Islamic Golden Age

description: period of cultural flourishing in the 8th to 13th centuries

36 results

Wonderland: How Play Made the Modern World

by

Steven Johnson

Published 15 Nov 2016

In whatever way, indeed, the power of genius may invent or combine, and to whatever low or even ludicrous purposes that invention or combination may be originally applied, society receives a gift which it can never lose; and though the value of the seed may not be at once recognized; and though it may lie long unproductive in the ungenial till of human knowledge, it will some time or other evolve its germ, and yield to mankind its natural and abundant harvest. —DAVID BREWSTER, Letters on Natural Magic Toys and games are the preludes to serious ideas. —CHARLES EAMES Introduction At Merlin’s You Meet with Delight In the early years of the Islamic Golden Age, around 760 CE, the new leader of the Abbasid Dynasty, Abu Ja’far al-Mansur, began scouting land on the eastern edge of Mesopotamia, looking to build a new capital city from scratch. He settled on a promising stretch of land that lay along a bend in the Tigris River, not far from the location of ancient Babylon.

…

The question of why the Homo sapiens brain possesses this strange hankering for play and surprise is a fascinating one, and I will return to it in the final pages of this book. But for now, we need to establish just how far those playful explorations took us. The bone flutes must have sounded enchanting to the early humans of the Upper Paleolithic. But they were just the beginning. — The Banu Musa—those brilliant toy designers from the Islamic golden age—earned a permanent place in the pantheon of engineering and robotics with their Book of Ingenious Devices. And yet the brothers omitted from that collection what may have been their most ingenious device of all, a machine that would introduce one of the most important concepts of the digital age more than a thousand years before the first computers were built.

…

Games themselves—not the physical manifestation of the game, but the underlying rules—were among the first key cultural dishes to be cooked up in the global melting pot. (In a way, the closest equivalent to chess’s cosmopolitan evolution are the scientific insights that followed a similar geographic path, from the Islamic Renaissance through medieval monasteries to the European Enlightenment, with small but crucial additions and corrections added with each step of the journey.) Once again, a seemingly frivolous custom turns out to be an augur of future developments: if you were an aspiring futurologist in Cessolis’s day and you were looking for clues about the future of invention and commerce—perhaps even a future where virtual encyclopedias would be written and edited by millions of people around the world—a good place to start would be by studying the games people were playing for fun, and the evolution of the rules that governed those games.

Second World: Empires and Influence in the New Global Order

by

Parag Khanna

Published 4 Mar 2008

During Ramadan, day and night are switched, as people fast and rest all day and eat at night. As the custodians of Islam’s holiest sites, Wahhabis consider themselves the only true practitioners of Islam. Saudi culture has been intentionally held back by their effort to return the country to a pure Islamic golden age by destroying all pre-Muhammed artifacts, in some cases burying entire villages. For the Prophet and his disciples, there was no distinction between secular and divine authority, thus even the Wahhabist partnership with the Saudi royal family is an unholy alliance that the Ikhwan (Brethren) must bear since they cannot raise an army.18 Wahhabist radicals’ bombing of oil facilities and declaring fatwas against IPOs are mere symptoms of a far deeper struggle both they and Saudi society at large are enduring to either resist or adjust to global modernity.

…

The same micro-politics of roads and access are also unfolding in Tajikistan, turning the country into another Silk Road rest stop. Precariously perched at the roof of the world in the Pamir Mountains, nestled among Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, and China, Tajikistan is another country that bends in the imperial winds—but with a radical Islamic twist. The country’s Islamic Renaissance Party was the only religious party to be recognized in the former Soviet Union, and in the 1980s it was a rallying point for Tajik nationalism as the Communist elite in the capital, Dushanbe, ironically neglected the very anti-Soviet insurgency in Afghanistan that sparked the collapse of the Soviet Union.

…

In a nearby underground shop, musicians collect and assemble centuries-old instruments used in the hypnotic ensembles that produce Silk Road music: high-pitched flutes, tightly strung guitars, Arabic drums—but no one is there to listen to them. Samarkand’s mighty Registan madrasah, once the center of all parades, festivals, and bazaars under Tamerlane, is today a looming but eerily empty space. Samarkand could become the symbol of a modern Islamic renaissance, again earning the city the appellation of the “second Mecca.” And the Ferghana Valley, the heart of the Silk Road’s mélange of currencies and cuisines, could have become a breadbasket for the region, elevating the farmers of all bordering states. Instead, Uzbekistan is a case study in wasted opportunities and warped ambitions.

Age of Discovery: Navigating the Risks and Rewards of Our New Renaissance

by

Ian Goldin

and

Chris Kutarna

Published 23 May 2016

It’s a phenomenon, a contest, that will shape the whole twenty-first century. Why focus on Europe? Renaissances, as we’ve defined them, can be found in every civilization. What took place in fifteenth-and sixteenth-century Europe has some broad parallels with the Mayan Classic Period (300–900), the early centuries of Korea’s Choso˘n Dynasty (1392–1897), the Islamic Golden Age (750–1260), China’s Tang Dynasty (618–907), India’s Gupta Empire (320–550) and the Mughal Empire under Akbar the Great (1556–1605). We encourage others to embark on the project of looking back to those periods for more insights into our present day. This book draws perspective from a particular moment of the European experience.

…

Once the fire of revolt breaks out, starving it of fuel takes political, social and economic actions as much as military ones, to start fulfilling citizens’ legitimate expectations for a greater dose of opportunity and dignity. Unfortunately, as Savonarola’s death suggests, such outcomes are elusive. An Islamic Renaissance? Stamping out revolt also takes new ideas—and on this front, the future looks brighter. The contest between moderate and extremist modernities is ultimately a battle of ideas, and while the Islamic State’s recent military successes have often been decisive, in the campaign for the hearts and minds of the Arab world, their gains are far less certain.

What We Owe the Future: A Million-Year View

by

William MacAskill

Published 31 Aug 2022

CHAPTER 7 Stagnation Efflorescences In the eleventh century, the world’s epicentre of scientific progress was Baghdad, during an era known as the Islamic Golden Age.1 This era produced an astonishing assortment of discoveries and innovations: we understood for the first time how magnifying lenses work, invented a flywheel-powered water-lifting device, built the earliest programmable machine (a flute-playing automaton), and discovered the first code-breaking method.2 The words “algorithm” and “algebra” both come from Arabic, and even the Hindu-Arabic number system we use (1, 2, 3, etc.), was imported into Europe in the thirteenth century by Fibonacci, who had travelled throughout the Mediterranean world to study under the leading Arabic mathematicians of the time.3 Translated scientific works from the medieval Islamic world are believed to have played a central role in fuelling the Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution in Europe.4 However, the Islamic Golden Age did not last: from the twelfth century AD onwards, the rate of scientific progress slowed considerably.5 There are a number of explanations for why this occurred. Some point to the Mongol invasion; others to the role of the Crusades; others to a cultural shift that encouraged theological work over scientific inquiry.6 The Islamic Golden Age is one example of what historian Jack A. Gold-stone calls an efflorescence: a short-lived period of technological or economic advancement in a single culture or country.7 There have been many efflorescences throughout history.

