Google Glasses

description: a type of smart glasses developed by Google, allowing wearers to access information in a hands-free format.

150 results

Age of Context: Mobile, Sensors, Data and the Future of Privacy

by

Robert Scoble

and

Shel Israel

Published 4 Sep 2013

However, history indicates that when the tech community is unified, focused and excited about a topic, as it is about context, it almost always follows that they will make waves that land on the shores of commerce. Although this book introduces some thought leaders, the business community overall is not thinking much about context right now. But they will soon be productizing it and using it for competitive advantage. Context Through Google Glass Google Glass is the product that is raising public awareness, excitement and concerns about contextual computing. This wearable device is discussed in depth in Chapter 2. It is like nothing that has previously existed, containing sensors, a camera, a microphone, and a prism for projecting information in front of your eyes.

…

This and many other nascent revolutionary applications of contextual software are right around the corner. From a contextual perspective, we hold Google in particularly high regard, but the real game-changing development is the gadget Scoble is wearing on our back cover—Google Glass. Chapter 2 Through the Glass, Looking Right now, most of us look at the people with Google Glass like the dudes who first walked around with the big brick phones. Amber Naslund, SideraWorks The first of them went to Sergey Brin, Larry Page, and Eric Schmidt. Brin, who runs Project Glass, the company’s much-touted digital eyewear program, has rarely been seen in public again without them.

…

We believe something monumental is taking place, something that could change your life and work, your children’s future and the world in which your unborn descendants will live. Not Another Day Scoble was the 107th person to receive a Google Glass prototype. He put them on and immediately started posting short notes on his social networks about his experience. He wore them when he went to Europe, making presentations at tech conferences and letting hundreds of people give his Glass device a quick try. After two weeks, he posted his first review to Google+, the default social network for Google Glass users, declaring “I’m never going to live another day without a wearable computer on my face.” To illustrate his point, his wife Maryam photographed him in the shower wearing his Glass.

Future Crimes: Everything Is Connected, Everyone Is Vulnerable and What We Can Do About It

by

Marc Goodman

Published 24 Feb 2015

Tracking, Monitoring, and Wearable Tech,” Symantec Security Response, July 30, 2014. 5 Google has already: “Google Partners with Ray-Ban, Oakley for New Glass Designs,” NBC News, March 24, 2014; Deloitte, Technology, Media, and Telecommunications Predictions, 2014, 10. 6 The fear of filming: Richard Gray, “The Places Where Google Glass Is Banned,” Telegraph, Dec. 4, 2013. 7 In fact, hackers had already: Andy Greenberg, “Google Glass Has Already Been Hacked by Jailbreakers,” Forbes, April 26, 2013. 8 The GPS features: Mark Prigg, “Google Glass HACKED to Transmit Everything You See and Hear: Experts Warn ‘the Only Thing It Doesn’t Know Are Your Thoughts,’ ” Mail Online, May 2, 2013. 9 While your grandma: John Zorabedian, “Spyware App Turns the Privacy Tables on Google Glass Wearers,” Naked Security, March 25, 2014. 10 Given the pace: Katherine Bourzac, “Contact Lens Computer: Like Google Glass, Without the Glasses,” MIT Technology Review, June 7, 2013. 11 The device is in early stages: Leo King, “Google Smart Contact Lens Focuses on Healthcare Billions,” Forbes, July 15, 2014. 12 Not to be outdone: Bourzac, “Contact Lens Computer.” 13 The historic operation: N.

…

Chertoff of Homeland Security, with all of Google Glass’s power and connectivity come a host of privacy and public policy issues. But there are important security threats to be considered as well. The fear of filming has led to Google Glass’s being banned in a number of public venues, including sporting events, concerts, gym locker rooms, bars, restaurants, strip clubs, casinos, hospitals, and U.K. movie theaters. Cited reasons for the prohibitions against the device include everything from card counting to film piracy and industrial espionage. But there is another concern. Google Glass can be hacked to secretly take photographs and record video, silently streaming the data to Crime, Inc. anywhere in the world, all without the knowledge of the device’s owner.

…

For more detailed reviews on the large number of violations alleged against Google, see www.googlemonitor.com. 14 After a lawsuit: David Streitfeld, “Google Admits Street View Project Violated Privacy,” New York Times, March 12, 2013; David Kravets, “An Intentional Mistake: The Anatomy of Google’s Wi-Fi Sniffing Debacle,” Wired, May 2, 2012. 15 In October 2013, a federal judge: Claire Cain Miller, “Google Accused of Wiretapping in Gmail Scans,” New York Times, Oct. 1, 2013. 16 In early 2014, Google Glass was the subject: David Pierce, “The Simpsons May Have the Smartest Thoughts Yet About Google Glass,” Verge, Jan. 27, 2014. 17 Even the former head: Michael Chertoff, “Google Glass, the Beginning of Wearable Surveillance,” CNN, May 1, 2013. 18 With more than 1.2 billion: PRNewswire, “Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2013 Results,” Facebook: Investor Relations, Jan. 29, 2014. 19 It has been sued: Karen Gullo, “Facebook Sued over Alleged Scanning of Private Messages,” Bloomberg, Jan. 2, 2014. 20 For example, did you realize: Robert McMillan, “Apple Finally Reveals How Long Siri Keeps Your Data,” Wired, April 19, 2013. 21 The Web site with the most: “What They Know,” Wall Street Journal series, http://blogs.wsj.com/wtk/. 22 So if you use your university: Adi Robertson, “Angry Email Users Can Take Google to Court for Keyword Scanning, Judge Rules,” Verge, Sept. 26, 2013. 23 “a person has no”: Ibid.; Cooley LLP, “Google’s Motion to Dismiss Complaint Memorandum of Points & Authorities,” U.S.

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

by

Shoshana Zuboff

Published 15 Jan 2019

See Stephen Graves, “Niantic Labs’ John Hanke on Alternate Reality Games and the Future of Storytelling,” PC&Tech Authority, October 13, 2014. 74. David DiSalvo, “The Banning of Google Glass Begins (and They Aren’t Even Available Yet),” Forbes, March 10, 2013, http://www.forbes.com/sites/daviddisalvo/2013/03/10/the-ban-on-google-glass-begins-and-they-arent-even-available-yet; David Streitfeld, “Google Glass Picks Up Early Signal: Keep Out,” New York Times, May 6, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/07/technology/personaltech/google-glass-picks-up-early-signal-keep-out.html. 75. Aaron Smith, “U.S. Views of Technology and the Future,” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech (blog), April 17, 2014, http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/04/17/us-views-of-technology-and-the-future. 76.

…

Views of Technology and the Future,” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech (blog), April 17, 2014, http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/04/17/us-views-of-technology-and-the-future. 76. Drew FitzGerald, “Now Google Glass Can Turn You into a Live Broadcast,” Wall Street Journal, June 24, 2014, http://www.wsj.com/articles/now-google-glass-can-turn-you-into-a-live-broadcast-1403653079. 77. See Amir Efrati, “Google Glass Privacy Worries Lawmakers,” Wall Street Journal, May 17, 2013, http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB100014241278873247 67004578487661143483672. 78. “We’re Graduating from Google[x] Labs,” Google, January 15, 2015, https://plus.google.com/app/basic/stream/z124trxirsruxvcdp23otv4qerfwghdhv04. 79. Alistair Barr, “Google Glass Gets a New Name and Hires from Amazon,” Wall Street Journal, September 16, 2015. 80.

…

The invasive practices introduced with Buzz—it commandeered users’ private information to establish their social networks by fiat—set off a fresh round of the dispossession cycle and its dramatic contests. As Google learned to successfully redirect supply routes, evading and nullifying opposition, it became even more emboldened to let slip the dogs of audacity and direct them toward havoc. Among many examples, Google Glass neatly illustrates the tenacity of the extraction imperative and its translation into commercial practice. Google Glass combined computation, communication, photography, GPS tracking, data retrieval, and audio and video recording capabilities in a wearable format patterned on eyeglasses. The data it gathered—location, audio, video, photos, and other personal information—moved from the device to Google’s servers, merging with other supply routes to join the titanic one-way flow of behavioral surplus.

Utopia Is Creepy: And Other Provocations

by

Nicholas Carr

Published 5 Sep 2016

To exaggerate a distinction seems a lesser crime than to pretend it doesn’t exist. GOOGLE GLASS AND CLAUDE GLASS September 19, 2012 GOOGLE COFOUNDER SERGEY BRIN made a stir earlier this month when he catted about New York Fashion Week with a Google Glass wrapped around his bean. It was something of a coming-out party for Google’s reality-augmentation device, which promises to democratize the head-up display, giving us all a fighter pilot’s view of the world. Diane von Furstenberg got Glassed. So did Sarah Jessica Parker. Wendi Murdoch seemed impressed by the cyborgian adornment, as did her husband, Rupert, who promptly tweeted, “Genius!” Google Glass is shaping up to be the biggest thing to hit the human brow since Olivia Newton-John’s headband.

