Go, Flight!: The Unsung Heroes of Mission Control, 1965-1992

by

Rick Houston

and

J. Milt Heflin

Published 27 Sep 2015

Meeting at flight director’s console during flight of Gemini 5 8. Mission control overview during Apollo 8 9. Ken Mattingly 10. Gene Kranz’s Apollo 9 White Team 11. Flight controllers during Apollo 9 landing and recovery operations 12. Snoopy and Charlie Brown dolls overlook Charlie Duke 13. Jack Garman’s computer alarm cheat sheet 14. Charlie Duke during Apollo 11 landing 15. Dave Reed gets his launch plot board signed 16. Ken Mattingly during Apollo 13 launch 17. Mission control moments before start of Apollo 13 crisis 18. Glynn Lunney and Gene Kranz celebrate Apollo 13 splashdown 19. Sy Liebergot and Bill Moon 20. Charlie Harlan discusses a probe mockup with Gene Cernan and John Young 21.

…

Up a row was the throne itself, the flight director’s console. Chris Kraft, Gene Kranz, Glynn Lunney, Gerry Griffin, and Milt had all held court there once upon a time. Amazing. It was in those few moments when the concept for this book was born. Countless stories about human spaceflight have been told from the air-to-ground perspective, that is, mostly from the viewpoint of the astronauts whose flights this room controlled. A handful of people became relatively well known to the public at large due to what they did here—Building 30 is now named after Kraft, the godfather of all things mission control, and actor Ed Harris made Gene Kranz all the more legendary with his portrayal and “Failure is not an option” line in the blockbuster movie Apollo 13.

…

Von Ehrenfried would come to respect the man as a friend, mentor, and brother. “You start spending eight to sixteen hours a day with Gene Kranz, you’re going to learn something,” von Ehrenfried said. “Many times, we would work so hard, I would just kind of hope he would faint or something so I could get a break.” To von Ehrenfried, who also worked as a judo partner with Kranz, the AFD’s job was as simple as getting the flight director the information he needed when he needed it. Gene Kranz considered the AFD a safety valve, a wingman, he said, to keep watch over his six. He had flown the demilitarized zone in Korea and the Taiwan Strait during his time in the air force, and he was glad to have somebody watching his back.

Moonshot: The Inside Story of Mankind's Greatest Adventure

by

Dan Parry

Published 22 Jun 2009

Safire, NY Times, 12 July 1999, via NYTimes.com. 25 Hansen, op. cit. 26 Collins, op. cit. 27 Gene Kranz, roll 367, 07:36:00:09. 28 Collins, op. cit. 29 Ibid. 30 Ibid. 31 Ibid. 32 Ibid. 33 Ibid.; and Harland, op. cit. 34 Gene Kranz, Failure Is Not an Option. 35 Ibid. 36 Hansen, op. cit. 37 Ibid. 38 Kranz, op. cit. 39 Gene Kranz, roll 367, 07:30:34:16. 40 Ibid. 41 Kraft, op. cit. 42 Ibid. 43 Kranz, op. cit. Chapter 10: Pushed to the Limit 1 Dr James Hansen, First Man. 2 Gene Kranz, Failure Is Not an Option. 3 Interview with Gene Kranz in Glen Swanson (ed.), Before This Decade Is Out. 4 Hansen, op. cit. 5 Kranz, op. cit. 6 Ibid. 7 Ibid. 8 Hansen, op. cit. 9 Ibid. 10 Interview with Gene Kranz in Swanson (ed.), op. cit. 11 Kranz, op. cit. 12 Ibid. 13 Frank Borman, roll 386, 06:34:57. 14 Hansen, op. cit. 15 Kranz, op. cit. 16 Ibid.; and Hansen, op. cit. 17 Chris Kraft, Flight. 18 Ibid. 19 Ibid. 20 Hansen, op. cit. 21 Ibid.; Kraft, op. cit.; and David Harland, The First Men on the Moon. 22 Hansen, op. cit. 23 Kraft, op. cit. 24 Hansen, op. cit. 25 Michael Collins, Carrying the Fire. 26 Ibid. 27 Buzz Aldrin and Wayne Warga, Return to Earth. 28 Hansen, op. cit. 29 Ibid. 30 Ibid. 31 Collins, op. cit. 32 Hansen, op. cit. 33 Collins, op. cit. 34 Hansen, op. cit. 35 Kranz, op. cit. 36 Ibid. 37 Hansen, op. cit. 38 Kraft, op. cit. 39 Ibid. 40 Harland, op. cit. 41 Collins, op. cit. 42 Hansen, op. cit. 43 Collins, op. cit. 44 Harland, op. cit. 45 Ibid. 46 Ibid. 47 Armstrong, Aldrin, Collins, with Gene Farmer and Dora Jane Hamblin, First on the Moon; and Harland, op. cit. 48 Collins, op. cit. 49 Aldrin and Warga, op. cit. 50 Collins, op. cit. 51 Aldrin and Warga, op. cit.; and Hansen, op. cit. 52 Kraft, op. cit.; and Hansen, op. cit.

…

Chapter 12: The Eagle has Wings 1 Robert Godwin (ed.), Apollo 11, The NASA Mission Reports, Volume 2. 2 Gene Kranz, roll 368, 08:18:22:13. 3 Buzz Aldrin and Wayne Warga, Return to Earth. 4 Michael Collins, Carrying the Fire. 5 Armstrong, Aldrin, Collins, with Gene Farmer and Dora Jane Hamblin, First on the Moon. 6 Godwin (ed.), Apollo 11, The NASA Mission Reports, Volume 2. 7 Collins, op. cit. 8 David Harland, The First Men on the Moon; David West Reynolds, Apollo, The Epic Journey to the Moon; and Gene Kranz, Failure Is Not an Option. 9 http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/moon/peopleevents/p_wives.html 10 Armstrong, Aldrin, Collins, op. cit. 11 Ibid. 12 Ibid. 13 Ibid. 14 Ibid. 15 Ibid. 16 Ibid. 17 Ibid. 18 Ibid. 19 Ibid. 20 Kranz, op. cit. 21 Descriptions of white team from: interview with Gene Kranz in Glen Swanson (ed.), Before This Decade Is Out; and Kranz, op. cit. 22 Gene Kranz, roll 368-01, 08:18:22:13. 23 Kranz, op. cit.; interview with Gene Kranz in Swanson (ed.), op. cit.; and Gene Kranz, roll 368, 08:18:22:13. 24 Harland, op. cit. 25 Collins, op. cit. 26 Gene Kranz, roll 368, 08:18:22:13; and interview with Gene Kranz in Swanson (ed.), op. cit. 27 Dr James Hansen, First Man. 28 Ibid.; and Harland, op. cit. 29 For Armstrong's and Aldrin's accounts of the descent, see Godwin (ed.), Apollo 11, The NASA Mission Reports, Volume 2. 30 Interview with Gene Kranz in Swanson (ed.), op. cit.; and Armstrong, Aldrin, Collins, op. cit. 31 Aldrin and Warga, op. cit. 32 Ibid. 33 Armstrong, Aldrin, Collins, op. cit. 34 Ibid. 35 Ibid. 36 Ibid. 37 Deke Slayton, Deke!.

…

.; and Gene Kranz, roll 368, 08:18:22:13. 24 Harland, op. cit. 25 Collins, op. cit. 26 Gene Kranz, roll 368, 08:18:22:13; and interview with Gene Kranz in Swanson (ed.), op. cit. 27 Dr James Hansen, First Man. 28 Ibid.; and Harland, op. cit. 29 For Armstrong's and Aldrin's accounts of the descent, see Godwin (ed.), Apollo 11, The NASA Mission Reports, Volume 2. 30 Interview with Gene Kranz in Swanson (ed.), op. cit.; and Armstrong, Aldrin, Collins, op. cit. 31 Aldrin and Warga, op. cit. 32 Ibid. 33 Armstrong, Aldrin, Collins, op. cit. 34 Ibid. 35 Ibid. 36 Ibid. 37 Deke Slayton, Deke!. 38 Armstrong, Aldrin, Collins, op. cit. 39 Interview with Gene Kranz in Swanson (ed.), op. cit. 40 NASA's Lunar Surface Journal, at http://www.hq.nasa.gov/alsj/a11/a11.html 41 Ibid. 42 Godwin (ed.), Apollo 11, The NASA Mission Reports, Volume 2. 43 Aldrin and Warga, op. cit. 44 Ibid. 45 Armstrong, Aldrin, Collins, op. cit. 46 Interview with Gene Kranz in Swanson (ed.), op. cit. 47 Harland, op. cit.

Apollo 13

by

Jim Lovell

and

Jeffrey Kluger

Published 14 Jun 2000

Having paid his dues in the high-stress trenches of Mission Control through six Mercury flights and ten Gemini flights, Kraft had been more than content, after Jim Lovell and Buzz Aldrin’s Gemini 12, to turn things over to Gene Kranz and the rest of the team of flight directors who worked under him. At the moment, Kraft was taking a shower. It was a little before 10 P.M., and the last he’d heard, things were nominal at the nearby Space Center and in the Apollo spacecraft. The crew would be turning in for the night right about now, and Kraft intended to do the same. No need to keep graveyard-shift hours when there was Gene Kranz or someone else sitting at the flight director’s console. Through the bathroom door, Kraft thought he heard the phone ring once, then twice, then stop as his wife picked it up.

