Dealers of Lightning

by

Michael A. Hiltzik

Published 27 Apr 2000

Systems to reorganize the computer’s memory and processing cycles so it might serve many users simultaneously—which was known as time-sharing—brought the per-session cost of building and running these enormous contraptions down to a level that even midsized and small universities could afford. Lick’s successor seemed the perfect man to manage this expanding program. Ivan Sutherland was a brilliant MIT graduate who happened to be serving with the Army as a first lieutenant. Only twenty-six, he had already amassed an enviable research record, the crowning achievement of which had been the development of the first interactive computer graphics program. Known as Sketchpad, the system allowed a user to draw highly detailed and complex drawings directly on a computer’s cathode-ray screen using a light pen and store them in memory.

…

They could not have known that within a few short years Bob Taylor would outshine them both in his influence over computer research in the United States. The humble job of serving as deputy to a first lieutenant with a Pentagon staff appointment was about to set Bob Taylor on the path to his, and the computer’s, destiny. Ivan Sutherland spent scarcely eighteen months at IPTO. Late in 1965 Harvard offered him a tenured position. He was officially gone by June 1966 but unofficially much earlier. By January or February that year Taylor was already running IPTO all by himself. The apprenticeship had been short, but edifying enough.

…

Thus was computing rendered more remote and intimidating than ever—a backwards trend exemplified in Clark’s view by the archetypal system at MIT: “That of a very large International Business Machine in a tightly sealed Computation Center: The computer not as tool, but as demigod.” What Clark found even more troubling was that subdividing the main processor, as time-sharing did, rendered impossible the sort of display-based research that Ivan Sutherland had achieved so spectacularly on the TX-2. No user of a time-shared computer could ever monopolize the processor long enough to drive a coherent visual display as Sutherland had. (Clark allowed the TX-2 to be shared, but only serially—you signed up for a block of time on it, but during that period the entire machine was yours.)

Bootstrapping: Douglas Engelbart, Coevolution, and the Origins of Personal Computing (Writing Science)

by

Thierry Bardini

Published 1 Dec 2000

At the beginning of his tenure at the IPTO, Licklider formed an advisory committee composed of the representatives of the main funding institutions in- volved in computing at that time. One member was another young psycholo- gist, Robert Taylor, who was then heading a research program on computing at NASA.16 In 1964, Licklider resigned from ARPA in order to return to MIT and was replaced as director of the IPTO by Ivan Sutherland, at that time a 26- year-old army lieutenant at Fort Meade, Maryland. Taylor served as Suther- land's associate director until 1965, when Sutherland accepted a faculty posi- tion at Harvard. Thus, Taylor became the third director of the IPTO. 22 IntroductIon Over the next five years, the IPTO funded twenty or so large research proj- ects, mostly at u.s. universities. 17 Particularly heavy funding went to the computer science departments at MIT, Carnegie-Mellon University, and Stan- ford University, three departments still top-rated in computer science today.

…

What saved my program from extinction was the arrival of an out-of-the-blue support offer from Bob Taylor, who at that time was a psychologist working at NASA headquarters. 23 Thanks to Robert Taylor, NASA support started from midyear 1964 to mid- year 1965 at a level of about eighty-five thousand dollars. Taylor's support became even more important when he became Ivan Sutherland's second in 24 Introduction command at the IPTO in July 1964, and then when he took the direction of the IPTO, in June 1966. Engelbart's approach differed from Licklider's both essentially and prag- matically, despite the apparent agreement on the need do some kind of human- computer symbiosis.

…

In this second subnetwork, the IPTO's three main research areas were in- vestigated by prestigious scientists such as John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Wesley Clark, Edward Fredkin, and younger members such as Ivan Suther- land. MIT also had operated an early time-sharing system since Decem- ber 1958,30 and Ivan Sutherland developed Sketchpad, the first graphics soft- ware, on the TX-2 computer. The research on artificial intelligence certainly gave strength to the East Coast subnetwork. Apart from the MIT-centered Boston community, it also included the Carnegie-Mellon University group led by Herbert Simon and Allen Newell (joined by Alan Perlis) after they had left RAND in the early 1960'S.3I Almost everybody in this community agreed on the necessity of time shar- ing as a preliminary step toward interactive computing.

The Dream Machine: J.C.R. Licklider and the Revolution That Made Computing Personal

by

M. Mitchell Waldrop

Published 14 Apr 2001

Indeed, that question was much on Taylor's mind in June 1966, when Suther- land ended his tour at ARPA-he had accepted an offer from Harvard-and Tay- lor was named to succeed him, as the third director of the Information Processing Techniques Office. Now, Taylor knew full well that he didn't command the kind of automatic re- spect from the ARPA community that Sutherland had commanded. In their THE INTERGALACTIC NETWORK 263 eyes, Ivan Sutherland had been a technological genius-just the kind of man the agency needed in that position. But Taylor was, well, a psychologist. With no Ph.D. "Can you imagine going from J. C. R. Licklider to Ivan Sutherland to . . . Bob Taylor?" asks one PI, remembering his reaction at the time. No one said anything overt, of course, since Taylor did control the money- for the time being. No, they just conveyed an ineffable air of condescension, an unmistakable message that the community considered him to be a mere admin- istrator, a caretaker who was keeping the chair warm until a good technical per- son could be brought in.

…

"Some of the pro- fessional bureaucrats were dumbfounded. They had a history of giving grants to individual people in twenty-thousand-dollar chunks. But Lick was talking about millions of dollars and whole teams of people. It was as though these folks had encountered this alien creature: friendly, but strange." Another participant, Ivan Sutherland, remembers his first meeting in 1964: "These people met, period. The group had no charter, no responsibilities, no budget, no purpose-but it was a great thing. We would discuss what was important, what was current, and what was going on. Precisely because the group had no charter, it was a wonderful way of getting information flow between the agencies."

…

Fortunately, one of ARPA's traditions was that outgoing office directors were allowed to recruit their own successors; all Lick had to do was to come up with an experienced, senior person with good credentials, and everybody would be happy. So Lick, characteristically, nominated a totally inexperienced and very junior candidate whose credentials were about the most awkward and inconven- ient conceivable in the Pentagon. He was a skinny, intense fellow named Ivan Sutherland. He was twenty-six years old. And at the time he was a first lieu- tenant in the army. It wasn't that he hadn't tried to find someone more senior, Lick protested in his 1988 interview; it was just that the answers he'd gotten ranged from "No!" to "Hell, No!" "Most of my colleagues would much rather spend the government money doing research back in the lab than coast another year or two or three in Washington," he said.

Tools for Thought: The History and Future of Mind-Expanding Technology

by

Howard Rheingold

Published 14 May 2000

Claude Shannon was a bona fide prodigy, twenty-two years old when he published (in 1937) the famous MIT master's thesis that linked electrical circuitry to logical formalisms. He was the peer of pioneers like Turing, Wiener, and von Neumann, the teacher of the first generation of artificial intelligence explorers like John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky, and the mentor of Ivan Sutherland, who has been one of the most important contemporary infonaut-architects. When Shannon's papers establishing information theory were published in 1948, he was thirty-two. The impact on science of this man's career was incalculable for these two contributions alone, but he also wrote a pioneering article on the artificial intelligence question of game-playing machines, published in 1950.

