The New Geography of Jobs

by

Enrico Moretti

Published 21 May 2012

Poverty Traps and Sexy Cities 7. The New “Human Capital Century” Acknowledgments Notes References Index Footnotes Copyright © 2012 by Enrico Moretti All rights reserved For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003. www.hmhbooks.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moretti, Enrico. The new geography of jobs / Enrico Moretti. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-547-75011-8 1. Labor market—United States. 2. Economic development—United States. 3.

…

NBER Working Paper 16096. National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2010. Calvey, Mark. “Bay Area Startups Court Cash-strapped, Creditworthy.” San Francisco Business Times, February 10, 2012. Card, David, Kevin F. Hallock, and Enrico Moretti. “The Geography of Giving: The Effect of Corporate Headquarters on Local Charities.” Journal of Public Economics 94, no. 3–4 (2010): 222–34. Card, David, and Enrico Moretti. “Does Voting Technology Affect Election Outcomes? Touch-screen Voting and the 2004 Presidential Elections.” Review of Economics and Statistics 89, no. 4 (November 2007): 660–73. Carrell, Scott, Mark Hoekstra, and James E.

…

The Race Between Education and Technology. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap/Harvard University Press, 2008. Greenstone, Michael, Rick Hornbeck, and Enrico Moretti. “Identifying Agglomeration Spillovers: Evidence from Winners and Losers of Large Plant Openings.” Journal of Political Economy 118, no. 3 (2010): 536–98. Greenstone, Michael, and Adam Looney. “Where Is the Best Place to Invest $102,000—In Stocks, Bonds, or a College Degree?” Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution, June 2011. Greenstone, Michael, and Enrico Moretti. “Bidding for Industrial Plants: Does Winning a ‘Million Dollar Plant’ Increase Welfare?” NBER Working Paper 9844.

Good Economics for Hard Times: Better Answers to Our Biggest Problems

by

Abhijit V. Banerjee

and

Esther Duflo

Published 12 Nov 2019

_V516043504_.pdf accessed June 14, 2019. 38 Adam B. Jaffe, Manuel Trajtenberg, and Rebecca Henderson, “Geographic Localization of Knowledge Spillovers as Evidenced by Patent Citations,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 108, no. 3 (1993): 577–98, https://doi.org/10.2307/2118401. 39 Enrico Moretti. The New Geography of Jobs. (Boston: Mariner Books, 2012). 40 Michael Greenstone, Richard Hornbeck, and Enrico Moretti, “Identifying Agglomeration Spillovers: Evidence from Winners and Losers of Large Plant Openings,” Journal of Political Economy 118, no. 3 (June 2010): 536–98, https://doi.org/10.1086/653714. 41 Of course, the question being asked in New York was not about the size of the gains (everybody agreed there would be some) but why Amazon was allowed to keep so much of it for themselves.

…

This will create additional growth of 20 percent of 2 percent, or 0.4 percent, over the following decade and so on. It is evident the additional rounds of growth are small to start with and get smaller pretty fast. 45 Patrick Kline and Enrico Moretti, “Local Economic Development, Agglomeration Economies and the Big Push: 100 Years of Evidence from the Tennessee Valley Authority,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 129, no. 1 (2014): 275–331, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjt034. 46 Enrico Moretti, “Are Cities the New Growth Escalator?,” in The Urban Imperative: Towards Competitive Cities, ed. Edward Glaeser and Abha Joshi-Ghani (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2015), 116–48. 47 Peter Ellis and Mark Roberts, Leveraging Urbanization in South Asia: Managing Spatial Transformation for Prosperity and Livability, South Asia Development Matters (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0662-9.

…

US politicians are wary of subsidizing specific sectors (since others would feel slighted and would lobby for their own protection), which is probably partly the reason why TAA has remained such a small program. Economists have also traditionally been unwilling to embrace place-based policies (“help people, not places” as the slogan goes). Enrico Moretti, one of the few economists who has actually studied such policies, actively dislikes them. For him, channeling public funds into regions doing poorly is throwing good money after bad. Blighted towns are meant to shrink while others take their place. It is the way of history. What public policy needs to do is to help people move to the places of the future.56 This analysis seems to give too little weight to the facts on the ground.

The Captured Economy: How the Powerful Enrich Themselves, Slow Down Growth, and Increase Inequality

by

Brink Lindsey

Published 12 Oct 2017

Gabe, “Productivity and the Density of Human Capital,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report no. 440, March 2010 (revised September 2011), http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr440.pdf. 17.See Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs, pp. 94–95. 18.Enrico Moretti, “Estimating the Social Return to Higher Education: Evidence from Longitudinal and Repeated Cross-Sectional Data,” Journal of Econometrics 121 (2004): 175–212. 19.Ryan Avent, The Gated City (Amazon Digital Services, Kindle Edition, 2011). 20.See Edward L. Glaeser and Kristina Tobio, “The Rise of the Sunbelt,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper no. 13071, April 2007, http://www.nber.org/papers/w13071.pdf. 21.See Ganong and Shoag, “Why Has Regional Convergence in the U.S. Declined?” 22.Enrico Moretti and Chiang-Tai Hsieh, “Why Do Cities Matter?

…

Since the 1970s, college graduates have increasingly tended to congregate in particular urban areas—namely, those that started out with initially high shares of college grads. In other words, education levels in American cities have diverged over time. The smart cities get smarter while other cities fall farther and farther behind. To illustrate this phenomenon, Enrico Moretti of the University of California, Berkeley, cites the examples of Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Seattle, Washington. As it just so happens, the former metro area is where Microsoft was founded in 1975, while the latter has been the company’s headquarters since 1979 (when Bill Gates and Paul Allen made the fateful decision to move back to their hometown).

…

In the top five, college grads earn an average annual salary of $87,689 as of 2006–08, 61 percent more than the average salary of $54,518 earned by college grads in the bottom five. By comparison, high school grads in the top five make $71,483 a year on average, a whopping 137 percent more than their counterparts in the bottom five.17 According to calculations by Enrico Moretti, a percentage point increase in a city’s share of college-educated workers boosts the earning of college grads in that city by 0.4 percent and lifts the earnings of high school grads by 1.6 percent, or four times as much.18 America’s innovative, high-productivity human capital hubs should be experiencing rapid population growth as both highly skilled and less-skilled workers flock there in search of higher pay and wider opportunities.

Arbitrary Lines: How Zoning Broke the American City and How to Fix It

by

M. Nolan Gray

Published 20 Jun 2022

Residents, in turn, bid up the price of land near these job centers, driving up adjacent densities. These forces explain why cities across the world—despite a dizzying array of local conditions, from Barcelona to Bangkok to Boston—exhibit a pattern of density peaking in a “central business district” and gradually declining outward. As the urban economist Enrico Moretti notes, all of this also shows up in income data: as city populations grow, incomes—a useful proxy for productivity—also grow. Average wages in cities with at least a million workers are roughly a third higher than in cities with fewer than 250,000 workers.9 This divergence has only strengthened since 1970 and is likely to continue in the years to come.

…

Why move to a more productive city if higher housing costs will eat up all of your additional income, and then some? How Much Poorer Are We? As a result of this strange inversion in American mobility, we are all poorer. But how much poorer? By misallocating so much of the US labor market, economists Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti put the annual loss in wages associated with zoning at around $1.6 trillion each year.23 Hsieh and Moretti estimate that these policies reduced economic growth between 1964 and 2009 by 36 percent. They further estimate that relaxing zoning in New York City, San Francisco, and San Jose alone would have raised aggregate gross domestic product in 2009 by 9 percent.

…

This degree of specialization—and the better door handles it produces—would not be possible without a truly massive labor market. 7. Alain Bertaud, Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018), chap. 2. 8. Recall from the appendix that land prices drive density in that high land prices incentivize the efficient use of land through increased density. 9. Enrico Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs (Boston: Mariner Books, 2013), 128. 10. While clusters may rebuild themselves in areas where housing is cheaper—be it tech in Austin and Denver or finance in Dallas and Charlotte—these clusters take decades to emerge, with a lot of potential productivity and innovation lost in the interim.

