Frederick Jackson Turner

description: American historian (1861-1932)

71 results

Nature's Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West

by William Cronon · 2 Nov 2009 · 918pp · 260,504 words

American frontier expansion. Much as I may be uncomfortable with the shifting definitions that have plagued scholarly readings of frontier history since the days of Frederick Jackson Turner, I am convinced that regional redefinitions of the field are ultimately not much better, since I am quite confident that for much of the nineteenth

…

adequately acknowledge how much I have learned from reading the likes of Raymond Williams or Aldo Leopold or David Potter or Carl Sauer or even Frederick Jackson Turner or Karl Marx. But these acknowledgments would be radically incomplete if I did not mention three people whose classroom teaching and scholarly examples set me

…

nineteenth century. At Chicago’s famous Columbian Exposition of 1893—an event which many interpreted as the fulfillment of the city’s destiny—the historian Frederick Jackson Turner proposed for the first time his famous frontier thesis as an explanation of why the West had developed as it had. In offering what became

…

the boosters’ prophecy had actually come true.94 The West of the great emporium and its satellites bore little outward resemblance to the West of Frederick Jackson Turner’s frontier. In contrast to the boosters, Turner consistently chose to see the frontier as a rural place, the very isolation of which created its

…

from it, they did not produce it.7 Chicago and other cities of the Great West grew within the ecological context of what the historian Frederick Jackson Turner would have called “frontier” conditions. Despite all the ambiguities and contradictions that have bedeviled Turner’s frontier thesis for the past century, it still holds

…

in the Great West during the second half of the nineteenth century represented a new phase of American frontier expansion, far more rapid than anything Frederick Jackson Turner described.27 Its accelerated pace was driven by the new rail technologies, but the growth of Chicago’s metropolitan hinterland was an extension of the

…

story, then, is about the rise and fall of the greatest gateway city of the Great West. Viewed from Chicago, the process which the historian Frederick Jackson Turner described as the reenactment of social evolution in isolated frontier places has a very different meaning. From the heart of the city, the frontier history

…

Fergus, Fergus’ Directory of the City of Chicago, 1839 (1876), 37. 29.Buckingham, Eastern and Western States, 262. 30.Cleaver, History of Chicago, 84. 31.Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History (1920; reprint, 1962), 11. 32.Turner emphasized the supposedly progressive evolutionary stages of isolated frontier development in his most famous

…

the New West, 1819–1829 (1906). I assess Turner’s legacy more fully (and rather more favorably) in “Revisiting the Vanishing Frontier: The Legacy of Frederick Jackson Turner,” WHQ 18 (1987): 157–76; and in “Turner’s First Stand: The Significance of Significance in American History,” in Richard Etulain, ed., Writing Western History

…

hinterland’s development was undoubtedly much on people’s minds during the speculation of the 1830s. 95.Frederick Jackson Turner to Arthur M. Schlesinger, May 5, 1925, reprinted in Wilbur R. Jacobs, ed., The Historical World of Frederick Jackson Turner with Selections from His Correspondence (1968), 163–65; see also Arthur M. Schlesinger, “The City in

…

14 (1973): 16–30; Jackson K. Putnam, “The Turner Thesis and the Westward Movement: A Reappraisal,” WHQ 7 (1976): 377–404; Richard Jensen, “On Modernizing Frederick Jackson Turner: The Historiography of Regionalism,” WHQ 11 (1980): 307–22; Limerick, Legacy of Conquest; Peter Novick, That Noble Dream: The “Objectivity Question “ in the American Historical

…

Profession (1988), 86ff.; and Richard White, “Frederick Jackson Turner,” in John R. Wunder, ed., Historians of the American Frontier: A Bio-Bibliographical Sourcebook (1988), 660–81. 9.I have argued that this is likely

…

Frontier (1952); and David M. Potter, People of Plenty: Economic Abundance and the American Character (1954). I discuss this theme of abundance in relation to Frederick Jackson Turner in my “Revisiting the Vanishing Frontier.” For discussions that relate directly to lumbering, see D. C. Everest, “A Reappraisal of the Lumber Barons,” Wis. Mag