…

According to the schedule drawn up before this flight, Glynn Lunney’s Black Team would follow Gene Kranz’s White Team in the four-team rotation. Lunney, in turn, would be followed after eight hours by Gerald Griffin’s Gold Team, then Milt Windler’s Maroon Team. Now, all over the room fresh technicians from Lunney’s group were arriving at their posts, plugging their headsets into extra console jacks, and standing silently by the sides of the frazzled men who had been on duty since two o’clock that afternoon. At the flight director’s console, Lunney himself prepared to relieve Gene Kranz. At the EECOM console, Clint Burton came up beside Liebergot and laid a sympathetic hand on his shoulder; Liebergot looked up, smiled weakly, pushed away from the console, and gestured toward the seat with a sorrowful shrug.

…

What Kraft wanted to do was fire the descent engine now, get the ship back on its free-return slingshot course, and when it emerged from behind the moon and reached the PC+2 point, execute any maneuvers that might be required to refine the trajectory or increase its speed. In the past, when Chris Kraft had an idea like this, that idea got implemented. Nowadays, though, things were different. It was Gene Kranz who dictated the direction of things, Gene Kranz who was the true capo di tutti capi of the control room. If Chris Kraft wanted something done, he was free to suggest it to Kranz, but he could no longer decree it. In the aisle behind the flight director’s console, Kraft was about to stop Kranz’s pacing and discuss his two-step burn idea when Kranz turned to him.

Apollo 8: The Thrilling Story of the First Mission to the Moon

by

Jeffrey Kluger

Published 15 May 2017

* * * Creating the necessary software and writing the needed computer code was another hurdle for the Apollo 8 team. Gene Kranz might have given Bob Ernal the use of every computer in Buildings 12 and 30 for an entire weekend, but a thumbs-up from Ernal after just two days of work was hardly the final answer. It was, in fact, only the signal that it was time for a lot more people to get together and do a lot more work. For this, Bill Tindall would again play a role. Tindall, who had played a central part in the debate by Chris Kraft’s team about whether Apollo 8 should orbit the moon, was known by Gene Kranz and other higher-ups at NASA as “the architect”—a hat tip to his status as the person who had blueprinted all of the Apollo’s computer programs.

…

For twenty-one seconds, the astronauts knew what was happening to them and fought to save themselves. To anyone at NASA who had been paying attention throughout the year, the immolation of Grissom, White, and Chaffee was not an accident but an inevitability—equal parts tragedy and disgrace. * * * Gene Kranz, one of NASA’s top flight directors, was not in Mission Control on the night of January 27. Moments before the fire struck, he was home getting ready for dinner—a dinner that, he had been told, would involve grape leaves. That prospect did not especially please him, but there wasn’t much he could do about it.

…

“I want every one of you to go back to your offices and write those words on the top of your own blackboards,” he ordered. “You are not to erase them until we’ve put a man on the moon.” With that, he set down his chalk, turned on his heel, and left the stage. The lesson was over. * * * The news of the death of the three astronauts came to Frank Borman the same way it had come to Gene Kranz: with a knock at the door. Borman, Susan, and their boys were staying at a friend’s cabin on a lake in Huntsville, Texas, and they were just starting into a long weekend that would at last give Borman a break from the Apollo steeplechase. The race to get the ship off the pad less than three months after the last Gemini spacecraft flew had been exhausting, and the prelaunch stretch to come promised only to be worse.

In the Shadow of the Moon: A Challenging Journey to Tranquility, 1965-1969

by

Francis French

,

Colin Burgess

and

Walter Cunningham

Published 1 Jun 2010

As indicated by this book’s dedication, those who stay behind on the ground are often just as vital as those who get to go on a spaceflight, and this proved to be the case when researching and writing the book. Key interviews and some valuable editorial suggestions were made by spaceflight notables and family members Jeannie Bassett, Sam Beddingfield, Howard Benedict, Cece Bibby, W. O. Brown, Harriet Eisele, Susie Eisele Black, Wally Funk, Don Gregory, Gerry Griffin, Paul Haney, Jack King, Gene Kranz, Lola Morrow, Dale Myers, Dee O’Hara, Milt Radimer, Harvey RenshawJr., Kris Stoever, Teddy Taylor, Al Tinnirello, Hank Waddell, and Guenter Wendt. In some cases, the events we discussed were controversial, even personally painful at times, and we are most grateful that the participants found this project important enough for the story to be told correctly.

…

It was a clear dead-end assignment, as this would be the last Gemini flight, and training for it would keep Cooper from flying any of the earliest Apollo missions. Despite having commanded two very successful spaceflights, Slayton later said that Cooper was “basically marking time” by this point. His relationship with nasa managers had not improved, leading Flight Director Gene Kranz to describe Cooper as “the loner and rebel against the spaceflight bureaucracy.” “That’s fairly accurate,” was Cooper’s response when reminded of Kranz’s words. “The manned space program started with one hundred and fifty people involved in it. Ten years later we had sixty thousand . . . doing the same thing.

…

Doing so would be difficult, but a method was soon formulated to achieve it. Just over a day after the Agena explosion, all of the vital decision-makers were on board with the idea, and it was adopted. It was remarkably fast action for a federal agency, and almost unimaginable today. Flight Controller Gene Kranz still describes it as a “gutsy management decision,” saying the positive attitude of those on the ground toward making it happen was even more impressive than what happened in space. Schirra and Stafford were in favor of pushing the new plans even further, and having a Gemini 6 and 7 crew member change places during an eva.

Apollo

by

Charles Murray

and

Catherine Bly Cox

Published 1 Jan 1989

If sometimes Lunney got ahead of them, they didn’t get upset—“People who worked with him over a period of time became aware that he was just doing what’s normal for him,” a colleague said. “He couldn’t help it if it’s not normal for everybody else.” The third member of the triumvirate, Gene Kranz, was similar to Lunney only in his open relish of the job. Lunney looked as if he belonged in a Campbell’s Soup ad, whereas Gene Kranz looked like a drill sergeant in some especially bloodthirsty branch of the armed forces—hair cropped to a regulation military brush, with a wedge of a face cut into rough planes. Kranz was as relentless as he looked. “If nothing was going on, he would invent something,” said one of his controllers.

…

(Courtesy of Sy Liebergot) We can’t be sure, but this photograph was probably taken about an hour into the crisis on Apollo 13, as Don Arabian outlined the minimum voltages for operating the C.S.M. equipment to Gene Kranz. Sam Phillips (seated), head of the entire Apollo Program, watches. Glynn Lunney during the transfer of the crew into the LEM after the Apollo 13 explosion. Those surrounding Lunney include Chuck Dieterich (behind Lunney), Jerry Bostick (face partially hidden), Bill Tindall (seated), and Chris Kraft (with cigar). (NASA) Odyssey splashes down safely at the end of Apollo 13. Gerry Griffin, Gene Kranz, and Glynn Lunney lead the cheering. (NASA) Apollo as History Writing definitive history is a solemn undertaking and Apollo was not.

…

“Williams just walked up and said ‘Goddammit this’ and ‘Goddammit that,’ and got everybody saluting and doing what they should do.” He was a genius of sorts, Lunney reflected, “though if you had to go up against him, he didn’t seem like a genius. He seemed like a bull.” In those days, he even looked like a bull—over 200 pounds, a powerful man with a square head, dark, close-cropped hair, and heavy brows. Gene Kranz, who himself would scare a few people in his time, never forgot his first encounter with Williams. It happened in 1960, just a few weeks after Kranz had arrived at the Space Task Group. Kranz had been sent over to brief Williams on some work he’d been doing. Kranz, who knew Williams only by reputation, got there early and slipped into a seat in Williams’s office while another briefing concluded.

Into the Black: The Extraordinary Untold Story of the First Flight of the Space Shuttle Columbia and the Astronauts Who Flew Her

by

Rowland White

and

Richard Truly

Published 18 Apr 2016

FIFTY Houston, 1981 There were three separate Flight Control teams assigned to the Shuttle flight, each with responsibility for a different phase of the mission: silver, bronze and crimson; ascent, on orbit and descent. With Columbia safely established on orbit, Dan Brandenstein passed his seat at the CapCom console to Bronze Team’s Hank Hartsfield, while Brandenstein’s Silver Team flight director, Neil Hutchinson, joined Gene Kranz, the pugnacious deputy director of Flight Operations who would one day be credited with the line “Failure is not an option,” for the change-of-shift press conference. An excited press corps was waiting for them in the space center’s Building 2 auditorium. And there was one subject, above all others, that they wanted to know about.

…

Inside Sunnyvale’s Blue Cube, operators from the Air Force Satellite Control Facility’s Special Projects Office were already working on the problem, comparing the orbits of the two KH-11 KENNENs on station with those of Columbia, trying to establish whether or not it was even going to be possible to attempt to capture a picture of the Shuttle. • • • As Gene Kranz and Neil Hutchinson continued to field questions about how they planned to capture pictures of the orbiter, Bob Crippen and John Young returned to the flight deck to prepare the orbital maneuvering system engines for two further burns to push Columbia into her definitive 147-mile circular orbit.

