Charles Lindbergh

description: American aviator, author, inventor, explorer, and social activist

225 results

1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History--and How It Shattered a Nation

by Andrew Ross Sorkin · 14 Oct 2025 · 664pp · 166,312 words

artists or athletes—but men of wealth. Hollywood stars like Charlie Chaplin, Clara Bow, and Douglas Fairbanks still drew headlines, as did Babe Ruth and Charles Lindbergh. But for the first time, businessmen joined their ranks. In an era that equated fortunes with brilliance, the titans of Wall Street and industry became

…

. The son of a minister, Lamont had more money than he could have ever imagined and was on a first-name basis with everyone from Charles Lindbergh to Benito Mussolini. His reputation was immaculate. “A tangible person” is how Time described him. “Tell him a joke and he will laugh. Offer him

…

to spread goodwill, Lamont then went around to “friends of the firm”—including former President Coolidge, Secretary of the Navy Charles Adams, the pioneering aviator Charles Lindbergh, General John J. Pershing, as well as Mitchell, Bernard Baruch, and John Raskob—and offered them the same discount. These telegrams, such as the one

The Arsenal of Democracy: FDR, Detroit, and an Epic Quest to Arm an America at War

by A. J. Baime · 2 Jun 2014 · 502pp · 125,785 words

all his riches couldn’t cure. With the help of “Cast Iron” Charlie Sorensen, Detroit’s heralded Hercules of the assembly lines, and the aviator Charles Lindbergh, the Fords attempted to turn the US Air Corps’ biggest, fastest, most destructive heavy bomber into the most mass-produced American aircraft of all time

…

the skies. There in the blue ether, at roughly 2:00 PM, he appeared—a speck in the distance, accompanied by an engine’s song. Charles Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis came into focus, circling above the concrete runway. Amid roars and whistles from the crowd, Lindbergh came in for a

…

sent Henry a personal note thanking him for his “humanitarian ideals” and for his work toward “the cause of peace.” (Soon after, the famed aviator Charles Lindbergh received a similar award, as did General Motors’ head of European operations, James Mooney, who met personally with Adolf Hitler about business conditions in Germany

…

be one of the great figures of all history. But if we lost, he would be damned forever. The cards are now stacked against us. —CHARLES LINDBERGH, January 7, 1941 ON THE EVENING OF May 9, 1940, Franklin Roosevelt sat in his second-floor study in the White House in his high

…

are not obsolete.” Clark wanted to know how the rest of that money “was squandered.” The man emerging as Roosevelt’s loudest critic, the aviator Charles Lindbergh, called the 50,000-airplane plan “hysterical chatter.” In Germany, Hermann Goering burst out laughing when he heard Roosevelt’s plan. “What is America,” commented

…

late to turn back now. Harry Bennett arrived at his office one morning during the early days of the Nazi pounding of London to find Charles Lindbergh waiting for him. In the basement of the Rouge, the aviator—who was now thirty-eight years old—stood as tall and slim as ever

…

Run? Spring to Fall 1942 I have seen the science I worshiped, and the aircraft I loved, destroying the civilization I expected them to serve. —CHARLES LINDBERGH AT 12:30 PM ON March 24, 1942, a train screeched into Michigan Central Station in Detroit, bound from Boston. From a Pullman car

…

, Charles Lindbergh stepped onto the siding with a suitcase in his hand. The platform appeared crowded. All over the country, urban train stations were symbolic microcosms of

…

among men, to feel the soil under my feet and to be smaller than the mountains and trees. —CHARLES LINDBERGH CIRCLING THE SKIES OVER Willow Run in the flight deck of a B-24, Charles Lindbergh worked through a series of maneuvers with a copilot beside him. He had probably piloted a wider array

…

over Willow Run, deep into the stratosphere, the airfield’s mile-long runways appeared no larger than pencils that one could snap in the fingers. Charles Lindbergh sat strapped in the single-seat cockpit of a Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bomber—nicknamed “Jug” for juggernaut. Motoring through the ether at speed

…

a strange, rather good-looking girl,” said Sorensen. “Hard to believe that she could be a killer.”) By the end of winter, even the hypercritical Charles Lindbergh had to admit that the factory was humming. “We have been ahead of schedule for several months now,” he wrote in his journal on March

…

, separated from a toilet by a partition. The war in Dearborn was on. Early in 1944, Henry Ford’s two most famous employees left him. Charles Lindbergh got a call from Washington. He was given paperwork that allowed him to fly to the Far East, where he could put his aviation skills

…

quarter of what it was in one blow.” Said another: “The end of the world certainly can’t be worse.” Days after the Nazis surrendered, Charles Lindbergh ventured into Germany as a guest of some military officers. Lindbergh stood in awe of what he saw. “When you looked at the cities, you

…

Jon Meacham’s Franklin and Winston: An Intimate Portrait of an Epic Friendship are both must-reads. From an aviation perspective, The Wartime Diaries of Charles Lindbergh, Stephen E. Ambrose’s The Wild Blue: The Men and Boys Who Flew the B-24s over Germany, 1944–1945, and Michael Sherry’s The

…

shocking”: Morgenthau, memo to FDR, May 25, 1943, “Ford Motor Company, Foreign Funds Control,” box 636, FDR Library, Hyde Park, NY. [>] “Here was the power”: Charles Lindbergh, Of Flight and Life (New York: Scribner’s, 1948), p. 9. [>] “city forging thunderbolts”: “A City That Forges Thunderbolts,” New York Times, January 10, 1943

…

seventy-fifth birthday: “Ford Is Given Nazi Medal on 75th Birthday,” Washington Post, July 31, 1938. [>] “humanitarian ideals”: Max Wallace, The American Axis: Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh, and the Rise of the Third Reich (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2003), p. 146. [>] “I question the Americanism”: “Nazi Honor to Ford Stirs

…

what will happen”: Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich (New York: Avon, 1970), p. 303. 8. Fifty Thousand Airplanes: Spring 1940 [>] “If Roosevelt took this”: Charles Lindbergh, The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970), p. 437. [>] “I have seen war on land”: Jon Meacham, Franklin and

…

to Charles Sorensen, June 4, 1941, acc 435, box 51, “Ford–Willow Run Bomber Plant,” Benson Ford Research Center, Dearborn, MI. [>] “I have great admiration”: Charles Lindbergh, The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970), p. 363. [>] “I wish I trusted him”: A. Scott Berg, Lindbergh (New

…

. 790–91. [>] “This man’s navy is”: Peter Collier and David Horowitz, The Fords: An American Epic (San Francisco: Encounter, 2002), p. 149. [>] government signs: Charles Lindbergh, The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970), p. 685. [>] “the most enormous room”: Doris Kearns Goodwin, No Ordinary Time

…

Doherty Associates, 1987), p. 263. 17. Will It Run?: Spring to Fall 1942 [>] “I have seen the science”: Charles Lindbergh, Of Flight and Life (New York: Scribner’s, 1948), p. 51. [>] “I want to contribute”: Charles Lindbergh, The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970), pp. 566–67. [>] “He

…

acres of machinery”: Ibid., p. 613. [>] “The Ford schedule calls”: Ibid., p. 609. [>] “The rest of the industry”: Ibid., p. 610. [>] “There is no question”: Charles Lindbergh, “The Future of the Large Bomber,” unpublished memo, April 10, 1942, Lindbergh Papers, Manuscripts and Archives Division, Yale University Library, New Haven, CT. [>] “the man

…

”: Ibid., p. 662. [>] “Sorensen has the reputation”: Ibid., pp. 638–39. [>] Edsel had cancer of the stomach: Ibid., p. 697. [>] “I came here in hope”: Charles Lindbergh, “confidential” letter to Charles Sorensen, June 3, 1942, acc 65, box 69, “Charles Sorensen,” Benson Ford Research Center, Dearborn, MI. [>] “We couldn’t retaliate”: “Burma