…

He doesn't like to teach. He doesn't like giving lectures. His lectures are jewels, all of them. They sound spontaneous, but in reality they are very, very carefully prepared. In the early sixties, one of the extremely few students Shannon personally took on, another MIT bred prodigy by the name of Ivan Sutherland, made quite a splash on the computer science scene. By the mid-1970s, Shannon, now in his sixties, had become a literal gray eminence. By the early 1980s, he still hadn't stopped thinking about things, and considering his track record, it isn't too farfetched to speculate that his most significant discoveries have yet to be published.

…

Licklider remembers the first official meeting on interactive graphics, where the first wave of preliminary research was presented and discussed in order to plan the assault on the main problem of getting information from the innards of the new computers to the surface of various kinds of display screens. It was at this meeting, Licklider recalls, that Ivan Sutherland first took the stage in a spectacular way. "Sutherland was a graduate student at the time," Licklider remembers, "and he hadn't been invited to give a paper." But because of the graphics program he was creating for his Ph.D. thesis, because he was a prot�g� of Claude Shannon, and because of the rumors that he was just the kind of prodigy ARPA was seeking, he was invited to the meeting.

Dawn of the New Everything: Encounters With Reality and Virtual Reality

by

Jaron Lanier

Published 21 Nov 2017

Burrowing in the back reaches of the library recalled my explorations of the shelf of books and records at my little school in Juárez so long ago. I wondered if I might find a new treat on a par with The Garden of Earthly Delights. Prize It was camouflaged, hidden in the most boring possible academic journal. I had finally stumbled upon Ivan Sutherland’s amazing work. These days, I am sometimes called the father of VR. My usual retort is that it depends on whether you believe the mother of VR. VR was actually birthed by a long parade of scientists and entrepreneurs. Ivan had started up the whole field of computer graphics with his 1963 PhD thesis, which was called Sketchpad.

…

In cases like that, there is a discrete moment when an operator enters input data into the computer, such as an encrypted enemy message, and then runs the program, and then reads the output. Indeed, the formal definitions of computation from Turing and von Neumann were first expressed around this model of discrete input, processing, and output stages. But what if computers were running all the time, interacting with the world, embedded in the world? This is exactly what Ivan Sutherland had prototyped! “Cyber” comes from the Greek and is related to navigation. When you sail, you must constantly adjust to changes in wind and surf. In the same way, a computer would have sensors to measure the world and actuators to affect the world. A computer embedded in the world would be a little like a robotic sailor even if it was fixed in place.

…

My first job interview was actually all the way up in pretty Marin County, over the Golden Gate Bridge. George Lucas was starting an organization to create digital effects for movies but also for video and audio editing, with ambitions to get into video games. You might think I was interested because of Star Wars, but no, it was because a student of my hero Ivan Sutherland, a fellow named Ed Catmull, had started these digital efforts. I entered a big, unmarked industrial building and was greeted by a giant painting of the Organ Mountains, the pinnacles I stared at so often as a child in New Mexico. How could this be? Turned out that one of the other prime digital gurus at the place was Alvy Ray Smith, another migrant from our corner of the desert.

The Long History of the Future: Why Tomorrow's Technology Still Isn't Here

by

Nicole Kobie

Published 3 Jul 2024

And no wonder, as layering digital data onto reality in a lightweight form factor with all-day battery life is more complicated than producing a console-powered headset for playing games alone in your basement. And we’ve barely made VR headsets that work despite development stretching back to the 1960s, when Ivan Sutherland and his team of students built the first head-mounted display. * * * The first person to use what would eventually become known as an augmented reality headset didn’t want the darn thing on his head. And it’s no wonder he was concerned. As a student at Harvard in 1968, Quintin Foster was working under Ivan Sutherland, an academic already famous for his Sketchpad program that let the user draw as an input to a computer, a breakthrough that eventually led to graphical user interfaces, object-oriented programming and the field of human–computer interaction.

…

Raibert shows a picture from the era, of a young woman holding a robotic arm: ‘In 1974, 49 years ago, I fell in love twice: once with Nancy, and once with robotics. Now, a few years ago, Nancy dumped me. But I’m still in love with robotics.’ After finishing grad school in 1977, Raibert had the chance to discuss his work with Ivan Sutherland, whom we’ll meet in the next chapter as the creator of the first head-mounted display. Sutherland said he’d fund a robot. Which robot did Sutherland pick? A hopping machine. That led to the Leg Lab, Raibert’s own robotics project. The first creation was a planar one-leg hopper that could jump on the spot using a pneumatic system, bounce away at a set rate, avoid being knocked over when bumped and even leap over small obstacles, all using a simple control system.

…

When the CIA grant worth $80,000 was leaked to the Harvard ‘leftist rag’ the Old Mole, it sparked a minor scandal and a public debate about whether the military-industrial complex should be meddling with academia. Sutherland didn’t speak but did attend the debate, noting at the panel discussion: ‘It is evidence of the eloquence of the Harvard faculty or the naivety of Ivan Sutherland that my opinion changed eight times during the debate.’ With that minor controversy over and the project a success, Sutherland left his tenured position at Harvard to join an old friend and colleague, Dave Evans, at the University of Utah, where they ended up setting up their own business, Evans & Sutherland, making simulators for training pilots, which eventually evolved into a digital theatre company.6 But they didn’t build VR headsets.

Intertwingled: The Work and Influence of Ted Nelson (History of Computing)

by

Douglas R. Dechow

Published 2 Jul 2015

That setup would have cost over two million dollars back then, and it wouldn’t have had a screen. Nelson believes he saw a screen in a manual at one point – as he told me in an email a couple of weeks ago, “I remember it very clearly. A round CRT and a flat desk surface, a light pen” (Nelson 2014, pers. comm.). This was apparently not Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad, which was built in 1963, and Nelson has been unable to find the image again in the IBM 7090 manual). In Possiplex, he writes:A few words, a few pictures of people at computer screens, and the understanding that computer prices would fall—these gave me all I needed to know, a crystal seed from which to conjure a whole universe [10, p. 100].

…

He writes in Literary Machines that in 1967 “the idea of communicating between such consoles was beginning to get through to me, and the nagging issue of shared access began to grow on me” [9, p. 1/31]. It may have been growing on Nelson in 1967, but as I’ve said, the computing world really wasn’t about to swallow the idea of a global hypertext publishing system. Work had not even started on the ARPANET (though Ivan Sutherland and Bob Taylor had been thinking about it for some time). The computing establishment was still trying to grapple with the concept of a person sitting in front of a screen and exploring information in real-time after Doug’s mother of all demos in 1968. That demo took years—over 20 years—to filter through properly.

…

An example that moved me as a boy was Wright’s legendary house, Fallingwater. In high school I was similarly moved by several electronic designs: heterodyning, the Theremin, and the Hammond Organ. In the computer field, I was greatly inspired by several different pieces of software and hardware: the APL computer programming language; the PDP-8 computer; Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad; Ken Knowlton’s L6 language; Nassi-Shneiderman diagrams; and Sinden’s film, Force, Mass and Motion. Their designers had all found simple constructs that generated all the results they wanted. This was a clear lesson for the design of software—finding the cleanest and most powerful constructs.