…

“See you mañana,” Crippen signed off from on board Columbia, while in Houston, Hartsfield’s Bronze Team leader, Flight Director Chuck Lewis, on finishing his shift, made his way to Building 2 and installed himself in Room 135 for the change-of-shift press conference—and another barrage of questions from reporters about the tiles. They were becoming more forensic, scratching harder at some of the suggestions Gene Kranz had made about possible orbits for taking pictures from ground-based systems. “I’ll tell Mr. Kranz when I see him tomorrow,” Lewis joked, “that everyone’s anxious for him to come back over and talk to you.” Kranz, not this time leading one of the Flight Control teams himself, was responsible for the offline effort to establish the integrity of the heat shield.

Apollo 11: The Inside Story

by

David Whitehouse

Published 7 Mar 2019

None more so than the astronauts, their families, and all those intimately involved in Apollo – the project to land a man on the Moon. On that evening, 20 July 1969, everyone in Mission Control in Houston knew the danger. The lives of the two men about to attempt a descent to the lunar surface depended upon single moments, the single decision any of them might have to make in a second. Gene Kranz, 31 years old, was the Flight Director for the landing. He was confident in his abilities, though not arrogant. His job was to run the show by being able to assimilate all the information coming into Mission Control from ‘Eagle’, the Lunar Lander. Formerly a fighter pilot and an engineer, he was leading a talented group.

…

They swirl around the capsule and go in front of the window and they’re all brilliantly lighted.’ Later they were identified as flakes of paint from his capsule. On the third orbit a potentially serious situation occurred. A sensor on board Friendship 7 indicated that the heat shield was loose. If it broke away during re-entry Glenn would perish. Gene Kranz, then a Procedures Officer in Mission Control, remembers the incident as a key moment in the evolution of mission operations: What the crew was seeing, we were seeing on board the spacecraft in Mercury. It was only as we moved into Gemini that we recognized the need to move deeper into the spacecraft system.

…

Six minutes before retrofire, Glenn manoeuvred Friendship 7 into a 14-degree, nose-up attitude. The first retrorocket fired. The second and third retrorocket firings came at five-second intervals, slowing the capsule sufficiently to drop it out of orbit. Once again, Schirra said, ‘Keep your retro pack on until you pass Texas.’ ‘I looked around the room,’ wrote Gene Kranz in his autobiography, Failure Is Not an Option, ‘and saw faces drained of blood. John Glenn’s life was in peril.’ In Florida, Capcom Al Shepard said, ‘We feel it is possible to re-enter with the retro package on. We see no difficulty at this time with this type of re-entry.’ After the mission Glenn said he was annoyed at being kept in the dark about such a serious problem.

Shoot for the Moon: The Space Race and the Extraordinary Voyage of Apollo 11

by

James Donovan

Published 12 Mar 2019

He was the most introspective of the Mercury Seven, though some NASA officials considered him “flaky” or “vague and detached.” The new guy in Mercury Control was anything but flaky. Sitting next to Kraft in the control room for the first time, in the new position of assistant flight director, was twenty-eight-year-old Gene Kranz, a former air force fighter pilot. After a couple of years as a flight-test engineer with McDonnell, in October of 1960 the crew-cut Kranz had hired on with the Space Task Group. Two weeks after Kranz started, and shortly before the first Mercury-Redstone launch, Chris Kraft needed someone to do an important job and found only Kranz available.

…

The new Mission Operations Control Room in Building 30 (there were two MOCRs, actually, one on the second floor, used for simulations and practice runs, and one on the third, used for all the Gemini and Apollo Saturn V missions) was larger and more up-to-date and would host not one or two but three shifts of flight controllers for around-the-clock operations. Gene Kranz would oversee one shift; he named his team White, in contrast to Kraft’s Red team. John Hodge, the pipe-smoking engineer whose gray hair and British accent gave him a distinguished air, would handle the third shift, Blue. (Each flight director picked his team’s color; when a flight director left, that color was retired.)

…

Nine hundred miles away from the Cape, at Mission Control in Houston, John Hodge and a roomful of flight controllers had been monitoring the countdown through voice and radio only. When several of them suddenly lost telemetry, heard something about a fire, then lost communications with the Cape, it was unclear what was happening, but they knew it wasn’t good. Hodge called Kraft from his office, and they soon found out. Gene Kranz had been at home, getting ready to go out with his wife, when his next-door neighbor, a NASA branch chief, knocked on his door and told him of the fire. He raced back to the MSC, but there was nothing he or anyone there could do. One flight controller broke down in the parking lot outside the control center, sobbing and saying, “It’s horrible!

A Man on the Moon

by

Andrew Chaikin

Published 1 Jan 1994

Soon the spacecraft would reappear, and if all had gone according to plan, Eagle would be on its way down to 50,000 feet. Gene Kranz and his team of flight controllers—they were called the White Team—sat at their consoles, wearing lightweight headsets, anticipating the Acquisition of Signal. For the moment their television screens, normally full of up-to-the-minute data, were static. Behind the controllers, in a glassed-in gallery that looked out over the control room, NASA managers, current and former astronauts, and other VIP's crowded together to witness the drama to come. Just looking at them drove home the fact that this was not a simulation. In the third row of the MOCR, Gene Kranz sat at the flight director's console wearing a brand new white vest.

…

Grumman engineers had envisioned using the lander’s engines to push a crippled command ship out of lunar orbit. Eight years later, training for Apollo 9, Gene Kranz’s flight controllers were hit with a simulation in which Jim McDivitt and Rusty Schweickart were stranded in a lopsided orbit around the earth. They had to devise ways to stretch the LM’s supplies to last 30 hours instead of 18, long enough for Dave Scott to rescue them. While that exercise foreshadowed the effort to save Lovell’s crew, no one ever envisioned using the LM in precisely the way it was used on Apollo 13 (sources: the author’s interviews with Gene Kranz; Murray and Cox, A polio: The Race to the Moon, p. 423). 305 Power values for radio and environmental control system: These numbers were supplied by former flight controller Robert Legler.

…

I was thirteen when Armstrong and Aldrin landed on the moon; like countless other space-struck teenagers, I kept a daily vigil in front of the TV, surrounded by press kits, lunar maps, and scale models of rockets and spacecraft. That passion stayed with me when I embarked on a science journalism career, writing articles on astronomy and space exploration as an editor of Sky & Telescope magazine. The Space Shuttle era had arrived, but for me, it was Apollo that held special fascination. By 1984 I had interviewed Gene Kranz, the flight director who had been in the trenches of mission control during the first lunar landing, and Harvard geologist Clifford Frondell, who had been present when the first box of moon rocks was opened inside the windowless expanse of NASA’s Lunar Receiving Laboratory. For an article on space motion sickness I had experienced weightlessness aboard a special NASA cargo plane used for astronaut training.

Moon Shot: The Inside Story of America's Apollo Moon Landings

by

Jay Barbree

,

Howard Benedict

,

Alan Shepard

,

Deke Slayton

and

Neil Armstrong

Published 1 Jan 1994

With an outdated crew cut adding starkness to his features, Gene Kranz seemed strangely out of place among his team. He was the final authority, the flight director whose sweeping powers would decide the what, when, and where of the first ever descent and landing on the moon. Now, with Eagle dropping silently toward lunar dust and craters, no one called him by his name. He answered to Flight. Kranz leaned into his communications panel. With an easy motion he switched from the standard talk network to an auxiliary loop. Now he could be heard only within Mission Control. What Gene Kranz had to say was meant for his team only.

…

To hell with that, Bales judged. He and Garman had programmed the Eagle’s computer so all the key functions were performed in the time allotted. His computer was working, and that’s what mattered. But Neil Armstrong’s voice demanded a response. “Give usthe reading on that twelve-oh-two program alarm.” “GUIDO?” Gene Kranz shouted the question into the loop of Mission Control. Everyone hung on the edge of the cliff. Bales wanted more time. Kranz didn’t have time. Armstrong and Aldrin didn’t have a single second to spare as they plunged downward. Kranz stared at Bales. The flight director slammed a clenched fist against his console.

…

Deke Slayton knew they had to leave it to the pilots on the final approach. As Eagle skittered over boulders and across craters, only Neil Armstrong’s judgment counted. He was there. He was flying. The clock was ticking away precious fuel. Charlie Duke looked at Deke and held up both hands, palms out. He didn’t need to voice the question. Gene Kranz did it for him on the internal communications loop. Everyone heard his words. “CapCom, this is Flight.” Kranz’s words to Duke were firm and steady. “You’d better remind them there ain’t no damn gas stations on the moon.” Charlie nodded and keyed his mike. A timer stared at him. “Thirty seconds.”

Moondust: In Search of the Men Who Fell to Earth

by

Andrew Smith

Published 3 Apr 2006

Aldrin instructed the computer to supply the alarm code and “1202” flashed onto the screen. He didn’t know what this meant, but suspected that it was something to do with the computer being overloaded. This had failed to happen in any of the simulation he’d been a part of. Now wasn’t the time for it. The focus turned to Earth and the thirty-five-year-old flight director, Gene Kranz. He knew the alarm was serious, because he’d seen something like it back in the first week of July and he’d aborted the virtual mission as a result. The truth was that he and his staff had been having problems for the last hour, with communications cutting out – sending Mission Control screens blank and filling headsets with static – then resuming for barely long enough to justify continuing the descent.

