Filter Bubble

description: intellectual isolation involving search engines

126 results

The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding From You

by

Eli Pariser

Published 11 May 2011

Together, these engines create a unique universe of information for each of us—what I’ve come to call a filter bubble—which fundamentally alters the way we encounter ideas and information. Of course, to some extent we’ve always consumed media that appealed to our interests and avocations and ignored much of the rest. But the filter bubble introduces three dynamics we’ve never dealt with before. First, you’re alone in it. A cable channel that caters to a narrow interest (say, golf) has other viewers with whom you share a frame of reference. But you’re the only person in your bubble. In an age when shared information is the bedrock of shared experience, the filter bubble is a centrifugal force, pulling us apart.

…

We can now begin to see how the filter bubble is actually working, where it’s falling short, and what that means for our daily lives and our society. Every technology has an interface, Stanford law professor Ryan Calo told me, a place where you end and the technology begins. And when the technology’s job is to show you the world, it ends up sitting between you and reality, like a camera lens. That’s a powerful position, Calo says. “There are lots of ways for it to skew your perception of the world.” And that’s precisely what the filter bubble does. THE FILTER BUBBLE’S costs are both personal and cultural.

…

Personalization can get in the way of creativity and innovation in three ways. First, the filter bubble artificially limits the size of our “solution horizon”—the mental space in which we search for solutions to problems. Second, the information environment inside the filter bubble will tend to lack some of the key traits that spur creativity. Creativity is a context-dependent trait: We’re more likely to come up with new ideas in some environments than in others; the contexts that filtering creates aren’t the ones best suited to creative thinking. Finally, the filter bubble encourages a more passive approach to acquiring information, which is at odds with the kind of exploration that leads to discovery.

Zucked: Waking Up to the Facebook Catastrophe

by

Roger McNamee

Published 1 Jan 2019

Giving users what they want sounds like a great idea, but it has at least one unfortunate by-product: filter bubbles. There is a high correlation between the presence of filter bubbles and polarization. To be clear, I am not suggesting that filter bubbles create polarization, but I believe they have a negative impact on public discourse and politics because filter bubbles isolate the people stuck in them. Filter bubbles exist outside Facebook and Google, but gains in attention for Facebook and Google are increasing the influence of their filter bubbles relative to others. Everyone on Facebook has friends and family, but many are also members of Groups.

…

And yet people believed it, one so deeply that he, in his own words, “self-investigated it” and fired three bullets into the pizza parlor. How can that happen? Filter bubbles. What differentiates filter bubbles from normal group activity is intellectual isolation. Filter bubbles exist wherever people are surrounded by people who share the same beliefs and where there is a way to keep out ideas that are inconsistent with those beliefs. They prey on trust and amplify it. They can happen on television when the content is ideologically extreme. Platforms have little incentive to eliminate filter bubbles because they improve metrics that matter: time on site, engagement, sharing. They can create the illusion of consensus where none exists.

…

At the time I did not see a way for me to act on Eli’s insight at Facebook. I no longer had regular contact with Zuck, much less inside information. I was not up to speed on the engineering priorities that had created filter bubbles or about plans for monetizing them. But Eli’s talk percolated in my mind. There was no good way to spin filter bubbles. All I could do was hope that Zuck and Sheryl would have the sense not to use them in ways that would harm users. (You can listen to Eli Pariser’s “Beware Online ‘Filter Bubbles’” talk for yourself on TED.com.) Meanwhile, Facebook marched on. Google introduced its own social network, Google+, in June 2011, with considerable fanfare.

Algospeak: How Social Media Is Transforming the Future of Language

by

Adam Aleksic

Published 15 Jul 2025

Our past online behavior influences what we’ll see online in the future; in this sense, we’re really the ones “building” our FYPs ourselves. This phenomenon is called a filter bubble, after a 2011 book of the same name. Once the algorithm starts to “know you” by identifying your interests, it will filter out certain information and prioritize whatever you’re most likely to engage with. Eventually, however, you’ll find yourself in an echo chamber—an environment that only reinforces your existing views. Filter bubbles and echo chambers are usually viewed negatively for their role in propagating fake news and algorithmic radicalization, but literally any in-group has its own social media filter bubble. K-pop stans are disproportionately prioritized for K-pop content recommendations, meaning that other content is necessarily filtered out.

…

Each additional video normalized the phrase for its audience. Algorithms push trends outside filter bubbles when they have potential to build community across their user base. People like fads because they feel cool; they’re seen as exciting social customs within the in-group of popular culture. When a platform like TikTok is the source of these trends, it creates a sense of cutting-edge exclusivity in the greater TikTok-speak filter bubble that everyone wants to be a part of. But because the boundaries of filter bubbles are fuzzy, words and trends eventually leak out of social media echo chambers to other platforms and then the English language at large.

…

And it wasn’t just me: Many other academic creators would get the same comments, as if all our intellectual curiosities were reducible to autistic hyperfixations. In this sense, the word “acoustic” started out as an in-joke for the autistic community on TikTok, which had over time built up a safe space in their fairly large filter bubble. Many autistic creators used the word to lightheartedly poke fun at their reality and bond with others in their online community. However, once the word became a meme, it was able to escape the autistic filter bubble to reach the larger TikTok community. Suddenly it was being used by people outside the autistic in-group, and many of these people began using it negatively. Even those who meant it only as an innocent goof inadvertently ended up contributing to the word’s pejoration by normalizing the meme’s use and perpetuating reductive stereotypes about autism.

The Science of Hate: How Prejudice Becomes Hate and What We Can Do to Stop It

by

Matthew Williams

Published 23 Mar 2021

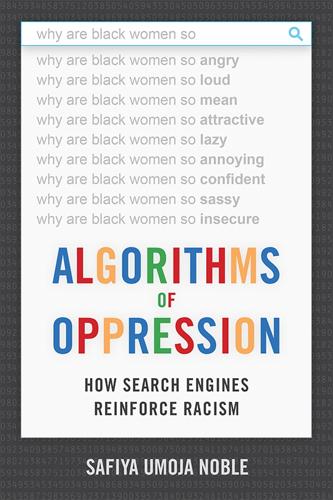

The tactic of piggy-backing on a mainstream news item to push an alt- or far-right agenda has resulted in some figures becoming YouTube stars, including Infowars’ Paul Joseph Watson. Extreme filter bubbles Right-wing political and far-right figures are known to use online filter bubbles to drum up support for their campaigns. Columbia University Professor Jonathan Albright was one of the first scientists to map the alt-right ‘fake news’ filter bubble, identifying where links to the sites were being shared. He found thousands of web-pages and millions of links spread over not only Facebook, YouTube and Twitter but also the New York Times, Washington Post and many other mainstream sites.7 This filter bubble was occupied not solely by alt-right ‘keyboard warriors’, but also major political figures, and rising international stars in the alt-right movement.

…

But the use of new ‘deep learning’ technology that is informed by billions of user behaviours a day means extreme videos will continue to be recommended if they are popular with site visitors. Filter bubbles and our bias Research on internet ‘filter bubbles’, often used interchangeably with the term ‘echo chambers’,§ has established that partisan information sources are amplified in online networks of like-minded social media users, where they go largely unchallenged due to ranking algorithms filtering out any challenging posts.9 Data science shows these filter bubbles are resilient accelerators of prejudice, reinforcing and amplifying extreme viewpoints on both sides of the spectrum.

…

Looking at over half a million tweets covering the issues of gun control, same-sex marriage and climate change, New York University’s Social Perception and Evaluation Lab found that hateful posts related to these issues increased retweeting within filter bubbles, but not between them. The lack of inter-filter bubble retweeting is facilitated by Twitter’s ‘timeline’ algorithm which prioritises content from the accounts that users most frequently engage with (via retweeting or liking). Given that these behaviours are highly biased towards accounts that share users’ views, exposure to challenging content is minimised by the algorithm. Filter bubbles therefore become further entrenched via a form of online confirmation bias, facilitated by posts and reposts that contain emotional content in line with held views on deeply moral issues.10 It therefore seems likely that at points in time when such issues come to the fore, say during court cases, political votes or following a school shooting, occupants of filter bubbles (likely to be a significant number of us who don’t sit on the fence) hunker down and polarise the debate.

Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism Is Turning the Internet Against Democracy

by

Robert W. McChesney

Published 5 Mar 2013

Madrigal, “I’m Being Followed.” 182. Turow, Daily You, 69, 118–22. 183. Madrigal, “I’m Being Followed.” 184. Pariser, Filter Bubble, 49. 185. Alan D. Mutter, “Retailers Are Routing Around the Media,” Reflections of a Newsosaur, Mar. 13, 2012, newsosaur.blogspot.com/2012/03/retailers-are-routing-around-media.html. 186. “Mad Men Are Watching You.” 187. Turow, Daily You, 159. 188. Pariser, Filter Bubble, 120–21. 189. “The All-Telling Eye,” The Economist, Oct. 22, 2011, 100–101. 190. Pariser, Filter Bubble, 120–21. 191. Alan D. Mutter, “Newspaper Digital Ad Share Hits All-Time Low,” Reflections of a Newsosaur, Apr. 23, 2012, newsosaur.blogspot.com/2012/04/newspaper-digital-ad-share-hits-all.html. 192.

…

It seems to me that even if we could network all the potential aliens in the galaxy—quadrillions of them, perhaps—and get each of them to contribute some seconds to a physics wiki, we would not replicate the achievements of even one mediocre physicist, much less a great one.”32 In his 2011 book, The Filter Bubble, Eli Pariser argues that because of the way Google and social media have evolved, Internet users are increasingly and mostly unknowingly led into a personalized world that reinforces their known preferences. This “filter bubble” each of us resides in undermines the common ground needed for community and democratic politics; it also eliminates “‘meaning threats,’ the confusing, unsettling occurrences that fuel our desire to understand and acquire new ideas.”

…

Acxiom combines extensive offline data with online data. See Natasha Singer, “A Data Giant Is Mapping, and Sharing, the Consumer Genome,” New York Times, Sunday Business Section, June 17, 2012, 1, 8. How comprehensive is their data set? In The Filter Bubble, 42–43, Pariser writes about how the Bush White House discovered that Acxiom had more data on eleven of the nineteen 9-11 hijackers than the entire U.S. government did. 126. Pariser, Filter Bubble, 7. See also Noam Cohen, “It’s Tracking Your Every Move and You May Not Even Know It,” New York Times, Mar. 26, 2011, A1, A3. 127. Peter Maass and Megha Rajagopalan, “That’s No Phone, That’s My Tracker,” New York Times, July 13, 2012. 128.

Outnumbered: From Facebook and Google to Fake News and Filter-Bubbles – the Algorithms That Control Our Lives

by

David Sumpter

Published 18 Jun 2018

Start on a conservative page then 20 clicks later you will probably still be reading conservative material. Each set of bloggers had created their own world, within which their views reverberated. Filter bubbles came later and are still developing. The difference between ‘filtered’ and ‘echoed’ cavities lies in whether they are created by algorithms or by people. While the bloggers chose the links to different blogs, algorithms based on our likes, our web searches and our browsing history do not involve an active choice on our part. It is these algorithms that can potentially create a filter bubble.1 Each action you make in your web browser is used to decide what to show you next. Whenever you share an article from, for example, the Guardian newspaper, Facebook updates its databases to reflect the fact that you are interested in the Guardian.

…

C., Haddadi, H. and Seto, M. C. 2016. ‘A first look at user activity on Tinder.’ Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM), 2016 IEEE/ACM International Conference pp. 461–6. IEEE. Chapter 11 : Bubbling Up 1 In his book and TED Talk on the filter bubble, Eli Pariser revealed the extent to which our online activities are personalised. Pariser, Eli. 2011. The Filter Bubble: How the new personalized web is changing what we read and how we think. Penguin. Google, Facebook and other big Internet companies store data documenting the choices we make when we browse online and then use it to decide what to show us in the future. 2 https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2016/04/news-feed-fyi-from-f8-how-news-feed-works 3 www.techcrunch.com/2016/09/06/ultimate-guide-to-the-news-feed 4 In the model, the probability a user chooses the Guardian at time t is equal to where G(t) is the number of times the user has already chosen the Guardian and T(t) is the number of times the user has chosen the Telegraph.

…

During the months that followed my visit to Google in May 2016, I started to see a new type of maths story in the newspapers. An uncertainty was spreading across Europe and the US. Google’s search engine was making racist autocomplete suggestions; Twitterbots were spreading fake news; Stephen Hawking was worried about artificial intelligence; far-right groups were living in algorithmically created filter-bubbles; Facebook was measuring our personalities, and these were being exploited to target voters. One after another, the stories of the dangers of algorithms accumulated. Even the mathematicians’ ability to make predictions was called into question as statistical models got both Brexit and Trump wrong.

The Death of Truth: Notes on Falsehood in the Age of Trump

by

Michiko Kakutani

Published 17 Jul 2018

“binary tribal world”: Sykes, “How the Right Lost Its Mind and Embraced Donald Trump”; Sykes, “Charlie Sykes on Where the Right Went Wrong.” “In the new Right media culture”: Charles Sykes, How the Right Lost Its Mind (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2017), 180. “With Google personalized”: Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You (New York: Penguin Press, 2011), 3. “an endless you-loop”: Ibid., 16. “If algorithms are going to curate”: Eli Pariser, “Beware Online ‘Filter Bubbles,’ ” TED2011, ted.com. 7. ATTENTION DEFICIT “When you want to know”: William Gibson, Zero History (New York: Putnam, 2010), 212. Tim Berners-Lee: “History of the Web: Sir Tim Berners-Lee,” World Wide Web Foundation.

…

What’s alarming to the contemporary reader is that Arendt’s words increasingly sound less like a dispatch from another century than a chilling mirror of the political and cultural landscape we inhabit today—a world in which fake news and lies are pumped out in industrial volume by Russian troll factories, emitted in an endless stream from the mouth and Twitter feed of the president of the United States, and sent flying across the world through social media accounts at lightning speed. Nationalism, tribalism, dislocation, fears of social change, and the hatred of outsiders are on the rise again as people, locked in their partisan silos and filter bubbles, are losing a sense of shared reality and the ability to communicate across social and sectarian lines. This is not to draw a direct analogy between today’s circumstances and the overwhelming horrors of the World War II era but to look at some of the conditions and attitudes—what Margaret Atwood has called the “danger flags” in Orwell’s 1984 and Animal Farm—that make a people susceptible to demagoguery and political manipulation, and nations easy prey for would-be autocrats.

…

Part of the problem is an “asymmetry of passion” on social media: while most people won’t devote hours to writing posts that reinforce the obvious, DiResta says, “passionate truthers and extremists produce copious amounts of content in their commitment to ‘wake up the sheeple.’ ” Recommendation engines, she adds, help connect conspiracy theorists with one another to the point that “we are long past merely partisan filter bubbles and well into the realm of siloed communities that experience their own reality and operate with their own facts.” At this point, she concludes, “the Internet doesn’t just reflect reality anymore; it shapes it.” 5 THE CO-OPTING OF LANGUAGE Without clear language, there is no standard of truth.

Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation

by

Byrne Hobart

and

Tobias Huber

Published 29 Oct 2024

The believers may get certain details wrong, but if they put enough resources to work on behalf of their vision, they just might attain it—or create something unexpected but still extraordinarily valuable. Even filter bubbles are capable of creating positive feedback loops. On the one hand, they can describe toxic circumstances, such as severe political partisanship. But a filter bubble can also be an environment that leads to the pursuit of new ideas, despite widespread beliefs that they won’t work. Yes, QAnon exists in a filter bubble, but so did Moderna when it rejected the consensus that an mRNA vaccine was impractical in the short term. The sheer volume of information in the world means that we need some kind of filter bubble just to keep things coherent. The real question is whether we’re filtering out good information or bad.

