Symmetry and the Monster

by

Ronan, Mark

Published 14 Sep 2006

Kumar, The densest lattice in twenty-four dimensions, Electronic Research Anouncements of the American Mathematical Society, 2004 (www.mpim-bonn.mpg.de/external-documentation/era-mirror/era-msc–2004.html). 149 Donald Higman and Graham Higman are not related. They just happened to work in the same area of mathematics. 150 Quotations from Conway appear in Thomas Thompson, From Error-correcting Codes through Sphere Packings to Simple Groups, Carus Mathematical Monograph 21, Mathematical Association of America, 1983. 156 John Conway, On Numbers and Games, Academic Press, 1976; Elwyn Berlekamp, John Conway, and Richard Guy, Winning Ways for Your Mathematical Plays, Academic Press, 1982.

…

Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset in Times by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Clays Limited, St Ives plc ISBN 0-19-280722-6 978-0-19-280722-9 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Preface In recent years several books on mathematics have been published, presenting intriguing pieces of the subject. This book also presents some interesting gems, but in the service of explaining one of the big quests of mathematics: the discovery and classification of all the basic building blocks for symmetry. Some mathematicians were sceptical of explaining it in a non-technical way, but others were very encouraging, and I would like to thank them. In particular I owe thanks to those mathematicians who read all, or large parts, of the manuscript: Jon Alperin, John Conway, Bernd Fischer, Bill Kantor, and Richard Weiss.

…

He checked up on other numbers – far bigger than 196,883 – that came out of the Monster and compared them to those that emerge in number theory from the miraculous object that McKay had been reading about. Thompson found further coincidences and saw that a more detailed study was called for. When he returned to Cambridge in December – he’d been visiting the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton when he received McKay’s letter – he mentioned these coincidences to John Conway, who had found some of the new symmetry objects himself. Conway had masses of data on the Monster, and used it to produce other sequences of numbers that might be interesting. He then visited the library and found the same sequences appearing in some nineteenth-century papers on number theory. He and a young mathematician named Simon Norton used these facts to make further calculations and verify that there was a definite connection between the Monster and number theory, even though we didn’t understand why.

Massive: The Missing Particle That Sparked the Greatest Hunt in Science

by

Ian Sample

Published 1 Jan 2010

As high-energy facilities rise and fall on different continents, scientists migrate to wherever they have the greatest chance of finding something new in nature. With modern computer networks, some make the move a virtual one and analyze collision data from the comfort of their university offices. Others up sticks to follow the action. John Conway is a case in point. An experimentalist at the University of California at Davis, he spent years at CERN with the Aleph team, the group that went on to see tantalizing hints of the Higgs particle. Long before the excitement broke out, Conway returned to the United States to help revamp the CDF detector at Fermilab.

…

It is a feeling that drives many people to do science. “You have this hope that someday you’ll see something that is genuinely new, that no one else in the world has ever seen,” he said. “You want to make a discovery.” At Fermilab, there are two detectors that physicists use to hunt for the Higgs particle. John Conway’s team searched for evidence of the elusive boson amid collisions recorded by the CDF detector. Other groups use the DZero detector. One of the spokesmen for the DZero collaboration is Dmitri Denisov, a Russian-born scientist who was educated in Moscow by some of the country’s most respected physicists.

…

Countless scientists and engineers gave up some of their precious time to talk with me while I was researching the book, and I’m profoundly grateful to all of them. The end result was vastly improved thanks to those who checked my clumsy drafts, including Steven Weinberg, John Ellis, Michael Fisher, Lyn Evans, John Conway, Gerry Guralnik, and Dick Hagen. Peter Higgs provided comprehensive and invaluable comments on key chapters and put me right on many occasions. His help is a debt I cannot repay. Thanks to Freeman Dyson for digging back through his memories to tell me about Peter Higgs’s visit to the Institute for Advanced Study in 1966 and for his reflections on Robert Oppenheimer.

The Ultimate Engineer: The Remarkable Life of NASA's Visionary Leader George M. Low

by

Richard Jurek

Published 2 Dec 2019

He would spend a considerable amount of time traveling to the field centers, interviewing and sampling the thoughts and ideas of the young engineers and scientists “to determine how best to continue their training and development of their careers.” It was a concerted effort “to identify the future leaders of NASA.” He viewed the young, technical minds “as superior to what Low and his contemporaries” offered NASA when they were at this stage of their careers. John Conway was one such engineer that Low visited during his center tours. At the time, Conway was a twenty-something engineer working in the centralized computer facilities at Kennedy Space Center. “One of my bosses came to me one day and said, ‘George Low is making a visit to KSC, and you’ve been selected to visit with him,’” he recalled.

…

It’s just too nonforgiving an environment without extremely smart people involved.22 In a post–George Low NASA, people worried that “the intrusion of politics and bureaucracy would compromise the performance of the agency” and that with the culture and character change of new people—outside, nontechnical people—coming on board in executive management, the attention to detail and the ability to air out engineering issues and balance differing technical opinions would be lost.23 It was a similar concern that Low himself had expressed to young John Conway many years ago in his cubicle—it was the leadership that set the tone, that often made the life or death difference at NASA. “In looking back over 26 and a half years of service, I can honestly say that NASA is the best Agency in government,” he told the NASA center directors on 21 April 1976, in his stylistically pragmatic and blunt manner.

…

A humble shout-out to my friends and fellow writers and space enthusiasts who provided encouragement, input, perspective (many via long phone calls and endless emails), and advice; read chapters; and made suggestions and who were, frankly, just there for me when I needed them: Alan Andres, Leslie Cantwell, Andy Chaikin, Francis French, Larry McGlynn, Bruce Moody, Chris Orwoll, Robert Pearlman, Jason Rubin, David Meerman Scott, Art Siemientkowski, Robert Stone, and Steve Worth. I am highly appreciative and indebted to all those who sat for long interviews, told me their stories and experiences, exchanged emails with me, and gave so freely of their memories and recollections, including George Abbey, Bill Anders, Bob Blue, Frank Borman, Jerry Bostick, Andy Chaikin, John Conway, Gerry Griffin, Chris Kraft, Roger Launius, John Logsdon, Jim Lovell, Glynn Lunney, Jim McDivitt, Dorothy Reynolds, Walter Robb, Rusty Schweickart, Tom Stafford, Doug Ward, and Jack Welch. Special thanks also to the Low family: Mark Low, Diane Murphy, John Low, Nancy Sullivan, and Eva Verplank.

Shape: The Hidden Geometry of Information, Biology, Strategy, Democracy, and Everything Else

by

Jordan Ellenberg

Published 14 May 2021

He was a geometer: Some material in this section is adapted from Jordan Ellenberg, “A Fellow of Infinite Jest,” Wall Street Journal, Aug. 14, 2015. “the murder weapon”: István Hargittai, “John Conway—Mathematician of Symmetry and Everything Else,” Mathematical Intelligencer 23, no. 2 (2001): 8–9. He was a compulsive: R. H. Guy, “John Horton Conway: Mathematical Magus,” Two-Year College Mathematics Journal 13, no. 5 (Nov. 1982): 290–99. began to create numbers: Donald Knuth, Surreal Numbers: How Two Ex-Students Turned on to Pure Mathematics and Found Total Happiness (Boston: Addison-Wesley, 1974). The Knuth book introduces Conway’s novel number system, but the connection of these numbers with games comes in Conway’s 1976 book On Numbers and Games.

…

So the next term is 11, or “two ones.” That makes the next term 21, or “one two, one one,” which you spell out as 1211, “one one, one two, two ones,” and so on. This is just an amusement, or so it seemed to the Dutch math team. But sometime in 1983 the Look-and-Say sequence made its way to John Conway, for whom making amusements into mathematics (and mathematics into amusement) was a way of life. Conway showed that the Look-and-Say sequence never contains a number greater than 3, and that the long-term behavior of the sequence is controlled by the behavior of exactly ninety-two special digit strings, which Conway called “atoms” and named after chemical elements (1113213211 is “hafnium” followed by “tin”).

