Longitude

by

Dava Sobel

Published 1 Jan 1995

Admiral Lord Anson. London: Cassell, 1960. Quill, Humphrey. John Harrison, the Man Who Found Longitude. London: Baker, 1966. —. John Harrison, Copley Medalist, and the £20,000 Longitude Prize. Sussex: Antiquarian Horological Society, 1976. Randall, Anthony G. The Technology of John Harrison’s Portable Timekeepers. Sussex: Antiquarian Horological Society, 1989. Vaughn, Denys, ed. The Royal Society and the Fourth Dimension: The History of Timekeeping. Sussex: Antiquarian Horological Society, 1993. Whittle, Eric S. The Inventor of the Marine Chronometer: John Harrison of Foulby. Wakefield, England: Wakefield Historical Publications, 1984.

…

The 1707 incident, so close to the shipping centers of England, catapulted the longitude question into the forefront of national affairs. The sudden loss of so many lives, so many ships, and so much honor all at once, on top of centuries of previous privation, underscored the folly of ocean navigation without a means for finding longitude. The souls of Sir Clowdisley’s lost sailors— another two thousand martyrs to the cause—precipitated the famed Longitude Act of 1714, in which Parliament promised a prize of £20,000 for a solution to the longitude problem. In 1736, an unknown clockmaker named John Harrison carried a promising possibility on a trial voyage to Lisbon aboard H.M.S.

…

When he had thought out the novel contraption to his own satisfaction, which took him almost four years, he set off for London—a journey of two hundred miles—to lay his plan before the Board of Longitude. 8. The Grass hopper Goes to Sea Where in this small-talking world can I find A longitude with no platitude? —CHRISTOPHER FRY, The Lady’s Not for Burning When John Harrison arrived in London in the summer of 1730, the Board of Longitude was nowhere to be found. Although that august body had been in existence for more than fifteen years, it occupied no official headquarters. In fact, it had never met. So indifferent and mediocre were the proposals submitted to the board, that individual commissioners had simply sent out letters of rejection to the hopeful inventors.

The Perfectionists: How Precision Engineers Created the Modern World

by

Simon Winchester

Published 7 May 2018

.* And none was more sedulously dedicated to achieving this degree of exactitude than the Yorkshire carpenter and joiner who later became England’s, perhaps the world’s, most revered horologist: John Harrison, the man who most famously gave mariners a sure means of determining a vessel’s longitude. This he did by painstakingly constructing a family of extraordinarily precise clocks and watches, each accurate to just a few seconds in years, no matter how sea-punished its travels in the wheelhouse of a ship. An official Board of Longitude was set up in London in 1714, and a prize of twenty thousand pounds offered to anyone who could determine longitude with an accuracy of thirty miles. It was John Harrison who, eventually and after a lifetime of heroic work on five timekeeper designs, would claim the bulk of the prize.

…

Over the entire 147 days of a voyage that involved a complex and unsettling stormy return journey (in which William Harrison had to swaddle the timekeeper in blankets), the watch error was just 1 minute 54.5 seconds, a level of accuracy never imagined for a seaborne timekeeping instrument. And while it would be agreeable to report that John Harrison then won the prize for his marvelous creation, much has been made of the fact that he did not. The Board of Longitude prevaricated for years, the Astronomer Royal of the day declaring that a much better way of determining longitude, known as the lunar distance method, was being perfected, and that there was therefore no need for sea clocks to be made. Poor John Harrison, therefore, had to visit King George III (a great admirer, as it happens) to ask him to intercede on his behalf.

…

So the decision of the observatory principals over the years has been to keep this one masterpiece in its quasi-virgin state, much like the unplayed Stradivarius violin at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford,* as an untouched testament to its maker’s art. And what sublime pieces of mechanical art John Harrison made! By the time he decided to throw his hat in the ring for the longitude prize, he had already constructed a number of fine and highly accurate timekeepers—most of them pendulum clocks for use on land, many of them long-case clocks, each one more refined than the last. Harrison’s skills lay in the imaginative improvement of his timekeepers, rather than in the decorative embellishment that many of his eighteenth-century contemporaries were known for.

About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks

by

David Rooney

Published 16 Aug 2021

In March 1714, during her speech at the state opening of Britain’s Parliament, Queen Anne exclaimed that “this Country can Flourish only by Trade; and will be most Formidable, by the right Application of our Naval Force.”12 The following month a group of merchants and sea captains responded to her call with a petition to the government, in which they said that: nothing can be either at home or abroad, more for the common Benefit of Trade and Navigation, than the Discovery of the Longitude at Sea which has been so long desired in vain, and for want of which so many Ships and Men have been lost.13 The answer, they said, was a reward scheme, and just three months later the government passed an act founding a Board of Longitude that offered £20,000 to anybody who could solve the problem to half a degree. It took half a century for the British prize fund to bear fruit, and then it did so twice. By the late 1750s, John Harrison had completed a mechanical timekeeper (later known as a chronometer) that kept time well enough to win the reward money and coped with the rough conditions at sea.

…

She was instantly laid down on her side, the quarter-deck guns driven furiously over-board, and the sails in a moment split to pieces.3 Yet there was no alternative, because suitable ports were in short supply on Africa’s southern coastline. Navigating safely round the continent demanded the highest skill and the best technology and, by the time the British planted their flag on the Cape, the best navigational technology meant marine chronometers, highly accurate timekeepers first developed by John Harrison in the 1750s, that offered a fixed time reference from which longitude could be calculated once at sea. Crucial to the process of chronometer navigation was access to accurate time signals during stays in ports, so that officers could check their shipboard chronometers and set them to time. And in an age before radio, these coastal time signals themselves needed access to accurate time, either from a nearby astronomical observatory or, as electric telegraph networks began to be built from the 1840s onward, from a telegraph time service that linked back to an observatory elsewhere.

…

Once Ernst Jechart and Gerhard Hübner’s miniature atomic clocks became available in 1972, it seemed that the problem had been solved, and the 1974 NTS-1 satellite trial that carried their clocks went well. But engineers knew that the clocks destined for GPS satellites would need to be much more rugged to keep ticking without fail for years on end as the satellites orbited Earth. It was like the eighteenth-century longitude problem all over again. Then, John Harrison had to find ways to miniaturize existing timekeeping technology while also increasing its accuracy, precision and long-term reliability. At the same time, he needed to harden his new timekeepers against the hostile conditions of a long sea voyage such as violent movement and temperature fluctuations.

