Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity

by Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson · 15 May 2023 · 619pp · 177,548 words

Copyright © 2023 by Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson Cover design by Pete Garceau Cover copyright © 2023 by Hachette Book Group, Inc. Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression

…

of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Acemoglu, Daron, author. | Johnson, Simon, author. Title: Power and progress : our thousand-year struggle over technology and prosperity / Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson. Description: First edition. | New York : PublicAffairs, 2023. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2022059230 | ISBN 9781541702530 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781541702554 (ebook) Subjects

…

Digital Damage 9 Artificial Struggle 10 Democracy Breaks 11 Redirecting Technology Photos Bibliographic Essay References Acknowledgments Discover More Image Credits About the Authors Also by Daron Acemoglu Also by Simon Johnson Praise for Power and Progress Daron: To Aras, Arda, and Asu, for a better future Simon: To Lucie, Celia, and Mary

…

/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons; https://commons.wikimedia.org /wiki/File:Ted_Nelson_cropped.jpg 34. Benjamin Lowy/Contour by Getty Images Cody O’Loughlin DARON ACEMOGLU is Institute Professor of Economics at MIT, the university’s highest faculty honor. For the last twenty-five years, he has been researching the historical

…

White House Burning and of the national bestseller 13 Bankers. He works with entrepreneurs, elected officials, and civil-society organizations around the world. ALSO BY DARON ACEMOGLU Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (with James Robinson) The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty (with James

…

1970s, making it more grotesquely unfair than ever just as automation and offshoring jobs changed the game as well. Now with AI, renowned MIT economists Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson explain in their important and lucid book how the transformation of work could make life even worse for most people, or, possibly

…

is long overdue.” —Sir Angus Deaton, 2015 Nobel laureate in economics and coauthor of Deaths of Despair “If you are not already an addict of Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson’s previous books, Power and Progress is guaranteed to make you one. It offers their addictive hallmarks: sparkling writing and a big

The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty

by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson · 23 Sep 2019 · 809pp · 237,921 words

A. Robinson Why Nations Fail Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy PENGUIN PRESS An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC penguinrandomhouse.com Copyright © 2019 by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying

…

CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Names: Acemoglu, Daron, author. | Robinson, James A., 1960– author. Title: The narrow corridor: states, societies, and the fate of liberty / Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson. Description: New York : Penguin Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019009146 (print) | LCCN 2019981140 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735224384 (hardcover

…

this is much less than I owe you. —DA Para Adrián y Tulio. Para mí el pasado, para ustedes el futuro. —JR CONTENTS Also by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson Title Page Copyright Dedication Preface Chapter 1 HOW DOES HISTORY END? Chapter 2 THE RED QUEEN Chapter 3 WILL TO POWER

…

Zoticus, 158–60 Zulu nation, 80–83, 83–87, 120–21 Zuluaga, Luis Eduardo, 353 Zuo Zhuan, 201–2 Zviadists, 93 ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ABOUT THE AUTHORS Daron Acemoglu is an Institute Professor at MIT. In 2005 he received the John Bates Clark Medal, given to economists under age forty judged to have made

Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy

by Daron Acemoğlu and James A. Robinson · 28 Sep 2001

of political and economic crises, (4) the level of economic inequality, (5) the structure of the economy, and (6) the form and extent of globalization. Daron Acemoglu is Charles P. Kindleberger Professor of Applied Economics in the Department of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a member of the Economic

…

, American Economic Review, American Political Science Review, and Journal of Economic Literature. Professor Robinson is on the editorial board of World Politics. Together with Professors Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, Professor Robinson is coauthor of the forthcoming book, The Institutional Roots of Prosperity. Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy

…

DARON ACEMOGLU JAMES A. ROBINSON cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,

…

UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521855266 © Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson 2006 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction

…

memory of my parents, Kevork and Irma, who invested so much in me. To my love, Asu, who has been my inspiration and companion throughout. Daron Acemoglu To the memory of my mother, from whom I inherited my passion for books and my indignation at the injustices of this life. To the

Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty

by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson · 20 Mar 2012 · 547pp · 172,226 words

be missed.” —Peter Diamond, Nobel laureate in economics, 2010 “For those who think that a nation’s economic fate is determined by geography or culture, Daron Acemoglu and Jim Robinson have bad news. It’s manmade institutions, not the lay of the land or the faith of our forefathers, that determine whether

…

repressive institutions and eventual decay or stagnation. Somehow they can generate both excitement and reflection.” —Robert Solow, Nobel laureate in economics, 1987 Copyright © 2012 by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of

…

registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Acemoglu, Daron. Why nations fail : the origins of power, prosperity, and poverty / Daron Acemoglu, James A. Robinson.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. 1. Economics—Political aspects. 2. Economic history—Political aspects. 3. Poverty—Developing countries. 4. Economic

…

/. Map 19: Drawn using data from the 1880 U.S. Census, downloadable at the National Historical Geographic Information System: http://www.nhgis.org/. Map 20: Daron Acemoglu, James A. Robinson, and Rafael J. Santos (2010), “The Monopoly of Violence: Evidence from Colombia,” at http://scholar.harvard.edu/jrobinson/files/ jr_formationofstate.pdf

A World Without Work: Technology, Automation, and How We Should Respond

by Daniel Susskind · 14 Jan 2020 · 419pp · 109,241 words

able to find jobs involving those activities instead. Figure 7.3: Horses and Mules and Tractors on US Farms, 1910–60 (000’s)19 For Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, two leading economists, this version of the changing-pie effect provides a powerful response to Wassily Leontief’s pessimism about the future

…

increasingly capable, many human beings will eventually be driven out of work. In fact, some economists have already seen this happening in the data. When Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo looked at the use of industrial robots in the United States from 1990 to 2007, they found a contemporary case of the

