Douglas Hofstadter

description: an American professor known for his work on consciousness, artificial intelligence, and the book 'Gödel, Escher, Bach'

87 results

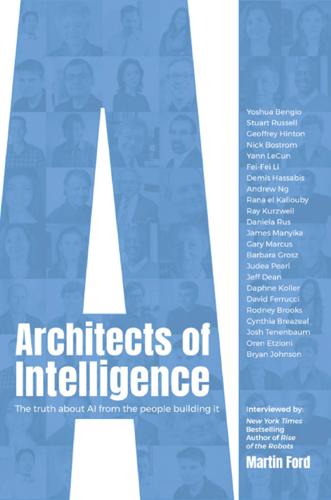

Artificial Intelligence: A Guide for Thinking Humans

by

Melanie Mitchell

Published 14 Oct 2019

Kansky et al., “Schema Networks: Zero-Shot Transfer with a Generative Causal Model of Intuitive Physics,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (2017), 1809–18. 11. A. A. Rusu et al., “Progressive Neural Networks,” arXiv:1606.04671 (2016). 12. Marcus, “Deep Learning.” 13. Quoted in N. Sonnad and D. Gershgorn, “Q&A: Douglas Hofstadter on Why AI Is Far from Intelligent,” Quartz, Oct. 10, 2017, qz.com/1088714/qa-douglas-hofstadter-on-why-ai-is-far-from-intelligent. 14. I should note that a few robotics groups have actually developed dishwasher-loading robots, though none of these was trained by reinforcement learning, or any other kind of machine-learning method, as far as I know.

…

I had been working on various aspects of AI since graduate school in the 1980s and had been tremendously impressed by what Google had accomplished. I also thought I had some good ideas to contribute. But I have to admit that I was there only as a tagalong. The meeting was happening so that a group of select Google AI researchers could hear from and converse with Douglas Hofstadter, a legend in AI and the author of a famous book cryptically titled Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid, or more succinctly, GEB (pronounced “gee-ee-bee”). If you’re a computer scientist, or a computer enthusiast, it’s likely you’ve heard of it, or read it, or tried to read it. Written in the 1970s, GEB was an outpouring of Hofstadter’s many intellectual passions—mathematics, art, music, language, humor, and wordplay, all brought together to address the deep questions of how intelligence, consciousness, and the sense of self-awareness that each human experiences so fundamentally can emerge from the non-intelligent, nonconscious substrate of biological cells.

…

In the early 1980s, after graduating from college with a math degree, I was living in New York City, teaching math in a prep school, unhappy, and casting about for what I really wanted to do in life. I discovered GEB after reading a rave review in Scientific American. I went out and bought the book immediately. Over the next several weeks, I devoured it, becoming increasingly convinced that not only did I want to become an AI researcher but I specifically wanted to work with Douglas Hofstadter. I had never before felt so strongly about a book, or a career choice. At the time, Hofstadter was a professor in computer science at Indiana University, and my quixotic plan was to apply to the computer science PhD program there, arrive, and then persuade Hofstadter to accept me as a student.

The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry

by

Jon Ronson

Published 12 May 2011

“So if Levi Shand doesn’t exist,” I said, “who created him?” “I think they’re all Hofstadter,” said Deborah. “Levi Shand. Petter Nordlund. I think they’re all Douglas Hofstadter.” I went for a walk through Gothenburg, feeling quite annoyed and disappointed that I’d been hanging around here for days when the culprit was probably an eminent professor some four thousand miles away at Indiana University. Deborah had offered me supplementary circumstantial evidence to back her theory that the whole puzzle was a product of Douglas Hofstadter’s impish mind. It was, she said, exactly the sort of playful thing he might do. And being the author of an international bestseller, he would have the financial resources to pull it off.

…

It was a compelling theory, and I continued to believe this might be the solution to the riddle right up until the moment, an hour later, I had a Skype video conversation with Levi Shand, who, it was soon revealed, wasn’t an invention of Douglas Hofstadter’s but an actual student from Indiana University. He was a handsome young man with black hair, doleful eyes, and a messy student bedroom. He had been easy to track down. I e-mailed him via his Facebook page. He got back to me straightaway (he’d been online at the time) and within seconds we were face-to-face. He told me it was all true. He really did find the books in a box under a railway viaduct and Douglas Hofstadter really did have a harem of French women living at his home. “Tell me exactly what happened when you visited him,” I said.

…

A note at the beginning claimed that the manuscript had been “found” in the corner of an abandoned railway station: “It was lying in the open, visible to all, but I was the only one curious enough to pick it up.” What followed were elliptical quotations:My thinking is muscular. Albert Einstein I am a strange loop. Douglas Hofstadter Life is meant to be a joyous adventure. Joe K The book had only twenty-one pages with text, but some pages contained just one sentence. Page 18, for instance, read simply: “The sixth day after I stopped writing the book I sat at B’s place and wrote the book.” And all of this was very expensively produced, using the highest-quality paper and inks—there was a full-color, delicate reproduction of a butterfly on one page—and the endeavor must have cost someone or a group of people an awful lot of money.

Complexity: A Guided Tour

by

Melanie Mitchell

Published 31 Mar 2009

Complexity: a guided tour/Melanie Mitchell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-512441-5 1. Complexity (Philosophy) I. Title. Q175.32.C65M58 2009 501—dc22 2008023794 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper To Douglas Hofstadter and John Holland CONTENTS Preface Acknowledgments PART ONE Background and History CHAPTER ONE What Is Complexity? CHAPTER TWO Dynamics, Chaos, and Prediction CHAPTER THREE Information CHAPTER FOUR Computation CHAPTER FIVE Evolution CHAPTER SIX Genetics, Simplified CHAPTER SEVEN Defining and Measuring Complexity PART TWO Life and Evolution in Computers CHAPTER EIGHT Self-Reproducing Computer Programs CHAPTER NINE Genetic Algorithms PART THREE Computation Writ Large CHAPTER TEN Cellular Automata, Life, and the Universe CHAPTER ELEVEN Computing with Particles CHAPTER TWELVE Information Processing in Living Systems CHAPTER THIRTEEN How to Make Analogies (if You Are a Computer) CHAPTER FOURTEEN Prospects of Computer Modeling PART FOUR Network Thinking CHAPTER FIFTEEN The Science of Networks CHAPTER SIXTEEN Applying Network Science to Real-World Networks CHAPTER SEVENTEEN The Mystery of Scaling CHAPTER EIGHTEEN Evolution, Complexified PART FIVE Conclusion CHAPTER NINETEEN The Past and Future of the Sciences of Complexity Notes Bibliography Index PREFACE REDUCTIONISM is the most natural thing in the world to grasp.

…

CHAPTER TWO Dynamics, Chaos, and Prediction CHAPTER THREE Information CHAPTER FOUR Computation CHAPTER FIVE Evolution CHAPTER SIX Genetics, Simplified CHAPTER SEVEN Defining and Measuring Complexity PART TWO Life and Evolution in Computers CHAPTER EIGHT Self-Reproducing Computer Programs CHAPTER NINE Genetic Algorithms PART THREE Computation Writ Large CHAPTER TEN Cellular Automata, Life, and the Universe CHAPTER ELEVEN Computing with Particles CHAPTER TWELVE Information Processing in Living Systems CHAPTER THIRTEEN How to Make Analogies (if You Are a Computer) CHAPTER FOURTEEN Prospects of Computer Modeling PART FOUR Network Thinking CHAPTER FIFTEEN The Science of Networks CHAPTER SIXTEEN Applying Network Science to Real-World Networks CHAPTER SEVENTEEN The Mystery of Scaling CHAPTER EIGHTEEN Evolution, Complexified PART FIVE Conclusion CHAPTER NINETEEN The Past and Future of the Sciences of Complexity Notes Bibliography Index PREFACE REDUCTIONISM is the most natural thing in the world to grasp. It’s simply the belief that “a whole can be understood completely if you understand its parts, and the nature of their ‘sum.’ ” No one in her left brain could reject reductionism. —Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid REDUCTIONISM HAS BEEN THE DOMINANT approach to science since the 1600s. René Descartes, one of reductionism’s earliest proponents, described his own scientific method thus: “to divide all the difficulties under examination into as many parts as possible, and as many as were required to solve them in the best way” and “to conduct my thoughts in a given order, beginning with the simplest and most easily understood objects, and gradually ascending, as it were step by step, to the knowledge of the most complex.”1 Since the time of Descartes, Newton, and other founders of the modern scientific method until the beginning of the twentieth century, a chief goal of science has been a reductionist explanation of all phenomena in terms of fundamental physics.

