Geert Wilders

description: right-wing Dutch politician and leader of the Party for Freedom

58 results

Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism

by

Pippa Norris

and

Ronald Inglehart

Published 31 Dec 2018

‘Never a dull moment: Pim Fortuyn and the Dutch Parliamentary Election of 2002.’ West European Politics 26 (2): 41–66. Koen Vossen. 2016. The Power of Populism: Geert Wilders and the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands. New York: Routledge; Koen Vossen. 2011. ‘Classifying Wilders: The ideological development of Geert Wilders and his Party for Freedom.’ Politics 31 (3): 179–189. www.pvv.nl/36-fj-related/geert-wilders/9674-speech-geert-wilders-in-praag16-12-2017-menf-congres.html. Matthijs Rooduijn. 2014. ‘Vox populismus: A populist radical right attitude among the public?’ Nations and Nationalism 20 (1): 80–92.

…

Leaders typically stoke fears of Muslim-related terrorism in Western societies, heightening public anxieties following violent incidents and promising tough retaliation. This is the essence of the appeal presented by Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom, the Swiss People’s Party and the Danish People’s Party, the Austrian Freedom Party, the Norwegian Progress Party, and the Sweden Democrats. In the Netherlands, for example, Geert Wilders repeatedly warned in campaign speeches about the perils of Muslim immigrants, proposing to ban the Koran and shut mosques, arguing that only he could help the Dutch to ‘regain their own country.’

…

‘We mustn’t fool ourselves “Orbanian” discourse in the political battle over the refugee crisis and European identity.’ Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict 5 (2): 251–273. 29. Koen Vossen. 2016. The Power of Populism: Geert Wilders and the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands. New York: Routledge. See also www.geertwilders.nl/. 30. www.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/18/geert-wilders-netherlandsdescribes-immigrants-scum-holland. 31. Priscilla Southwell and Eric Lindgren. 2013. ‘The rise of neo-populist parties in Scandinavia: A Danish case study.’ Review of European Studies 5 (5): 128–135. 32. https://danskfolkeparti.dk/politik/stramninger-paa-udlaendingepolitikken/. 33.

The Populist Explosion: How the Great Recession Transformed American and European Politics

by

John B. Judis

Published 11 Sep 2016

In Switzerland, the Swiss People’s Party (SVP) came in first in the parliamentary elections with 29.4 percent of the vote, almost twice the total of the Social Democrats and the Liberals. In Norway, the Progress Party (FrP) has been part of the ruling government coalition since 2013. In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders’s Freedom Party (PVV), currently the country’s third largest party, is well ahead in polls for the 2017 parliamentary elections. Britain’s United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), after disappointing results in the 2015 parliamentary elections, bounced back in local elections, ousting the Labour Party in Wales and was at the forefront of the British campaign to exit the European Union.

…

Finland’s Finns Party wants “a democracy that rests on the consent of the people and does not emanate from elites or bureaucrats.” Spain’s Podemos champions the gente against the casta—the people against the establishment. Italy’s Beppe Grillo rails against what he calls the “three destroyers”—journalists, industrialists, and politicians. Geert Wilders’s Freedom Party represents “Henk and Ingrid” against “the political elite.” The first European parties were rightwing populist. They accused the elites of coddling communists, welfare recipients, or immigrants. As a result, the term “populist” in Europe became used pejoratively by leftwing and centrist politicians and academics.

…

Fortuyn was assassinated nine days before the election by a leftwing activist who objected to his attacks on Islam, but in the election, Fortuyn’s party still took 17 percent of the vote, making it the second largest in parliament. Without Fortuyn, the party eventually fell apart, but it was succeeded in 2006 by Geert Wilders’s highly successful Party for Freedom. Populists and the Welfare State As populist parties gained support for their stand against immigration, they widened their political base. The first populist parties, such as the National Front and the Freedom Party, had been petit-bourgeoisie parties. Their members were drawn primarily from small towns in the countryside, and were small business proprietors and small farmers—many of the same groups that had launched populism in the United States and spearheaded the rightwing in Europe between the world wars.

The Rise of the Outsiders: How Mainstream Politics Lost Its Way

by

Steve Richards

Published 14 Jun 2017

The US elects Donald Trump. Canada elects Justin Trudeau. Austria nearly elected a far-right president, but in the end chose a progressive member of the Green Party in the 2016 election. In March 2017 Holland’s centre-right prime minister, Mark Rutte, was re-elected, defeating the far right’s Geert Wilders by a relatively wide margin, and yet Wilders’ party made gains. The result in Holland, and the reaction to it, showed how electoral assumptions had changed. Although performing less well than Wilders had hoped, his Party for Freedom came second in terms of the number of seats won. Wilders had set the agenda for much of the campaign.

…

‘But I tell you, the stronger the pressure they put me under, the stronger I become.’1 The vulnerability helped to humanize him, an important part of the right-wing outsider’s allure: the tough leader who suffers, just as voters suffer. He was his party’s spokesman for the disabled. At the same time he was a gun enthusiast and carried a Glock pistol, conveying an enigmatic machismo. Geert Wilders, the founder of the Party for Freedom, is one of the more telegenic leaders in Holland, known mockingly – or admiringly – as the ‘blond bombshell’, although the colour of his luxurious hair is closer to grey. Frauke Petry, the chairwoman of the Alternative for Germany party, with a pixie haircut and a trim, athletic build is also telegenic.

…

UKIP’s Nigel Farage was a wealthy stockbroker from Surrey and a member of the European Parliament. The leading figure for the ‘Out’ campaign Boris Johnson was educated at Eton and Oxford, was a former editor of the weekly Spectator magazine and a former Mayor of London. The leader of the Dutch far-right party, Geert Wilders, has been a member of the Dutch parliament for years. Trump has been a famous multimillionaire entrepreneur and celebrity for decades. He is part of a rarefied privileged elite that has enjoyed fame and wealth on a scale that is unimaginable for most of ‘the people’. More to the point, he is transparently so, with his Trump Tower, his ostentatious flashy wealth and his ubiquity on TV.

How to Stop Brexit (And Make Britain Great Again)

by

Nick Clegg

Published 11 Oct 2017

Responding to what he called the wrong result, Arron Banks, the man who bankrolled the campaign to leave the EU, tweeted that the Austrian electorate ‘haven’t suffered enough rape and murder yet’.19 The Brexiteers then predicted that the Netherlands would topple next. ‘We may well be close, perhaps, to a Nexit,’ Nigel Farage confidently opined on the morning after the referendum.20 In March 2017, Mark Rutte – the leader of the liberal VVD party – comfortably defeated the right-wing populist Geert Wilders, who had been leading in the polls for the best part of two years. ‘This was an evening when … the Netherlands said “Stop” to the wrong sort of populism,’ Rutte declared. In neighbouring France, Marine Le Pen, leader of the far-right Front National, had predicted that 2017 would be the year in which ‘the peoples of Continental Europe wake up’.

…

The Legatum Institute – a think tank driven by a libertarian, low-regulation philosophy and amateur ideas about Britain’s future trade policy – has deep pockets linked to offshore finance, and is so well connected to the heart of Whitehall that it was invited, inexplicably, to join a cast of top corporate chief executives in a meeting with David Davis in his country residence, Chevening, in the summer of 2017.62 Dizzyingly wealthy individuals in the US have lent their financial clout to support libertarian US think tanks, in their promotion of small government, low tax and in some cases environmentally questionable policies – an ideological outlook that overlaps with anti-EU thinking across Europe. Through articles and public platforms, such bodies63 have played a part in supporting and promoting the likes of Nigel Farage, far-right French presidential candidate Marine Le Pen and her Dutch counterpart, Geert Wilders. Following Donald Trump’s election as US President, this ideology now echoes strongly on both sides of the Atlantic. When Trump became President, he employed Steve Bannon as his White House Chief Strategist (he has since departed). Bannon previously ran the alt-right media outlet Breitbart in Washington and helped to set up its London branch, where he appointed one Raheem Kassam (later a chief of staff to Farage, and briefly a candidate to succeed him as UKIP leader) to edit the site.

…

Any suggestion, as there no doubt would be, that Mr Rutte would relish giving Britain some form of Brexit punishment-beating would be totally inaccurate. He deeply regrets our decision to leave. He is one of the longest-serving Heads of Government of a founding EU member state, is widely respected across the continent and, in March 2017, secured a third term as Prime Minister after defeating a populist rival – the anti-Islam Geert Wilders – just as populism appeared to be on an unstoppable march. And if the Brexiteers needed further convincing, Rutte cites Winston Churchill as a role model and has described Margaret Thatcher as ‘an icon in English and European politics’ who ‘improved and strengthened’ Britain.90 Mark Rutte and Sir John Major, working in tandem, would make an experienced, formidable and, crucially, trusted partnership.