Machines of Loving Grace: The Quest for Common Ground Between Humans and Robots

by

John Markoff

Published 24 Aug 2015

He was already carrying his “interim” Dynabook around and happily showing it off: a wooden facsimile preceding laptops by more than a decade. Kay hated his time in McCarthy’s lab. He had a very different view of the role of computing, and his tenure at SAIL felt like working in the enemy’s camp. Alan Kay had first envisioned the idea of personal computing while he was a graduate student under Ivan Sutherland at the University of Utah. Kay had seen Engelbart speak when the SRI researcher toured the country giving demonstrations of NLS, the software environment that presaged the modern desktop PC windows-and-mouse environment. Kay was deeply influenced by Engelbart and NLS, and the latter’s emphasis on boosting the productivity of small groups of collaborators—be they scientists, researchers, engineers, or hackers.

…

Robots, and by extension their keepers, were definitely second-class citizens compared to the agency’s stars, the astronauts. JPL had hired the brand-new MIT Ph.D. as a junior engineer into a project that proved to be stultifyingly boring. Out of self-preservation, Raibert started following the work of Ivan Sutherland, who by 1977 was already a legend in computing. Sutherland’s 1962 MIT Ph.D. thesis project “Sketchpad” had been a major step forward in graphical and interactive computing, and he and Bob Sproull codeveloped the first virtual reality head-mounted display in 1968. Sutherland went to Caltech in 1974 as founding chair of the university’s new computer science department, where he was instrumental in working with physicist Carver Mead and electrical engineer Lynn Conway on a new model for designing and fabricating integrated circuits with hundreds of thousands of logic elements and memory—a 1980s advance that made possible the modern semiconductor industry.

…

In 1970, Xerox Corp. temporarily located its Palo Alto Research Center at South California Avenue and Hanover Street, where, shortly thereafter, a small group of researchers designed the Alto computer. Smalltalk, the Alto’s software, was created by another PARC group led by computer scientist Alan Kay, a student of Ivan Sutherland at Utah. Looking for a way to compete with IBM in the emerging market for office computing, Xerox had set out to build a world-class computer science lab from scratch in the Industrial Park. More than a decade ahead of its time, the Alto was the first modern personal computer with a windows-based graphical display that included fonts and graphics, making possible on-screen pages that corresponded precisely to final printed documents (ergo WYSIWYG, pronounced “whizziwig,” which stands for “what you see is what you get”).

Howard Rheingold

by

The Virtual Community Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier-Perseus Books (1993)

Published 26 Apr 2012

Licklider knew there was a whole subculture of unorthodox programming geniuses clustered at the new Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at MIT and graphics geniuses like Ivan Sutherland at Lincoln. There were others around the country, chafing to get their hands on the kind of computing resources that didn't exist in the punched card and mainframe era. They wanted to reinvent computing; the computer industry giants and the mainstream of computer science weren't interested in reinventing computing. So Licklider and his successors at ARPA, Robert Taylor and Ivan Sutherland (both in their twenties), started funding the young hackers--the original hackers, as chronicled in Steven Levy's book Hackers, not the ones who break into computer systems today.

…

"I guess you could say I had a religious conversion," he said. 26-04-2012 21:43 howard rheingold's | the virtual community 8 de 43 http://www.rheingold.com/vc/book/3.html Licklider became involved himself with computer display technology at Lincoln Laboratory, an MIT facility that did top-secret work for the Department of Defense. The new computers and displays that the North American Defense Command required in the early 1960s needed work on the design of information displays. Out of that work, one of Licklider's junior researchers, a graduate student named Ivan Sutherland, created the field of computer graphics. Through Lincoln Laboratory, Licklider met the people who later hired him at ARPA. In October 1957, when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the people who were responsible for maintaining the state of the art in U.S. military technology were shocked into action.

…

The earliest users of CMC systems also were the people who built the first CMC systems; as users as well as designers of this thinking tool, they were reluctant to build in features that took power away from individual users, so they designed a degree of user autonomy into the system that persists in the architecture of cyberspace today. At Lincoln Lab and the University of Utah, where Ivan Sutherland and a younger generation of crusaders such as Alan Kay ended up, interactive computer graphics was the quest. The jump from alphabetic printout to graphic screen display was a major leap in the evolution of the way computers are designed to be operated by people, the "human-computer interface."

What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry

by

John Markoff

Published 1 Jan 2005

Of all the issues facing the researchers who were trying to build a man-machine interface at the time—keyboards and commands and everything else—pointing at something on the screen was one of the most difficult. People had pointed at blips on a radar screen in the SAGE early-warning system using light guns, Ivan Sutherland had designed a remarkable graphics program that worked with a light pen, but a pointing device that would let the computer user easily specify where he wanted to do something on the screen had rarely been used with text before.14 When he returned to SRI, Engelbart gave English a copy of the sketch.

…

He didn’t worry about the remarkably high expense of the systems he was developing because he knew that by the time they were really mastered, prices would have plunged.19 However, in the boom and bust research world that relied on military and NASA contracting dollars, Engelbart’s research projects were invariably at risk, often at the mercy of visionary backers like Taylor and Licklider. The Augment experiment went through a shaky review with NASA in 1967, and the entire project was in danger of losing its funding until Bob Taylor came to Engelbart’s aid again. Taylor had replaced Ivan Sutherland as director of the ARPA Information Processing Technology Office in 1966 and soon discovered that Engelbart’s project was having financial problems. During this period, Engelbart was barnstorming the country with a film that showed some of the possibilities of editing on a computer screen instead of on paper-based typewriter terminals.

…

McCarthy had meanwhile become interested in some vexing issues in computer vision that would need to be solved if robots were to recognize and manipulate blocks successfully. In 1964, he had applied for a larger grant, which he received, and he even had the audacity to ask ARPA to allow him to hire an executive officer. By that time, Ivan Sutherland, the designer of the brilliant Sketchpad drawing system, had succeeded Licklider. He told McCarthy he thought the notion of an executive officer was a great idea. “You’re the only one of our investigators with a perfect record,” Sutherland said. “You have never turned in a quarterly progress report.”9 Sutherland had quickly realized that McCarthy had little interest in the management side of the SAIL project.

The Innovators: How a Group of Inventors, Hackers, Geniuses and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution

by

Walter Isaacson

Published 6 Oct 2014

“I learned all the various tricks for getting people to put up their quarters, and that sure served me well.”13 He was soon promoted to the pinball and game arcade, where animated driving games such as Speedway, made by Chicago Coin Machine Manufacturing Company, were the new rage. He was fortunate as well in landing at the University of Utah. It had the best computer graphics program in the country, run by professors Ivan Sutherland and David Evans, and became one of the first four nodes on the ARPANET, the precursor to the Internet. (Other students included Jim Clark, who founded Netscape; John Warnock, who cofounded Adobe; Ed Catmull, who cofounded Pixar; and Alan Kay, about whom more later.) The university had a PDP-1, complete with a Spacewar game, and Bushnell combined his love of the game with his understanding of the economics of arcades.

…

Although Taylor could be blustery and Licklider tended to be gentle, they both loved working with other people, befriending them, and nurturing their talents. This love of human interaction and appreciation for how it worked made them well suited to designing the interfaces between humans and machines. When Licklider stepped down from IPTO, his deputy, Ivan Sutherland, took over temporarily, and at Licklider’s urging Taylor moved over from NASA to become Sutherland’s deputy. Taylor was among the few who realized that information technology could be more exciting than the space program. After Sutherland resigned in 1966 to become a tenured professor at Harvard, Taylor was not everyone’s first choice to replace him, since he did not have a PhD and wasn’t a computer scientist, but he eventually got the job.

