Dennis Ritchie

description: an American computer scientist known for creating the C programming language and contributing to the development of UNIX

34 results

The Art of UNIX Programming

by

Eric S. Raymond

Published 22 Sep 2003

Unix began its life on a scavenged PDP-7 minicomputer[14] like the one shown in Figure 2.1, as a platform for the Space Travel game and a testbed for Thompson's ideas about operating system design. Figure 2.1. The PDP-7. The full origin story is told in [Ritchie79] from the point of view of Thompson's first collaborator, Dennis Ritchie, the man who would become known as the co-inventor of Unix and the inventor of the C language. Dennis Ritchie, Doug McIlroy, and a few colleagues had become used to interactive computing under Multics and did not want to lose that capability. Thompson's PDP-7 operating system offered them a lifeline. Ritchie observes: “What we wanted to preserve was not just a good environment in which to do programming, but a system around which a fellowship could form.

…

Languages rewritten to incorporate lots of feedback. Transparency, Modularity, Multiprogramming, Configuration, Interfaces, Documentation, and Open Source chapters released. Shipped to Mark Taub at AW. Revision 0.0 1999 esr Public HTML draft, first four chapters only. * * * Dedication To Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie, because you inspired me. Preface Preface Unix is not so much an operating system as an oral history. -- Neal Stephenson There is a vast difference between knowledge and expertise. Knowledge lets you deduce the right thing to do; expertise makes the right thing a reflex, hardly requiring conscious thought at all.

…

Jay Maynard contributed most of the material in the MVS case study in Chapter 3. Les Hatton provided many helpful comments on the Languages chapter and motivated the portion of Chapter 4 on Optimal Module Size. David A. Wheeler contributed many perceptive criticisms and some case-study material, especially in the Design part. Russ Cox helped develop the survey of Plan 9. Dennis Ritchie corrected me on some historical points about C. Hundreds of Unix programmers, far too many to list here, contributed advice and comments during the book's public review period between January and June of 2003. As always, I found the process of open peer review over the Web both intensely challenging and intensely rewarding.

Practical C Programming, 3rd Edition

by

Steve Oualline

Published 15 Nov 2011

FORTRAN was designed for number crunching, COBOL was for writing business reports, and PASCAL was for student use. (Many of these languages have far outgrown their initial uses. Nicklaus Wirth has been rumored to have said, “If I had known that PASCAL was going to be so successful, I would have been more careful in its design.”) Brief History of C In 1970 a programmer, Dennis Ritchie, created a new language called C. (The name came about because it superceded the old programming language he was using: B.) C was designed with one goal in mind: writing operating systems. The language was extremely simple and flexible, and soon was used for many different types of programs. It quickly became one of the most popular programming languages in the world.

…

(As an added bonus, teach it about C comments and strings to create a C cross-referencer.) Chapter 19. Ancient Compilers Almost in every kingdom the most ancient families have been at first princes’ bastards.... —Robert Burton C has evolved over the years. In the beginning, it was something thrown together by a couple of hackers (Brian Kernigham and Dennis Ritchie) so that they could use a computer in the basement. Later the C compiler was refined and released as the “Portable C Compiler.” The major advantage of this compiler was that you could port it from machine to machine. All you had to do was write a device configuration. True, writing one was extremely difficult, but the task was a lot easier than writing a compiler from scratch.

…

Breakpoint A location in a program where normal execution is suspended and control is turned over to the debugger. Buffered I/O Input/Output where intermediate storage (a buffer) is used between the source and destination of an I/O stream. Byte A group of eight bits. C A general-purpose computer programming language developed in 1974 at Bell Laboratories by Dennis Ritchie. C is considered to be a medium-to-high-level language. C++ A language based on C invented in 1980 by Bjarne Stroustrup. First called “C with classes,” it has evolved into its own language. C code Computer instructions written in the C language. C compiler Software that translates C source code into machine code.

Protocol: how control exists after decentralization

by

Alexander R. Galloway

Published 1 Apr 2004

Mainstream computer researchers no longer aspire to program intelligence into computers but expect intelligence to emerge from the interactions of small subprograms.”91 This shift, from centralized Machine Man and Other Writings (London: Cambridge University Press, 1996); Villiers de L’Isle Adam, L’Eve future (Paris: Fasquelle, 1921); Raymond Ballour, “Ideal Hadaly,” Camera Obscura no. 15 (Fall 1986); Annette Michelson, “On the Eve of the Future: The Reasonable Facsimile and the Philosophical Toy,” October 29 (1984); Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and the False Maria; Issac Asimov’s three rules for robots; Jasia Reichardt, Robots (London: Thames & Hudson, 1978); John Cohn, Human Robots in Myth and Science (London: Allen & Unwin, 1976). 89. C++ (pronounced “see-plus-plus”) was developed by Bjarne Stroustrup in 1980. Stroustrup’s language was built on the preexisting C language written a decade earlier by Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie (who had previously worked on a lesser version called B). 90. Sherry Turkle, “Who Am We?,” Wired, January 1996, p. 149. 91. Turkle, “Who Am We?,” p. 149. Chapter 3 108 procedural code to distributed object-oriented code, is the most important shift historically for the emergence of artificial life.

