Fall of the Berlin Wall

description: the dismantling of the wall that divided Berlin from 1961 to 1989, which symbolized the end of the Cold War and paved the way for German reunification.

445 results

Burning Down the Haus: Punk Rock, Revolution, and the Fall of the Berlin Wall

by Tim Mohr · 10 Sep 2018 · 370pp · 107,791 words

Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the Former German Democratic Republic (BStU) Burning Down The Haus Punk Rock, Revolution, and the Fall of the Berlin Wall By Tim Mohr ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2018 Contents Preface Introduction I: Too Much Future II: Oh Bondage Up Yours! III: Combat Rock IV

…

bars and clubs in the East and established in the process the ethos of the fledgling new society being built almost from scratch after the fall of the Berlin Wall. This kaleidoscopic world I had fallen in love with was their world, their creation. At the time I had no idea I would eventually become

The Year That Changed the World: The Untold Story Behind the Fall of the Berlin Wall

by Michael Meyer · 7 Sep 2009 · 323pp · 95,188 words

Also by Michael Meyer The Alexander Complex THE YEAR THAT CHANGED THE WORLD The Untold Story behind the Fall of the Berlin Wall MICHAEL MEYER SCRIBNER A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 www.SimonandSchuster.com Copyright © 2009 by Michael

…

complete victory.” Again, the Reagan echo with a nod to Winston Churchill. Be resolute, and the enemy will blink. Goodness and light will triumph. The fall of the Berlin Wall serves as proof and inspiration. There’s only one problem—that of disjuncture, a confusion of cause and effect. What if it didn’t happen

…

we could go ahead. It opened the way for everything that would follow,” he said, from the creation of a democratic Hungary to, ultimately, the fall of the Berlin Wall. This brief encounter with Gorbachev, coming with the first breath of spring after a long winter, would prove to be a hidden but decisive turning

…

will grow relative to that of the United States. All this will accelerate the trend away from the America-centric world that began with the fall of the Berlin Wall, and it will unfold in ways that are difficult to predict. Even amid the worst days of the Iraq war, when the world’s anger

…

to call it definitive history; this book might better be thought of merely as a firsthand account of the revolutions in Eastern Europe and the fall of the Berlin Wall. Unusually among foreign correspondents, I was on scene for most of the events described, with few exceptions. My beat for Newsweek ran from Germany through

…

, which among other things is the source of the Allensbach data on West German attitudes toward the Wall and reunification; William F. Buckley Jr., The Fall of the Berlin Wall, 2004. One of the best travelogues of this genre ever written is Anthony Bailey’s The Edge of the Forest, a reporter-at-large feature

…

European Community (EC), 229 European Union, Cold War and, 21 “Evil Empire,” collapse of, 2, 14, 215–216 exit visas, 8–9, 118, 165, 168 Fall of the Berlin Wall, The (Buckley), 223 Fall of the Wall, The (BBC-Spiegel TV documentary), 228, 231, 232, 234, 235 Farocki, Harun, 236 Faust’s Metropolis (Richie), 25

The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens

by Gabriel Zucman, Teresa Lavender Fagan and Thomas Piketty · 21 Sep 2015 · 121pp · 34,193 words

/upload/pdf/Price_of_Offshore_Revisited_120722.pdf. 16. Ruth Judson, “Crisis and Calm: Demand for U.S. Currency at Home and Abroad from the Fall of the Berlin Wall to 2011,” IFDP working paper of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, November 2012, http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdp/2012/1058

How to Stop Brexit (And Make Britain Great Again)

by Nick Clegg · 11 Oct 2017 · 93pp · 30,572 words

of democracy’s victory over fascism. And for the many central and eastern European nations that began the process of applying for membership after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, becoming part of the EU was a demonstration of their new-found freedom from the grip of Soviet-era communism. In all these

What About Me?: The Struggle for Identity in a Market-Based Society

by Paul Verhaeghe · 26 Mar 2014 · 208pp · 67,582 words

the fascist concentration camps and the communist gulags as a legacy of the Enlightenment, arguing that it was time to put on the brakes. The fall of the Berlin Wall put the final nail in the coffin of ideology, and so the idea of an engineered society was shelved. Change and perfectibility remained keywords, but

24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep

by Jonathan Crary · 3 Jun 2013 · 102pp · 33,345 words

grain. The “short twentieth century” was coming to an abrupt end, between 1989 and 1991, with what to many seemed like hopeful developments, including the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of a bipolar, Cold War world. Along with the triumphalist narratives of globalization and the facile declarations of the historical end of

The Skeptical Economist: Revealing the Ethics Inside Economics

by Jonathan Aldred · 1 Jan 2009 · 339pp · 105,938 words

serves to protect the economic orthodoxy. In some ways the orthodoxy has served us, in rich economies, quite well. For a brief period after the fall of the Berlin Wall, some even talked of ‘The End of History’. Our economic problems were solved, and something called ‘The New Economy’ had arrived, promising endless prosperity - or

Brexit Unfolded: How No One Got What They Want (And Why They Were Never Going To)

by Chris Grey · 22 Jun 2021 · 334pp · 91,722 words

up with the idea of economic globalisation, but it also implied a unipolar geopolitics and a trend to ideological homogeneity. Thirty years on from the fall of the Berlin Wall, that analysis has turned out to be naïve in almost every respect. The world is not unipolar (nor is it any longer bipolar in the

Eurowhiteness: Culture, Empire and Race in the European Project

by Hans Kundnani · 16 Aug 2023 · 198pp · 54,815 words

of challenging the hegemony of the dollar—but France and West Germany had been unable to overcome their different visions for it. However, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, with German unification imminent, French President François Mitterrand saw it as a way to constrain a more powerful Germany and pushed Chancellor Helmut Kohl to

Bosnia & Herzegovina--Culture Smart

by Elizabeth Hammond · 11 Jan 2011 · 105pp · 33,036 words

through a strongly nationalist set of policies. He revoked the autonomy of Kosovo and Vojvodina, causing massive protests from those who lived there. After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, some of the Yugoslav republics, namely Croatia and Slovenia, started pushing for more independence. Croatian nationalism was growing

GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History

by Diane Coyle · 23 Feb 2014 · 159pp · 45,073 words

Social Capital and Civil Society

by Francis Fukuyama · 1 Mar 2000

Getting Better: Why Global Development Is Succeeding--And How We Can Improve the World Even More

by Charles Kenny · 31 Jan 2011 · 272pp · 71,487 words

Stubborn Attachments: A Vision for a Society of Free, Prosperous, and Responsible Individuals

by Tyler Cowen · 15 Oct 2018 · 140pp · 42,194 words

Conflicted: How Productive Disagreements Lead to Better Outcomes

by Ian Leslie · 23 Feb 2021 · 280pp · 82,393 words

Peers, Pirates, and Persuasion: Rhetoric in the Peer-To-Peer Debates

by John Logie · 29 Dec 2006 · 173pp · 14,313 words

Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the World

by Branko Milanovic · 23 Sep 2019

Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming

by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby · 22 Nov 2013 · 165pp · 45,397 words

Mapmatics: How We Navigate the World Through Numbers

by Paulina Rowinska · 5 Jun 2024 · 361pp · 100,834 words

Rethinking Money: How New Currencies Turn Scarcity Into Prosperity

by Bernard Lietaer and Jacqui Dunne · 4 Feb 2013

Big Capital: Who Is London For?

