George Akerlof

description: an American economist who won the 2001 Nobel Prize in Economics for his work on information asymmetry

158 results

Fixed: Why Personal Finance is Broken and How to Make it Work for Everyone

by John Y. Campbell and Tarun Ramadorai · 25 Jul 2025

-interested businesspeople are just as strongly motivated to supply the mistaken demands of confused customers. This pernicious behavior is what the Nobel Prize–winning economists George Akerlof and Robert Shiller call “phishing for phools.”8 The perversion of capitalism in the personal finance system is familiar in a different context. Until about

…

, Atif Mian, Ludwig Straub, and Amir Sufi, “The saving glut of the rich” (unpublished paper). 36. This is the behavior that Nobel Prize–winning economists George Akerlof and Robert Shiller call “Phishing for Phools” in the title of their 2015 book. 37. Cass Sunstein and the Nobel Prize–winning economist Richard Thaler

…

111 (2021): 2377–2416, highlight this fact. 7. Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, books 1–3, ed. Andrew S. Skinner (Penguin Classics, 2013). 8. George Akerlof and Robert Shiller, Phishing for Phools (Princeton University Press, 2015). 9. These and other examples can be found at “10 evil vintage cigarette ads promising

…

and, 193, 277n32; marketing aimed at, 274n9. See also race Africrypt exchange, 191 age, financial literacy and, 33–35, 34–35 age pyramid, 151, 152 Akerlof, George, 55 algorithmic discrimination, 189, 197–198 Alipay, 184, 293n17 allocation of retirement assets, 165–169, 257–259 AlphaGo Zero program, 43–44 alternative financial products

The Age of Extraction: How Tech Platforms Conquered the Economy and Threaten Our Future Prosperity

by Tim Wu · 4 Nov 2025 · 246pp · 65,143 words

. I suspect many people don’t buy Persian rugs or used cars precisely because they fear being cheated in one way or another. As economist George Akerlof theorized in a famous 1970 paper, that fear of being cheated or even defrauded can itself function to deter transactions, even if the product is

…

Rochet and Jean Tirole, “Platform Competition in Two-Sided Markets,” Journal of the European Academic Association 1, no. 4 (2003). BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 2 George A. Akerlof, “The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 84, no. 3 (1970). BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 3 Mark

…

, 85 vs. users, competing interests between, 45, 52–53, 67–68 aerospace industry, 35 The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (Zuboff), 87 AI. See artificial intelligence Akerlof, George, 16 Alcoa, 28 AlexNet, 93 allegiance to brand, 72, 100–102 Altman, Sam, 6, 94, 142–43, 146, 151 Amazon, 6, 9, 10 AI development

Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism

by George A. Akerlof and Robert J. Shiller · 1 Jan 2009 · 471pp · 97,152 words

HOW HUMAN PSYCHOLOGY DRIVES THE ECONOMY, AND WHY IT MATTERS FOR GLOBAL CAPITALISM With a new preface by the authors GEORGE A. AKERLOF AND ROBERT J. SHILLER Princeton University Press • PRINCETON AND OXFORD George Akerlof is the Daniel E. Koshland Sr. Distinguished Professor of Economics at the University of California at Berkeley; co-director

…

-14592-1 The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows Akerlof, George A., 1940– Animal spirits : how human psychology drives the economy, and why it matters for global capitalism / George A. Akerlof and Robert J. Shiller. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-691-14233-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1

…

sure there is always a connection to economic reality. We both have sons who are emerging scholars and who have offered comments on the book. George Akerlof thanks the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research and the National Science Foundation (grant SES 04-17871) for generous financial support. We also thank Edward Koren

…

–88). 7. Fehr and Gächter (2000). 8. Chen and Hauser (2005). 9. De Quervain et al. (2005). 10. E-mail communication from Ernest Fehr to George Akerlof, November 1, 2008. Fehr also pointed out that—since the dorsal striatum is activated in anticipation of both getting water, if one is thirsty, and

…

-OFF BETWEEN INFLATION AND UNEMPLOYMENT IN THE LONG RUN? 1. Much of this chapter is based on Akerlof’s joint work with William Dickens and George Perry (Akerlof et al. 1996, 2000; Akerlof and Dickens 2007). See also Schultze (1959), Tobin (1972), and Palley (1994). 2. Samuelson (1997 [1948]). 3. Card and

…

on Wage Rigidity and Unemployment: Sweden in the 1990s.” Scandinavian Journal of Economics 105(1): 15–29. Akerlof, George A., 1982. “Labor Contracts as Partial Gift Exchange.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 97(4):543–69. Akerlof, George A., and William T. Dickens. 2007. “Unfinished Business in the Macroeconomics of Low Inflation: A Tribute to

…

George and Bill by Bill and George.” Brookings Papers on Macroeconomics 2:31–48. Akerlof, George A., and Rachel E. Kranton. 2000. “Economics and Identity.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 115(3):715–53. ———. 2002. “Identity and Schooling: Some Lessons for the

…

Economics of Organizations.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 19(1):9–32. ———. 2008. “Economics and Identity.” Unpublished paper, University of California-Berkeley, and Duke University, July. Akerlof, George A., and Paul M. Romer. 1993. “Looting: The Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy for Profit.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2:1–74

…

. Akerlof, George A., and Janet L. Yellen. 1990. “The Fair Wage-Effort Hypothesis and Unemployment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 105(2):255–83. Akerlof, George A., Andrew K. Rose, and Janet L. Yellen. 1988. “Job Switching and Job Satisfaction

…

in the U.S. Labor Market.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2:495–582. Akerlof, George A., William T. Dickens, and George L. Perry. 1996. “The Macroeconomics of Low Inflation.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1:1–59. ———. 2000. “Near-Rational

