Literary Theory for Robots: How Computers Learned to Write

by

Dennis Yi Tenen

Published 6 Feb 2024

In her words, the mechanism “combines together general symbols, in successions of unlimited variety and extent,” establishing “a uniting link between the operations of matter and the abstract mental processes of the most abstract branch of mathematical science.” In one the most lyrical passages of her commentary Lovelace wrote, “The Analytical Engine weaves algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard-loom weaves flowers and leaves.” Let’s unpack that a bit. Remember, the misalignment between language and the world plagued our universal machines in the last chapter. When discussing “trees” for example, we usually assume the same physical referent (the actual tree). But in some cases, my idea of “trees” represents something other than what you may have had in mind.

…

There’d be no need for calculators if we were all mathematical geniuses. AI was created specifically to make us smarter. Spell-checkers and sentence autocompletion tools make better (at least, more literate) writers. In considering the amplification of average human capacity for thought, both Babbage and Lovelace circled around the idea of the Jacquard loom, an innovation in weaving manufacture that used perforated “operation cards” to pattern its designs. Within the gears of the Analytical Engine, which Lovelace called “the mill,” an operation card would rearrange or “throw” the mechanism “into a series of different states,” “determining the succession of operation in a general manner.”

…

Reading it has significantly changed my perspective on the Analytical Engine. Where at first I saw it in the lineage of thought-manipulating machines, via Kircher and Leibniz, I could now also perceive its ambition on the scale of macroeconomics, in the broader context of the industrial age. The Analytical Engine was to achieve for the world of letters what the Jacquard loom has done for the commercial weaving of fabrics. This was no mere metaphor for Babbage. Nor was it solely his invention. From the nineteenth century onward, the notion of template-based manufacturing permeated all human industry, and especially the manufacture of consumer and capital goods, like clothing, furniture, machinery, or equipment.

Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet

by

Claire L. Evans

Published 6 Mar 2018

Patterns encoded on paper, which computer scientists later called “programs,” could meaningfully entangle numbers as easily as thread. The Jacquard loom put skilled laborers, male and female, out of work. Some took out their anger on the frames of the new machines, claiming as a folk hero the apocryphal Ned Ludd, a weaver said to have smashed a pair of stocking-frames at the end of the previous century. We use the term Luddite now in the pejorative, to describe anyone with an unreasonable aversion to technology, but the cause was not unpopular in its time. Even Lord Byron sympathized. In his maiden speech to the House of Lords in 1812, he defended the organized framebreakers by comparing the results of a Jacquard loom’s mechanical weaving to “spider-work.”

…

Even as Byron made his case, Jacquard looms were producing a quality and volume of textiles unlike anything the world had ever seen. The mathematician Charles Babbage owned a portrait of Joseph-Marie Jacquard woven from thousands of silk threads using twenty-four thousand punched cards, a weaving so intricate that it was regularly mistaken for an engraving by his guests. And although the portrait was a fine possession, it was the loom itself, and its punch card programs, that really ignited Babbage’s imagination. “It is a known fact,” Babbage proclaimed, “that the Jacquard loom is capable of weaving any design which the imagination of man may conceive.”

…

As long as that imagination could be translated into a pattern, it could be infinitely reproduced, in any volume, in any material, at any level of detail, in any combination of colors, without degradation. Babbage understood the profundity of the punched-paper program because mathematical formulae work the same way: run them again and again, and they never change. He was so taken with the Jacquard loom, in fact, that he spent the better part of his life designing computing machines fed by punch cards. To describe how these worked, he even adopted the language of the textile factory, writing of a “store” to hold the numbers and a “mill” where they could be processed, analogous to a modern computer’s memory and central processing unit.

How We Got Here: A Slightly Irreverent History of Technology and Markets

by

Andy Kessler

Published 13 Jun 2005

Jacquard even figured out how to create a loop of punched cards so patterns could repeat. A Jacquard loom was destroyed in the public square in Lyon in 1806. It didn’t stop progress - by 1812, there were an amazing 18,000 Jacquard looms in France. Fashion anyone? Jacquard was awarded a lifetime pension by Napoleon and unlike anyone else in this story, Jacquard has a pattern named after him. Jacquard looms made their way to England in the 1820’s and by 1833, there were more than 100,000 working Power Looms. Surprise, surprise, not everyone was excited about this development. Disgruntled weavers in England burnt many a Jacquard loom. Others learned to shut them down by throwing a wooden shoe, known as a sabot in French, into the loom, and so became known as saboteurs.

…

Others learned to shut them down by throwing a wooden shoe, known as a sabot in French, into the loom, and so became known as saboteurs. The Jacquard looms were the first mechanical computers used for commerce, as opposed to the Pascaline for finance. The memory was punch card with holes or no holes representing binary 1’s and 0’s. The 40 HOW WE GOT HERE logic was the spring-loaded pins that depressed or lifted the warp thread. OK, no one was surfing the Web with this computer, but Jacquard set up some basic computer concepts others would build on. Punch cards? Hmm. Put that into our satchel - we might need that later, too. *** Simple arithmetic and patterns for looms are one thing, but if mathematicians wanted to do anything more, they did it by hand.

…

This was key in getting government funding. Again, a few models were demonstrated, but like his Difference Engine, the Babbage Analytic Engine never actually worked. Still, he published many papers describing how the engine POSITIVELY ELECTRIC 41 would operate if he built it. Much like the Jacquard loom, it had punch cards that contained the program and that would be fed into the Engine, which would run the program and spit out a result. This was the first idea for a stored-program computer but it would lay dormant until World War II. Babbage’s son played around with models of it late in the century that actually computed pi to 29 places; a carriage jammed while computing the 30th.

Fewer, Better Things: The Hidden Wisdom of Objects

by

Glenn Adamson

Published 6 Aug 2018

We often say this learning happens “by feel,” and the compendium of a maker’s tricks may indeed hover below the level of active consciousness. Even so, it is absolutely intrinsic to their craft. Chapter 6 TOOLING UP This gets us back to tools, for one of the very valuable things about them is the way they act as repositories of accumulated material intelligence. Once you are familiar with a fretsaw, a laser cutter, or a Jacquard loom, you will immediately recognize its effects in a finished piece of work. Furthermore, the more powerful and efficient the tool, the more it tends to determine the result. Drawings made with a computer-driven plotter more strongly reflect a predetermined aesthetic than drawings made with a pencil, not because one is digital and the other analog, but simply because the computer handles so much more of the process than the pencil does.

…

The point is often made by textile specialists that the loom was the direct historical predecessor of the computer. This is true in two senses: first, in that the earliest computer designer, the British mechanical engineer Charles Babbage, employed the same kind of punch cards in his so-called Analytical Engine as those that were used to program Jacquard looms; and second, in the more general sense that a loom, like a computer, is a machine for storing and executing very complex patterns, expressed in binary (on/off). Like any tool, but to a very advanced degree, a programmable loom is a repository for human know-how. To understand the way a loom works, it is helpful to have graph paper on hand, or at least to imagine a sheet of it.

…

More complexity can be achieved by introducing multiple colors or multiple types of fiber, each of which gets the equivalent of its own sheet of graph paper pattern in the design process. As you may appreciate, the possibility for complication becomes enormous rather quickly. This is why the Jacquard loom, named for its French inventor, Joseph Marie Jacquard, and publicly unveiled in 1801, was so important. He devised a means for storing the pattern of each pick (again, that’s each single passage of the weft thread through the textile) into a series of punch cards, chained together and fed automatically into the loom.

Wonderland: How Play Made the Modern World

by

Steven Johnson

Published 15 Nov 2016

The cards were far easier to manufacture than the metal cylinders, and they could be arranged to create an infinite number of patterns. The automated nature of Jacquard’s loom also made it more than twenty times faster than traditional drawlooms. “Using the Jacquard loom,” James Essinger writes, “it was possible for a skilled weaver to produce two feet of stunningly beautiful decorated silk fabric every day compared with the one inch of fabric per day that was the best that could be managed with the drawloom.” Joseph-Marie Jacquard displaying his loom The Jacquard loom, patented in 1804, stands today as one of the most significant innovations in the history of textile production. But its most important legacy lies in the world of computation.

…

Others take the sexual conquests: A fine overview of the arguments for the evolutionary roots of music can be found in Daniel J. Levitin’s This Is Your Brain on Music: Understanding a Human Obsession (London: Atlantic Books Ltd., 2011). “We wish to explain,” the brothers: Imad Samir, Allah’s Automata: Artifacts of the Arab-Islamic Renaissance (800-1200) (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2015), 68–86. “Using the Jacquard loom”: James Essinger, Jacquard’s Web: How a Hand-Loom Led to the Birth of the Information Age (New York: Oxford University Press, Kindle edition), 38. “You are aware”: Essinger, 47. When his collaborator Ada Lovelace: Quoted in Johnson, How We Got to Now: Six Innovations that Made the Modern World, 249.