…

When you have more than two piles, a simple symmetry argument like this doesn’t work. But there’s actually still a way to find out who wins without drawing the whole tree. It’s a bit too complex to describe here, involving the base-2 expansions of the sizes of all the piles, but you can learn all about it in Elwyn Berlekamp, John Conway, and Richard Guy’s astonishingly colorful, profound, and idea-rich book Winning Ways for Your Mathematical Plays, along with other games like Hackenbush, Snort, and Sprouts, and why every game is, in the end, a kind of number. In a variant of Nim called the “subtraction game,” you start with just one pile of stones, but at each move you’re only allowed to take away 1, 2, or 3.

Complexity: A Guided Tour

by

Melanie Mitchell

Published 31 Mar 2009

“The Game of Life”: Much of what is described here can be found in the following sources: Berlekamp, E., Conway, J. H., and Guy, R., Winning Ways for Your Mathematical Plays, Volume 2. San Diego: Academic Press, 1982; Poundstone, W., The Recursive Universe. William Morrow, 1984; and many of the thousands of Web sites devoted to the Game of Life. “John Conway also sketched a proof”: Berlekamp, E., Conway, J. H., and Guy, R., Winning Ways for Your Mathematical Plays, volume 2. San Diego: Academic Press, 1982. “later refined by others”: e.g., see Rendell, P., Turing universality of the game of Life. In A.

…

Systems that are equivalent in power to universal Turing machines (i.e., can compute anything that a universal Turing machine can) are more generally called universal computers, or are said to be capable of universal computation or to support universal computation. The Game of Life Von Neumann’s cellular automaton rule was rather complicated; a much simpler, two-state cellular automaton also capable of universal computation was invented in 1970 by the mathematician John Conway. He called his invention the “Game of Life.” I’m not sure where the “game” part comes in, but the “life” part comes from the way in which Conway phrased the rule. Denoting on cells as alive and off cells as dead, Conway defined the rule in terms of four life processes: birth, a dead cell with exactly three live neighbors becomes alive at the next time step; survival, a live cell with exactly two or three live neighbors stays alive; loneliness, a live cell with fewer than two neighbors dies and a dead cell with fewer than three neighbors stays dead; and overcrowding, a live or dead cell with more than three live neighbors dies or stays dead.

…

Other intricate patterns that have been discovered by enthusiasts include the spaceship, a fancier type of glider, and the glider gun, which continually shoots out new gliders. Conway showed how to simulate Turing machines in Life by having the changing on/ off patterns of states simulate a tape head that reads and writes on a simulated tape. John Conway also sketched a proof (later refined by others) that Life could simulate a universal computer. This means that given an initial configuration of on and off states that encodes a program and the input data for that program, Life will run that program on that data, producing a pattern that represents the program’s output.

A Beautiful Mind

by

Sylvia Nasar

Published 11 Jun 1998

Phrasing the question precisely, Ambrose would have used the adverb “isometrically” — meaning “to preserve distances” — after “embedding.” 16. Shlomo Sternberg, professor of mathematics, Harvard University, interview, 3.5.96. 17. Mikhail Gromov, interview. 12.16.97. 18. John Forbes Nash, Jr., Lcs Prix Nobel 1994, op. cit. 19. Gromov, interview. 20. John Conway, professor of mathematics, Princeton University, interview, 10.94. 21. Jürgen Moser, e-mail, 12.24.97. 22. Richard Palais, professor of mathematics, Brandeis University, interview, 11.6.95. 23. Moser, interview. 24. Donald J. Newman, interview, 3.2.96. 25. Jürgen Moser, “A Rapidly Convergent Iteration Method and Non-linear Partial Differential Equations, I, II,” Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, vol. 20 (1966), pp. 265–315, 499–535. 26.

…

Psychologically the barrier he broke is absolutely fantastic. He has completely changed the perspective on partial differential equations. There has been some tendency in recent decades to move from harmony to chaos. Nash says chaos is just around the corner.19 John Conway, the Princeton mathematician who discovered surreal numbers and invented the game of Life, called Nash’s result “one of the most important pieces of mathematical analysis in this century.”20 It was also, one must add, a deliberate jab at then-fashionable approaches to Riemannian manifolds, just as Nash’s approach to the theory of games was a direct challenge to von Neumann’s.

…

The portrait of Artin is based on Gian-Carlo Rota, Indiscrete Thoughts, op. cit., as well as recollection of John Tate; Spencer, interview, 11.18.96; Hauser, interview; and materials from the Princeton University Archives. 64. Spencer, interview. 65. Kuhn, interview. 6: Games 1. Albert W. Tucker, as told to Harold Kuhn, interview. 2. Interviews with Marvin Minsky, professor of science, MIT, 2.13.96; John Tukey, 9.30.97; David Gale, 9.20.96; Melvin Hausner, 1.26.96 and 2.20.96; and John Conway, professor of mathematics, Princeton University, 10.94; John Isbell, e-mails, 1.25.96, 1.26.97, 1.27.97. 3. Isbell, e-mails. 4. Letter from John Nash to Martin Shubik, undated (1950 or 1951); Hausner, interviews and e-mails. 5. William Poundstone, Prisoner’s Dilemma, op. cit.; John Williams, The Compleat Strategist (New York: McGraw Hill, 1954). 6.

The End of Theory: Financial Crises, the Failure of Economics, and the Sweep of Human Interaction

by

Richard Bookstaber

Published 1 May 2017

His universal constructor gave rise to the concept of a von Neumann probe, a spacecraft capable of replicating itself, which could land on one galactic outpost, build a hundred copies of itself, each traveling off in one of a hundred different directions, discover other worlds, and replicate again, thereby exploring the universe—and, depending on the design of the machines, conquering the universe—with exponential efficiency. The universal constructor caught the interest of John Conway, a British mathematician who would later hold the John von Neumann Chair of Mathematics at Princeton, and over “eighteen months of coffee times,” as he describes it, he began tinkering to simplify its set of rules. The result was what became known as Conway’s Game of Life.9 The “game” really isn’t one—it is a zero-player game, because once the initial conditions of the cells are set, there is no further interaction or input as the process evolves.

…

Beyond Mechanical Markets: Asset Price Swings, Risk, and the Role of the State. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Gabrielsen, Alexandros, Massimiliano Marzo, and Paolo Zagaglia. 2011. “Measuring Market Liquidity: An Introductory Survey.” Quaderni DSE Working Paper no. 802. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1976149. Gardner, Martin. 1970. “Mathematical Games: The Fantastic Combinations of John Conway’s New Solitaire Game ‘Life.’” Scientific American 223: 120–23. Gigerenzer, Gerd. 2008. Rationality for Mortals: How People Cope with Uncertainty. Evolution and Cognition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Gigerenzer, Gerd, and Henry Brighton. 2009. “Homo Heuristics: Why Biased Minds Make Better Inferences.”

…

These apparently trivial contradictions were rooted in the core of mathematics and logic, and were only the most readily manifest examples of a limit to our ability to structure formal mathematical systems. TURING’S HALTING PROBLEM Although Gödel had taken apart Britain’s know-it-alls, the big fish to fry was not Russell and Whitehead, but the dean of early twentieth-century mathematics, David Hilbert. Hilbert, a German who taught at the University of Göttingen, sought a solution for what is called the decision problem for defining a closed mathematical universe: Is there a systematic procedure, a program, that can either prove or else disprove any statement expressed in the language?

Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution - 25th Anniversary Edition

by

Steven Levy

Published 18 May 2010

• • • • • • • • It was in 1970 that Bill Gosper began hacking LIFE. It was yet another system that was a world in itself, a world where behavior was “exceedingly rich, but not so rich as to be incomprehensible.” It would obsess Bill Gosper for years. LIFE was a game, a computer simulation developed by John Conway, a distinguished British mathematician. It was first described by Martin Gardner, in his "Mathematical Games" column in the October 1970 issue of Scientific American. The game consists of markers on a checkerboard-like field, each marker representing a “cell.” The pattern of cells changes with each move in the game (called a “generation”), depending on a few simple rules—cells die, are born, or survive to the next generation according to how many neighboring cells are in the vicinity.

