The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars

by Dava Sobel · 6 Dec 2016 · 442pp · 110,704 words

later he was dead. • • • IN THE OUTFLOW OF CONDOLENCES following her husband’s funeral, Anna Palmer Draper drew some comfort from a correspondence with Professor Edward Pickering of the Harvard College Observatory, one of the guests at the Academy gathering the night of Henry’s collapse. “My dear Mrs. Draper,” Pickering wrote

…

for taking in huge tracts of sky all at once, rather than homing in on single objects. In less than a decade at the helm, Edward Pickering had shifted the observatory’s institutional emphasis from the old astronomy, centered on star positions, to novel investigations into the stars’ physical nature. While half

…

. At 8,000 feet, the air was clear, dry, and steady, and the nearby volcano, El Misti, was nearly extinct. • • • WHILE THE BAILEYS EXPLORED PERU, Edward Pickering became engrossed with the odd spectrum of a star called Mizar in the handle of the Big Dipper. The star had first drawn his surprised

…

—and hers—seemed full of promise. CHAPTER THREE Miss Bruce’s Largesse EVEN BEFORE SOLON BAILEY selected the site for Harvard’s Southern Hemisphere observatory, Edward Pickering had envisioned a superb new telescope to mount there. This ideal instrument would have a lens 24 inches in diameter, or triple the size of

…

junctions he dubbed “lakes.” William communicated these same findings to the editors of the New York Herald, who printed them to sensational effect. An exasperated Edward Pickering complained to William on August 24 that the waters of Mars had generated a “flood” of forty-nine newspaper cuttings in one morning. He admonished

…

telescope made its slow way up Summerhouse Hill. Placement of the two-ton bed plate occupied six men and four horses for a full day. Edward Pickering watched the “ponderous affair” of assembly wear on for two more months before he got the proof he needed to declare the whole grand giant

…

for his first serious endeavor in the field. A Boston Brahmin and Harvard alumnus, Lowell knew the Pickering brothers socially through the Appalachian Mountain Club. Edward Pickering granted William a year’s leave without pay to join Lowell’s “Arizona Astronomical Expedition.” He also allowed Lowell the yearlong lease of a 12

…

violently.” Bailey was pleased to report, however, that all the station’s telescopes emerged from the shaking unscathed. CHAPTER FIVE Bailey’s Pictures from Peru EDWARD PICKERING HAD COME TO VIEW Solon Bailey as the heir apparent to the Harvard throne. “You are more familiar with the work of the Observatory in

…

be considered of any assistance to such a thoroughly capable Scientific man as our Director.” Throughout her journal, Mrs. Fleming expressed only positive sentiments about Edward Pickering, except on the matter of her remuneration. When she engaged him on March 12 in “some conversation” about pay, she got no satisfaction. “He seems

…

to the Observatory, but when I compare the compensation with that received by women elsewhere, I feel that my work cannot be of much account.” • • • EDWARD PICKERING HIGHLY VALUED the accomplishments and industry of Mrs. Fleming. Indeed, he planned to nominate her for the 1900 Bruce Medal. Who better? In view of

…

orbit, but none of the computers could be spared to assist him. As usual at the Harvard Observatory, the stars took precedence over the planets. Edward Pickering kept fellow astronomers abreast of Miss Leavitt’s advances by issuing a rapid-fire series of circulars. A few of these publications included small prints

…

volunteers, the observatory served as the new unofficial headquarters. To further cement the Harvard connection, the organization inducted Solon Bailey, Annie Cannon, Henrietta Leavitt, and Edward Pickering as honorary members, with a special tribute for the director: “He has assisted us in everything that we have undertaken, and has carefully watched our

…

he needed to be helped over the few steps home to his residence. The cause of his death, on February 3, was given as pneumonia. Edward Pickering had been director of the Harvard College Observatory for forty-two years, serving longer than the combined tenures of all his predecessors. Anguish at his

…

the observatory. While seeking funding, he honored and tallied the urgent requests from individual astronomers for particular spectra. Hundreds of such queries arrived every month. Edward Pickering had told President Lowell in 1910 that he considered Professor Bailey the only member of his staff capable of taking over the observatory as acting