…

A significant portion of these computers were, and still are, Unix-based systems. A significant portion of the software was, and still is, largely written in the C or C++ languages. All of these elements have enjoyed unique histories as protocological technologies. The Unix operating system was developed at Bell Telephone Laboratories by Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, and others beginning in 1969, and development continued into the early 1970s. After the operating system’s release, the lab’s parent company, AT&T, began to license and sell Unix as a commercial software product. But, for various legal reasons, the company admitted that it “had no intention of pursuing software as a business.”10 Unix was indeed sold by AT&T, but simply “as is” with no advertising, technical support, or other fanfare.

…

“[I]t fit into more environments with less trouble than just about anything else.”13 Just like a protocol. It is not only computers that experience standardization and mass adoption. Over the years many technologies have followed this same trajectory. The process of standards creation is, in many ways, simply the recognition 11. Salus, A Quarter Century of Unix, p. 2. 12. See Dennis Ritchie, “The Development of the C Programming Language,” in History of Programming Languages II, ed. Thomas Bergin and Richard Gibson (New York: ACM, 1996), p. 681. 13. Bjarne Stroustrup, “Transcript of Presentation,” in History of Programming Languages II, ed. Thomas Bergin and Richard Gibson (New York: ACM, 1996), p. 761.

Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents

by

Lisa Gitelman

Published 26 Mar 2014

My second example in this chapter, John Lions’s “Commentary on the Sixth Edition unix Operating System,” offers a way to think about xerography and the digital together, to begin to see how the one helped to make sense of the other and vice versa. Lions’s commentary was a self-published textbook for computer science students at the University of New South Wales. unix was an operating system written in 1969 by Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, and members of the computer science research group at Bell Labs, the research arm of at&t . Rather than distribute unix commercially, at&t licensed the software to researchers worldwide for a nominal sum, sending both machine code and source code out to its licensees. The software was proprietary, though, so Lions could not legally distribute the commentary (which included the source code) in any but his XEROGRAPHERS OF THE MIND 97 immediate, licensed, context.

…

Salus, A Quarter Century of unix (Reading, MA: Addison Wesley, 1994), 34–36. See Dennis M. Ritchie and Ken Thompson, “The unix Time-Sharing System,” Communications of the acm 17, no. 7 (1974): 365–75. Frederick P. Brooks Jr., The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering, corrected ed. (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1982), 134. Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie, “Unix Programmer’s Manual,” accessed 25 May 2006, http://cm.bell-labs.com/cm/cs/who/dmr/mainintro.html. See also Salus, A Quarter Century of Unix, chapter 6. Christopher Kelty, “Geeks, Social Imaginaries, and Recursive Publics,” Cultural Anthropology 20, no. 2 (2005): 198. On bootstrapping, see also Bowker, Memory Practices in the Sciences, 141.

Rebel Code: Linux and the Open Source Revolution

by

Glyn Moody

Published 14 Jul 2002

Wirzenius and Linus were about to discover Unix. 2 The New GNU Thing THE PROGRAM THAT CAUSED LINUS’S HEART to beat a little faster in the fall of 1990 was Digital’s Ultrix, one of the many commercial variants of the Unix operating system. Others included Sun’s Solaris, IBM’s AIX and Hewlett-Packard’s HP-UX. Despite the confusion of versions, they all derived from the original Unix system created by Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie at AT&T’s Bell Labs in 1969–the year Linus was born. Peter Salus, author of A Quarter Century of Unix, generally regarded as the standard history of the operating system, explains how Unix came about: “At the beginning of 1969, there was a group of people working on a project that was MIT, AT&T Bell Labs and General Electric.

…

In February 1969, they were several millions behind budget, they were months and months behind schedule, and the powers that be at Bell Labs decided this is never going to go anywhere, and they pulled out of the arrangement. “And that left the not-quite half-dozen Bell employees who had been involved in the project without anything to do,” Salus continues, “but with a large number of ideas they had picked up from the cross-fertilization with GE and with MIT.” Among them were Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie; they decided that a “cut-down version of this incredible project could be doable for a much smaller machine” than the original project used. “The machine that the project was working on was a GE 645, and it was what you would call a large piece of iron,” Salus says. “Dennis and Ken began plotting down some ideas on a blackboard,” he continues.

…

He uploaded just the source code. Token gesture or not, the sources came with surprisingly full release notes–some 1,800 words. These emphasized that “this version is meant mostly for reading”–hacker’s fare, that is, building on a tradition of code legibility that had largely begun with the creation of C, as Dennis Ritchie had noted in his 1979 history of Unix. And highly readable the code is, too. As well as being well laid out with ample use of space and indentation to delineate the underlying structure, it is also fully commented, something that many otherwise fine hackers omit. Some of the annotations are remarkably chirpy, and they convey well the growing excitement that Linus obviously felt as the kernel began to take shape beneath his fingers:This is GOOD CODE!