…

The game-that-is-more-than-a-game, created by mathematician John Conway. The game that MIT wizard Bill Gosper had hacked so intently, to the point where he saw it as potentially generating life itself. The Altair version ran much more slowly than the PDP-6 program, of course, and with none of those elegantly hacked utilities, but it followed the same rules. And it did it while sitting on the kitchen table. Garland put in a few patterns, and Les Solomon, not fully knowing the rules of the game and certainly not aware of the deep philosophical and mathematical implications, watched the little blue, red, or green stars (that was the way the Dazzler made the cells look) eat the other little stars, or make more stars.

…

What Gosper and the hackers were seeking was called a glider gun. A glider was a pattern which would move across the screen, periodically reverting to the same pointed shape. If you ever created a LIFE pattern, which actually spewed out gliders as it changed shape, you’d have a glider gun, and LIFE’s inventor, John Conway, offered fifty dollars to the first person who was able to create one. The hackers would spend all night sitting at the PDP-6’s high-quality “340” display (a special, high-speed monitor made by DEC), trying different patterns to see what they’d yield. They would log each “discovery” they made in this artificial universe in a large black sketchbook, which Gosper dubbed the LIFE scrapbook.

The Grand Design

by

Stephen Hawking

and

Leonard Mlodinow

Published 14 Jun 2010

These mental concepts are the only reality we can know. There is no model-independent test of reality. It follows that a well-constructed model creates a reality of its own. An example that can help us think about issues of reality and creation is the Game of Life, invented in 1970 by a young mathematician at Cambridge named John Conway. The word “game” in the Game of Life is a misleading term. There are no winners and losers; in fact, there are no players. The Game of Life is not really a game but a set of laws that govern a two-dimensional universe. It is a deterministic universe: Once you set up a starting configuration, or initial condition, the laws determine what happens in the future.

…

In the late sixteenth century Kepler was convinced that God had created the universe according to some perfect mathematical principle. Newton showed that the same laws that apply in the heavens apply on earth, and developed mathematical equations to express those laws that were so elegant they inspired almost religious fervor among many eighteenth-century scientists, who seemed intent on using them to show that God was a mathematician. Ever since Newton, and especially since Einstein, the goal of physics has been to find simple mathematical principles of the kind Kepler envisioned, and with them to create a unified theory of everything that would account for every detail of the matter and forces we observe in nature.

…

The situation at both slits matters because, rather than following a single definite path, particles take every path, and they take them all simultaneously! That sounds like science fiction, but it isn’t. Feynman formulated a mathematical expression—the Feynman sum over histories—that reflects this idea and reproduces all the laws of quantum physics. In Feynman’s theory the mathematics and physical picture are different from that of the original formulation of quantum physics, but the predictions are the same. In the double-slit experiment Feynman’s ideas mean the particles take paths that go through only one slit or only the other; paths that thread through the first slit, back out through the second slit, and then through the first again; paths that visit the restaurant that serves that great curried shrimp, and then circle Jupiter a few times before heading home; even paths that go across the universe and back.

What Technology Wants

by

Kevin Kelly

Published 14 Jul 2010

Yet a particle’s spontaneous dissolution into subparticles and energy rays is not predictable, nor predetermined by laws of physics. We tend to call this decay into cosmic rays a “random” event. Mathematician John Conway proposed a proof arguing that neither the mathematics of randomness nor the logic of determinism can properly explain the sudden (why right now?) decay or shift of spin direction in cosmic particles. The only mathematical or logical option left is free will. The particle simply chooses in a way that is indistinguishable from the tiniest quantum bit of free will. Theoretical biologist Stuart Kauffman argues that this “free will” is a result of the mysterious quantum nature of the universe, by which quantum particles can be two places at once, or be both wave and particle at once.

…

But the weird and telling thing about this experiment, which has been done many times, is that the wave/particle only chooses its form (either a wave or a particle) after it has already passed through the slit and is measured on the other side. According to Kauffman, the particle’s shift from undecided state (called quantum decoherence) to the decided state (quantum coherence) is a type of volition and thus the source of free will in our own brains, since these quantum effects happen in all matter. As John Conway writes,Some readers may object to our use of the term “free will” to describe the indeterminism of particle responses. Our provocative ascription of free will to elementary particles is deliberate, since our theorem asserts that if experimenters have a certain freedom, then particles have exactly the same kind of freedom.

…

For many millions of years, rock ants have used a mathematical trick that was only discovered by humans in 1733. Rock ants can estimate the volume of a space, even an irregularly shaped one, by laying a scent trail across the floor of the space, “recording” the length of that line, and then counting the number of times they encounter that scented line during additional diagonal runs across the floor. The calculated area is inversely proportional to the frequency of intersections times length. In other words, the ants discovered an approximate value for pi derived by intersecting diagonals, a technique now known in mathematics as Buffon’s Needle.

On the Future: Prospects for Humanity

by

Martin J. Rees

Published 14 Oct 2018

The intricate structure of all living things testifies that layer on layer of complexity can emerge from the operation of underlying laws. Mathematical games can help to develop our awareness of how simple rules, reiterated over and over again, can indeed have surprisingly complex consequences. John Conway, now at Princeton University, is one of the most charismatic figures in mathematics.1 When he taught at Cambridge, students created a ‘Conway appreciation society’. His academic research deals with a branch of mathematics known as group theory. But he reached a wider audience and achieved a greater intellectual impact through developing the Game of Life.

…

As I’ve already noted (section 3.5), if we ever discover aliens and want to communicate with them, mathematics, physics, and astronomy would be perhaps the only shared culture. Mathematics is the language of science—and has been ever since the Babylonians devised their calendar and predicted eclipses. (Some of us would likewise regard music as the language of religion.) Paul Dirac, one of the pioneers of quantum theory, showed how the internal logic of mathematics can point the way towards new discoveries. Dirac averred that ‘the most powerful method of advance is to employ all the resources of pure mathematics in attempts to perfect and generalise the mathematical formalism that forms the existing basis of theoretical physics and—after each success in this direction—to try to interpret the new mathematical features in terms of physical entities’.3 It was this approach—following the mathematics where it leads—that led Dirac to the idea of antimatter: ‘antielectrons’, now known as positrons, were discovered just a few years after he formulated an equation that would have seemed ugly without them.

…

He used pencil and paper, before the days of personal computers, but the implications of the Game of Life only emerged when the greater speed of computers could be harnessed. Likewise, early PCs enabled Benoit Mandelbrot and others to plot out the marvellous patterns of fractals—showing how simple mathematical formulas can encode intricate apparent complexity. Most scientists resonate with the perplexity expressed in a classic essay by the physicist Eugene Wigner, titled ‘The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences’.2 And also with Einstein’s dictum that ‘the most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible’. We marvel that the physical world isn’t anarchic—that atoms obey the same laws in distant galaxies as in our laboratories.

Programming in Haskell

by

Graham Hutton

Published 5 Feb 2007

Using this approach, the function births can be rewritten as follows: births b = [p | p ← rmdups (concat (map neighbs b)), isEmpty b p, liveneighbs b p == 3] The auxiliary function rmdups removes duplicates from a list, and is used above to ensure that each potential new cell is only considered once: rmdups :: Eq a ⇒ [a ] → [a ] rmdups [ ] = [] rmdups (x : xs) = x : rmdups (filter (= x ) xs) The next generation of a board can now be produced simply by appending the list of survivors and the list of new births: nextgen :: Board → Board nextgen b = survivors b ++ births b 9.9 EXERCISES Finally, we define a function life that implements the game of life itself, by clearing the screen, showing the living cells in the current board, waiting for a moment, and then continuing with the next generation: life :: Board → IO () life b = do cls showcells b wait 5000 life (nextgen b) The function wait is used to slow down the game to a reasonable speed, and can be implemented by performing a given number of dummy actions: wait :: Int → IO () wait n = seqn [return () | ← [1 . . n ]] For fun, you may like to try out the life function with the glider example, and experiment with some patterns of your own. 9.8 Chapter remarks The use of the IO type to perform other forms of side effects, including reading and writing from files, and handling exceptional events, is discussed in the Haskell Report (25). A formal meaning for input/output and other forms of side effects is given in (24). A variety of libraries for performing graphical interaction are available from the Haskell home page, www .haskell .org . The game of life was invented by John Conway, and popularised by Martin Gardner in the October 1970 edition of Scientific American. 9.9 Exercises 1. Define an action readLine :: IO String that behaves in the same way as getLine , except that it also permits the delete key to be used to remove characters. Hint: the delete character is ’\DEL’, and the control string for moving the cursor back one character is "\ESC[1D". 2.