…

recently won him the National Academy of Sciences medal perpetuating the name of Dr. Henry Draper. The small, elite fraternity of Draper Medal winners included Edward Pickering, George Ellery Hale, Henry Norris Russell, and Arthur Stanley Eddington. Shapley thought the time ripe to add a woman’s name to that roster, and

…

to another as they age; and Hans Bethe explicated the process of nuclear fusion by which stars generate their heat and light. In addition to Edward Pickering, Harvard College Observatory winners of the Bruce Medal include Harlow Shapley, Bart Bok, and Fred Whipple, who propounded the “dirty snowball” model of comet construction

…

Draper Medal, like the Bruce Medal, continues to acknowledge astronomers for lifelong accomplishments. Those researchers who have won both the Draper and the Bruce include Edward Pickering, George Ellery Hale, Arthur Stanley Eddington, Harlow Shapley, and Hans Bethe. No women have ever taken both prizes. In the years since Miss Cannon was

…

of the star Mizar reveal a doubled K line in the top image and a single K line in the bottom one—differences that led Edward Pickering to his 1887 discovery of the first spectroscopic binary. In order to photograph the stars of the Southern Hemisphere, Harvard established an auxiliary observatory, the

…

take her own plates of the southern stars. Harlow Shapley enjoyed the flexibility of the unique revolving desk-and-bookcase combination devised by his predecessor, Edward Pickering. Cecilia Payne traveled to the Harvard Observatory from Cambridge University in England, where she had been inspired by Arthur Stanley Eddington to devote herself to

…

, New York, for invaluable assistance with the other kind of computers. SOURCES CHAPTER ONE: Mrs. Draper’s Intent The letters between Anna Palmer Draper and Edward Pickering are held in the Harvard University Archives, along with all the other observatory correspondence, and are quoted here with permission. Pickering’s call for women

…

correspondence concerning the Boyden Station of the Harvard College Observatory is held in the Harvard University Archives. CHAPTER THREE: Miss Bruce’s Largesse Letters to Edward Pickering from Catherine Wolfe Bruce, as well as those from her sister Matilda, are held in the Harvard University Archives. The article by astronomer Simon Newcomb

…

the Chicago conference was published as “A Field for Woman’s Work in Astronomy” in 1893 in Astronomy and Astro-Physics. CHAPTER FOUR: Stella Nova Edward Pickering reported Mrs. Fleming’s first nova discovery, “A New Star in Norma,” in the pages of Astronomy and Astro-Physics. Pickering’s correspondence with Antonia

…

and can be read online at http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/3007384. President Edward B. Knobel’s comments pertaining to the presentation of Edward Pickering’s second gold medal were published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society in February 1901. CHAPTER SEVEN: Pickering’s “Harem” The correspondence between

…

Andrew Carnegie and Edward Pickering, also the letters exchanged by Louise Carnegie and Williamina Fleming, are held in the Harvard University Archives. CHAPTER EIGHT: Lingua Franca Herbert Hall Turner commented

…

“marvellous” achievements of Williamina Fleming in the obituary he wrote for her, which was published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1911. Edward Pickering’s diary of his trip to Pasadena to attend the 1910 meeting of the Solar Union is held in the Harvard University Archives, and was

…

to the Stars, published in 1969. He dedicated the book “To the memory of Henry Norris Russell.” Margaret Harwood’s letters to Annie Jump Cannon, Edward Pickering, and Harlow Shapley are preserved in the Harvard University Archives along with other materials pertaining to the observatory, but most of her private papers and

…

cometary and other discoveries, made by observers anywhere, and telegraphed to observatories everywhere. 1884 Results of first photometry study published in the Annals, vol. 14. Edward Pickering divides entire sky into forty-eight equal regions known as the Harvard Standard Regions. 1885 Bache Fund grant provides the 8-inch telescope required for

…

Anna Palmer Draper provides funding for photography of stellar spectra, with the aim of realizing the unfulfilled dream of her late husband, Dr. Henry Draper. Edward Pickering receives the gold medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in recognition of the Harvard Photometry. 1887 Harvard acquires the Boyden Fund to build a high