The End of Work: Why Your Passion Can Become Your Job

by

John Tamny

Published 6 May 2018

It is only logical, then, that technological innovation drives enormous wealth creation as more and longer-living people interact with each other. And as wealth grows, so does demand for goods and services of all kinds that have little direct connection with technology. In short, the wealth that springs from technology is what Professor Enrico Moretti of the University of California at Berkeley calls a “jobs multiplier.” In The New Geography of Jobs (2012) Moretti asserts that “for each new high-tech job in a city, five additional jobs are ultimately created out of the high-tech sector.”14 As people prosper in tech, their need for other services grows—personal trainers, yoga instructors, investment bankers, lawyers, restaurants, wine. . .Since the average American spends 14 percent of his income on food and beverages, where there’s abundant wealth there’s the chance for the Wolfgang Puck or the Danny Meyer of tomorrow to pursue his passion alongside technologists pursuing theirs.15 A rising tide in technological centers such as San Francisco, San Jose, Austin, and Boston surely enhances opportunity for the majority of us not interested in, or intimidated by, technology.

…

Chapter Nine: Why We Need People with Money to Burn 1.Warren Brookes, The Economy in Mind (New York: Universe Books, 1982), p. 77. 2.Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 407. 3.Ibid., 157. 4.David McCullough, The Wright Brothers (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015), 34. 5.Ibid., 108. 6.Konstantin Kakaes, “New Directions,” Wall Street Journal, June 25–26, 2016. 7.Isaacson, Steve Jobs, 339. 8.Dawn Kawamoto, Ben Heskett, and Mike Ricciuti, “Microsoft to invest $150 million in Apple,” CNET, August 6, 1997. 9.Alexis Tsotsis, “Uber Gets $32 Million From Menlo Ventures, Jeff Bezos, and Goldman Sachs,” Tech Crunch, December 7, 2011. 10.Source: Forbes, http://www.forbes.com/profile/jeff-bezos/. 11.Peter Thiel with Blake Masters, Zero to One (New York: Crown Business, 2014), 84. 12.Noam Cohen, “Technology’s Trumpian Visions,” New York Times, July 27, 2016. 13.Enrico Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2012), 37. 14.Ibid., 13. 15.Ibid., 168. 16.Ibid., 52. 17.Ibid., 60. 18.Ibid., 62. 19.Michael Freeman, ESPN: The Uncensored History (Lanham, Md.: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2000), 58. 20.Ibid., 59. 21.Ibid. 22.Ibid., 7. 23.Ibid., 77. 24.Thomas Kessner, Capital City: New York City and the Men Behind Its Rise to Economic Dominance, 1860–1900 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003). 25.T.

…

Knopf, 2009), 13. 3.Henry Hazlitt, Economics in One Lesson (New York: Three Rivers Press, 1979), 28. 4.Source: Forbes, Highest Paid Athletes, http://www.forbes.com/athletes/list/#tab:overall. 5.Source: Forbes, Highest Paid Celebrities, http://www.forbes.com/celebrities/list/#tab:overall. 6.Source: Forbes, The World’s Billionaires, http://www.forbes.com/billionaires/list/. 7.Joel Trammell, The CEO Tightrope (Austin: Greenleaf Book Group Press, 2014), 79. 8.Mat Smith, “Meet the laundry-folding washing machine of our lazy-ass future,” Engadget, October 7, 2015. 9.Enrico Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012), 36. 10.Eric John Abrahamson, Building Home: Howard F. Ahmanson and the Politics of the American Dream (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 29. 11.Robyn Meredith, The Elephant and the Dragon (New York: Norton, 2007), 59. 12.Hazlitt, Economics in One Lesson, 188. 13.Ibid., 188. 14.Ibid.

The Metropolitan Revolution: How Cities and Metros Are Fixing Our Broken Politics and Fragile Economy

by

Bruce Katz

and

Jennifer Bradley

Published 10 Jun 2013

Yet for all its benefits, the locally focused economy does not have the same impact on economic growth that selling goods and services outside the boundaries of the metropolitan area does. Jobs in export sectors have a high multiplier effect, meaning that they create more additional jobs than those that serve purely local markets. Jobs in the high-tech sector have an especially strong multiplier effect. As the urban economist Enrico Moretti has found, each new high-tech job in a metropolitan area leads to, over the long term, two additional professional and three additional nonprofessional jobs.49 According to Moretti, “Attracting a new scientist, software engineer, or mathematician to a city increases the demand for local services.

…

“We can’t just sit here and let Silicon Valley beat us,” Mayor Bloomberg told a gathering of tech entrepreneurs in October 2011, as the responses to the request for proposals were coming in.60 But New York was not, in fact, seeking to transplant an entire industry or create a Silicon Valley East. The NYCEDC and the mayor’s office were clear that Applied Sciences NYC would be connected to the particular existing and emerging strengths of the city. As Enrico Moretti points out in The New Geography of Jobs, “Universities are most effective at shaping a local economy when they are part of a larger ecosystem of innovative activity.”61 Before launching a major economic development initiative like this, places need a sense of what that ecosystem is. In 2009 New York City had assets that were underperforming but moving in the right direction.

…

For example, areas with higher poverty rates experience, on average, slower per capita income growth rates than low-poverty areas.”48 The Nobel Prize–winning economist Joseph Stiglitz has written, “The bottom line that higher inequality is associated with lower growth— controlling for all other relevant factors—has been verified by looking at a range of countries and looking over longer periods of time.”49 The counterproposition, that a more skilled workforce accelerates economic growth, is found in (among other works) Enrico Moretti’s book The New Geography of Jobs, which came out in 2012. Moretti argues that metropolitan areas with a high percentage of well-educated workers also tend to attract more highly educated people—conversely, those with low levels of well-educated workers tend to bleed highly educated people. Moretti describes three Americas: At one extreme are the brain hubs—cities [by which Moretti means metros] with a well-educated labor force and a strong innovation sector.

Trees on Mars: Our Obsession With the Future

by

Hal Niedzviecki

Published 15 Mar 2015

Everything is about “visionary product insight.” If the new media monoliths of the twenty-first century can be said to have put forth one cohesive vision, it’s this: own the future, or the future will own you. Or to put it another way: own the people who will shape the future, or they might end up owning you. Economist Enrico Moretti writes in his book The New Geography of Jobs: “Globalization and technological progress have turned many physical goods into cheap commodities but have raised the economic return on human capital and innovation. For the first time in history, the factor that is scarce is not physical capital but creativity.”23 It’s not strength we admire and seek to emulate in order to be seen as successful in our society.

…

“Poverty is no longer an issue of ‘them,’ it’s an issue of ‘us,’” says Mark Rank, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis who worked on the numbers for the AP article. “Only when poverty is thought of as a mainstream event, rather than a fringe experience . . . can we really begin to build broader support for programs that lift people in need.”17 In his book, The New Geography of Jobs, economist Enrico Moretti states: “For the first time in recent American history, the average worker has not experienced an improvement in standard of living compared to the previous generation. In fact he is worse off by almost every measure. On top of this, income inequality is widening. Uncertainty about the future is now endemic.”18 In our era of chasing future, everything is in flux and stability seems to be the most elusive commodity of all.

…

We hold that the past holds us back, that institutions are slow and in the way; that, in fact, the best institutions are the ones laying the groundwork for their own obsolescence, replaced by a fully empowered populace of individuals and corporate proxies who make change faster and better than any organization, community, or government ever could. We assert unequivocally that only change in the form of technological innovation can keep us happy, healthy and, most important, wealthy. Writes the sober economist Enrico Moretti: “Innovation is the engine that has enabled Western economies to grow at unprecedented speed ever since the onset of the industrial revolution. In essence, our material well-being hinges on the continuous creation of new ideas, new technologies, and new products.”25 Imbued with the Toffler method, we can then assume that once everyone is educated in the relentless, rootless, constantly changing tao of future, innovation will continue apace, we’ll all be better off and our anxiety will be finally dispelled.

Restarting the Future: How to Fix the Intangible Economy

by

Jonathan Haskel

and

Stian Westlake

Published 4 Apr 2022

It involves differences in openness, in education, in rootedness, and in respect. It has a strong geographical component, and it is sometimes orthogonal to economic inequality. Plenty of underpaid, indebted college graduates might find themselves described as liberal elites, while the left-behinds include comfortable retirees with homes and pensions. Economist Enrico Moretti called the geographical dimension of this divide the “great divergence,” presenting evidence on the differences between prosperous and left-behind US cities on everything from graduate rates and graduate salaries to divorce and mortality rates.9 Will Jennings and Gerry Stoker, two British political scientists, observed a divide emerging in the early 2010s between what they called “the Two Englands”—one cosmopolitan and outward-facing, the other illiberal and nationalistic.10 A similar divide in the United States became the dominant political fact of the late 2010s, delivering the votes that put Donald Trump in the White House, removed the United Kingdom from the European Union, and launched the careers of populist politicians around the world.