…

For reference, appendix A presents some of the most commonly used definitions from the standard prelude, and appendix B shows how special Haskell symbols, such as ↑ and ++, are typed using a normal keyboard. 2.3 Function application In mathematics, the application of a function to its arguments is usually denoted by enclosing the arguments in parentheses, while the multiplication of two values is often denoted silently, by writing the two values next to one another. For example, in mathematics the expression f (a, b) + c d means apply the function f to two arguments a and b , and add the result to the product of c and d . Reflecting its primary status in the language, function application in Haskell is denoted silently using spacing, while the multiplication 2.4 HASKELL SCRIPTS of two values is denoted explicitly using the operator ∗.

…

For example, the expression above would be written in Haskell as follows: f a b+c∗d Moreover, function application has higher priority than all other operators. For example, f a + b means (f a ) + b . The following table gives a few further examples to illustrate the differences between the notation for function application in mathematics and in Haskell: Mathematics Haskell f (x ) f (x , y ) f (g (x )) f (x , g (y )) f (x )g (y ) f f f f f x x y (g x ) x (g y ) x ∗g y Note that parentheses are still required in the Haskell expression f (g x ) above, because f g x on its own would be interpreted as the application of the function f to two arguments g and x , whereas the intention is that f is applied to one argument, namely the result of applying the function g to an argument x .

Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea

by

Charles Seife

Published 31 Aug 2000

December 31, 1999, is the evening when the great odometer in the sky clicks ahead. The Zeroth Number Waclaw Sierpinski, the great Polish mathematician…was worried that he’d lost one piece of his luggage. “No, dear!” said his wife. “All six pieces are here.” “That can’t be true,” said Sierpinski, “I’ve counted them several times: zero, one, two, three, four, five.” —JOHN CONWAY AND RICHARD GUY, THE BOOK OF NUMBERS It may seem bizarre to suggest that Dionysius and Bede made a mistake when they forgot to include zero in their calendar. After all, children count “one, two, three,” not “zero, one, two.” Except for the Mayans, nobody else had a year zero or started a month with day zero.

…

Worst of all, if you wantonly divide by zero, you can destroy the entire foundation of logic and mathematics. Dividing by zero once—just one time—allows you to prove, mathematically, anything at all in the universe. You can prove that 1 + 1 = 42, and from there you can prove that J. Edgar Hoover was a space alien, that William Shakespeare came from Uzbekistan, or even that the sky is polka-dotted. (See appendix A for a proof that Winston Churchill was a carrot.) Multiplying by zero collapses the number line. But dividing by zero destroys the entire framework of mathematics. There is a lot of power in this simple number. It was to become the most important tool in mathematics. But thanks to the odd mathematical and philosophical properties of zero, it would clash with the fundamental philosophy of the West.

…

Often the tone wobbled like a drunkard up and down the scale. To Pythagoras, playing music was a mathematical act. Like squares and triangles, lines were number-shapes, so dividing a string into two parts was the same as taking a ratio of two numbers. The harmony of the monochord was the harmony of mathematics—and the harmony of the universe. Pythagoras concluded that ratios govern not only music but also all other types of beauty. To the Pythagoreans, ratios and proportions controlled musical beauty, physical beauty, and mathematical beauty. Understanding nature was as simple as understanding the mathematics of proportions. Figure 7: The mystical monochord This philosophy—the interchangeability of music, math, and nature—led to the earliest Pythagorean model of the planets.

Turing's Vision: The Birth of Computer Science

by

Chris Bernhardt

Published 12 May 2016

Cellular automata We only looked briefly looked at cellular automata, but they have a long and interesting history. They were first studied by Ulam and von Neumann as the first computers were built. Nils Barricelli was at Princeton during the 1950s and used the computer to simulate the interaction of cells. George Dyson’s Turing’s Cathedral gives a good historical description of this work John Conway, in 1970, defined Life involving two-dimensional cellular automata. These were popularized by Martin Gardner in Scientific American. William Poundstone’s The Recursive Universe is a good book on the history of these automata and how complexity can arise from simple rules. (This book was first published in 1985, but was been republished by Dover Press in 2013.)

…

In particular, we will look at the rise of mathematical logic, the attempts to find a firm axiomatic foundation for mathematics, and the role of algorithms. Mathematical Certainty Mathematics is often seen as the epitome of certainty. If we can’t be certain of mathematical truths can we be certain of anything? However, in the history of mathematics there have been times when it looked as though the foundations were not secure and that the whole structure might collapse. Perhaps the first time that this feeling of uncertainty in mathematics occurred was in the fifth century BCE and, according to legend, resulted in the murder of Hippasus of Metapontum for proving a theorem.

…

Hilbert’s success with geometry naturally led to the question of whether the axiomatic method could be applied to the whole of mathematics. Could a list of axioms be found from which all of mathematics could be constructed? A number of people, including Hilbert and Russell, thought that this axiomatic approach should be possible. But before we look at what Russell, Hilbert, and others did, we need to talk a little about the development of mathematical logic. Boole’s Logic Logic has always been part of mathematics. Indeed, part of the reason the Elements was so influential, especially in education, was the approach that Euclid took. It was not just a list of mathematical results, but contained the logical arguments that showed how these results could be obtained from simpler ones.

Radical Technologies: The Design of Everyday Life

by

Adam Greenfield

Published 29 May 2017

Casey Newton, “Seattle dive bar becomes first to ban Google Glass,” CNET, March 8, 2013. 23.Dan Wasserman, “Google Glass Rolls Out Diane von Furstenberg frames,” Mashable, June 23, 2014. 4Digital fabrication 1.John Von Neumann, Theory of Self-Reproducing Automata, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1966, cba.mit.edu/events/03.11.ASE/docs/VonNeumann.pdf. 2.You may be familiar with cellular automata from John Conway’s 1970 Game of Life, certainly the best-known instance of the class. See Bitstorm.org, “John Conway’s Game of Life,” undated, bitstorm.org. 3.Adrian Bowyer, “Wealth Without Money: The Background to the Bath Replicating Rapid Prototyper Project,” February 2, 2004, reprap.org/wiki/Wealth_Without_Money; RepRap Project, “Cost Reduction,” December 30, 2014, reprap.org/wiki/Cost_Reduction.

…

And if it’s foolish to repose one’s trust in the governance of a nation state, isn’t it more foolish yet to let a currency’s valorization ride on the whims of virtually unaccountable institutional actors like the IMF? This certainly seems like something you’d want to avoid if you were going to redesign money from scratch. But what if the value of a currency could be founded on something other than hapless trust—something as coolly objective, rational, incorruptible and extrahistorical as mathematics itself? What if that same technique that let you do so could all at once eliminate any requirement for a central mint, resolve the double-spending problem, and provide for irreversible transactions? And what if it could achieve all this while preserving, if not quite the anonymity of participants, something very nearly as acceptable—stable pseudonymity?

…

The following account is greatly simplified—I’ve gone to some lengths to shield you from the implementation details of SHA-256 hashing, Merkle roots and so on—but it’s accurate in schematic. I hope it gives you a reasonably good feel for what’s going on, and for why it has its partisans and enthusiasts so excited. Every individual Bitcoin and every Bitcoin user has a unique identifier. This is its cryptographic signature, a mathematically verifiable proof of identity. Any given Bitcoin will always be associated with the signature of the user who holds it at that moment, and by stepping backward through time, we can also see the entire chain of custody that coin has passed through, from the moment it was first brought into being.

The AI-First Company

by

Ash Fontana

Published 4 May 2021

Agents follow programmed rules. Sometimes programming an agent requires expertise in a specific domain—understanding the “rules of the game,” or the principles of the system. Programmers create ABMs using techniques such as adversarial and reinforcement learning. Popular agent-based systems include some that play John Conway’s Game of Life and solve the prisoner’s dilemma. Financial and political institutions often use ABMs. For example, the Bank of England uses ABMs to model the impact of policy on property and credit markets. The effects of mergers and acquisitions on competition can be modeled effectively using simulation.

