Charlemagne. In AD 962 King Otto I ‘the Great’ of Germany arrived in Rome to be anointed emperor. At his side was his formidable wife Adelheid

…

, in his ecclesiastical guise as Pope John XII, had to bite down his pride and place the imperial crown on the German’s head. Like Charlemagne, Otto was building a holy empire, and he needed a co-operative bishop in Rome to help him do it. Octavian – a mere boy, and

…

and grandson, three ruling emperors. Their heartland was the duchy of Saxony, the flat land where the Weser and the Elbe meet the North Sea. Charlemagne long ago had brought Christianity to the Saxons with spear and sword, and over the centuries that followed the dukes of Saxony transmitted the Good

…

the other half-dozen great families of medieval Rome were never far behind. The empire, as Otto III inherited it, was a fragile creation. Under Charlemagne, the great territorial ranks – duke, count, margrave and so on – were positions handed out by the monarch himself to his loyal followers; by the time

…

at the Lateran was believed to be not the pagan Marcus Aurelius but the Christian Constantine. ¶ Octavian may also have been a distant descendant of Charlemagne through his mother Alda, daughter of Alberic’s old enemy, Hugh of Provence. # Otto III of Rome, Saxony and Italy, servant of the Apostles, by

…

by German manners, by the richness of the land, the splendour of the churches. They walked in the footsteps of Christian emperors, the successors to Charlemagne. In the forest south of Paderborn, they passed the place where Sigurd killed the dragon Fafnir with his magic sword, Gram. They remember the hardships

…

given it the backing it needed to flourish there. In doing so, they had thought to emulate the founder of the renewed empire, the great Charlemagne. They, as much as anyone, wanted a church that was powerful, dignified and respectable. Such a church would reflect its glory on to the emperors

…

position that it could start re-asserting control over the lands of the old papal principality – the central Italian territories granted to the pope by Charlemagne. City families, the Frangipani especially, started chipping away at the once impregnable holdings of the counts of Tusculum. Meanwhile, the pope led a Roman militia

…

Italian peninsula, an imperial scribe at the court at Ravenna copied the old scroll, adding his signature. Three hundred years after that, the Frankish emperor Charlemagne set his cathedral schools to work preserving ancient documents. At the monastery of St Germanus, in Burgundy, a Benedictine scholar, Heiric of Auxerre, added his

…

Celentano, Adriano 582 Cellini, Benvenuto 421–2, 423 Celsius 230 Celts see Gauls/Celts Cenci, Vicolo 533 Ceres, goddess 48 Ceri, Renzo da 419–20 Charlemagne 251, 254–9, 260, 266, 268, 271, 273, 304, 309 Charles (‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’) 460 Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor 338 Charles ‘the Hammer’ Martel

The Library: A Fragile History

by Arthur Der Weduwen and Andrew Pettegree · 14 Oct 2021 · 457pp · 173,326 words

at the same time provided a means to extend a family’s influence within the growing ecclesiastical power structure. It was under the patronage of Charlemagne (742–814) that the monasteries assumed greater political importance and took on a more active role as book producers. Over the course of his long

…

much of western and central Europe. This was a military as much as an administrative endeavour. The great ambition of Charlemagne, the first emperor in the West since the fall of Rome, was to reform the disparate territories and peoples under his Christian rule, uniting them

…

in administration, law and faith.15 This extraordinary undertaking required a ruler with the administrative talent and vision of Charlemagne, yet it could not have been achieved without the ecclesiastical network of monasteries. The Christian Church was the common denominator in

…

Charlemagne’s empire, and Latin was the only tongue that could unite it. One of Charlemagne’s primary concerns was the accuracy of language and its proper usage by his clergy, administrators and subjects

…

precise performance of ecclesiastical rituals that underpinned Christian worship. Efficient governance also relied on effective communication; in Charlemagne’s vast empire, communication became increasingly written, which prompted demand for a standardised language.16 In 784, Charlemagne wrote to all monasteries and bishops in his realm, stating that he ‘deemed it useful that

…

the monasteries but noted that letters which he received from them often revealed their poor command of Latin. In a decree issued five years later, Charlemagne specifically addressed the need for proper schools, where boys could learn to read, and the need for monasteries to prepare better books, ‘because often some

…

desire to pray to God properly, but they pray badly because of the incorrect books’.17 The proliferation of such ‘incorrect books’, in Charlemagne’s eyes, provided the impetus for an intense period of book production and circulation, unlike anything that Europe had seen since the days of the

…

were the school books of late Roman authors like Aelius Donatus and Martianus Capella, which dominated the curriculum of Carolingian education. It was appropriate that Charlemagne, who busied himself so greatly with the correctness of literature, should also come into the possession of a rich collection of books. Some of these

…

were made for him by monasteries or by talented scribes at court, and included sumptuous books: the Godescalc Evangelistary, a liturgical work made for Charlemagne’s court chapel, was written on purple-dyed parchment using gold and silver ink.19 Many other similarly magnificent books, which had their bindings decorated

…

the staples of the monasteries, and they would remain so after the Carolingian empire was divided, and ultimately crumbled. It was to his credit that Charlemagne did not concentrate book production around his own court but allowed it to remain common practice in the monasteries, ensuring that the habit of scholarship

…

and scribal activity would outlast the period of political instability that followed Charlemagne’s death. The organisation of monasteries and nunneries into separate orders, with houses spread out across the continent, provided a natural network for the circulation

…

, decorated with gold leaf and bound in bejewelled covers, had been a mainstay of the libraries of European monasteries and courts since the age of Charlemagne. Yet it was in the workshops of Paris, Bruges and Florence that the art of bookmaking reached its apogee, driven by specialisation, the division of

…

library in Paris. Neither would have an enduring future. A Contested Inheritance The origins of the town library can be traced to the era of Charlemagne.2 In 802, the Synod of Aachen had made parish churches responsible for keeping a minimal number of liturgical books. Books were required for worship

…

: Bloomsbury, 2018). 14. Yaniv Fox, Power and Religion in Merovingian Gaul: Columbanian Monasticism and the Frankish Elites (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014). 15. Rosamond McKitterick, Charlemagne: The Formation of a European Identity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), p. 306. 16. Rosamond McKitterick, The Carolingians and the Written Word (Cambridge: Cambridge University

…

. 316. 18. James Stuart Beddie, ‘The Ancient Classics in the Mediaeval Libraries’, Speculum, 5 (1930), pp. 3–20. 19. McKitterick, Charlemagne, pp. 331–2. 20. Donald Bullough, ‘Charlemagne’s court library revisited’, Early Mediaeval Europe, 12 (2003), pp. 339–63, here p. 341. 21. Laura Cleaver, ‘The circulation of history books in