Why the Dutch Are Different: A Journey Into the Hidden Heart of the Netherlands: From Amsterdam to Zwarte Piet, the Acclaimed Guide to Travel in Holland

by

Ben Coates

Published 23 Sep 2015

The next day newspapers would report the speech on perhaps page seven, in a brief column summarising what was said, with little opinionising or speculation about its impact on his political future. People generally thought that politicians were decent and hard-working, and free from the taint of corruption or self-interest. In recent years there had been a slight trend towards a more combative style of politics, fuelled by the rise of populists such as Geert Wilders, but Dutch politics was still far from a blood sport. Watching anaemic debate programmes and reading pallid newspapers, I could never quite decide whether the Dutch determination to agree to disagree was a mark of civilised society, or just very tedious. Catholic Neighbours Short of time and weary of the rain, I decided I had already seen enough of Eindhoven’s carnival.

…

‘Nooooow,’ the man said, in the drawn-out way with which the Dutch would often exclaim, enlongating his vowels until the word sounded like a saw rasping through wood. ‘It’s true that there are some problems with the Moroccans, but he goes too far. Pim Fortuyn never hated people, he even slept with Muslims. But this one, he is much more nasty.’ ‘I think he’s just awful,’ his wife interjected. ‘More like a Nazi.’ Geert Wilders was born to a Catholic family in the far south of the Netherlands, the son of a man who reportedly was so traumatised by his wartime experiences that he refused ever to set foot on German soil. After studying law and living briefly in Israel, Wilders took a job as a speechwriter for Frits Bolkestein, the same politician who had controversially warned of the perils of Dutch multiculturalism and mentored Hirsi Ali.

…

Closer to home, a Muslim member of The Hague’s city council sparked a furore when he posted on Facebook, in Dutch, ‘Long live ISIS, and God willing on to Baghdad to clean up that scum’. A staffer at the Justice Ministry’s own Cyber Security Centre was fired after tweeting that ISIS was a Zionist plot to ‘blacken Islam’s name’. In 2014, Geert Wilders again managed to make himself the centre of attention, giving a speech in The Hague at which he asked a crowd of supporters: ‘In this city and in the Netherlands, do you want more or fewer Moroccans?’ ‘Minder! Minder!’ the crowd replied. ‘Fewer! Fewer!’ ‘Then we’ll make that happen,’ he replied.

Radicals Chasing Utopia: Inside the Rogue Movements Trying to Change the World

by

Jamie Bartlett

Published 12 Jun 2017

Dario Fo, Beppe Grillo and Gianroberto Casaleggio, Il Grillo canta sempre al tramonto (Chiarelettere Srl., 2013). 2. Paul Taggart, Populism (Open University Press, 2000). 3. For example, in the Netherlands, anti-Islam politician Geert Wilders (leading in the Dutch opinion polls at the time of writing) claims ‘citizens no longer feel represented by their national governments and parliaments’. Geert Wilders, ‘Let the Dutch vote on immigration policy’, New York Times, 19 November 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/20/opinion/geert-wilders-the-dutch-deserve-to-vote-on-immigration-policy.html. Capitalist Donald Trump wants to ‘declare independence from the elites’. Arch-socialist and Democrat candidate Bernie Sanders, thinks Americans are ‘sick and tired of establishment politics and economics’.

…

In our busy lives, we will pay attention to the one person making more noise than anyone else, we only have time to click on that funny thing at the top of our feeds, or the thing our friends—who think like us—have posted. It’s not the slow, informed and careful politicians who have thrived online; it’s the populists from across the spectrum. It’s the people with the simple, emotional, shareable messages. It’s people like Beppe. Dutch anti-Islam politician Geert Wilders, who’s compared the Qu’ran to Mein Kampf, is the most followed politician on the Dutch social networks. Bernie Sanders was propelled to within an inch of the Democratic Party nomination with help from his online #feelthebern fans and online donations. But the biggest shock of all (to pollsters and mainstream newspapers anyway) took place in 2016 when billionaire magnate, ur-populist, professional simplifier and Twitter addict Donald Trump was elected forty-fifth president of the United States.

…

* According to one unpublished doctorate thesis (submitted in late 2016), over the years of EDL demonstrations, between the EDL being founded and Tommy’s departure, there were a total of 1,551 arrests made, of which around 400 were counter-demonstrators. * Consider the names of many of the groups that share Pegida’s ideology. ‘For Frihed’ translates to ‘For Freedom’, as does Geert Wilders’ anti-Islam party, the PVV. The Swedish Democrats, the Danish People’s Party, even Pegida itself: they are names that progressive, moderate liberals would be proud of. * Nazis turned up at the first EDL demo, and although Tommy forced them to leave and even released a video burning a Swastika, they kept coming back.

Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration and the Future of White Majorities

by

Eric Kaufmann

Published 24 Oct 2018

In 2016, one poll found that nearly 40 per cent of married gay men backed the Front National.38 Thirty-six per cent of Front National voters in 2013 supported gay marriage compared to 25 per cent of voters for the centre-right UMP.39 The FN’s share of the Jewish vote reached 13.5 per cent in the 2014 European elections, more than double its previous level.40 Philo-Semitism was increasingly replacing anti-Semitism on the far right, something also evident in the pronouncements of the staunchly pro-Israel Geert Wilders in the Netherlands. While taking care not to offend social conservatives within the FN, Marine Le Pen’s opening to liberalism has helped the party detoxify its brand in a process known as ‘dédiabolisation’, making it more acceptable to voters uneasy about transgressing the anti-racist taboo against voting far right.

…

The studies that have been done on this – in Britain, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain – show that immigration, media coverage of immigration and salience rise together, as in figure 5.1.64 This means numbers really do matter, even if people’s perceptions of the actual inflows are inflated by a factor of two or three.65 SALIENCE AND POPULIST-RIGHT VOTING Figure 5.12, based on the work of James Dennison and Andrew Geddes, shows the relationship between immigration levels and support for Geert Wilders’ PVV in the Netherlands. As immigration totals exceeded 150,000 per year after 2013, the PVV’s projected seat total, based on opinion polls, rose dramatically. The authors find a significant correlation of .85 between annual immigration numbers and PVV support in the polls.66 Figure 5.12 shows there’s a trend but also considerable volatility in the PVV vote.

…

The parties become heavily reliant on the charisma of their leader – Farage, Wilders, Haider – and may suffer succession problems. The template for populist-right success seems to involve a viable populist-right party with a capable leader which can serve as a vehicle for protest when immigration increases. 5.12. Relationship between immigration levels and support for Geert Wilders’ PVV in the Netherlands Source: Dennison et al., ‘The Dutch aren’t turning against immigration’ The relationship between the migration crisis and the rise of the AfD in Germany is a case in point. During the crisis, Frauke Petry replaced Bernd Lucke, a founder of the party who was motivated by Eurosceptic economic concerns.

The Death of Truth: Notes on Falsehood in the Age of Trump

by

Michiko Kakutani

Published 17 Jul 2018

In the case of millennial-era America (and much of western Europe, too), these were grievances exacerbated by changing demographics and changing social mores that had made some members of the white working class feel increasingly marginalized; by growing income inequalities accelerated by the financial crisis of 2008; and by forces like globalization and technology that were stealing manufacturing jobs and injecting daily life with a new uncertainty and angst. Trump and nationalist, anti-immigrant leaders on the right in Europe like Marine Le Pen in France, Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, and Matteo Salvini in Italy would inflame these feelings of fear and anger and disenfranchisement, offering scapegoats instead of solutions; while liberals and conservatives, worried about the rise of nativism and the politics of prejudice, warned that democratic institutions were coming under growing threat.

…

“episodic waves”: Hofstadter, Paranoid Style in American Politics, 39. The anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant: Encyclopaedia Britannica, s.v. “Know-Nothing Party.” “America has been largely taken”: Hofstadter, Paranoid Style in American Politics, 39. nationalist, anti-immigrant leaders: Ishaan Tharoor, “Geert Wilders and the Mainstreaming of White Nationalism,” Washington Post, Mar. 14, 2017; Elisabeth Zerofsky, “Europe’s Populists Prepare for a Nationalist Spring,” New Yorker, Jan. 25, 2017; Jason Horowitz, “Italy’s Populists Turn Up the Heat as Anti-Migrant Anger Boils,” New York Times, Feb. 5, 2018. quoted, in news articles: Ed Ballard, “Terror, Brexit, and U.S.