…

See also GDP income inequality, happiness inequality and, 204–205 inconsistencies in moral worldviews, 67–68 India fertility rate and economic growth, 94 quality of life survey, 199–201 the risks of global conflict, 115 individual actions, the power of, 245–246 industrial development aftermath of Roman decline, 124 carbon concentrations, 24 economic growth rates, 82 effect on wellbeing, 206–207 as efflorescence, 144 fossil fuel consumption and depletion, 138–141 history of humanity, 12–13 postcatastrophe reliance on preindustrial technology, 131–134 sugar and cotton cultivation, 64 upward trend in wellbeing, 207–208 Industrial Revolution economic doubling, 82 fossil fuel depletion, 138–139 global economic growth, 26, 144 impact of the contingency of moral norms, 70 population-technology feedback loop, 153 postcatastrophe recovery, 133 technological development in Europe, 124, 126 upward trend in wellbeing following, 207–208 inequality Easterlin paradox, 201–202 global inequalities, 215 happiness and income inequalities, 204–205 in the total view of wellbeing, 183 inequality, happiness, 204–205 infrastructure, postcatastrophe state of, 130–131, 134 inheritance: cultural evolution, 58–59 innovation automating with AGI, 81, 144 in clean energy, 25 declining rate of, 150–151, 153, 155 Islamic Golden Age, 143 stagnation, 158, 161–162 taking action for the future, 227–228 intelligence, human-level, 57–58 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 24, 39–40, 42 International Energy Agency, 134–135 intuition of neutrality, 171–173, 176–177 invertebrates, 191, 213 investing in the future, 24 Iroquois Confederacy, 11 Ishii, Shiro, 112 Islamic Golden Age, 143, 158 ITN (importance, tractability, neglectedness) framework, 256–257 Jamaican Christmas Rebellion (1831–1832), 69 Japan bioweapons programme, 111–112 the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 126–128 Jerome (saint), 123 Jews and Judaism: the persistence of values, 78 Jones, Chad, 150 Kaufman, Chaim, 64 Kennedy, John F., 37, 128 Khmer Rouge, 60 Kim Il-sung: life extension efforts, 84–85 Korea, division of, 40–41 Kremer, Michael, 152 labour force countering the slowing rate of technological progress, 155–156 economic stagnation, 150 increasing scientific research efforts, 152 women’s participation, 53, 61–62 See also slavery Large Hadron Collider, 151 Lay, Benjamin, 49–51, 72 Learn How to Increase Your Chances of Winning the Lottery (Lustig), 203 learning more, to positively influence the future, 226–227, 235–237 Legalism (China), 76–78 Levy, David, 106 Lewis, Joshua, 199 LGBTQ+ individuals moral views on the status of, 53 transmission of cultural traits, 95 life, evolution of, 117–119 life expectancy among hunter-gatherer societies, 207 changes over time, 205(fig.)

…

But if society stagnates technologically, it could remain stuck in a period of high catastrophic risk for such a long time that extinction or collapse would be all but inevitable. I turn to this possibility in the next chapter. CHAPTER 7 Stagnation Efflorescences In the eleventh century, the world’s epicentre of scientific progress was Baghdad, during an era known as the Islamic Golden Age.1 This era produced an astonishing assortment of discoveries and innovations: we understood for the first time how magnifying lenses work, invented a flywheel-powered water-lifting device, built the earliest programmable machine (a flute-playing automaton), and discovered the first code-breaking method.2 The words “algorithm” and “algebra” both come from Arabic, and even the Hindu-Arabic number system we use (1, 2, 3, etc.), was imported into Europe in the thirteenth century by Fibonacci, who had travelled throughout the Mediterranean world to study under the leading Arabic mathematicians of the time.3 Translated scientific works from the medieval Islamic world are believed to have played a central role in fuelling the Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution in Europe.4 However, the Islamic Golden Age did not last: from the twelfth century AD onwards, the rate of scientific progress slowed considerably.5 There are a number of explanations for why this occurred.

Double Entry: How the Merchants of Venice Shaped the Modern World - and How Their Invention Could Make or Break the Planet

