Johannes Kepler

description: German mathematician and astronomer (1571–1630)

150 results

The Invention of Science: A New History of the Scientific Revolution

by David Wootton · 7 Dec 2015 · 1,197pp · 304,245 words

’s Starry Messenger, with its account of the moon as having mountains and valleys, Donne would surely have responded exactly as the great German astronomer Johannes Kepler did that spring when he read one of the first copies to arrive in Germany – he saw a remarkable vindication of Bruno’s perverse theory

…

a few months after Galileo discovered what we call the moons of Jupiter (Galileo does not call them moons, but first stars and then planets), Johannes Kepler invented a new word for these new objects: they were ‘satellites’.lviii Thus historians who take language seriously need to search out the emergence of

…

nauseous, that it perfectly turned my stomach. – Jonathan Swift, ‘A Voyage to Brobdingnag’, Gulliver’s Travels (1726) § 1 One day towards the beginning of 1610 Johannes Kepler was walking across a bridge in Prague when a few snowflakes settled upon his coat.1 He was feeling guilty, because he had failed to

…

the word ‘fact’ when describing the activities of people who did not yet have the word). On the night of 19 February 1604, in Prague, Johannes Kepler was out measuring the position of Mars in the sky with a metal instrument called a quadrant.19 The type of measurement he was trying

…

Astronomy 16 (1985): 37–42. ———. ‘From Copernicus to Kepler: Heliocentrism as Model and as Reality’. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 117 (1973): 513–22. ———. ‘Johannes Kepler’. In The General History of Astronomy. 4 vols. 2A: Planetary Astronomy from the Renaissance to the Rise of Astrophysics. Ed. R Taton and C Wilson

…

Astronomy (1992), 210–11. 20. Goldstein & Hon, ‘Kepler’s Move from Orbs to Orbits’ (2005). 21. Kepler, New Astronomy (1992), 405, 410–16. 22. Gingerich, ‘Johannes Kepler’ (1989), 63. 23. Gingerich, ‘Circles of the Gods’ (1994), 23. 24. Shapin & Schaffer, Leviathan and the Air-pump (1985), 22–79. 25. Westman, The Copernican

…

parte delle theoriche (1558), 29r–30v, which argues that public opinion is to be trusted in questions of morality but not natural philosophy. 30. Gingerich, ‘Johannes Kepler’ (1989), 63. 31. Duhem, To Save the Phenomena (1969). 32. Lehoux, What Did the Romans Know? (2012), 136–54, 209–17. 33. Lehoux, What Did

…

(Denis Papin) 504–10 controversy and change 245–7 Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds (Bernard de Fontenelle) 231 Conversations with Galileo’s Starry Messenger (Johannes Kepler) 8–9, 302 Copernican Revolution, The (Thomas Kuhn) 18, 145, 246n, 516 Copernicus, Nicolaus 137–59 see also On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres

…

–9 Corvinus, Lawrence 139 Cosimo II (de’ Medici) 214 Cosmographiæ introductio, The (Martin Waldseemüller) 59n, 124 Cosmographic Book (Peter Apian) 201, 202 Cosmographic Mystery, The (Johannes Kepler) 212 Cotes, Roger 322, 375 Coulanges, Fustel de 550n Course of Experimental Philosophy, A (J. T. Desaguliers) 309, 417, 501 Courtier (Baldassare Castiglione) 176 Cowell

…

On the Revolutions 139 Tycho Brahe’s nova 192 Wilkins and 233 Diodorus Siculus 259 Diogenes Laertius 259 Dionysius (the Areopagite) 436n Diophantus 187 Dioptrice (Johannes Kepler) 224 Discourse Concerning a New World and Another Planet (John Wilkins) 231, 233 Discourse Concerning Prodigies, A (John Spencer) 469 Discourse of Free Thinking (Anthony

…

, The Reginald Scot) 355 Displaying of Supposed Witchcraft, The (John Webster) 450 Disputationes (Samuel Parker) 433 dissection 183 see also anatomy Dissertatio cum Nuncio siderio (Johannes Kepler) 220 Ditton, Humphrey 475 Diverse Problems and Inventions (Tartaglia) 203 DNA 16, 61, 528 Doctor Faustus (Christopher Marlowe) 155 Doll, Richard 564 domes 77 Domesday

…

265 necessitarians and 376n random swerve of creation 461 Renaissance understanding of 8n 17th century embraces 10 vacuums 77n epicycles 413, 570 Epitome astronomiae Copernicanae (Johannes Kepler) 130n, 152n, 228, 252 eponymy 98–102 equants 144–5, 152 equator, the 72–3, 110, 120 Erasistratus 67 Erasmus 451 Errors of the Crowd

…

Morland, John 503 Moses 354 Mosnier, M. 311 Motte, Andrew 396n Mundus novus (attrib. Amerigo Vespucci) 121 Muslims 66, 113 see also Islam Mysterium cosmographicum (Johannes Kepler) 213 Mystery of Jesuitisme (Blaise Pascal) 293 Napier, John 90, 94, 416 Napoleon Bonaparte 149n, 480, 549 Natural and Political Observations (John Graunt) 261 Natural

…

–3 see also Dutch networks 340–1, 348 New . . . (as title for various publications) 36 New Almagest (Giovanni Alberti Riccioli) 224, 227, 305 New Astronomy (Johannes Kepler) 24, 265, 305 New Atlantis (Francis Bacon) 103, 341 New Digester, The (Denis Papin) 504 New Discoveries (Johannes Stradanus) 56 New Experiments (Robert Boyle) 294

…

, 337, 344, 392, 516 New Science (Tartaglia) 203, 204 New Star (Tycho Brahe) 14 New Star (Johannes Kepler) 263, 264, 265 New Theory of the Earth, The (William Whiston) 396, 467, 474 New Treatise of Natural Philosophy (Robert Midgeley) 279 New Treatise Proving

…

205 not the beginning of modern science 159 quotation from 55 terraqueous globe 142 Tycho Brahe’s work and 194 On the Six-cornered Snowflake (Johannes Kepler) 212 On the Theory of Coinage (Nicolaus Copernicus) 206 On the Universe (William Gilbert) 158 ‘On Understanding Science’ (James B. Conant) 544 one sphere/two