…

227–30 artists as toolmakers, 175–81 Au Bonheur des Dames (Zola), 43–44 auditory illusions, 158–59, 165–66 automata clockworks, 6–7 Digesting Duck, 7, 79 flute player, 76–79 “Instrument Which Plays by Itself, The,” 73–76, 75 lifelike simulations of individual organisms, 7, 77 “Mechanical Turk,” 14 Writer, the, 7, 8 Babbage, Charles Analytic Engine, 10 Calculating Engine, 82 Difference Engine, 10, 14 On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, 10 inspired by Merlin’s Mechanical Museum, 9, 184, 284 interest in the technology of the Jacquard loom, 80–82 Baghdad (formerly Madinat al-Salam), 1–3 city design, 1–3 House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikma), 3 intellectual culture, 3–5 ball, importance of the, 210–15, 211, 212 Ballet Mécanique, 95–98 Balmat, Jacques, 263 Banu Musa, 3–5, 73–76 Banvard, John, 167, 172, 266 Barbon, Nicholas, 30 Barker, Robert, 5, 160–64, 167 baseball Cooperstown, New York, 199–200 lineage of, 199–200 Baudrillard, Jean, 273 Beethoven, Ludwig van, 166 Bellier-Beaumont, Ferréol, 129–30 Berry, Miles, 89 Birth of A Consumer Society, The (McKendrick, Brewer, and Plumb), 37 black belt, the, 33–34 Black Cat Tavern, 242–44 Black Death, 136–37 bodily humors, 134–35 bone flutes, 65–70, 66 Le Bon Marché, 41–46, 45 Book of Games of Chance, The (Cardano), 205, 207 Book of Ingenious Devices, The (Banu Masu), 3–5, 4, 73 Book of the Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanisms, The (al-Jazari), 2, 3–5 Boorstin, Daniel, 183 Boucicaut, Aristide, 40, 41–42, 48–49 Bradley, Milton, 195 Brand, Stewart, 219–20 Braudel, Fernand, 39–40 Brewer, John, 37 Brewster, David, 154–56, 156, 160 Brewster Stereoscope, 160 British East India Company, 28 British Magazine, 39 British Museum, 256–57 Brunelleschi, Filippo, 160, 175, 179 brutality of the Dutch regime Bandanese people of the Spice Islands, 119 Caribbean, 120, 120–21 Burrows, Edward G., 234 Burton, Mary, 235 “cabinet of wonders” (Wunderkammerns), 255–57, 256 caffeine as a memory enhancer, 247–48 as a natural weapon of the coffee plant, 247 calico “Calico Madams,” 28 made popular by window displays, 31 vivid colors of chintz and, 26–27, 27 capsaicin, 142 Cardano, Girolamo, 204, 205, 207–209, 222 Carlyle, Thomas, 153 casino games, 221–27 Caxton, William, 188 Cecil, William, 240 celebrities, 182–84 Cessolis, Jacobus de, 187–92, 194 chance.

Hacking Capitalism

by

Söderberg, Johan; Söderberg, Johan;

In the future, perhaps we can do one thing today and another tomorrow, to fish in the afternoon and hack computers after dinner, without ever becoming fishermen or computer programmers. Notes Note to Introduction 1. For an account of how the Jacquard loom worked, see James Essinger, Jacquard’s Web—How a Hand Loom Led to the Birth of the Information Age (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004). 2. Concerning the labour issues and the Jacquard loom, see Daryl Hafter “The Programmed Brocade Loom and the Decline of the Drawgirl” in ed. Martha Moore Trescott, Dynamos and Virgins Revisited: Women and Technological Change in History (London: The Scarecrow Press, 1979). 3.

…

The book is dedicated to all of you out there who make something new and interesting with it. Introduction The rise of computing, like so many other things in the modern world, could arguably be dated to the aftermath of the French Revolution. The embryo of software programs is a system of perforated cards used in the Jacquard loom and first exhibited in 1801. Joseph-Marie Jacquard’s device was the culmination of a series of inventions made during the course of the eighteenth century in the silk-weaving district of Lyon. The principal idea which he borrowed from earlier designs was the use of perforated cards to steer the loom.

…

The presence or absence of a hole could be said to represent the binary ‘one’ and ‘zero’ of the modern computer. In this way, complex textile patterns were stored in stacks of perforated cards.1 Up until then it had required great skill of the weaver to produce luxury fabric. Not only did the weavers stand to lose their mastery in the craft, the Jacquard loom could be operated by a single weaver without the help from a drawgirl. The prospect of getting rid of the drawgirl was a strong inducement to master weavers for supporting innovations in the field.2 Hardly any family in the city of Lyon was unaffected by the invention. The weavers responded promptly by wrecking the machinery.

12 Bytes: How We Got Here. Where We Might Go Next

by

Jeanette Winterson

Published 15 Mar 2021

Whether or not this meeting with Ada inspired Babbage to go further, he began that year to put together a new kind of calculating device, which he called the Analytical Engine, and this device was the world’s first non-human computer. Even though it was never built. * * * Babbage realised that the punched-cards system used on the mechanical Jacquard loom could be used to self-operate a calculating machine. No need for a crank handle. The calculating machine could also use the punched cards to store memory. This was an extraordinary insight. * * * Punched cards are stiff cards with holes in them. The Frenchman Joseph-Marie Jacquard patented a mechanism in 1804 that allowed the pattern of a piece of cloth to be expressed as a series of holes on a card.

…

The Frenchman Joseph-Marie Jacquard patented a mechanism in 1804 that allowed the pattern of a piece of cloth to be expressed as a series of holes on a card. This was a genius moment of abstract intuition – closer to the quantum-mechanical patterned universe than the 3D realism of the Industrial Revolution. It makes sense that Babbage grasped its implications for computing. Actually, it makes no sense – it was a mental leap for both men. On a Jacquard loom, the arrangement of the holes determines the pattern. Using this system meant there was no need for a master weaver to pass the weft thread laboriously under the warp thread to weave the cloth and make the pattern. It is the order of warp and weft that sets the pattern. This is skilled but repetitive work, and, as with so many of the innovations of the Industrial Revolution, by mechanising the repetition, there was no longer any need for the same level of human skill.

…

This is skilled but repetitive work, and, as with so many of the innovations of the Industrial Revolution, by mechanising the repetition, there was no longer any need for the same level of human skill. Mechanising repetition is an engineering challenge, but engineering alone isn’t the key leap of the Jacquard loom: the leap is seeing what is solid and tangible as a series of holes (in effect, empty space) arranged as a pattern. * * * Punched cards were used in the earliest commercial tabulators, and later on in early computers. They remained in use (holes in tape), as feed-in computer programmes, until the mid-1980s.

The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood

by

James Gleick

Published 1 Mar 2011

For the admission price of a shilling, a visitor could touch the “electrical eel,” listen to lectures on the newest science, and watch a model steamboat cruising a seventy-foot trough and the Perkins steam gun emitting a spray of bullets. For a guinea, she could sit for a “daguerreotype” or “photographic” portrait, by which a faithful and pleasing likeness could be obtained in “less than One Second.”♦ Or she could watch, as young Augusta Ada Byron did, a weaver demonstrating the automated Jacquard loom, in which the patterns to be woven in cloth were encoded as holes punched into pasteboard cards. Ada was “the child of love,” her father had written, “—though born in bitterness, and nurtured in convulsion.”♦ Her father was a poet. When she was barely a month old, in 1816, the already notorious Lord Byron, twenty-seven, and the bright, wealthy, and mathematically knowledgeable Anne Isabella Milbanke (Annabella), twenty-three, separated after a year of marriage.

…

What caught Babbage’s fancy was not the weaving, but rather the encoding, from one medium to another, of patterns. The patterns would appear in damask, eventually, but first were “sent to a peculiar artist.” This specialist, as he said, punches holes in a set of pasteboard cards in such a manner that when those cards are placed in a Jacquard loom, it will then weave upon its produce the exact pattern designed by the artist.♦ The notion of abstracting information away from its physical substrate required careful emphasis. Babbage explained, for example, that the weaver might choose different threads and different colors—“but in all these cases the form of the pattern will be precisely the same.”

…

Bitter as he was about England’s waning interest in his visionary plans, Babbage found admirers on the continent, particular in Italy—“the country of Archimedes and Galileo,” as he put it to his new friends. In the summer of 1840 he gathered up his sheaves of drawings and journeyed by way of Paris and Lyon, where he watched the great Jacquard loom at Manufacture d’Étoffes pour Ameublements et Ornements d’Église, to Turin, the capital of Sardinia, for an assembly of mathematicians and engineers. There he made his first (and last) public presentation of the Analytical Engine. “The discovery of the Analytical Engine is so much in advance of my own country, and I fear even of the age,”♦ he said.

Darwin Among the Machines

by

George Dyson

Published 28 Mar 2012

Babbage began the design of the analytical engine in 1834 and was still constructing pieces of it in his own workshops when he was eighty years of age. The engine was designed to be able to manipulate its own internal storage registers while reading and writing to and from an unbounded storage medium—strings of punched pasteboard cards, adapted by Babbage from those used by the card-controlled Jacquard loom. A prototype Jacquard mechanism had been introduced in 1801; some eleven thousand Jacquard looms were in use by 1812. In specifying punched-card peripheral equipment, Babbage set a precedent that stood for 150 years. The technology was proven, available, and suited to performing complex functions on extensive data sets. (One demonstration weaving project, a silk portrait of Jacquard, required a sequence of twenty-four thousand cards.)

…

The appearance of Marquand’s “vastly more clear-headed contrivance” prompted Peirce to compose a short paper titled “Logical Machines” (1887), in which he considered “precisely how much of the business of thinking a machine could possibly be made to perform, and what part of it must be left for the living mind.”13 Despite the primitive abilities evidenced so far, Peirce advised consideration of “how to pass from such a machine as that to one corresponding to a Jacquard loom.”14 Ill at ease in more academic surroundings, Peirce spent thirty years working for the U.S. Coast Survey, where his duties included working as a (human) computer on the Nautical Almanac and conducting gravitational research. He compiled large sections of the eight-thousand-page Century Dictionary and was both physically and mentally ambidextrous, able to write out a question and its answer using both hands at the same time.

…

The 1880 census took almost seven years to completely count. If methods were not improved, the 1890 census would not be completed by the time the 1900 census began. Hollerith’s supervisor, Dr. John S. Billings, encouraged his protégé to tabulate data by means of perforated cards, citing the precedent of railway tickets but not Babbage’s engine or the Jacquard loom. Once a card was punched the data could then be read, sorted, and tabulated by machine. As a demonstration project Billings arranged for Hollerith to tabulate vital statistics for the Baltimore Department of Health. Hollerith made the most of this opportunity, although, as his mother-in-law wrote in 1889, “he is completely tired out.