by

Jane Gleeson-White

Published 14 May 2011

Crusades 16, 17, 18 currencies 100 da Gama, Vasco 29 da Pisa, Leonardo see Fibonacci da Vinci, Leonardo 7, 27, 32, 47, 60, 65, 80–2, 84, 87–8 Dafforne, Richard 120–3 Dandolo, Enrico 52 Dark Ages dark arts 35, 83 Darwin, Charles 139, 165 Das Kapital (Marx) 165 Dasgupta, Sir Partha 231–2, 237, 238, 239 Datini, Francesco 23–6, 52, 96 de’ Barbari, Jacopo 79 de’ Belfolci, Folco 34, 44 De divina proportione (Pacioli) 66, 82, 84, 85–6 De ludo scacchorum (Pacioli) 87–8 De pictura (Alberti) 60, 117 De quinque corporibus (Piero) 66 De viribus quantitatis (Pacioli) 83 Dean, Graeme W. 203 debit and credit entries 13, 55, 93–4, 100 difficulties 101–2, 122–3 The Decline of the West (Spengler) 167 Defoe, Daniel 127–8 della Francesca, Piero 7, 32, 34, 44–5, 46, 47 mathematical treatises 45, 66, 75 perspective painting 60, 64, 76–7 della Rovere, Giuliano 59 Deloitte, William 145 Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu 217 demand management 185 democracy 15 depreciation 148, 149, 231 Der moderne Kapitalismus (Sombart) 161–2, 171 derivatives market 198, 200 Descartes, René 40 d’Este, Isabella 83, 84, 88 dividends 144, 146, 147, 148, 149, 202 Doge’s Palace 50, 56 Domenici, Pete V. 191 domestic accounts 15–16 double-entry bookkeeping 8, 115, 120, 166 Badoer’s system 55 and capitalism 159–60, 161–75 and decision-making 126–7 earliest surviving 20–1 to improve the mind 125 link with rhetoric 172–3 in modern era 135–6, 249 origins 6–7, 16, 21–2 Pacioli’s definition 92–3 six essential features 20–1 texts on 117, 136 use by Datini 24, 26 Venetian 55, 67, 97–100, 123–7, 131 see also Particularis de computis et scripturis du Pont, Irénée 156 ducats 50, 55 Dürer, Albrecht 79–80 earnings per share (EPS) 219 earth see planet Earth Earth Summit 2012 248–9 East India Company 142 Ebbers, Bernie 213 eco-accounting 249 economic growth 192–3, 225, 227, 233, 242, 245, 248 economics 185 political economy 171 ecosystems 239–40, 247 education 245 Euclid’s Elements 37–8 quadrivium 36, 38, 43 trivium 38, 43 Egypt 35, 36 Eisenstein, Elizabeth 116–17 Elements (Euclid) 37–8, 39, 67, 68, 84 Elgin Marbles 15 Engels, Friedrich 162, 164, 165 England 116, 121, 131, 133, 147 Enron 3, 173, 194–9, 201, 207, 212–13, 214–16, 222–3 environmental accounting 233–8, 245, 247 environmental damage 222–3, 224–5, 232–3, 240, 241–2, 248 equity 21, 243 Erasmus of Rotterdam 68, 84–5 Erlich, Everett 235 Ernst & Young 209, 210, 216, 217 Espeland, Wendy Nelson 172–3 Euclid, Elements 37–8, 39, 67, 68, 75, 84 Eugenius IV, Pope 34 Europe 17, 20, 21, 22–3, 40, 116, 156, 188 accounting associations 153 currencies 25 medieval 26, 70–1 universities 30, 40, 42 vernacular languages 41 European Environment Agency 247 Evans, John H. 173–5 exchange rates 55 externalities 236 factory system 136–7, 138, 139–41, 165, 166 Farolfi ledger 20–1 Fastow, Andrew 213 Fells, J.M. 140–1 Fibonacci 18–19, 75 Fibonacci numbers 19–20 Liber abaci 19–20, 22, 39–41, 63, 66, 67, 75 Financial Accounting Standards Board (US) 206, 213 financial information 203–6 financial statements 5, 143, 144, 146, 200, 205, 214, 215 Fitoussi, Jean-Paul 243–4 Florence 6, 17, 34, 61, 64, 84 abbaco schools 41 bank ledger 20 expansion of commerce 21 Flugel, Thomas 127 Fondaco dei Tedeschi 56 Ford Motor Company 250–1 forests 240, 241 Forster, E.M. 154–5 Forster, Nathaniel 137 France 147 Franciscans 62, 65, 88, 89 Frankfurt Book Fair 95 Frederick II 95 Freiburg 27 Friedman, Milton 221 fund transfers 54 G20 249 Galileo 116, 166 Geijsbeek, John B. 157–8 General Electric 204 The General Theory of Employment (Keynes) 177–8, 179, 183, 185–6 Genoa 6, 17 geometry 36, 37, 38, 63, 73, 75, 81 Germany 56, 68, 183 Gertner, Jon 244 Giovanni, Enrico 244 Giovanni Farolfi & Co. 20 Glitnir 5 Global Biodiversity Outlook 3 (Sukhdev) global financial crisis (2008) 3, 5, 197, 215, 242, 243–4 globalisation, of finance 206–7, 219, 221 Goethe, Johann W. von 128–31 golden ratio 66, 86 Goodwin, Sir Fred 197 governmental accounting 120 grammar 38, 43 Great Depression 177, 178, 179, 180, 227 Greece, ancient 15 mathematics 34–5, 37–8, 61 philosophers 37 green accounting 244 Green Economy Report (Sukhdev) 248–9 Greenspan, Alan 227–8 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) 3, 180–2, 225, 227–30, 232–3, 235, 237–8, 242–3, 246 alternatives to 243–7, 249 failings of 246 Gross National Product (GNP) 1–3, 181, 190, 231 Groves, Eddy 208–9 Guidobaldo, Duke of Urbino 66, 72, 79, 92 Gutenberg, Johann 68, 77 Hagen, Everett 186 Hamilton, Alexander 22 Hammurabi’s Code 14 Haq, Mahbub ul 245 Henry VIII 25 Herodotus 36 HIH 208, 209, 213, 215 Hindu–Arabic arithmetic 34, 41, 62, 67 Hindu–Arabic numerals 18–19, 21, 26–7, 38, 44, 52, 71, 75 Hoenig, Chris 246–7 honeybee pollination 237 Hoover, Herbert 177 Hopwood, Anthony housework, unpaid 229 How to Pay for the War (Keynes) 182–3 Hudson, George 142–3 human capital 231, 248 Human Development Index 245 Humanism (Florence) 43–4, 59–60, 68 Huxley, Aldous 32–3 income measurement 218–19, 226 income statements 5, 202, 203, 219 in ancient Rome 16–17 see also profit and loss accounts India 29, 238 trade/double entry 22 Indonesia 240 industrial revolution 131, 133, 139, 200, 226 inflation 182, 183 information processing 203 Institute of Accountants and Bookkeepers of New York (IABNY) 156, 157 Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) 153, 205–6 Insull, Samuel 202, 214 Insull Utility Investments 201–2 interest payments 25, 54, 96 international accounting 189, 207 International Accounting Standards Board 207, 214 International Monetary Fund 187 internet 204 inventory 97–9, 101 Islam 22, 39 Italy 6, 7, 16, 19, 28, 167–8 mathematics 34–42, 62 Jerusalem 17 joint stock companies 133, 136, 142, 147, 148 Joint Stock Companies Act 1844 144, 149 Jones, Edward T. 133–6 Jones’ English System of Book-keeping 133–6 journal 99, 100, 101, 103, 118, 203 Julius II, Pope 59 Kennedy, Robert F. 1–3, 229–30, 246 Keynes, John Maynard 8, 176, 177–80, 182–7, 190, 250 Klein, Naomi 221, 233 KPMG 210, 214, 217 Kreuger, Ivar 201 Kreuger & Toll 201 Kublai Khan 18 Kuznets, Simon 2, 177, 180–1, 189, 229 Lanchester, John 4, 198 Landefeld, Steven 228 Landsbanki 5 Latin 35, 41, 63, 71, 72, 73, 74, 116, 220 Lawrence, D.H. 154–5 Lay, Kenneth 195, 196, 197, 212–13, 214 ledgers 20, 93, 99–100, 103–4, 118, 203 14th century 24, 93 Badoer’s 52, 55 balancing 111 closing accounts 111–13 Farolfi 20–1 Lee, G.A. 20–1 Lee, Thomas A. 203 Lehman Brothers 5, 216 Liber abaci (Fibonacci) 19–20, 22, 39–41, 63, 66, 67, 75 limited liability 147–8, 149 Littleton, A.C. 17, 140, 146, 147, 158–9 Liverpool and Manchester Railway 141 Lives of the Most Eminent Painters (Vasari) 46 Living Planet Survey 241–2 Lloyds-HBOS 5 London and North Western Railway 141 Louis XII 82 Machiavelli 30 Mackinnon, Nick 79–80 Madoff, Bernie 142 Madonna and Child with Saints 47 magic 35, 40, 83, 220 Mair, John 118, 125, 130 Malatesta family 33–4, 43 Malthus, Thomas 171 Manchester cotton mill (Engels) 165 Mandela, Nelson 221 Mantua 83, 84 manufacturing 136–41 manuscripts 61, 70, 77 Manutius, Aldus 84 Manzoni, Domenico 118–19 maritime insurance 53 Mark the Evangelist 51–2 marketplace, 15th century 95 markets, impact on politics 221, 228 mark-to-model 213 Marshall Plan 188 Marx, Karl 162, 163–5, 171 mass production 138 mathematics 7, 22, 28, 47, 89–90 ancient Greek 34–5, 37–8, 63 Arab 18–19, 63 and art 85–6 Hindu 39–40 in Italy 34–42 and magic 35, 40, 220 medieval European 63, 251–2 taught as astrology 29–30, 42 universal application 73, 116–17 see also arithmetic Mattessich, Richard 12–13, 186 Maurice, Prince of Orange 120 Maxwell Communications 207 McDonald’s 224 Meade, James 183–4 measurement 23, 218–19 Medici of Florence 26, 64, 80, 168, 171 Mehmed II 57 Mellis, John 121 memorandum (waste book) 99, 101, 118 entering transactions 105–7, 118, 122 merchandise 104 merchant bankers 21, 26, 69 merchants 10, 23, 35, 41 Arab 18–19, 25 Indian 22 Italian 40, 42 Phoenician 36 Venetian 18, 27, 55–6, 69, 94–5, 149 Mesopotamia 12, 13, 14 metaphysics 36–7 Middle Ages 60, 251–2 Milan 30, 34, 47, 61, 80–3 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 239 Monsanto 222 Monteage, Stephen 124, 126 Morgan, John Pierpont 156 multiplication 74, 75–6 music 36, 38 Naples 50, 61–2 Napoleonic War 145 national accounts 175, 179–88, 190–3, 226–7, 230, 242, 244 natural capital 230–1, 235–9 navigation charts 23 Neighborhood Tree Survey (NY) 241, 244 Netherlands 119, 120 New Deal (Roosevelt) 177, 202 New York Light Company 155 New York Stock Exchange 155, 176, 201 New Zealand 153, 230 Nicholas V, Pope 61 No Royal Road: Luca Pacioli and his times (Taylor) 46–7 Nordhaus, William D. 180, 191, 227 numbers 37, 218, 219–20, 249 Obama, Barack 215, 246 O’Grady, Oswald 208 Oldcastle, Hugh 121, 124 Olmert, Michael 168 One.Tel 208, 209, 213, 215 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 190, 242 Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC) 188 Ormerod, Paul 244 Ottoman Empire 29, 34, 50, 51, 56, 57, 116 Pacioli, Luca 7, 8, 27–8, 34, 35, 161, 219 abbaco mathematics 40, 41 as academic 65, 80, 84, 89 astrologer 42 birth 30 bookkeeping treatise see Particularis de computis and Piero della Francesca 45–6, 47–8 education 43–8 encyclopaedia see Summa de arithmetica on Euclid 84–5 games/tricks 83–4 itinerant teacher 61–6 last years 88–90 and Leonardo da Vinci 80–2, 84 in Milan 80–3 portrait 47, 79–80 and the printing press 66–72 remembered in Sansepolcro 31–2 in Rome 58–61 in Venice 49–58 Paganini, Paganino de 67–8, 71–2, 78, 85 painting 60, 64, 81 Pakistan 224, 245 Paris 23, 50 Particularis de computis et scripturis (Pacioli) 29–30, 78, 90–114, 117–18, 121 and capitalism 163 foundation of modern accounting 30, 75, 131, 157–9, 166 profit calculation 146–7 partnerships 108–9, 147 Patel, Raj 222, , 224 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010 (US) 246 patronage 59, 67, 70, 72 Paul II, Pope 59 Payen, Jean-Baptiste 139–40 Peking 18 Perspectiva (Witelo) 64 perspective 23, 42, 45, 60, 64, 76–7, 80, 82 Perugia 62–3, 64, 65 Petty, William 180 phi 86 Philip VI 23 philosophy 37, 40 Phoenicians 36 pi 36 Piazza San Marco 56 Pinto cars 250–1 Pisa 6, 17 Pitcher Partners 209, 210, 211–12 plagiarism 63 planet Earth 8–9, 248 accounting for 254 effects of cost-benefit approach 175 health of 224–5, 239 Plato 37 Platonic solids 45, 79, 86 Pliny the Elder 16 pollution 244 Polly Peck International 207 Polo, Marco 18 Ponzi scheme 142 Postlethwayt, Malachy 124 poverty 237, 246, 248, 249 Prato 23–4 Price, Samuel 145 Price Waterhouse 201, 207 PricewaterhouseCoopers 217 principlism 173–4 printing 29, 45, 60, 63, 66–72, 77–8, 90, 115–17 profit 21, 24, 97, 102–3, 127, 146–8, 159, 161, 167, 169 profit and loss accounts 55, 109–11, 112, 166 Pythagoras 35, 36–7 quadrivium 36, 38, 43 quant nerds 220 railways 141–3, 231 Ramsay, Ian 211 Ratdolt, Erhard 68, 116 record-keeping 15 Reformation 33 regulation 206–14, 215 Reid Murray Holdings 207–8 religion 24, 96, 116, 124–5, 220 see also Christian Church; Islam Renaissance 7, 8, 23, 26, 36, 59, 80, 86, 89, 168 art 6, 7, 44, 60, 86 Resurrection (Piero) 32, 33 retained-earnings statements 5, 219 rhetoric 172–3 Rialto 50, 55, 108 Ricardo, David 171 Rich, Jodee 213 Rinieri Fini & Brothers 20 Ripoli Press 70 Robert of Chester 39 Rockefeller, John D. 156 Roman numerals 19, 26–7, 38, 40, 71, 116 Romantic poets, English 131, 154 Rome 58–61, 64, 89 ancient 15–16 Rompiasi family 57, 58, 97 Roosevelt, Franklin D. 177, 178, 181, 202, 214, 215 Rose, Paul L. 71 Ross, Philip 209–10, 211 Rothschild banks 133 Royal Bank of Scotland 173, 197–8 royal estate management 16–17 Rule of Three 38, 41 Russia 153–4 salt 51 Samuelson, Paul A. 191, 227 Sansepolcro 30–4, 43–4, 48, 65, 77, 88–9, 168 Sanuto, Marco 66, 72 Sarbanes, Paul 191 Sarbanes-Oxley Act 2002 212, 215 Sarkozy, Nicolas 242–3, 245 satellite accounts 234–5 scandals/fraud 194–203, 206, 207–12, 215, 225 Schmandt-Besserat, Denise 11–12 Schumpeter, Joseph 169–70 science 35, 37, 40, 42, 67, 76, 116, 166–7 Scotland 27, 147, 150, 153 Scott, Sir Walter 150–1 Scuola di Rialto 58 Second World War 32, 181–5, 187, 227 Securities and Exchange Commission (US) 202–3, 213, 214 Sen, Amartya 243–4, 245 Sforza, Ludovico 80, 81–2, 85, 86, 168 Sikka, Prem 216, 217 Silberman, Mark 213 Simons, James 220 Sistine Chapel 65 Sixtus IV, Pope 59 Skidelsky, Robert 178, 182, 187 Skilling, Jeffrey K. 196, 197, 212, 214 Smith, Adam 171 social sciences 171, 175 socialism 171 Society of Accountants, Edinburgh 152 Sombart, Werner 161–2, 164, 165–6, 166–8, 169, 170, 171–2, 173 Spain 22, 39 Spengler, Oswald 167 Sri Lanka 232–3, 240 State of the USA 246 Stevin, Simon 120, 121, 166, 169 Stiglitz, Joseph 243–4 Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Commission 243–4 stock markets 143 stocktaking 166 Stone, Sir Richard 183–5, 188–9, 190 sub-prime mortgages Sukhdev, Pavan Summa de arithmetica (Pacioli) 57, 61, 62–3, 64, 72–7, 80, 82 printing 66–8, 71–2 publication 32, 77–9 sustainability 232, 243, 249 System of Integrated Environmental and Economic Accounting (UN) 234 System of National Accounts (UN) 189–90, 247 tabulae rationum 16 Taleb, Nassim N. 220 tariffs 63 Tartaglia, Nicholas 76 Taylor, R.