…

As mechanisms that stimulate collective risk-taking, nurture extreme enthusiasm and commitment, and excessively fund trial-and-error innovation, bubbles are uniquely suited to incubate and accelerate future technologies that can break through stagnation and accelerate growth. A taxonomy of bubbles: Speculative versus filter bubbles Looking at bubbles more closely, we can differentiate between two kinds of bubbles, although they are less distinct than they might initially seem. One kind, the classic speculative financial bubble, involves speculators egging one another on, pushing prices higher and higher, until the only justification for asset prices is the expectation that someone else will be willing to pay even more. The other kind of bubble is a filter bubble. Participants in filter bubbles wall themselves off from opinions they disagree with and become increasingly convinced that their viewpoints reflect the one true way to understand the world.

…

Participants in filter bubbles wall themselves off from opinions they disagree with and become increasingly convinced that their viewpoints reflect the one true way to understand the world. Filter bubbles are generally seen as dangerous; indeed, they can be a source of conspiracy theories, misinformation, and pathological behavior. But they also represent a filtering out of the noise that can distract people from their mission. These two phenomena, while distinct, have a deep commonality: Each encompasses a belief system oriented toward self-reference and self-fulfillment. Consider a more generous interpretation of the financial bubble as a bet on a particular version of the future, especially one that differs meaningfully from the present.

The End of Big: How the Internet Makes David the New Goliath

by

Nicco Mele

Published 14 Apr 2013

I chuckled—it was a surprise, and I’m pretty sure my distinguished “friend” had no idea that the “Social Reader” was reporting back his every click to people like me. The Filter Bubble Entertainment consumption within our new social networking life also increasingly threatens to render us more isolated from one another. In the past, every American watched one of three television channels and read a daily newspaper, even if only for sports scores and coupons. A big, shared public sphere existed in which politicians, policy makers, leaders, and public intellectuals could argue and debate—what we commonly call the court of public opinion. By contrast, with the End of Big we inhabit a “filter bubble” in which our digital media sources—primarily Google and Facebook—serve up content based on what they think we want to read.32 Even your newsfeed on Facebook is algorithmically engineered to give you the material you’re most likely to click on, creating a perverse kind of digital narcissism, always serving you up the updates you want most.

…

Right now, we already have all the fracturing we can take—thanks to cultural trends associated with radical connectivity. Our former sense of citizenship, of belonging to a larger commonwealth, has given way to the “filter bubble” we now inhabit, in which our digital media sources serve up content based on what they think we want to read, creating a perverse kind of digital narcissism. Eli Pariser opens his book The Filter Bubble by describing two friends with similar demographic profiles who each google “BP” in the midst of the oil company’s disastrous Gulf of Mexico oil spill. One of his friends gets stock quotes and links to the company’s annual report; the other gets news articles about the spill and environmental activist alerts.

…

By contrast, with the End of Big we inhabit a “filter bubble” in which our digital media sources—primarily Google and Facebook—serve up content based on what they think we want to read.32 Even your newsfeed on Facebook is algorithmically engineered to give you the material you’re most likely to click on, creating a perverse kind of digital narcissism, always serving you up the updates you want most. Nicholas Negroponte called it the “Daily Me,” but it was Eli Pariser who coined the term “filter bubble” in his book of the same name.33 The danger of the personalization of entertainment becomes clear when we remember entertainment’s traditional social functions. We need quality entertainment not just because it’s fun but also because it brings us together as a democratic society. This is one of the few areas of life where we share a common bond—and it’s rapidly going away.

The Hype Machine: How Social Media Disrupts Our Elections, Our Economy, and Our Health--And How We Must Adapt

by

Sinan Aral

Published 14 Sep 2020

Second, algorithmic curation caused a filter bubble that significantly reduced news diversity. Readers who came back to the website multiple times were randomly assigned to the algorithm or to the humans each time. When they were assigned to the algorithm, the filter bubble set in, and they read more narrowly. When they were assigned to the page edited by humans, they read more widely. Third, algorithmic curation didn’t just narrow readers’ options for diverse content, it caused their reading choices to narrow as well. In other words, the filter bubble was not limited to the fourth slot in the newsfeed—it spilled over into consumption choices more generally.

…

In contrast, what it means to be a Democrat or a Republican has become more homogenized within the two parties. Finally, Levy found that Facebook’s newsfeed algorithm does create a filter bubble. The algorithm is less likely to supply people with news that runs counter to their preexisting attitudes. Even though the experiment inspired people to read opposing viewpoints, Facebook’s algorithm continued to supply them with content that leaned toward their prior political views despite their having subscribed to counterattitudinal sources. Those who claim the Hype Machine is polarizing argue that it creates filter bubbles that in turn polarize us. While no hard evidence directly confirms or denies the Hype Machine’s role in polarization, evidence from multiple experimental studies shows that the machine’s recommendation algorithms create filter bubbles of polarized content consumption.

…

mod=article_inline; Aaron Zitner and Dante Chinni, “Democrats and Republicans Live in Different Worlds,” Wall Street Journal, September 20, 2019. partisans also select into right- or left-leaning media audiences: Kevin Arceneaux and Martin Johnson, Changing Minds or Changing Channels? Partisan News in an Age of Choice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). “filter bubbles” of polarized content: Cass R. Sunstein, Republic.com (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001); Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You (London: Penguin UK, 2011). Some studies find small increases in polarization with Internet use: Yphtach Lelkes, Gaurav Sood, and Shanto Iyengar, “The Hostile Audience: The Effect of Access to Broadband Internet on Partisan Affect,” American Journal of Political Science 61, no. 1 (2017): 5–20.

You Are What You Read

by

Jodie Jackson

Published 3 Apr 2019

This personalisation of the news is not unique to Yahoo; many other news organisations have been doing the same in a bid to build audience engagement. Eli Pariser, activist and chief executive of Upworthy, termed this ‘the filter bubble’. He describes it as ‘your own personal, unique universe of information that you live in online’.10 Eli points out that although this digital universe is controlled for you, it is not created by you – you don’t decide what enters your filter bubble and you don’t see what gets left out. The ‘give them what they want’ mentality the news industry has pushed through social media ends up inflating our filter bubble rather than bursting it. In our modern consumer environment, we have an immediate availability of products, entertainment, food and information.

…

Notes 1 Harbison, F., quoted in Teheranian, M., Communications policy for national development, Routledge, London, 2016. 2 Schramm, W., Mass media and national development, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 1973. 3 The Total Audience Report: Q1 2016, Nielsen.com, available at: http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/reports/2016/the-total-audience-report-q1-2016.html 4 Johnson, C., The Information Diet: A Case for Conscious Consumption, O’Reilly Media, London, 2015. 5 Ibid., p. 31. 6 Ibid., p. 35. 7 Merrill, J., The Elite Press, Pitman, New York, 1968, p. 20. 8 Mitchell, A., Stocking, G. and Matsa, K., ‘Long-Form Reading Shows Signs of Life in Our Mobile News World’, Pew Research Center for Journalism & Media, 5 May 2016. 9 Shearer, E. and Gottfried, J., News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2017, Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project, 2018, available at: http://www.journalism.org/2017/09/07/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2017/ 10 Pariser, E., Beware online ‘filter bubbles’, Ted.com, 2018, available at: https://www.ted.com/talks/eli_pariser_beware_online_filter_bubbles 11 Vinderslev, A., BuzzFeed: The top 10 examples of BuzzFeed doing native advertising, Native Advertising Institute, 2018, assssssvailable at: https://nativeadvertisinginstitute.com/blog/10-examples-buzzfeed-native-advertising/ RESOURCES News organisations: ‘BBC World Hacks’ BRIGHT Magazine The Correspondent Delayed Gratification INKLINE Monocle News Deeply The Optimist Daily Positive News Solutions Journalism Network Sparknews ‘The Upside’ (by the Guardian) The Week ‘What’s Working’ (by the Huffington Post) YES!