…

Finally, we ask how to make the most of the changes some workers have seen as a result of COVID-19-enforced remote working. The Rise of Intangibles and the Rise of Cities The economic rise of certain cities in the past thirty years has been remarkable. During this “great divergence,” to borrow a phrase coined by the economist Enrico Moretti, the most dynamic places have pulled ahead of the least dynamic places in many ways, most notably in building a cluster of educated workers. We would expect this outcome in a world where intangible capital is becoming more important. When the economists Gilles Duranton and Diego Puga analysed “agglomeration effects”—the link between city size and economic growth—they identified three causes, which they called matching effects, learning effects, and shared facilities.5 Being in a big city makes it easier to match employees to jobs, customers to services, and partners (business, social, or romantic) with one another.

…

But if the spillovers from a big employer are what is making a place rich, then the place is vulnerable to gambler’s ruin. Not every town can have a world-leading university. One consequence of the growing divide between places is political dysfunction. In his book The New Geography of Jobs, Enrico Moretti reports disengagement with the political process, but shortly after his book’s publication, a wave of political entrepreneurs around the world provided disengaged voters with something that appealed to them: populism, often combined with promises of bringing back a social and economic world that had been lost.15 We might hope that technology will rescue us from this double bind of rich-but-strangled cities and decaying, disaffected towns and that the COVID-19 home-working revolution might accelerate this change.

The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization

by

Richard Baldwin

Published 14 Nov 2016

Cities also optimize the matching between workers and firms and between suppliers and customers. In this sense, cities become skill-clusters—or “brain hubs” as Enrico Moretti calls them. The link between the success of a city and human capital is a close one. One of the most persistent predictors of urban growth over the last century is the skill level of a city. The reason people gather even as manufacturing scatters is that high-skill jobs in the tradable sector tend to be subject to more face-to-face demands as well as agglomeration economies (discussed in Chapter 6). In writing about the United States, Enrico Moretti explains the agglomeration forces as follows: “More than traditional industries, the knowledge economy has an inherent tendency towards geographical agglomeration.… The success of a city fosters more success as communities that can attract skilled workers and goods jobs tend to attract even more.

…

Gallen and I pointed out in our 2012 paper for the British government on value creation and trade in manufacturing.4 The main point is that wise governments should distinguish carefully between factors of production that are internationally mobile and those that are internationally immobile. Both matter. Both contribute to national income. But, as Enrico Moretti points out in his must-read book The New Geography of Jobs, good jobs created in G7 nations have a local multiplier effect, which good jobs created by G7 firms abroad do not.5 A Two-Dimensional Evaluation The point that some forms of capital may escape abroad suggests that an important consideration for policy should be the “stickiness” of the various productive factors.

…

Richard Baldwin and Simon Evenett, “Value Creation and Trade in Twenty-First Century Manufacturing: What Policies for U.K. Manufacturing?” in The U.K. in a Global World: How Can the U.K. Focus on Steps in Global Value Chains That Really Add Value? ed. David Greenaway (London: Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2012). 5. Enrico Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012). 6. I first made these points in a 2012 paper: Richard Baldwin, “WTO 2.0: Global Governance of Supply-Chain Trade,” Centre for Economic Policy Research, Policy Insight No. 64, December 2012, http://www.cepr.org/sites/default/files/policy_insights/PolicyInsight64.pdf. 9.

The Complacent Class: The Self-Defeating Quest for the American Dream

by

Tyler Cowen

Published 27 Feb 2017

In spite of the people who are doing great, the data indicate that the upward mobility of Americans, in terms of income and education, which increased through about 1980, has since held steady. Partly this is because the economy is more ossified, more controlled, and growing at lower rates. It’s also because it is much more expensive to move into a dynamic city, an option that gave many a way of making economic progress in times past. Two researchers, Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, estimate that if it were cheaper to move into America’s higher-productivity cities, the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) would be 9.5 percent higher due to the gains from better jobs. Yet no one thinks that the building restrictions of, say, San Francisco or New York will be relaxed much anytime soon.

…

In New York City, that hasn’t been the case for a long time, so a lot of middle-class families in the city have to think about sending their kids to private schools, which can run tens of thousands of dollars a year per kid. If it were cheaper to move into major American cities, the country’s economy would be stronger and many more Americans would have an easier path toward a higher salary and a brighter future. Two aforementioned researchers, Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, set out to measure just how big a problem this has been. They noticed that within the United States, the dispersion of worker productivity across different cities has gone up. For instance, New York, San Francisco, and San Jose have become especially high-productivity cities, compared to, say, Brownsville, Texas; the size of these gaps has been growing over time.

…

Highway Loss Data Institute. “Evaluation of Changes in Teenage Driver Exposure.” Bulletin Bulletin 30, no. 17 (September 2013). Hilger, Nathaniel G. “The Great Escape: Intergenerational Mobility since 1940.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 21217, May 2015. Hsieh, Chang-Tai, and Enrico Moretti. “Why Do Cities Matter? Local Growth and Aggregate Growth.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 21154, May 2015. Hudson, David L. Jr. “Freedom of Assembly Was Crucial to the Civil Rights Movement.” In Robert Winters, ed., Freedom of Assembly and Petition, 114–119. Farmington Hills, MI: 2006.

The Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of Automation

by

Carl Benedikt Frey

Published 17 Jun 2019

One reason why industrial cities like Detroit began to decline before the age of automation, when manufacturing employment was still expanding, is that production began to move away from the Great Lakes to right-to-work states in the Sunbelt, where union security agreements between companies and labor unions are prohibited.29 Such locational freedom, however, may have reduced the desire to transport the smart people and ideas that have become so valuable in the higher-tech economy. And indeed, that is what has happened. In The New Geography of Jobs, the economist Enrico Moretti tells an intriguing story of two places in California: Menlo Park and Visalia. The story begins in 1969, with a young engineer turning down a job offer at Hewlett-Packard in Menlo Park (in the heart of Silicon Valley) to move to the midsize town of Visalia, three hours’ drive away. At the time, many professionals were leaving cities for smaller communities, which were considered better places for family life.

…

While symbolic analysts are still highly mobile, the unskilled have become less likely to migrate since the dawn of the computer revolution (see chapter 10). One reason might be financial. Even if skilled cities provide better employment opportunities, moving is an investment that requires liquidity up front. Thus, as Enrico Moretti has convincingly argued, there is a case for subsidizing relocation.49 Mobility vouchers could pay for themselves by shifting the unemployed into paid employment elsewhere, while serving to equalize incomes across space. Some will argue that mobility vouchers might serve to accelerate the exodus from communities in decline, leaving parts of America in an even more dire state, but even those who stayed put would likely benefit in terms of having a better chance of finding a job.

…

According to the O-ring production function of Michael Kremer, an improvement in one task in the production of something makes the other tasks more valuable (1993, “The O-Ring Theory of Economic Development,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 108 [3]: 551–75). 20. Levy and Murnane, 2004, The New Division of Labor, 13–14. 21. R. Reich, 1991, The Work of Nations: Preparing Ourselves for Twenty-First Century Capitalism (New York: Knopf). 22. E. L. Glaeser, 2013, review of The New Geography of Jobs, by Enrico Moretti, Journal of Economic Literature 51 (3): 827. 23. H. Moravec, 1988, Mind Children: The Future of Robot and Human Intelligence (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 15. 24. The share of labor hours in service occupations grew by 30 percent between 1980 and 2005. In the three decades before the computer revolution of the 1980s, in contrast, that share had been flat or declining (D.

The Logic of Life: The Rational Economics of an Irrational World

by

Tim Harford

Published 1 Jan 2008

Lines of irritable shoppers stretch back to the cheese counter while overworked staff point their scanners at shrink-wrapped junk food just as fast as they can. We don’t all find it easy to spare a smile for these underappreciated citizens, but there is now one more reason to give checkout staff all our sympathy: They are guinea pigs in an economic experiment. The economists in question, Alexandre Mas and Enrico Moretti, figured out that by sweet-talking the bosses of a supermarket chain, they could get access to every detail about the productivity of the chain’s cashiers. Using the computerized records from the stores’ scanners, they could track every “bleep,” every transaction, for 370 cashiers in six stores for two years.