Horizons: The Global Origins of Modern Science

by

James Poskett

Published 22 Mar 2022

For this reason, historians of science often refer to the period between the ninth and fourteenth centuries as the medieval Islamic ‘golden age’.4 There is, however, a major problem with the idea of an Islamic ‘golden age’. It relies on the false notion that Islamic science – along with Islamic civilization in general – went into a period of decline immediately after the medieval period. This serves to separate out the Muslim world from the story of the scientific revolution, which took place between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries. In fact, as we learned in the introduction to this book, the idea of an Islamic ‘golden age’ had been invented during the nineteenth century in order to justify the expansion of European empires into the Middle East.

…

Recent breakthroughs in physics and chemistry built on a long Islamic tradition, he argued. After all, medieval Islamic thinkers had written a number of important early works of chemistry, whilst many modern chemical terms, such as ‘alkali’, were derived from Arabic. Here, we see how the idea of an Islamic ‘golden age’ was already starting to prove popular amongst Ottoman modernizers. According to the Grand Vizier, the theory of electric current was just another example of ‘the philosophy of the divine’.43 This was all part of a broader strategy to portray the modernization of the Ottoman Empire as part of the modernization of Islam itself.

…

See also individual nation name Eginitis, Demetrios 236 Egypt 6, 51, 52, 60, 62, 64, 71, 111, 175–8, 180, 344, 346; Napoleon invades (1798) 175–9, 183; Revolution (1952) 345; sacred ibis, mummified remains of discovered in 176–8, 177 Einstein, Albert 1, 263–6, 306; Bose–Einstein statistics 300–301; China and 263, 279–84; Germany, leaves 265–6; international collaboration, belief in value of 266, 306; Israel and 264–5; Japan and 263–4; Landau and 276; Relativity: The Special and General Theory 280, 283; Russia and 272–3; Satyendra Nath Bose and 299–301; The Principle of Relativity (Saha/Bose) and 299, 300, 300 electromagnetism 215–17, 218, 220, 222, 223–4, 238, 240, 241, 250, 251, 252, 257, 259, 266, 269, 285, 288 Elektrotekhnik Company, Saint Petersburg 221 El Escorial, Treaty of (1733) 106 Elías, Antón 26 Elías, Baltazar 26 Emirates Mars Mission 362–3 empire: astronomy and mathematics transformed by rise of four great empires (Ottoman, Songhay, Ming, Mughal) 46–93, 47, 54, 56, 62, 65, 75, 83, 89; Bacon links growth of science to 99–100, 101; decolonization 2, 6, 268, 333–4, 345, 365; Enlightenment as age of 2, 98, 105, 124, 133, 134; Indian physics and fight against 295–306, 300; Islamic ‘golden age’ concept invented in order to justify expansion of European empires into the Middle East 3–6, 48–9, 69, 234, 363, 368; natural sciences/botany, influence of upon study of 135–72, 142, 146, 152, 160, 167; slave trade and see slavery; state-sponsored voyages of exploration, Newtonian physics and 101–34, 109, 117, 120, 122, 131, 172.

Gaza in Crisis: Reflections on Israel's War Against the Palestinians

by

Ilan Pappé

,

Noam Chomsky

and

Frank Barat

Published 9 Nov 2010

In his important work on the subject, Stephen Sizer has revealed how Christian Zionists have constructed a historical narrative that describes the Muslim attitude to Christianity throughout the ages as a kind of a genocidal campaign, first against the Jews and then against the Christians.12 Hence, what were once hailed as moments of human triumph in the Middle East—the Islamic renaissance of the Middle Ages, the golden era of the Ottomans, the emergence of Arab independence and the end of European colonialism—were recast as the satanic, anti-Christian acts of heathens. In the new historical view, the United States became St. George, Israel his shield and spear, and Islam their dragon.