The Secret War Between Downloading and Uploading: Tales of the Computer as Culture Machine

by

Peter Lunenfeld

Published 31 Mar 2011

For the 10 SECRET WAR volume is not only an exquisite nineteenth-century reinterpretation of the medieval book of hours, it is also the unknown—and unknowing—origin point for contemporary screen culture. Manufactured in Lyon by A. Roux between 1886 and 1887, this Livre de prièrs was the first and apparently only woven rather than printed book in bibliographic history.17 Manufactured on the programmable Jacquard loom that enabled French industry to dominate the market for complex textiles, the Livre de prières was so intricate that it required hundreds of thousands of punch cards to produce.18 It took A. Roux fifty tries to create the first salable version of this marvel of mixed technological metaphors, wherein Ariadne meets Gutenberg.

…

campaign, 31 Gould, Stephen Jay, 133 Graphic design, 31, 45, 64, 102, 181n7 Graphic user interface, 161 Great Depression, 107 Great Wall of China, 75 Greek myths, 75, 175 Greenwich Village, 84–85 Grey Album, The (Danger Mouse), 54–55 Gropius, Walter, 36 Guardian syndrome, 85–86 Guggenheim Bilbao, 39 Gulags, 107 Gutenberg press, 11, 137–138 Gysin, Brion, 52 Habits of mind, 9–10 Hackers, 22–23, 54, 67, 69, 162, 170–173 Hartmann, Frank, 125 Harvard Business Review, 112 Harvard Crimson, 36 Hasids, 135 Headline News (CNN), 58 Heidegger, Martin, 29 Heisenberg, Werner, 37 Hello Kitty, 90 Hewlett, Bill, 145, 157 Hewlett-Packard (HP), 149, 153, 172 Hierarchies cultural, 1, 24, 29, 93, 114 technical, 123, 155, 175–176, 189n8 High fructose corn syrup (HFCS), 4, 7–9, 181n6 Hindus, 135 Hip-hop, 53–54, 61 Hirai, Kazumasa, 108 Hiroshima, 100–101 Hitchcock, Alfred, 44 Holocaust, 107 Homebrew Computer Club, 163 Homer, 28, 93–95 Hope (campaign poster), 31 Hosts Berners-Lee and, 144, 167–169, 175 description of term, xv Stallman and, 170–171 Torvalds and, 144, 167–173 World Wide Web and, xv “House of Cards” (Radiohead), 39 Howe, Jeff, 189n14 Hustlers, 156 description of term, xv desktops and, xv Gates and, 144, 162–166, 196n21 Jobs and, 144, 162–167, 186n12, 196n21 Hypercontexts, xvi, 7, 48, 76–77 Hyperlinking, 52–53, 57, 150 205 INDEX Hypertextuality, 51–53, 108, 145, 150, 158, 166, 168 IBM, 145, 170, 195n11 as Big Blue, 156, 164 Gates and, 164–165 650 series and, 154–155 System/360 series and, 155 Watsons and, 144, 153–157, 165–166 Iliad (Homer), 28 I Love Lucy (TV show), 47 India, 135 Individualism, 13, 98 Information, 98 algorithms and, 46, 144, 174–177 bespoke futures and, 100–101, 124– 126, 190n8, 193n34 culture machine and, 143–149, 152– 153, 163, 167–168, 172, 176–178, 196n17, 197n29 downloading/uploading and, 1, 4, 11 Gutenberg press and, 11, 137, 138 mashing and, 25, 54–55, 57, 74 Neurath and, 125 overload of, 81 peer-to-peer networks and, 15, 54, 92, 116, 126 Shannon and, 148 stickiness and, 22–23, 32–35, 184n15 storage and, 47, 60, 153, 196n17 unimodernism and, 45–49, 55, 60, 65–66, 74 Web n.0 and, 80–81, 92 World War II and, 146–147 Information overload, 22, 149 Info-triage, xvi, 20–23, 121, 132, 143 Infoviz, 58 Intel, 149, 156 Intellectual property copyright and, 54, 88–95, 123, 164, 166, 173, 177 Mickey Mouse Protection Act and, 90 public domain and, 91 Interactive environments, xiv, 24, 39, 57, 69, 71, 83, 114–119, 126 Intergalactic Computer Network, 108, 152, 168 International System of Typographic Picture Education, 125 Internet, xiii, 180n1, 184n15 AOL television and, 9 development of computer and, 145, 168–171, 174 stickiness and, 15, 22, 27, 30 unimodernism and, 56 viral distribution and, 30, 56, 169 Web n.0 and, 79, 83, 92 Interpretation of Dreams (Freud), 43–44 Interventionism, 14, 41, 126, 190n8 IOD, 39 IPad, 167 IPhone, 15, 167 Iraq, 100 Islam, 134 Isotypes, 44, 125, 193n34 Israeli settler movement, 135 ITunes, 167 Jackson, Samuel L., 30 Jacobs, Jane, 84–86 Jacquard loom, 11 James, William, 128 Japanese art, xi, 49 Jay Z, 55 Jazz, 25–27, 160 Jevbratt, Lisa, 39 Jobs, Steve, 144, 162–167, 186n12, 196n21 Joyce, James, 94–95 Junk culture, 5–10 Kael, Pauline, 135 Kawai art, xi Kay, Alan, 144, 157, 160–167, 195n16, 206 INDEX as patriarch, 144, 147–148, 151–152, 163, 168 personal computers and, 152 symbiosis and, 151–152 vision of participation by, 151–152 Life hacking, 22 Lincoln Center, 85 Linnaeus, Carolus, 80 Linux, 75, 169–173, 197n27 Livre de prières tissé’ d’apres les enlumineurs des manuscrits du XIVe au XVIe siècle (Roux), 10–11 London, 25–26, 100, 130 Looking Backward (Bellamy), 108 Lorenz, Edward, 117–118 Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (Banham), 10 Lost (TV show), 181n8 Love letter generator, 18–19 Lucky Jim (Amis), 32 Luhrmann, Baz, 60–63 Lynn, Greg, 64 Kay, Alan (continued) 196n17 Kennedy, John F., xi Kino-eye, 44 Kiss (band), 63 “Kitch’s Bebop Calypso” (song), 25–27 Koblin, Aaron, 39 Kodak, 15 Koolhaas, Rem, 49 Koran, 28 Kraus, Karl, 66, 75 Krikalev, Sergei K., 50–51 Kubrick, Stanley, 107 Kuwata, Jiro, 108 Langer, Ellen J., 183n6 Language bespoke futures and, 126, 135 calypso and, 25 hypertextuality and, 51–53, 108, 145, 150, 158, 166, 168 Joyce and, 94 mass culture and, 31 PostScript and, 55–56 Larrey, Dominique Jean, 21 Larson, Jonathan, 61 Latour, Bruno, 130, 185n19 Leary, Timothy, 145 Le Corbusier, 44 Léger, Fernand, 45 Legibility wars, 31 Lehmann, Chris, 184n16 Leibniz, Gottfried, 149 Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (Agee and Burroughs), 40–41 Levine, Sherrie, 41 Libertarianism, 13, 98 Library of Congress, 89 Licensing, 164–165 Licklider, J.C.R.

