Gregor Mendel

description: Silesian scientist and Augustinian friar (1822–1884)

122 results

Keeping Up With the Quants: Your Guide to Understanding and Using Analytics

by

Thomas H. Davenport

and

Jinho Kim

Published 10 Jun 2013

Nuttall, “The Passionate Statistician,” Nursing Times 28 (1983): 25–27. 5. Gregor Mendel, “Experiments in Plant Hybridization,” http://www.mendelweb.org/; “Gregor Mendel,” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregor_Mendel; Seung Yon Rhee, Gregor Mendel, Access Excellence, http://www.accessexcellence.org/RC/AB/BC/Gregor_Mendel.php; “Mendel’s Genetics,” anthro.palomar.edu/mendel/mendel_1.htm; David Paterson, “Gregor Mendel,” www .zephyrus.co.uk/gregormendel.html; “Rocky Road: Gregor Mendel,” Strange Science, www.strangescience.net/mendel.htm; Wolf-Ekkehard Lönnig, “Johann Gregor Mendel: Why His Discoveries Were Ignored for 35 Years,” www.weloennig .de/mendel02.htm; “Gregor Mendel and the Scientific Milieu of His Discovery,” www.2iceshs.cyfronet.pl/2ICESHS_Proceedings/Chapter_10/R-2_Sekerak.pdf; “Mendelian Inheritance,” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mendelian_ inheritance. 6.

…

FIGURE 4-1 * * * Florence Nightingale’s diagram of the causes of mortality in the “Army in the East” The Areas of the blue, red, & black wedges are each measured from the centre as the common vertex The blue wedges measured from the centre of the circle represent area for area the deaths from Preventible or Mitigable Zymotic Diseases, the red wedges measured from the centre the deaths from wounds, & the black wedges measured from the centre the deaths from all other causes The black line across the red triangle in Nov 1854 marks the boundary of the deaths from all other causes during the month In October 1854, & April 1855, the black area coincides with the red, in January & February 1856, the blue coincides with the black The entire areas may be compared by following the blue, the red, & the black lines enclosing them * * * Nightingale became a Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society in 1859—the first woman to become a member—and an honorary member of the American Statistical Association in 1874. Karl Pearson, a famous statistician and the founder of the world’s first university statistics department, acknowledged Nightingale as a “prophetess” in the development of applied statistics.4 Gregor Mendel: A Poor Example of Communicating Results For a less impressive example of communicating results—and a reminder of how important the topic is—consider the work of Gregor Mendel.5 Mendel, the father of the concept of genetic inheritance, said a few months before his death in 1884 that, “My scientific studies have afforded me great gratification; and I am convinced that it will not be long before the whole world acknowledges the results of my work.”

…

Gregor Mendel, “Experiments in Plant Hybridization,” http://www.mendelweb.org/; “Gregor Mendel,” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregor_Mendel; Seung Yon Rhee, Gregor Mendel, Access Excellence, http://www.accessexcellence.org/RC/AB/BC/Gregor_Mendel.php; “Mendel’s Genetics,” anthro.palomar.edu/mendel/mendel_1.htm; David Paterson, “Gregor Mendel,” www .zephyrus.co.uk/gregormendel.html; “Rocky Road: Gregor Mendel,” Strange Science, www.strangescience.net/mendel.htm; Wolf-Ekkehard Lönnig, “Johann Gregor Mendel: Why His Discoveries Were Ignored for 35 Years,” www.weloennig .de/mendel02.htm; “Gregor Mendel and the Scientific Milieu of His Discovery,” www.2iceshs.cyfronet.pl/2ICESHS_Proceedings/Chapter_10/R-2_Sekerak.pdf; “Mendelian Inheritance,” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mendelian_ inheritance. 6. This list was adapted and modified from one on the IBM ManyEyes site; see http://www-958.ibm.com/software/data/cognos/manyeyes/page/Visualization_Options.html. 7. This example is from the SAS Visual Analytics 5.1 User’s Guide, “Working with Automatic Charts,” http://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/vaug/65384/ HTML/default/viewer.htm#n1xa25dv4fiyz6n1etsfkbz75ai0.htm. 8.

The Gene: An Intimate History

by

Siddhartha Mukherjee

Published 16 May 2016

In October 1843, a young man from Silesia: Details of Mendel’s life and the Augustinian monastery are from several sources, including Gregor Mendel, Alain F. Corcos, and Floyd V. Monaghan, Gregor Mendel’s Experiments on Plant Hybrids: A Guided Study (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1993); Edward Edelson, Gregor Mendel: And the Roots of Genetics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999); and Robin Marantz Henig, The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, the Father of Genetics (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000). The tumult of 1848: Edward Berenson, Populist Religion and Left-Wing Politics in France, 1830–1852 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984).

…

Darwin’s theory of evolution by variation and natural selection demanded a theory of heredity via genes. Close readers of Darwin’s theory realized that evolution could work only if there were indivisible, but mutable, particles of heredity that transmit information between parents and offspring. Yet Darwin, having never read Gregor Mendel’s paper, never found an adequate formulation of such a theory during his lifetime. Gregor Mendel holds a flower, possibly from a pea plant, in his monastery garden in Brno (now in the Czech Republic). Mendel’s seminal experiments in the 1850s and ’60s identified indivisible particles of information as carriers of hereditary information. Mendel’s paper (1865) was largely ignored for four decades, and then transformed the science of biology.

…

he made extensive handwritten notes on pages 50, 51, 53, and 54: David Galton, “Did Darwin read Mendel?” Quarterly Journal of Medicine 102, no. 8 (2009): 588, doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcp024. “Flowers He Loved” “Flowers He Loved”: Edward Edelson, Gregor Mendel and the Roots of Genetics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), “Clemens Janetchek’s Poem Describing Mendel after His Death,” 75. “We want only to disclose the [nature of] matter and its force”: Jiri Sekerak, “Gregor Mendel and the scientific milieu of his discovery,” ed. M. Kokowski (The Global and the Local: The History of Science and the Cultural Integration of Europe, Proceedings of the 2nd ICESHS, Cracow, Poland, September 6–9, 2006).

A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived

by

Adam Rutherford

Published 7 Sep 2016

Since 1953, we’ve known that the double helix is how DNA is built, giving it the impressive ability to copy itself and allow those copies to build cells just like the ones they came from. And since the 1960s we’ve known how DNA encodes proteins, and that all life is built of, or by, proteins. Those titans of science, Gregor Mendel, Francis Crick, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins, stood on their predecessors’ and colleagues’ shoulders, and would in turn be the giants from whose shoulders all biologists would see into the future. The unravelling of these mysteries were the great science stories of the twentieth century, and by the beginning of the twenty-first the principles of biology were set in place.

…

Darwin invented evolutionary biology; Galton founded and formalized many aspects of the biological study of humans. They both worked at a time when great leaps were being made in the study of life, which would lead to further unifying theories of biology. The great nineteenth-century Moravian scientist17 Gregor Mendel’s work from exactly the same mid-century time, though ignored until the beginning of the twentieth century, described the rules of inheritance – how characteristics pass down the generations from two parents to one child. In the first few decades of the twentieth century, primarily at UCL, a new breed of biology emerged which combined statistics and Darwin, and formalized the mechanism by which evolution by natural selection occurs.

…

As discussed, even the most genetically straightforward diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, are mitigated by a host of other factors buzzing around inside our genes, cells, and outside our bodies. Inheritance is a game of probability, not of destiny. It’s not just the headline writer’s fault though. The history of science is clearly to blame too. Recall Gregor Mendel, who gave us the rules of inheritance by studying individual characteristics in pea plants. Through the twentieth century we beavered away at the laws of inheritance, and unravelled DNA, and cracked the genetic code. In the 1980s, the first disease genes that we identified were indeed ‘for’ specific diseases, cystic fibrosis, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Huntington’s.

Too Big to Know: Rethinking Knowledge Now That the Facts Aren't the Facts, Experts Are Everywhere, and the Smartest Person in the Room Is the Room

by

David Weinberger

Published 14 Jul 2011

He supported his scientific work through his travel writings, and later in his life through an inheritance from his father. He was, however, well integrated into the community of scientists, and was a member of scientific organizations such as the Royal Zoological Society, the Royal Society, and the Linnean Society. Gregor Mendel was at a whole other level of amateurism. Unable to pass the qualifying exams to teach high school students, he worked for years in his monastery’s garden, observing the peculiarities of generations of smooth and wrinkled peas. Today Mendel’s name is almost always followed by the phrase “the father of genetics.”