…

Italian Renaissance Library’, Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, 26 (1966), pp. 61–80. Bischoff, Bernhard, Manuscripts and Libraries in the Age of Charlemagne (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994). Brett, Edward T., ‘The Dominican Library in the Thirteenth Century’, The Journal of Library History, 15 (1980), pp. 303–308

…

. Bullough, Donald, ‘Charlemagne’s court library revisited’, Early Medieval Europe, 12 (2003), pp. 339–63. Christ, Karl, The Handbook of Medieval Library History, ed. and trans. Theophil M

…

Moyen Age au milieu du XVIIe siècle (Paris: Promodis, 1982). McKitterick, Rosamond, The Carolingians and the Written Word (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989). McKitterick, Rosamond, Charlemagne: The Formation of a European Identity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008). Meeder, Sven, The Irish Scholarly Presence at St. Gall: Networks of Knowledge in the

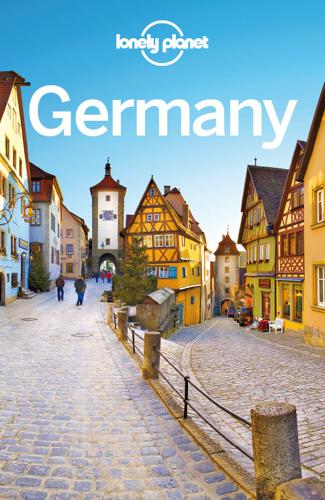

Germany Travel Guide

by Lonely Planet

Kölner Dom, Germany’s largest cathedral, dominate the city’s skyline (Click here) Aachen Some 30 German kings were crowned in the Aachen Dom; where Charlemagne lies buried in an elaborate gilded shrine (Click here) Lutherstadt-Wittenberg Protestant reformer Martin Luther is buried in the Schlosskirche, the church to whose door

…

pick!) and indulge in a hearty supper and local Kölsch beer in a Rhenish tavern. Head to Aachen next to walk in the footsteps of Charlemagne and munch on a crunchy Printen cookie, then travel back in time another few centuries in storied Trier. More than 2000 years old, it’s

…

famous for its starring role in history. To appreciate its impact, visit Xanten and Cologne, both hubs of the Roman Empire; Aachen, the capital of Charlemagne’s Frankish Reich; and Münster and Osnabrück where treaties ending the epic Thirty Years’ War were signed. RHENISH STYLE Breaking for a glass of Kölsch

…

. The church owns two relics of enormous importance: branches that are thought to come from Christ’s crown of thorns, and a victory cross of Charlemagne, whose army overran much of Western Europe in the 9th century. In the Holy Chapel, the votive candles, some of them over 1m tall, are

…

in the area had a go at ruling Worms, including the Huns, the Alemans and finally the Franks, and it was under the Frankish leader, Charlemagne, that the city flourished in the 9th century. The most impressive reminder of the city’s medieval heyday is its majestic, late-Romanesque Dom. A

…

, which has retained its air of Cold War mystery. Away from the river, Aachen still echoes with the beat of the Holy Roman Empire and Charlemagne. Much of Germany’s 20th-century economic power stemmed from the Northern Rhineland industrial region known as the Ruhrgebiet. Now cities such as Essen are

…

. Resources »Ruhr Tourismus (www.ruhr-tourismus.de) »Industrial Heritage Trail (www.route-industriekultur.de) »100 Schlösser Route (www.100-schloesser-route.de) »Route Charlemagne Information Centre (www. route-charlemagne.eu) »Hotel Drei Könige (Click here) Cologne & Northern Rhineland Highlights Feel your spirits soar as you climb the the majestic loftiness of Cologne

…

the industrial age at the Zollverein coal mine (Click here) in Essen Step back to the Middle Ages in Aachen (Click here), with memories of Charlemagne around every corner Enjoy the vibrant life of Münster (Click here), where great history combines with youthful pleasures Taste the unique beers of the region

…

the map for millennia. The Romans nursed their war wounds and stiff joints in the steaming waters of Aachen’s mineral springs, but it was Charlemagne who put the city firmly on the European map. The emperor too enjoyed a dip now and then, but it was more for strategic reasons

…

still very much an international city, and has a unique appeal thanks to its location in the border triangle with the Netherlands and Belgium. And Charlemagne’s legacy lives on in the stunning Dom, which in 1978 became Germany’s first Unesco World Heritage Site. REDECORATING THE DOM Like the stereotypical

…

of the Dom in Aachen have been on a centuries-long remodelling binge. The result is that very little of what you see dates to Charlemagne’s time. For instance, the interior of the main part of the church was redone for the the umpteenth time in the 19th century. At

…

Sophia in Istanbul. The inside of the dome overhead dates from the 17th century and on it goes. Other than possibly the hidden relics and Charlemagne’s bones, the oldest authenticated item in the Dom is the 12th-century chandelier that was a gift from Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa. Sights Appreciating the

…

.de; 10am-7pm Apr-Dec, to 6pm Jan-Mar) It’s impossible to overestimate the significance of Aachen’s magnificent cathedral. The burial place of Charlemagne, it’s where more than 30 German kings were crowned and where pilgrims have flocked since the 12th century. Aachen Sights 1 Couven Museum B3

…

B3 15Leo van den DaeleB2 16 Noblis B3 Drinking 17 Magellan A2 Entertainment 18 Apollo Kino & Bar A1 The oldest and most impressive section is Charlemagne’s palace chapel, the Pfalzkapelle, an outstanding example of Carolingian architecture. Completed in 800, the year of the emperor’s coronation, it’s an octagonal

…

encircled by a 16-sided ambulatory supported by antique Italian pillars. The colossal brass chandelier was a gift from Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa during whose reign Charlemagne was canonised in 1165. Pilgrims have poured into town ever since that time, drawn in as much by the cult surrounding

…

Charlemagne as by his prized relics : Christ’s loincloth when he was crucified, Mary’s cloak, the clothes used for John the Baptist when he was

…

Christ’s Passion, and the jewel-encrusted gilded copper pulpit, both fashioned in the 11th century. At the far end is the gilded shrine of Charlemagne that has held the emperor’s remains since 1215. In front, the equally fanciful shrine of St Mary shelters the cathedral’s four prized relics

…

tour (adult/child €5/4; 11am-4.30pm Mon-Fri, 1-4pm Sat & Sun, tours in English 2pm), you’ll barely catch a glimpse of Charlemagne’s white marble imperial throne in the upstairs gallery. Reached via six steps – just like King Solomon’s throne – it served as the coronation throne

