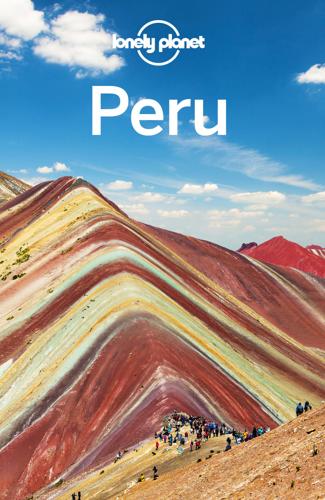

Lonely Planet Peru

by

Lonely Planet

History As ancient as it is new, Lima has survived apocalyptic earthquakes, warfare and the rise and fall of civilizations. This resilient city has welcomed a rebirth after each destruction. In pre-Hispanic times, the area served as an urban center for the Lima, Wari, Ichsma and the Inca cultures in different periods. When Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro sketched out the boundaries of his ‘City of Kings’ in 1535, there were roughly 200,000 indigenous people living in the area. By the 18th century, the Spaniards’ tumbledown village of adobe and wood had given way to a viceregal capital, where fleets of ships arrived to transport the golden spoils of conquest back to Europe.

…

Lima District & La Victoria 1Top Sights 1El Circuito Mágico del AguaC3 2Museo de Arte de LimaB1 1Sights 3Museo de Arte ItalianoB1 4Museo de Historia NaturalB4 5Parque de la CulturaB2 4Sleeping 61900 BackpackersB1 7Lima SheratonB1 5Eating 8AgallasD3 9Cevichería la Choza NauticaA1 10RovegnoB3 3Entertainment 11Brisas del Titicaca Asociacion CulturalB2 12Centro Cultural de EspañaB3 13Estadio NacionalC3 7Shopping 14Polvos AzulesC1 8Information 15Centro de La Mujer Peruana Flora TristánC2 16Clínica InternacionalB1 17ConadisC3 18Instituto Nacional de Salud del NiñoA2 19Oficina de MigraciónesA1 8Transport 20CivaC2 21Móvil ToursC2 22SoyuzD4 1Lima Centro The city’s historic heart, Lima Centro (Central Lima) is a grid of crowded streets laid out in the 16th-century days of Francisco Pizarro, and home to most of the city’s surviving colonial architecture. Bustling narrow streets are lined with ornate baroque churches in Lima’s historic and commercial center, located on the south bank of the Río Rímac. Few colonial mansions remain, as many have been lost to expansion, earthquakes and the perennially moist weather.

…

Few colonial mansions remain, as many have been lost to expansion, earthquakes and the perennially moist weather. The best access to the Plaza de Armas is the pedestrian-only street Jirón de la Unión. Plaza de ArmasPLAZA (map Google map) Lima’s 140-sq-meter Plaza de Armas, also called the Plaza Mayor, was not only the heart of the 16th-century settlement established by Francisco Pizarro, it was a center of the Spaniards’ continent-wide empire. Though not one original building remains, at the center of the plaza is an impressive bronze fountain erected in 1650. Surrounding the plaza are a number of significant public buildings: to the east is the Palacio Arzobispal (Archbishop’s Palace; map Google map), built in 1924 in a colonial style and boasting some of the most exquisite Moorish-style balconies in the city.

The Rough Guide to Peru

by

Rough Guides

Published 27 Apr 2024

This was the decisive victory for Atahualpa, and with his army he retired to relax at the hot baths near Cajamarca. Here, informed of a strange-looking, alien band of men, successors to the bearded adventurers whose presence had been noted during the reign of Huayna Capac, he waited with his followers. Francisco Pizarro arrives Francisco Pizarro, along with two dozen soldiers, was accompanying explorer Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, when he stumbled upon and named the Pacific Ocean in 1513 while on an exploratory expedition in modern Panama. From that moment his determination, fired by local tales of a fabulously rich land to the south, was set.

…

Brief history When the Spanish first arrived here in 1533, the valley was dominated by three important Inca-controlled urban complexes: Carabayllo, to the north near Chillón; Maranga, now partly destroyed, by the Avenida La Marina, between the modern city and the Port of Callao; and Surco, now a suburb within the confines of greater Lima but where, until the mid-seventeenth century, the colourfully painted adobe houses of ancient chiefs lay empty. Now these structures have faded back into the sandy desert terrain, and only the larger pyramids remain. The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries Francisco Pizarro founded Spanish Lima, nicknamed the “City of the Kings”, in 1535. The name is thought to derive from a mispronunciation of Río Rimac, while others suggest that “Lima” is an ancient word that described the lands of Taulichusco, the chief who ruled this area when the Spanish arrived. Evidently recommended by communities in the mountains as a site for a potential capital, it proved a good choice – apart perhaps from the winter coastal fog – offering a natural harbour nearby, a large well-watered river valley and relatively easy access to the Andes.

…

Palacio de Gobierno Plaza Mayor • Changing of the guard Mon–Sat warm-up at 11.45am, start at noon • Tours Sat & Sun; pre-register at scuadros@presidencia.gob.pe or call 01 630 5600 (Mon–Fri 9am–6pm) • Free • presidencia.gob.pe The Palacio de Gobierno – also known as the Presidential Palace – was the site of the house of Francisco Pizarro long before the present building was conceived. It was here that he spent the last few years of his life, until his assassination in 1541. As he died, his jugular severed by the assassin’s rapier, Pizarro fell to the floor, drew a cross, then kissed it; even today some believe this ground to be sacred.

Ambition, a History

by

William Casey King

Published 14 Sep 2013

But they have largely ignored the influence of Spanish colonization that preceded and informed the English expectations reflected in this play.14 While More may have imagined golden chamber pots in 1516, the English well knew that the Spanish had subsequently discovered some approximation of what More intended as hyperbole. And there was no telling what more remained. For any satire to be effective, there must be a grain of truth. For the English, the Spanish experience, the incredible discoveries of Columbus, Hernán Cortés, and Francisco Pizarro, among others, were truth enough. The other truth was the moral of this parable—that all the hopes invested in America, satirized in Eastward Hoe, included the impossible and inevitable expectation that in Virginia any man might be a Pizarro or Cortés. It is perhaps not surprising that few scholars look to Spain as a source for the English dramatic imagining of Virginia in 1605.

…

Birth and blood, like the “sun, moon, and stars, and earth and sea,” dictate a place in the world. The early modern graffiti artist mocked the vanity of Cortés’s ambition. Thomas Nicholas, however, celebrated it for an English audience eager for more. After the popularity of his translation of Cortes’s conquest, Nicholas turned to Francisco Pizarro and Peru. In his translation of Agustín de Zárate’s history of the conquest of Peru, England learned of another stunning example of the transformative possibilities of America.57 But Pizarro’s story and his spectacular rise were informed as much by written histories as by popular myth drawn from a propaganda campaign to disparage him.

…

Gómara glorified the actions of his patron, Hernán Cortés, and often disparaged the actions of Cortés’s rivals, one of whom was the rival conqueror Pizarro. Gómara even maligned Pizarro’s family and origins, starting the “porcine legend,” the myth through which most early modern English readers, like John Smith, encountered Pizarro.58 Gómara claimed that Francisco Pizarro was abandoned at the door of a church, survived by nursing on a pig, and only later, and with great reluctance, was reclaimed by his father, who then put him to work as a swineherd.59 James Lockhart, in his study of Pizarro, states unequivocally, “There is not the slightest reason to believe any part of Gómara’s story.”60 Lockhart interrogates this myth and illustrates that it is at odds with the historical record, inspired by a vindictive competition for fame between the conqueror of Mexico and the conqueror of Peru.

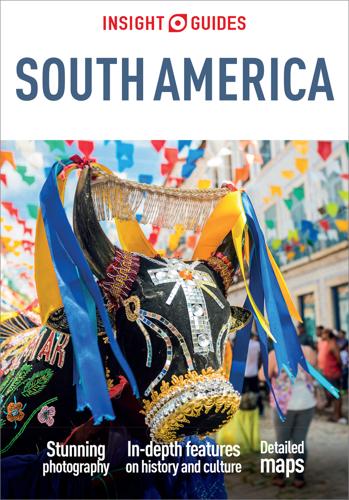

Insight Guides South America (Travel Guide eBook)

by

Insight Guides

Published 15 Dec 2022

First peoples Estimates as to how many people lived in South America before the Europeans arrived vary from 5 to 50 million; discoveries in the Amazon region have led archeologists to think there may have been several million inhabitants there. Over the centuries these peoples have been absorbed into the dominant system, or persecuted and their way of life destroyed. This process began in the 1530s, when the Inca empire was conquered by Francisco Pizarro. Lacking resistance to European diseases, millions were wiped out, and the survivors pushed to the bottom rung of society. Artifact from the Gold Museum, Bogotá. revolucian/Shutterstock The Mapuche people of Chile and Argentina resisted the longest, living independently until the end of the 19th century.