…

Where a Claude Glass bathed landscapes in a soft painterly light, a Google Glass bathes them in hard data. It gives its owner the eyes not of an artist but of an analyst. Instead of a pastoral illusion, you get a computational one. But while the perspectives displayed by the two gadgets couldn’t be more different, the Claude Glass and the Google Glass share some important qualities. Both tell us that our senses are insufficient, that manufactured vision is superior to what our own meager eyeballs can reveal to us. And both turn the world into a packaged good—a product to be consumed. A Google Glass is superior to a Claude Glass in this regard.

…

THE MEANS OF CREATIVITY VAMPIRES BEHIND THE HEDGEROW, EATING GARBAGE THE SOCIAL GRAFT SEXBOT ACES TURING TEST LOOKING INTO A SEE-THROUGH WORLD GILLIGAN’S WEB COMPLETE CONTROL EVERYTHING THAT DIGITIZES MUST CONVERGE RESURRECTION ROCK-BY-NUMBER RAISING THE VIRTUAL CHILD THE IPAD LUDDITES NOWNESS CHARLIE BIT MY COGNITIVE SURPLUS MAKING SHARING SAFE FOR CAPITALISTS THE QUALITY OF ALLUSION IS NOT GOOGLE SITUATIONAL OVERLOAD AND AMBIENT OVERLOAD GRAND THEFT ATTENTION MEMORY IS THE GRAVITY OF MIND THE MEDIUM IS McLUHAN FACEBOOK’S BUSINESS MODEL UTOPIA IS CREEPY SPINELESSNESS FUTURE GOTHIC THE HIERARCHY OF INNOVATION RIP. MIX. BURN. READ. LIVE FAST, DIE YOUNG, AND LEAVE A BEAUTIFUL HOLOGRAM ONLINE, OFFLINE, AND THE LINE BETWEEN GOOGLE GLASS AND CLAUDE GLASS BURNING DOWN THE SCHOOLHOUSE THE ENNUI OF THE INTELLIGENT MACHINE REFLECTIONS WILL GUTENBERG LAUGH LAST? THE SEARCHERS ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS AI MAX LEVCHIN HAS PLANS FOR US EVGENY’S LITTLE PROBLEM THE SHORTEST CONVERSATION BETWEEN TWO POINTS HOME AWAY FROM HOME CHARCOAL, SHALE, COTTON, TANGERINE, SKY SLUMMING WITH BUDDHA THE QUANTIFIED SELF AT WORK MY COMPUTER, MY DOPPELTWEETER UNDERWEARABLES THE BUS THE MYTH OF THE ENDLESS LADDER THE LOOM OF THE SELF TECHNOLOGY BELOW AND BEYOND OUTSOURCING DAD TAKING MEASUREMENT’S MEASURE SMARTPHONES ARE HOT DESPERATE SCRAPBOOKERS OUT OF CONTROL OUR ALGORITHMS, OURSELVES TWILIGHT OF THE IDYLLS THE ILLUSION OF KNOWLEDGE WIND-FUCKING THE SECONDS ARE JUST PACKED MUSIC IS THE UNIVERSAL LUBRICANT TOWARD A UNIFIED THEORY OF LOVE <3S AND MINDS IN THE KINGDOM OF THE BORED, THE ONE-ARMED BANDIT IS KING THESES IN TWEETFORM THE EUNUCH’S CHILDREN: ESSAYS AND REVIEWS FLAME AND FILAMENT IS GOOGLE MAKING US STUPID?

I Hate the Internet: A Novel

by

Jarett Kobek

Published 3 Nov 2016

Over the summer, news had broken that Sergey Brin was having an affair with an underling at Google X. Google X was an experimental lab that developed products like driverless cars, dogs that don’t need to lick their own genitals, and Google Glass. Google Glass was a wearable computer built into a pair of ugly eyeglasses. Google Glass allowed its wearers to act out their social inadequacies. They could record videos with Google Glass and alienate everyone in their surrounding vicinity. Sergey Brin’s sexual dalliance was with the Marketing Manager for Google Glass. He had internalized his company’s business model. “I told you,” said Christine. “Google X is just picking up chicks.” Adeline decided to go home.

…

She heard a bus pulling up opposite her. It was a Google bus. The door of the Google bus opened. A team of twenty engineers emerged. They all sported Google Glass, a wearable computer built into eyeglasses. The principle virtue of Google Glass was that it allowed its wearers to record videos and thus act out their social inadequacies by alienating everyone around them. Adeline made a clucking noise about the team of engineers wearing Google Glass. She thought that they looked simply absurd. Then Adeline remembered she was still wearing 2014 on her face. The engineers all wore matching t-shirts which read: GOOGLE GOES GAGA.

Soonish: Ten Emerging Technologies That'll Improve And/or Ruin Everything

by

Kelly Weinersmith

and

Zach Weinersmith

Published 16 Oct 2017

A lot of the sources we read on this topic were written between 2010 and 2014. The later ones tend to be really excited about how Google Glass is gonna change everything. Whoops. Google Glass is generally considered to have failed because when people see you wearing it, they want to punch you in the face. No, really. For instance, in 2013 the CEO of Meetup.com literally said to Business Insider reporters, “Google Glass? I’m definitely gonna punch someone in the face wearing Google Glasses.” So one feature you’d want in the future of AR is a display that doesn’t get you punched in the face by tech millionaires.

…

“NRC’s ‘All or Nothing’ Licensing Process Doesn’t Work, Former Commissioner Says.” Morning Consult.com, April 29, 2016. morningconsult.com/alert/nrcs-nothing-licensing-process-doesnt-work-former-commissioner-says. Goodman, Daniel, and Angelova, Kamelia. “TECH STAR: I Want To Punch Anyone Wearing Google Glass in the Face.” BusinessInsider, May 10, 2013. businessinsider.com/meetup-ceo-scott-heiferman-on-google-glass-2013-5. (Note: The video on this page is no longer working.) Graber, John. “SpriteMods.com’s 3D Printer Makes Food Dye Designs in JELLO.” 3D Printer World. January 4, 2014. 3dprinterworld.com/article/spritemodscoms-3d-printer-makes-food-dye-designs-jello.

…

So one feature you’d want in the future of AR is a display that doesn’t get you punched in the face by tech millionaires. The trick there may be miniaturization. Innovega is one company working on an AR contact lens. It’s not quite to the point where a contact lens can do the whole job, though. In fact, you have to wear a special pair of glasses over the contact lens. On the plus side, unlike Google Glass, it pretty much actually looks like a pair of glasses. In general, sensors and computation systems are getting cheaper, faster, and smaller. This provides fertile ground for experimental projects, of which there are many. Dr. Mark Billinghurst, currently at the University of Canterbury, came up with a concept called a “magic book.”

The Internet Is Not the Answer

by

Andrew Keen

Published 5 Jan 2015

Another smart clothing company, Heapsylon, even had a sports bra made of textile electrodes designed to monitor its wearer’s vital statistics.22 While Google wasn’t officially represented in the Augmented Reality Pavilion, there were plenty of early adopters wandering around the Venetian’s fake piazzas and canals wearing demonstration models of Google Glass, Google’s networked electronic eyeglasses. Michael Chertoff, the former US secretary of homeland security, described these glasses, which have been designed to take both continuous video and photos of everything they see, as inaugurating an age of “ubiquitous surveillance.”23 Chertoff is far from alone is being creeped out by Google Glass. Several San Francisco bars have banned Google Glass wearers—known locally as “Glassholes”—from entry. The US Congress has already launched an inquiry into their impact on privacy.

…

Google’s advertising network was becoming as ubiquitous as Google search. AdWords and AdSense together represented what Levy calls a “cash cow” to fund the next decade’s worth of Web projects, which included the acquisition of YouTube and the creation of the Android mobile operating system, Gmail, Google+, Blogger, the Chrome browser, Google self-driving cars, Google Glass, Waze, and its most recent roll-up of artificial intelligence companies including DeepMind, Boston Dynamics, and Nest Labs.70 More than just cracking the code on Internet profits, Google had discovered the holy grail of the information economy. In 2001, revenues were just $86 million. They rose to $347 million in 2002, then to just under a billion dollars in 2003 and to almost $2 billion in 2004, when the six-year-old company went public in a $1.67 billion offering that valued it at $23 billion.

…

At the Indiegogo-sponsored section of the show, hidden in the bowels of the Venetian, one crowd-financed startup from Berlin named Panono was showing off what it called a “panoramic ball camera,” an 11 cm electronic ball with thirty-six tiny cameras attached to it, that took panoramic photos whenever the ball was thrown in the air and then, of course, distributed them on the network. Another Indiegogo company, an Italian startup called GlassUP, was demonstrating fashionably designed glasses that—like Google Glass—recorded everything they saw and provided what it called a “second screen” to check emails and read online breaking news. There were even “Eyes-On” X-ray style glasses, from a company called Evena Medical, that allowed nurses to see through a patient’s skin and spy the veins underneath. Just about the only thing I didn’t see in the Venetian were cameras hidden inside watering cans.