…

Refuse to accept that there is only one way that the news should be; refuse to accept that negative news is the only narrative worth telling; refuse to accept that the news ‘is the way that it is’ and instead decide that it should be more balanced in its coverage. And then start making changes and choices that reflect this. There are six effective ways we can change our media diet in a way that will help us become more informed, engaged and empowered: 1. Become a conscious consumer 2. Read/watch good-quality journalism 3. Burst your filter bubble 4. Be prepared to pay for content 5. Read beyond the news 6. Read solutions-focused news 1. Become a conscious consumer The freedom of the press is sacrosanct in most modern-day democracies. This freedom provides an awfully long lead on what kind of product they are able to produce. They have almost free reign to exploit our appetite for sensationalised bad news.

The People's Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age

by

Astra Taylor

Published 4 Mar 2014

We are not purposefully retreating into our own distinct worlds, becoming more insular. Instead, invisible filter bubbles are imposed on us. Online, no action goes untracked. Our prior choices are compiled, feeding the ids of what we could call algorithmic superegos—systems that determine what we see and what we don’t, channeling us toward certain choices while cutting others off. And while they may make the Internet less overwhelming, these algorithms are not neutral. “The rush to build the filter bubble is absolutely driven by commercial interests,” Pariser warns. “It’s becoming clearer and clearer that if you want to have lots of people use your Web site, you need to provide them with personally relevant information, and if you want to make the most money on ads, you need to provide them with relevant ads.”41 Ironically, what distinguishes this process from what Nicholas Negroponte enthusiastically described as “the Daily me”—the ability of individuals to customize their media diets thanks to digital technology—is that the personalization trend is not driven by individual demand but by the pursuit of profit via targeted advertising.

…

In the popular imagination, either the Internet has freed us from the stifling grip of the old, top-down mass media model, transforming consumers into producers and putting citizens on par with the powerful, or we have stumbled into a new trap, a social media hall of mirrors made up of personalized feeds, “filter bubbles,” narcissistic chatter, and half-truths. Young people are invoked to lend credence to both views: in the first scenario, they are portrayed as empowered and agile media connoisseurs who, refusing to passively consume news products handed down from on high, insist on contributing to the conversation; in the second, they are portrayed as pliant and ill-informed, mistaking what happens to interest them for what is actually important.

…

New mechanisms have emerged that sift through the chaos of online content, shaping it into a targeted stream. As a consequence, our exposure to difference may actually decrease. Eli Pariser, the former executive director of MoveOn.org and founder of the viral content site Upworthy, calls this problem the “filter bubble,” a phenomenon that stems from the efforts of new-media companies to track the things we like and try to give us more of the same. These mechanisms are “prediction engines,” Pariser says, “constantly creating and refining a theory of who you are and what you’ll want next.”40 This kind of personalization is already part of our daily experience in innumerable ways.

The Smartphone Society

by

Nicole Aschoff

See, for example, Toplensky, “EU Fines Google €2.4bn over Abuse of Search Dominance”; Waters, Toplensky, and Ram, “Brussels’ €2.4bn Fine Could Lead to Damages Cases and Probes in Other Areas of Search;” Barker and Khan, “EU Fines Google Record €4.3bn over Android.” 45. For a good synopsis of Pariser’s ideas, see Beware Online Filter Bubbles, video of TED Talk, https://www.ted.com/talks/eli_pariser_beware_online_filter_bubbles?language=en; see also Pariser, The Filter Bubble. 46. Zuckerberg himself used to refer to Facebook as a “social utility,” but in recent years he has eschewed this terminology, possibly because the implications of Facebook’s being a utility are far afield from his vision for the company. 47.

…

When we pull out our phones to search for, say, the presidential election, we most likely get very different results from another person sitting next to us doing an identical search on their phone. The information we receive is tailored to us on the basis of our past searches, websites visited, our current location, what type of phone we’re using, and a host of other factors. As Pariser says, we each live in a “filter bubble”—our “own personal unique universe of information.” The idea of a standard Google in which everyone typing the same query gets the same search results simply no longer exists.45 Personalization is not limited to Google; Facebook, Yahoo, Twitter, even the websites of major newspapers are using personalization to increase user engagement.

…

He says, “Social media makes it easier for people to surround themselves (virtually) with the opinions of likeminded others and insulate themselves from competing views.” Likening social media to a disease vector, Sunstein surmises that it is “potentially dangerous for democracy and social peace.”56 In these days of filter bubbles and algorithmically generated search results it takes effort to seek out opposing political views. Our social media feeds largely show us political content that we already “like.” If we don’t hear other people’s perspective, can we agree on a collective political project? Others say much of the behavior associated with modern social movement organizing is not real politics.

Collaborative Society

by

Dariusz Jemielniak

and

Aleksandra Przegalinska

Published 18 Feb 2020

Thus, we show that collaboration is a default human orientation, further enabled and amplified by online platforms. In our ninth and final chapter, “Controversies and the Future of Collaborative Society,” we extrapolate from the current trends and observe that collaborative tendencies may not necessarily prevail. We discuss the negative effect of collaborative society’s advances, including filter bubbling and fake news. We remark on the dangers and potential of bots and other nonhuman actors that now enter the collaborative society, but we also discuss being open to their positive capabilities. Finally, we consider the possible impact of intermediating technologies on the future of collaboration. 2 Neither “Sharing” nor “Economy” Open collaboration, sharing economy, platform capitalism, and peer production all describe certain aspects of a revolutionary change resulting from sociotechnological advancement.

…

In fact, Donald Trump’s 2016 US election victory and the UK’s Brexit campaign success that same year are both partly attributable to an avalanche of fake news and skillful trolling. The general information overflow combined with the increase in fake news presence has increased the importance of our proficient use of search engines along with the ability to access the relevant filter bubbles and to prioritize alternate knowledge sources over traditional textbook knowledge.53 Since traditional information sources slowly lose trust while fake news propagation thrives, people succumb to new forms of tribalism: they trust the online communities that they know and to which they belong.

…

Even when opposing views appear side by side, people still select from content that upholds opinions they already agree with. The internal logic of social media platforms themselves reinforce their users’ “safe” choices by offering them a narrower spectrum of sources.5,6 In this way, online collaboration amplifies the echo chambers and further insulates the filter bubbles. For better or for worse, the process of discovery undergoes a transformation, from an individual to a social endeavor.7 We are not exactly clear yet how this rapidly advancing virtual layer will further translate into the real world. But there is one thing we are beginning to realize: the virtual/real public space, subjected to continuous transformation, may become more unstable, fragmented, and fragile, but it is also increasingly open for collaboration, particularly for motivated and consolidated online groups.

Internet for the People: The Fight for Our Digital Future

by

Ben Tarnoff

Published 13 Jun 2022

“Trading up the chain”: Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis, “Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online,” Data & Society Research Institute, May 15, 2017. 142, This messiness is manifest … Lack of evidence for “filter bubbles”: Peter M. Dahlgren, “A Critical Review of Filter Bubbles and a Comparison with Selective Exposure,” Nordicom Review 42, no. 1 (2021): 15–33; Axel Bruns, “Filter Bubble,” Internet Policy Review 8, no. 4 (2019). “Widespread heterogeneity …”: P. M. Krafft and Joan Donovan, “Disinformation by Design: The Use of Evidence Collages and Platform Filtering in a Media Manipulation Campaign,” Political Communication 37, no. 2 (2020): 195.

…

It is designed to elicit strong emotions like anger so that it can spread more easily. It spreads more easily because social media sites are optimized for user engagement—capturing more user attention means collecting more advertising dollars—and content that provokes and enrages naturally gets more engagement. Finally, algorithmically generated echo chambers—“filter bubbles”—create perfect vectors for such content. Insulated from the moderating influence of mainstream media, and from the dissenting views of other users, these bubbles become breeding grounds for extremism. There are elements of truth to this story. But it is mostly misleading. It makes a number of questionable assumptions, and rests on an oversimplified, mechanistic model of how software and psychology and politics interact.

…

The information that people encounter online matters, but its relationship with their beliefs is nonlinear: Dylann Roof did not became a neo-Nazi on the basis of a single Google search. Human beings are complicated and contradictory. So is the process whereby they acquire their ideological frames. This messiness is manifest in online spaces, contrary to the “filter bubbles” thesis—which, like the theory that polarization is produced by social media, has scant evidence to support it. People can and do find like-minded interlocutors on the internet, and the algorithms that underpin social media feeds and recommendation systems can contribute to these clusterings.