…

From their bases on the islands of Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, they started to explore Central America and the South American mainland. Gold was the lure that enticed most of them into the unknown territories. El Dorado was the legendary paradise where everything was made of gold. In 1532 Francisco Pizarro set out to find these fabled riches in the Inca Empire, which then stretched from north of Quito (in present-day Ecuador) south through the areas now known as Peru, Bolivia, and northern Chile and Argentina. With only 150 followers, Pizarro took control of the entire Inca Empire in just two years.

…

Presidents have been jailed under corruption allegations; in 2019, ahead of arrest for bribery allegations, García killed himself. The latest president, hard-left schoolteacher Pedro Castillo from Cajamarca, has had a tumultuous time in office, and an early resignation would be unsurprising. Lima: capital of the New World Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro considered the site where he founded Lima 1 [map] on January 18, 1535, inhospitable: rain seldom fell, earthquakes were common, and winter was a time of gray skies and dreary fog. But his soldiers saw it as the best place for a quick sea escape in the event of a Native uprising. Little did they suspect this open plain would become the political and military capital of the New World, seeing the reign of 40 viceroys before the “City of Kings” was declared capital of an independent Peru in 1821.

Civilization: The West and the Rest

by

Niall Ferguson

Published 28 Feb 2011

While Englishmen still hankered after conquering Calais, mighty native American empires were being subjugated by Spanish adventurers. In Mexico the bloodthirsty Aztecs were laid low by Hernán Cortés between 1519 and 1521. And in Peru, just over a decade later, the lofty Andean empire of the Incas was laid low by Francisco Pizarro. Pizarro had no illusions about the relationship between the risks and rewards of conquest. It took two expeditions in 1524 and 1526 even to locate the Inca Empire. In the course of the second, when some of his less tenacious brethren were faltering, Pizarro spelt out that relationship by drawing a line in the sand: Comrades and friends, there lies the part that represents death, hardship, hunger, nakedness, rains and abandonment; this side represents comfort.

…

In seven out of thirteen future American states on the eve of the American Revolution, the right to vote was a function of landownership or the payment of a property tax – rules that remained in force in some cases well into the 1850s. In the Spanish colonies to the south, land had been allocated in a diametrically different way. In a cedula (decree) dated 11 August 1534, Francisco Pizarro granted Jerónimo de Aliaga and another conquistador named Sebastián de Torres a vast domain – an encomienda – called Ruringuaylas, in the beautiful valley of Callejón de Huaylas in the Peruvian Andes. The valley was fertile, the mountains full of precious ore. The question facing de Aliaga was how to exploit these resources.

…

D., ‘Slavery and the Slave Trade in the Context of West African History’, Journal of African History, 10, 3 (1969), 393–404 Ferguson, Niall, The War of the World: History’s Age of Hatred (London, 2006) Fernández-Armesto, Felipe, The Americas: A History of Two Continents (London, 2003) Findlay, Ronald and Kevin H. O’Rourke, Power and Plenty: Trade, War, and the World Economy in the Second Millennium (Princeton, 2007) Gabai, Rafael Varón, Francisco Pizarro and his Brothers: The Illusion of Power in Sixteenth-Century Peru (Norman, 1997) Graham, R., Patronage and Politics in Nineteenth-Century Brazil (Stanford, 1990) Haber, Stephen, ‘Development Strategy or Endogenous Process? The Industrialization of Latin America’, Stanford University working paper (2005) Hamnett, Brian R., ‘The Counter Revolution of Morillo and the Insurgent Clerics of New Granada, 1815–1820’, Americas, 32, 4 (April 1976), 597–617 Hemming, J., The Conquest of the Incas (London, 1993) Hobbes, Thomas, Leviathan or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Common Wealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil (London, 1651) Jasanoff, Maya, Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World (forthcoming) King, James F., ‘A Royalist View of Colored Castes in the Venezuelan War of Independence’, Hispanic American Historical Review, 33, 4 (1953), 526–37 Klein, Herbert F. and Francisco Vidal Luna, Slavery in Brazil (Cambridge, 2010) Langley, Lester D., The Americas in the Age of Revolution, 1750–1850 (New Haven/London, 1998) Lanning, John Tate, Academic Culture in the Spanish Colonies (Port Washington, NY/London, 1969) Locke, John, Two Treatises of Government: In the former, The false Principles and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, And his Followers, are Detected and Overthrown.

War and Gold: A Five-Hundred-Year History of Empires, Adventures, and Debt

by

Kwasi Kwarteng

Published 12 May 2014

But, regardless of the relative merits of the military campaigns in Peru and Mexico, the result was a considerable flow of gold and particularly of silver into Spain which, over the coming decades, would transform the economy of Western Europe. Francisco Pizarro had been born in Trujillo, a town in Extremadura in Castile, in the late 1470s. He was in fact a distant cousin of Hernan Cortés, whose grandmother, Leonor, had been a Pizarro. As he was the illegitimate son of a soldier, Francisco Pizarro’s prospects were unfavourable, and reports that he had been a swineherd in his youth are plausible, since pigs were important in the local economy.13 Despite being illiterate and poor, he was bold and determined.

…

A handful of Spanish adventurers, in the first decades after the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus in 1492, had conquered and practically enslaved an entire continent, unknown to Europeans in previous centuries. The Spanish discovery of the New World has been called the ‘greatest event in history’.7 Its protagonists, men such as Hernando Cortés and Francisco Pizarro, became celebrated in their own lifetimes. Among the native populations, the Spanish were regarded as supermen, endowed with magical powers and equally superhuman greed. ‘Even if the snows of the Andes turned to gold still they would not be satisfied,’ observed Manco, the Inca noble who encountered Pizarro in the 1530s.

…

Despite the ambivalences of his nature, no one has disputed the scale, even if accomplished at a high price in human lives, of what was achieved in the conquest of Mexico. Cortés always showed himself to be an excellent commander, with an outstandingly even temperament, who could always improvise creatively in adversity. He spoke to his men in a steady, unruffled tone which often proved inspirational.11 Cortés’s exploits in Mexico were rivalled by those of Francisco Pizarro in Peru. Both men, like the other conquistadors, endured uncommon hardships in the pursuit of their calling, but they were often cruel. The ‘physical toughness’ and ‘sheer determination’ of the conquistadors have ‘certainly never been surpassed . . . Nor can we readily call to mind their equals in duplicity, greed, and utterly callous and unbridled cruelty.’12 The success Pizarro enjoyed in Peru was even more spectacular than Cortés’s triumphs in Mexico, though Pizarro had far fewer soldiers.

The Power of Gold: The History of an Obsession

by

Peter L. Bernstein

Published 1 Jan 2000

There was gold in central Hispaniola, where the Spaniards worked both the mines and the Indians so hard that by 1519 only two thousand of an original population of more than one hundred thousand remained and slaves were already being imported from Africa to do the nuning.15 Nevertheless, rumors were rife in Darien about vast supplies of gold somewhere to the south, perhaps near a sea whose uncertain existence might lead to the gold. When Balboa arrived in Darien, he became close friends with an illiterate swordsman, also from Estramadura, whose name was Francisco Pizarro. Pizarro, like Balboa, was a man who did not flinch at danger if a venture promised a commensurate reward. The move to Darien did nothing to solve Balboa's financial problems. One day in September 1513, still frustrated and in trouble with the law, Balboa was weighing some gold when a barbarian chieftain came up, scattered the glittering metal around the room, and cried, "I can tell you of a land where they eat and drink out of golden vessels, and gold is as cheap as iron is with you."16 This was all Balboa needed to prompt him to lead a great enterprise he expected would bring him to King Ferdinand's attention.

…

Some time after the discovery of the Pacific, at a moment when Balboa was making plans to sail southward on his newly discovered sea toward Peru in search of more gold, the governor of Darien accused him of treason and ordered him to be beheaded. The governor, who had been sent out with fifteen hundred men by the king of Spain after receiving the electrifying news of Balboa's discoveries, happened to be Balboa's father-in-law; the executioner assigned by the governor to this task was none other than Francisco Pizarro. Pizarro was an illegitimate child, abandoned by his mother on the church steps of the town where he was born. He grew up tough, a man of great endurance and strong leadership skills. At a time when most men rationalized their mistreatment of the Indians as motivated in some way to improve their lot and bring them the blessings of Christianity, Pizarro refused to mask his goals.

…

The chaplain announced that he had come to set forth to the Inca the articles of true faith, which he proceeded to do at great length. He finished by explaining the role of the pope, who had commissioned the Spanish emperor, "the most mighty monarch in the world, to conquer and convert the natives in this western hemisphere.... [His] general, Francisco Pizarro, had now come to execute this important mission."24 Atahualpa exploded. "I will be no man's tributary," he announced. "I am greater than any prince on earth.... For my faith, I will not change it. Your God, as you say, was put to death by the very men whom he created." He halted to point to the sun, then just beginning to set behind the mountains, and added, "But my God still lives in the heavens and looks down on his children."