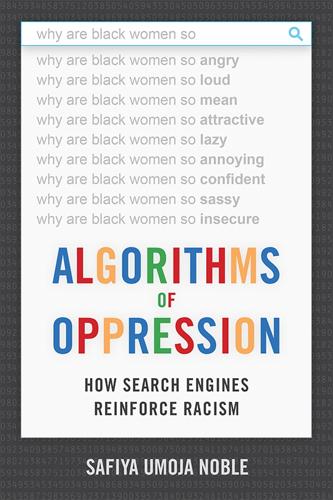

Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism

by

Safiya Umoja Noble

Published 8 Jan 2018

Roberts about the myriad problems with a project such as Google Glass and the problems of class privilege that directly map to the failure of the project and the intensifying distrust of Silicon Valley gentrifiers in tech corridors such as San Francisco and Seattle.39 The lack of introspection about the public wanting to be surveilled at the level of intensity that Google Glass provided is part of the problem: centuries-old concepts of conquest and exploration of every landscape, no matter its inhabitants, are seen as emancipatory rather than colonizing and totalizing for people who fall within its gaze. People on the street may not characterize Google Glass as a neocolonial project in the way we do, but they certainly know they do not like seeing it pointed in their direction; and the visceral responses to Google Glass wearers as “Glassholes” is just one indicator of public distrust of these kinds of privacy intrusions. The neocolonial trajectories are not just in products such as search or Google Glass but exist throughout the networked economy, where some people serve as the most exploited workers, including child and forced laborers,40 in such places as the Democratic Republic of Congo, mining ore called columbite-tantalite (abbreviated as “coltan”) to provide raw materials for companies such as Nokia, Intel, Sony, and Ericsson (and now Google)41 that need such minerals in the production of components such as tantalum capacitors, used to make microprocessor chips for computer hardware such as phones and computers.42 Others in the digital-divide network serve as supply-chain producers for hardware companies such as Apple43 or Dell,44 and this outsourced labor from the U.S. goes to low bidders that provide the cheapest labor under neoliberal economic policies of globalization.

…

Thinking about the specifics of who benefits from these practices—from hiring to search results to technologies of surveillance—these are problems and projects that are not equally experienced. I have written, for example, with my colleague Sarah T. Roberts about the myriad problems with a project such as Google Glass and the problems of class privilege that directly map to the failure of the project and the intensifying distrust of Silicon Valley gentrifiers in tech corridors such as San Francisco and Seattle.39 The lack of introspection about the public wanting to be surveilled at the level of intensity that Google Glass provided is part of the problem: centuries-old concepts of conquest and exploration of every landscape, no matter its inhabitants, are seen as emancipatory rather than colonizing and totalizing for people who fall within its gaze.

…

However, what is missing from the extant work on Google is an intersectional power analysis that accounts for the ways in which marginalized people are exponentially harmed by Google. Since I began writing this book, Google’s parent company, Alphabet, has expanded its power into drone technology,8 military-grade robotics, fiber networks, and behavioral surveillance technologies such as Nest and Google Glass.9 These are just several of many entry points to thinking about the implications of artificial intelligence as a human rights issue. We need to be concerned about not only how ideas and people are represented but also the ethics of whether robots and other forms of automated decision making can end a life, as in the case of drones and automated weapons.

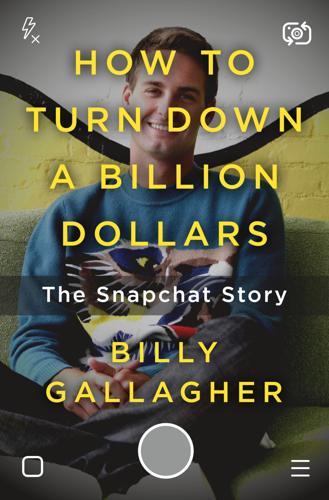

How to Turn Down a Billion Dollars: The Snapchat Story

by

Billy Gallagher

Published 13 Feb 2018

In March 2014, Evan rolled the dice on a company that had a chance to be a true game-changer for Snapchat. Snapchat paid $15 million to acquire a small hardware startup called Vergence Labs. Vergence made a Google Glass–like product they called Epiphany Eyewear that could record video and upload it to a computer. Erick Miller had begun working on the idea while studying for his MBA at UCLA in 2011; he was initially working on a set of virtual reality goggles, but when Google Glass was announced, he realized he could make something more fashion-forward that wasn’t as awkward to use and look at. Although Miller raised $70,000 on Indiegogo (a popular crowdfunding platform), he was still remarkably persistent in searching for funding, often walking around outside Facebook’s campus trying to catch Mark Zuckerberg walking to his car to pitch him.

…

We can’t tell you who. You’ll get a check in the mail.” The division’s future depended just as much on its technical progress as it did on Evan’s evolving view of wearable technology. In September 2013, Evan spoke at the TechCrunch Disrupt conference, when Google Glass was near the height of its hype; he said Snapchat was not even considering building an app for Google Glass, saying it felt “invasive,” like “a gun pointed at you.” It remained to be seen if Vergence would ever launch a real product into the world or just stay hidden as an internal Snapchat experiment. CHAPTER TWENTY GOODBYE REGGIE MAY 2014 RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL luau fucking raged.

…

The product debuted in the glossy WSJ Magazine, and Evan was photographed wearing Spectacles, along with his classic white v-neck, by fashion icon Karl Lagerfeld. Quick to distance the product from the nerdy and invasive Google Glass and to avoid overhyped expectations, Evan characterized Spectacles in interviews as a fun toy. Years before, Evan had noted that Snapchat would not build an app for Google Glass because he found the product “invasive,” like “a gun pointed at you.” To relieve people of the feeling that Spectacles were a social media gun aimed at them, and to address privacy concerns, little lights on the front of the sunglasses illuminate when the user is taking a picture or recording video.

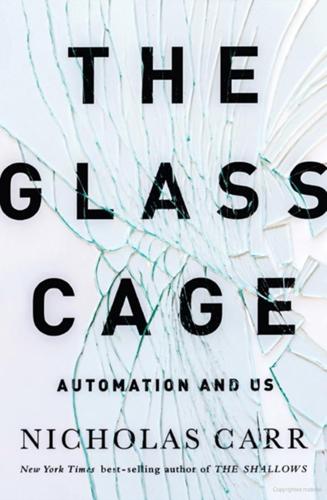

The Glass Cage: Automation and Us

by

Nicholas Carr

Published 28 Sep 2014

Bohbot, “Spatial Navigational Strategies Correlate with Gray Matter in the Hippocampus of Healthy Older Adults Tested in a Virtual Maze,” Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 5 (2013): 1–8. 24.Email from Véronique Bohbot to author, June 4, 2010. 25.Quoted in Alex Hutchinson, “Global Impositioning Systems,” Walrus, November 2009. 26.Kyle VanHemert, “4 Reasons Why Apple’s iBeacon Is About to Disrupt Interaction Design,” Wired, December 11, 2013, www.wired.com/design/2013/12/4-use-cases-for-ibeacon-the-most-exciting-tech-you-havent-heard-of/. 27.Quoted in Fallows, “Places You’ll Go.” 28.Damon Lavrinc, “Mercedes Is Testing Google Glass Integration, and It Actually Works,” Wired, August 15, 2013, wired.com/autopia/2013/08/google-glass-mercedes-benz/. 29.William J. Mitchell, “Foreword,” in Yehuda E. Kalay, Architecture’s New Media: Principles, Theories, and Methods of Computer-Aided Design (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2004), xi. 30.Anonymous, “Interviews: Renzo Piano,” Architectural Record, October 2001, archrecord.construction.com/people/interviews/archives/0110piano.asp. 31.Quoted in Gavin Mortimer, The Longest Night (New York: Penguin, 2005), 319. 32.Dino Marcantonio, “Architectural Quackery at Its Finest: Parametricism,” Marcantonio Architects Blog, May 8, 2010, blog.marcantonioarchitects.com/architectural-quackery-at-its-finest-parametricism/. 33.Paul Goldberger, “Digital Dreams,” New Yorker, March 12, 2001. 34.Patrik Schumacher, “Parametricism as Style—Parametricist Manifesto,” Patrik Schumacher’s blog, 2008, patrikschumacher.com/Texts/Parametricism%20as%20Style.htm. 35.Anonymous, “Interviews: Renzo Piano.” 36.Witold Rybczynski, “Think before You Build,” Slate, March 30, 2011, slate.com/articles/arts/architecture/2011/03/think_before_you_build.html. 37.Quoted in Bryan Lawson, Design in Mind (Oxford, U.K.: Architectural Press, 1994), 66. 38.Michael Graves, “Architecture and the Lost Art of Drawing,” New York Times, September 2, 2012. 39.D.

…

Scattered around stores and other spaces, iBeacon transmitters act as artificial place cells, activating whenever a person comes within range. They herald the onset of what Wired magazine calls “microlocation” tracking.26 Indoor mapping promises to ratchet up our dependence on computer navigation and further limit our opportunities for getting around on our own. Should personal head-up displays, such as Google Glass, come into wide use, we would always have easy and immediate access to turn-by-turn instructions. We’d receive, as Google’s Michael Jones puts it, “a continuous stream of guidance,” directing us everywhere we want to go.27 Google and Mercedes-Benz are already collaborating on an app that will link a Glass headset to a driver’s in-dash GPS unit, enabling what the carmaker calls “door-to-door navigation.”28 With the GPS goddess whispering in our ear, or beaming her signals onto our retinas, we’ll rarely, if ever, have to exercise our mental mapping skills.