…

of mud, hoping that some if it would stick.” See Jeffrey Sachs, “Government, Geography, and Growth,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2012; and the response from Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, “Response to Jeffrey Sachs,” 21 November 2012, http://whynationsfail.com/blog/2012/11/21/response-to-jeffrey-sachs.html. 4. Data from

…

-the-frame-breaking-act/; and http://statutes.org.uk/site/the-statutes/nineteenth-century/1813-54-geo-3-cap-42-the-frame-breaking-act/. 13. Daron Acemoglu and and James Robinson, Why Nations Fail (London: Profile Books, 2012), pp. 182–83. Perhaps we should be suspicious of her true motivations; this was

…

July 2018). Int-$ (the “international dollar”) is a hypothetical currency that tries to take account of different price levels across different countries. 29. For instance, Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, “Artificial Intelligence, Automation and Work” in Ajay Agrawal, Joshua Gans, and Avi Goldfarb, eds., Economics of Artificial Intelligence (Chicago: Chicago University Press

…

/. 39. US Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/employment-by-major-industry-sector.htm (accessed August 2019). 40. See, for instance, Daron Acemoglu, “Advanced Economic Growth: Lecture 19: Structural Change,” delivered at MIT, 12 November 2017. 41. Jesus Felipe, Connie Bayudan-Dacuycuy, and Matteo Lanzafame, “The Declining Share

…

instance. James Surowiecki, “Robots Won’t Take All Our Jobs,” Wired, 12 September 2017, is another. 2. THE AGE OF LABOR 1. See, for instance, Daron Acemoglu, “Technical Change, Inequality, and the Labor Market,” Journal of Economic Literature 40, no. 1 (2002): 7–72. 2. David Autor, Lawrence Katz, and Alan Krueger

…

History 67, no. 1 (2007): 128–59. 5. From ibid., Data Appendix. Thank you to William Nordhaus for sharing his revised data with me. 6. Daron Acemoglu and David Autor, “Skills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings” in David Card and Orley Ashenfelter, eds., Handbook of Labor Economics, vol. 4

…

(2014): 843–51. 10. From Max Roser and Mohamed Nagdy, “Returns to Education,” https://ourworldindata.org/returns-to-education (accessed 1 May 2018). 11. See Daron Acemoglu, “Technical Change, Inequality, and the Labor Market,” Journal of Economic Literature 40, no. 1 (2002): 7–72. 12. For England, see Alexandra Pleijt and Jacob

…

2018. 88. Lewis, “Can Robots Make Up” and Joseph Quinlan, “Investors Should Wake Up to Japan’s Robotic Future,” Financial Times, 25 September 2017. 89. Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, “Demographics and Automation,” NBER Working Paper No. 24421 (2018). 90. From the Data Appendix to William Nordhaus, “Two Centuries of Productivity Growth

…

. Data from Rodolfo Manuelli and Ananth Seshadri, “Frictionless Technology Diffusion: The Case of Tractors,” American Economic Review 104, no. 4 (2014): 1268–1391. 20. See Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, “The Race Between Machine and Man: Implications of Technology for Growth, Factor Shares, and Employment,” American Economic Review 108, no. 6 (2018

…

Restrepo do not think it is necessarily the case that these new tasks will be created for human beings to do, however. For instance, in Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, “The Wrong Kind of AI? Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Labor Demand,” MIT Working Paper (2019), they explicitly consider the possibility

…

,” Review of Social Economy 65, no. 3 (2007): 279–91. 30. Schloss, Methods of Industrial Remuneration, p. 81. 31. Leontief, “National Perspective,” p. 4. 32. Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, “Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets,” NBER Working Paper No. 23285 (2017). 33. Quoted in Susan Ratcliffe, ed., Oxford Essential

…

(2016). 26. Lynnley Browning and David Kocieniewski, “Pinning Down Apple’s Alleged 0.005% Tax Rate Is Nearly Impossible,” Bloomberg, 1 September 2016, quoted in Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, “It’s Time to Found a New Republic,” Foreign Policy, 15 August 2017. See https://ec.europa.eu/ireland/tags/taxation_en

Falling Behind: Explaining the Development Gap Between Latin America and the United States

by Francis Fukuyama · 1 Jan 2006

of Growth among New World Economies,” paper presented at the meeting of the MacArthur Research Network on Inequality and Economic Performance, Boston, 2001. See also Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson, “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development,” American Economic Review 91 (2001): 1369–1401. This is not the place for

…

fuzzy concept. For one, in a Schumpeterian world of creative destruction, property would be secure only if it were defended by barriers to entry (see Daron Acemoglu, “The Form of Property Rights: Oligarchic vs. Democratic Societies,” Working Paper, Department of Economics [Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2005]). Secondly, property can be made

…

Bernanke and Julio Rotemberg, (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1996), pp. 11–74. 92. Coatsworth, “Structures, Endowments, and Institutions,” p. 140. 93. See Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, “Why Did the West Extend the Franchise? Democracy, Inequality, and Growth in Historical Perspective,” Quarterly Journal of Economics (2000): 1167–1199; and

…

uneven dissemination of industrialization. It is much harder to believe that geography has a large impact on the feasibility of a prosperous industrial society; indeed, Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson tested precisely the idea that geography influenced the dissemination of the British industrial revolution and found no evidence supporting it

…

Log Population Density in 1500 3 4 5 figure 7.7 Absence of Expropriation Risk versus Log Population Density in 1500 in Former Colonies. Source: Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson, “Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation,” in American Economic Review 91 (2001): 1369–1401. 174 Institutional Factors