…

Today Mendel’s name is almost always followed by the phrase “the father of genetics.” During his lifetime, however, he was unrecognized and uninvolved in either the profession or the community of science. Science has a long tradition of embracing amateurs. After all, truth is truth, no matter who utters it. On the other hand, if the manuscript Gregor Mendel sent Charles Darwin had been marked as coming from a prestigious university, Darwin might have cut the folded pages and read it.19 If the self-taught math genius Srinivasa Ramanujan had not written to three Cambridge professors in 1912–1913, his lifetime of work—including the “Ramanujan Conjecture”—might have vanished without impact.

…

See also the exceptional RadioLab program on this topic: “Limits of Science,” April 16, 2010, http://www.wnyc.org/shows/radiolab/episodes/2010/04/16/segments/149570. 18 Nicholas Taleb Nassim, The Black Swan (Random House, 2007). 19 The story may be apocryphal, according to a report by Nicholas Wade in “A Family Feud over Mendel’s Manuscript on the Laws of Heredity,” May 31, 2010, http://philosophyofscienceportal.blogspot.com/2010/06/gregor-mendel-and-pea-breeding.html. 20 Jennifer Laing, “Comet Hunter,” Universe Today, December 11, 2001, http://www.universetoday.com/html/articles/2001–1211a.html. 21 Jennifer Ouellette, “Astronomy’s Amateurs a Boon for Science,” Discovery News, September 20, 2010, http://news.discovery.com/space/astronomys-amateurs-a-boon-for-science.html. 22 Mark Frauenfelder, “The Return of Amateur Science,” Boing Boing, December 22, 2008, http://www.good.is/post/the-return-of-amateur-science/. 23 Thanks to the people who responded to the request for examples I posted on my Web site: Garrett Coakley, Jeremy Price, Miriam Simun, Andrew Weinberger, Jim Richardson, and Lars Ludwig.

Abundance

by

Ezra Klein

and

Derek Thompson

Published 18 Mar 2025

Element 117, tennessine, was discovered only when a Tennessee laboratory created an isotope of the rare metal berkelium and sent twenty-two milligrams of the radioactive material to Russia, where a separate group of scientists at a nuclear research facility hit it with a beam of 6 trillion calcium ions per second for 150 days and used specialized equipment to detect the faintest whispers of tennessine flickering into existence for less than a second.45 While it’s hard to say how the next synthetic element will be detected, it is safe to assume that it will not be discovered in a pot of hot urine. If that example seems a little goofy, try this one. The godfather of genetics was Gregor Mendel. A Czech friar in the mid-1800s, Mendel grew peas of varying shape, color, and flower position in his monastery’s garden. He bred the pea plants by cross-pollination over generations and noticed that peas seemed to pass down their traits, producing predictable crossbreeds. Although his 1866 analysis46 was published to little fanfare, a group of botanists later rediscovered Mendel’s work, independently confirmed the principles of inheritance, and cracked open the field of genetics.

…

Such research—called genome-wide association studies—takes hundreds of geneticists, neuroscientists, computer programmers, assistants, and more working together in organized teams over many years to get us one small step closer to solving the riddle of schizophrenia. It is absurd to imagine that one person, even as brilliant as Gregor Mendel, could do all this alone in his backyard. That is Jones’s point in a nutshell. Scientific progress is a blessing that comes with a curse. The unsolved problems are typically harder than the solved ones. * * * If keeping up the pace of scientific progress demands more resources, it points to a clear solution: recruit more scientists and spend more money.

…

Oak Ridge National Laboratory, “Big Science: The Discovery of Tennessine,” January 27, 2017, https://www.ornl.gov/sites/default/files/Ts_Program%20Final%20sm.pdf; Periodic Table, Tennessine, Element Summary, 3. History, National Institutes of Health, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/element/Tennessine#section=Estimated-Oceanic-Abundance; Scott Alexander, “Is Science Slowing Down?,” Slate Star Codex (blog), November 26, 2018, https://slatestarcodex.com/2018/11/26/is-science-slowing-down-2/. 46. Gregor Mendel, “Versuche über Plflanzenhybriden,” Verhandlungen des Naturforschenden Vereines in Brünn 5 (1865): 3–47. Presented orally at the February 8 and March 8, 1865, meetings of the Brünn Natural History Society. Published in 1866, Brünn, Czechoslovakia, by Verlag des Vereines. Biodiversity Heritage Library, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/124139#page/5/mode/1up.

The Big Ratchet: How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis

by

Ruth Defries

Published 8 Sep 2014

Agriculture: A Walk Through the Past and a Step into the New Millennium. National Agricultural Statistics Service, Washington, DC. Wallace, H., and W. Brown. 1988. Corn and Its Early Fathers, rev. ed. Iowa State University Press, Ames. Weiling, F. 1991. Historical study: Johan Gregor Mendel, 1822–1884. American Journal of Medical Genetics 40:1–25. Zirkle, C. 1951. Gregor Mendel and his precursors. Isis 42:97–104. Chapter 8: Competition for the Bounty Abate, T., A. van Huis, and J. Ampofo. 2000. Pest management strategies in traditional agriculture: An African perspective. Annual Reviews of Entomology 45:631–659. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 2002.

…

Darwin had hit upon the principle of hybrid vigor, the truth that offspring from parents of different varieties—whether corn, cows, or dogs—grow faster and are generally more robust and healthy than those bred from parents of the same variety. Only a few years after Darwin published On the Origin of Species, the devout Austrian monk Gregor Mendel began his eight-year experiment with the common pea in the monastery’s garden. Although he was a brilliant student, Mendel’s upbringing in a poor peasant family in what is now the Czech Republic had left him struggling to make ends meet while pursuing his studies. When he joined the priesthood, he was so shy and his health was so poor that he could not take on pastoral duties.

Epigenetics: How Environment Shapes Our Genes

by

Richard C. Francis

Published 14 May 2012

On any given day you could find at their labors two future Nobel prize laureates, as well as several other scientists who were to shape the course of genetics. First among them was the man who occupied the lone office, Thomas Hunt Morgan, whose significance in the history of genetics is second only to that of the Moravian monk Gregor Mendel.1 Morgan’s goal was to determine the location of Mendel’s “hereditary factors”—now called genes—on particular chromosomes. Morgan’s gene mapping was much different than today’s gene mapping. The technology was not then available to directly locate genes on chromosomes. Instead, he had to take a much more indirect route.

…

GR proteins, see glucocorticoid receptors GTRH, see gonadotropin releasing hormone guanine guinea pigs: domestication of genetic studies with stress biasing in hair color Harlow, Harry heart cells gene expression in heart disease, see cardiovascular disease Herodotus heterozygous alleles high blood pressure hinnies, see mules, hinnies hippocampus histones Hobbes, Thomas Holocaust, PTSD and homozygous alleles horbra hormones see also specific hormones housekeeping genes HPA programming, see stress biasing humans, protracted infancy and childhood of Huntington’s disease hybrid dysgenesis hybridization see also mules, hinnies hypomethylation see also methylation/demethylation hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, see stress axis hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis hypothalamus identical twins, see monozygotic twins IGF2 (insulin-like growth factor 2) IGF2 gene IGF2 inhibitor immune system cancer and self-nonself distinction in imprinting, genomic active vs. inactive alleles in disruptions in effect of environmental toxins on maternal origin and methylation in parent-of-origin effect in paternal origin and transgenerational effects of imprinting control regions (ICRs) Indian Ocean tsunami (2004) induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) inheritance: epigenetic processes in see also epigenetic inheritance; imprinting, genomic; social inheritance injury repair, cellular dedifferentiation in intracisternal A particle (IAP) introns Inuits Janus metaphor Juiced (Canseco) Just, Ernest Everett Kallmann syndrome, ix–xi kangaroos, see marsupials Katrina, Hurricane Kentucky Fried Chicken kidney disease kidneys: gene expression in melanin production in Kit gene La Russa, Tony lethal yellow (AL) agouti allele leukemia Leviathan (Hobbes) lick grooming, stress biasing and life expectancy: birth weight and stress biasing and ligers limbic system Lin, Maya lin-4 Linnaeus, Carl lipids liver: gene expression in GR expression in melanin production in locus, loci, of genes lung disease lupus Lyon, Mary male mammals, effects of endocrine disruptors in mammals, regeneration in Marathon, Battle of marsupials: X inactivation in see also Tasmanian devils maternal environment, see fetal environment maternal style transgenerational transmission of McDonald’s McGwire, Mark Meaney, Michael melanin melanocyte stimulating hormone melanoma Mendel, Gregor Mendel’s laws messenger RNA (mRNA) metabolic syndrome metastasis methylation/demethylation in cancer cells diet and of DNA of estrogen receptors in genomic imprinting of GR gene of histones permanence of randomness in of viable yellow allele in X inactivation methyl group (CH3) mice and rats: agouti locus in, see agouti locus Axin gene in gene methylation in imprinting disruption in stress biasing in microenvironment, of cancer cells microRNA monozygotic twins: discordances in epigenetic alterations in Kallmann syndrome in stress responses in Morgan, Thomas Hunt mortality, male vs. female risk of mothering: affectionless control in in gorillas hormonal changes and infant-mother bond and as social inheritance stress biasing and see also maternal style; parenting motherless mothers as vicious cycle Mount Williams National Park mules, hinnies multipotent cells Mus muscle: androgen receptors in genomic imprinting and mutation cancer and dominant vs. recessive alleles in natural disasters natural experiments naturalism Neel, James neonates, link between birth weight and health of neural crest cells neural stem cells neurons Newtonian physics NGF (NGFI-A; nerve growth factor inducible factor A) NGF gene normalization, of cancer cells nutrition, maternal, fetal development and obesity: agouti alleles and birth weight and childhood in Dutch famine cohort epigenetic explanations of as family trait fetal environment and gene mutation and genetic explanations of genomic imprinting and GR expression and Western lifestyle and obsessive-compulsive disorder, maternal style and Ohno, Susumu olfaction, epigenetic inheritance and olfaction, Kallmann syndrome and, ix–x olfactory placode oligopotent cells oncogenes see also cancer “one gene – one protein” rule opsin genes organicism organ transplants osteoporosis oxytocin Pacific Islanders Paradorn (pseud.)