…

veritable mother lode of gold, silver and jewels. Focus your attention on the Lotharkreuz, a 10th-century processional cross, and the marble sarcophagus that held Charlemagne’s bones until his canonisation; the relief shows the rape of Persephone. Rathaus HISTORIC BUILDING Offline map Google map (Markt; adult/concession €5/3; 10am

…

50 life-size statues of German rulers, including the 30 kings crowned in town. It was built in the 14th century atop the foundations of Charlemagne’s palace, of which only the eastern tower, the Granusturm, survives. Inside, the undisputed highlights are the Kaisersaal with its epic 19th-century frescos by

…

. To the west is a mishmash of old buildings that have parts dating back to when this was part of Charlemagne’s palace. This is the future site of the Route Charlemagne information centre. Couven Museum MUSEUM Offline map Google map (www.couven-museum.de; Hühnermarkt 17; adult/child €5/3; 10am

…

Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst trains the spotlight on contemporary art (Warhol, Immendorf, Holzer, Penck, Haring etc) and also stages progressive changing exhibits. ROUTE CHARLEMAGNE The Route Charlemagne is designed to showcase Aachen’s 1200-year tradition as a European city of culture and science. The city’s sites are linked together

…

the old building on the west side of the Katschhof. It is hoped it will open by 2014. In the meantime, the Route Charlemagne Information Centre (www.route-charlemagne.eu; Haus Löwenstein, Markt; 10am-6pm) is in one of Aachen’s few surviving medieval townhouses. Activities In fine weather, get off the

…

, the carriage containing his coffin rolled all the way to Dortmund, stopping on the spot of the church. There’s a statue of him, opposite Charlemagne, at the entrance to the choir. Of outstanding artistic merit is the late-Gothic high altar. There are good views from the bell tower. Marienkirche

…

of Soest, Paderborn is the largest city in eastern Westphalia. It derives its name from the Pader which, at 4km, is Germany’s shortest river. Charlemagne used Paderborn as a power base to defeat the Saxons and convert them to Christianity, giving him the momentum needed to rise to greater things

…

. A visit by Pope Leo III in 799 led to the establishment of the Western Roman Empire, a precursor to the Holy Roman Empire, and Charlemagne’s coronation as its emperor in Rome the following year. Paderborn remains a pious place to this day – churches abound, and religious sculpture and motifs

…

and flat wooden ceiling. Carolingian Kaiserpfalz HISTORIC SITE East along Am Abdinghof to the north of the Dom are the remnants of the Carolingian Kaiserpfalz, Charlemagne’s palace where that historic meeting with Pope Leo took place. It was destroyed by fire and replaced in the 11th century by the Ottonian

…

; www.kaiserpfalz-paderborn.de; Am Ikenberg 2; adult/child €3.50/1.50; 10am-6pm Tue-Sun), which presents excavated items from the days of Charlemagne, including drinking vessels and fresco remnants. The only original palace building is the twee Bartholomäuskapelle next door. Consecrated in 1017, it’s considered the oldest

…

a round trip. WITCHES & WARLOCKS The Bodetal was first inhabited by Celts, whose fortresses were conquered by Germanic tribes and used for pagan rituals before Charlemagne embarked upon campaigns to subjugate and Christianise the local population during the 8th-century Saxon Wars. Today Harz mythology blends these pagan and Christian elements

…

secret gatherings to carry out their rituals. They are said to have darkened their faces one night and, armed with broomsticks and pitchforks, scared off Charlemagne’s guards, who mistook them for witches and devils. In fact the name ‘Walpurgisnacht’ itself probably derives from St Walpurga, but the festival tradition may

…

developed near today’s centre from about 100 AD, and one settlement in particular that in 787 was given its own bishop’s seat by Charlemagne. In its earliest days, it was known as the ‘Rome of the North’ and developed as a base for Christianising Scandinavia. Despite this, it gradually

…

pedestrianised, the square’s centrepiece is its fountain. Completed in 1878, it shows important figures in Hamburg’s past including Emperor Constantine the Great and Charlemagne and is surmounted by a figure showing the might of the Hanseatic League. Segelschule Pieper BOAT HIRE Offline map Google map (247 578; www.segelschule

…

developed their own identity and, for the first time, it became possible to talk about ‘German’ rulers, the most illustrious of which was, without doubt, Charlemagne. But the fortunes of Germany long remained in the hands of feudal rulers, who pursued their own petty interests at the expense of a unified

…

introduced hierarchical Church structures. Kloster Lorsch (Lorsch Abbey) in present-day Hesse is a fine relic of this era. From his grandiose residence in Aachen, Charlemagne (r 768–814), the Reich’s most important king, conquered Lombardy, won territory in Bavaria, waged a 30-year war against the Saxons in the

…

800. The cards were reshuffled in the 9th century, when attacks by Danes, Saracens and nomad tribes from the east threw the eastern portion of Charlemagne’s empire into turmoil and four dominant duchies emerged – Bavaria, Franconia, Swabia and Saxony. The graves of Heinrich and other Salian monarchs can today be

…

found in the spectacular cathedral in Speyer. Charlemagne’s burial in Aachen Dom (Aachen Cathedral) turned a court chapel into a major pilgrimage site (and it remains so today). The Treaty of Verdun

…

(843) saw a gradual carve-up of the Reich and, when Louis the Child (r 900–11) – a grandson of Charlemagne’s brother – died heirless, the East Frankish (ie German) dukes elected a king from their own ranks. Thus, the first German monarch was created. WHAT

…

very good one. It grew out of the Frankish Reich, which was seen as the successor to the defunct Roman Empire. When Charlemagne’s father, Pippin, helped a beleaguered pope (Charlemagne would later do the same), he received the title Patricius Romanorum (Protector of Rome), virtually making him Caesar’s successor. Having

…

retaken the papal territories from the Lombards, he presented them to the Church (the last of these territories is the modern Vatican state). Charlemagne’s reconstituted ‘Roman Empire’ then passed into German hands. The empire was known by various names throughout its lifetime. It formally began (for historians, at

…

, which hosted the coronation and burial of dozens of German kings from 936. Otto I was first up in the cathedral. In 962 he renewed Charlemagne’s pledge to protect the papacy, and the pope reciprocated with a pledge of loyalty to the Kaiser. This made the Kaiser and pope strange

…

a treaty signed in the Rhineland-Palatinate town of Worms in 1122. Two Lives of Charlemagne (2008; Penguin Classics) is a striking biography of Charlemagne, beautifully composed by a monk and a courtier who spent 23 years in Charlemagne’s court. Under Friedrich I Barbarossa (r 1152–90), Aachen assumed the role of