1491

by

Charles C. Mann

Published 8 Aug 2005

Dobyns, a young anthropologist working on a rural-aid project in Peru, dispatched assistants to storehouses of old records throughout the country. Dobyns himself traveled to the central cathedral in Lima. Entering the nave, visitors passed by a chapel on the right-hand side that contained the mummified body of Francisco Pizarro, the romantic, thuggish Spaniard who conquered Peru in the sixteenth century. Or, rather, they passed by a chapel that was thought to contain the conqueror’s mummified body; the actual remains turned up years later, stashed inside two metal boxes beneath the main altar. Dobyns was not visiting the cathedral as a sightseer.

…

Llamas prefer the coolness of high altitudes and, unlike horses, readily go up and down steps. As a result, Inka roads eschewed valley bottoms and used long stone stairways to climb up steep hills directly—brutal on horses’ hooves, as the conquistadors often complained. Traversing the foothills to Cajamarca, Francisco Pizarro’s younger brother Hernando lamented that the route, a perfectly good Inka highway, was “so bad” that the Spanish “could not use horses on the roads, not even with skill.” Instead the conquistadors had to dismount and lead their reluctant animals through the steps. At that point they were vulnerable.

…

Consider Gaspar de Carvajal, author of the first written description of the Amazon, an account reviled for its inaccuracies and self-serving descriptions almost since the day it was released. Born in about 1500 in the Spanish town of Extremadura, Carvajal joined the Dominican order and went to South America to convert the Inka. He arrived in 1536, four years after Atawallpa’s fall. Francisco Pizarro, now governor of Peru, was learning that to avoid outbreaks of feckless violence he needed to keep his men occupied at all times. One of the worst troublemakers was his own half brother, Gonzalo Pizarro. At the time, conquistador society was abuzz with stories of El Dorado, a native king said to possess so much gold that in an annual ritual he painted his body with gold dust and then rinsed off the brilliant coating in a special lake.

Guns, germs, and steel: the fates of human societies

by

Jared M. Diamond

Published 15 Jul 2005

The third chapter introduces us to collisions between peoples from dif- ferent continents, by retelling through contemporary eyewitness accounts the most dramatic such encounter in history: the capture of the last inde- pendent Inca emperor, Atahuallpa, in the presence of his whole army, by Francisco Pizarro and his tiny band of conquistadores, at the Peruvian city of Cajamarca. We can identify the chain of proximate factors that enabled Pizarro to capture Atahuallpa, and that operated in European conquests of other Native American societies as well. Those factors included Spanish germs, horses, literacy, political organization, and technology (especially ships and weapons).

…

Instead, for practical purposes the collision of advanced Old World and New World societies began abruptly in A.D. 1492, with Christopher Columbus's “discovery” of Carib- bean islands densely populated by Native Americans. The most dramatic moment in subsequent European-Native American relations was the first encounter between the Inca emperor Atahuallpa and the Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro at the Peruvian highland town of Cajamarca on November 16, 1532. Atahuallpa was absolute monarch of the largest and most advanced state in the New World, while Pizarro represented the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (also known as King Charles I of Spain), monarch of the most powerful state in Europe.

…

He offered his famous ransom in the naive belief that, once paid off, the Spaniards would release him and depart. He had no way of understanding that Pizarro's men formed the spearhead of a force bent on permanent conquest, rather than an isolated raid. Atahuallpa was not alone in these fatal miscalculations. Even after Ata- huallpa had been captured, Francisco Pizarro's brother Hernando Pizarro deceived Atahuallpa's leading general, Chalcuchima, commanding a large army, into delivering himself to the Spaniards. Chalcuchima's miscalcula- tion marked a turning point in the collapse of Inca resistance, a moment almost as significant as the capture of Atahuallpa himself.

1494: How a Family Feud in Medieval Spain Divided the World in Half

by

Stephen R. Bown

Published 15 Feb 2011

The floodgates to the wealth of the Americas were now flung wide open. Roving bands of privately funded adventurers scoured the Americas from Florida to Peru, searching for another source of easy treasure. The Mayan city-states in the Yucatán Peninsula and Guatemala were subjugated by Pedro de Alvarado in 1523, and Francisco Pizarro led his band of privateers south to Peru in 1531. By 1533, Pizarro had defeated the Inca Empire and conquered the city of Cuzco by treacherously capturing Emperor Atahualpa. In Florida, Hernando de Soto led an expedition in search of the Fountain of Youth and the Seven Cities of Cibola in 1539.

…

{ timeline } 1418—1420 Portuguese mariners discover and settle the Madeira Islands in the Atlantic Ocean 1425 Enrique of Castile born 1434 Gil Eannes sails south along the African coast past Cape Bojador, beginning the Portuguese naval exploration of Africa and the slave trade under Henry the Navigator 1439 Portuguese mariners discover and settle the Azores 1440 Probable date for Gutenberg's first printing press 1451 Isabella of Castile born; Christopher Columbus born 1452 Pope Nicholas V issues the bull Dum Diversas, which provides the moral authority for the slave trade 1453 Constantinople falls to the invading armies of Mehmet the Conqueror 1454 Enrique becomes king of Castile 1455 Pope Nicholas v issues the bull Romanus Pontifex, establishing Portuguese monopoly along the African coast — King Enrique marries Juana of Portugal 1462 Juana la Beltraneja born 1464—1468 War for the Castilian succession 1469 Isabella and Ferdinand secretly wed in Toledo 1474 King Enrique IV dies in Madrid, Isabella proclaimed queen of Castile; war with Portugal 1476 Battle of Toro — Christopher Columbus washed ashore in Portugal after shipwreck 1477 A new translation of Ptolemy's Geography published in Bologna 1478 Papal bull of Sixtus IV establishes the Inquisition in Castile 1479 Treaty of Alcáçovas ends war between Castile and Portugal 1480 Ferdinand Magellan born 1481 King Afonso V of Portugal dies; his son João becomes king — Pope Sixtus IV issues Aeterni Regis, sanctioning the terms of the Treaty of Alcáçovas and affirming Portuguese claims south and east in the Atlantic Ocean 1484 Columbus first proposes his “Enterprise of the Indies” to João II 1486 Rebuffed in Portugal, Columbus travels to Castile to persuade Isabella and Ferdinand 1488 Bartolomeu Dias rounds the southern tip of Africa for Portugal 1492 Rodrigo Borgia becomes pope — Fall of the Kingdom of Granada — Christopher Columbus sails across the Atlantic Ocean for Isabella and Ferdinand — Beginning of the expulsion of the Jews from Castile 1493 Pope Alexander vi issues the bull Inter Caetera and other bulls, dividing the world between Spain and Portugal 1494 The Treaty of Tordesillas is signed between Portugal and Spain 1497 English King Henry vii funds the voyage of John Cabot 1504 Queen Isabella dies 1506 Columbus dies 1513 Vasco Nuñez de Balboa crosses the Isthmus of Panama and beholds the Pacific Ocean 1517 Martin Luther nails his Ninety-Five Theses to the church door in Wittenberg 1519 Ferdinand Magellan sets off to circumnavigate he world for Charles i of Spain — Hernán Cortés launches expedition to conquer Mexico 1521 Martin Luther excommunicated 1523 Pedro de Alvarado subjugates the Mayans in the Yucatán 1524 Badajoz Conference to determine the Tordesillas Line in the Pacific 1529 Treaty of Zaragoza; Spain cedes the Spice Islands to Portugal 1533 Francisco Pizarro conquers the Inca Empire 1537 Pope John ii rescinds the papacy's support of slavery 1558 Elizabeth becomes queen of England 1562 Sir John Hawkins and the first English privateering voyage to the Caribbean 1565 Andrés de Urdaneta pioneers the Pacific route from Manila to Acapulco 1568 Inquisition declares the three million people of the United Provinces, who have strongly embraced Calvinism, to be heretics and condemned to death 1571 Battle of Lepanto; destruction of Ottoman naval power in the Mediterranean 1570s—1580s English privateers inspired by the famous voyages of Sir Francis Drake 1581 Philip II of Spain becomes king of Portugal, uniting the countries and creating a near-monopoly on oceanic trade from Europe 1583 Hugo Grotius, “the Father of International Law,” born in Delft 1588 Spanish Armada fails to conquer England 1600 English East India Company founded 1602 Dutch East India Company founded; Amsterdam stock exchange founded to deal in the company's stocks and bonds — The Portuguese ship Santa Catarina captured by a Dutch privateer 1609 Henry Hudson sails up the Hudson River for the Dutch East India Company — Hugo Grotius anonymously publishes Mare Liberum, “The Free Sea” 1610 Vatican places Mare Liberum on its Index of prohibited and banned books 1613 Scottish challenge to Mare Liberum by William Welwood: Abridgement of All Sea-Lawes 1618 John Selden writes Mare Clausum 1618—1648 Thirty Years War devastates central Europe 1620 Mayflower pilgrims arrive at Cape Cod and Plymouth Rock 1623 Dutch East India Company employees kill English East India Company employees during the Massacre of Amboyna 1625 Seraphim de Freitas publishes Imperio Lusitanorum Asiatico to challenge Grotius 1655 English forces capture Jamaica and turn it into a buccaneer haven 1670 In the American Treaty, Spain recognizes the legitimacy of the British colonies in North America 1702 Cornelius Bynkershoek publishes De Domino Maris, establishing the concept of territorial waters and the cannon shot rule 1750 Treaty of Madrid between Spain and Portugal recognizes Portuguese sovereignty over Brazil and effectively annuls the Treaty of Tordesillas 1757 The Battle of Plassey; English East India Company rule in India begins 1768—1761 Lieutenant James Cook leads his first voyage of discovery in the Pacific 1775—1783 The American War of Independence 1776 Adam Smith publishes The Wealth of Nations 1994 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea { acknowledgements } TURNING A manuscript into a beautiful book is not a lone endeavour.

