Hacker Ethic

description: moral values and philosophy that are common in hacker culture

71 results

Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution - 25th Anniversary Edition

by

Steven Levy

Published 18 May 2010

He guessed that the fix was in even before the conference was called to order—a system based on the Hacker Ethic was too drastic a step for those institutions to take. But Greenblatt later insisted that “we could have carried the day if [we’d] really wanted to.” But “charging forward,” as he put it, was more important. It was simply not a priority for Greenblatt to spread the Hacker Ethic much beyond the boundaries of Cambridge. He considered it much more important to focus on the society at Tech Square, the hacker Utopia which would stun the world by applying the Hacker Ethic to create ever more perfect systems. Chapter 7. Life They would later call it a Golden Age of hacking, this marvelous existence on the ninth floor of Tech Square.

…

Wizards Full-screen editing, The Third Generation Fuller, Buckminster, Revolt in 2100, Revolt in 2100, Every Man a God, The Homebrew Computer Club Fusion-io, Afterword: 2010 G Galactic Saga game, The Brotherhood Galaxian game, The Brotherhood, Summer Camp Gamma Scientific company, The Third Generation, The Third Generation Gardner, Martin, Life Garetz, Shag, Spacewar Garland, Harry, The Homebrew Computer Club, The Homebrew Computer Club Garriott, Owen K., Applefest Garriott, Richard, Applefest, Applefest, Applefest Gates, Bill, Tiny BASIC, Tiny BASIC, Frogger, Afterword: 2010, Afterword: 2010, Afterword: 2010 Gebelli, Nasir, The Brotherhood, Frogger General Electric Science Fair, The Tech Model Railroad Club George Jackson People’s Free Clinic, Revolt in 2100 Glider gun, Life GNU operating system, Afterword: 2010 Gobbler game, The Third Generation Godbout, Bill, Every Man a God Going public, The Wizard and the Princess Gold panning, Frogger Golden, Vinnie “the Bear”, Every Man a God Google, Afterword: 2010 Gorlin, Dan, Frogger Gosper, Bill, Spacewar, Greenblatt and Gosper, Greenblatt and Gosper, Greenblatt and Gosper, Winners and Losers, Winners and Losers, Life, Life, Afterword: 2010 Graham, Paul, Afterword: 2010 Great Subway Hack, Winners and Losers, Life Greenblatt, Richard, Greenblatt and Gosper, Greenblatt and Gosper, Greenblatt and Gosper, Greenblatt and Gosper, Winners and Losers, Winners and Losers, Life, Life, Life, Life, The Wizard and the Princess, Afterword: 2010 Griffin, Kathy, Afterword: 2010 Gronk, Winners and Losers Guinness Book of World Records, Frogger Gulf & Western Conglomerate, Sega division, Frogger H Hack, The Tech Model Railroad Club Hackathons, Afterword: 2010 HACKER (Sussman program), Winners and Losers Hacker Dojo, Afterword: 2010 Hacker Ethic, The Hacker Ethic, The Hacker Ethic, Spacewar, Greenblatt and Gosper, The Midnight Computer Wiring Society, Winners and Losers, Life, Life, Revolt in 2100, Revolt in 2100, Every Man a God, Every Man a God, The Homebrew Computer Club, The Homebrew Computer Club, Tiny BASIC, Secrets, Secrets, The Wizard and the Princess, The Brotherhood, The Brotherhood, The Brotherhood, The Third Generation, Frogger, Frogger, Applefest, Applefest, Wizard vs.

…

Horowitz of computer keyboards, master math and LIFE hacker at MIT AI lab, guru of the Hacker Ethic, and student of Chinese restaurant menus. Richard Greenblatt. Single-minded, unkempt, prolific, and canonical MIT hacker who went into night phase so often that he zorched his academic career. The hacker’s hacker. John Harris. The young Atari 800 game hacker who became Sierra On-Line’s star programmer, but yearned for female companionship. IBM PC. IBM’s entry into the personal computer market, which amazingly included a bit of the Hacker Ethic and took over. IBM 704. IBM was The Enemy and this was its machine, the Hulking Giant computer in MIT’s Building 26.

Coding Freedom: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Hacking

by

E. Gabriella Coleman

Published 25 Nov 2012

Yet almost all academic and journalistic work on hackers commonly whitewashes these differences, and defines all hackers as sharing a singular “hacker ethic.” Offering the first definition in Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, journalist Steven Levy (1984, 39) discovered among a couple of generations of MIT hackers a unique as well as “daring symbiosis between man and machine,” where hackers placed the desire to tinker, learn, and create technical beauty above all other goals. The hacker ethic is shorthand for a list of tenets, and it includes a mix of aesthetic and pragmatic imperatives: a commitment to information freedom, a mistrust of authority, a heightened dedication to meritocracy, and the firm belief that computers can be the basis for beauty and a better world (ibid., 39–46).

…

That’s a nice thought.”11 As I delved deeper into the cultural politics of hacking, though, I began to see serious limitations in making any straightforward connections between the hacker ethic of the past and the free software of the present (much less other hacker practices). Most obviously, to do so is to overlook how ethical precepts take actual form and, more crucially, how they transform over time. For example, in the early 1980s, “the precepts of this revolutionary Hacker Ethic,” Levy (1984, 39; emphasis added) observes, “were not so much debated and discussed as silently agreed upon. No Manifestos were issued.” Yet (and somewhat ironically) a mere year after the publication of his book, MIT programmer Richard Stallman charted the Free Software Foundation (FSF) ([1996] 2010) and issued “The GNU Manifesto,” insisting “that the golden rule requires that if I like a program I must share it with other people who like it.”12 Today, hacker manifestos are commonplace.

…

And now many hackers recognize ethical precepts as one important engine driving their productive practices—a central theme to be explored in this book. Additionally, and as the Mitnick example provided above illustrates so well, the story of the hacker ethic works to elide the tensions that exist among hackers as well as the different genealogies of hacking. Although hacker ethical principles may have a common core—one might even say a general ethos—ethnographic inquiry soon demonstrates that similar to any cultural sphere, we can easily identify great variance, ambiguity, and even serious points of contention.

Free as in Freedom

by

Sam Williams

Published 16 Nov 2015

At a time when the Reagan Administration was rushing to dismantle many of the federal regulations and spending programs that had been built up during the half century following the Great Depression, more than a few software programmers saw the hacker ethic as anticompetitive and, by extension, un-American. At best, it was a throwback to the anticorporate attitudes of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Like a Wall Street banker discovering an old tie-dyed shirt hiding between French-cuffed shirts and double-breasted suits, many computer programmers treated the hacker ethic as an embarrassing reminder of an idealistic age. For a man who had spent the entire 1960s as an embarrassing throwback to the 1950s, Stallman didn't mind living out of step with his peers.

…

Recognizing the utility of this feature, Wall put the following copyright notice in the program's accompanying README file: Copyright (c) 1985, Larry Wall You may copy the trn kit in whole or in part as long as you don't try to make money off it, or pretend that you wrote it.See Trn Kit README. http://www.za.debian.org/doc/trn/trnreadme Such statements, while reflective of the hacker ethic, also reflected the difficulty of translating the loose, informal nature of that ethic into the rigid, legal language of copyright. In writing the GNU Emacs License, 108 Stallman had done more than close up the escape hatch that permitted proprietary offshoots. He had expressed the hacker ethic in a manner understandable to both lawyer and hacker alike. It wasn't long, Gilmore says, before other hackers began discussing ways to "port" the GNU Emacs License over to their own programs.

…

To be a hacker, a person had to do more than write interesting software; a person had to belong to the hacker "culture" and honor its traditions the same way a medieval wine maker might pledge membership to a vintners' guild. The social structure wasn't as rigidly outlined as that of a guild, but hackers at elite institutions such as MIT, Stanford, and Carnegie Mellon began to speak openly of a "hacker ethic": the yet-unwritten rules that governed a hacker's day-to-day behavior. In the 1984 book Hackers, author Steven Levy, after much research and consultation, codified the hacker ethic as five core hacker tenets. In many ways, the core tenets listed by Levy continue to define the culture of computer hacking. Still, the guild-like image of the hacker community was undermined by the overwhelmingly populist bias of the 175 software industry.