…

Reich capital and was granted its rights of liberty in 1165, the year Charlemagne was canonised. Meanwhile, Heinrich der Löwe (Henry the Lion), a member of the House of Welf with an eye for Saxony and Bavaria, extended influence

…

of Tours and stops the progress of Muslims into Western Europe from the Iberian Peninsula, preserving Christianity in the Frankish Reich. 773–800 The Carolingian Charlemagne, grandson of Charles Martel, answers a call for help from the pope. In return he is crowned Kaiser by the pope. 919–1125 Saxon and

…

Roman Empire in 962 when Otto I is crowned Holy Roman Emperor by the pope, reaffirming the precedent established by Charlemagne. 1165 Friedrich I Barbarossa is crowned in Aachen. He canonises Charlemagne and later drowns while bathing in a river in present-day Turkey while co-leading the Third Crusade. 1241 Hamburg

…

former GDR brand that’s been a big hit in the new Germany. Top of section Literature, Theatre & Film Literature Early Writing Oral literature during Charlemagne’s reign (c 800) and secular epics performed by 12th-century knights are the earliest surviving literary forms, but the man who shook up the

…

southern Bavaria to the coal mines of Essen. Romanesque & Gothic Among the grand buildings of the Carolingian period, Aachen’s Byzantine-inspired cathedral – built for Charlemagne from 786 to about 800 – and Fulda’s Michaelskirche are surviving masterpieces. A century on, Carolingian, Christian (Roman) and Byzantine influences flowed together in a

…

’s finest collection of Roman heritage. »Aachen Cathedral (Click here) – Begun in the 8th century, this blockbuster building is the final resting place of Emperor Charlemagne. »Speyer’s Kaiserdom cathedral (Click here) – This magnificent 11th-century cathedral holds the tombs of eight German rulers. »Regensburg (Click here) – An Altstadt crammed with

The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean

by David Abulafia · 4 May 2011 · 1,002pp · 276,865 words

to place the process of disintegration, and several suspects: the Germanic barbarians in the fifth century and after, the Arab conquerors in the seventh century, Charlemagne and his Frankish armies in the eighth century, not to mention internal strife as Roman generals competed for power, either seeking regional dominions or the

…

Islamic conquests of the seventh century (culminating in the invasion of Spain in 711), or even until the Frankish empire of the incestuous mass-murderer Charlemagne acquired control of Italy and Catalonia.1 There have also been attempts to show that recovery began much earlier than past generations of historians had

…

. Knowing that Constantinople was incapable of offering any help, the islanders turned instead to the ruler of Gaul and northern Italy, Charlemagne, whom they acknowledged as their new overlord. Charlemagne sent some forces and the Arabs were repelled the next time they raided the islands.19 He ordered his son Louis to

…

at Sousse was enough to force the Franks out of Africa. In any case, the Frankish empire had passed its peak with the death of Charlemagne in 814, and his successor Louis the Pious was distracted from the western Mediterranean by internal rivalries. In the 840s, the Arabs were free to

…

751) the former Byzantine province, or Exarchate, whose capital lay at Ravenna. Frankish armies were still active close to the Adriatic in the 790s, when Charlemagne crushed the great, wealthy empire of the Avars, annexing to his empire vast tracts of what are now Slovenia, Hungary and the northern Balkans. In

…

rule.26 These campaigns brought Frankish and Byzantine interests into collision. Ill-feeling between the Franks and the Byzantines was compounded by the coronation of Charlemagne as western Roman emperor on Christmas Day 800 in Rome, even if the new emperor laughed off this event as of minor importance. Byzantium remained

…

deeply sensitive about its claim to be the true successor to the Roman Empire until its fall in 1453. Reports that Charlemagne thought he might like to take over Sicily added to the unease. He even seemed to be conspiring with the Abbasid caliph of Baghdad, Harun

…

arrival of the Franks in Italy in the late eighth century, the inhabitants of the lagoons were tempted to defect to the new Roman emperor Charlemagne. His armies were close by and he could lure them with promises of trading privileges in Lombardy and beyond. Moreover, the Franks had made themselves

…

they besieged Comacchio, still loyal to the Franks. This had the unfortunate effect of drawing a Frankish army and navy towards the region, led by Charlemagne’s son Pippin, king of Italy. Pippin scared the Byzantine fleet away, which left the lagoons dangerously exposed, and he laid siege to the lido

…

be believed.32 Both the Franks and the Byzantines regarded this war as a distraction from more important issues, and had an appetite for peace. Charlemagne realized that if he made concessions he could secure grudging recognition as emperor from the Byzantines. In 812 a formula emerged that respected Byzantine claims

…

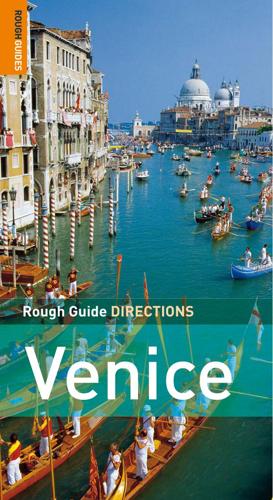

East and West. This was a unique position, of which merchants took full advantage. Out of the lagoons, and out of the Adriatic war with Charlemagne, emerged the city of Venice, as a physical, political and mercantile entity. The conflict with the Franks encouraged the scattered people of the lagoon to

…

from the eighth and ninth centuries have been found in western Europe, they arrived in greater quantities at the end of the eighth century, when Charlemagne was carving out his new Frankish dominion that stretched into northern Spain and southern Italy, and Byzantine coins began to appear in quantity only from

…

their own gold coins, the first to be produced in western Europe (apart from Sicily, southern Italy and parts of Spain) since the days of Charlemagne.32 By 1300, the presence of the florin of Florence in every corner of the Mediterranean demonstrated the primacy of the Italians and the increasing

…

Merrills (ed.), Vandals, Romans and Berbers, pp. 4–5. 18. Merrills, ‘Vandals, Romans and Berbers’, pp. 10–11. 19. R. Hodges and D. Whitehouse, Mohammed, Charlemagne and the Origins of Europe (London, 1983), pp. 27–8; also Wickham, Inheritance of Rome, p. 78: ‘the Carthage-Rome tax spine ended’. 20. J

…

. (Washington, DC, 2002), vol. 1, p. 193. 30. C. Vita-Finzi, The Mediterranean Valleys: Geological Change in Historical Times (Cambridge, 1969); Hodges and Whitehouse, Mohammed, Charlemagne, pp. 57–9. 31. C. Delano Smith, Western Mediterranean Europe: a Historical Geography of Italy, Spain and Southern France since the Neolithic (London, 1979), pp