…

I felt a mix of awe and envy for the Baby Boomers who defined the Space Age: for the Brits who had escaped the drabness of their parents’ world through fanatic devotion to that visceral black American music, the voice of a southern underclass who – like them – hadn’t yet tasted the lily-white prosperity of the Eisenhower years, who, as members of the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Who, Yardbirds, Animals, Kinks, Cream, Fleetwood Mac, Derek and the Dominoes, Jimi Hendrix Experience, Velvet Underground, Faces, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Pink Floyd, Free, laid down so much of the sound track to the Space Age; and also for the American engineers, because, while the lunar astronauts were older than commonly imagined, the average age of Gene Kranz’s Mission Control team at the time of Apollo 11 was twenty-six. So I’m beginning to see why space and the counterculture have always seemed connected to me, why von Braun’s Saturn V and the white Fender Stratocaster guitar with which Hendrix skewered the national anthem at Woodstock less than a month after the first Moon landing sit in my mind as the two most potent icons of the second half of the twentieth century.

…

They were America’s yin and yang, symbolic of the ways in which it chose to spend its incredible wealth and vitality. Someone said that Apollo represented “the triumph of the squares,” but the great good fortune of squares and freaks alike was to be involved in something that they could – had to – make up as they went along. Gene Kranz told me: “Everything we needed to go to the Moon with, we had to create – and this joy of creation was a marvel to behold …” When we draw on the Sixties for music, movies, fashion, fiction, this is what we’re after – which is ironic, because innocence is the one thing you can’t re-create, can only parody.

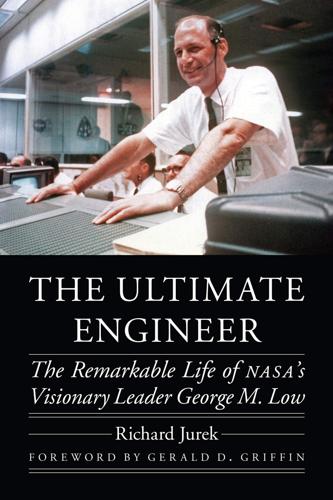

The Ultimate Engineer: The Remarkable Life of NASA's Visionary Leader George M. Low

by

Richard Jurek

Published 2 Dec 2019

Tariq Malik, “NASA’s Space Shuttle by the Numbers: 30 Years of a Spaceflight Icon,” Space.com, 21 July 2011, https://www.space.com/12376-nasa-space-shuttle-program-facts-statistics.html. 60. George Low, keynote speech, symposium of the National Security Industrial Association and the Armed Forces Management Association, Washington DC, September 1972, George M. Low Papers, 1930–1984. 61. Gene Kranz, interview by Roy Neal, 28 April 1999, NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project. 62. Bill Anders, interview by the author, 28 June 2016. 63. Gene Kranz, interview by Roy Neal, 28 April 1999, NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project. 64. Richard Nixon, “President Nixon’s 1972 Announcement of the Space Shuttle,” 5 January 1972, NASA, last updated 30 March 2009, https://history.nasa.gov/printFriendly/stsnixon.htm. 65.

…

He famously once described Low as a great “knitter of people,” someone who would bring order and harmony out of the chaos and doubt caused by the fire. “George brought the program out of despair and brought it back into the light.”20 He was “a master at getting people to work together, creatively channeling their energies and thus building the momentum to achieve the objective,” legendary flight director Gene Kranz said in describing Low’s impact on the program. “The flight directors knew him well from his middle-of-the-night visits to Mission Control during a flight, where he sat silently in the viewing room. He had a rare blend of integrity, competence, and humility. You would do whatever he asked you to do, regardless of the odds and regardless of the risks.”21 Astronaut Frank Borman agrees with both Lunney and Kranz: “As usual with any great endeavor, it always boils down to a single human being who makes a difference.

…

The other idea involved a trip to the moon: “Assuming it will take a long time to fully-qualify the LM,” Low wrote in his notes, “consider a manned circumlunar mission with the CSM only in our planning.”116 It was an idea that stuck in Low’s head and refused to leave, moving closer and closer to the fore each time he’d get a report of more LM schedule slippages and problems. It practically screamed at him after talking to McDivitt. Gene Kranz recalls that after Low started as program manager that April, Kraft came to a mission-planning staff meeting and had the team simulate different kinds of lunar trips around a four-thousand-mile orbit. “But it still had a CSM and LM in it,” Kranz said.117 As Kranz sees it, Kraft’s idea inspired Low, and this early simulation work put a lot of the data on the shelf for when Low needed a way to overcome the LM delays.

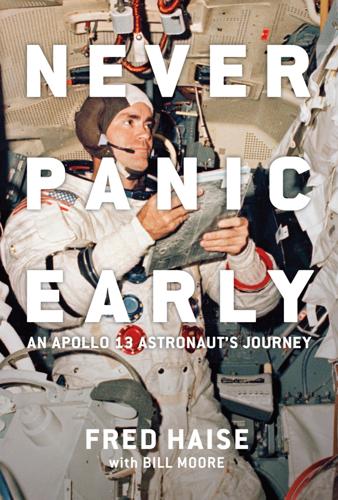

Never Panic Early: An Apollo 13 Astronaut's Journey

by

Fred Haise

and

Bill Moore

Published 4 Apr 2022

a_prh_6.0_139653422_c1_r1 Dedicated to the more than 400,000 participants in the Apollo program who made what seemed to be an impossible goal attainable. TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD BY GENE KRANZ ACRONYM LIST MY BEGINNINGS LEAVING THE NEST AND LEARNING TO FLY INTO THE JET AGE BACK TO SCHOOL AND INTO NASA THE X-SERIES MY INTRODUCTION TO AEROSPACE LIFE ON THE EDGE OF SPACE MY TICKET TO THE MOON ODYSSEY—A PERFECT NAME A SUDDEN DETOUR BACK TRAINING FOR THE MOON A RETURN TO FLIGHT TESTING JOINING THE IRON WORKS IN THE ROCKING CHAIR ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INDEX FOREWORD BY GENE KRANZ Hundreds of books have been written by astronauts, and while reading Fred Haise’s early, well-written chapters, I concluded that Never Panic Early serves two purposes.

…

More than twenty-five years later, one afternoon, after retiring from Northrop Grumman, I decided to listen to the various voice loops in Mission Control during the two hours and forty-six minutes, from the oxygen tank explosion to Jack’s decision to shut down the Odyssey. From my training through three missions, I knew many of those involved in the various disciplines by their voices. I detected a change in tone from some of the men when they had run out of ideas. Flight director Glynn Lunney and his black team had replaced mission director Gene Kranz and his white team shortly after the explosion. Lunney called the team to attention with the call to get Odyssey powered down because we were starting to eat into the three small forty-four-amp-hour entry batteries. This was unprecedented, because there was no procedure to shut down the CSM Odyssey since no one ever thought it would be necessary.

…

Somewhat wistfully, I wished that Aquarius had a heatshield, too. I’d like to have that LM sitting right in my backyard. Because of the staph infection, I still felt ill, so I missed a ticker tape parade in Chicago, but Jim and Jack, plus director of flight operations at MSC Sig Sjoberg and the four mission flight directors Gene Kranz, Glynn Lunney, Gerry Griffin, and Milt Windler rode in the parade. I did make the festivities in New York City, hosted by Mayor John Lindsay. On the receiving line in Rockefeller Center, we greeted several thousand people. A luncheon followed that included Grumman management and many New York dignitaries.

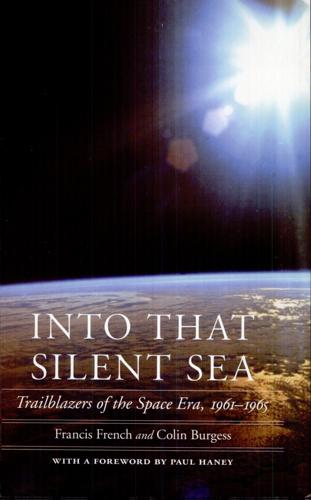

Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers of the Space Era, 1961-1965

by

Francis O. French

,

Colin Burgess

and

Paul Haney

Published 2 Jan 2007

Sadly, Gordo passed away soon after being sent some final manuscript drafts of this book, which he'd agreed to proofread. Those who stay behind on the ground are often just as vital as those who get to fly into space. Key interviews and valuable editorial suggestions were made by spaceflight notables and family members Max Ary, Cece Bibby, Wally Funk, Lowell Grissom, Paul Haney, Gene Kranz, Jim Lewis, Dee O'Hara, and Guenter Wendt. In some cases the events covered were controversial, and we are most grateful that the participants found this project important enough to have the story told correctly, with history in mind. Special and abundant thanks are due to Kris Stoever, who devoted a great deal of time and effort to ensuring that we attained the utmost accuracy.