…

2 3 4 5 6 Log Settler Mortality Rates 7 8 9 figure 7.8 Absence of Expropriation Risk versus Log Settler Mortality Rates. Source: Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson, “Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation,” in American Economic Review 91 (2001): 1369–1401. included gold and

…

Bautista and Camilo García for their excellent research assistance. 2. Angus Maddison, The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective (Paris: OECD, 2003), p. 262. 3. See Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson, “Reversal of Fortune: Geography and Institutions in the Making of the Modern World Income Distribution,” Quarterly Journal of Economics

…

, 2001). 23. See, for example, Guido Tabellini, “Culture and Institutions: Economic Development in the Regions of Europe,” unpublished manuscript, Bocconi University, Milan, Italy, 2005. 24. Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson, “Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation,” American Economic Review 91 (2001): 1369–1401. 25. Simeon Djankov, Rafael

…

.” 41. David J. McCreery, Rural Guatemala, 1760–1940 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1994). 42. Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson, “Colonial Origins of Comparative Development”; and Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson, “Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Development,” in The Handbook of Economic Growth, edited by Philippe Aghion and Steven

…

Factors in Latin America’s Development 50. R. H. Tawney, “The Rise of the Gentry, 1558–1640,” Economic History Review 11 (1941): 1–38. 51. Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson, “The Rise of Europe: Atlantic Trade, Institutional Change, and Economic Growth,” American Economic Review 95 (2005): 546–579. 52

…

. See, for example, Stephen Knack and Philip Keefer, “Institutions and Economic Performance: Cross-Country Tests Using Alternative Measures,” Economics and Politics 7 (1995): 207–227; Daron Acemoglu, James A. Robinson, and Simon Johnson, “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation,” American Economic Review 91, no. 5 (2001): 1369–1401; Acemoglu

…

Rodrik, Where Did All The Growth Go? External Shocks, Social Conflict and Growth Collapses (London: Centre for Economic Policy Research, 1998). 9. For example, see Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation,” American Economic Review 91, no. 5 (2001): 1369–1401

…

; Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Economic and Political Origins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). 10. Philippe C. Schmitter and Guillermo

…

the Institute for Quantitative Social Science, Department of Government, Harvard University. Among his most recent publications are Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (2006), with Daron Acemoglu; and Economía colombiana del siglo XX: Un análisis cuantitativo, coedited with Miguel Urrutia (2007), to be published in English as The Colombian Economy in the

The Meritocracy Trap: How America's Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class, and Devours the Elite

by Daniel Markovits · 14 Sep 2019 · 976pp · 235,576 words

training as workers without high school degrees. By 1991, the educated workers were nearly four times as likely to receive training as the uneducated ones. Daron Acemoglu, “Changes in Unemployment and Wage Inequality: An Alternative Theory and Some Evidence,” American Economic Review 89, no. 5 (December 1999): 1259–78, 1275, https://doi

…

Frank Levy, Teaching the New Basic Skills: Principles for Educating Children to Thrive in a Changing Economy (New York: Free Press, 1996), 19. See also Daron Acemoglu, “Technical Change, Inequality, and the Labor Market,” Journal of Economic Literature 40, no. 1 (March 2002): 41, https://doi.org/10.1257/0022051026976. Hereafter cited

…

for mismatched workers (the average excess years of schooling possessed by overeducated workers) declined. Acemoglu, “Changes in Unemployment and Wage Inequality,” 1271–72, Table 1. Daron Acemoglu’s work tests the robustness of this result against effects concerning the changing composition of the workforce, e.g., a rise of young workers who

…

Review 60 no. 5 (December 1970): 898. Hereafter cited as Hayami and Ruttan, “Agricultural Productivity.” opportunities for profit: Here see Acemoglu, “Technical Change,” 37, and Daron Acemoglu, “Why Do New Technologies Complement Skills? Directed Technical Change and Wage Inequality,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 113, no. 4 (November 1998): 1055. Hereafter cited as

…

in the skill premium [see Acemoglu 1998, and also Michael Kiley 1999].”) unprecedentedly large cohort of college graduates: The data behind these claims come from Daron Acemoglu and David Autor, “Skills, Tasks, and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings,” in Handbook of Labor Economic Economics, vol. 4b, ed. David Card and Orley

…

vocational education, with over 70 percent of young German workers receiving formal workplace training (as compared to only 10 percent in the United States). See Daron Acemoglu and Jörn-Steffen Pischke, “The Structure of Wages and Investment in General Training,” Journal of Political Economy 107, no. 3 (June 1999): 542 (citing an

…

first decade in the labor market, the median German holds between one and two. See Acemoglu and Pischke, “The Structure of Wages,” 549. See also Daron Acemoglu and Jörn-Steffen Pischke, ‘‘Why Do Firms Train? Theory and Evidence,’’ Quarterly Journal of Economics 113 (February 1998): 79–119 (who estimate one), and Christian

…

and Wage Differentials: Germany Versus the U.S.,” Economic Policy 22, no. 49 (January 2007): 74. See also Daron Acemoglu, “Cross-Country Inequality Trends,” Economic Journal 113, no. 485 (February 2003): 121–49; Daron Acemoglu and Jörn-Steffen Pischke, “Worker Well-Being and Public Policy,” Research in Labor Economics 22 (2003): 159–202; Acemoglu

…

Deepening and Wage Differentials: Germany Versus the U.S.,” Economic Policy 22, no. 49 (January 2007): 72–116; Daron Acemoglu, “Cross-Country Inequality Trends,” Economic Journal 113, no. 485 (February 2003): 121–49; Daron Acemoglu and Jörn-Steffen Pischke, “Worker Well-Being and Public Policy,” Research in Labor Economics 22 (2003): 159–202; Acemoglu