…

, 164, 166 Agell, Jonas, 183n14 aggregate demand, 89, 173, 185n32 aggregate demand target, 96 aggregate supply, 185n32 agricultural land, 153 AIG. See American International Group Akerlof, George A., 11, 13, 25, 110, 113, 117, 124, 177n1, 181n10,2,5,8,9,13, 183n8, 188n1,2,10,11,14, 189n16,1, 190n8,10

Wait: The Art and Science of Delay

by Frank Partnoy · 15 Jan 2012 · 342pp · 94,762 words

. But what if you are still putting off the decision a month later? Where is the line between good delay and bad delay? The economist George Akerlof was spending a year in India after graduate school, and his good friend and fellow economist Joseph Stiglitz visited him there. (This was decades ago

…

, developed a clever mathematical model to show how procrastination can be in our best interests.17 A second strand of economics, the one originated by George Akerlof,18 laid the groundwork for Piers Steel and dozens of other prominent economists and psychologists who see procrastination as closely tied to impatience. Procrastination has

…

of the books, websites, and self-help courses on the topic, there is no grand unified theory of procrastination.22 The closest we have is George Akerlof. In 1991, twenty-five years after his postgraduate year in India, Akerlof was invited to give a lecture at the 103rd meeting of the American

…

mistaken about the benefits of doing so. Until recently, economists didn’t have a good model that captured the relationship between discount rates and procrastination. George Akerlof got them started, but even he wasn’t aware of some of the research about time inconsistency when he gave his 1991 procrastination talk to

…

finished his essay on procrastination long before the one on the philosophy of language, and before he had completed the book orders.62 So, was George Akerlof really procrastinating, in the most negative sense of the term? I asked him how hard it would have been to send a box from India

…

, the new commission was a controversial move. Sarkozy asked Stiglitz to chair the effort. Stiglitz had come a long way since waiting for his friend George Akerlof to send him a box of clothes from India. In 1979 he won the John Bates Clark Medal, awarded every other year to the top

…

the information available to sellers and buyers. Akerlof’s most famous paper—one of the most frequently cited papers in the history of economics—is George A. Akerlof, “The Market for Lemons: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 84(3, 1970): 488–500. In this paper, Akerlof uses

…

. 17. Carolyn Fischer, “Read This Paper Later: Procrastination with Time-Consistent Preferences,” Discussion Paper 99-19 (Resources for the Future, April 1999), p. 28. 18. George A. Akerlof, “Procrastination and Obedience,” American Economic Review 81(2, 1991): 1–19. 19. See Steel, The Procrastination Equation, p. 66. 20. See George Loewenstein, Scott

…

and Richard H. Thaler, “Anomalies: Intertemporal Choice,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 3(1989): 181–193. 32. George Ainslie, Picoeconomics (Cambridge University Press, 1992). 33. George A. Akerlof, “Behavioral Microeconomics and Macroeconomic Behavior,” Nobel Prize Lecture, December 8, 2001. 34. James E. Mazur, “Tests of an Equivalence Rule for Fixed and Variable Reinforcer

…

, “Market Madness? The Case of Mad Money,” Management Science 58(2, 2012): 351–364. 2. See Robert J. Shiller, Irrational Exuberance (Crown Business, 2006); George A. Akerlof and Robert J. Shiller, Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism (Princeton University Press, 2010); Jason Zweig

…

medulla, 69 Adrenaline, 69, 105 Advertising, 50, 55 fast food, 59–60 subliminal, 51, 52, 59 Affection, brain and, 124 Ainslie, George, 157, 158, 166 Akerlof, George, 147–148, 152, 153, 154–155, 233 procrastination and, 151, 158, 170–171 short-term decisions and, 155 Alda, Alan, 107 Algorithms, 21, 31, 44

EuroTragedy: A Drama in Nine Acts

by Ashoka Mody · 7 May 2018

left the IMF that I write a book explaining the euro crisis. He set me off on an amazing journey. My greatest debt is to George Akerlof. He understood what I wanted to write long before I did. Through many lunches over five years, he gave me an opportunity to talk about

…

in early 1991 concluded, “One of the worst and sharpest depressions in European history had begun.”77 Two of the authors of that analysis were George Akerlof (who later received the Nobel Prize for Economics) and Janet Yellen (who became chairman of the Fed). They explained the unfolding disaster. At the unreasonably

…

set by the 1:1 conversion of the Ostmark to the D-mark continued to undermine the competitiveness of East German firms, exactly as Professors George Akerlof and Janet Yellen had predicted (see c hapter 2). Hans-Werner Sinn, President of the Munich-based Ifo Institute for Economic Research and a prominent

…

government transfers begin spending more, which creates additional incomes for others, thus activating a “multiplier effect” through a steadily widening circle of consumers and investors. George Akerlof and Robert Shiller, both recipients of the Nobel Prize for Economics, have noted that the mere knowledge that others have increased their spending creates a

…

virtues of fiscal tightening had become integral to the eurozone’s culture. Indeed, austerity had become part of the eurozone’s identity. Economics Nobel laureate George Akerlof and Duke University economist Rachel Kranton explain that in a search for internal coherence and peer esteem, members of a group create rules or norms

…

and Crisis, edited by Brian Murphy, Mary O’Rourke, and Noel Whelan, chapter 1. Kildare: Merrion. Kindle edition. Akerlof, George. 2007. “The Missing Motivation in Macroeconomics.” American Economic Review 97, no. 1: 5–36. Akerlof, George, and Rachel Kranton. 2010. Identity Economics: How Our Identities Shape Our Work, Wages, and Well-Being. Princeton: Princeton