Fancy Bear Goes Phishing: The Dark History of the Information Age, in Five Extraordinary Hacks

by

Scott J. Shapiro

The research community did not love Multics either. Less concerned with its bad security, computer scientists were unhappy with its design. Multics was complicated and bloated—a typical result of decision by committee. In 1969, part of the Multics group broke away and started over. This new team, led by Dennis Ritchie and Ken Thompson, operated out of an attic at Bell Labs using a spare PDP-7, a “minicomputer” built by the Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) that cost ten times less than an IBM mainframe. The Bell Labs team had learned the lesson of Multics’ failure: Keep it simple, stupid. Their philosophy was to build a new multiuser system based on the concept of modularity: every program should do one thing well, and, instead of adding features to existing programs, developers should string together simple programs to form “scripts” that can perform more complex tasks.

…

Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Twitter servers run on Linux, an operating system that, as its name suggests, is explicitly modeled after UNIX (though for intellectual-property reasons was rewritten with different code). Home routers, Alexa speakers, and smart toasters also run Linux. For decades, Microsoft was the lone holdout. But in 2018, Microsoft shipped Windows 10 with a full Linux kernel. UNIX has become so dominant that it is part of every computer system on the planet. As Dennis Ritchie admitted in 1979, “The first fact to face is that UNIX was not developed with security, in any realistic sense, in mind; this fact alone guarantees a vast number of holes.” Some of these vulnerabilities were inadvertent programming errors. Others arose because UNIX gave users greater privileges than they strictly needed, but made their lives easier.

…

And not until v4 was the system first described in public. See, e.g., Douglas McIlroy, A Research UNIX Reader: Annotated Excerpts from the Programmer’s Manual, 1971–1986, https://www.cs.dartmouth.edu/~doug/reader.pdf. direct descendant: See chart at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/77/Unix_history-simple.svg. “The first fact to face”: Dennis Ritchie, “On the Security of UNIX,” UNIX Programmer’s Manual, Volume 2 (Murray Hill, NJ: Bell Telephone Laboratories, 1979), 592. UNIX gave users greater privileges: Matt Bishop wrote a UNIX security report in 1981 listing twenty-one vulnerabilities falling into six categories. See Matt Bishop, “Reflections on UNIX Vulnerabilities,” Annual Computer Security Applications Conference, 2009.

Masterminds of Programming: Conversations With the Creators of Major Programming Languages

by

Federico Biancuzzi

and

Shane Warden

Published 21 Mar 2009

From the base language, you get a basic syntactic and semantic structure, you get useful libraries, and you become part of a culture. Had I not built on C, I would have based C++ on some other language. Why C? I had Dennis Ritchie, Brian Kernighan, and other Unix greats just down (or across) the hall from me in Bell Labs’ Computer Science Research Center, so the question may seem redundant. But it was a question I took seriously. In particular, C’s type system was informal and weakly enforced (as Dennis Ritchie said, “C is a strongly typed, weakly checked language”). The “weakly checked” part worried me and causes problems for C++ programmers to this day. Also, C wasn’t the widely used language it is today.

…

With Unix, you had an operating system that was suddenly very portable. Was that because they could port it, or because they had a desire to migrate existing software to different hardware platforms as they changed? Al: As Unix evolved, computers evolved even faster. One of the big developments in Unix occurred when Dennis Ritchie created the C language to build the third version of Unix. This made Unix portable. In a relatively few years when I was at Bell Labs, we had Unix running on everything from minicomputers to the world’s biggest supercomputers because it had been written in C, and we had portable compiler technology, which could be used to make C compilers quickly for new machines.

…

Brian: Unless the developer has a really good idea of what the software is going to be used for, there’s a very high probability that the software will turn out badly. In some fortunate cases, the developer understands the user because the developer is also going to be a user. One of the reasons why the early Unix system was so good, so well suited to the needs of programmers, was that its creators, Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie, wanted a system for their own software development; as a result, Unix was just great for programmers writing new programs. The same is true of the C programming language. If the developers don’t know and understand the application well, then it’s crucial to get as much user input and experience as possible.

Coders at Work

by

Peter Seibel

Published 22 Jun 2009

He has spent a career working on whatever he finds interesting, which has, at various times, included analog computing, systems programming, regular expressions, and computer chess. Hired as a researcher at Bell Labs to work on the MULTICS project, after Bell Labs pulled out of MULTICS, Thompson went on, with Dennis Ritchie, to invent Unix, an endeavor for which he fully expected to be fired. He also invented the B programming language, the precursor to Dennis Ritchie's C. Later he got interested in computer chess, building Belle, the first special-purpose chess computer and the strongest computerized chess player of its time. He also helped expand chess endgame tablebases to cover all four- and five-piece endgames.

…

Otherwise I read it and I may understand it right after I read it but then it's gone. If I understand the structure of it, then it's part of me and I'll understand it. Seibel: In your Turing Award talk you mentioned that if Dan Bobrow had been forced to use a PDP-11 instead of the more powerful PDP-10 he might have been receiving the award that day instead of you and Dennis Ritchie. Thompson: I was just trying to say it was serendipitous. Seibel: Do you think you benefited to being constrained by the less powerful machine? Thompson: There was certainly a benefit that it was small and efficient. But I think that was the kind of code we wrote anyway. But it was more the fact that it was right at the cusp of a revolution of minicomputers.