From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism

by

Fred Turner

Published 31 Aug 2006

As Levy explains, MIT and DEC had “an easy arrangement,” since “the Right Thing to do was make sure that any good program got the fullest exposure possible because information was free and the world would only be improved by its accelerated flow.”62 Tak i n g t h e W h o l e E a r t h D i g i t a l [ 135 ] This ethic also accorded well with the values espoused in the Whole Earth Catalog. Like the Catalog, the hacker ethic suggested that access to tools could change the world, first by changing the individual’s “life for the better” and, second, by creating art and beauty. In keeping with the Catalog’s habit of systems thinking, the hacker ethic characterized the tools themselves as prototypes: the computer was a rule-bound system that could serve as a model of the world; to study computers was to learn something about the world at large. Like the Catalog, the hacker ethic suggested that work should be organized in a decentralized manner and that individual ability, rather than credentials obtained from institutions, should determine the nature of one’s work and one’s authority.

…

Most had come to meet others like themselves. Their hosts offered them food, computers, audiovisual supplies, and places to sleep— and a regular round of facilitated conversations. By all accounts, two themes dominated those conversations: the definition of a hacker ethic and the description of emerging business forms in the computer industry. The two themes were, of course, entwined. The hacker ethic that Levy described—the single thread ostensibly running through all of the participants’ careers—had emerged at a moment when sharing products and processes improved profits for all. By the mid-1980s, however, the finances of computer and software development had changed radically.

…

Others, including Macintosh designer Bill Atkinson, defended corporate prerogatives, arguing that no one should be forced to give away the code at the heart of their software. The debate took on particular intensity because, according to the hacker ethic, certain business practices—like giving away your code—allowed you to claim the identity of hacker. In part for this reason, participants in a morning-long forum called “The Future of the Hacker Ethic,” led by Levy, began to focus on other elements of the hacker’s personality and to modify their stance on the free distribution of information goods. For instance, participants agreed that hackers were driven to compute and that they would regard people who impeded their computing as bureaucrats rather than legitimate authorities.

Peers, Pirates, and Persuasion: Rhetoric in the Peer-To-Peer Debates

by

John Logie

Published 29 Dec 2006

Levy’s account of the first generation of hackers not only expressly positions hackers as the latest in a long line of American explorers, it also suggests stridently that their motivations, like those of the astronauts, were ultimately to offer something of value “for all mankind.” This is especially apparent in Levy’s codification of the “Hacker Ethic,” a summation of the shared principles adhered to by the majority of the first generation of hackers. According to Levy, the generally recognized principles of the Hacker Ethic were: • Access to computers—and anything which might teach you something about the way the world works—should be unlimited and total. • Always yield to the Hands-on Imperative! • All information should be free. • Mistrust authority—promote decentralization. • Hackers should be judged by their hacking, not bogus criteria such as degrees, age, race or position. • You can create art and beauty on a computer. • Computers can change your life for the better. (39–45) In Levy’s articulation of the Hacker Ethic it is possible to trace the convergence of the U.S.’s historic valorization of exploration, exemplified at the time by the space program, with the idealistic social visions that grew out of the youth culture of the 1960s.

…

Rather, they are contested sites where interested parties struggle to frame the activities at the heart of the term according to their preferences and perceived needs. In the introduction to his 2002 book Hacker Culture, Douglas Thomas writes that “the very definition of the term ‘hacker’ is widely and fiercely disputed by both critics of and participants in the computer underground” (ix). In a similar vein, in the preface to his 2001 book, The Hacker Ethic, Pekka Himanen offers a compressed account of the key shifts in the use of the term: [A] group of MIT’s passionate programmers started calling themselves hackers in the early sixties. (Later, in the mid-eighties, the media started applying the term to computer criminals. In order to avoid the confusion with virus writers and intruders into information systems, hackers began calling these destructive computer users crackers.

…

• All information should be free. • Mistrust authority—promote decentralization. • Hackers should be judged by their hacking, not bogus criteria such as degrees, age, race or position. • You can create art and beauty on a computer. • Computers can change your life for the better. (39–45) In Levy’s articulation of the Hacker Ethic it is possible to trace the convergence of the U.S.’s historic valorization of exploration, exemplified at the time by the space program, with the idealistic social visions that grew out of the youth culture of the 1960s. While at first blush, the quasi-militaristic personae of the astronauts would appear to be wholly at odds with the politics of hippie/yippie cultures, both NASA and hippie leaders foregrounded their commitments to exploration in their personal and public presentations.

The Misfit Economy: Lessons in Creativity From Pirates, Hackers, Gangsters and Other Informal Entrepreneurs

by

Alexa Clay

and

Kyra Maya Phillips

Published 23 Jun 2015

Facebook has built a testing platform that allows employees to, at any given time, try thousands upon thousands of versions of Facebook’s website. Wrote Zuckerberg: “We have the words ‘Done is better than perfect’ painted on our walls to remind ourselves to always keep chipping.” With Facebook claiming a hacker ethic, we can certainly see the risk of corporations who look to co-opt hacker subculture. But co-optation is only one of the ways in which the hacker movement is mainstreaming. A lot of the hacker ethic is still oriented around disruptive innovation and challenging the underlying logics and norms of the establishment, and these are the cases we’re interested in—the hackers who are changing systems.

…

Misfit innovators may be their own bosses or operate in networks or communities where they feel they have the ability to help shape the rules they live by. Some open-source and hacker communities have become experts at creating their own operating principles. For example, the original hackers, the group of misfits at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, organically developed what is known as the Hacker Ethic, a code according to which they would operate: the importance of free access to computers, freedom of information, decentralization, and judgment based solely on merit. Every hacker we spoke to gave a nod to these principles, stating that they still animate many of the hacker movements today. WHY MISFITS ARE NEEDED NOW MORE THAN EVER Many of the principles we see operating in the Misfit Economy have emerged in direct opposition to the legacy of formalization born of the Industrial Revolution some two hundred and fifty years ago.

…

He starts with the first iteration of hackers: the group who coalesced during the early 1960s, when the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) acquired its first programmable computer. This cohort’s obsessive programming of the machines, and the relationship they built with the systems, gave rise to the Hacker Ethic, an informal, organically developed and agreed-upon manifesto that, in several iterations, still drives the hacker movement forward: • Access to computers—and anything that might teach you something about the way the world works—should be unlimited and total. • All information should be free

The Charisma Machine: The Life, Death, and Legacy of One Laptop Per Child

by

Morgan G. Ames

Published 19 Nov 2019

Bringing in the social and legal ramifications of hacking, critical media theorist Helen Nissenbaum discusses how this hacker identity is contested and has changed from being positive and countercultural in the 1980s to one associated with criminality outside of hacker circles in the 1990s due to changes in the computing industry, hacker values, laws, and popular culture (Nissenbaum, “Hackers and the Contested Ontology of Cyberspace”). Taking a different route, Swedish philosopher Pekka Himanen redefines the “hacker ethic” as a play-based work ethic in contrast to the Protestant work ethic (Himanen, Hacker Ethic). The ethos that originated at MIT, which is central in this account, has influenced groups far beyond those hackers. It was independently developed (with some variation), Levy says, on the West Coast among a group of “hardware hackers” and would go on to be shared by many across the computer hardware and software businesses in Silicon Valley.

…

Antiauthority and the Glorification of Healthy Rebellion The deep distrust of school apparent in these descriptions of constructionism reflects the hacker community’s mistrust of authority figures more generally—a mistrust so codified in the culture that Steven Levy canonized it in two of the six tenets of what he called the “hacker ethic.” Levy described this ethic, the core principles of the hacker community, drawing on the time he spent with the hacker group at MIT; the ethic was subsequently embraced by many in the hacker world. The third tenet reads, “Mistrust authority; promote decentralization,” and the fourth is “Hackers should be judged by their hacking, not bogus criteria such as degrees, age, race, sex, or position.”76 This group decried school as an example of the authority they distrusted; instead, they found great solace in computers and celebrated others who felt the same.

…

At the same time, Papert did not specifically exclude girls; his writing includes occasional examples of girls and speaks in general terms about “children.” Mindstorms and Papert’s other publications on constructionism discuss how programming can be “artistic,” like writing poetry. On the one hand, this echoes the values of the male-dominated hacker group of which he counted himself a member and was even mentioned in Levy’s hacker ethic. On the other hand, this could open up the field to different ways of knowing. Papert and his third wife, fellow MIT professor Sherry Turkle, explored this in relation to gender specifically. Their article “Epistemological Pluralism” attempts to separate computer programming skills from what they acknowledge is a masculine technical culture by discussing more “concrete” and “bricolage”-focused methods of learning to program, which they claimed that women and girls prefer.99 Likewise, many members of the broader constructionism community including Cynthia Solomon, Sylvia Weir, Yasmin Kafai, Ricarose Roque, and more have focused specifically on how constructionism might better appeal to girls and other diverse groups.