…

32 Restoration and 424 Sprat defends 415 Torricellian network and 341 Wilkins 231 Wotton and 454 Rudbeck, Olof 96 Rudolph II, Emperor 278 Rudolphine tables (Johannes Kepler) 306, 307 rules of the game 64 see also games Russell, Bertrand 43, 47n Rutherford, Ernest 15, 17 Ruysch, John 138 Sabra, Abdelhamid 319n Sacred

More Perfect Heaven: How Copernicus Revolutionised the Cosmos

by Dava Sobel · 1 Sep 2011 · 271pp · 68,440 words

here. The message is a moral one, concerning something self-evident and seen by all eyes but seldom pondered. Solomon therefore urges us to ponder. —JOHANNES KEPLER, Astronomia nova, 1609 (TRANSLATED FROM THE LATIN BY WILLIAM H. DONAHUE) Chapter 7 The First Account It is also clearer than sunlight that the sphere

…

intellect, the Copernican theory, which I in my innermost have recognized as true, and whose loveliness fills me with unbelievable rapture when I contemplate it. —JOHANNES KEPLER, Epitome of Copernican Astronomy, 1617–21 Content with thePrutenic Tables, European astronomers took Copernicus at Osiander’s cautious word for the remainder of the sixteenth

…

century—with two monumental exceptions. Between them, the flamboyant Tycho Brahe and the studious, passionately reverent Johannes Kepler carried Copernicus’s work to completion. The Danish Tycho was literally star-struck in 1559, during his thirteenth summer, when a lunar eclipse illuminated the

…

gave him his choice of castles and put him to work prognosticating affairs of state. The move to Prague also put Tycho in proximity to Johannes Kepler, thereby facilitating their fateful collaboration. Kepler, not yet well known to most astronomers and living in modest circumstances, could never have afforded a visit to

…

with Tycho’s heirs over access to the data, did Kepler finally take possession of Tycho’s treasure and lay it at Copernicus’s feet. Johannes Kepler, imperial mathematician to Rudolf II. “I build my whole astronomy upon Copernicus’s hypotheses concerning the world,” Kepler proclaimed in his Epitome of Copernican Astronomy

…

notes repeat in numerous volumes, demonstrating the influence of certain teachers. Among the most extensively and tellingly annotated copies is the one that belonged to Johannes Kepler, now held at the Universitätsbibliothek in Leipzig. It is a first edition, first owned by Jerome Schreiber of Nuremberg, who received it as a gift

…

geo-heliocentric system. 1595 Bartholomew Pitiscus, Calvinist theologian and mathematician, composes his Trigonometry, which title establishes the enduring term for the science of triangles. 1596 Johannes Kepler publishes his Mysterium cosmographicum. Valentin Otto publishes Rheticus’s work as Opus palatinum, full of errors. 1604 Kepler observes a nova. 1609 Galileo observes the

…

Bookstore, 1939. Danielson, Dennis. The First Copernican: Georg Joachim Rheticus and the Rise of the Copernican Revolution. New York: Walker, 2006. Donahue, William H., trans. Johannes Kepler’s Astronomia nova (1609). Santa Fe: Green Lion, 2004. Drake, Stillman. Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo. Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor, 1957. ———. Galileo’s Dialogue

…

’ Heliocentric Providence: A Study Concerning the Astrology, Astronomy of the Sixteenth Century.” Doctoral dissertation, University of Heidelberg, 2001. Kremer, Richard L., and Jaroslaw Wlodarczyk, eds. Johannes Kepler: From Tübingen to Zagan. Warsaw: Polish Academy of Sciences, 2009. Studia Copernicana 42, in English. Kuhn, Tomas S. The Copernican Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

…

Telescope. London: British Museum, 1996. Wallis, Charles Glenn, trans. Nicolaus Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres. Annapolis: St. John’s Bookstore, 1939. ———. Johannes Kepler’s Epitome of Copernican Astronomy and Harmonies of the World. Annapolis: St. John’s Bookstore, 1939. Whitfield, Peter. Astrology: A History. New York: Abrams, 2001

Life Is Simple: How Occam's Razor Set Science Free and Shapes the Universe

by Johnjoe McFadden · 27 Sep 2021

day of 24 May 1543, his death, it is said, hastened on reading the infamous preface. For many years its author remained unknown. It was Johannes Kepler who later uncovered the truth that it had been written by Andreas Osiander. The publication of On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Orbs is often

…

marked not only the building of Brahe’s observatory but also the birth of the astronomer who would finally make sense of the celestial confusion. Johannes Kepler was born (when Brahe was twenty-five) in the small town of Weil der Stadt in Swabia, south-west Germany. His father was a mercenary

…

Aetherial World, published at Uraniborg in 1588. Thereafter, it became a competitor to both the Copernican and Ptolemaic systems. The mystical cosmos By the time Johannes Kepler arrived in Tübingen, in 1589, astronomers had been struggling for two decades to incorporate Tycho’s new star and supralunar comet into the prevailing Ptolemaic

…

insistence on the separation of science and theology, irrespective of what the theologians taught. The publication of his Mysterium not only brought the name of Johannes Kepler to the attention of the European astronomical community, but it also provided Kepler with a degree of marital capital and, in 1597, when he was

…

residence in Benátky Castle in Bohemia, about thirty miles outside Prague, where he set up his observatory. Later that year he received the letter from Johannes Kepler with the copy of Mysterium Cosmographicum. By this time, although the Dane continued to make astronomical observations, his ambitions had shifted towards proving his geoheliocentric

…

of the truth of heliocentricity. Thereafter, even astrologers used Kepler’s laws to predict the motions of the heavens. At the age of fifty-eight, Johannes Kepler fell ill and died on 15 November 1630 in the German city of Regensburg. His laws remain his most lasting legacy and one of the

…

1592, he obtained a position at the more prestigious University of Padua, where he lectured on mathematics, mechanics and astronomy. In 1597, he wrote to Johannes Kepler, who had only just nailed his own reputation to the mast of the Copernican system with the publication, in the previous year, of his Mysterium

…

appears to have been entirely based on trial and error. It wasn’t until 1611 that the principle of how telescopes worked was revealed by Johannes Kepler in his short book Dioptrice. By 1609, Galileo had sufficiently impressed the Doge of Venice with his improved telescope for his appointment at the University

…

enthusiasm for astronomy and a determination to help solve the outstanding puzzles of planetary motion. First among these was the shape of the planetary orbits. Johannes Kepler, who had died fifty-four years earlier, had left to posterity his three planetary laws and elliptical orbits. Kepler’s laws worked, but neither Kepler

…

Nominalism (Harvard University Press, 1963). 4. Methuen, C., Kepler’s Tübingen: Stimulus to a Theological Mathematics (Ashgate, 1998). 5. Field, J. V., ‘A Lutheran Astrologer: Johannes Kepler’, Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 31 (1984). 6. Spielvogel, J. J., Western Civilization, 467 (Cengage Learning, 2014). 7. Bialas, V

…

., Johannes Kepler, vol. 566 (CH Beck, 2004). 8. Chandrasekhar, S., The Pursuit of Science, 410–20 (Minerva, 1984). 9. Kepler, J., The Harmony of the World, vol.