…

It's just monstrously slow, but computers have gotten 1,000 times faster since GCC came out. So it may seem like it's getting faster because it's not getting slower as much as computers are getting faster underneath it. Seibel: On a somewhat related note, what about garbage collection? With Java, GC has finally made it into the mainstream. As Dennis Ritchie once said, C is actively hostile to garbage collection. Is it good that folks are moving toward garbage-collected languages—is it a technology that deserves to finally be in mainstream use? Thompson: I don't know. I'm schizophrenic on the subject. If you're writing an operating system or a C compiler or something that's used by lots and lots of people, I think garbage collection is a mistake, almost.

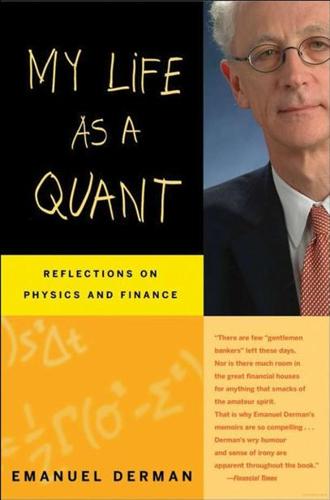

My Life as a Quant: Reflections on Physics and Finance

by

Emanuel Derman

Published 1 Jan 2004

Area 10, the lowest number, was the crown jewel, a pure research center where first-rate scientists and engineers carried out advanced research without the burden of having to seek government funding. As a regulated monopoly in those precompetitive days,AT&T could charge its consumers whatever it needed to pay the bills. Area 10 was absolutely world-class in computer science and physics. Brian Kernighan, Dennis Ritchie, and their coworkers had invented the now legendary C programming language and the UNIX operating system there, and then built the entire suite of programming utilities that carried nerdily cute names like awk, ed, sed, finger, lex, and yacc. Area 10 had played a large role in evangelizing the dual view of programs as both tools and text, written not only to control electronic machines but also to to be understood and manipulated by people.

…

My only exception had been at the University of Cape Town, in 1965, when I used punched cards to enter a vocabulary into the machine and then created randomly generated short poems. I had always thought of that effort as a childish lark. But at AT&T in 1980, the whole firm was embracing C, the simultaneously graceful and yet practical language invented by Dennis Ritchie about ten years earlier at Murray Hill. He had devised C to be a high-level tool with which to write portable versions of UNIX, the operating system also invented there by Ken Thompson and Ritchie.2 Now, everything from telephone switching systems to word-processing software was being written in C, on UNIX, all with amazing style.

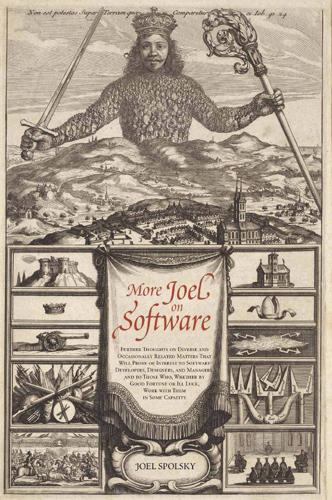

Joel on Software

by

Joel Spolsky

Published 1 Aug 2004

This kind of string handling and string concatenation was good enough for Kernighan and Ritchie,2 but it has its problems. Here's a problem. Suppose you have a bunch of names that you want to append together in one big string: __________ 1. For more information on character strings, see www-ee.eng.hawaii.edu/Courses/EE150/Book/chap7/subsection2.1.1.2.html. 2. Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie, The C Programming Language, Second Edition (Prentice Hall, 1988). char bigString[1000]; /* I never know how much to allocate... */ bigString[0] = '\0'; strcat(bigString,"John, "); strcat(bigString,"Paul, "); strcat(bigString,"George, "); strcat(bigString,"Joel "); This works, right? Yes.

…

For example, on some PCs the character code 130 would display as é, but on computers sold in Israel it was the Hebrew letter Gimel (), so when Americans would send their résumés to Israel they would arrive as rsums. In many cases, such as Russian, there were lots of different ideas of what to do with the upper 128 characters, so you couldn't even reliably interchange Russian documents. __________ 3. Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie, The C Programming Language (Prentice Hall, 1978). 4. For more information on ASCII characters, see www.robelle.com/library/smugbook/ascii.html. Eventually, this OEM free-for-all got codified in the ANSI standard. In the ANSI standard, everybody agreed on what to do below 128, which was pretty much the same as ASCII, but there were lots of different ways to handle the characters from 128 and up, depending on where you lived.