…

Each of the data and ML-specific roles tend to be filled by people with slightly different educational backgrounds than a traditional software engineer. Data analyst: master of business administration (MBA) or bachelor-level courses in statistics, econometrics, economics, mathematics, and other sciences. Data scientist: higher-level courses in statistics, mathematics, physics. Data engineer: computer science studies with a specialization in databases. Machine learning engineer: computer science studies and master-level studies in machine learning, mathematics, or physics. Data product manager: software product management and design management or project management. Data infrastructure engineer: higher-level computer science studies with a specialization in distributed systems.

…

Walter was particularly prodigious, invited to study at England’s Cambridge University when he was just twelve after mailing corrections to the great British philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell’s Principia Mathematica, a three-volume work on the foundations of mathematics. He ran away from home when he was fifteen to visit Russell at the University of Chicago and never saw his family again. Even though Warren was twenty-four years older than Walter, they spent a lot of time together across societies formed to understand the human mind and through institutions such as Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). They also drank a lot of whiskey together. Their partnership yielded an important model known as the threshold logic unit (TLU): a mathematical model of a human brain cell, or neuron, that explains how the brain computes things.

You Are Not a Gadget

by

Jaron Lanier

Published 12 Jan 2010

If you search online for math and ignore the first results, which are often the Wikipedia entry and its echoes, you start to come across weird individual efforts and even some old ThinkQuest pages. They were often last updated around the time Wikipedia arrived. Wikipedia took the wind out of the trend.* The quest to bring math into the culture continues, but mostly not online. A huge recent step was the publication of a book on paper by John Conway, Heidi Burgiel, and Chaim Goodman-Strauss called The Symmetries of Things. This is a tour de force that fuses introductory material with cutting-edge ideas by using a brash new visual style. It is disappointing to me that pioneering work continues primarily on paper, having become muted online.

…

It might become stuck as a fixture, like MIDI or the Google ad exchange services. That makes it important to be aware of what you might be missing. Even in a case in which there is an objective truth that is already known, such as a mathematical proof, Wikipedia distracts the potential for learning how to bring it into the conversation in new ways. Individual voice—the opposite of wikiness—might not matter to mathematical truth, but it is the core of mathematical communication. * See Norm Cohen, “The Latest on Virginia Tech, from Wikipedia,” New York Times, April 23, 2007. In 2009, Twitter became the focus of similar stories because of its use by protestors of Iran’s disputed presidential election

…

There’s an aversion to talking about it much, because we don’t want our founding father to seem like a tabloid celebrity, and we don’t want his memory trivialized by the sensational aspects of his death. The legacy of Turing the mathematician rises above any possible sensationalism. His contributions were supremely elegant and foundational. He gifted us with wild leaps of invention, including much of the mathematical underpinnings of digital computation. The highest award in computer science, our Nobel Prize, is named in his honor. Turing the cultural figure must be acknowledged, however. The first thing to understand is that he was one of the great heroes of World War II. He was the first “cracker,” a person who uses computers to defeat an enemy’s security measures.

I Am a Strange Loop

by

Douglas R. Hofstadter

Published 21 Feb 2011

Page 91 radicals, such as Évariste Galois… The great Galois was indeed a young radical, which led to his absurdly tragic death in a duel on his twenty-first birthday, but the phrase “solution by radicals” really refers to the taking of nth roots, called “radicals”. For a shallow, a medium, and a deep dip into Galois’ immortal, radical insights into hidden mathematical structures, see [Livio], [Bewersdorff ], and [Stewart], respectively. Page 95 there is a special type of abstract structure or pattern… “Real Patterns” in [Dennett 1998] argues powerfully for the reality of abstract patterns, based on John Conway’s cellular automaton known as the “Game of Life”. The Game of Life itself is presented ideally in [Gardner], and its relevance to biological life is spelled out in [Poundstone].

…

kits, electronic KJ, Himalayan peak, unscalability of Klagsbrun, Francine Klee, Paul Klüdgerot, the Klüdgerotic condition knees: awareness level of; as candidates for consciousness; reflex behavior of knobs of Twinwirld knowing, elusive nature of knurking and glebbing; not physical processes but subjective sensations; reliably evoked independently of brain’s wiring koans Kolak, Daniel Krall, Diana Kriegel, Uriah Külot, Gerd, drama critic, review of Prince Hyppia: Math Dramatica by L lambs as edible beings landmark integers language: acquisition of; as unperceived code; without self-reference “language”, vagueness of the term lap loop; photo of large-souled vs. small-souled beings Latin leaf piles: as endowed with Leafpilishness; intrinsic nature of; as macroscopic entities Leafpilishness, Capitalized Essence of leather, purchase of leatherette dashboard Leban, Roy and Bruce leg that is asleep Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm von Le Lionnais, François Leonardo di Pisa (Fibonacci) letters of the alphabet, as meaningless level-confusion, prevalence of, in discussions of brain/mind level-crossing feedback loops level-shifts, perceptual levels of description: causality at different; oscillation between Lexington (in “Pig”) liar paradox liberty and imprisonment as flipped sensations life: defined; as illusion; in Universe Z Life, John Conway’s Game of “light on inside”; suddenly extinguished linguistic sloppiness in reference to robots Linus (“Peanuts”) lions: compassion of; conscience of; possible vegetarianism of liphosophy lists: abstract patterns having great reality for us; abstractions in brain having causal powers; accidental attachments of Leafpilishness dollops; actions launched by self; brain structures, in descending order; Carol’s losses; causes and effects; composers whose style the author borrowed from; concepts in canine minds; concepts involved in “grocery store checkout stand”; concepts involved in “soap digest rack”; conscious entities, according to panpsychists; copycat actions by the author; determining factors of identity; emotionladen verbs; entities without selves; epiphenomena at human size; episodes in one’s memory; famous achievements influencing the author; high-level causal agents; high-level phenomena in brain; high-level phenomena in mind; ideas beyond Ollie’s ken; importable mannerisms of other people; items of dubious reality in newspaper; items in hog’s environment; leaf-pile enigmaslist of principal lists in I Am a Strange Loop; low-level phenomena in brain; macroscopic reliabilities; macroscopic unpredictables; magnanimous souls; memories from Carol’s youth; mentalistic verbs; mundane concepts beginning with “s”; mythical symbols; names morphing from “Derek Parfit” to “Napoleon Bonaparte”; objects of study in literary criticism; obstacles that crop up at random in life; Parfit book’s chapter titles; people with diverse influences on the author; phrases denying interpenetration of souls; physical phenomena that lack consciousness; physical structures lacking hereness; potential personal attributes; potential symbols in mosquito brain; problems with Consciousness as a Capitalized Essence; prototypically true sentences; qualia; questions triggered by Gödel’s theorem; rarely thought-of things; realest things of all; recipients of dollops of Consciousness; scenic events perceived by no one; self-referential sentences; shadowy abstract patterns in brain; simultaneous experiences in one brain; small-souled beings; stuff without inner light; synonyms for “consciousness”; synonyms for “eagerness”; things I wasn’t but could imagine being; things of unclear reality beginning with “g”; traits of countries; unlikely substrates for “I”ness; video-feedback epiphenomena; video-feedback knobs; what makes the world go round; words with ill-defined syllable-counts; words for linguistic phenomena literary criticism, objects of study in Little Tyke, allegedly vegetarian lion living inside someone else; see also survival; visitation Löb, Martin Hugo locking-in: of epiphenomena on TV screen: of “I”; of perceptions; of self lockstep synchrony of Gödel numbers and PM formulas logic of simmballs’ dance Logical Syntax of Language, The (Carnap) logicians’ use of blurry concepts long sentence loophole in set theory, Russell’s love: for children leading to soul-entanglement; halo of concepts with which we understand love; as cause for marriage; inseparability from “I” concept; poorly understood so far in terms of quantum electrodynamics; profound influence on us of those whom we “lower” animals, see hierarchy lower-level events, see substrate lower-level meaning of Gödel’s formula; ignoring of low-level view of brains low notes gliding into rumbles low-resolution copies, see fidelity Lucas, see Natalie Lucy (“Peanuts”) M Machine Q vs.