…

They include Robert Axtell, Gary Becker, Stefano Bertozzi, Marianne Bertrand, Darse Billings, Simon Burgess, Bryan Caplan, Philip Cook, Frank Chaloupka, Kerwin Kofi Charles, Andre Chiappori, Gregory Clark, Daniel Dorling, Lena Edlund, Paula England, Marco Francesconi, Roland Fryer, Paul Gertler, Ed Glaeser, Claudia Goldin, Joe Gyourko, Daniel Hamermesh, George Horwich, Adam Jaffe, John Kagel, Matthew Kahn, Michael Kell, Mark Kleiman, Jeff Kling, Alan Krueger, David Laibson, Steven Landsburg, Steven Levitt, John List, Glenn Loury, Rob MacCoun, Enrico Moretti, Sendhil Mullainathan, Victoria Prowse, Daniel Read, Peter Riach, Jeffrey Sachs, Saskia Sassen, Thomas Schelling, Philip A. Stevens, Thomas Stratmann, Jake Vigdor, Yoram Weiss, Justin Wolfers, Peyton Young, and Jonathan Zenilman. Equally talented and equally generous with their expertise or comments were Lee Aitken, Sam Bodanis, Dominic Camus, Anne Currell, Stephen Dubner, Chris “Jesus” Ferguson, Patri Friedman, Mark Henstridge, Diana Jackson, Howard Lederer, Philippe Legrain, Seamus McCauley, Giuliana Molinari, Dave Morris, Frazer Payne, William Poundstone, Greg Raymer, Romesh Vaitilingam, and David Warsh.

…

The Safelite case is unusual: Lazear, “Performance Pay and Productivity,” p. 1359, based on National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, available at: ideas.repec.org/a/aea/aecrev/v90y2000i5p1346-1361.html. Even when performance: The most famous take on this is Steven Kerr, “On the Folly of Rewarding A, While Hoping for B,” Academy of Management Journal 18, no. 4(December 1975): 769–83. The economists in question: Alexandre Mas and Enrico Moretti, “Peers at Work,” NBER Working Paper 12508, September 2006, www.nber.org/papers/w12508. The economists who spotted: Edward Lazear and Sherwin Rosen, “Rank Order Tournaments as Optimum Labor Contracts,” Journal of Political Economy 89, no. 5(1981). Also Lazear, Personnel Economics for Managers.

The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class?and What We Can Do About It

by

Richard Florida

Published 9 May 2016

Ryan Avent, “The Parasitic City,” The Economist, June 3, 2013, www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2013/06/london-house-prices; Noah Smith, “Piketty’s Three Big Mistakes,” Bloomberg View, March 27, 2015, www.bloombergview.com/articles/2015-03-27/piketty-s-three-big-mistakes-in-inequality-analysis. Emphasis is from the original. 23. On the original Luddites, see Kirkpatrick Sale, Rebels Against the Future: The Luddites and Their War on the Industrial Revolution: Lessons for the Computer (Boston: Addison-Wesley, 1995). 24. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, “Why Do Cities Matter? Local Growth and Aggregate Growth,” NBER Working Paper no. 21154, National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2015. Economists Jason Furman, a former chairman of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers, and Peter Orszag, a former director of the Office of Management and Budget, noted that “zoning regulations are best interpreted as real estate market supply constraints.

…

Freemark’s analysis charted population change in America’s one hundred largest cities, comparing the change in overall population to the change in the built-up areas of those cities (areas with a population density of 4,000 people per square mile or more), with central areas in and around the urban core defined as those within 1.5 to 3 miles of city hall. 27. See Enrico Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012). 28. Richard Florida, “Cost of Living Is Really All About Housing,” CityLab, July 21, 2014, www.citylab.com/housing/2014/07/cost-of-living-is-really-all-about-housing/373128; Richard Florida, “The U.S. Cities with the Most Leftover to Spend… After Paying for Housing,” CityLab, December 23, 2011, www.citylab.com/housing/2011/12/us-cities-with-most-spend-after-paying-housing/778. 29.

…

O’Donnell, Henry George and the Crisis of Inequality (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015); “Why Henry George Had a Point,” The Economist, April 1, 2015, www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2015/04/land-value-tax. 11. David Schleicher, “City Unplanning,” Yale Law Journal 122, no. 7 (May 2013): 1670–1737. 12. Enrico Moretti and Chang-Tai Hsieh, “Why Do Cities Matter? Local Growth and Aggregate Growth,” April 2015, http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/chang-tai.hsieh/research/growth.pdf. 13. Richard Florida, “The Mega-Regions of North America,” Martin Prosperity Institute, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto, March 11, 2014, http://martinprosperity.org/content/the-mega-regions-of-north-america. 14.

Dream Hoarders: How the American Upper Middle Class Is Leaving Everyone Else in the Dust, Why That Is a Problem, and What to Do About It

by

Richard V. Reeves

Published 22 May 2017

“The segregation of the rich—which is growing rapidly in U.S. metropolitan areas,” write UCLA economists Michael Lens and Paavo Monkkonen, “results in the hoarding of resources, amenities, and disproportionate political power.”11 Nineteen out of twenty residents of the largest fifty U.S. cities now live in a jurisdiction with some form of zoning. The increase in land-use regulations has blunted economic growth by making it harder for people to move to more prosperous areas and by crowding out more productive spending and innovation.12 Work by Enrico Moretti and Chang-Tai Hsieh suggests that the U.S. economy would be 10 percent bigger if three cities (San Francisco, San Jose, and New York) had the zoning regulations of the median American city.13 Zoning has not only damaged economic growth. It has also exacerbated economic inequality, according to Jason Furman, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers from 2013 to 2017: While land use regulations sometimes serve reasonable and legitimate purposes, they can also give extra-normal returns to entrenched interests at the expense of everyone else.… Zoning regulations and other local barriers to housing development [can] allow a small number of individuals to capture the economic benefits of living in a community, thus limiting diversity and mobility.14 You know who he is talking about, right?

…

Journal of the American Planning Association 82, no. 1 (December 2015): pp. 6–21. 12. Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag, “Why Has Regional Income Convergence Declined?” Hutchins Center Working Paper 21 (Brookings, July 2016) (www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/wp21_ganong-shoag_final.pdf). 13. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, “Why Do Cities Matter? Local Growth and Aggregate Growth,” Working Paper, May 2015 (http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/chang-tai.hsieh/research/growth.pdf). 14. Jason Furman, “Barriers to Shared Growth: The Case of Land Use Regulation and Economic Rents,” remarks delivered to the Urban Institute, The White House, November 20, 2015 (www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/page/files/20151120_barriers_shared_growth_land_use_regulation_and_economic_rents.pdf). 15.

The New Class War: Saving Democracy From the Metropolitan Elite

by

Michael Lind

Published 20 Feb 2020

In addition to telling working-class citizens they need to learn to code, the purveyors of the conventional wisdom sometimes tell them they need to move to the San Francisco Bay Area or other high-tech hubs where many software coders are found. Influenced by “Why Do Cities Matter?”—a 2015 study by the economists Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti—many business journalists and pundits have argued that the US could be more productive if land-use restrictions allowed more workers to move to cities such as San Francisco, San Jose, New York, Boston, and Seattle. The grain of truth in this notion is that agglomeration effects help certain cities dominate particular industries and professions.

…

Kristal, “Good Times, Bad Times: Postwar Labor’s Share of Income in Capitalist Democracies,” American Sociological Review 75, no. 5, October 2010, pp. 729–63, cited in Andrew Sayer, Why We Can’t Afford the Rich (Chicago: Policy Press, 2016), pp. 187–88. 6. J. Peters, “The Rise of Finance and the Decline of Organized Labor in the Advanced Capitalist Countries,” New Political Economy 16, no. 1, p. 93, cited in Sayer, Why We Can’t Afford the Rich, pp. 187–88. 7. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, “Why Do Cities Matter? Local Growth and Aggregate Growth,” Chicago Unbound: Kreisman Working Paper Series in Housing Law and Policy, 2015. 8. Shirin Ghaffary, “Many in Silicon Valley Support Universal Basic Income. Now the California Democratic Party Does, Too,” Vox, March 8, 2018; Candice Norwood, “Silicon Valley Is Helping Cities Test a Radical Anti-Poverty Idea,” Governing, July 16, 2018. 9.

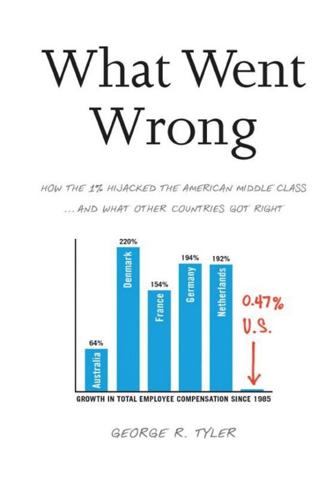

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by

George R. Tyler

Published 15 Jul 2013

It works this way: managers are rewarded for spiking share values in the current reporting quarter, affording them the opportunity to cash out options. And nothing spikes earnings per share better than a merger that dramatically enhances revenues. But what happens to shareholders, particularly those who have adopted the Wall Street mantra of “buy and hold?” Economists Ulrike Malmendier, Enrico Moretti, and Florian Peters of the University of California, Berkeley, examined all contested US mergers between 1985 and 2009 where at least two suitors vied. Published in April 2012 by the National Bureau of Economic Research, their analysis examined market evaluations of the successful suitors (acquirors) and losing bidders before and after mergers.