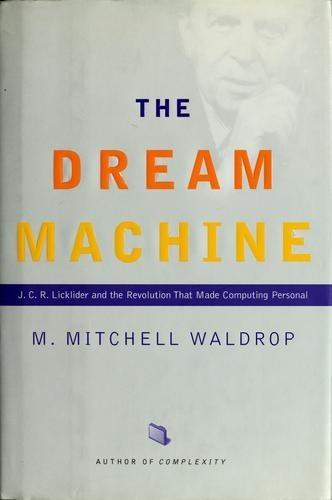

The Dream Machine: J.C.R. Licklider and the Revolution That Made Computing Personal

by

M. Mitchell Waldrop

Published 14 Apr 2001

Bell Labs' managers had grown increasingly impatient with Multics-they needed a computer system now, not in some far-distant fu- ture-and work on it there was already close to a standstill. The January decision simply shut down that last little bit of activity and put the laboratory on track to buy a conventional GE 635 computer that would operate in a conventional batch-processing mode. But then a funny thing happened: two of Bell's former Multicians, Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie, began suffering from withdrawal pangs. As baroque as Multics was, it was responsive, interactive, alive. And once they no longer had it, Thompson and Ritchie found themselves craving that interactiv- ity. So, good hackers that they were, they decided to write a little time-sharing system of their own.

…

Actually, Unix was "free" only because AT&T wasn't allowed to sell it; until the breakup, in 1982, the company was a regulated telephone monopoly and as such was barred from doing much of anything in the computer business. But Unix was hackable because it was about as open as a system could get. Order the data tapes (nominal charge: $150 for materials), and you got the complete source code, which was yours to modify as you wished. Dennis Ritchie and Ken Thompson had created Unix for their own use back in 1969, after Bell Labs' withdrawal from the Multics partnership, and the project had retained that loose, hands-on feeling ever since. Then, too, Ritchie and Thompson had created Unix with hacking in mind, deriving its basic structure from Fernando Corbato's CTSS via Multics-namely, a tool kit of utilities and software routines that the user could call upon to per- form specific tasks, all built on top of an invisible "kernel" of software that func- tioned as the autonomic nervous system of the computer, seamlessly moving bits through the machine at a level below the user's consciousness.

…

C. R. LICklIder, OH 150; Stephen Lukasik, OH 232; John William Mauchly, OH 26, OH 44; Kathleen Mauchly, OH 11 ;John McCarthy, OH 156; Alexander A. McKenzie, OH 185; Marvin L. Minsky, OH 179; Allen Newell, OH 227; Bernard More OlIver, OH 097; Severo Ornstein, OH 183, OH 258; RaJ Reddy, OH 231; Dennis Ritchie, OH 239; Lawrence G. Roberts, OH 159; Douglas T. Ross, OH 65, OH 178;Jack P. Ruina, OH 163;Jules I. Schwartz, OH 161; Ivan Sutherland, OH 171; Robert A. Tay- lor, OH 154; Ken Thompson, OH 239;Joseph F. Traub, OH 70, OH 89, OH 94; Keith W. Uncapher, OH 174; Frank M. Verzuh, OH 63; David A. Walden, OH 181; Willis H.

Peer-to-Peer

by

Andy Oram

Published 26 Feb 2001

In this chapter we’ll give some background on reputation and issues to consider when developing a reputation system. Early reputation systems online The online world carries over many kinds of reputation from the real world. The name “Dennis Ritchie” is still recognizable, whether listed in a phone book or in a posting to comp.theory. Of course, there is a problem online—how can you be sure that the person posting to comp.theory is the Dennis Ritchie? And what happens when “Night Avenger” turns out to be Brian Kernighan posting under a pseudonym? These problems of identity—covered earlier in this chapter—complicate the ways we think about reputations, because some of our old assumptions no longer hold.

How We Got Here: A Slightly Irreverent History of Technology and Markets

by

Andy Kessler

Published 13 Jun 2005

Software and Networks In 1964, a consortium of MIT, Bell Labs and General Electric (which made computers for a while) announced a system called Multics, which was a time-sharing computer with users connected via a video display terminal and an electric typewriter. A green screen beat punched cards, but computers were still mainly used for number crunching tasks. In 1969, Bell Labbers Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie, with beards a la ZZ Top, fixed the then dead Multics software. They wrote a simpler version for Digital Equipment Corporation’s PDP mini-computers and named it UNICS, which stood for “castrated Multics.” This is the type of joke that programmers live for at 4 AM while waiting for their programs to compile.

Kill It With Fire: Manage Aging Computer Systems

by

Marianne Bellotti

Published 17 Mar 2021

The story of Linux kicks off with the breakup of Bell Systems in 1982, nearly a decade before its creation. A 1956 consent decree against AT&T had forbidden the telecom giant from “any business other than the furnishing of common carrier communications services.” This meant that when Bell Labs computer scientists Dennis Ritchie, Ken Thompson, and Rudd Canaday began developing Unix in the 1970s, no one was sure whether AT&T was allowed to sell it. The lawyers at AT&T decided to play it safe and allow it to be sold to academic and research institutions with a copy of its source code along with the software.6 Having the source code made it easy to port Unix to different machines as well as modify and debug it.

The C Programming Language

by

Brian W. Kernighan

and

Dennis M. Ritchie

Published 15 Feb 1988

C is not a ``very high level'' language, nor a ``big'' one, and is not specialized to any particular area of application. But its absence of restrictions and its generality make it more convenient and effective for many tasks than supposedly more powerful languages. C was originally designed for and implemented on the UNIX operating system on the DEC PDP-11, by Dennis Ritchie. The operating system, the C compiler, and essentially all UNIX applications programs (including all of the software used to prepare this book) are written in C. Production compilers also exist for several other machines, including the IBM System/370, the Honeywell 6000, and the Interdata 8/32.