The Rough Guide to South America on a Budget (Travel Guide eBook)

by

Rough Guides

Published 1 Jan 2019

c.1000 AD Tiwanaku dramatically collapses, most likely as a result of a prolonged drought. Eleventh to fifteenth centuries The Aymara take control of the Altiplano, maintaining a more localized culture and religion. Mid-fifteenth century The Aymara are incorporated into the Inca Empire, albeit with a limited degree of autonomy. 1532 Francisco Pizarro leads his Spanish conquistadors to a swift and unlikely defeat of the Inca army in Cajamarca (Bajo), Peru. 1538 Pizarro sends Spanish troops south to aid the Aymaran Colla as they battle both the remnants of an Inca rebellion and their Aymara rivals the Lupaca. Spanish control of the territory known as Alto Peru is established. 1545 The continent’s richest deposit of silver, Cerro Rico, is discovered, giving birth to the mining city of Potosí. 1691 San Javier is founded as the first of the Chiquitos Jesuit missions. 1767 The Spanish Crown expels the Jesuit order from the Americas. 1780–82 The last major indigenous uprising, the Great Rebellion, is led by a combined Inca-Aymara army of Túpact Amaru and pac Katari. 1809 La Paz becomes the first capital in the Americas to declare independence from Spain. 1824 The last Spanish army is destroyed at the battle of Ayacucho in (Bajo) Peru. 1825 The newly liberated Alto Peru rejects a union with either (Bajo) Peru or Argentina, and adopts a declaration of independence.

…

Norte Grande, Norte Chico, Middle Chile and the Pacific island territories, however, can be accessed all year round. Chronology 1520 Ferdinand Magellan is the first European to sail through what is now the Magellan Strait. 1536 Expedition from Peru to Chile by conquistador Diego de Almagro and his four hundred men ends in death for most of the party. 1541 Pedro de Valdivia, a lieutenant of Francisco Pizarro, founds Santiago; a feudal system in which Spanish landowners enslave the indigenous population is established. 1808 Napoleon invades Spain and replaces Spanish King Ferdinand VII with his own brother. 1810 The criollo elite of Santiago decide Chile will be self-governed until the Spanish king is restored to the throne. 1817 Bernardo O’Higgins defeats Spanish royalists in the Battle of Chacabuco with the help of Argentine general José San Martín, as part of the movement to liberate South America from colonial rule. 1818 Full independence won from Spain.

…

Chronology 8000 BC The oldest archeological evidence of human settlement found in today’s Ecuador dates from around 8000 BC. 4000 BC The Valdivia culture develops one of the earliest ceramic techniques in the Americas. 1460 AD Tupac Yupanqui leads the first Inca invasion of Ecuador. 1495 Huayna Capac conquers territory up to Pasto, now in Colombia, despite violent resistance. He dies in Quito. 1532 Atahualpa defeats his half-brother Huascar in an Inca civil war, but is captured and executed by Spanish conqueror Francisco Pizarro. 1541 Francisco de Orellana journeys down the Amazon and reaches the Atlantic. 1809 On August 10, Quito declares independence from Napoleonic Spain. 1822 On May 24, Quito wins independence at the Battle of Pichincha. Bolívar’s dream of a united continent dies and Ecuador secedes from Colombia in 1830. 1861 Ultramontane Gabriel García Moreno gains power, quashes rebellions and makes Catholicism a prerequisite for all citizens.

Viruses: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions)

by

Crawford, Dorothy H.

Published 27 Jul 2011

Whole tribes were wiped out, and the population dropped by 90% over the following 120 years. When the Spanish invaders arrived, the Aztecs in Mexico and the Incas in Peru each had a population of 20 to 30 million, with massive armies. Nevertheless, in 1521 Hernando Cortés defeated the Aztecs with around 600 soldiers, and Francisco Pizarro similarly conquered the Incas with just 200 men in 1532. Both men were aided by smallpox, possibly combined with other microbes, that concomitantly killed up to half the population, leaving the survivors so confused and demoralized that the Spanish invaders had easy victories. Plant viruses have also had their moments of glory, and one such occurred during the 17th century when ‘tulipmania’ hit Holland.

The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World

by

Niall Ferguson

Published 13 Nov 2007

And, as under Communism, the economy depended on often harsh central planning and forced labour. In 1532, however, the Inca Empire was brought low by a man who, like Christopher Columbus, had come to the New World expressly to search for and monetize precious metal.c The illegitimate son of a Spanish colonel, Francisco Pizarro had crossed the Atlantic to seek his fortune in 1502.4 One of the first Europeans to traverse the isthmus of Panama to the Pacific, he led the first of three expeditions into Peru in 1524. The terrain was harsh, food scarce and the first indigenous peoples they encountered hostile. However, the welcome their second expedition received in the Tumbes region, where the inhabitants hailed them as the ‘children of the sun’, convinced Pizarro and his confederates to persist.

…

The passage was a translated extract from ‘Les Amis de Quatre Millions de Jeune Travailleurs’, Un Monde sans Argent: Le Communisme (Paris, 1975-6): http://www.geocities.com/~johngray/stanmond.htm. 2 Indeed, Marx and Engels had themselves recommended not the abolition of money but ‘Centralization of credit in the hands of the state, by means of a national bank with state capital and an exclusive monopoly’: clause 5 of The Communist Manifesto. 3 JuanForero,‘Amazonian Tribe Suddenly Leaves Jungle Home’, 11 May 2006: http://www.entheology.org/edoto/anmviewer.asp?a=244. 4 Clifford Smyth, Francisco Pizarro and the Conquest of Peru (Whitefish, Montana, 2007 [1931]). 5 Michael Wood, Conquistadors (London, 2001), p. 128. 6 For a vivid account from the conquistadors’ vantage point, which makes it clear that gold was their prime motive, see the November 1533 letter from Hernando Pizarro to the Royal Audience of Santo Domingo, in Clements R.

The Starfish and the Spider: The Unstoppable Power of Leaderless Organizations

by

Ori Brafman

and

Rod A. Beckstrom

Published 4 Oct 2006

Within eighty days, 240,000 inhabitants of the city starved to death. By 1521, just two years after Cortes first laid eyes on Tenochtitlan, the entire Aztec empire—a civilization that traced its roots to centuries before the time of Christ—had collapsed. The Aztecs weren't alone. A similar fate befell the Incas. The Spanish army, led by Francisco Pizarro, captured the Inca leader Atahuallpa in 1532. A year later, with all the Inca gold in hand, the Spanish executed Atahuallpa and appointed a puppet ruler. Again, the annihilation of an entire society took only two years. These monumental events eventually gave the Spanish control of the continent.

A Voyage Long and Strange: On the Trail of Vikings, Conquistadors, Lost Colonists, and Other Adventurers in Early America

by

Tony Horwitz

Published 1 Jan 2008

Not until 1508 did colonists start exploiting nearby islands the Admiral had found—Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Cuba—where they repeated the grim cycle of subjugating natives and importing Africans when Indian labor gave out. Then, beginning in 1513, Spain’s small realm exploded out of the Caribbean. Vasco Núñez de Balboa reached the Pacific; Ferdinand Magellan crossed it, after rounding South America. Hernán Cortés conquered the Aztec of Mexico, Francisco Pizarro the Inca of Peru. By 1542, the fiftieth anniversary of Columbus’s first sail, Spain had laid claim—and often laid waste—to an empire larger than Rome’s at its peak. One engine behind this extraordinary conquest was Spain’s crusading zeal. The vanquishing of Muslim armies at home had infused Iberians with a confidence and fervor that spilled over to America.

…

The riches of the Aztec exceeded the wildest rumors that had circulated since Columbus’s landing in America. With a small but determined force, led by a hidalgo as bold and ruthless as Cortés, what fortunes remained to be found in lands the Spanish had not yet conquered? LIKE MOST AMERICANS, I’d learned a little about Cortés in grade school, along with his most famous successor, Francisco Pizarro, the illiterate pig farmer who became conqueror of Peru. As a teenager, I listened to Neil Young wail “Cortez the Killer” and watched my loinclothed brother play a guard to the Inca emperor Atahualpa in The Royal Hunt of the Sun. But “conquistador” was a term I associated with Mexico and Peru.