The Decadent Society: How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success

by

Ross Douthat

Published 25 Feb 2020

The story of Christian history is one of unexpected resurrections, of what G. K. Chesterton called the “five deaths of the faith” (the fall of Rome, the Muslim challenge, the crisis of the Reformation, the Enlightenment, the march of Darwinism) giving way to unlooked-for renewals and rebirths. So if we imagine religious decadence ending with a new paganism or an Islamic renaissance, we should also imagine it ending with a Christian revival—especially since, for all its weaknesses, Christianity remains institutionally significant, at least for now, in America and Europe on a scale no rival faith can match. In the event that there were a renewal of interest in Christianity within the developed world’s elite, or a grassroots Great Awakening that fills the yawning social void where populism currently flourishes, it would still find a vast preexisting Christian infrastructure, which it might reclaim and fill with newfound zeal, like empty wineskins with new wine.

Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology

by

Adrienne Mayor

Published 27 Nov 2018

International Symposium on History of Machines and Mechanisms. New York: Springer Science + Business Media. Zarkadakis, George. 2015. In Our Own Image: Savior or Destroyer? The History and Future of Artificial Intelligence. New York: Pegasus. Zielinski, Siegfried, and Peter Weibel, eds. 2015. Allah’s Automata: Artifacts of the Arab-Islamic Renaissance (800–1200). Karlsruhe: ZKM. Zimmer, Carl. 2016. “What’s the Longest a Person Can Live?” New York Times, October 5. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/06/science/maximum-life-span-study.html?_r=0. INDEX ILLUSTRATIONS ARE INDICATED BY PAGE NUMBERS IN ITALIC TYPE. Aberdeen Painter, cup with Triptolemus, 148 Achilles, 47, 50–51, 53, 54, 57, 130–31 Acragas, 85, 182, 184, 186 Adam, 2, 22, 23, 112, 157 Aeetes, King, 9, 65 Aelian, 57 Aeschylus: Daedalus’s statues as subject in tragedy by, 103; Glaukos (two distinct individuals) as subject of tragedies by, 48; Nurses of Dionysus, 34; Prometheus trilogy, 105; Sisyphus as subject of tragedy by, 53; Theoroi, 103 Aeson, 33–36, 43, 53 Aesop, 81, 244n39 agalmatophilia (statue lust), 107–10 Agathocles, 86, 184 aging, 53–58.

Pathfinders: The Golden Age of Arabic Science

by

Jim Al-Khalili

Published 28 Sep 2010

But as we shall see shortly, it was six hundred years before the word alchimia became ‘alchemy’ and came to have its modern meaning of transmutation. A number of historians have until recently been lazy in pinpointing the origin of this distinction. Their mistake has been to push the notion that there was a clear and well-understood difference between alchemy and chemistry all the way back to the Islamic golden age. However, even after Europeans began using two different words, ‘chemistry’ and ‘alchemy’, they still did not distinguish between the two. A practitioner was referred to either as a ‘chemist’ or an ‘alchemist’ (the prefix ‘al’ being the only difference, even in modern English, between the two words).

…

What benefit then is more vivid? What use is more abundant? Al-Bīrūni In a famous correspondence around the year 1000 CE, two Persian geniuses argued about the nature of reality in a way that would not sound out of place in any modern university physics department. Of all the great thinkers and polymaths of the Islamic golden age, these two men were giants, for they were in every way the equals of the very best that the golden age of Greece had produced. The younger of the two had been a privileged child prodigy who grew up to become the brash superstar of his age, a celebrity polymath whose philosophy would influence the world’s greatest minds, and whose Canon of Medicine (al-Qānūn fi al-Tibb) would become the world’s most important medical textbook for over half a millennium.

…

We encountered him earlier as the ruler for whom the great Andalusian geographer al-Idrīsi wrote his famous Book of Roger. But to what extent did Europe really remain in the shadow of the Islamic Empire? It would be wrong to dismiss completely any form of original scientific scholarship in Europe during the Islamic golden age, for there are always isolated pockets of intellectual activity and excellence wherever and whenever one looks in world history. Two notable lights and original thinkers who shone in the medieval darkness were the Italian Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225–74), and the Englishman William of Occam (c. 1288–1347).

Nuts and Bolts: Seven Small Inventions That Changed the World (In a Big Way)

by

Roma Agrawal

Published 2 Mar 2023

When you go to your optician and they test different lenses while asking you to read out letters of diminishing size, what they’re doing is How a magnifying glass creates an image for our eyes trying to find the lens that, based on the unique shape of your eye, will bend the light so it focuses on the back of your eye, the retina. The behaviour of light in a lens depends on the angle at which the light enters the material, and the characteristics of the material itself. One of Ibn al-Haytham’s predecessors in the Islamic Golden Age of science, Abu Sa’d al-Alaa Ibn Sahl, wrote a book in around 984 CE called On the Burning Instruments, about how to use mirrors and lenses to focus the Sun’s rays and create heat. Although the phenomenon had been observed by Aristophanes and Pliny the Elder, this was the first serious mathematical study of using lenses in this way.

…

Ibn Sahl’s work, however, only came to light in the 1990s, when Egyptian historian Roshdi Rashed pieced together his manuscript, part of which was found in Damascus, and part of which was found in Tehran. The science of optics advanced significantly in the Islamic empires, but the practical applications of lenses remained largely limited to burning glasses and simple magnification. Centuries later, when the Islamic Golden Age of science began to dim in the Middle East, and as light began to break through the Dark Ages in the West, Europe’s Renaissance thinkers built on the work of their medieval counterparts to truly harness the superpower of the lens. The mention of microscopy in that era conjures up images of wigged men peering into gilded tubes mounted on adjustable arms, or shiny brass instruments with narrow cylinders, intricate screws, and thin plates affixed to solid bases.

Lift: Fitness Culture, From Naked Greeks and Acrobats to Jazzercise and Ninja Warriors

by

Daniel Kunitz

Published 4 Jul 2016

And for a thousand years, until into the Renaissance, conditions of abundance and ease hardly existed in Europe, while elsewhere it was cultural norms and religious beliefs that relegated fitness to a martial context. Conceptions of exercise did not advance beyond what Galen had adduced and, like other classical learning, much of it was lost, forgotten, or ignored in the pre-Renaissance period. An exception can be found in some of the caliphates of the Islamic Golden Age. The thinker Ibn Sina (aka Avicenna; 980–1037 CE), for instance, who wrote in Persia, saw exercise as therapeutic and medicinal, recommending mild—fishing, sailing, and other mostly passive activities—and brisk exercise, such as “interchanging places with a partner as swiftly as possible” as in a dance or game, for most people, including the aged.