…

yet in production”: Davis, FDR: The War President, p. 613. 20. A Dying Man: Fall 1942 to Winter 1943 [>] “This hour I rode the sky”: Charles Lindbergh, The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970), p. 222. [>] “a 1930s Mack truck”: Stephen E. Ambrose, The Wild Blue

…

Meyer, “Changes in Design Caused Initial Production Delay,” Washington Post, March 5, 1943, p. 1. [>] “the automobile was still”: Ibid. [>] Forty-one thousand feet up: Charles Lindbergh, Of Flight and Life (New York: Scribner’s, 1948), pp. 3–8. [>] Returning from the border: Ibid., p. 8. [>] “Now, it seemed a terrible”: Ibid

…

built by: “Altitude Chamber,” acc 435, box 2, “Ford and the War Effort,” vol. 8, Benson Ford Research Center, Dearborn, MI. [>] “Forty-three thousand feet”: Charles Lindbergh, The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970), p. 765. [>] “anxious to find out”: Ibid. 23. “The Arsenal of Democracy

…

, Hyde Park, NY. [>] “When can you start?”: Dwight D. Eisenhower, Crusade in Europe (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1952), p. 197. [>] “It’s the best handling”: Charles Lindbergh, The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970), p. 744. [>] “What alarmed us most”: Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich

…

. 13. [>] “She was a strange”: Charles Sorensen, personal account, p. 881, acc 65, box 69, Benson Ford Research Center, Dearborn, MI. [>] “We have been ahead”: Charles Lindbergh, The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970), p. 772. [>] “Bring the Germans”: David Lanier Lewis, The Public Image of

…

Germany, 1940–1945 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006), p. 287. [>] “The end of the world”: Ibid., p. 136. [>] “When you looked at the cities”: Charles Lindbergh, The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970), p. 943. [>] “Here was a place”: Ibid., p. 995. [>] “In the attack

The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance

by Ron Chernow · 1 Jan 1990 · 1,335pp · 336,772 words

, resided at the Harvard Business School Library. During my first day of research there, I pored over correspondence between Lamont and Franklin Roosevelt, Benito Mussolini, Charles Lindbergh, and Nancy Astor. These papers threw open a window on the hermetically sealed world of Morgan partners. Aside from the grace and clarity of these

…

he asked, “What do Morgan and Schwab [head of Bethlehem Steel] care for world peace, when there are big profits in world war?”21Minnesota congressman Charles Lindbergh, who had prompted the Pujo hearings, now condemned the “money interests” for trying to lure the country into war on the side of the Allies

…

money on behalf of the government to speed up airplane development. Through his stint on the Aviation Board, Dwight Morrow became friends with the young Charles Lindbergh. In fact, Morrow’s files show that the Morgan partners ended up paying for Lindbergh’s historic flight to Paris aboard The Spirit of St

…

$1 million. These documents were later exposed as forgeries, but in the meantime they damaged relations with Mexico. BEFORE leaving for Mexico, Morrow had invited Charles Lindbergh to his East Sixty-sixth Street apartment. Acting on a suggestion from Walter Lippmann, Morrow proposed that the young aviator pilot The Spirit of St

…

. Morrow hadn’t especially liked the young men his daughters dated—Anne and Elisabeth having gone out with Corliss Lamont, among others. He approved of Charles Lindbergh as a “nice clean boy” who didn’t drink, smoke, or see girls.25 But when Anne announced that she and Charles wanted to get

…

selfish little arriviste who drank himself to death.”43 In one respect, fate proved merciful to Dwight Morrow. Five months after Morrow died, his grandson, Charles Lindbergh, Jr., was kidnapped from his family’s home near Hopewell, New Jersey. The House of Morgan tried to help solve the famous case. Jack Morgan

…

F. Baker of First National, Richard Whitney of the New York Stock Exchange, and Bernard Baruch; a war hero—General John Pershing; a national hero—Charles Lindbergh; distinguished lawyers—John W. Davis and Albert G. Milbank; and distinguished families—Guggenheims, Drexels, Biddies, and Berwinds. The House of Morgan was shaken by the

…

Anthony Eden, secretary of state for foreign affairs, thought the best way to keep Germany from war was to strengthen Hitler’s economy. In 1936, Charles Lindbergh, at the invitation of Hermann Göring, toured Germany and marveled at its aircraft factories and technology, later urging Britain and France to retreat in self

…

and Washington—was tense and querulous. The House of Morgan’s pro-British views brought it into conflict with the nation’s most visible isolationist, Charles Lindbergh. In late 1935, the Lindberghs had moved to England, hoping to find a tranquillity denied them in America after their son’s kidnapping. At the

…

is torn in spirit and it is telling on her health.”49 Taking the tone of a concerned uncle, Lamont wrote to the rather aloof Charles Lindbergh. He said he had hesitated to contact him and cited his affection for the Morrow family. Then he asked point-blank who those nameless conspirators

…

missile fell in Old Broad Street, where George Peabody and Junius Morgan had once worked. After each such pounding of London, Harold Nicolson would send Charles Lindbergh a needling postcard, saying, “Do you still think we are soft?”16 As British children were evacuated from London, the House of Morgan proudly did

…

by two Yale graduate students, R. Douglas Stuart, Jr., and Kingman Brewster, it was a response to the William Allen White committee and promptly recruited Charles Lindbergh. Through his America First speeches, Lindbergh destroyed the last remnants of the hero worship he once aroused. Stumping the country, he would claim that “the

…

, Tom Lamont, George W. Perkins, Harry Davison, Russell Leffingwell, George Whitney, Vivian H. Smith, Teddy Grenfell, Thomas S Gates, Jr., Montagu Norman, Nancy Astor, and Charles Lindbergh for permitting me to quote from their unpublished papers. I owe a special debt to Edward Pulling, Paul and Cecily Pennoyer, and Laura Phillips, who

How to Make a Spaceship: A Band of Renegades, an Epic Race, and the Birth of Private Spaceflight

by Julian Guthrie · 19 Sep 2016

. Goddard was ridiculed when he stated his belief that a big enough rocket could one day reach the Moon, but he drew support from aviator Charles Lindbergh. Peter appreciated how Goddard’s rocket experiments as an undergraduate at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute yielded explosions and smoke that sent professors running for fire

…

the Voyager would land for no other reason than pilot exhaustion. This was a test of flying skill, physical endurance, and breakthrough design. Just as Charles Lindbergh had done with the Spirit of St. Louis in 1927, Burt had pared down the Voyager to its lightest possible weight. The in-flight tools

…

. Climbing Rainier wouldn’t be a history-making event like his grandfather’s plane flight, the 1927 journey across the Atlantic to Paris that made Charles Lindbergh a hero and at the time arguably the most famous man on Earth. But—for now—scaling Rainier would be Erik’s Paris, his milestone

…

he was reading his grandfather’s Pulitzer Prize–winning book, The Spirit of St. Louis. Erik knew his grandfather not as the world-famous aviator Charles Lindbergh, but simply as “Grandfather.” He was the tall and balding man who offered Erik fifty cents if he could learn to wiggle his ears (as

…

. He and his five siblings often slept outside on the upstairs porch, watching for shooting stars. Erik’s grandfather had the same love of nature. Charles Lindbergh, by all accounts a restless spirit, traveled extensively after World War II and became as fixated on the environment as he had been on his

…

out of town when they began reading concocted stories of their wedding and the gifts they had received. Syndicated gossip columnist Walter Winchell wrote about Charles Lindbergh’s gift to his son and new daughter-in-law, saying he had given them a new sports car, when in fact they drove an

…

on the floor. He picked it up and dusted it off. It was like an old friend to Gregg: The Spirit of St. Louis by Charles Lindbergh. Gregg was fourteen when he read Lindbergh’s story of his dangerous, history-changing flight from New York to Paris. Gregg opened the book to