Future Perfect: The Case for Progress in a Networked Age

by

Steven Johnson

Published 14 Jul 2012

Countless stories of innovation from the period involve a prize-backed challenge. During the century that followed that first coffeehouse meeting, the RSA alone disbursed what would amount to tens of millions of dollars in today’s currency. John Harrison’s invention of the chronometer, which revolutionized the commercial and military fleets of the day, was sparked by the celebrated Longitude Prize, offered by the Board of Longitude, a small government body that had formed with the express intent of solving the urgent problem of enabling ships to establish their longitudinal coordinates while at sea. Not all premiums were admirable in their goals: William Bligh’s ill-fated expedition to Tahiti aboard the Bounty began with an RSA premium awarded to anyone who could successfully transport the versatile breadfruit plant to the West Indies to feed the growing slave populations there.

…

Once a premium had been established—and the reward publicly announced—the prize money created a much larger pool of minds working on the problem. John Harrison’s story, powerfully recounted in Dava Sobel’s bestselling Longitude, demonstrates how a prize-backed challenge extends and diversifies the network of potential solutions. Born in West Yorkshire, Harrison was the son of a carpenter, with almost no formal education, and notoriously poor writing skills. When he began working on his first iteration of the chronometer, his social connections to the elites of London were nonexistent. But the £20,000 offered by the Board of Longitude caught the attention of his brilliant mechanical mind.

…

On the innovation threat posed by intellectual property restrictions, see Lawrence Lessig’s The Future of Ideas, and my own Where Good Ideas Come From. Ayn Rand’s views on patents come from an essay, “Patents and Copyrights,” included in the collection Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal. John Harrison’s story is told in Dava Sobel’s popular Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time. Beth Noveck’s inspirational work with crowdsourced patent review, dubbed “peer to patent,” is described in her WikiGovernment. For more on Jon Schnur and the origin and implementation of the Race to the Top program, see Steve Brill’s entertaining Class Warfare: Inside the Fight to Fix America’s Schools.

Sextant: A Young Man's Daring Sea Voyage and the Men Who ...

by

David Barrie

Published 12 May 2014

Voyage de La Pérouse autour du monde. 4 vols and atlas. Paris: Imprimerie de la République. Mixter, G. W. (1960). Primer of Navigation (4th ed.). Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand. Norie, J. W. (1839). A Complete Epitome of Practical Navigation. London: J. W. Norie. Quill, H. (1966). John Harrison: The Man Who Found Longitude. London: John Baker. Raban, J. (2000). Passage to Juneau: A Sea and Its Meanings. London: Picador Raper, L. H. (1840). The Practice of Navigation and Nautical Astronomy. London: R. B. Bate. Ritchie, R. A. (1967). The Admiralty Chart: British Naval Hydrography in the Nineteenth Century.

…

She fired a gun and showed lights to warn the ships astern of her of the impending danger: [The land] being but two miles distant, we were all under the most dreadful apprehensions of running on shore; which, had either the wind blown from its usual quarter [south-west] with its wonted vigour, or had not the moon suddenly shone out, not a ship amongst us could possibly have avoided. . . .13 One officer recalled seeing the cliffs rearing up “like two black Towers of an extraordinary height,” but every ship managed to get clear.14 Anson’s own log gave the Centurion’s longitude on April 13 as 87°51' W, while another surviving log gives a longitude of 84°12' W just before land was sighted.15 The difference between these estimates is itself an indication of how difficult it was to determine longitude reliably by DR. In fact the longitude of Noir Island is about 73 degrees West, which means that Anson’s estimate was out by nearly 14 degrees—a distance of almost five hundred nautical miles in this latitude.

…

Under the terms of the British Longitude Act of 1714, a sum of up to £20,000 was offered as “a due and sufficient Encouragement to any such Person or Persons as shall discover a proper Method of Finding the said Longitude.” This would now be worth several million pounds. The Longitude Act, however, imposed high standards of accuracy: to win the maximum amount the successful method had to be capable of determining longitude within a margin of error not exceeding half a degree of a great circle (equivalent to thirty nautical miles). Half the maximum prize would be payable when the commissioners of the new Board of Longitude were satisfied that the proposed method extended to “the Security of Ships within Eighty Geographical Miles from the Shores, which are Places of the greatest Danger,” while the balance would be paid “when a ship . . . shall actually Sail over the Ocean, from Great Britain to any such Port in the West-Indies, as those Commissioners . . . shall Choose or Nominate for the Experiment, without Losing their Longitude beyond the Limits before mentioned.”

Adapt: Why Success Always Starts With Failure

by

Tim Harford

Published 1 Jun 2011

The British parliament turned to Sir Isaac Newton and the comet expert Edmond Halley for advice, and in 1714 passed the Act of Longitude, promising a prize of £20,000 for a solution to the problem. Compared with the typical wage of the day, this was over £30 million pounds in today’s terms. The prize transformed the way that the problem of longitude was attacked. No longer were the astronomers of the Royal Observatory the sole official searchers – the answer could come from anyone. And it did. In 1737, a village carpenter named John Harrison stunned the scientific establishment when he presented his solution to the Board of Longitude: a clock capable of keeping superb time at sea despite the rolling and pitching of the ship and extreme changes in temperature and humidity.

…

Pneumococcal infections kill nearly a million young children a year, almost all of them in poor countries. As John Harrison could have attested, the problem with an innovation prize is determining when the innovator has done enough to claim his reward. This is especially the case when the prize is not for some arbitrary achievement, such as being the fastest plane on a given day – remember the Schneider Trophy, which inspired the development of the Spitfire – but for a practical accomplishment such as finding longitude or creating immunity to pneumococcal meningitis. Harrison was caught up in an argument between proponents of the clock method and the astronomical method.

…

The cheap, easy-to-build and effective Hurricanes did indeed outnumber Spitfires in the early months of the war, but it was the Spitfire’s design that won the plaudits. * The Board of Longitude never gave Harrison his prize, but it did give him some development money. The British parliament, after Harrison petitioned the King himself, also awarded the inventor a substantial purse in lieu of the prize that never came. The sad story is superbly told by Dava Sobel in her book Longitude, although Sobel perhaps gives Harrison too much credit in one respect: it is arguable that by producing a seaworthy clock, albeit a masterpiece, he did not solve the longitude problem for the Royal Navy or society as a whole. To do that, he needed to produce a blueprint that a skilled craftsman could use to produce copies of the clock

You Are Here: From the Compass to GPS, the History and Future of How We Find Ourselves

by

Hiawatha Bray

Published 31 Mar 2014

The lunar tables prepared by Maskelyne and his colleagues formed the core of a new nautical almanac. Published every year, it became an indispensable guide to the world’s navigators. Eventually Greenwich would become the baseline used by sailors worldwide to calculate longitude. However, the lunar method wasn’t nearly accurate enough for the remarkable man who finally solved the problem for good. British carpenter and self-taught clockmaker John Harrison spent about forty of his eighty-three years of life designing timepieces that could withstand the stresses of a sea voyage while still keeping accurate time. His H4 marine chronometer of 1755 was a near miracle of engineering, losing just a few seconds of accuracy even after months at sea.