…

You might object, “But those aren’t mathematical notions! Berry’s idea was to use mathematical definitions of integers.” All right, but then show me a sharp cutoff line between mathematics and the rest of the world. Berry’s definition uses the vague notion of “syllable counting”, for instance. How many syllables are there in “finally” or “family” or “rhythm” or “lyre” or “hour” or “owl”? But no matter; suppose we had established a rigorous and objective way of counting syllables. Still, what would count as a “mathematical concept”? Is the discipline of mathematics really that sharply defined? For instance, what is the precise definition of the notion “magic square”?

The Genius Within: Unlocking Your Brain's Potential

by

David Adam

Published 6 Feb 2018

If certain anchor points – Christmas Day in 2000 was a Monday – can be remembered, this provides a platform to work out the rest. Mathematicians have produced various algorithms to mimic the calendar-counting skill of savants. One was Lewis Carroll, author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which itself contains many maths references and in-jokes. Another is John Conway, perhaps best known for inventing what is known as Conway’s ‘Game of Life’ – a simple simulation of evolution and development called a cellular automaton, which spawned several generations of life simulation games, such as ‘SimCity’ and the rest. In theory, most people could learn to use these anchor points and calculations to identify days from dates, at least for a span of a few decades.

…

‘tentative signs’, Howard R. (2005), ‘Objective evidence of rising population ability: a detailed examination of longitudinal chess data’, Personality and Individual Differences 38, pp. 347–363. ‘doomed to idiocy’, Woodley M. et al. (2013), ‘Were the Victorians cleverer than us? The decline in general intelligence estimated from a metaanalysis of the slowing of simple reaction time’, Intelligence 41 (6), pp. 843–850. ‘mathematics’, Blair C. et al. (2005), ‘Rising mean IQ: cognitive demands of mathematics education for young children, population exposure to formal schooling, and the neurobiology of the prefrontal cortex’, Intelligence 33, pp. 93–106. ‘smartest humans’, Hsu S. (2014), ‘Super-intelligent humans are coming’, Nautilus, 16 October. ‘genetic tweaks’, Hsu S. (2014), ‘On the genetic architecture of intelligence and other cognitive traits’, arXiv:1408.3421v2, 30 August.

…

Mapping and understanding brain function and how it can be changed is a frontier of modern neuroscience, the defining discipline of this twenty-first century. And it comes down to connections. Just as the ancients imposed patterns and pictures onto the randomness of the stars, so the brain relies on circuits, sequences and constellations of activity to produce co-ordination and cognition from its billions of individual cells. From memories and mathematics to grief, insight and genius, all of it is formed from the way brain cells make and break links with their neighbours, and how they use these links to communicate. And here’s the kicker: science now has the tools to manipulate and to strengthen those links on demand. Modern brain science is not just about observing any more.

Free as in Freedom

by

Sam Williams

Published 16 Nov 2015

And there was Bill Gosper, the in-house math whiz already in the midst of an 18-month hacking bender triggered by the philosophical implications of the computer game LIFE.See Steven Levy, Hackers (Penguin USA [paperback], 1984): 144. Levy devotes about five pages to describing Gosper's fascination with LIFE, a math-based software game first created by British mathematician John Conway. I heartily recommend this book as a supplement, perhaps even a prerequisite, to this one. Members of the tight-knit group called themselves " hackers." Over time, they extended the "hacker" description to Stallman as well. In the process of doing so, they inculcated Stallman in the ethical traditions of the "hacker ethic ."

…

Like most members of the Science Honors Program, Stallman breezed through the qualifying exam for Math 55, the legendary "boot camp" class for freshman mathematics "concentrators" at Harvard. Within the class, members of the Science Honors Program formed a durable unit. "We were the math mafia," says Chess with a laugh. "Harvard was nothing, at least compared with the SHP." To earn the right to boast, however, Stallman, Chess, and the other SHP alumni had to get through Math 55. Promising four years worth of math in two semesters, the course favored only the truly devout. "It was an amazing class," says David Harbater, a former "math mafia" member and now a professor of mathematics at the University of Pennsylvania.

…

As a kid who'd always taken pride in being the smartest mathematician the room, it was like catching a glimpse of his own mortality. Years later, as Chess slowly came to accept the professional rank of a good-but-not-great mathematician, he had Stallman's sophomore-year proof to look back on as a taunting early indicator. "That's the thing about mathematics," says Chess. "You don't have to be a first-rank mathematician to recognize first-rate mathematical talent. I could tell I was up there, but I could also tell I wasn't at the first rank. If Richard had chosen to be a mathematician, he would have been a firstrank mathematician." For Stallman, success in the classroom was balanced by the same lack of success in the social arena.

Fermat’s Last Theorem

by

Simon Singh

Published 1 Jan 1997

The hours I spent quizzing and chatting with them were enormously enjoyable and I appreciate their patience and enthusiam while explaining so many beautiful mathematical concepts to me. In particular I would like to thank John Coates, John Conway, Nick Katz, Barry Mazur, Ken Ribet, Peter Sarnak, Goro Shimura and Richard Taylor. I have tried to illustrate this book with as many portraits as possible to give the reader a better sense of the characters involved in the story of Fermat’s Last Theorem. Various libraries and archives have gone out of their way to help me, and in particular I would like to thank Susan Oakes of the London Mathematical Society, Sandra Cumming of the Royal Society and Ian Stewart of Warwick University.

…

Russell’s work shook the fundations of mathematics and threw the study of mathematical logic into a state of chaos. The logicians were aware that a paradox lurking in the foundations of mathematics could sooner or later rear its illogical head and cause profound problems. Along with Hilbert and the other logicians, Russell set about trying to remedy the situation and restore sanity to mathematics. This inconsistency was a direct consequence of working with the axioms of mathematics, which until this point had been assumed to be self-evident and sufficient to define the rest of mathematics. One approach was to create an additional axiom which forbade any class from being a member of itself.

…

An account of Fermat’s Last Theorem, written prior to the work of Andrew Wiles, aimed at graduate students. Mathematics: The Science of Patterns, by Keith Devlin, 1994, Scientific American Library. A beautifully illustrated book which conveys the concepts of mathematics through striking images. Mathematics: The New Golden Age, by Keith Devlin, 1990, Penguin. A popular and detailed overview of modern mathematics, including a discussion on the axioms of mathematics. The Concepts of Modem Mathematics, by Ian Stewart, 1995, Penguin. Principia Mathematica, by Betrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead, 3 vols, 1910, 1912, 1913, Cambridge University Press.

The Demon in the Machine: How Hidden Webs of Information Are Finally Solving the Mystery of Life

by

Paul Davies

Published 31 Jan 2019

But a solitary replicating interstellar predator may be a different story altogether. LIFE AS A GAME Although von Neumann didn’t attempt to build a physical self-reproducing machine, he did devise a clever mathematical model that captures the essential idea. It is known as a cellular automaton (CA), and it’s a popular tool for investigating the link between information and life. The best-known example of a CA is called, appropriately enough, the Game of Life, invented by the mathematician John Conway and played on a computer screen. I need to stress that the Game of Life is very far removed from real biology, and the word ‘cell’ in cellular automata is not intended to have any connection with living cells – that’s just an unfortunate terminological coincidence.

…

Hilbert used the occasion to outline his favourite unanswered mathematical problems. The most profound of these concerned the internal consistency of the subject itself. At root, mathematics is nothing but an elaborate set of definitions, axiomsfn1 and the logical deductions flowing from them. We take it for granted that it works. But can we be absolutely rock-solidly sure that all pathways of reasoning proceeding from this austere foundation will never result in a contradiction? Or simply fail to produce an answer? You might be wondering, Who cares? Why does it matter whether mathematics is consistent or not, so long as it works for practical purposes?

…

Such was the mood in 1928, when the problem was of interest to only a handful of logicians and pure mathematicians. But all that was soon to change in the most dramatic manner. The issue as Hilbert saw it was that, if mathematics could be proved consistent in a watertight manner, then it would be possible to test any given mathematical statement as either true or false by a purely mindless handle-turning procedure, or algorithm. You wouldn’t need to understand any mathematics to implement the algorithm; it could be carried out by an army of uneducated employees (paid calculators) or a machine, cranking away for as long as it took. Is such an infallible calculating machine possible?