…

Though in the early part of his nasa tenure Lewis had continued to serve in the Marine Reserves, in 1983, after twenty years of service, he retired with the rank of major. In the 1983 movie of Tom Wolfe's best-selling book The Right Stuff, Gus Grissom was characterized as a panicky man who may have blown the hatch prematurely. Far more accurate portraits of Grissom and his spacecraft are given by people who knew both very well. Gene Kranz joined the nasa Space Task Group in i960; he was assistant flight director for Project Mercury, and later flight director on Apollo 11. In an interview with the authors he dismissed the unflattering speculation about Grissom with a few terse words: "I spent a lot of time with Gus. Everybody alleges that the guy panicked.

…

Fielding the customary question, he replied simply: "I have been training and waiting for three years, and a few more days won't matter." Years later, Carpenter agreed. "The delays didn't bother either of us much. It gave us both more time to get ready. And you figure it's just part of the job—if something fails, you wait for it to be fixed and try again." Gene Kranz, then assistant flight director, explained their patience: We had no orbital experience. We had about thirty minutes of experience with Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom's missions. The preceding orbital, unmanned mission was targeted for three orbits but actually completed only two. There was risk with that, but the real question with me was the integrity of the Atlas booster.

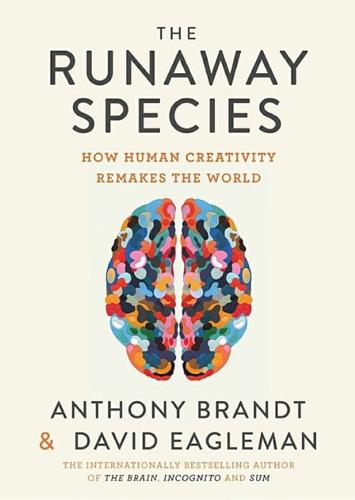

The Runaway Species: How Human Creativity Remakes the World

by

David Eagleman

and

Anthony Brandt

Published 30 Sep 2017

Astronaut Jack Swigert, with the understatement of a military man, radios Mission Control. “Houston, we’ve had a problem.” The astronauts are over 200,000 miles from Earth. Fuel, water, electricity and air are running out. The hopes for a solution are close to zero. But that doesn’t slow down the flight director back in NASA Mission Control, Gene Kranz. He announces to his assembled staff: When you leave this room, you must leave believing that this crew is coming home. I don’t give a damn about the odds and I don’t give a damn that we’ve never done anything like this before … You’ve got to believe, your people have got to believe, that this crew is coming home.1 How can Mission Control make good on this promise?

…

The craft was hundreds of thousands of miles away, so any solution had to draw on materials within the astronauts’ reach. The NASA engineers had an inventory of everything on board the craft, they had the experience gained in earlier Apollo missions, and they had the experience of running many simulations. They drew on all that knowledge while crafting their rescue plans. Gene Kranz wrote afterwards: I was now grateful for the time we had spent before the mission … developing options and workarounds for all conceivable spacecraft failures. We knew that when the chips were down we could use the command module survival water, condensed sweat and even the crew’s urine in place of the [lunar module] water to cool the systems.

…

By 2,627, my wife and I were really counting our pennies. By 3,727, my wife was giving art lessons for some extra cash. These were tough times, but each failure brought me closer to solving the problem.4 THE PUBLIC CAN SAY NO When the Apollo 13 spacecraft was careening through space with a dwindling oxygen supply, Gene Kranz declared to the NASA engineers that “failure is not an option.” Their rescue mission worked, but the happy final act shouldn’t blind us to the fact that the risks they took were real. Failure is always an option. Even great ideas have no guarantee of success. Take Michelangelo. Twenty years after painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling, he was commissioned to paint a fresco of the Last Judgment above the chapel’s altar.

Think Like a Rocket Scientist: Simple Strategies You Can Use to Make Giant Leaps in Work and Life

by

Ozan Varol

Published 13 Apr 2020

Kennedy asked his nation “to do what most people thought was impossible,” as Apollo astronaut Gene Cernan recalled, “including me.”7 The promise to put a human being on the Moon in less than a decade was so incredible, remembers Robert Curl, a Rice University professor who was in the audience for Kennedy’s speech, “I came away in wonder that he was seriously proposing this.”8 Famous NASA flight director Gene Kranz—who was played by Ed Harris in the movie Apollo 13—was also stunned by Kennedy’s bold pledge.9 For Kranz and his NASA colleagues “who had watched [their] rockets keel over, spin out of control, or blow up, the idea of putting a man on the Moon seemed almost too breathtakingly ambitious.”10 But Kennedy was well aware of the difficulties ahead.

…

Because the service module was damaged from the explosion, they had to figure out how to use the lunar module—intended only to shuttle two astronauts to the lunar surface—as a lifeboat for returning all three astronauts back to Earth. But the reality was much calmer than its Hollywood depiction. Gene Kranz, the flight director for the mission, had conducted regular dress rehearsals to train mission controllers to solve complex problems in stressful situations.31 In fact, a similar type of contingency requiring the astronauts to use the lunar module as a lifeboat had been simulated before. “No one had ever simulated exactly what happened,” Apollo astronaut Ken Mattingly explains, “but they had simulated the kind of stress that could be applied to the system and the people in it.

…

Failure Is an Option In Apollo 13, there’s a scene where a group of rocket scientists are gathered in a room after learning that the spacecraft suffered an oxygen tank explosion on its voyage to the Moon. The spacecraft’s power is dangerously low, and the astronauts’ days are numbered. The scientists in mission control must figure out a way to get them back before their power runs out. “We never lost an American in space. We’re sure as hell not going to lose one on my watch,” roars Gene Kranz, the flight director, before adding the punch line: “Failure is not an option.” Kranz later wrote an autobiography with the same title, where he described the tagline as “a creed that we all lived by” in mission control.8 NASA gift shops quickly capitalized on the credo and began selling T-shirts emblazoned with the words Failure Is Not an Option.

Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days

by

Jake Knapp

,

John Zeratsky

and

Braden Kowitz

Published 8 Mar 2016

Finally, you’ll pick a target: an ambitious but manageable piece of the problem that you can solve in one week. 4 Start at the End Everybody knows the story of Apollo 13, but just in case, it goes like this: Astronauts head to moon, explosion on spacecraft, nail-biting return to earth. In Ron Howard’s 1995 movie version, there’s a scene where the team at Mission Control gathers around a blackboard to form a plan. Gene Kranz, the flight director, wears a white vest, a flattop haircut, and a grim expression. He grabs a piece of chalk and draws a simple diagram on the blackboard. It’s a map showing the damaged spacecraft’s path from outer space, around the moon, and (hopefully) back to the earth’s surface—a trip that will take more than two days.

…

That’s smart. And that’s the same way your team will start your sprint. In fact (with the luxury of unlimited oxygen) you’ll devote the entire first day of your sprint to planning. Monday begins with an exercise we call Start at the End: a look ahead—to the end of the sprint week and beyond. Like Gene Kranz and his diagram of the return to planet earth, you and your team will lay out the basics: your long-term goal and the difficult questions that must be answered. Starting at the end is like being handed the keys to a time machine. If you could jump ahead to the end of your sprint, what questions would be answered?

…

We were all gathered around a whiteboard, where the team had drawn and redrawn (and re-redrawn) the map. The top How Might We notes were stuck beside corresponding steps in the process. To an outsider, it might have looked like a mess of arrows, text, and sticky notes. To our team, it was as clear as Gene Kranz’s diagram of the Apollo 13 flight path. At last, it was time to make the final decision about where to focus the sprint. Amy needed to choose one target customer and one target moment on the map. Those of us from GV were bracing for a long discussion. But when Jake asked Amy if she was ready, she nodded and grabbed a marker.

Spacewalker: My Journey in Space and Faith as NASA's Record-Setting Frequent Flyer

by

Jerry Lynn Ross

and

John Norberg

Published 31 Jan 2013

–Neil ArmStroNg, Commander of Apollo 11 “this is the story of one man’s lifelong quest to explore the unknown, overcome setbacks and obstacles, and keep the beacon of space shining in the hearts of all people, young and old. this book is about an American Dream.” –eugeNe CerNAN, NASA gemini and Apollo astronaut “this book is the story of a common man from the midwest who became an American hero . . . a model for the youth of our nation and for those who will accept the challenge to follow in his footsteps.” –geNe KrANz, NASA Flight Director for gemini and Apollo, including Apollo 11 and 13 From the age of ten, looking up at the stars, Jerry ross knew that he wanted to journey into space. this autobiography tells the story of how he came not only to achieve that goal, but to become the most-launched astronaut in history, as well as a NASA veteran whose career spanned the entire uS Space Shuttle program.

…

Most astronauts of my day would fly but two or three missions, but Jerry Ross faced the fire and the risks of launch day repeatedly.This book is the story of a common man from the Midwest who became an American hero . . . a model for the youth of our nation and for those who will accept the challenge to follow in his footsteps.” –Gene Kranz, NASA Flight Director for Gemini and Apollo, including Apollo 11 and 13; author of Failure Is Not an Option “As a NASA training manager, I knew Jerry Ross as one of the steadiest and smartest astronauts in the agency. He was also one of the nicest! No matter who you were or what your job was, Jerry always took the time to express his appreciation for the work you were doing.