…

The Spirit of St. Louis that Gregg Maryniak had given him the year before. The book was filled with revelations. Peter had always assumed that Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic in 1927 as a stunt, or maybe a dare. He’d had no idea that Lindbergh had made the first-ever flight

…

was almost twice the distance that had been previously covered by an airplane on a single flight. The successful flight not only made airmail pilot Charles Lindbergh famous, but it also created a global perception that flight was safe and available to the common man. Lindbergh was, after all, an Everyman-turned

…

have been instigated and acted upon by the individual or the small group—never have the masses brought about innovation. We have the accomplishments of Charles Lindbergh and the Rutan/Yeager Voyager team as our guiding stars, and every NASA program since Apollo as our incentive to bring about change. Peter envisioned

…

they needed to get Burt Rutan involved. Byron Lichtenberg said it would be crucial to find a group of backers as strong as the ones Charles Lindbergh had. Lindbergh had written: “My greatest asset lies in the character of my partners in St. Louis.” Back in his room, Peter grabbed his leather

…

, Columbia, and directly above was the international orange Bell X-1, the first plane to exceed the speed of sound. Suspended next to it was Charles Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis, the single-engine, single-seat monoplane with its skin of treated cotton fabric and dappled aluminum nose cone. Lindbergh was

…

give Goddard $100,000 so he could continue his work. When Apollo 8 became the first manned space mission to orbit the Moon in 1968, Charles Lindbergh sent the astronauts a message saying, “You have turned into reality the dream of Robert Goddard.” Until recently, Erik had been a dreamer and risk

…

. You say to yourself, nothing can go wrong . . . all my trespasses are forgiven. Best you not believe it.” It was similar to the warning that Charles Lindbergh gave his children: “It’s the unforeseen. It’s always the unforeseen.” Erik earned money doing woodworking when he could, but it was hard on

…

the front row—supporting him while not yet fully grasping the importance of a prize for suborbital flight—began, “The Spirit of St. Louis carried Charles Lindbergh from New York to Paris and into the hearts and minds of the world. Today, all eyes are on St. Louis again.” To rousing applause

…

Le Bourget, France, and were never seen again. While Orteig expressed sadness at these losses, he never wavered from his offering. On May 20, 1927, Charles Lindbergh departed from Roosevelt Field, flying nonstop, thirty-three hours and thirty minutes in a single-engine, single-pilot aircraft to Le Bourget Field outside of

…

on the Moon, and Burt Rutan at his drafting table creating what would be the Voyager. Peter spoke on video, saying, “Sixty-nine years ago, Charles Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis changed the way people think about air travel. The XPRIZE is trying to change the way people think about

…

goals. “We had no money and no teams when we kicked off the XPRIZE,” Peter said. “Our goal is to incentivize a twenty-first-century Charles Lindbergh.” He went on for several minutes. Al Kerth, who was present at the meeting, discussed the impact that the prize would have on St. Louis

…

Burt Rutan to get a sense of his thinking on pressurized balloon capsules. Peter, who had brought mockups of Virgin XPRIZE logos, told Branson about Charles Lindbergh and the history of the Orteig Prize. Branson was intrigued, and said he loved the idea. He had been drawn to space as a teenager

…

jump-start an industry and rekindle public interest in space. Elon and Adeo appeared keenly interested as Peter talked about the Spirit of St. Louis, Charles Lindbergh, and the teams that had signed up. “I’d love to meet some of the teams,” Elon said. Adeo offered to join the XPRIZE board

…

, it prevented the foundation from securing a sustainable endowment. Family members referred to Lloyd somewhat lovingly as “Dr. No.” Although, when Erik brought fake “official Charles Lindbergh merchandise” to his attention, nothing was done. Reeve advised Erik that if he was to do the flight, he should emphasize his name, and reference

…

Diego to St. Louis and days later flew to New York, where the most famous and difficult part of the flight was set to begin. Charles Lindbergh’s plane, the Spirit of St. Louis, was built for $10,580 by the scrappy Ryan Airlines company in San Diego. Its engine was a

…

and listened to their chatter. Soon they were asking Erik about his plane and flight. They were enthralled to hear he was the grandson of Charles Lindbergh. At one point, Erik asked, “Hey, can you check to see if you have a guy named Peter Diamandis on board?” He was flying from

…

after the announcement of the prize under the arch in St. Louis, Peter had his promise of $10 million. He wondered whether this was how Charles Lindbergh felt after securing his financial backing in St. Louis. Lindbergh had the money, but he still needed to build the right plane, get to the

…

, Colorado, and eight years after the private race to space was announced to great fanfare in St. Louis. That memorable night, in the city that Charles Lindbergh put on the aviation map, legendary airplane designer Burt Rutan had stood at the dais and revealed his dream of making a homebuilt spacecraft. Burt

…

’s weight allocation was 200 pounds, and he was slightly over. He reluctantly opted to bring the lighter polyester flag and, taking a cue from Charles Lindbergh, tore unnecessary pages out of a hefty flight checklist. He was in trouble if he didn’t know the flight checklist by now. He wore

…

efforts to get back into the cockpit, embraced him. Brian saw Erik Lindbergh and Peter Diamandis, who told him that he was “the day’s Charles Lindbergh,” the one who was going to make history. Heading his way next was his mother-in-law, Maria Anderson, looking well rested and holding a

…

. The two vehicles came to life seventy-seven years apart, but shared contrarian ideas, confident creators, and a race for a prize. And just as Charles Lindbergh had asked, “Why shouldn’t I fly to Paris?” Burt Rutan had said, “Why shouldn’t I fly to space?” As the museum was preparing

…

XPRIZE is announced in St. Louis in 1996. St. Louis was chosen as the city for the announcement because that was where the young aviator Charles Lindbergh found his backers to make his transatlantic flight. Peter Diamandis Burt Rutan at around age six at home in Dinuba, California, with a model plane

…

by how his fate was inextricably tied to the XPRIZE. I even went to St. Louis to visit the Racquet Club where Erik’s grandfather Charles Lindbergh met with his supporters and where, decades later, the XPRIZE found its backers. And, of course, there is Peter Diamandis, a true force of nature

…

rubber band between the two points. The rubber band will naturally find the configuration with the least tension, and this will be the shortest path. *Charles Lindbergh had designed the plane without dihedral, which is less stable. He did this because if he started to fall asleep, the plane would bank and

Americana: A 400-Year History of American Capitalism

by Bhu Srinivasan · 25 Sep 2017 · 801pp · 209,348 words

for the rise of commercial aviation, with thousands of small aircraft operating scheduled service. And Americans continued to push the boundaries of their own breakthroughs: Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic and became an international hero. American ingenuity was even putting radio into cars. Despite the loss of alcohol taxes due to Prohibition

…

, old guns, old planes, and a small standing army. In the late thirties, to one American living in England, the fate of Europe seemed sealed. Charles Lindbergh had done more than any living person to shorten the time and space separating Europe from North America. His 1927 crossing of the Atlantic Ocean

Hard Landing

by Thomas Petzinger and Thomas Petzinger Jr. · 1 Jan 1995 · 726pp · 210,048 words

the descriptive words of men—where immortality is touched through danger, where life meets death on an equal plane; where man is more than man. —CHARLES LINDBERGH, The Spirit of St. Louis, 1953 This is a nasty, rotten business. —ROBERT CRANDALL, American Airlines, 1994 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I grew up around the airlines. As

…

Air Lines. It was also thanks to Trippe’s action that a company called Robertson Aviation received the St. Louis-Chicago airmail route, on which Charles Lindbergh served as chief pilot. For Trippe himself, the airmail plan was fraught with unhappy irony. Though his company, Colonial Aviation, won the prized route between