…

, 71 Spielraum (play space), 75 Spin, 124 Stallman, Richard, 170–171 Stanford, 144, 149, 158–159, 162, 175 Stardust@home, 122–123 Stardust Interstellar Dust Collector (SIDC), 193n33 Sterling, Bruce, 101–102 Stewart, Jimmy, 44 Stickiness defining, 28, 184n15 downloading and, 13–17, 20–23, 27–29, 184n15 duration and, 28 fan culture and, 28–32, 48, 49, 87 gaming and, 70–74 214 INDEX Systems theory, 151 Stickiness (continued) information and, 22–23, 32–35 markets and, 13, 16, 24, 30–33, 37 modernism and, 36 networks and, 16–17, 22, 24, 29–36 obsessiveness and, 28 play and, 32–34, 70–74 power and, 32–34 simulation and, 15–19, 27, 32, 35 Teflon objects and, 28–32, 49, 87 toggling and, 33–34, 43, 102, 197n30 tweaking and, xvi, 32–35, 185nn22,23 unfinish and, 34–37, 76–77 unimodernism and, 70–74 uploading and, 13–17, 20, 23–24, 27–29 Web n.0 and, 79, 87 Stock options, 98 Stone, Linda, 34 Storage, 47, 60, 153, 196n17 Strachey, Christopher, 18–19 Strachey, Lytton, 19 Strange attractors, xvi, 117–120, 192n27 Sturges, Preston, 88 Stutzman, Fred, 22 Stewart, Martha, 49 Suburbs, 3, 8 Suicide bombers, 100–101 Sullivan’s Travels (Sturges), 88 Sun Microsystems, 172, 176 Superflat art, xi, 49 Supersizing, 3–4 Suprematism, 117 Surfing, 20, 80, 180n2 Surrealism, 31 Sutherland, Ivan, 160–161 Swiss Army Knife theory, 17 Symbiosis, 151–152 Synthetism, 117 Systems of Survival: A Dialogue on the Moral Foundations of Commerce and Politics (Jacobs), 85–86 Take-home consumption, 3 Tarantino, Quentin, 49 Taxonomies, 80–83 Technology analog, 18, 53, 150 anticipated, 108–110 bespoke futures and, 98–104, 107–113, 116, 119, 125–127, 131– 133, 136–139 broadband, 9, 57 cell phones, xiii, xvii, 17, 23, 42, 53, 56, 76, 101 commercial networks and, 4–5 compact discs (CDs), 2, 48, 53 computer mouse, 158–159 culture machine and, 143–163, 173–174 cyberpunk maxim on, 87 determinism and, 131–132 difference engine, 149 digital video discs (DVDs), 2, 7–8, 15, 58 dot-com bubble and, 79, 174 Dynabook, 161–162, 196n17 Ethernet, 161 Exhibition of the Achievement of the Soviet People’s Economy (VDNX) and, 102–105 film cameras, 15 Gutenberg press, 11, 137–138 hierarchical structures and, 123, 155, 175–176, 189n8 historical perspective on computer, 143–178 hypertext and, 158 information overload and, 22, 149 Jacquard loom, 11 mechanical calculator, 149 Metcalfe’s corollary and, 86–87 microfilm, 149–150 215 INDEX Technology (continued) Moore’s law and, 156, 195n13 New Economy and, 97, 99, 104, 131, 138, 144–145, 190n3 personal digital assistants (PDAs), 17 Photoshop, 131 progress and, 132 RFID, 65 secular culture and, 133–139 storage, 47, 60, 153, 196n17 technofabulism and, 99–100 teleconferencing, 158–159 3–D tracking, 39 tweaking and, 32–35, 185nn22,23 videocassette recorders (VCRs), 15, 23 wants vs. needs and, 4 woven books, 10–11 Teflon objects, 28–32, 49, 87 Teleconferencing, 158–159 Television as defining Western culture, 2 aversion to, xii bespoke futures and, 101, 108, 124, 127–129, 133–137 delivery methods for, 2 dominance of, xii, 2–10 downloading and, 2 as drug, xii, 7–9 general audiences and, 8–9 habits of mind and, 9–10 Internet, 9 junk culture and, 5–10 Kennedy and, xi macro, 56–60 marketing fear and, xvii overusage of, 7–9 as pedagogical boon, 14 quality shows and, 7 rejuveniles and, 67 Slow Food and, 6–7 spin-offs and, 48 as time filler, 67 U.S. ownership data on, 180n2 Telnet, 169 “Ten Tips for Successful Scenarios” (Schwartz and Ogilvy), 113 Terrorism, 99–101, 130–131, 134, 137 Textiles, 11 Text-messaging, 82 3COM, 86 3–D tracking, 39 Tiananmen Square, 104 Timecode (Figgis), 58 Time magazine, xii, 145 Time Warner, 63, 91 Tin Pan Alley, 28, 63 Tintin, 90 Toggling, xvi, 33–34, 43, 102, 197n30 Tools for Thought (Rheingold), 145 Torvalds, Linus, 144, 167–173 Tracy, Dick, 108 Traitorous Eight, 156 Trilling, Lionel, 79 Turing, Alan, 17–20, 52, 148 Turing Award, 17, 156 Tweaking, xvi, 32–35, 185nn22,23 20,000 Leagues beneath the Sea (Verne), 108 Twins paradox, 49–50 Twitter, 34, 180n2 2001 (film), 107 Ubiquity, xiii bespoke futures and, 125, 128 culture machine and, 144, 166, 177–178 folksonomies and, 80–81 Freedom software and, 22–23 hotspots and, xiv information overload and, 22, 149 isotypes and, 125 stickiness and, 22–23 unimodernism and, 39, 53, 57–59, 62, 74 216 INDEX simulation and, 39, 49, 53–54, 57, 71–76 soundscape and, 53–55 stickiness and, 70–74 twins paradox and, 49–50 unconscious and, 43–44 unfinish and, 51, 67, 70, 76–78 unimedia and, 39–40 uploading and, 42, 49, 53, 57, 67, 77 WYMIWYM (What You Model Is What You Manufacture) and, 64–67 WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) and, 55–56, 64–65 United States Cuban Missile Crisis and, xi September 11, 2001 and, 99–101, 130 television’s dominance and, 2, 180n2 Universal Resource Locator (URL), 168–169 Universal Turing Machine, 18–19 University of Pennsylvania, 148 University of Utah, 160 UNIX, 170–171 “Untitled (After Walker Evans)” (Levine), 41 Uploading, xiii–xiv, 180nn1,2 activity levels and, 5 animal kingdom and, 1 bespoke futures and, 97, 120–123, 128–129, 132 commercial networks and, 4–5 communication devices and, 15–16 conversation and, 13 cultural hierarchy of, 1–2 culture machine and, 143, 168, 173, 175 disproportionate amount of to downloading, 13 humans and, 1–2 information and, 1, 4, 11 meaningfulness and, xvi, 29 stickiness and, 13–17, 20, 23–24, 27–29 Ubiquity (continued) Web n.0 and, 79–95 Ublopia, 101 Ulysses (Joyce), 94–95 Uncertainty principle, 37 Unfinish, xvi bespoke futures and, 127–129, 136 continuous partical attention and, 34 perpetual beta and, 36 stickiness and, 34–37, 76–77 unimodernism and, 51, 67, 70, 76–78 Web n.0 and, 79, 92 Unimedia, 39–40 Unimodernism Burroughs and, 40–42 common sense and, 44–45 DIY movements and, 67–70 downloading and, 41–42, 49, 54–57, 66–67, 76–77 figure/ground and, 42–43, 46 gaming and, 70–74 hypertextuality and, 51–53 images and, 55–56 information and, 45–49, 55, 60, 65–66, 74 Krikalev and, 50–51 macrotelevision and, 56–60 markets and, 45, 48, 58–59, 71, 75 mashing and, 25, 54–55, 57, 74 mechanization and, 44–45 microcinema and, 56–60 modders and, 69–70 Moulin Rouge and, 60–63 narrative and, 58–59, 67, 71, 76 networks and, 39, 47–48, 54–57, 60, 64–65, 68–69, 73–74 participation and, 54, 66–67, 74–77 perception pops and, 43–49 play and, 67–77 postmodernism and, 39–41, 74 remixing and, 39, 53–54, 62–63, 70 running room and, 74–77 217 INDEX Uploading (continued) unimodernism and, 42, 49, 53, 57, 67, 77 Web n.0 and, 79–83, 86–87, 91 Urban planning, 84–86 U.S.

Computer: A History of the Information Machine

by

Martin Campbell-Kelly

and

Nathan Ensmenger

Published 29 Jul 2013

Thus, even as he wrestled with the complexities of the Analytical Engine, Babbage the economist was never far below the surface. For about two years Babbage struggled with the problem of organizing the calculation—the process we now call programming, but for which Babbage had no word. After toying with various mechanisms, such as the pegged cylinders of barrel organs, he hit upon the Jacquard loom. Invented in 1802, the Jacquard loom had started to come into use in the English weaving and ribbon-making industries in the 1820s. It was a general-purpose device that, when instructed by specially punched cards, could weave infinite varieties of pattern. Babbage envisaged just such an arrangement for his Analytical Engine.

…

Lovelace had a poetic turn of phrase, which Babbage never had, and this enabled her to evoke some of the mystery of the Analytical Engine that must have appeared truly remarkable to the Victorian mind: The distinctive characteristic of the Analytical Engine, and that which has rendered it possible to endow mechanism with such extensive faculties as bid fair to make this engine the executive right hand of abstract algebra, is the introduction into it of the principle which Jacquard devised for regulating, by means of punched cards, the most complicated patterns in the fabrication of brocaded stuffs. . . . We may say most aptly that the Analytical Engine weaves algebraical patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves. This image of weaving mathematics was an appealing metaphor among the first computer programmers in the 1940s and 1950s. One should note, however, that the extent of Lovelace’s intellectual contribution to the Sketch has been much exaggerated. She has been pronounced the world’s first programmer and even had a programming language (Ada) named in her honor.

…

memex as predecessor to, 200 (photo), 278–279, 293 Minitel and, 196 (photo), 269–271 mobile computing, 296–299 privacy issues, 302, 305 privatization of, 291–296 regulation of, 304–305 role in political change, 303–305 social networking, 300–305 See also World Wide Web Internet Explorer, 290–291 Internet service provider (ISP), 290 Iowa State University, 68–70, 79 IT programming language, 174 Jacquard loom, 43, 44, 56 Jenner, Edward, 286 Jobs, Steve Apple Computer co-founded by, 238–241, 249, 251 computer liberation movement and, 234 consumer electronics and, 297–298 Macintosh development and, 261–263 personal computer development and, 229 Kahn, Herman, 137 Kay, Alan, 259, 260, 296 Kemeny, John, 192 (photo), 205–206 Keyboards, 22, 23 Kilburn, Tom, 93 (photo) Kildall, Gary, 246, 264–265, 267–268 Kurtz, Thomas E., 192 (photo), 205–206 Lake, Claire D., 57 Laplace, Pierre-Simon, 5 Laptop computers, 296, 298 Lardner, Dionysius, 45 LCD screens, 296 Learson, T.

The Innovators: How a Group of Inventors, Hackers, Geniuses and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution

by

Walter Isaacson

Published 6 Oct 2014

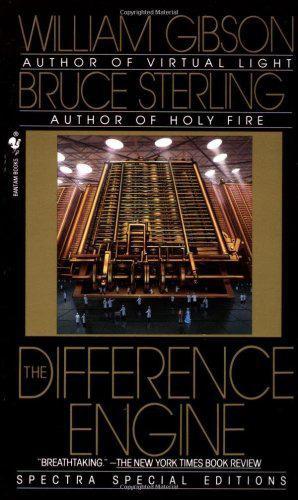

One would be in charge of adding 2 to the last number in column B, and then would hand that result to another person, who would add that result to the last number in column A, thus generating the next number in the sequence of squares. Replica of the Difference Engine. Replica of the Analytical Engine. The Jacquard loom. Silk portrait of Joseph-Marie Jacquard (1752–1834) woven by a Jacquard loom. Babbage devised a way to mechanize this process, and he named it the Difference Engine. It could tabulate any polynomial function and provide a digital method for approximating the solution to differential equations. How did it work? The Difference Engine used vertical shafts with disks that could be turned to any numeral.