The Rise of Yeast: How the Sugar Fungus Shaped Civilisation

by

Nicholas P. Money

Published 22 Feb 2018

Cells like this, which contain a single set of chromosomes, are described as haploid. Animal and plant cells with two sets of chromosomes are diploid. Being diploid means that the effects of one version of a gene, called an allele, can be masked by another version of the same gene on the matching chromosome. This allows us, like Gregor Mendel’s pea plants, to pass mutated versions of genes to our offspring without displaying their effects ourselves. An imbalance in fat metabolism, for example, can be passed to a child from both parents that carry a defective gene yet enjoy healthy levels of fat storage themselves. The errant version of the gene carried by both parents hides behind the uncorrupted gene on their second version of the same chromosome.

…

Winge was a Danish investigator who worked at the Carlsberg Laboratory in Copenhagen, established by the famous Carlsberg Brewery.10 Winge designed a method for carrying out specific mating reactions between yeast strains using their ascospores, and demonstrated that the fungus behaved according to Gregor Mendel’s rules of inheritance. These experiments added to the growing sense that Saccharomyces could be the perfect experimental organism for genetic research. In the 1940s, Carl and Gertrude Lindegren discovered the a and α mating types of yeast. The Lindegrens’ lab at Washington University in St. Louis enjoyed funding from the Anheuser-Busch Company, whose products include the iconic Budweiser lager.

The Magic of Reality: How We Know What's Really True

by

Richard Dawkins

Published 3 Oct 2011

But you can’t see the details of what DNA looks like, even with a powerful microscope. Almost everything we know about DNA comes indirectly from dreaming up models and then testing them. Actually, long before anyone had even heard of DNA, scientists already knew lots about genes from testing the predictions of models. Back in the nineteenth century, an Austrian monk called Gregor Mendel did experiments in his monastery garden, breeding peas in large quantities. He counted the numbers of plants that had flowers of various colours, or that had peas that were wrinkly or smooth, as the generations went by. Mendel never saw or touched a gene. All he saw were peas and flowers, and he could use his eyes to count different types.

…

The predictions of one model, the so-called double helix model, exactly fitted the measurements made by Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins, using special instruments involving X-rays beamed into crystals of purified DNA. Watson and Crick also immediately realized that their model of the structure of DNA would produce exactly the kind of results seen by Gregor Mendel in his monastery garden. We come to know what is real, then, in one of three ways. We can detect it directly, using our five senses; or indirectly, using our senses aided by special instruments such as telescopes and microscopes; or even more indirectly, by creating models of what might be real and then testing those models to see whether they successfully predict things that we can see (or hear, etc.), with or without the aid of instruments.

The Age of the Infovore: Succeeding in the Information Economy

by

Tyler Cowen

Published 25 May 2010

It turns out she has developed a system for remembering people by their clothes and that she applied her system very conscientiously and consistently; without the system she would be lost. People such as myself, who have normal face-recognition abilities, usually have no such system. The result was that this woman—some might call her “handicapped”—had a much better sense of the crowd than I did. Charles Darwin, Gregor Mendel, Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, Albert Einstein, Isaac Newton, Samuel Johnson, Vincent van Gogh, Thomas Jefferson, Bertrand Russell, Jonathan Swift, Alan Turing, Paul Dirac, Glenn Gould, Steven Spielberg, and Bill Gates, among many others, are all on the rather lengthy list of famous figures who have been identified as possibly autistic or Asperger’s.

…

If you’re wondering, a typical list of historical figures claimed to be on the autism spectrum includes Hans Christian Andersen, Lewis Carroll, Herman Melville, George Orwell, Jonathan Swift, William Butler Yeats, James Joyce, Bela Bartók, Bob Dylan, Glenn Gould, Vincent van Gogh, Andy Warhol, Mozart, Gregor Mendel, Charles Darwin, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Henry Cavendish, Samuel Johnson, Albert Einstein, Alan Turing, Paul Dirac, Emily Dickinson, Michelangelo, Bertrand Russell, Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, Isaac Newton, and Willard Van Orman Quine, among others. When it comes to any individual life, I have my worries about making any firm judgments.

Buzz: The Nature and Necessity of Bees

by

Thor Hanson

Published 1 Jul 2018

After numerous complaints, the publisher deleted it completely from the third, fourth, and fifth editions. But the idea of pollination could be tested by anyone with access to a farm, a garden, or even a flowerpot. Eventually, the dance between bees and flowers came to fascinate some of the greatest thinkers in biology, including such luminaries (and beekeepers) as Charles Darwin and Gregor Mendel. Today, pollination remains a vital field of study, because we know it is more than simply illuminating: it is irreplaceable. In the twenty-first century, sweetness comes to us from refined sugars, wax is a by-product of petroleum, and we get our light with the flick of a switch. But for the propagation of nearly every crop and wild plant not serviced by the wind, our reliance upon bees remains complete.

…

Alfalfa Chickpea Leek Potato Allspice Chi li pepper Lemon Prickly pear Almond Chives Lentil Pumpkin Anise Citron Lettuce Quince Annatto Cloudberry Lime Radicchio Apple Clover Loquat Radish Apricot Cloves Lychee Rambutan Artichoke Coconut Macadamia Rapeseed Asparagus Coffee Mandarin Raspberry Aubergine Collards Mango Red currant Avocado Coriander Marjoram Red pepper Barbados cherry Cotton Medlar Rose hips Basil Courgette Millet Rosemary Bay leaf Cowpea Muscadine grape Rowanberry Beans (various) Cranberry Muskmelon Rutabaga Bergamot Cucumber Mustard Safflower Black currant Cumin Nectarine Sage Blackberry Dewberry Nutmeg Sapote Blueberry Dill Oil palm Sesame Brazil nut Durian Okra Soybean Breadfruit Elderberry Onion Squash Broccoli Endive Orange Starfruit Brussels sprouts Fennel Oregano Stevia Buckwheat Fenugreek Papaya Strawberry Cabbage Flaxseed Paprika Sugarcane Canola Garlic Parsley Sunflower Cantaloupe Grapefruit Parsnip Sweet potato Caraway Groundnut Passionfruit Tamarind Cardamom Guar Peach Tangerine Carrot Guava Peanut Thyme Cashew Hog plum Pear Tomatillo Cassava Jackfruit Pepper Tomato Cauliflower Jujube Persimmon Turnip Celeriac Kale Pigeon pea Vanilla Celery Kiwfruit Pimento Watermelon Chayote Kohlrabi Plum Yams Cherry Kola nut Pomegranate Chestnut Kumquat Pomelo Whether measured by quantity, variety, nutrition, or flavor, nearly every bite of food we take feels some effect from bees. But it’s worth pointing out that other animal pollination options do exist. Flies, wasps, thrips, birds, beetles, and bats do a bit of crop pollination, and, in a pinch, so do people. Gregor Mendel hand-pollinated over ten thousand pea plants in his pioneering study of genetics, and modern plant breeders use similar techniques to create new hybrids or to cross particularly promising varieties. But for anything produced on a commercial scale, pollinating by hand is usually considered too labor intensive to be anything more than a last resort.