Lonely Planet Panama (Travel Guide)

by

Lonely Planet

and

Carolyn McCarthy

Published 30 Jun 2013

Cerrito Tropical B&B $$ ( 390-8999; www.cerritotropicalpanama.com; d/apt incl breakfast from US$88/110; ) This smart Canadian and Dutch–owned B&B occupies a quiet nook atop a steep road. Rooms are stylish, some are more spacious and not all feature TVs. Meals ranging from burgers to seafood are available on a large shady deck until 8pm. Extras include BBQs and picnic lunches. To get here, go right uphill at the end of Calle Francisco Pizarro. It can also arrange tours such as fishing, hiking and whale-watching, and daytime packages with lunch and showers for nonguests. Zoraida’s Cool GUESTHOUSE $$ ( 6566-9250, 6471-1123; s/d/tr US$35/45/50) Overlooking the bay, this turquoise house is run by Rafael, the widow of Zoraida. Rooms are small and mattresses plastic-wrapped, but it’s the cheapest around.

…

After Panamá burnt to the ground, the Spanish rebuilt the city a few years later on a cape several kilometers west of its original site. The ruins of the old settlement, now known as Panamá Viejo, as well as the colonial city of Casco Viejo, are both located within the city limits of present-day Panama City. The famous crossing of the isthmus included 1000 indigenous slaves and 190 Spaniards, including Francisco Pizarro, who would later conquer Peru. Of course, British privateering didn’t cease with the destruction of Panamá. In 1739 the final nail in the coffin was hammered in when Admiral Edward Vernon destroyed the fortress of Portobelo. Humiliated by their defeat and robbed of one of their greatest defenses, the Spanish abandoned the Panamanian crossing in favor of sailing the long way around Cape Horn to the western coast of South America.

The Blood of Heroes: The 13-Day Struggle for the Alamo--And the Sacrifice That Forged a Nation

by

James Donovan

Published 14 May 2012

TWO “O! He Has Gone to Texas” A vast howling Wilderness of wild things, wild cattle wild Horses wild Beasts and Birds, and wild Men savages hostile in the extreme… JAMES HATCH, Lest We Forget the Heroes of the Alamo The very earliest explorers—Spanish conquistadors such as Hernán Cortés, Francisco Pizarro, and Francisco Vásquez de Coronado—marched deep into the heart of the wilderness in search of gold and other precious minerals. The kingdom of Gran Quivira, where everyone ate from dishes and bowls of gold… the Seven Hills of the Aijados, where gold was even more plentiful… the Sierra de la Plata, or the Silver Mountain—all these had lured men seeking fortunes.

…

As is abundantly evident from his actions and his dispatches—and his readings, from Porter’s The Scottish Chiefs to Scott’s Waverley novels—he possessed a taste for the romantic and a flair for the eloquently dramatic. The speech and the line would have been entirely in character—and not without precedent in history, from Francisco Pizarro to Ben Milam, who either drew a line in the dirt or asked his men to step across a line or path already there. As for Moses Rose, he did himself no favors with his story, since he knew others would view his actions as cowardly. It would have made much more sense to either keep his existence in the Alamo quiet or to claim that he had been sent out from the fort as a scout or courier.

Fall of Civilizations: Stories of Greatness and Decline

by

Paul Cooper

Published 31 Mar 2024

Atahualpa was now well on his way to becoming the thirteenth Sapa Inca, the next in a line of kings that stretched back a hundred years to the reign of Pachacuti. His land may have lain in ruins, his people may have been ravaged by disease and war, but the entire world now seemed to bow down before him. * * * Playing opposite Atahualpa in this drama is a man named Francisco Pizarro. Pizarro was born in 1478 in Extremadura in south-eastern Spain, then part of the kingdom of Castile. There is no official record of Pizarro’s birth, suggesting he may have been illegitimate, and he began his life herding pigs in the dusty town of Trujillo. After an early career as a mercenary, in 1502 he sailed to Hispaniola, where he earned a considerable fortune as a slaver, plantation owner and trader.

…

Even if they tried to endure their lot with resignation, they would still be liable to be arrested, tied to a pillar and flogged. And if they rebelled and attempted to kill their persecutors, they would certainly go to their death on the gallows.45 It is unlikely that the Spanish King ever read it. The document made its way to Denmark, where it lay undiscovered until the early twentieth century. * * * Francisco Pizarro had dreamed of surpassing Cortés in the glory of conquest, and by many measures, he had succeeded. Pizarro had destroyed an empire ten times the size of the Aztec Empire, using only about a third of the manpower, and he and his men were now rich beyond their wildest imaginings. ‘When in ancient or modern times has so great an enterprise been undertaken by so few against so many odds,’ revelled Xerez, ‘and to so varied a climate and seas, and at such great distances, conquer the unknown?’

Strength in Numbers: How Polls Work and Why We Need Them

by

G. Elliott Morris

Published 11 Jul 2022

Although it is unclear what counts of people were used for, they may have helped workers distribute food to residents or divvy up agricultural labors.9 Other examples of early censuses are much more recent. The Incas, who inhabited the Andes Mountains region of South America around 1430–1570 CE, are often theorized to have recorded population counts on strings tied in knots called khipu. Writing a few hundred years after the Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro wiped them out, Martín de Murúa recorded: They sent every five years quipucamayos [khipu-keepers], who are accountants and overseers, whom they call tucuyricuc. These came to the provinces as governors and visitors, each one to the province for which he was responsible and, upon arriving at the town he had all the people brought together, from the decrepit old people to the newborn nursing babies, in a field outside town, or within the town, if there was a plaza large enough to accommodate all of them; the tucuyricuc organized them into ten rows [“streets”] for the men and another ten for the women.

The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity's Search for Meaning

by

Jeremy Lent

Published 22 May 2017

History, as the saying goes, is the story told by the victors, and the same holds true for cosmologies. At the birth of Neo-Confucianism, the glorious Song capital of Kaifeng had a population thirty times greater than London's. By the time of Wang Yang-ming's death in 1529, the tables were turning. That year, the Spaniard Francisco Pizarro was appointed governor of the New World territory of Peru. The Muslim incursion of Europe reached its high-water mark with a failed siege of Vienna, the beginning of a seismic shift in the balance of power between the two great monotheistic creeds. At the Diet of Speyer, a group of German rulers kicked off the Protestant movement that would shake up the Catholic hegemony over Christendom.

…

With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.”36 Within a few short years, these musings of power and exploitation would come true beyond Columbus's wildest dreams. Some of the most astonishing stories in history recount the way the greatest empires of the New World—the Aztecs and the Incas—were laid waste by two small bands of Spanish explorers led respectively by Hernando Cortés and Francisco Pizarro. When Cortés first arrived at the gates of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán in 1519 with fewer than a thousand Spanish soldiers, his entire group could have been wiped out by the Aztecs, whose formidable warriors firmly controlled the central region of Mexico. Instead, they were welcomed in friendship and invited into the city to join a festive celebration.

The botany of desire: a plant's-eye view of the world

by

Michael Pollan

Published 27 May 2002

The genetic diversity cultivated by the Incas and their descendants is an extraordinary cultural achievement and a gift of incalculable value to the rest of the world. A free and unencumbered gift, one might add, quite unlike my patented and trademarked NewLeafs. “Intellectual property” is a recent, Western concept that means nothing to a Peruvian farmer, then or now.* Of course, Francisco Pizarro was looking for neither plants nor intellectual property when he conquered the Incas; he had eyes only for gold. None of the conquistadores could have imagined it, but the funny-looking tubers they encountered high in the Andes would prove to be the single most important treasure they would bring back from the New World

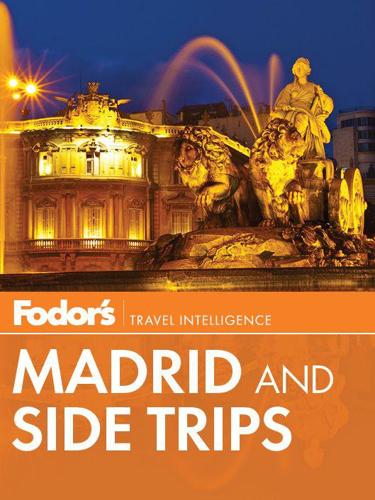

Fodor's Madrid and Side Trips

by

Fodor's

Published 16 May 2011

With its poor soil and minimal industry, Extremadura never experienced the kind of modern economic development typical of other parts of Spain, but no other place in Spain has as many Roman monuments as Mérida, capital of the vast Roman province of Lusitania, which included most of the western half of the Iberian Peninsula. Mérida guarded the Vía de la Plata, the major Roman highway that crossed Extremadura from north to south, connecting Gijón with Seville. The economy and the arts declined after the Romans left, but the region revived in the 16th century, when explorers and conquerors of the New World—from Francisco Pizarro and Hernán Cortés to Francisco de Orellana, first navigator of the Amazon—returned to their birthplace. These men built the magnificent palaces that now glorify towns such as Cáceres and Trujillo, and they turned the remote monastery of Guadalupe into one of the great artistic repositories of Spain.