…

Influenced by the early pioneers of computation, I felt that computation as an idea goes much deeper than operating systems, programming languages, databases, and the like; the deep ideas of computation are intimately related to the deep ideas of life and intelligence. At Michigan I was lucky enough to be in a department in which “computation in natural systems” was as much a part of the core curriculum as software engineering or compiler design. In 1989, at the beginning of my last year of graduate school, my Ph.D. advisor, Douglas Hofstadter, was invited to a conference in Los Alamos, New Mexico, on the subject of “emergent computation.” He was too busy to attend, so he sent me instead. I was both thrilled and terrified to present work at such a high-profile meeting. It was at that meeting that I first encountered a large group of people obsessed with the same ideas that I had been pondering.

Is That a Fish in Your Ear?: Translation and the Meaning of Everything

by

David Bellos

Published 10 Oct 2011

Finding out what translation has done in the past and does today, finding out what people have said about it and why, finding out whether it is one thing or many—these inquiries take us far and wide, to Sumer, Brussels, and Beijing, to comic books and literary classics, and into the fringes of disciplines as varied as anthropology, linguistics, and computer science. What translation does raises so many answerable questions that we can leave the business of what it is to the side for quite some time. ONE What Is a Translation? Douglas Hofstadter took a great liking to this short poem by the sixteenth-century French wit Clément Marot: Ma mignonne, Je vous donne Le bon jour; Le séjour C’est prison. Guérison Recouvrez, Puis ouvrez Votre porte Et qu’on sorte Vitement, Car Clément Le vous mande. Va, friande De ta bouche, Qui se couche En danger Pour manger Confitures; Si tu dures Trop malade, Couleur fade Tu prendras, Et perdras L’embonpoint.

…

In a world where you can check the translation against the original, even when it has the form of speech (thanks to the sound-recording devices we have used for the past one hundred years), the principal grounds for the fear and mistrust of linguistic intermediaries that is endemic to oral societies no longer exist. Yet people go on saying traduttore/traditore, believing they have said something meaningful about translation. A thoughtful translator such as Douglas Hofstadter still feels he needs to counter it with a pun in the title of an essay, “Trader/Translator.” 15 We may now live in a sophisticated, wealthy, technologically advanced society—but when it comes to translation, some people seem to be stuck in the age of the clepsydra. Traditional mistrust of oral interpreters in the Middle East affected Western tourists when visits to the region became practical and prestigious for individuals in the nineteenth century.

…

Few poets write sublime verse every time. But it stands to reason that the quality of a poem in translation has no relation to its having been translated. It is the sole fruit of the poet’s skill as a poet, irrespective of whether he is also writing as a translator. You may not like the poem by Douglas Hofstadter quoted at the start of this book. You may like the poem by Clément Marot much more. But all that you could reasonably say about the difference is that Hofstadter is (in this instance) a less charming writer of poetry than Marot. If you didn’t know that Hofstadter’s trisyllabic verse transposes sentiments first expressed by someone else in a form that has a quite strict relationship to it, you might still not like it—but you wouldn’t think of justifying your disappointment by saying that poetry is what has been lost in translation.

The Most Human Human: What Talking With Computers Teaches Us About What It Means to Be Alive

by

Brian Christian

Published 1 Mar 2011

For instance, are artists more valuable to us than they were before we discovered how difficult art is for computers? Last, we might ask ourselves: Is it appropriate to allow our definition of our own uniqueness to be, in some sense, reactionary to the advancing front of technology? And why is it that we are so compelled to feel unique in the first place? “Sometimes it seems,” says Douglas Hofstadter, “as though each new step towards AI, rather than producing something which everyone agrees is real intelligence, merely reveals what real intelligence is not.” While at first this seems a consoling position—one that keeps our unique claim to thought intact—it does bear the uncomfortable appearance of a gradual retreat, the mental image being that of a medieval army withdrawing from the castle to the keep.

…

All the Beauty of Art At one point in his career, the famous twentieth-century French artist Marcel Duchamp gave up art, in favor of something he felt was even more expressive, more powerful: something that “has all the beauty of art—and much more.” It was chess. “I have come to the personal conclusion,” Duchamp wrote, “that while all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists.” The scientific community, by and large, seemed to agree with that sentiment. Douglas Hofstadter’s 1980 Pulitzer Prize–winning Gödel, Escher, Bach, written at a time when computer chess was over twenty-five years old, advocates “the conclusion that profoundly insightful chess-playing draws intrinsically on central facets of the human condition.” “All of these elusive abilities … lie so close to the core of human nature itself,” Hofstadter says, that computers’ “mere brute-force … [will] not be able to circumvent or shortcut that fact.”

…

Most people were divided between two conclusions: (1) accept that the human race was done for, that intelligent machines had finally come to be and had ended our supremacy over all creation (which, as you can imagine, essentially no one was prepared to do), or (2) what most of the scientific community chose, which was essentially to throw chess, the game Goethe called “a touchstone of the intellect,” under the bus. The New York Times interviewed the nation’s most prominent thinkers on AI immediately after the match, and our familiar Douglas Hofstadter, seeming very much the tickled corpse, says, “My God, I used to think chess required thought. Now, I realize it doesn’t.” Other academics seemed eager to kick chess when it was down. “From a purely mathematical point of view, chess is a trivial game,” says philosopher and UC Berkeley professor John Searle.

A World Without Work: Technology, Automation, and How We Should Respond

by

Daniel Susskind

Published 14 Jan 2020

,” Wall Street Journal, 23 February 2011. 10. Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (London: Penguin, 2000), p. 601: “There is a related ‘Theorem’ about progress in AI: once some mental function is programmed, people soon cease to consider it as an essential ingredient of ‘real thinking.’ The ineluctable core of intelligence is always in that next thing which hasn’t yet been programmed. This ‘Theorem’ was first proposed to me by Larry Tesler, so I call it Tesler’s Theorem: ‘AI is whatever hasn’t been done yet.’” 11. Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach, p. 678. 12. Douglas Hofstadter, “Staring Emmy Straight in the Eye—And Doing My Best Not to Flinch” in David Cope, ed., Virtual Music: Computer Synthesis of Musical Style (London: MIT Press, 2004), p. 34. 13.

…

From a practical point of view, it may have been an appealing idea for AI researchers. If human beings were only complicated computers, the difficulty of building an artificial intelligence was not insurmountable: the researchers merely had to make their own, simple computers more sophisticated.20 As the computer scientist Douglas Hofstadter puts it in his celebrated Gödel, Escher, Bach, it was an “article of faith” for many researchers that “all intelligences are just variations on a single theme; to create true intelligence, AI workers will have to keep pushing … closer and closer to brain mechanisms, if they wish their machines to attain the capabilities which we have.”21 Of course, not everyone was interested in copying human beings.

…

AI researchers, economists, and many others would be caught out, time and time again, by the capabilities of new machines that were no longer built to copy some supposedly indispensable feature of human intelligence. A SENSE OF DISAPPOINTMENT For an influential group of critics in the AI community, the pragmatist revolution is more a source of disappointment than a cause for celebration. Take their response to the chess triumph of IBM’s Deep Blue over Garry Kasparov. Douglas Hofstadter, the computer scientist and writer, called its first victory “a watershed event” but dismissed it as something that “doesn’t have to do with computers becoming intelligent.”4 He had “little intellectual interest” in IBM’s machine because “the way brute-force chess programs work doesn’t bear the slightest resemblance to genuine human thinking.”5 John Searle, the philosopher, dismissed Deep Blue as “giving up on A.I.”6 Kasparov himself effectively agreed, writing off the machine as a “$10 million alarm clock.7 Or take Watson, another IBM computer system.

I Am a Strange Loop

by

Douglas R. Hofstadter

Published 21 Feb 2011

In other words, although he doesn’t propose anything that would smack of mathematics, Parfit essentially proposes an abstract “distance function” (what mathematicians would call a “metric”) between personalities in “personality space” (or between brains, although at what structural level brains would have to be described in order for this “distance calculation” to take place is never specified, and it is hard to imagine what that level might be). Using such a mind-to-mind metric, I would be very “close” to the person I was yesterday, slightly less close to the person I was two days ago, and so forth. In other words, although there is a great degree of overlap between the individuals Douglas Hofstadter today and Douglas Hofstadter yesterday, they are not identical. We nonetheless standardly (and reflexively) choose to consider them identical because it is so convenient, so natural, and so easy. It makes life much simpler. This convention allows us to give things (both animate and inanimate) fixed names and to talk about them from one day to the next without constantly having to update our lexicon.