…

longer had the equipment or training to carry out the job. Within weeks 12 army fliers perished, five in the first week alone. The demure Charles Lindbergh took time from his trailblazing on behalf of Pan Am to harangue Roosevelt publicly, setting the nation’s two most beloved public figures against one

…

and salesmanship. With backing from Wall Street, American had gobbled up dozens of failing airlines around the country, including the airmail contractor that had employed Charles Lindbergh as chief pilot a few years earlier. In doing so American had built itself into the largest airline holding company in the United States, but

…

paying passengers, thanks to Smith’s DC-3, provided as much business as the mail sacks. A new airplane was also enabling Juan Trippe and Charles Lindbergh to conduct the second phase of their three-way global thrust, this the most far-reaching of all. Pan Am was headed for China. As

…

for the legions of new employees streaming through the front gates. He rendered a stirring account of American’s origins on the mail routes that Charles Lindbergh flew. He gave a pep talk on the competitiveness of the post-deregulation world of aviation—“the nearest thing to legalized warfare” he told his

…

it, “We were ready to own the world.” The visionary Juan Trippe (left) launched Pan Am’s airmail service to South America in 1929, with Charles Lindbergh in the cockpit. “We have shrunken the Earth.” (Smithsonian Institution) Marketing genius C. R. Smith of American Airlines introduced jet travel to America in 1959

…

to the media’s blindness to his struggles. In January 1986 Burr appeared on the cover of Time, joining a hall of fame that included Charles Lindbergh and C. R. Smith of American. Business Week had previously put Burr on the cover, calling him a “new wave capitalist,” a “1980s business giant

…

had sold them to American—which was why Wolf had to get the other half, the eastern half, of the system that Juan Trippe and Charles Lindbergh had pioneered through South America. Dividing the major pieces of Pan Am between them had been easy for Wolf and Allen: while United took Latin

…

telephone system, like the air transport system, was developed as a regulated public utility. Both began by offering products that were remote and prohibitively priced. (Charles Lindbergh devoted two pages of The Spirit of St. Louis to the cost and marvel of long-distance telephony.) Both industries were deregulated at a time

Light This Candle: The Life & Times of Alan Shepard--America's First Spaceman

by Neal Thompson · 2 Jan 2004 · 577pp · 171,126 words

” 16 - “I’m sick . . . should I just hang it up?” 17 - How to succeed in business without really fllying—much 18 - “Captain Shepard? I’m Charles Lindbergh” 19 - “What’s wrong with this ship?” Part III - AFTER SPACE 20 - “When you’ve been to the moon, where else are you going to

…

to write and bind his own book, and he decided it was time to compose his autobiography. At the time, Alan had become enamored of Charles Lindbergh and kept on his bedside table a copy of Lindbergh’s autobiography, We. In a show of how strong Shepard’s ego had already become

…

fascination with—and pursuit of—flying airplanes, an interest that bordered on obsession. Even without his historic flight across the Atlantic in 1927, stories of Charles Lindbergh’s aerial daredevilry were enough to thrill a generation of boys like Shepard, who collected airplane magazines and read and reread Lindbergh’s autobiography, We

…

island, filling the sweltering air with their putrid odors of decay. Shepard’s arrival at Biak almost gave him the chance to meet his hero, Charles Lindbergh. The famous ocean-hopping flyer had spent a few months as a civilian “tech rep” at Biak, showing Navy aviators there how to conserve fuel

…

Corsair’s element.” The manufacturer, Chance-Vought, was constantly modifying the plane to correct the problems and even hired the most famous pilot of all, Charles Lindbergh, to work out kinks and teach other pilots how to handle the temperamental plane. Late in World War II Lindbergh had traveled to Corsair operating

…

perks that others in the Navy, Air Force, and Marines could only dream of. One critic would one day write, “They were heroes not, like Charles Lindbergh, the first man to fly across the Atlantic, because they had done something, but because they were confident they would.” The astronauts, of course, loved

…

most grateful beneficiary of Shepard’s success, but he was hardly alone in believing that Shepard had instantly earned a place beside Wilbur Wright and Charles Lindbergh in the history books. In fact, not since Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight thirty-four years earlier would the American public react so ecstatically to a

…

words a clue that he wasn’t talking just about NASA. Indeed, a cure for the Icy Commander was nigh. 18 “Captain Shepard? I’m Charles Lindbergh” On wintry East Derry evenings, he’d sit at the big wooden table in Nanzie’s kitchen while she cooked dinner at the wood-fired

…

own thoughts,” when an old man wearing rumpled clothes and an upside-down sailor cap approached and introduced himself. “Captain Shepard?” he said. “I’m Charles Lindbergh.” Shepard knew who he was before he’d opened his mouth. The two men had briefly met a few years earlier at a White House

…

, he thought dreamily of a poem: Smaus and Spangler, America’s First Spaceman, p. 53. page 23, “a wine of the gods of which they”: Charles Lindbergh, We. page 24, had already traveled a hundred miles [entire DC-3 scene]: Smaus and Spangler, America’s First Spaceman, pp. 53–66. page 24

…

of Faith; Author interview with Gordon Cooper. page 208, Life . . . “NASA’s house organ”: Faludi, Stiffed, p. 455. page 208, “They were heroes not, like Charles Lindbergh . . .”: Ibid, p. 454. page 208, “I rather enjoyed the insulation”: Shepard, interview with Burke. page 208, “We made them heroes, the first day they were

…

interview with Gene Cernan. page 379, “Don’t you think you’re being a little tough . . .?”: Moonshot, Turner Home Video. 18: “Captain Shepard? I’m Charles Lindbergh” pages 384–385, [Josiah Bartlett’s story]: Donald Lines Jacobus, ed., The Shepard Families of New England, Vol. III (New Haven: The New Haven Colony

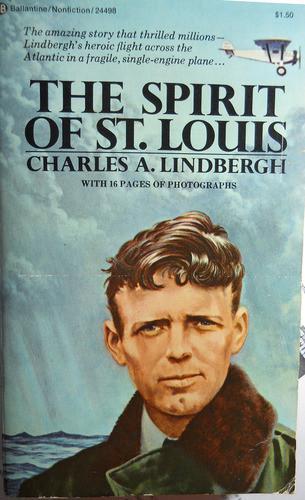

The Spirit of ST Louis

by Charles A. Lindbergh · 2 Jan 1953

it does. "Hold on a minute, please." The next voice is a man's. "I'm calling from St. Louis," I repeat. "My name is Charles Lindbergh. I represent a group of men here who are interested in buying a plane for the New York-to-Paris flight. I’d like to

…

going at sixty-four dollars! --- She's worth ninety if she's worth a cent --- going at sixty-four ---going at sixty four --- sold to Charles Lindbergh at sixty-four dollars!" The auctioneer points his stick at me and turns to the next animal. I'm buying cows for our milk herd

Appetite for America: Fred Harvey and the Business of Civilizing the Wild West--One Meal at a Time

by Stephen Fried · 23 Mar 2010 · 603pp · 186,210 words

vital role in the formative, thrilling, and scary years of the airline business—because Fred’s grandson Freddy was an original partner in TWA with Charles Lindbergh and Henry Ford. Fred Harvey’s “eating houses” were prototypes of the disparate dining experiences that characterize American eating: They had formal, sit-down dining

…

pilots jockeying for the prize. Two were similarly well-financed war heroes; the third was a bold young mail-plane pilot from St. Louis named Charles Lindbergh. Freddy knew Lindbergh from the air corps—the young flyer had attended a two-week reserve officers camp in Kansas City in 1925, where he

…

-four hours. When he touched down at Le Bourget field in Paris, more than a hundred thousand cheering people were waiting there to greet him. Charles Lindbergh became the biggest overnight celebrity the world had ever known. His fame literally redefined fame. Time magazine invented its “Man of the Year” cover feature