Live Work Work Work Die: A Journey Into the Savage Heart of Silicon Valley

by

Corey Pein

Published 23 Apr 2018

Otto von Bolschwing “Silicon Valley Felt Touch of ex-Nazi Masquerader,” November 20, 1981, San Jose Mercury; Eric Lichtblau, The Nazis Next Door: How America Became a Safe Haven for Hitler’s Men (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014). “We are all the victims of Islamization” geertwilders.nl. his opponents in the Dutch Labor Party “PvdA-Kamerlid Jan Vos: ‘Geert Wilders Is Een Fascist’,” September 17, 2015, dagelijksestandaard.nl. “I am fed up with the Koran” Geert Wilders, “Enough Is Enough: Ban the Koran,” August 10, 2007, geertwilders.nl. “geeks for monarchy” was coined by Klint Finley, November 22, 2013, techcrunch.com. on the front page of the Wall Street Journal Erica Orden, “For BIL, Tagging Along with TED Proves to Be an Excellent Adventure,” March 1, 2011, wsj.com.

…

That is exactly what is happening in Europe right now … Our political leaders, your president Barack Obama, Britain’s prime minister David Cameron, German chancellor Angela Merkel, my own Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte, they still say that Islam is a religion of peace. Let me tell you: They are wrong! So, let us stop bowing to Islam! No appeasement anymore! The jihadis and their sympathizers do not belong in our societies. I say: Let us reclaim our freedom! The speaker was the leader of the far-right Dutch Party for Freedom, Geert Wilders, an aggrieved descendant of Indonesian colonizers and, by his own description, a freedom fighter assailed by threats from Islamic terrorists, with whom he equated the religion itself. Newsweek described him as “Islam’s arch-nemesis in Europe” and a potential future prime minister of the Netherlands.

Brexit, No Exit: Why in the End Britain Won't Leave Europe

by

Denis MacShane

Published 14 Jul 2017

When Mrs May met President Trump as the first European leader to go and pay homage to the new US president she was seen holding his hand. Now Trump’s best friend in Europe has been mortally wounded. As in Austria when the extreme nationalist candidate was defeated in presidential elections at the end of 2016, in the Netherlands where the anti-immigrant racist Geert Wilders failed in the March 2017 election and then in France where the anti-European Marine Le Pen was rejected in the May 2017 presidential election, Europe has emerged as the winner in the British election. Important new polling published in the general election for the Best of Britain campaign shows that 50 per cent of British people believe the UK should stay inside the Single Market, against 21 per cent who follow the UKIP–Tory–Labour manifesto acceptance that the UK has to quit the Single Market.

…

Anti-Europeanism politics is strong and has been so since the 1950s, fuelled by extremist ideologues of both left and right. Anti-Brexit commentators in London predicted and continue to predict a wave of Brexit-style wins for anti-EU nationalist populism across Europe. It did not happen. First in Austria, then in the Netherlands, then in France, such European fans of Brexit as Geert Wilders and Marine Le Pen failed to win support in national votes. That there is a rise in, as well as a solid base for, nationalist, xenophobic and anti-immigrant politics or anti-Brussels demagogy, including in governments in Poland and Hungary, is not in doubt. But if anything Brexit has been a warning to the rest of Europe that new leadership and a new reforming energy has to be found to avoid a Brexit-style Balkanisation of Europe.

…

The New Statesman, a left weekly, had given up reporting on Europe (other than articles written in impenetrable academic English) and clearly found the complexities of European politics either too difficult or too dull. The New Statesman could find seven pages to profile in gushing prose the anti-immigrant Dutch politician Geert Wilders as the coming man in Europe shortly before Wilders was soundly beaten in the Dutch election of March 2017, but the paper regularly over many years turned down articles that were positive about Europe and EU membership. To blame the inability of Jeremy Corbyn to make a pro-EU case for the Leave victory is ahistorical.

The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save It

by

Yascha Mounk

Published 15 Feb 2018

Switzerland, Petry said, has a wonderful political system, precisely because it trusts its citizens to make important decisions. It’s high time for Germany to do the same. Beyond Germany’s border, referenda have a newfound appeal for similar reasons. The UK Independence Party (UKIP), Podemos, Cinque Stelle, and other parties across Europe have all called for referenda. In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders presented his campaign promises for the 2017 parliamentary elections in an infamously hardline manifesto. The second of his eleven points was astoundingly simple (and thoroughly illiberal): ban the Koran. But the third point was ostensibly democratic: he sought to introduce binding referenda.69 It’s impossible to make sense of the rise of populism without facing up to the ways in which it claims the mantle of democracy.

…

Doubling down on his flirtation with the Third Reich, he saluted veterans of Adolf Hitler’s murderous Waffen SS by saying that “there are still decent people of good character who also stick to their convictions despite the greatest opposition.”24 Breaking political norms is also a specialty of Geert Wilders, the leader of the Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV). Islam, he has argued, is “a dangerous totalitarian ideology.”25 While other populists have sought to outlaw minarets or burkinis, Wilders, determined not to be outdone, has gone so far as to demand a ban on the Koran. By comparison to Haider and Wilders, a figure like Beppe Grillo seems far more benign at first blush.

…

Charlotte Beale, “German Police Should Shoot Refugees, Says Leader of AfD Party Frauke Petry,” Independent, January 31, 2016. 67. Some aspects of my description of Petry’s rally, as well as of the PEGIDA march described earlier in the chapter, are informed by Mounk, “Echt Deutsch.” 68. Author’s reporting. 69. “Preliminary Election Program PVV 2017–2021,” Geert Wilders Weblog, August 26, 2016, https://www.geertwilders.nl/94-english/2007-preliminary-election-program-pvv-2017-2021. 70. Angelique Chrisafis, “Jean-Marie Le Pen Fined Again for Dismissing Holocaust as ‘Detail,’” Guardian, April 6, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/06/jean-marie-le-pen-fined-again-dismissing-holocaust-detail. 71.

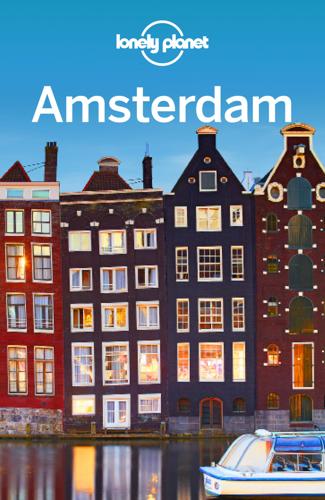

Lonely Planet Amsterdam

by

Lonely Planet

At the Royal Palace, Queen Beatrix stepped down after 33 years, abdicating in favour of her eldest son Willem-Alexander, who became king on 30 April 2013. His investiture took place in the Nieuwe Kerk. He is the first male to accede to the Dutch throne since 1890. In the 2017 Dutch general election, Mark Rutte's VVD party defeated controversial far-right politician Geert Wilders' Party for Freedom (PVV), gaining 33 seats to the PVV's 20. Had the PVV garnered a majority of seats, Wilders would have been unlikely to govern, given no potential coalition parties expressed willingness to work with him in light of his extreme views (such as comparing the Quran to Mein Kampf) and policies (including his advocation for a 'Nexit' from the EU, and hardline anti-immigration stance).

…

The ruling Dutch parties shift to the right after suffering major losses in the national election. 2004 Activist filmmaker Theo van Gogh, a fierce critic of Islam, is murdered, touching off intense debate over the limits of Dutch multicultural society. 2008 The city announces Project 1012. The goal is to clean up the Red Light District and close prostitution windows and coffeeshops believed to be controlled by organised crime. 2009 Amsterdam courts prosecute Dutch parliamentary leader Geert Wilders for 'incitement to hatred and discrimination'. (He is acquitted of all charges in 2011.) 2010 Members of the Dutch government officially apologise to the Jewish community for failing to protect the Jewish population from genocide. 2013 After a 33-year reign, Queen Beatrix abdicates in favour of her eldest son, Willem-Alexander, who becomes the Netherlands' first king in 123 years. 2015 Scores of prostitutes and their supporters take to the streets to protest the closure of roughly one-fifth of the Red Light District's windows. 2017 Prime Minister Mark Rutte's People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) defeats Geert Wilders' Party for Freedom (PVV) in the Dutch general election.

…

(He is acquitted of all charges in 2011.) 2010 Members of the Dutch government officially apologise to the Jewish community for failing to protect the Jewish population from genocide. 2013 After a 33-year reign, Queen Beatrix abdicates in favour of her eldest son, Willem-Alexander, who becomes the Netherlands' first king in 123 years. 2015 Scores of prostitutes and their supporters take to the streets to protest the closure of roughly one-fifth of the Red Light District's windows. 2017 Prime Minister Mark Rutte's People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) defeats Geert Wilders' Party for Freedom (PVV) in the Dutch general election. Dutch Painting They don't call them the Dutch Masters for nothing. The line-up includes Rembrandt, Frans Hals and Jan Vermeer – these iconic artists are some of the world's most revered and celebrated painters. And then, of course, there's Vincent van Gogh, who toiled in ignominy while supported by his loving brother Theo, and 20th-century artists including De Stijl–proponent Piet Mondrian and graphic genius MC Escher.

Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World

by

Timothy Garton Ash

Published 23 May 2016

Wingrove v UK (1997) 24 EHRR 1; see Barendt 2007, 192 55. on the Wilders case, see Rutger Kaput’s case study: Rutger Kaput, ‘Geert Wilders on Trial’, Free Speech Debate, http://freespeechdebate.com/en/case/geert-wilders-on-trial/, and his Dahrendorf essay, http://perma.cc/R2XM-NUBW. See also Timothy Garton Ash, ‘Intimidation and Censorship Are No Answer to This Inflammatory Film’, The Guardian, 9 April 2008, http://perma.cc/HP82-M2CH, and Timothy Garton Ash, ‘To Fight the Xenophobic Populists, We Need More Free Speech, Not Less’, The Guardian, 12 May 2011, http://perma.cc/FK9G-QCEC 56. Statement to the court, 7 February 2011, ‘Geert Wilders: The Lights Are Going Out All Over Europe (english subs)’, 8 February 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?

…

In subsequent cases, the court tilted towards more protection of free expression, but Europeans have been left with no clear guidelines—in relation not merely to believers but also to beliefs. One reason is precisely that, although the distinction I have drawn between the two kinds of respect is important, it is fiendishly difficult to apply with the instruments of secular law. Another difficulty is illustrated by the prosecution in the Netherlands of the politician Geert Wilders. Wilders had made a successful political career for himself and his Freedom Party, winning nearly a sixth of the seats in parliament in the 2010 elections on the back of extreme and undoubtedly offensive criticism of the scale and character of Muslim immigration to the Netherlands, and of Islam itself.

Against the Web: A Cosmopolitan Answer to the New Right

by

Michael Brooks

Published 23 Apr 2020

Sorry, Chuck Hagel, the former Republican Senator from Nebraska who was an occasional voice of restraint against interventionism in the Bush era (although he did initially vote to invade Iraq in 2003) and who was nominated by Obama to be Secretary of Defense. That Chuck Hagel was indeed not an associate of Hamas. Shocker. A column entitled “Enemy ‘Civilian Casualties’ OK By Me.” Enough said. In 2017, Republican Congressman Steve King tweeted about the birth rates of Muslim immigrants to Europe. Praising Dutch fascist Geert Wilders, King tweeted, “Wilders understands that culture and demographics are our destiny. We can’t restore our civilization with somebody else’s babies.” Even though it’s a pretty good bet that someone with King’s worldview would also put Shapiro’s family in the “somebody else” category, at the time Shapiro contorted himself into a rhetorical pretzel trying to find a non-racist way to interpret King’s comments.

Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks From the Stone Age to AI

by

Yuval Noah Harari

Published 9 Sep 2024

Trump, “Remarks by President Trump to the 74th Session of the United Nations General Assembly,” Sept. 24, 2019, trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-74th-session-united-nations-general-assembly/; Jair Bolsonaro, “Speech by Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro at the Opening of the 74th United Nations General Assembly—New York,” Ministério das Relações Exteriores, Sept. 24, 2019, www.gov.br/mre/en/content-centers/speeches-articles-and-interviews/president-of-the-federative-republic-of-brazil/speeches/speech-by-brazil-s-president-jair-bolsonaro-at-the-opening-of-the-74th-united-nations-general-assembly-new-york-september-24-2019-photo-alan-santos-pr; Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister, “Speech by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán at the Opening of CPAC Texas,” Aug. 4, 2022, 2015-2022.miniszterelnok.hu/speech-by-prime-minister-viktor-orban-at-the-opening-of-cpac-texas/; Geert Wilders, “Speech by Geert Wilders at the ‘Europe of Nations and Freedom’ Conference,” Gatestone Institute, Jan. 22, 2017, www.gatestoneinstitute.org/9812/geert-wilders-koblenz-enf. 42. Marine Le Pen, “Discours de Marine Le Pen, (Front National), après le 2e tour des Régionales,” Hénin-Beaumont, Dec. 6, 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dv7Us46gL8c. 43. Trump White House, “President Trump: ‘We Have Rejected Globalism and Embraced Patriotism,’ ” Aug. 7, 2020, trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/articles/president-trump-we-have-rejected-globalism-and-embraced-patriotism/. 44.

The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics

by

David Goodhart

Published 7 Jan 2017

When Fortuyn was assassinated two days before the election by an unhinged vegan activist his death swept away any remaining taboos about opposing immigration and multiculturalism in the Netherlands. A series of governments, of both centre-left and centre-right, have subsequently implemented more overtly integrationist policies—pushed hard from the outside (and briefly from the inside) by Geert Wilders and his anti-immigration, anti-Islam Party of Freedom (PVV). The Wilders party, which emerged in the 2006 election, has consistently claimed between 10 and 20 per cent of the popular vote ever since, which in the Netherlands’ fragmented political system usually makes it the second or third largest party in popular support.

…

Support for the Dutch Labour party, for example, has fallen from nearly 30 per cent to less than 10 per cent in recent years as educated people in big cities and university towns have peeled off to the Greens and a liberal party called D66 (between them they now get the votes of 80 per cent of Dutch students), while working class strongholds in places like Rotterdam have switched to the Geert Wilders Party of Freedom. The Anywhere/Somewhere value divide has been only one part of the story of social democratic decline. Others include the achievement of many historic social democratic goals; de-industrialisation and the shrinking of the traditional, unionised working class; and the more mainstream legitimacy of populist parties.

No Is Not Enough: Resisting Trump’s Shock Politics and Winning the World We Need

by

Naomi Klein

Published 12 Jun 2017

Most encouragingly, while the early assumption was that Trump’s rise could set off a wave of far-right electoral victories, in some countries it seems to be having the opposite effect. Witnessing Trump’s ugly administration in action, some electorates are deciding to stop the tide. Ahead of elections in the Netherlands in March 2017, many predicted a win for Geert Wilders and his profoundly anti-Islamic and xenophobic Freedom Party. Instead, Wilders’s support suddenly collapsed and the governing party held on to the most seats. But the biggest winner in the election was the GreenLeft party, which went from holding four seats to capturing fourteen. The party’s leader, Jesse Klaver, is of Moroccan and Indonesian descent and campaigned with a bold antiracist message.

…

Then Came ‘Month 13.’ ” New York Times, March 25, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/25/world/canada/syrian-refugees.html. Jesse Klaver: “Don’t try to fake the populace. Stand for your principles…” Peter Foster and Senay Boztas, “Dutch Elections: Prime Minister Mark Rutte Calls for a ‘Stand against Geert Wilders’ Populism’ as Netherlands Goes to the Polls,” Associated Press via Daily Telegraph (London), March 15, 2017, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/03/15/dutch-prime-minister-calls-stand-against-populism-netherlands/. Jean-Luc Mélenchon support and results Ingrid Melander and Marine Pennetier, “French Left Must Agree a Candidate for Presidential Election—Hollande’s Party Chief,” Reuters.com, February 18, 2016, http://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-france-politics-hollande-idUKKCN0VR1QN.

After Europe

by

Ivan Krastev

Published 7 May 2017

The shock inspired by these twin events sends us a message that we do not understand the world as well as we thought we did. In 2017, we therefore face a very different dynamic. We are not only aware that the unthinkable can happen, but we actually expect it to happen. We fear but also expect that Geert Wilders will be the big winner of the Dutch elections, that Marine Le Pen will end up as the new president of France (which would probably spell the end of the EU), and that Merkel’s moment in German politics has come to an end. All this really may happen, but most likely it will not. Wilders already has lost an election in the Netherland.

The Brussels Effect: How the European Union Rules the World

by

Anu Bradford

Published 14 Sep 2020

July 6, 2006). 228.Id. 229.European Court of Human Rights, Fact sheet on Hate Speech, 1 (Mar. 2019), https://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/FS_Hate_speech_ENG.pdf [https://perma.cc/FHY6-HDWV]. 230.Council Framework Decision, supra note 217. 231.Directive 2010/13/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 March 2010 on the coordination of certain provisions laid down by law, regulation or administrative action in Member States concerning the provision of audiovisual media services (Audiovisual Media Services Directive), 2010 O.J. (L 95) 1. 232.Art. 137(c) & Art. 137(d), para. 1, Sr.(Neth.). 233.See, e.g., Sheena McKenzie, Geert Wilders guilty of ‘insulting a group’ after hate speech trial, CNN (Dec. 9, 2016), https://www.cnn.com/2016/12/09/europe/geert-wilders-hate-speech-trial-verdict/index.html [https://perma.cc/QXQ3-KUQA]. 234.See, e.g., European Commission, Code of Conduct on countering illegal hate speech online: First results on implementation (Dec. 2016), https://ec.europa.eu/information_society/newsroom/image/document/2016-50/factsheet-code-conduct-8_40573.pdf [https://perma.cc/CM67-8Z2H]. 235.Jeffrey Eisenach, Don’t Make the Internet a Public Utility, N.Y.