…

Brian Arthur, “The Second Economy,” McKinsey Quarterly, October 2011. 17.Ibid. 18.Bill Gates, Business @ the Speed of Thought: Using a Digital Nervous System (New York: Warner Books, 1999), 37. 19.Arthur C. Clarke, Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible (New York: Harper & Row, 1960), 227. 20.Sergey Brin, “Why Google Glass?,” speech at TED2013, Long Beach, Calif., February 27, 2013, youtube.com/watch?v=rie-hPVJ7Sw. 21.Ibid. 22.See Christopher D. Wickens and Amy L. Alexander, “Attentional Tunneling and Task Management in Synthetic Vision Displays,” International Journal of Aviation Psychology 19, no. 2 (2009): 182–199. 23.Richard F.

The Runaway Species: How Human Creativity Remakes the World

by

David Eagleman

and

Anthony Brandt

Published 30 Sep 2017

In order to briskly design and filter new products, X developed “Home” and “Away” teams. When Google came up with an idea for wearable computing – Google Glass – the Home team was tasked with quickly creating a working model. Using a coat hanger, a low-cost projector and a clear plastic sheet protector as a screen, the Home team built the first mock-up of Glass in one day. The job of the Away team was to rush out to a public space like a shopping mall and get as much feedback from potential customers as they could. An early model of Google Glass weighed 8 pounds – it was more of a helmet than a pair of eyeglasses. The Home team thought they had hit pay dirt when they got that weight down to less than that of an average pair of spectacles.

…

The Arts and Achievement in At-Risk Youth: Findings from Four Longitudinal Studies. Washington: National Endowment for the Arts, 2012. Chanin, A.L., “Les Demoiselles de Picasso,” New York Times, August 18, 1957. Chi, Tom. “Rapid Prototyping Google Glass.” TED-Ed. November 17, 2012. Accessed May 17, 2016. <http://ed.ted.com/lessons/rapid-prototyping-google-glass-tom-chi#watch> Chin, Andrea. “Ai Weiwei Straightens 150 Tons of Steel Rebar from Sichuan Quake.” Designboom. June 4, 2013. Accessed May 11, 2016. <http://www.designboom.com/art/ai-weiwei-straightens-150-tons-of-steel-rebar-from-sichuan-quake/> Cho, Yun Sun et al.

…

There were insurmountable privacy concerns with the idea, mostly pivoting on the fact that bystanders didn’t want to be videoed. Abandoning Glass didn’t harm the Google enterprise, though: the engineers and designers went on to other teams, utilizing what they’d learned on other projects. In the end, Google Glass was just one of many fruits on the company’s tree, and it wasn’t the best one. Google had plenty of others, so they weren’t afraid to drop what wasn’t working. Generating ideas and trashing most of them can feel wasteful, but it’s the heart of the creative process. In a world in which time is money, the challenge is that the hours spent sketching or brainstorming can be viewed as lost productivity.

Radical Technologies: The Design of Everyday Life

by

Adam Greenfield

Published 29 May 2017

Unsurprisingly, concerns centered more on the device’s data-collection capability than anything else: according to 5 Point owner Dave Meinert, his customers “don’t want to be secretly filmed or videotaped and immediately put on the Internet.” This is, of course, an entirely reasonable expectation, not merely in the liminal space of a dive bar but anywhere in the city. Casey Newton, “Seattle dive bar becomes first to ban Google Glass,” CNET, March 8, 2013. 23.Dan Wasserman, “Google Glass Rolls Out Diane von Furstenberg frames,” Mashable, June 23, 2014. 4Digital fabrication 1.John Von Neumann, Theory of Self-Reproducing Automata, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1966, cba.mit.edu/events/03.11.ASE/docs/VonNeumann.pdf. 2.You may be familiar with cellular automata from John Conway’s 1970 Game of Life, certainly the best-known instance of the class.

…

The sole genuine justification for AR is the idea that information is simply there, and can be assimilated without thought or effort. And if this sense of effortlessness will never truly be achievable via handset, it is precisely what an emerging class of wearable mediators aims to provide for its users. The first of this class to reach consumers was the ill-fated Google Glass, which mounted a high-definition, forward-facing camera, a head-up reticle and the microphone required by its natural-language speech recognition interface on a lightweight aluminum frame. While Glass posed any number of aesthetic, practical and social concerns—all of which remain to be convincingly addressed, by Google or anyone else—it does at least give us a way to compare hands-free, head-mounted AR with the handset-based approach.

…

This is of special concern given the prospect that one or another form of wearable AR might become as prominent in the negotiation of everyday life as the smartphone itself. There is, of course, not much in the way of meaningful prognostication that can be made ahead of any mass adoption, but it’s not unreasonable to build our expectations on the few things we do know empirically. Early users of Google Glass reported disorientation upon removing the headset, after as few as fifteen minutes of use. This is a mild disorientation, to be sure, and easily shaken off—from all accounts, the sort of uneasy feeling that attends staring over-long at an optical illusion, and not the more serious nausea and dizziness suffered by a significant percentage of those using VR.12 If this represents the outer limit of discomfort experienced by users, it’s hard to believe that it would have much impact on either the desirability of the product or people’s ability to function after using it.

The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future

by

Kevin Kelly

Published 6 Jun 2016

Right now, if you mash up Google Maps and monster.com, you get maps of where jobs are located by salary. In the same way, it is easy to see that, in the great networked library, everything that has ever been written about, for example, Trafalgar Square in London could be visible while one stands in Trafalgar Square via a wearable screen like Google Glass. In the same way, every object, event, or location on earth would “know” everything that has ever been written about it in any book, in any language, at any time. From this deep structuring of knowledge comes a new culture of participation. You would be interacting—with your whole body—with the universal book.

…

Computer chips are becoming so small, and screens so thin and cheap, that in the next 30 years semitransparent eyeglasses will apply an informational layer to reality. If you pick up an object while peering through these spectacles, the object’s (or place’s) essential information will appear in overlay text. In this way screens will enable us to “read” everything, not just text. Yes, these glasses look dorky, as Google Glass proved. It will take a while before their form factor is worked out and they look fashionable and feel comfortable. But last year alone, five quintillion (10 to the power of 18) transistors were embedded into objects other than computers. Very soon most manufactured items, from shoes to cans of soup, will contain a small sliver of dim intelligence, and screens will be the tool we use to interact with this ubiquitous cognification.

…

And since what is in front of your eyes is just a small surface area, it is much easier and cheaper to magnify small improvements in quality. This tiny little area can invoke a huge disruptive presence. But while “presence” will sell it, VR’s enduring benefits spring from its interactivity. It is unclear how comfortable, or uncomfortable, we’ll be with the encumbrances of VR gear. Even the streamlined Google Glass (which I also tried), a very mild AR display not much bigger than sunglasses, seemed too much trouble for most people in its first version. Presence will draw users in, but it is the interactivity quotient of VR that will keep it going. Interacting in all degrees will spread out to the rest of the technological world

Industry 4.0: The Industrial Internet of Things

by

Alasdair Gilchrist

Published 27 Jun 2016

It is not very efficient and they have the same problems as the forklift drivers, finding their way around the warehouse and locating the stock. However, help is at hand through augmented reality. The most commonly known augmented reality device is Google Glass; however, other manufacturers produce products with AR capabilities. Where augmented reality or, for the sake of explanation, Google Glass, comes into logistics is that it is extremely beneficial for human stock pickers. Google Glass can show on the heads up and hand free display the pick list, but can also show additional information such as location of the item and give directions on how to get there. Furthermore, it can capture an image of the item to verify it is the correct stock item.

…

Each of these virtual supermarkets has a completely empty floor space and situated near high footfall areas (e.g., train or subway stations, parks, and universities). The interesting thing is that while the naked eye will just see empty floors and walls, people using an AR-capable device, for example Google Glass, will see shelves filled with vegetables, fruit, meat, fish, beer, and all sorts of real-world products. To buy these virtual products, the customer scans each virtual product with their own mobile devices, adding it to their online shopping carts. They subsequently receive delivery of the products to their homes.