Cosmos

by Carl Sagan · 1 Jan 1980 · 404pp · 131,034 words

are presented out of historical order. For example, the ideas of the ancient Greek scientists are presented in Chapter 7, well after the discussion of Johannes Kepler in Chapter 3. But I believe an appreciation of the Greeks can best be provided after we see what they barely missed achieving. Because science

…

can be produced by slicing through a cone at various angles. Eighteen centuries later, the writings of Apellecios on comic sections would be employed by Johannes Kepler in understanding for the first time the movement of the planets. CHAPTER II ONE VOICE IN THE COSMIC FUGUE Probably all the organic beings which

…

so great, and the treasures hidden in the heavens so rich, precisely in order that the human mind shall never be lacking in fresh nourishment. —Johannes Kepler, Mysterium Cosmographicum If we lived on a planet where nothing ever changed, there would be little to do. There would be nothing to figure out

…

seems steady, solid, immobile, while we can see the heavenly bodies rising and setting each day. Every culture has leaped to the geocentric hypothesis. As Johannes Kepler wrote, “It is therefore impossible that reason not previously instructed should imagine anything other than that the Earth is a kind of vast house with

…

phenomena of Nature might be the laws of physics. But the brave and lonely struggle of this man was to ignite the modern scientific revolution. Johannes Kepler was born in Germany in 1571 and sent as a boy to the Protestant seminary school in the provincial town of Maulbronn to be educated

…

a marker were to be erected today, it might read, in homage to his scientific courage: “He preferred the hard truth to his dearest illusions.” Johannes Kepler believed that there would one day be “celestial ships with sails adapted to the winds of heaven” navigating the sky, filled with explorers “who would

…

vastness of space the three laws of planetary motion that Kepler uncovered during a lifetime of personal travail and ecstatic discovery. The lifelong quest of Johannes Kepler, to understand the motions of the planets, to seek a harmony in the heavens, culminated thirty-six years after his death, in the work of

…

of the Earth, were also deemed “perfect.” The pros and cons of the Pythagorean tradition can be seen clearly in the life’s work of Johannes Kepler (Chapter 3). The Pythagorean idea of a perfect and mystical world, unseen by the senses, was readily accepted by the early Christians and was an

…

, after the event of 1054, there was a supernova observed in 1572, and described by Tycho Brahe, and another, just after, in 1604, described by Johannes Kepler,† Unhappily, no supernova explosions have been observed in our Galaxy since the invention of the telescope, and astronomers have been chafing at the bit for

…

radio message to get from there to here. If we had initiated the dialogue, it would be as if the question had been asked by Johannes Kepler and the answer received by us. Especially because we, new to radio astronomy, must be comparatively backward, and the transmitting civilization advanced, it makes more

…

squares for faces. A simple polyhedron, or regular solid, is one with no holes in it. Fundamental to the work of the Pythagoreans and of Johannes Kepler was the fact that there can be 5 and only 5 regular solids. The easiest proof comes from a relationship discovered much later by Descartes

Infinite Powers: How Calculus Reveals the Secrets of the Universe

by Steven Strogatz · 31 Mar 2019 · 407pp · 116,726 words

music of the spheres. Ever since then, many of history’s greatest mathematicians and scientists have come down with cases of Pythagorean fever. The astronomer Johannes Kepler had it bad. So did the physicist Paul Dirac. As we’ll see, it drove them to seek, and to dream, and to long for

…

descent of a ball rolling down a ramp, and charted the stately procession of planets across the sky. The patterns they found enraptured them—indeed, Johannes Kepler fell into a state of self-described “sacred frenzy” when he found his laws of planetary motion—because those patterns seemed to be signs of

…

. He timed pendulums swinging back and forth and rolled balls down gentle ramps and found marvelous regularities in both. Meanwhile, a young German mathematician named Johannes Kepler studied how the planets wandered across the sky. Both men were fascinated by patterns in their data and sensed the presence of something far deeper

…

in his own era but in our own. Kepler and the Mystery of Planetary Motion What Galileo did for the motion of objects on Earth, Johannes Kepler did for the motion of the planets in the heavens. He solved the ancient riddle of planetary motion and fulfilled the Pythagorean dream by showing

…

with geometry, both sacred and profane, verged on the irrational. But his fervor made him who he was. As the writer Arthur Koestler astutely observed, “Johannes Kepler became enamored with the Pythagorean dream, and on this foundation of fantasy, by methods of reasoning equally unsound, built the solid edifice of modern astronomy

…

for popularizing them goes to the Scottish mathematician John Napier, who published his Description of the Wonderful Rule of Logarithms in 1614. A decade later, Johannes Kepler enthusiastically used the new calculational tool when he was compiling astronomical tables about the positions of the planets and other heavenly bodies. Logarithms were the

…

. They wanted to understand why it was true, and this proof didn’t help. Likewise, consider a four-hundred-year-old geometry problem posed by Johannes Kepler. It asks for the densest way to pack equal-size spheres in three dimensions, akin to the problem faced by grocers when they pack oranges

…

, Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo (New York: Doubleday, 1957), 237–38, https://www.princeton.edu/~hos/h291/assayer.htm. 60 “coeternal with the divine mind”: Johannes Kepler, The Harmony of the World, translated by E. J. Aiton, A. M. Duncan, and J. V. Field, Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society 209 (1997