…

It depends how far north or south you were. At the equator, 15 degrees of longitude works out to about 1,035 miles of distance, or 69 miles for each degree. But the lines of longitude converge at the North and South Poles, so the distance covered by 15 degrees of longitude gets smaller as you move north or south of the equator. Luckily, a simple formula can be used to calculate the distance, as long as you already know your latitude. And, of course, navigators had already mastered latitude. Thus, if a sailor could nail down the calculation of longitude, he could quickly and accurately figure out his position on any ocean.

…

Yet they suspected that there was a rhyme and reason to such compass errors—and that decoding it would eventually lead to a solution to the previously intractable problem of east-west location: longitude. Some thought that the key had been discovered in 1544. That year, Venetian explorer Sebastian Cabot, who sailed under the flag of Spain, issued a map that showed a spot in the ocean, near the Azores, where magnetic compasses showed no declination at all. Here, the compass needle agreed with the polestar and pointed toward true North. Many a sailor rejoiced at the news, believing that magnetic declination would provide an easy way to measure longitude.14 They assumed that as a ship sailed east or west, magnetic declination would change in a smooth, regular manner.

The Dawn of Innovation: The First American Industrial Revolution

by

Charles R. Morris

Published 1 Jan 2012

It was then roasted and thoroughly dried (steam could explode a blast furnace) and pulverized in a stamping mill to reduce the impurities before smelting. Most ancient iron was from bog iron, but it is no longer used for industrial purposes. New Jersey’s iron bogs now produce cranberries. t John Harrison used wooden gears in the first longitude chronometers because the oils in the wood made them self-lubricating. Brass was harder and more durable but needed external lubrication, which trapped dust and other contaminants. Harrison feared that their accuracy would degrade on an extended voyage. As he shrank his chronometers, small-dimension machining mandated the switch to brass components.

…

A century later, that bias, perhaps interacting with a certain upper-class intellectual style, may have disadvantaged Great Britain in its inevitable industrial confrontation with the United States. The Longitude Problem Eighteenth-century British admirals grumbled about keeping their ships out past August. The navigational apparatus for taking latitude readings—the north/south position—was quite accurate. The noon sighting—to fix the latitude, recalibrate the ship’s clock, and turn the calendar—was inviolable ritual on British warships. A captain could readily find a line on the same latitude as the mouth of the English Channel and ride it home. Without obvious landmarks, however, it was much harder to divine how far east or west you were. That was the longitude problem, and to a seafaring nation it was of first importance.

…

More tragically, in 1707, a returning war fleet, under the impression they were well into the channel mouth, made the turn north and ran directly on the rocks of the Scillies, losing four warships, a popular admiral, and 2,000 crewmen. The shock led to the passage of the Longitude Act, which offered a series of prizes for full or partial solutions to the challenge of accurately positioning a ship at sea on the east-west axis.12 There were two potential solutions. One involved time. If you set a clock at Greenwich time before leaving England, you could accurately calculate longitude simply by taking the difference between Greenwich time and sun time at your location. But the clock had to be extremely accurate, off by less than three seconds a day.

Bold: How to Go Big, Create Wealth and Impact the World

by

Peter H. Diamandis

and

Steven Kotler

Published 3 Feb 2015

My first step, after realizing that an incentive prize might help me fulfill my personal moonshot, was to learn everything I could about prizes, their history, and how and why they worked. The Power of Incentive Competitions Orteig didn’t invent incentive prizes. Three centuries before Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic by plane, the British Parliament wanted some help crossing the Atlantic by ship. In 1714, the £20,000 Longitude Prize was offered to the first person to accurately measure longitude at sea. It worked. In 1765, horologist John Harrison pulled it off, but beyond opening the oceans to navigation, this competition brought incentive prizes—as a method for driving innovation—into the public eye. The idea spread quickly. In 1795, for example, Napoléon I offered a 12,000-franc prize for a method of food preservation to help feed his army on its long march into Russia.

…

In seeking the broadest range of qualified teams—independent of age, education, and experience—you maximize the opportunity for breakthrough results. In other words, don’t try to anticipate where solutions will come from. In the case of the Longitude Prize, the British Admiralty was so certain that determining longitude would come from looking at the stars, they filled the committee charged with picking the winner with astronomers. As a result, John Harrison, a watchmaker, was denied the purse for nearly a decade. 12. Prize timelines and deadlines. The prize timeline is a function of the competition’s degree of difficulty. Smaller HeroX challenges might be awarded in six months to a year, while larger-end $10 million XPRIZEs are designed to be won in a three- to eight-year time frame.

…

Louis (New York: Scribner, 1953). 2 Stephen Schaber, “Why Napoleon Offered a Prize for Inventing Canned Food,” NPR, March 5, 2012, http://www.npr.org/blogs/money/2012/03/01/147751097/why-napoleon-offered-a-prize-for-inventing-canned-food. 3 Knowledge Ecology International, “Selected Innovation Prizes and Reward Programs,” KEI Research Note 2008:1, http://keionline.org/misc-docs/research_notes/kei_rn_2008_1.pdf. 4 All Marcus Shingles quotes come from an AI conducted 2014. 5 Burt Rutan, “The real future of space exploration,” TED, February 2006, https://www.ted.com/talks/burt_rutan_sees_the_future_of_space. 6 Statista, “Statistics and facts on Sports Sponsorship,” Sports sponsorship Statista Dossier 2013, March 2013. 7 Alice Roberts, “A true sea shanty: the story behind the Longitude prize,” The Observer, May 17, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/science/2014/may/18/true-sea-shanty-story-behind-longitude-prize-john-harrison. 8 See http://www.interculturalstudies.org/faq.html#quote. 9 Dan Heath and Chip Heath, “Get Back in the Box: How Constraints Can Free Your Team’s Thinking,” Fast Company, December 1, 2007, http://www.fastcompany.com/61175/get-back-box. 10 For all things LunarX, see http://www.googlelunarxprize.org. 11 Campbell Robertson and Clifford Krauss, “Gulf Spill Is the Largest of Its Kind, Scientists Say,” New York Times, August 2, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/03/us/03spill.html?

Nuts and Bolts: Seven Small Inventions That Changed the World (In a Big Way)

by

Roma Agrawal

Published 2 Mar 2023

https://ramboll.com/projects/rdk/musikkens hus. Roberts, Alice. ‘A True Sea Shanty: The Story behind the Longitude Prize’. Observer, 17 May 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2014/may/18/true-sea-shanty-story-behind-longitude-prize-john-harrison. Royal Museums Greenwich. ‘Time to Solve Longitude: The Timekeeper Method’. 29 September 2014. https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/blog/time-solve-longitude-timekeeper-method. Royal Museums Greenwich. ‘Longitude Found – the Story of Harrison’s Clocks’. https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/harrisons-clocks-longitude-problem. Ruderman, James. ‘High-Rise Steel Office Buildings in the United States’ The Structural Engineer vol. 43, no. 1, 1965.