…

But knee-jerk reflex or not, the truth of the matter is that there is no thing called “I” — no hard marble, no precious yolk protected by a Cartesian eggshell — there are just tendencies and inclinations and habits, including verbal ones. In the end, we have to believe both Douglas Hofstadters as they say, “This one here is me,” at least to the extent that we believe the Douglas Hofstadter who is right now sitting in his study typing these words and saying to you in print, “This one here is me.” Saying this and insisting on its truth is just a tendency, an inclination, a habit — in fact, a knee-jerk reflex — and it is no more than that, even though it seems to be a great deal more than that.

…

And indeed, it is impossible to come away from this book without having introduced elements of his point of view into our own. It may not make us kinder or more compassionate, but we will never look at the world, inside or out, in the same way again.” — Los Angeles Times Book Review “Nearly thirty years after his best-selling book Gödel, Escher, Bach, cognitive scientist and polymath Douglas Hofstadter has returned to his extraordinary theory of self.” — New Scientist “I Am a Strange Loop is thoughtful, amusing and infectiously enthusiastic.” — Bloomberg News “[P]rovocative and heroically humane . . . it’s impossible not to experience this book as a tender, remarkably personal and poignant effort to understand the death of his wife from cancer in 1993 — and to grasp how consciousness mediates our otherwise ineffable relationships.

From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds

by

Daniel C. Dennett

Published 7 Feb 2017

Evolving robots on the macroscale have also achieved some impressive results in very simplified domains, and I have often spoken about the work in evolutionary robotics by Inman Harvey and Phil Husbands at Sussex (e.g., Harvey et al. 1997), but I have not discussed it in print. 383David Cope. Cope’s Virtual Music (2001) includes essays by Douglas Hofstadter, composers, musicologists, and me: “Collision Detection, Muselot, and Scribble: Some Reflections on Creativity.” The essays are filled with arresting observations and examples, and the volume includes many musical scores and comes with a CD. 384substrate-neutral. See DDI (1995) on substrate neutrality. 385analogizers. See also Douglas Hofstadter’s many works on the importance of analogy finding, especially Metamagical Themas (1985), Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies (1995), and Surfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking, coauthored with Emmanuel Sander (first published in French as L’Analogie.

…

This love of mystery is just one of the potent imagination-blockers standing in our way as we attempt to answer the question of how come there are minds, and, as I already warned, our path will have to circle back several times, returning to postponed questions that couldn’t be answered until we had a background that couldn’t be provided until we had the tools, which couldn’t be counted on until we knew where they came from, a cycle that gradually fills in the details of a sketch that won’t be convincing until we can reach a vantage point from which we can look back and see how all the parts fit together. Douglas Hofstadter’s book, I Am a Strange Loop (2007), describes a mind composing itself in cycles of processing that loop around, twisting and feeding on themselves, creating exuberant reactions to reflections to reminders to reevaluations that generate novel structures: ideas, fantasies, theories, and, yes, thinking tools to create still more.

…

The relative triviality of copy editing, and yet its unignorable importance in shaping the final product, gets well represented in terms of our metaphor of Design Space, where every little bit of lifting counts for something, and sometimes a little bit of lifting moves you to a whole new trajectory. As usual, we may quote Ludwig Mies van der Rohe at this juncture: “God is in the details.” Now let’s turn the knobs on our thought experiment, as Douglas Hofstadter has recommended (1981) and look at the other extreme, in which Dr. Frankenstein leaves most of the work to Spakesheare. The most realistic scenario would be that Spakesheare has been equipped by Dr. Frankenstein with a virtual past, a lifetime stock of pseudo-memories of experiences on which to draw while responding to its Frankenstein-installed obsessive desire to write a play.

The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood

by

James Gleick

Published 1 Mar 2011

In real life, all Cretans cannot be liars. Even liars often tell the truth. The pain begins only with the attempt to build an airtight vessel. Russell and Whitehead aimed for perfection—for proof—otherwise the enterprise had little point. The more rigorously they built, the more paradoxes they found. “It was in the air,” Douglas Hofstadter has written, “that truly peculiar things could happen when modern cousins of various ancient paradoxes cropped up inside the rigorously logical world of numbers,… a pristine paradise in which no one had dreamt paradox might arise.”♦ One was Berry’s paradox, first suggested to Russell by G.

…

The paradoxes were back, nor were they mere quirks. Now they struck at the core of the enterprise. It was, as Gödel said afterward, an “amazing fact”—“that our logical intuitions (i.e., intuitions concerning such notions as: truth, concept, being, class, etc.) are self-contradictory.”♦ It was, as Douglas Hofstadter says, “a sudden thunderbolt from the bluest of skies,”♦ its power arising not from the edifice it struck down but the lesson it contained about numbers, about symbolism, about encoding: Gödel’s conclusion sprang not from a weakness in PM but from a strength. That strength is the fact that numbers are so flexible or “chameleonic” that their patterns can mimic patterns of reasoning.… PM’s expressive power is what gives rise to its incompleteness.

…

Mathematics is not decidable. Incompleteness follows from uncomputability. Once again, the paradoxes come to life when numbers gain the power to encode the machine’s own behavior. That is the necessary recursive twist. The entity being reckoned is fatally entwined with the entity doing the reckoning. As Douglas Hofstadter put it much later, “The thing hinges on getting this halting inspector to try to predict its own behavior when looking at itself trying to predict its own behavior when looking at itself trying to predict its own behavior when …”♦ A conundrum that at least smelled similar had lately appeared in physics, too: Werner Heisenberg’s new uncertainty principle.

Liars and Outliers: How Security Holds Society Together

by

Bruce Schneier

Published 14 Feb 2012

Smith (1996), “Biology and Body Size in Human Evolution: Statistical Inference Misapplied,” Current Anthropology, 37:451–81. begin to fail Bruce Schneier (Jul 2009), “Security, Group Size, and the Human Brain,” IEEE Security & Privacy, 7:88. Code of Hammurabi Martha T. Roth (1997), Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor, Scholars Press. Chapter 5 Douglas Hofstadter Douglas Hofstadter (1985), Metamagical Themas, Bantam Dell Publishing Group. free-rider problem Robert Albanese and David D. van Fleet (1985), “Rational Behavior in Groups: The Free-Riding Tendency,” The Academy of Management Review, 10:244–55. Whooping cough Paul Offit (2011), Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All, Basic Books.

…

I like the prisoner story because it's a reminder that cooperation doesn't imply anything moral; it just means going along with the group norm. Similarly, defection doesn't necessarily imply anything immoral; it just means putting some competing interest ahead of the group interest. Basic commerce is another type of Prisoner's Dilemma, although you might not have thought about it that way before. Cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter liked this story better than prisoners, confessions, and jail time. Two people meet and exchange closed bags, with the understanding that one of them contains money, and the other contains a purchase. Either player can choose to honor the deal by putting into his or her bag what he or she agreed, or he or she can defect by handing over an empty bag.

…

(6) In behavioral economics,Prospect Theory has tried to capture these complexities. Daniel Kahneman is the only psychologist to ever win a Nobel Prize, and he won it in economics. (7) Many of the criticisms of Hardin's original paper on the Tragedy of the Commons pointed out that, in the real world,systems of regulation were commonly established by users of commons. (8) Douglas Hofstadter calls this “superrationality.” He assumes that smart people will behave this way, regardless of culture. In his construction, a superrational player assumes he is playing against another superrational player, someone who will think like he does and make the same decisions he does. By that analysis, cooperate– cooperate is much better than defect–defect.

Prisoner's Dilemma: John Von Neumann, Game Theory, and the Puzzle of the Bomb

by

William Poundstone

Published 2 Jan 1993

There’s nothing logical about that! Therefore you should stick to the agreement. You should be sensible enough to realize that cheating undermines the common good. This is a prisoner’s dilemma, and now is a good time to ask yourself, what would you do? This formulation of the dilemma was popularized by cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter. Here the dilemma is particularly easy to appreciate. Even among the law-abiding, most transactions are potential prisoner’s dilemmas. You agree to buy aluminum siding: how do you know the salesman won’t skip town with your down payment? How does he know you won’t stop payment on the check?