What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of Computing

by

Ed Finn

Published 10 Mar 2017

Describing organisms as information also suggests the opposite, that information has a will to survive, that as Stewart Brand famously put it, “information wants to be free.”36 Like Neal Stephenson’s programmable minds, like the artificial intelligence researchers who seek to model the human brain, this notion of the organism as message reframes biology (and the human) to exist at least aspirationally within the boundary of effective computability. Cybernetics and autopoiesis lead to complexity science and efforts to model these processes in simulation. Mathematician John Conway’s game of life, for example, seeks to model precisely this kind of spontaneous generation of information, or seemingly living or self-perpetuating patterns, from simple rule-sets. It, too, has been shown to be mathematically equivalent to a Turing machine, and indeed mathematician Paul Rendell designed a game of life that he proved to be Turing-equivalent (figure 1.1).37 Figure 1.1 “This is a Turing Machine implemented in Conway’s Game of Life.”

…

The thesis uses this informal definition to unite three different rigorous mathematical theses about computation (Turing machines, Church’s lambda calculus, and mathematician Kurt Gödel’s concept of recursive functions), translating their specific mathematical claims into a more general boundary statement about the limits of computational abstraction. In another framing, as David Berlinski argues in his mathematical history The Advent of the Algorithm, the computability boundary that Turing, Gödel, and Church were wrestling with was also an investigation into the deep foundations of mathematical logic.20 Gödel proved, to general dismay, that it was impossible for a symbolic logical system to be internally consistent and provable using only statements within the system.

…

This was a limited instance of the broader cognition and mind debates Clark’s “extended mind” hypothesis sparked decades later—an examination of the relationship between cognition and the tools of cognition, grounded here in terms of mathematical truth and provability. It was a debate about the nature of our dependence on mathematical language and the ways that choices of language, the affordances of different symbolic systems, could foreclose access to other means of understanding. Gödel’s incompleteness theorem definitively answered a fundamental, existential question (is there a logical and complete mathematical language?) with a firm negative. He demonstrated that no mathematical language whose statements are effectively calculable can both prove all true statements about natural numbers and remain logically consistent.

Protocol: how control exists after decentralization

by

Alexander R. Galloway

Published 1 Apr 2004

He writes: “I proposed to create a very large, complex and inter-connected region of cyberspace that will be inoculated with digital organisms which will be allowed to evolve freely through natural selection”94—the goal of which is to model the 92. For other examples of artificial life computer systems, see Craig Reynolds’s “boids” and the flocking algorithm that governs their behavior, Larry Yaeger’s “Polyworld,” Myron Krüger’s “Critter,” John Conway’s “Game of Life,” and others. 93. Tom Ray, “What Tierra Is,” available online at http://www.hip.atr.co.jp/~ray/tierra/ whatis.html. 94. Tom Ray, “Beyond Tierra: Towards the Digital Wildlife Reserve,” available online at http://www1.univap.br/~pedrob/PAPERS/FSP_96/APRIL_07/tom_ray/node5.html. Power 109 spontaneous emergence of biodiversity, a condition believed by many scientists to be the true state of distribution of genetic information in a Nature that is unencumbered by human intervention.

…

Truly distributed networks cannot, in fact, support all-channel communication (a combinatorial utopia), but instead propagate through outages and uptimes alike, through miles of dark fiber (Lovink) and data oases, through hyperskilled capital and unskilled laity. Thus distribution is similar to but not synonymous with allchannel, the latter being a mathematical fantasy of the former. Chapter 1 32 bureaucracies and vertical hierarchies toward a broad network of autonomous social actors. As Branden Hookway writes: “The shift is occurring across the spectrum of information technologies as we move from models of the global application of intelligence, with their universality and frictionless dispersal, to one of local applications, where intelligence is site-specific and fluid.”5 Computer scientists reference this historical shift when they describe the change from linear programming to object-oriented programming, the latter a less centralized and more modular way of writing code.

…

Whenever a packet is created via fragmentation, certain precautions must be taken to make sure that it will be reassembled correctly at its destination. To this end, a header is attached to each packet. The header contains certain pieces of vital information such as its source address and destination address. A mathematical algorithm or “checksum” is also computed and amended to the header. If the destination computer determines that the information in the header is corrupted in any way (e.g., if the checksum does not correctly correlate), it is obligated to delete the packet and request that a fresh one be sent.

The Creativity Code: How AI Is Learning to Write, Paint and Think

by

Marcus Du Sautoy

Published 7 Mar 2019

I first discovered Go when I visited the mathematics department at Cambridge as an undergraduate to explore whether to do my PhD with the amazing group that had helped complete the classification of finite simple groups, a sort of Periodic Table of Symmetry. As I sat talking to John Conway and Simon Norton, two of the architects of this great project, about the future of mathematics, I kept being distracted by students at the next table furiously slamming black and white stones onto a large 19×19 grid carved into a wooden board. Eventually I asked Conway what they were doing. ‘That’s Go. It’s the oldest game that is still being played to this day.’ In contrast to the war-like quality of chess, he explained, Go was a game of territory.

…

That is why we obsessively try to build a sequence of mathematical moves to link the conjectured endgame to legitimate games established to date. But what is it that has driven humans to want to find these proofs? Where has the human urge come from to create mathematics? Is this motivation to explore the mathematical terrain one we will need to program into algorithms that will challenge mathematicians at their own game? The origins of mathematics, of course, go back to human attempts to understand the environment we live in, to make predictions about what might happen next, to mould our environment to our advantage. Mathematics is an act of survival by the human species.

…

As Hilbert explained, you don’t have to know what the symbols mean to be able to construct mathematical proofs. So doesn’t this seem like something perfectly conceived for a computer to engage in? Every time a mathematician takes an established mathematical statement and plays an allowed logical step, the new sequence of symbols represents a freshly established mathematical statement. It’s possible that it’s already on the list of mathematical proven statements because we came on it via a different route. But this is nonetheless a way for a mathematician (or a computer) to start generating new theorems out of old ones. Isn’t that the goal? Mathematics may not be about doing calculations, but on this score hasn’t the computer already put the mathematician out of a job if I can just press go and it starts spewing out logical consequences of all known statements?

The Deep Learning Revolution (The MIT Press)

by

Terrence J. Sejnowski

Published 27 Sep 2018

Cellular automata typically have only a few discrete values that evolve in time, depending on the states of the other cells. One of the simplest cellular automata is a one-dimensional array of cells, each with value of 0 or 1 (box 13.1). Perhaps the most famous cellular automaton is called the “Game of Life,” which was invented by John Conway, the John von Neumann professor of mathematics at Princeton, in 1968, popularized by Martin Gardner in his “Mathematical Games” column in Scientific American, and is illustrated in figure 13.2. The board is a two-dimensional array of cells that can only be “on” or “off” and the update rule only depends on the four nearest neighbors. On each time step, all the states are updated.

…

A simpler version of this idea goes back to Hedy Lamarr (figure 15.4), a movie actress and inventor who, in 1941, shared the patent on frequency hopping, which she developed as a secure communication system for the military during World War II.4 When Sol Golomb left JPL to join the faculty at the University of Southern California, Ed Posner took over his group, the same Ed Posner who founded NIPS, but Golomb continued to support his former JPL group with advice. The mathematics behind shift register sequences is a deep part of number theory. When Golomb received his doctorate from Harvard, his doctoral advisor, and most mathematicians at that time, were proud to believe that pure mathematics would never have any practical applications. This view was shared by G. H. Hardy, a Cambridge don whose influential book A Mathematician’s Apology5 declared that “good” mathematics had to be pure and that applied mathematics was “uninteresting.” But mathematics is what it is, neither pure nor applied. Some mathematicians may want their mathematics to be pure, but they can’t stop it from solving practical problems in the real world.

…

Every time you use your cell phone you are using his mathematical codes. Courtesy of the University of Southern California. abstract area of mathematics, he took a job at Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where he was head of the communications group and worked on space communications. Deep space probes were being sent out to the far reaches of the solar system, but the signals coming back were weak and noisy. Shift register sequences and error-correcting codes greatly improved communication with space probes, and the same mathematics laid the foundation for modern digital communications.