…

Jane (film), 39 gladiatorial contests, 51 Glassman, Greg, 15, 17, 66, 260–62, 263–65, 266, 267, 268, 269–70, 272 globo gyms, 260–61, 271 glycolytic system, 264 Godwin, William, 116 Goldberg, Jessie, 181 Golden Dragon Thrusting Out Its Claws, 74 Gold, Joe, 174, 183 Goldfarb, Harry, 162 Goodrich, Bert, 167 Gorgo, 43 Goruck, 69 Gosh, Bishnu Chandra, 191–92 Gotaas, Thor, 248–49 Grant, Cary, 183 Great Britain, 77, 98–99, 109–10 Great Competition, 162 Great Depression, 209 Greece, 20, 22, 27–45, 51, 76, 84, 251–52, 269 ambition in, 41–42 citizenship in, 42 exercise habits in, 33 funerary games in, 49 ideal of physical excellence in, 56 pain after exercise in, 38–39 and purpose of exercise, 39–40 Romantic admiration for, 93 slaves in, 42 women in, 42–43 Greif, Mark, 18–19 Grimek, John, 131, 165, 243 Grinder, 66, 81 Grund, Francis J., 121–22 Guerrero, Roberto, 259 guilt, 255–56 Gulick, Luther, 145, 159–60 Guts Muths, Johann Friedrich, 92, 94 Gymastics for Youth, or a Practical Guide to Healthful and Amusing Exercises for the Use of Schools (Guts Muth), 92 Gymnase Normal, Militaire et Civil, 98 gymnasia, 113 gymnasion, 32–33, 35, 38, 41, 42, 43–44, 61, 62, 200–201, 251 gymnastic rings, 267 gymnastics, 19, 92–104, 118, 119, 121, 192, 206 German, 92–95, 96–97, 99, 100, 103, 120 for women, 99, 102 “Gymnastics” (Higginson), 126, 138 gyms, 10–13 bad reputation of, 167 development of, 161–62 of Triat’s, 111–15, 116 habits, 7–8 Hall, Ran, 185 halteres, 34 Hamilton, Linda, 273 handstand push-ups, 272 Han Dynasty, 49, 60 Hargitay, Mickey, 183–84 Harlem, NY, 89–90 Harris, Waldo, 228 Harrison, James, 126 Harvard University, 97–98 Hasenheide, 97 hatha, 78–79, 190–91 Health and Tennis Corporation of America, 237 Health-Lift Company, 128, 142 Healthy Life, The: How Diet and Exercise Affect Your Heart and Vigor (Cureton), 224–25 heart disease, 210, 214–15 Hébert, Georges, 193–95 Hell Week, 79 Helvenston, Scott, 80 Herakles, 30 Hercules, see Farnese Hercules Higginson, Thomas Wentworth, 126 high-intensity workouts, 16 high jumping, 49 Highland Games, 278–79 Hinduism, 63, 84 Hippocrates, 48 Hirschland, Richard S., 208 Hittleman, Richard, 191 hockey, 119, 257 Hoffman, Bob, 164, 175, 185, 205, 242 Holiday Universal, 237 Hollywood Stuntwomen’s Association, 183 Holmes, Oliver Wendell, Sr., 116 Holyfield, Evander, 259 Holy Roman Empire, 92 Home (TV show), 217 homosexuality, in Greece, 44 horizontal bar, 94, 96 hormesis, 47–48 horse (gym equipment), 114 hot yoga, 191–92 How to Get Strong and How to Stay So (Blaikie), 138–39 How to Keep Fit Without Exercise (Steincrohn), 204 Hua Tuo, 50, 60 Hungarian Revolution, 217 Hungry Tiger Seizing a Lamb, 74 Hurt, William, 8 Hygienic Institute and School of Physical Culture, 139 Ibn Sina, 70, 76 Iliad (Homer), 49 Illustrated London News, 126 India, 76–77, 84 Indian Club Exercise, The (Kehoe), 126 Indian clubs, 109, 110–11, 114, 119 Indus River civilization, 48–49 infantry, 76 injuries, 189 Institute for Physical Culture, 154 Institute for Physical Fitness, 212, 215 intellectual gymnastics, 99 International Federation of Bodybuilders (IFBB), 166 interval training, 259, 260, 266 Iraq, 80 Ireland, 49 Iron Game, 164–65 Ironman Triathlon, 249, 263 iron wands, 114 Islamic Golden Age, 70 isonomia, 41 Italy, 98 Iyengar, B. K. S., 190–91 Jack LaLanne Show, The, 219–20 Jaeger, Werner, 27, 31, 40–41 Jahn, Friedrich Ludwig, 92–94, 96–97, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 178, 206 James, William, 141 Japan, 73 Jason, 61 javelin throwing, 49, 70 Jazzercize, 66, 235, 236 Jena-Auerstedt, Battle of, 92 Jennings, Peter, 6 Jivamukti, 191 Jocher, Beverly, 174 jogging, 8, 226–27, 229, 239, 249, 254 Jogging: A Physical Fitness Program for All Ages (Bowerman and Harris), 228 Johnson, James, 110 Jois, K.

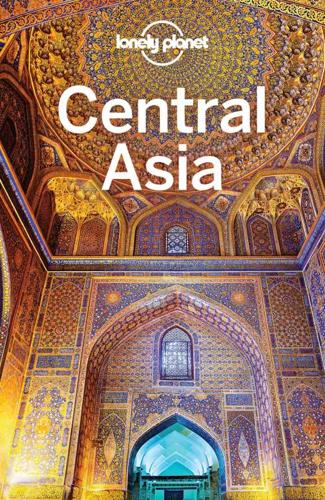

Lonely Planet Central Asia (Travel Guide)

by

Lonely Planet

,

Stephen Lioy

,

Anna Kaminski

,

Bradley Mayhew

and

Jenny Walker

Published 1 Jun 2018

Some industrialisation of Tajikistan was undertaken following WWII, but the republic remained heavily reliant on imports from the rest of the Soviet Union for food and standard commodities, as become painfully apparent after the 1991 collapse of the Soviet trading system. In the mid-1970s, an underground Islamic Renaissance Party started gathering popular support, especially in the south around Kurgan-Tyube (Kurgonteppa). This region had been neglected by Dushanbe’s ruling communist elite, who were mainly drawn from the prosperous northern city of Leninabad (now Khojand). Two 1979 events sent serious ripples through Tajik society.

…

In December 1991, Uzbekistan held its first direct presidential elections, which Karimov won with 86% of the vote. His only rival was a poet named Muhammad Solih, running for the small, figurehead opposition party Erk (Will or Freedom), who got 12% and was soon driven into exile (where he remains to this day). The real opposition groups, Birlik and the Islamic Renaissance Party (IRP), and all other parties with a religious platform, had been forbidden to take part. A new constitution unveiled in 1992 declared Uzbekistan ‘a secular, democratic presidential republic’. Under Karimov, Uzbekistan would remain secular almost to a fault. But it would remain far from democratic.

The Book: A Cover-To-Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of Our Time

by

Keith Houston

Published 21 Aug 2016

Adam Lucas, Wind, Water, Work: Ancient and Medieval Milling Technology (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 61–68; Bloom, Paper Before Print, 50–56; Karen Garlick, “A Brief Review of the History of Sizing and Resizing Practices,” in The Book & Paper Group Annual, vol. 5 (American Institute for Conservation, 1986), 94–107. 23. Garlick, “A Brief Review.” 24. J. L. Berggren, Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam (New York: Springer, 2003), 6–9, 31–32; Jonathan M. Bloom, “Paper: The Islamic Golden Age,” Essay, BBC, November 28, 2013, http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b03j9nhy. 25. Bloom, “Paper: The Islamic Golden Age.” 26. “Reconquista,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed December 17, 2013, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/493710/Reconquista; Catherine Delano Smith, “The Visigothic Kingdom,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed March 20, 2013, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/557573/Spain/70358/The-Visigothic-kingdom. 27.

Open: The Story of Human Progress

by

Johan Norberg

Published 14 Sep 2020

In the thirteenth century, the Muslim world found itself squeezed by Christian Crusaders from the north, and Mongol invaders from the east. In just half a century, more than half of their dominions were lost. Cordoba, the centre of learning in Islamic Spain, fell in 1236 as the Christian Reconquista gathered pace, and in 1248 the economic metropolis of Seville also fell. Much worse was to come. It has been said that the Islamic Golden Age ended on 13 February 1258, one of the bloodiest days in human history. After a twelve-day siege, a Mongol army breached the walls of Baghdad, the intellectual capital of the Muslim world. Mongol troops entered the city, massacred the population of men, women and children, and destroyed mosques, hospitals, schools and all thirty-six libraries.

…

It was a new explosive force, constantly and fearfully expanding with the passage of time. In those years of apparent illumination there was at least one-quarter of the sky in which darkness was positively gaining at the expense of light.3 The Ming dynasty turned its back on innovation and globalization; the Islamic Golden Age was quashed; the Ottomans, Persians, Mughals and Spanish ruined their empires by demolishing their foundations of openness. Europe was taken over by national socialists and communists, and tried to destroy itself twice in the twentieth century (or three times, counting the Cold War). At times, we go crazy and slit throats with industrial efficiency.

The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World

by

David Deutsch

Published 30 Jun 2011

He foresaw the invention of microscopes, telescopes, self-powered vehicles and flying machines – and that mathematics would be a key to future scientific discoveries. He was thus an optimist. But he was not part of any tradition of criticism, and so his optimism died with him. Bacon studied the works of ancient Greek scientists and of scholars of the ‘Islamic Golden Age’ – such as Alhazen (965–1039), who made several original discoveries in physics and mathematics. During the Islamic Golden Age (between approximately the eighth and thirteenth centuries), there was a strong tradition of scholarship that valued and drew upon the science and philosophy of European antiquity. Whether there was also a tradition of criticism in science and philosophy is currently controversial among historians.