…

After the Scilly naval disaster in 1707, in which around 1,400 people lost their lives, in large part due to the inability of the navigators to accurately calculate their position, the British Parliament offered a significant award to anyone who could improve the safety of long-distance sea travel. The problem lay in plotting the Earth’s longitudes, a vital means of orientation when approaching land. (Polynesian navigators had been calculating longitude for years through natural observation and knew their patch of ocean well, but these techniques weren’t used in the West.) The solution, at least in theory, was simple. If a clock was synchronised with the exact time at the zero-degree longitude at Greenwich, and then taken on a long-haul voyage, navigators could then calculate the time of their local position using the Sun and stars, and compare this to Greenwich Mean Time.

…

‘Friction and Dynamics of Verge and Foliot: How the Invention of the Pendulum Made Clocks Much More Accurate’. Applied Mechanics, vol. 1, no. 2, 29 April 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/applmech1020008. Britannica. ‘Bow and Arrow’. https://www.britannica.com/technology/bow-and-arrow. Brown, Emily Lindsay. ‘The Longitude Problem: How We Figured out Where We Are’. The Conversation, 18 July 2013. http://theconversation.com/the-longitude-problem-how-we-figured-out-where-we-are-16151. Brown, Erik. ‘How The Ancients Improved Their Lives With Archery’. Medium, 15 October 2020. https://medium.com/mind-cafe/how-the-ancients-improved-their-lives-with-archery-1704318a1e60. Brownstein, Eric X.

Accessory to War: The Unspoken Alliance Between Astrophysics and the Military

by

Neil Degrasse Tyson

and

Avis Lang

Published 10 Sep 2018

But that didn’t faze Regnier Gemma Frisius, a Dutch mathematician who proposed that a good clock, set to the exact moment a ship left the dock, could serve as a stable point of comparison for the local time as ascertained at sea by Sun, star, or other means—assuming that the clock’s exactness could be preserved despite the moisture, cold, heat, salt, gravity, and tumult.68 Quite a task. Not until 1759, after thirty years of effort, did a provincial English craftsman named John Harrison manage to implement Gemma’s proposal. Harrison undertook the project not out of enthusiasm for a challenge or concern for his shipwrecked countrymen but because in the summer of 1714 the British parliament had, in desperation, put up a series of substantial cash prizes for a solution to the longitude problem. Spain had been the first to offer a prize, in 1598; Portugal, Venice, and Holland had followed suit—but to no avail, which is why France and Britain soon turned to the founding of scientific academies, the building of observatories, and the luring of Europe’s name-brand astronomers, still to no avail.

…

Since such a voyage would take six weeks, any mechanism that lost or gained more than two minutes—the time equivalent of half a degree—over the course of the journey could not fetch the top prize.69 Sounds strict, until you consider that being off by half a degree is like heading for Times Square in the heart of Manhattan but ending up across the Hudson River in Plainfield, New Jersey, or telling your navigator you want to go to Fort Worth, Texas, but getting dropped in Dallas. John Harrison fashioned not just one but several chronometers, whose accuracy exceeded the most stringent demand of the Longitude Act. The first, completed in 1735 and known as H-1, was an intricate brass tabletop contrivance that ran on springs, wheels, rods, and balances; the fourth, H-4, completed in 1759, was an exquisite outsize watch that lay supine in a cushioned box and ran on diamonds and rubies.

…

He referred to it as “our trusty friend the Watch,” “our never failing guide, the Watch,” and asserted that “indeed our error (in Longitude) can never be great, so long as we have so good a guide as [the] Watch.”72 With its help, he crossed the Antarctic Circle, conclusively disproved the existence of a massive southern continent extending well north of Antarctica, claimed some chilly islands for Britain, and charted regions of the South Pacific so accurately that twentieth-century mariners continued to depend on his findings. John Harrison died in 1776, but even before he was laid to rest, a skilled assistant had begun to make knock-offs of H-4: the cheaper and less functional K-2 and K-3.

The Slow Fix: Solve Problems, Work Smarter, and Live Better in a World Addicted to Speed

by

Carl Honore

Published 29 Jan 2013

Five decades later someone finally won the competition by inventing a highly accurate clock that could take precise readings even in the choppiest waters. The most striking thing about the winner was his biography. John Harrison was not a sailor or a shipbuilder. Nor was he a professor at Oxford or Cambridge or a member of the Royal Society. Indeed, he had very little formal education. The son of a carpenter from Yorkshire, he had taught himself how to make clocks. In other words, he was the ultimate diamond in the rough. As the discovery of longitude shows, tapping the crowd is not new. What has changed in recent years is that technology makes it possible to marshal and manage larger groups than ever before and unearth ideas in the most obscure corners of the globe.

…

Chapter 9 – Crowdsource: The Wisdom of the Masses Wutbürger as German word of the year: Full list available from German Language Society at http://www.gfds.de/aktionen/wort-des-jahres/ Guessing the weight of an ox: James Surowiecki, The Wisdom of Crowds (New York: Random, 2005), pp. xii-xiii. Pinpointing vessel lost at sea: Surowiecki, The Wisdom of Crowds, pp. xx-xxi. Public identifies Mars craters: Surowiecki, The Wisdom of Crowds, p. 276. Diversity Trumps Ability Theorem: Based on my interview with Scott Page. John Harrison: For the whole story check out Dava Sobel, Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time (London: Fourth Estate, 1998). Teenager invents method for detecting pancreatic cancer: Jake Andraka won first place at the 2012 Intel International Science and Engineering Fair (Intel ISEF), a program of the Society for Science and the Public.

…

In the early 18th century Britain’s Royal Navy lost many ships at sea because crews had no way to measure longitude while sailing. Some of the finest scientific minds of the day, including Sir Isaac Newton, had tried in vain to solve this problem. Desperate for a solution, Britain set aside its cosy assumptions about social class and turned to the crowd. In 1714 an Act of Parliament offered £20,000, a vast sum at the time, to anyone who invented a “Practicable and Useful” way of calculating longitude at sea. Five decades later someone finally won the competition by inventing a highly accurate clock that could take precise readings even in the choppiest waters.

Coming of Age in the Milky Way

by

Timothy Ferris

Published 30 Jun 1988

The same thing happens with squaring the circle.”3 Sebastian Cabot on his deathbed claimed that God had revealed the answer to him, but added, alas, that He had also sworn him to secrecy. Still, the longitude problem was obviously imperative, and more than a few inventors took it on, encouraged by the large cash prizes proffered by the governments of seafaring states like Spain, Portugal, Venice, Holland, and England. The richest of these was a prize of twenty thousand pounds, offered by the British Board of Longitude to anyone who could devise a practicable method of determining longitude on a transatlantic crossing to within one-half a degree, which equals sixty-three nautical miles at the latitude of London. John Harrison, an uneducated carpenter turned clock-maker, pursued the prize for much of his working life.