…

/what-are-josephson-juncti/. 74 longitude problem: Sobel, Longitude. 75 global positioning system: Thompson, “Global Positioning System,” and https://www.gps.gov. 78 Johannes Kepler: For Kepler’s life and work, see Owen Gingerich, “Johannes Kepler,” in Gillispie, Complete Dictionary, vol. 7, online at https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/science-and-technology/astronomy-biographies

…

/johannes-kepler#kjen14, with amendments by J. R. Voelkel in vol. 22. See also Kline, Mathematics in Western Culture, 110–25; Edwards, The Historical Development, 99–103;

…

, 96–99; Simmons, Calculus Gems, 69–83; and Burton, History of Mathematics, 355–60. 78 “criminally inclined”: Quoted in Gingerich, “Johannes Kepler,” https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/science-and-technology/astronomy-biographies/johannes-kepler#kjen14. 78 “bad-tempered”: Ibid. 78 “such a superior and magnificent mind”: Ibid. 79 “Day and night I was consumed

…

Owen Gingerich, The Book Nobody Read: Chasing the Revolutions of Nicolaus Copernicus (New York: Penguin, 2005), 48. 84 “sacred frenzy”: Quoted in Gingerich, “Johannes Kepler,” https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/science-and-technology/astronomy-biographies/johannes-kepler#kjen14. 85 “My dear Kepler, I wish we could laugh”: Quoted in Martínez, Science Secrets, 34. 86

…

“Johannes Kepler became enamored”: Koestler, The Sleepwalkers, 33. 4. The Dawn of Differential Calculus 90 China, India, and the Islamic world: Katz, “Ideas of Calculus”; Katz, History

Our Moon: How Earth's Celestial Companion Transformed the Planet, Guided Evolution, and Made Us Who We Are

by Rebecca Boyle · 16 Jan 2024 · 354pp · 109,574 words

it. As historian Mott Greene describes him, Wegener knew more about selenography than most geologists, and knew more about geology than any selenographer.9 Like Johannes Kepler, he stood above the field of research that he’d carefully surveyed, and incorporated other scientists’ findings into his own new, unorthodox theories. Wegener owned

…

abundant, which is one of those bits of information, now common knowledge, that was unthinkable not so long ago. The Kepler Space Telescope, named for Johannes Kepler, found worlds aplenty when it stared at a small patch of sky between 2009 and 2018. The telescope’s namesake could never have imagined it

…

concept of seeking astronomical knowledge for its own sake would power the minds of the most consequential scientists to follow, twenty centuries later: Nicolaus Copernicus, Johannes Kepler, and Galileo Galilei. But not yet. TO FOLLOW IN the footsteps of Anaxagoras and Aristotle, the makers of the Western scientific tradition first had to

…

the nature and fate of the soul. It’s practically a compendium of early astronomy, covering Plato, Aristarchus, Anaxagoras, and more. The mathematician and astronomer Johannes Kepler, who was keenly interested in the Moon, produced his own translation of De Facie and considered publishing it. He called it “the most valuable discussion

…

century C.E., people did start asking those questions, or at least they finally began writing them down and publishing them. Men like Thomas Harriot, Johannes Kepler, and Galileo Galilei changed the way we saw the cosmos. They were the first modern scientists, and they bequeathed to us a new era and

…

how much light will bend when it travels through a material. The law had eluded Harriot’s contemporary and frequent correspondent, the inimitable German astronomer Johannes Kepler. “Measuring refractions, here I get stuck. Good God, what a hidden ratio!” Kepler wrote ruefully in 1603.11 Figuring out the law of refraction should

…

he offered his own philosophical interpretation. A HALF CENTURY after he published them, Copernicus’s ideas would change everything for both Galileo and a young Johannes Kepler, at university in Germany. In 1595, Kepler dove into Copernicus’s work in much the same way that Copernicus studied the Epitome of the Almagest

…

painterly views could not divorce the Moon from the divine, nor remove it entirely from myth. Exploration could not kill spirituality. Galileo’s frequent correspondent, Johannes Kepler, understood this better than arguably anyone else of his generation. Though he revolutionized astronomy by giving us the laws of planetary motion, Kepler imagined that

…

yet seen the Moon through a telescope. But it was up and full, and after pondering it for some time before the clouds rolled in, Johannes Kepler fell into a deep sleep and began to dream. In his dream, he picked up a book by an Icelandic astronomer named Duracotus, who explains

…

comes from his short story “Somnium, seu astronomia lunari” (“Dream, or Astronomy of the Moon”), circulated during his life but only published after his death. JOHANNES KEPLER STOOD on a fulcrum between two worlds. His training, education, upbringing, and belief systems were decidedly medieval, but his own research and writing were practically

…

American politics and industry. Von Braun grew up in Berlin in a wealthy aristocratic family. After he made his confirmation in the Lutheran Church, like Johannes Kepler before him, von Braun’s mother gifted him a telescope. He read Oberth’s rocket designs as a child, ultimately working with Oberth to test

…

Moon. JUST AS IT was for the Puebloans, just as it was for Enheduanna and Nabonidus, just as it was for the Greek philosophers and Johannes Kepler and Wernher von Braun and Michael Collins, the Moon can still be special and untouchable. It can remain a spectral reminder in the night. It

…

-8_13. Koestler, Arthur. The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man’s Changing Vision of the Universe. 1959; reprint London: Hutchinson, 1968. ⸻. Watershed: A Biography of Johannes Kepler. New York: Doubleday Anchor, 1960. Krauss, Rolf. “Astronomy and Chronology—Babylonia, Assyria, and Egypt.” In Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy, ed. C. L. N. Ruggles

…

the Orb of the Moon,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 8, no. 3 (1983): 361–72, https://doi.org/10.2307/622050. See Johannes Kepler, Somnium, seu opus posthumum De astronomia lunari, ed. Ludovico Kepler (Frankfurt, 1634), TK. 18. Plutarch, “On the Apparent Face in the Orb of the Moon

To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern Science

by Steven Weinberg · 17 Feb 2015 · 532pp · 133,143 words

centuries to understand the inequality of the seasons, but the correct explanation of this and other anomalies was not found until the seventeenth century, when Johannes Kepler realized that the Earth moves around the Sun on an orbit that is elliptical rather than circular, with the Sun not at the center of