The City: A Global History

by

Joel Kotkin

Published 1 Jan 2005

The future success of such a cosmopolitan model, amid the assault from intolerant brands of Islam, could do much to preserve urban progress around the world in the new century.60 Indeed, in an age of intense globalization, cities must manage to meld their moral orders with an ability to accommodate differing populations. In a successful city, even those who embrace other faiths, like dhimmis during the Islamic golden ages, must expect basic justice from authorities. Without such prospects, commerce inevitably declines, the pace of cultural and technological development slows, and cities devolve from dynamic places of human interaction into static, and ultimately doomed, congregations of future ruins. Cities can thrive only by occupying a sacred place that both orders and inspires the complex natures of gathered masses of people.

Life at the Speed of Light: From the Double Helix to the Dawn of Digital Life

by

J. Craig Venter

Published 16 Oct 2013

That same decade, British TV audiences were introduced to Doctor Who and his TARDIS (time and relative dimension in space), a blue London police box that could transport its occupants to any point in time and any place in the universe. The idea of teleportation did not originate with Star Trek or Doctor Who but has been in one form or other a part of literature for centuries. In One Thousand and One Nights (often known as The Arabian Nights), a collection of stories and folk tales compiled during the Islamic Golden Age and published in English in 1706, genies (djinns) can transport themselves and objects from place to place instantaneously. Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Disintegration Machine,” published in 1929, describes a machine that can atomize and reform objects. Teleportation has been explored by many fantasy and science-fiction writers, including Isaac Asimov (“It’s Such a Beautiful Day”),3 George Langelaan (“The Fly”), J.

About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks

by

David Rooney

Published 16 Aug 2021

IN THE WEST, the Mongol ruler Hulagu Khan may not be as well known as the empire’s founder, his grandfather Genghis, or his brother Kublai, immortalized in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s famed poem written in 1797. But in the Middle East the memory of Hulagu’s atrocities still looms large. In 1258, he led the sacking and destruction of Baghdad, a massacre that many see as ending what is known as the Islamic golden age, and his forces went on to invade and seize Syria. In 2002, in the run-up to the Iraq War, the al-Qaeda leader, Osama Bin Laden, broadcast a statement claiming that the US leadership had “killed and destroyed in Baghdad more than Hulegu of the Mongols.”5 But developments in his family’s internecine succession war after the siege of Baghdad saw Hulagu Khan’s power under threat, and he found himself needing to show the world—and his peers—that he was a ruler to be reckoned with.

The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization

by

Richard Baldwin

Published 14 Nov 2016

See also spillovers Innovation and Growth in the Global Economy (Grossman and Helpman), 193 International Monetary Fund (IMF), 99 Internet, 83–84, 84f, 130. See also ICT (information and communication technology) In the Wake of the Plague (Cantor), 35 intra-industry trade (IIT), 96, 97 Investor State Dispute Settlement provisions, 103 Iron Age, 27, 28f–29f, 29, 31 Irwin, Doug, 119 Islam, Golden Age of, 33, 34, 37f Islamic World, 35, 38, 43. See also Silk Road IT (information technology), 79; future and, 287–288, 291; polarization of jobs and, 294–295 Italy, 29, 43, 180–182, 208. See also Europe; G7 Italy/Greece. See also A7 ITC (information and communication technology): speed and, 12 IT (information technology) .

The Fourth Age: Smart Robots, Conscious Computers, and the Future of Humanity

by

Byron Reese

Published 23 Apr 2018

Rome epitomized civilization with its law code and efficient government. Pax Romana brought prosperity and stability to millions. And during this time, the Romans laid roads and built harbors so technologically advanced that they are still used today. Fast-forward seven hundred years to the Islamic Golden Age, when an attempt was made to gather all written knowledge from all cultures around the world and translate it into Arabic. And while the Islamic peoples of Northern Africa and the Near and Middle East were doing that, they made monumental advances in algebra, geometry, trigonometry, and even hints of calculus, which would not be formalized elsewhere for almost a thousand years.

The Knowledge Machine: How Irrationality Created Modern Science

by

Michael Strevens

Published 12 Oct 2020

It seemed wrong, even nonsensical, but he overrode his qualms, surrendering to the scientific method. Take the roots of Whewell’s quandary and project them back over the thousand years of history that preceded the development of modern science. Throughout the European Middle Ages and the roughly coterminous Islamic Golden Age, you find thinkers exploring the workings of the natural world by way of astronomy, optics, medicine, and more. None of these thinkers hit upon anything like the iron rule. They could not have. They were all, each in their own way, devout. It was clear to them that knowledge of God or of God’s plan potentially had something to tell us about the way things were laid out in the physical world—in histories, living bodies, the system of planets.

The Wine-Dark Sea Within: A Turbulent History of Blood

by

Dhun Sethna

Published 6 Jun 2022

Commentary and quotations by Max Meyerhof, “Ibn an-Nafis (XIIIth cent.) and His Theory of the Lesser Circulation,” Isis 23 (1935): 100–120, reproduced in Mark Graubard, Circulation and Respiration, 59. 5. Haddad and Khairallah, “A Forgotten Chapter,” 1–8; Meyerhof, “Ibn an-Nafis,” 100–120, in Graubard, Circulation and Respiration, 59. 6. E. G. Browne, Arabian Medicine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1921). 7. J. B. West, “Ibn al-Nafis, the Pulmonary Circulation, and the Islamic Golden Age,” Journal of Applied Physiology 105 (2008): 1877–1880. 18. WHO’S ON FIRST? 1. L. G. Wilson, “The Problem of the Discovery of the Pulmonary Circulation,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 17 (1962): 229–244; Owsei Temkin, “Notes and Comments: Was Servetus Influenced by Ibn an-Nafis?”

The Heat Will Kill You First: Life and Death on a Scorched Planet

by

Jeff Goodell

Published 10 Jul 2023

A few Greek philosophers, including Plato, rightly suspected there was a link between heat and motion, but didn’t take it any further than that: “heat and fire… are themselves begotten by impact and friction: but this is motion. Are not these the origins of fire?” Fifteen hundred years later, during the Islamic Golden Age in the tenth and eleventh centuries, a pair of thinkers proposed that heat was related to light—which was a big step in the right direction. Al-Bīrunī, a mathematician and scholar who served the Sultan Mahmūd of the Ghazna Kingdom (now Afghanistan), was the first to divide hours into minutes and seconds.

Infinite Powers: How Calculus Reveals the Secrets of the Universe

by

Steven Strogatz

Published 31 Mar 2019

Through what must have been heroic feats of arithmetic, he tightened the vise on pi to eight digits: 3.1415926 < π < 3.1415927. The next step forward took another five centuries and came from the sage Al-Hasan Ibn al-Haytham, known to Europeans as Alhazen. Born in Basra, Iraq, around 965 CE, he worked in Cairo during the Islamic golden age on everything from theology and philosophy to astronomy and medicine. In his work on geometry, Ibn al-Haytham calculated volumes of solids that Archimedes never considered. Still, impressive as these advances were, they were rare signs of life for geometry, and they took twelve centuries to occur.

Why Machines Learn: The Elegant Math Behind Modern AI

by

Anil Ananthaswamy

Published 15 Jul 2024

It’s simple to figure out that building’s post office branch: Find the building’s Voronoi cell and assign that building to the cell’s seed, or post office branch. The problem we’ve just analyzed is more generally cast as the search for nearest neighbors. Software implementations of such searches rank among the most influential algorithms in machine learning. We’ll soon see why. But first, we must go back in time to the Islamic Golden Age and the work of Abu Ali al-Hasan Ibn al-Haytham, or Alhazen, a Muslim Arab mathematician, astronomer, and physicist. It was Alhazen who, in his attempt to explain visual perception, came up with a technique that closely mirrors modern nearest neighbor search algorithms. Marcello Pelillo, a computer scientist at the University of Venice, Italy, has been doing his best to draw attention to Alhazen’s ideas.