…

Eduardo Porter, “The Promise of Today’s Factory Jobs,” New York Times, April 4, 2012. In recent decades, harm from the sharp deterioration in the American manufacturing trade balance has been modulated by the expansion of good jobs in services. A number of these jobs pay better than factory work and are in what economists like Enrico Moretti at the University of California, Berkeley refer to as the innovation industry. These are service firms designing or managing software, medical R&D, telecom applications, and the like. New jobs in vibrant firms such as Facebook have a muscular multiplier profile similar to manufacturing. Moretti has concluded, for example, that each innovation industry job creates five others, including two that are highly paid professional slots.35 It also presumably means that firms such as Apple that shift jobs back to America would generate hundreds of thousands of highly valued jobs in addition to those directly onshored.

…

Kranton, Identity Economics, 58–59. 70 Louis Uchitelle, “Revising a Boardroom Legacy,” New York Times, Sept. 28, 2007. 71 W. G. Sanders and D. C. Hambrick, “Swinging for the Fences: The Effects of CEO Stock Options on Company Risk Taking and Performance,” Academy of Management Journal vol. 50, no. 5, 1055–1076. 72 Ulrike Malmendier, Enrico Moretti, and Florian S. Peters, “Winning by Losing: Evidence on the Long-Run Effects of Mergers,” working paper 18024, National Bureau of Economic Research, April 2012, http://emlab.berkeley.edu/~moretti/mergers.pdf. 73 Jeffrey S. Harrison and Derek K. Oler, “The Influence of Debt on Acquisition Performance,” Academy of Management Journal, August 2008. 74 Michael West, “When Fourth Out of Five Earns You a Squillion,” Sydney Morning Herald, Oct. 25, 2011.

A World Without Work: Technology, Automation, and How We Should Respond

by

Daniel Susskind

Published 14 Jan 2020

Back in the early days of the Internet, there was a moment when it seemed that these sorts of worries about location might no longer matter. Anybody with a connected machine would be able to work from anywhere. The “information highway” could be ridden by everyone, at little cost or inconvenience, from the comfort of their own living rooms. But that view turned out to be misconceived. As Enrico Moretti, perhaps the leading scholar studying these phenomena, puts it, today, despite “all the hype about the ‘death of distance’ and the ‘flat world,’ where you live matters more than ever.”27 In many ways, this is intuitive. Stories of technological progress are often tied up with tales of regional rise and fall: think of the Rust Belt versus Silicon Valley, for instance.

…

In 2015, the United States paid its nurses 1.24 times the average wage; the UK, 1.04; and France, 0.95. 26. Personal care aides (83.7 percent), registered nurses (89.9 percent), home health aides (88.6 percent), food preparation and services (53.8 percent), retail salespersons (48.2 percent). Again, see the US Bureau of Labor Statistics “Household Data.” 27. Enrico Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs (New York: First Mariner Books, 2013), p. 17. 28. Ibid., p. 23. 29. Ibid., pp. 82–5. 30. Ibid., p. 89. 31. Emily Badger and Quoctrung Bui, “What If Cities Are No Longer the Land of Opportunity for Low-Skilled Workers?,” New York Times, 11 January 2019. 32.

…

I disagree with Autor’s conclusion, but find the framing useful. 57. See http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview (accessed April 2018). 9. EDUCATION AND ITS LIMITS 1. See https://web.archive.org/web/20180115215736/twitter.com/jasonfurman/status/913439100165918721. 2. Enrico Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs (New York: First Mariner Books, 2013), p. 226. 3. Ibid., p. 228. 4. Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz, The Race Between Education and Technology (London: Harvard University Press, 2009), p. 13. 5. Ibid., p. 12. 6. Quoted in Michelle Asha Cooper, “College Access and Tax Credits,” National Association of Student Financial and Administrators (2005). 7.

The Next Factory of the World: How Chinese Investment Is Reshaping Africa

by

Irene Yuan Sun

Published 16 Oct 2017

Justin Yifu Lin, “From Flying Geese to Leading Dragons: New Opportunities and Strategies for Structural Transformation in Developing Countries,” World Bank, Washington, DC, June 2011, 4. J. Esteban, J. Stiglitz, and Justin Yifu Lin, eds., The Industrial Policy Revolution II: Africa in the Twenty-first Century (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). 10. Enrico Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs (Boston: Mariner, 2013), 21. 11. “Leveraging Africa’s Demographic Dividend,” African Business Magazine, January 14, 2015, http://africanbusinessmagazine.com/uncategorised/leveraging-africas-demographic-dividend/. 12. United Nations Population Division, “World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision.” 13.

…

Nigeria National Bureau of Statistics (Nigeria), “Unemployment/Under-employment Watch Q1 2016,” May 2016. 16. Ibid. 17. International Labour Organization, “Where Is the Unemployment Rate the Highest in 2014?” 18. World Bank, “Youth and Unemployment in Africa: The Potential, the Problem, the Promise” (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2009). 19. Enrico Moretti, New Geography of Jobs. 20. Ibid. 21. Kevin Watkins, Justin W. van Fleet, and Lauren Greubel, “Africa Learning Barometer,” Brookings Institute, http://www.brookings.edu/research/interactives/africa-learning-barometer. 22. African Development Bank, “Enhancing Capacity for Youth Employment in Africa: Some Emerging Lessons,” Africa Capacity Development Brief 2, no. 2, December 2011, http://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/Africa%20Capacity%20Dev%20Brief_Africa%20Capacity%20Dev%20Brief.pdf. 23.

Stuck: How the Privileged and the Propertied Broke the Engine of American Opportunity

by

Yoni Appelbaum

Published 17 Feb 2025

Jacoby, “Labor Mobility in a Federal System: The United States in Comparative Perspective,” International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations 20, no. 3 (2004); Holger Bonin, Werner Eichhorst, and Christer Florman, “Geographic Mobility in the European Union: Optimising Its Economic and Social Benefits,” Research Report No. 19, IZA Institute of Labor Economics, July 2008. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT A pair of economists: The idea is that when people move to more productive places, they themselves become more productive, spurring economic growth. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, “Why Do Cities Matter? Local Growth and Aggregate Growth,” SSRN Scholarly Paper, May 1, 2015; Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, “Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 11, no. 2 (2019): 1–39; Annie Lowrey, “The U.S. Needs More Housing Than Almost Anyone Can Imagine,” Atlantic, Nov. 21, 2022. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT Between 1880 and 1980: Jac C.

…

GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT Someone without a high school: Ben Sprung-Keyser, Nathaniel Hendren, and Sonya Porter, “The Radius of Economic Opportunity: Evidence from Migration and Local Labor Markets,” Center for Economic Studies, July 2022; David Card, Jesse Rothstein, and Moises Yi, “Location, Location, Location,” Center for Economic Studies, U.S. Census Bureau, Oct. 2021; Rebecca Diamond and Enrico Moretti, “Where Is Standard of Living the Highest? Local Prices and the Geography of Consumption,” Working Paper 29533, NBER Working Paper Series, Dec. 2021. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT Americans, for example, still move: Canada, Australia, and New Zealand have reported levels of geographic mobility that rival the United States in recent decades, although those numbers are surely influenced by the fact that the percentage of foreign-born residents in these countries in any given year has generally been at least twice as high as in the United States; data that would allow direct comparisons with the eras of peak mobility in the United States have not yet been developed, although narrative accounts of travelers point to the distinctiveness of the U.S. experience.

Hive Mind: How Your Nation’s IQ Matters So Much More Than Your Own

by

Garett Jones

Published 15 Feb 2015

Since computers are recording each and every step of the checkout process—including which clerk is doing the checkout at which terminal—it’s easy to see which clerks are more productive than others, who takes longer, who gets it done flawlessly and quickly. One can imagine that grocery stores care about such information, and indeed they do. But Berkeley economists Alexandre Mas and Enrico Moretti did something else with that information: they checked to see if workers became more productive when they were put onto a shift with the top clerks, and if they became less productive when put onto a shift with the weaker clerks.3 Perhaps it’s no surprise that on average clerks rose (or descended) to the occasion: just being placed on a shift with other workers who were 10 percent more productive made a worker 1.5 percent more productive on that shift.