…

and started work on a new set of astronomical tables, the Rudolphine Tables. After Tycho’s death in 1601, this work was continued by Kepler. Johannes Kepler was the first to understand the nature of the departures from uniform circular motion that had puzzled astronomers since the time of Plato. As a

…

—Mechanism and Mechanics (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1977), p. 10. 17. This is the translation of William H. Donahue, in Johannes Kepler—New Astronomy (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992), p. 65. 18. Johannes Kepler, Epitome of Copernican Astronomy and Harmonies of the World, trans. Charles Glenn Wallis (Prometheus, Amherst, N.Y., 1995), p. 180

…

Clocks, trans. Richard J. Blackwell (Iowa State University Press, Ames, 1986). , Treatise on Light, trans. Silvanus P. Thompson (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Ill., 1945). Johannes Kepler, Epitome of Copernican Astronomy and Harmonies of the World, trans. C. G. Wallis (Prometheus, Amherst, N.Y., 1995). , New Astronomy (Astronomia Nova), trans. W. H

God Created the Integers: The Mathematical Breakthroughs That Changed History

by Stephen Hawking · 28 Mar 2007

by 1666, but he was as yet unable to adequately explain the mechanics of circular motion. Some fifty years earlier, the German mathematician and astronomer Johannes Kepler had proposed three laws of planetary motion, which accurately described how the planets moved in relation to the sun, but he could not explain why

Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century

by Geoffrey Parker · 29 Apr 2013 · 1,773pp · 486,685 words

world than in many ages before’. He wrote just after the appearance of three comets in 1618, which excited widespread anxiety. Even before they appeared, Johannes Kepler, the foremost mathematician of his day, warned in his Astrological Almanac for 1618 that the conjunction of five planets in May would cause extreme climatic

…

from central Europe. Some were intellectuals at the height of their powers (like the musician Heinrich Schütz, the poet Martin Opitz, the mathematician and astronomer Johannes Kepler); others were country folk who could not protect their families, like the village shoemaker Hans Heberle, who had to flee with his family to Ulm

…

, 1603–1688: Documents and commentary (Cambridge, 1966) Kepler, Johannes, Prognosticum astrologicum auff das Jahr … 1618 (Linz, 1618), reprinted in V. Bialas and H. Grüssing, eds, Johannes Kepler Gesammelte Werke, XI part 2 (Munich, 1993) Kingsbury, S. M., The records of the Virginia Company of London, 4 vols (Washington, DC, 1906–35) Knowler

Coming of Age in the Milky Way

by Timothy Ferris · 30 Jun 1988 · 661pp · 169,298 words

sun orbited the earth, and was in turn orbited by the other planets. (Not to scale.) Amazingly, just such a man turned up. He was Johannes Kepler, and on February 4, 1600, he arrived at Benatek Castle near Prague, where Tycho had moved his observatory and retinue after his benefactor King Frederick

…

Vigier, eds. Quantum, Space, and Time—The Quest Continues. London: Cambridge University Press, 1984. Essays in honor of de Broglie, Dirac, and Wigner. Baumgardt, Carola. Johannes Kepler, Life and letters. New York: Philosophical Library, 1951. Beaglehole, J.C. The Exploration of the Pacific. London: Black, 1966. Beazley, Charles Raymond. Prince Henry the

Empire of the Sum: The Rise and Reign of the Pocket Calculator

by Keith Houston · 22 Aug 2023 · 405pp · 105,395 words

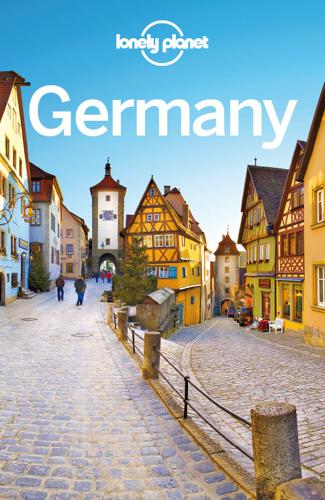

Germany Travel Guide

by Lonely Planet

A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy

by Joel Mokyr · 8 Jan 2016 · 687pp · 189,243 words

The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World's Most Astonishing Number

by Mario Livio · 23 Sep 2003

Germany

by Andrea Schulte-Peevers · 17 Oct 2010

The Clockwork Universe: Saac Newto, Royal Society, and the Birth of the Modern WorldI

by Edward Dolnick · 8 Feb 2011 · 439pp · 104,154 words

Is God a Mathematician?

by Mario Livio · 6 Jan 2009 · 315pp · 93,628 words

The Planets

by Dava Sobel · 1 Jan 2005 · 190pp · 52,570 words

Big Bang

by Simon Singh · 1 Jan 2004 · 492pp · 149,259 words

Against the Machine: On the Unmaking of Humanity

by Paul Kingsnorth · 23 Sep 2025 · 388pp · 110,920 words

The Crowded Universe: The Search for Living Planets

by Alan Boss · 3 Feb 2009 · 221pp · 61,146 words

Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions

by Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths · 4 Apr 2016 · 523pp · 143,139 words

Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World

by David Epstein · 1 Mar 2019 · 406pp · 109,794 words

Accessory to War: The Unspoken Alliance Between Astrophysics and the Military

by Neil Degrasse Tyson and Avis Lang · 10 Sep 2018 · 745pp · 207,187 words

Keeping Up With the Quants: Your Guide to Understanding and Using Analytics

by Thomas H. Davenport and Jinho Kim · 10 Jun 2013 · 204pp · 58,565 words

The Human Cosmos: A Secret History of the Stars

by Jo Marchant · 15 Jan 2020 · 544pp · 134,483 words

The Rough Guide to Prague

by Humphreys, Rob

Time of the Magicians: Wittgenstein, Benjamin, Cassirer, Heidegger, and the Decade That Reinvented Philosophy

by Wolfram Eilenberger · 14 Sep 2020

Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea

by Charles Seife · 31 Aug 2000 · 233pp · 62,563 words

The Interstellar Age: Inside the Forty-Year Voyager Mission

by Jim Bell · 24 Feb 2015 · 310pp · 89,653 words

The Habsburgs: To Rule the World

by Martyn Rady · 24 Aug 2020 · 461pp · 139,924 words

Loonshots: How to Nurture the Crazy Ideas That Win Wars, Cure Diseases, and Transform Industries