…

Gilchrist, Industry 4.0, DOI 10.1007/978-1-4842-2047-4 246 Index Constrained application protocol (CoAP), 128 advanced analytics, 84 queries, 83 storage, persistence, and retrieval serves, 83 Control area network (CAN), 181 Customers’ premise equipment (CPE), 42 Cyber-physical system (CPS), 36 D Data bus, 139 Data distribution service (DDS), 138 Data management, 82 Delay tolerant networks (DTN), 139 Distributed component object model (DCOM), 148 Dynamic name server (DNS), 127 E Epidemic technique, 141 Ethernet, 120, 127 Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP), 137 F Functional domains, 69 asset management, 71 communication function, 70 control domain, 70 executor, 71 modeling data, 71 G Giraff, 15 Google Glass, 25 H Human machine interface (HMI), 20–21, 45 HVAC system, 131 I, J, K Identity access management (IAM), 191 IIoT architecture architectural topology, 75 data management, 82 IIAF application domain, 75 Business domain, 75 Business viewpoint, 68 functional domains (see Functional domains) information domain, 73 operation domain, 72 stakeholder, 67 usage viewpoint, 68 implementation viewpoint, 75 Industrial Internet IIC, 66 IISs, 66 ISs, 66 M2M, 66 key system characteristics, 79 communication layer functions, 81 connectivity functions, 80 data communications, 79 deliver data, 80 M2M, 65 three-tier topology communication transport layer, 78 connectivity, 78 connectivity framework layer, 78 edge tier, 76 enterprise tier, 76 gateway-mediated edge, 77 platform tier, 76 IIoT middleware architecture, 156 commercial platforms, 160 components, 156 conceptual diagram, 154 connectivity platforms, 157 mobile operators, 158 open source solutions, 160 requirements, 159 IIoT WAN technology 3G/4G/LTE, 164 cable modem, 166 DWDM, 165 free space optics, 166 Index FTTX, 165 internet connectivity, 162 M2M Dash7 protocol, 172 LoRaWAN architecture, 171 LTE cellular technology, 175 MAC/PHY layer, 169 millimeter radio, 176 OSI layers, 169 requirements, 167 RPMA LP-WAN, 173 SigFox, 170 Weightless SIG, 175 Wi-Fi, 174 MPLS, 164 SDH/Sonnet, 163 VSAT, 167 WAN channels, 162 WiMax, 166 xDSL, 163 Industrial Internet 3D printing, 60 augmented reality (AR), 59 Big Data, 52 business value, 55 variety, 54 velocity, 54 veracity, 55 visualizing data, 55 volumes of, data, 53 CAN network, 181 Cloud model, 47 CPS, 35 fog network, 51 ICS, 180 IFE, 182 IP Mobility, 40 M2M learning and artificial intelligence, 56 Miniaturization, 34 Network virtualization, 43 NFV, 42 people vs. automation, 62 remote I/O devices, 34 Russian hackers, 180 SDN, 44 SDN vs.

The Road to Conscious Machines

by

Michael Wooldridge

Published 2 Nov 2018

What happens if each of us is perceiving the world in a completely different way? AI might make this possible. In 2013, Google released a wearable computer technology called Google Glass. Resembling everyday spectacles, Google Glass was equipped with a camera and a small projector. The glasses connected to a smartphone via a Bluetooth connection. Upon release there were immediate concerns about the ‘concealed’ camera in Google Glass being used to take pictures in inappropriate situations, but the real potential of the device was in the built-in projector, which could overlay whatever the user was seeing with a projected image.

…

For example, one thing I am personally very bad at is recognizing people: it is a source of continual embarrassment that I meet people I know well but nevertheless struggle to recognize. A Google Glass application that could identify the people I’m looking at and discreetly remind me of their names would be wonderful. These types of applications are called augmented reality: they take the real world and overlay it with computer-generated information or images. But what about apps that do not augment reality but completely change it, in a way that is imperceptible to users? My son, Tom, is 13 years old at the time of writing. He is a big fan of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings books, and the films that were made from them. Imagine a Google Glass app that altered his view of school so that his friends looked like elves, and his schoolteachers looked like orcs.