by Anna Minton · 31 May 2017 · 169pp · 52,744 words

The Making of a World City: London 1991 to 2021

by Greg Clark · 31 Dec 2014

A World in Disarray: American Foreign Policy and the Crisis of the Old Order

by Richard Haass · 10 Jan 2017 · 286pp · 82,970 words

The Government of No One: The Theory and Practice of Anarchism

by Ruth Kinna · 31 Jul 2019 · 405pp · 103,723 words

The Challenge for Africa

by Wangari Maathai · 6 Apr 2009 · 288pp · 90,349 words

The Divided Nation: A History of Germany, 1918-1990

by Mary Fulbrook · 14 Oct 1991 · 934pp · 135,736 words

Head, Hand, Heart: Why Intelligence Is Over-Rewarded, Manual Workers Matter, and Caregivers Deserve More Respect

by David Goodhart · 7 Sep 2020 · 463pp · 115,103 words

Revolution Française: Emmanuel Macron and the Quest to Reinvent a Nation

by Sophie Pedder · 20 Jun 2018 · 337pp · 101,440 words

Built for Growth: How Builder Personality Shapes Your Business, Your Team, and Your Ability to Win

by Chris Kuenne and John Danner · 5 Jun 2017 · 276pp · 64,903 words

Nation-Building: Beyond Afghanistan and Iraq

by Francis Fukuyama · 22 Dec 2005

Revolting!: How the Establishment Are Undermining Democracy and What They're Afraid Of

by Mick Hume · 23 Feb 2017 · 228pp · 68,880 words

Bounce: Mozart, Federer, Picasso, Beckham, and the Science of Success

by Matthew Syed · 19 Apr 2010 · 304pp · 84,396 words

The Virtue of Nationalism

by Yoram Hazony · 3 Sep 2018 · 333pp · 86,628 words

After Europe

by Ivan Krastev · 7 May 2017 · 100pp · 31,338 words

A Brief History of Neoliberalism

by David Harvey · 2 Jan 1995 · 318pp · 85,824 words

Basic Income: A Radical Proposal for a Free Society and a Sane Economy

by Philippe van Parijs and Yannick Vanderborght · 20 Mar 2017

Age of Anger: A History of the Present

by Pankaj Mishra · 26 Jan 2017 · 410pp · 106,931 words

How Democracies Die

by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt · 16 Jan 2018 · 340pp · 81,110 words

Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of Flags

by Tim Marshall · 21 Sep 2016 · 276pp · 78,061 words

ECOVILLAGE: 1001 ways to heal the planet

by Ecovillage 1001 Ways to Heal the Planet-Triarchy Press Ltd (2015) · 30 Jun 2015

The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis

by Christiana Figueres and Tom Rivett-Carnac · 25 Feb 2020 · 197pp · 49,296 words

The Journey of Humanity: The Origins of Wealth and Inequality

by Oded Galor · 22 Mar 2022 · 426pp · 83,128 words

The Marginal Revolutionaries: How Austrian Economists Fought the War of Ideas

by Janek Wasserman · 23 Sep 2019 · 470pp · 130,269 words

Practical Anarchism: A Guide for Daily Life

by Scott. Branson · 14 Jun 2022 · 198pp · 63,612 words

How to Change the World: Reflections on Marx and Marxism

by Eric Hobsbawm · 5 Sep 2011 · 621pp · 157,263 words

The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success

by William Thorndike · 14 Sep 2012 · 330pp · 59,335 words

Pattern Breakers: Why Some Start-Ups Change the Future

by Mike Maples and Peter Ziebelman · 8 Jul 2024 · 207pp · 65,156 words

Pax Technica: How the Internet of Things May Set Us Free or Lock Us Up

by Philip N. Howard · 27 Apr 2015 · 322pp · 84,752 words

Protocol: how control exists after decentralization

by Alexander R. Galloway · 1 Apr 2004 · 287pp · 86,919 words

Barefoot Into Cyberspace: Adventures in Search of Techno-Utopia

by Becky Hogge, Damien Morris and Christopher Scally · 26 Jul 2011 · 171pp · 54,334 words

The Skripal Files

by Mark Urban · 291pp · 85,908 words

Brave New World of Work

by Ulrich Beck · 15 Jan 2000 · 236pp · 67,953 words

The Curse of Cash

by Kenneth S Rogoff · 29 Aug 2016 · 361pp · 97,787 words

9-11

by Noam Chomsky · 29 Aug 2011

The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality From the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century

by Walter Scheidel · 17 Jan 2017 · 775pp · 208,604 words

Branded Beauty

by Mark Tungate · 11 Feb 2012 · 290pp · 87,084 words

The Next Decade: Where We've Been . . . And Where We're Going

by George Friedman · 25 Jan 2011 · 249pp · 79,740 words

Falling Behind: Explaining the Development Gap Between Latin America and the United States

by Francis Fukuyama · 1 Jan 2006

On Nature and Language

by Noam Chomsky · 16 Apr 2007

Pocket Rough Guide Berlin (Travel Guide eBook)

by Rough Guides · 16 Oct 2019 · 212pp · 49,082 words

Markets, State, and People: Economics for Public Policy

by Diane Coyle · 14 Jan 2020 · 384pp · 108,414 words

There's a War Going on but No One Can See It

by Huib Modderkolk · 1 Sep 2021 · 295pp · 84,843 words

Limitarianism: The Case Against Extreme Wealth

by Ingrid Robeyns · 16 Jan 2024 · 327pp · 110,234 words

How to Blow Up a Pipeline

by Andreas Malm · 4 Jan 2021 · 156pp · 49,653 words

Against the Machine: On the Unmaking of Humanity

by Paul Kingsnorth · 23 Sep 2025 · 388pp · 110,920 words

23 Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalism

by Ha-Joon Chang · 1 Jan 2010 · 365pp · 88,125 words

Socialism Sucks: Two Economists Drink Their Way Through the Unfree World

by Robert Lawson and Benjamin Powell · 29 Jul 2019 · 164pp · 44,947 words

The Globalization of Inequality

by François Bourguignon · 1 Aug 2012 · 221pp · 55,901 words

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change

by Stephen R. Covey · 9 Nov 2004 · 398pp · 108,026 words

The Wake-Up Call: Why the Pandemic Has Exposed the Weakness of the West, and How to Fix It

by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge · 1 Sep 2020 · 134pp · 41,085 words

DarkMarket: Cyberthieves, Cybercops and You

by Misha Glenny · 3 Oct 2011 · 274pp · 85,557 words

Operation Chaos: The Vietnam Deserters Who Fought the CIA, the Brainwashers, and Themselves

by Matthew Sweet · 13 Feb 2018 · 493pp · 136,235 words

Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire

by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri · 1 Jan 2004 · 475pp · 149,310 words

Unhappy Union: How the Euro Crisis - and Europe - Can Be Fixed

by John Peet, Anton La Guardia and The Economist · 15 Feb 2014 · 267pp · 74,296 words

The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger

by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett · 1 Jan 2009 · 309pp · 86,909 words

Too Big to Know: Rethinking Knowledge Now That the Facts Aren't the Facts, Experts Are Everywhere, and the Smartest Person in the Room Is the Room

by David Weinberger · 14 Jul 2011 · 369pp · 80,355 words

Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion

by Gareth Stedman Jones · 24 Aug 2016 · 964pp · 296,182 words

Rethinking Camelot

by Noam Chomsky · 7 Apr 2015

Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution

by Francis Fukuyama · 1 Jan 2002 · 350pp · 96,803 words

Home Game: An Accidental Guide to Fatherhood

by Michael Lewis · 1 Jan 2009 · 113pp · 36,785 words

The Haves and the Have-Nots: A Brief and Idiosyncratic History of Global Inequality

by Branko Milanovic · 15 Dec 2010 · 251pp · 69,245 words

Shadows of Empire: The Anglosphere in British Politics

by Michael Kenny and Nick Pearce · 5 Jun 2018 · 215pp · 64,460 words

The Extreme Centre: A Warning

by Tariq Ali · 22 Jan 2015 · 160pp · 46,449 words

A Concise History of Modern India (Cambridge Concise Histories)