Marx at the Arcade: Consoles, Controllers, and Class Struggle

by

Jamie Woodcock

Published 17 Jun 2019

Shannon, “Programming a Computer for Playing Chess,” Philosophical Magazine 41, no. 314 (1950). 26Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, xxix. 27Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 7. 28“Video Game History Timeline.” 29“Video Game History Timeline.” 30“Video Game History Timeline.” 31Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 7. 32Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 7. 33Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 8. 34Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 9. 35Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 9. 36Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 8. 37“Video Game History Timeline.” 38“Video Game History Timeline.” 39Martin Gardner, “Mathematical Games: The Fantastic Combinations of John Conway’s New Solitaire Game ‘Life,’” Scientific American 223 (1970): 120–23. 40“Video Game History Timeline.” 41“Video Game History Timeline.” 42Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 11. 43Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, Games of Empire, 12. 44John J. Anderson, “Dave Tells Ahl: The History of Creative Computing,” Creative Computing 10, no. 11 (1984). 45“AtGames to Launch Atari Flashback® 4 to Celebrate Atari’s 40th Anniversary!”

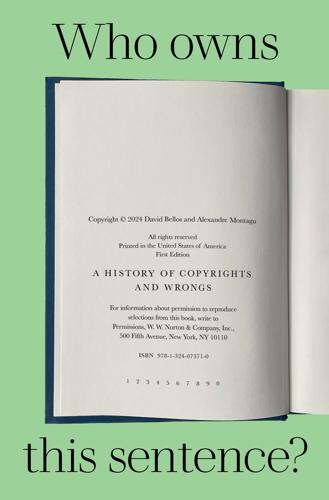

Who Owns This Sentence?: A History of Copyrights and Wrongs

by

David Bellos

and

Alexandre Montagu

Published 23 Jan 2024

Why then do mathematicians not merely work hard but make advances that are fundamental to inventions in all other fields, from ride-hailing apps to nuclear science, computing and space flight? Does mathematicians’ immunity to the incentive effect make them unlike other human beings? Surely not. Mersenne, Newton, Gauss, Einstein and John Conway were no more exempt than others from gambling debts, divorce settlements and forced exile. They had as much need of money as the next man – but they did not solve their financial problems by claiming property rights in their discoveries. Mathematics provides such a glaring exception to the claimed relationship between incentive and creativity as to make it untenable. The justification of intellectual property as an incentive to creation also rests on a dim view of the human qualities of writers, artists and inventors.

…

In France, the same broad idea found expression in the Encyclopédie, the first great attempt to put all the world’s knowledge in alphabetical order. The entry on génie lists the pursuits where “men of genius” could be found, not just the arts and sciences, but also business and statecraft – though curiously enough, mathematics is not mentioned. Like Edward Young, the writer of this encyclopaedia entry does not claim that geniuses were masters of their craft: they could make mistakes and ignore the rules of taste, but wherever such creators came forth, they changed the “nature of things”. His character spreads to everything he touches; and his mind, leaping beyond past and present, illuminates the future: he goes beyond his own time, which can but follow in his steps.37 This looks very much like the explanation of a later Romantic trope – the penniless, yet-to-be acknowledged genius writing verse by candlelight to keep a dying lover warm (the main subject of La Bohème, after all).

…

The flurry of teenage tinkering fuelled by such hopes occasionally results in a worthwhile advance, but in practice, almost all serious inventors have salaried jobs in universities, research labs, government departments or corporations. There are some fundamental pursuits that have never been covered by patent or copyright protection, the most important among them being mathematics. The exclusion of maths from the domain of property rests on the distinction made at the very start of modern intellectual property regimes between facts of nature and created work: Scientia donum dei est, unde vendi non potest. It has always been held that things that exist in nature cannot be owned, and until very recently, it has been held that the discoveries of mathematicians are not their inventions, but revelations of the Platonic order of the world.

Prime Obsession:: Bernhard Riemann and the Greatest Unsolved Problem in Mathematics

by

John Derbyshire

Published 14 Apr 2003

It is said to have inspired the tragic Évariste Galois—the narrator in Tom Petsinis’s novel The French Mathematician—to take up a career in mathematics. More relevant to the present narrative, his book Theory of Numbers—the renamed third edition of the Essay mentioned in the text—was lent by a schoolmaster to the adolescent Bernhard Riemann, who returned it in less than a week with the comment, “This is truly a wonderful book; I know it by heart.” The book has 900 pages. 19. There is a very good account of the Euler-Mascheroni number in Chapter 9 of The Book of Numbers, by John Conway and Richard Guy. PRIME OBSESSION 370 Though I have not described it properly in this book, the very observant reader will glimpse the Euler-Mascheroni number in Chapter 5. 20.

…

Some of the most important theorems of twentieth-century mathematics were concerned with the completeness of mathematical systems (Kurt Gödel, 1931) and the decidability of mathematical propositions (Alonzo Church, 1936). 196 PRIME OBSESSION These momentous developments have not yet, even at the opening of the twenty-first century, been reflected in mathematics education, at least up to college-entrance level. Perhaps they cannot be. Mathematics is a cumulative subject. Every new discovery adds to the body of knowledge, and nothing is ever subtracted. When a mathematical truth has been discovered it is there forever, and every succeeding generation of students must learn it.

…

The ideas contained in this paper were so advanced that it was decades before they became fully 128 PRIME OBSESSION accepted, and 60 years before they found their natural physical application, as the mathematical framework for Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity. James R. Newman, in The World of Mathematics, refers to the paper as “epoch-making” and “imperishable” (but fails to include it in his huge anthology of classic mathematical texts). And the astonishing thing is that the paper contains almost no mathematical symbolism. Leafing through it, I see five equals signs, three square root signs and four Σ signs—an average of fewer than one symbol per page! There is just one real formula.

The Man From the Future: The Visionary Life of John Von Neumann

by

Ananyo Bhattacharya

Published 6 Oct 2021

‘John von Neumann, he absolutely didn’t see this,’ Wolfram says, insisting that he was the first to truly understand that enormous complexity can spring from automata. ‘John Conway, same thing.’51 A New Kind of Science is a beautiful book. It may prove in time also to be an important one. The jury, however, is still very much out. Whatever the ultimate verdict of his peers, Wolfram had succeeded in putting cellular automata on the map like no one else. His groundwork would help spur those who saw automata not just as crude simulations of life, but as the primitive essence of life itself. ‘If people do not believe that mathematics is simple,’ von Neumann once said, ‘it is only because they do not realize how complicated life is.’52 He was fascinated by evolution through natural selection, and some of the earliest experiments on his five-kilobyte IAS machine involved strings of code that could reproduce and mutate like DNA.

…

In 1928, he challenged his followers to prove that mathematics is complete, consistent and decidable. By complete, Hilbert meant that all true mathematical theorems and statements can be proved from a finite set of axioms. By consistent, he was demanding a proof that the axioms would not lead to any contradictions. The third of Hilbert’s demands, that mathematics should be decidable, became widely known as the Entscheidungsproblem: is there a step-by-step procedure (an algorithm) that can be used to show whether or not any particular mathematical statement can be proved? Mathematics would only be truly safe, said Hilbert, when, as he expected, all three of his demands were met.

…

Only on the last day of the conference, towards the end of a roundtable discussion that would bring the meeting to a close, did Gödel play it. In a single sentence, he quietly reduced the earlier proceedings of the conference to an irrelevance and the foundations of mathematics to a flaming ruin. ‘One can,’ he ventured modestly, ‘even give examples of propositions (and in fact of those of the type of Goldbach or Fermat) that, while contentually true, are unprovable in the formal system of classical mathematics.’ In other words, there are truths in mathematics that cannot be proven by mathematics. Mathematics is not complete. His off-hand references to Goldbach and Fermat were portentous. Golbach’s conjecture (that all even numbers greater than 2 are the sum of two primes) and Fermat’s last theorem (that no positive integers a, b, and c satisfy the equation an + bn = cn for values of n greater than 2) were two of the great unsolved problems in arithmetic.22 Gödel was implying that even in the sort of maths taught to schoolchildren there might lurk verities that can never be substantiated.

Advances in Artificial General Intelligence: Concepts, Architectures and Algorithms: Proceedings of the Agi Workshop 2006

by

Ben Goertzel

and

Pei Wang

Published 1 Jan 2007