…

private investors in the group that bought the original stock. One was railroad magnate William Vanderbilt. The other was Freddy Harvey. A few days later, Charles Lindbergh announced he had joined the company and would map out the route for the fourteen-passenger Transcontinental Air Transport planes. From that moment on, few

…

, news came Friday morning that a plane had spotted four people on a high mesa, waving white shirts in what looked like a distress signal. Charles Lindbergh and his wife immediately took off for New Mexico to be there for the rescue. While they were en route, however, the airline determined that

Skygods: The Fall of Pan Am

by Robert Gandt · 1 Mar 1995 · 371pp · 101,792 words

Corporation of America. They intended to bid on a proposed airmail route between Key West and Havana. Another young man, a lanky airmail pilot named Charles Lindbergh, had just proved the feasibility of transoceanic flight. And in Florida a new airline was being formed for the purpose of flying into Latin America

…

time frame. To Juan Trippe, jets meant faster travel, lower fares, more passengers, expanding airlines—and thus profit. Why did the Primitives never understand that? Charles Lindbergh was Trippe’s advance scout. Even before the war was over, while he was still working for Pratt & Whitney, Lindbergh had entered collapsing Germany to

…

supersonic flight. He even found Germany’s leading builder of exotic aircraft, Willy Messerschmitt, living in a cow barn next to his house in Munich. Charles Lindbergh had an association with Pan Am that went back almost as far as Juan Trippe’s. Lindbergh had served as the captain on the inaugural

…

social programs as well as some expensive items of Cold War hardware. Trippe was even getting flak from America’s greatest hero. Of all people, Charles Lindbergh, Pan Am’s technical consultant, had gone public with his feelings about the SST. “It doesn’t make sense,” the Lone Eagle was telling anyone

…

and a Pan Am board member since the thirties. McKee usually dozed off during board meetings and awakened in time to vote with the majority. Charles Lindbergh was a member, and everyone knew he favored the Everyman airplane as a sensible alternative to the planet-polluting SST. There were the inside directors

…

dean of the Harvard Business School; Norman Chandler, chairman of the Los Angeles Times Mirror Company; Robert B. Anderson, former Secretary of the Treasury; and Charles Lindbergh, who was, perhaps, most unlike the others. An hour after the stockholders’ meeting, the board of directors met in the walnut-paneled boardroom on the

…

Gray and the newcomer, Najeeb Halaby, for the posts of chairman and president. Each director cast his vote. It was unanimous, in favor. And then Charles Lindbergh nominated Trippe for the post of chairman emeritus. Again, a unanimous vote. None of the directors was surprised by Trippe’s choice of Gray to

…

custodians not only of Pan American but of the nation’s fiduciary well-being. One of the faces across the table belonged to the Icon, Charles Lindbergh. Still handsome in his seventy-first year, the Lone Eagle returned Halaby’s gaze. Halaby wondered what Lindbergh was thinking. Was he sympathetic? Hostile? With

War of Shadows: Codebreakers, Spies, and the Secret Struggle to Drive the Nazis From the Middle East

by Gershom Gorenberg · 19 Jan 2021 · 555pp · 163,712 words

Realizing Tomorrow: The Path to Private Spaceflight

by Chris Dubbs, Emeline Paat-dahlstrom and Charles D. Walker · 1 Jun 2011 · 376pp · 110,796 words

Digital Apollo: Human and Machine in Spaceflight

by David A. Mindell · 3 Apr 2008 · 377pp · 21,687 words

War Without Mercy: PACIFIC WAR

by John Dower · 11 Apr 1986 · 516pp · 159,734 words

Reaching for Utopia: Making Sense of an Age of Upheaval

by Jason Cowley · 15 Nov 2018 · 283pp · 87,166 words

The Second World Wars: How the First Global Conflict Was Fought and Won

by Victor Davis Hanson · 16 Oct 2017 · 908pp · 262,808 words

Loonshots: How to Nurture the Crazy Ideas That Win Wars, Cure Diseases, and Transform Industries

by Safi Bahcall · 19 Mar 2019 · 393pp · 115,217 words

America's Bank: The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve

by Roger Lowenstein · 19 Oct 2015 · 589pp · 128,484 words

The Matter of the Heart: A History of the Heart in Eleven Operations

by Thomas Morris · 31 May 2017

Alistair Cooke's America

by Alistair Cooke · 1 Oct 2008 · 369pp · 121,161 words

Duped: Double Lives, False Identities, and the Con Man I Almost Married

by Abby Ellin · 15 Jan 2019 · 340pp · 91,745 words

Between Human and Machine: Feedback, Control, and Computing Before Cybernetics

by David A. Mindell · 10 Oct 2002 · 759pp · 166,687 words

The Abandonment of the West

by Michael Kimmage · 21 Apr 2020 · 378pp · 121,495 words

A Man on the Moon

by Andrew Chaikin · 1 Jan 1994 · 816pp · 242,405 words

Apollo 8: The Thrilling Story of the First Mission to the Moon

by Jeffrey Kluger · 15 May 2017 · 396pp · 112,354 words

Shoot for the Moon: The Space Race and the Extraordinary Voyage of Apollo 11

by James Donovan · 12 Mar 2019

How Democracies Die

by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt · 16 Jan 2018 · 340pp · 81,110 words

Beyond: Our Future in Space

by Chris Impey · 12 Apr 2015 · 370pp · 97,138 words

Rocket Men: The Daring Odyssey of Apollo 8 and the Astronauts Who Made Man's First Journey to the Moon

by Robert Kurson · 2 Apr 2018 · 361pp · 110,905 words

The Power of Glamour: Longing and the Art of Visual Persuasion

by Virginia Postrel · 5 Nov 2013 · 347pp · 86,274 words

The Devil's Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America's Secret Government

by David Talbot · 5 Sep 2016 · 891pp · 253,901 words

Presidents of War

by Michael Beschloss · 8 Oct 2018

The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War (The Princeton Economic History of the Western World)

by Robert J. Gordon · 12 Jan 2016 · 1,104pp · 302,176 words

Top 10 San Diego

by Pamela Barrus and Dk Publishing · 2 Jan 2007 · 135pp · 53,708 words

The Making of the Atomic Bomb

by Richard Rhodes · 17 Sep 2012 · 1,437pp · 384,709 words

A Fiery Peace in a Cold War: Bernard Schriever and the Ultimate Weapon

by Neil Sheehan · 21 Sep 2009 · 589pp · 197,971 words

Failure Is Not an Option: Mission Control From Mercury to Apollo 13 and Beyond

by Gene Kranz · 7 Jan 2000 · 549pp · 162,164 words

USA Travel Guide

by Lonely, Planet

The Woman Who Smashed Codes: A True Story of Love, Spies, and the Unlikely Heroine Who Outwitted America's Enemies