by Barbara D. Metcalf and Thomas R. Metcalf · 27 Sep 2006

State-Building: Governance and World Order in the 21st Century

by Francis Fukuyama · 7 Apr 2004

Lonely Planet Pocket Berlin

by Lonely Planet and Andrea Schulte-Peevers · 31 Aug 2012 · 277pp · 41,815 words

Conscience of a Conservative: A Rejection of Destructive Politics and a Return to Principle

by Jeff Flake · 31 Jul 2017 · 138pp · 43,748 words

The Global Citizen: A Guide to Creating an International Life and Career

by Elizabeth Kruempelmann · 14 Jul 2002

Speed

by Bob Gilliland and Keith Dunnavant · 319pp · 84,772 words

Pocket Berlin

by Andrea Schulte-Peevers · 15 Mar 2023 · 157pp · 37,509 words

Reaching for Utopia: Making Sense of an Age of Upheaval

by Jason Cowley · 15 Nov 2018 · 283pp · 87,166 words

Mongolia - Culture Smart!: The Essential Guide to Customs & Culture

by Alan Sanders · 1 Feb 2016 · 122pp · 37,785 words

Defending the Free Market: The Moral Case for a Free Economy

by Robert A. Sirico · 20 May 2012 · 267pp · 70,250 words

The End of the Free Market: Who Wins the War Between States and Corporations?

by Ian Bremmer · 12 May 2010 · 247pp · 68,918 words

The Secret War Between Downloading and Uploading: Tales of the Computer as Culture Machine

by Peter Lunenfeld · 31 Mar 2011 · 239pp · 56,531 words

Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks From the Stone Age to AI

by Yuval Noah Harari · 9 Sep 2024 · 566pp · 169,013 words

The Long Good Buy: Analysing Cycles in Markets

by Peter Oppenheimer · 3 May 2020 · 333pp · 76,990 words

The Library: A Fragile History

by Arthur Der Weduwen and Andrew Pettegree · 14 Oct 2021 · 457pp · 173,326 words

The End of Big: How the Internet Makes David the New Goliath

by Nicco Mele · 14 Apr 2013 · 270pp · 79,992 words

Revenge of the Tipping Point: Overstories, Superspreaders, and the Rise of Social Engineering

by Malcolm Gladwell · 1 Oct 2024 · 283pp · 85,644 words

Brexit and Ireland: The Dangers, the Opportunities, and the Inside Story of the Irish Response

by Tony Connelly · 4 Oct 2017 · 356pp · 112,271 words

The Vanishing Neighbor: The Transformation of American Community

by Marc J. Dunkelman · 3 Aug 2014 · 327pp · 88,121 words

System Error: Where Big Tech Went Wrong and How We Can Reboot

by Rob Reich, Mehran Sahami and Jeremy M. Weinstein · 6 Sep 2021

Why geography matters: three challenges facing America : climate change, the rise of China, and global terrorism

by Harm J. De Blij · 15 Nov 2007 · 481pp · 121,300 words

Making the Future: The Unipolar Imperial Moment

by Noam Chomsky · 15 Mar 2010 · 258pp · 63,367 words

The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival

by Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan · 8 Aug 2020 · 438pp · 84,256 words

Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism

by Harsha Walia · 9 Feb 2021

Obliquity: Why Our Goals Are Best Achieved Indirectly

by John Kay · 30 Apr 2010 · 237pp · 50,758 words

Moonwalking With Einstein

by Joshua Foer · 3 Mar 2011 · 329pp · 93,655 words

1946: The Making of the Modern World

by Victor Sebestyen · 30 Sep 2014 · 476pp · 144,288 words

Making Globalization Work

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 16 Sep 2006

Utopia for Realists: The Case for a Universal Basic Income, Open Borders, and a 15-Hour Workweek

by Rutger Bregman · 13 Sep 2014 · 235pp · 62,862 words

Digital Dead End: Fighting for Social Justice in the Information Age

by Virginia Eubanks · 1 Feb 2011 · 289pp · 99,936 words

Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty

by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson · 20 Mar 2012 · 547pp · 172,226 words

Democracy Incorporated

by Sheldon S. Wolin · 7 Apr 2008 · 637pp · 128,673 words

Immigration worldwide: policies, practices, and trends

by Uma Anand Segal, Doreen Elliott and Nazneen S. Mayadas · 19 Jan 2010 · 492pp · 70,082 words

Rewriting the Rules of the European Economy: An Agenda for Growth and Shared Prosperity

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 28 Jan 2020 · 408pp · 108,985 words

Nine Crises: Fifty Years of Covering the British Economy From Devaluation to Brexit

by William Keegan · 24 Jan 2019 · 309pp · 85,584 words

Britain's Europe: A Thousand Years of Conflict and Cooperation

by Brendan Simms · 27 Apr 2016 · 380pp · 116,919 words

The Last President of Europe: Emmanuel Macron's Race to Revive France and Save the World

by William Drozdiak · 27 Apr 2020 · 241pp · 75,417 words

Death of the Liberal Class

by Chris Hedges · 14 May 2010 · 422pp · 89,770 words

Mine!: How the Hidden Rules of Ownership Control Our Lives

by Michael A. Heller and James Salzman · 2 Mar 2021 · 332pp · 100,245 words

The Future of War

by Lawrence Freedman · 9 Oct 2017 · 592pp · 161,798 words

World Without Mind: The Existential Threat of Big Tech

by Franklin Foer · 31 Aug 2017 · 281pp · 71,242 words

Licence to be Bad

by Jonathan Aldred · 5 Jun 2019 · 453pp · 111,010 words

They Don't Represent Us: Reclaiming Our Democracy

by Lawrence Lessig · 5 Nov 2019 · 404pp · 115,108 words

Adam Smith: Father of Economics

by Jesse Norman · 30 Jun 2018

Into the Black: The Extraordinary Untold Story of the First Flight of the Space Shuttle Columbia and the Astronauts Who Flew Her

by Rowland White and Richard Truly · 18 Apr 2016 · 570pp · 151,609 words

The Death of Truth: Notes on Falsehood in the Age of Trump

by Michiko Kakutani · 17 Jul 2018 · 137pp · 38,925 words

Europe by Eurail 2023

by Laverne Ferguson-Kosinski and C. Darren Price · 8 Jan 2023 · 570pp · 186,017 words

Rogue State: A Guide to the World's Only Superpower

by William Blum · 31 Mar 2002

Tory Nation: The Dark Legacy of the World's Most Successful Political Party

by Samuel Earle · 3 May 2023 · 245pp · 88,158 words

The Emperor Far Away: Travels at the Edge of China

by David Eimer · 13 Aug 2014 · 316pp · 103,743 words

Last Best Hope: America in Crisis and Renewal

by George Packer · 14 Jun 2021 · 173pp · 55,328 words

Age of the City: Why Our Future Will Be Won or Lost Together

by Ian Goldin and Tom Lee-Devlin · 21 Jun 2023 · 248pp · 73,689 words

Humankind: A Hopeful History

by Rutger Bregman · 1 Jun 2020 · 578pp · 131,346 words

Unit X: How the Pentagon and Silicon Valley Are Transforming the Future of War

by Raj M. Shah and Christopher Kirchhoff · 8 Jul 2024 · 272pp · 103,638 words

Shocks, Crises, and False Alarms: How to Assess True Macroeconomic Risk

by Philipp Carlsson-Szlezak and Paul Swartz · 8 Jul 2024 · 259pp · 89,637 words

Why Aren't They Shouting?: A Banker’s Tale of Change, Computers and Perpetual Crisis

by Kevin Rodgers · 13 Jul 2016 · 318pp · 99,524 words

Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the World (Politics of Place)

by Tim Marshall · 10 Oct 2016 · 306pp · 79,537 words

The Rough Guide to Brussels 4 (Rough Guide Travel Guides)