…

children’s education. See, e.g., OECD, OECD Skills Outlook 2013, Table A3.1. meritocratic developments in elite education: I borrow the term designed from Daron Acemoglu, “Why Do New Technologies Complement Skills?,” 1055, 1056 (“new technologies are not complementary to skills by nature, but by design”). “the Vietnam War draft laws

The Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of Automation

by Carl Benedikt Frey · 17 Jun 2019 · 626pp · 167,836 words

groups in the American labor market for more than three decades has prompted economists to think differently about technological change. Pathbreaking work by the economists Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo provides a helpful formal model for understanding periods of falling wages, as well as times when wages are growing for everyone, by

…

long run depends on policy choices made in the short run. The mere existence of better machines is not sufficient for long run growth. As Daron Acemoglu and the political scientist James Robinson point out in Why Nations Fail, economic and technological development will move forward only “if not blocked by the

…

that would one day facilitate the Industrial Revolution? One compelling argument is that the road to industrialization began with the discovery of the New World. Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson have demonstrated that where political institutions placed significant checks and balances on the monarchy, the growth of Atlantic trade strengthened

…

in previously unimaginable jobs. Thus, economists have come to conclude that this was a period when technology was working in the interest of labor. As Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo write: “The importance of … new tasks is well illustrated by the technological and organizational changes during the Second Industrial Revolution, which [led

…

could grow, but everyone would still see their wages rise—though at different speeds. The great reversal depicted in figure 10 was first noted by Daron Acemoglu and David Autor.1 It shows that up until the 1970s, wages rose for people at all educational levels, but after the first oil shock

…

CLASS The computer era does not just mark a shift in labor markets. It also marks a shift in how economists think about technological progress. Daron Acemoglu and Pascal Restrepo have recently argued that the wage trends depicted in figure 10 are best understood as a race between enabling and replacing technologies

…

single-purpose robots remain sparse. But even if this means that we underestimate the pervasiveness of robots in the economy, such data are still informative. Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo estimate that each multipurpose robot has replaced about 3.3 jobs in the U.S. economy. Blue-collar people in heavily robotized

…

growth. If AI technologies turn out to be as brilliant as some of us think, we should be more optimistic about the long run. As Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo have pointed out, brilliant technologies are much preferable for labor than mediocre ones because as they make us richer, they create more

…

mediocre technologies, see D. Acemoglu and P. Restrepo, 2018a, “Artificial Intelligence, Automation and Work” (Working Paper 24196, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA). 11. Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo decompose the sources underpinning the demand for labor, showing that the replacement of workers in manufacturing can explain a large part of

Straight Talk on Trade: Ideas for a Sane World Economy

by Dani Rodrik · 8 Oct 2017 · 322pp · 87,181 words

traveling to a point on it such that the elites end up worse off. This type of argument has been invoked in the work of Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, to explain, for example, why many states have blocked policies that would foster industrialization and economic growth during the nineteenth century in

…

Recipes, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2007. 7. The evidence that democracy leads to higher growth is generally considered to be weak. However, the paper Daron Acemoglu, Suresh Naidu, Pascual Restrepo, and James A. Robinson, “Democracy Does Cause Growth,” NBER Working Paper No. 20004, March 2014, makes a strong case that it

…

1997. 11. Mukand and Rodrik, “Political Economy of Liberal Democracy.” 12. See, for example, Carles Boix, Democracy and Redistribution, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2003; Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, “Foundations of Societal Inequality,” Science, vol. 326(5953), 2009: 678–679; and Ben W. Ansell and David J. Samuels, Inequality and

…

H. Bates, Markets and States in Tropical Africa, University of California Press, Berkley, CA, 1981; Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, “Economic Backwardness in Political Perspective,” American Political Science Review, vol. 100(1), 2006: 115–131; Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, Crown, New

…

,” American Economic Review, vol. 84(4), 1994. 6. Mancur Olson, “Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development,” American Political Science Review, vol. 87(3), September 1993: 567–576; Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, “Economic Backwardness in Political Perspective.” 7. Jon Elster, “Rational Choice History: A Case of Excessive Ambition,” American Political Science Review, vol

…

. See Dixit and Weibull, “Political Polarization,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States, vol. 104(18), 2007: United States 7353. 21. Daron Acemoglu and coauthors show that differences in beliefs need not disappear even asymptotically when there is disagreement over the interpretation (that is, informativeness) of the signals

…

received. See Daron Acemoglu, Victor Chernozhukov, and Muhamet Yildiz, “Fragility of Asymptotic Agreement under Bayesian Learning,” unpublished paper, February 2009. 22. See, for example, Arthur T. Denzau and Douglass

…

Rodrik, “The Political Economy of Trade Policy,” in Handbook of International Economics, G. Grossman and K. Rogoff, eds., vol. 3, Amsterdam, North-Holland, 1995. 2. Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, “Economic Backwardness in Political Perspective,” American Political Science Review, vol. 100(1), 2006: 115–131. See also

…

Daron Acemoglu, “Why Not a Political Coase Theorem? Social Conflict, Commitment, and Politics,” Journal of Comparative Economics, vol. 31(4), 2003: 620–652. 3. Raquel Fernandez and

…

Life,” American Economic Review, vol. 80(5), December 1990: 1077–1091; Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, Endogenous Growth Theory, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1998. 13. Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, “Economics versus Politics: Pitfalls of Policy Advice,” NBER Working Paper 18921, March 2013. 14. Leighton and López, Madmen. 15. Leighton and