by Jason Fagone · 25 Sep 2017 · 592pp · 152,445 words

The Space Barons: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos

by Christian Davenport · 20 Mar 2018 · 390pp · 108,171 words

Capitalism in America: A History

by Adrian Wooldridge and Alan Greenspan · 15 Oct 2018 · 585pp · 151,239 words

Straight on Till Morning: The Life of Beryl Markham

by Mary S. Lovell · 1 Jan 1983 · 557pp · 159,434 words

Bold: How to Go Big, Create Wealth and Impact the World

by Peter H. Diamandis and Steven Kotler · 3 Feb 2015 · 368pp · 96,825 words

Life on the Rocks: Building a Future for Coral Reefs

by Juli Berwald · 4 Apr 2022 · 495pp · 114,451 words

The Wright Brothers

by David McCullough · 4 May 2015 · 422pp · 114,198 words

The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life

by Alice Schroeder · 1 Sep 2008 · 1,336pp · 415,037 words

The Crash Detectives: Investigating the World's Most Mysterious Air Disasters

by Christine Negroni · 26 Sep 2016 · 269pp · 74,955 words

The Long Weekend: Life in the English Country House, 1918-1939

by Adrian Tinniswood · 2 May 2016

Speed

by Bob Gilliland and Keith Dunnavant · 319pp · 84,772 words

The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order

by Benn Steil · 14 May 2013 · 710pp · 164,527 words

Aftershocks: Pandemic Politics and the End of the Old International Order

by Colin Kahl and Thomas Wright · 23 Aug 2021 · 652pp · 172,428 words

Test Gods: Virgin Galactic and the Making of a Modern Astronaut

by Nicholas Schmidle · 3 May 2021 · 342pp · 101,370 words

Rise of the Machines: A Cybernetic History

by Thomas Rid · 27 Jun 2016 · 509pp · 132,327 words

New York

by Edward Rutherfurd · 10 Nov 2009 · 1,169pp · 342,959 words

Kelly: More Than My Share of It All

by Clarence L. Johnson · 1 Jan 1985 · 218pp · 67,330 words

Moon Shot: The Inside Story of America's Apollo Moon Landings

by Jay Barbree, Howard Benedict, Alan Shepard, Deke Slayton and Neil Armstrong · 1 Jan 1994 · 469pp · 124,784 words

Discover Maui

by Lonely Planet

Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut's Journeys: 50th Anniversary Edition

by Michael Collins and Charles A. Lindbergh · 15 Apr 2019

In a Sunburned Country

by Bill Bryson · 31 Aug 2000

Fodor's California 2014

by Fodor's · 5 Nov 2013 · 1,540pp · 400,759 words

Frommer's California 2009

by Matthew Poole, Harry Basch, Mark Hiss and Erika Lenkert · 2 Jan 2009

How the Post Office Created America: A History

by Winifred Gallagher · 7 Jan 2016 · 431pp · 106,435 words

Chasing the Moon: The People, the Politics, and the Promise That Launched America Into the Space Age

by Robert Stone and Alan Andres · 3 Jun 2019

Top 10 Maui, Molokai and Lanai

by Bonnie Friedman · 16 Feb 2004 · 137pp · 43,960 words

The Forgotten Man

by Amity Shlaes · 25 Jun 2007 · 514pp · 153,092 words

Frommer's California 2007

by Harry Basch, Mark Hiss, Erika Lenkert and Matthew Richard Poole · 6 Dec 2006 · 769pp · 397,677 words

France (Lonely Planet, 8th Edition)

by Nicola Williams · 14 Oct 2010

The Case for Space: How the Revolution in Spaceflight Opens Up a Future of Limitless Possibility

by Robert Zubrin · 30 Apr 2019 · 452pp · 126,310 words

Bill Marriott: Success Is Never Final--His Life and the Decisions That Built a Hotel Empire

by Dale van Atta · 14 Aug 2019 · 520pp · 164,834 words

Aerotropolis

by John D. Kasarda and Greg Lindsay · 2 Jan 2009 · 603pp · 182,781 words

Empire of the Scalpel: The History of Surgery

by Ira Rutkow · 8 Mar 2022 · 509pp · 142,456 words

A Man and His Ship: America's Greatest Naval Architect and His Quest to Build the S.S. United States

by Steven Ujifusa · 9 Jul 2012 · 650pp · 155,108 words

Firepower: How Weapons Shaped Warfare

by Paul Lockhart · 15 Mar 2021

1,000 Places to See in the United States and Canada Before You Die, Updated Ed.

by Patricia Schultz · 13 May 2007 · 2,323pp · 550,739 words

Frommer's Hawaii 2009

by Jeanette Foster · 2 Jan 2008 · 675pp · 344,555 words

Frommer's San Diego 2011

by Mark Hiss · 2 Jan 2007

The Glass Cage: Automation and Us

by Nicholas Carr · 28 Sep 2014 · 308pp · 84,713 words

The Age of Radiance: The Epic Rise and Dramatic Fall of the Atomic Era

by Craig Nelson · 25 Mar 2014 · 684pp · 188,584 words

Our Robots, Ourselves: Robotics and the Myths of Autonomy

by David A. Mindell · 12 Oct 2015 · 265pp · 74,807 words

The Men Who United the States: America's Explorers, Inventors, Eccentrics and Mavericks, and the Creation of One Nation, Indivisible

by Simon Winchester · 14 Oct 2013 · 501pp · 145,097 words

In the Shadow of the Moon: A Challenging Journey to Tranquility, 1965-1969

by Francis French, Colin Burgess and Walter Cunningham · 1 Jun 2010 · 628pp · 170,668 words

Tools of Titans: The Tactics, Routines, and Habits of Billionaires, Icons, and World-Class Performers

by Timothy Ferriss · 6 Dec 2016 · 669pp · 210,153 words

Apollo 11: The Inside Story

by David Whitehouse · 7 Mar 2019 · 308pp · 87,238 words

Atlantic: Great Sea Battles, Heroic Discoveries, Titanic Storms & a Vast Ocean of a Million Stories

by Simon Winchester · 27 Oct 2009 · 522pp · 150,592 words

People Powered: How Communities Can Supercharge Your Business, Brand, and Teams

by Jono Bacon · 12 Nov 2019 · 302pp · 73,946 words

The Dream Machine: The Untold History of the Notorious V-22 Osprey

by Richard Whittle · 26 Apr 2010 · 616pp · 189,609 words

Stephen Fry in America

by Stephen Fry · 1 Jan 2008 · 362pp · 95,782 words

The Right Stuff

by Tom Wolfe · 1 Jan 1979 · 417pp · 147,682 words

The Science and Technology of Growing Young: An Insider's Guide to the Breakthroughs That Will Dramatically Extend Our Lifespan . . . And What You Can Do Right Now

by Sergey Young · 23 Aug 2021 · 326pp · 88,968 words

Hawaii

by Jeff Campbell · 4 Nov 2009

Hawaii Travel Guide

by Lonely Planet

Spitfire: A Very British Love Story

by John Nichol · 16 May 2018 · 522pp · 144,605 words

Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience

by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi · 1 Jul 2008 · 453pp · 132,400 words

The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made

by Walter Isaacson and Evan Thomas · 28 Feb 2012 · 1,150pp · 338,839 words

Moondust: In Search of the Men Who Fell to Earth

by Andrew Smith · 3 Apr 2006 · 409pp · 138,088 words

The Last Man on the Moon: Astronaut Eugene Cernan and America's Race in Space

by Eugene Cernan and Donald A. Davis · 1 Jan 1998 · 453pp · 142,717 words

Predator: The Secret Origins of the Drone Revolution

by Richard Whittle · 15 Sep 2014 · 455pp · 131,569 words

"Live From Cape Canaveral": Covering the Space Race, From Sputnik to Today

by Jay Barbree · 18 Aug 2008 · 386pp · 92,778 words

Endgame: Bobby Fischer's Remarkable Rise and Fall - From America's Brightest Prodigy to the Edge of Madness

by Frank Brady · 1 Feb 2011 · 469pp · 145,094 words

Into the Black: The Extraordinary Untold Story of the First Flight of the Space Shuttle Columbia and the Astronauts Who Flew Her

by Rowland White and Richard Truly · 18 Apr 2016 · 570pp · 151,609 words

Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller

by Alec Nevala-Lee · 1 Aug 2022 · 864pp · 222,565 words

On Time and Water

by Andri Snaer Magnason · 15 Sep 2021 · 272pp · 77,108 words

Fodor's Hawaii 2012

by Fodor's Travel Publications · 15 Nov 2011

The Road Not Taken: Edward Lansdale and the American Tragedy in Vietnam

by Max Boot · 9 Jan 2018 · 972pp · 259,764 words

The Moon: A History for the Future

by Oliver Morton · 1 May 2019 · 319pp · 100,984 words

Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers of the Space Era, 1961-1965

by Francis O. French, Colin Burgess and Paul Haney · 2 Jan 2007 · 647pp · 161,908 words