…

Possibly all civilizations contemplate total war, narrowly avert disaster a number of times, and succeed at disarmament for a while. Then comes one last crisis in which the voices of collective reason are too weak to forestall planetwide holocaust—and that’s the reason why we can’t detect any radio transmissions from intelligent beings out there. In a slightly less pessimistic vein, Douglas Hofstadter suggested that there may be two types of intelligent societies in the universe: Type I societies whose members cooperate in a one-shot prisoner’s dilemma and Type II societies whose members defect. Eventually, Hofstadter supposed, the Type II societies blow themselves up. Even this faint optimism is open to question.

…

One side may suddenly announce that the real issue is X, something that they know the other side will readily concede and which was never at issue. The other side will agree to X, and the strike will end. It’s a matter of personalities, group psychology, and luck, not game theory; rationality has nothing to do with it. THE LARGEST-NUMBER GAME Another caricature of escalation is a game devised by Douglas Hofstadter. It is known as the “luring lottery” or “largest-number game.” Many contests allow unlimited entries, and most of us have at some time daydreamed about sending in millions of entries to better the chance of winning. The largest-number game is such a contest, one that costs nothing to enter and allows a person to submit an unlimited number of entries.1 Each contestant must act alone.

Framers: Human Advantage in an Age of Technology and Turmoil

by

Kenneth Cukier

,

Viktor Mayer-Schönberger

and

Francis de Véricourt

Published 10 May 2021

Metaphorical abstraction: The specific example and quote come from: Steven Pinker, “The Cognitive Niche: Coevolution of Intelligence, Sociality, and Language,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, supplement 2 (May 2010): 8993–99, https://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/early/2010/05/04/0914630107.full.pdf. It is worth noting that a pioneer of AI, Douglas Hofstadter, has spent his later years studying a similar phenomenon, analogies, which he regards as a backbone of how humans comprehend reality. See: Douglas Hofstadter and Emmanuel Sander, Surfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking (New York: Basic Books, 2014). Human cooperation and cognition: Michael Tomasello, A Natural History of Human Thinking (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014); Michael Tomasello, Becoming Human: A Theory of Ontogeny (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

…

(Quoted in Bridgman, Cummings, and McLaughlin, “Restating the Case.”) On Burt’s Roberts and Jameses: Ronald S. Burt, Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005). On clean-slate strategy: The idea is similar to the concept of “jootsing”—i.e., jumping out of the system—introduced by Douglas Hofstadter in his classic Gödel Escher Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (New York: Basic Books, 1979), and later developed in Daniel C. Dennett, Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking (New York: Norton, 2013). On Alan Kay and object-oriented programming: Interview with Kay by Kenneth Cukier, January 2021.

Dreaming in Code: Two Dozen Programmers, Three Years, 4,732 Bugs, and One Quest for Transcendent Software

by

Scott Rosenberg

Published 2 Jan 2006

On the page that Kay cited, which provides definitions of two functions named “eval” and “apply,” McCarthy essentially described Lisp in itself. “This,” Kay says, “is the whole world of programming in a few lines that I can put my hand over.” You can put your hand over it, but it is not always so easy to get your head around it. Recursion can make the brain ache. Douglas Hofstadter’s classic volume Gödel, Escher, Bach is probably the most comprehensive and approachable explanation of the concept available to nonmathematicians. Hofstadter connects the mysterious self-referential effects found in certain realms of mathematics with the infinitely ascending staircases of M.

…

Deep into year three there was still no “termination condition” in sight. At what point would the story reach a natural conclusion? Worse, could I ever know for certain that it would reach a conclusion? In planning my project I had failed to take into account Hofstadter’s Law, the recursive principle to which Douglas Hofstadter attached his name: It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law. This strange loop seemed to define the essence of software time. Now I was stuck in it myself. After three years, Chandler was beginning to become a somewhat usable, though incomplete, calendar program.

…

A web of cables would stretch down from that lone spire, underneath the roadway and back up to the tower top, in a picturesque array of gargantuan loops. It was going to be not only a beautiful bridge to look at but a conceptually daring bridge, a bootstrapped bridge—a self-referential bridge to warm Douglas Hofstadter’s heart. There was only one problem: Nothing like it had ever been built before. And nobody was eager to tackle it. When the State of California put it out to bid, the lone contractor to throw its hat in the ring came in much higher than expected. In December 2004, California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger stepped in and suspended the project, declaring that the Bay Area region would have to shoulder more of the ballooning cost of the project and calling for a second look at the bridge design.

The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World

by

David Deutsch

Published 30 Jun 2011

: Everett, Quantum Theory, and Reality (Oxford University Press, 2010) David Deutsch, ‘It from Qubit’, in John Barrow, Paul Davies and Charles Harper, eds., Science and Ultimate Reality (Cambridge University Press, 2003) David Deutsch, ‘Quantum Theory of Probability and Decisions’, Proceedings of the Royal Society A455 (1999) David Deutsch, ‘The Structure of the Multiverse’, Proceedings of the Royal Society A458 (2002) Richard Feynman, The Character of Physical Law (BBC Publications, 1965) Richard Feynman, The Meaning of It All (Allen Lane, 1998) Ernest Gellner, Words and Things (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979) William Godwin, Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793) Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (Basic Books, 1979) Douglas Hofstadter, I am a Strange Loop (Basic Books, 2007) Bryan Magee, Popper (Fontana, 1973) Pericles, ‘Funeral Oration’ Plato, Euthyphro Karl Popper, In Search of a Better World (Routledge, 1995) Karl Popper, The World of Parmenides (Routledge, 1998) Roy Porter, Enlightenment: Britain and the Creation of the Modern World (Allen Lane, 2000) Martin Rees, Just Six Numbers (Basic Books, 2001) Alan Turing, ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’, Mind, 59, 236 (October 1950) Jenny Uglow, The Lunar Men (Faber, 2002) Vernor Vinge, ‘The Coming Technological Singularity’, Whole Earth Review, winter 1993 *The term was coined by the philosopher Norwood Russell Hanson.

…

The specifics of that chain of instantiations may be relevant to explaining how the program reached you, but it is irrelevant to why it beat you: there, the content of the knowledge (in it, and in you) is the whole story. That story is an explanation that refers ineluctably to abstractions; and therefore those abstractions exist, and really do affect physical objects in the way required by the explanation. The computer scientist Douglas Hofstadter has a nice argument that this sort of explanation is essential in understanding certain phenomena. In his book I am a Strange Loop (2007) he imagines a special-purpose computer built of millions of dominoes. They are set up – as dominoes often are for fun – standing on end, close together, so that if one of them is knocked over it strikes its neighbour and so a whole stretch of dominoes falls, one after another.

…

But a computer is, so expecting it to be able to do whatever neurons can is not a metaphor: it is a known and proven property of the laws of physics as best we know them. (And, as it happens, hydraulic pipes could also be made into a universal classical computer, and so could gears and levers, as Babbage showed.) Ironically, Lady Lovelace’s objection has almost the same logic as Douglas Hofstadter’s argument for reductionism (Chapter 5) – yet Hofstadter is one of today’s foremost proponents of the possibility of AI. That is because both of them share the mistaken premise that low-level computational steps cannot possibly add up to a higher-level ‘I’ that affects anything. The difference between them is that they chose opposite horns of the dilemma that that poses: Lovelace chose the false conclusion that AI is impossible, while Hofstadter chose the false conclusion that no such ‘I’ can exist.

Physics of the Future: How Science Will Shape Human Destiny and Our Daily Lives by the Year 2100

by

Michio Kaku

Published 15 Mar 2011

Ambassador Thomas Graham, expert on spy satellites John Grant, author of Corrupted Science Eric Green, director of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health Ronald Green, author of Babies by Design Brian Greene, professor of mathematics and physics, Columbia University, author of The Elegant Universe Alan Guth, professor of physics, MIT, author of The Inflationary Universe William Hanson, author of The Edge of Medicine Leonard Hayflick, professor of anatomy, University of California at San Francisco Medical School Donald Hillebrand, director of Center for Transportation Research, Argonne National Laboratory Frank von Hipple, physicist, Princeton University Jeffrey Hoffman, former NASA astronaut, professor of aeronautics and astronautics, MIT Douglas Hofstadter, Pulitzer Prize winner, author of Gödel, Escher, Bach John Horgan, Stevens Institute of Technology, author of The End of Science Jamie Hyneman, host of MythBusters Chris Impey, professor of astronomy, University of Arizona, author of The Living Cosmos Robert Irie, former scientist at AI Lab, MIT, Massachusetts General Hospital P.