…

Time: 1761, 1769 Noteworthy Events: Transits of Venus observed by widely scattered scientific expeditions, permitting new determinations of the distance from the earth to the sun—the “astronomical unit.” Time: 1765 Noteworthy Events: John Harrison is acknowledged by the English Board of Longitude to have developed the marine chronometer, making possible accurate timekeeping and the determination of longitude at sea. Time: 1766 Noteworthy Events: Henry Cavendish identifies hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe. Time: 1781 Noteworthy Events: William Herschel discovers the planet Uranus. Time: 1783 Noteworthy Events: Herschel derives the general direction of the solar system’s motion through space, by studying the proper motion of thirteen bright stars.

…

A typical ship’s clock in the early eighteenth century was accurate to no better than five or ten minutes per day, which translated into a miscalculation of fully five hundred miles in longitude after only ten days at sea. It was just such an error that had dashed Cloudesley Shovell’s fleet on the rocks of the Scilly Islands. The problem of determining longitude at sea had defied resolution for so long that many regarded it as unsolvable. The mathematician in Cervantes’s The Dog’s Dialog muses crazily that he has “spent twenty-two years searching for the fixed point”— el punto fijo, the correct longitude—“and here it leaves me, and there I have it, and when it seems I really have it and it cannot possibly escape me, then, when I am not looking, I find myself so far away again that I am astonished.

The Human Cosmos: A Secret History of the Stars

by

Jo Marchant

Published 15 Jan 2020

As the start of Cook’s first Pacific voyage neared, however, both approaches—clocks and astronomy—were finally on the verge of becoming practical. In 1759, after more than thirty years’ experimentation, the Yorkshire carpenter John Harrison came up with a device he called H4: a small clock, or chronometer, that could keep time on a ship (a story popularized in Dava Sobel’s 1995 best-seller Longitude). With the newly invented sextant, which allowed more accurate measurements of altitude at sea than ever before, navigators could compare local time at noon with the time back home. But the H4 was still being tested and argued over when Cook set sail in 1768.

…

Despite being in a sealed darkroom, they had adjusted their activity according to the local movements of the Moon. Instead of relying on inner timers, he was convinced they were sensing signals from the sky. These two approaches essentially paralleled the rival timekeeping methods used by navigators in the eighteenth century to calculate longitude. You can build a machine that keeps its own time, as clockmaker John Harrison did with his chronometer. Or you can take time references directly from the sky, as with the astronomer Nevil Maskelyne’s method of lunar distances. Which solution did life choose? Brown decided to investigate the most fundamental biological process he could think of: metabolism.

…

The sixteenth-century Dutch astronomer Gemma Frisius was first to realize that although we think of longitude in geographical terms, as a position in space, with respect to the sky it’s actually a function of time. Observers at differing longitudes are at different points in the Earth’s daily rotation, so at any set moment, they will each see the Sun or stars at a different point in the sky; the greater the difference in longitude, the greater the difference in the time of day. Frisius suggested that as long as a traveler knows the time at his starting point and at his current location, he can find his change in longitude by calculating the difference between the two.* This was easier said than done, however.

Time Lord: Sir Sandford Fleming and the Creation of Standard Time

by

Clark Blaise

Published 27 Oct 2000

Let Greenwich do her best to maintain her high position in administering to the longitude of the world, and Nautical Almanacs do their best, and we will unite our effort without special acclaim to the fictitious honour of a Prime Meridian. Airy’s conclusion strikes the scornful, above-the-battle stance to which astronomy often aspires. (One need only recall the arguments recorded in Dava Sobel’s Longitude, the contempt of an earlier astronomer-royal, Sir Nevil Meskalyne, for the provincial clock-maker John Harrison.) Airy’s recommendation to the Privy Council was to abstain from any “novelty” or “social usage,” on the principle that government intervention might prove more harmful than the recognized inconveniences enumerated in Fleming’s paper.

…

It will be seen that we are about 40 degrees nearer Greenwich and therefore 40/360th or about 1/9th the circumference of the Globe (in this latitude) away from Toronto and therefore our time on board should be 1/9th of 24 hours faster than Toronto time, hence where it is noon by my watch it is 2:40 o’clock by ship’s time. Between noon yesterday and noon today we ran easterly about five and a half degrees longitude and as each degree of longitude is equal to 24 hours divided by 360, or four minutes of time, the ship clock has to be moved forward four minutes for each degree of longitude passed over and thus today five and a half times 4 equals 22 minutes. At this rate our lunch which is at noon will come about twenty minutes sooner every day. The distance between Quebec and Glasgow by the course of the ship is about 2900 miles and this afternoon we have passed over about half that distance.

…

The universal day should begin at the Greenwich midnight, not noon, for the avoidance of double-counting the dates in Europe and North America. The Russian deserves credit for the east-west division of longitudes, 180 degrees east and west from the zero meridian, also an overturning of a Fleming-supported Rome agreement. Otherwise, Greenwich would have been in the anomalous position of lying, simultaneously, on the zero and the 360th degree of longitude. Villages a few miles west of Greenwich would carry unwieldy coordinates like 359 degrees west longitude, while neighboring towns a few miles east might lie at two degrees. To de Struve also goes the credit for unifying the astronomer’s day with the civil day (“We think it easier for the astronomers to change the starting point, and to make allowance for the twelve hours of difference in their calculations, than it would be for the public and for the business men, if the date for the universal time began at noon, and not at midnight”) and, perhaps most significantly, for the creation of the all-important international date line (“the change of the day of the week, historically established on or about the anti-meridian of Greenwich, should henceforth take place exactly on that meridian”).

Whiplash: How to Survive Our Faster Future

by

Joi Ito

and

Jeff Howe

Published 6 Dec 2016

Jeff Howe, “The Crowdsourcing of Talent,” Slate, February 27, 2012, http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2012/02/foldit_crowdsourcing_and_labor_.html. 6 Jeff Howe, “The Rise of Crowdsourcing,” WIRED, June 1, 2006, http://www.wired.com/2006/06/crowds/. 7 Todd Wasserman, “Oxford English Dictionary Adds ‘Crowdsourcing,’ ‘Big Data,’” Mashable, June 13, 2013, http://mashable.com/2013/06/13/dictionary-new-words-2013/. 8 “Longitude Found: John Harrison,” Royal Museums Greenwich, October 7, 2015, http://www.rmg.co.uk/discover/explore/longitude-found-john-harrison. 9 Michael Franklin, “A Globalised Solver Network to Meet the Challenges of the 21st Century,” InnoCentive Blog, April 15, 2016, http://blog.innocentive.com/2016/04/15/globalised-solver-network-meet-challenges-21st-century/. 10 Karim R.