…

The Dutch code also prohibits “engaging in verbal, written, or illustrated incitement to hatred, on account of one’s race, religion, sexual orientation, or personal convictions.”232 Most prominently, the Netherlands has applied its rules on hate speech in the case involving its right-wing politician, Geert Wilders, who has targeted Muslims and Islam in much of his political rhetoric.233 This shows that even among the European nations most sympathetic to defending free speech, hate speech is relatively broadly defined and strictly enforced. Not only is the EU more willing to curtail hate speech as a phenomenon, it is also more willing to generally regulate digital companies.234 It is therefore not surprising that the EU has evolved into a prominent regulator of hate speech taking place online, holding the IT companies responsible for the speech that takes place on their platforms.

The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam

by

Douglas Murray

Published 3 May 2017

In the aftermath of the murder the Netherlands went into mourning, and in the ensuing election voters gave Fortuyn’s party the largest number of seats, a gift it repaid by petty infighting and a total inability (perhaps inevitable given the swiftness of their rise) to deliver on its mandate. The Dutch public’s desire to deal with their challenges at the ballot box were thwarted. And although those who picked up his political mantle included Geert Wilders (who left the main VVD ‘liberal’ party also to form a party of his own), none of Fortuyn’s successors were able to pick up the working-class and young entrepreneurial vote that Fortuyn had been able to appeal to. Although the murder of the man who would later be voted the greatest Dutchman of all time shuttered one part of electoral politics, it did, however, allow the debate to widen in the society as a whole.

…

Nonetheless, while it may also be noted that no similar ‘anti-communist’ fervour was ever sustained in Western Europe, or was dismissed where it was suspected as akin to ‘witch-hunting’, anti-fascists in Europe were not always onto nothing – a fact that applies yet another layer of complexity onto Europe’s social problems. In the United States a popular protest movement of any kind, including one to do with immigration or Islam, is likely to attract some eccentric or even crazy people with kooky signs. But it will rarely consist early on, let alone firstly, of actual Nazis. When the Dutch MP Geert Wilders split off from the Dutch Liberal Party (VVD) in 2004 over the VVD’s support of Turkey’s entry into the EU, he formed his own party. The Party for Freedom (PVV) gained nine out of 150 seats in the Dutch Parliament at its first election in 2006. Opinion polls in 2016 showed the party to be the most popular party in Holland.

Brexit: What the Hell Happens Now?: The Facts About Britain's Bitter Divorce From Europe 2016

by

Ian Dunt

Published 11 Apr 2017

But the parties which are capitalising on this identity crisis are the same ones demanding exit from the EU. So the incentives from the French political class are to address concerns on the one hand while simultaneously showing that leaving the EU does not work. Even in liberal Holland there are problems, with far-right leader Geert Wilders demanding a referendum on EU membership following the British result. The Dutch have elections in 2018 and the incentives for the mainstream political class will be identical to those in Germany and France: to show Brexit doesn’t work. That partly explains the uniform wall of hostility on the Continent which Britain has met since the vote.

God Is Back: How the Global Revival of Faith Is Changing the World

by

John Micklethwait

and

Adrian Wooldridge

Published 31 Mar 2009

No Muslim Gorbachev has yet emerged, but there have been a few Voltaires. Afshin Ellian, an Iranian-born scholar, argues that Islam needs its own versions of Nietzsche, Voltaire and Marquis de Sade. Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who wrote the script for Submission, has described Muhammad as a “perverted tyrant” and cowrote an article with Geert Wilders calling for a “liberal jihad.” THREE BATTLEGROUNDS These, then, are the warriors in Europe’s new culture wars. At their core, these battles pit an increasingly aggressive Muslim minority against liberal secularists. Both sides have their villains, hangers-on and rent-a-mobs. And the battleground ranges far and wide—from religious freedom to food, from clothing to arranged marriages.

…

Two centuries after the princes of the Enlightenment excoriated “I’infame” for trying to repress open debate, Europe has witnessed a succession of attempts by Muslims to censor offensive speech. The opening shot was the fatwa against Salman Rushdie for insulting the Prophet in The Satanic Verses (1988). Rushdie survived his death sentence. Theo van Gogh was less fortunate: he was slaughtered for insulting the Prophet in 2004. Hirsi Ali was eventually hounded out of the Netherlands. Geert Wilders still receives death threats: “It is our wish to kill you by decapitation. Your infidel blood will flow freely on cursed Dutch streets.” The publication of cartoons of Muhammad in Flemming Rose’s newspaper ignited another mass assault on free speech. Muslims across the world called for a “holy war” against Europe.

The Lonely Century: How Isolation Imperils Our Future

by

Noreena Hertz

Published 13 May 2020

Its grip on the imaginations, emotions and voting intentions of a considerable proportion of citizens is likely to endure. Of additional concern is that divisive, race-tinged rhetoric is often contagious in its own right. In an incendiary attempt to fend off a challenge from right-wing populist candidate Geert Wilders, the non-populist, centre-right prime minister of the Netherlands Mark Rutte ran a newspaper ad in 2017 that instructed immigrants to ‘Be Normal, or Be Gone’.79 Denmark’s Centre Left Social Democrats were victorious in Denmark’s 2019 election with a manifesto that was disturbingly redolent of the far right when it came to issues of immigration.80 Indeed, in many ways the greatest danger associated with the rise in populism in recent years is how it has pushed traditional parties of both the right and left ever further to the extremes and normalised a discourse of divisiveness, distrust and hate.

…

Social Europe, 28 May 2019, https://www.socialeurope.eu/what-drives-anti-migrant-attitudes. 78 Ibid., and for the US see also Sean McElwee, ‘Anti-Immigrant Sentiment Is Most Extreme in States Without Immigrants’, Data for Progress, 5 April 2018, https://www.dataforprogress.org/blog/2018/4/5/anti-immigrant-sentiment-is-most-extreme-in-states-without-immigrants. 79 Senay Boztas, ‘Dutch prime minister warns migrants to “be normal or be gone”, as he fends off populist Geert Wilders in bitter election fight’, Telegraph, 23 January 2017, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/01/23/dutch-prime-minister-warns-migrants-normal-gone-fends-populist/. 80 Jon Henley, ‘Centre-left Social Democrats victorious in Denmark elections’, Guardian, 5 June 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/05/centre-left-social-democrats-set-to-win-in-denmark-elections; idem., ‘Denmark’s centre-left set to win election with anti-immigration shift’, 4 June 2019, Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/04/denmark-centre-left-predicted-win-election-social-democrats-anti-immigration-policies. 81 Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (Harcourt, 1951), p.356. 82 E.

The People vs Tech: How the Internet Is Killing Democracy (And How We Save It)

by

Jamie Bartlett

Published 4 Apr 2018

The latest iteration, and the first bona fide politician of the social media age, is Twitter addict and world-class simplifier Donald Trump. He is the leading act in a new cast of populists who have found the internet a revelation for their style of politics, including Nigel Farage, Bernie Sanders, Dutch anti-Islam firebrand Geert Wilders, Italian comedian and Five Star Movement founder Beppe Grillo and others. Some of them are left wing, some are right wing, but all are ‘system one’ leaders who became popular by promising easy solutions to complicated questions. Trump is the strong man, the tribal leader who trades on outrage.

Where We Are: The State of Britain Now

by

Roger Scruton

Published 16 Nov 2017

What is needed, not in Britain only but throughout the Western democracies, is a serious attempt to achieve the kind of extended patriotism that will include as many as possible of those who are tempted in this way by the path of non-belonging. This cannot be achieved through politics alone, since it concerns the first-person plural on which politics depends. It is a cultural, and not a political task, and those who try to achieve it by political means – such as Marine Le Pen in France and Geert Wilders in the Netherlands – risk alienating the very people whom they wish to recruit, the ones who feel most isolated in the home that should be theirs, and whose sentiments are more likely to express themselves in angry rejection than peaceful accommodation towards their neighbours. Social affections cannot be imposed by politics; but they can be influenced through discussion and example, through works of art and popular culture, through a concerted effort on the part of the patriots to give a genial and humane voice to their worldview – one that will include their critics in the work of nation-building.