…

After several months I was named the payload officer and flight controller responsible for the operational integration of all military payloads being planned for future Shuttle missions, and that kept me busy. In my role as payload officer, I worked with many groups around the Johnson Space Center and got to know some people who had been part of the Apollo program. I met Gene Kranz, the legendary Flight Director who led Mission Control’s efforts to land Apollo 11 on the Moon and to safely return the crew of Apollo 13 to Earth. Gene was a former US Marine fighter pilot, and his flat-top haircut, broad shoulders, and powerful personality embodied the tough and competent approach that he instilled in his Flight Directors and his flight control teams.

"Live From Cape Canaveral": Covering the Space Race, From Sputnik to Today

by

Jay Barbree

Published 18 Aug 2008

“If it does not occur again, we’re fine.” Bales agreed, and he judged Eagle’s main computer was doing its job. He keyed his mike. “GO!” he shouted. Charlie Duke showed surprise. “We’ve got, uh, we’re GO on that alarm, Eagle.” The beat speeded up. Armstrong and Aldrin were four thousand feet above the moon. Flight director Gene Kranz opened his mike. “All right, you guys. It’s coming up on GO, or NO GO for landing. What’s it going to be?” Every flight controller in the trenches responded with “GO.” Charlie Duke called the American craft descending on the moon. “Eagle, you’re GO for landing.” Three thousand feet up, another alarm rang in Eagle’s cabin.

…

He was instantly aware that they had lost any hope of landing on the moon, and the immediate emergency was simply staying alive. His ship was in a circumlunar orbit—a figure-eight flight path around both Earth and the moon—and in this orbit, without a miracle, they would be marooned. If the crew of Apollo 13 were to survive, experts on the ground had only hours to calculate and engineer a rescue. Gene Kranz, the no-nonsense flight director who had landed Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon, was in charge. He began by calming his shocked flight-control team. “Okay, now let’s everybody keep cool,” he said. “We’ve got the LM still attached. The LM is still good, so if we need it to get back home then let’s solve the problem.

…

The guidance platform was a collection of gyroscopes and instruments needed to keep the spaceship aligned precisely with Earth and the moon—to keep Apollo 13’s location known to Mission Control every moment of the flight. Even though Apollo 13’s crew would now be sustained by the lunar module, the astronauts would need to return to the cold, damp, hibernating command ship for food and bathroom facilities. It promised to be an uncomfortable ride. Flight director Gene Kranz and his team decided to use the lunar-module descent engine for needed propulsion. They worked out a couple of rocket burns that should bring the Apollo 13’s crew safely home: “We’ll go for a brief burn a few hours from now before they reach the moon. That will give them the free-return trajectory.

Amazing Stories of the Space Age

by

Rod Pyle

Published 21 Dec 2016

Communications were spotty; the computer was threatening to quit, and Gene Kranz, the flight director for this first lunar landing, felt Mission Control slip a bit further behind the power curve. All they could do was listen, and wait. Most people knew that going to the moon was risky. Few outside of Mission Control, listening to the communication between the astronauts and Houston, understood the urgency of the message. Now the dangers were no longer theoretical; they were being played out in space at that very moment. Much later, Gene Kranz related the stakes as he had outlined them to the controllers just before the landing.

…

He grimaced at the memory. “No more givebacks…. We've trained well. They have confidence in us. We have confidence in them. And then it's up to them and the spacecraft to finish off the mission.”19 Apollo 11's mission ended in the tropics of the Pacific Ocean, splashing down near Wake Island. In Mission Control, Gene Kranz and his team celebrated by clapping, whistling, and passing out cigars.20 The first lunar landing was complete, and five more crews would follow to the moon's surface, conducting increasingly ambitious, and still highly risky, missions. But rising above it all, in Kranz's memory, is the overwhelming nature of the accomplishment.

…

Broadcasting Magazine, July 28, 1969, republished in “A Remote that Broke All the Records,” Broadcasting and Cable, July 17, 2009, http://www.broadcastingcable.com/news/news-articles/remote-broke-all-records/110227?rssid=20065 (accessed September 6, 2016). 4. For all flight dialogue and quotes: Eric M. Jones, ed., “Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal,” NASA, https://www.hq.nasa.gov/alsj/frame.html (accessed September 15, 2016). 5. Gene Kranz, in an interview with the author, Johnson Space Center, 2005. 6. Buzz Aldrin, in an interview with the author, 2005. 7. Steve Bales, in an interview with the author, 2005. 8. Aldrin, interview with the author. 9. Ibid. 10. Charlie Duke, in an interview with the author, 2005. 11. Bales, interview with the author. 12.

The Space Barons: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos

by

Christian Davenport

Published 20 Mar 2018

As a guidebook pointed out: David Goodman, Best Backcountry Skiing in the Northeast (Boston: Appalachian Mountain Club Books, 2010). In modern society: Paul O’Neil, The Epic of Flight, Barnstormers & Speed Kings (New York: Time-Life Books, 1981). “If we die”: John Barbour, “Footprints on the Moon,” Associated Press, 1969. Gene Kranz, the flight director: Nova online, interview with Gene Kranz, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/tothemoon/kranz.html. Musk had always had a bit: Kerry A. Dolan, “How to Raise a Billionaire: An Interview with Elon Musk’s Father, Errol Musk,” Forbes, July 12, 2015. His maternal grandparents: “Tesla and SpaceX: Elon Musk’s Industrial Empire,” Segment Extra, “Elon Musk on His Family History,” 60 Minutes, March 30, 2014.

…

The swashbuckling era of Mercury and Apollo had passed, like poor, lonesome cowboys riding off into the sunset. It was replaced by the solemn rectitude of the parents who spent too much time at the funerals of their offspring, who knew the consequences and were rightfully chastened and scared. During the Apollo 11 mission to the moon, the average age in mission control was just twenty-six. Gene Kranz, the flight director with the flat-top and steely nerves, was thirty-five, the senior statesman, “the old man in the room,” he said. They were young and invincible, full of so many romantic illusions that they didn’t know that the task President Kennedy had given them was impossible. Since then, NASA had continued to pioneer, sending rovers to Mars and robots that scoured the far reaches of the solar system in one amazing feat after another.

…

In mid-2017, Bezos invited several of the surviving Apollo-era astronauts to an air show in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, where he was showing off the New Shepard booster and a mock-up of the crew capsule that would soon take paying tourists to space. It was an extraordinary reunion of the most exclusive of fraternities. There was Buzz Aldrin. And James Lovell, and Frank Borman, both members of the Apollo 8 crew, along with Fred Haise, who had served with Lovell on Apollo 13. There were Walter Cunningham, Apollo 7, and Gene Kranz, NASA’s legendary flight director. One by one, they stepped into Bezos’s spacecraft, crossing the chasm from Apollo to the promise of the Next Giant Leap, even if so many of their brethren had passed away and would never see it come to fruition. They stretched out in the reclined seats next to the giant windows of this newly designed crew capsule, and ran their fingers over the handrails there to provide stability during those minutes of weightlessness.

Start-Up Nation: The Story of Israel's Economic Miracle

by

Dan Senor

and

Saul Singer

Published 3 Nov 2009

Conscription, serving in the reserves, living under threat, and even being technologically savvy are not enough. What, then, are the other ingredients? “I’ll give you an analogy from an entirely different perspective,” Tal Riesenfeld told us matter-of-factly. “If you want to know how we teach improvisation, just look at Apollo. What Gene Kranz did at NASA—which American historians hold up as model leadership—is an example of what’s expected from many Israeli commanders in the battlefield.” His response to our question about Israeli innovation seemed completely out of context, but he was speaking from experience. During his second year at Harvard Business School, Riesenfeld launched a start-up with one of his fellow Israeli commandos.

…

It was less than a year after Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin had stepped off Apollo 11. NASA was riding high. But when Apollo 13 was two days into its mission, traveling two thousand miles per hour, one of its primary oxygen tanks exploded. This led astronaut John Swigert to utter what has by now become a famous line: “Houston, we’ve had a problem.” The flight director, Gene Kranz, was in charge of managing the mission—and the crisis—from the Johnson Space Center in Houston. He was immediately presented with rapidly worsening readouts. First he was informed that the crew had enough oxygen for eighteen minutes; a moment later that was revised to seven minutes; then it became four minutes.

…

Roberto, Amy C. Edmondson, and Richard M. J. Bohmer, “Columbia’s Final Mission,” Harvard Business School Case Study, 2006; Charles Murray and Catherine Bly Cox, Apollo (Birkittsville, Md.: South Mountain Books, 2004); Jim Lovell and Jeffrey Kluger, Apollo 13 (New York: Mariner Books, 2006); and Gene Kranz, Failure Is Not an Option: Mission Control from Mercury to Apollo 13 and Beyond (New York: Berkley, 2009). 10. Michael Useem, The Leadership Moment: Nine True Stories of Triumph and Disaster and Their Lessons for Us All (New York: Three Rivers, 1998), p. 81. 11. Roberta Wohlstetter quoted in Michael A.