by Safi Bahcall · 19 Mar 2019 · 393pp · 115,217 words

Europe: A History

by Norman Davies · 1 Jan 1996

Exoplanets: Hidden Worlds and the Quest for Extraterrestrial Life

by Donald Goldsmith · 9 Sep 2018 · 265pp · 76,875 words

The Case for Space: How the Revolution in Spaceflight Opens Up a Future of Limitless Possibility

by Robert Zubrin · 30 Apr 2019 · 452pp · 126,310 words

Galileo's Dream

by Kim Stanley Robinson · 29 Dec 2009 · 615pp · 189,720 words

The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity's Search for Meaning

by Jeremy Lent · 22 May 2017 · 789pp · 207,744 words

The Musical Human: A History of Life on Earth

by Michael Spitzer · 31 Mar 2021 · 632pp · 163,143 words

Case for Mars

by Robert Zubrin · 27 Jun 2011 · 437pp · 126,860 words

The Map of Knowledge: How Classical Ideas Were Lost and Found: A History in Seven Cities

by Violet Moller · 21 Feb 2019

Pathfinders: The Golden Age of Arabic Science

by Jim Al-Khalili · 28 Sep 2010 · 467pp · 114,570 words

Isaac Newton

by James Gleick · 1 Jan 2003 · 244pp · 68,223 words

QI: The Third Book of General Ignorance (Qi: Book of General Ignorance)

by John Lloyd and John Mitchinson · 28 Sep 2015 · 432pp · 85,707 words

When Einstein Walked With Gödel: Excursions to the Edge of Thought

by Jim Holt · 14 May 2018 · 436pp · 127,642 words

Five Billion Years of Solitude: The Search for Life Among the Stars

by Lee Billings · 2 Oct 2013 · 326pp · 97,089 words

Strange New Worlds: The Search for Alien Planets and Life Beyond Our Solar System

by Ray Jayawardhana · 3 Feb 2011 · 257pp · 66,480 words

Reinventing Discovery: The New Era of Networked Science

by Michael Nielsen · 2 Oct 2011 · 400pp · 94,847 words

The Art of Computer Programming: Fundamental Algorithms

by Donald E. Knuth · 1 Jan 1974

4th Rock From the Sun: The Story of Mars

by Nicky Jenner · 5 Apr 2017 · 294pp · 87,986 words

Where Good Ideas Come from: The Natural History of Innovation

by Steven Johnson · 5 Oct 2010 · 298pp · 81,200 words

The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood

by James Gleick · 1 Mar 2011 · 855pp · 178,507 words

Top 10 Prague

by Schwinke, Theodore.

The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication From Ancient Times to the Internet

by David Kahn · 1 Feb 1963 · 1,799pp · 532,462 words

What We Cannot Know: Explorations at the Edge of Knowledge

by Marcus Du Sautoy · 18 May 2016

The Knowledge Machine: How Irrationality Created Modern Science

by Michael Strevens · 12 Oct 2020

This Will Make You Smarter: 150 New Scientific Concepts to Improve Your Thinking

by John Brockman · 14 Feb 2012 · 416pp · 106,582 words

You've Been Played: How Corporations, Governments, and Schools Use Games to Control Us All

by Adrian Hon · 14 Sep 2022 · 371pp · 107,141 words

Shape: The Hidden Geometry of Information, Biology, Strategy, Democracy, and Everything Else

by Jordan Ellenberg · 14 May 2021 · 665pp · 159,350 words

Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity

by Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson · 15 May 2023 · 619pp · 177,548 words

The Right Side of History

by Ben Shapiro · 11 Feb 2019 · 270pp · 71,659 words

Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making for an Unknowable Future

by Mervyn King and John Kay · 5 Mar 2020 · 807pp · 154,435 words

Galileo's Daughter: A Historical Memoir of Science, Faith and Love

by Dava Sobel · 25 May 2009 · 363pp · 108,670 words

Einstein's Dice and Schrödinger's Cat: How Two Great Minds Battled Quantum Randomness to Create a Unified Theory of Physics

by Paul Halpern · 13 Apr 2015 · 282pp · 89,436 words

The Moon: A History for the Future

by Oliver Morton · 1 May 2019 · 319pp · 100,984 words

Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray

by Sabine Hossenfelder · 11 Jun 2018 · 340pp · 91,416 words

Our Own Devices: How Technology Remakes Humanity

by Edward Tenner · 8 Jun 2004 · 423pp · 126,096 words

How to Read a Book

by Mortimer J. Adler and Charles van Doren · 14 Jun 1972 · 444pp · 139,784 words

The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous

by Joseph Henrich · 7 Sep 2020 · 796pp · 223,275 words

The Curse of Cash

by Kenneth S Rogoff · 29 Aug 2016 · 361pp · 97,787 words

Models. Behaving. Badly.: Why Confusing Illusion With Reality Can Lead to Disaster, on Wall Street and in Life

by Emanuel Derman · 13 Oct 2011 · 240pp · 60,660 words

Thinking in Numbers

by Daniel Tammet · 15 Aug 2012 · 212pp · 68,754 words

Age of Discovery: Navigating the Risks and Rewards of Our New Renaissance

by Ian Goldin and Chris Kutarna · 23 May 2016 · 437pp · 113,173 words

A History of the Bible: The Story of the World's Most Influential Book

by John Barton · 3 Jun 2019 · 904pp · 246,845 words

Escape From Rome: The Failure of Empire and the Road to Prosperity

by Walter Scheidel · 14 Oct 2019 · 1,014pp · 237,531 words

The Fractalist

by Benoit Mandelbrot · 30 Oct 2012

Beyond: Our Future in Space

by Chris Impey · 12 Apr 2015 · 370pp · 97,138 words

The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars

by Dava Sobel · 6 Dec 2016 · 442pp · 110,704 words

Alex's Adventures in Numberland

by Alex Bellos · 3 Apr 2011 · 437pp · 132,041 words

Wonders of the Universe

by Brian Cox and Andrew Cohen · 12 Jul 2011

When Things Start to Think

by Neil A. Gershenfeld · 15 Feb 1999 · 238pp · 46 words

Sextant: A Young Man's Daring Sea Voyage and the Men Who ...