…

Lynn, Richard, and Tatu Vanhanen. IQ and Global Inequality. Whitefish, MT: Washington Summit, 2006. Lynn, Richard, and Tatu Vanhanen. IQ and the Wealth of Nations. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2002. Mackintosh, Nicholas J. IQ and Human Intelligence, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011. Mas, Alexandre, and Enrico Moretti. “Peers at Work.” American Economic Review 99, no. 1 (2009): 112–145. McHenry, Jeffrey J., Leaetta M. Hough, Jody L. Toquam, Mary Ann Hanson, and Steven Ashworth. “Project A Validity Results: The Relationship Between Predictor and Criterion Domains.” Personnel Psychology 43, no. 2 (1990): 335–354.

Age of the City: Why Our Future Will Be Won or Lost Together

by

Ian Goldin

and

Tom Lee-Devlin

Published 21 Jun 2023

Historians, economists, sociologists, urban planners and other experts all look at cities through different lenses. Each are valuable, but problems do not emerge in disciplinary silos, nor do solutions. We are far from the first to recognize the fundamental importance of cities to the modern world. Ed Glaeser’s Triumph of the City, Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class, Enrico Moretti’s The New Geography of Jobs and many other excellent books over recent years have laid a trail before us, as have canonical works such as Lewis Mumford’s The City in History, Peter Hall’s Cities in Civilization, Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities and Paul Bairoch’s Cities and Economic Development.

…

When a city brings in new jobs in the tradeable sector, these workers also consume the services of the non-tradeable sector, creating a multiplier effect for the local economy. While some of these are high-skill jobs – for example, doctors, lawyers, architects and chefs – the majority are low-skill roles like waiters, cleaners, childcare workers and construction labourers. The economist Enrico Moretti has studied these multipliers, and found that the creation of one new tradeable sector job in an area generates demand for 1.6 new jobs in the non-tradeable sector, as these workers go to restaurants, get haircuts, visit the doctor and build new houses.33 However, this multiplier effect is far stronger for jobs in high-skill tradeable sectors – say at a company like Apple – where one new job in an area can generate as many as five new non-tradeable jobs in its wake.34 This is not just because high-skill workers tend to have greater incomes, but also because they are often time poor and more likely to eat out and spend on services such as household cleaning.

The Rent Is Too Damn High: What to Do About It, and Why It Matters More Than You Think

by

Matthew Yglesias

Published 6 Mar 2012

Many observers have noted that the so-called college wage premium—the gap between what college graduates and those without college degrees earn—has increased over the past thirty or forty years. This increases income inequality. Gordon argues that the real increase in inequality hasn’t been as large as it first appears, noting research from Enrico Moretti and concluding that “fully two-thirds of the previously documented increase in the return to college between 1980 and 2000 vanishes when [Moretti] corrects for differences in the cost of living across metropolitan areas.” This finding is important but Gordon is, I think, misinterpreting it. The measured inequality in earnings may vanish when you control for cost of living, but the actual money doesn’t vanish.

SuperFreakonomics

by

Steven D. Levitt

and

Stephen J. Dubner

Published 19 Oct 2009

This may range from the overt—denying a woman a promotion purely because she is not a man—to the insidious. A considerable body of research has shown that overweight women suffer a greater wage penalty than overweight men. The same is true for women with bad teeth. There are some biological wild cards as well. The economists Andrea Ichino and Enrico Moretti, analyzing personnel data from a large Italian bank, found that female employees under forty-five years old tended to miss work consistently on twenty-eight-day cycles. Plotting these absences against employee productivity ratings, the economists determined that this menstrual absenteeism accounted for 14 percent of the difference between female and male earnings at the bank.

…

. / 21 Wage penalty for overweight women: see Dalton Conley and Rebecca Glauber, “Gender, Body Mass and Economic Status,” National Bureau of Economics Research working paper, May 2005. / 21 Women with bad teeth: see Sherry Glied and Matthew Neidell, “The Economic Value of Teeth,” NBER working paper, March 2008. / 21 The price of menstruation: see Andrea Ichino and Enrico Moretti, “Biological Gender Differences, Absenteeism and the Earnings Gap,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1, no. 1 (2009). / 22 Title IX creates jobs for women; men take them: see Betsey Stevenson, “Beyond the Classroom: Using Title IX to Measure the Return to High School Sports,” The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, June 2008; Linda Jean Carpenter and R.

The New Class Conflict

by

Joel Kotkin

Published 31 Aug 2014

The new, young, heavily immigrant tech workforce, unlike many middle-class Americans, are often willing to live in crowded apartment complexes or to buy or rent a house in an almost absurdly distant periphery of the region.134 In the end, technocoolies may prove as valuable today as Chinese and Irish railway workers were to the railroad builders or as New England farm girls were to the early textile mills: they provide a largely compliant and cheap labor force to complement the swelling numbers overseas.135 But what they do not seem to do is add much to the upward mobility of the vast majority of Americans, including those in Silicon Valley itself. The Two Valleys: Precursors of the American Future? Tech industry boosters such as U.C. Berkeley’s Enrico Moretti extol the broad societal virtues of the new tech Oligarchy, claiming they constitute the key to a growing economy and greater regional well-being. This is also the widespread conventional wisdom in both parties, among both left and right, and throughout the media.136 Yet in reality, high-technology industries have long been characterized by what one researcher described as “a highly unequal structure of employment,” with sharp divisions between the top employees and low-wage workers in retail and other service industries such as janitors, clerks, and cashiers.137 Valley boosters speak of the “glorious cocktail of prosperity” they have concocted, but they have been very slow to address the social problems festering at their feet, apparently out of their line of sight.

…

Charlotte Allen, “Silicon Chasm: The Class Divide on America’s Cutting Edge,” Weekly Standard, December 2, 2013; Vivek Wadhwa, “Silicon Valley’s Dark Secret: It’s All About Age,” TechCrunch, August 28, 2010, http://techcrunch.com/2010/08/28/silicon-valley%E2%80%99s-dark-secret-it%E2%80%99s-all-about-age. 135. Mickey Kaus, “Zuckerberg Buys Beltway Fakery,” Daily Caller, April 25, 2013, http://dailycaller.com/2013/04/25/facebook-founder-buys-beltway-fakery. 136. Enrico Moretti, “Where the Good Jobs Are—and Why,” Wall Street Journal, September 17, 2013. 137. Chris Benner, “Win the Lottery or Organize: Traditional and non-Traditional Labor Organizing in Silicon Valley,” Berkeley Planning Journal, vol. 12 (1998): 50–71. 138. Martha Mendoza, “Silicon Valley Poverty Is Often Ignored By The Tech Hub’s Elite,” Huffington Post, March 10, 2013, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/03/10/silicon-valley-poverty_n_2849285.html; Keith Matheny, “Techies Can Appear Slow to Embrace Philanthropy,” USA Today, June 18, 2012; “Why Is Silicon Valley’s Philanthropy Sluggish?”

Abundance

by

Ezra Klein

and

Derek Thompson

Published 18 Mar 2025

Instead, they thrived, attaining a centrality in modernity they didn’t possess even in antiquity. This, Glaeser writes, is “the central paradox of the modern metropolis—proximity has become ever more valuable as the cost of connecting across long distances has fallen.”11 In The New Geography of Jobs, Enrico Moretti, an economist at the University of California at Berkeley, explains why. A century ago, the American economy produced primarily physical goods. Now we make ideas and services. Some of those are encoded into physical goods, but even then, production often happens elsewhere. The iPhone made Apple, based in Cupertino, California, into the most valuable company in the world even though two-thirds of the phones are assembled in Foxconn factories in Shenzhen, China.12 Microsoft and Alphabet mostly sell bits of intangible code.

…

US Securities and Exchange Commission, Form 10-K, Tesla, Inc., for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2023, https://ir.tesla.com/_flysystem/s3/sec/000162828024002390/tsla-20231231-gen.pdf. 16. Glaeser, Triumph of the City, Kindle, 6. 17. Katie Deighton, “Goldman Sachs Embeds Software Developers Deeper into the Business,” Wall Street Journal, October 19, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/goldman-sachs-embeds-software-developers-deeper-into-the-business-11666218724. 18. Enrico Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs (New York: Mariner Books/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013), Kindle, loc. 1641. 19. Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs, Kindle, loc. 1673. 20. Jackson Walker, “Zoom CEO Advises Employees to Return to Office or Risk Losing ‘Trust,’ Report Says,” CBS Austin, August 24, 2023, https://cbsaustin.com/news/nation-world/zoom-ceo-advises-employees-to-return-to-office-or-risk-losing-trust-report-says-remote-work-telework-conferencing-virtual-hybrid-economy-employee-face-to-face. 21.