…

There he studied queuing theory, which looks at such questions as what an average wait time in a line might be depending on a variety of factors, and in his dissertation he formulated some of the underlying math that analyzed how messages would flow and bottlenecks arise in switched data networks. In addition to sharing an office with Roberts, Kleinrock was a classmate of Ivan Sutherland and went to lectures by Claude Shannon and Norbert Wiener. “It was a real hotbed of intellectual brilliance,” he recalled of MIT at the time.61 Late one night at the MIT computer lab, a tired Kleinrock was running one of the machines, a huge experimental computer known as the TX-2, and heard an unfamiliar “psssssss” sound.

Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins of the Internet

by

Katie Hafner

and

Matthew Lyon

Published 1 Jan 1996

But by the time he left in 1964, he had succeeded in shifting the agency’s emphasis in computing R&D from a command systems laboratory playing out war-game scenarios to advanced research in time-sharing systems, computer graphics, and improved computer languages. The name of the office, Command and Control Research, had changed to reflect that shift, becoming the Information Processing Techniques Office. Licklider chose his successor, a colleague named Ivan Sutherland, the world’s leading expert in computer graphics. In 1965 Sutherland hired a young hotshot named Bob Taylor, who would soon sit down in ARPA’s terminal room and wonder why, with so many computers, they were unable to communicate with one another. Taylor’s Idea Bob Taylor had started college in Dallas at the age of sixteen thinking he would follow his father’s footsteps and become a minister.

…

But this small avant-garde of researchers concentrated at MIT and around Boston had begun working on making the computer an amplifier of human potential, an extension of the mind and body. Taylor was known for having a good bit of intuition himself. He was considered a farsighted program officer who had a knack for picking innovative winners—both projects and researchers. He joined ARPA in early 1965, following Licklider’s departure, to work as deputy to Ivan Sutherland, IPTO’s second director. Months later, in 1966, at the age of thirty-four, Taylor became the third director of IPTO, inheriting responsibility for the community and much of the vision—indeed the very office—established by Licklider. The only difference, which turned out to be crucial, was that ARPA—now headed by Charles Herzfeld, an Austrian physicist who had fled Europe during the war—was even faster and looser with its money than it had been during Ruina’s tenure.

…

At each of the other sites, ARPA-sponsored research that would provide valuable resources to the network was already under way. Researchers at UCSB were working on interactive graphics. Utah researchers were also doing a lot of graphics work as well as investigating night vision for the military. Dave Evans, who, with Ivan Sutherland, later started Evans and Sutherland, a pioneering graphics company, was at Utah putting together a system that would take images and manipulate them with a computer. Evans and his group were also interested in whether the network could be used for more than just textual exchanges. Stanford Research Institute (later it severed its ties to Stanford and became just SRI) had been chosen as one of the first sites because Doug Engelbart, a scientist of extraordinary vision, worked there.

Computer: A History of the Information Machine

by

Martin Campbell-Kelly

and

Nathan Ensmenger

Published 29 Jul 2013

The technology of user-friendliness long predated the personal computer, although it had never been fully exploited. Almost all the ideas in the modern computer interface emanated from two of the laboratories funded by ARPA’s Information Processing Techniques Office in the 1960s: a small human-factors research group at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) and David Evans’s and Ivan Sutherland’s much larger graphics research group at the University of Utah. The Human Factors Research Center was founded at the SRI in 1963 under the leadership of Doug Engelbart, later regarded as the doyen of human-computer interaction. Since the mid-1950s, Engelbart had been struggling to get funding to develop a computer system that would act like a personal-information storage and retrieval machine—in effect replacing physical documents by electronic ones and enabling the use of advanced computer techniques for filing, searching, and communicating documents.

…

It was a stunning presentation, and although the system was too expensive to be practical, “it made a profound impression on many of the people” who later developed the first commercial graphical user interface at the Xerox Corporation. The second key actors in the early GUI movement came from the University of Utah’s Computer Science Laboratory where, under the leadership of David Evans and Ivan Sutherland, many fundamental innovations were made in computer graphics. The Utah environment supported a graduate student named Alan Kay, who pursued a blue-sky research project that in 1969 would result in a highly influential computer science PhD thesis. Kay’s research was focused on a device, which he then called the Reactive Engine but later called the Dynabook, that would fulfill the personal-information needs of an individual.

…

Arpanet would behave rather like a power grid in which lots of power plants worked in harmony to balance the load. In July 1964, when Licklider finished his two-year tenure as head of the Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO), he had a powerful say in the appointment of his successors, who shared his vision and carried it forward. His immediate successor was Ivan Sutherland, an MIT-trained graphics expert, then at the University of Utah, who held the office for two years. He was followed by Robert Taylor, another MIT alumnus, who later became head of the Xerox PARC computer science program. Between 1963 and 1966 ARPA funded a number of small-scale research projects to explore the emerging technology of computer networking.

Experience on Demand: What Virtual Reality Is, How It Works, and What It Can Do

by

Jeremy Bailenson

Published 30 Jan 2018

In my last book, Infinite Reality, we had a chapter on VR Applications, and we didn’t even touch on the subject. I can’t speak for my esteemed coauthor Jim Blascovich, but it never would have occurred to me to have a chapter about movies or news pieces. When we think of the pioneers of VR from decades ago—Jaron Lanier, Ivan Sutherland, Tom Furness—nobody was talking about storytelling, or at least not as a centerpiece of their vision. It just didn’t seem like an obvious use case, likely because of the constraints we mention above. But the film and news industry are betting, heavily, that this medium is their future. I am skeptical about a lot of it.

…

Without my having to pay any attention to my actions, let alone to type commands on a keyboard, my computer could change my gestures and other behaviors to imitate each student’s gestures and behavior. In effect, I can psychologically reduce the size of the class. Historically, one of the most successful uses of virtual reality has been to visualize factors that are impossible to see in the real world. Ivan Sutherland, in his landmark 1965 paper, “The Ultimate Display,” makes an early case for this use of VR. Sutherland points out that each of us, in our lifelong experience of the physical world, develops a set of expectations about its properties. From our senses and experience we can make predictions about how physical objects will behave with gravity, or react to each other, or appear from different perspectives.

Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration

by

Ed Catmull

and

Amy Wallace

Published 23 Jul 2009

Four years later, in 1969, I graduated from the University of Utah with two degrees, one in physics and the other in the emerging field of computer science. Applying to graduate school, my intention was to learn how to design computer languages. But soon after I matriculated, also at the U of U, I met a man who would encourage me to change course: one of the pioneers of interactive computer graphics, Ivan Sutherland. The field of computer graphics—in essence, the making of digital pictures out of numbers, or data, that can be manipulated by a machine—was in its infancy then, but Professor Sutherland was already a legend. Early in his career, he had devised something called Sketchpad, an ingenious computer program that allowed figures to be drawn, copied, moved, rotated, or resized, all while retaining their basic properties.

…

If Pixar had never existed, they would never have been born. You can turn back the clock a bit more and say that those babies’ parents might never have met if John didn’t join the production of The Adventures of André and Wally B. or if Walt Disney had never existed or if I hadn’t been lucky enough to study under Ivan Sutherland at the University of Utah. Or turn back to 1957, when I was twelve years old, returning from vacation in Yellowstone Park with my family. My dad was driving our yellow Ford ’57 station wagon, my mom was in the passenger seat and my brothers and sisters and I were piled into the back. We were traveling up a winding canyon road with a steep cliff immediately to our right and no guardrail.

Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution

by

Howard Rheingold

Published 24 Dec 2011

To develop and demonstrate this idea, my research group and I are actively building Smart Rooms (i.e., visual, audio, and haptic interfaces to environments such as rooms, cars, and office desks) and Smart Clothes (i.e., wearable computers that sense and adapt to the user and their environment). We are using these perceptually-aware devices to explore applications in health care, entertainment, and collaborative work.16 “Bits and atoms” is a major theme at MIT’s Media Lab. Ivan Sutherland started it in 1965 with his dramatic statement that “the ultimate display would, of course, be a room within which the computer can control the existence of matter. A chair displayed in such a room would be good enough to sit in. Handcuffs displayed in such a room would be confining, and a bullet displayed in such room would be fatal.”17 While others at Media Lab work in the “Things That Think” or “Tangible Bits” programs—ways to create Sutherland’s chair, if not the hypothetical bullet—Pentland and his colleagues built the first smart room in 1991.18 Cooltown and Other Informated Places On a warm October day in 2001, I drove to the end of a country road.

…

For example, imagine being able to enter an airport and see a virtual red carpet leading you right to your gate, look at the ground and see property lines or underground buried cables, walk along a nature trail and see virtual signs near plants and rocks.21 Spohrer raised the bar for technical difficulty by wanting to see the information in its context, overlaid on the real world. WorldBoard, Spohrer noted, combined, and extended the ideas of Ivan Sutherland, Warren Robinett, and Steven Feiner. Sutherland had invented computer-generated graphics in his MIT Ph.D. thesis in 1963.22 Computer graphics came a long way in forty years, from Sutherland’s first stick figure displays to today’s computer-generated feature films. Another prototype that Sutherland developed in the 1960s, the “head-mounted display,” took a less dramatic development path.23 Sutherland realized that synchronized computer displays, presented optically to each eye, yoked to a device for tracking the user’s location and position, could create a three-dimensional computer graphic either as an artificial world or as an overlay on the natural world.

Loonshots: How to Nurture the Crazy Ideas That Win Wars, Cure Diseases, and Transform Industries

by

Safi Bahcall

Published 19 Mar 2019

In the 1970s, a mob of young computer graphics pioneers flashed on the campus of the University of Utah: Jim Clark, who would go on to create Silicon Graphics; Nolan Bushnell, who would start Atari; John Warnock, who would create Adobe; and Alan Kay, who would help create the first graphics-enabled personal computer, the Alto, at Xerox. Joining them was Catmull, a mild-mannered Mormon graduate student who would cofound the greatest animated film company of his time. At Utah, Catmull created the 3D hand for a class project. He and his thesis advisor, a graphics pioneer named Ivan Sutherland, took it to Disney. Walt Disney had been a boyhood idol for Catmull, who had dreamed of becoming a Disney animator. Catmull approached the animation building like visiting a shrine. Disney, however, passed on his technology. And there would be no animation job offer for Catmull. Over the next decade, Disney, an empire built on animation, would dismiss a remarkable string of animation technologies invented by the Utah graphics alumni; just as Xerox, an empire built on office productivity, would dismiss a remarkable stream of loonshots that transformed office productivity, invented by its subsidiary Xerox PARC.

…

As an offshoot, the seismology project revived, and subsequently validated, the theory of plate tectonics. That theory permanently changed geology. DARPA funded the creation of the first major computer graphics center. It chose the University of Utah. The group at Utah, described in chapter 5, was co-led by a former DARPA program manager, Ivan Sutherland. Sutherland supervised the computer graphics PhD thesis of Ed Catmull, the Pixar founder, who has said he was “profoundly influenced” by the DARPA model of nurturing creativity. DARPA funded another engineer, named Douglas Engelbart, who built the first computer mouse, the first bitmapped screens (early graphical interfaces), the first hypertext links, and demonstrated them in 1968 at what computer scientists now refer to as the “Mother of All Demos.”

The History of the Future: Oculus, Facebook, and the Revolution That Swept Virtual Reality

by

Blake J. Harris

Published 19 Feb 2019

Unlike that mythological grail, however, virtual reality did exist, and had for quite some time.1 In 1955, cinematographer Morton Heilig wrote a paper titled “The Cinema of the Future,” which described a theater experience that encompassed all the senses.2 Seven years later, he built a prototype of what he had envisioned: an arcade-cabinet-like contraption that used a stereoscopic 3-D display, stereo speakers, smell generators, and a vibrating chair to provide a more immersive experience. Heilig named his invention the Sensorama and shot, produced, and edited five films that it could play.3 In 1965, Ivan Sutherland, an associate professor of electrical engineering at Harvard, wrote a paper titled “The Ultimate Display.”4 In it, Sutherland explicated the possibility of using computer hardware to create a virtual world—rendered in real time—in which users could interact with objects in a realistic way. “With appropriate programming,” Sutherland explained, “such a display could literally be the Wonderland into which Alice walked.”

…

But after assessing the HMDs currently on the market, Carmack wasn’t just disappointed by what was out there, he was flat out offended. In fact, with some of the headsets, the latency—meaning the lag between when someone tries to complete an action on-screen (like, say, firing a weapon) and when that action actually occurs—was actually a step back from the systems Ivan Sutherland built back in the ’60s! Granted, those Sutherland systems were ultra-expensive with low-latency CRT displays . . . but still! How could this be? Had VR really flamed out so badly in the ’90s that touching the technology was still perceived as toxic? As of late 2011, the most popular HMD was probably eMagin’s Z800 3-D visor, which cost about $900.

Troublemakers: Silicon Valley's Coming of Age

by

Leslie Berlin

Published 7 Nov 2017

One memorable time, Taylor, who sang and played guitar, took the stage with a folk band in Greece, and Licklider insisted on staying until early morning to hear every piece his colleague played. Taylor joined ARPA’s Information Processing Techniques Office in 1965 as assistant director to Licklider’s successor, Ivan Sutherland, another leading proponent of interactive computing. Taylor and Sutherland worked closely together—they were the only people in the office, aside from a secretary—and Taylor enjoyed traveling to the many campuses where ARPA had funded the development of new computer science programs. Before 1960, there were no computer science departments.

…

He was the only head of the Information Processing Techniques Office not to hold a doctorate and the only one to have taken the job without a significant record of contributions to the field. Taylor nonetheless says that for the entire time he was at ARPA, he had no sense of inferiority, even though he knew that he had not been the top choice to succeed Ivan Sutherland as director of the office.16 “There was not a one of them who I thought was smarter than me,” he says. (“I thought Lick was smarter than me,” he adds.) Taylor had graduated from high school at sixteen, had an IQ so high (154) it was written up in his small-town newspaper when he was a child, and finished college with a double major in psychology and math, as well as substantial course work in religion, English, and philosophy.17 He did not possess the principal investigators’ depth of computer science knowledge, but the breadth of Taylor’s mind was wide and his chutzpah, limitless.

Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System

by

Nick Montfort

and

Ian Bogost

Published 9 Jan 2009

One well-known media theorist who does engage both hardware and software is Friedrich Kittler. In particular, see two essays in his collection Media Information Systems, “There Is No Software” and “Protected Mode.” 2. Uston, Buying and Beating the Home Video Games, 2. 3. This sort of idea had been around in computing for a while. It was called “windowing.” Ivan Sutherland developed the technique of showing one part of a drawing in his work on the 1963 system Sketchpad. This did not mean that the use of a similar concept on a television connected to an Atari VCS, or the particular mode of navigation used in Adventure, was straightforward or obvious. 4. Buecheler, “Haunted House.” 5.