…

’, pp. 173–4; G. D. R. Sanders, ‘Corinth’, in Laiou (ed.), Economic History of Byzantium, vol. 2, pp. 647–8. 36. Hodges and Whitehouse, Mohammed, Charlemagne, p. 28. 37. Morrisson and Sodini, ‘Sixth-century economy’, pp. 174, 190–91; C. Foss, Ephesus after Antiquity: a Late Antique, Byzantine and Turkish City

…

(Cambridge, 1979); M. Kazanaki-Lappa, ‘Medieval Athens’, in Laiou (ed.), Economic History of Byzantium, vol. 2, pp. 639–41; Hodges and Whitehouse, Mohammed, Charlemagne, p. 60. 38. W. Ashburner, The Rhodian Sea-law (Oxford, 1909). 39. C. Foss and J. Ayer Scott, ‘Sardis’, in Laiou (ed.), Economic History of

…

, p. 615; K. Rheidt, ‘The urban economy of Pergamon’, in Laiou (ed.), Economic History of Byzantium, vol. 2, p. 624. 40. Hodges and Whitehouse, Mohammed, Charlemagne, p. 38; J. W. Hayes, Late Roman Pottery (Supplementary Monograph of the British School at Rome, London, 1972) and Supplement to Late Roman Pottery (London

…

, 400–800 (Oxford, 2005), pp. 720–28. 41. Arthur, Naples, p. 141; Morrisson and Sodini, ‘Sixth-century economy’, p. 191. 42. Hodges and Whitehouse, Mohammed, Charlemagne, p. 72. 43. Morrisson and Sodini, ‘Sixth-century economy’, p. 211. 44. F. van Doorninck, Jr, ‘Byzantine shipwrecks’, in Laiou (ed.), Economic History of Byzantium

…

. 518, p. 217. PART THREE THE THIRD MEDITERRANEAN, 600–1350 1. Mediterranean Troughs, 600–900 1. H. Pirenne, Mohammed and Charlemagne (London, 1939) – cf. R. Hodges and D. Whitehouse, Mohammed, Charlemagne and the Origins of Europe (London, 1983); R. Latouche, The Birth of the Western Economy: Economic Aspects of the Dark Ages

…

Economy (Cambridge, 2007), p. 63. 4. T. Khalidi, The Muslim Jesus: Sayings and Stories in Islamic Literature (Cambridge, MA, 2001). 5. Hodges and Whitehouse, Mohammed, Charlemagne, pp. 68–9; D. Pringle, The Defence of Byzantine Africa from Justinian to the Arab Conquest (British Archaeological Reports, International series, vol. 99, Oxford, 1981

…

et sociale (Paris, 1997), pp. 95–107. 7. S. Sand, The Invention of the Jewish People (London, 2009), pp. 202–7. 8. Pirenne, Mohammed and Charlemagne; A. Lewis, Naval Power and Trade in the Mediterranean A.D. 500–1100 (Princeton, NJ, 1951); McCormick, Origins, p. 118; P. Horden and N. Purcell

Vanished Kingdoms: The Rise and Fall of States and Nations

by Norman Davies · 30 Sep 2009 · 1,309pp · 300,991 words

the fourteenth century 19 The States of Burgundy, fourteenth–fifteenth centuries 20 The Imperial Circles of the Holy Roman Empire 21 Pyrenees 22 Marches of Charlemagne’s Empire, ninth century 23 The cradle of the Kingdom of Aragon, 1035–1137 24 The Iberian peninsula in 1137 25 The heartlands of the

…

at Jovis Villa (Jupille) on the River Meuse, and were descended from the famous warrior Charles Martel. Their mightiest son was Charles the Great, or Charlemagne (r. 768–814), whose dominions stretched from the Spanish March to Saxony and who raised himself to the dignity of emperor. Those same centuries saw

…

days of Clovis and Gundobad, the old Frankish and Scando-Burgundian tongues had still been spoken alongside the late Latin of the Gallo-Romans. By Charlemagne’s time, all these vernaculars had been replaced by a range of new idioms in the general category of Francien or ‘Old French’. Frankish only

…

hopes that the Regnum Burgundiae might rise again at any point soon. In the century following Charles Martel, the Frankish Empire flourished, faltered and fell. Charlemagne spent much of his time either in the north, in Aachen, or fighting on the peripheries of his lands against Moors, Slavs and Avars, and

…

St Peter’s in Rome on his knees as a penitent. Later, he created the first Papal State.52 In the tradition of his ancestors, Charlemagne planned to divide his empire between his sons. In the event, since only one son survived him, the empire stayed intact until it was divided

…

the Carolingian legacy needs to keep the number ‘three’ to the fore; threefold partitions were performed three times over. Most students grasp that each of Charlemagne’s grandsons received a one-third share, and it is not hard to remember that Lothar’s ‘Middle Kingdom’ consisted of three sections. It is

…

north-west, the Kingdom of Lower Burgundy in the south, and the Kingdom of Upper Burgundy in the north-east. The initial carving up of Charlemagne’s empire in 843, therefore, was but one step in a much longer process. Although Lothar took the greater part of the sometime Burgundian kingdom

…

of the papacy, exercised a magic attraction. Papal approval carried enormous weight, and every would-be German emperor dreamed of walking in the steps of Charlemagne. So the Kingdom of Burgundy was routinely neglected. One German emperor even left Germany as well as Burgundy to fend for itself. Frederick II (r

…

larger kingdom, he was giving expression to the political claim that he and his subjects were the only true heirs to the Frankish tradition of Charlemagne and Clovis. His success may be gauged from the fact that the German name of Frankreich, ‘Land of the Franks’, became attached to the western

…

part of Charlemagne’s former empire, but not to the eastern part, which was now being subsumed into the concept of Deutschland. The shift in nomenclature was no

…

of these was Inigo Aristra, the Basque warlord who drove out the Carolingians from the western Pyrenees in the early ninth century, not long after Charlemagne’s campaign against the Moors. A second, in the eleventh century, was Sancho El Mayor, originally ‘King of Pamplona’. The narrative grows infernally complicated following

…

Catalan, but their national anthem is bilingual. Few countries can boast a national song more redolent of history: El Gran Carlemany, mon Pare, Le grand Charlemagne, mon père, dels arabs em deslliura, des arabes me délivra, i del cel vida em dona et du ciel me donna la vie Meritxell, la

…

nacions neutral neutre entre deux nations. sols resto l’única filla Seule, je reste l’unique fille de l’imperi Carlemany. de l’empire de Charlemagne, creient i lliure croyante et libre onze segles depuis onze siècles, creient i lliure vull ser pour toujours je veux l’être siguin els furs