European Spring: Why Our Economies and Politics Are in a Mess - and How to Put Them Right

by

Philippe Legrain

Published 22 Apr 2014

In Britain, the anti-immigrant and anti-EU United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) did surprisingly well in the 2013 local elections and may come first in the May 2014 European ones. In France, Marine Le Pen’s fascist National Front (FN) polled nearly a fifth of the vote in 2012 and now tops the polls. In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders’ anti-immigrant Freedom Party (PVV) is ahead in the polls again. Timo Soini’s eurosceptic True Finns – now rebadged The Finns in case anyone doubted their Finnishness – are the largest opposition party. Belgium’s biggest party is hardline Flemish nationalist Bart de Wever’s New Flemish Alliance (N-VA); a smaller nationalist party, Vlaams Belang, is even more extreme.

…

It will simply happen elsewhere. That will strengthen the voices of those who propose extremist and often noxious solutions, while frustrating those who want a reasonable voice in the EU debate but have nowhere to turn. The biggest beneficiaries of the status quo are the likes of Marine Le Pen, Geert Wilders and Nigel Farage. Ultimately, just as elites in the nineteenth century and the twentieth century agreed to open up politics and broaden the democratic franchise under popular pressure, so all Europeans who want the EU to succeed must demand to shape its future. If Europeans are told that there is no alternative to current policies or the existing system, many will reject it altogether.

When They Go Low, We Go High: Speeches That Shape the World – and Why We Need Them

by

Philip Collins

Published 4 Oct 2017

In France, Marine Le Pen and her nativist Front National denounce a political establishment that she blames for betraying the white people of France. Similar tunes are played by the Danish People’s Party, the Swedish Democrats, the People’s Party of Switzerland and the notoriously Islamophobic Geert Wilders in Holland. In Poland, the Law and Justice Party stands accused of trampling on the country’s constitution to establish an ‘illiberal democracy’ of its own. But the most conspicuous setback for democracy has taken place in Russia. When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989 there were high hopes for a democratic order in the old Soviet Union, but these hopes faded in 1999 when Vladimir Putin replaced Boris Yeltsin.

…

The words of Jefferson, Lincoln, Kennedy and Obama are all designed to bind a nation together. Populist politics, by contrast, needs to construct internal enemies as detached from the people. President Trump has proposed the deportation of undocumented immigrants and wants a wall to keep out the Mexicans. In Holland Geert Wilders wants to repeal hate-speech legislation. In Poland, Jarosław Kaczyński sought to make the use of the term ‘Polish death camps’ illegal. As the incarnation of truth, the populist is a stranger to the doubts and humility that find expression in the speeches in this chapter. His utopia has none of the pluralism of a liberal democracy.

The Retreat of Western Liberalism

by

Edward Luce

Published 20 Apr 2017

UKIP’s stark claim – or, more accurately, its outright lie – that Britain’s exit from Europe would free up £350 million a week for NHS spending (‘a new hospital every week’) may have proved critical in tipping the referendum. In continental Europe, the more generous the welfare system, the more bitter the reaction against immigrants. The Danish People’s Party now takes more than a quarter of that country’s once reliably social democratic working-class vote. In Holland Geert Wilders’s Party for Freedom takes an even higher share. (Much as people prematurely celebrated the Austrian Freedom Party candidate’s defeat in December as a blow against populism, Wilders’s Party for Freedom’s poor second-place showing in Holland in March came with a sting. The whole political spectrum had shifted towards Wilders’s Islamophobic agenda.)

What About Me?: The Struggle for Identity in a Market-Based Society

by

Paul Verhaeghe

Published 26 Mar 2014

Such classifications are almost always linked to external characteristics (such as skin colour, physique, and clothing), which can then be deployed in a naïve debate on integration, culminating in proposals to ban headscarves (or in imposing a ‘head-rag tax’, as suggested by the populist Dutch politician Geert Wilders). Conversely, if the differences aren’t sufficiently visible, we fix that (by demanding the wearing of a Star of David, or the bearing of passports stating the holder’s race). The importance we attach to these external characteristics is a measure of our own uncertainty: remove them, and the distinctions become practically invisible.

Survival of the Friendliest: Understanding Our Origins and Rediscovering Our Common Humanity

by

Brian Hare

and

Vanessa Woods

Published 13 Jul 2020

Frauke Petry’s Alternative for Germany, who suggested shooting asylum seekers as they crossed the border and banning Islamic symbols, is the country’s third most powerful political party. Pegida, the German anti-Islamic party, is gaining the kind of support reminiscent of a Trump rally, where journalists need security guards. Geert Wilders, who was charged with inciting violence against Muslims, currently heads the most popular party in the Netherlands. If the election had been held in 2016, he would have won more seats in the government than any other party. The party has called to close Islamic schools and record the ethnicity of Dutch citizens.

Unhappy Union: How the Euro Crisis - and Europe - Can Be Fixed

by

John Peet

,

Anton La Guardia

and

The Economist

Published 15 Feb 2014

The rise of populists and extremists is not confined to troubled euro-zone countries alone. In Finland, the True Finns (now the Finns Party) under Timo Soini, which came out of nowhere in 2011, largely to protest against the euro, are scoring 20% or more in most opinion polls. In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders’ Party of Freedom is also riding high. Wilders has formed an alliance with Le Pen for the European elections, campaigning on an anti-EU, anti-euro platform. The UK Independence Party has refused to join this alliance, but it too has been scoring highly in the polls. Across central and eastern Europe a swathe of extremist and populist parties, from Jobbik in Hungary to the League of Catholic Families in Poland, are similarly doing well.

The Last President of Europe: Emmanuel Macron's Race to Revive France and Save the World

by

William Drozdiak

Published 27 Apr 2020

One by one, xenophobic politicians railed against Emmanuel Macron for defending open borders and the idea of a European superstate. Under Salvini’s orchestration, they endorsed his pan-European coalition behind the slogan “Towards a Common Sense Europe: Peoples Rise Up.” Anti-EU nationalists such as Marine Le Pen of France and Geert Wilders of the Netherlands took turns shrilly denouncing the surrender of national sovereignty to faceless and feckless bureaucrats in Brussels. As Salvini stepped forward to speak, the vast Piazza del Duomo resonated with chants of “Matteo! Matteo!” and “Il Capitano!” He vowed to transform the European Union and restore greater control to national capitals by liberating the continent from “the illegal occupation organized by Brussels.”

Building the Cycling City: The Dutch Blueprint for Urban Vitality

by

Melissa Bruntlett

and

Chris Bruntlett

Published 27 Aug 2018

But the Dutch don’t cycle because their country is flat (if it were that simple, then Chicago and Winnipeg would be the biking capitals of North America). The Dutch don’t cycle because the weather is nice (and anyone caught in a brutal wind-or snowstorm blowing off the North Sea will refute that idea). The Dutch don’t cycle because they’re morally superior to the rest of the globe (their electoral flirtations with far-right candidate Geert Wilders should put that myth to bed). No, the Dutch cycle because they’ve built a dense, 35,000-kilometer (22,000-mile) network of fully separated bike infrastructure, equal to a quarter of their 140,000-kilometer (87,000-mile) road network. The Dutch cycle because they’ve tamed the motor vehicle, with over 75 percent of their urban streets traffic-calmed to a speed of 30 km/h (about 19 mph) or less.

Devil's Bargain: Steve Bannon, Donald Trump, and the Storming of the Presidency

by

Joshua Green

Published 17 Jul 2017

Bannon’s response to the rise of modernity was to set populist, right-wing nationalism against it. Wherever he could, he aligned himself with politicians and causes committed to tearing down its globalist edifice: archconservative Catholics such as Burke, Nigel Farage and UKIP, Marine Le Pen’s National Front, Geert Wilders and the Party for Freedom, and Sarah Palin and the Tea Party. (When he got to the White House, he would also leverage U.S. trade policy to strengthen opponents of the EU.) This had a meaningful effect, even before Trump. “Bannon’s a political entrepreneur and a remarkable bloke,” Farage said. “Without the supportive voice of Breitbart London, I’m not sure we would have had a Brexit.”

The Globotics Upheaval: Globalisation, Robotics and the Future of Work

by

Richard Baldwin

Published 10 Jan 2019

Overall, these far-right populist parties saw their share rise from under 20 percent to over 30 percent between the 2009 and 2014 elections. At the national level, a worryingly far-right candidate, Marine Le Pen, looked set to win the French presidency, and poll-numbers of populists in several other nations surged. In the end, the French strongly rejected the French version of Trump. Dutch populist Geert Wilders’s party, the Party for Freedom, did well but didn’t win. The antimigrant, populist upstart party, Alternative for Germany, did well enough to get 13 percent of parliamentary seats, but it didn’t enter into power. In Austria, the far-right Freedom Party entered into a power-sharing arrangement in 2017 and is thus part of the government.