Artificial Unintelligence: How Computers Misunderstand the World

by

Meredith Broussard

Published 19 Apr 2018

Every time a programmer learns a new language, she does the same thing first: she writes a “Hello, world” program. If you study programming at coding boot camp or at Stanford or at community college or online, you’ll likely be asked to write one. “Hello, world” is a reference to the first program in the iconic 1978 book The C Programming Language by Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie, in which the reader learns how to create a program (using the C programming language) to print “Hello, world.” Kernighan and Ritchie worked at Bell Labs, the think tank that is to modern computer science what Hershey is to chocolate. (AT&T Bell Labs was also kind enough to employ me for several years.)

More Joel on Software

by

Joel Spolsky

Published 25 Jun 2008

Microsoft flipped its corporate strategy 180 degrees based on a single compelling e-mail that Steve Sinofsky wrote called “Cornell is Wired” (www.cornell. edu/about/wired/). The people who get to decide the terms of the 72 More from Joel on Software debate are the ones who can write. The C programming language took over because The C Programming Language by Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie (Prentice Hall, 1988) was such a great book. So anyway, those were the highlights of CS: CS 115, in which I learned to write, one lecture in dynamic logic, in which I learned not to go to graduate school, and CS 322, in which I learned the rites and rituals of the Unix church and had a good time writing a lot of code.

Hacking Exposed: Network Security Secrets and Solutions

by

Stuart McClure

,

Joel Scambray

and

George Kurtz

Published 15 Feb 2001

P:\010Comp\Hacking\381-6\ch01.vp Friday, September 07, 2001 10:37:39 AM Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen Hacking / Hacking Exposed: Network Security / McClure/Scambray / 2748-1 / Chapter 8 CHAPTER 8 X I N U g n i k Hac 305 P:\010Comp\Hacking\748-1\ch08.vp Wednesday, September 20, 2000 10:21:26 AM Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen 306 Hacking / Hacking Exposed: Network Security / McClure/Scambray / 2748-1 / Chapter 8 Hacking Exposed: Network Security Secrets and Solutions S ome feel drugs are about the only thing more addicting than obtaining root access on a UNIX system. The pursuit of root access dates back to the early days of UNIX, so we need to provide some historical background on its evolution. THE QUEST FOR ROOT In 1969, Ken Thompson, and later Dennis Ritchie, of AT&T decided that the MULTICS (Multiplexed Information and Computing System) project wasn’t progressing as fast as they would have liked. Their decision to “hack up” a new operating system called UNIX forever changed the landscape of computing. UNIX was intended to be a powerful, robust, multiuser operating system that excelled at running programs, specifically, small programs called tools.

The Deep Learning Revolution (The MIT Press)

by

Terrence J. Sejnowski

Published 27 Sep 2018

Westlake, Capitalism without Capital: The Rise of the Intangible Economy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017), 4. 46. W. Brian Arthur, “The second economy?” McKinsey Quarterly October, 2011. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our -insights/the-second-economy/. 47. “Hello, world!” is a test message from an example program in Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie’s classic book The C Programming Language (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1978). Chapter 13 1. Videos of the talks by discussants at the Grand Challenges for Science in the 21st Century conference can be found at https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query =Grand+Challenges++for+Science+in+the+21st+Century. 2.

Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution

by

Howard Rheingold

Published 24 Dec 2011

Ken Thompson started duplicating Unix source code and utilities on magnetic tapes, labeling and documenting them with the words “Love, Ken,” and mailing the tapes to friends.54 Unix software became the OS of the Net. In turn, the Internet created a rich environment for Unix programmers to establish one of the earliest global virtual communities. Dennis Ritchie, one of the Unix creators, wrote: “What we wanted to preserve was not just a good environment in which to do programming, but a system around which a fellowship could form. We knew from experience that the essence of communal computing, as supplied by remote-access, time-shared machines, is not just to type programs into a terminal instead of a keypunch, but to encourage close communication.”55 However, in 1976, AT&T halted publication of Unix source code; the original, eventually banned, books became “possibly the most photocopied works in computing history.”56 At around the same time the Unix community was coalescing, MIT’s Artificial Intelligence research laboratory changed the kind of computers it used.

Hacking Capitalism

by

Söderberg, Johan; Söderberg, Johan;

This in turn implies lower costs to innovate and thus less dependency on government or business support. UNIX is a landmark in the history of software development but it is also archetypical in that it partially emerged to the side of institutions.7 The two enthusiasts responsible for UNIX, Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie, had been working on an operating system for Bell Laboratory, a subsidiary of AT&T, for some time. They had become disheartened and started their own, small-scale experiment to build an operating system. The hobby project was taken up in part to the side of, in part under the wings of, the American telephone company.