…

mos tutors que les Fueros soient mes tuteurs i mos prínceps defensors. et les princes mes protecteurs!11 (‘My father, the great Charlemagne, / saved me from the Arabs, / and Meritxell, my great mother, / gave me life from Heaven. / I was born a princess, an heiress / neutral between two

…

nations. / I remain alone, the one and only daughter / of Charlemagne’s empire. /Faithful and free /for eleven centuries, / I wish to be so for ever, / may the customary laws be my tutors / and the princes

…

my protectors.’) The Andorrans still sing of Charlemagne for their country started life under his rule and was never incorporated by the great powers which succeeded him. Nowhere can one understand the lie

…

earlier. That gaggle of Christian lordships, large and small, had been created when Frankish power spilled over the Pyrenees to confront Islam as it advanced. Charlemagne’s campaign of 778 against the Moors was recorded in the opening lines of the Old French epic poem, the Chanson de Roland: Carles li

…

held by a King, Marsilie, whom God did not love. He served Mahomet, and worshipped Apollo: Poets record only the ills which he performed.12 Charlemagne’s retreat from Zaragoza culminated in the heroic fight at the Pass of Roncevalles, where Roland and Oliver were immortalized

…

. Charlemagne’s response to the threat from Muslim Iberia was to organize four militarized buffer zones: the March of Gascony, the March of Toulouse (to which

…

more akin to Occitan, the language of Languedoc. Barcelona, founded by Hannibal’s brother in the third century BC and liberated from the Moors by Charlemagne, was far more venerable than Zaragoza. The House of Berenguer, which was the successor to a line of twenty-four counts in Barcelona since the

…

that of Ramiro. And its territorial possessions were markedly more extensive. Ever since the time of the first Count Bera (r. 801–20), son of Charlemagne’s retainer William of Toulouse, those holdings had waxed and waned over the generations. But, anchored on the easternmost counties of the former Marca Hispanica

…

the open plains to the south, and the westward passage of Germanic, and later of Slavic tribes, did not penetrate their homeland. The empire of Charlemagne and his successors never reached them; nor did the religion of the Nazarenes, which gradually overtook the north European mainland in the tenth century and

…

’s fortunes into Piedmont. Amadeus III (r. 1103–48) died in Rhodes during the Second Crusade. Pierre II (r. 1263–8), known as ‘the little Charlemagne’, was a warrior who greatly expanded his territories. Amadeus VI (r. 1343–83), the Green Count, died of the plague at the end of a

…

centre and, with 46,000 inhabitants, is slightly larger than Coburg; its name, meaning ‘Waters of the Goths’, appears as Gotaha in a document of Charlemagne’s era. Its principal modern attraction is the Friedenstein, a former ducal palace and ‘pearl of the early Baroque’.2 Eisenach, overlooked by the Wartburg

…

: un roi pour un peuple (Paris, 1952). 51. Antonio Santosuosso, Barbarians, Marauders and Infidels: The Ways of Medieval Warfare (Boulder, Colo., 2004). 52. Alessandro Barbero, Charlemagne: Father of a Continent (Berkeley, 2004), pp. 28–33. 53. Jean Richard, Les Ducs de Bourgogne et la formation du duché (Paris, 1954). 54. Lucy

…

). II 12. The Song of Roland, trans. Glyn Burgess (London, 1990), lines 1–9. 13. Barton Sholod, ‘The Formation of a Spanish March’, in his Charlemagne in Spain: The Cultural Legacy of Roncesvalles (Geneva, 1966), pp. 44 ff. 14. Ralph Giesey, If Not, Not: The Oath of the Aragonese and the

…

Chalon 106 Chamberlain, Neville 633 Chambéry 402, 416, 417–18, 423, 426–7, 428, 434, 436 Charbonnieres, Château de 435 Charlemagne (Charles the Great) 100, 104, 161–2 Marches of Charlemagne’s Empire 162, 163 Charles I of Austria 450, 475, 476, 599 Charles II of England, Scotland and Ireland 679 Charles

…

, duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha 563–7, 568–70, 571 Charles Félix/Charles le Heureux/Carlo il Felice 415, 435 Charles the Great see Charlemagne Charles-Louis/Carlo-Luigi, boy-king of Etruria 518, 534 Charles Martel 100, 104 Charles de Navarre 128 Charles le Téméraire (Karel de Stoute) 132

…

-Hungary Huns 17, 21, 31, 93, 94 Hurrem/Roxalana 442–3 Hutsulchyzna 455 Hyde, Douglas 648 Iberia 17, 115, 163, 522–3 Aragon see Aragon Charlemagne and Muslim Iberia 162 Iberian Jews 190 Iberian Peninsular in 1137 172 and the Reconquista 115, 164, 166–9, 173, 181, 183, 184 Roman Church

…

, 195–6 Manau (Clackmannan) 49 Manfred, son of Frederick II 192, 195 Mantaille, Synod of 110, 112 Manzoni, Alessandro 413 Marca Hispanica 162 Marches of Charlemagne’s Empire 162, 163 Marchidun (Roxburgh) 48, 54 Marcilla, Diego 190–91 Marcinkiewicz, Jan 237 Marengo 508 Margaret, St 77 Margaret, countess-palantine of Burgundy

…

, 404, 406, 409, 410, 412, 414, 415, 416, 516 Napoleon and the Piedmontese 501 Turin see Turin (Torino) Pieracki, Bronisław 477 Pierre II, ‘the little Charlemagne’ 404–6 pilgrimage 55, 184, 435, 453, 464, 473 Pillars of Hercules (Gibraltar) 20 Pillau 358, 385 Piłsudski, Józef 297, 301, 473–4, 476 Pinerolo

…

Empire/Byzantines Holy see Holy Roman Empire Roman Aquitania 17, 18–20, 24 Roman Gaul 17 Roman, Pan 446 Romanovs 368–9, 570, 587 Rome Charlemagne in 104 fall, under Risorgimento 429 Festa della Repubblica 397–400 French driven out by Neapolitan troops 529 French occupation (1798) 506, 507 modern 398

The Basque History of the World

by Mark Kurlansky · 4 Jul 2010

de Roland (The Song of Roland), became a classic of French literature. Revered for the extraordinary beauty of its Old French verse, it tells of Charlemagne’s great victories in Iberia against the Muslims and how he had now decided to return to France. He marched his army through the Roncesvalles

…

pass. Just as the last of his men were climbing out of the pine forest to the narrow rocky port, leaving Charlemagne’s nephew, Roland, to hold the pass, the Muslims attacked. Roland fought valiantly with his great sword, but the Franks had been betrayed to the