…

-altitude observatory. William Pickering joins the observatory staff Edward Pickering is named the Paine Professor of Practical Astronomy; Arthur Searle assumes the title of Phillips Professor. 1888 Antonia Maury joins the staff of female computers

…

observations in Peru, aided by his wife, Ruth E. Poulter Bailey. Catherine Wolfe Bruce gives $50,000 for construction of a 24-inch astrophotographic telescope Edward Pickering discovers the first spectroscopic binary; Antonia Maury finds the second one. 1890 “The Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra” is published in the Annals, vol. 27

…

Astronomy” for presentation at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago; discovers her first nova on plates from Arequipa Bruce telescope sees first light at Cambridge. 1895 Edward Pickering institutes the Harvard College Observatory Circular to describe news of the observatory, beginning with Williamina Fleming’s discovery of Nova Carinae (her second nova) from

…

the title page. 1898 National professional organization of astronomers, later named the Astronomical and Astrophysical Society of America, established at a meeting held at Harvard. Edward Pickering introduces Harvard College Observatory Bulletins to augment the telegraphic announcements with details sent by mail. 1899 Williamina Fleming given Harvard title as curator of astronomical

…

” in the Annals, vol. 55. Williamina Fleming publishes “A Photographic Study of Variable Stars” in the Annals, vol. 47 Margaret Harwood joins the staff. 1908 Edward Pickering publishes the Revised Harvard Photometry in the Annals, vols. 50 and 54. Solon Bailey compiles a whole-sky catalogue of 263 bright clusters and nebulae

…

in the Annals, vol. 60 Henrietta Leavitt publishes her discovery of “1777 Variables in the Magellanic Clouds” in the Annals, vol. 60 Edward Pickering receives the Catherine Wolfe Bruce Gold Medal. 1909 Solon Bailey reconnoiters potential new observatory sites in South Africa. 1910 Foreign astronomers attend meeting of the

…

Observers is founded by William Tyler Olcott, one of Pickering’s volunteer contributors. 1912 Harvard Bulletin switches from handwritten and mimeographed production to printed format. Edward Pickering and Annie Cannon demonstrate the brightness of B stars Henrietta Leavitt publishes her “period-luminosity relation. Margaret Harwood becomes first Astronomical Fellow of the Nantucket

…

Annals, vol. 76. 1918 First of nine volumes of the greatly expanded Henry Draper Catalogue is published in the Annals, beginning with vol. 91. 1919 Edward Pickering dies. Solon Bailey serves as interim director. 1920 Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis debate the scale of the universe. 1921 Harlow Shapley is named fifth

…

New York heiress who became an astronomy enthusiast in her later years, funded numerous research projects, journals, and instruments with the guidance of observatory director Edward Pickering, and also endowed a prestigious lifetime achievement award, the Bruce Medal. Leon Campbell (January 20, 1881–May 10, 1951) traced light curves of variable stars

…

Chandler’s telegraphic announcement code in 1906. George Ellery Hale (June 29, 1868–February 21, 1938), who spent a year as a young apprentice to Edward Pickering, later pursued solar spectroscopy. He established the Astrophysical Journal, and helped found both the American Astronomical Society and the International Astronomical Union, as well as

…

, and later served as Pickering Memorial Astronomer with the American Association of Variable Star Observers. Oliver Clinton Wendell (May 7, 1845–November 5, 1912) assisted Edward Pickering for more than thirty years of photometry studies, paying particular attention to the changing light of variable stars. Fred Lawrence Whipple (November 5, 1906–August

…

for artificial satellites and the Whipple shield to protect spacecraft from damage by meteors. Sarah Frances Whiting (August 23, 1847–September 12, 1927) learned from Edward Pickering how to set up a practical physics laboratory, and established one at Wellesley College, where she taught and inspired Annie Jump Cannon. Harvia Hastings Wilson

…

Coetana de Paiva Pereira Gardner (Mrs. John William Draper). Hermann Carl Vogel (1842–1907) of Germany independently discovered spectroscopic binaries at the same time as Edward Pickering. From his studies of spectra to gauge the motions of stars along the line of sight, Vogel showed that Algol and Spica each had an