by Dunford, Martin.; Lee, Phil; Summer, Suzy.; Dal Molin, Loik · 26 Jul 2010

The end of history and the last man

by Francis Fukuyama · 28 Feb 2006 · 446pp · 578 words

Simple Rules: How to Thrive in a Complex World

by Donald Sull and Kathleen M. Eisenhardt · 20 Apr 2015 · 294pp · 82,438 words

Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire

by Rebecca Henderson · 27 Apr 2020 · 330pp · 99,044 words

Go, Flight!: The Unsung Heroes of Mission Control, 1965-1992

by Rick Houston and J. Milt Heflin · 27 Sep 2015 · 472pp · 141,591 words

The City

by Tony Norfield · 352pp · 98,561 words

The Quantum Curators and the Fabergé Egg: A Fast Paced Portal Adventure

by Eva St. John · 23 May 2020 · 229pp · 67,752 words

The Full Catastrophe: Travels Among the New Greek Ruins

by James Angelos · 1 Jun 2015 · 278pp · 93,540 words

Unfinished Business

by Tamim Bayoumi · 405pp · 109,114 words

Hate Inc.: Why Today’s Media Makes Us Despise One Another

by Matt Taibbi · 7 Oct 2019 · 357pp · 99,456 words

City Parks

by Catie Marron

Exceptional People: How Migration Shaped Our World and Will Define Our Future

by Ian Goldin, Geoffrey Cameron and Meera Balarajan · 20 Dec 2010 · 482pp · 117,962 words

Blueprint for Revolution: How to Use Rice Pudding, Lego Men, and Other Nonviolent Techniques to Galvanize Communities, Overthrow Dictators, or Simply Change the World

by Srdja Popovic and Matthew Miller · 3 Feb 2015 · 202pp · 8,448 words

Hubris: Why Economists Failed to Predict the Crisis and How to Avoid the Next One

by Meghnad Desai · 15 Feb 2015 · 270pp · 73,485 words

Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World

by Timothy Garton Ash · 23 May 2016 · 743pp · 201,651 words

Pirates and Emperors, Old and New

by Noam Chomsky · 7 Apr 2015

The Enemy Within

by Seumas Milne · 1 Dec 1994 · 497pp · 161,742 words

Cyclopedia

by William Fotheringham · 22 Sep 2011 · 428pp · 117,419 words

At the Devil's Table: The Untold Story of the Insider Who Brought Down the Cali Cartel

by William C. Rempel · 20 Jun 2011 · 337pp · 100,765 words

The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam

by Douglas Murray · 3 May 2017 · 420pp · 126,194 words

Culture works: the political economy of culture

by Richard Maxwell · 15 Jan 2001 · 268pp · 112,708 words

Rocket Men: The Daring Odyssey of Apollo 8 and the Astronauts Who Made Man's First Journey to the Moon

by Robert Kurson · 2 Apr 2018 · 361pp · 110,905 words

Adapt: Why Success Always Starts With Failure

by Tim Harford · 1 Jun 2011 · 459pp · 103,153 words

Cybersecurity: What Everyone Needs to Know

by P. W. Singer and Allan Friedman · 3 Jan 2014 · 587pp · 117,894 words

Faster, Higher, Farther: How One of the World's Largest Automakers Committed a Massive and Stunning Fraud

by Jack Ewing · 22 May 2017 · 434pp · 114,583 words

Unelected Power: The Quest for Legitimacy in Central Banking and the Regulatory State

by Paul Tucker · 21 Apr 2018 · 920pp · 233,102 words

Inside British Intelligence

by Gordon Thomas

On Her Majesty's Nuclear Service

by Eric Thompson · 18 Apr 2018 · 379pp · 118,576 words

The Economics of Belonging: A Radical Plan to Win Back the Left Behind and Achieve Prosperity for All

by Martin Sandbu · 15 Jun 2020 · 322pp · 84,580 words

It's Our Turn to Eat

by Michela Wrong · 9 Apr 2009 · 403pp · 125,659 words

Fall: The Mysterious Life and Death of Robert Maxwell, Britain's Most Notorious Media Baron

by John Preston · 9 Feb 2021 · 374pp · 110,238 words

Poisoned Wells: The Dirty Politics of African Oil

by Nicholas Shaxson · 20 Mar 2007

The Strangest Man: The Hidden Life of Paul Dirac, Mystic of the Atom

by Graham Farmelo · 24 Aug 2009 · 1,396pp · 245,647 words

Lonely Planet Barcelona

by Isabella Noble and Regis St Louis · 15 Nov 2022 · 541pp · 135,952 words

Messing With the Enemy: Surviving in a Social Media World of Hackers, Terrorists, Russians, and Fake News

by Clint Watts · 28 May 2018 · 324pp · 96,491 words

The Human Tide: How Population Shaped the Modern World

by Paul Morland · 10 Jan 2019 · 405pp · 121,999 words

The Great Economists Ten Economists whose thinking changed the way we live-FT Publishing International (2014)

by Phil Thornton · 7 May 2014

How the World Works

by Noam Chomsky, Arthur Naiman and David Barsamian · 13 Sep 2011 · 489pp · 111,305 words

More From Less: The Surprising Story of How We Learned to Prosper Using Fewer Resources – and What Happens Next

by Andrew McAfee · 30 Sep 2019 · 372pp · 94,153 words

How to Own the World: A Plain English Guide to Thinking Globally and Investing Wisely

by Andrew Craig · 6 Sep 2015 · 305pp · 98,072 words

The Euro: How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe

by Joseph E. Stiglitz and Alex Hyde-White · 24 Oct 2016 · 515pp · 142,354 words

Lifespan: Why We Age—and Why We Don't Have To

by David A. Sinclair and Matthew D. Laplante · 9 Sep 2019

Crack-Up Capitalism: Market Radicals and the Dream of a World Without Democracy

by Quinn Slobodian · 4 Apr 2023 · 360pp · 107,124 words

The Laundromat : Inside the Panama Papers, Illicit Money Networks, and the Global Elite

by Jake Bernstein · 14 Oct 2019 · 470pp · 125,992 words

Fallen Idols: Twelve Statues That Made History

by Alex von Tunzelmann · 7 Jul 2021 · 337pp · 87,236 words

The People's Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age

by Astra Taylor · 4 Mar 2014 · 283pp · 85,824 words

Cuba: An American History

by Ada Ferrer · 6 Sep 2021 · 723pp · 211,892 words

This Is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality

by Peter Pomerantsev · 29 Jul 2019 · 240pp · 74,182 words

The Price of Everything: And the Hidden Logic of Value

by Eduardo Porter · 4 Jan 2011 · 353pp · 98,267 words

Exponential: How Accelerating Technology Is Leaving Us Behind and What to Do About It

by Azeem Azhar · 6 Sep 2021 · 447pp · 111,991 words

Barcelona

by Damien Simonis · 9 Dec 2010

The Glass Half-Empty: Debunking the Myth of Progress in the Twenty-First Century

by Rodrigo Aguilera · 10 Mar 2020 · 356pp · 106,161 words

The Rough Guide to Prague

by Humphreys, Rob

Milton Friedman: A Biography

by Lanny Ebenstein · 23 Jan 2007 · 298pp · 95,668 words

There Is Nothing for You Here: Finding Opportunity in the Twenty-First Century

by Fiona Hill · 4 Oct 2021 · 569pp · 165,510 words

Green Tyranny: Exposing the Totalitarian Roots of the Climate Industrial Complex

by Rupert Darwall · 2 Oct 2017 · 451pp · 115,720 words

Permanent Record

by Edward Snowden · 16 Sep 2019 · 324pp · 106,699 words

The Post-American World: Release 2.0

by Fareed Zakaria · 1 Jan 2008 · 344pp · 93,858 words

The New Tycoons: Inside the Trillion Dollar Private Equity Industry That Owns Everything