…

A A* 77 À la recherche du temps perdu (Proust) 205–8 accountability 257 Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) 87–8 adversarial machine learning 190 AF (Artificial Flight) parable 127–9, 243 agent-based AI 136–49 agent-based interfaces 147, 149 ‘Agents That Reduce Work and Information Overload’ (Maes) 147–8 AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) 41 AI – difficulty of 24–8 – ethical 246–62, 284, 285 – future of 7–8 – General 42, 53, 116, 119–20 – Golden Age of 47–88 – history of 5–7 – meaning of 2–4 – narrow 42 – origin of name 51–2 – strong 36–8, 41, 309–14 – symbolic 42–3, 44 – varieties of 36–8 – weak 36–8 AI winter 87–8 AI-complete problems 84 ‘Alchemy and AI’ (Dreyfus) 85 AlexNet 187 algorithmic bias 287–9, 292–3 alienation 274–7 allocative harm 287–8 AlphaFold 214 AlphaGo 196–9 AlphaGo Zero 199 AlphaZero 199–200 Alvey programme 100 Amazon 275–6 Apple Watch 218 Argo AI 232 arithmetic 24–6 Arkin, Ron 284 ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency) 87–8 Artificial Flight (AF) parable 127–9, 243 Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) 41 artificial intelligence see AI artificial languages 56 Asilomar principles 254–6 Asimov, Isaac 244–6 Atari 2600 games console 192–6, 327–8 augmented reality 296–7 automated diagnosis 220–1 automated translation 204–8 automation 265, 267–72 autonomous drones 282–4 Autonomous Vehicle Disengagement Reports 231 autonomous vehicles see driverless cars autonomous weapons 281–7 autonomy levels 227–8 Autopilot 228–9 B backprop/backpropagation 182–3 backward chaining 94 Bayes nets 158 Bayes’ Theorem 155–8, 365–7 Bayesian networks 158 behavioural AI 132–7 beliefs 108–10 bias 172 black holes 213–14 Blade Runner 38 Blocks World 57–63, 126–7 blood diseases 94–8 board games 26, 75–6 Boole, George 107 brains 43, 306, 330–1 see also electronic brains branching factors 73 Breakout (video game) 193–5 Brooks, Rodney 125–9, 132, 134, 243 bugs 258 C Campaign to Stop Killer Robots 286 CaptionBot 201–4 Cardiogram 215 cars 27–8, 155, 223–35 certainty factors 97 ceteris paribus preferences 262 chain reactions 242–3 chatbots 36 checkers 75–7 chess 163–4, 199 Chinese room 311–14 choice under uncertainty 152–3 combinatorial explosion 74, 80–1 common values and norms 260 common-sense reasoning 121–3 see also reasoning COMPAS 280 complexity barrier 77–85 comprehension 38–41 computational complexity 77–85 computational effort 129 computers – decision making 23–4 – early developments 20 – as electronic brains 20–4 – intelligence 21–2 – programming 21–2 – reliability 23 – speed of 23 – tasks for 24–8 – unsolved problems 28 ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’ (Turing) 32 confirmation bias 295 conscious machines 327–30 consciousness 305–10, 314–17, 331–4 consensus reality 296–8 consequentialist theories 249 contradictions 122–3 conventional warfare 286 credit assignment problem 173, 196 Criado Perez, Caroline 291–2 crime 277–81 Cruise Automation 232 curse of dimensionality 172 cutlery 261 Cybernetics (Wiener) 29 Cyc 114–21, 208 D DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) 87–8, 225–6 Dartmouth summer school 1955 50–2 decidable problems 78–9 decision problems 15–19 deduction 106 deep learning 168, 184–90, 208 DeepBlue 163–4 DeepFakes 297–8 DeepMind 167–8, 190–200, 220–1, 327–8 Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) 87–8, 225–6 dementia 219 DENDRAL 98 Dennett, Daniel 319–25 depth-first search 74–5 design stance 320–1 desktop computers 145 diagnosis 220–1 disengagements 231 diversity 290–3 ‘divide and conquer’ assumption 53–6, 128 Do-Much-More 35–6 dot-com bubble 148–9 Dreyfus, Hubert 85–6, 311 driverless cars 27–8, 155, 223–35 drones 282–4 Dunbar, Robin 317–19 Dunbar’s number 318 E ECAI (European Conference on AI) 209–10 electronic brains 20–4 see also computers ELIZA 32–4, 36, 63 employment 264–77 ENIAC 20 Entscheidungsproblem 15–19 epiphenomenalism 316 error correction procedures 180 ethical AI 246–62, 284, 285 European Conference on AI (ECAI) 209–10 evolutionary development 331–3 evolutionary theory 316 exclusive OR (XOR) 180 expected utility 153 expert systems 89–94, 123 see also Cyc; DENDRAL; MYCIN; R1/XCON eye scans 220–1 F Facebook 237 facial recognition 27 fake AI 298–301 fake news 293–8 fake pictures of people 214 Fantasia 261 feature extraction 171–2 feedback 172–3 Ferranti Mark 1 20 Fifth Generation Computer Systems Project 113–14 first-order logic 107 Ford 232 forward chaining 94 Frey, Carl 268–70 ‘The Future of Employment’ (Frey & Osborne) 268–70 G game theory 161–2 game-playing 26 Gangs Matrix 280 gender stereotypes 292–3 General AI 41, 53, 116, 119–20 General Motors 232 Genghis robot 134–6 gig economy 275 globalization 267 Go 73–4, 196–9 Golden Age of AI 47–88 Google 167, 231, 256–7 Google Glass 296–7 Google Translate 205–8, 292–3 GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) 187–8 gradient descent 183 Grand Challenges 2004/5 225–6 graphical user interfaces (GUI) 144–5 Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) 187–8 GUI (graphical user interfaces) 144–5 H hard problem of consciousness 314–17 hard problems 84, 86–7 Harm Assessment Risk Tool (HART) 277–80 Hawking, Stephen 238 healthcare 215–23 Herschel, John 304–6 Herzberg, Elaine 230 heuristic search 75–7, 164 heuristics 91 higher-order intentional reasoning 323–4, 328 high-level programming languages 144 Hilbert, David 15–16 Hinton, Geoff 185–6, 221 HOMER 141–3, 146 homunculus problem 315 human brain 43, 306, 330–1 human intuition 311 human judgement 222 human rights 277–81 human-level intelligence 28–36, 241–3 ‘humans are special’ argument 310–11 I image classification 186–7 image-captioning 200–4 ImageNet 186–7 Imitation Game 30 In Search of Lost Time (Proust) 205–8 incentives 261 indistinguishability 30–1, 37, 38 Industrial Revolutions 265–7 inference engines 92–4 insurance 219–20 intelligence 21–2, 127–8, 200 – human-level 28–36, 241–3 ‘Intelligence Without Representation’ (Brooks) 129 Intelligent Knowledge-Based Systems 100 intentional reasoning 323–4, 328 intentional stance 321–7 intentional systems 321–2 internal mental phenomena 306–7 Internet chatbots 36 intuition 311 inverse reinforcement learning 262 Invisible Women (Criado Perez) 291–2 J Japan 113–14 judgement 222 K Kasparov, Garry 163 knowledge bases 92–4 knowledge elicitation problem 123 knowledge graph 120–1 Knowledge Navigator 146–7 knowledge representation 91, 104, 129–30, 208 knowledge-based AI 89–123, 208 Kurzweil, Ray 239–40 L Lee Sedol 197–8 leisure 272 Lenat, Doug 114–21 lethal autonomous weapons 281–7 Lighthill Report 87–8 LISP 49, 99 Loebner Prize Competition 34–6 logic 104–7, 121–2 logic programming 111–14 logic-based AI 107–11, 130–2 M Mac computers 144–6 McCarthy, John 49–52, 107–8, 326–7 machine learning (ML) 27, 54–5, 168–74, 209–10, 287–9 machines with mental states 326–7 Macintosh computers 144–6 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 306 male-orientation 290–3 Manchester Baby computer 20, 24–6, 143–4 Manhattan Project 51 Marx, Karl 274–6 maximizing expected utility 154 Mercedes 231 Mickey Mouse 261 microprocessors 267–8, 271–2 military drones 282–4 mind modelling 42 mind-body problem 314–17 see also consciousness minimax search 76 mining industry 234 Minsky, Marvin 34, 52, 180 ML (machine learning) 27, 54–5, 168–74, 209–10, 287–9 Montezuma’s Revenge (video game) 195–6 Moore’s law 240 Moorfields Eye Hospital 220–1 moral agency 257–8 Moral Machines 251–3 MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) 306 multi-agent systems 160–2 multi-layer perceptrons 177, 180, 182 Musk, Elon 238 MYCIN 94–8, 217 N Nagel, Thomas 307–10 narrow AI 42 Nash, John Forbes Jr 50–1, 161 Nash equilibrium 161–2 natural languages 56 negative feedback 173 neural nets/neural networks 44, 168, 173–90, 369–72 neurons 174 Newell, Alan 52–3 norms 260 NP-complete problems 81–5, 164–5 nuclear energy 242–3 nuclear fusion 305 O ontological engineering 117 Osborne, Michael 268–70 P P vs NP problem 83 paperclips 261 Papert, Seymour 180 Parallel Distributed Processing (PDP) 182–4 Pepper 299 perception 54 perceptron models 174–81, 183 Perceptrons (Minsky & Papert) 180–1, 210 personal healthcare management 217–20 perverse instantiation 260–1 Phaedrus 315 physical stance 319–20 Plato 315 police 277–80 Pratt, Vaughan 117–19 preference relations 151 preferences 150–2, 154 privacy 219 problem solving and planning 55–6, 66–77, 128 programming 21–2 programming languages 144 PROLOG 112–14, 363–4 PROMETHEUS 224–5 protein folding 214 Proust, Marcel 205–8 Q qualia 306–7 QuickSort 26 R R1/XCON 98–9 radiology 215, 221 railway networks 259 RAND Corporation 51 rational decision making 150–5 reasoning 55–6, 121–3, 128–30, 137, 315–16, 323–4, 328 regulation of AI 243 reinforcement learning 172–3, 193, 195, 262 representation harm 288 responsibility 257–8 rewards 172–3, 196 robots – as autonomous weapons 284–5 – Baye’s theorem 157 – beliefs 108–10 – fake 299–300 – indistinguishability 38 – intentional stance 326–7 – SHAKEY 63–6 – Sophia 299–300 – Three Laws of Robotics 244–6 – trivial tasks 61 – vacuum cleaning 132–6 Rosenblatt, Frank 174–81 rules 91–2, 104, 359–62 Russia 261 Rutherford, Ernest (1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson) 242 S Sally-Anne tests 328–9, 330 Samuel, Arthur 75–7 SAT solvers 164–5 Saudi Arabia 299–300 scripts 100–2 search 26, 68–77, 164, 199 search trees 70–1 Searle, John 311–14 self-awareness 41, 305 see also consciousness semantic nets 102 sensors 54 SHAKEY the robot 63–6 SHRDLU 56–63 Simon, Herb 52–3, 86 the Singularity 239–43 The Singularity is Near (Kurzweil) 239 Siri 149, 298 Smith, Matt 201–4 smoking 173 social brain 317–19 see also brains social media 293–6 social reasoning 323, 324–5 social welfare 249 software agents 143–9 software bugs 258 Sophia 299–300 sorting 26 spoken word translation 27 STANLEY 226 STRIPS 65 strong AI 36–8, 41, 309–14 subsumption architecture 132–6 subsumption hierarchy 134 sun 304 supervised learning 169 syllogisms 105, 106 symbolic AI 42–3, 44, 181 synapses 174 Szilard, Leo 242 T tablet computers 146 team-building problem 78–81, 83 Terminator narrative of AI 237–9 Tesla 228–9 text recognition 169–71 Theory of Mind (ToM) 330 Three Laws of Robotics 244–6 TIMIT 292 ToM (Theory of Mind) 330 ToMnet 330 TouringMachines 139–41 Towers of Hanoi 67–72 training data 169–72, 288–9, 292 translation 204–8 transparency 258 travelling salesman problem 82–3 Trolley Problem 246–53 Trump, Donald 294 Turing, Alan 14–15, 17–19, 20, 24–6, 77–8 Turing Machines 18–19, 21 Turing test 29–38 U Uber 168, 230 uncertainty 97–8, 155–8 undecidable problems 19, 78 understanding 201–4, 312–14 unemployment 264–77 unintended consequences 263 universal basic income 272–3 Universal Turing Machines 18, 19 Upanishads 315 Urban Challenge 2007 226–7 utilitarianism 249 utilities 151–4 utopians 271 V vacuum cleaning robots 132–6 values and norms 260 video games 192–6, 327–8 virtue ethics 250 Von Neumann and Morgenstern model 150–5 Von Neumann architecture 20 W warfare 285–6 WARPLAN 113 Waymo 231, 232–3 weak AI 36–8 weapons 281–7 wearable technology 217–20 web search 148–9 Weizenbaum, Joseph 32–4 Winograd schemas 39–40 working memory 92 X XOR (exclusive OR) 180 Z Z3 computer 19–20 PELICAN BOOKS Economics: The User’s Guide Ha-Joon Chang Human Evolution Robin Dunbar Revolutionary Russia: 1891–1991 Orlando Figes The Domesticated Brain Bruce Hood Greek and Roman Political Ideas Melissa Lane Classical Literature Richard Jenkyns Who Governs Britain?

Machines of Loving Grace: The Quest for Common Ground Between Humans and Robots

by

John Markoff

Published 24 Aug 2015

Today, of course, the Walkmans have been replaced by Apple’s iconic bright white iPhone headphones, and there are some who believe that technology haute couture will inevitably lead to a future version of Google Glass—the search engine maker’s first effort to augment reality—or perhaps more ambitious and immersive systems. Like the frog in the pot, we have been desensitized to the changes wrought by the rapid increase and proliferation of information technology. The Walkman, the iPhone, and Google Glass all prefigure a world where the line between what is human and who is machine begins to blur. William Gibson’s Neuromancer, the science-fiction novel that popularized the idea of cyberspace, drew a portrait of a new cybernetic territory composed of computers and networks.

…

It also painted a future in which computers were not discrete boxes, but would be woven together into a dense fabric that was increasingly wrapped around human beings, “augmenting” their senses. It is not such a big leap to move from the early-morning commuters wearing Sony Walkman headsets, past the iPhone users wrapped in their personal sound bubbles, directly to Google Glass–wearing urban hipsters watching tiny displays that annotate the world around them. They aren’t yet “jacked into the net,” as Gibson foresaw, but it is easy to assume that computing and communication technology is moving rapidly in that direction. Gibson was early to offer a science-fiction vision of what has been called “intelligence augmentation.”