Code: The Hidden Language of Computer Hardware and Software

by

Charles Petzold

Published 28 Sep 1999

The directories (sometimes called folders) become a way to group related files. The hierarchical file system—and some other features of MS-DOS 2.0—were borrowed from an operating system named UNIX, which was developed in the early 1970s at Bell Telephone Laboratories largely by Ken Thompson (born 1943) and Dennis Ritchie (born 1941). The funny name of the operating system is a play on words: UNIX was originally written as a less hardy version of an earlier operating system named Multics (which stands for Multiplexed Information and Computing Services) that Bell Labs had been codeveloping with MIT and GE. Among hard-core computer programmers, UNIX is the most beloved operating system of all time.

The Joy of Clojure

by

Michael Fogus

and

Chris Houser

Published 28 Nov 2010

., “The Evolution of Lisp” (1992), www.dreamsongs.com/Files/HOPL2-Uncut.pdf. 1959 COBOL Design by committee Edsger Dijkstra, “EWD 498: How Do We Tell Truths That Might Hurt?” in Selected Writings on Computing: A Personal Perspective (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1982). 1968 Smalltalk Alan Kay Adele Goldberg, Smalltalk-80: The Language and Its Implementation (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1983). 1972 C Dennis Ritchie Brian W. Kernighan and Dennis M. Ritchie, The C Programming Language (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1988). 1972 Prolog Alain Colmerauer Ivan Bratko, PROLOG: Programming for Artificial Intelligence (New York: Addison-Wesley, 2000). 1975 Scheme Guy Steele and Gerald Sussman Guy Steele and Gerald Sussman, the “Lambda Papers,” mng.bz/sU33. 1983 C++ Bjarne Stroustrup Bjarne Stroustrup, The Design and Evolution of C++ (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1994). 1986 Erlang Telefonaktiebolaget L.

Autotools

by

John Calcote

Published 20 Jul 2010

The input stream must also include the definitions of all referenced macros—both those that Autoconf provides and those that you write yourself. The macro language used in Autoconf is called M4. (The name means M, plus 4 more letters, or the word Macro.[36]) The m4 utility is a general-purpose macro language processor originally written by Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie in 1977. While you may not be familiar with it, you can find some form of M4 on every Unix and Linux variant (as well as other systems) in use today. The prolific nature of this tool is the main reason it's used by Autoconf, as the original design goals of Autoconf stated that it should be able to run on all systems without the addition of complex tool chains and utility sets.[37] Autoconf depends on the existence of relatively few tools: a Bourne shell, M4, and a Perl interpreter.

Fire in the Valley: The Birth and Death of the Personal Computer

by

Michael Swaine

and

Paul Freiberger

Published 19 Oct 2014

Servers were increasingly being used in business and academia, tended to be more expensive than individual users’ computers, and, because many users depended on them, were typically maintained by technically sophisticated personnel. And they typically ran the Unix operating system. Unix came on the scene in 1969. Invented by two Bell Labs programmers, Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie, it was the first easily portable operating system, meaning that it could be run on many different types of computers without too many modifications. As Unix was stable, powerful, and widely distributed, it quickly became the operating system of choice in academia, with two results: lots of people wrote utility programs for it, which they distributed free of charge, and virtually all graduating computer scientists knew Unix inside and out.

From Airline Reservations to Sonic the Hedgehog: A History of the Software Industry

by

Martin Campbell-Kelly

Published 15 Jan 2003

It is now available for all computer platforms. The history of Unix is well documented.29 Like the origins of the Internet (with which it is closely associated), it has entered the folklore 144 Chapter 5 of post-mainframe computing. The Unix project was initiated in 1969 by two researchers at Bell Labs, Ken Thomson and Dennis Ritchie. “Unix” was a pun on “MULTICS,” the name of a multi-access time-sharing system then being developed by a consortium of Bell Labs, General Electric, and MIT. MULTICS was a classic software disaster. It was path-breaking in concept, but to get it working with tolerable efficiency and reliability took a decade.30 In reaction to MULTICS, Unix was designed as a simple, reliable system for a single user, initially on a DEC minicomputer.

The Future of Ideas: The Fate of the Commons in a Connected World

by

Lawrence Lessig

Published 14 Jul 2001

Because of a consent decree with the government in 1956, however, it was not permitted to build and sell these computers itself. It was therefore dependent upon the computers that others built and frustrated, like the government, by the fact that these other computers couldn't talk to each other.3 Researchers at Bell Labs, however, decided to do something about this. In 1969, Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie began an operating system that could be “ported” (read: translated) to every machine. 4 This operating system would therefore be a common platform upon which programs could run. And because this platform would be common among many different machines, a program written once could—with tiny changes—be run on many different machines.

The Linux kernel primer: a top-down approach for x86 and PowerPC architectures

by

Claudia Salzberg Rodriguez

,

Gordon Fischer

and

Steven Smolski

Published 15 Nov 2005

This operating system, developed by Ken Thompson, supported two users and had a command interpreter and programs that allowed file manipulation for the new filesystem. In 1970, UNIX was ported to the PDP-11 and updated to support more users. This was technically the first edition of UNIX. In 1973, for the release of the fourth edition of UNIX, Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie rewrote UNIX in C (a language then recently developed by Ritchie). This moved the operating system away from pure assembly and opened the doors to the portability of the operating system. Take a moment to consider the pivotal nature of this decision. Until then, operating systems were entirely entrenched with the system's architecture specifications because assembly language is extremely particular and not easily ported to other architectures.