…

University Press. Akerlof, George A., Andrew K. Rose, Janet L. Yellen, and Helga Hessenius. 1991. “East Germany In From the Cold: The Economic Aftermath of Currency Union.” Brookings Papers

…

on Economic Activity 1: 1–87. Akerlof, George, and Robert Shiller. 2009. Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Akerlof, Robert

…

Treaty of Paris, 27 support for EDC Treaty, 28 Aeschimann, Eric, 87 Africa, long-term decline in, 395 Ahern, Bertie, 179 AIB bank (Ireland), 271 Akerlof, George, 80–81, 147, 287, 290 Akerlof, Robert, 51–52 Aliber, Robert, 179–180, 182 Allen-Mills, Tony, 81 Allied Irish Bank (AIB), 180, 182, 227

Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown

by Philip Mirowski · 24 Jun 2013 · 662pp · 180,546 words

through the eyes of others—neoliberal prescriptions par excellence (see Benabou and Tirole). Another economist we shall encounter later in our survey of crisis theories, George Akerlof, purported to concoct a neoclassical theory of identity by stuffing the utility function with even more arbitrary variables. This version of the “individual” seeks to

…

Chicago School of neoclassical economics.” Far from being the conventional generic blanket disparagement of “freshwater economics” (such as that spread by Paul Krugman, Brad DeLong, George Akerlof, and others), this points to the fact that Chicago was the prime initial incubator for modern finance theory, which has indeed provided direct intellectual inspiration

…

in with op-eds essentially blaming the entire crisis on native cognitive weaknesses of market participants.37 This line became entrenched with the appearance of George Akerlof and Robert Shiller’s Animal Spirits: displaying an utter contempt for the history of economic thought, they “reduced” the message of Keynes’s General Theory

…

be hard to find. The website also has a set of pages devoted to economics; under the rubric “Meet the Mavericks” it profiled Paul Samuelson, George Akerlof, Joseph Stiglitz, and Herman Daly. Kalle Lasn Associates has also published an anti-textbook entitled Meme Wars: The Creative Destruction of Neoclassical Economics which contains

…

contributions by George Akerlof and Joseph Stiglitz. At least the graphics were radical. Similar ideas were promoted in the curiously titled Occupy Handbook, which included chapters by Raghuram Rajan

…

Fed?” SSRN working paper, 2011. Ailon, Galit. “The Discursive Management of Financial Risk Scandals,” Qualitative Sociology 35 (2012): 251–70. Akerlof, George, and Rachel Kranton. Identity Economics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010). Akerlof, George, and Paul Romer. “Looting: The Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy for Profit,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity no. 2 (1993): 1

…

–73. Akerlof, George, and Robert Shiller. Animal Spirits (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009). Akerlof, George, and Robert Shiller. “Disputations: Our New Theory of Macroeconomics,” New Republic (2009), www.tnr.com/article/books-and-arts/disputations

…

-our-new-theory-macroeconomics. Akerlof, George, and Joseph Stiglitz. “Let a Hundred Theories Bloom” (2009), www.project-synciate.org. Alterman, Eric. “The Professors, the Press, the Think Tanks—and Their Problems,”

…

Association), AEI (American Enterprise Institute) “After the Crash of 2008” (Prasch), The Age of Uncertainty (PBS series) Agnotology, defined Agriculture, Department of AIG Financial Products Akerlof, George Allais, Maurice AlphaSimplex American Economic Review American Economics Association (AEA) American Enterprise Institute (AEI) American Finance Association American Institute of Certified Public Accountants American Majority

How Markets Fail: The Logic of Economic Calamities

by John Cassidy · 10 Nov 2009 · 545pp · 137,789 words

final concert before paying fans; across the water in Oakland, Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton were founding the Black Panther Party. In nearby Berkeley, George Akerlof, a twenty-six-year-old graduate of MIT’s prestigious Ph.D. program in economics, was starting his teaching career. From early childhood, Akerlof had

…

’t know very much and are, therefore, susceptible to peer pressure and other inchoate factors such as psychology. As every economics major knows, and as George Akerlof and Robert Shiller have recently reminded us, Keynes said that “animal spirits,” or the “spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction,” play an important role

…

administration, and published in The New York Times. The reason banks had been so reluctant to lend to the poor and underprivileged goes back to George Akerlof’s work on “lemons” in the secondhand car market. When the owner of a used car puts it up for sale, he signals to potential

…

,” Science 162 (1968): 1244. 150 “Game theorists get . . .”: Binmore, Game Theory, 67. 12. HIDDEN INFORMATION AND THE MARKET FOR LEMONS 151 “I belonged to . . .”: From George Akerlof’s Nobel autobiography, available at http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/laureates/2001/akerlof-autobio.html. 152 “a major reason as to why

…

Market for Lemons’: A Personal and Interpretive Essay,” available at http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/articles/akerlof/index.html. 153 “[M]ost cars traded . . .”: George Akerlof, “The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 84 (1970): 489. 154 “was potentially an issue . . .”: Akerlof, “Writing ‘The

…

) Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) Advanta Bank Corporation Affluent Society, The (Galbraith) Afghanistan War African Americans Age of Turbulence, The, (Greenspan) Air Force, U.S. Akerlof, George Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Alchian, Armen Alcoa, Inc. Allen, Frederick Lewis Allen, Linda Allende, Salvador Al Qaeda Alt-A bonds Alternative Mortgage Transaction Parity Act (1982

Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events

by Robert J. Shiller · 14 Oct 2019 · 611pp · 130,419 words

of a train of thought that I have been developing over much of my life. It draws on work that I and my colleagues, notably George Akerlof, have done over decades,13 culminating in my presidential address, “Narrative Economics,” before the American Economic Association in 2017 and my Marshall Lectures at Cambridge