Growth: A Reckoning

by Daniel Susskind · 16 Apr 2024 · 358pp · 109,930 words

innovation – are ‘not the causes of growth’, they wrote. ‘They are growth.’56 The same frustration continues to be expressed today. ‘This theoretical tradition,’ writes Daron Acemoglu, ‘has for a long time seemed unable to provide a fundamental explanation for economic growth.’57 You can understand their dissatisfaction. Take Romer, for example

…

. This stronger property rights regime, it is argued, was responsible for the economic flourishing that followed, eventually leading to a different revolution – the industrial one. Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson have become the flag bearers for this movement, generalizing these ideas into a popular distinction between ‘extractive’ institutions, which allow a few

…

the last few years, the idea of ‘induced technological change’ has been picked up and sanded into better shape under the stewardship of the economist Daron Acemoglu.9 The idea has also been renamed, becoming known as ‘directed technological change’. This is not only an exercise in rebranding: the new label is

…

technological progress: through creating productive new ideas and taking advantage of their peculiar properties. And it took clearer shape in the last two decades, as Daron Acemoglu refined the observation that we do not need to accept the particular technologies that are thrown up by the market mechanism, but can take control

…

-randomised-controlled-trials. 56 Douglass C. North and Robert Paul Thomas, The Rise of the Western World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973), p. 2. 57 Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James A. Robinson, ‘Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth’, in Handbook of Economic Growth, Vol. 1A, ed. Philippe Aghion

…

, at p. 388. This is the distinction between ‘fundamental’ and ‘proximate’ causes of economic growth. 58 These examples, and others, are definitively set out in Daron Acemoglu, Introduction to Modern Economic Growth (2009). 59 See, for instance, John Gallup, Jeffrey Sachs and Andrew Mellinger, ‘Geography and Economic Development’, International Regional Science Review

…

Weingast, ‘Constitutions and Commitment: The Evolution of Institutions Governing Public Choice in Seventeenth-Century England’, Journal of Economic History, 49:4 (1989), 803–32. 63 Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, Why Nations Fail (New York: Crown, 2012). 64 The former chief economist at the UK Foreign Office Rachel Glennerster, asks: ‘If I

…

Industrial Revolution Was British: Commerce, Induced Invention, and the Scientific Revolution’, Economic History Review, 64:2 (2011), 357–84. 6 Though not necessarily unexplored: see Daron Acemoglu, ‘Localised and Biased Technologies: Atkinson and Stiglitz’s New View, Induced Innovations, and Directed Technological Change’, Economic Journal, 125 (2015), 443–63; Florian Brugger and

…

’s Wage Growth: How Fast is the Gain and What Does It Mean?’, Institute for New Economic Thinking, 28 February 2017. 9 See, for instance, Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity (New York: Public Affairs 2023). 10 Paul Krugman, ‘Errors and Emissions

…

Economics’, Economic Journal 132:644 (2022), 1259–89. 13 www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/. 14 Data from: ourworldindata.org/cheap-renewables-growth. 15 See Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity (New York Public Affairs 2023), p. 389. 16 This chart is

…

Work: Technology, Automation and How We Should Respond (London: Allen Lane, 2020), Chapter 1. 28 Many of these ideas are explored in the work of Daron Acemoglu, the flag bearer for this movement. 29 Susskind, A World Without Work, p. 175. 30 www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Acemoglu-FINAL

The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies

by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee · 20 Jan 2014 · 339pp · 88,732 words

Good Economics for Hard Times: Better Answers to Our Biggest Problems

by Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo · 12 Nov 2019 · 470pp · 148,730 words

Restarting the Future: How to Fix the Intangible Economy

by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake · 4 Apr 2022 · 338pp · 85,566 words

Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy

by Francis Fukuyama · 29 Sep 2014 · 828pp · 232,188 words

Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can't Explain the Modern World

by Deirdre N. McCloskey · 15 Nov 2011 · 1,205pp · 308,891 words

Escape From Rome: The Failure of Empire and the Road to Prosperity

by Walter Scheidel · 14 Oct 2019 · 1,014pp · 237,531 words

The Journey of Humanity: The Origins of Wealth and Inequality

by Oded Galor · 22 Mar 2022 · 426pp · 83,128 words

The Coming Wave: Technology, Power, and the Twenty-First Century's Greatest Dilemma

by Mustafa Suleyman · 4 Sep 2023 · 444pp · 117,770 words

The White Man's Burden: Why the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good

by William Easterly · 1 Mar 2006

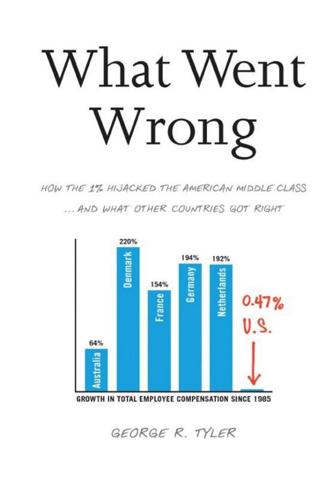

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by George R. Tyler · 15 Jul 2013 · 772pp · 203,182 words

Getting Better: Why Global Development Is Succeeding--And How We Can Improve the World Even More

by Charles Kenny · 31 Jan 2011 · 272pp · 71,487 words

The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor

by William Easterly · 4 Mar 2014 · 483pp · 134,377 words

The Great Surge: The Ascent of the Developing World

by Steven Radelet · 10 Nov 2015 · 437pp · 115,594 words

The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous

by Joseph Henrich · 7 Sep 2020 · 796pp · 223,275 words

The Rise and Fall of Nations: Forces of Change in the Post-Crisis World

by Ruchir Sharma · 5 Jun 2016 · 566pp · 163,322 words

13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown

by Simon Johnson and James Kwak · 29 Mar 2010 · 430pp · 109,064 words

Economists and the Powerful

by Norbert Haring, Norbert H. Ring and Niall Douglas · 30 Sep 2012 · 261pp · 103,244 words