Fully Grown: Why a Stagnant Economy Is a Sign of Success

by

Dietrich Vollrath

Published 6 Jan 2020

This isn’t necessarily true, as we don’t know what the marginal output of a worker—the effect on output of adding or subtracting one worker—is in each location, just the average output of all workers. If a worker from Lake Havasu, Arizona, moves to New York, there is no guarantee that he or she would instantly produce three times more output or be paid three times more in wages. As Enrico Moretti documented in his recent book, there is only a subset of urban areas where we might expect new workers to gain from a move. These select locations—Silicon Valley, the Research Triangle in North Carolina, Austin, Seattle, and New York, among others—are innovation centers, as compared to other urban areas that may be large but present fewer opportunities.

…

We might attribute the slowdown in reallocation to restrictions on housing supply in productive places, something the aggregate data on the economic profits of housing is consistent with. Even if you buy all that, though, how big of an effect on productivity could this have had? Some recent research by Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti attempts to calculate the effect of housing restrictions in very productive cities on productivity growth. There is no clean empirical way to estimate this; we do not have a bizarro Earth in which San Jose approved a series of fifty-story apartment buildings to compare to the actual Earth. So Hsieh and Moretti set up a model that allows for multiple cities, with workers who are free to move around between cities and who care about their real living standard, which is wage divided by the price of a house in the city they live in.

Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities

by

Alain Bertaud

Published 9 Nov 2018

The above example of inclusionary zoning is not just an anecdotal illustration of a poorly designed housing policy. It represents a trend in many of the most economically successful cities in the world. The increasing regulatory frenzy that characterizes some cities like New York imposes large economic costs on the entire country. In a paper published in 2015, the economists Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti found that, between 1964 and 2009, the high cost of housing in some US cities relative to wages had lowered aggregate US GDP by 13.5 percent: Most of the loss was likely caused by increased constraints to housing supply in high productivity cities like New York, San Francisco and San Jose. Lowering regulatory constraints in these cities to the level of the median city would expand their work force and increase U.S.

…

Kate Barker’s two reports and Paul Cheshire’s book should be compulsory reading for every urban planner concerned with housing price and housing affordability. In chapter 8, I will describe more in detail what, in my opinion, planners should do to improve their performance and their contribution to the management of cities. Notes 1. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, “Why Do Cities Matter? Local Growth and Aggregate Growth,” NBER Working Paper 21154, National Bureau of Economic Standards, Cambridge, MA, May 2015 (revised June 2015). 2. Angus Deaton, The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013), 16. 3.

…

Willis, and Jessica Yager “State of New York City’s Housing and Neighborhoods in 2015,” Furman Center, New York University, New York, 2016. 22. See http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/18/nyregion/donald-trump-tax-breaks-real-estate.html?hp&action=click&pgtype=Homepage&clickSource=story-heading&module=first-column-region®ion=top-news&WT.nav=top-news. 23. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, “Why Do Cities Matter? Local Growth and Aggregate Growth,” NBER Working Paper 21154, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, May 2015 (revised June 2015), 4. 24. See an analysis of kampung infrastructure issues and improvement in the World Bank document by Alcira Kreimer, Roy Gilbert, Claudio Volonte, and Gillie Brown, “Indonesia Impact Evaluation Report—Enhancing the Quality of Life in Urban Indonesia: The Legacy of Kampung Improvement Program,” World Bank, Washington, DC, June 29, 1995.

The Upside of Inequality

by

Edward Conard

Published 1 Sep 2016

But with the share of top-performing U.S. students earning STEM-related degrees declining sharply over the last two decades, the industry has turned to foreign-born workers and, increasingly, offshore workers to fill its talent needs.60 While American consumers will benefit from discoveries made in other countries, discoveries made and commercialized here have driven and will continue to drive demand for U.S. employment, both skilled and unskilled, at least indirectly through growing consumption. University of California, Berkeley, economics professor Enrico Moretti estimates each additional high-tech job creates nearly five jobs in the local economy, more than any other industry creates.61 Unlike a restaurant, for example, high-tech employment tends to increase demand overall rather than merely shifting employment from one competing establishment to another.

…

Lowell, Hal Salzman, Hamutal Bernstein, and Everett Henderson, “Steady as She Goes? Three Generations of Students Through the Science and Engineering Pipeline,” Annual Meetings of the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management, Washington, DC, November 7, 2009, http://www.ewa.org/sites/main/files/steadyasshegoes.pdf. 61. Enrico Moretti, “Local Multipliers,” American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 100 (2010), http://eml.berkeley.edu//~moretti/multipliers.pdf. 62. “Digest of Education Statistics: Table 104.91, 2014” National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, 2014, http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d14/tables/dt14_104.91.asp.

Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier

by

Edward L. Glaeser

Published 1 Jan 2011

A Financial History of the United States: From Christopher Columbus to the Robber Barons 1492- 1900. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2002. Marshall, Alex, and David Emblidge. Beneath the Metropolis: The Secret Lives of Cities. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2006. Martin, Sandra. “‘The Greatest Architect We Have Ever Produced.’” Toronto Globe and Mail, May 22, 2009, p. S8. Mas, Alexandre, and Enrico Moretti. “Peers at Work.” American Economic Review 99, no. 1 (Mar. 2009): 112-45. Mason, Shena. Matthew Boulton: Selling What All the World Desires. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009. Maurseth, Per Botolf, and Bart Verspagen. “Knowledge Spillovers in Europe: A Patent Citations Analysis.” Scandinavian Journal of Economics 104, no. 4 (Dec. 2002): 531-45.

…

Miller, Donald L. City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996. Miller, Matthew, Deborah Azrael, and David Hemenway. “Household Firearm Ownership and Suicide Rates in the United States.” Epidemiology 13, no. 5 (Sept. 2002): 517-24. Milligan, Kevin, Enrico Moretti, and Philip Oreopoulous. “Does Education Improve Citizenship? Evidence from the U.S. and the U.K.” Journal of Public Economics 88, no. 9-10 (Aug. 2004): 1667-95. Minchinton, Walter E. “Bristol: Metropolis of the West in the Eighteenth Century.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Fifth Series, vol. 4 (1954): 69-89.

Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes

by

Mark Penn

and

E. Kinney Zalesne

Published 5 Sep 2007

In Japan, they’re parasaito shinguru (parasite singles), or freeters, which is a combination of “free” and the German word for “worker,” arbeiter. In the U.S., they’re “boomerangs,” “Peter Pans,” or “kidults.” But Italian Mammonis take the cake at the astounding stay-at-home rate of 4 in 5. Source: Marco Manacorda and Enrico Moretti, Why Do Most Italian Young Men Live with Their Parents? Intergenerational Transfers and Household Structure, Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2005 What happened? Most observers say that Mammonis have been spawned by Italy’s high youth unemployment, high housing costs, and low and declining fertility.

…

Data on North American LATers come from Anne Milan and Alice Peters, “Couples Living Apart,” Canadian Social Trends, Summer 2003, Statistics Canada, Catalogue No. 11-008. The National Association of Home Builders Survey was cited in Tracie Rozhon, “To Have, Hold, and Cherish, Until Bedtime,” New York Times, March 11, 2007. Mammonis (Italy) Data on Italian men living at home were taken largely from Marco Manacorda and Enrico Moretti, “Why Do Most Italian Young Men Live with Their Parents? Intergenerational Transfers and Household Structure,” Centre for Economic Policy Research, June 2005, <http://www.cepr.org/pubs/dps/DP5116.asp>, accessed November 2006. Other helpful articles included “Italian Parents Under Accusation,” La Repubblica, February 3, 2006 (thanks to Enzo Caiazzo, CEO of Alenia, Inc., and Kristin Uzun, for help in translation); Gary Picariello, “In Italy—Living at Home Well into Your 30s Is Perfectly Normal,” Associated Content, 2006; Donald MacLeod, “Italian Mammas Making Offers Their Sons Can’t Refuse,” Guardian Unlimited, February 3, 2006; and Deidre Van Dyke, “Parlez-Vous Twixter,” Time, January 16, 2004.

Fulfillment: Winning and Losing in One-Click America

by

Alec MacGillis

Published 16 Mar 2021

Now the huge rewards lay in the innovation itself, which could produce outsized returns with very little additional capital. Once you came up with great new software, you could reproduce it at barely any cost—no coal and iron ore required. Everything lay in having the minds to produce that initial breakthrough. “Economic value depends on talent as never before,” wrote Enrico Moretti, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley. “In the twentieth century, competition was about accumulating physical capital. Today it is about attracting the best human capital.” Crucially, this held true even if the cluster became ever more expensive. Instead of a market rebalancing—a dispersal to more affordable locales—a feedback loop prevailed.