…

way, often with modifications, into this book. This book is strongly influenced by two books I wrote with George Akerlof, Animal Spirits (2009) and Phishing for Phools (2015). Another strong influence is the book George Akerlof wrote with Rachel Kranton, Identity Economics (2011). Narratives play a role in all these books. Working with George

…

want to survive in a highly competitive business where others use book jackets have had no choice, for the book jacket is part of what George Akerlof and I called a phishing equilibrium. In a competitive market in which competitors manipulate customers, and in which profit margins are competed away to normal

…

-driven contagion is “the news”: the harvest of new information that news publishers hope will grab people’s attention on a given day. “Phools,” as George Akerlof and I call them, who do not think about the marketing efforts, are apt to think that events exogenously give us the news by jumping

…

investor irrationality expected by other investors. In our 2009 book Animal Spirits, which was in many ways an expansion and elaboration of Keynes’s ideas, George Akerlof and I used the beauty contest metaphor to construct a theory of the emotional foundation of business fluctuations in general. The beauty contest metaphor also

…

primitive brain system more connected to palpable emotions has its own heuristic for assessing risk.27 In joint work with William Goetzmann and Dasol Kim, George Akerlof and I examined data from a questionnaire survey of investors and high-income Americans since 1989. We found that people have exaggerated assessments of the

…

depression. In ProQuest News & Newspapers, the peak mention occurred in the Great Depression of the 1930s. The fair wage-effort hypothesis, as presented by George A. Akerlof and Janet L. Yellen (1990), asserts that workers are inclined to slow down their work in revenge if they feel that they are not being

…

. In my view, they are interesting because they describe how bubbles or depressions can start from purely random causes, even if people are fairly sensible. George A. Akerlof and Janet L. Yellen coined the term “near-rational” in 1985, and I wish that term had caught on more, that it had gone

…

Macroeconomic Models: A Critical Review” (1978). I continued with “Stock Prices and Social Dynamics” (1984); Irrational Exuberance (first edition, 2000); and two books coauthored with George Akerlof, Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism (2009), and Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and

…

. 2013. Uncharted: Big Data as a Lens on Human Culture. New York: Riverhead Books, Penguin Group. Akerlof, George A. 2007. “The Missing Motivation in Macroeconomics” (AEA Presidential Address). American Economic Review 97(1):3–36. Akerlof, George A., and Rachel Kranton. 2011. Identity Economics: How Our Identities Shape Our Work, Wages, and Well-Being

…

. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Akerlof, George A., and Robert J. Shiller. 2009. Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

…

Press. ________. 2015. Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Akerlof, George A., and Janet L. Yellen. 1985. “A Near-Rational Model of the Business Cycle, with Wage and Price Inertia.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 100(1

…

homeownership, 219–20; online searching of, x; phrase American Dream in, 154 affect heuristic, 67, 233 Aiden, Erez, 24 AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome), 24 Akerlof, George, xviii, 61, 64, 67, 250, 300, 301n13 Aldrich-Vreeland Act, 117 Alexa, of Amazon Echo, 8, 207 Alibaba’s Tmall Genie, 207 Alice, Yandex, 207

The Best Way to Rob a Bank Is to Own One: How Corporate Executives and Politicians Looted the S&L Industry

by William K. Black · 31 Mar 2005 · 432pp · 127,985 words

economists, but I am not dismissive of economics. Indeed, I write in large part to help build a new economic theory of fraud arising from George Akerlof’s classic theory of lemons markets (1970) and Henry Pontell’s work on “systems capacity” limitations in regulation that may increase the risk of waves

…

to be cynical. James Pierce gave me the opportunity of a lifetime when he asked me to serve as his deputy and introduced me to George Akerlof. Both of you have been leading influences on my research, and your support has been critical. Kitty Calavita, Gil Geis, Paul Jesilow, and Henry Pontell

…

on family law, was an inspiration and someone I could bounce ideas off. Travis Hale and Debra Moore gave me editing assistance. Henry Pontell and George Akerlof served as outside reviewers for the book, and their comments, along with those of Ed Kane, were of great use to me in improving the

…

Act of 1981; law that reduced marginal income tax rates and boosted tax shelters. 1986 TAX REFORM ACT. Law that ended many abusive tax shelters. AKERLOF, GEORGE. Nobel prize-winning economist. AMBERG, RUTH. Bank Board counsel and my aide on FSLIC recap. AMERICAN SAVINGS. Largest S&L, victimized by fraud. ANDERSON, JACK

…

Ring. 1990. The Big Fix: Inside the S&L Scandal, New York: John Wiley & Sons. Akerlof, George. 1970. “The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality, Uncertainty, and the Market Mechanism.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 84 (3):488–500. Akerlof, George, and Paul M. Romer. 1993. “Looting: The Economic Underworld of Bankruptcy for Profit.” Brookings Papers on

…

, 96, 107, 132, 134, 187, 189, 225, 248, 263, 285n7, 287nn14,15, 288n15 Adams, Jim Ring, 17 adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM), 7, 30–31, 281n6 Akerlof, George, xvi, 248, 303n2 Akin, Gump, Strauss, Hauer & Feld (aka Akin, Gump), 65–66, 96, 270–274 Amberg, Ruth, 117, 132 Ambition and the Power, The

The Inner Lives of Markets: How People Shape Them—And They Shape Us

by Tim Sullivan · 6 Jun 2016 · 252pp · 73,131 words

. If even those at the vanguard of tech commerce weren’t shopping online, what hope was there that everyone else ever would? Kicking the Tires George Akerlof never set out to create the intellectual framework that helped nurture the e-commerce explosion or transform the way economists devised their theories. In the