…

. Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1985. Jacobs, Wilbur R., ed. The Historical World of Frederick Jackson Turner with Selections from His Correspondence. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1968. James, Edwin. Account of an Expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains. 1823. Reprint

…

): 75–120. Cronon, William. “Modes of Prophecy and Production: Placing Nature in History.” JAH 76 (1990): 1122–31. ———. “Revisiting the Vanishing Frontier: The Legacy of Frederick Jackson Turner.” WHQ 18(1987): 157–76. ———. “To Be the Central City.” Chicago History 10 (1981): 130–40. ———. “Turner’s First Stand: The Significance of Significance in

…

Wheat.” Minn. Hist. 29 (1948): 1–28. Jefferson, Mark. “The Law of the Primate City.” Geographical Review 29 (1939): 226–32. Jensen, Richard. “On Modernizing Frederick Jackson Turner: The Historiography of Regionalism.” WHQ 11 (1980): 307–22. Johnson, Ronald N., and Gary D. Libecap. “Efficient Markets and Great Lakes Timber: A Conservation Issue

Seapower States: Maritime Culture, Continental Empires and the Conflict That Made the Modern World

by Andrew Lambert · 1 Oct 2018 · 618pp · 160,006 words

by the Royal Navy, in an era dominated by internal concerns. After 1815 the frontier controlled the shaping of American culture and identity. In 1898 Frederick Jackson Turner observed: ‘The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward explains American development.’ Jackson’s frontier

…

, et al., The Way of the Ship. 64. F. J. Turner, ‘The Significance of the Frontier in American History’, in J. M. Faragher, ed., Rereading Frederick Jackson Turner, New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 1998, pp. 30–60, at pp. 33, 43 and 59. It was hardly surprising that a man

…

named for President Andrew Jackson, the arch-exponent of continental expansion, should develop this argument. 65. Faragher, ed., ‘Introduction’, Rereading Frederick Jackson Turner, p. 10. 66. Mahan to Jameson, 21 July 1913: R. Seager and D. D. Macguire, Letters and Papers of Alfred Thayer Mahan, 3 vols., Annapolis

…

. 240 and 244. Turner lectured at the United States Naval War College, the home of Mahan’s sea power thesis from 1903. R. A. Billington, Frederick Jackson Turner: Historian, Scholar, Teacher, New York: Oxford University Press, 1973, p. 486. 67. Henry John Temple, Second Viscount Palmerston (1784–1865), served in government from 1805

…

: Reaktion Books, 2016. Billington, J. H. The Icon and the Axe: An Interpretative History of Russian Culture. New York: Random House, 1970. Billington, R. A. Frederick Jackson Turner: Historian, Scholar, Teacher. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973. Bindoff, S. T. The Scheldt Question to 1839. London: Allen and Unwin, 1945. Black, J., ed

…

. Falconer, A. F. Shakespeare and the Sea. London: Constable, 1964. Fantar, M. H. Carthage: The Punic City. Tunis: Alif, 1998. Faragher, J. M., ed. Rereading Frederick Jackson Turner. New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 1998. Fenlon, I. The Ceremonial City: History, Memory and Myth in Renaissance Venice. New Haven, CT, and

…

History. New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 1994. Turner, F. J. ‘The Significance of the Frontier in American History’, in Faragher, ed., Rereading Frederick Jackson Turner, pp. 30–60. Turner, F. M. The Greek Heritage in Victorian Britain. New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 1981. Unger, R. W. Dutch

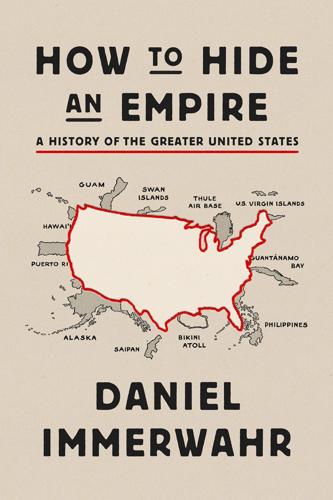

How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States

by Daniel Immerwahr · 19 Feb 2019

to an end,” mused a dejected Roosevelt in 1892. He wasn’t the only one to have that thought. A year later, the young historian Frederick Jackson Turner offered a similar reflection, stating it as a hypothesis, known today as the massively influential “frontier thesis.” The frontier, Turner argued, had been the great