…

In enabling a mechanism to combine together general symbols, in successions of unlimited variety and extent, a uniting link is established between the operations of matter and the abstract mental processes.37 Those sentences are somewhat clotted, but they are worth reading carefully. They describe the essence of modern computers. And Ada enlivened the concept with poetic flourishes. “The Analytical Engine weaves algebraical patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves,” she wrote. When Babbage read “Note A,” he was thrilled and made no changes. “Pray do not alter it,” he said.38 Ada’s second noteworthy concept sprang from this description of a general-purpose machine. Its operations, she realized, did not need to be limited to math and numbers.

…

“Simple things should be simple, complex things should be possible,” he declared.62 Kay wrote a description of the Dynabook, titled “A Personal Computer for Children of All Ages,” that was partly a product proposal but mostly a manifesto. He began by quoting Ada Lovelace’s seminal insight about how computers could be used for creative tasks: “The Analytical Engine weaves algebraical patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.” In describing how children (of all ages) would use a Dynabook, Kay showed he was in the camp of those who saw personal computers primarily as tools for individual creativity rather than as networked terminals for collaboration. “Although it can be used to communicate with others through the ‘knowledge utilities’ of the future such as a school ‘library,’ ” he wrote, “we think that a large fraction of its use will involve reflexive communication of the owner with himself through this personal medium, much as paper and notebooks are currently used.”

How to Create a Mind: The Secret of Human Thought Revealed

by

Ray Kurzweil

Published 13 Nov 2012

There is actually one genuine forerunner to von Neumann’s concept, and it comes from a full century earlier! English mathematician and inventor Charles Babbage’s (1791–1871) Analytical Engine, which he first described in 1837, did incorporate von Neumann’s ideas and featured a stored program via punched cards borrowed from the Jacquard loom.4 Its random access memory included 1,000 words of 50 decimal digits each (the equivalent of about 21 kilobytes). Each instruction included an op code and an operand number, just like modern machine languages. It did include conditional branching and looping, so it was a true von Neumann machine.

…

She wrote programs for the Analytical Engine, which she needed to debug in her own mind (since the computer never worked), a practice well known to software engineers today as “table checking.” She translated an article by the Italian mathematician Luigi Menabrea on the Analytical Engine and added extensive notes of her own, writing that “the Analytical Engine weaves algebraic patterns, just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.” She went on to provide perhaps the first speculations on the feasibility of artificial intelligence, but concluded that the Analytical Engine has “no pretensions whatever to originate anything.” Babbage’s conception is quite miraculous when you consider the era in which he lived and worked.