The Decadent Society: How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success

by

Ross Douthat

Published 25 Feb 2020

Since we know that the Spanish are lurking just offstage, this portrait of Mesoamerica before the fall fits the epigraph that Gibson gives the film, a line from the historian Will Durant: “A great civilization is not conquered from without until it has destroyed itself from within.” The movie is great, but the epigraph is wrong, and the real history of pre-Columbian America is a counterpoint rather than an example of Durant’s claim. There were problems in the great Native empires, of course, weaknesses and corruptions and internal divisions that Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro were able to exploit. But there is no certain proof that the Aztec or Inca empires were at maximally decadent phases of their existence overall, no sense that the fall of either Montezuma or the Great Inca was somehow predictable given just the evidence of what was happening within their pre-Columbian domains.

The Journey of Humanity: The Origins of Wealth and Inequality

by

Oded Galor

Published 22 Mar 2022

The microbes they imported often spread more quickly than the invaders themselves; they annihilated the Inca population before the Spanish even set foot in the Andes. According to most accounts, the Incan emperor Huayna Capac was felled in 1524 by smallpox or measles which had struck his empire, and the resulting war of succession that unfolded between his sons enabled a small Spanish force with superior arms led by Francisco Pizarro to conquer the Inca Empire. In North America, the Pacific islands, Southern Africa and Australia, large swathes of the indigenous populations were similarly wiped out shortly after the first Europeans laid anchor and sneezed, spreading germs that had sailed with them from Europe. On every continent, early agricultural civilisations typically used their larger populations and greater technological power either to displace hunter-gatherers, pushing some to remote corners while destroying others, or to integrate them.[5] In some encounters, hunter-gatherers adopted agriculture and changed their subsistence strategy more spontaneously.[6] In fact, when Europeans arrived on their shores, some of Central and South America’s indigenous populations had already transitioned to agriculture thousands of years previously.

Rick Stein's Spain: 140 New Recipes Inspired by My Journey Off the Beaten Track

by

Rick Stein

Published 15 Dec 2011

Much of Trujillo and nearby Cáceres is slightly falling down, a bit like the Lost Gardens of Heligan in Cornwall. You feel that you participate more in enjoying the reality of somewhere that’s not perfect. The Pizarro mansion across the square from the statue is quietly crumbling too; even the friezes on the corner of the ‘House of the Conquistador’ are cracking. The busts of Francisco Pizarro and his wife the princess Inés Yupanqui, sister of the Inca Emperor Atahualpa, look out over a town of towers and turrets. Atahualpa, you may remember, having been capured by Pizarro, offered a large room filled with gold for his freedom. Pizarro took the gold but executed him anyway – by garotte, a kinder way to die than burning at the stake, from which the emperor was spared by having converted to Catholicism.

The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution

by

Francis Fukuyama

Published 11 Apr 2011

Cortés began his conquest of Mexico in 1519, the year before the outbreak of the great comunero revolt; as a result of the outcome of that struggle, the political institutions transferred to the Americas would not include a strong Cortes or other types of representative bodies. The only early bid for political independence was the revolt of Francisco Pizarro’s brother Gonzalo, who tried to set himself up as an independent king of Peru. He was defeated and executed by royal troops in 1548, and no further challenges to central authority from the New World Spaniards occurred until the wars of independence of the early nineteenth century. The Spanish authorities did transfer their Roman legal system, establishing high courts or audiencias in ten places, including Santo Domingo, Mexico, Peru, Guatemala, and Bogotá.

…

North Korea Northrup, Linda Norway Novgorod, republic of Nubia Nuer Nueva Recopilacion Oceania Ogedei, Great Khan Old Regime and the Revolution, The (Tocqueville) oligarchy; in China; in England; in France; in Hungary; in Mexico; in Spain; in United States Olson, Mancur On the Origin of Species (Darwin) Orange Revolution Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development Oriental despotism Orthodox Christianity, see Eastern church Osman Ostrom, Elinor Ottoman Empire; agrarian society in; census in; corruption in; decay of; European wars of; Hungary conquered by; legacy of; Mamluk sultanate defeated by; military slavery in; rule of law in; Russia compared to; sanjaks of; state as governing institution in; sultan’s elite troops in, see Janissaries Oxford, University of Pakistan Paleolithic era Palestine Pandyas Papua New Guinea (PNG); Big Man in; tribal law in Paris, University of Park Chung Hee Parlement de Paris Parliament, English; in Civil War; Enclosure Movement of; solidarity in; taxation and Parliament, Indian Parsons, Talcott Partido Justicialista, Argentine Pascal, Blaise Paschal II, Pope Pashtuns Passover Patriarchal caliphate patrilineal societies; see also agnation patrimonialism; in Africa; in China ; in Catholic church; in England; feudalism and; in France; in Hungary; in India; in Latin America; in Mamluk sultanate; of Mauryas; in Ottoman Empire; in Prussia; in Russia; in Spain; see also repatrimonialization patronage; Catholic church and; in China; in England; in India; in Mexico; in Russia; in United States Pauite Indians Paulet, Charles peasants; in China ; in Denmark; in England; in feudal and early modern Europe; in France; in Hungary; in India; in Mamluk state; in Ottoman Empire; in Russia; in Scandinavia; uprisings of; see also serfdom People’s Liberation Army, Sudan People’s Republic of China; collectivization in; corruption in; Cultural Revolution in; economic growth of; legal system in; progressive radicalization in Pepys, Samuel Péron, Juan Perry, Commodore Matthew Persia; absolutism in; in Ghaznavid empire; Indo-Aryan tribes in; in Mauryan empire; patrimonialism in; under Safavids Peru Peter I (the Great), Tsar of Russia Philip II, King of Spain Philip III, King of Spain Philip IV, King of Spain Philippines Pinker, Steven Pinochet, Augusto Pipes, Daniel Pirenne, Henri Pizarro, Francisco Pizarro, Gonzalo plagues Plato Poitiers, Battle of Poland Political Order in Changing Societies (Huntington) Pollock, Frederick Pompey Pontchartrain, Louis Phélypeaux, comte de Pool, Ithiel de Sola Portugal Praetorian Guards Prince, The (Machiavelli) Pritchett, Lant private property; agriculture and; in communist theory; kinship and; offices as; tragedy of the commons and; see also property rights property rights; in China, in China; in England; in France; intellectual; in Malthusian economy; in Mexico; in Muslim world; in Spain; rule of law and; in Russia Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, The (Weber) Protestantism; see also Reformation Prozac Prussia; rule of law in; serfdom in Pueblo Indians Puritans Putin, Vladimir Qadisiyyah, Battle of Qaim, Caliph al- Qalawun, Sultan Qansuh al-Ghawri, Sultan Qiang tribe Qin, state of; kinship in; military success of; Shang Yang’s reforms in; see also Qin dynasty Qin Dynasty; common culture developed by; Confucian resistance to; Great Wall of; Legalism of; repatrimonialization following; unification of China under 144 Qing Dynasty Qin Shi Huangdi qiu system Quakers Quraysh tribe Rajasthan, gana-sangha chiefdoms of Rajputs Reagan, Ronald Rectification of Names Red Eyebrows uprising Red Turban uprising Reformation; in Denmark; invention of printing press and; rule of law and; Russia insulated from; Weber on economic framework based in Religion of China (Weber) Renaissance repatrimonialization Republic, The (Plato) republicanism, classical Republican Party, U.S.

The Big Ratchet: How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis

by

Ruth Defries

Published 8 Sep 2014

These engines of the trade winds are sometimes called the Hadley cells, a name honoring the English amateur meteorologist George Hadley, who noted the link between the rotating Earth and the trade routes of his era in 1735. The trade winds carried Columbus westward, where he landed in the Bahamas in October 1492. He returned via the northward loop of a Hadley cell that blows winds eastward toward Europe. The New World that Columbus opened to other conquistadors and explorers—Hernando Cortés, Francisco Pizarro, and Vasco Nuñez de Balboa—during the wind-powered Age of Discovery had little resemblance to the Old World. Reconstruction of Columbus’s diaries note his observation that “all the trees are as different from ours as day from night; and also the fruits and grasses and stones and everything.” This difference was not to last.

Down in the Bottomlands

by

Harry Turtledove

and

Lyon Sprague de Camp

Published 14 Jun 1999

The Son of the Sun and his kin worship one square over, in the plaza called Awkaipata. There you would see gold and silver used in a truly lavish way." "This is lavish enough for me," Park muttered. Just one link of that chain, he thought, and he wouldn't have to worry about money for the rest of his life. For the first time, he understood what Francisco Pizarro must have felt when he plundered the wealth of the Incas back in Park's original world. He'd always thought Pizarro the champion bandit of all time, but the sight of so much gold lying around loose would have made anyone start breathing hard. Several men strode out onto a raised platform at the front of the square.

