Doomsday Book

by

Connie Willis

Published 1 Jan 1992

Praise for Connie Willis’s HUGO AND NEBULA AWARD WINNING DOOMSDAY BOOK: “Splendid work—brutal, gripping, and genuinely harrowing, the product of diligent research, fine writing, and well-honed instincts, that should appeal far beyond the usual science-fiction constituency.” —Kirkus Reviews (starred review) “The world of 1348 burns in the mind’s eye, and every character alive in that year is a fully realized being.… It becomes possible to feel … that Connie Willis did, in fact, over the five years DOOMSDAY BOOK took her to write, open a window to another world, and that she saw something there.”

…

—Star Tribune, Minneapolis “The clarity and consistency of Willis’s writing, as well as her deft storytelling ability, place her among this decade’s most promising writers.… [Doomsday Book] rates special attention.” —Library Journal “An intelligent and satisfying blend of classic science fiction and historical reconstruction.” —Publishers Weekly “An ambitious, finely detailed, and compulsively readable novel.” —Locus Bantam Books by Connie Willis DOOMSDAY BOOK FIRE WATCH LINCOLN’S DREAMS IMPOSSIBLE THINGS BELLWETHER REMAKE UNCHARTED TERRITORY TO SAY NOTHING OF THE DOG MIRACLE AND OTHER CHRISTMAS STORIES PASSAGE BLACKOUT This edition contains the complete text of the original hardcover edition.

…

—Locus Bantam Books by Connie Willis DOOMSDAY BOOK FIRE WATCH LINCOLN’S DREAMS IMPOSSIBLE THINGS BELLWETHER REMAKE UNCHARTED TERRITORY TO SAY NOTHING OF THE DOG MIRACLE AND OTHER CHRISTMAS STORIES PASSAGE BLACKOUT This edition contains the complete text of the original hardcover edition. NOT ONE WORD HAS BEEN OMITTED. DOOMSDAY BOOK A Bantam Spectra Book/July 1992 PUBLISHING HISTORY Bantam paperback edition / September 1993 Bantam reissue edition/July 1994 SPECTRA and the portrayal of a boxed “s” are trademarks of Bantam Books, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1992 by Connie Willis. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Firefighting

by

Ben S. Bernanke

,

Timothy F. Geithner

and

Henry M. Paulson, Jr.

Published 16 Apr 2019

WEAKER EMERGENCY ARSENAL The story of how the crisis happened is a complex story about risky leverage, runnable funding, shadow banking, rampant securitization, and outdated regulation. But the story of how the crisis got so terrible is a comparatively simple story about the weak and antiquated arsenal of emergency weapons we had to fight it. When Tim started at the New York Fed in 2003, he read its “Doomsday Book” outlining its break-the-glass emergency powers, and he wasn’t impressed. Ben had a similar experience when he became Fed chairman in 2006 and asked for a briefing on crisis-fighting tools. The Fed had broad powers to lend to banks against solid collateral, but it could only lend to nonbanks in a crisis if it invoked its 13(3) emergency powers, and even then only if the potential borrowers were near or past the point of no return.