Reaching for Utopia: Making Sense of an Age of Upheaval

by

Jason Cowley

Published 15 Nov 2018

We are not witnessing the return of a more liberal, optimistic Europe. Marine Le Pen won thirty-four per cent of the vote in the second round of the French presidential election against Emmanuel Macron, after reverting in the final weeks of the campaign to the politics of her father, an old-style Vichy fascist. To defeat Geert Wilders’s anti-Muslim Freedom Party in the Netherlands, the centre-right Dutch prime minister, Mark Rutte, had to adopt some of his rival’s positions and borrow much of his xenophobic rhetoric. In the illiberal democracies of eastern Europe – Poland, Hungary – an ugly form of the old right has re-emerged.

There's a War Going on but No One Can See It

by

Huib Modderkolk

Published 1 Sep 2021

Years of frustration, in which I’d be making progress one day only to have sources go silent or refuse to meet the next. And of incomprehension, because very few people really grasp how agencies work and why they’re so secretive. Even my colleagues. I remember one conversation I had with de Volkskrant editor Philippe Remarque when at long last I’d managed to secure confirmation that Dutch far-right politician Geert Wilders was under investigation by the AIVD. It turned out they’d been running an inquiry on his ties within the Israeli Embassy. Elated, I went to share my findings with Remarque. ‘OK,’ he cautiously replied, ‘so what did the investigation turn up?’ ‘I’d love to know, but my sources won’t say.’ ‘Can we take a look at the report?’

Who Are We—And Should It Matter in the 21st Century?

by

Gary Younge

Published 27 Jun 2011

But when Muslims do bad things, it is never about individuals, their flaws, national customs, societal pressure or political and economic context. It is about Islam. It is as if Latif’s fundamentalism were turned on its head: as though the secularists agree that Muslims can only have one identity. What only a few are prepared to say but what most seem to mean is that Islam in particular, not religion in general, is the problem. Geert Wilders, a Dutch MP from the far-right Freedom Party, which boasts 9 seats out of 150 in Holland, has branded the Koran “a fascist book” on a par with Mein Kampf and has called for it to be banned. He insists there is no such thing as “moderate Islam” and that, if Mohammed were alive today, he would “be hunted down like a terrorist.”

War for Eternity: Inside Bannon's Far-Right Circle of Global Power Brokers

by

Benjamin R. Teitelbaum

Published 14 May 2020

Both of those campaigns crossed paths in Rome—the same Western European city where he was most likely to find Dugin, too. From 2017 and into 2018—while in political purgatory in the United States amid a public feud with Trump—Steve turned his attention toward Europe and attempted to collaborate with people like National Rally leader Marine Le Pen in France, Geert Wilders of the Dutch Party for Freedom, and Viktor Orbán in Hungary. His efforts were formalized on July 20, 2018. Then he assumed co-leadership of a Belgium-based organization called the Movement designed to assist European nationalist parties with tech savvy and policy design, to produce and share polling data, and to target advertising campaigns.

The Fourth Revolution: The Global Race to Reinvent the State

by

John Micklethwait

and

Adrian Wooldridge

Published 14 May 2014

At the height of the euro crisis Italy and Greece were bullied and shamed into replacing democratically elected governments with technocratic leaders in the form of Mario Monti and Lucas Papademos. The European Union is becoming a breeding ground for populist parties that claim to speak for “the ripped-off, lied-to little people” against the arrogant and incompetent elites. Geert Wilders, the leader of Holland’s Party for Freedom, rails against “this monster called Europe.” Marine Le Pen, the leader of France’s National Front, likens the EU to the old Soviet Union, doomed to collapse “under the weight of its own contradictions.” Greece’s Golden Dawn is testing the question of how far democracies can tolerate Nazi-style parties.

Hiding in Plain Sight: The Invention of Donald Trump and the Erosion of America

by

Sarah Kendzior

Published 6 Apr 2020

But no officials did—not with the courage and speed required, and not on behalf of the people they were supposed to serve. From the United Kingdom I headed to the Netherlands, where I had been invited to give a public talk about authoritarianism in Amsterdam. When I arrived, Dutch citizens were watching the rise of their own Trump-like figure, the bigoted demagogue Geert Wilders, who was running for office. I envied the Dutch parliamentary system, which mitigated the damage Wilders could do even with his coalition. The Dutch audience asked whether a Trump phenomenon could happen there, and I said, “Yes, it can happen anywhere.” This is the same answer I give everywhere I go, because the surest route to a kleptocratic takeover is to deny it’s happening, and the surest way to solve it is to sever it before it blooms.

Roller-Coaster: Europe, 1950-2017

by

Ian Kershaw

Published 29 Aug 2018

The Front National was backed by around a third of the French electorate. Alternative für Deutschland (founded only in 2012 and turning from initial Euroscepticism to an anti-migrant party) saw its support rise to more than 20 per cent of the electorate in a number of state elections during 2016. In the Netherlands the Party for Freedom led by Geert Wilders, who sought to have the Koran banned in the country and campaigned against what he called the ‘Islamization of the Netherlands’, became for a time the most popular party in the country during the migration crisis. Denmark, Sweden, Austria and Switzerland were among other countries in Western Europe to see a notable rise in support for parties focusing on what they saw as a threat from Islam to national culture.

…

Against expectations, Austria elected as its president in December 2016 (in a re-run election from the previous May, which had been annulled on grounds of voting irregularities) a strongly pro-European former leader of the Green Party, Alexander Van der Bellen, and rejected the far-right candidacy of Norbert Hofer from the Freedom Party. In the Dutch general election on 15 March 2017 the far-right anti-Islam and anti-immigrant candidate Geert Wilders did less well than expected – though his party nonetheless won 13 per cent of the vote, and the strong feeling on the migrant issue pushed the existing Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, in order to draw support from Wilders, also into engaging in anti-immigrant rhetoric. In the crucial French presidential election (in two rounds, on 23 April and 7 May 2017), the leader of the far-right Front National, Marine le Pen, who had been gaining strong support for her programme of restoration of national sovereignty, immigration control and exit from the Eurozone, was roundly defeated.

Revolution Française: Emmanuel Macron and the Quest to Reinvent a Nation

by

Sophie Pedder

Published 20 Jun 2018

In a dual attempt to free herself from her father’s shadow, and her party from his jack-booted and anti-Semitic thugs, Marine Le Pen had embarked on a strategy of dédiabolisation (de-demonization) to try to turn a toxic fringe movement with neo-Nazi links into a ‘patriotic’ party of government. To that end, she was generally more careful in her use of language than other European ultra-nationalists. Geert Wilders, her counterpart in the Netherlands and leader of the anti-immigrant Party for Freedom (PVV), called Islam ‘the ideology of a retarded culture’, and the Koran ‘fascist’. Marine Le Pen, by contrast, appealed to shared French secular values by denouncing ‘Islamification’, rather than Islam. ‘I don’t believe that Islam is incompatible with Western values,’ she said in 2011.

Europe old and new: transnationalism, belonging, xenophobia

by

Ray Taras

Published 15 Dec 2009

The objective was to teach tolerance and liberalism to certain groups of immigrants—EU nationals and citizens of the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Japan, and Switzerland were exempt from taking the test, and therefore watching the film. In practice, the DVD was offensive to most religious people, not just Muslims, and a prominent Dutch theologian spoke out against it. The Dutch “film wars” continued into 2008 when Geert Wilders, the leader of an anti-immigrant bloc in parliament, released a video called Fitnah (or “strife” in Arabic) containing scenes of a burning Qur’an and graphic executions. It sparked demonstrations in many Muslim-majority countries before the web site it had been posted on was shut down. Wishing to express solidarity with the Muslim community, a prominent Jewish leader in Holland placed an ad in a national newspaper that raised questions for all of Europe to reflect upon: “if Wilders were to say about Jews what he is saying about Muslims—in other words, if he advocated that temples be closed and rabbis deported—the entire country would rise in retaliation over such an anti-Semitic act.”83 NEW EUROPE’S NEW MORAL COMPASS?

The Ungrateful Refugee: What Immigrants Never Tell You

by

Dina Nayeri

Published 14 Sep 2020

The moral right of the author has been asserted British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library ISBN 978 1 28689 345 1 Export ISBN: 978 1 78689 346 8 eBook ISBN: 978 1 78689 347 5 For Sam and Elena. You make every country home. Why did you lie to me? I always thought I told the truth. Why did you lie to me? Because the truth lies like nothing else and I love the truth. – Mark Strand, ‘Elegy for My Father’ No Way. You will not make the Netherlands home. – Geert Wilders, message to refugees, 2015 To make someone wait: the constant prerogative of all power, ‘age-old pastime of humanity’. – Roland Barthes Contents Part One: Escape I. II. Darius III. IV. Kaweh and Kambiz Part Two: Camp I. II. III. IV. V. Majid and Farzaneh VI. VII. Valid and Taraa VIII.

Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World

by

Adam Tooze

Published 31 Jul 2018

As a spokeswoman for Moody’s commented: “The downside risks to global growth stem not from the possibility of a recession in the UK, but from the possibility that developments in the UK may give rise to increased political risk elsewhere in the EU.”84 Marine Le Pen hailed the Brexit referendum as a “dazzling lesson in democracy.”85 The right-wing nationalist Geert Wilders in the Netherlands called for a “Nexit” vote. Would a nationalist, Europhobic wave spread from Britain, Poland and Hungary to the rest of Europe? For almost a year after Brexit, that risk seemed all too real. And the stakes were high. Europe’s economic stabilization depended on calm in the bond markets.

…

As one analyst commented: “There is no guarantee that investors’ emotions will not turn wild again if signs of political contagion from the UK into mainland Europe become more visible.”86 The elections came thick and fast. In December 2016 a constitutional amendment in Italy was voted down, leading to the resignation of left-of-center prime minister Renzi. In Austria the presidential election was bitterly contested by the Far Right. In the Netherlands Geert Wilders and his right-wing party were on the march. Theresa May announced an election in Britain with a view to securing a large Brexit majority. But the real question surrounded France. Given the electoral base she had accumulated and the Front’s performance in the May 2014 European elections, there was little doubt that in the upcoming presidential election in May 2017 Marine Le Pen would make it into the final runoff.

The 9/11 Wars

by

Jason Burke

Published 1 Sep 2011

In 2007, they had said that ‘the situation surrounding the known jihadist networks in the Netherlands can … be described as reasonably calm’, arguing that ‘a [positive] phenomenon that was described [last year] in cautious terms appears to be a trend’.28 In March 2008, the release of a provocative film by populist anti-Islamic politician Geert Wilders had caused the threat level to be raised once more, but by mid-December 2009, the Dutch authorities were once again convinced that the danger from Islamic terrorism could be better described as ‘slight’ rather than ‘substantial’.29 In Germany too, there was a new calm – though inevitably punctuated by occasional scares.

…

Altogether, there were 113 anti-Semitic incidents in France during the month following the December 27 launching of Operation Cast Lead against Hamas in Gaza, including twenty-two attacks against private individuals and five attempts to burn down synagogues. Bernard Edinger, ‘Tense ties in France’, The Jerusalem Report, March 2, 2009, Paris. In the June elections to the European Parliament, Geert Wilders’ Dutch Party for Freedom in the Netherlands won 17 per cent of the national vote. The anti-immigrant British National Party, which warned of the ‘creeping Islamification’ of British society, won its first two seats. In Austria the right-wing Freedom Party almost doubled its share of the vote, at 13 per cent.

Roads to Berlin

by

Cees Nooteboom

and

Laura Watkinson

Published 2 Jan 1990

And yet, according to the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of March 21, 2012, the German citizen is still dedicated to the idea of Europe: 61 percent of Germans believe that Europeans belong together, in spite of all their problems, and 57 percent think that Europe is “our future.” Such figures are unlikely to be found among those who vote for the P.V.V., Geert Wilders’ party in the Netherlands, and certainly not in Britain, which is probably why many Europeans feel that country does not actually belong, because Britain has to some extent left the production of things to the Germans, living instead on the alchemy that transforms the froth of the markets into gold.

Dangerous Ideas: A Brief History of Censorship in the West, From the Ancients to Fake News

by

Eric Berkowitz

Published 3 May 2021

“The administration,” he continued, “is working to remedy this illegal situation.”148 The result was the executive order attacking Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. Assuming the role of a free-speech martyr is also part of the far-right toolkit in Europe. The veteran extremist politicians Marine Le Pen of France and Geert Wilders of the Netherlands have both routinely mounted (and often lost) vigorous free-speech defenses to charges for calumnies against minorities and immigrants. In doing so, they convert their messages of hatred into complaints of victimization, which in turn stoke the fears that drive their appeal. Carrying this stratagem forward, the young Danish politician Rasmus Paludan, who advocates the expulsion of Muslims from Demark, put himself on the political map by marching into Muslim neighborhoods and burning copies of the Qur’an, then posting videos of the confrontations on his YouTube channel.

21 Lessons for the 21st Century

by

Yuval Noah Harari

Published 29 Aug 2018

Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996); David Lauter and Brian Bennett, ‘Trump Frames Anti-Terrorism Fight As a Clash of Civilizations, Defending Western Culture against Enemies’, Los Angeles Times, 6 July 2017; Naomi O’Leary, ‘The Man Who Invented Trumpism: Geert Wilders’ Radical Path to the Pinnacle of Dutch Politics’, Politico, 23 February 2017. 2 Pankaj Mishra, From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt Against the West and the Remaking of Asia (London: Penguin, 2013); Mishra, Age of Anger, op. cit.; Christopher de Bellaigue, The Muslim Enlightenment: The Modern Struggle Between Faith and Reason (London: The Bodley Head, 2017). 3 ‘Treaty Establishing A Constitution for Europe’, European Union, 29 October 2004. 4 Phoebe Greenwood, ‘Jerusalem Mayor Battles Ultra-Orthodox Groups over Women-Free Billboards’, Guardian, 15 November 2011. 5 Bruce Golding, ‘Orthodox Publications Won’t Show Hillary Clinton’s Photo’, New York Post, 1 October 2015. 6 Simon Schama, The Story of the Jews: Finding the Words 1000 bc – 1492 ad (New York: Ecco, 2014), 190–7; Hannah Wortzman, ‘Jewish Women in Ancient Synagogues: Archaeological Reality vs.

Can It Happen Here?: Authoritarianism in America

by

Cass R. Sunstein

Published 6 Mar 2018

The same can be said regarding the recent performance of the Freedom Party’s Norbert Hofer in Austria’s presidential election. In both cases, the far-right populist candidate came close to winning the presidency of a major Western nation, and note, in neither case facing off against a contender from the traditional “left” or “right.” Geert Wilders’s Party for Freedom was blocked from the Dutch governing coalition, despite placing second, only via the determined collusion of all his mainstream opponents. Recent general elections in Germany and Austria have likewise seen a marked “populist” surge that upended “normal” politics. Whatever these political brands might once have represented, “left” versus “right” is being overturned in a new game of “insiders” versus “outsiders” . . . or so it seems.

Them and Us: How Immigrants and Locals Can Thrive Together

by

Philippe Legrain

Published 14 Oct 2020

Elsewhere in the EU, EU migrants have typically been much less controversial, with the notable exception of Romani (‘gypsies’). The small number of workers ‘posted’ to another EU country, and employed on the wages and conditions in their home country, have been another bugbear.12 Although far-right politicians, notably Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, have tried to make an issue of east European immigrants, he soon reverted to bashing Muslims instead.13 Popular concerns about migration have tended to focus on poor, non-white non-Europeans, notably refugees. Refugees When the drowned body of three-year-old Alan Kurdi washed up on a Turkish beach near the holiday resort of Bodrum on 2 September 2015, the images of the toddler prompted a wave of sympathy for people fleeing the barbarism that the regime of Bashar al-Assad has inflicted on innocent Syrians.14 Two days later, Chancellor Angela Merkel decided to open Germany’s borders to the many Syrian refugees who had traipsed across Europe to safety and were now trapped in hostile Hungary.

Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism

by

Harsha Walia

Published 9 Feb 2021

he probes.88 Orientalism, Said pens, is “a kind of Western projection onto and will to govern over the Orient,” a constituted entity based on structures from the past, “secularized, redisposed and re-formed.”89 In the Netherlands, for instance, anti-Muslim racism as the willed positional superiority of imperial racism can be traced from the country’s three-hundred-year colonization of Indonesia, which has the largest Muslim population in the world, to Dutch politician and Party for Freedom leader Geert Wilders’s current fanatic fixation on Islam. Wilders claims that Islam is an existential problem for women’s issues, crime, and the country’s public services. Wilders wants the closure of every mosque, a ban on the niqab in government buildings, and prohibition of the Koran—which he equates with Mein Kampf.

Three Years in Hell: The Brexit Chronicles

by

Fintan O'Toole

Published 5 Mar 2020

What better descriptions can there be of a Donald Trump speech than ‘an old bellows full of angry wind’ (‘A Prayer for My Daughter’) and ‘the barbarous clangour of a gong’(‘Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen’)? Yeats even anticipated the trend for stupid hair among right-wing male politicians (Trump, Boris Johnson, Geert Wilders) in ‘The Tower’: There lurches past, his great eyes without thought Under the shadow of stupid straw-pale locks That insolent fiend… We really should quote him on that. 31 July 2018 The British government has drawn up plans for a possible no-deal Brexit, hoping to bring the Irish and the Europeans to their senses.