…

J., 75 frontal lobe, 36, 41, 77 fusiform gyrus, 89, 95, 111 gambling, 106 ganglion cells, 95 García Márquez, Gabriel, 3–4, 283n–85n Gazzaniga, Michael, 226–29, 234 General Electric, 149 genetic (evolutionary) algorithms, see evolutionary (genetic) algorithms genome, human, 4, 103, 251 design information encoded in, 90, 147, 155, 271, 314n–15n redundancy in, 271, 314n, 315n sequencing of, LOAR and, 252, 252, 253 see also DNA George, Dileep, 41, 73, 156 Ginet, Carl, 234 God, concept of, 223 Gödel, Kurt, 187 incompleteness theorem of, 187, 207–8 “God parameters,” 147 Good, Irvin J., 280–81 Google, 279 self-driving cars of, 7, 159, 261, 274 Google Translate, 163 Google Voice Search, 72, 161 Greaves, Mark, 266–72 Grossman, Terry, 287n–88n Grötschel, Martin, 269 Hameroff, Stuart, 206, 208, 274 Hameroff-Penrose thesis, 208–9 Hamlet (Shakespeare), 209 Harnad, Stevan, 266 Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (Rowling), 117 Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Rowling), 121 Hasson, Uri, 86 Havemann, Joel, 25 Hawkins, Jeff, 41, 73, 156 Hebb, Donald O., 79–80 Hebbian learning, 80 hemispherectomy, 225 hidden Markov models (HMMs), 68, 141–44, 143, 145, 147, 162 hierarchical hidden Markov models (HHMMs), 51, 68, 72, 74, 144–46, 149–50, 152–53, 155, 156, 162, 164, 167–68, 195, 269, 270 pruning of unused connections by, 144, 147, 155 hierarchical learning, 164, 195, 197 hierarchical memory: digital, 156–57 temporal, 73 hierarchical systems, 4, 35 hierarchical thinking, 8, 69, 105, 117, 153–54, 177, 233, 286n bidirectional flow of information in, 52 language and, 56, 159, 162, 163 in mammalian brain, 2–3 pattern recognition as, 33, 41–53 recursion in, 3, 7–8, 56, 65, 91, 109, 156, 177 routine tasks and, 32–33 as survival mechanism, 79 as unique to mammalian brain, 35 hippocampus, 63, 77, 101–2 Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, The (Adams), 161 Hobbes, Thomas, 278 Hock, Dee, 113 Horwitz, B., 75 Hubel, David H., 34 Human Connectome Project, 129 human genome, see genome, human Human Genome Project, 251, 273 humans: merger of intelligent technology with, 266–72, 276, 279–82 tool-making ability of, 3, 27, 276, 279 Hume, David, 234–35 IBM, 6–7, 108, 128, 165–66 Cognitive Computing Group of, 195 ideas, recursive linking of, 3 identity, 10, 11, 240–47 as pattern continuity, 246, 247 thought experiments on, 242–47 importance parameters, 42, 60, 66, 67 incompatibilism, 234, 236 incompleteness, Gödel’s theorem of, 187, 207–8 inference engines, 162–63 information, encoding of: in DNA, 2, 17, 122 evolution and, 2 in human genome, 90, 147, 155, 271, 314n–15n information structures, carbon-based, 2 information technologies: exponential growth of, 278–79 LOAR and, 4, 249–57, 252, 257, 258, 259, 260, 261, 261 inhibitory signals, 42, 52–53, 67, 85, 91, 100, 173 insula, 99–100, 99, 110 integrated circuits, 85 Intel, 268 intelligence, 1–2 emotional, 110, 194, 201, 213 as evolutionary goal, 76–78, 277, 278 evolution of, 177 as problem-solving ability, 277 International Dictionary of Psychology (Sutherland), 211 “International Technology Roadmap for Semiconductors,” 268 Internet, exponential growth of, 254 Interpretation of Dreams, The (Freud), 66 intuition, linear nature of, 266 invariance, in pattern recognition, 30, 59–61, 133, 135, 137, 175 and computer emulation of brain, 197 one-dimensional representations of data and, 141–42 vector quantization and, 141 inventors, timing and, 253, 255 I, Robot (film), 210 Jacquard loom, 189, 190 James, William, 75–76, 98–99 Jeffers, Susan, 104 Jennings, Ken, 157–58, 165 Jeopardy! (TV show), 6–7, 108, 157–58, 160, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169, 172, 178, 232–33, 270 Joyce, James, 55 Kasparov, Garry, 39, 166 K Computer, 196 knowledge bases: AI systems and, 4, 6–7, 170–71, 246, 247 of digital neocortex, 177 exponential growth of, 3 as inherently hierarchical, 220 language and, 3 professional, 39–40 as recursively linked ideas, 3 Kodandaramaiah, Suhasa, 126 Koene, Randal, 89 Koltsov, Nikolai, 16 Kotler, Steven, 278 KurzweilAI.net, 161 Kurzweil Applied Intelligence, 144 Kurzweil Computer Products, 122 Kurzweil Voice, 160 lamina 1 neurons, 97 language: chimpanzees and, 3, 41 and growth of knowledge base, 3 hierarchical nature of, 56, 159, 162, 163 as metaphor, 115 as translation of thinking, 56, 68 language software, 51, 72–73, 92, 115–16, 122–23, 144–45, 145, 156, 157–72, 174, 270 expert managers in, 166–67 hand-coded rules in, 164–65, 166, 168 HHMMs in, 167–68 hierarchical systems in, 162–65 Larson, Gary, 277 “Last Voyage of the Ghost, The” (García Márquez), 3–4 lateral geniculate nucleus, 95, 100 law of accelerating returns (LOAR), 4, 6, 7, 41, 123 as applied to human brain, 261–63, 263, 264, 265 biomedicine and, 251, 252, 253 communication technology and, 253, 254 computation capacity and, 281, 316n–19n information technology and, 4, 249–57, 252, 257, 258, 259, 260, 261, 261 objections to, 266–82 predictions based on, 256–57, 257, 258, 259, 260, 261 and unlikelihood of other intelligent species, 5 “Law of Accelerating Returns, The” (Kurzweil), 267 laws of thermodynamics, 37, 267 learning, 61–65, 122, 155, 273–74 conditionals in, 65 and difficulty of grasping more than one conceptual level at a time, 65 in digital neocortex, 127–28, 175–76 environment and, 119 Hebbian, 80 hierarchical, 164, 195, 197 in neural nets, 132–33 neurological basis of, 79–80 pattern recognition as basic unit of, 80–81 of patterns, 63–64, 90 recognition as simultaneous with, 63 simultaneous processing in, 63, 146 legal systems, consciousness as basis of, 212–13 Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm, 34, 223 Lenat, Douglas, 162 Leviathan (Hobbes), 278 Lewis, Al, 93 Libet, Benjamin, 229–30, 231, 234 light, speed of, 281 Einstein’s thought experiments on, 18–23 linear programming, 64 LISP (LISt Processor), 153–55, 163 pattern recognition modules compared with, 154, 155 Lloyd, Seth, 316n, 317n Loebner, Hugh, 298n Loebner Prize, 298n logic, 38–39 logical positivism, 220 logic gates, 185 Lois, George, 113 love, 117–20 biochemical changes associated with, 118–19 evolutionary goals and, 119 pattern recognition modules and, 119–20 “Love Is the Drug,” 118 Lovelace, Ada Byron, Countess of, 190, 191 lucid dreaming, 72, 287n–88n Lyell, Charles, 14–15, 114, 177 McCarthy, John, 153 McClelland, Shearwood, 225 McGinn, Colin, 200 magnetic data storage, growth in, 261, 301n–3n magnetoencephalography, 129 Manchester Small-Scale Experimental Machine, 189 Mandelbrot set, 10–11, 10 Marconi, Guglielmo, 253 Mark 1 Perceptron, 131–32, 134, 135, 189 Markov, Andrei Andreyevich, 143 Markram, Henry, 80–82, 124–27, 129 mass equivalent, of energy, 22–23 Mathematica, 171 “Mathematical Theory of Communication, A” (Shannon), 184 Mauchly, John, 189 Maudsley, Henry, 224 Maxwell, James Clerk, 20 Maxwell, Robert, 225 Mead, Carver, 194–95 medial geniculate nucleus, 97, 100 medicine, AI and, 6–7, 39, 108, 156, 160–61, 168 memes: consciousness as, 211, 235 free will as, 235 memory, in computers, 185, 259, 260, 268, 301n–3n, 306n–7n memory, memories, human: abstract concepts in, 58–59 capacity of, 192–93 computers as extensions of, 169 consciousness vs., 28–29, 206–7, 217 dimming of, 29, 59 hippocampus and, 101–2 as ordered sequences of patterns, 27–29, 54 redundancy of, 59 unexpected recall of, 31–32, 54, 68–69 working, 101 Menabrea, Luigi, 190 metacognition, 200, 201 metaphors, 14–15, 113–17, 176–77 Michelson, Albert, 18, 19, 36, 114 Michelson-Morley experiment, 19, 36, 114 microtubules, 206, 207, 208, 274 Miescher, Friedrich, 16 mind, 11 pattern recognition theory of (PRTM), 5–6, 8, 11, 34–74, 79, 80, 86, 92, 111, 172, 217 thought experiments on, 199–247 mind-body problem, 221 Minsky, Marvin, 62, 133–35, 134, 199, 228 MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, 134 MIT Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, 101 MobilEye, 159 modeling, complexity and, 37–38 Modha, Dharmendra, 128, 195, 271–72 momentum, 20–21 conservation of, 21–22 Money, John William, 118, 119 montane vole, 119 mood, regulation of, 106 Moore, Gordon, 251 Moore’s law, 251, 255, 268 moral intelligence, 201 moral systems, consciousness as basis of, 212–13 Moravec, Hans, 196 Morley, Edward, 18, 19, 36, 114 Moskovitz, Dustin, 156 motor cortex, 36, 99 motor nerves, 99 Mountcastle, Vernon, 36, 37, 94 Mozart, Leopold, 111 Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus, 111, 112 MRI (magnetic resonance imaging), 129 spatial resolution of, 262–65, 263, 309n MT (V5) visual cortex region, 83, 95 Muckli, Lars, 225 music, as universal to human culture, 62 mutations, simulated, 148 names, recalling, 32 National Institutes of Health, 129 natural selection, 76 geologic process as metaphor for, 14–15, 114, 177 see also evolution Nature, 94 nematode nervous system, simulation of, 124 neocortex, 3, 7, 77, 78 AI reverse-engineering of, see neocortex, digital bidirectional flow of information in, 85–86, 91 evolution of, 35–36 expansion of, through AI, 172, 266–72, 276 expansion of, through collaboration, 116 hierarchical order of, 41–53 learning process of, see learning linear organization of, 250 as metaphor machine, 113 neural leakage in, 150–51 old brain as modulated by, 93–94, 105, 108 one-dimensional representations of multidimensional data in, 53, 66, 91, 141–42 pattern recognition in, see pattern recognition pattern recognizers in, see pattern recognition modules plasticity of, see brain plasticity prediction by, 50–51, 52, 58, 60, 66–67, 250 PRTM as basic algorithm of, 6 pruning of unused connections in, 83, 90, 143, 174 redundancy in, 9, 224 regular grid structure of, 82–83, 84, 85, 129, 262 sensory input in, 58, 60 simultaneous processing of information in, 193 specific types of patterns associated with regions of, 86–87, 89–90, 91, 111, 152 structural simplicity of, 11 structural uniformity of, 36–37 structure of, 35–37, 38, 75–92 as survival mechanism, 79, 250 thalamus as gateway to, 100–101 total capacity of, 40, 280 total number of neurons in, 230 unconscious activity in, 228, 231, 233 unified model of, 24, 34–74 as unique to mammalian brain, 93, 286n universal processing algorithm of, 86, 88, 90–91, 152, 272 see also cerebral cortex neocortex, digital, 6–8, 41, 116–17, 121–78, 195 benefits of, 123–24, 247 bidirectional flow of information in, 173 as capable of being copied, 247 critical thinking module for, 176, 197 as extension of human brain, 172, 276 HHMMs in, 174–75 hierarchical structure of, 173 knowledge bases of, 177 learning in, 127–28, 175–76 metaphor search module in, 176–77 moral education of, 177–78 pattern redundancy in, 175 simultaneous searching in, 177 structure of, 172–78 virtual neural connections in, 173–74 neocortical columns, 36–37, 38, 90, 124–25 nervous systems, 2 neural circuits, unreliability of, 185 neural implants, 243, 245 neural nets, 131–35, 144, 155 algorithm for, 291n–97n feedforward, 134, 135 learning in, 132–33 neural processing: digital emulation of, 195–97 massive parallelism of, 192, 193, 195 speed of, 192, 195 neuromorphic chips, 194–95, 196 neuromuscular junction, 99 neurons, 2, 36, 38, 43, 80, 172 neurotransmitters, 105–7 new brain, see neocortex Newell, Allen, 181 New Kind of Science, A (Wolfram), 236, 239 Newton, Isaac, 94 Nietzsche, Friedrich, 117 nonbiological systems, as capable of being copied, 247 nondestructive imaging techniques, 127, 129, 264, 312n–13n nonmammals, reasoning by, 286n noradrenaline, 107 norepinephrine, 118 Notes from Underground (Dostoevsky), 199 Nuance Speech Technologies, 6–7, 108, 122, 152, 161, 162, 168 nucleus accumbens, 77, 105 Numenta, 156 NuPIC, 156 obsessive-compulsive disorder, 118 occipital lobe, 36 old brain, 63, 71, 90, 93–108 neocortex as modulator of, 93–94, 105, 108 sensory pathway in, 94–98 olfactory system, 100 Oluseun, Oluseyi, 204 OmniPage, 122 One Hundred Years of Solitude (García Márquez), 283n–85n On Intelligence (Hawkins and Blakeslee), 73, 156 On the Origin of Species (Darwin), 15–16 optical character recognition (OCR), 122 optic nerve, 95, 100 channels of, 94–95, 96 organisms, simulated, evolution of, 147–53 overfitting problem, 150 oxytocin, 119 pancreas, 37 panprotopsychism, 203, 213 Papert, Seymour, 134–35, 134 parameters, in pattern recognition: “God,” 147 importance, 42, 48–49, 60, 66, 67 size, 42, 49–50, 60, 61, 66, 67, 73–74, 91–92, 173 size variability, 42, 49–50, 67, 73–74, 91–92 Parker, Sean, 156 Parkinson’s disease, 243, 245 particle physics, see quantum mechanics Pascal, Blaise, 117 patch-clamp robotics, 125–26, 126 pattern recognition, 195 of abstract concepts, 58–59 as based on experience, 50, 90, 273–74 as basic unit of learning, 80–81 bidirectional flow of information in, 52, 58, 68 distortions and, 30 eye movement and, 73 as hierarchical, 33, 90, 138, 142 of images, 48 invariance and, see invariance, in pattern recognition learning as simultaneous with, 63 list combining in, 60–61 in neocortex, see pattern recognition modules redundancy in, 39–40, 57, 60, 64, 185 pattern recognition modules, 35–41, 42, 90, 198 autoassociation in, 60–61 axons of, 42, 43, 66, 67, 113, 173 bidirectional flow of information to and from thalamus, 100–101 dendrites of, 42, 43, 66, 67 digital, 172–73, 175, 195 expectation (excitatory) signals in, 42, 52, 54, 60, 67, 73, 85, 91, 100, 112, 173, 175, 196–97 genetically determined structure of, 80 “God parameter” in, 147 importance parameters in, 42, 48–49, 60, 66, 67 inhibitory signals in, 42, 52–53, 67, 85, 91, 100, 173 input in, 41–42, 42, 53–59 love and, 119–20 neural connections between, 90 as neuronal assemblies, 80–81 one-dimensional representation of multidimensional data in, 53, 66, 91, 141–42 prediction by, 50–51, 52, 58, 60, 66–67 redundancy of, 42, 43, 48, 91 sequential processing of information by, 266 simultaneous firings of, 57–58, 57, 146 size parameters in, 42, 49–50, 60, 61, 66, 67, 73–74, 91–92, 173 size variability parameters in, 42, 67, 73–74, 91–92, 173 of sounds, 48 thresholds of, 48, 52–53, 60, 66, 67, 111–12, 173 total number of, 38, 40, 41, 113, 123, 280 universal algorithm of, 111, 275 pattern recognition theory of mind (PRTM), 5–6, 8, 11, 34–74, 79, 80, 86, 92, 111, 172, 217 patterns: hierarchical ordering of, 41–53 higher-level patterns attached to, 43, 45, 66, 67 input in, 41, 42, 44, 66, 67 learning of, 63–64, 90 name of, 42–43 output of, 42, 44, 66, 67 redundancy and, 64 specific areas of neocortex associated with, 86–87, 89–90, 91, 111, 152 storing of, 64–65 structure of, 41–53 Patterns, Inc., 156 Pavlov, Ivan Petrovich, 216 Penrose, Roger, 207–8, 274 perceptions, as influenced by expectations and interpretations, 31 perceptrons, 131–35 Perceptrons (Minsky and Papert), 134–35, 134 phenylethylamine, 118 Philosophical Investigations (Wittgenstein), 221 phonemes, 61, 135, 137, 146, 152 photons, 20–21 physics, 37 computational capacity and, 281, 316n–19n laws of, 37, 267 standard model of, 2 see also quantum mechanics Pinker, Steven, 76–77, 278 pituitary gland, 77 Plato, 212, 221, 231 pleasure, in old and new brains, 104–8 Poggio, Tomaso, 85, 159 posterior ventromedial nucleus (VMpo), 99–100, 99 prairie vole, 119 predictable outcomes, determined outcomes vs., 26, 239 President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, 269 price/performance, of computation, 4–5, 250–51, 257, 257, 267–68, 301n–3n Principia Mathematica (Russell and Whitehead), 181 probability fields, 218–19, 235–36 professional knowledge, 39–40 proteins, reverse-engineering of, 4–5 qualia, 203–5, 210, 211 quality of life, perception of, 277–78 quantum computing, 207–9, 274 quantum mechanics, 218–19 observation in, 218–19, 235–36 randomness vs. determinism in, 236 Quinlan, Karen Ann, 101 Ramachandran, Vilayanur Subramanian “Rama,” 230 random access memory: growth in, 259, 260, 301n–3n, 306n–7n three-dimensional, 268 randomness, determinism and, 236 rationalization, see confabulation reality, hierarchical nature of, 4, 56, 90, 94, 172 recursion, 3, 7–8, 56, 65, 91, 153, 156, 177, 188 “Red” (Oluseum), 204 redundancy, 9, 39–40, 64, 184, 185, 197, 224 in genome, 271, 314n, 315n of memories, 59 of pattern recognition modules, 42, 43, 48, 91 thinking and, 57 religious ecstacy, 118 “Report to the President and Congress, Designing a Digital Future” (President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology), 269 retina, 95 reverse-engineering: of biological systems, 4–5 of human brain, see brain, human, computer emulation of; neocortex, digital Rosenblatt, Frank, 131, 133, 134, 135, 191 Roska, Boton, 94 Rothblatt, Martine, 278 routine tasks, as series of hierarchical steps, 32–33 Rowling, J.