Rope: How a Bundle of Twisted Fibers Became the Backbone of Civilization

by

Tim Queeney

Published 11 Aug 2025

MANY MATERIALS Khipu are probably most often associated with the Inca Empire (the Incans called their empire Tawantinsuyu, or “the Realm of the Four Parts”). From 1438 to 1533 the empire held sway over an expanse of 770,000 square miles, from Ecuador in the north to Chile and Argentina in the south. In a sad story of European colonial conquest that was repeated throughout the Americas, the Spanish under Francisco Pizarro defeated Incan forces and by 1533 had taken control of Tawantinsuyu. While khipu were an important part of imperial administration, the Incans were not the inventors of the khipu. The Wari Empire, which ruled in Peru from 600 CE to about 1100 CE, also used khipu. And not only the Wari. Knotted cord devices were widely used throughout the world.

Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World

by

Laura Spinney

Published 31 May 2017

Finding that the world grew cooler in the late Roman era, for example, they suggest that the Plague of Justinian–a pandemic of bubonic plague that killed approximately 25 million people in Europe and Asia in the sixth century AD–led to vast tracts of farmland being abandoned and forests growing back. Trees extract carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and this reforestation led to so much of the gas being sequestered in wood that the earth cooled (the opposite of the greenhouse effect we are witnessing today). Similarly, the massive waves of death that Cortés, Francisco Pizarro (who conquered the Inca Empire in Peru) and Hernando de Soto (who led the first European expedition into what is now the United States) unleashed in the Americas in the sixteenth century caused a population crash that may have ushered in the Little Ice Age.6 The effect wasn’t reversed until the nineteenth century, when more Europeans arrived and began to clear the land again.

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything

by

David Christian

Published 21 May 2018

Within fifty years of Columbus’s first voyage, the Portuguese had used their armed caravels to build fortified strong points that bolted together a trading empire in the Indian Ocean. The risks for merchants and sailors were huge, but so were the potential profits. In the Americas, Spanish conquistadores, such as Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro, seized control of the rich civilizations of the Aztecs and Incas. They did so with tiny armies that exploited political divisions within both empires. But they were assisted by the devastating impact of European diseases such as smallpox that may have killed up to 80 percent of the population in America’s major empires and ruined ancient social structures and traditions.

Spain

by

Lonely Planet Publications

and

Damien Simonis

Published 14 May 1997

Three more voyages saw him founding the city of Santo Domingo on Hispaniola, finding Jamaica, Trinidad and other Caribbean islands, and reaching the mouth of the Orinoco and the coast of Central America, but he died impoverished in Valladolid in 1506, still believing he had reached Asia. Brilliant but ruthless conquistadors followed Columbus’ trail, seizing vast tracts of the American mainland for Spain. Between 1519 and 1521 Hernán Cortés conquered the fearsome Aztec empire with a small band of adventurers. Between 1531 and 1533 Francisco Pizarro did the same to the Inca empire, and by 1600 Spain controlled Florida, all the biggest Caribbean islands, nearly all of present-day Mexico and Central America, and a large strip of South America. The new colonies sent huge cargoes of silver, gold and other riches back to Spain, where the crown was entitled to one-fifth of the bullion (the quinto real, or royal fifth).

…

The square is surrounded by baroque and Renaissance stone buildings topped with a skyline of towers, turrets, cupolas, crenulations and nesting storks. Stretching beyond the square the illusion continues with a labyrinth of mansions, leafy courtyards, fruit gardens, churches and convents; Trujillo truly is one of the most captivating small towns in Spain. The town came into its own only with the conquest of the Americas. Then, Francisco Pizarro and his co-conquistadors enriched the city with a grand new square and imposing Renaissance mansions that look down confidently upon the town today. Information Ciberalia (927 65 90 87; Calle de Tiendas 18; per hr €2; 11am-midnight) Internet access. Post office (Calle de la Encarnación 28) Tourist office (927 32 26 77; www.ayto-trujillo.com in Spanish; Plaza Mayor s/n; 10am-2pm & 4-7pm Oct-May, 10am-2pm & 5-8pm Jun-Sep) Sights PLAZA MAYOR There are a handful of feeble museums in Trujillo.

…

It also has tombs of leading Trujillo families of the Middle Ages, including that of Diego García de Paredes (1466–1530), a Trujillo warrior of legendary strength who, according to Cervantes, could stop a mill wheel with one finger. The church’s magnificent altarpiece includes 25 brilliantly coloured 15th-century paintings in the Flemish style. Cheese-and-wine aficionados may enjoy the Museo de Queso y el Vino (927 32 30 31; Calle Francisco Pizarro s/n; admission €2.30) where you can have a taster of both and take a look at the informative display (in Spanish) of wine and cheese in Spain. Set in this fine old former convent, the 4m three-dimensional picture of a jolly Don Quijote is the stunning work of local artist Francisco Blanco. At the top of the hill Trujillo’s castle (927 32 26 77; Calle del Convento de las Jerónimas 12; ) of 10th-century Muslim origin (evident by the horseshoe-arch gateway just inside the main entrance) and later strengthened by the Christians, is impressive, although bare but for a lone fig tree.

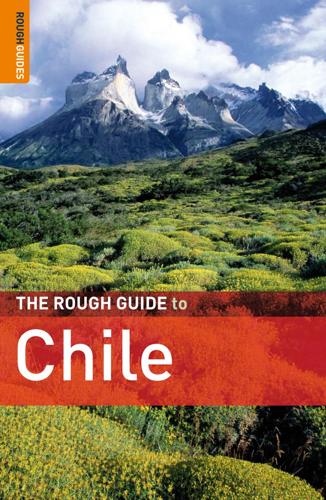

The Rough Guide to Chile & Easter Island (Travel Guide with Free eBook)

by

Rough Guides

Published 15 Mar 2023

West of the centre, the once glamorous barrios that housed Santiago’s moneyed classes at the beginning of the twentieth century make for rewarding, romantic wanders, and contain some splendid old mansions and museums. As you move east into Providencia and Las Condes, the tone is newer and flasher, with shiny malls and upmarket restaurants, as well as the crafts market at Los Dominicos. Brief history In 1540, some seven years after Francisco Pizarro conquered Cuzco in Peru, he dispatched Pedro de Valdivia southwards to claim and settle more territory for the Spanish crown. After eleven months of travelling, Valdivia and his 150 men reached what he considered to be a suitable site for a new city and, on February 12, 1541, officially founded “Santiago de la Nueva Extremadura”, wedged into a triangle of land bounded by the Río Mapocho to the north, its southern branch to the south and the rocky Santa Lucía hill to the east.

…

After colonizing several other islands, the explorers and adventurers, backed by the Spanish Crown, turned their attention to the mainland, and the period of conquest began in earnest. The conquest of Peru and venture into Chile In 1521, Hernán Cortés defeated the great Aztec Empire in Mexico. Then, in 1524, Francisco Pizarro and his partner Diego de Almagro set out to find the rich empire they had been told lay further south. After several failed attempts, they finally landed on the coast of Peru in 1532, where they found the great Inca Empire racked by civil war. Pizarro speedily conquered the empire, aided by advanced military weapons and tactics, a frenzied desire for gold and glory and, most significantly, the devastating effect of diseases on the Indigenous population.

Dark Pools: The Rise of the Machine Traders and the Rigging of the U.S. Stock Market

by

Scott Patterson

Published 11 Jun 2012

It all went back to the eighteenth century, when the Spanish dollar, buoyed by conquests in the Americas, served as the world’s currency. Spanish merchants often sliced up doubloons into eight pieces as forms of payment—so-called pieces of eight. Hence, U.S. stock prices traded in eighth-of-a-dollar slices because conquistadors such as Hernando Cortés and Francisco Pizarro hacked their way across North and South America centuries before. Levine thought the convention was not only antiquated, it was outright theft. It made spreads artificially wide, handing outsize profits to market makers and specialists. It was as if a car dealer who bought a Mustang from Ford for $30,000 could only resell it for $35,000.

Lonely Planet's Best of USA

by

Lonely Planet

Plaque commemorating the Declaration of Independence / RICHARD CUMMINS / GETTY IMAGES © Enter the Europeans In 1492 the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus, backed by the monarchy of Spain, voyaged west by sea, looking for the East Indies. With visions of gold, Spanish explorers quickly followed: Hernán Cortés conquered much of today’s Mexico; Francisco Pizarro conquered Peru; Juan Ponce de León wandered through Florida looking for the fountain of youth. Not to be left out, the French explored Canada and the Midwest, while the Dutch and English cruised North America’s eastern seaboard. Of course, they weren’t the first ones on the continent. When Europeans arrived, between two million and 18 million Native American people occupied the lands north of present-day Mexico and spoke more than 300 languages.

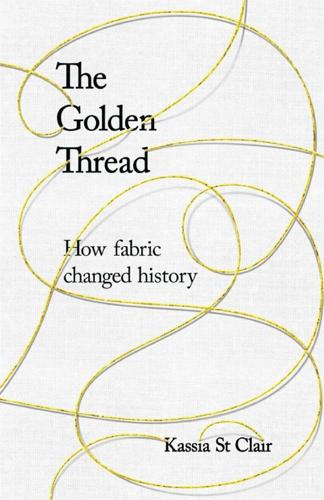

The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History

by

Kassia St Clair

Published 3 Oct 2018

One of the reasons why Christopher Columbus was so convinced that he had reached India in 1492 when he was, in fact, in the Caribbean, was that the islands were filled with cotton shrubs. On his first encounter with Arawak men and women, he wrote in his log that: ‘They brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things.’ Francisco Pizarro too, when he reached the Inca Empire in what is now Peru in 1532, was impressed by the quality of textiles they produced, remarking that they were: ‘far superior to any they had seen, for fineness of texture, and the skill with which various colours were blended’.35 As elsewhere, however, up until the late eighteenth century, cotton remained one of many crops grown on a relatively small scale.