by Jason Kelly · 10 Sep 2012 · 274pp · 81,008 words

America in the World: A History of U.S. Diplomacy and Foreign Policy

by Robert B. Zoellick · 3 Aug 2020

Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa

by Jason Stearns · 29 Mar 2011 · 487pp · 139,297 words

McMafia: A Journey Through the Global Criminal Underworld

by Misha Glenny · 7 Apr 2008 · 487pp · 147,891 words

10% Human: How Your Body's Microbes Hold the Key to Health and Happiness

by Alanna Collen · 4 May 2015 · 372pp · 111,573 words

The Economics of Enough: How to Run the Economy as if the Future Matters

by Diane Coyle · 21 Feb 2011 · 523pp · 111,615 words

The Undercover Economist: Exposing Why the Rich Are Rich, the Poor Are Poor, and Why You Can Never Buy a Decent Used Car

by Tim Harford · 15 Mar 2006 · 389pp · 98,487 words

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

by Thomas Piketty · 10 Mar 2014 · 935pp · 267,358 words

The Future Won't Be Long

by Jarett Kobek · 15 Aug 2017 · 510pp · 138,000 words

Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt

by Michael Lewis · 30 Mar 2014 · 250pp · 87,722 words

ZeroZeroZero

by Roberto Saviano · 4 Apr 2013 · 442pp · 135,006 words

The Seventh Sense: Power, Fortune, and Survival in the Age of Networks

by Joshua Cooper Ramo · 16 May 2016 · 326pp · 103,170 words

Empire

by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri · 9 Mar 2000 · 1,015pp · 170,908 words

Small Data: The Tiny Clues That Uncover Huge Trends

by Martin Lindstrom · 23 Feb 2016 · 295pp · 89,430 words

I.O.U.: Why Everyone Owes Everyone and No One Can Pay

by John Lanchester · 14 Dec 2009 · 322pp · 77,341 words

The Profiteers

by Sally Denton · 556pp · 141,069 words

1983: Reagan, Andropov, and a World on the Brink

by Taylor Downing · 23 Apr 2018 · 400pp · 121,708 words

That Used to Be Us

by Thomas L. Friedman and Michael Mandelbaum · 1 Sep 2011 · 441pp · 136,954 words

Liars and Outliers: How Security Holds Society Together

by Bruce Schneier · 14 Feb 2012 · 503pp · 131,064 words

The Defence of the Realm

by Christopher Andrew · 2 Aug 2010 · 1,744pp · 458,385 words

Gray Day: My Undercover Mission to Expose America's First Cyber Spy

by Eric O'Neill · 1 Mar 2019 · 299pp · 88,375 words

Corporate Warriors: The Rise of the Privatized Military Industry

by Peter Warren Singer · 1 Jan 2003 · 482pp · 161,169 words

The Coming Anarchy: Shattering the Dreams of the Post Cold War

by Robert D. Kaplan · 1 Jan 1994 · 225pp · 189 words

Rogue States

by Noam Chomsky · 9 Jul 2015

Top Dog: The Science of Winning and Losing

by Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman · 19 Feb 2013 · 407pp · 109,653 words

Free World: America, Europe, and the Surprising Future of the West

by Timothy Garton Ash · 30 Jun 2004 · 329pp · 102,469 words

Blackwater: The Rise of the World's Most Powerful Mercenary Army

by Jeremy Scahill · 1 Jan 2007 · 924pp · 198,159 words

The Long Boom: A Vision for the Coming Age of Prosperity

by Peter Schwartz, Peter Leyden and Joel Hyatt · 18 Oct 2000 · 353pp · 355 words

Drowning in Oil: BP & the Reckless Pursuit of Profit

by Loren C. Steffy · 5 Nov 2010 · 305pp · 79,356 words

Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization

by Branko Milanovic · 10 Apr 2016 · 312pp · 91,835 words

Hired: Six Months Undercover in Low-Wage Britain

by James Bloodworth · 1 Mar 2018 · 256pp · 79,075 words

Who Rules the World?

by Noam Chomsky

Border: A Journey to the Edge of Europe

by Kapka Kassabova · 4 Sep 2017 · 361pp · 107,679 words

Understanding Power

by Noam Chomsky · 26 Jul 2010

Twilight of the Elites: America After Meritocracy

by Chris Hayes · 11 Jun 2012 · 285pp · 86,174 words

Creative Intelligence: Harnessing the Power to Create, Connect, and Inspire

by Bruce Nussbaum · 5 Mar 2013 · 385pp · 101,761 words

Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation and Political Warfare

by Thomas Rid

Conscious Capitalism, With a New Preface by the Authors: Liberating the Heroic Spirit of Business

by John Mackey, Rajendra Sisodia and Bill George · 7 Jan 2014 · 335pp · 104,850 words

The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution

by Francis Fukuyama · 11 Apr 2011 · 740pp · 217,139 words

A History of Future Cities

by Daniel Brook · 18 Feb 2013 · 489pp · 132,734 words

The Shifts and the Shocks: What We've Learned--And Have Still to Learn--From the Financial Crisis

by Martin Wolf · 24 Nov 2015 · 524pp · 143,993 words

Three Years in Hell: The Brexit Chronicles

by Fintan O'Toole · 5 Mar 2020 · 385pp · 121,550 words

Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1945-1956

by Anne Applebaum · 30 Oct 2012 · 934pp · 232,651 words

The Light That Failed: A Reckoning

by Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes · 31 Oct 2019 · 300pp · 87,374 words

The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information

by Frank Pasquale · 17 Nov 2014 · 320pp · 87,853 words

The Story of Work: A New History of Humankind

by Jan Lucassen · 26 Jul 2021 · 869pp · 239,167 words

The Last Kings of Shanghai: The Rival Jewish Dynasties That Helped Create Modern China

by Jonathan Kaufman · 14 Sep 2020 · 415pp · 103,801 words

A Pelican Introduction Economics: A User's Guide

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 May 2014 · 385pp · 111,807 words

Them and Us: How Immigrants and Locals Can Thrive Together

by Philippe Legrain · 14 Oct 2020 · 521pp · 110,286 words

Stuffocation

by James Wallman · 6 Dec 2013 · 296pp · 82,501 words

Console Wars: Sega, Nintendo, and the Battle That Defined a Generation

by Blake J. Harris · 12 May 2014

Trade Wars Are Class Wars: How Rising Inequality Distorts the Global Economy and Threatens International Peace

by Matthew C. Klein · 18 May 2020 · 339pp · 95,270 words

Uncharted: How to Map the Future

by Margaret Heffernan · 20 Feb 2020 · 335pp · 97,468 words

The Upside of Inequality

by Edward Conard · 1 Sep 2016 · 436pp · 98,538 words

Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics

by Richard H. Thaler · 10 May 2015 · 500pp · 145,005 words

What's Left?: How Liberals Lost Their Way

by Nick Cohen · 15 Jul 2015 · 414pp · 121,243 words

Stasiland: Stories From Behind the Berlin Wall

by Anna Funder · 19 Sep 2011

The Blue Sweater: Bridging the Gap Between Rich and Poor in an Interconnected World

by Jacqueline Novogratz · 15 Feb 2009 · 391pp · 117,984 words

Globish: How the English Language Became the World's Language

by Robert McCrum · 24 May 2010 · 325pp · 99,983 words

A Classless Society: Britain in the 1990s

by Alwyn W. Turner · 4 Sep 2013 · 1,013pp · 302,015 words

People, Power, and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 22 Apr 2019 · 462pp · 129,022 words