Howard Rheingold

by

The Virtual Community Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier-Perseus Books (1993)

Published 26 Apr 2012

If more and more scientific communication moves onto the Net, as it seems to be doing, where anybody who has net access to put forth their equations or their theory along with the academicians, several kinds of results are likely. First, you are as marginalized as Gregor Mendel was if you are a member of neither the academy nor the Net, because that is where all the important attention will be. Second, if you are Gregor Mendel, all you have to do is gain net access in order to participate in the international group conversation of science. But before the Net grew enough to allow citizen participation, access to the Net enabled scientists in quickly moving fields to have their own specialized versions of the living database that the WELL and Usenet provides other groups; to the degree that the process of science is embedded in group communication, the many-to-many characteristic of virtual communities can both accelerate and democratize access to cutting-edge knowledge.

…

From this process of observation, experimentation, theorization, and communication, scientific knowledge is supposed to emerge. The bottleneck is access to the academy, to the scientific hierarchies that admit novices to circles where their communications can be noticed. In the nineteenth century, an Austrian monk, Gregor Mendel, experimented with sweet peas and discovered the laws of genetics, but he did not have access to the highest scientific journals. The knowledge lay fallow for decades, until it was rediscovered in an obscure journal by biologists who were on the track of the mysteries of genetics. Mendel's experience is worth remembering as scientific discourse moves onto the Net.

The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect

by

Judea Pearl

and

Dana Mackenzie

Published 1 Mar 2018

That stability, now called the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, received a satisfactory mathematical explanation in the work of G. H. Hardy and Wilhelm Weinberg in 1908. And yes, they used yet another causal model—the Mendelian theory of inheritance. In retrospect, Galton could not have anticipated the work of Mendel, Hardy, and Weinberg. In 1877, when Galton gave his lecture, Gregor Mendel’s work of 1866 had been forgotten (it was only rediscovered in 1900), and the mathematics of Hardy and Weinberg’s proofs would likely have been beyond him. But it is interesting to note how close he came to finding the right framework and also how the causal diagram makes it easy to zero in on his mistaken assumption: the transmission of luck from one generation to the next.

…

Later, when Sewall worked in Washington, DC, Philip did likewise, first at the US Tariff Commission and then at the Brookings Institution as an economist. Although their academic interests diverged, they nevertheless found ways to collaborate, and Philip was the first economist to make use of his son’s invention of path diagrams. Wright came to Harvard to study genetics, at the time one of the hottest topics in science because Gregor Mendel’s theory of dominant and recessive genes had just been rediscovered. Wright’s advisor, William Castle, had identified eight different hereditary factors (or genes, as we would call them today) that affected fur color in rabbits. Castle assigned Wright to do the same thing for guinea pigs. After earning his doctorate in 1915, Wright got an offer for which he was uniquely qualified: taking care of guinea pigs at the US Department of Agriculture (USDA).

…

Remember that it is always advantageous, as in Snow’s example, to use an instrumental variable that is randomized. If it’s randomized, no causal arrows point toward it. For this reason, a gene is a perfect instrumental variable. Our genes are randomized at the time of conception, so it’s just as if Gregor Mendel himself had reached down from heaven and assigned some people a high-risk gene and others a low-risk gene. That’s the reason for the term “Mendelian randomization.” Could there be an arrow going the other way, from HDL Gene to Lifestyle? Here we again need to do “shoe-leather work” and think causally.

The Sellout: A Novel

by

Paul Beatty

Published 2 Mar 2016

But anyone who’d ever been to Tito’s Tacos and tasted a warm cupful of the greasy, creamy, refried frijole slop covered in a solid half-inch of melted cheddar cheese knew the bean had already reached genetic perfection. I remember wondering why George Washington Carver. Why couldn’t I have been the next Gregor Mendel, the next whoever it was that invented the Chia Pet, and even though nobody remembers Captain Kangaroo, the next Mr. Green Jeans? So I chose to specialize in the plant life that had the most cultural relevance to me—watermelon and weed. At best I’m a subsistence farmer, but three or four times a year, I’ll hitch a horse to the wagon and clomp through Dickens, hawking my wares, Mongo Santamaría’s “Watermelon Man” blasting from the boom box.

…

Stroke her with techniques that are basically the same ones I used on the thoroughbreds at school after a work-study day of galloping and breezing horses in the fields. Rub her ears. Blow gently into her nostrils. Work her joints. Brush her hair. Shotgun weed smoke into her pursed and needy lips. When she hands me the baby, and I descend the stairs into the applause of the waiting crowd, I’d like to think that Gregor Mendel, George Washington Carver, and even my father would be proud, and sometime while they’re being strapped to the gurney or consoled by a distraught grandmother, I’ll ask them, “Why Wednesday?” Five Dickens’s evanesce hit some folks harder than others, but the citizen who needed my services the most was old man Hominy Jenkins.

The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer

by

Siddhartha Mukherjee

Published 16 Nov 2010

This is a reprint and new translation of the original text. 342 “unitary cause of carcinoma”: Ibid., 56. 342 not “an unnatural group of different maladies”: Ibid., 56. 342 In 1910, four years before Boveri had published his theory: Peyton Rous, “A Transmissible Avian Neoplasm (Sarcoma of the Common Fowl),” Journal of Experimental Medicine 12, no. 5 (1910): 696–705; Peyton Rous, “A Sarcoma of the Fowl Transmissible by an Agent Separable from the Tumor Cells,” Journal of Experimental Medicine 13, no. 4 (1911): 397–411. 342 In 1909, a year before: Karl Landsteiner et al., “La transmission de la paralysie infantile aux singes,” Compt. Rend. Soc. Biologie 67 (1909). 343 In the early 1860s, working alone: Gregor Mendel, “Versuche über Plfanzenhybriden,” Verhandlungen des Naturforschenden Vereines in Brünn. IV für das Jahr 1865, Abhandlungen (1866): 3–47. English translation available at http://www.esp.org/foundations/genetics/classical/gm-65.pdf (accessed January 2, 2010). Also see Robin Marantz Henig, The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, the Father of Genetics (Boston: Mariner Books, 2001), 142. 343 decades later, in 1909, botanists: Wilhelm Ludwig Johannsen, Elemente der Exakten Erblichkeitlehre (1913), http://caliban.mpiz-koeln.mpg.de/johannsen/elemente/index.html (accessed January 2, 2010). 344 In 1910, Thomas Hunt Morgan: See T.

…

While the mechanistic understanding of the cancer cell remained suspended in limbo between viruses and chromosomes, a revolution in the understanding of normal cells was sweeping through biology in the early twentieth century. The seeds of this revolution were planted by a retiring, nearsighted monk in the isolated hamlet of Brno, Austria, who bred pea plants as a hobby. In the early 1860s, working alone, Gregor Mendel had identified a few characteristics in his purebred plants that were inherited from one generation to the next—the color of the pea flower, the texture of the pea seed, the height of the pea plant. When Mendel intercrossed short and tall, or blue-flowering and green-flowering, plants using a pair of minute forceps, he stumbled on a startling phenomenon.

…

Kalckar, and Otto Warburg. On Cancer and Hormones: Essays in Experimental Biology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962. Hall, Steven S. Invisible Frontiers: The Race to Synthesize a Human Gene. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1987. Henig, Robin Marantz. The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, the Father of Genetics. New York: Mariner Books, 2001. Hill, John. Cautions against the Immoderate Use of Snuff. London: R. Baldwin and J. Jackson, 1761. Hilts, Philip J. Protecting America’s Health: The FDA, Business, and One Hundred Years of Regulation. New York: Knopf, 2003. Huggins, Charles.

Is God a Mathematician?

by

Mario Livio

Published 6 Jan 2009

OK, you may think, but other than in casino games and other gambling activities, what additional uses can we make of these very basic probability concepts? Believe it or not, these seemingly insignificant probability laws are at the heart of the modern study of genetics—the science of the inheritance of biological characteristics. The person who brought probability into genetics was a Moravian priest. Gregor Mendel (1822–84) was born in a village near the border between Moravia and Silesia (today Hyncice in the Czech Republic). After entering the Augustinian Abbey of St. Thomas in Brno, he studied zoology, botany, physics, and chemistry at the University of Vienna. Upon returning to Brno, he began an active experimentation with pea plants, with strong support from the abbot of the Augustinian monastery.