The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics

by Christopher Lasch · 16 Sep 1991 · 669pp · 226,737 words

The Generals: American Military Command From World War II to Today

by Thomas E. Ricks · 14 Oct 2012 · 812pp · 180,057 words

Citizens of London: The Americans Who Stood With Britain in Its Darkest, Finest Hour

by Lynne Olson · 2 Feb 2010 · 564pp · 178,408 words

Higher: A Historic Race to the Sky and the Making of a City

by Neal Bascomb · 2 Jan 2003 · 366pp · 109,117 words

Kissinger: A Biography

by Walter Isaacson · 26 Sep 2005 · 1,330pp · 372,940 words

Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century

by P. W. Singer · 1 Jan 2010 · 797pp · 227,399 words

Moonshot: The Inside Story of Mankind's Greatest Adventure

by Dan Parry · 22 Jun 2009 · 370pp · 100,856 words

The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism

by Joyce Appleby · 22 Dec 2009 · 540pp · 168,921 words

Future Perfect: The Case for Progress in a Networked Age

by Steven Johnson · 14 Jul 2012 · 184pp · 53,625 words

Fallen Astronauts: Heroes Who Died Reaching for the Moon

by Colin Burgess and Kate Doolan · 14 Apr 2003 · 521pp · 125,749 words

George Marshall: Defender of the Republic

by David L. Roll · 8 Jul 2019

The Great Railroad Revolution

by Christian Wolmar · 9 Jun 2014 · 523pp · 159,884 words

Predictive Analytics: The Power to Predict Who Will Click, Buy, Lie, or Die

by Eric Siegel · 19 Feb 2013 · 502pp · 107,657 words

Hidden Figures

by Margot Lee Shetterly · 11 Aug 2016 · 425pp · 116,409 words

The China Mission: George Marshall's Unfinished War, 1945-1947

by Daniel Kurtz-Phelan · 9 Apr 2018

Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out?

by Bill McKibben · 15 Apr 2019

Getting Better: Why Global Development Is Succeeding--And How We Can Improve the World Even More

by Charles Kenny · 31 Jan 2011 · 272pp · 71,487 words

The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies

by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee · 20 Jan 2014 · 339pp · 88,732 words

The Ultimate Engineer: The Remarkable Life of NASA's Visionary Leader George M. Low

by Richard Jurek · 2 Dec 2019 · 431pp · 118,074 words

A Generation of Sociopaths: How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America

by Bruce Cannon Gibney · 7 Mar 2017 · 526pp · 160,601 words

To the Edges of the Earth: 1909, the Race for the Three Poles, and the Climax of the Age of Exploration

by Edward J. Larson · 13 Mar 2018 · 422pp · 119,123 words

Made to Break: Technology and Obsolescence in America

by Giles Slade · 14 Apr 2006 · 384pp · 89,250 words

Electric City

by Thomas Hager · 18 May 2021 · 248pp · 79,444 words

Frommer's Los Angeles 2010

by Matthew Richard Poole · 28 Sep 2009 · 356pp · 186,629 words

The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America

by Timothy Snyder · 2 Apr 2018

Gusher of Lies: The Dangerous Delusions of Energy Independence

by Robert Bryce · 16 Mar 2011 · 415pp · 103,231 words

You Are Here: From the Compass to GPS, the History and Future of How We Find Ourselves

by Hiawatha Bray · 31 Mar 2014 · 316pp · 90,165 words

Devil's Bargain: Steve Bannon, Donald Trump, and the Storming of the Presidency

by Joshua Green · 17 Jul 2017 · 296pp · 78,112 words

Case for Mars

by Robert Zubrin · 27 Jun 2011 · 437pp · 126,860 words

Restarting the Future: How to Fix the Intangible Economy

by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake · 4 Apr 2022 · 338pp · 85,566 words

MacroWikinomics: Rebooting Business and the World

by Don Tapscott and Anthony D. Williams · 28 Sep 2010 · 552pp · 168,518 words

Time of the Magicians: Wittgenstein, Benjamin, Cassirer, Heidegger, and the Decade That Reinvented Philosophy

by Wolfram Eilenberger · 14 Sep 2020

Future Crimes: Everything Is Connected, Everyone Is Vulnerable and What We Can Do About It

by Marc Goodman · 24 Feb 2015 · 677pp · 206,548 words

Apollo 13

by Jim Lovell and Jeffrey Kluger · 14 Jun 2000 · 538pp · 153,734 words

The Socialist Manifesto: The Case for Radical Politics in an Era of Extreme Inequality

by Bhaskar Sunkara · 1 Feb 2019 · 324pp · 86,056 words

Why the Allies Won

by Richard Overy · 29 Feb 2012 · 624pp · 191,758 words

Western USA

by Lonely Planet

Moon Mexico City: Neighborhood Walks, Food & Culture, Beloved Local Spots

by Julie Meade · 7 Aug 2023 · 527pp · 131,002 words

The Retreat of Western Liberalism

by Edward Luce · 20 Apr 2017 · 223pp · 58,732 words

Seasteading: How Floating Nations Will Restore the Environment, Enrich the Poor, Cure the Sick, and Liberate Humanity From Politicians

by Joe Quirk and Patri Friedman · 21 Mar 2017 · 441pp · 113,244 words

The Wizard of Menlo Park: How Thomas Alva Edison Invented the Modern World

by Randall E. Stross · 13 Mar 2007 · 440pp · 132,685 words

Chief Engineer

by Erica Wagner · 513pp · 154,427 words

Lonely Planet France

by Lonely Planet Publications · 31 Mar 2013

The Last Kings of Shanghai: The Rival Jewish Dynasties That Helped Create Modern China

by Jonathan Kaufman · 14 Sep 2020 · 415pp · 103,801 words

Strategy: A History

by Lawrence Freedman · 31 Oct 2013 · 1,073pp · 314,528 words

Through the Glass Ceiling to the Stars: The Story of the First American Woman to Command a Space Mission

by Eileen M. Collins and Jonathan H. Ward · 13 Sep 2021 · 394pp · 107,778 words

Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World

by Malcolm Harris · 14 Feb 2023 · 864pp · 272,918 words

Soldier, Sailor, Frogman, Spy, Airman, Gangster, Kill or Die: How the Allies Won on D-Day

by Giles Milton · 25 Jan 2019

Eastern USA

by Lonely Planet

An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood

by Neal Gabler · 17 Nov 2010 · 622pp · 194,059 words

When the Heavens Went on Sale: The Misfits and Geniuses Racing to Put Space Within Reach

by Ashlee Vance · 8 May 2023 · 558pp · 175,965 words

All the Money in the World

by Peter W. Bernstein · 17 Dec 2008 · 538pp · 147,612 words

Money Free and Unfree

by George A. Selgin · 14 Jun 2017 · 454pp · 134,482 words

QI: The Second Book of General Ignorance

by Lloyd, John and Mitchinson, John · 7 Oct 2010 · 469pp · 97,582 words

Without Remorse

by Tom Clancy · 2 Jan 1993

Company: A Short History of a Revolutionary Idea

by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge · 4 Mar 2003 · 196pp · 57,974 words