The Race: The Complete True Story of How America Beat Russia to the Moon

by

James Schefter

Published 2 Jan 2000

He soon had a score of degreed engineers reporting to him as they ran herd on the aerospace companies hired to build Mercury’s hardware. There were others scattered here and there through the new Space Task Group who became important men in the space race—Glynn Lunney, John Hodge, Bill Bland, Aleck Bond among them. And there were some yet to be hired. Gene Kranz was not there on the ground floor but quickly found his way to Langley. Guy Thibodeaux was still needed on other work but would be swept into the Space Task Group when his growing expertise in rocket propulsion was needed. Walt Williams remained out in the California desert, where Muroc Dry Lake was now Edwards Air Force Base and the world’s hottest airplanes traced vaporous contrails over the white desert floor.

…

The average age of the 568 people in his Flight Control Division was just thirty. On many missions, that average dropped to twenty-seven or twenty-eight for the men inside mission control. Kraft now had three teams of flight controllers to work eight-hour shifts during long missions. The other two were headed by Gene Kranz, thirty-two, and John Hodge, thirty-four. Kraft liked to have the young guys in mission control. “They’re more eager and they get caught up in what they’re doing,” Kraft said. “At Langley everyone left at 4:30. You won’t find that around here. And sometimes we have to chase them out of here and tell them to go home.”

…

It started out perfectly, an Atlas rocket putting the Agena target vehicle into orbit on March 16, then Gemini VIII following about ninety minutes later. It was the first manned space mission without Chris Kraft as a flight director. He’d moved on to planning Apollo operations; the first manned Apollo flight was only a year away. Two flight control teams, headed by John Hodge and Gene Kranz, were ready to take over. They planned to work twelve-hour shifts during Gemini VIII. New teams headed by Cliff Charlesworth and Glynn Lunney were in training and would be ready for later Gemini missions. Kraft was technically out of the loop, but all the teams ultimately worked for him and he had a habit of showing up in mission control whenever anything exciting was happening.

Building Habitats on the Moon: Engineering Approaches to Lunar Settlements

by

Haym Benaroya

Published 12 Jan 2018

Westphal, then only 30 years old, who later became a professor at Caltech, Director of the Palomar Observatory in the 1990s, a recipient of MacArthur Foundation genius grant and lead investigator for the development of the Hubble Space Telescope’s Wide-Field and Planetary Camera. Six months after completing the course, I met Werner von Braun and was invited to attend the First National Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Space. But it was the rescue of the Apollo 13 crew in the spring of 1970 that gave me the ‘compass heading’ for my path. Flight Director Gene Kranz and his flight control team had to deal with the initial hours of an unfolding catastrophe, essentially a race against time to keep the spacecraft (and the crew) alive. Kranz and his team (1) Set the constraints for the consumption of spacecraft consumables (oxygen, electricity and water); (2) Made the decision to use the Lunar Module as a lifeboat; (3) Created a jury-rigged mechanism to reverse dangerously increasing levels of carbon dioxide using cardboard, paper, scissors and duct tape from available materials; (4) Controlled the three course-correction burns during the trans-Earth trajectory; as well as (5) Created in-space power-up procedures for an essentially dead Command Module (never before done or even simulated) that allowed the astronauts to jump into it at the last second, jettison the Lunar Module and parachute safely back to Earth.

…

The ethos of keeping your cool, not freaking out, getting a grasp of the situation no matter how dire, then thinking it through, doing the math, prioritizing and sequencing the problems, then focusing on one problem at a time, always mindful the solution to one problem can inadvertently create other ones, is essentially the same philosophy embodied in the character of Mark Watney in The Martian. The Apollo 13 team, including the astronauts, had to deal with truth as it was – in all of its ugly and complex manifestations – not what they wanted it to be. For their truly heroic efforts, Gene Kranz, his team and the crew subsequently received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. I followed the emerging crises of Apollo 13 in real time completely transfixed by the tremendous competence, tenacity and creativity of Kranz and his team. I remember consciously thinking that was one of the things I wanted to do in my life.

…

Twelve years later, through a series of seemingly random events and more than a little luck; after years of college, graduate school, the military, medical school, a surgical internship and residency training in Aerospace Medicine; as well as months of intense study covering every aspect of spaceflight operations including guidance, navigation, communications, propulsion, flight dynamics, Shuttle systems and subsystems training including Environmental Control & Life Support; as well as successful completion of scores of intense Mission Control ascent, orbit and entry simulations, I was granted admission to one of the most exclusive clubs in the world – Gene Kranz’s Mission Control Flight Control Team. It was, and still is, one of the proudest accomplishments of my life. Gerard K. O’Neill, father of the modern space colony, author of The High Frontier and tireless proponent of the ‘humanization of space’, is another very significant professional influence, as is the work of Dr.

The Last Man on the Moon: Astronaut Eugene Cernan and America's Race in Space

by

Eugene Cernan

and

Donald A. Davis

Published 1 Jan 1998

The Titan, once a silent, sleeping giant, was now fully awake and flexing its muscles, ready to romp toward an incredible 430,000 pounds of thrust and haul ass out of there like a favorite leaving the gate at the Kentucky Derby. The initial slow ascent turned into a sudden vault of speed, and we were away. The sides of the rocket were washed by a glistening sun as the Titan pushed off, gaining altitude and speed by the instant. In Mission Control, Flight Director Gene Kranz listened carefully as his controllers reported, station by station. “Good. Excellent. Everything is green and go!” By then, the rocket was galloping out across the Atlantic and the forces of gravity stacked like bricks on my chest. My heart was beating a mile a minute and I gritted my teeth. A glance showed that Tom was gritting his, too.

…

We asked for a rest period, waved farewell to the gator, pulled a safe distance away and dropped off to sleep like a couple of babes. While we dozed for ten hours, the people running the show stayed busy analyzing what was happening and keeping critics at bay. There was not a hint of criticism anywhere within the program. Gene Kranz told the press it was not unusual for astronauts to get tired early in a busy flight, and our astronaut brethren ringed us with solid support, shooting withering looks at any doubters. If Stafford and Cernan say they are tired, then they’re probably close to collapse, the astronauts said. Test pilots don’t do something like this without a damned good reason, and you back up your pilots.

…

The semi-comic air that had gripped everyone with the saga of the angry alligator gave way to serious consideration that Gemini 9 might be headed for failure. Fatigue was no laughing matter. MISSION CONTROL SPENT HOURS wrapped in meetings to decide if the spacewalk should be canceled because of our physical state. “Obviously, if the crew is not ready, we would not do the EVA,” said Gene Kranz. The doctors said part of the problem was that our waking and working hours had been completely turned around. The current situation showed the spacecraft low on fuel, the docking with the Blob was impossible , a strenuous spacewalk lay ahead, and we were already exhausted. After only one day in orbit.

Challenger: A True Story of Heroism and Disaster on the Edge of Space

by

Adam Higginbotham

Published 14 May 2024

For Isla CAST OF CHARACTERS NASA Headquarters, Washington, DC Robert Frosch Administrator: head of NASA, 1977–1981 James Beggs Administrator: head of NASA, 1981–1986 William Graham Deputy Administrator Jesse Moore Associate Administrator for Spaceflight: overall head of the Space Shuttle program, 1984–1986 Mike Weeks Deputy Associate Administrator for Spaceflight, Technical Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas Christopher Kraft, Jr. Center Director, 1972–1982 George Abbey Director of Flight Operations Gene Kranz Deputy Director of Flight Operations John Young Chief of the Astronaut Office Arnold Aldrich Space Shuttle Program Manager Maxime Faget Director of Engineering and Development Tom Moser Head of Structural Design, 1972–1982 Dorothy “Dottie” Lee Subsystems Manager of Aerothermodynamics Jay Greene Flight Director, Mission Control Jenny Howard Booster Systems Engineer, Mission Control Steve Nesbitt Public Affairs Officer, Johnson Space Center; Chief Commentator, Mission Control, 1986 Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama Wernher von Braun Center Director, 1960–1970 William Lucas Center Director, 1974–1986 George Hardy Deputy Director of Science and Engineering Judson Lovingood Associate Director of Engineering and Propulsion Stanley Reinartz Manager, Shuttle Projects Office Larry Mulloy Project Manager, Space Shuttle solid rocket boosters Kennedy Space Center, Merritt Island, Florida Gene Thomas Launch Director Cecil Houston Resident Manager for the Marshall Space Flight Center Johnny Corlew Quality Assurance Inspector, pad closeout crew Charlie Stevenson Leader of the Ice Team, engineering department Morton Thiokol, Wasatch Division, Utah Jerry Mason General Manager and Senior Vice President Cal Wiggins Deputy General Manager and Vice President Bob Lund Vice President of Engineering Joe Kilminster Vice President of Space Booster Programs Allan McDonald Director of the Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Motor Project Arnie Thompson Supervisor of Structures Design for Solid Rocket Motor Cases Roger Boisjoly Senior Scientist, Structural Mechanics, Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Motor Project Bob Ebeling Manager, Final Assembly, Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Motor Project Astronauts Joe Allen Jim Bagian Guion Bluford Charles Bolden, Jr.

…

On call twenty-four hours a day, Abbey had five young children at home, but rarely saw them: after leaving his office, he often lingered into the small hours among those who manned the consoles at Mission Control, or in the taverns and hotel bars scattered along the two-lane highway specially built to serve the center, NASA Road 1. As part of the team who had successfully brought home the crew of Apollo 13, in 1970 he had been awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. But unlike other, highly visible administration characters like Flight Director Gene Kranz—instantly recognizable by his severe blond flattop and fancy vests—Abbey remained unknown to the general public, a doughy middle-aged functionary in a blazer and khakis. Secretive, inscrutable, and Machiavellian, he combined a prodigious memory with a subtle knack for reading human behavior, a calculated reluctance to commit his instructions to paper, and a gift for gathering intelligence from those around him and using it well: the Thomas Cromwell of the Johnson Space Center.