…

her wares than the buyer does, the market is prone to collapse.) And all this can be traced back, in some small way, to young George Akerlof choosing to sit in on a topology class his first year at Harvard. Adverse Selection on eBay Despite his early doubts, Jeff Skoll did ultimately

…

of genuine Tiffany and the buyers in search of them is to prove that they’re not just full of empty words. Around the time George Akerlof had finally gotten someone in the academic community to take “The Market for Lemons” seriously, Michael Spence was at the early stages of his PhD

…

classic Economics text, even though the latter is fifty years older.11) Tirole’s Nobel is emblematic of the postwar trend in economics—begun by George Akerlof’s market for lemons paper and continued by the many applied theorists that followed—toward tailoring models to circumstance. As a result, it’s hard

…

. The platform manager makes customer feedback possible, and in theory, the wisdom of crowds takes care of the rest, solving the asymmetric information problem that George Akerlof identified as the enemy of market function back in 1970. This has led to all sorts of match-making platforms for goods or services where

…

we’re old-fashioned. We’ve also experienced market frictions of a more mundane variety. In writing this book we went to Washington to interview George Akerlof of market-for-lemons fame. As a bit of add-on market research, one of us, Ray, decided to rent an apartment for the night

…

dirty (if invisible) fingers in all the right places to get the market to work just right, much more of the economy would look like George Akerlof’s used car market. Free-market extremists take any evidence of active design as a violation of market logic per se, a view that’s

…

thank the following people who read the manuscript, or parts of it, or who graciously agreed to talk with us about ideas in the book: George Akerlof, Kenneth Arrow, Pierre Azoulay, Seth Dicthick, Frank Dobbin, Ben Edelman, Teppo Felin, Ronald Findlay, Todd Fitch, Margo Beth Fleming, Walter Frick, Joshua Gans, Ed Glaeser

…

has traditionally been more the domain of sociologists than economists, and one that we will not delve into in any detail in this book. 5. George Akerlof, “The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 84, no. 3 (1970): 488–500. 6. In a roundabout way

…

–55, 57, 59 advertising, as money burning, 70–71 Super Bowl advertising, 70–71 AdWords, 14, 101 Airbnb, 3, 6, 50, 109, 125, 170–172 Akerlof, George, 43–51, 58–59, 64, 112 Alaskoil experiment, 55–57, 58–59 algebraic topology, 44–45 Amazon, 2, 3, 16, 50, 51, 52, 59, 74

Finance and the Good Society

by Robert J. Shiller · 1 Jan 2012 · 288pp · 16,556 words

Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception

by George A. Akerlof, Robert J. Shiller and Stanley B Resor Professor Of Economics Robert J Shiller · 21 Sep 2015 · 274pp · 93,758 words

Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics

by Richard H. Thaler · 10 May 2015 · 500pp · 145,005 words

Fed Up: An Insider's Take on Why the Federal Reserve Is Bad for America

by Danielle Dimartino Booth · 14 Feb 2017 · 479pp · 113,510 words

Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making for an Unknowable Future

by Mervyn King and John Kay · 5 Mar 2020 · 807pp · 154,435 words

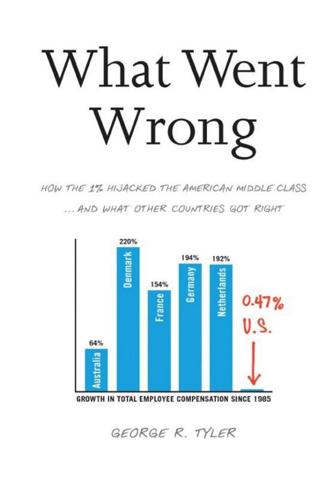

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by George R. Tyler · 15 Jul 2013 · 772pp · 203,182 words

Big Data and the Welfare State: How the Information Revolution Threatens Social Solidarity

by Torben Iversen and Philipp Rehm · 18 May 2022

Culture and Prosperity: The Truth About Markets - Why Some Nations Are Rich but Most Remain Poor

by John Kay · 24 May 2004 · 436pp · 76 words

The Undercover Economist: Exposing Why the Rich Are Rich, the Poor Are Poor, and Why You Can Never Buy a Decent Used Car

by Tim Harford · 15 Mar 2006 · 389pp · 98,487 words

The Future of Capitalism: Facing the New Anxieties

by Paul Collier · 4 Dec 2018 · 310pp · 85,995 words

The Irrational Economist: Making Decisions in a Dangerous World

by Erwann Michel-Kerjan and Paul Slovic · 5 Jan 2010 · 411pp · 108,119 words

Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can't Explain the Modern World

by Deirdre N. McCloskey · 15 Nov 2011 · 1,205pp · 308,891 words

Termites of the State: Why Complexity Leads to Inequality

by Vito Tanzi · 28 Dec 2017

Sickening: How Big Pharma Broke American Health Care and How We Can Repair It

by John Abramson · 15 Dec 2022 · 362pp · 97,473 words

The Death of Money: The Coming Collapse of the International Monetary System

by James Rickards · 7 Apr 2014 · 466pp · 127,728 words

The Euro: How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe

by Joseph E. Stiglitz and Alex Hyde-White · 24 Oct 2016 · 515pp · 142,354 words

The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 10 Jun 2012 · 580pp · 168,476 words

Cogs and Monsters: What Economics Is, and What It Should Be

by Diane Coyle · 11 Oct 2021 · 305pp · 75,697 words

The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail-But Some Don't

by Nate Silver · 31 Aug 2012 · 829pp · 186,976 words

To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth About Moving Others

by Daniel H. Pink · 1 Dec 2012 · 243pp · 61,237 words

The Bankers' New Clothes: What's Wrong With Banking and What to Do About It

by Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig · 15 Feb 2013 · 726pp · 172,988 words