Don't Be Evil: How Big Tech Betrayed Its Founding Principles--And All of US

by

Rana Foroohar

Published 5 Nov 2019

In these and many other senses, the digital revolution is a miraculous and welcome development. But in order to ultimately reap the benefits of technology in a broad way, we need a level playing field, so that the next generation of innovators is allowed to thrive. We don’t yet live in that world. Big Tech has reshaped labor markets, exacerbated income inequality, and pushed us into filter bubbles in which we get only the information that confirms the opinions we already have. But it hasn’t provided solutions for these problems. Instead of enlightening us, it is narrowing our view; instead of bringing us together, it is tearing us apart. With each buzz and beep of our phones, each automatically downloaded video, each new contact popping up in our digital networks, we get just a glimmer of a vast new world that is, frankly, beyond most people’s understanding, a bizarre land of information and misinformation, of trends and tweets, and of high-speed surveillance technology that has become the new normal.

…

The Data-Industrial Complex A few years back, Guillaume Chaslot, a former engineer for YouTube who is now at the Center for Humane Technology, a group of Silicon Valley refugees who are working to create less harmful business models for Big Tech, was part of an internal project at YouTube, the content platform owned by Google,2 to develop algorithms that would increase the diversity and quality of content seen by users. It was an initiative that had begun in response to the “filter bubbles” that were proliferating online, in which people would end up watching the same mindless or even toxic content again and again, because algorithms that tracked them as they clicked on cat videos or white supremacist propaganda once would suggest the same type of content again and again, assuming (often correctly) that this was what would keep them coming back and watching more—thus allowing YouTube to make more money from the advertising sold against that content.

…

It was one of many, many letters that he and other senators have written in recent years, trying to get Big Tech to change its behavior. But simply making a few half-hearted efforts on the margins—adding a few human watchdogs here and there, or reiterating their supposed commitment to quality content over propaganda—is akin to trying to treat an aggressive cancer with a multivitamin. Why? Because these problems—filter bubbles, fake news, data breaches, and fraud—are all at the center of the most malignant—and profitable—business model in the world: that of data mining and hyper-targeted advertising.10 The Aura of Science The Cambridge Analytica scandal, whereby it was revealed that the Facebook platform had been exploited by foreign actors to influence the outcome of the 2016 presidential election—precipitated a huge rise in public awareness of how social media and its advertising-driven revenue model could pose a threat to liberal democracy.

The Internet Trap: How the Digital Economy Builds Monopolies and Undermines Democracy

by

Matthew Hindman

Published 24 Sep 2018

Facebook in particular has emphasized hyperpersonalization, with Facebook founder and ceo Mark Zuckerberg stating that “a squirrel dying in your front yard may be more relevant to your interests right now than people dying in Africa.”5 With the rise of the iPad and its imitators, Negroponte’s idea that all of this personalized content would be sent to a thin, lightweight, “magical” tablet device has been partially realized, too. Scholarship such as Siva Vaidhyanathan’s The Googlization of Everything and Joe Turow’s The Daily You has viewed the trend toward personalized content and ubiquitous filtering as a part of a worrying concentration of corporate power. Eli Pariser’s bestselling book The Filter Bubble voices similar worries. But for journalism and media scholarship as a whole, as Barbie Zelizer has noted, there has been surprisingly little work on recommender systems.6 To the extent that algorithmic news filtering has been discussed at all, it was long unhelpfully lumped with a grab bag of different site features under the heading of “interactivity.”7 Research by Neil Thurman and Steve Schifferes has provided a taxonomy of different forms of personalization and has chronicled their (mostly growing) deployment across different news sites.8 Even Thurman and Schifferes’s work, however, has said little about recommender systems because traditional news organizations lagged in deploying them.

…

After years of effort, the contest had ended in a photo finish. The Lessons of the Netflix Prize Why should those interested in online audiences or digital news care about the Netflix Prize? One answer is that these recommender systems now have enormous influence on democratic discourse. In his book The Filter Bubble progressive activist Eli Pariser reported that posts from conservative friends were systematically excluded from his Facebook feed. This sort of filtering heightens concerns about partisan echo chambers, and it might make it harder for citizens to seek out opposing views even if they are inclined to.

…

In one way, however, Netflix’s example calls into question claims that filtering technologies will end up promoting echo chambers and eliminating serendipitous exposure. Such worries have been a centerpiece of scholarship on personalized news over the past decade (see earlier discussion). One of Pariser’s key claims about what he terms the “filter bubble” is that it is ostensibly invisible to users.32 Netflix, however, tries hard to make users aware of its recommendation system: “We want members to be aware of how we are adapting to their tastes. This not only promotes trust in the system, but encourages members to give feedback that will result in better recommendations.”33 Netflix also attempts to explain (in an oversimplified way) why specific movies are recommended, typically highlighting its recommendations’ similarity to movies the user has already rated.

The Formula: How Algorithms Solve All Our Problems-And Create More

by

Luke Dormehl

Published 4 Nov 2014

“I’m interested in trying to subvert all of that; removing the clutter and noise to create a more efficient way to help users gain access to things.” The problem, of course, is that in order to save you time by removing the “clutter” of the online world, Nara’s algorithms must make constant decisions on behalf of the user about what it is that they should and should not see. This effect is often called the “filter bubble.” In his book of the same title, Eli Pariser notes how two different users searching for the same thing using Google will receive very different sets of results.36 A liberal who types “BP” into his browser might get information about the April 2010 oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, while a conservative typing the same two letters is more likely to receive investment information about the oil company.

…

Unlike the libertarian technologist’s pipe dream of a world that is free, flat and open to all voices, a key component of code and algorithmic culture is software’s task of sorting, classifying and creating hierarchies. Since so much of the revenue of companies like Google depends on the cognitive capital generated by users, this “software sorting” immediately does away with the idea that there is no such thing as a digital caste system. As with the “filter bubble,” it can be difficult to tell whether the endless distinctions made regarding geo-demographic profiles are helpful examples of mass customization or exclusionary examples of coded discrimination. Philosopher Félix Guattari imagined the city in which a person was free to leave their apartment, their street or their neighborhood thanks to an electronic security card that raised barriers at each intersection.

…

“[A] map was just a map, and you got the same one for New York City, whether you were searching for the Empire State Building or the coffee shop down the street. What if, instead, you had a map that’s unique to you, always adapting to the task you want to perform right this minute?” But while this might be helpful in some senses, its intrinsic “filter bubble” effect may also result in users experiencing less of the serendipitous discovery than they would by using a traditional map. Like the algorithmic matching of a dating site, only those people and places determined on your behalf as suitable or desirable will show up.33 As such, while applying The Formula to the field of cartography might be a logical step for Google, it is potentially troubling.

The End of Absence: Reclaiming What We've Lost in a World of Constant Connection

by

Michael Harris

Published 6 Aug 2014

There’s always going to be both comfort food and something surprising.” Roman’s insistence on tastemaking flies in the face of most content providers, who seek only to gratify the known desires of users. And it’s an impulse that could go a long way toward countering something that Internet activist Eli Pariser has coined “the filter bubble.” Here’s how a filter bubble works: Since 2009, Google has been anticipating the search results that you’d personally find most interesting and has been promoting those results each time you search, exposing you to a narrower and narrower vision of the universe. In 2013, Google announced that Google Maps would do the same, making it easier to find things Google thinks you’d like and harder to find things you haven’t encountered before.

…

A restaurateur in Ottawa’s famous ByWard Market: “Marisol Simoes Jailed: Co-owner of Kinki and Mambo in Ottawa Gets 90 Days for Defamation,” Huffington Post, accessed January 16, 2014, http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2012/11/16/marisol-simoes-jailed_n_2146205.html. “Today’s internet is killing our culture”: Andrew Keen, The Cult of the Amateur (New York: Doubleday/Currency, 2007). “the filter bubble”: Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think (New York: Penguin Press, 2011). Google announced that Google Maps: Evegny Morozov, “My Map or Yours?,” Slate, accessed September 4, 2013, http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2013/05/google_maps_personalization_will_hurt_public_space_and_engagement.html.