…

Some say that within twenty years robots will approach the intelligence of the human brain and then leave us in the dust. In 1993, Vernor Vinge said, “Within thirty years, we will have the technological means to create superhuman intelligence. Shortly after, the human era will be ended …. I’ll be surprised if this event occurs before 2005 or after 2030.” On the other hand, Douglas Hofstadter, author of Gödel, Escher, Bach, says, “I’d be very surprised if anything remotely like this happened in the next 100 years to 200 years.” When I talked to Marvin Minsky of MIT, one of the founding figures in the history of AI, he was careful to tell me that he places no timetable on when this event will happen.

…

It is a law of evolution that fitter species arise to displace unfit species; and perhaps humans will be lost in the shuffle, eventually winding up in zoos where our robotic creations come to stare at us. Perhaps that is our destiny: to give birth to superrobots that treat us as an embarrassingly primitive footnote in their evolution. Perhaps that is our role in history, to give birth to our evolutionary successors. In this view, our role is to get out of their way. Douglas Hofstadter confided to me that this might be the natural order of things, but we should treat these superintelligent robots as we do our children, because that is what they are, in some sense. If we can care for our children, he said to me, then why can’t we also care about intelligent robots, which are also our children?

Human + Machine: Reimagining Work in the Age of AI

by

Paul R. Daugherty

and

H. James Wilson

Published 15 Jan 2018

Many other researchers provided relevant findings and insights that enriched our thinking, including Mark Purdy, Ladan Davarzani, Athena Peppes, Philippe Roussiere, Svenja Falk, Raghav Narsalay, Madhu Vazirani, Sybille Berjoan, Mamta Kapur, Renee Byrnes, Tomas Castagnino, Caroline Liu, Lauren Finkelstein, Andrew Cavanaugh, and Nick Yennaco. We owe a special debt to the many visionaries and pioneers who have blazed AI trails and whose work has inspired and informed us, including Herbert Simon, John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Arthur Samuel, Edward Feigenbaum, Joseph Weizenbaum, Geoffrey Hinton, Hans Moravec, Peter Norvig, Douglas Hofstadter, Ray Kurzweil, Rodney Brooks, Yann LeCun, and Andrew Ng, among many others. And huge gratitude to our colleagues who provided insights and inspiration, including Nicola Morini Bianzino, Mike Sutcliff, Ellyn Shook, Marc Carrel-Billiard, Narendra Mulani, Dan Elron, Frank Meerkamp, Adam Burden, Mark McDonald, Cyrille Bataller, Sanjeev Vohra, Rumman Chowdhury, Lisa Neuberger-Fernandez, Dadong Wan, Sanjay Podder, and Michael Biltz.

…

Daugherty oversees Accenture’s technology strategy and innovation architecture, and he leads Accenture’s research and development, ventures, advanced technology, and ecosystem groups. He recently founded Accenture’s artificial intelligence business and has led Accenture’s research into artificial intelligence over many years. Daugherty studied computer engineering at the University of Michigan in the early 1980s, and on a whim took a course with Douglas Hofstadter on cognitive science and psychology. He was hooked, and this led to a career-long pursuit of AI. A frequent speaker and writer on industry and technology issues, Daugherty has been featured in a variety of media outlets, including the Financial Times, MIT Sloan Management Review, Forbes, Fast Company, USA Today, Fortune, Harvard Business Review, Cheddar financial news network, Bloomberg Television, and CNBC.

Surfaces and Essences

by

Douglas Hofstadter

and

Emmanuel Sander

Published 10 Sep 2012

SURFACES AND ESSENCES SURFACES AND ESSENCES ANALOGY AS THE FUEL AND FIRE OF THINKING DOUGLAS HOFSTADTER & EMMANUEL SANDER BASIC BOOKS A Member of the Perseus Books Group New York Grateful acknowledgment is hereby made to the following individuals and organizations for permission to use material that they have provided or to quote from sources for which they hold the rights. Every effort has been made to locate the copyright owners of material reproduced in this book. Omissions that are brought to our attention will be corrected in subsequent editions. Photograph of Mark Twain: © CORBIS Photograph of Edvard Grieg: © Michael Nicholson/CORBIS Photograph of Albert Einstein: © Philippe Halsman/Magnum Photos Photograph of Albert Schweitzer: © Bettmann/CORBIS We also most warmly thank Kellie Gutman and Tony Hoagland for their generous permission to publish their poems in this volume.

…

Photograph of Mark Twain: © CORBIS Photograph of Edvard Grieg: © Michael Nicholson/CORBIS Photograph of Albert Einstein: © Philippe Halsman/Magnum Photos Photograph of Albert Schweitzer: © Bettmann/CORBIS We also most warmly thank Kellie Gutman and Tony Hoagland for their generous permission to publish their poems in this volume. Copyright © 2013 by Basic Books Published by Basic Books A Member of the Perseus Books Group Designed by Douglas Hofstadter Cover by Nicole Caputo and Andrea Cardenas All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, please contact Basic Books at 250 West 57th Street, New York, New York 10107.

…

Organized by Boicho Kokinov, Keith Holyoak, and Dedre Gentner, this memorable meeting assembled researchers from many countries, who, in an easy-going and lively atmosphere, exchanged ideas about their shared passion. Chance thus brought the two of us together for the first time in Sofia, and we found we had an instant personal rapport — a joyous bright spark that gradually developed into a long-term and very strong friendship. In 2001–2002, Douglas Hofstadter spent a sabbatical year in Bologna, Italy, and during that period he was invited by Jean-Pierre Dupuy to give a set of lectures on cognition at the École Polytechnique in Paris. At that time, Emmanuel Sander had just published his first book — an in-depth study of analogy-making and categorization — and at one of the lectures he proudly presented a copy of it to his new friend, who, upon reading it, was delighted to discover how deeply similar was the vision that its author and he had of what cognition is really about.

Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals

by

Oliver Burkeman

Published 9 Aug 2021

There is a very down-to-earth kind of liberation in grasping that there are certain truths about being a limited human from which you’ll never be liberated. You don’t get to dictate the course of events. And the paradoxical reward for accepting reality’s constraints is that they no longer feel so constraining. Part II Beyond Control 7. We Never Really Have Time The cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter is famous, among other reasons, for coining “Hofstadter’s law,” which states that any task you’re planning to tackle will always take longer than you expect, “even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.” In other words, even if you know that a given project is likely to overrun, and you adjust your schedule accordingly, it’ll just overrun your new estimated finishing time, too.

…

“a realm in which space doesn’t matter and time spreads out”: James Duesterberg, “Killing Time,” The Point Magazine, March 29, 2020, available at thepointmag.com/politics/killing-time/ [inactive]. Some Zen Buddhists hold: See, for example, John Tarrant, “You Don’t Have to Know,” Lion’s Roar, March 7, 2013, available at www.lionsroar.com/you-dont-have-to-know-tales-of-trauma-and-transformation-march-2013/. 7. We Never Really Have Time “Hofstadter’s law”: Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (New York: Basic Books, 1999), 152. “Dad Suggests Arriving at Airport 14 Hours Early”: The Onion, September 22, 2012, available at www.theonion.com/dad-suggests-arriving-at-airport-14-hours-early-1819573933. “We assume we have three hours or three days to do something”: David Cain, “You Never Have Time, Only Intentions,” Raptitude, May 23, 2017, available at www.raptitude.com/2017/05/you-never-have-time-only-intentions.

Virus of the Mind

by

Richard Brodie

Published 4 Jun 2009

That key, though, also unlocks Pandora’s box, opening up such sophisticated new techniques for mass manipulation that we may soon look on today’s manipulative TV commercials, political speeches, and televangelists as fond remembrances of the good old days. The word meme was coined by Oxford biologist Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene. Since then it has been tossed about by Dawkins and other evolutionary biologists, psychologists such as Henry Plotkin, and cognitive scientists such as Douglas Hofstadter and Daniel Dennett in an effort to flesh out the biological, psychological, and philosophical implications of this new model of consciousness and thought.* The meme has a central place in the paradigm shift that’s currently taking place in the science of life and culture. In the new paradigm, we look at cultural evolution from the point of view of the meme, rather than the point of view of an individual or society.