…

It was “the recruiting pool”: “Jeff Bezos at the Economic Club of Washington (9/13/18),” CNBC livestream, https://youtu.be/xv_vkA0jsyo. “Cities are effectively machines”: Geoffrey West, Scale: The Universal Laws of Growth, Innovation, Sustainability, and the Pace of Life in Organisms, Cities, Economies, and Companies (New York: Penguin, 2017), 323. “Economic value depends on talent”: Enrico Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs (New York: Mariner Books, 2013), 66. deliberately choosing one that had a garage: Brandt, One Click, 60. “This is not only the largest river”: Stone, The Everything Store, 55. “For me the city is still inarticulate”: D’Ambrosio, “Seattle, 1974,” 33. The average income for the top 20 percent: Gene Balk, “Seattle Hits Record High for Income Inequality, Now Rivals San Francisco,” The Seattle Times, November 17, 2017.

Connectography: Mapping the Future of Global Civilization

by

Parag Khanna

Published 18 Apr 2016

Cutting off American investment (and thus profits) overseas will therefore lead to reduced investment at home too. Remember tug-of-war: Be careful when untangling the rope. Even what looks like de-globalization is actually still globalization. Apple is a perfect example of these complex realities. The Berkeley economist Enrico Moretti estimates that Apple is substantially responsible for sixty thousand jobs in Silicon Valley, only twelve thousand of which are employees in its Cupertino headquarters. “In Silicon Valley,” Moretti claims, “high-tech jobs are the cause of local prosperity, and the doctors, lawyers, roofers and yoga teachers are the effect.”2 What appears a thriving community is primarily the result of corporate innovation and global growth—not public investment.

…

In early 2015, the trading house Itochu made the largest Japanese foreign investment ever in China, buying (together with Thailand’s CP Group) a 10 percent stake in CITIC, one of China’s oldest and most respected conglomerates. CHAPTER 7: THE GREAT SUPPLY CHAIN WAR 1. Interview with author, July 18, 2015. 2. Enrico Moretti, The New Geography of Jobs (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012). 3. Josh Tyrangiel, “Tim Cook’s Freshman Year: The Apple CEO Speaks,” Bloomberg Businessweek, Dec. 6, 2012. 4. However, additive manufacturing and the sharing economy together do cause tremendous domestic dislocation. The construction sector is not tradable, but it can increasingly be automated as entire homes are designed, printed, and assembled out of 3-D printing kits, displacing contractors and builders across America and Europe. 5.

Capitalism in America: A History

by

Adrian Wooldridge

and

Alan Greenspan

Published 15 Oct 2018

House prices are always going to be higher in successful economic clusters because so many people want to live there. But today’s capitals of creativity, particularly San Francisco, are also capitals of NIMBY-ism, encrusted with rules and restrictions that make it much more difficult to build new houses or start new businesses. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti estimate that if it were cheaper to move to America’s high productive cities, the country’s gross domestic product would be 9.5 percent higher due to the gains from better jobs.5 Other forms of mobility are also in decline. Upward mobility is becoming more difficult: Raj Chetty of Stanford University has calculated, on the basis of an extensive study of tax records, that the odds of a thirty-year-old earning more than his parents at the same age has fallen from 86 percent forty years ago to 51 percent today.6 A 2015 study by three Federal Reserve economists and a colleague at Notre Dame University demonstrated that the level of churning between jobs has been dropping for decades.

…

Cowen’s book has been an invaluable source of data and references for this chapter. 3. Oscar Handlin and Lilian Handlin, Liberty in Expansion 1760–1850 (New York: Harper & Row, 1989), 13. 4. See Patrick Foulis, “The Sticky Superpower,” Economist, October 3, 2016. 5. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, “Why Do Cities Matter? Local Growth and Aggregate Growth,” NBER Working Paper No. 21154, National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2015; Cowen, The Complacent Class, 8. 6. Raj Chetty et al., “The Fading American Dream: Trends in Absolute Income Mobility Since 1940,” NBER Working Paper No. 22910, National Bureau of Economic Research, March 2017. 7.

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History

by

Kurt Andersen

Published 14 Sep 2020

On the other hand, if you come from an upper-middle-class or rich household, the odds are strong you’ll remain upper middle class or rich as an adult. When inequality started increasing in the 1980s, separating the fortunate few and the unfortunate majority, it showed up geographically as well: not only were only the rich getting richer, but neighborhoods and cities and regions segregated accordingly. The economist Enrico Moretti calls this the Great Divergence. Before the 1980s, the decade in which gated communities became common, Americans tended to live more democratically. Americans with more money and less money were likelier to live alongside one another. In 1970 only one in seven Americans lived in a neighborhood that was distinctly richer or poorer than their metropolitan area overall, but that fraction began growing in the 1980s, and by the 2000s it was up to a third.

…

“The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” Harper’s Magazine, November 1964. Horowitz, Michael. “The Public Interest Law Movement: An Analysis with Special Reference to the Role and Practices of Conservative Public Interest Law Firms,” unpublished ms. prepared for the Scaife Foundation, 1980. Hsieh, Chang-Tai, and Enrico Moretti. “Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 11, no. 2 (2019): 1–39. Hunter, Louis C. A History of Industrial Power in the United States, 1780–1930. 3 vols. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1979, 1985, 1991. Husain, Amir. The Sentient Machine: The Coming Age of Artificial Intelligence.

The Third Pillar: How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind

by

Raghuram Rajan

Published 26 Feb 2019

That the whole is greater than the sum of the parts when capable people congregate together is a form of what economists term “agglomeration economies.” This would explain why some regions like Silicon Valley or cities like London, New York, or San Francisco become magnets for the capable and talented, where they meet one another and become yet more successful. My colleague Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti from Berkeley estimate that the dispersion in wages across US cities in 2009 was twice as large as in 1964, in part because of the emergence of superstar cities like New York, San Francisco, and San Jose.10 They argue that simply reducing the stringent zoning regulations in New York, San Jose, and San Francisco to that of the median US city, and thus allowing freer worker movement into those cities with a red-hot job market, would have increased GDP per US worker by an additional $3,685 in 2009.

…

The Information Revolution in Small Business Lending,” Journal of Finance 57, no. 6 (December 2002): 2533–70. 9. Christopher R. Berry and Edward L. Glaeser, “The Divergence of Human Capital Levels Across Cities,” Papers in Regional Science 84, no. 3 (December 2005): 407–44. 10. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, “Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation,” rev. ed., NBER Working Paper No. 21154, May 2017. 11. Han Kim, Adair Morse, and Luigi Zingales, “Are Elite Universities Losing their Edge,” Journal of Financial Economics 93 (2009) 353–81. 12. Brooks, “Bobos in Paradise”; Charles Murray, Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960–2010 (New York: Random House Digital, 2013); Ross Douthat and Reihan Salam, Grand New Party: How Republicans Can Win the Working Class and Save the American Dream (New York: Doubleday, 2008). 13.

The Survival of the City: Human Flourishing in an Age of Isolation

by

Edward Glaeser

and

David Cutler

Published 14 Sep 2021

Instead, we have a geographic stasis where places marked by high levels of long-term joblessness in 1980, like the Rust Belt, Appalachia, and the Mississippi Delta region, still had high rates of long-term joblessness in 2015. America’s most productive cities are failing the larger economy, partially because they don’t provide enough space for ordinary people to live. The economists Chang-Tai Hsieh of the University of Chicago and Enrico Moretti of UC Berkeley estimate that the US economy would be substantially larger if people could move more easily to productive areas, like New York City and San Francisco. If workers are 30 percent more productive in Silicon Valley than in Detroit, then America automatically becomes more productive when migrants go west.

…

Time, December 8, 2008. http://content.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,20081208,00.html. “How Many Calories in McDonald’s French Fries, Large.” CalorieKing. Accessed December 29, 2020. www.calorieking.com/us/en/foods/f/calories-in-hot-fries-chips-french-fries-large/9OxHtBz6TT23cv9Osx5OnA. Hsieh, Chang-Tai, and Enrico Moretti. “Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 11, no. 2 (April 2019): 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20170388. Hui, Sylvia. “UK Ramps Up Vaccine Rollout, Targets Every Adult by Autumn.” Associated Press, January 10, 2021. https://apnews.com/article/international-news-england-coronavirus-pandemic-coronavirus-vaccine-ca01f408423b049a7625c6f431acdd8d.

Economic Gangsters: Corruption, Violence, and the Poverty of Nations

by

Raymond Fisman

and

Edward Miguel

Published 14 Apr 2008