…

Hardy Addresses the British Association in 1922, part 1.” http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Extras/BA_1922_1.html. Odom, B., Hanneke, D., D’Urso, B., and Gabrielse, G. 2006. Physical Review Letters, 97, 030801. Ooguri, H., and Vafa, C. 2000. Nuclear Physics B, 577, 419. Orel, V. 1996. Gregor Mendel: The First Geneticist (New York: Oxford University Press). Overbye, D. 2000. Einstein in Love: A Scientific Romance (New York: Viking). Pais, A. 1982. Subtle Is the Lord: The Science and Life of Albert Einstein (Oxford: Oxford University Press). Panek, R. 1998. Seeing and Believing: How the Telescope Opened Our Eyes and Minds to the Heavens (New York: Viking).

The Genetic Lottery: Why DNA Matters for Social Equality

by

Kathryn Paige Harden

Published 20 Sep 2021

What selective breeding allowed the agricultural industry to do was make the genetic variants that increase milk production more common in the cow population, which increases the number of milk-increasing genetic variants that are concentrated in combination in any one single animal.12 Thinking about combinations of many genetic variants, which can be concentrated to varying degrees in a single animal, might be unintuitive. If, like me, you first encountered genetics in high school biology, your introduction to genetics was Gregor Mendel and his pea plants. The pea plant characteristics that Mendel worked with (tall versus short, wrinkly versus smooth, green versus yellow) were determined by a single genetic variant. In contrast, the human characteristics we care most about—things like personality and mental disease, sexual behavior and longevity, intelligence test scores and educational attainment—are influenced by many (very, very, very many) genetic variants, each of which contributes only a tiny drop of water to the swimming pool of genes that make a difference.

…

For each of my twenty-three pairs of chromosomes, the chromosome that I inherited from my mother and the chromosome that I inherited from my father line up and trade pieces. This recombination process does, in fact, re-combine genetic variants into brand new combinations that are all different from each other. The recombination process is the biological basis of what Gregor Mendel, on the basis of his mathematical observations, called the law of independent assortment. The probability of inheriting a certain version of gene A is independent from the probability of inheriting a certain version of gene B. Except, that is, when gene A and gene B are very close to each other, physically, on the genome.

Life Is Simple: How Occam's Razor Set Science Free and Shapes the Universe

by

Johnjoe McFadden

Published 27 Sep 2021

It was probably at Olomouc where Johann acquired an interest in heredity, as its dean of natural sciences, Johann Nestler, had performed his own animal- and plant-breeding experiments. Theresia’s dowry was not however bottomless so to continue his education Mendel entered St Thomas’s Abbey in Brno in 1843 as a novice friar. There he adopted the name Gregor. As he later wrote, ‘my circumstances decided my vocational choice’. Gregor Mendel was first trained as a priest and given his own parish but, in a 1849 letter to the local bishop, Abbot Cyril Napp admits of Mendel that: ‘He is very diligent in the study of sciences but much less fitted for work as a parish priest.’ The abbot sent the scientifically minded friar to the University of Vienna where he studied physics, under Christian Doppler, famous for discovering the Doppler effect.

…

R., and Berry, A., The Malay Archipelago (Penguin, 2014). Chapter 15: Of Peas, Primroses, Flies and Blind Rodents 1. Wallace, A. R., Mimicry, and Other Protective Resemblances Among Animals (Read Books Limited, 2016). 2. Vorzimmer, P., ‘Charles Darwin and Blending Inheritance’, Isis, 54, 371–90 (1963). 3. De Castro, M., ‘Johann Gregor Mendel: Paragon of Experimental Science’, Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine, 4, 3 (2016). 4. Mendel, G., Experiments on Plant Hybrids (1866), translation and commentary by Staffan Müller-Wille and Kersten Hall, British Society for the History of Science Translation Series (2016), http://www.bshs.org.uk/bshs-translations/mendel. 5.

Journey to the Edge of Reason: The Life of Kurt Gödel

by

Stephen Budiansky

Published 10 May 2021

The Viennese-born Ludwig von Boltzmann, one of the giants of physical chemistry, developed the theory of statistical mechanics, which relates the statistical behavior of atoms to physical properties of matter such as heat capacity of a metal or pressure of a gas. And from Gödel’s hometown of Brünn came the geneticist monk Gregor Mendel and the experimental physicist Ernst Mach, whose name would be immortalized in the unit of the speed of sound in recognition of his exploration of supersonic dynamics—which led him along the way to the development of high-speed photography, which he used to capture extraordinary images of bullets in flight and their attendant shockwaves.

…

A large entrance hall on the first floor was paneled in natural wood and furnished in modern good taste with Jugendstil furniture, the seats of the chairs covered in the Arts-and-Crafts prints of the turn-of-the-century Viennese movement that evoked and celebrated the handcrafts of the pre-industrial age that Brünn had led the world in destroying. The Gödel villa on Spielberggasse (now Pellicova) HERR WARUM Science and progress were in the very air of Brünn. A ten-minute walk down the hill from the Gödel villa was the Augustinian abbey of Altbrünn, where Gregor Mendel spent a decade hybridizing and meticulously sorting and counting the blossoms and pods of 10,000 pea plants, laying the foundation of modern genetics. The 1910 dedication of a marble statue of Mendel, erected “by the friends of science” in the square in front of his monastery garden, brought famous biologists from across Europe to the city.

Gene Eating: The Science of Obesity and the Truth About Dieting

by

Giles Yeo

Published 3 Jun 2019

In particular, they both ate voraciously (explaining their spherical geometry) and were both infertile, and it was apparent by the way these characteristics were inherited that these were the result of mutations in single genes. GENETICS ‘101’ Most of us, when we were introduced to the concept of genetics at school, would have learnt about Mendel and his peas. Gregor Mendel, a 19th-century Augustinian friar and a scientist, is widely considered to be the father of modern genetics. He worked out the basic principles of genetics by breeding pea plants and observing how seven different characteristics (plant height, pod shape and colour, seed shape and colour, and flower position and colour) were inherited.

…

The key part of the experiment, and how he figured out what was happening, came when he bred the yellow offspring from the first cross together (Cross 2 in the figure). What he found was that three-quarters of the offspring from this second cross were yellow, while the green-coloured peas re-appeared, but only in one quarter of the offspring. He saw similar results in all of the seven characteristics that he was studying. FIGURE 3 Gregor Mendel’s pea-breeding experiments, establishing the concept of dominant and recessive genes He deduced two fundamental principles from these breeding experiments. First, he worked out that each of the pea plant’s traits had to be determined by two copies of some invisible factor: these would later be called ‘genes’, one coming from each parent plant.

Information: A Very Short Introduction

by

Luciano Floridi

Published 25 Feb 2010

Genetic information Genetics is the branch of biology that studies the structures and processes involved in the heredity and variation of the genetic material and observable traits (phenotypes) of living organisms. Heredity and variations have been exploited by humanity since antiquity, for example to breed animals. But it was only in the 19th century that Gregor Mendel (1822-1884), the founder of genetics, showed that phenotypes are passed on, from one generation to the next, through what were later called genes. In 1944, in a brilliant book based on a series of lectures, entitled What Is Life?, the physics Nobel laureate Erwin Schrodinger (1887-1961) outlined the idea of how genetic information might be stored.

Complexity: A Guided Tour

by

Melanie Mitchell

Published 31 Mar 2009

Mendel and the Mechanism of Heredity A major issue not explained by Darwin’s theory was exactly how traits are passed on from parent to offspring, and how variation in those traits—upon which natural selection acts—comes about. The discovery that DNA is the carrier of hereditary information did not take place until the 1940s. Many theories of heredity were proposed in the 1800s, but none was widely accepted until the “rediscovery” in 1900 of the work of Gregor Mendel. Mendel was an Austrian monk and physics teacher with a strong interest in nature. Having studied the theories of Lamarck on the inheritance of acquired traits, Mendel performed a sequence of experiments, over a period of eight years, on generations of related pea plants to see whether he could verify Lamarck’s claims.

…

Mendel’s long years of experiments revealed several things that are still considered roughly valid in modern-day genetics. First, he found that the plants’ offspring did not take on any traits that were acquired by the parents during their lifetimes. Thus, Lamarckian inheritance did not take place. Gregor Mendel, 1822–1884 (From the National Library of Medicine) [http://wwwils.nlm.nih.gov/visibleproofs/galleries/ technologies/dna.html]. Second, he found that heredity took place via discrete “factors” that are contributed by the parents, one factor being contributed by each parent for each trait (e.g., each parent contributes either a factor for tall stems or dwarf stems).