…

earlier, in 778. From the opening lines—”King Charles, the Great, our Emperor, has stayed in Spain for seven years”—the poem is historically wrong. Charlemagne had only spent a few months in Spain, and the ones betrayed were not the French but the Muslims. There was no Ganelon, but there

…

control of the Ebro Valley. In 777, Suleiman, wishing to take the Ebro away from the emir’s control, had crossed the Pyrenees to offer Charlemagne a list of cities above the great river that he had arranged to have fall to the Franks without a fight. Seeing an opportunity

…

, Charlemagne crossed into Spain in spring 778 from the Mediterranean side, the old Visigoth path of conquest. He was able to take Girona, Barcelona, and Huesca

…

Ebro, the Muslim commander did not follow the plan, instead defending the city. Faced with a real fight for the first time in this expedition, Charlemagne decided to forgo Zaragoza and return to France. It was now August, and he had been in Spain only about four months. On his way

…

to attack Pamplona, destroy its walls, and loot the town. In so doing he enraged not the Muslims but the Basques. To return to France, Charlemagne chose the same pass as had Abd-al-Rahman in his ill-fated 732 conquest of Europe. Throughout history this was the pass chosen for

…

army had to thin out to single file to drop down along a mountain trail to the rocky valley of waterfalls that parts the Pyrenees. Charlemagne made it through and up to the steep mountainside village of Valcarlos, where wild apples still grow in the steep woods. While waiting in Valcarlos

…

years later, the Basques killed every trapped Frank. Possibly some escaped, but it is certain that they killed Roland or Hruodlandus, two others close to Charlemagne, and a significant part of the force. Then the Basque forces simply dispersed, going home to their mountain villages, so that there was no Basque

…

army for Charlemagne to pursue in vengeance. Pamplona was left to revert to Muslim rule. At the end of the poem, tears are rolling over the white beard

…

of Charlemagne as he says, “Oh God, how hard my life is.” But, in fact, Charlemagne never recorded the encounter. The Basque attack of August 15, 778, was to be the only defeat

…

Charlemagne’s army ever suffered in his long military career. The first record of the battle was written in 829, after the

…

death of Charlemagne, and states that the French army, although far larger, was defeated by Basques. The Basques built few monuments to their victories. In Pasajes San Juan,

…

that follows the deep water harbor cutting into the mountains, stands a nearly forgotten stone shrine, built in 1580, that commemorates the Basque victory over Charlemagne. The lesson of the battle of Roncesvalles should have been: Do not to alienate the Basques. Yet somehow, in the ensuing centuries, Roland became the

…

, was about to fight to the death when a cannonball struck him in the legs. The castle fell, and the French had Navarra. Then, repeating Charlemagne’s mistake, they needlessly antagonized the Basques on their way into Castile by pillaging the Navarrese town of Los Arcos for several days. The Castilians

…

Santiago, or his body, going off to Galicia, because they wanted to rally Christendom to defend northern Spain. One legend from the time claimed that Charlemagne himself, the great anti-Moorish warrior who died in 814, had found the body of Santiago in Galicia. Just as it had become a fashion

…

with gauzelike fog draped over the peaks. But there is a path through the wall from the little village of Arnéguy, up to Valcarlos where Charlemagne had waited for Roland, down again past little waterfalls and streams and up again to the heights of Ibañeta and then down once more to

…

have been able to see that they would be next. BY THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY, witchcraft should have seemed a ridiculously old-fashioned accusation. In 787, Charlemagne had outlawed the execution of witches and made it a capital crime to burn a witch. A tenth-century Church law, Canon Episcopi, demanded that

The Death of Money: The Coming Collapse of the International Monetary System

by James Rickards · 7 Apr 2014 · 466pp · 127,728 words

contrast to a mere city, kingdom, or country in the area called Europe. That unity arose in Charlemagne’s Frankish Empire, the Frankenreich, near the turn of the ninth century. The similarities of Charlemagne’s empire to twenty-first-century Europe are striking and instructive to those, especially in the United States

…

apparent on trading floors in London, New York, and Tokyo. Europe and its currency, the euro, despite their flaws and crises, are set to endure. Charlemagne, a late eighth- and early ninth-century Christian successor to the Roman emperors, was the first emperor in the West following the fall of the

…

a true European empire but a Mediterranean one, although it extended from the Roman heartland to provinces in present-day Spain, France, and even England. Charlemagne was the first emperor to include parts of present-day Germany, the Netherlands, and the Czech Republic with the former Roman provinces and Italy, to

…

form a unified entity along geographic lines that resemble modern western Europe. Charlemagne is called, by popes and laymen alike, pater Europae, the Father of Europe. Charlemagne was more than a king and conqueror, although he was both. He prized literacy and scholarship as well

…

the finest minds of the early Middle Ages such as Saint Alcuin of York, considered “the most learned man anywhere” by Charlemagne’s contemporary and biographer, Einhard. The achievements of Charlemagne and his court in education, art, and architecture gave rise to what historians call the Carolingian Renaissance, a burst of light

…

to end an extended dark age. Importantly, Charlemagne understood the significance of uniformity throughout his empire for ease of administration, communication, and commerce. He sponsored a Carolingian minuscule script that supplanted numerous forms

…

in different parts of Europe, and he instituted administrative and military reforms designed to bind the diverse cultures he had conquered into a cohesive realm. Charlemagne did not pursue his penchant for uniformity past the point necessary for stability. He advocated diversity if it aided his larger goals pertaining to education

…

is necessary to achieve efficiencies for the greater good; otherwise local custom and practice should prevail. Charlemagne’s monetary reforms should seem quite familiar to the European Central Bank. The European monetary standard prior to Charlemagne was a gold sou, derived from solidus, a Byzantine Roman coin introduced by Emperor Constantine I

…

in Italy to the Byzantine Empire, cut off trade routes between East and West. This resulted in a gold shortage and tight monetary conditions in Charlemagne’s western empire. He engaged in an early form of quantitative easing by switching to a silver standard, since silver was far more plentiful than

…

one-twentieth of a sou. With the increased money supply and standardized coinage, along with other reforms, trade and commerce thrived in the Frankish Empire. Charlemagne’s empire lasted only seventy-four years beyond his death in A.D. 814. The empire was initially divided into three parts, each granted to

…

one of Charlemagne’s sons, but a combination of early deaths, illegitimate heirs, fraternal wars, and failed diplomacy led to the empire’s long decline and final dissolution

…

, the First Reich, lasted over eight centuries, until it was dissolved by Napoleon in 1806. By reviving Roman political unity and advancing arts and sciences, Charlemagne and his realm were the most important bridge between ancient Rome and modern Europe. Notwithstanding the institutions of the Holy Roman Empire, the millennium after