…

Eventually, the information you’re dealing with absolutely feels more personalized; it confirms your beliefs, your biases, your experiences. And it does this to the detriment of your personal evolution. Personalization—the glorification of your own taste, your own opinion—can be deadly to real learning. Only if sites like Songza continue to insist on “surprise” content will we escape the filter bubble. Praising and valuing those rare expert opinions may still be the best way to expose ourselves to the new, the adventurous, the truly revelatory. • • • • • Commensurate with the devaluing of expert opinion is the hypervaluing of amateur, public opinion—for its very amateurism. Often a comment field will be freckled with the acronym IMHO, which stands for the innocuous phrase “in my honest opinion” (or, alternatively, “in my humble opinion”).

Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now

by

Jaron Lanier

Published 28 May 2018

Armies of trolls and fake trolls would game the system and add enough cruel podcast snippets to the mix that your digest would become indigestible. Even the sweetest snippets would become mere garnishes on a cruel, paranoid, enraging, and crazy-making sonic soup. Or, maybe your aggregated podcast will be a filter bubble. It will include only voices you agree with—except they won’t really be voices, because the content will all be mushed together into a stream of fragments, a caricature of what listeners supposedly hold in common. You wouldn’t even live in the same universe as someone listening to a different aggregation.

…

I still believe that it’s possible for tech to serve the cause of empathy. If a better future society involves better tech at all, empathy will be involved. But BUMMER is precisely tuned to ruin the capacity for empathy. DIGITALLY IMPOSED SOCIAL NUMBNESS A common and correct criticism of BUMMER is that it creates “filter bubbles.”3 Your own views are soothingly reinforced, except when you are presented with the most irritating versions of opposing views, as calculated by algorithms. Soothe or savage: whatever best keeps your attention. You are drawn into a corral with other people who can be maximally engaged along with you as a group.

…

(But, to review, the term should be “manipulate,” not “engage,” since it’s done in the service of unknown third parties who pay BUMMER companies to change your behavior. Otherwise, what are they paying for? What else could Facebook say it’s being paid tens of billions of dollars to do?) On the face of it, filter bubbles are bad, because you see the world in tunnel vision. But are they really new? Surely there were damaging and annoying forms of exclusionary social communication that predate BUMMER, including the use of racist “dog whistles” in politics. For example, in the 1988 American presidential election, politicians famously used the story of a black man named Willie Horton who had committed crimes after a prison furlough in order to evoke latent racism in the electorate.

#Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media

by

Cass R. Sunstein

Published 7 Mar 2017

doid=2488388.2488435 (accessed August 23, 2016). In a similar vein, a 2015 paper takes initial steps toward visualizing filter bubbles in Google and Bing searches, finding that both search engines do create filter bubbles; the authors, however, note that it appears that filter bubbles may be stronger within certain topics (such as results of searches about jobs) than within others (such as results from searches about asthma). Tawanna R. Dillahunt, Christopher A. Brooks, and Samarth Gulati, “Detecting and Visualizing Filter Bubbles in Google and Bing,” Proceedings of the Thirty-Third Annual ACM Conference: Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 2015), 1851–56, http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?

…

(working paper, MIT Sloan School, Cambridge, MA, 1996), http://web.mit.edu/marshall/www/papers/CyberBalkans.pdf (accessed August 23, 2016). 2.In a provocative 2011 book, Eli Pariser popularized a theory of “filter bubbles” in which he posited that due to the effects of algorithmic filtering, Internet users are likely to be provided with information that conforms to their existing interests and, in effect, is isolated from differing viewpoints. We continue to obtain evidence on the phenomenon. Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think (New York: Penguin Press, 2011). A 2013 paper measures the effect of search personalization on Google, concluding that 11.7 percent of Google search results differed between users due to personalization—a finding that the authors describe as “significant personalization.”

…

Adamic, “Exposure to Ideologically Diverse News and Opinion on Facebook,” Science 348, no. 6239 (2015): 1130–32. 46.Ibid., 1132. 47.Eytan Bakshy, Solomon Messing, and Lada Adamic, “Exposure to Diverse Information on Facebook,” Research at Facebook, May 7, 2015, https://research.facebook.com/blog/exposure-to-diverse-information-on-facebook/ (accessed September 6, 2016). 48.See, for example, Chris Cillizza, “Why Facebook’s News Feed Changes Are Bad News for News, Washington Post, June 29, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/06/29/why-facebooks-news-feed-changes-are-bad-news/?tid=sm_tw_pp&wprss=rss_the-fix (accessed September 6, 2016). 49.Quoted in Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think (New York: Penguin Press, 2011), 1. 50.Moshe Blank and Jie Xu, “News Feed FYI: More Articles You Want to Spend Time Viewing,” Facebook Newsroom, April 21, 2016, http://newsroom.fb.com/news/2016/04/news-feed-fyi-more-articles-you-want-to-spend-time-viewing// (accessed September 6, 2016). 51.See, for example, Alessandro Bessi, Fabiana Zollo, Michela Del Vicario, Antonio Scala, Guido Caldarelli, and Walter Quattrociocchi, “Trend of Narratives in the Age of Misinformation,” PLOS ONE 10, no. 8 (2015): 1–16, http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/asset?

Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture

by

Kyle Chayka

Published 15 Jan 2024

In 2011, the writer and Internet activist Eli Pariser published his book The Filter Bubble, describing how algorithmic recommendations and other digital communication routes can silo Internet users into encountering only ideologies that match their own. The concept of filter bubbles has been debated over the decade since then, particularly in the context of political news media. Some evaluations, like Axel Bruns’s 2019 book Are Filter Bubbles Real?, have concluded that their effects are limited. Other scientific studies, like a 2016 investigation of filter bubbles in Public Opinion Quarterly, found that there is a degree of “ideological segregation,” particularly when it comes to opinion-driven content.

…

Other scientific studies, like a 2016 investigation of filter bubbles in Public Opinion Quarterly, found that there is a degree of “ideological segregation,” particularly when it comes to opinion-driven content. Yet culture and cultural taste have different dynamics than political content and ideological beliefs online; even though they travel through the same feeds, they are driven by different incentives. While political filter bubbles silo users into opposing factions by disagreement, cultural recommendations bring them together toward the goal of building larger and larger audiences for the lowest-common-denominator material. Algorithmic culture congregates in the center, because the decision to consume a piece of culture is rarely motivated by hate or conflict.

…

After the 2016 election of Donald Trump, the American public became slightly more aware of how we were being manipulated by algorithmic feeds. Democrats couldn’t understand how anyone had voted for Trump, given that their Facebook and Twitter feeds didn’t promote as many posts from the other side of the political spectrum, creating one of Eli Pariser’s filter bubbles, a digital echo chamber. Online, they lived in an illusion of total agreement that Trump was ridiculous. At the same time, his supporters were surrounded by content that reinforced their own views—another form of homogeneity. Recommender systems had sorted the audiences into two neat categories that didn’t need to overlap, whereas in a human-edited newspaper or television news program, some mutual exposure might have been more likely.

The Vanishing Neighbor: The Transformation of American Community

by

Marc J. Dunkelman

Published 3 Aug 2014

No longer do we have to trudge to the library and pull out a volume of the Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature to find an article detailing the electoral landscape in the panhandle of Michigan; with a few keystrokes from our living room couch we can call up every article ever written on the subject. The advent of social networking has only served to press the point further. As Eli Pariser recently argued in The Filter Bubble, without our even knowing it, many software companies have found ways to predict the information we want and provide it to the exclusion of everything else.5 As a further convenience (of sorts), the previous searches need not be related; it’s now possible, for example, to associate our political sensibilities with our taste in restaurants and alcohol.

…

Nevertheless, it seems less likely that networks of individuals ensconced in conversations on topics with which they agree will yield as many big breakthroughs. And that marks our central challenge. No one can claim credibly that Americans are intellectually isolated today, even if we are caught in what Eli Pariser once termed “filter bubbles.”36 What remains to be seen—and what ought to worry anyone looking at the future of economic growth—is whether the new arena for the Medici effect will, in the end, prove as effective as the old. The manner in which Americans organized themselves—what Tocqueville saw as such a crucial element of American exceptionalism—had an altogether underappreciated effect on the growth and dynamism of the American economy.