…

and expansion of crisis, 46 and expansion of emergency authorities, 79 and Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac conservatorship, 58, 59 and onset of financial crisis, 1 and politics of crisis management, 9 and TARP, 80, 93–94, 95, 105 capitalism, 36–37, 74, 110 capital levels capitalization strategies, 164 and current state of financial system, 6 and Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac conservatorship, 56, 59 and onset of financial crisis, 30 and policy responses to crisis, 174–82 and politics of crisis management, 126 and post-crisis reforms, 117 and shortcomings of U.S. regulatory regime, 25–26, 27 and TARP, 89–90 Capital Purchase Program (CPP), 163, 176, 177, 208 “CDOs-Squared,” 19 central banks and arsenal for dealing with future crises, 119–20, 123 and Bear Stearns rescue, 48–49 and coordinated interest rate cuts, 197 and Fed liquidity programs, 217n and Lehman failure, 69 and policy responses to crisis, 33, 103–4, 162, 163 and politics of crisis management, 126 and post-crisis reforms, 118 and quantitative easing, 104 and swap lines, 42–43, 196, 217n and TARP, 89 and theoretical approaches to financial crises, 34–36, 38 CEOs and executives of financial institutions, 40–41, 52, 73–74, 82, 91, 101 Chrysler, 95, 97, 105, 208 Citigroup and acceleration of crisis, 21 and federal asset guarantees, 178 government investment in, 176, 177 and Lehman failure, 69 management firings, 73 and policy responses to crisis, 97 private capital raised during crisis, 175, 181 and stress tests, 180 structured investment vehicles, 41 and TARP, 94–95, 96, 101 and taxpayer profit from rescue, 208 and Wachovia crisis, 81, 82 write-down of troubled assets, 40–41 collateral and acceleration of crisis, 20–22, 24 and AIG rescue, 72, 73 and arsenal for dealing with future crises, 118–19 and Bear Stearns rescue, 47, 52 collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), 19, 41 collateralized funding, 24 and Countrywide sale, 42 and Lehman failure, 62, 63, 68, 69 and TARP, 94 and Term Securities Lending Facility, 45 and triage process, 40 commercial banks, 5, 126–27, 173 Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF), 88, 163, 168, 208 commercial paper market, 88 Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), 23, 116 complacency, 26, 146 Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 116 consumer lending and debt, 94, 116, 120–21, 149, 169 Continuing Extension Act, 187 corporate bonds, 75 corporate financing, 22 Council of Economic Advisers, 28 Countrywide Financial and AIG rescue, 71 and Bear Stearns rescue, 48, 52 crisis and sale of, 38–40 and expansion of crisis, 46–47 management firings, 73 and onset of financial crisis, 31, 155 and oversight of nonbanks, 23 and post-crisis reforms, 115, 116 and spark of crisis, 18 creative destruction, 36–37 credit booms, 3–4, 12, 13, 16, 117, 150 credit crunch, 36, 108 credit default swaps (CDS) and AIG rescue, 72 and effect of stabilization efforts, 201 and expansion of crisis, 75 and Lehman failure, 69 and phases of financial crisis, 153 and policy responses to crisis, 173 currency exchanges, 42–43, 196 Darling, Alistair, 67–68 debt bank debt, 90 and causes of financial crisis, 3 collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), 19, 41 federal debt levels, 124 household debt levels, 16, 149 Latin American debt crisis, 37 and post-crisis reforms, 112 “runnable” forms of debt, 12, 112 and spark of crisis, 16, 19 and TARP, 87 Debt Guarantee Program, 217n defaults, 22 Defense Appropriations Act, 187 deficit spending, 104, 124–25, 128 Democratic Party, 5, 80, 83, 104–5, 129 deposit insurance, 14–15, 22–23, 34, 162, 163, 172 Deposit Insurance Fund, 81, 88 derivatives and acceleration of crisis, 24 and AIG rescue, 71–72 and Bear Stearns rescue, 48, 53 and Lehman failure, 63 and post-crisis reforms, 112, 114, 116–17 and roots of financial crisis, 13 and shortcomings of U.S. regulatory regime, 26, 28–29 and spark of crisis, 20 Diamond, Bob, 67 Dimon, Jamie, 50 discount window lending and acceleration of crisis, 22 and Countrywide sale, 39 failure to ease crisis, 42 and Fed liquidity programs, 217n and policy responses to crisis, 162, 166, 167 stigma associated with Fed borrowing, 40 and theoretical approaches to financial crises, 34, 35 dividends, 41 Dodd, Christopher, 56, 79–80 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, 113–16, 120–21, 127, 172 “Doomsday Book,” 118 dot-com bubble, 21 Dugan, John, 91 E. coli effect, 31, 42 economic output, 207 Economic Stimulus Act, 185 electronic banking, 15 Emergency Economic Stabilization Act, 172 emergency powers arsenal for dealing with future crises, 118–25, 211 and Bear Stearns rescue, 49–51 and Countrywide sale, 39 expansion of emergency authorities, 78–83 and onset of financial crisis, 44–45 and TARP, 94 employment levels, 4, 92, 95, 108, 110, 141, 202 Enhanced Leverage Fund, 31 entitlement programs, 124 European banking, 91, 182 European Central Bank (ECB), 35, 42, 89, 196, 197 European recovery, 206 European sovereign debt crisis, 123 Exchange Stabilization Fund, 76–77 executive compensation, 80, 82 FAA Air Transportation Act, 187 failure of financial firms, 8, 36–37.