The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is: A History, a Philosophy, a Warning

by

Justin E. H. Smith

Published 22 Mar 2022

Going far beyond what Menabrea himself had acknowledged of the debt of Babbage’s Analytical Engine to Jacquard’s loom, she explicitly claims that the engine really is just another sort of weaving machine: “The distinctive character of the Analytical Engine,” she writes, “is the introduction into it of the principle which Jacquard devised for regulating, by means of punched cards, the most complicated patterns in the fabrication of brocaded stuffs … We may say most aptly that the Analytical Engine weaves algebraical patterns just as the Jacquard-loom weaves flowers and leaves.”20 Lovelace believes that as a result of the use of the punched cards, the Analytical Engine is of a wholly different character than the Difference Engine that preceded it, and indeed than such earlier devices as the Leibnizian stepped reckoner or the Pascalian Pascaline.

…

It seems that even when we move away from the poetic invocations of weaving in Marcus Aurelius or in the Upanishads and in the direction of the concrete facts about punched-card technology, to dwell for too long on what the loom and the analytical engine have in common is to begin to make the literal metaphorical again. The Jacquard loom might be literally a kind of computer, but the Analytical Engine is not literally a loom, and it does not literally weave data or algebraic patterns. To hold these two sorts of thing in relation to one another, to turn around them as it were and to see the one through the other in succession, the loom through the engine and the engine through the loom, is to move between two registers of language that philosophy and science ordinarily seek to keep separate.

The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History

by

Kassia St Clair

Published 3 Oct 2018

In 1801 Joseph Marie Jacquard invented a loom that made it possible to mass-produce textiles with complex woven patterns, something that previously had taken a great deal of skill, time and expertise to produce. His ‘Jacquard Loom’ was controlled, or programmed, by pieces of card marked with a series of holes that determined the pattern. Much later, these ingenious, hole-punched cards paved the way for another invention: computing. An American engineer repurposed the punched-card system to help record census data. His firm eventually became part of International Business Machines, latterly known as IBM.9 The Jacquard Loom is one of the more obvious links between technology and textiles, but examples can be found much further back.

…

Fulling A method of strengthening woollen fabric by trampling it when wet so that the fibres of the woven cloth begin to felt, or mat together. Fustian Coarse cloth made of cotton or flax. Now more commonly a thick, twilled cotton cloth usually dyed a dull, dark colour. H Heckling To split and straighten the fibres of hemp or flax for spinning. Holland Linen fabric from the province of Holland in the Netherlands. J Jacquard loom A loom fitted with a mechanism to control the weaving of figured fabrics. This mechanism was invented by Joseph Marie Jacquard from Lyons in France. Jersey Knitted goods from Jersey, especially a kind of tunic. Later used to denote fine knitted fabrics. L Loom A machine or implement on which yarn or thread is woven.

In Our Own Image: Savior or Destroyer? The History and Future of Artificial Intelligence

by

George Zarkadakis

Published 7 Mar 2016

The Analytical Engine Singularity During his studies of manufacturing in England, Babbage had noticed the significant innovations in the textile industry. In 1801, the Jacquard loom8 used punched cards in order to automate the mechanical weaving of very complex patterns. In the separation of the mechanical part of the machine from the patterns to be woven, the Jacquard loom foretold the computing dichotomy between hardware and software; i.e. between the physical medium that executes the processing and the informational ‘pattern’ that is either the set of instructions for the processing, or the object of processing, or both. Furthermore, punched cards could be stitched together to form long tapes of patterns that were input and ‘executed’ by the looms.

…

When finite differences between the parameters of a difference equation become infinitesimal, then the equations are called ‘differential’ and are fundamental to calculus. 7Difference Engine No. 2 was reconstructed under Doron Swade, the then Curator of Computing at the London Science Museum. Reconstruction took place between 1989 and 1991, in order to celebrate the two-hundredth anniversary of Babbage’s birth. In 2000, the printer, which Babbage originally designed for the difference engine, was also completed. 8The Jacquard Loom was invented by French weaver and merchant Joseph Marie Charles, nicknamed Jacquard. It was based on an earlier invention by the master of automata, Jacques Vaucanson – of mechanical duck fame. 9The next ‘Turing-complete’ machine after the Analytical Engine would be ENIAC, which was constructed in 1946. 10Ada Lovelace called her notes simply ‘Notes’. 11The Bernoulli numbers are a sequence of rational numbers with many applications in engineering, and of great interest to mathematicians.