…

Mann and Norman J. Ornstein, It’s Even Worse Than It Looks: How the American Constitutional System Collided with the New Politics of Extremism (New York: Basic Books, 2012), 59. 4Bill Carter, “Prime-Time Ratings Bring Speculation of a Shift in Habits,” New York Times, April 23, 2012. 5Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You (New York: Penguin Press, 2011), 6–10. 6Cramer, Ruby. “2 Charts That Explain What Your Food Says About Your Politics,” Buzzfeed.com, October 31, 2012, http://www.buzzfeed.com/rubycramer/2-charts-that-explain-what-your-food-says-about-yo. 7Natasha Singer, “Your Online Attention, Bought in an Instant,” New York Times, November 17, 2012. 8Kenneth T.

What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of Computing

by

Ed Finn

Published 10 Mar 2017

Gillespie, “The Relevance of Algorithms”; Pariser, The Filter Bubble; Galloway, Protocol. 78. Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture, 17. 79. Galloway, Gaming, 76. 80. For more on this debate see Hayles, My Mother Was a Computer; Hansen, Bodies in Code, among many others. The topic is explored through a number of seminal cyberpunk novels, such as: Gibson, Neuromancer; Sterling, Schismatrix; and, of course, Stephenson, Snow Crash. 81. Bogost and Montfort, “Platform Studies.” 82. Kirschenbaum, Mechanisms, 10–11. 83. Ibid., 12–13. 84. Bogost, “The Cathedral of Computation.” 85. Pariser, The Filter Bubble. 86. Stephenson, Snow Crash, 434. 87.

…

Golumbia stands in here for a range of critics who argue that the de facto result of computational culture, at least if we do not intervene, is to reinforce state power. In later chapters we will examine more closely the “false personalization” that Tarleton Gillespie cautions against, extending Internet activist and author Eli Pariser’s argument in The Filter Bubble, as well as media theorist Alexander Galloway’s elegant framing of the political consequences of protocol.77 But Turner’s From Counterculture to Cyberculture offers a compelling view of how countercultural impulses were woven into the fabric of computational culture from the beginning. The figure of the hacker draws its lineage in part from the freewheeling discourse of the industrial research labs of the 1940s; the facilities that first created the opportunities for young people to not only work but play with computers.78 But, as Galloway has argued, the cybernetic paradigm has recast the playful magic of computation in a new light.

…

They reshape the spaces within which we see ourselves. Our literal and metaphorical footprints through real and virtual systems of information and exchange are used to shape the horizon ahead through tailored search results, recommendations, and other adaptive systems, or what Pariser calls the “filter bubble.”85 But when algorithms cross the threshold from prediction to determination, from modeling to building cultural structures, we find ourselves revising reality to accommodate their discrepancies. In any system dependent on abstraction there is a remainder, a set of discarded information—the différance, or the crucial distinction and deferral of meaning that goes on between the map and the territory.

Likewar: The Weaponization of Social Media

by

Peter Warren Singer

and

Emerson T. Brooking

Published 15 Mar 2018

So subtle was the code that governed user experience on these platforms, most people had no clue that the information they saw might differ drastically from what others were seeing. Online activist Eli Pariser described the effect, and its dangerous consequences, in his 2011 book, The Filter Bubble. “You’re the only person in your bubble,” he wrote. “In an age when shared information is the bedrock of shared experience, the filter bubble is the centrifugal force, pulling us apart.” Yet, even as social media users are torn from a shared reality into a reality-distorting bubble, they rarely want for company. With a few keystrokes, the internet can connect like-minded people over vast distances and even bridge language barriers.

…

16,000,” New York Times, June 25, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/26/technology/in-a-big-network-of-computers-evidence-of-machine-learning.html. 249 “We never told it”: Ibid. 250 where to put the traffic lights: Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, “The Business of Artificial Intelligence,” Harvard Business Review, July 2017, https://hbr.org/2017/07/the-business-of-artificial-intelligence. 250 more than a million: Joaquin Quiñonero Candela, “Building Scalable Systems to Understand Content,” Facebook Code, February 2, 2017, https://code.facebook.com/posts/1259786714075766/building-scalable-systems-to-understand-content/. 250 wearing a black shirt: Ibid. 250 80 percent: “An Update on Our Commitment to Fight Violent Extremist Content Online,” Official Blog, YouTube, October 17, 2017, https://youtube.googleblog.com/2017/10/an-update-on-our-commitment-to-fight.html. 250 “attack scale”: Andy Greenberg, “Inside Google’s Internet Justice League and Its AI-Powered War on Trolls,” Wired, September 19, 2016, https://www.wired.com/2016/09/inside-googles-internet-justice-league-ai-powered-war-trolls/. 251 about 90 percent: Ibid. 251 thoughts of suicide: Vanessa Callison-Burch, Jennifer Guadagno, and Antigone Davis, “Building a Safer Community with New Suicide Prevention Tools,” Facebook Newsroom, March 1, 2017, https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/03/building-a-safer-community-with-new-suicide-prevention-tools/%20https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2017/03/building-a-safer-community-with-new-suicide-prevention-tools/. 251 database of facts: Jonathan Stray, “The Age of the Cyborg,” Columbia Journalism Review, Fall/Winter 2016, https://www.cjr.org/analysis/cyborg_virtual_reality_reuters_tracer.php. 251 managing the “trade-offs”: Kurt Wagner, “Facebook’s AI Boss: Facebook Could Fix Its Filter Bubble If It Wanted To,” Recode, December 1, 2016, https://www.recode.net/2016/12/1/13800270/facebook-filter-bubble-fix-technology-yann-lecun. 251 Their more advanced version: For a good overview, see “Cleverbot Data for Machine Learning,” Existor, accessed March 20, 2018, https://www.existor.com/products/cleverbot-data-for-machine-learning/. 252 machine-driven communications tools: Matt Chessen, “Understanding the Psychology Behind Computational Propaganda,” in Can Public Diplomacy Survive the Internet?

…

Yet these 4 billion flesh-and-blood netizens have now been joined by a vast number of digital beings, designed to distort and amplify, to confuse and distract. The attention economy may have been built by humans, but it is now ruled by algorithms—some with agendas all their own. Today, the ideas that shape battles, votes, and even our views of reality itself are propelled to prominence by this whirring combination of filter bubbles and homophily—an endless tide of misinformation and mysterious designs of bots. To master this system, one must understand how it works. But one must also understand why certain ideas take hold. The ensuing answers to these questions reveal the foundations of what may seem to be a bizarre new online world, but is actually an inescapable kind of war. 6 Win the Net, Win the Day The New Wars for Attention . . . and Power Media weapons [can] actually be more potent than atomic bombs.

How to Do Nothing

by

Jenny Odell

Published 8 Apr 2019

This chapter is also based on my personal experience learning about my bioregion for the first time, a new pattern of attention applied to the place I’ve lived in my entire life. If we can use attention to inhabit a new plane of reality, it follows that we might meet each other there by paying attention to the same things and to each other. In Chapter 5, I examine and try to dissolve the limits that the “filter bubble” has placed on how we view the people around us. Then I’ll ask you to stretch it even further, extending the same attention to the more-than-human world. Ultimately, I argue for a view of the self and of identity that is the opposite of the personal brand: an unstable, shapeshifting thing determined by interactions with others and with different kinds of places.

…

As Gordon Hempton, an acoustic ecologist who records natural soundscapes, put it: “Silence is not the absence of something but the presence of everything.”23 Unfortunately, our constant engagement with the attention economy means that this is something many of us (myself included) may have to relearn. Even with the problem of the filter bubble aside, the platforms that we use to communicate with each other do not encourage listening. Instead they reward shouting and oversimple reaction: of having a “take” after having read a single headline. I alluded earlier to the problem of speed, but this is also a problem both of listening and of bodies.