The Secret War Between Downloading and Uploading: Tales of the Computer as Culture Machine

by

Peter Lunenfeld

Published 31 Mar 2011

One of those best and brightest was the young Alan Kay. A polymath who had supported himself in grad school by playing jazz guitar, Kay had never felt comfortable in the confines of academia.16 He had traveled down to the Bay Area from the University of Utah, where he was a grad student in the lab of Ivan Sutherland. Of all the people I group together as Aquarians, perhaps the least likely to accede to the label might be Sutherland. He was a straightlaced engineer, who after his greatest contributions to the field developed a profitable company working almost exclusively on military contracts. Sutherland, buttoned-down though he may have been, was the figure who developed the visual side of computing, who opened up computing to the right brain world of artists and designers, and who crafted real-time responsive visualization technologies.

Insanely Great: The Life and Times of Macintosh, the Computer That Changed Everything

by

Steven Levy

Published 2 Feb 1994

The hidden hand in bringing this about was, of course, ARPA. It had given Evans, a former Berkeley computer scientist, a five-million-dollar grant, which allowed him to go wild with computer interactivity and graphics. Evans pried a lot of talent from vaunted computer palaces such as MIT, but the biggest prize of all was Ivan Sutherland. Sutherland had achieved canonical status in the field by devising a computer program called Sketchpad. He had concocted this as his MIT doctoral thesis in the early sixties, working on the TX-2, one of the first computers with a visual display, albeit an extremely crude one. "It filled a room," Sutherland later recalled.

Total Recall: How the E-Memory Revolution Will Change Everything

by

Gordon Bell

and

Jim Gemmell

Published 15 Feb 2009

Before we get to the effects Total Recall can have on work, health, learning, and our personal relationships, we need to take a deeper look at what science can tell us about the meeting of e-memory and bio-memory, that stuff that resides in our heads. CHAPTER 3 THE MEETING OF E-MEMORY AND BIO-MEMORY I was invited to a birthday party for computer graphics pioneer Ivan Sutherland. Would I be willing to say a few words? Great, I thought. I can get up and tell them I run into Ivan about every five years, and we enjoy our conversations. Honestly, that was all that came to me. Then I entered Ivan’s name into the search window in MyLifeBits, and to my surprise and relief, I immediately recalled emotionally evocative and intellectually intriguing details I had completely forgotten.

Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents

by

Lisa Gitelman

Published 26 Mar 2014

In contrast, Intrex and the Times Information Bank put a premium on documents, not just information, appropriating the logic of microform (and the logic of direct quotation) and delivering it to the electronic screen. Almost a decade before systems like these paired reference metadata and microfiche images on the same screen, another effort had arrived at screen-based pages by an entirely different route. Instead of reference retrieval, Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad (created in 1963) aimed at what he called “man-machine graphical communication.”27 A doctoral project created at mit , Sketchpad has been described as “the most important ancestor of today’s Computer Aided Design (cad )” as well as a key breakthrough in the history of computer graphics and the first—or at least an early—step on the path to object-oriented programming and the graphical user interface.28 It ran on the tx -2 computer with an oscilloscope cathode ray tube (crt ) display, and users interacted with graphics on the screen by means of a light pen, which they pointed at the screen while manipulating a set of buttons and switches on a keyboard and knobs on the monitor.

The Glass Cage: Automation and Us

by

Nicholas Carr

Published 28 Sep 2014

THAT’S A question the people who design buildings and public spaces have been grappling with for years. If aviators were the first professionals to experience the full force of computer automation, architects and other designers weren’t far behind. In the early 1960s, a young computer engineer at MIT named Ivan Sutherland invented Sketchpad, a revolutionary software application for drawing and drafting that was the first program to employ a graphical user interface. Sketchpad set the stage for the development of computer-aided design, or CAD. After CAD programs were adapted to run on personal computers in the 1980s, design applications that automated the creation of two-dimensional drawings and three-dimensional models proliferated.

The Friendly Orange Glow: The Untold Story of the PLATO System and the Dawn of Cyberculture

by

Brian Dear

Published 14 Jun 2017

Kay would later describe FLEX as “a small tabletop computer, and it didn’t have a very good user interface on it, and only after we had done a lot of it did we realize the user interface was really the critical part. We already had the idea that somehow the novice programmer should be able to program on it and it had an object-oriented language on the first one that I designed but not terribly well-integrated into the user interface.” Kay was influenced by the work of Ivan Sutherland, also at the University of Utah, who was a pioneer in computer graphics, as well as Douglas Engelbart, who had long ago abandoned his plasma storage device research to embark on research into user interfaces and online software for “human augmentation,” resulting in, among other things, the invention of the mouse.

…

“He mentioned one or two others who were also well regarded and had made their way in the computer community. And since I knew Dan from my Westinghouse days—I had worked at Westinghouse, as my first job in research was at Westinghouse. And Dan was one of the very well-respected Westinghouse fellows.” One of the other names Sproull mentioned was Ivan Sutherland, the wizard of interactive computer graphics. Goldman himself had come up with the idea of Pake, someone else he knew, because, it turns out, Goldman, Pake, and Alpert had all worked at Westinghouse at the same time, years earlier, when they were all still climbing up the ladder of their careers.

Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made

by

Andy Hertzfeld

Published 19 Nov 2011

We decided to include some stories written by other key original Mac team members (Steve Capps, Donn Denman, Bruce Horn, and Susan Kare), to provide a taste of the broader range of perspectives presented on the web site. The accomplishments of the original Macintosh team are a crucial link in a long chain of development that stretches back to the work of Ivan Sutherland and Doug Englebart in the 1960s, and the efforts of Alan Kay and his amazing team at Xerox PARC in the 1970s. There are also many great stories about the continuing evolution of the Macintosh platform, with surprising twists and turns as it switched to the PowerPC without skipping a beat in 1994 and, against all odds, was reunited with Steve Jobs a few years later.

Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software (Joanne Romanovich's Library)

by

Erich Gamma

,

Richard Helm

,

Ralph Johnson

and

John Vlissides

Published 18 Jul 1995

Its make: method looks like this: Given appropriate methods for initializing the MazeFactory with prototypes, you could create a simple maze with the following code: where the definition of the on: class method for CreateMaze would be Known Uses Perhaps the first example of the Prototype pattern was in Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad system [Sut63]. The first widely known application of the pattern in an object-oriented language was in ThingLab, where users could form a composite object and then promote it to a prototype by installing it in a library of reusable objects [Bor81]. Goldberg and Robson mention prototypes as a pattern [GR83], but Coplien [Cop92] gives a much more complete description.

Possiplex

by

Ted Nelson

Published 2 Jan 2010

Both of these were shadowy semisecret outfits— buildings with very public exteriors, but just what they did was secret. A lot of what they did had to do with Command and Control, i.e. missiles and warheads. However, I knew that much defense R&D had more benefit to the public as to defense—for example, Sketchpad, Ivan Sutherland’s great prototype graphics system, the granddaddy of all sketch systems today, was paid for by ARPA just as if it were a missile system. I believe Larry Roberts showed me Sketchpad at Lincoln Lab, though I’ve seen his little Sketchpad movie so often I may be confusing that with the experience itself.