The Idealist: Aaron Swartz and the Rise of Free Culture on the Internet

by

Justin Peters

Published 11 Feb 2013

This munificent ideology was encoded into what the author Steven Levy described in his insightful book Hackers as the “hacker ethic.” Hackers—a term for early computer programmers—wrote computer code and believed that other hackers should share their code and computing resources with their peers. This policy was, in part, a pragmatic one: at the time, computing resources were scarce, and possessiveness impeded productivity. But the attitude was also a conscious philosophical choice, a statement that the world ought to be open, efficient, and collaborative. Nowhere was this hacker ethic taken more seriously than at the Artificial Intelligence (AI) Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

…

In the early 1980s, at the dawn of the personal-computing era, some of the AI Lab’s hackers defected to a company called Symbolics, where they constructed commercial versions of the machines they once built at MIT. Others went to a competing firm. The AI Lab hacking corps dwindled, and its motivating principles came to seem increasingly obsolete. For Stallman, these defections only reinforced his commitment to free software. Stallman believed that proprietary software was inimical to the hacker ethic, and that it impeded the free flow of knowledge. Treating software users strictly as customers rather than potential collaborators implied that the public could contribute nothing of value but money. “The rule made by the owners of proprietary software was, ‘If you share with your neighbor, you are a pirate.

…

“It should be obvious that if laws such as [the Copyright Term Extension Act] continued to be passed every 20 years or so, that nothing will ever enter into Public Domain status again and the work of people such as the Internet Wiretap, the Online Book Initiative, and Project Gutenberg will soon be over,” Hart wrote to supporters at the time.75 Just as the AI Lab exodus in the early 1980s had threatened the survival of the hacker ethic, the popularization of the Web in the mid-1990s—and the concurrent emergence of its commercial potential—threatened to marginalize the digital utopians who had been its first colonists. “While I certainly lay no claims to inventing the Internet, I was the first I have ever heard of to understand what it was to become over the first few decades of its existence,” Hart wrote on his blog.

Masters of Deception: The Gang That Ruled Cyberspace

by

Michelle Slatalla

and

Joshua Quittner

Published 15 Jan 1995

In its place appeared a challenge born of fluctuating hormones and adolescent invincibility: ACID PHREAK: There is no one hacker ethic. The hacker of old sought to find what the computer itself could do. There was nothing illegal about that. Today, hackers and phreaks are drawn to specific, often corporate, systems. It's no wonder everyone on the other side is getting mad. We're always one step ahead. Even as he typed, Eli was defining himself, creating his own new hacker ethic. It was a philosophy in which exploration for the sake of discovery is its own justification. And it was also a philosophy in which he saw himself as the baddest gunslinger to ever ride into town.

…

For someone else, it might have all sorts of catastrophic appeal. You could do anything, even cut off phone service to the whole Laurelton neighborhood. But that's anathema to them; they'd no sooner crash a computer system than they would cut off a finger. That's what they tell each other. They believe in the hacker ethic: Thou shalt not destroy. It's OK to look around, but don't hurt anything. It's good enough just to be here. It's late now, the mission has turned into an all-nighter, and it's the bold hour when all the authority figures they've ever known are already asleep, oblivious to the escalation of the shared kinetic energy in this room.

…

Paul wondered if The Graduate ever told his parents what happened, or if he waited in fear for the Secret Service to return. The other boys didn't mention the incident, didn't talk about how whatever they did that day got away from them. It was an odd experience, crashing something. Even a lamer board. Never would any of the three have harmed a system intentionally. Never would any of them have violated the hacker ethic by destroying anything. They only mentioned the experience obliquely after that. Whenever something struck them as weird and inexplicable, this is what they would say: "Plik. " The summer had turned out to be a great one. By the time August rolled around, Paul, Mark, and Eli felt as if they'd known one another forever.

Collaborative Society

by

Dariusz Jemielniak

and

Aleksandra Przegalinska

Published 18 Feb 2020

Thompson et al., “Inside the Two Years That Shook Facebook—and the World,” Wired February 12, 2018. 52. ”More Snowden Leaks Reveal Hacking by NSA and GCHQ against Communications Firm.” Network Security (2015): 1–2. 53. https://perma.cc/HXA4-XVKU 54. T. Jordan and P. Taylor, Hacktivism and Cyberwars (Routledge, 2004). 55. P. S. Ryan, “War, Peace, or Stalemate: Wargames, Wardialing, Wardriving, and the Emerging Market for Hacker Ethics,” Virginia Journal of Law and Technology 9 (2004): 41. 56. P. Himanen, The Hacker Ethic (Random House, 2010). Chapter 6 1. D. Innerarity, The Democracy of Knowledge (Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2013). 2. I. B. Cohen, “Commentary: The Fear and Distrust of Science in Historical Perspective,” Science, Technology, & Human Values 6 (1981): 20–24. 3.

…

To the developers of ARPANET, sharing knowledge proved more productive than trading information.16 “Sharing” was also understood literally, as the early computer systems were premised on the collaborative use of hardware, and the culture of sending demos and software on floppy drives by mail long preceded online piracy.17 The “hacker ethic,” sparked by joining forces in imaginative ways, foregrounded radical openness, decentralization, and collaboration.18 Most tech developers understood collaboration and peer production broadly, as the heart of the net’s innovative capacities, and viewed encapsulated proprietary networks as limiting them.19 Marcus Felson and Joe L.

…

“Hacking a win is a question of principle,” Virginia Heffernan wrote in Wired in January 2018. When hacking is all about outsmarting the system and finding its flaws, it does not necessarily correspond with something that society would perceive as a greater good. As P. S. Ryan explained it, summarizing the preface of Steven Levy’s 1984 book Hackers, the general tenets or principles of hacker ethic include sharing, openness, decentralization, free access to computers, and world improvement, but especially the upholding of democracy and the fundamental laws most live by as a society.55 Moreover, these rules frequently incorporate unlimited and full access to computers, and to anything that might teach us how the world works.56 Thus, perhaps the most promising way of thinking about the future of hacktivism is to picture it as a sandbox of possibilities that retains freedom and a desired degree of online anonymity, supplemented by the ethos of openness and voluntary cooperation for a good cause.

We-Think: Mass Innovation, Not Mass Production

by

Charles Leadbeater

Published 9 Dec 2010

The Internet as we know it was built on an ethic of mutual self-help with the all purpose, reprogrammable personal computer as the main point of access. Yet if the personal computer is replaced with less open, adaptable devices – like the Apple iPhone – then it will be far harder for hackers, amateurs and kids to innovate at the edges of the system. The Apple personal computer helps people to create; it feeds the mutual, self-help, hacker ethic of the web. The Apple iPhone, the iPod and iTunes are very different. What you can do depends on what Apple allows you to do. The Apple iPhone is a seductively dangerous little tool. If the future web is accessed through constrained mobile devices then it will be considerably less free and easy than it has been to date.

…

Are you building your own computer … if so you might like to come to a gathering of people with like-minded interests, exchange information, swap ideas, talk shop, help work on a project, whatever … The club’s first meeting, in French’s garage, attracted 32 people, six of whom had built their own computers. The club embodied the hacker ethic: people making things for themselves and helping one another to do the same. Twenty-three high-tech companies can trace their lineage to this club of do-it-yourself amateurs, among them Apple. Fred Moore died in a car crash in 1997 at the age of 55, largely unknown, and yet he helped to shape modern America: the original student protester and co-founder of the club that spawned much of the digital revolution we now live with.

…

Hackers are suspicious of corporate brands and want to undertake self-governing craftwork.15 They do not want to be managed, nor do they want to be commercial. This is where it all starts to get rather confusing. More companies will try to follow Apple and persuade people to become fans of their products by claiming to have a hacker ethic beating inside them. Google is the prime exponent of this conjuring trick: never has the hacker spirit generated so much profit. Companies that create fans will, however, find them hacking their software and generating their own content and will be left wondering how to react. Lego, the Danish toy-brick company, found that a fan had hacked the software for its Mindstorms robots and made improvements that were proving popular with other players.

Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Created an Empire and Transformed Pop Culture

by

David Kushner

Published 2 Jan 2003

“Though some in the field used the term hacker as a form of a derision,” Lew wrote in the preface, “implying that hackers were either nerdy social outcasts or ‘unprofessional’ programmers who wrote dirty, ‘nonstandard’ computer code, I found them quite different. Beneath their often unimposing exteriors, they were adventurers, visionaries, risk-takers, artists … and the ones who most clearly saw why the computer was a truly revolutionary tool.” This Hacker Ethic read like a manifesto. When Carmack finished the book one night in bed, he had one thought: I’m supposed to be in there! He was a Whiz Kid. But he was in a nowhere house, in a nowhere school, with no good computers, no hacker culture at all. He soon found others who sympathized with his anger.

…

Though only in his forties, Al had a receding hairline with strands sticking up as if he had just taken his hands off one of those static electricity spheres found at state fairs. He dressed in muted ties and sweaters but possessed the eccentric streak shared by the students and faculty he would visit in the university computer lab during his job there in seventies. At the time the Hacker Ethic was reverberating from MIT to Silicon Valley. As head of the academic computing section at the school, Al, by vocation and passion, was plugged in from the start. He wasn’t tall or fat, but the kids affectionately called him Big Al. Energized by this emerging Zeitgeist, in 1981 Al and another LSUS mathematician, Jim Mangham, hatched a business scheme: a computer software subscription club.

…

Al assumed Carmack was trying to protect his own financial interests, but in reality he had struck what was growing into an increasingly raw nerve for the young, idealistic programmer. It was one of the few things that could truly make him angry. It was ingrained in his bones since his first reading of the Hacker Ethic. All of science and technology and culture and learning and academics is built upon using the work that others have done before, Carmack thought. But to take a patenting approach and say it’s like, well, this idea is my idea, you cannot extend this idea in anyway, because I own this idea–it just seems so fundamentally wrong.

Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events

by

Robert J. Shiller

Published 14 Oct 2019

Bitcoin is a contagious counternarrative because it exemplifies the impressive inventions that a free, anarchist society would eventually develop. The term hacker ethic is another modern embodiment of such anarchism. Before the widespread availability of the World Wide Web, sociologist Andrew Ross wrote, in 1991, The hacker ethic, first articulated in the 1950s among the famous MIT students who developed multiple-access user systems, is libertarian and crypto-anarchist in its right-to-know principles and its advocacy of decentralized technology.6 In his 2001 book The Hacker Ethic and the Spirit of the Information Age, Pekka Himanen wrote about the ethic of the “passionate programmers.”7 In the Internet age, people’s willingness and ability to work together with new technology—in new frameworks that do not rely on government, on conventional profit, or on lawyers—have surprised many of us.

…

F., 294 grand narrative, 92 Grant, James, 242, 251 Grant, Ulysses S., 157 The Grapes of Wrath (Steinbeck), 131 The Great Crash, 1929 (Galbraith), 233 Great Depression of 1930s, 111–12; angry narratives in, 239; bimetallism epidemic during, 23; blamed on loss of confidence, 130; blamed on “reckless talk” by opinion leaders, 127; confidence narratives in, 114, 122; consumption demand reduced after, 307n3; crowd psychology and suggestibility in understanding of, 120; deportation of Mexican Americans during, 190; depression of 1920–21 and, 243, 251–53; difficulty of cutting wages during, 251–52; Dust Bowl and, 130–31; fair wage narrative during, 250; family morale during, 138–39; fear during, 109, 127–28, 141; flu epidemic of 1918 mirroring trajectory of, 108; frequency of appearance of the term, 133, 134f; frugality and compassion in, 135, 136–37, 140–43, 252; gold standard narrative during, 158–59; labor-saving machinery and, 174; lists of causes created at the time, 129–30; modern theories about causes of, 132–33; modesty narrative during, 135, 136–37, 139, 142–45, 147–48, 150; narratives after 2007–9 crisis and, 95; narratives focused on scarcity during, 129; narratives illuminating causes of, ix–x; not called “Great Depression” at the time, 133–34; not forecast by economists, xiv; ordinary people’s talking about, 90–91; photos providing memory of, 131; prolonged by avoidance of consumption, 139, 142, 144–46; as record-holder of economic downturns, 112; revulsion against excesses of 1920s during, 235–36; robot tax discussed during, 209; seen as stampede or panic, 128; technocracy movement and, 193–94; technological unemployment narrative and, 183, 184; today’s downturns seen through narratives of, 134–35, 264; underconsumption narrative during, 188–90; women’s writing about concerns during, 137–40, 145–46 The Great Illusion (Angell), 95 Great Recession of 1973–75, 112 Great Recession of 1980–82, 112 Great Recession of 2007–9, 112; bank failures as key narratives in, 132; fear about intelligent machines and, 273; fueled by real estate narratives, 212; predicted by few economists, xiv; rapid drop in confidence during, 272 Great Society, 50 Greenspan, Alan, 227 Gresham’s Law, and bimetallism, 169, 313n27 hacker ethic, 7 The Hacker Ethic and the Spirit of the Information Age (Himanen), 7 Hackett, Catherine, 140, 253–54 Halley, Edmund, 124 “Happy Birthday to You” (song), 97–100 Harari, Yuval Noah, 208 Harding, Warren, 244–45 “hard times,” 134 Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression (Terkel), 234 Harris, Sidney J., 263 Harvey, William Hope, 161, 162, 312n10 Hazlitt, Henry, 247 “Heads I win, tails you lose,” 110 health interventions, narrative presentation of, 78 Heathcote, Jonathan, 214 Heffetz, Ori, 144 Hepburn, Katharine, 201 Hero of Alexandria, 175 Hicks, John, 24, 26 Hill, Napoleon, 121–22 Himanen, Pekka, 7 historical databases, 279; of letters and diaries, 285 historical scholarship: compared with historical novel, 79; economics learning from, 78; use of narrative by, 14, 37 Hitler, Adolf, 122, 142, 195 HIV (human immune deficiency virus), 24; coinfective with tuberculosis, 294–95 Hoar, George Frisbie, 178 Hoffa, Jimmy, 260 Hofstadter, Douglas R., 47 Hofstadter, Richard, 36 Hollande, François, 151 Holmes, Oliver Wendell, Jr., 127 Holtby, Winifred, 140 homeownership: advantages over renting, 223, 317n18; advertising promotions for, 219–20; American Dream narrative and, 154–55; condominium conversion boom and, 223–24; seen as investment by many buyers, 226–27 home price indexes, 97, 215–16, 222 home price narratives, 215–17; declining by 2012, 227; fueling a speculative boom, 217–18, 222, 223–24 home prices: available on the Internet, 218; construction costs and, 215, 317n6; falling dramatically with financial crisis of 2007–9, 223; only going up, xii; price of land and, 215; ProQuest references to, 213–14, 216; rising again from 2012 to 2018, 223, 225; social comparison and, 218, 220; supply of housing and, 222; supply of land and, 221–22; surge leading up to financial crisis of 2007–9, 222–23.

…

“Regime Uncertainty: Why the Great Depression Lasted So Long and Why Prosperity Resumed after the War.” Independent Review 1(4):561–90, http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/24560785.pdf. Hill, Napoleon. 1925. The Law of Success in 16 Lessons. New York: Tribeca Books. ________. 1937. Think and Grow Rich. Meriden, CT: The Ralston Society. Himanen, Pekka. 2001. The Hacker Ethic and the Spirit of the Information Age. New York: Random House. Hofstadter, Douglas R. 1980. Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. New York: Vintage Books. ________. 1981. “Metamagical Themas: The Magic Cube’s Cubies Are Twiddled by Cubists and Solved by Cubemeisters.” Scientific American 244(3):20–39.

What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry

by

John Markoff

Published 1 Jan 2005

Musicologist John Chowning, who at SAIL invented the technology that underlies modern music synthesizers, called it a “Socratean abode.” SAIL embodied what University of California computer scientist and former SAIL systems programmer Brian Harvey called the “hacker aesthetic.” Harvey’s description was a reaction to what Steven Levy in Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution had described as a “hacker ethic,” which he characterized as the unspoken manifesto of the MIT hackers: Access to computers—and anything which might teach you something about the way the world works—should be unlimited and total. Always yield to the Hands-On Imperative! All information should be free. Mistrust Authority—Promote Decentralization.