…

Ursae Majoris, also known as Mizar, was split by telescope into two stars, Mizar A and B, photographed by George Bond in 1857. In 1889 Edward Pickering saw Mizar A itself as a pair—the first to be discovered by spectroscopy. Later, Mizar B also proved to be a binary pair. CHAPTER

…

Sun and Moon. The Sun is not twenty but fully four hundred times farther from Earth than the Moon. CHAPTER SIX: Mrs. Fleming’s Title Edward Pickering also wrote a contribution for the “Chest of 1900,” detailing his daily activities at the observatory as well as his leisure pursuits. In summers, he

…

Goodfellow sinking, 253 Rockefeller Foundation, 218 Rogers, Henry, 296 Rogers, William, 9, 274, 290 Royal Astronomical Society (Britain), 195, 199, 283, 293 medals awarded to Edward Pickering, 22–23, 100, 274, 276 and Miss Cannon, 156, 159–60, 183–84, 277 Mrs. Fleming’s election to, 118, 145, 276 Royal Observatory (Greenwich

AIQ: How People and Machines Are Smarter Together

by Nick Polson and James Scott · 14 May 2018 · 301pp · 85,126 words

, to take graduate-level courses and to volunteer at the Harvard College Observatory. Her outstanding abilities soon drew the notice of the observatory’s director, Edward C. Pickering, who asked Leavitt to join the “Harvard Computers,” a team of math prodigies—all women—hired to analyze data from telescopes. Long before a

…

PayPal personalization conditional probability and latent feature models and Netflix and Wald’s survivability recommendations for aircraft and See also recommender systems; suggestion engines philosophy Pickering, Edward C. politics prediction rules contraception and deep learning and evaluation of Google Translate and Great Andromeda Nebula and image recognition and massive data and massive

Day We Found the Universe

by Marcia Bartusiak · 6 Apr 2009 · 412pp · 122,952 words

Keeler died in San Francisco, after experiencing two strokes. The setback for astronomy, said his friend and colleague Campbell, was “incalculable.” Harvard College Observatory director Edward Pickering wrote that the “loss cannot be overestimated… There was no one who seemed to me to have a more brilliant future … or on whom we

…

star in the northern sky and accurately gauge its color and brightness. Presented with a sizable endowment for a program in spectroscopy, observatory director Edward C. Pickering resolved to photograph and classify the spectra of all the bright stars as well. The Peruvian observatory allowed Harvard to extend the reach and sweep

…

assistants can thus be employed, and the work done correspondingly increased for a given expenditure.” Williamina Fleming (standing) directs her “computers” while Harvard Observatory director Edward Pickering looks on (Harvard College Observatory) These women “computers,” as they were called, many with college degrees in science, were situated in two cozy workrooms, pleasantly

…

behaved in the same way as Leavitt's Cepheids. Shapley tried mightily to check with Leavitt on this question, writing several times to her boss, Edward Pickering, on whether she had detected fast variables in the Magellanic Clouds and found them to obey her rule. Pickering assured him that photographs were being

…

Shapley had come to believe he was the front-runner for the directorship of the Harvard College Observatory, one of astronomy's most prestigious positions. Edward Pickering had recently died, having established a monumental legacy, and the search for his replacement was actively under way. Though young and completely untested in managing

Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet

by Claire L. Evans · 6 Mar 2018 · 371pp · 93,570 words

on either side of the Atlantic, their formal titles weren’t accompanied by commensurate status or compensation. In the 1880s, for example, the astronomer Edward Charles Pickering hired only women to analyze and classify stellar data for his Harvard lab, including his own maid, Williamina Fleming. Although he would later champion the

…

that horrible struggle”: Toole, Ada, the Enchantress, 290. “her ideas are so modern”: B. V. Bowden, preface to Faster Than Thought, xi. the astronomer Edward Charles Pickering: The going legend here, although there is some evidence to the contrary, is that Pickering hired Fleming after growing frustrated with a group of male

…

, Naomi, 133, 208 Pearl, Amy, 162 Pearl Harbor attack, 27–29, 32 People’s Computer, 98, 119 Perlman, Radia, 123–28 Phiber Optik, 136, 187 Pickering, Edward Charles, 23 PicoSpan, 132, 135 Pierce, Julianne, 237 Plant, Sadie, 11, 21, 80, 238 PLATO (Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations), 178–81 Pleasant Company