…

He secretly set up a laboratory modeled vaguely on Xerox PARC, the legendary computer science laboratory that was the birthplace of the modern personal computer, early computer networks, and the laser printer, creating projects in autonomous cars and reinventing mobile computing. Among other projects, he helped launch Google Glass, which was an effort to build computing capabilities including vision and speech into ordinary glasses. Unlike laboratories of the previous era that emphasized basic science, such as IBM Research and Bell Labs, Google’s X Lab was closer in style to PARC, which had been established to vault the copier giant, restyled “the Document Company,” into the computer industry—to compete directly with IBM.

How to Build a Billion Dollar App: Discover the Secrets of the Most Successful Entrepreneurs of Our Time

by

George Berkowski

Published 3 Sep 2014

While the media and blogosphere speculate about a vastly superior ‘iWatch’ in the offing from Apple – one that will incorporate all kinds of clever non-invasive sensors that may measure all kinds of things, including heart rate, oxygen saturation, perspiration and blood sugar levels in addition to the already commonplace step- and calorie-measuring sensors – other companies are already profiting from wearable technology. The fitness-bracelet market – where devices like Fitbit, Nike’s Fuelband and the Jawbone Up lead the market – delivered $2 billion in revenue in 2013. And that number is expected to triple by 2015.29 But all those technologies pale in comparison with one. Say hello (or OK) to Google Glass. Google Glass is 63 grams of hardware – a modern-looking set of glass frames (without lenses) sporting a microdisplay that projects an interface (which appears as a floating 27-inch display) into your field of vision. Think of it as an advanced – and heavily miniaturised – version of the Heads Up Display (HUD) systems that fighter pilots use.

…

It was just a matter of years. When the next technology cycle begins – and it will undoubtedly be something more wearable – it will begin with huge swathes of the ecosystem already in place. The time to get 1 billion active users of a gizmo like Google Glass will be a lot shorter than the eight years it took the smartphone to smash that milestone. While Google Glass has received a lot of attention because of Google’s profile, another equally fascinating, and potentially even more disruptive, technology company has captured headline. It is called Oculus VR and it might just be the first company to bring virtual reality to the masses.

…

What was once a heavy screen confined to the desktop became a smaller screen able to be carried in your pocket, which will now become a screen and voice-control system so light – 63 grams – that you barely notice you’re wearing or carrying it. And it gets spookier. There are projects under way that will enable features like Google Glass to be packed into a contact lens.30 The implications of such an unobtrusive – and powerful – interface are simply jaw-dropping. If we go back to the beginning of the last technology cycle – that of the smartphone, kicked off by the iPhone in 2007 – we can see how quickly a touchscreen interface, a powerful operating system, integrated sensors and a ubiquitous mobile Internet connection changed our lives.

The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty

by

Benjamin H. Bratton

Published 19 Feb 2016

Hugo De Garis, The Artilect War: Cosmists vs. Terrans: A Bitter Controversy Concerning Whether Humanity Should Build Godlike Massively Intelligent Machines (Palm Springs, CA: ETC Publications, 2005). 72. Gigi Fenomen, “New App Allows Piloting a Drone with Google Glass Using Head Movements,” Android Apps, August 24, 2013, http://android-apps.com/news/new-app-allows-piloting-a-drone-with-google-glass-using-head-movements/. 73. Let me propose that Philip K. Dick's novel A Scanner Darkly (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1977), should be part of the standard high school literature curriculum, if only because the existential psychology of the User will prove to be based on first-person access to third-person experiences of first-person experiences. 74.

…

See also Earth artificial megastructures, 176–183 constitutional, 111 defined, 371 economic, 199 essential importance of, 149 exceptional or unregularized, 30 informational, 29 Internet, 361 of jurisdiction, 171–176, 283, 308–309, 323 of multiple geographies, 245–246 politico-theological, 242, 248, 320–322 of The Stack, sovereignty over, 33 superimposition of the addressing matrix, 193 telescoping, 16, 101, 178, 197, 220, 229, 235, 266 geolocated augmented reality, 438n60 geolocative advertising, 255 geolocative Apps, 236, 243 geometrics, 90–91, 309 geometry of territory, 25 geophilosophy (Deleuze and Guattari), 372 geopolitical architecture designed, 38 of Earth layer, 98, 300–302 European, 27 new, need for, 3, 300–302 unipolar, future of, 309–310 geopolitical conflict Google-China, 9, 112–115, 143–144, 245, 361 historical, 6 Nicaragua-Costa Rica border, 9, 120, 144 present-day, 6 geopolitical domains, 118–119 geopolitical geography, 4–5, 19, 33, 65, 252 of borders, 6–7, 97, 172–173, 308–310, 323, 409n42 of conflict, 6, 9, 112–115, 120, 143–144, 245, 361 design model, 3–6 energy driving alignments in, 141 European nomos, 25–26 future-antecedent revision of, 14–17 geometry of, 13–17 loop topology of, 84 mapping, 4–5 of planetary-scale computation, 14–17, 143 TBIT controversy, 174–176 geopolitical theory, 328 geopolitics, 19, 39–40, 257–258, 326, 360 of addressability, 193, 207–208 of addresses, 193–194 algorithmic, 449n56 City layer, 155, 160, 444n26 of climate change, 140–141 Cloud layer, 110–112, 114, 454n75 within comparative planetology, 353 compositional, 85 computational, 360 defined, 371–372 design, 119, 141–145 elements of, 246–247 as epidermal, 355 framework, 159 geoscopy and, 85 Google model, 125, 134–136 of interfaciality, 228 modern, basis of, 24 post-Anthropocenic, 285 of postscarcity, 95 projection as territory/territory as projection, 85 spacelessness of contemporary, 30 space of, 6 geoscapes, 243–249, 372, 429n61 geoscopy, 85, 87, 89–90 geotheological innovation, 242–243 Germany, 309 Gershenfeld, Neil, 226 ghost sovereignties, 100–101 gift economy, 429n59 GigaOM, 186 Girard, Rene, 360 global assemblages, 265–266 global citizenship, basis of, 257 global commons, 35–36 global infrastructure, 139–140 globalization fundamentalism and, 143 individual experience of, 270 infrastructure, 45, 110 international system of control in, 443n23 of postal domains, 194 of risk, 321 software-driven, 348 spatial warfare of, 431n70 twentieth-century, Schmitt's view of, 31–32 of urban geography, 151 globally unique identifier (GUI), 168, 207, 254 global society, Anthropocenic, 106 global urban, 177–179 global visualizations, 265–266 Göbekli Tepe, 149, 176, 188 Godard, Jean-Luc, 147, 158 gold, 82, 104, 336 gold standard, 199, 336 goods and services, quality of, 313 Google advertising infrastructure, 137 algorithmic methods, 332 architectural footprint, 184–185 AR game, 241–242 Cloud Polis, 132, 134–141, 184–185, 187–188, 332 conflict with China, 9, 112–115, 143–144, 245, 361 cosmopolitan logic of, 322 economic sovereignty, 122 Facebook compared, 126 future of, 129, 141–142 geographic strategy, 9, 120, 144 geopolitical model, 125, 134–136 Grossraum, 34–40, 134, 295, 318, 372 infrastructure, physical, 10–11, 113 Interface joke, 332 interfacial regime, 247 mission statement, 87, 122, 134, 138, 186, 353, 396n10 as monopoly, 400n41 nation-state functions, 10–11 Nest, purchase of, 134 network architecture, 118–119 Nortel patent bid, 134 oceanic data centers, 140 OpenFlow's advantages to, 437n58 platform universality, 332 political theology of, 425n46 proto-citizenship, 122 revenue stream, 136–138, 159, 444n26 search infrastructure, 136–138 shutting down access to, 403n63 synthetic catallaxy, 331 territorial footprint, 113 US-centricity, 135 Google AdWords, 255 Google AI, 134 Google bashing, 402n62 Google Car, 129, 134, 139, 281–282, 344, 437n55, 437n57. See also cars: driverless Google charter cities, 352 Google City, 444n26 Googledome, 184 Google Earth, 86, 91, 134, 242, 247–248, 322, 391n30, 431n70 Google Earth RealTime, 299–300 Google Energy, 134, 140 Google Fiber, 399n31 Google Glass, 129, 134, 282, 308, 381n30, 438n60 Google Glass App, 288 Google Gosplan, 328, 332, 363–364, 372 Google ID, 295 Google Ideas, 134, 361 Google Island, 315 Google Maps, 9, 120, 144, 242, 265, 431n70 Googleplex, 183–185 Google Public DNS, 136 Google Robotics, 134, 138–139 Google Sovereignty, 134 Google Space, 134 Google Time, 134 Google 2.0, 184–185 Google Wallet, 127 Google: Words Beyond Grammar (Groys), 239 Google World, 134–135 gorilla populations, 82–83 Gosplan Google, 328, 332, 363–364, 372 Soviet, 59, 138, 329 governance of addresses, 198–199 Address layer, 196 algorithmic, 134, 332–334, 337–338, 341–342, 348, 368 apparatus of, 173–174 Cloud layer, 68, 140, 143 of Cloud Polis, 113–114 computational, 90, 97, 112, 327 cybernetic, 341 ecological, 88–90, 97–106 economic, 329–330 geographic, modes of, 27 of interfaces, 325 Internet, 143 intervention versus interfaciality in, 227–228 machine of, 173–174 of the market, 329–330 meaning of, 327 new forms of, 5, 119, 260 new war over, 10–11 Obama-era infrastructuralism, 180–181 object of, 357, 454n75 of platforms, 143 spatial, 163 technologies of, 7–8 training by computation, 90 of urban interfaces, 155–157, 163, 326 of urban platforms, 326 of the User, 49, 159 governmentality, 7–8, 327 government layer, 396n12 Graeber, David, 443n23 Grand Canyon AR overlay, 242 graphical user interface (GUI).