…

The sciences have long utilized various distributed knowledge networks that were able to effectively marshal the diversity that exists across a wide range of disciplines. One of the best-known examples is the Longitude Prize. In 1714 the English Parliament offered a £10,000 prize to anyone who could figure out a method to determine longitude. Some of the leading scientific minds focused their considerable talents on this problem, but the purse was eventually claimed by the self-taught clockmaker John Harrison. 8 Of course, amateurs have always made contributions to disciplines like astronomy and meteorology that thrive on large numbers of observations. But before the Internet, the public had little opportunity to contribute to the creation of other types of scientific knowledge.

The Runaway Species: How Human Creativity Remakes the World

by

David Eagleman

and

Anthony Brandt

Published 30 Sep 2017

Edison, “The Phonograph and Its Future,” Scientific American 5, no. 124 (1878): 1973-4, <http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican05181878-1973supp> 7 Dava Sobel, Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time (New York: Walker, 1995). 8 Dava Sobel, Longitude. 9 Unfortunately, Harrison never received his due. To test whether Harrison’s elaborate design could be manufactured by others, the Board of Longitude commissioned another watchmaker named Larcum Kendall to make a copy. It took Kendall two and half years to complete it. Kendall’s knock-off, called the K-1, was indistinguishable from Harrison’s except for a more ornate backplate. The Board of Longitude chose the K-1 over the H-4 to accompany Captain Cook on his voyage to the Pacific; in their minds, that disqualified Harrison for the Longitude Prize.

…

Edison, “The Phonograph and Its Future,” Scientific American 5, no. 124 (1878): 1973-4, <http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican05181878-1973supp> 7 Dava Sobel, Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time (New York: Walker, 1995). 8 Dava Sobel, Longitude. 9 Unfortunately, Harrison never received his due. To test whether Harrison’s elaborate design could be manufactured by others, the Board of Longitude commissioned another watchmaker named Larcum Kendall to make a copy. It took Kendall two and half years to complete it. Kendall’s knock-off, called the K-1, was indistinguishable from Harrison’s except for a more ornate backplate. The Board of Longitude chose the K-1 over the H-4 to accompany Captain Cook on his voyage to the Pacific; in their minds, that disqualified Harrison for the Longitude Prize.

…

Faced with continued losses in their fleet, Parliament made a bold decision to inspire people to look beyond the usual solutions: it announced a prize of £20,000 (the equivalent of $1 million in today’s money) for anyone who devised a way to accurately measure longitude. As science historian Dava Sobel writes, “This power over purse strings made the Board of Longitude perhaps the world’s first official research-and-development agency.”8 The early results were not promising. The Board of Longitude evaluated proposals for a diverse array of devices with fanciful names like phonometers, pyrometers, selenometers and heliometers. None worked. Fifteen years after the prize was announced, the Board had still not found a single effort worthy of support.

Pinpoint: How GPS Is Changing Our World

by

Greg Milner

Published 4 May 2016

But it was ultimately the horological solution that prevailed. John Harrison, a self-taught clockmaker, developed an ocean-hardened chronometer he called H4. The first reproduction of H4 was carried on Cook’s second Pacific voyage, when his encounter with Tupaia was a distant memory. Having tested it against the lunar distance method for calculating longitude, Cook offered rave reviews of the chronometer when he returned to England in July 1775, calling it “our trusty friend” and “our never failing guide.” The chronometer soon became standard. The longitude problem was solved. The significance of the chronometer cannot be overstated.

…

Captains might increase the certainty of their bearings by hewing close to latitudinal parallels, the method Columbus used during his voyage to North America. By the early eighteenth century, longitude miscalculations were responsible for several deadly shipwrecks. The problem was not merely safety, but also the perceived economic losses caused by the inability of ships to go anywhere and everywhere with confidence. The widespread skepticism that longitude was conquerable was reflected in the common colloquialism “discovering the longitude,” which meant attempting the impossible. The longitude problem presented itself as a classic Enlightenment conundrum. To search for “the longitude”—and discover it—was to pursue a kind of perfect knowledge.

…

David Lewis: “[N]o one seems to have asked [Tupaia] how he oriented himself, or what his actual concepts and methods were” (We, the Navigators, 9). Chapter 2: The When and the Where 24 the transit of Venus: Steven Cherry, Transit of Venus: The Other Half of the Longitude Story, Techwise Conversations, n.d., http://spectrum.ieee.org/podcast/geek-life/profiles/transit-of-venus-the-other-half-of-the-longitude-story. 26 “discovering the longitude”: Dava Sobel, Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time (New York: Walker and Co., 1995), 56. 27 In 1800, Chevalier de Lamarck: Walter Sullivan, “The IGY—Scientific Alliance In a Divided World,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 14, no. 2 (February 1958): 68–72. 28 first international organization: Ibid., 68. 28 “the largest organized intellectual enterprise”: John A.

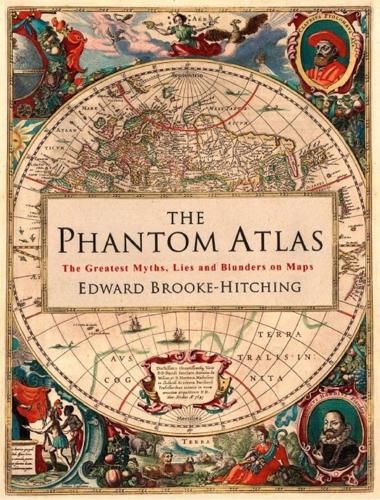

The Phantom Atlas: The Greatest Myths, Lies and Blunders on Maps

by

Edward Brooke-Hitching

Published 3 Nov 2016

Most often seen in polar regions, the optical illusion is a prolific culprit in the perpetration of false land sightings – it is accused, for example, of being the implement of disaster in Baron von Toll’s 1902 expedition to find Sannikov Land in the Arctic Ocean. And then, of course, there is the honest error, which is usually rooted in educated guesses of ‘wishful mapping’ or the limited ability of contemporary measurement systems. Coordinates were rough and imprecise, until John Harrison’s invention of an accurate marine chronometer in the eighteenth century provided a long-sought solution to the problem of measuring longitude. Errors were copied, and discoveries even frequently ‘remade’. Lieutenant Charles Wilkes, for example, during an 1838 survey of the Tuamotos, discovered an island at 15°44'S, 144°36'W. He named it King Island, in honour of the lookout who had spotted it.