The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and Its Solutions

by

Jason Hickel

Published 3 May 2017

He proceeded with his march, destroying towns along the way and massacring their inhabitants in the squares, conquering by virtue of his superior weapons: cannons, crossbows and horses. When he arrived at Tenochtitlán, Emperor Montezuma welcomed him with marvellous gifts of gold and silver. Cortés imprisoned him in his own palace and took control of the city. By 1521, Montezuma had been killed and the capital plundered of its treasures. Francisco Pizarro, yet another Spanish conquistador, followed suit. In 1532 he was invited into the Inca capital in Peru by Emperor Atahuallpa, who – protected by an army of 80,000 men – did not consider Pizarro and his soldiers to be a threat. Yet Pizarro, enabled by his weapons, managed to sack the city and capture Atahuallpa.

A Hunter-Gatherer's Guide to the 21st Century: Evolution and the Challenges of Modern Life

by

Heather Heying

and

Bret Weinstein

Published 14 Sep 2021

When people from the Old World came across the Atlantic and landed in the New World, they may have at first imagined that they had stumbled upon a vast geographic frontier, but they hadn’t. In 1491, the New World is estimated to have had between fifty million and one hundred million people in it, with uncountable distinct cultures and languages. Some people were living in city-states, among astronomers, craftsmen, and scribes; others as hunter-gatherers.1 To Francisco Pizarro, the Inca Empire was a transfer of resource frontier. To the instigators of the rubber boom in western Amazonia at the end of the 19th century, the Zaparo territory was a transfer of resource frontier—and once the Zaparos were thus weakened, their longtime competitors, the Huaorani, moved in as well.2 In modern times, transfer of resource frontiers are everywhere: oil drilling, fracking, and logging in ancestral lands; predatory lending, as with subprime mortgages and much student debt; the Holocaust.

The Rough Guide to Chile

by

Melissa Graham

and

Andrew Benson

Published 11 May 2003

Dipping into Santiago’s vibrant theatre and music scene, getting a sense of its history in the city’s museums, and checking out its varied restaurants will really help you scratch beneath the surface and get the most out of your time in this kaleidoscopic country. The telephone code for Santiago is T 2. Telephone numbers that begin with 9 are mobile phones. When calling from a fixed line to a mobile, dial “09” plus the number. For mobile to mobile calls, begin with just “9”. For more telephone information see p.70. | Arrival Some seven years after Francisco Pizarro conquered Cuzco in Peru, he dispatched Pedro de Valdivia southwards to claim and settle more territory for the Spanish crown. After eleven months of travelling, Valdivia and his 150 men reached what he considered to be a suitable site for a new city, and, on February 12, 1541, officially founded “Santiago de la Nueva Extremadura”, wedged into a triangle of land bounded by the Río Mapocho to the north, its southern branch to the south and the rocky Santa Lucía hill to the east.

…

It gradually became apparent that the islands were not part of Asia, and that a giant landmass – indeed a whole continent – separated them from the East. After colonizing several other islands, the explorers and adventurers, backed by the Spanish Crown, turned their attention to the mainland, and the period of conquest began in earnest. In 1521 Hernán Cortés defeated the great Aztec Empire in Mexico and then in 1524 Francisco Pizarro and his partner Diego de Almagro set out to find the rich empire they had been told lay further south. After several failed attempts, they finally landed on the coast of Peru in 1532, where they found the great Inca Empire racked by civil war. Pizarro speedily conquered the empire, aided by advanced military weapons and tactics, the high morale of his men, their frenzied desire for gold and glory and, most significantly, the devastating effect of Old World diseases on the indigenous population.

Falling Behind: Explaining the Development Gap Between Latin America and the United States

by

Francis Fukuyama

Published 1 Jan 2006

The colonial societies that emerged were authoritarian and concentrated political power in the hands of a small group of Spanish elites, who created a set of economic institutions designed to extract wealth from the indigenous population and a set of political institutions designed to consolidate their power. After Francisco Pizarro conquered the empire of Tawantinsuyu in Peru and Bolivia, and following the model developed a decade earlier in Mexico by Hernán Cortés, he imposed a series of institutions designed to extract rents from the newly conquered natives. The main institutions that eventually emerged were the encomienda (which gave Spanish conquistadores the right to native labor), the mita (a system of forced labor used in the mines and for public works), and the repartimiento (the forced sale of goods to the native people, typically at highly inflated prices).

Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization

by

Iain Gately

Published 27 Oct 2001

Whilst other nations were making forays along the Atlantic coast of the New World, the Spaniards had discovered and subdued another empire equal in size and strength to that of the Aztecs. Their next victims, the Incas, occupied what is now Peru, and their domains were at their greatest in extent when the Spaniards arrived, although recently divided by a civil war. Francisco Pizarro, conqueror of the Incas, imitated his fellow countryman Cortés in seeking a meeting with the Inca ruler, took him hostage, then burned him at the stake in his own barracks. The Spaniards treated the Incas’ civilization in a similar manner to the Aztecs’. While they kept their roads they destroyed or depopulated the Incas’ cities, prohibited their religion and enslaved the remnants of their subjects.

Dark Laboratory: On Columbus, the Caribbean, and the Origins of the Climate Crisis

by

Tao Leigh. Goffe

Published 14 Mar 2025

They lived in fertile mountain slopes where they developed technologies of the soil. The Wari of Huari of the south-central Andean and coastal areas are understood as an economic network along the Pacific Coast.[20] As mountain residents, they were experts in tilling arid sloping land. Before Francisco Pizarro and the Spanish invasion of Peru in 1526, Indigenous agrarian traditions of cultivation valued guano’s regenerative properties across terraced slopes. The pathogens that arrived as part of a genocide have erased the scientific methods that thrived before. In what may have been the first recorded piece of climate legislation during the fourteenth century, Inca rulers decreed that hunting guano-producing birds was an offense punishable by death.[21] Not only did the Inca law protect the birds, but it also took into account long-term, sustainable agricultural cycles of cultivation.

The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor

by

William Easterly

Published 4 Mar 2014

Chinese peasants were sufficiently nonstatic to introduce a new technology that increased the calories, vitamins, and nutrients produced by a given amount of land, thus sustaining a larger population for a given amount of land. The new technology was called the potato. The Spanish had borrowed the potato from the South American Andes (in what is now Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Chile) after the conquest by Francisco Pizarro in 1532, and other Europeans learned about it from the Spanish. Chinese farmers learned about the potato from Dutch traders in the 1600s. The potato made it possible for farmers to plant in mountainous areas previously unsuitable for agriculture. Chinese farmers also substituted the potato for other crops that produced less food value per hectare, like barley, oats, and wheat.

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

by

Yuval Noah Harari

Published 1 Jan 2011

They immediately commenced explore-and-conquer operations in all directions. The previous rulers of Central America – the Aztecs, the Toltecs, the Maya – barely knew South America existed, and never made any attempt to subjugate it, over the course of 2,000 years. Yet within little more than ten years of the Spanish conquest of Mexico, Francisco Pizarro had discovered the Inca Empire in South America, vanquishing it in 1532. Had the Aztecs and Incas shown a bit more interest in the world surrounding them – and had they known what the Spaniards had done to their neighbours – they might have resisted the Spanish conquest more keenly and successfully.

The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community

by

David C. Korten

Published 1 Jan 2001

In search of a westward sea route to the riches of Asia, Christopher Columbus (1451–1506) landed on the island of Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic) in the West Indies in 1492 and claimed it for Spain. Hernando De Soto (1496–1542) made his initial mark trading slaves in Central America and later allied with Francisco Pizarro to take control of the Inca Empire based in Peru in 1532, the same year the Portuguese established their first settlement in Brazil. De Soto returned to Spain one of the wealthiest men of his time, although his share in the plunder was only half that of Pizarro.3 By 1521, Hernán Cortés had claimed the Mexican Empire of Montezuma for Spain.

The Old Patagonian Express

by

Paul Theroux

Published 23 Sep 1979

But I had the impression that Peruvian disgust was so keen that Paul Theroux The Old Patagonian Express, By Train Through the Americas Page 150 if it were to be combined with wealth the city of Lima would be destroyed and rebuilt to match the misguided modernity of Bogotá. I walked from the Cathedral (the mummy on view is not that of Francisco Pizarro: his skeleton has recently been found in a lead box in the crypt) to the University Park, and then made a circuit of the city, finally stopping at the Plaza Bolognesi where I sat and reflected on the melodrama of General Bolognesi's monument. It was the most bizarre statue I had seen so far.

New World, Inc.

by

John Butman

Published 20 Mar 2018