…

arch-imperialist Cecil Rhodes. The global frontiers had been closed. * * * Roosevelt might have taken this as cause for despair. Yet just as he was reading Frederick Jackson Turner’s warnings about the end of the frontier, he was also studying the work of another historian, Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, of the Naval War

…

casual opinions. They formed a large part of the fifth volume of his History of the American People (1902). With its publication Wilson became, as Frederick Jackson Turner saw it, “the first southern scholar of adequate training and power who has dealt with American history as a whole.” Other reviewers shared Turner’s

…

”: WTR, 9:57. “bloody fighting”: WTR, 1:4. armed Sioux: WTR, vol. 1, chap. 7 of Ranch Life. “frontier proper”: WTR, 12:254. “frontier thesis”: Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” 1893, in The Frontier in American History (New York, 1920). “I think you have”: Edmund Morris, The

…

America,” Atlantic Monthly, December 1902, 731, 733. “white men of the South,” etc.: Wilson, History, 5:38, 5:49, 5:78. “the first southern scholar”: Frederick Jackson Turner, American Historical Review 8 (1903): 764. couldn’t help but notice: See reviews by Francis Wayland Shepardson, George McLean Harper, and C. H. Van Tyne

The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World

by Adrian Wooldridge · 2 Jun 2021 · 693pp · 169,849 words

faith in the great trilogy of equality, opportunity and mobility. It pioneered a wide-ranging set of reforms that updated these ideals for new times. Frederick Jackson Turner concluded his classic essay on the closing of the American frontier, which argued that the country’s great westward expansion had reached its limits, by

…

, 374 and press 334–5 support for 22, 342, 346 Trump, Ivanka 316, 319, 374 Turgot, Anne Robert Jacques 124 Turkey, imperial court 40 Turner, Frederick Jackson Turner 196 Turow, Scott 12 typewriters 271 tyranny, Plato on 64 UNCTAD 321 Unitarians 152 United Nations, declaration of human rights 26 United States 175–202

Appetite for America: Fred Harvey and the Business of Civilizing the Wild West--One Meal at a Time

by Stephen Fried · 23 Mar 2010 · 603pp · 186,210 words

, a relatively obscure academic paper was published in the Proceedings of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Prepared for the World Columbian Exhibition by historian Frederick Jackson Turner, the paper examined the role of the frontier in U.S. history. Turner boldly suggested that frontier spirit—and the drive farther and farther west

…

felt inextricably linked to and inspired by that “frontier spirit” of the Old West. It was a renewed version of the idealistic spark that historian Frederick Jackson Turner—whose work was still obscure, but was known to Roosevelt—wondered if the country might have lost forever. The war also seemed to trigger the

On the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World

by Timothy Cresswell · 21 May 2006

Beer-Can by the Highway (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1961); Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2000); Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1947). Crandall v. State of Nevada, 73 U.S. 35 (1867). Crandall v. State

…

Americans: The National Experience (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1966); James M. Jasper, Restless Nation: Starting Over in America (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2000); Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1947); Wilbur Zelinsky, The Cultural Geography of the United States (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice

The Idea of Decline in Western History

by Arthur Herman · 8 Jan 1997 · 717pp · 196,908 words

In 1893, the same year as the financial panic and the genesis of Brooks’s law of civilization and decay, a young American historian named Frederick Jackson Turner presented a paper to his fellow historians entitled “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” Turner argued that the “winning of the West” was

…

differentiating force” in American society, separating “those who bear the mark of foreign origin or inheritance from those who do not.”84 So even as Frederick Jackson Turner’s virtue-renewing frontier was closing forever, strange-sounding, strange-looking, and even strange-smelling “aliens” were arriving in ever greater numbers, concentrating in ever