The New New Thing: A Silicon Valley Story

by

Michael Lewis

Published 29 Sep 1999

There were hints that between 1970 and 1978 Clark had married at least twice, sired at least two children, moved back and forth across the country at least three times, and held at least four different jobs, mainly at universities. He did postgraduate work at the University of Utah with the forefather of computer graphics, Ivan Sutherland. In 1978 he was fired for insubordination from a post at the New York Institute of Technology, at which point a wife, not his first, left him. "I remember her saying that she couldn't live the way I lived anymore," he recalled when asked. "She just wanted a more settled life." When he said this, he was standing outside of his house, near his hill.

Nerds on Wall Street: Math, Machines and Wired Markets

by

David J. Leinweber

Published 31 Dec 2008

This two-part accident, meeting the grad student in 4,096-wire hell and seeing that I would be lucky to find a job in a godforsaken place like Oak Ridge, sent me to computer science graduate school, a step closer to becoming a quant. Harvard University, the school up the road that once wanted to merge with MIT and call the combination “Harvard,” had a fine-looking graduate program in computer science, with courses in computer graphics taught by luminaries David Evans and Ivan Sutherland. Harvard not only let me in, they paid for everything. Instead of making a right out my front door, I’d make a left. I could stay in town and continue to chase the same crowd of Wellesley girls I’d been chasing for the previous four years. I showed up in September 1974 and registered for the first of the graphics courses.

Dreaming in Code: Two Dozen Programmers, Three Years, 4,732 Bugs, and One Quest for Transcendent Software

by

Scott Rosenberg

Published 2 Jan 2006

In Lanier’s view, the programming profession is afflicted by a sort of psychological trauma, a collective fall from innocence and grace that each software developer recapitulates as he or she learns the ropes. In the early days of computing, lone innovators could invent whole genres of software with heroic lightning bolts. For his 1963 Ph.D. thesis at MIT, for example, Ivan Sutherland wrote a small (by today’s standards) program called Sketchpad—and single-handedly invented the entire field of computer graphics. “Little programs are so easy to write and so joyous,” Lanier says. “Wouldn’t it be nice to still be in an era when you could write revolutionary little programs? It’s painful to give that up.

Code: The Hidden Language of Computer Hardware and Software

by

Charles Petzold

Published 28 Sep 1999

The circuitry that controls the movements of the electron gun in the CRT (regardless of whether a raster or vector display is used) can also determine when the light from the electron gun hits the light pen and hence where the light pen is pointing on the screen. One of the first people to envision a new era of interactive computing was Ivan Sutherland (born 1938), who in 1963 demonstrated a revolutionary graphics program he had developed for the SAGE computers named Sketchpad. Sketchpad could store image descriptions in memory and display the images on the video display. In addition, you could use the light pen to draw images on the display and change them, and the computer would keep track of it all.

Who Owns the Future?

by

Jaron Lanier

Published 6 May 2013

PART SEVEN Ted Nelson CHAPTER 18 First Thought, Best Thought First Thought Ted Nelson was the first person to my knowledge to describe, starting in 1960, how you could actually implement new kinds of media in digital form, share them, and collaborate.* Ted was working so early that he couldn’t invoke basic notions like digital images, because computer graphics hadn’t been described yet. (Ivan Sutherland would see to that shortly after.) *In an even earlier article, in 1945, titled “As We May Think,” Vannevar Bush hypothesized an advanced microfilm reader, the Memex, which would essentially allow a reader to experience mash-up sequences of microfilm content. But as celebrated and influential as that article was, it did not explore the unique capabilities of digital architectures.

Rise of the Machines: A Cybernetic History

by

Thomas Rid

Published 27 Jun 2016

Kocian, “Putting Humans into Virtual Space,” in Aerospace Simulation II: Proceedings of the Conference on Aerospace Simulation II, 23–25 January, 1986, San Diego, California, Simulation Series 16, no. 2 (San Diego: Society for Computer Simulation, 1986), 215. 5.New Developments in Computer Technology Virtual Reality: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Science, Technology, and Space of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, United States Senate, One Hundred Second Congress, First Session, May 8, 1991 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1992), 24. 6.Furness and Kocian, “Putting Humans into Virtual Space,” 214. 7.At the time, Furness did not know about the work of Ivan Sutherland and Morton Heilig, two pioneers of innovative human-machine interfaces often cited in histories of virtual reality. Furness, interview, February 26, 2015. 8.“HITD601: Guest Lecture Tom Furness,” YouTube video, posted March 1, 2012, http://youtu.be/JpmM3O4vLto?t=23m55s. 9.Thomas A. Furness, “Visually-Coupled Information Systems,” in Biocybernetic Applications for Military Systems: Conference Proceedings, Chicago, April 5–7, 1978, ed.

Open Standards and the Digital Age: History, Ideology, and Networks (Cambridge Studies in the Emergence of Global Enterprise)

by

Andrew L. Russell

Published 27 Apr 2014

By using American military patronage to create and sustain “centers of excellence” in computing research at American universities such as Berkeley, MIT, Carnegie-Mellon, and Stanford in the mid-1960s, Licklider successfully mobilized the resources of the American Cold War state to create the foundations of American global leadership in computer science.13 Licklider left IPTO in 1964 and was succeeded at first by computer graphics prodigy Ivan Sutherland (1964–1966) and then by the NASA psychoacoustics researcher and computer enthusiast Robert W. Taylor. In 1966 and 1967, Taylor and his deputy Lawrence Roberts initiated a series of conversations among IPTO-supported researchers about the possibility of building a network to connect over a dozen ARPA-funded computer centers around the country.

How I Became a Quant: Insights From 25 of Wall Street's Elite

by

Richard R. Lindsey

and

Barry Schachter

Published 30 Jun 2007

JWPR007-Lindsey May 7, 2007 16:12 David Leinweber 13 Harvard University, the school up the road that once wanted to merge with MIT and call the combination Harvard, had a fine-looking graduate program in computer science with courses in computer graphics taught by luminaries David Evans and Ivan Sutherland. Harvard not only let me in—it paid for everything. Instead of making a right out my front door, I’d make a left. I could stay in town and continue to chase the same crowd of Wellesley girls I’d been chasing for the previous four years. I showed up in September 1974 and registered for the first of the graphics courses.

Makers at Work: Folks Reinventing the World One Object or Idea at a Time

by

Steven Osborn

Published 17 Sep 2013

Computing has the mouse, which we use as a hammer to shape things in the electronic world, but until recently, that has been the only way to interact with the digital things. Merrill: My personal history of the greatest moments in computing is mostly about the interface, not about the underlying depths of the computer itself. I’m a huge fan of Doug Engelbart and the invention of the mouse, and all the stuff that his team at SRI2 did in the sixties. And then Ivan Sutherland and the sketchpad work—that’s basically the precursor of tablets and stylus-based computing, which he did in the sixties at MIT. Watching Jeff Han was another moment like that. I was like, “Wow. This is really important because this is a new way that we can get a little bit closer to having a way to directly translate our thoughts into the computer doing something.”