Boom and Bust: A Global History of Financial Bubbles

by William Quinn and John D. Turner · 5 Aug 2020 · 297pp · 108,353 words

Basic Income: A Radical Proposal for a Free Society and a Sane Economy

by Philippe van Parijs and Yannick Vanderborght · 20 Mar 2017

People, Power, and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 22 Apr 2019 · 462pp · 129,022 words

What's Wrong With Economics: A Primer for the Perplexed

by Robert Skidelsky · 3 Mar 2020 · 290pp · 76,216 words

Economics Rules: The Rights and Wrongs of the Dismal Science

by Dani Rodrik · 12 Oct 2015 · 226pp · 59,080 words

Adam Smith: Father of Economics

by Jesse Norman · 30 Jun 2018

A Little History of Economics

by Niall Kishtainy · 15 Jan 2017 · 272pp · 83,798 words

Competition Overdose: How Free Market Mythology Transformed Us From Citizen Kings to Market Servants

by Maurice E. Stucke and Ariel Ezrachi · 14 May 2020 · 511pp · 132,682 words

Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 11 Apr 2005 · 339pp · 95,988 words

Small Wars, Big Data: The Information Revolution in Modern Conflict

by Eli Berman, Joseph H. Felter, Jacob N. Shapiro and Vestal Mcintyre · 12 May 2018 · 517pp · 147,591 words

Machine, Platform, Crowd: Harnessing Our Digital Future

by Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson · 26 Jun 2017 · 472pp · 117,093 words

WTF?: What's the Future and Why It's Up to Us

by Tim O'Reilly · 9 Oct 2017 · 561pp · 157,589 words

Exodus: How Migration Is Changing Our World

by Paul Collier · 30 Sep 2013 · 303pp · 83,564 words

Licence to be Bad

by Jonathan Aldred · 5 Jun 2019 · 453pp · 111,010 words

Reinventing the Bazaar: A Natural History of Markets

by John McMillan · 1 Jan 2002 · 350pp · 103,988 words

The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature

by Steven Pinker · 1 Jan 2002 · 901pp · 234,905 words

A Pelican Introduction Economics: A User's Guide

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 May 2014 · 385pp · 111,807 words

Animal Spirits: The American Pursuit of Vitality From Camp Meeting to Wall Street

by Jackson Lears

The Case Against Education: Why the Education System Is a Waste of Time and Money

by Bryan Caplan · 16 Jan 2018 · 636pp · 140,406 words

The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall Street

by Justin Fox · 29 May 2009 · 461pp · 128,421 words

When the Money Runs Out: The End of Western Affluence

by Stephen D. King · 17 Jun 2013 · 324pp · 90,253 words

Not Working: Where Have All the Good Jobs Gone?

by David G. Blanchflower · 12 Apr 2021 · 566pp · 160,453 words

13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown

by Simon Johnson and James Kwak · 29 Mar 2010 · 430pp · 109,064 words

Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science (Fully Revised and Updated)

by Charles Wheelan · 18 Apr 2010 · 386pp · 122,595 words

Straight Talk on Trade: Ideas for a Sane World Economy

by Dani Rodrik · 8 Oct 2017 · 322pp · 87,181 words

Other People's Money: Masters of the Universe or Servants of the People?

by John Kay · 2 Sep 2015 · 478pp · 126,416 words

Them And Us: Politics, Greed And Inequality - Why We Need A Fair Society

by Will Hutton · 30 Sep 2010 · 543pp · 147,357 words

Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning About a Highly Connected World

by David Easley and Jon Kleinberg · 15 Nov 2010 · 1,535pp · 337,071 words

The Social Animal: The Hidden Sources of Love, Character, and Achievement

by David Brooks · 8 Mar 2011 · 487pp · 151,810 words

Willful: How We Choose What We Do

by Richard Robb · 12 Nov 2019 · 202pp · 58,823 words

The Long Good Buy: Analysing Cycles in Markets

by Peter Oppenheimer · 3 May 2020 · 333pp · 76,990 words

Economists and the Powerful

by Norbert Haring, Norbert H. Ring and Niall Douglas · 30 Sep 2012 · 261pp · 103,244 words

The Unbanking of America: How the New Middle Class Survives

by Lisa Servon · 10 Jan 2017 · 279pp · 76,796 words

State-Building: Governance and World Order in the 21st Century

by Francis Fukuyama · 7 Apr 2004

Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing

by Josh Ryan-Collins, Toby Lloyd and Laurie Macfarlane · 28 Feb 2017 · 346pp · 90,371 words

I.O.U.: Why Everyone Owes Everyone and No One Can Pay

by John Lanchester · 14 Dec 2009 · 322pp · 77,341 words

Radical Markets: Uprooting Capitalism and Democracy for a Just Society

by Eric Posner and E. Weyl · 14 May 2018 · 463pp · 105,197 words

Limitless: The Federal Reserve Takes on a New Age of Crisis

by Jeanna Smialek · 27 Feb 2023 · 601pp · 135,202 words

The Economists' Hour: How the False Prophets of Free Markets Fractured Our Society

by Binyamin Appelbaum · 4 Sep 2019 · 614pp · 174,226 words

The Irrational Bundle

by Dan Ariely · 3 Apr 2013 · 898pp · 266,274 words

Cheap: The High Cost of Discount Culture

by Ellen Ruppel Shell · 2 Jul 2009 · 387pp · 110,820 words

Growth: A Reckoning

by Daniel Susskind · 16 Apr 2024 · 358pp · 109,930 words

Makers and Takers: The Rise of Finance and the Fall of American Business

by Rana Foroohar · 16 May 2016 · 515pp · 132,295 words

The Middleman Economy: How Brokers, Agents, Dealers, and Everyday Matchmakers Create Value and Profit

by Marina Krakovsky · 14 Sep 2015 · 270pp · 79,180 words

Good Economics for Hard Times: Better Answers to Our Biggest Problems

by Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo · 12 Nov 2019 · 470pp · 148,730 words