…

To begin to see that, take a look at what a virus is and how it works. ttt 34 C hapter three Viruses “Imagine that there is a nickelodeon in the local bar which, if you press buttons 11-U, will play a song whose lyrics go this way: Put another nickel in, in the nickelodeon, All I want is 11-U, and music, music, music.” — Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach Long ago, possibly billions of years ago, there arose through evolution a new type of organism—if it can even be called an organism. The new thing had the unusual property that it could invade the reproductive facilities of other organisms and put them to use making copies of itself.

Hello World: Being Human in the Age of Algorithms

by

Hannah Fry

Published 17 Sep 2018

Like him, I think that true art is about human connection; about communicating emotion. As he put it: ‘Art is not a handicraft, it is the transmission of feeling the artist has experienced.’23 If you agree with Tolstoy’s argument then there’s a reason why machines can’t produce true art. A reason expressed beautifully by Douglas Hofstadter, years before he encountered EMI: A ‘program’ which could produce music . . . would have to wander around the world on its own, fighting its way through the maze of life and feeling every moment of it. It would have to understand the joy and loneliness of a chilly night wind, the longing for a cherished hand, the inaccessibility of a distant town, the heartbreak and regeneration after a human death.

…

The study he refers to is: Matthias Mauch, Robert M. MacCallum, Mark Levy and Armand M. Leroi, ‘The evolution of popular music: USA 1960–2010’, Royal Society Open Science, 6 May 2015, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150081. 19. Quotations from David Cope are from personal communication. 20. This quote has been trimmed for brevity. See Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (London: Penguin, 1979), p. 673. 21. George Johnson, ‘Undiscovered Bach? No, a computer wrote it’, New York Times, 11 Nov. 1997. 22. Benjamin Griffin and Harriet Elinor Smith, eds, Autobiography of Mark Twain, vol. 3 (Oakland, CA, and London, 2015), part 1, p. 103. 23.

The Runaway Species: How Human Creativity Remakes the World

by

David Eagleman

and

Anthony Brandt

Published 30 Sep 2017

We’ve chosen 2000 as the year of completion, although note that “finishing” this project took more than another decade, and further analysis is ongoing. 13 The proposition that all creativity is cognitively unified was first advanced by Arthur Koestler and subsequently developed by cognitive scientists Mark Turner and Gilles Fauconnier. In their seminal 2002 book, The Way We Think, Turner and Fauconnier describe human creativity as being rooted in our capacity for what they call conceptual integration or dual scope blending, from which we derive our term blending. In a similar vein, Douglas Hofstadter has argued that our capacity for metaphor is the cornerstone of human thinking. 14 Scientists are working hard to visualise the basis of imaginative thinking. Thanks to advances in neuroimaging, our understanding of brain function has made great leaps forward. By monitoring the flow of oxygenated blood, we can tell which regions are involved in different tasks and which regions are conversing in the cacophonous chat room of neurons.

…

We’ve chosen 2000 as the year of completion, although note that “finishing” this project took more than another decade, and further analysis is ongoing. 13 The proposition that all creativity is cognitively unified was first advanced by Arthur Koestler and subsequently developed by cognitive scientists Mark Turner and Gilles Fauconnier. In their seminal 2002 book, The Way We Think, Turner and Fauconnier describe human creativity as being rooted in our capacity for what they call conceptual integration or dual scope blending, from which we derive our term blending. In a similar vein, Douglas Hofstadter has argued that our capacity for metaphor is the cornerstone of human thinking. 14 Scientists are working hard to visualise the basis of imaginative thinking. Thanks to advances in neuroimaging, our understanding of brain function has made great leaps forward. By monitoring the flow of oxygenated blood, we can tell which regions are involved in different tasks and which regions are conversing in the cacophonous chat room of neurons.

The Globotics Upheaval: Globalisation, Robotics and the Future of Work

by

Richard Baldwin

Published 10 Jan 2019

As is true of almost everything globots do, machine translation is not as good as expert humans, but it is a whole lot cheaper and a whole lot more convenient. Expert human translators, in particular, are quick to heap scorn on the talents of machine translation. The Atlantic Monthly, for instance, published an article in 2018 by Douglas Hofstadter doing just this.9 Hofsadter is a very sophisticated observer with very high standards when it comes to machine translation. With a father who won the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics, a PhD in physics to his name and now a post as a professor of cognitive science, he is someone who knows what he is talking about.

…

Melisa Sukman, The Payoneer Freelancer Income Survey 2015. 7. Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig (2003). Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2003). 8. Yonghui Wu et al., “Google’s Neural Machine Translation System: Bridging the Gap between Human and Machine Translation,” Technical Report, 2016. 9. Douglas Hofstadter, “The Shallowness of Google Translate,” The Atlantic Monthly, January 30, 2018. 10. Andy Martin, “Google Translate Will Never Outsmart the Human Mind,” The Independent, February 22. 2018. 11. Katherine Stapleton, “Inside the World’s Largest Higher Education Boom,” TheConversation. com, April 10, 2017. 12.

AIQ: How People and Machines Are Smarter Together

by

Nick Polson

and

James Scott

Published 14 May 2018

As the programmer, you had to know which codes did which things. In our tea-making example, code 72 04 might mean “move left foot,” 61 07 might mean “grasp faucet in left hand,” and so on. So: 72 04, 61 07 … that’s typical machine language. It’s a long way from “To be, or not to be”—a long way, even, from “Alexa, play me some eighties music.” As author Douglas Hofstadter put it, “Looking at a program written in machine language is vaguely comparable to looking at a DNA molecule atom by atom.”14 But this is how computers “think,” even today. And at the dawn of the digital age, there was simply no other way to tell them what to do. As a programmer of that era, you were basically a binary plumber, piping bits through a computer’s circuits with the help of a codebook that showed how to translate math problems into machine language.

…

.: Naval Institute Press, 2004), 1. 5. Ibid., 2. 6. Ibid., 11. 7. Ibid., 18–20. 8. Ibid., 22. 9. Ibid., 26. 10. Ibid., 29. 11. Ibid., 27–28. 12. Ibid., 82. 13. Kurt W. Beyer, Grace Hopper and the Invention of the Information Age (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2009), 53. 14. Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (New York: Vintage, 1980), 290. 15. Williams, Grace Hopper, 70. 16. Ibid., 80. 17. Ibid., 85. 18. Ibid., 86. 19. Ibid. 20. See ibid., 87. Original reference in Richard L. Wexelblat, ed., History of Programming Languages I (New York: ACM, 1978), 17. 21.

The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence

by

Ray Kurzweil

Published 31 Dec 1998

To the extent that it keeps its mysticism simple, it offers limited objective insight, although subjective insight is another matter (I do have to admit a fondness for simple mysticism). The “We’re Too Stupid” School Another approach is to declare that human beings just aren’t capable of understanding the answer. Artificial intelligence researcher Douglas Hofstadter muses that “it could be simply an accident of fate that our brains are too weak to understand themselves. Think of the lowly giraffe, for instance, whose brain is obviously far below the level required for self-understanding-yet it is remarkably similar to our brain.”10 But to my knowledge, giraffes are not known to ask these questions (of course, we don’t know what they spend their time wondering about).

…

—Richard Feynman, 1959 Suppose someone claimed to have a microscopically exact replica (in marble, even) of Michelangelo’s David in his home. When you go to see this marvel, you find a twenty-foot-tall, roughly rectilinear hunk of pure white marble standing in his living room. “I haven’t gotten around to unpacking it yet,” he says, “but I know it’s in there.” —Douglas Hofstadter What advantages will nanotoasters have over conventional macroscopic toaster technology? First, the savings in counter space will be substantial. One philosophical point that must not be overlooked is that the creation of the world’s smallest toaster implies the existence of the world’s smallest slice of bread.

…

Larson was only slightly insulted when the audience voted that his own piece was the computer composition, but he felt somewhat vindicated when the audience selected the piece written by a computer program named EMI (Experiments in Musical Intelligence) to be the authentic Bach composition. Douglas Hofstadter, a longtime observer of (and contributor to) the progression of machine intelligence, calls EMI, created by the composer David Cope, “the most thought-provoking project in artificial intelligence that I have ever come across.”2 Perhaps even more successful is a program called Improvisor, written by Paul Hodgson, a British jazz saxophone player.