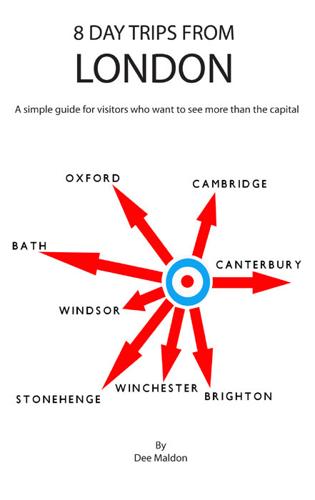

8 Day Trips From London

by

Dee Maldon

Published 16 Mar 2010

Tourist office Bath Tourist Information Centre Abbey Churchyard Bath BA1 1LY E-mail: tourism@bathtourism.co.uk http://visitbath.co.uk/Brighton Brighton Distance from London: 47 miles or 76 kilometres. Brief History Brighton began as a small fishing village in the 7th century. It was mentioned in the 11th century Doomsday Book as having the name of Brighthelmstone. In the 18th century, a prominent physician recommended the health benefits of breathing in Brighton’s fresh air and swimming in its bracing sea. As a result, the popularity of the fishing village grew, and visitors flocked to take their dip in the sea. As hotels were developed and restaurants and entertainment venues were added, the village grew to become a small town.

The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity's Search for Meaning

by

Jeremy Lent

Published 22 May 2017

See http://www.clubofrome.org/membership/ (accessed June 24, 2016). Debora MacKenzie, “Doomsday Book,” New Scientist, no. 2846 (2012): 38–41; Graham M. Turner, “A Comparison of The Limits to Growth with 30 Years of Reality,” Global Environmental Change 18 (2008): 397–411; Donella Meadows, Jorgen Randers, and Dennis Meadows, Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 2004), Kindle edition, locations 408–13. 3. MacKenzie, “Doomsday Book”; Turner, “Comparison”; Meadows, Randers, and Meadows, 30-Year Update, locs. 3021–31. 4. MacKenzie, “Doomsday Book”; Turner, “Comparison”; Meadows, Randers, and Meadows, 30-Year Update, locs. 3492–3503. 5.

State of Emergency: The Way We Were

by

Dominic Sandbrook

Published 29 Sep 2010

And never had the name seemed more fitting than in the early 1970s, the years when green was good and small was beautiful.7 In 1971, the Yorkshire Post gave its annual award for non-fiction to a title that must have struck fear into the souls of all who read it. Written by the science journalist Gordon Rattray Taylor, The Doomsday Book begins ominously with a long quotation from the Book of Revelation. On the very next page, Taylor warns his readers that mankind is facing an ‘eventual population crash’, an ‘apocalypse’ that will probably wipe out a third of humanity. Thanks to ‘crowding, pollution and a disturbed balance of nature’, the planet itself is at risk.

…

Even the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition eagerly jumped aboard the bandwagon, with displays showing the homeowners of 1975 how they could make wall lights from empty tin cans, rugs from old cardigans, a lamp from cigarette packets, a chair from drainpipes and a table from corrugated iron sheeting, which was surely carrying recycling to post-apocalyptic extremes. For some people, however, growing one’s own vegetables and saving on electricity were not enough: as Gordon Rattray Taylor had shown in The Doomsday Book, the situation was so desperate that only collective action could stave off disaster. One such group were the members of the Conservation Society, which had been founded in 1966 (by James Lees-Milne, among others) after a series of letters to the Observer about the dangers of massive population growth.

…

Jonathan Raban, Soft City (London, 1975), pp. 60, 88, 175, 190; Roy Greenslade, Press Gang: How Newspapers Make Profits from Propaganda (London, 2004),p. 337; Lawrence James, The Middle Class: A History (London 2006), pp. 575–7. 7. Margaret Drabble, The Middle Ground (Harmondsworth, 1980), p. 207; Michael Frayn, ‘Festival’, in Michael Sissons and Philip French (eds.), Age of Austerity (Oxford, 1963), pp. 307–8. 8. Gordon Rattray Taylor, The Doomsday Book: Can the World Survive? (London, 1970), pp. 13–14, 17, 52–3, 59–61, 229, 275. 9. Philip Lowe and Jane Goyder, Environmental Groups in Politics (London, 1983), pp. 16–17; Edward M. Nicholson, The Environmental Revolution (Harmondsworth, 1972), pp. 158–60; S. K. Brooks et al., ‘The Growth of the Environment as a Political Issue in Britain’, British Journal of Political Science, 6 (April 1976), pp. 245–55; Meredith Veldman, Fantasy, the Bomb and the Greening of Britain: Romantic Protest, 1945–1980 (Cambridge, 1994), pp. 208–10. 10.