The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz

by Erik Larson · 14 Jun 2020

Wasps: The Splendors and Miseries of an American Aristocracy

by Michael Knox Beran · 2 Aug 2021 · 800pp · 240,175 words

The Rough Guide to Paris

by Rough Guides · 1 May 2023 · 688pp · 190,793 words

Fodor's Essential Belgium

by Fodor's Travel Guides · 23 Aug 2022

And Here's the Kicker: Conversations with 21 Top Humor Writers on Their Craft

by Mike Sacks · 8 Jul 2009 · 588pp · 193,087 words

Tesla: Man Out of Time

by Margaret Cheney · 1 Jan 1981 · 478pp · 131,657 words

The Wisdom of Finance: Discovering Humanity in the World of Risk and Return

by Mihir Desai · 22 May 2017 · 239pp · 69,496 words

Lonely Planet's Best of USA

by Lonely Planet

Life Inc.: How the World Became a Corporation and How to Take It Back

by Douglas Rushkoff · 1 Jun 2009 · 422pp · 131,666 words

Truevine: Two Brothers, a Kidnapping, and a Mother's Quest: A True Story of the Jim Crow South

by Beth Macy · 17 Oct 2016 · 398pp · 112,350 words

The Pentagon: A History

by Steve Vogel · 26 May 2008 · 760pp · 218,087 words

The Rough Guide to New York City

by Martin Dunford · 2 Jan 2009

Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations

by Clay Shirky · 28 Feb 2008 · 313pp · 95,077 words

Philanthrocapitalism

by Matthew Bishop, Michael Green and Bill Clinton · 29 Sep 2008 · 401pp · 115,959 words

In Pursuit of the Perfect Portfolio: The Stories, Voices, and Key Insights of the Pioneers Who Shaped the Way We Invest

by Andrew W. Lo and Stephen R. Foerster · 16 Aug 2021 · 542pp · 145,022 words

Cuba: An American History

by Ada Ferrer · 6 Sep 2021 · 723pp · 211,892 words

13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown

by Simon Johnson and James Kwak · 29 Mar 2010 · 430pp · 109,064 words

Atlas Obscura: An Explorer's Guide to the World's Hidden Wonders

by Joshua Foer, Dylan Thuras and Ella Morton · 19 Sep 2016 · 1,048pp · 187,324 words

To Show and to Tell: The Craft of Literary Nonfiction

by Phillip Lopate · 12 Feb 2013 · 207pp · 64,598 words

The Ice at the End of the World: An Epic Journey Into Greenland's Buried Past and Our Perilous Future

by Jon Gertner · 10 Jun 2019 · 488pp · 145,950 words

Utopia Is Creepy: And Other Provocations

by Nicholas Carr · 5 Sep 2016 · 391pp · 105,382 words

More: The 10,000-Year Rise of the World Economy

by Philip Coggan · 6 Feb 2020 · 524pp · 155,947 words

Globish: How the English Language Became the World's Language

by Robert McCrum · 24 May 2010 · 325pp · 99,983 words

Air Crashes and Miracle Landings: 60 Narratives

by Christopher Bartlett · 11 Apr 2010 · 543pp · 143,135 words

Ayn Rand and the World She Made

by Anne C. Heller · 27 Oct 2009 · 756pp · 228,797 words

Persian Gulf Command: A History of the Second World War in Iran and Iraq

by Ashley Jackson · 15 May 2018 · 714pp · 188,602 words

Top Dog: The Science of Winning and Losing

by Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman · 19 Feb 2013 · 407pp · 109,653 words

The Mask of Sanity: An Attempt to Clarify Some Issues About the So Called Psychopathic Personality

by Hervey Cleckley · 1 Jan 1955 · 612pp · 206,792 words

Accessory to War: The Unspoken Alliance Between Astrophysics and the Military

by Neil Degrasse Tyson and Avis Lang · 10 Sep 2018 · 745pp · 207,187 words

Tools a Visual History: The Hardware That Built, Measured and Repaired the World

by Dominic Chinea · 5 Oct 2022 · 197pp · 49,454 words

The Greatest Capitalist Who Ever Lived: Tom Watson Jr. And the Epic Story of How IBM Created the Digital Age

by Ralph Watson McElvenny and Marc Wortman · 14 Oct 2023 · 567pp · 171,072 words

The Future Is Faster Than You Think: How Converging Technologies Are Transforming Business, Industries, and Our Lives

by Peter H. Diamandis and Steven Kotler · 28 Jan 2020 · 501pp · 114,888 words

We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy

by Ta-Nehisi Coates · 2 Oct 2017 · 349pp · 114,914 words

The Devil's Playground: A Century of Pleasure and Profit in Times Square

by James Traub · 1 Jan 2004 · 341pp · 116,854 words

The Rough Guide to Mexico

by Rough Guides · 15 Jan 2022

Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins

by Garry Kasparov · 1 May 2017 · 331pp · 104,366 words

Future Shock

by Alvin Toffler · 1 Jun 1984 · 286pp · 94,017 words

Spacewalker: My Journey in Space and Faith as NASA's Record-Setting Frequent Flyer

by Jerry Lynn Ross and John Norberg · 31 Jan 2013 · 259pp · 94,135 words

Beggars in Spain

by Nancy Kress · 23 Nov 2004

This America: The Case for the Nation

by Jill Lepore · 27 May 2019 · 86pp · 26,489 words

The Crux

by Richard Rumelt · 27 Apr 2022 · 363pp · 109,834 words

The Race: The Complete True Story of How America Beat Russia to the Moon

by James Schefter · 2 Jan 2000 · 366pp · 119,981 words

The Six-Figure Second Income: How to Start and Grow a Successful Online Business Without Quitting Your Day Job

by David Lindahl and Jonathan Rozek · 4 Aug 2010 · 228pp · 65,953 words

The Radium Girls

by Moore, Kate · 17 Apr 2017

Beyond: The Astonishing Story of the First Human to Leave Our Planet and Journey Into Space

by Stephen Walker · 12 Apr 2021 · 546pp · 164,489 words

Voyage for Madmen

by Peter Nichols · 1 May 2011

Becoming Steve Jobs: The Evolution of a Reckless Upstart Into a Visionary Leader

by Brent Schlender and Rick Tetzeli · 24 Mar 2015 · 464pp · 155,696 words

Creative Selection: Inside Apple's Design Process During the Golden Age of Steve Jobs

by Ken Kocienda · 3 Sep 2018 · 255pp · 76,834 words

Longshot

by David Heath · 18 Jan 2022

Rocket Billionaires: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the New Space Race

by Tim Fernholz · 20 Mar 2018 · 328pp · 96,141 words

Spaceman: An Astronaut's Unlikely Journey to Unlock the Secrets of the Universe

by Mike Massimino · 3 Oct 2016 · 286pp · 101,129 words

Completely Mad: Tom McClean, John Fairfax, and the Epic of the Race to Row Solo Across the Atlantic

by James R. Hansen · 4 Jul 2023 · 362pp · 134,405 words

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

by Joan Didion · 1 Jan 1968 · 184pp · 62,220 words

Merchants of Truth: The Business of News and the Fight for Facts

by Jill Abramson · 5 Feb 2019 · 788pp · 223,004 words

Godforsaken Sea

by Derek Lundy · 15 Feb 1998 · 300pp · 99,432 words

Mission to Mars: My Vision for Space Exploration

by Buzz Aldrin and Leonard David · 1 Apr 2013 · 183pp · 51,514 words

And Never Stop Dancing: Thirty More True Things You Need to Know Now

by Gordon Livingston · 15 Feb 2006

Address Unknown

by Kressmann Taylor · 29 May 2016 · 36pp · 8,421 words

Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts, and the Death of Freedom

by Grace Blakeley · 11 Mar 2024 · 371pp · 137,268 words

Mexico - Mexico City

by Rough Guides · 267pp · 74,238 words

Flying to the Moon: An Astronaut's Story

by Michael Collins · 1 Jan 1976 · 133pp · 47,871 words

On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons From the Twentieth Century

by Timothy Snyder · 14 Sep 2017 · 69pp · 15,637 words

Fly by Wire: The Geese, the Glide, the Miracle on the Hudson

by William Langewiesche · 10 Nov 2009 · 175pp · 54,028 words