by David Barrie · 12 May 2014 · 366pp · 100,602 words

On the Future: Prospects for Humanity

by Martin J. Rees · 14 Oct 2018 · 193pp · 51,445 words

Paradox: The Nine Greatest Enigmas in Physics

by Jim Al-Khalili · 22 Oct 2012 · 208pp · 70,860 words

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress

by Steven Pinker · 13 Feb 2018 · 1,034pp · 241,773 words

The Fabric of Reality

by David Deutsch · 31 Mar 2012 · 511pp · 139,108 words

Literary Theory for Robots: How Computers Learned to Write

by Dennis Yi Tenen · 6 Feb 2024 · 169pp · 41,887 words

Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking

by Michael Bhaskar · 2 Nov 2021

Ten Billion Tomorrows: How Science Fiction Technology Became Reality and Shapes the Future

by Brian Clegg · 8 Dec 2015 · 315pp · 92,151 words

Black Box Thinking: Why Most People Never Learn From Their Mistakes--But Some Do

by Matthew Syed · 3 Nov 2015 · 410pp · 114,005 words

The Magic of Reality: How We Know What's Really True

by Richard Dawkins · 3 Oct 2011 · 208pp · 67,288 words

The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World

by David Deutsch · 30 Jun 2011 · 551pp · 174,280 words

The Sirens of Mars: Searching for Life on Another World

by Sarah Stewart Johnson · 6 Jul 2020 · 400pp · 99,489 words

Trillions: How a Band of Wall Street Renegades Invented the Index Fund and Changed Finance Forever

by Robin Wigglesworth · 11 Oct 2021 · 432pp · 106,612 words

The God Equation: The Quest for a Theory of Everything

by Michio Kaku · 5 Apr 2021 · 157pp · 47,161 words

Erwin Schrodinger and the Quantum Revolution

by John Gribbin · 1 Mar 2012 · 287pp · 87,204 words

The End of Astronauts: Why Robots Are the Future of Exploration

by Donald Goldsmith and Martin Rees · 18 Apr 2022 · 192pp · 63,813 words

Extraterrestrial Civilizations

by Isaac Asimov · 2 Jan 1979 · 330pp · 99,226 words

The Golden Ticket: P, NP, and the Search for the Impossible

by Lance Fortnow · 30 Mar 2013 · 236pp · 50,763 words

Adventures in Human Being (Wellcome)

by Gavin Francis · 28 Apr 2015 · 226pp · 66,188 words

Neutrino Hunters: The Thrilling Chase for a Ghostly Particle to Unlock the Secrets of the Universe

by Ray Jayawardhana · 10 Dec 2013 · 203pp · 63,257 words

Data-Ism: The Revolution Transforming Decision Making, Consumer Behavior, and Almost Everything Else

by Steve Lohr · 10 Mar 2015 · 239pp · 70,206 words

Steve Jobs

by Walter Isaacson · 23 Oct 2011 · 915pp · 232,883 words

Double Entry: How the Merchants of Venice Shaped the Modern World - and How Their Invention Could Make or Break the Planet

by Jane Gleeson-White · 14 May 2011 · 274pp · 66,721 words

A Brief History of Time

by Stephen Hawking · 16 Aug 2011 · 186pp · 64,267 words

The Perfect Bet: How Science and Math Are Taking the Luck Out of Gambling

by Adam Kucharski · 23 Feb 2016 · 360pp · 85,321 words

How the Mind Works

by Steven Pinker · 1 Jan 1997 · 913pp · 265,787 words

Space Chronicles: Facing the Ultimate Frontier

by Neil Degrasse Tyson and Avis Lang · 27 Feb 2012 · 476pp · 118,381 words

The Power of Geography: Ten Maps That Reveal the Future of Our World

by Tim Marshall · 14 Oct 2021 · 383pp · 105,387 words

Average Is Over: Powering America Beyond the Age of the Great Stagnation

by Tyler Cowen · 11 Sep 2013 · 291pp · 81,703 words

The Card Catalog: Books, Cards, and Literary Treasures

by Library Of Congress and Carla Hayden · 3 Apr 2017

Nervous States: Democracy and the Decline of Reason

by William Davies · 26 Feb 2019 · 349pp · 98,868 words

Are You Smart Enough to Work at Google?: Trick Questions, Zen-Like Riddles, Insanely Difficult Puzzles, and Other Devious Interviewing Techniques You ... Know to Get a Job Anywhere in the New Economy

by William Poundstone · 4 Jan 2012 · 260pp · 77,007 words

Massive: The Missing Particle That Sparked the Greatest Hunt in Science

by Ian Sample · 1 Jan 2010 · 310pp · 89,838 words

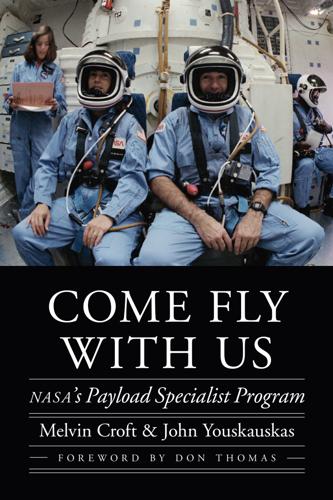

Come Fly With Us: NASA's Payload Specialist Program

by Melvin Croft, John Youskauskas and Don Thomas · 1 Feb 2019 · 609pp · 159,043 words

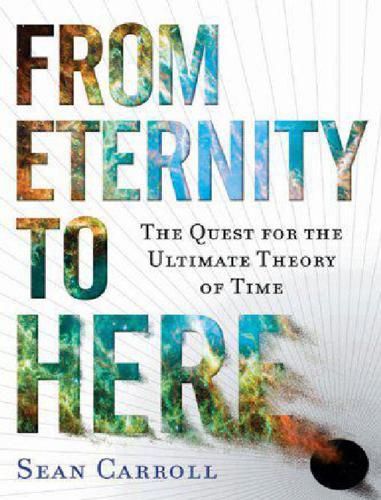

From eternity to here: the quest for the ultimate theory of time

by Sean M. Carroll · 15 Jan 2010 · 634pp · 185,116 words

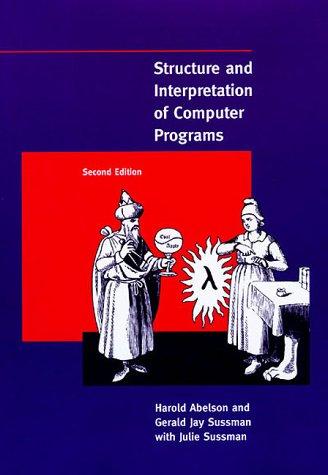

Structure and interpretation of computer programs

by Harold Abelson, Gerald Jay Sussman and Julie Sussman · 25 Jul 1996 · 893pp · 199,542 words