The Most Powerful Idea in the World: A Story of Steam, Industry, and Invention

by

William Rosen

Published 31 May 2010

It is the modern world, however, that is historically anomalous. Hundreds of different cultures had experienced bursts of inventiveness and economic growth before the eighteenth century—bursts they were unable to sustain for more than a century or so. Imagine, for example, how different the last eight hundred years might have been had the Islamic Golden Age—whose inventors were responsible for everything from crankshaft-driven windmills and water turbines to the world’s most advanced mechanical clocks—survived the thirteenth century. Instead, like all the world’s earlier explosions of invention, it, in the words of one of the phenomenon’s most acute observers, “fizzled out.”8 One unique characteristic of the eighteenth-century miracle was that it was the first that didn’t.

Nomads: The Wanderers Who Shaped Our World

by

Anthony Sattin

Published 25 May 2022

By ‘enemies’ the ambassador meant foreigners, many of them nomads, but it was they who helped the empire to thrive as people, goods, knowledge and ideas, beliefs, stories, songs, styles of representation and all the myriad other aspects of culture were carried through mountain ranges and deserts, along valleys and steppes, across seas and oceans. In this milieu, Arab civilisation flourished. Harun knew that the vast wealth and glittering inspiration of the Islamic golden age came not from the safety offered by walls and borders, but by people being in motion and allowed to move freely across an empire that stretched from al-Andalus to Central Asia. Abbasid influence could now be felt south of the Sahara, down into India, up into Siberia, west to the Byzantine border and east into China.

Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East

by

Scott Anderson

Published 5 Aug 2013

A devout Muslim who embraced the jihadist credo of pan-Islam, Djemal had also been one of the most vocal Young Turk leaders in advocating that the empire’s ethnic and religious minorities be given full civil rights. An aesthete who loved European music and literature, and who enjoyed nothing more than practicing his French in the expatriate salons of Constantinople, he also exhorted his countrymen to purge their nation of corrupting Western influence. Dreaming of a Turkish and Islamic renaissance that would return the Ottoman Empire to its ancient splendor, he was at heart a technocrat, intent on pulling his nation into modernity through the building of roads and railways and schools. “He had the ambition of creating a Syria which he could exhibit with pride to an admiring Europe,” Bliss wrote.

The 9/11 Wars

by

Jason Burke

Published 1 Sep 2011

Ibn Tammiya, a key Salafi scholar and a major influence on modern ideologues including bin Laden and others among the al-Qaeda leadership, was writing in the thirteenth century after the fall of Baghdad to the Mongols, an event he blamed on the corruption and lassitude of the ruling Muslim dynasty and their subjects. In the nineteenth century, as Muslim societies and states came off worst in their one-sided battle with an expansionist West, new thinkers resurrected the idea of an Islamic renaissance based on a return to basics. With Salafis divided over how best to respond to the challenge posed by the technological, military and apparent cultural superiority of the invaders, various strands of thought emerged. Some called for a total rejection of all Western innovation and a harsh puritanism, others for its appropriation, a position which evolved towards the political ideology of Islamism, which calls for the appropriation of the modern state apparatus rather than its replacement by a model based on that believed to have been current in seventh-century Arabia and inevitably implies the formation of parties rather than a rigorous adherence to an individual relationship with God.

How to Invent Everything: A Survival Guide for the Stranded Time Traveler

by

Ryan North

Published 17 Sep 2018

Oxford University Press. Gainsford, Peter. 2017 CE. “Salt and Salary: Were Roman Soldiers Paid in Salt?” Kiwi Hellenist: Modern Myths About the Ancient World. January 11. http://kiwihellenist.blogspot.ca/2017/01/salt-and-salary.html. Gearon, Eamonn. 2017 CE. “The History and Achievements of the Islamic Golden Age.” The Great Courses. Gerke, Randy. 2009 CE. Outdoor Survival Guide. Human Kinetics. Glenn, Edward P., J. Jed Brown, and Eduardo Blumwald. 1999 CE. “Salt Tolerance and Crop Potential of Halophytes.” Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 18 (2): 227–55. doi:10.1080/07352689991309207. Goldstone, Lawrence. 2015 CE.

Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2011

by

Steve Coll

Published 23 Feb 2004

Zia felt this was only Pakistan’s due: “We have earned the right to have [in Kabul] a power which is very friendly toward us. We have taken risks as a frontline state, and we will not permit a return to the prewar situation, marked by a large Indian and Soviet influence and Afghan claims on our own territory. The new power will be really Islamic, a part of the Islamic renaissance which, you will see, will someday extend itself to the Soviet Muslims.”8 In Washington that winter, much more than the liberals it was the still-vigorous network of conservative anticommunist ideologues in the Reagan administration and on Capitol Hill who began to challenge the CIA-ISI combine.

Dirty Wars: The World Is a Battlefield

by

Jeremy Scahill

Published 22 Apr 2013

Khan eventually found a home at Muslimpad, run by Islamic Network (one time employer of Daniel Maldonado, who was convicted for traveling to ICU training camps in Somalia). One of his blogs, also called Inshallahshaheed, was started in 2005 and had become wildly popular by 2007, ranking among the top 1 percent of 100 million websites in the world by the traffic counter Alexa.com. His other blogs went by names such as Human Liberation–An Islamic Renaissance and Revival. On his blogs, Khan would extol the victories and virtues of al Qaeda central and its affiliated militants, but his writings also helped to popularize a broader ideological movement that included radical sheikhs and scholars many Americans would not have known about. A later blog featured in its “About” section a list of men he described as “scholars of Islam...who we take knowledge from,” and included Abu Musab al Zarqawi, Abu Layth Libi, and Anwar Awlaki.

Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can't Explain the Modern World

by

Deirdre N. McCloskey

Published 15 Nov 2011

The Greeks and Romans had written novels about mundane matters, such as dinner parties, but the genre died out along with Rome’s grandeur and corruption. The Japanese from the twelfth century had modern-seeming novels, written famously by women, though focusing on courtly life. And at about the same time, during the Islamic Golden Age, the novel was a common genre, if similarly focused on the court. The Chinese—hundreds of years before the Europeans caught on, as usual—had been gathering folktales and official histories into proper novels, such as the Romance of the Three Kingdoms (early Ming dynasty), though these also focused mainly on the great and good and their exploits.

Spain

by

Lonely Planet Publications

and

Damien Simonis

Published 14 May 1997

The local offshoot of the Europe-wide phenomenon of art nouveau, Modernisme was characterised by its taste for sinuous, flowing lines and (for the time) adventurous combinations of materials like tile, glass, brick, iron and steel. But Barcelona’s Modernistas were also inspired by an astonishing variety of other styles too: Gothic and Islamic, Renaissance and Romanesque, Byzantine and baroque. Gaudí and co were trying to create a specifically Catalan architecture, often looking back to Catalonia’s medieval golden age for inspiration. It is no coincidence that Gaudí and the two other leading Modernista architects, Lluís Domènech i Montaner (1850–1923) and Josep Puig i Cadafalch (1867–1957), were prominent Catalan nationalists.

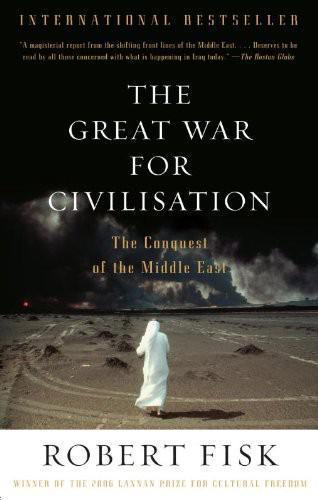

The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East

by

Robert Fisk

Published 2 Jan 2005

But despite this, oil is not the direct impetus for the Americans occupying the region—they obtained oil at attractive prices before their invasion. There are other reasons, primarily the American–Zionist alliance, which is filled with fear at the power of Islam and of the land of Mecca and Medina. It fears that an Islamic renaissance will drown Israel. We are convinced that we shall kill the Jews in Palestine. We are convinced that with Allah’s help, we shall triumph against the American forces. It’s only a matter of numbers and time. For them to claim that they are protecting Arabia from Iraq is untrue—the whole issue of Saddam is a trick.”