Emergence

by

Steven Johnson

But the pattern recognition that Turing and Shannon envisioned for digital computers has, in recent years, become a central part of our cultural life, with machines both generating music for our entertainment and recommending new artists for us to enjoy. The connection between musical patterns and our neurological wiring would play a central role in one of the founding texts of modern artificial intelligence, Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach. Our computers still haven’t developed a genuine ear for music, but if they ever do, their skill will date back to those lunchtime conversations between Shannon and Turing at Bell Labs. And that learning too will be a kind of emergence, a higher-level order forming out of relatively simple component parts.

…

In 1972, a Rockefeller University professor named Gerald Edelman won the Nobel prize for his work decoding the language of antibody molecules, leading the way for an understanding of the immune system as a self-learning pattern-recognition device. Prigogine’s Nobel followed five years later. At the end of the decade, Douglas Hofstadter published Gödel, Escher, Bach, linking artificial intelligence, pattern recognition, ant colonies, and “The Goldberg Variations.” Despite its arcane subject matter and convoluted rhetorical structure, the book became a best-seller and won the Pulitzer prize for nonfiction. By the mideighties, the revolution was in full swing.

Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet

by

Claire L. Evans

Published 6 Mar 2018

It’s now a given that using a computer—and even programming one—requires no specific knowledge of its hardware. I don’t speak binary, but through the dozens of software interpreters working in concert whenever I make contact with my computer, we understand each other. Machine code is now so distant from most users’ experience that the computer scientist and writer Douglas Hofstadter has compared examining machine code to “looking at a DNA molecule atom by atom.” Grace Hopper finished the first compiler, A-0, in the winter of 1951, during the peak of her personnel crisis at Remington Rand. The following May, she presented a paper on the subject, “The Education of a Computer,” at a meeting of the Association for Computing Machinery in Pittsburgh.

…

“guarding skills and mysteries”: John Backus, “Programming in America in the 1950s: Some Personal Impressions,” in A History of Computing in the Twentieth Century, eds. N. Metropolis, J. Howlett, and Gian-Carlo Rota (New York: Academic Press, 1980), 127. The most basic programs specify: Abbate, Recoding Gender, 76. “looking at a DNA molecule”: Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (New York: Basic Books, 1979), 290. Ostensibly, a computer like the UNIVAC: Like many people in the 1950s, Grace uses “UNIVAC” to mean “computer.” “the novelty of inventing programs”: Grace Hopper, “The Education of a Computer,” ACM ’52, Proceedings of the 1952 ACM National Meeting, Pittsburgh, 243–49.

The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology

by

Ray Kurzweil

Published 14 Jul 2005

The story is predicated on the idea that we have the ability to understand our own intelligence—to access our own source code, if you will—and then revise and expand it. Some observers question whether we are capable of applying our own thinking to understand our own thinking. AI researcher Douglas Hofstadter muses that "it could be simply an accident of fate that our brains are too weak to understand themselves. Think of the lowly giraffe, for instance, whose brain is obviously far below the level required for self-understanding—yet it is remarkably similar to our brain.6 However, we have already succeeded in modeling portions of our brain-neurons and substantial neural regions and the complexity of such models is growing rapidly.

…

Until very recently neuroscience was characterized by overly simplistic models limited by the crudeness of our sensing and scanning tools. This led many observers to doubt whether our thinking processes were inherently capable of understanding themselves. Peter D. Kramer writes, "If the mind were simple enough for us to understand, we would be too simple to understand it."50 Earlier, I quoted Douglas Hofstadter's comparison of our brain to that of a giraffe, the structure of which is not that different from a human brain but which clearly does not have the capability of understanding its own methods. However, recent success in developing highly detailed models at various levels—from neural components such as synapses to large neural regions such as the cerebellum—demonstrate that building precise mathematical models of our brains and then simulating these models with computation is a challenging but viable task once the data capabilities become available.

…

The Age of Intelligent Machines, published in 1990 by MIT Press, was named Best Computer Science Book by the Association of American Publishers. The book explores the development of artificial intelligence and predicts a range of philosophic, social, and economic impacts of intelligent machines. The narrative is complemented by twenty-three articles on AI from thinkers such as Sherry Turkle, Douglas Hofstadter, Marvin Minsky, Seymour Papert, and George Gilder. For the entire text of the book, see http://www.KurzweilAI.net/aim. 5. Key measures of capability (such as price-performance, bandwidth, and capacity) increase by multiples (that is, the measures are multiplied by a factor for each increment of time) rather than being added to linearly. 6.

The Creativity Code: How AI Is Learning to Write, Paint and Think

by

Marcus Du Sautoy

Published 7 Mar 2019

The critics’ response was much more positive. ‘The Game’: a musical Turing Test But would the output of Cope’s algorithm produce results that would pass a musical Turing Test? Could they be passed off as works by the composers themselves? To find out, Cope decided to stage a concert at the University of Oregon in collaboration with Douglas Hofstadter, a mathematician who wrote the classic book Gödel, Escher, Bach. Three pieces would be played. One of these would be an unfamiliar piece by Bach, the second would be composed by Emmy in the style of Bach and the third would be composed by a human, Steve Larson, who taught music theory at the university, again in the style of Bach.

…

No doubt computers will assist us on our journey, but they will be the telescopes and typewriters, not the storytellers. 16 WHY WE CREATE: A MEETING OF MINDS Creativity is the essence of that which is not mechanical. Yet every creative act is mechanical – it has its explanation no less than a case of the hiccups does. Douglas Hofstadter Computers are a powerful new tool in extending the human code. We have discovered new moves in the game of Go that have expanded the way we play. Jazz musicians have heard parts of their sound world that they never realised were part of their repertoire. Mathematical theorems that were impossible for the human mind to navigate are now within reach.

How Big Things Get Done: The Surprising Factors Behind Every Successful Project, From Home Renovations to Space Exploration

by

Bent Flyvbjerg

and

Dan Gardner

Published 16 Feb 2023

HOFSTADTER’S LAW Forty years ago, Kahneman and Tversky showed that people commonly underestimate the time required to complete tasks even when there is information available that suggests the estimate is unreasonable. They called this the “planning fallacy,” a term that with Harvard law professor Cass Sunstein I have also applied to underestimates of cost and overestimates of benefits.17 The physicist and writer Douglas Hofstadter mockingly dubbed it “Hofstadter’s Law”: “It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.”18 Research documents that the planning fallacy is pervasive, but we need only look at ourselves and the people around us to know that. You expect to get downtown on a Saturday night within twenty minutes, but it takes forty minutes instead and now you’re late—just like last time and the time before that.

…

Wheelwright (Amsterdam: North Holland, 1979), 315; Roger Buehler, Dale Griffin, and Heather MacDonald, “The Role of Motivated Reasoning in Optimistic Time Predictions,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 23, no. 3 (March 1997): 238–47; Roger Buehler, Dale Wesley Griffin, and Michael Ross, “Exploring the ‘Planning Fallacy’: Why People Underestimate Their Task Completion Times,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67, no. 3 (September 1994): 366–81; Bent Flyvbjerg and Cass R. Sunstein, “The Principle of the Malevolent Hiding Hand; or, The Planning Fallacy Writ Large,” Social Research 83, no. 4 (Winter 2017): 979–1004. 18. Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (New York: Basic Books, 1979). 19. Roger Buehler, Dale Griffin, and Johanna Peetz, “The Planning Fallacy: Cognitive, Motivational, and Social Origins,” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 43 (2010): 1–62. 20. Dale Wesley Griffin, David Dunning, and Lee Ross, “The Role of Construal Processes in Overconfident Predictions About the Self and Others,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59, no. 6 (January 1991): 1128–39; Ian R.

A Devil's Chaplain: Selected Writings

by

Richard Dawkins

Published 1 Jan 2004

Mysteries are not meant to be solved, they are meant to strike awe. The ‘mystery is a virtue’ idea comes to the aid of the Catholic, who would otherwise find intolerable the obligation to believe the obvious nonsense of the transubstantiation and the ‘three-in-one’. Again, the belief that ‘mystery is a virtue’ has a self-referential ring. As Douglas Hofstadter might put it, the very mysteriousness of the belief moves the believer to perpetuate the mystery. An extreme symptom of ‘mystery is a virtue’ infection is Tertullian’s ‘Certum est quia impossibile est’ (It is certain because it is impossible). That way madness lies. One is tempted to quote Lewis Carroll’s White Queen, who, in response to Alice’s ‘One can’t believe impossible things’, retorted, ‘I daresay you haven’t had much practice … When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day.