Big Bang

by Simon Singh · 1 Jan 2004 · 492pp · 149,259 words

taken the first photograph of the Moon, bequeathed his personal fortune to Harvard in order to photograph and catalogue all the observable stars. This allowed Edward Pickering, who became director of the observatory in 1877, to initiate a relentless programme of celestial photography. The observatory would take half a million photographic plates

…

contribute to astronomy, a discipline that had largely excluded them in the past. Figure 43 The Harvard ‘computers’ at work, busy examining photographic plates while Edward Pickering and Williamina Fleming watch over them. On the back wall are two plots that show the oscillating brightness of stars. Although Williamina Fleming’s team

…

286-7, 287, 293, 294 Petreius, Johannes 40 Philolaus of Croton 22 photoelectric effect 107 photography 201-4,207, 247,374 Physical Review 319,361 Pickering, Edward 204, 205 Pigott, Edward 195-6,198,201 Pigott, Nathaniel 197 Pius XII, Pope 360-2,484 Planck, Max 75,115,123 planets 479; Copernicus

First Light: Switching on Stars at the Dawn of Time

by Emma Chapman · 23 Feb 2021 · 265pp · 79,944 words

referred to as ‘computers’. The cheap labour women provided allowed Williamina P. Fleming to get a job as an assistant to the Harvard astrophysicist Edward C. Pickering. Fleming evaluated stellar spectra and assigned them a letter according to the strength of the hydrogen absorption lines. They began by giving the stars

…

, here, here, here pair production here reionisation of hydrogen here, here, here, here, here, here spin-flip transitions here, here see also light photosynthesis here Pickering, Edward C. here pigeons here, here Pink Floyd here Planck telescope here, here, here, here, here planetary nebulae here plasma here plutonium here Poe, Edgar Allan

The Interstellar Age: Inside the Forty-Year Voyager Mission

by Jim Bell · 24 Feb 2015 · 310pp · 89,653 words

sixteenth-century Kerala school of mathematics in India (influencing, in their writings, another loner astronomer in Poland, the previously mentioned Nicolaus Copernicus). Or Harvard astronomer Edward Pickering’s early-twentieth-century group of mostly female “computers” toiling through enormous telescopic data sets to work out the modern basis for the classification of

…

, 11 Peale, Stan, 115, 119–120 Phoenex, 99 Photographs. See also Image processing of Earth, 225–231, 236–239 Golden Record contents, 84–93, 94 Pickering, Edward, 168 Pioneer program, 51, 73–77, 103, 109, 120–121, 279 Pioneer 10, 23, 73, 249, 250, 278–279 Pioneer 11, 23, 73, 135–136

The Milky Way: An Autobiography of Our Galaxy

by Moiya McTier · 14 Aug 2022 · 194pp · 63,798 words

, no. S256 (July 2008): 461–72, https://doi.org/10.1017/s1743921308028871. 6Henrietta Swan Leavitt was just one of at least eighty women employed by Edward Pickering between 1877 and 1919. These brilliant women analyzed vast amounts of stellar data but were still disrespected by many contemporaries who called them “Pickering’s

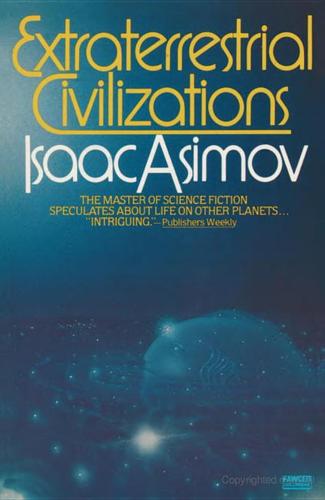

Extraterrestrial Civilizations

by Isaac Asimov · 2 Jan 1979 · 330pp · 99,226 words

actual spreading apart into two lines. The first such “spectroscopic binary” to be discovered was Mizar, and it was in 1889 that the American astronomer Edward Charles Pickering (1846–1919) detected the doubling of its spectral lines. Actually, the component stars of Mizar are separated by 164 million kilometers (102 million miles