…

You must also epoxy the pieces of paper to the desk.”11 And yet, he demurred that when Richard Stallman, one of MIT’s best-known hackers, stated that information should be free, Stallman’s ideal wasn’t based on the idea of property as theft—an ethical position—but instead on the understanding that keeping information secret is inefficient: “it leads to unaesthetic duplication of effort.”12 Anyone who has spent time around the computer community, particularly as it evolved, will recognize that both writers are correct. Points were given for style, but there was a deeper substance, an ethical stance that has become a formidable force in the modern world of computing. Perhaps no one better represented both the hacker ethic and its aesthetic than Les Earnest. He had worked for the MITRE Corporation. In 1962, he was “loaned” to the CIA and several other intelligence agencies to help integrate various military computer systems. Not surprisingly, an individual with a deeply rooted hacker sensibility was never a perfect fit with a military-intelligence bureaucracy.

…

Hafner, Katie, and Matthew Lyon. Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins of the Internet. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996. Hajdu, David. Positively 4th Street: The Lives and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Fariña, and Richard Fariña. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001. Himanen, Pekka. The Hacker Ethic, and the Spirit of the Information Age. New York: Random House, 2001. Lee, Martin A., and Bruce Shlain. Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD: The CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond. New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1992. Levy, Steven. Crypto: How the Code Rebels Beat the Government, Saving Privacy in the Digital Age.

Valley of Genius: The Uncensored History of Silicon Valley (As Told by the Hackers, Founders, and Freaks Who Made It Boom)

by

Adam Fisher

Published 9 Jul 2018

ISBNs: 978-1-4555-5902-2 (hardcover), 978-1-4555-5901-5 (ebook), 978-1-5387-1449-2 (international trade) E3-20180511-JV-NF Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Epigraph PREFACE Silicon Valley, Explained: The story of the past, as told by the people of the future BOOK ONE Among the Computer Bums The Big Bang: Everything starts with Doug Engelbart Ready Player One: The first T-shirt tycoon The Time Machine: Inventing the future at Xerox PARC Breakout: Jobs and Woz change the game Towel Designers: Atari’s high-strung prima donnas PARC Opens the Kimono: Good artists copy, great artists steal 3P1C F41L: It’s game over for Atari Hello, I’m Macintosh: It sure is great to get out of that bag Fumbling the Future: Who blew it: Xerox PARC—or Steve Jobs? BOOK TWO The Hacker Ethic What Information Wants: Heroes of the computer revolution The Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link: Welcome to the restaurant at the end of the universe Reality Check: The new new thing—that wasn’t From Insanely Great to Greatly Insane: General Magic mentors a generation The Bengali Typhoon: Wired’s revolution of the month Toy Stories: From PARC to Pixar Jerry Garcia’s Last Words: Netscape opened at what?!

…

Bruce Horn: We’re waiting for the right thing to happen to have the same type of mind-blowing experience that we were able to show the Apple people at PARC. There’s some work being done, but it’s very tough. And, yeah, I feel somewhat responsible. On the other hand, if somebody like Alan Kay couldn’t make it happen, how can I make it happen? BOOK TWO THE HACKER ETHIC We are as gods and might as well get good at it. —STEWART BRAND What Information Wants Heroes of the computer revolution By the mideighties, the technologists who were creating the future in Silicon Valley started to see themselves as more than simply engineers. Alvy Ray Smith and his midnight crew at Xerox PARC, the game makers at Atari, and the Macintosh team at Apple all became convinced that they were pioneers in a new expressive medium.

…

But the cool thing was seeing him explain it and show it off to other hackers and see that this was actually the currency, this was the dynamic. He was doing stuff and giving it out to everybody: “Yeah, here’s a copy of it.” And they were going to go and hack on it some more. It was just the very thesis that Steven was talking about in his book, this hacker ethic of sharing and building upon in an open-source sense and there it was. It was right there. Steven Levy: It was just like endless demos and showing people things and cool stuff. They hooked up the games. David Levitt: Amazing games no one had ever seen before. Fabrice Florin: They were up until the wee hours just showing off stuff, discussing, hacking, teaching each other how to do stuff.

Coders: The Making of a New Tribe and the Remaking of the World

by

Clive Thompson

Published 26 Mar 2019

Using a $120,000 machine to play a video game would likely have seemed, to computer-makers at the time, a madly frivolous thing to do. But the MIT hackers regarded themselves as liberating programming from its mundane history of mere bean counting and scientific problem-solving. Coding itself, they felt, was a playful, artistic act. They were establishing, as Levy described it, a “hacker ethic.” They believed that there was a hands-on imperative, that everyone in the world ought to be allowed to interact directly with a computer. They also believed in radical openness with code: If you wrote something useful, you should freely share it with others. (This spirit of openness extended to the physical world: When MIT authorities locked cabinets with equipment they needed to fix the computer, they studied lock picking and liberated the equipment.)

…

Right now, though, the truth is that there are oodles of young people from all walks of life who want in. They admire tech’s self-image as a meritocracy; they crave a field that’s truly like that. Indeed, few people are hungrier for a true meritocracy than those who’ve historically been sealed out of so many industries and so many other opportunities. An industry run truly on hacker ethics—of being judged purely on the quality of your running code, with no one remarking on your identity? That would be a thrilling utopia for them. If the world of programming actually lived up to its implicit ideals, it would be a beacon for any historically screwed-over group. Indeed, that’s precisely why previously picked-on nerd boys found it so glorious when they stumbled upon it in the ’80s.

…

“of the sun or moon it was”: Levy, Hackers, 139. a $120,000 machine: Russell Brandom, “ ‘Spacewar!’: The Story of the World’s First Digital Video Game,” The Verge, February 4, 2013, accessed August 16, 2018, https://www.theverge.com/2013/2/4/3949524/the-story-of-the-worlds-first-digital-video-game. a “hacker ethic”: Levy, Hackers, 26–37. “hacking in general”: Levy, Hackers, 107. tinker with the code: “GNU General Public License,” Free Software Foundation, June 29, 2007, accessed August 16, 2018, https://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl-3.0.en.html. “bunch of other robots”: Levy, Hackers, 129. like the MIT hackers: Clive Thompson, “Steve Wozniak’s Apple I Booted Up a Tech Revolution,” Smithsonian, March 2016, accessed August 18, 2018, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/steve-wozniaks-apple-i-booted-up-tech-revolution-180958112/.

The Wikipedia Revolution: How a Bunch of Nobodies Created the World's Greatest Encyclopedia

by

Andrew Lih

Published 5 Jul 2010

A basic LISP program looked something like this: (defun factorial (n) (if (< = n 1) 1 (* n (factorial (- n 1))))) It was so easy to learn, though hard to master. Many consider it the most elegant computer language around because of its simplicity. To understand Stallman’s view on the world, you have to understand the computer hacker ethic. The computing culture at MIT and other top scientific schools was one of sharing and openness. These institutions were full of people, after all, who were pursuing software programming not for dollar profits, but for the love of discovery and pioneering new solutions to problems. Worried little about where to live or when the next paycheck was arriving, these students could hun- A_Nupedia_25 ker down in a cloistered academic environment and concentrate on their programming creations.

…

Worried little about where to live or when the next paycheck was arriving, these students could hun- A_Nupedia_25 ker down in a cloistered academic environment and concentrate on their programming creations. Hackers would regularly improve how the emerging LISP language and its tools worked, and let everyone in the academic community know by allowing them to share and download new improvements over computer networks that predated the Internet. This was an important part of the hacker ethic: sharing to improve human knowledge. Changes and modifications were put in the public domain for all to partake in. Researchers would improve the work of others and recontribute the work back into the community. In the 1980s, before it became commercial, the Internet was made up of these educational institutions and research labs in which academics and engineers transferred software packages or improvement “patches” of files back and forth as part of hacker camaraderie.

…

Eric Raymond, in A Brief History of Hackerdom, describes the creation during the ARPANET days of the Jargon File, another precursor to Wikipedia’s group-edited document: The first intentional artifacts of the hacker culture—the first slang list, the first satires, the first self-conscious discussions of the hacker ethic—all propagated on the ARPANET in its early years. In particular, the first version of the Jargon File (http://www.tuxedo .org/jargon) developed as a cross-net collaboration during 1973–1975. This slang dictionary became one of the culture’s defining documents. It was eventually published as The New Hacker’s Dictionary. 86_The_Wikipedia_Revolution The Jargon File was much beloved by the hacker community and passed along like a family heirloom, with prominent computer scientists such as Richard Stallman, Guy Steele, and Dave Lebling all having a major hand in its editing.