The Great Economists: How Their Ideas Can Help Us Today

by Linda Yueh · 15 Mar 2018 · 374pp · 113,126 words

Small Men on the Wrong Side of History: The Decline, Fall and Unlikely Return of Conservatism

by Ed West · 19 Mar 2020 · 530pp · 147,851 words

The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time

by Karl Polanyi · 27 Mar 2001 · 495pp · 138,188 words

American Kleptocracy: How the U.S. Created the World's Greatest Money Laundering Scheme in History

by Casey Michel · 23 Nov 2021 · 466pp · 116,165 words

The Identity Trap: A Story of Ideas and Power in Our Time

by Yascha Mounk · 26 Sep 2023

Money: 5,000 Years of Debt and Power

by Michel Aglietta · 23 Oct 2018 · 665pp · 146,542 words

Super Continent: The Logic of Eurasian Integration

by Kent E. Calder · 28 Apr 2019

Everyday Utopia: What 2,000 Years of Wild Experiments Can Teach Us About the Good Life

by Kristen R. Ghodsee · 16 May 2023 · 302pp · 112,390 words

Lonely Planet Cyprus

by Lonely Planet, Jessica Lee, Joe Bindloss and Josephine Quintero · 1 Feb 2018

The New Silk Roads: The Present and Future of the World

by Peter Frankopan · 14 Jun 2018 · 352pp · 80,030 words

Transcending the Cold War: Summits, Statecraft, and the Dissolution of Bipolarity in Europe, 1970–1990

by Kristina Spohr and David Reynolds · 24 Aug 2016 · 627pp · 127,613 words

Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism: And Other Arguments for Economic Independence

by Kristen R. Ghodsee · 20 Nov 2018 · 211pp · 57,759 words

Waco Rising: David Koresh, the FBI, and the Birth of America's Modern Militias

by Kevin Cook · 30 Jan 2023 · 277pp · 86,352 words

Empty Vessel: The Story of the Global Economy in One Barge

by Ian Kumekawa · 6 May 2025 · 422pp · 112,638 words

The Great Wave: The Era of Radical Disruption and the Rise of the Outsider

by Michiko Kakutani · 20 Feb 2024 · 262pp · 69,328 words

Heavy Metal: The Hard Days and Nights of the Shipyard Workers Who Build America's Supercarriers

by Michael Fabey · 13 Jun 2022 · 319pp · 102,839 words

Globalists

by Quinn Slobodian · 16 Mar 2018 · 451pp · 142,662 words

Our Dollar, Your Problem: An Insider’s View of Seven Turbulent Decades of Global Finance, and the Road Ahead

by Kenneth Rogoff · 27 Feb 2025 · 330pp · 127,791 words

Gilded Rage: Elon Musk and the Radicalization of Silicon Valley

by Jacob Silverman · 9 Oct 2025 · 312pp · 103,645 words

Berlin

by Andrea Schulte-Peevers · 20 Oct 2010 · 638pp · 156,653 words

The Age of Illusions: How America Squandered Its Cold War Victory

by Andrew J. Bacevich · 7 Jan 2020 · 254pp · 68,133 words

The Ones We've Been Waiting For: How a New Generation of Leaders Will Transform America

by Charlotte Alter · 18 Feb 2020 · 504pp · 129,087 words

Shutdown: How COVID Shook the World's Economy

by Adam Tooze · 15 Nov 2021 · 561pp · 138,158 words

Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, From the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First

by Frank Trentmann · 1 Dec 2015 · 1,213pp · 376,284 words

1989 The Berlin Wall: My Part in Its Downfall

by Peter Millar · 1 Oct 2009 · 220pp · 88,994 words

The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 10 Jun 2012 · 580pp · 168,476 words

Girlfriend in a coma

by Douglas Coupland · 19 Feb 1998

The World as It Is: A Memoir of the Obama White House

by Ben Rhodes · 4 Jun 2018 · 470pp · 148,444 words

Central Europe Travel Guide

by Lonely Planet

Connectography: Mapping the Future of Global Civilization

by Parag Khanna · 18 Apr 2016 · 497pp · 144,283 words

The End of Power: From Boardrooms to Battlefields and Churches to States, Why Being in Charge Isn’t What It Used to Be

by Moises Naim · 5 Mar 2013 · 474pp · 120,801 words

Germany

by Andrea Schulte-Peevers · 17 Oct 2010

On the Grand Trunk Road: A Journey Into South Asia

by Steve Coll · 29 Mar 2009 · 413pp · 128,093 words

The Bin Ladens: An Arabian Family in the American Century

by Steve Coll · 29 Mar 2009 · 769pp · 224,916 words

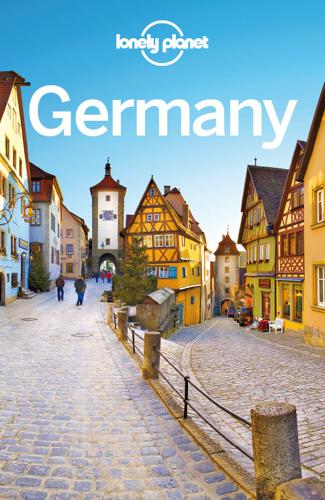

Germany Travel Guide

by Lonely Planet

Lonely Planet Eastern Europe

by Lonely Planet, Mark Baker, Tamara Sheward, Anita Isalska, Hugh McNaughtan, Lorna Parkes, Greg Bloom, Marc Di Duca, Peter Dragicevich, Tom Masters, Leonid Ragozin, Tim Richards and Simon Richmond · 30 Sep 2017

Stolen: How to Save the World From Financialisation

by Grace Blakeley · 9 Sep 2019 · 263pp · 80,594 words

The End of Growth

by Jeff Rubin · 2 Sep 2013 · 262pp · 83,548 words

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab and Peter Vanham · 27 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

Winds of Change

by Peter Hennessy · 27 Aug 2019 · 891pp · 220,950 words

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress

by Steven Pinker · 13 Feb 2018 · 1,034pp · 241,773 words

Capitalism: Money, Morals and Markets

by John Plender · 27 Jul 2015 · 355pp · 92,571 words

The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good?

by Michael J. Sandel · 9 Sep 2020 · 493pp · 98,982 words

The International Brigades: Fascism, Freedom and the Spanish Civil War

by Giles Tremlett · 14 Oct 2020 · 2,238pp · 239,238 words

Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy in the Aftermath of Crisis

by Anatole Kaletsky · 22 Jun 2010 · 484pp · 136,735 words

Antonio-s-Gun-and-Delfino-s-Dream-True-Tales-of-Mexican-Migration

by Unknown

The Euro and the Battle of Ideas

by Markus K. Brunnermeier, Harold James and Jean-Pierre Landau · 3 Aug 2016 · 586pp · 160,321 words

Civilization: The West and the Rest

by Niall Ferguson · 28 Feb 2011 · 790pp · 150,875 words

The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking and the Future of the Global Economy

by Mervyn King · 3 Mar 2016 · 464pp · 139,088 words

Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist

by Kate Raworth · 22 Mar 2017 · 403pp · 111,119 words

If Mayors Ruled the World: Dysfunctional Nations, Rising Cities

by Benjamin R. Barber · 5 Nov 2013 · 501pp · 145,943 words

Hot: Living Through the Next Fifty Years on Earth

by Mark Hertsgaard · 15 Jan 2011 · 326pp · 48,727 words

The Retreat of Western Liberalism

by Edward Luce · 20 Apr 2017 · 223pp · 58,732 words

What's Next?: Unconventional Wisdom on the Future of the World Economy

by David Hale and Lyric Hughes Hale · 23 May 2011 · 397pp · 112,034 words

To Serve God and Wal-Mart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise

by Bethany Moreton · 15 May 2009 · 391pp · 22,799 words

This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate

by Naomi Klein · 15 Sep 2014 · 829pp · 229,566 words

Year 501

by Noam Chomsky · 19 Jan 2016

The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom

by Evgeny Morozov · 16 Nov 2010 · 538pp · 141,822 words

Age of Discovery: Navigating the Risks and Rewards of Our New Renaissance

by Ian Goldin and Chris Kutarna · 23 May 2016 · 437pp · 113,173 words

Reagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold War

by Ken Adelman · 5 May 2014 · 372pp · 115,094 words

Hopes and Prospects

by Noam Chomsky · 1 Jan 2009

Grave New World: The End of Globalization, the Return of History

by Stephen D. King · 22 May 2017 · 354pp · 92,470 words

Moscow, December 25th, 1991

by Conor O'Clery · 31 Jul 2011 · 449pp · 127,440 words

Berlin 1961: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Most Dangerous Place on Earth