…

.* Describing the Crocker Land question as ‘the world’s last geographical problem’, MacMillan announced the mission to the world at a press conference in 1913: Donald MacMillan, c.1910. In June 1906, Commander Peary, from the summit of Cape Thomas Hubbard, at about latitude 83 degrees N, longitude 100 degrees W, reported seeing land glimmering in the northwest, approximately 130 miles [210km] away across the Polar Sea. He did not go there, but he gave it a name in honor of the late George Crocker of the Peary Arctic Club. That is Crocker Land. Its boundaries and extent can only be guessed at, but I am certain that strange animals will be found there, and I hope to discover a new race of men.

…

In the eighteenth century, a sceptical Vitus Bering, a Danish explorer in Russian service, spent three days hunting for the islands, only to have his doubts confirmed. On 16 April 1779, Captain James Cook made a critical note of Gamaland in the third volume of his Voyage to the Pacific Ocean: At noon, on the 16th, our latitude was °42 12' [sic] and our longitude 160°5’; and, being near the situation where De Gama is said to have seen a great extent of land, we were glad of an opportunity of contributing to remove the doubts, if any yet remained, respecting this pretended discovery . . . Mr. Muller relates, that the first account of it was in a chart published by [Portuguese cartographer] Texeira, in 1649; who places it between the latitude of 44° and 45°, and calls it ‘land seen by John De Gama, in a voyage from China to New Spain.’

The Knowledge: How to Rebuild Our World From Scratch

by

Lewis Dartnell

Published 15 Apr 2014

The Sun’s position is how we define the time of day (right back to the fundamentals of sundials we saw earlier), and so the problem of finding your longitude—how far around the world you are from some chosen baseline—boils down to finding the difference in time of day at the same instant between the baseline and your current position. The Earth spins 360 degrees in 24 hours, so a difference in the timing of noon of one hour equates to 15 degrees of longitude. Determining your longitude is therefore a measure of time transposed back into space. In fact, you’ve almost certainly felt the solution to longitude acutely yourself: modern high-speed air transport teleports us between remote locations with very different local times before our bodies can adapt.

…

Similarly, you can start at the equator, already defined as the circle around the planet halfway between both poles, and imagine dropping shrinking rings every 10 degrees toward the north and south, with the poles therefore at 90 degrees. These traces running north-south between the poles are called lines of longitude, and the east-west rings encircling the planet on either side of the equator are lines of latitude. All the lines of latitude are parallel to one another, and the lines of longitude cut across them always at right angles. So, near the waistband of the world the latitude-longitude coordinates approximate the street-avenue system on the flat plane of Manhattan, with the square grid increasingly distorted toward the poles by the spherical geometry of the Earth.

…

As with the Manhattan streets, you need to set starting points so you can specify your numbered coordinates relative to them. The equator is the obvious 0° latitude line, but there is no corresponding natural zero mark for the longitude numbering: we happen to use Greenwich, London, as the “prime meridian” purely out of historical convention. To specify your location anywhere on the planet using this universal address system, all you need to do is state how many degrees north or south of the equator you are—your latitude—and how many degrees east or west of the prime meridian—your longitude. Right now, my smartphone says that I am at 51.56° N, 0.09° W (I’m in north London, not far from Greenwich). So, the original problem we set ourselves—how to navigate the world between known locations—splits neatly into two separate questions: How do I find my latitude, and how do I find my longitude?

Maphead: Charting the Wide, Weird World of Geography Wonks

by

Ken Jennings

Published 19 Sep 2011

Today we’re so surrounded by high-quality maps that we have the tendency to take them for granted. Well, of course this is what my hometown looks like! See, here it is on Google Earth. Maybe we can remember or imagine a time when there was no aerial imagery or airborne radar or GPS, but 250 years ago, before John Harrison invented the marine chronometer, there wasn’t even a reliable way for sailors to measure their own longitude. Think about that for a moment: the best technology on Earth couldn’t tell you how far east or west you were at any given moment. That’s a wee bit of an obstacle when it comes to drawing reliable maps. When Ptolemy mapped the known world in the second century, he had to rely on oral histories and a series of rough mathematical guesses to gauge east-west distances.

…

At least members of the Highpointers Club are climbing to real geographical peaks, albeit minor ones in many cases. The earth’s grid of latitude and longitude, on the other hand, is entirely arbitrary. The fact that we divide the circle into 360 degrees is an ancient artifact based on the Babylonians’ (incorrect) estimate of the number of days in a year. Lines of longitude are even more arbitrary, since the Earth doesn’t have any West Pole or East Pole. Our current zero-degree line of longitude, the Prime Meridian through Greenwich, was a convention chosen only after much political wrangling at the 1884 International Meridian Conference, called by mutton-chopped U.S. president Chester A.

…

“So if I draw imaginary highways to spell dirty words in the middle of Siberia, you’ll catch me?” I asked Google’s Jessica Pfund. “Oh, we’ve seen that,” she said wearily. * If you do the math, there are actually 64,422 latitude and longitude confluences, but most of them are located on water or on the polar icecaps. Jarrett and company have also disallowed many of the higher-latitude confluences because lines of longitude converge there. As you get further from the Equator, confluences crowd together until they’re less than two miles apart at the poles. * The singular form of “antipode” has three syllables, like “antipope,” but the plural has four: “an-tip-uh-deez.”

Alchemy: The Dark Art and Curious Science of Creating Magic in Brands, Business, and Life

by

Rory Sutherland

Published 6 May 2019

In the mid-eighteenth century, a largely self-taught clockmaker called John Harrison heard that the UK Government had pledged £20,000 – several million pounds in today’s currency – as a prize for anyone who could establish longitude to within half a degree* after a journey from England to the West Indies, and was determined to find a solution. This was a life and death matter – a navigational disaster by British naval ships off the Isles of Scilly in 1707 had left several thousand sailors dead. To judge proposed solutions, the crown established a Board of Longitude, consisting of the Astronomer Royal, admirals and mathematics professors, the Speaker of the House of Commons and ten Members of Parliament.

…

A 30-minute delay on a one-hour flight is a far greater annoyance than a one-hour delay on a nine-hour flight. *Or the ones who want an excuse to cancel their bloody meeting in Frankfurt. *I will explain how later in this book. *Thirty nautical miles at the equator. *We owe it to Dava Sobel and her bestselling book Longitude (1995) that the name of John Harrison is now widely known. *They had hence proved not only that a heavier-than-air machine could fly, but also that snobbery is not an exclusively British vice. *Semmelweis was even more cruelly treated than Harrison: he died in a lunatic asylum, perhaps having been beaten by the guards, insisting to his last breath that his theory was right.