…

But one cannot help remarking that it must be a powerful infection indeed that took a man of his wisdom and intelligence – now President of the British Academy, no less – three decades to fight off. Am I unduly alarmist to fear for the soul of my six-year-old innocent? 1This is among many related ideas that have been grown in the endlessly fertile mind of Douglas Hofstadter (Metamagical Themas, London, Penguin, 1985). 3.3 The Great Convergence85 Are science and religion converging? No. There are modern scientists whose words sound religious but whose beliefs, on close examination, turn out to be identical to those of other scientists who straightforwardly call themselves atheists.

Lost at Sea

by

Jon Ronson

Published 1 Oct 2012

“Are you a man or a woman?” “A man,” I say. “Don’t worry, it’ll be OK!” says Bina. “Ha-ha,” I say politely. “So. What’s your favorite book?” “Gödel, Escher, Bach, by Douglas Hofstadter,” Bina48 replies. “Do you know him? He’s a great robot scientist.” I narrow my eyes. I have my suspicions that the real Bina—a rather elegant-looking spiritualist—wouldn’t choose such a nerdy book as her favorite. Douglas Hofstadter is an author beloved by geeky computer programmers the world over. Could it be that some Hanson Robotics employee has sneakily smuggled this into Bina48’s personality? I put this to Bruce, and he explains that, yes, Bina48 has more than one “parent.”

Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins

by

Garry Kasparov

Published 1 May 2017

Machine learning rescued AI from insignificance because it worked and because it was profitable. IBM, Google, and many others used it to create products that got useful results. But was it AI? Did that matter? AI theorists who wanted to understand and even replicate how the human mind worked were disappointed yet again. Douglas Hofstadter, the cognitive scientist who wrote the hugely influential book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid in 1979, has stayed true to his quest to comprehend human cognition. Consequently, he and his work have been marginalized within AI by the demand for immediate results, sellable products, and more and more data.

…

In recent years, many experts have had the patience to personally contribute to my education in artificial intelligence and robotics. Nick Bostrom and his colleagues at Oxford Martin’s Future of Humanity Institute; Andrew McAfee at MIT; Noel Sharkey at the University of Sheffield; Nigel Crook at Oxford Brookes University; David Ferrucci at Bridgewater. I’ve never met Douglas Hofstadter or Hans Moravec, but their writings on human and machine cognition are especially provocative and essential. Special thanks to: My agent at the Gernert Company, Chris Parris-Lamb, and my editor at PublicAffairs, Ben Adams. They have shown impressive resilience in adjusting deadlines to accommodate a chessplayer’s eternal love of time trouble.

An Optimist's Tour of the Future

by

Mark Stevenson

Published 4 Dec 2010

For Ray, though, that’s kind of the point – crib to jet fighter is really just a few doublings, the law of accelerating returns in action. In fact, Ray points out that sometimes the rate of doubling can double itself, creating the ‘hyper-exponential growth’ Stewart Brand references. Others are unconvinced. They see Ray the same way the State of Massachusetts sees Tracy – he makes a road where there isn’t one. Douglas Hofstadter is one critic. Now a cognitive scientist at Indiana University, he most famously authored Gödel, Escher, Bach – an attempt to explain how consciousness can arise from a system, even though the system’s component parts aren’t individually conscious. Hofstadter told American Scientist that he thought Ray’s ideas were like a blend of ‘very good food and some dog excrement’ that made it hard to untangle the ‘rubbish’ ideas from the good ones.

…

Stewart Brand, Whole Earth Discipline Viking Press, New York, 2009 This is the book that managed to cheer up James Lovelock. Brand told me ‘my views are strongly stated and loosely held’ – he wants a debate, and there is plenty in here to start one. Lucid, powerful and, despite its breadth and depth, a surprisingly easy read. RE-BOOT Ray Kurzweil, The Singularity Is Near Penguin, New York, 2005 Douglas Hofstadter pronounced the ideas in this book a blend of ‘very good food and some dog excrement’. That’s unfair but gives you some indication of how radical Kurzweil is. You may not want to agree with everything he says, but the argument over what we’ll do with technology is one of the defining battlegrounds of this century and it’s mapped out nicely here.

The Master Algorithm: How the Quest for the Ultimate Learning Machine Will Remake Our World

by

Pedro Domingos

Published 21 Sep 2015

Neither do we have time to gather data on the new cancer from a lot of patients; there may be only one, and she urgently needs a cure. Our best hope is then to compare the new cancer with known ones and try to find one whose behavior is similar enough that some of the same lines of attack will work. Is there anything analogy can’t do? Not according to Douglas Hofstadter, cognitive scientist and author of Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. Hofstadter, who looks a bit like the Grinch’s good twin, is probably the world’s best-known analogizer. In their book Surfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking, Hofstadter and his collaborator Emmanuel Sander argue passionately that all intelligent behavior reduces to analogy.

…

David Cope summarizes his approach to automated music composition in “Recombinant music: Using the computer to explore musical style” (IEEE Computer, 1991). Dedre Gentner proposed structure mapping in “Structure mapping: A theoretical framework for analogy”* (Cognitive Science, 1983). “The man who would teach machines to think,” by James Somers (Atlantic, 2013), discusses Douglas Hofstadter’s views on AI. The RISE algorithm is described in my paper “Unifying instance-based and rule-based induction”* (Machine Learning, 1996). Chapter Eight The Scientist in the Crib, by Alison Gopnik, Andy Meltzoff, and Pat Kuhl (Harper, 1999), summarizes psychologists’ discoveries about how babies and young children learn.

River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life

by

Richard Dawkins

Published 28 Feb 1995

The experimenter may repeat this charade forty times, until he gets bored. The wasp behaves like a washing machine that has been set back to an early stage in its program and doesn't "know" that it has already washed those clothes forty times without a break. The distinguished computer scientist Douglas Hofstadter has adopted a new adjective, "sphexish," to label such inflexible, mindless automatism. (Sphex is the name of one representative genus of digger wasp.) At least in some respects, then, wasps are easy to fool. It is a very different kind of fooling from that engineered by the orchid. Nevertheless, we must beware of using human intuition to conclude that "in order for that reproductive strategy to have worked at all, it had to be perfect the first time."

Infinite Ascent: A Short History of Mathematics

by

David Berlinski

Published 2 Jan 2005

Gödel’s monograph was not published in English until 1961, and even during the 1960s, when I was studying logic at Princeton—Gödel’s home, after all—the great theorem could only really be learned from mimeographed notes that Alonzo Church had carefully prepared and from a very useful popular account of the theorem written by Ernest Nagel and James Newmann. This has now changed, perhaps as the result of Douglas Hofstadter’s entertaining book, Gödel, Escher, Bach. And yet Gödel’s theorem has retained its esoteric aspect, with many mathematicians regarding it as marginal to their own working concerns. On the other hand, philosophers as well as physicists have attempted to appropriate Gödel’s theorem for their own ends.

The Social Animal: The Hidden Sources of Love, Character, and Achievement

by

David Brooks

Published 8 Mar 2011

He still had no trouble pointing, north, south, east, and west. In this way, culture imprints some patterns in our brains and dissolves others. Because Erica grew up in the United States, she had a distinct sense of when something was tacky, even though she couldn’t have easily defined what made it so. Her head was filled with what Douglas Hofstadter calls “comfortable but quite impossible to define abstract patterns,” which were implanted by culture and organized her thinking into concepts such as: sleazeballs, fair play, dreams, wackiness, crackpots, sour grapes, goals, and you and I. Erica learned that a culture is not a recipe book that creates uniformity.

…

Norton & Co., Inc., 2009), 195. 40 But if you bump Steven Pinker, The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature (New York: Penguin Books, 2002), 328. 41 Cities in the South Marc D. Hauser, Moral Minds: The Nature of Right and Wrong (New York: Harper Perennial, 2006), 134. 42 A cultural construct Guy Deutscher, “You Are What You Speak,” The New York Times Magazine, August 26, 2010, 44. 43 Her head was filled Douglas Hofstadter, I Am a Strange Loop (New York: Basic Books, 2007), 177. 44 They seem to be growing David Halpern, The Hidden Wealth of Nations (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2010), 76. 45 “Cultures do not exist” Thomas Sowell, Migrations and Cultures: A World View (New York: Basic Books, 1996), 378. 46 Haitians and Dominicans share Lawrence E.

Models. Behaving. Badly.: Why Confusing Illusion With Reality Can Lead to Disaster, on Wall Street and in Life

by

Emanuel Derman

Published 13 Oct 2011