by Frederick Kempe · 30 Apr 2011 · 762pp · 206,865 words

Zero-Sum Future: American Power in an Age of Anxiety

by Gideon Rachman · 1 Feb 2011 · 391pp · 102,301 words

Powers and Prospects

by Noam Chomsky · 16 Sep 2015

The End of the Cold War: 1985-1991

by Robert Service · 7 Oct 2015

Fateful Triangle: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinians (Updated Edition) (South End Press Classics Series)

by Noam Chomsky · 1 Apr 1999

Dreams and Shadows: The Future of the Middle East

by Robin Wright · 28 Feb 2008 · 648pp · 165,654 words

Broke: How to Survive the Middle Class Crisis

by David Boyle · 15 Jan 2014 · 367pp · 108,689 words

Thank You for Being Late: An Optimist's Guide to Thriving in the Age of Accelerations

by Thomas L. Friedman · 22 Nov 2016 · 602pp · 177,874 words

The Last Empire: The Final Days of the Soviet Union

by Serhii Plokhy · 12 May 2014

The Secret Lives of Buildings: From the Ruins of the Parthenon to the Vegas Strip in Thirteen Stories

by Edward Hollis · 10 Nov 2009 · 444pp · 107,664 words

Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy

by Francis Fukuyama · 29 Sep 2014 · 828pp · 232,188 words

Jihad vs. McWorld: Terrorism's Challenge to Democracy

by Benjamin Barber · 20 Apr 2010 · 454pp · 139,350 words

The Internet Is Not the Answer

by Andrew Keen · 5 Jan 2015 · 361pp · 81,068 words

To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism

by Evgeny Morozov · 15 Nov 2013 · 606pp · 157,120 words

The Marshall Plan: Dawn of the Cold War

by Benn Steil · 13 Feb 2018 · 913pp · 219,078 words

Chinese Spies: From Chairman Mao to Xi Jinping

by Roger Faligot · 30 Jun 2019 · 615pp · 187,426 words

The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11

by Lawrence Wright · 26 Sep 2006 · 604pp · 177,329 words

Baghdad at Sunrise: A Brigade Commander's War in Iraq

by Peter R. Mansoor, Donald Kagan and Frederick Kagan · 31 Aug 2009 · 423pp · 126,375 words

The Jakarta Method: Washington's Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program That Shaped Our World

by Vincent Bevins · 18 May 2020 · 393pp · 115,178 words

Dark Towers: Deutsche Bank, Donald Trump, and an Epic Trail of Destruction

by David Enrich · 18 Feb 2020 · 399pp · 114,787 words

Hunger: The Oldest Problem

by Martin Caparros · 14 Jan 2020 · 684pp · 212,486 words

When the Money Runs Out: The End of Western Affluence

by Stephen D. King · 17 Jun 2013 · 324pp · 90,253 words

Why It's Still Kicking Off Everywhere: The New Global Revolutions

by Paul Mason · 30 Sep 2013 · 357pp · 99,684 words

The Cold War: A World History

by Odd Arne Westad · 4 Sep 2017 · 846pp · 250,145 words

Confessions of an Eco-Sinner: Tracking Down the Sources of My Stuff

by Fred Pearce · 30 Sep 2009 · 407pp · 121,458 words

When the Iron Lady Ruled Britain

by Robert Chesshyre · 15 Jan 2012 · 434pp · 150,773 words

Open: The Story of Human Progress

by Johan Norberg · 14 Sep 2020 · 505pp · 138,917 words

The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Competition

by Jonathan Tepper · 20 Nov 2018 · 417pp · 97,577 words

Roads to Berlin

by Cees Nooteboom and Laura Watkinson · 2 Jan 1990 · 378pp · 120,490 words

The Fire and the Darkness: The Bombing of Dresden, 1945

by Sinclair McKay

Losing Control: The Emerging Threats to Western Prosperity

by Stephen D. King · 14 Jun 2010 · 561pp · 87,892 words

Overbooked: The Exploding Business of Travel and Tourism

by Elizabeth Becker · 16 Apr 2013 · 570pp · 158,139 words

Berlin: Life and Death in the City at the Center of the World

by Sinclair McKay · 22 Aug 2022 · 559pp · 164,795 words

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab · 7 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century

by P. W. Singer · 1 Jan 2010 · 797pp · 227,399 words

Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration and the Future of White Majorities

by Eric Kaufmann · 24 Oct 2018 · 691pp · 203,236 words

Live and Let Spy: BRIXMIS - the Last Cold War Mission

by Steve Gibson · 2 Mar 2012 · 377pp · 121,996 words

After the Fall: Being American in the World We've Made

by Ben Rhodes · 1 Jun 2021 · 342pp · 114,118 words

The Lighthouse of Stalingrad: The Hidden Truth at the Centre of WWII's Greatest Battle

by Iain MacGregor · 27 Jul 2022 · 729pp · 111,640 words

Liberalism at Large: The World According to the Economist

by Alex Zevin · 12 Nov 2019 · 767pp · 208,933 words

Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism

by Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart · 31 Dec 2018

The Powerful and the Damned: Private Diaries in Turbulent Times

by Lionel Barber · 5 Nov 2020

Digital Empires: The Global Battle to Regulate Technology

by Anu Bradford · 25 Sep 2023 · 898pp · 236,779 words

Red Platoon: A True Story of American Valor

by Clinton Romesha · 2 May 2016 · 400pp · 121,378 words

Hegemony or Survival: America's Quest for Global Dominance

by Noam Chomsky · 1 Jan 2003 · 351pp · 96,780 words

Capitalism and Its Critics: A History: From the Industrial Revolution to AI

by John Cassidy · 12 May 2025 · 774pp · 238,244 words

Enemies and Neighbours: Arabs and Jews in Palestine and Israel, 1917-2017

by Ian Black · 2 Nov 2017 · 674pp · 201,633 words

Can Democracy Work?: A Short History of a Radical Idea, From Ancient Athens to Our World

by James Miller · 17 Sep 2018 · 370pp · 99,312 words

Limitless: The Federal Reserve Takes on a New Age of Crisis

by Jeanna Smialek · 27 Feb 2023 · 601pp · 135,202 words

The Rough Guide to Paris

by Rough Guides · 1 May 2023 · 688pp · 190,793 words

What Would the Great Economists Do?: How Twelve Brilliant Minds Would Solve Today's Biggest Problems

by Linda Yueh · 4 Jun 2018 · 453pp · 117,893 words

The River of Lost Footsteps

by Thant Myint-U · 14 Apr 2006

Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts, and the Death of Freedom

by Grace Blakeley · 11 Mar 2024 · 371pp · 137,268 words

Adriatic: A Concert of Civilizations at the End of the Modern Age

by Robert D. Kaplan · 11 Apr 2022 · 500pp · 115,119 words

Zbig: The Life of Zbigniew Brzezinski, America's Great Power Prophet

by Edward Luce · 13 May 2025 · 612pp · 235,188 words

Apple in China: The Capture of the World's Greatest Company

by Patrick McGee · 13 May 2025 · 377pp · 138,306 words

Bosnia and Herzegovina

by Tim. Clancy · 15 Mar 2022 · 716pp · 209,067 words

The Dream of Europe: Travels in the Twenty-First Century

by Geert Mak · 27 Oct 2021 · 722pp · 223,701 words

Arguing With Zombies: Economics, Politics, and the Fight for a Better Future

by Paul Krugman · 28 Jan 2020 · 446pp · 117,660 words

Beyond the Wall: East Germany, 1949-1990

by Katja Hoyer · 5 Apr 2023

Eastern USA

by Lonely Planet

Roller-Coaster: Europe, 1950-2017

by Ian Kershaw · 29 Aug 2018 · 736pp · 233,366 words

Pivotal Decade: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the Seventies