Plutocrats: The Rise of the New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else

by Chrystia Freeland · 11 Oct 2012 · 481pp · 120,693 words

The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality From the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century

by Walter Scheidel · 17 Jan 2017 · 775pp · 208,604 words

The Logic of Life: The Rational Economics of an Irrational World

by Tim Harford · 1 Jan 2008 · 250pp · 88,762 words

Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty

by Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo · 25 Apr 2011 · 370pp · 112,602 words

More: The 10,000-Year Rise of the World Economy

by Philip Coggan · 6 Feb 2020 · 524pp · 155,947 words

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

by Shoshana Zuboff · 15 Jan 2019 · 918pp · 257,605 words

A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy

by Joel Mokyr · 8 Jan 2016 · 687pp · 189,243 words

The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality

by Angus Deaton · 15 Mar 2013 · 374pp · 114,660 words

Radical Markets: Uprooting Capitalism and Democracy for a Just Society

by Eric Posner and E. Weyl · 14 May 2018 · 463pp · 105,197 words

The Means of Prediction: How AI Really Works (And Who Benefits)

by Maximilian Kasy · 15 Jan 2025 · 209pp · 63,332 words

Exponential: How Accelerating Technology Is Leaving Us Behind and What to Do About It

by Azeem Azhar · 6 Sep 2021 · 447pp · 111,991 words

The Innovation Illusion: How So Little Is Created by So Many Working So Hard

by Fredrik Erixon and Bjorn Weigel · 3 Oct 2016 · 504pp · 126,835 words

The Identity Trap: A Story of Ideas and Power in Our Time

by Yascha Mounk · 26 Sep 2023

Economic Dignity

by Gene Sperling · 14 Sep 2020 · 667pp · 149,811 words

Open: The Progressive Case for Free Trade, Immigration, and Global Capital

by Kimberly Clausing · 4 Mar 2019 · 555pp · 80,635 words

Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the World

by Branko Milanovic · 23 Sep 2019

Futureproof: 9 Rules for Humans in the Age of Automation

by Kevin Roose · 9 Mar 2021 · 208pp · 57,602 words

The Third Pillar: How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind

by Raghuram Rajan · 26 Feb 2019 · 596pp · 163,682 words

What Would the Great Economists Do?: How Twelve Brilliant Minds Would Solve Today's Biggest Problems

by Linda Yueh · 4 Jun 2018 · 453pp · 117,893 words

The Great Experiment: Why Diverse Democracies Fall Apart and How They Can Endure

by Yascha Mounk · 19 Apr 2022 · 442pp · 112,155 words

System Error: Where Big Tech Went Wrong and How We Can Reboot

by Rob Reich, Mehran Sahami and Jeremy M. Weinstein · 6 Sep 2021

Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire

by Rebecca Henderson · 27 Apr 2020 · 330pp · 99,044 words

The Wealth of Humans: Work, Power, and Status in the Twenty-First Century

by Ryan Avent · 20 Sep 2016 · 323pp · 90,868 words

Them And Us: Politics, Greed And Inequality - Why We Need A Fair Society

by Will Hutton · 30 Sep 2010 · 543pp · 147,357 words

Wealth, Poverty and Politics

by Thomas Sowell · 31 Aug 2015 · 877pp · 182,093 words

Red Flags: Why Xi's China Is in Jeopardy

by George Magnus · 10 Sep 2018 · 371pp · 98,534 words

Social Democratic America

by Lane Kenworthy · 3 Jan 2014 · 283pp · 73,093 words

Empire of Cotton: A Global History

by Sven Beckert · 2 Dec 2014 · 1,000pp · 247,974 words

Hive Mind: How Your Nation’s IQ Matters So Much More Than Your Own

by Garett Jones · 15 Feb 2015 · 247pp · 64,986 words

More From Less: The Surprising Story of How We Learned to Prosper Using Fewer Resources – and What Happens Next

by Andrew McAfee · 30 Sep 2019 · 372pp · 94,153 words

The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World

by Adrian Wooldridge · 2 Jun 2021 · 693pp · 169,849 words

Exodus: How Migration Is Changing Our World

by Paul Collier · 30 Sep 2013 · 303pp · 83,564 words

The Globalization of Inequality

by François Bourguignon · 1 Aug 2012 · 221pp · 55,901 words

Economics Rules: The Rights and Wrongs of the Dismal Science

by Dani Rodrik · 12 Oct 2015 · 226pp · 59,080 words

10% Less Democracy: Why You Should Trust Elites a Little More and the Masses a Little Less

by Garett Jones · 4 Feb 2020 · 303pp · 75,192 words

The Great Economists: How Their Ideas Can Help Us Today

by Linda Yueh · 15 Mar 2018 · 374pp · 113,126 words

Hit Refresh: The Quest to Rediscover Microsoft's Soul and Imagine a Better Future for Everyone

by Satya Nadella, Greg Shaw and Jill Tracie Nichols · 25 Sep 2017 · 391pp · 71,600 words