The Road to Roswell: A Novel

by

Connie Willis

Published 26 Jun 2023

Inside Job Passage To Say Nothing of the Dog Bellwether Uncharted Territory Remake Impossible Things Doomsday Book Lincoln’s Dreams Fire Watch ABOUT THE AUTHOR Connie Willis is a member of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame and a Grand Master of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. She has received seven Nebula awards and eleven Hugo awards for her fiction; Blackout and All Clear—a novel in two parts—and Doomsday Book won both. Her other works include Crosstalk, Passage, To Say Nothing of the Dog, Lincoln’s Dreams, Bellwether, Impossible Things, Terra Incognita, The Best of Connie Willis, and A Lot Like Christmas.

This Is How You Lose Her

by

Junot Diaz

Published 10 Sep 2012

Some nights you have Neuromancer dreams where you see the ex and the boy and another figure, familiar, waving at you in the distance. Somewhere, very close, the laugh that wasn’t laughter. And finally, when you feel like you can do so without blowing into burning atoms, you open a folder you have kept hidden under your bed. The Doomsday Book. Copies of all the e-mails and fotos from the cheating days, the ones the ex found and compiled and mailed to you a month after she ended it. Dear Yunior, for your next book. Probably the last time she wrote your name. You read the whole thing cover to cover (yes, she put covers on it). You are surprised at what a fucking chickenshit coward you are.

Let My People Go Surfing

by

Yvon Chouinard

Published 20 Jun 2006

My wife, Malinda, and I and the other contrarian employees of Patagonia have taken lessons learned from these sports and our alternative lifestyle and applied them to running a company. My company, Patagonia, Inc., is an experiment. It exists to put into action those recommendations that all the doomsday books on the health of our home planet say we must do immediately to avoid the certain destruction of nature and collapse of our civilization. Despite near-universal consensus among scientists that we are on the brink of an environmental collapse, our society lacks the will to take action. We’re collectively paralyzed by apathy, inertia, or lack of imagination.

Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crises

by

Timothy F. Geithner

Published 11 May 2014

In those early months, I often joked that being president of the New York Fed was like being the Wizard of Oz; my friend and former Treasury colleague Sheryl Sandberg, who had become a vice president at Google, used to call me the man behind the curtain. There was a widespread perception that we had awesome powers to fight financial fires, but when I studied our actual firefighting equipment—cataloged in a New York Fed binder known internally as “the Doomsday Book”—I was not particularly impressed. In addition to its monetary policy instruments, the Fed could lend to institutions that needed cash in a crisis—but only if they were commercial banks with insured deposits, and only if we thought they were fundamentally solvent, with their assets worth more than their liabilities.

…

There were too many other firms that looked like Bear in terms of their leverage, their dependence on short-term funding, and their exposure to devastating losses as the housing market dropped and recession fears mounted. But there was one piece of better news. Tom Baxter, our general counsel, taking a page from the Doomsday Book, the binder full of information about the New York Fed’s emergency powers that he had helped write years earlier, proposed an idea that could keep Bear alive through the weekend, a “back-to-back” loan involving JPMorgan. Rather than lending directly to Bear, Tom said, we could make a short-term loan to JPMorgan that it would “on-lend” to Bear, while pledging some of Bear’s securities as collateral.

Time Travel: A History

by

James Gleick

Published 26 Sep 2016

Tom Stoppard, Arcadia, 1993. William Tenn, “Brooklyn Project,” 1948. Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens), A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, 1889. Jules Verne, Paris au XXe siècle, 1863. Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five, 1969. H. G. Wells, The Time Machine, 1895. The Sleeper Awakes, 1910. Connie Willis, Doomsday Book, 1992. Virginia Woolf, Orlando, 1928. Charles Yu, How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, 2010. Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale, Back to the Future, 1985. ANTHOLOGIES Mike Ashley, The Mammoth Book of Time Travel SF, 2013. Peter Haining, Timescapes, 1997. Robert Silverberg, Voyagers in Time, 1967.

Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet

by

Claire L. Evans

Published 6 Mar 2018

The result was an unusual book, now invaluable to historians, detailing the minutiae of the Saxon world, the only survey of its kind. Because the judgments made by the Norman assessors who compiled it were supposed to be definitive, native English people called it the Domesday Book, Middle English for “Doomsday Book.” As the British cleric Richard FitzNeal wrote nearly a century later, decisions made in the Domesday Book, “like those of the Last Judgement, are unalterable.” The Domesday Book is what led Wendy Hall, in a circuitous way, to her career creating hypertext systems long before the dawn of the Web.