…

his own Winchester, with its early morning calisthenics and endless drills in math and Latin verbs. * Toynbee’s source for these examples was, ironically enough, Frederick Jackson Turner. * Still, he was careful to move to Oxford during the Blitz and avoid visits to London. His wife outright accused him of cowardice, a charge

…

Rise and Fall of the Ku Klux Klan in Middle America . Archon Books, Hamden, CT, 1991. Turner, Frederick J. Frontier and Section: Selected Essays of Frederick Jackson Turner . Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1961. Turner, Henry M. Respect Black: Writings and Speeches of Henry McNeal Turner . Edited by E.S. Redkey . Arno Press

The State and the Stork: The Population Debate and Policy Making in US History

by Derek S. Hoff · 30 May 2012

, historians have long studied the influence of America’s unique demography—and anxieties about it—on the American fabric. Most famously, University of Wisconsin historian Frederick Jackson Turner argued in 1893 that the recent “closing” of the frontier threatened American democracy; recourse to the cheap lands in the lightly populated West had provided

…

would not be standing room on the surface of the earth for all the people.”3 Ely wrote the same year that his friend historian Frederick Jackson Turner proffered his famous “frontier thesis,” which posits that American democracy and the birth of the modern population debate 45 individualism were forged through the steady

…

, the Social Darwinists refitted Darwin to the social sphere and relied upon a crude form of Malthusianism to rail against government intervention.33 Well before Frederick Jackson Turner’s frontier thesis, for example, Sumner suggested that Americans enjoyed a high standard of living and freedom because they were relatively few. “Inferences as to

…

the “evils” stemming from industrialization and kept wages high (Richard T. Ely, Studies in the Evolution of Industrial Society [New York: Macmillan, 1903], 59). 4. Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History (New York: Henry Holt, 1920), 1. This volume is a compendium of Turner’s essays; Turner debuted “The Significance of

Stuck: How the Privileged and the Propertied Broke the Engine of American Opportunity

by Yoni Appelbaum · 17 Feb 2025 · 412pp · 115,534 words

for the inhabitants of all Europe,” Edward Everett said in 1852. And then, quite suddenly, it seemed as if there weren’t. * * * By the time Frederick Jackson Turner stood up to deliver the conference paper that changed the world, his audience was half-asleep. The mercury outside had neared ninety degrees on that

…

, A New Guide for Emigrants to the West (Boston: Gould, Kendall & Lincoln, 1836), 111. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT “All was motion and change”: Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History (New York: H. Holt, 1920), 354–55. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT “Westward the course of empire”: Elizabeth Kiszonas

…

Census of the United States: Population (Washington, D.C.: Census Office, 1901), 1: xxxiv. GO TO NOTE REFERENCE IN TEXT In a series of essays: Frederick Jackson Turner, “Studies of American Immigration,” Chicago Record-Herald, Sept. 25 and Oct. 16, 1901, quoted in Edward N. Saveth, American Historians and European Immigrants, 1875–1925

The Man Behind the Microchip: Robert Noyce and the Invention of Silicon Valley

by Leslie Berlin · 9 Jun 2005

tenth anniversary celebration: “Intel Celebrates,” San Jose Mercury News, 23 Aug. 1978. Birthplace of freedom: Such ideas can be traced to the writings of historian Frederick Jackson Turner. The “free lands” of the West, Turner wrote, served as a “gate of escape” and reinvigorated the country by promoting “individualism, economic equality, freedom to

…

rise, [and] democracy.” Frederick Jackson Turner, “Contributions of the West to American Democracy,” Atlantic Monthly, 91, Jan. 1903, 91. Broad and fertile plain: Noyce, “Competition and Cooperation—A Prescription for the

Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind

by Annalee Newitz · 3 Jun 2024 · 251pp · 68,713 words

After Tamerlane: The Global History of Empire Since 1405

by John Darwin · 5 Feb 2008 · 650pp · 203,191 words

The Forgotten Man

by Amity Shlaes · 25 Jun 2007 · 514pp · 153,092 words

Capitalism in America: A History

by Adrian Wooldridge and Alan Greenspan · 15 Oct 2018 · 585pp · 151,239 words

America's Bank: The Epic Struggle to Create the Federal Reserve

by Roger Lowenstein · 19 Oct 2015 · 589pp · 128,484 words

The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War (The Princeton Economic History of the Western World)

by Robert J. Gordon · 12 Jan 2016 · 1,104pp · 302,176 words

The Age of Illusions: How America Squandered Its Cold War Victory

by Andrew J. Bacevich · 7 Jan 2020 · 254pp · 68,133 words

The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again

by Robert D. Putnam · 12 Oct 2020 · 678pp · 160,676 words

Head, Hand, Heart: Why Intelligence Is Over-Rewarded, Manual Workers Matter, and Caregivers Deserve More Respect

by David Goodhart · 7 Sep 2020 · 463pp · 115,103 words

The Men Who United the States: America's Explorers, Inventors, Eccentrics and Mavericks, and the Creation of One Nation, Indivisible

by Simon Winchester · 14 Oct 2013 · 501pp · 145,097 words

The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class?and What We Can Do About It

by Richard Florida · 9 May 2016 · 356pp · 91,157 words

Drinking in America: Our Secret History

by Susan Cheever · 12 Oct 2015 · 263pp · 81,542 words

The Abandonment of the West

by Michael Kimmage · 21 Apr 2020 · 378pp · 121,495 words

Mapping Mars: Science, Imagination and the Birth of a World

by Oliver Morton · 15 Feb 2003 · 409pp · 129,423 words

Can Democracy Work?: A Short History of a Radical Idea, From Ancient Athens to Our World

by James Miller · 17 Sep 2018 · 370pp · 99,312 words

The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good?

by Michael J. Sandel · 9 Sep 2020 · 493pp · 98,982 words

The Meritocracy Myth

by Stephen J. McNamee · 17 Jul 2013 · 440pp · 108,137 words

America Right or Wrong: An Anatomy of American Nationalism

by Anatol Lieven · 3 May 2010

The New Class Conflict

by Joel Kotkin · 31 Aug 2014 · 362pp · 83,464 words

Democracy Incorporated

by Sheldon S. Wolin · 7 Apr 2008 · 637pp · 128,673 words

Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government

by Robert Higgs and Arthur A. Ekirch, Jr. · 15 Jan 1987

Utopias: A Brief History From Ancient Writings to Virtual Communities

by Howard P. Segal · 20 May 2012 · 299pp · 19,560 words

Dawn of Detroit

by Tiya Miles · 13 Sep 2017 · 415pp · 127,092 words

American Secession: The Looming Threat of a National Breakup

by F. H. Buckley · 14 Jan 2020

The Survival of the City: Human Flourishing in an Age of Isolation

by Edward Glaeser and David Cutler · 14 Sep 2021 · 735pp · 165,375 words

A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through?

by Kelly Weinersmith and Zach Weinersmith · 6 Nov 2023 · 490pp · 132,502 words

Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream

by Nicholas Lemann · 9 Sep 2019 · 354pp · 118,970 words

Behind the Berlin Wall: East Germany and the Frontiers of Power

by Patrick Major · 5 Nov 2009 · 669pp · 150,886 words

A Voyage Long and Strange: On the Trail of Vikings, Conquistadors, Lost Colonists, and Other Adventurers in Early America

by Tony Horwitz · 1 Jan 2008

The Making of Global Capitalism

by Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin · 8 Oct 2012 · 823pp · 206,070 words

Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis

by Robert D. Putnam · 10 Mar 2015 · 459pp · 123,220 words

This America: The Case for the Nation

by Jill Lepore · 27 May 2019 · 86pp · 26,489 words

The Last Ride of the Pony Express: My 2,000-Mile Horseback Journey Into the Old West

by Will Grant · 14 Oct 2023 · 246pp · 82,965 words

The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication From Ancient Times to the Internet

by David Kahn · 1 Feb 1963 · 1,799pp · 532,462 words

The Seventh Sense: Power, Fortune, and Survival in the Age of Networks

by Joshua Cooper Ramo · 16 May 2016 · 326pp · 103,170 words

Owning the Earth: The Transforming History of Land Ownership

by Andro Linklater · 12 Nov 2013 · 603pp · 182,826 words

The Complacent Class: The Self-Defeating Quest for the American Dream

by Tyler Cowen · 27 Feb 2017 · 287pp · 82,576 words

The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970

by John Darwin · 23 Sep 2009

Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire: A 500-Year History

by Kurt Andersen · 4 Sep 2017 · 522pp · 162,310 words

Case for Mars

by Robert Zubrin · 27 Jun 2011 · 437pp · 126,860 words

The Case for Space: How the Revolution in Spaceflight Opens Up a Future of Limitless Possibility

by Robert Zubrin · 30 Apr 2019 · 452pp · 126,310 words

Fantasyland

by Kurt Andersen · 5 Sep 2017

Why Nothing Works: Who Killed Progress--And How to Bring It Back

by Marc J Dunkelman · 17 Feb 2025 · 454pp · 134,799 words

When It All Burns: Fighting Fire in a Transformed World

by Jordan Thomas · 27 May 2025 · 347pp · 105,327 words

Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out?

by Bill McKibben · 15 Apr 2019

The Decadent Society: How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success

by Ross Douthat · 25 Feb 2020 · 324pp · 80,217 words

The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World (Hardback) - Common

by Alan Greenspan · 14 Jun 2007

Ashes to Ashes: America's Hundred-Year Cigarette War, the Public Health, and the Unabashed Triumph of Philip Morris

by Richard Kluger · 1 Jan 1996 · 1,157pp · 379,558 words

The Great Wave: The Era of Radical Disruption and the Rise of the Outsider

by Michiko Kakutani · 20 Feb 2024 · 262pp · 69,328 words

The Transhumanist Reader

by Max More and Natasha Vita-More · 4 Mar 2013 · 798pp · 240,182 words

Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism

by Harsha Walia · 9 Feb 2021

The Smartphone Society

by Nicole Aschoff

Servant Economy: Where America's Elite Is Sending the Middle Class

by Jeff Faux · 16 May 2012 · 364pp · 99,613 words

Living in a Material World: The Commodity Connection

by Kevin Morrison · 15 Jul 2008 · 311pp · 17,232 words

Why Liberalism Failed

by Patrick J. Deneen · 9 Jan 2018 · 215pp · 61,435 words

The Autonomous Revolution: Reclaiming the Future We’ve Sold to Machines

by William Davidow and Michael Malone · 18 Feb 2020 · 304pp · 80,143 words

More Everything Forever: AI Overlords, Space Empires, and Silicon Valley's Crusade to Control the Fate of Humanity

by Adam Becker · 14 Jun 2025 · 381pp · 119,533 words

Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business

by Neil Postman and Jeff Riggenbach Ph. · 1 Apr 2013 · 204pp · 61,491 words

Forever Free

by Joe Haldeman · 14 Oct 2000 · 230pp · 63,891 words

The Bonfire of the Vanities

by Tom Wolfe · 4 Mar 2008

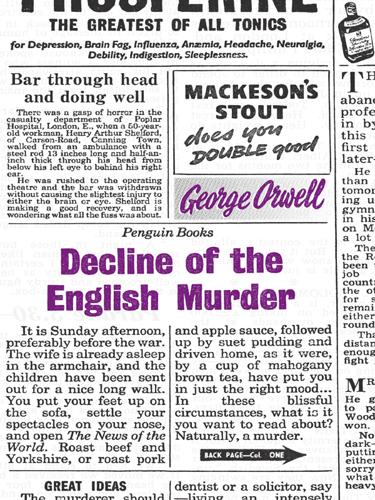

Decline of the English Murder

by George Orwell · 24 Jul 2009 · 96pp · 33,963 words