The Evolution of Everything: How New Ideas Emerge

by

Matt Ridley

As Francis Crick pondered of his partner in the elucidation of the double helix, James Watson: ‘If Jim had been killed by a tennis ball, I am reasonably sure I would not have solved the structure alone, but who would?’ There were plenty of candidates: Maurice Wilkins, Rosalind Franklin, Raymond Gosling, Linus Pauling, Sven Furberg, and others. The double helix and the genetic code would not have remained hidden for long. Gregor Mendel, the father of genetics, is an interesting exception to the rule of simultaneous discovery. His revelation of independently assorting, apparently indivisible particles of inheritance (genes) stood alone in the 1860s – though you can make a case that a chap called Thomas Knight had glimpsed the insight a few decades before, when he noticed that violet-flowered peas crossed with white-flowered peas produced mainly violet-flowered offspring.

…

Even progressives with no ostensible ties to eugenics worked closely with champions of the cause. There was simply no significant stigma against racist eugenics in progressive circles.’ It mattered little that scientific support for this policy was weak in the extreme. In fact the discoveries of Gregor Mendel, which became known to the world in 1900, ought to have killed eugenics stone dead. Particulate inheritance and recessive genes made the idea of preventing the deterioration of the human race by selective breeding greatly more difficult and impractical. How were those in charge of breeding the human race supposed to spot the heterozygotes who carried but did not express some essence of imbecility or unfitness?

As the Future Catches You: How Genomics & Other Forces Are Changing Your Work, Health & Wealth

by

Juan Enriquez

Published 15 Feb 2001

And perhaps the most important challenge we will face in the twenty-first century … is how … and when … to apply this knowledge. (Harvard, with its classic modesty, has located its biochemistry, genomics, and molecular-biology labs just off Divinity Avenue.)1 It took nearly a century and a half to start to read the language that determines all life processes. In the 1850s, an Austrian monk, Gregor Mendel, began experimenting in the garden of his monastery.2 He used the pollen of some plants to carefully fertilize other plants … Mostly peas. By carrying out these experiments deliberately and carefully recording the results, Mendel was able to observe that various traits present in grandparents, mothers, and fathers could be passed on to offspring … And he could catalog which traits tended to dominate … Thus giving rise to a new discipline … Which we now call genetics.

Life on the Edge: The Coming of Age of Quantum Biology

by

Johnjoe McFadden

and

Jim Al-Khalili

Published 14 Oct 2014

In his “51st Exercitation” of 1653, the English surgeon William Harvey wrote: Although it be a known thing subscribed by all, that the foetus assumes its origin and birth from the male and female, and consequently that the egge is produced by the cock and henne and the chicken out of the egge, yet neither the schools of physicians nor Aristotle’s discerning brain have disclosed the manner how the cock and its seed doth mint and coine the chicken out of the egge. Part of the answer was provided two centuries later by the Austrian monk and plant scientist Gregor Mendel, who around 1850 was breeding peas in the garden of the Augustinian abbey at Brno. His observations led him to propose that traits such as flower color or pea shape were controlled by heritable “factors” that could be transmitted, unchanged, from one generation to the next. Mendel’s “factors” thereby provided a repository of heritable information that allowed peas to retain their character through hundreds of generations—or through which “the cock and its seed doth mint and coine the chicken out of the egge.”

…

He never really resolved this problem in his lifetime. Indeed, in later editions of the Origin of Species he even resorted to a form of Lamarckian evolutionary theory to generate heritable minor variation. Part of the solution had already been discovered during Darwin’s lifetime by the Czech monk and plant breeder Gregor Mendel, whom we met in chapter 2. Mendel’s experiments with peas demonstrated that small variations in pea shape or color were indeed stably inherited: that is—crucially—these traits did not blend but bred true generation after generation, though often skipping generations if the character was recessive rather than dominant.

The Kingdom of Speech

by

Tom Wolfe

Published 30 Aug 2016

See also “Review of Descent of Man,” Athenaeum 3 (April 1871), and “Review of The Descent of Man,” Edinburgh Review (July–October 1871). 74 For more information about the Philological Society, see Fiona Marshall, “History of the Philological Society: The Early Years,” available from www.philsoc.org.uk/history.asp. 75 Société de Linguistique de Paris. “Statuts de 1866, Art. 2.” Available at: http://www.slp-paris.com/spip.php?article5. 76 See Barton, “‘An Influential Set of Chaps.’” 77 Quoted in Paul C. Mangelsdorf, foreword to Experiments in Plant Hybridisation by Gregor Mendel (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965). This note was kept by one of Mendel’s fellow monks, Franz Barina. 78 Theodosius Dobzhansky, “Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution,” The American Biology Teacher 35, no. 3 (March 1973), 125–29. 79 See Morris Swadesh, “Sociologic Notes on Obsolescent Languages,” International Journal of American Linguistics 14, no. 4 (October 1948), 226–35, and Stanley Newman, “Morris Swadesh (1909–1967),” Language 43, no. 4 (December 1967), 948–57. 80 Roger Hilsman, American Guerrilla: My War Behind Japanese Lines (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2005), 143. 81 Morris Swadesh, “Towards Greater Accuracy in Lexicostatistical Dating,” International Journal of American Linguistics 21, no. 2 (April 1955), 121–37. 82 Edwin G.

Hacking the Code of Life: How Gene Editing Will Rewrite Our Futures

by

Nessa Carey

Published 7 Mar 2019

They hoped the characteristic they were interested in ‘bred true’, in other words that it showed up in the offspring, or even was better in the next generation. But they had no idea how these characteristics were passed on from parents. The first step in formalising a data-based theory for this came from the Augustinian friar Gregor Mendel, working in Saint Thomas’s Abbey in Brno, in what is today the Czech Republic. Mendel crossed different strains of peas very systematically and examined the offspring, counting characteristics such as smoothness or wrinkling of the peas. He determined that particular characteristics were passed on in a specific ratio, and to explain his findings he referred to invisible factors that governed the physical appearance.

Science in the Soul: Selected Writings of a Passionate Rationalist

by

Richard Dawkins

Published 15 Mar 2017

Fortunately, human writing is digital, at least in the sense we care about here. And the same is true of the DNA books of ancestral wisdom that we carry around inside us. Genes are digital, and in the full sense not shared by nerves. Digital genetics was discovered in the nineteenth century, but Gregor Mendel was ahead of his time and ignored. The only serious error in Darwin’s world-view derived from the conventional wisdom of his age, that inheritance was ‘blending’ – analogue genetics. It was dimly realized in Darwin’s time that analogue genetics was incompatible with his whole theory of natural selection.

…

In the United States today, a person will be called ‘African American’ even if only, say, one of his eight great-grandparents was of African descent. Colin Powell and Barack Obama are described as black. They do have black ancestors, but they also have white ancestors, so why don’t we call them white? It is a weird convention that the descriptor ‘black’ behaves as the cultural equivalent of a genetic dominant. Gregor Mendel, the father of genetics, crossed wrinkled and smooth peas and the offspring were all smooth: smoothness is ‘dominant’. When a white person breeds with a black person the child is intermediate but is labelled ‘black’: the cultural label is transmitted down the generations like a dominant gene, and this persists even to cases where, say, only one out of eight great-grandparents was black and it may not show in skin colour at all.

A Dominant Character

by

Samanth Subramanian

Published 27 Apr 2020

—Gilbert Wynant, to his sister, in The Thin Man In 1901, when Jack was 8 years old, his father took him to the Oxford University Junior Scientific Club, where the biologist Arthur Darbishire was giving a lecture on Mendel’s laws of inheritance. The explanatory power of these laws was only just being appreciated, and they were transforming the state of science in the Western world. Gregor Mendel, the Augustinian friar, had conducted his experiments on pea plants five decades earlier in his abbey in Brünn, now a town called Brno in the Czech Republic. First in a kitchen garden and then in a two-room glass hothouse, he had planted 34 true-breeding strains of peas—strains that always produced offspring whose every trait matched that of the parent.

…

Hawks, John, Eric T. Wang, Gregory M. Cochran, Henry C. Harpending, and Robert K. Moyzis. “Recent Acceleration of Human Adaptive Evolution.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, no. 52 (December 2007): 20753–58. Henig, Robin Marantz. The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, the Father of Genetics. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000. Hermiston, Roger. All Behind You, Winston: Churchill’s Great Coalition 1940–45. London: Aurum Press, 2016. Hobsbawm, Eric. Revolutionaries. New York: The New Press, 2001. Howard, Victor. The MacKenzie-Papineau Battalion: The Canadian Contingent in the Spanish Civil War.