Equal Is Unfair: America's Misguided Fight Against Income Inequality

by Don Watkins and Yaron Brook · 28 Mar 2016 · 345pp · 92,849 words

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History

by Kurt Andersen · 14 Sep 2020 · 486pp · 150,849 words

The End of Doom: Environmental Renewal in the Twenty-First Century

by Ronald Bailey · 20 Jul 2015 · 417pp · 109,367 words

The Singularity Is Nearer: When We Merge with AI

by Ray Kurzweil · 25 Jun 2024

Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown

by Philip Mirowski · 24 Jun 2013 · 662pp · 180,546 words

Open: The Story of Human Progress

by Johan Norberg · 14 Sep 2020 · 505pp · 138,917 words

The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War (The Princeton Economic History of the Western World)

by Robert J. Gordon · 12 Jan 2016 · 1,104pp · 302,176 words

The Next Shift: The Fall of Industry and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America

by Gabriel Winant · 23 Mar 2021 · 563pp · 136,190 words

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

by Thomas Piketty · 10 Mar 2014 · 935pp · 267,358 words

Exceptional People: How Migration Shaped Our World and Will Define Our Future

by Ian Goldin, Geoffrey Cameron and Meera Balarajan · 20 Dec 2010 · 482pp · 117,962 words

The Curse of Cash

by Kenneth S Rogoff · 29 Aug 2016 · 361pp · 97,787 words

Taming the Sun: Innovations to Harness Solar Energy and Power the Planet

by Varun Sivaram · 2 Mar 2018 · 469pp · 132,438 words

Capitalism and Its Critics: A History: From the Industrial Revolution to AI

by John Cassidy · 12 May 2025 · 774pp · 238,244 words

Supremacy: AI, ChatGPT, and the Race That Will Change the World

by Parmy Olson · 284pp · 96,087 words

Race Against the Machine: How the Digital Revolution Is Accelerating Innovation, Driving Productivity, and Irreversibly Transforming Employment and the Economy

by Erik Brynjolfsson · 23 Jan 2012 · 72pp · 21,361 words

The Future of the Professions: How Technology Will Transform the Work of Human Experts

by Richard Susskind and Daniel Susskind · 24 Aug 2015 · 742pp · 137,937 words

The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism

by Arun Sundararajan · 12 May 2016 · 375pp · 88,306 words

China's Future

by David Shambaugh · 11 Mar 2016 · 261pp · 57,595 words

The Tyranny of Metrics

by Jerry Z. Muller · 23 Jan 2018 · 204pp · 53,261 words

It's Better Than It Looks: Reasons for Optimism in an Age of Fear

by Gregg Easterbrook · 20 Feb 2018 · 424pp · 119,679 words

Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis

by Robert D. Putnam · 10 Mar 2015 · 459pp · 123,220 words

Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman's OpenAI

by Karen Hao · 19 May 2025 · 660pp · 179,531 words

Adam Smith: Father of Economics

by Jesse Norman · 30 Jun 2018

Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist

by Kate Raworth · 22 Mar 2017 · 403pp · 111,119 words

The Evolution of Everything: How New Ideas Emerge

by Matt Ridley · 395pp · 116,675 words

A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World

by William J. Bernstein · 5 May 2009 · 565pp · 164,405 words

The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves

by Matt Ridley · 17 May 2010 · 462pp · 150,129 words

The Limits of the Market: The Pendulum Between Government and Market

by Paul de Grauwe and Anna Asbury · 12 Mar 2017

Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India

by Shashi Tharoor · 1 Feb 2018 · 370pp · 111,129 words

The Theft of a Decade: How the Baby Boomers Stole the Millennials' Economic Future

by Joseph C. Sternberg · 13 May 2019 · 336pp · 95,773 words

The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets

by Thomas Philippon · 29 Oct 2019 · 401pp · 109,892 words

The Blockchain Alternative: Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy and Economic Theory

by Kariappa Bheemaiah · 26 Feb 2017 · 492pp · 118,882 words

The New Class War: Saving Democracy From the Metropolitan Elite

by Michael Lind · 20 Feb 2020

The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality

by Katharina Pistor · 27 May 2019 · 316pp · 117,228 words

MegaThreats: Ten Dangerous Trends That Imperil Our Future, and How to Survive Them

by Nouriel Roubini · 17 Oct 2022 · 328pp · 96,678 words

The Next Factory of the World: How Chinese Investment Is Reshaping Africa

by Irene Yuan Sun · 16 Oct 2017 · 239pp · 62,311 words

The Hype Machine: How Social Media Disrupts Our Elections, Our Economy, and Our Health--And How We Must Adapt

by Sinan Aral · 14 Sep 2020 · 475pp · 134,707 words

The Captured Economy: How the Powerful Enrich Themselves, Slow Down Growth, and Increase Inequality

by Brink Lindsey · 12 Oct 2017 · 288pp · 64,771 words

Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science (Fully Revised and Updated)

by Charles Wheelan · 18 Apr 2010 · 386pp · 122,595 words

The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy

by Dani Rodrik · 23 Dec 2010 · 356pp · 103,944 words

Profiting Without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All

by Costas Lapavitsas · 14 Aug 2013 · 554pp · 158,687 words

House of Debt: How They (And You) Caused the Great Recession, and How We Can Prevent It From Happening Again

by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi · 11 May 2014 · 249pp · 66,383 words

Adapt: Why Success Always Starts With Failure

by Tim Harford · 1 Jun 2011 · 459pp · 103,153 words

The Shifts and the Shocks: What We've Learned--And Have Still to Learn--From the Financial Crisis

by Martin Wolf · 24 Nov 2015 · 524pp · 143,993 words

Always Day One: How the Tech Titans Plan to Stay on Top Forever

by Alex Kantrowitz · 6 Apr 2020 · 260pp · 67,823 words

The Economics of Belonging: A Radical Plan to Win Back the Left Behind and Achieve Prosperity for All

by Martin Sandbu · 15 Jun 2020 · 322pp · 84,580 words

Power, for All: How It Really Works and Why It's Everyone's Business

by Julie Battilana and Tiziana Casciaro · 30 Aug 2021 · 345pp · 92,063 words

The Enablers: How the West Supports Kleptocrats and Corruption - Endangering Our Democracy

by Frank Vogl · 14 Jul 2021 · 265pp · 80,510 words

The Big Fix: How Companies Capture Markets and Harm Canadians

by Denise Hearn and Vass Bednar · 14 Oct 2024 · 175pp · 46,192 words

Moral Ambition: Stop Wasting Your Talent and Start Making a Difference

by Bregman, Rutger · 9 Mar 2025 · 181pp · 72,663 words

America at the Crossroads: Democracy, Power, and the Neoconservative Legacy

by Francis Fukuyama · 20 Mar 2007 · 214pp · 57,614 words

Bad Samaritans: The Guilty Secrets of Rich Nations and the Threat to Global Prosperity

by Ha-Joon Chang · 4 Jul 2007 · 347pp · 99,317 words

Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 Dec 2007 · 334pp · 98,950 words