The Pirate's Dilemma: How Youth Culture Is Reinventing Capitalism

by

Matt Mason

The customized information that lawyers, doctors, and teachers give will still be expensive; this isn't about undermining their ability to earn money. What's actually being undermined is the very idea of why we work. When Work Stops Working The success of open-source initiatives proves that money isn't the only thing making the world go 'round. As Pekka Himanen observes in The Hacker Ethic, capitalism is based on the notion that it is our duty to work. The nature of the work doesn't matter; it's just about doing it. This notion, first suggested by St. Benedict, an abbot in the sixth century, evolved into the Western work ethic (where we do work that doesn't always matter most to us, but it's for money rather than the monastery).

…

We live in a world that has been governed by competition for several millennia, but increasingly competition has to compete with cooperation. Work-centeredness was long ago replaced with self-centeredness, but this drive to express ourselves is also forging a new community spirit. As Linus Torvalds writes in The Hacker Ethic, “The reason that Linux hackers do something is that they find it to be very interesting and they like to share this interesting thing with others. Suddenly you both get entertainment from the fact you are doing something interesting, and you get the social part.” Our work ethic is more of a play ethic.

…

Stephanie Dunnewind, “Teachers are reaching out to students with a new class of blogs,” Seattle Times, October 14, 2006. http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/living/2003303937_teachblog14.html. Don Tapscott and Anthony D. Williams, Wikinomics (New York: Portfolio Hardcover, 2006), p. 157. Andy Patrizio, “PlayStation 3 Users Power on to Cure Disease,” InternetNews.com, April 5, 2007. http://www.internetnews.com/bus-news/article.php/3670066. Pekka Himanen, The Hacker Ethic and the Spirit of the Information Age (New York: Random House, 2002). This book is a fantastic read; the quote from Linus Torvalds can be found on p. xv. Don Tapscott and Anthony D. Williams, Wikinomics (New York: Portfolio Hardcover, 2006), front flap. CHAPTER 6 REAL TALK: How Hip-Hop Makes Billions and Could Bring About World Peace The Diddy and Burger King clip (which has since been posted back up) can be viewed at http://www.youtube.com/watch?

Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution

by

Howard Rheingold

Published 24 Dec 2011

It all started with the original hackers in the early 1960s. Before the word “hacker” was misappropriated to describe people who break into computer systems, the term was coined (in the early 1960s) to describe people who create computer systems. The first people to call themselves hackers were loyal to an informal social contract called “the hacker ethic.” As Steven Levy described it, this ethic included these principles: Access to computers should be unlimited and total. Always yield to the Hands-On Imperative. All information should be free. Mistrust authority—promote decentralization.45 Without that ethic, there probably wouldn’t have been an Internet to commercialize.

…

The foundations of the Internet were created by the community of creators as a gift to the community of users. In the 1960s, the community of users was the same as the community of creators, so self-interest and public goods were identical, but hackers foresaw a day when their tools would be used by a wider population.48 Understanding the hacker ethic and the way in which the Internet was built to function as a commons are essential to forecasting where tomorrow’s technologies of cooperation might come from and what might encourage or limit their use. Originally, software was included with the hardware that computer manufacturers sold to customers—mainframe computers attended by special operators.

…

Based on GNU, all of Torvalds’s code was open according to the GPL, and Torvalds took the fateful step of posting his work to the Net and asking others for help. The kernel, known as Linux, drew hundreds, then thousands of young programmers. By the 1990s, opposition to the monolithic domination of the computer operating system market by Microsoft became a motivating factor for rebellious young programmers who had taken up the torch of the hacker ethic. “Open source” refers to software, but it also refers to a method for developing software and a philosophy of how to maintain a public good. Eric Raymond wrote about the difference between “cathedral and bazaar” approaches to complex software development: The most important feature of Linux, however, was not technical but sociological.

Hacking Capitalism

by

Söderberg, Johan; Söderberg, Johan;

It is noteworthy that the belief of early socialists, that humanity would be liberated from scarcity thanks to the development of the forces of production, is resurfacing in the technophilia of many hackers. When they reflect upon the ramifications of their hobby they tend to be heavily influenced by notions about the ‘affluent society’.1 The underlying assumption, explicitly argued in Pekka Himanen’s The Hacker Ethic, is that the ‘high-tech gift economy’ on the Internet has emerged as a consequence of the abundant wealth in industrialised economies. Himanen is typical in referring to the psychologist Abraham Maslow’s work on human motivation from the 1950s. According to Maslow, human needs can be arranged in a hierarchy where primacy is assigned to those needs that are most urgently requiring to satisfy for a human being when he lacks everything.

…

For a critical view of how the blurring of work and passion, i.e. the hacker spirit, is taken advantage of by shareholders at the expense of disillusioned, burned-out employees, see Andrew Ross’ study of webdesigners working in advertising bureaus. No-Collar—The Human Workplace and its Hidden Costs (Philadelphia: Temple University Press 2004), Pekka Himanen, The Hacker Ethic—The Spirit of the Information Age (London: Secker & Warburg, 2001). 67. Dennies Hayes, Behind the Silicon Curtain—The Seduction of Work in a Lonely Era (London: Free Association Books, 1989), 85. 68. The tendency was noticeable within the computer industry already in the 1970s when Philip Kraft examined how the computer profession was being transformed by an intensified technical division of labour.

…

Behind the Silicon Curtain—The Seduction of Work in a Lonely Era, London: Free Association Books, 1989. Heller, Agnes. The Theory of Need in Marx, New York: St. Martin’s Publisher, 1976. Hemmungs, Eva. No Trespassing—Authorship, Intellectual Property Rights, and the Boundaries of Globalization, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004. Himanen, Pekka. The Hacker Ethic—The Spirit of the Information Age, London: Secker & Warburg, 2001. Hippel, Eric, Democratising Innovation, Cambridge Mass.: MIT Press, 2005. Hirsch, Fred. Social Limits to Growth, London: Routledge, 1995. Hobsbawm, Eric. Bandits, London: Ebenezer Baylis & Son, 1969. ed. Hoekman, Bernard, and Michel Kostecki.

Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy

by

Jonathan Taplin

Published 17 Apr 2017

The early WELL guidelines were very clear about intellectual property, as stated on the log-on screen: “You own your own words. This means that you are responsible for the words you post on the WELL, and that reproduction of those words without your permission in any medium outside the WELL’s conferencing system may be challenged by you, the author.” But in 1989 something weird happened. The notion of the “hacker ethic” became a contested trope. It started with an online forum on the WELL organized by Harper’s Magazine. The subject was hacking, and Paul Tough, a Harper’s editor, had recruited Brand and a few of his most important WELL members, including Howard Rheingold, Kevin Kelly, and John Perry Barlow, to participate.

…

On January 24, 1990, the Secret Service raided the apartment where Acid Phreak was living with his mother. By the end of the day Acid Phreak, Phiber Optik, and a third hacker, Scorpion, were in a New York City jail, accused of hacking the main AT&T computer system. And that is where Brand, Barlow, and their fellow communards changed course. Instead of recalibrating the hacker ethic in line with their earlier goals, they embraced the criminals on the theory that theirs was really a victimless crime. Tell that to AT&T, which had to spend millions restoring its system. Barlow went on to form the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which has never met a hacker it couldn’t defend.

Common Knowledge?: An Ethnography of Wikipedia

by

Dariusz Jemielniak

Published 13 May 2014

Participation in virtual communities of practice, such as free/libre-and-opensource-software (F/LOSS) projects and other open-collaboration communities, has major influence on enculturation and shaping the shared values of the participants. For example, the Debian hacker ethic is to a huge extent socially constructed and strengthened in communal interactions in opposition to the traditional market-based concept of intellectual property (Coleman & Hill, 2005). It revolves around the strong belief in personal freedom (Coleman & Golub, 2008). Pekka Himanen describes the hacker ethic, a characteristic of the emerging network society (2001). This new paradigm is based on cooperation and joint production and is transforming the economy and society (Benkler, 2006b).

…

Retrieved from http:// www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0065782 Hill, B. M., Shaw, A., & Benkler, Y. (2013). Status, social signaling and collective action in a peer production community. Unpublished manuscript, Berkman Center for Internet and Society working paper, Cambridge, MA. Himanen, P. (2001). The hacker ethic and the spirit of the information age. New York: Random House. Hine, C. (2000). Virtual ethnography. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Hine, C. (2008). Virtual ethnography: Modes, varieties, affordances. In N. Fielding, R. M. Lee, & G. Blank (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods (pp. 257–270).

Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity

by

Daron Acemoglu

and

Simon Johnson

Published 15 May 2023

—Wassily Leontief, “Technological Advance, Economic Growth, and the Distribution of Income,” 1983 The beginnings of the computer revolution can be found on the ninth floor of MIT’s Tech Square building. In 1959‒1960, a group of often-unkempt young men coded there in assembly language into the early hours of the morning. They were driven by a vision, sometimes referred to as the “hacker ethic,” which foreshadowed what came to energize Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. Key to this ethic was decentralization and freedom. Hackers felt great disdain for the major computer company of that era, IBM (International Business Machines). In their view, IBM wanted to control and bureaucratize information, whereas they believed that access to computers should be completely free and unlimited.

…

The answer to the second also builds on these institutional changes but crucially involves the emergence of a new utopian (but in reality, largely dystopian) digital vision, which pushed technologies and practices in an increasingly antilabor direction. In the next several sections we start with the institutional developments and return to how the idealistic hacker ethic of the 1960s and 1970s morphed into an agenda for automation and worker disempowerment. The Liberal Establishment and Its Discontents We saw in Chapter 7 how a sort of balance between business and organized labor emerged in the United States after the 1930s. It was undergirded by robust wage growth across jobs ranging from the unskilled to the highly skilled, and by a broadly worker-friendly direction of technology.

…

Thus, despite variation across countries, the direction of progress in the US has had a significant global impact. Digital Utopia The direction of technology that prioritized automation cannot be understood unless we recognize the new digital vision that emerged in the 1980s. This vision combined the drive to cut labor costs, rooted in the Friedman doctrine, with elements of the hacker ethic, but abandoned the philosophy of early hackers such as Lee Felsenstein that was antielitist and suspicious of corporate power. Felsenstein admonished IBM and other big corporations because they were trying to misuse technology with their ideology of “design by geniuses for use by idiots.” The new vision instead embraced the top-down design of digital technologies aimed at eliminating people from the production process.

Explore Everything

by

Bradley Garrett

Published 7 Oct 2013

As people become more curious about what a post-capitalist world would look like, urban explorers can supply imaginative depictions.36 * * * * To see and hear the actual demolition of West Park recorded by urban explorer Gina Soden, go to youtube.com/watch?v=qwEgaAz6uFQ (‘The Sounds of Demolition’). Chapter 4 THE RISE OF AN INFILTRATION CREW ‘There is no one hacker ethic. Everyone has his own. To say that we all think the same way is preposterous.’ – Acid Phreak It was the beginning of what was to be a long, cold winter in 2009. Team B explorers received information that a mothballed thirty-five-acre Ministry of Defence (MOD) nuclear bunker had been breached.

…

Alex and Laura showed us how to dig properly, and before we knew it we had an assembly line going: the person digging ‘point’ pushed dirt out to the people widening walls, who put it in buckets and gave it to the people on break eating pizza and drinking Samuel Adams, where eventually it was dumped in sledges, which got dragged outside. We dug for six hours in frenzied rotation. Alex reckoned we might have gone forward a metre. Just as the hacker ethic cannot be simplistically reified, categorised or bounded, neither can explorers themselves. While universally shared motivations behind exploration exist, such as friendship or geography, it is impossible to define a coordinated explorer ethos; individuals simply follow their desires and do their own edgework.

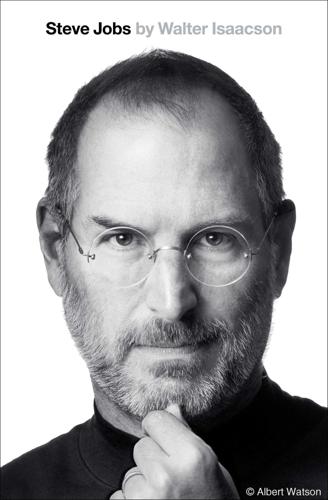

The Innovators: How a Group of Inventors, Hackers, Geniuses and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution

by

Walter Isaacson

Published 6 Oct 2014

119 The simple answer was that the computer, as it ran the programs, produced frequency interference that could be controlled by the timing loops and picked up as tone pulses by an AM radio. By the time his query was published, Gates had been thrown into a more fundamental dispute with the Homebrew Computer Club. It became archetypal of the clash between the commercial ethic that believed in keeping information proprietary, represented by Gates, and the hacker ethic of sharing information freely, represented by the Homebrew crowd. Paul Allen (1953– ) and Bill Gates (1955– ) in the Lakeside school’s computer room. Gates arrested for speeding, 1977. The Microsoft team, with Gates at bottom left and Allen at bottom right, just before leaving Albuquerque in December 1978.

…

They agreed to meet when Bricklin, who lived in Boston, came to an O’Reilly conference in San Francisco. Over sushi at a nearby restaurant, Bricklin told the tale of how, years earlier, when his own company was foundering, he had run into Mitch Kapor of Lotus. Though competitors, they shared a collaborative hacker ethic, so Kapor offered a deal that helped Bricklin stay personally solvent. Bricklin went on to found a company, Trellix, that made its own website publishing system. Paying forward Kapor’s band-of-hackers helpfulness to a semicompetitor, Bricklin worked out a deal for Trellix to license Blogger’s software for $40,000, thus keeping it alive.

…

As the technology journalist Steven Johnson has noted, “their open architecture allows others to build more easily on top of existing ideas, just as Berners-Lee built the Web on top of the Internet.”33 This commons-based production by peer networks was driven not by financial incentives but by other forms of reward and satisfaction. The values of commons-based sharing and of private enterprise often conflict, most notably over the extent to which innovations should be patent-protected. The commons crowd had its roots in the hacker ethic that emanated from the MIT Tech Model Railroad Club and the Homebrew Computer Club. Steve Wozniak was an exemplar. He went to Homebrew meetings to show off the computer circuit he built, and he handed out freely the schematics so that others could use and improve it. But his neighborhood pal Steve Jobs, who began accompanying him to the meetings, convinced him that they should quit sharing the invention and instead build and sell it.

Too Big to Know: Rethinking Knowledge Now That the Facts Aren't the Facts, Experts Are Everywhere, and the Smartest Person in the Room Is the Room

by

David Weinberger

Published 14 Jul 2011

Frauenfelder does not attribute this growth in interest to the Web directly. Rather, he says, in the past few years, “some of the folks who had been spending all their time creating the Web, and everything on it, looked up from their monitors and realized that the world itself was the ultimate hackable platform.” Maker Faire embodies the hacker ethic and aesthetics that have driven the Web and the culture of the Web. And there is no doubt that even for those who do not want to do the sort of science that involves both hacksaws and bags of marshmallows—marshmallow guns are a signature Maker artifact—the Web has been a godsend for the amateur scientist.