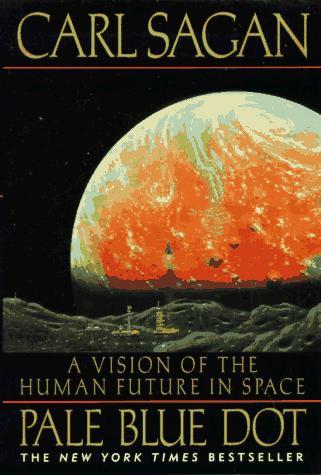

Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space

by Carl Sagan · 8 Sep 1997 · 356pp · 102,224 words

Too Big to Know: Rethinking Knowledge Now That the Facts Aren't the Facts, Experts Are Everywhere, and the Smartest Person in the Room Is the Room

by David Weinberger · 14 Jul 2011 · 369pp · 80,355 words

The Grand Design

by Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow · 14 Jun 2010 · 124pp · 40,697 words

Miracle Cure

by William Rosen · 14 Apr 2017 · 515pp · 117,501 words

The Theory That Would Not Die: How Bayes' Rule Cracked the Enigma Code, Hunted Down Russian Submarines, and Emerged Triumphant From Two Centuries of Controversy

by Sharon Bertsch McGrayne · 16 May 2011 · 561pp · 120,899 words

The Laws of Medicine: Field Notes From an Uncertain Science

by Siddhartha Mukherjee · 12 Oct 2015 · 52pp · 16,113 words

We-Think: Mass Innovation, Not Mass Production

by Charles Leadbeater · 9 Dec 2010 · 313pp · 84,312 words

How to Make a Spaceship: A Band of Renegades, an Epic Race, and the Birth of Private Spaceflight

by Julian Guthrie · 19 Sep 2016

EuroTragedy: A Drama in Nine Acts

by Ashoka Mody · 7 May 2018

On Intelligence

by Jeff Hawkins and Sandra Blakeslee · 1 Jan 2004 · 246pp · 81,625 words

Think Like a Rocket Scientist: Simple Strategies You Can Use to Make Giant Leaps in Work and Life

by Ozan Varol · 13 Apr 2020 · 389pp · 112,319 words

In the Land of Invented Languages: Adventures in Linguistic Creativity, Madness, and Genius

by Arika Okrent · 1 Jan 2009 · 226pp · 75,783 words

Illustrated Theory of Everything: The Origin and Fate of the Universe

by Stephen Hawking · 1 Aug 2009 · 81pp · 28,120 words

Letters From an Astrophysicist

by Neil Degrasse Tyson · 7 Oct 2019 · 189pp · 49,386 words

Stealth of Nations

by Robert Neuwirth · 18 Oct 2011 · 340pp · 91,387 words

What to Think About Machines That Think: Today's Leading Thinkers on the Age of Machine Intelligence

by John Brockman · 5 Oct 2015 · 481pp · 125,946 words

The Scientist as Rebel

by Freeman Dyson · 1 Jan 2006 · 332pp · 109,213 words

The Interior Design Handbook

by Frida Ramstedt · 27 Oct 2020

Giving the Devil His Due: Reflections of a Scientific Humanist

by Michael Shermer · 8 Apr 2020 · 677pp · 121,255 words

Off the Edge: Flat Earthers, Conspiracy Culture, and Why People Will Believe Anything

by Kelly Weill · 22 Feb 2022

Time Travelers Never Die

by Jack McDevitt · 10 Sep 2009 · 460pp · 108,654 words

Shorter: Work Better, Smarter, and Less Here's How

by Alex Soojung-Kim Pang · 10 Mar 2020 · 257pp · 76,785 words

The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work

by Alain de Botton · 1 Apr 2009 · 168pp · 56,211 words

Building Habitats on the Moon: Engineering Approaches to Lunar Settlements

by Haym Benaroya · 12 Jan 2018 · 571pp · 124,448 words

12 Bytes: How We Got Here. Where We Might Go Next

by Jeanette Winterson · 15 Mar 2021 · 256pp · 73,068 words

Imagine a City: A Pilot's Journey Across the Urban World

by Mark Vanhoenacker · 14 Aug 2022 · 393pp · 127,847 words

The New Gold Rush: The Riches of Space Beckon!

by Joseph N. Pelton · 5 Nov 2016 · 321pp · 89,109 words

Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration

by Ed Catmull and Amy Wallace · 23 Jul 2009 · 325pp · 110,330 words

GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History

by Diane Coyle · 23 Feb 2014 · 159pp · 45,073 words

This Sceptred Isle

by Christopher Lee · 19 Jan 2012 · 796pp · 242,660 words

Possible Minds: Twenty-Five Ways of Looking at AI

by John Brockman · 19 Feb 2019 · 339pp · 94,769 words

Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs, Second Edition

by Harold Abelson, Gerald Jay Sussman and Julie Sussman · 1 Jan 1984 · 1,387pp · 202,295 words

The Fourth Age: Smart Robots, Conscious Computers, and the Future of Humanity

by Byron Reese · 23 Apr 2018 · 294pp · 96,661 words

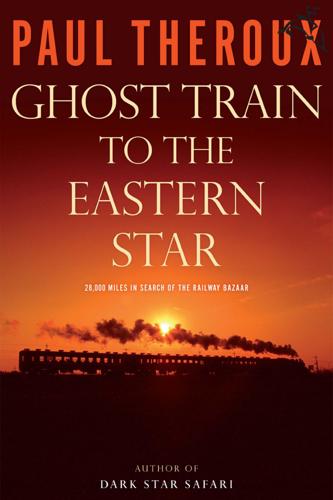

Ghost Train to the Eastern Star: On the Tracks of the Great Railway Bazaar

by Paul Theroux · 9 Sep 2008 · 651pp · 190,224 words