…

Yet, no one knew if any of the hundreds of brick-like black tiles covering the bottom of Columbia, where temperatures were expected to rise to 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit, had been sheared off by the same forces that had damaged the shielding near the tail. At each of the twice-daily press conferences held in the packed Public Affairs Office auditorium of Building 2 at the Space Center, reporters had pressed Gene Kranz, the Deputy Director of Flight Operations, for details of what he knew so far, and what steps he had taken to find out more; on the second day, he brought out Tom Moser to describe the exhaustive analysis done so far—but admitted that efforts to photograph the bottom of the orbiter using Air Force telescopes had failed.

Of a Fire on the Moon

by

Norman Mailer

Published 2 Jun 2014

“The whole philosophy of power descent monitoring is that when the Pings [PGNCS] have degraded …” or “The bulk of Delta V is to kill his retrograde component.” These were notes Aquarius picked out for himself after a half hour of talking to the Chief of Flight Operations Division, who would help to bring the Lem down to the surface of the moon, a hard green-eyed crew-cut man in his thirties named Gene Kranz who looked and talked like a professional football quarterback. And in fact his problems were not dissimilar. They arrived at the same rate of speed and were as massive. “During the first five minutes of descent,” Kranz said, “the landing will be almost luxurious. But during the last three minutes, he’ll be coming like Whistling Dixie.”

…

At any rate, the checklist, product of months of work and months of preventive detection, was gone through by the astronauts while circling the moon, and after every item was fulfilled correctly, every switch properly thrown, a sneak circuit was still not avoided. In the no-man’s-land of electrical hegemony, sneak circuits resided at the very edge of thought. “If we had been supersmart,” said the Flight Director Gene Kranz on another day, “we could have picked up the possibility.” Collins had said, “The most dangerous items are the ones we’ve overlooked.” Yes, it was not possible to anticipate everything. Not by time, not by cost, not even by space. More than sneak circuits were sitting upon the descent. It was for example impossible to use a real rendezvous radar in the simulator, for how could one maintain a real situation for hours on earth in which two moving vehicles might be anywhere from two feet apart to two thousand miles apart and moving with velocities which varied from inches a second to thousands of miles an hour, no, a project close to the size of the Space Program itself might be necessary to create a real equivalent of rendezvous radar, and yet it was only necessary to make certain that the amount of data coming in by rendezvous radar and landing radar would not overload the Guidance Computer.

…

So each man on that floor knew he could enter a stricken instant, a cauldron of adrenalin, a failure of nerve which could lay a shadow upon all the hours of his life: an order to abort the mission which later proved to be unnecessary, or an injunction to go ahead which resulted in death would have to leave an isolation of the soul. Suicide could be the neighbor at one’s elbow for many a year. No wonder technicians at NASA so often had hands clammy to the touch. Therefore, the man who would be Flight Director during Eagle’s descent to the moon, Gene Kranz, had taken his flight controller’s crew through a series of planning sessions the month before, a field seminar which could well have been termed the Engineering of Emergency Situations, for Flight Control proceeded to trace out the connotations of every alert and every alarm the computer could show.

Chasing the Moon: The People, the Politics, and the Promise That Launched America Into the Space Age

by

Robert Stone

and

Alan Andres

Published 3 Jun 2019

CBS began its marathon in the late morning, with a prologue that featured correspondent Charles Kuralt reading the opening lines of Genesis. At precisely the same moment, in the East Room of the White House, Frank Borman was reading the same lines, for a worship service at which President Nixon and more than 340 diplomats, congressmen, and government leaders were present. In Houston’s Mission Control room, flight director Gene Kranz and his White Team had taken over from the Black Team, headed by Glynn Lunney. At thirty-five, former jet-fighter pilot Kranz was one of the older men in the room. On this day there would be no live-television cameras broadcasting images from the room; however, a small team of NASA cinematographers would be recording the event for history.

…

Not long after Armstrong and Aldrin in the Eagle and Collins in Columbia reported that they had successfully undocked the two spacecraft disappeared into radio silence as their orbits took them around the Moon’s far side. In Houston, those in Mission Control knew that one of three possible scenarios could play out within the next ninety minutes. The lunar module would either crash, abort the landing attempt, or successfully touch down on the lunar surface. Outwardly calm and confident, Gene Kranz addressed the White Team over a private audio channel. “The hopes and the dreams of the entire world are with us. This is our time and our place, and we will remember this day and what we will do here always.” But no matter what happened, he assured them, he would stand by their decisions. Eagle reemerged from the far side of the Moon at a height of only eighteen nautical miles above the surface, just minutes before beginning its powered descent.

…

“Phooey” “Set Earth Priorities,” Florida Today from Cocoa, Florida (July 17, 1969), p. 11A. Sargent Shriver “JFK Dream Comes True,” Florida Today from Cocoa, Florida (July 17, 1969), p. 11A; Richard S. Lewis, Appointment on the Moon (New York: Viking, 1969), p. 504. “Do you think” ACC, interview with Cronkite, “Man on the Moon.” “The hopes and the dreams” Gene Kranz, Failure Is Not an Option: Mission Control from Mercury to Apollo 13 and Beyond (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000), p. 283. Armstrong later said Neil Armstrong, quoted in Apollo 11: Technical Crew Debriefing, July 31, 1969 (Houston: Manned Spacecraft Center, 1969), p. 60. “A symbolic act” Lewis Mumford, “No: ‘A Symbolic Act of War…’ ” NYT (July 21, 1969), p. 6.

Digital Apollo: Human and Machine in Spaceflight

by

David A. Mindell

Published 3 Apr 2008

Flight Director Gene Kranz believed it came from a little extra air pressure caught in the docking tunnel, or perhaps it resulted from the LM’s maneuvers around the CSM.3 Considering they had just come a quarter of a million miles, we can marvel they would even be aware of such a discrepancy, let alone be concerned about it. But the landing site had been precisely placed, and this extra velocity would cause them to miss it by several miles. Armstrong would miss the landmarks he had carefully memorized. Still, everything else was going well. On the ground’s intercom loop, Gene Kranz queried his team: ‘‘Go to continue powered descent?’’

…

The book reports Shepard’s answer: ‘‘The Tom Sawyer grin was never so wide on Alan’s face: ‘You’ll never Know, Ed. You’ll never know.’ ’’46 (None of the recordings, air to ground, or within the LM, or the technical debriefs afterward, recorded such a conversation. Ed Mitchell does not recall it either.) Flight director Gene Kranz, in his memoir Failure Is Not an Option, recalled that Shepard had confided later to Flight Director Gerry Griffin, ‘‘ ‘I had come too far to abandon the Moon. I would have continued the approach even without the radar.’ ’’ Kranz did not doubt that Shepard was serious, but also was sure he would have had to abort, because he would not have known his altitude accurately and, as Kranz noted, ‘‘The fuel budget was just too tight.’’47 Whether Shepard or any other astronaut could have landed without the radar data will never be known, but the systems problem on Apollo 14 once again stressed the interactions between humans and machine, and among the pilots, ground controllers, and engineers.

Failure Is Not an Option: Mission Control From Mercury to Apollo 13 and Beyond

by

Gene Kranz

Published 7 Jan 2000

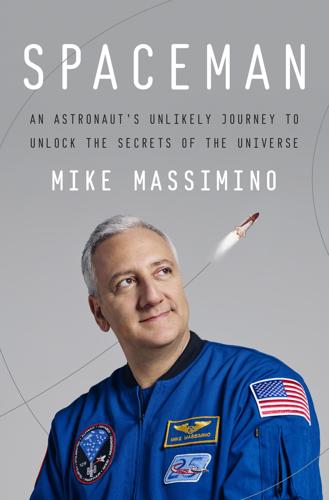

Failure Is Not an Option MISSION CONTROL FROM MERCURY TO APOLLO 13 AND BEYOND GENE KRANZ Simon & Schuster New York London Toronto Sydney Singapore SIMON & SCHUSTER Rockefeller Center 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Visit us on the World Wide Web: http://www.SimonSays.com Copyright © 2000 by Gene Kranz All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Simon & Schuster and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc. ISBN 0-7432-1447-1 With love to my wife, Marta, and our children, Carmen, Lucy, Joan, Mark, Brigid, and Jean Contents 1 | The Four-Inch Flight 2 | "Liftoff; the Clock Is Running" 3 | "God Speed, John Glenn" 4 | The Brotherhood 5 | The Making of a Rocket Man 6 | Gemini—The Twins 7 | White Flight 8 | The Spirit of 76 9 | The Angry Alligator 10 | A Fire on the Pad 11 | Out of the Ashes 12 | The X Mission 13 | The Christmas Story 14 | 1969—The Year of Apollo 15 | SimSup Wins the Final Round 16 | "We Copy You Down, Eagle" 17 | "What the Hell Was That?"

…