Life's Greatest Secret: The Race to Crack the Genetic Code

by

Matthew Cobb

Published 6 Jul 2015

But unlike them, Napp was able to organise and encourage a cohort of bright intellectuals in his monastery to explore the question, a bit like a modern university department focuses on a particular topic. This research programme reached its conclusion in 1865, when Napp’s protégé, a monk named Gregor Mendel, gave two lectures in which he showed that, in pea plants, inheritance was based on factors that were passed down the generations. Mendel’s discovery, which was published in the following year, had little impact and Mendel did no further work on the subject; Napp died shortly afterwards, and Mendel devoted all his time to running the monastery until his death in 1884.

…

Hao, B., Gong, W., Ferguson, T. K. et al., ‘A new UAG-encoded residue in the structure of a methanogen methyltransferase’, Science, vol. 296, 2002, pp. 1462–6. Hargittai, I., Candid Science II: Conversations with Famous Biomedical Sciences, London, Imperial College Press, 2002. Hartl, D. L. and Orel, V., ‘What did Gregor Mendel think he discovered?’, Genetics, vol. 131, 1992, pp. 245–53. Hartl, F. U., Bracher, A. and Hayer-Hartl, M., ‘Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis’, Nature, vol. 475, 2011, pp. 324–32. Hatfield, D. L. and Gladyshev, V. N., ‘How selenium has altered our understanding of the genetic code’, Molecular and Cell Biology, vol. 22, 2002, pp. 3565–76.

She Has Her Mother's Laugh

by

Carl Zimmer

Published 29 May 2018

A monk named Matthew Klácel ran experiments in another garden—at least until his radical philosophy on nature forced him to flee to the United States. When young men entered the Augustinian order, Napp encouraged them to immerse themselves in the latest scientific advances. One of the young men in whom Napp took a special interest was a poor farmer’s son named Gregor Mendel. Mendel’s first job at the priory was to teach languages, math, and science in a local school. He proved so good at it that Napp sent him to the University of Vienna for more training. Mendel took a course in physics there in which he learned how to design careful experiments, and another in botany, where he learned about the long-running debate over hybrid plants and whether two species could cross to produce a new species.

…

For now, the experience of the disease is a tense negotiation between heredity and the world in which it unfolds. PART II Wayward DNA CHAPTER 5 An Evening’s Revelry IN 1901, WILLIAM BATESON sent an urgent report to the Royal Society on “the facts of heredity.” Those facts, Bateson explained, had just been thrown into sharp relief with the rediscovered, newly appreciated work of Gregor Mendel. Bateson and other scientists were confirming the patterns that Mendel had observed. Those patterns were so trustworthy and so profound, Bateson said, that they deserved one of the loftiest titles in science: “Mendel’s Law.” A scientific law predicts some aspect of the universe, usually with a short, sweet equation.

…

Gitschier, Jane. 2010. “The Gift of Observation: An Interview with Mary Lyon.” PLOS Genetics 6:e1000813. Glass, Bentley. 1980. “The Strange Encounter of Luther Burbank and George Harrison Shull.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 124:133–53. Gliboff, Sander. 2013. “The Many Sides of Gregor Mendel.” In Outsider Scientists: Routes to Innovation in Biology. Edited by Oren Harman and Michael R. Dietrich. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Goddard, Henry H. 1908. “A Group of Feeble-Minded Children with Special Regard to Their Number Concepts.” Supplement to the Training School 2:1–16. ———. 1910a.

The Crowded Universe: The Search for Living Planets

by

Alan Boss

Published 3 Feb 2009

The zenith of Doppler’s career came in 1850, when he was appointed founding director of the Institute of Physics at Vienna’s Imperial University. As director, he was responsible for deciding which candidates would be admitted for study at the university. (One candidate he turned down was Johann Gregor Mendel, who later gained admission to the university through a different department and became a pioneer of genetics research. Mendel’s mathematical skills were not considered on a par with what Doppler required of a physicist, to the everlasting benefit of modern genetics.) The Doppler effect that Walker and Campbell sought to measure was quite small.

Coming of Age in the Milky Way

by

Timothy Ferris

Published 30 Jun 1988

Without the stability imparted by genes, innovative mutations would be diluted away like drops of blood in the ocean, before they had time to spread to any significant numbers of individuals. In such a situation natural selection might occur, but it could scarcely account for the origin of species. The first evidence of the existence of genes did not appear until 1866, eight years after Darwin was obliged to publish The Origin of Species, when the Moravian monk Gregor Mendel published the results of his extensive experiments with green peas in the garden of an Augustinian monastery—results that demonstrated the requisite persistence of the quanta of heredity—and Mendel’s findings were in any event universally ignored until attention was called to them in 1900, by which time Darwin was dead.

…

Time: 1864 Noteworthy Events: William Huggins obtains the first spectrum of a nebula, finds that it is composed of gas. Noteworthy Events: James Clerk Maxwell publishes a unified theory of electricity and magnetism, portraying both as aspects of electromagnetic force. Time: 1865 Noteworthy Events: Gregor Mendel announces results of his research in genetics, revealing key to persistence of unchanging traits in living things, a critical missing element in Darwinism. Time: 1874, 1882 Noteworthy Events: Transits of Venus observed with new, more precise instruments, improving estimates of the astronomical unit.

The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race

by

Walter Isaacson

Published 9 Mar 2021

Driven by a passion to understand how nature works and by a competitive desire to turn discoveries into inventions, she would help make what Watson, with his typical grandiosity cloaked in the pretense of humility, would later tell her was the most important biological advance since the double helix. Darwin Mendel CHAPTER 2 The Gene Darwin The paths that led Watson and Crick to the discovery of DNA’s structure were pioneered a century earlier, in the 1850s, when the English naturalist Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species and Gregor Mendel, an underemployed priest in Brno (now part of the Czech Republic), began breeding peas in the garden of his abbey. The beaks of Darwin’s finches and the traits of Mendel’s peas gave birth to the idea of the gene, an entity inside of living organisms that carries the code of heredity.1 Darwin had originally planned to follow the career path of his father and grandfather, who were distinguished doctors.

…

But he soon realized, as did others, that this would mean that any new beneficial trait would be diluted over generations rather than be passed along intact. Darwin had in his personal library a copy of an obscure scientific journal that contained an article, written in 1866, with the answer. But he never got around to reading it, nor did almost any other scientist at the time. Mendel The author was Gregor Mendel, a short, plump monk born in 1822 whose parents were German-speaking farmers in Moravia, then part of the Austrian Empire. He was better at puttering around the garden of the abbey in Brno than being a parish priest; he spoke little Czech and was too shy to be a good pastor. So he decided to become a math and science teacher.

Sweetness and Light: The Mysterious History of the Honeybee

by

Hattie Ellis

Published 25 Apr 2006

Brother Adam’s idea was to build up strong colonies that could develop a natural resistance. His work enabled him to send healthy queens around the country; thanks to him, British beekeepers could restock and recover from this devastating disease, which had killed an estimated 90 percent of their colonies. Brother Adam was influenced by the ideas of Gregor Mendel (1822-1884), the Austrian monk who discovered the laws of heredity. Mendel had tried to apply his theories to breeding insects, but he knew more about peas than he did about bees. His hives had been kept side-by-side in the old-fashioned bee sheds that are still in use in Germany today; Brother Adam, with his practical apiarian knowledge, knew that the breeds should have been kept separate in order to ensure pure strains.

The Psychopath Inside: A Neuroscientist's Personal Journey Into the Dark Side of the Brain

by

James Fallon

Published 30 Oct 2013

Therefore, statements that the warrior gene “causes” aggression, violence, and retaliation raises the hackles of geneticists, since there are probably dozens or more “warrior genes” in people who are particularly violent. But even the simple diseases (called Mendelian diseases, after the godfather of genetics, Gregor Mendel)—like cystic fibrosis, which is caused by a single mutation in the gene that codes for the chloride channel in cell membranes regulating water balance in the lungs and gut and glands—can appear as fifty different disorders in fifty different individuals with the disease. In the case of cystic fibrosis, that single chloride channel mutation affects other cellular and organ components.

What About Me?: The Struggle for Identity in a Market-Based Society

by

Paul Verhaeghe

Published 26 Mar 2014

Anglo-Saxon scholars and scientists were none too keen on the French, even back then, and the ruling classes were terrified that revolutionary notions might cross the Channel, along with guillotines and sans-culottes. Evolution? It might give people ideas! It took another half-century before Darwin published his beautifully argued theory, causing the heavenly gates to cave in at long last. Ironically, the final sledgehammer blows were dealt by an obscure eastern European monk, Gregor Mendel, the significance of whose experiments was only to be fully realised at the beginning of the 20th century. Inherited characteristics are passed on by the parents; each generation represents a new combination, and, every so often, unforeseen changes — mutations — take place. Evolution means change.