In FED We Trust: Ben Bernanke's War on the Great Panic

by David Wessel · 3 Aug 2009 · 350pp · 109,220 words

Wall Street: How It Works And for Whom

by Doug Henwood · 30 Aug 1998 · 586pp · 159,901 words

Reinventing Capitalism in the Age of Big Data

by Viktor Mayer-Schönberger and Thomas Ramge · 27 Feb 2018 · 267pp · 72,552 words

Losing Control: The Emerging Threats to Western Prosperity

by Stephen D. King · 14 Jun 2010 · 561pp · 87,892 words

How I Became a Quant: Insights From 25 of Wall Street's Elite

by Richard R. Lindsey and Barry Schachter · 30 Jun 2007

Who Owns the Future?

by Jaron Lanier · 6 May 2013 · 510pp · 120,048 words

Expected Returns: An Investor's Guide to Harvesting Market Rewards

by Antti Ilmanen · 4 Apr 2011 · 1,088pp · 228,743 words

Markets, State, and People: Economics for Public Policy

by Diane Coyle · 14 Jan 2020 · 384pp · 108,414 words

Delete: The Virtue of Forgetting in the Digital Age

by Viktor Mayer-Schönberger · 1 Jan 2009 · 263pp · 75,610 words

The Alchemists: Three Central Bankers and a World on Fire

by Neil Irwin · 4 Apr 2013 · 597pp · 172,130 words

The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War (The Princeton Economic History of the Western World)

by Robert J. Gordon · 12 Jan 2016 · 1,104pp · 302,176 words

Age of Greed: The Triumph of Finance and the Decline of America, 1970 to the Present

by Jeff Madrick · 11 Jun 2012 · 840pp · 202,245 words

Grave New World: The End of Globalization, the Return of History

by Stephen D. King · 22 May 2017 · 354pp · 92,470 words

Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness

by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein · 7 Apr 2008 · 304pp · 22,886 words

Unelected Power: The Quest for Legitimacy in Central Banking and the Regulatory State

by Paul Tucker · 21 Apr 2018 · 920pp · 233,102 words

Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, Sixth Edition

by Kindleberger, Charles P. and Robert Z., Aliber · 9 Aug 2011

The White Man's Burden: Why the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good

by William Easterly · 1 Mar 2006

Why Information Grows: The Evolution of Order, From Atoms to Economies

by Cesar Hidalgo · 1 Jun 2015 · 242pp · 68,019 words

Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy

by Jonathan Taplin · 17 Apr 2017 · 222pp · 70,132 words

The Upside of Irrationality: The Unexpected Benefits of Defying Logic at Work and at Home

by Dan Ariely · 31 May 2010 · 324pp · 93,175 words

Liars and Outliers: How Security Holds Society Together

by Bruce Schneier · 14 Feb 2012 · 503pp · 131,064 words

Rockonomics: A Backstage Tour of What the Music Industry Can Teach Us About Economics and Life

by Alan B. Krueger · 3 Jun 2019

The Accidental Theorist: And Other Dispatches From the Dismal Science

by Paul Krugman · 18 Feb 2010 · 162pp · 51,473 words

Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions

by Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths · 4 Apr 2016 · 523pp · 143,139 words

Think Twice: Harnessing the Power of Counterintuition

by Michael J. Mauboussin · 6 Nov 2012 · 256pp · 60,620 words

The Physics of Wall Street: A Brief History of Predicting the Unpredictable

by James Owen Weatherall · 2 Jan 2013 · 338pp · 106,936 words

When to Rob a Bank: ...And 131 More Warped Suggestions and Well-Intended Rants

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 4 May 2015 · 306pp · 85,836 words

Humans as a Service: The Promise and Perils of Work in the Gig Economy

by Jeremias Prassl · 7 May 2018 · 491pp · 77,650 words

What's Mine Is Yours: How Collaborative Consumption Is Changing the Way We Live

by Rachel Botsman and Roo Rogers · 2 Jan 2010 · 411pp · 80,925 words

The Wisdom of Crowds

by James Surowiecki · 1 Jan 2004 · 326pp · 106,053 words

Testosterone Rex: Myths of Sex, Science, and Society

by Cordelia Fine · 13 Jan 2017 · 312pp · 83,998 words

The End of Ownership: Personal Property in the Digital Economy

by Aaron Perzanowski and Jason Schultz · 4 Nov 2016 · 374pp · 97,288 words

Nobody's Fool: Why We Get Taken in and What We Can Do About It

by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris · 10 Jul 2023 · 338pp · 104,815 words