…

Charlemagne can be seen largely as a chronicle of looting, war, and conquest set against a background of intermittent ethnic and religious slaughter. The centuries from

…

continually from 1667 to 1714, in which the Sun King pursued an explicit policy of conquest aimed at reuniting France with territory once ruled by Charlemagne. The European major litany of carnage continued with the Seven Years’ War (1754–63), the Napoleonic Wars (1803–15), the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71

…

by the fact that pro-euro forces have ultimately prevailed in every democratic election or referendum, and pro-euro opinion dominates poll and survey results. Charlemagne’s enlightened policies of uniformity, in combination with the continuity of local custom, exist today in the EU’s subsidiarity principle. The contemporary EU motto

…

, “United in diversity,” could as well have been Charlemagne’s. ■ From Bretton Woods to Beijing The euro project is a part of the more broadly based international monetary system, which itself is subject to

…

’s new Reich, intermediated through the EU, the euro, and the ECB, will be the greatest expression of German social, political, and economic influence since Charlemagne’s reign. Even though it will come at the expense of the dollar, the changes will be positive in most ways, because of Germany’s

…

.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=40446.0. Chapter 5: The New German Reich “the most learned man anywhere”: Einhard, The Life of Charlemagne (ninth century; reprint Kessinger, 2010). “The final step was cannibalism . . .”: Lauro Martines, Furies: War in Europe, 1450–1700 (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), p. 118. “No

…

the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces. New York: Public Affairs, 2013. Barabasi, Albert-Laszlo. Linked. New York: Plume, 2003. Barbero, Alessandro. Charlemagne: Father of a Continent. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. Beinhocker, Eric D. Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics. Cambridge

…

Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011. Einhard. The Life of Charlemagne. Ninth century; reprint Kessinger Publishing, 2010. Eisen, Sara, ed. Currencies After the Crash: The Uncertain Future of the Global Paper-Based Currency System. New York

…

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) MARKINT and, 37–39 Project Prophesy and, 28–34 Rauf plot and, 36–37 “Challenge of Information Warfare, The” (Pufeng), 44 Charlemagne, 112, 113–14, 118 chartalism (state theory of money), 168–69 chartal money, 168 Chávez, Hugo, 40, 231 cheap-dollar policy of Federal Reserve. See

…

crisis of 2010 and, 128–30 U.S. money market fund investment in, 127 Eurobonds, 136–37 Europe, 112–18. See also European Union (EU) Charlemagne’s Frankenreich, 112, 113–14 post–World War II steps to unification, 116–18 warfare and conquest in, history of, 115–16 European Atomic Energy

…

of, 196, 253, 296 gold, 215–42 BIS transactions, 276–78 central bank acquisition of, since 2010, 225–30 central bank manipulation of, 271–81 Charlemagne’s switch from gold to silver standard, 114 Chávez’s repatriation of, 40, 231 China’s accumulation of, 12, 61, 226–30, 282–84, 296

This Sceptred Isle

by Christopher Lee · 19 Jan 2012 · 796pp · 242,660 words

done the new king of the Mercians was Offa (750?–96), one of the most famous names of this period and a contemporary of Charlemagne (741–814). Charlemagne was the most celebrated of the Frankish rulers. The Franks were the post-Roman barbarians of what we now know as Belgium, France, Germany

…

, the Netherlands and Switzerland. It was Charlemagne who inspired the rethinking of kingship, whereby in return for allegiance the leader protects those who follow him or her. His extension of this thought

…

Church that would continue long after his empire’s passing. Although barbaric and indeed largely illiterate, Charlemagne inspired learning and such a close relationship with Rome that, on Christmas Day 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne emperor of what would become the Holy Roman Empire. Given that Leo III had called for

…

Charlemagne’s help the previous year when he was in danger of being usurped, the coronation was the

…

least gift of the Holy Father. Given the power and the uncompromising ambition of Charlemagne, the relationship with the king of the English (not

…

of England) tells us much about the importance of Offa. Charlemagne had wanted one of his sons to marry one of the daughters of Offa. Offa’s reaction was that the process of diplomatic relations had

…

to be two-way. If he was to take Charlemagne’s son as an in-law, then one his Offa’s sons should marry one of Charlemagne’s daughters. If this seems petty diplomacy, it was not. The marriage of sons and daughters among

…

the King of the English – not of England as a land or State, but of the people. Also, Offa negotiated treaties on equal terms with Charlemagne who would become emperor. Therefore Offa’s reputation must go far beyond the creation of a dyke. By AD 796 Offa was dead and the

…

. It had few friends in Continental Europe, whereas Louis of France was confident enough to believe that he was successor to the power of the Charlemagne empire. He fell to war with the Popes and flayed the Huguenots, the French Calvinists, of whom so many fled to England and Ireland that

…

ref 1, ref 2 Chadwick, Edwin ref 1 Chamberlain, Joseph ref 1, ref 2, ref 3 Chamberlain, Neville ref 1 Champlain, Samuel de ref 1 Charlemagne ref 1, ref 2 Charles Albert of Bavaria ref 1 Charles I ref 1, ref 2, ref 3, ref 4 execution of ref 1, ref

A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived

by Adam Rutherford · 7 Sep 2016

last time invaders conquered Britain in 1066 with an arrow in the king’s eye; before the first Holy Roman Emperor, the great European conciliator Charlemagne; before Vikings and northern Scots set foot on the volcanic wilderness of Iceland, the very first to do so; before the Council of Nicaea and

…

working, and deserves recognition as such – a self-correcting way of acquiring knowledge and understanding. 3 When we were kings i: The king lives on Charlemagne, Carolingian King of the Franks, Holy Roman Emperor, the great European conciliator; your ancestor. I am making an assumption that you are broadly of European

…

not definitive. If you’re not, be patient, and we’ll come to your own very regal ancestry soon enough. Along with Alexander and Alfred, Charlemagne is one of a handful of kings who gets awarded the post-nominal accolade ‘the Great’. His early life remains mysterious and the stories are

…

as Aachen, now in contemporary Germany, or Liège in Belgium. Even Einhard, his dedicated servant and biographer, wouldn’t get drawn into the specifics of Charlemagne’s early life in his fawning magnum opus, The Life of Charles the Great. The very fact that this account exists – probably the first biography

…

– is testament to how important he was (or at least was seen to be). In many European languages, the word ‘king’ is itself derived from Charlemagne’s name. He was the son of Pippin the Short,1 an aggressive ruler of France who expanded the Frankish kingdom until his death during

…