Life at the Speed of Light: From the Double Helix to the Dawn of Digital Life

by

J. Craig Venter

Published 16 Oct 2013

Charles Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus Darwin (1731–1802), a formidable intellectual force in eighteenth-century England, formulated one of the first formal theories of evolution in the first volume of Zoonomia; or the Laws of Organic Life2 (1794–1796), in which he stated that “all living animals have arisen from one living filament.” Classical genetics, as we understand it, has its origin in the 1850s and 1860s, when the Silesian friar Gregor Mendel (1822–1884) attempted to draw up the rules of inheritance governing plant hybridization. But it is only in the past seventy years that scientists have made the remarkable discovery that the “filament” that Erasmus Darwin proposed is in fact used to program every organism on the planet with the help of molecular robots.

The Half-Life of Facts: Why Everything We Know Has an Expiration Date

by

Samuel Arbesman

Published 31 Aug 2012

But Green, the Shakespeare of mathematical physics, is not the only example of these sorts of people. There are many instances when knowledge is not recognized or not combined, because it’s created by people who are simply too far ahead of their time, or who come from backgrounds that are so different from what is traditionally expected for scientific insight. For example, Gregor Mendel, now recognized as the father of genetics, died without being known at all. It wasn’t until years after his death that the Augustinian monk’s work was rediscovered, due to other scientists doing similar experiments and stumbling upon his findings. Yet he laid the foundation for the concepts of genes and the mathematics of the heritability of discrete traits.

12 Bytes: How We Got Here. Where We Might Go Next

by

Jeanette Winterson

Published 15 Mar 2021

That was great for his rich friends, who carried on cramming 15 people plus dogs and a pig into basement dwellings by the factory, while condemning them all for neglecting their children and spending every penny on gin. No connection whatsoever. They were a bad lot. Galton liked the idea of bad lots. He was influenced and impressed by the work of Gregor Mendel, an Austrian monk, who spent many years growing and studying peas in the monastery garden where he lived. Mendel discovered dominant and recessive genes, and learned how traits can be suppressed or encouraged through selective breeding – though this was something stock breeders had long practised, but without a formula behind it.

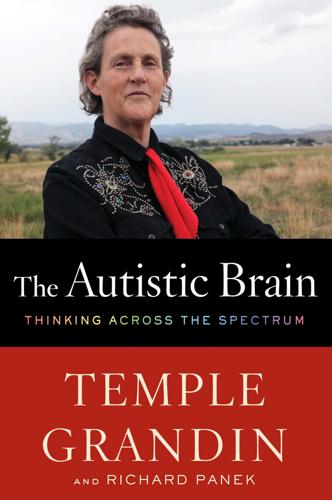

The Autistic Brain: Thinking Across the Spectrum

by

Temple Grandin

and

Richard Panek

Published 15 Feb 2013

She had the same concepts and facts as everyone else, but she saw them in a “new relation not previously seen.” I can think of plenty of examples of this sort of creativity from my own life. I remember when I was a student at Franklin Pierce College, and I took a course on genetics. The professor, Mr. Burns, taught us the usual model of genetics developed by Gregor Mendel in the nineteenth century—that each parent contributes half the genes in an offspring and that the way species gradually change is through a long series of random genetic mutations. That didn’t make sense to me. Sure, it was part of the explanation. But it couldn’t be the whole explanation. How do random mutations explain that when you take a Border collie and a springer spaniel and breed them, you get puppies that look like they’re a mixture of the two breeds, but they’re not exactly half and half?

Fully Automated Luxury Communism

by

Aaron Bastani

Published 10 Jun 2019

Indeed, we have knowingly altered the genome of various species for 12,000 years through selective breeding – a central innovation of the First Disruption. That gave us creatures fit for labour and crops like wheat which were hardy, easy to grow and nutritious. While we gained mastery in these fields before we had cities, writing or mathematics it wasn’t until the nineteenth century, through the work of Gregor Mendel, that we understood precisely how such mechanisms function. After Mendel, however, understanding genetic inheritance increasingly resembled a science rather than an art. By the middle of the twentieth century our knowledge of the field was so impressive that humans grasped how they might be able to accelerate a process seen throughout nature – evolution – inside a laboratory.

The Genius Within: Unlocking Your Brain's Potential

by

David Adam

Published 6 Feb 2018

That assumed, of course, feeble-minded parents would have feeble-minded children; that cognitive ability and disability would slide through the generations as easily as red hair or blue eyes. That was an assumption the eugenicists were happy to make, indeed they wrote endless books and pamphlets to make the case, and in doing so they unfairly demonized families and even entire communities. Using the newly rediscovered work on early genetics by the monk Gregor Mendel – who crossed pea plants and then worked out the basic laws of inheritance – the eugenicists of the early twentieth century said intelligence was a trait passed on from parent to child. And on this point they were mostly right. For all of the controversy then and now over the genetics of intelligence, the basic science is pretty simple.

How Many Friends Does One Person Need? Dunbar’s Number and Other Evolutionary Quirks

by

Robin Dunbar

and

Robin Ian MacDonald Dunbar

Published 2 Nov 2010

In most traits, you tend to resemble one or the [Page 14] other, so that by and large you end up as a kind of mosaic – your mother’s nose, your father’s chin, perhaps even your grandfather’s hair through some quirk of a throw-back to earlier generations. All this is pretty well understood, thanks mainly to the pioneering efforts in the 1850s of that indefatigable scientist-monk, Gregor Mendel, the founding father of modern genetics. Now, one might expect that you would be a random mosaic of bits inherited from your two parents, and that these would vary between individuals – half the population would inherit a particular trait from their fathers, and the rest would inherit it from their mothers.

A Short History of Nearly Everything

by

Bill Bryson

Published 5 May 2003

Huxley likewise parodied the younger Haldane in his novel Antic Hay, but also used his ideas on genetic manipulation of humans as the basis for the plot of Brave New World. Among many other achievements, Haldane played a central role in marrying Darwinian principles of evolution to the genetic work of Gregor Mendel to produce what is known to geneticists as the Modern Synthesis. Perhaps uniquely among human beings, the younger Haldane found World War I “a very enjoyable experience” and freely admitted that he “enjoyed the opportunity of killing people.” He was himself wounded twice. After the war he became a successful popularizer of science and wrote twenty-three books (as well as over four hundred scientific papers).

…

Lucky flukes might arise from time to time, but they would soon vanish under the general impulse to bring everything back to a stable mediocrity. If natural selection were to work, some alternative, unconsidered mechanism was required. Unknown to Darwin and everyone else, eight hundred miles away in a tranquil corner of Middle Europe a retiring monk named Gregor Mendel was coming up with the solution. Mendel was born in 1822 to a humble farming family in a backwater of the Austrian empire in what is now the Czech Republic. Schoolbooks once portrayed him as a simple but observant provincial monk whose discoveries were largely serendipitous—the result of noticing some interesting traits of inheritance while pottering about with pea plants in the monastery's kitchen garden.

The Locavore's Dilemma

by

Pierre Desrochers

and

Hiroko Shimizu

Published 29 May 2012

Monsanto is not known for being nimble in its relations with the public, but the company made sure that none of the donated seed was genetically altered. That gesture wasn’t enough; protests quickly erupted all over Haiti and the U.S. You would have thought Monsanto was passing out free cigarettes to teenagers. “Peasant groups” in Haiti marched under banners of “Down with GMO and hybrid seeds.” Hybridization has been around since Gregor Mendel experimented with peas in the 1850s. Hybrid crops have saved the lives of billions of hungry people. Farmers in the U.S. began adopting hybrid seeds in the 1920s, and hybrids have increased yields for every crop that lends itself to hybridization. Donating hybrid seeds is not exactly pushing the envelope of food or farming technology, but breeding and producing hybrid seed is a complicated process typically done by large firms and never by individual farmers.

Endless Forms Most Beautiful: The New Science of Evo Devo

by

Sean B. Carroll

Published 10 Apr 2005

Because embryology was stalled for so long, it played no part in the so-called Modern Synthesis of evolutionary thought that emerged in the 1930s and 1940s. In the decades after Darwin, biologists struggled to understand the mechanisms of evolution. At the time of The Origin of Species , the mechanism for the inheritance of traits was not known. Gregor Mendel’s work was rediscovered decades later and genetics did not prosper until well into the 1900s. Different kinds of biologists were approaching evolution at dramatically different scales. Paleontology focused on the largest time scales, the fossil record, and the evolution of higher taxa. Systematists were concerned with the nature of species and the process of speciation.

Erwin Schrodinger and the Quantum Revolution

by

John Gribbin

Published 1 Mar 2012