The Economics of Enough: How to Run the Economy as if the Future Matters

by Diane Coyle · 21 Feb 2011 · 523pp · 111,615 words

The Tyranny of Metrics

by Jerry Z. Muller · 23 Jan 2018 · 204pp · 53,261 words

Value of Everything: An Antidote to Chaos The

by Mariana Mazzucato · 25 Apr 2018 · 457pp · 125,329 words

The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism

by Arun Sundararajan · 12 May 2016 · 375pp · 88,306 words

Green Swans: The Coming Boom in Regenerative Capitalism

by John Elkington · 6 Apr 2020 · 384pp · 93,754 words

Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us

by Daniel H. Pink · 1 Jan 2008 · 204pp · 54,395 words

Getting Back to Full Employment: A Better Bargain for Working People

by Dean Baker and Jared Bernstein · 14 Nov 2013 · 128pp · 35,958 words

The Devil's Derivatives: The Untold Story of the Slick Traders and Hapless Regulators Who Almost Blew Up Wall Street . . . And Are Ready to Do It Again

by Nicholas Dunbar · 11 Jul 2011 · 350pp · 103,270 words

Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy in the Aftermath of Crisis

by Anatole Kaletsky · 22 Jun 2010 · 484pp · 136,735 words

The Meritocracy Trap: How America's Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class, and Devours the Elite

by Daniel Markovits · 14 Sep 2019 · 976pp · 235,576 words

How to Fix Copyright

by William Patry · 3 Jan 2012 · 336pp · 90,749 words

Engineering Security

by Peter Gutmann

Trade Wars Are Class Wars: How Rising Inequality Distorts the Global Economy and Threatens International Peace

by Matthew C. Klein · 18 May 2020 · 339pp · 95,270 words

Windfall: The Booming Business of Global Warming

by Mckenzie Funk · 22 Jan 2014 · 337pp · 101,281 words

Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters

by Steven Pinker · 14 Oct 2021 · 533pp · 125,495 words

Trillion Dollar Triage: How Jay Powell and the Fed Battled a President and a Pandemic---And Prevented Economic Disaster

by Nick Timiraos · 1 Mar 2022 · 357pp · 107,984 words

Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire

by Rebecca Henderson · 27 Apr 2020 · 330pp · 99,044 words

The Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do About Them

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 15 Mar 2015 · 409pp · 125,611 words

Click Here to Kill Everybody: Security and Survival in a Hyper-Connected World

by Bruce Schneier · 3 Sep 2018 · 448pp · 117,325 words

The Wisdom of Finance: Discovering Humanity in the World of Risk and Return

by Mihir Desai · 22 May 2017 · 239pp · 69,496 words

Twilight of the Elites: America After Meritocracy

by Chris Hayes · 11 Jun 2012 · 285pp · 86,174 words

Chokepoint Capitalism

by Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow · 26 Sep 2022 · 396pp · 113,613 words

Crisis Economics: A Crash Course in the Future of Finance

by Nouriel Roubini and Stephen Mihm · 10 May 2010 · 491pp · 131,769 words

The Price of Everything: And the Hidden Logic of Value

by Eduardo Porter · 4 Jan 2011 · 353pp · 98,267 words

Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream

by Nicholas Lemann · 9 Sep 2019 · 354pp · 118,970 words

Where We Are: The State of Britain Now

by Roger Scruton · 16 Nov 2017 · 190pp · 56,531 words

Global Financial Crisis

by Noah Berlatsky · 19 Feb 2010

The Fissured Workplace

by David Weil · 17 Feb 2014 · 518pp · 147,036 words

Aftershock: The Next Economy and America's Future

by Robert B. Reich · 21 Sep 2010 · 147pp · 45,890 words

The Most Human Human: What Talking With Computers Teaches Us About What It Means to Be Alive

by Brian Christian · 1 Mar 2011 · 370pp · 94,968 words

Transport for Humans: Are We Nearly There Yet?

by Pete Dyson and Rory Sutherland · 15 Jan 2021 · 342pp · 72,927 words

The Curse of Cash

by Kenneth S Rogoff · 29 Aug 2016 · 361pp · 97,787 words

The Trouble With Billionaires

by Linda McQuaig · 1 May 2013 · 261pp · 81,802 words

Economic Gangsters: Corruption, Violence, and the Poverty of Nations

by Raymond Fisman and Edward Miguel · 14 Apr 2008

The Road to Ruin: The Global Elites' Secret Plan for the Next Financial Crisis

by James Rickards · 15 Nov 2016 · 354pp · 105,322 words

Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism: And Other Arguments for Economic Independence

by Kristen R. Ghodsee · 20 Nov 2018 · 211pp · 57,759 words

The Logic of Life: The Rational Economics of an Irrational World

by Tim Harford · 1 Jan 2008 · 250pp · 88,762 words

A Demon of Our Own Design: Markets, Hedge Funds, and the Perils of Financial Innovation

by Richard Bookstaber · 5 Apr 2007 · 289pp · 113,211 words

Free culture: how big media uses technology and the law to lock down culture and control creativity

by Lawrence Lessig · 15 Nov 2004 · 297pp · 103,910 words

The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy

by Dani Rodrik · 23 Dec 2010 · 356pp · 103,944 words

The Blockchain Alternative: Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy and Economic Theory

by Kariappa Bheemaiah · 26 Feb 2017 · 492pp · 118,882 words

Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis

by Robert D. Putnam · 10 Mar 2015 · 459pp · 123,220 words

Social Capital and Civil Society

by Francis Fukuyama · 1 Mar 2000

Information: A Very Short Introduction

by Luciano Floridi · 25 Feb 2010 · 137pp · 36,231 words

Alchemy: The Dark Art and Curious Science of Creating Magic in Brands, Business, and Life

by Rory Sutherland · 6 May 2019 · 401pp · 93,256 words

Open for Business Harnessing the Power of Platform Ecosystems

by Lauren Turner Claire, Laure Claire Reillier and Benoit Reillier · 14 Oct 2017 · 240pp · 78,436 words

The Loop: How Technology Is Creating a World Without Choices and How to Fight Back

by Jacob Ward · 25 Jan 2022 · 292pp · 94,660 words

Rewriting the Rules of the European Economy: An Agenda for Growth and Shared Prosperity

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 28 Jan 2020 · 408pp · 108,985 words

Jared Bibler

by Iceland's Secret The Untold Story of the World's Biggest Con-Harriman House (2021)