by Judith Stein · 30 Apr 2010 · 497pp · 143,175 words

Aftershocks: Pandemic Politics and the End of the Old International Order

by Colin Kahl and Thomas Wright · 23 Aug 2021 · 652pp · 172,428 words

In FED We Trust: Ben Bernanke's War on the Great Panic

by David Wessel · 3 Aug 2009 · 350pp · 109,220 words

Investment: A History

by Norton Reamer and Jesse Downing · 19 Feb 2016

Vanished Kingdoms: The History of Half-Forgotten Europe

by Norman Davies · 27 Sep 2011

More Money Than God: Hedge Funds and the Making of a New Elite

by Sebastian Mallaby · 9 Jun 2010 · 584pp · 187,436 words

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World

by Daniel Yergin · 14 May 2011 · 1,373pp · 300,577 words

Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion ofSafety

by Eric Schlosser · 16 Sep 2013 · 956pp · 267,746 words

The Gamble: General David Petraeus and the American Military Adventure in Iraq, 2006-2008

by Thomas E. Ricks · 14 Oct 2009 · 509pp · 153,061 words

Endless Money: The Moral Hazards of Socialism

by William Baker and Addison Wiggin · 2 Nov 2009 · 444pp · 151,136 words

Paper Promises

by Philip Coggan · 1 Dec 2011 · 376pp · 109,092 words

A Fraction of the Whole

by Steve Toltz · 12 Feb 2008 · 773pp · 220,140 words

Daemon

by Daniel Suarez · 1 Dec 2006 · 562pp · 146,544 words

The Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do About Them

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 15 Mar 2015 · 409pp · 125,611 words

The Road Not Taken: Edward Lansdale and the American Tragedy in Vietnam

by Max Boot · 9 Jan 2018 · 972pp · 259,764 words

City: A Guidebook for the Urban Age

by P. D. Smith · 19 Jun 2012

Listen, Liberal: Or, What Ever Happened to the Party of the People?

by Thomas Frank · 15 Mar 2016 · 316pp · 87,486 words

When China Rules the World: The End of the Western World and the Rise of the Middle Kingdom

by Martin Jacques · 12 Nov 2009 · 859pp · 204,092 words

The Pentagon's Brain: An Uncensored History of DARPA, America's Top-Secret Military Research Agency

by Annie Jacobsen · 14 Sep 2015 · 558pp · 164,627 words

The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World (Hardback) - Common

by Alan Greenspan · 14 Jun 2007

Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2011

by Steve Coll · 23 Feb 2004 · 956pp · 288,981 words

Vanished Kingdoms: The Rise and Fall of States and Nations

by Norman Davies · 30 Sep 2009 · 1,309pp · 300,991 words

Currency Wars: The Making of the Next Gobal Crisis

by James Rickards · 10 Nov 2011 · 381pp · 101,559 words

The Sovereign Individual: How to Survive and Thrive During the Collapse of the Welfare State

by James Dale Davidson and William Rees-Mogg · 3 Feb 1997 · 582pp · 160,693 words

Adaptive Markets: Financial Evolution at the Speed of Thought

by Andrew W. Lo · 3 Apr 2017 · 733pp · 179,391 words

The Berlin Wall: A World Divided, 1961-1989

by Frederick Taylor · 26 May 2008 · 564pp · 182,946 words

Atlas Obscura: An Explorer's Guide to the World's Hidden Wonders

by Joshua Foer, Dylan Thuras and Ella Morton · 19 Sep 2016 · 1,048pp · 187,324 words

Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World

by Adam Tooze · 31 Jul 2018 · 1,066pp · 273,703 words

Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown

by Philip Mirowski · 24 Jun 2013 · 662pp · 180,546 words

Capitalism in America: A History

by Adrian Wooldridge and Alan Greenspan · 15 Oct 2018 · 585pp · 151,239 words

EuroTragedy: A Drama in Nine Acts

by Ashoka Mody · 7 May 2018

Days of Fire: Bush and Cheney in the White House

by Peter Baker · 21 Oct 2013

Lonely Planet's Best of USA

by Lonely Planet

The Atlantic and Its Enemies: A History of the Cold War

by Norman Stone · 15 Feb 2010 · 851pp · 247,711 words

The Road to Ruin: The Global Elites' Secret Plan for the Next Financial Crisis

by James Rickards · 15 Nov 2016 · 354pp · 105,322 words

The Cold War: Stories From the Big Freeze

by Bridget Kendall · 14 May 2017 · 559pp · 178,279 words

The Collapse: The Accidental Opening of the Berlin Wall

by Mary Elise Sarotte · 6 Oct 2014 · 587pp · 119,432 words

Not Working: Where Have All the Good Jobs Gone?

by David G. Blanchflower · 12 Apr 2021 · 566pp · 160,453 words

Gorbachev: His Life and Times

by William Taubman

Money: The True Story of a Made-Up Thing

by Jacob Goldstein · 14 Aug 2020 · 199pp · 64,272 words

Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power

by Steve Coll · 30 Apr 2012 · 944pp · 243,883 words

The Coming Plague: Newly Emerging Diseases in a World Out of Balance

by Laurie Garrett · 31 Oct 1994 · 1,293pp · 357,735 words

From Peoples into Nations

by John Connelly · 11 Nov 2019

Betrayal of Trust: The Collapse of Global Public Health

by Laurie Garrett · 15 Feb 2000

Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right

by Jane Mayer · 19 Jan 2016 · 558pp · 168,179 words

The Rough Guide to France (Travel Guide eBook)

by Rough Guides · 1 Aug 2019 · 1,994pp · 548,894 words

The Pentagon: A History

by Steve Vogel · 26 May 2008 · 760pp · 218,087 words

Post Wall: Rebuilding the World After 1989

by Kristina Spohr · 23 Sep 2019 · 1,123pp · 328,357 words

The Passenger: Berlin

by The Passenger · 8 Jun 2021 · 199pp · 63,724 words

The Rough Guide to Korea

by Rough Guides · 24 Sep 2018 · 712pp · 199,112 words

The Gods of New York: Egotists, Idealists, Opportunists, and the Birth of the Modern City: 1986-1990

by Jonathan Mahler · 11 Aug 2025 · 559pp · 164,804 words

Chokepoints: American Power in the Age of Economic Warfare

by Edward Fishman · 25 Feb 2025 · 884pp · 221,861 words

Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post-Cold War Stalemate

by M. E. Sarotte · 29 Nov 2021 · 791pp · 222,536 words

Tunnel 29

by Helena Merriman · 24 Aug 2021 · 333pp · 101,677 words

The Rise and Fall of Nations: Forces of Change in the Post-Crisis World

by Ruchir Sharma · 5 Jun 2016 · 566pp · 163,322 words

The End of Wall Street

by Roger Lowenstein · 15 Jan 2010 · 460pp · 122,556 words

Too big to fail: the inside story of how Wall Street and Washington fought to save the financial system from crisis--and themselves

by Andrew Ross Sorkin · 15 Oct 2009 · 351pp · 102,379 words

USA Travel Guide

by Lonely, Planet

Confessions of a Wall Street Analyst: A True Story of Inside Information and Corruption in the Stock Market

by Daniel Reingold and Jennifer Reingold · 1 Jan 2006 · 506pp · 146,607 words

Crisis Economics: A Crash Course in the Future of Finance

by Nouriel Roubini and Stephen Mihm · 10 May 2010 · 491pp · 131,769 words