Realizing Tomorrow: The Path to Private Spaceflight

by

Chris Dubbs

,

Emeline Paat-dahlstrom

and

Charles D. Walker

Published 1 Jun 2011

Then it catalyzed the brew with an activism that ignited a populist movement. O'Neill's call for the colonization of space represented more than just another space program option. He wanted an optimistic future for mankind, he would often say. The suggestion, of course, was that mankind's future was not so optimistic, a theory trumpeted by a spate of popular doomsday books published in the late L96os and early 1970s. Titles such as The Population Bomb (1968), The Late Great Planet Earth (1970), and The Limits to Growth (1972) prophesied overpopulation, uncontrolled pollution, resource depletion, and economic collapse. Their philosophy, known collectively as limits to growth (LTG), offered a bleak view of human future.

Ayn Rand Cult

by

Jeff Walker

Published 30 Dec 1998

Impact on Investors Neo-objectivist Walter Donway, editor of the newsletter of the Institute for Objectivist Studies, confided to an interviewer that in 1963, too afraid to ask Rand a question directly at a Ford Hall lecture, he got a friend to ask: “If government intervention in the money supply sets up the economy for a bust and a depression, . . . aren’t we going to have one?” Rand replied that she “didn’t see how we could go another five years without a major depression. That created a new industry, as you know. . . . I don’t know if economic doomsday books were published before that time, but later it became a whole new genre.” Donway was referring to books like Douglas Casey’s Crisis Investing, Robert Ringer’s How to Find Happiness during the Collapse of Western Civilization, and dozens of similar best-sellers. “I will tell you that years of folly in investing, by me and a lot of other students of Objectivism, began there.”

Breaking News: The Remaking of Journalism and Why It Matters Now

by

Alan Rusbridger

Published 14 Oct 2018

The most sinister thing from the point of view of the average desk editor sitting in Farringdon Road or Wapping or Canary Wharf was the little line at the bottom of the site: The selection and placement of stories on this page were determined automatically by a computer program. That’s right: it was produced entirely by machines. Not one human being was involved in the generation of this modern, news version of the Doomsday Book. It was all produced by a cyber spider which whisked its way around the world filtering news sites and linking to them. Quite how it was done was a mystery as closely guarded as the recipe for Marmite or Coca-Cola. I discussed it with a colleague working on the Washington Post website. He shrugged: ‘None of us can predict anything more than six months out.

How to Make a Spaceship: A Band of Renegades, an Epic Race, and the Birth of Private Spaceflight

by

Julian Guthrie

Published 19 Sep 2016

The photo, called “the picture that changed the world,” showed a perfect blue and white marble surrounded by a black sea. The astronauts read from the book of Genesis, and Lovell said of the image, “The vast loneliness is awe-inspiring and it makes you realize just what you have back there on Earth.” The image would play a role in doomsday books by the likes of Paul Ehrlich and bleak scenarios by the Limits to Growth researchers. It inspired the modern environmental movement. What Byron said resonated with Erik. He understood that on one critical level, the XPRIZE was about giving more people that view of Earth. He could see how the goals of the XPRIZE were aligned with the Lindbergh Foundation’s mission of using technology to enhance life and preserve the environment.

The Best of Best New SF

by

Gardner R. Dozois

Published 1 Jan 2005

In 1982, she won two Nebula Awards, one for her novelette “Fire Watch,” and one for her short story “A Letter from the Clearys”; a few months later, “Fire Watch” went on to win her a Hugo Award as well. In 1989, her novella “The Last of the Winnebagoes” won both the Nebula and the Hugo, and she won another Nebula in 1990 for her novelette “At The Rialto.” In 1993, her landmark novel Doomsday Book won both the Nebula Award and the Hugo Award, as did her short story “Even the Queen.” She won another Hugo in 1994 for her story “Death on the Nile,” another in 1997 for her story “The Soul Selects Her Own Society,” another in 1999 for her novel To Say Nothing of the Dog, and yet another in 2000 for her novella “The Winds of Marble Arch” – all of which makes her one of the most honoured writers in the history of science fiction, and, as far as I know, the only person ever to win two Nebulas and two Hugos in the same year.