…

Fortune magazine Foucault, Michel Frauenfelder, Mark FuelEconomy.gov Future Shock (Toffler) The Futurist journal Galapagos Islands Galaxy Zoo Galen of Pergamum Garfield, Eugene Gartner Group GBIF.org (Global Biodiversity Information Facility) Geek news General Electric Gentzkow, Matthew Gillmor, Dan Gladwell, Malcolm Glazer, Nathan Global social problems Goals, shared Google abundance of knowledge amateur scientists’ use of books and filtering information physical books and e-books zettabyte Gore, Al Gray, Jim Greece, ancient Green peas Group polarization Groupthink The Guardian newspaper Gulf of Mexico oil spill The Gutenberg Elegies (Birkerts) Habermas, Jürgen Hacker ethic Hague conference Haiti Halberstam, David Hannay, Timo Hard Times (Dickens) Hargittai, Eszter Harrison, John Harvard Library Innovation Lab Haumea (planet) Hawaii Heidegger, Martin Heidegger Circle Henning, Victor Heywood, Stephen Hidary, Jack Hillis, Danny Hilscher, Emily H1N1 virus Holtzblatt, Les Home economics Homophily Howe, Jeff Human Genome Project Humors Hunch.com Hyperlinks linked knowledge providing data links IBM computers Impact factor of scientific journals In vitro fertilization An Inconvenient Truth (film) Information crowd-sourcing data and networking information for fund managers Open Government Initiative reliability of Information Anxiety (Wurman) Information cascades Information overload as filter failure consequences of metadata value of information Infrastructure of knowledge InnoCentive Institutions, Net response to Insularity of Net users Intelligence Internet increasing stupidity providing hooks for Intelligence agencies Intelligent Design International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration Internet abundance of knowledge amateur scientists challenging beliefs crowds and mobs cumulative nature of data sharing diversity of expertise echo chambers forking Hunch.com improving the knowledge environment increasing institutional use indefinite scaling information information filtering interpretations knowledge residing in the network LA Times wikitorial experiment linked knowledge loss of body of knowledge permission-free knowledge public nature of knowledge reliability of information scientific inquiry shaping knowledge shared experiences sub-networks The WELL conversation unresolved knowledge See also Networked knowledge Interpretations, knowledge as iPhone Iraq Jamming Jarvis, Jeff Jellies de Joinville, Jean Journals, scientific Kahn, Herman Kantor, Jodi Kelly, Kevin Kennedy, Ted Kennedy administration Kepler, Johannes Kindle Kitano, Hiroaki Knowledge abundance of as interpretation changing shape of crisis of echo chambers hiding enduring characteristics of environmental niche modeling fact-based and analogy-based human pursuit of hyperlinked context improving the Internet environment Internet challenging beliefs linked permission-free public reason as the path to social elements of stopping points unresolved Knowledge clubs Kuhn, Thomas Kundra, Vivek Kutcher, Ashton Lakhani, Karim Language games Latour, Bruno Leadership Debian network decision-making and Dickover’s social solutions network distribution Lebkowsky, Jon Leibniz, Gottfried Lessig, Lawrence Levy-Shoemaker comet Librarians Library of Congress Library use Lili’uokalani (Hawaiian queen) Linked Data standard Linked knowledge Links filters as See also Hyperlinks Linnean Society Linux Lipson, Hod Literacies Loganathan, G.V.

Protocol: how control exists after decentralization

by

Alexander R. Galloway

Published 1 Apr 2004

Hacking 151 risk-takers, artists . . . and the ones who most clearly saw why the computer was a truly revolutionary tool.”9 These types of hackers are freedom fighters, living by the dictum that data wants to be free.10 Information should not be owned, and even if it is, noninvasive browsing of such information hurts no one. After all, hackers merely exploit preexisting holes made by clumsily constructed code.11 And wouldn’t the revelation of such holes actually improve data security for everyone involved? Levy distilled this so-called hacker ethic into several key points: Access to computers . . . should be unlimited and total. All information should be free. Mistrust authority—promote decentralization. Hackers should be judged by their hacking, not bogus criteria such as degrees, age, race, or position. You can create art and beauty on a computer.

…

For more details on the Mitnick story, see the following texts: Katie Hafner and John Markoff, Cyberpunk: Outlaws and Hackers on the Computer Frontier (New York: Touchstone, 1991); Tsu- Chapter 5 170 A British hacker named Dr-K hardens this sentiment into an explicit anticommercialism when he writes that “[c]orporations and government cannot be trusted to use computer technology for the benefit of ordinary people.”59 It is for this reason that the Free Software Foundation was established in 1985. It is for this reason that so much of the non-PC computer community is dominated by free, or otherwise de-commercialized software.60 The hacker ethic thus begets utopia simply through its rejection of all commercial mandates. However, greater than this anti-commercialism is a pro-protocolism. Protocol, by definition, is open source, the term given to a technology that makes public the source code used in its creation. That is to say, protocol is nothing but an elaborate instruction list of how a given technology should work, from the inside out, from the top to the bottom, as exemplified in the RFCs described in chapter 4.

Black Code: Inside the Battle for Cyberspace

by

Ronald J. Deibert

Published 13 May 2013

A hacker was someone who did not accept technology at face value, and who experimented with technical systems, exploring their limits and possibilities: that is, a hacker opened up technical systems and explored their inner workings. This original positive idea of hacking is what I had in mind in setting out to create a research hothouse that would bring together computer and social scientists. Hacktivism by my definition is the combination of social and political activism with that original hacker ethic, and this captures the gist of what I was hoping for in founding the Citizen Lab. Oriented around a specific set of values that would inform our research, as I saw it (and still do) hacktivism has a lot in common with a philosophical tradition stretching back to the ecological holism of Harold Innis, the pragmatism and experimentalism of William James and John Dewey, and the yearning for a return to a polytechnic culture of the early Renaissance articulated by Lewis Mumford.

…

That is, “computer hacking” is used unquestioningly to describe anyone who breaks the law or causes a ruckus in cyberspace. The association of the term with criminality is not just a semantic issue; it represents a much larger delegitimization of the underlying philosophy of experimentation at the heart of the hacker ethic. And herein lies an enormously important paradox, one that sits at the heart of our technologically saturated world: we have created a communications environment that is utterly dependent on existing (and emerging) technologies, and yet, at the same time, we are actively discouraging experimentation with, and an understanding of, these technologies.

Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars From 4Chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right

by

Angela Nagle

Published 6 Jun 2017

In the US, one of the early cases of orchestrated attacks against such encroaching women was aimed at Kathy Sierra, a tech blogger and journalist. Sierra had been the keynote speaker at South by Southwest Interactive and her books were top sellers. The backlash against her was sparked when she supported a call to moderate reader comments, which at the time was seen as undermining the libertarian hacker ethic of absolute Internet freedom, although it has since become standard. Commenters on her blog began harassing and threatening her en mass, making the now routine rape and death threats received by women like Sierra. Personal details about her family and home address were posted online and hateful responses included photoshopped images of her with a noose beside her head, a shooting target pointed at her face and a creepy image of her being gagged with women’s underwear.

Tools for Thought: The History and Future of Mind-Expanding Technology

by

Howard Rheingold

Published 14 May 2000

"Phone-hacking" was another kind of prank pioneered by MAC hackers in the early 1960s that was to spawn anarchic variants in the 1970s. The self-taught mastery of complex technologies is the hallmark of the hacker's obsession, the conviction that all information (and information delivery technologies) ought to be free is a central tenet of the hacker ethical code, and the global telephone network is a complex technological system par excellence, a kind of ad hoc worldwide computer. The fact that a tone generator and a knowledge of switching circuits could provide access to long-distance lines, free of charge, led to a number of legendary phone hacks.

…

By separating the inference engine from the body of factual knowledge, it became possible to produce expert tools for expert-systems builders, thus bootstrapping the state of the art. While these exotic programs might seem to be distant from the mainstream of research into interactive computer systems, expert-systems research sprouted in the same laboratories that created time-sharing, chess playing programs, Spacewar, and the hacker ethic. DENDRAL had grown out of earlier work at MIT (MAC, actually) on programs for performing higher level mathematical functions like proving theorems. It became clear, with the success of DENDRAL and MYCIN, that these programs could be useful to people outside the realm of computer science. It also became clear that the kind of nontechnical questions that Weizenbaum and others had raised in regard to AI were going to be raised when this new subfield became more widely known.

The Best of 2600: A Hacker Odyssey

by

Emmanuel Goldstein

Published 28 Jul 2008

Yet there are, nonetheless, subtle distinctions of badness, which allow the audience to draw markedly different conclusions concerning the morality of each of the characters. So it is that in Masters we meet some teenagers, all of whom commit crimes (at least, in the legal sense), all of whom belong to an exclusive hacking group, yet each retaining an individual moral sense in both spirit and action of what the hacker ethic entails. It is in terms of these two realms— that of the individual and that of the group—that Masters attempts to deconstruct the 239 94192c08.qxd 6/3/08 3:32 PM Page 240 240 Chapter 8 story of MOD, sometimes stressing one over the other, sometimes integrating the two, but always implying that both are integral to understanding what has become the most notorious network saga since that of Robert Morris and the Internet worm.

…

Readers will remember Mitnick as the spiteful and vindictive teenager featured in Katie Hafner and John Markoff’s Cyberpunk: Computers and Outlaws on the Electronic Frontier. At the time of its release, Cyberpunk’s portrayal of Mitnick was thought to be biased, allegedly because Mitnick was the only hacker featured who refused to be interviewed. Biased or not, he was portrayed by the authors as a “Dark Side” hacker, and the antithesis of the hacker ethic. He was considered more evil than Pengo, a West Berlin hacker who sold his knowledge of American systems on the Internet to the Russians for cash. But Mitnick’s worse crime, by comparison, seemed only to be a lack of respect for anyone who was not up to his level of computer expertise, and few people were.

…