…

Compared to the algorithms that recommend friends to us based on instrumental qualities—things we like, things we’ve bought, friends in common—geographical proximity is different, placing us near people we have no “obvious” instrumental reason to care about, who are neither family nor friends (nor, sometimes, even potential friends). I want to propose several reasons we should not only register, but care about and co-inhabit a reality with, the people who live around us being left out of our filter bubbles. And of course, I mean not only social media bubbles, but the filters we create with our own perception and non-perception, involving the kind of attention (or lack thereof) that I’ve described so far. * * * — THE MOST OBVIOUS answer is that we should care about those around us because we are beholden to each other in a practical sense.

Messing With the Enemy: Surviving in a Social Media World of Hackers, Terrorists, Russians, and Fake News

by

Clint Watts

Published 28 May 2018

My experiences with the crowd—watching the mobs that toppled dictators during the Arab Spring, the hordes that joined ISIS, the counterterrorism punditry that missed the rise of ISIS, and the political swarms duped by Russia in the 2016 presidential election—lead me to believe that crowds are increasingly dumb, driven by ideology, desire, ambition, fear, and hatred, or what might collectively be referred to as “preferences.” Eli Pariser, the head of the viral content website Upworthy, noted in his book The Filter Bubble the emergence and danger of social media and internet search engine algorithms selectively feeding users information designed to suit their preferences. Over time, these “filter bubbles” create echo chambers, blocking out alternative viewpoints and facts that don’t conform to the cultural and ideological preferences of users. Pariser recognized that filter bubbles would create “the impression that our narrow self-interest is all that exists.”1 The internet brought people together, but social media preferences have now driven people apart through the creation of preference bubbles—the next extension of Pariser’s filter bubbles.

…

Counter-Efforts Must Advance, Lumpkin Says”, interview by Renee Montagne, Morning Edition, NPR, https://www.npr.org/2016/02/01/465106713/as-isis-evolves-u-s-counter-efforts-must-advance-lumpkin-says. CHAPTER 9: FROM PREFERENCE BUBBLES TO SOCIAL INCEPTION 1. Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think, Penguin Books (April 24, 2012). https://www.amazon.com/Filter-Bubble-Personalized-Changing-Think/dp/0143121235. 2. Tom Nichols, “The Death Of Expertise,” The Federalist (January 17, 2014) http://thefederalist.com/2014/01/17/the-death-of-expertise. 3. Thomas Jocelyn, “Abu Qatada Provides Jihadists with Ideological Guidance from a Jordanian Prison,” The Long War Journal (April 30, 2014). https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2014/04/jihadist_ideologue_p.php; and Spencer Ackerman, Shiv Malik, Ali Younes, and Mustafa Khalili, “Al-Qa’ida ‘Cut Off and Ripped Apart by Isis,’” The Guardian (June 15, 2015). https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jun/10/isis-onslaught-has-broken-al-qaida-its-spiritual-leaders-admit. 4.

…

Pariser recognized that filter bubbles would create “the impression that our narrow self-interest is all that exists.”1 The internet brought people together, but social media preferences have now driven people apart through the creation of preference bubbles—the next extension of Pariser’s filter bubbles. Preference bubbles result not only from social media algorithms feeding people more of what they want, but also people choosing more of what they like in the virtual world, leading to physical changes in the real world. In sum, our social media tails in the virtual world wag our dog in the real world. Preference bubbles arise subtly from three converging biases that collectively and powerfully herd like-minded people and harden their views as hundreds and thousands of retweets, likes, and clicks aggregate an audience’s preferences.

The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure

by

Greg Lukianoff

and

Jonathan Haidt

Published 14 Jun 2018

Retrieved from http://genforwardsurvey.com/assets/uploads/2017/09/NBC-GenForward-Toplines-September-2017-Final.pdf 11. Iyengar & Krupenkin (2018). 12. Pariser (2011). A “filter bubble” is what happens when the algorithms that websites use to predict your interests based on your reading/viewing habits work to avoid showing you alternative viewpoints. See: El-Bermawy, M. (2016, November 18). Your filter bubble is destroying democracy. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/2016/11/filter-bubble-destroying-democracy 13. Mann & Ornstein (2012). 14. Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2018, January 27). How wobbly is our democracy?

…

By the 1990s, there was a cable news channel for most points on the political spectrum, and by the early 2000s there was a website or discussion group for every conceivable interest group and grievance. By the 2010s, most Americans were using social media sites like Facebook and Twitter, which make it easy to encase oneself within an echo chamber. And then there’s the “filter bubble,” in which search engines and YouTube algorithms are designed to give you more of what you seem to be interested in, leading conservatives and progressives into disconnected moral matrices backed up by mutually contradictory informational worlds.12 Both the physical and the electronic isolation from people we disagree with allow the forces of confirmation bias, groupthink, and tribalism to push us still further apart.

…

Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 160, 1–9. Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Ostrom, V. (1997). The meaning of democracy and the vulnerability of democracies. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: How the new personalized web is changing what we read and how we think. New York, NY: Penguin Press. Pavlac, B. A. (2009). Witch hunts in the Western world: Persecution and punishment from the Inquisition through the Salem trials. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. Peterson, C., Maier, S.

These Strange New Minds: How AI Learned to Talk and What It Means

by

Christopher Summerfield

Published 11 Mar 2025

People have always populated their social networks with like-minded souls, from the local pub to the royal court, and the online world is no exception. We cleanse our feed of unpalatable ideas at the click of a button, or invent terms (like ‘safe space’) that justify avoiding our political opponents. But our tendency to inhabit filter bubbles is amplified by powerful forces beyond our control. On the internet, rather than being duped by a fake film set, we are trapped in filter bubbles that are created by algorithms embedded in the sites we visit. Each webpage you visit saves cookies on your browser, packets of data that store details of the articles you have read, or the items you have browsed. Cookies can be read by algorithms, to ensure that future searches will elicit products or news that you are more likely to consume.

…

The Truman Show was released in the late 1990s, just as reality TV was first starting to invade our screens. But the film was prescient in another important way. It heralded the arrival of a personalized online world, in which the content we consume exclusively reflects beliefs and desires that we already hold. In a seminal book from 2011, the activist Eli Pariser coined the term ‘filter bubble’ to describe how internet users are trapped (like Truman Burbank) in a personalized world, in which what we see and hear is carefully chosen to pacify us. Commercial advertising, search engines, and social media newsfeeds present us all with bespoke slices of reality, insulating us from the challenge or discomfort of hearing others’ views.

…

Personalization will no doubt make LLMs more engaging for the user, but also invites the risk that we are even more insulated from ideas or perspectives that differ from those we already hold. Current LLMs do already have a tendency to act in a somewhat personalized way, creating a mild form of filter bubble for the user. Recent papers by the AI research company Anthropic have studied the tendency for LLMs fine-tuned with RLHF (reinforcement learning from human feedback) to be sycophantic. The researchers co-opted the term ‘sycophancy’ to describe the model’s propensity to bend its speech to suit the supposed preferences of the user.

Super Thinking: The Big Book of Mental Models

by

Gabriel Weinberg

and

Lauren McCann

Published 17 Jun 2019

Many people don’t realize that they are getting tailored results based on what a mathematical algorithm thinks would increase their clicks, as opposed to a more objective set of ranked results. The Filter Bubble When you put many similar filter bubbles together, you get echo chambers, where the same ideas seem to bounce around the same groups of people, echoing around the collective chambers of these connected filter bubbles. Echo chambers result in increased partisanship, as people have less and less exposure to alternative viewpoints. And because of availability bias, they consistently overestimate the percentage of people who hold the same opinions.

…

Or you might just consider the interactions you have had with her personally, as opposed to getting a more holistic view based on interactions with other colleagues with different frames of reference. With the rise of personalized recommendations and news feeds on the internet, availability bias has become a more and more pernicious problem. Online this model is called the filter bubble, a term coined by author Eli Pariser, who wrote a book on it with the same name. Because of availability bias, you’re likely to click on things you’re already familiar with, and so Google, Facebook, and many other companies tend to show you more of what they think you already know and like.

…