The Levelling: What’s Next After Globalization

by Michael O’sullivan · 28 May 2019 · 756pp · 120,818 words

The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 10 Jun 2012 · 580pp · 168,476 words

How to Run a Government: So That Citizens Benefit and Taxpayers Don't Go Crazy

by Michael Barber · 12 Mar 2015 · 350pp · 109,379 words

Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets Are Transforming the Economy--And How to Make Them Work for You

by Sangeet Paul Choudary, Marshall W. van Alstyne and Geoffrey G. Parker · 27 Mar 2016 · 421pp · 110,406 words

Blueprint: The Evolutionary Origins of a Good Society

by Nicholas A. Christakis · 26 Mar 2019

Our Dollar, Your Problem: An Insider’s View of Seven Turbulent Decades of Global Finance, and the Road Ahead

by Kenneth Rogoff · 27 Feb 2025 · 330pp · 127,791 words

Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks From the Stone Age to AI

by Yuval Noah Harari · 9 Sep 2024 · 566pp · 169,013 words

The Genetic Lottery: Why DNA Matters for Social Equality

by Kathryn Paige Harden · 20 Sep 2021 · 375pp · 102,166 words

The Price of Everything: And the Hidden Logic of Value

by Eduardo Porter · 4 Jan 2011 · 353pp · 98,267 words

Average Is Over: Powering America Beyond the Age of the Great Stagnation

by Tyler Cowen · 11 Sep 2013 · 291pp · 81,703 words

Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning About a Highly Connected World

by David Easley and Jon Kleinberg · 15 Nov 2010 · 1,535pp · 337,071 words

The Lonely Century: How Isolation Imperils Our Future

by Noreena Hertz · 13 May 2020 · 506pp · 133,134 words

Why Information Grows: The Evolution of Order, From Atoms to Economies

by Cesar Hidalgo · 1 Jun 2015 · 242pp · 68,019 words

Think Like a Freak

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 11 May 2014 · 240pp · 65,363 words

SuperFreakonomics

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 19 Oct 2009 · 302pp · 83,116 words

Utopia for Realists: The Case for a Universal Basic Income, Open Borders, and a 15-Hour Workweek

by Rutger Bregman · 13 Sep 2014 · 235pp · 62,862 words

The 100-Year Life: Living and Working in an Age of Longevity

by Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott · 1 Jun 2016 · 344pp · 94,332 words

SUPERHUBS: How the Financial Elite and Their Networks Rule Our World

by Sandra Navidi · 24 Jan 2017 · 831pp · 98,409 words

Machine, Platform, Crowd: Harnessing Our Digital Future

by Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson · 26 Jun 2017 · 472pp · 117,093 words

The Power Surge: Energy, Opportunity, and the Battle for America's Future

by Michael Levi · 28 Apr 2013

Owning the Earth: The Transforming History of Land Ownership

by Andro Linklater · 12 Nov 2013 · 603pp · 182,826 words

The New Class Conflict

by Joel Kotkin · 31 Aug 2014 · 362pp · 83,464 words

The New Division of Labor: How Computers Are Creating the Next Job Market

by Frank Levy and Richard J. Murnane · 11 Apr 2004 · 187pp · 55,801 words

Capital Without Borders

by Brooke Harrington · 11 Sep 2016 · 358pp · 104,664 words

The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming

by David Wallace-Wells · 19 Feb 2019 · 343pp · 101,563 words

The Fourth Revolution: The Global Race to Reinvent the State

by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge · 14 May 2014 · 372pp · 92,477 words

Rewriting the Rules of the European Economy: An Agenda for Growth and Shared Prosperity

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 28 Jan 2020 · 408pp · 108,985 words

Innovation and Its Enemies

by Calestous Juma · 20 Mar 2017

The Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter

by Joseph Henrich · 27 Oct 2015 · 631pp · 177,227 words

The Cost of Inequality: Why Economic Equality Is Essential for Recovery

by Stewart Lansley · 19 Jan 2012 · 223pp · 10,010 words

People, Power, and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 22 Apr 2019 · 462pp · 129,022 words

How Democracy Ends

by David Runciman · 9 May 2018 · 245pp · 72,893 words

Corbyn

by Richard Seymour

Accessory to War: The Unspoken Alliance Between Astrophysics and the Military

by Neil Degrasse Tyson and Avis Lang · 10 Sep 2018 · 745pp · 207,187 words

Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events

by Robert J. Shiller · 14 Oct 2019 · 611pp · 130,419 words

Nomad Century: How Climate Migration Will Reshape Our World

by Gaia Vince · 22 Aug 2022 · 302pp · 92,206 words

Markets, State, and People: Economics for Public Policy

by Diane Coyle · 14 Jan 2020 · 384pp · 108,414 words

Automation and the Future of Work

by Aaron Benanav · 3 Nov 2020 · 175pp · 45,815 words