…

A. 61–2, 68 Hofstadter, Douglas 186–8 Hohlenstein Stadel lion-man statuette 3–5, 19–20 holistic approach to knowledge 174–5 holistic scientific methods 41–2 Holocene period 10 Holy Scripture, authority of 113–14 homeostasis 173 Homo erectus 6–7, 8, 10 Homo habilis 6, 12 Homo heidelbergensis 7 Homo sapiens archaic species 7, 8, 10 emergence of modern humans 8 Homo neanderthalensis (Neanderthals) 4, 7–8, 9–10 Homo sapiens sapiens 9–10 human ancestors aesthetic practices 9 archaic Homo sapiens 7, 8, 10 arrival in Europe 3–5 australopithecines 5, 6, 22 changes in the Upper Palaeolithic Age 9–10, 11 common ancestor with chimpanzees 5 emergence of art in Europe 3–5 emergence of modern humans 8 exodus from Africa 3–4, 6–7, 8–9 Homo erectus 6–7, 8, 10 Homo habilis 6, 12 Homo heidelbergensis 7 Homo sapiens 7, 8, 10 Homo sapiens sapiens 9–10 in Africa 5–7 Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) 4, 7–8, 9–10 Human Brain Project (HBP) xiv–xvi, 164–5, 287 see also brain (human) human culture, approaches to understanding 74–9 human replicas, disturbing feelings caused by 66–73 humanity becoming like machines (cyborgs) 79–85 future of 304–17 Hume, David 139–40 humors theory of life 31–4 humour, and theory of mind 54 Humphrey, Nicholas 11 hunter-gatherer view of the natural world 20–2 hydraulic and pneumatic automata 32–6 IBM (International Business Machines) 230, 263, 264 Ice Age Europe 4, 10, 21–2 iconoclasm 67 idealism versus materialism 92–4 identity theory 144–5 imagined world of the spirits 22–3, 25, 27 inanimate objects, projection of theory of mind 15–18 Incompleteness Theorem (Gödel) 180, 186, 206–9, 211–16 inductive logic 196, 197 information disembodiment of 146–52 significance of context 151–2 the mind as 123–5 information age 232–4 information theory 147–52 Ingold, Tim 20 intelligence, definitions of 48–9, 52 intelligent machines as objects of love 48–59 Internet brain metaphor 43 collection and manipulation of users’ data 250–3 origins of 238 potential for sentience 214–15 Internet of things 251–3 intuition 200, 211 Iron Man (film) 82 Ishiguro, Hiroshi 72 Islam 102 Jacquard loom 225 James, William 162 Johnson, Samuel 140 Kasparov, Garry 263 Kauffman, Stuart 295 Kempelen, Wolfgang von 37 Kline, Nathan 79 Koch, Christof 167–8 Krauss, Lawrence 244–5 Krugman, Paul 269 Kubrick, Stanley 56, 257 Kuhn, Thomas 29, 75 Kurzweil, Ray 126, 270–1 Lang, Fritz 50 language and genesis of the modern mind 13–15 and human relationship with objects 15–18 evolution of 13–15 naming of objects 16–17 LeCun, Yann 255 Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm 116–17, 218–20 Lettvin, Jerry 293 liberty, end of 313–17 life algorithms of 292–6 origins of 181–3 Life in the Bush of Ghosts (Tutuola) 19 linguistics, descriptions of reality 75 lion-man statuette of Stadel cave 3–5, 19–20 Llull, Ramon (Doctor Illuminatus) 218 Locke, John 139 locked-in syndrome 307 logic x–xi, 195–202 logical substitution method 180, 183, 186 Lokapannatti (early Buddhist story) 34 London forces 107 love conscious artefacts as objects of 48–59 human need for 55–6 human relationships with androids 53–9 Lovelace, Ada 62, 226–7, 228 Luddites 268 Machine Intelligence Research Institute 58–9 machine metaphor for life 36–8 Magdalenian period 21 magnetoencephalography (MEG) 159–60, 161 Maillardet, Henri 218 Marconi, Guglielmo 239 Maria (robot in Metropolis) 50, 51 Marlowe, Christopher 63 Mars colonisation 291 Marx, Groucho 205 materialism versus idealism 92–4 mathematical dematerialisation view 92 mathematical foundations of the universe 103–6 mathematical reflexivity 186–7 mathematics 31 formal logical systems 200–11 views on the nature of 136 Maturana, Humberto 294 McCarthy, John 256, 307 McCorduck, Pamela 45, 67 McCulloch, Warren S. 36, 175, 176–8, 256, 293 Mead, Margaret 175 mechanical metaphor for life 36–8 mechanical Turk 37 medicine, development of 31–2 meditation 157 memristors 286–7 Menabrea, Luigi 226, 227 Mesmer, Franz Anton 40 mesmerism 40 Mesopotamian civilisations 30 metacognition 184 metamathematics 202, 205, 207 metaphors confusing with the actual 44–5 for life and the mind 28–47 in general-purpose language 75 misunderstanding caused by 308–13 Metropolis (1927 film) 50, 51 Middle Palaeolithic 6 Miller, George 154, 155 Milton, John 1 mind altered states 110, 111 as pure information 123–5 aspects of 85–7 debate over the nature of 91–4 disembodiment of 42 empirical approach 143–6 quantum hypothesis 106–9 scientific theory of 152–3 search for a definition 189–91 self-awareness 86–7 separate from the body 110–15 view of Aristotole 137–8 mind-body problem 32, 114–19, 129–31 Minsky, Marvin 178, 256 modern mind big bang of 10, 12–15 birth of 10–15 impacts of the evolution of language 13–15 monads 117, 119 monism versus dualism 92–3 Moore’s Law 244–5, 263, 270–1, 287 moral decision-making 277–8 Moravec paradox 275–6 Morris, Ian 222 Morse, Samuel 42 mud metaphor for life 29–31, 45 My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (music album) 19 Nabokov, Vladimir 167 Nagel, Thomas 120, 121 Nariokotome boy 7 narratives 18–27, 75 see also metaphor Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) 4, 7–8, 9–10 Negroponte, Nicholas 243–4 neopositivism 141 neural machines 282–7 neural networks theory 36 neural synapses, functioning of 117–19 neuristors 286–7 neurodegenerative diseases xiii–xiv, 163–4 Neuromancer (Gibson) 36 neuromorphic computer archtectures 286–7 neurons, McCulloch and Pitts model 177–8 neuroscience 158, 306–8 Newton, Isaac 38, 103 Nike’s Fuel Band 81 noetic machines (Darwins) 284 nootropic drugs 81 Nouvelle AI concept 288 Offray de La Mettrie, Julien 37 Ogawa, Seiji 158–9 Omo industrial complex 6 On the Origin of Species (Darwin) 289–90 ‘ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny’ concept 10 Otlet, Paul 239–40 out-of-body experiences 110–11 Ovid 49, 64 Paley, William 289 panpsychism 92, 117, 252 paradigm shifts 75 in the concept of life 29–47 Pascal, Blaise 219–20 Penrose, Roger 106–9, 117, 211–12, 214 Pert, Candace B. 170 physics, gaps in the Standard Model 105 Piketty, Thomas 267, 269 pineal gland 115–16 Pinker, Steven 13, 275 Pinocchio story 56 Pitts, Walter 36, 177–8, 256, 293 Plato 134, 143, 152, 176, 189, 305 central role of mathematics 103–6 idea of reality 78, 83 influence of 95–106 notion of philosopher-kings 98–9 separation of body and mind 112 The Republic 97–101, 309, 310 theory of forms 99–101, 104, 106 Platonism 101–2, 135–7, 139, 142, 146, 147, 182, 189, 190, 242–3, 296 Pleistocene epoch 7 Poe, Edgar Allan 79 Polidori, John William 60, 62 Popov, Alexander 239 Popper, Karl 98 Porter, Rodney 282 posthuman existence 147 postmodernism 208 post-structuralist philosophers 75–9 precautionary principle 64–5 predicate logic 198–200, 206 Principia Mathematica 205–6, 207 Prometheus 29–30, 63–4 psychoanalysis 50 psychons 118, 119 Pygmalion narrative 49–52 qualia of consciousness 120–3, 157 Quantified Self movement 81–2 quantum hypothesis for consciousness 106–9 quantum tunnelling 118–19 Ramachandran, Vilayanur 70 rationalism 116 Reagan, President Ronald 237 reality, impact of acquisition of language 15–18 reductionism 41–2, 104–5, 121, 184 reflexivity 183–4, 186–9 religions condemnation of human replicas 67 seeds of 22–3, 25–6 Renaissance 34, 103, 139, 218 RepRap machines 290 res cogitans (mental substance) 38, 113–14 res extensa (corporeal substance) 38, 113–14 resurrection beliefs 126–7 RoboCop 80 robot swarm experiments 287–8 robots human attitudes towards 50–1 rebellion against humans 53, 57–9 self-replication 289–92 see also androids Rochester, Nathaniel 256 Romans 31 Rubenstein, Michael 287–8, 291 Russell, Bertrand viii, 92, 198, 204, 205–6, 207, 208, 215 Russell, Stuart 270 Sagan, Carl 133 Saygin, Ayse Pinar 69 science as a cultural product 75–9 influence of Aristotle 134–8 influence of Descartes 113–19 influence of Plato see Plato scientific method 102–5, 121 scientific paradigms 75 scientific reasoning, as unnatural to us 133–4, 137 scientific theory, definition 166, 196 Scott, Ridley 53 Searle, John, Chinese Room experiment 52, 71 Second Commandment (Bible) 67 second machine age, impact of AI 266–9 Second World War 234–6 self-awareness 16, 86–7, 157, 215–16, 273–5 self-driving vehicles 263–4 self-organisation in cybernetic systems 273–4 in living things 292 self-referencing 186–9, 215–16 see also reflexivity self-referencing paradoxes 204–6 self-replicating machines/systems 179–82, 289–92 sensorimotor skills, deficiency in AI 275–6 servers, dependence on 245–9 Shannon, Claude 147–52, 154, 176, 230–1, 256 Shaw, George Bernard Shaw 49–50 Shelley, Mary, Frankenstein 40, 60–5, 165 Shelley, Percy Bysshe 60, 62, 63–4 Shickard, Wilhem 219 Silvester II, Pope 35 Simmons, Dan 160 simulated universe concept 127–9 smart drugs 81 Snow, C.

When Things Start to Think

by

Neil A. Gershenfeld

Published 15 Feb 1999

Hist. Nat. Genev., Acad. Reg. Monac., Hafn., Massi!., et Divion., Socius. Acad. Imp. et Reg. Petrop., Neap., Brux., Patav., Georg. Floren., Lyncei. Rom., Mut., Philomath. Paris, Soc. Corr., etc." No hidden compartments for him. Babbage set out to make the first digital computer, inspired by the Jacquard looms of his day. The patterns woven into fabrics by these giant machines were programmed by holes punched in cards that were fed to them. Babbage realized that the instructions could just as well represent the sequence of instructions needed to perform a mathematical calculation. His first machine was the Difference Engine, intended to evaluate quantities such as the trigonometric functions used by mariners to interpret their sextant readings.

…

Babbage and his accomplice, Lady Ada Lovelace, realized that an engine could just as well manipulate the symbols of a mathematical formula. Its mechanism could embody the rules for, say, calculus and punch out the result of a derivation. As Lady Lovelace put it, "the Analytical Engine weaves algebraical patterns just as the Jacquard Loom weaves flowers and leaves." Although Babbage's designs were correct, following them went well beyond the technological means of his day. But they had an enormous impact by demonstrating that a mechanical system could perform what appear to be intelligent operations. Darwin was most impressed by the complex behavior that Babbage's engines could display, helping steer him to the recognition that biological organization might have a mechanistic explanation.

How We Got to Now: Six Innovations That Made the Modern World

by

Steven Johnson

Published 28 Sep 2014

Events that loom large in human accounts—the European conquest of the Americas, the fall of the Roman Empire, the Magna Carta—would be footnotes from the robot’s perspective. Other events that seem marginal to traditional history—the toy automatons that pretended to play chess in the eighteenth century, the Jacquard loom that inspired the punch cards of early computing—would be watershed moments to the robot historian, turning points that trace a direct line to the present. “While a human historian might try to understand the way people assembled clockworks, motors and other physical contraptions,” De Landa explained, “a robot historian would likely place a stronger emphasis on the way these machines affected human evolution.

…