…

Typical of this perspective is Jean-Luc Nancy, The Creation of the World, or Globalization (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2002). 40. A particularly egregious example is Franco “Bifo” Berardi's missive, Neuro-Totalitarianism in Technomaya Goog-Colonization of the Experience and Neuro-Plastic Alternative (Los Angeles: Semtiotext(e), and New York: Whitney Museum, 2014). His target is Google Glass, a piece of hardware that takes on black magic powers in his estimation. In the Interfaces chapter, I will discuss the dangers of augmented reality-based interfacial totalities to engender forms of cognitive totalitarianism, but this is not because they train attention on artificial images, negating our natural faculties of reason and experience (see also the Phaedrus, and Socrates’ admonitions against the written word, 370 B.C., or the whole history of experimental cinema).

Augmented: Life in the Smart Lane

by

Brett King

Published 5 May 2016

Whether from Continuum, Iron Man, Batman, Deus Ex or the modern-day F22 Raptor fighter jet, the concept of an augmented, head-up display (HUD)12 vision has been a staple of science fiction and military aircraft for more than 50 years. When Google Glass launched in 2013, it launched to great media fanfare.13 Glass was considered the next big leap in both wearable technologies and augmented reality (AR), but as with all such leaps in technology it was met with either unyielding passion or mild derision. In media context, however, Google’s first head-up display wearable fit neither the traditional definition of HUD nor immersive AR. It is clearly just a first step in the evolution of enhanced vision overlay. I know that some of you will be thinking that you’ll never wear something like Google Glass, that you’ll never be one of those “glassholes”, as social media coined the moniker.

…

Longer term understanding of the evolution of interface design, embedded computing and interaction science lead us to the inevitable conclusion that apps will become less and less important over time. That summer, Google made an eight-pound prototype of a computer meant to be worn on the face. To Ive, then unaware of Google’s plans, “the obvious and right place” for such a thing was the wrist. When he later saw Google Glass, Ive said, it was evident to him that the face “was the wrong place.” [Tim Cook, Apple’s C.E.O.] said, “We always thought that glasses were not a smart move, from a point of view that people would not really want to wear them. They were intrusive, instead of pushing technology to the background, as we’ve always believed.”

…

Today, we’re already getting a little overwhelmed by the volume of notifications, application feedback and offers. Do we really need this sort of data interrupting our field of vision while we’re driving, walking into a shop or working on a document at the office? Whether delivered by a next-gen Google Glass or a smart contact lens, context is going to be the single key driver to the applicability of information augmenting our field of vision. The information that will be delivered via head-up display implementation needs to be super personalised, and highly contextual. Such information will normally be short-lived, and only there to enhance decision-making in the moment, so by nature will have to be backed by some incredibly sophisticated preprocessing algorithms.

Dragnet Nation: A Quest for Privacy, Security, and Freedom in a World of Relentless Surveillance

by

Julia Angwin

Published 25 Feb 2014

During the sentencing, the judge said, “This was nothing short of a sustained effort to terrorize victims.” Mijangos was sentenced to six years in prison. And widespread camera dragnets are right around the corner. The arrival of wearable computers equipped with cameras, such as Google Glass, means that everything is fair game for filming. The New York Times columnist Nick Bilton was shocked when he attended a Google conference and saw attendees wearing their Google Glass cameras while using the urinals. But Google Glass enthusiasts say that wearing cameras on their heads changes their life. “I will never live a day of my life from now on without it (or a competitor),” wrote the blogger Robert Scoble after trying out the glasses for two weeks.

…

Marketers and data brokers increasingly trade information on real-time trading desks that mimic stock exchanges. INDIVIDUALS • Democratized dragnets. Technology has become cheap enough that everyone can do their own tracking, with items such as dashboard cameras, build-it-yourself drones, and Google Glass eyeglasses that contain tiny cameras that can take photos and videos. The trackers are deeply intertwined. Government data are the lifeblood for commercial data brokers. And government dragnets rely on obtaining information from the private sector. Consider just one example: voting. To register to vote, citizens must fill out a government form that usually requires their name, address, and, in all but one state, birth date.

…

The New York Times columnist Nick Bilton: Nick Bilton, “At Google Conference, Cameras Even in the Bathroom,” Bits (blog), New York Times, May 17, 2013, http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/17/at-google-conference-even-cameras-in-the-bathroom/. “I will never live a day … without it”: Robert Scoble, “My Two-Week Review of Google Glass,” Google+ post, April 27, 2013, https://plus.google.com/+Scobleizer/posts/ZLV9GdmkRzS. Bobbi Duncan, a twenty-two-year-old lesbian student: Geoffrey A. Fowler, “When the Most Personal Secrets Get Outed on Facebook,” Wall Street Journal, October 13, 2012, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390444165804578008740578200224.html.

Bit Rot

by

Douglas Coupland

Published 4 Oct 2016

It’s like that old skit where the waiter introduces you to several cows and you get to choose which one will be used for the evening’s steak, but instead it’s McDonald’s, and they’re out to prove they no longer use pink goo in their burgers. Creep is seeing someone wearing Google glasses—one of the cofactors that led to the device being withdrawn from the market until future iterations remove its creep. The Onion had a wonderful headline the week the glasses were removed from public sale until further notice: “Unsold Google Glass Units to Be Donated to Assholes in Africa.” You’d think that de-creeping Google Glass might be difficult, but in the end it’s probably just a numbers game. I remember seeing early adopters using cellphones on city sidewalks in Toronto between 1988 and 1990, and they looked like total assholes—they just did in a way that people born later find very hard to believe.

…

Then text comes up telling you how many steps you took that day, also telling you the farthest point you were away from home, and then something NSFW appears onscreen—and then suddenly you’re inside a mesh model of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, which lands you in the middle of a scene from The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, a scene on a tennis court. A crawl at the bottom of the screen reminds you that Wimbledon starts in a week. The screen fades to white and a montage of products appears, but it’s not advertising…it’s all the logos you walked past today while wearing Google glasses. The music cuts to the soundtrack of Days of Heaven while the screen cuts up into nine squares, each displaying a kitten video. A male voice reads passages from Lolita (you haven’t thought of that book in ages!) while the screen now shows footage from a 1974 Partridge Family episode. Then we see scenes from your office life, except they’re in slow motion, and then they’re melting into… And so forth.

…

yoo…in a bit more detail: yoo takes images, sounds and text from the course of your day (or week or year) and weaves them together so that they morph, jumpcut and dissolve. yoo seeks and blends into your experience the faces, spaces, audio feeds and experiences of all the people in your life, imported from various streams. yoo options are multiplied with Google Glass, which pick up images and sounds throughout the day—details that you didn’t notice but still registered in your subconscious. yoo adds and weaves in fragments of movies, songs or other media you experienced that week—but does so by displaying similar or related content: cover versions of favourite songs; movies by the same director; movies with similar plots.

The Internet of Us: Knowing More and Understanding Less in the Age of Big Data

by

Michael P. Lynch

Published 21 Mar 2016

See also “Recovering Under-standing.” 3. Kitcher, Abusing Science. 47–49. I don’t mean to suggest that Kitcher would embrace my views on understanding, however. 4. Lazer et al., “The Parable of Google Flu.” 5. Solzhenitsyn, Cancer Ward, 192. 6. Pete Pachal, “Google Glass Will Have Automatic Picture-Taking Mode,” Mashable, July 25, 2012. Available at http://mashable.com/2012/07/25/google-glass-photo-mode/#SI4XL.9XkOqI. Accessed September 4, 2015 Bibliography Achinstein, Peter. The Nature of Explanation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983. Bilton, Nick. I Live in the Future & Here’s How It Works: Why Your World, Work, and Brain Are Being Creatively Disrupted.

…

As Bertrand Russell once remarked in a somewhat different context, advances in technology never seem to bring along with them—at least, all by themselves—a change in humanity’s penchant for greed and power. That is a lesson I hope we heed—even while we look forward to the benefits the Internet of Us will bring. Many of us share the same concerns. After the initial launch of Google Glass, the reaction was more negative than expected. While many were excited about the technology, it seemed that just as many were worried about its potential for invading privacy; others were concerned about its potential for distracting drivers. These practical objections were serious. But I can’t help wondering if the concern went deeper.

…