The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation

by

Jon Gertner

Published 15 Mar 2012

The memo goes on to detail the Labs’ efforts at all three and acknowledges its work on fiber was lagging behind the work at Corning, which had been described to the Bell Labs’ team through “a private communication.” 23 William O. Baker, “Testimony of William O. Baker,” May 31, 1966. F.C.C. Docket No. 16258. 24 Memo, R. Kompfner to J. K. Galt, November 30, 1970. AT&T archives. 25 Unix was created primarily by Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, Brian Kernighan, Douglas McIlroy, and Joe Ossanna. 26 Willard Boyle and George Smith were credited as inventors of the CCD device and were awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize—to be shared with Charles Kao, the early champion of fiber optics. Immediately after Boyle and Smith won the award, Eugene Gordon, another Bell Labs veteran, challenged the credit they received and claimed that some of the ideas for the device originated with him.

Your Computer Is on Fire

by

Thomas S. Mullaney

,

Benjamin Peters

,

Mar Hicks

and

Kavita Philip

Published 9 Mar 2021

It’s possible that you are running programs which are written in Delphi on your computers, and they could be affected.38 An FAQ page on the virus written by Sophos employee Nick Hodges responds to the question of whether C++ Builder, another Sophos compiler for the C++ HLL, could become a vector for the virus by saying “no,” but then hedging with a sentence starting, “It is theoretically possible for a C++ Builder EXE to become infected.”39 It is worth noting that despite the existence of W32/Induc-A, the Thompson hack is much less of a threat than it was when Thompson developed his initial version. In the 1970s, everyone using Unix depended on Thompson’s software—the compiler, the operating system itself, most debugging tools, and most of the entire software development toolchain were written at Bell Labs by Thompson and his collaborator Dennis Ritchie. Any malfeasance, even playful malfeasance, committed by Thompson could potentially be disastrous. Today, there is no one single person upon whose work all practical computing depends—we use a variety of operating systems, a variety of compilers, and a variety of software development tools, and writing a Thompson hack Trojan that can thoroughly evade detection is now much more difficult.

WTF?: What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us

by

Tim O'Reilly

Published 9 Oct 2017

You inspire me and are a testament to the fact that a corporation too is a human augmentation, enabling us to do things that we could never accomplish on our own. Over my years in the technology industry, I’d like to single out as mentors and sources of inspiration, directly or indirectly, Stewart Brand, Dennis Ritchie, Ken Thompson, Brian Kernighan, Bill Joy, Bob Scheifler, Larry Wall, Vint Cerf, Jon Postel, Tim Berners-Lee, Linus Torvalds, Brian Behlendorf, Jeff Bezos, Larry Page, Sergey Brin, Eric Schmidt, Pierre Omidyar, Ev Williams, Mark Zuckerberg, Saul Griffith, and Bill Janeway. I have drawn my map by studying the world you have helped to create.

Commodore: A Company on the Edge

by

Brian Bagnall

Published 13 Sep 2005

The Z8000 based computer would use Unix, an acclaimed operating system for minicomputers. “With the Z8000, we were trying to run a Unix like operating system and it was clearly a business machine,” says Russell. At the time, AT&T owned the most popular commercial version of Unix. Computer pioneers Dennis Ritchie and Ken Thompson developed the Unix system (originally called UNICS) in 1969, along with the C programming language. The source code for the operating system was freely available. Companies quickly began customizing and selling different flavors optimized for different machines.[1] Tramiel made a deal with a smaller company for a Unix operating system, which they called Coherent.

The C++ Programming Language

by

Bjarne Stroustrup

Published 2 Jan 1986

x Preface to the First Edition Acknowledgments C++ could never have matured without the constant use, suggestions, and constructive criticism of many friends and colleagues. In particular, Tom Cargill, Jim Coplien, Stu Feldman, Sandy Fraser, Steve Johnson, Brian Kernighan, Bart Locanthi, Doug McIlroy, Dennis Ritchie, Larry Rosler, Jerry Schwarz, and Jon Shopiro provided important ideas for development of the language. Dave Presotto wrote the current implementation of the stream I/O library. In addition, hundreds of people contributed to the development of C++ and its compiler by sending me suggestions for improvements, descriptions of problems they had encountered, and compiler errors.

UNIX® Network Programming, Volume 1: The Sockets Networking API, 3rd Edition

by

W. Richard Stevens, Bill Fenner, Andrew M. Rudoff

Published 8 Jun 2013

We will also develop a simple TCP client using the Transport Provider Interface (TPI), the interface into the transport layer that sockets normally use on a system based on STREAMS. Additional information on STREAMS, including information on writing kernel routines that utilize STREAMS, can be found in [Rago 1993]. STREAMS were designed by Dennis Ritchie [Ritchie 1984] and were first made widely available with SVR3 in 1986. The POSIX specification defines STREAMS as an option group, which means a system may not implement STREAMS, but if it does, the implementation must comply with the POSIX specification. Any system derived from System V should provide POSIX, but the various 4.xBSD releases do not provide POSIX.