From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism

by

Fred Turner

Published 31 Aug 2006

By all accounts, Kay was among the most devoted to making computers into user-friendly tools for communication and creative expression.19 Much of his drive in that direction came from within the world of computer research. In his first weeks in graduate school, for instance, the professor who recruited him handed him a copy of Ivan Sutherland’s 1963 MIT PhD dissertation, “Sketchpad: A Man-Machine Graphical Communications System.” In it Sutherland described how to use a light pen to create engineering drawings directly on the CRT screen of a computer. In 1968 Kay met with Seymour Papert and encountered Papert’s LOGO programming language, a language so simple that it could be used by children.

The Pentagon's Brain: An Uncensored History of DARPA, America's Top-Secret Military Research Agency

by

Annie Jacobsen

Published 14 Sep 2015

Licklider sent out his eccentric memo proposing the Pentagon create a linked computer network, which he called the “Intergalactic Computer Network.” Licklider left the Pentagon in 1965 but hired two visionaries to take over the Command and Control (C2) Research office, since renamed the Information Processing Techniques Office. Ivan Sutherland, a computer graphics expert who had worked with Daniel Slotnick on ILLIAC IV, and Robert W. Taylor, an experimental psychologist, believed that computers would revolutionize the world and that a network of computers was the key to this revolution. Through networking, not only would individual computer users have access to other users’ data, but also they would be able to communicate with one another in a radical new way.

Valley of Genius: The Uncensored History of Silicon Valley (As Told by the Hackers, Founders, and Freaks Who Made It Boom)

by

Adam Fisher

Published 9 Jul 2018

So Alan Kay had once called a computer “a bicycle for the mind.” And in fact Steve Jobs put that slogan on some of the early Apple literature. So I thought the idea of it being a “reality built for two” recalled bicycles. Alan Kay: A lot of this stuff is just modern engineering versions of old ideas. Ivan Sutherland did it first. Jim Clark: Ivan had created a head-mounted display in 1968. I had the idea that one ought to be able to work in a three-dimensional environment doing three-dimensional design. Making all that work and putting it together as a system, and doing the mathematics to make the curves and all of that, was essentially my PhD thesis.

Structure and interpretation of computer programs

by

Harold Abelson

,

Gerald Jay Sussman

and

Julie Sussman

Published 25 Jul 1996

An if expression returns an unspecified value if the predicate is false and there is no <alternative>. 30 In this way, the current time will always be the time of the action most recently processed. Storing this time at the head of the agenda ensures that it will still be available even if the associated time segment has been deleted. 31 Constraint propagation first appeared in the incredibly forward-looking SKETCHPAD system of Ivan Sutherland (1963). A beautiful constraint-propagation system based on the Smalltalk language was developed by Alan Borning (1977) at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center. Sussman, Stallman, and Steele applied constraint propagation to electrical circuit analysis (Sussman and Stallman 1975; Sussman and Steele 1980).

The Collected Stories of Vernor Vinge

by

Vernor Vinge

Published 30 Sep 2001

In 1963, just out of high school, during my first visit to Disneyland, it occurred to me that computers could be used to automate cartoon creation, putting—I thought—large-scale dramatic productions within the reach of individual artists. (Most of this has come to pass, though our largest projects still involve enormous teams of bright people.) The idea of computer animation was probably an independent insight, though I know now that people like Ivan Sutherland were already hard at work with real implementations! Years would pass before computers would be powerful enough to do high-quality motion imagery. That I got right! And this illustrates a subtle deficiency in the vision of this story (well, it’s subtle compared to the other deficiencies!). For years before the first computer-animated short features, people were talking about the possibilities.

Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs, Second Edition

by

Harold Abelson

,

Gerald Jay Sussman

and

Julie Sussman

Published 1 Jan 1984

An if expression returns an unspecified value if the predicate is false and there is no ⟨alternative⟩. 158 In this way, the current time will always be the time of the action most recently processed. Storing this time at the head of the agenda ensures that it will still be available even if the associated time segment has been deleted. 159 Constraint propagation first appeared in the incredibly forward-looking SKETCHPAD system of Ivan Sutherland (1963). A beautiful constraint-propagation system based on the Smalltalk language was developed by Alan Borning (1977) at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center. Sussman, Stallman, and Steele applied constraint propagation to electrical circuit analysis (Sussman and Stallman 1975; Sussman and Steele 1980).

The Rise of the Network Society

by

Manuel Castells

Published 31 Aug 1996

Behind the development of the Internet there was the scientific, institutional, and personal networks cutting across the Defense Department, National Science Foundation, major research universities (particularly MIT, UCLA, Stanford, University of Southern California, Harvard, University of California at Santa Barbara, and University of California at Berkeley), and specialized technological think-tanks, such as MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory, SRI (formerly Stanford Research Institute), Palo Alto Research Corporation (funded by Xerox), ATT’s Bell Laboratories, Rand Corporation, and BBN (Bolt, Beranek & Newman). Key technological players in the 1960s–1970s were, among others, J. C. R. Licklider, Paul Baran, Douglas Engelbart (the inventor of the mouse), Robert Taylor, Ivan Sutherland, Lawrence Roberts, Alex McKenzie, Robert Kahn, Alan Kay, Robert Thomas, Robert Metcalfe, and a brilliant computer science theoretician Leonard Kleinrock, and his cohort of outstanding graduate students at UCLA, who would become some of the key minds behind the design and development of the Internet: Vinton Cerf, Stephen Crocker, Jon Postel, among others.

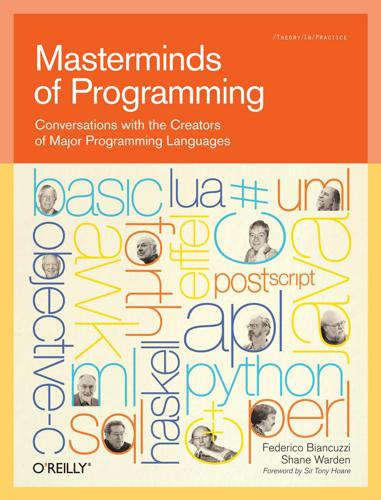

Masterminds of Programming: Conversations With the Creators of Major Programming Languages

by

Federico Biancuzzi

and

Shane Warden

Published 21 Mar 2009

Maybe this is a good way to state the main problem facing the computing field: most of its practitioners have no understanding of computing history and so, as Toynbee said about world history, they are condemned to repeat the same mistakes. Unlike scientists and engineers who build upon past discoveries, too many computing practitioners treat each system or language as a new thing, unaware that similar things have been done before. At the first OOPSLA conference in 1986, the highlight was a presentation of Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad system invented in 1963. It incorporated some of the first OO ideas long before OO was invented, and did them better than most OO systems do now. It looked fresh in 1986 and still does over 20 years later. So why do we still have many graphical tools that are inferior to Sketchpad today?

The Art of Computer Programming: Fundamental Algorithms

by

Donald E. Knuth

Published 1 Jan 1974

The origin of circular and doubly linked lists is obscure; presumably these ideas occurred naturally to many people. A strong factor in the popularization of such techniques was the existence of general List-processing systems based on them [principally the Knotted List Structures, CACM 5 A962), 161-165, and Symmetric List Processor, CACM 6 A963), 524-544, of J. Weizenbaum]. Ivan Sutherland introduced the use of independent doubly linked lists within larger nodes, in his Sketchpad system (Ph.D. thesis, Mass. Inst. of Technology, 1963). Various methods for addressing and traversing multidimensional arrays of information were developed independently by clever programmers since the ear- earliest days of computers, and thus another part of the unpublished computer folklore was born.