…

Contents Cover Title Page Rory’s Rules of Alchemy Prologue: Challenging Coca-Cola The Case for Magic Introduction: Cracking the (Human) Code Introducing Psycho-Logic Some Things Are Dishwasher-Proof, Others Are Reason-Proof Crime, Fiction and Post-Rationalism: Or Why Reality Isn’t Nearly as Logical as We Think The Danger of Technocratic Elites On Nonsense and Non-Sense The Opposite of a Good Idea Can Be a Good Idea Context Is Everything The Four S-es Why We Should Ignore Our GPS 1: On the Uses and Abuses of Reason 1.1: The Broken Binoculars 1.2: I Know It Works in Practice, but Does It Work in Theory? On John Harrison, Semmelweis and the Electronic Cigarette 1.3: Psychological Moonshots 1.4: In Search of the ‘Real Why?’ Uncovering Our Unconscious Motivations 1.5: The Real Reason We Clean Our Teeth 1.6: The Right Thing for the Wrong Reason 1.7: How You Ask the Question Affects the Answer 1.8: ‘A Change in Perspective Is Worth 80 IQ Points’ 1.9: Be Careful with Maths: Or Why the Need to Look Rational Can Make You Act Dumb 1.10: Recruitment and Bad Maths 1.11: Beware of Averages 1.12: What Gets Mismeasured Gets Mismanaged 1.13: Biased about Bias 1.14: We Don’t Make Choices as Rationally as We Think 1.15: Same Facts, Different Context 1.16: Success Is Rarely Scientific – Even in Science 1.17: The View Back Down the Mountain: The Reasons We Supply for Our Experimental Successes 1.18: The Overuse of Reason 1.19: An Automatic Door Does Not Replace a Doorman: Why Efficiency Doesn’t Always Pay 2: An Alchemist’s Tale (Or Why Magic Really Still Exists) 2.1: The Great Upside of Abandoning Logic – You Get Magic 2.2: Turning Lead into Gold: Value Is in the Mind and Heart of the Valuer 2.3: Turning Iron and Potatoes into Gold: Lessons from Prussia 2.4: The Modern-Day Alchemy of Semantics 2.5: Benign Bullshit – and Hacking the Unconscious 2.6: How Colombians Re-Imagined Lionfish (With a Little Help from Ogilvy and the Church) 2.7: The Alchemy of Design 2.8: Psycho-Logical Design: Why Less Is Sometimes More 3: Signalling 3.1: Prince Albert and Black Cabs 3.2: A Few Notes on Game Theory 3.3: Continuity Probability Signalling: Another Name for Trust 3.4: Why Signalling Has to Be Costly 3.5: Efficiency, Logic and Meaning: Pick Any Two 3.6: Creativity as Costly Signalling 3.7: Advertising Does Not Always Look Like Advertising: The Chairs on the Pavement 3.8: Bees Do It 3.9: Costly Signalling and Sexual Selection 3.10: Necessary Waste 3.11: On the Importance of Identity 3.12: Hoverboards and Chocolate: Why Distinctiveness Matters 4: Subconscious Hacking: Signalling to Ourselves 4.1: The Placebo Effect 4.2: Why Aspirin Should Be Reassuringly Expensive 4.3: How We Can ‘Hack’ What We Can’t Control 4.4: ‘The Conscious Mind Thinks It’s the Oval Office, When in Reality It’s the Press Office’ 4.5: How Placebos Help Us Recalibrate for More Benign Conditions 4.6: The Hidden Purposes Behind Our Behaviour: Why We Buy Clothes, Flowers or Yachts 4.7: On Self-Placebbing 4.8: What Makes an Effective Placebo?

Reinventing the Bazaar: A Natural History of Markets

by

John McMillan

Published 1 Jan 2002

An early precedent for a buyout is the prize the British Parliament offered in the eighteenth century for a method of determining longitude, as chronicled by Dava Sobel in her absorbing book Longitude. Untold lives had been lost in shipwrecks caused by navigation errors, so the prize offered was a rich £20,000. A host of inventors submitted ideas, most of them hare-brained. The problem of measuring longitude accurately was solved by a humble clockmaker, John Harrison, with his invention of the chronometer. Its design was made available “for the use of the public” and it came to be mass-produced and universally used aboard ships, making sea journeys far less hazardous.

…

Governments—and everyone else—lack the knowledge to set the buyout price optimally. If it is set too low, it will not succeed in generating any new drugs. If it is set too high, on the other hand, the taxpayers’ money will be misspent. In the case of the prize for the measurement of longitude, for instance, the flurry of activity set off by the announcement of the prize and John Harrison’s own actions suggest, with the benefit of hindsight, that a more modest prize might have worked as well.12 A research tournament is an alternative way of generating innovation. This offers a cash prize, as with the buyout mechanism, but is awarded differently.

…

An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Chicago, University of Chicago Press. First published in 1776. Smith, Eugene. 1975. Minamata, New York, Holt, Rinehart, Winston. Smith, Vernon L. 1982. “Microeconomic Systems as an Experimental Science.” American Economic Review 72, 923–955. Sobel, Dava. 1996. Longitude. New York, Penguin. Sobel, Joel, and Takahashi, Ichiro. 1983. “A Multistage Model of Bargaining.” Review of Economic Studies 50, 411–426. Sobel, Robert. 1970. The Curbstone Brokers: The Origins of the American Stock Exchange. New York, Macmillan. Spence, A Michael. 1973. “Job Market Signaling.”

Infinite Powers: How Calculus Reveals the Secrets of the Universe

by

Steven Strogatz

Published 31 Mar 2019

Galileo died before he could build his clock and use it to tackle the longitude problem. Christiaan Huygens presented his pendulum clocks to the Royal Society of London as a possible solution, but they were judged unsatisfactory because they were too sensitive to disturbances in their environment. Huygens later invented a marine chronometer whose ticktock oscillations were regulated by a balance wheel and a spiral spring instead of a pendulum, an innovative design that paved the way for pocket watches and modern wristwatches. In the end, however, the longitude problem was solved by a new kind of clock, developed in the mid-1700s by John Harrison, an Englishman with no formal education.

…

When Galileo was trying to devise a pendulum clock in his last year of life, he had the longitude problem firmly in mind. He knew, as scientists had known since the 1500s, that the longitude problem could be solved if one had a very accurate clock. A navigator could set the clock at his port of departure and carry his home time out to sea. To determine the ship’s longitude as it traveled east or west, the navigator could consult the clock at the exact moment of local noon, when the sun was highest in the sky. Since the Earth spins through 360 degrees of longitude in a twenty-four-hour day, each hour of discrepancy between local time and home time corresponds to 15 degrees of longitude.

…

They offered the first real hope of solving the greatest technological challenge of Galileo’s era: finding a way to determine longitude at sea. Unlike latitude, which can be ascertained by looking at the sun or the stars, longitude has no counterpart in the physical environment. It is an artificial, arbitrary construct. But the problem of measuring it was real. In the age of exploration, sailors took to the oceans to wage war or conduct trade, but they often lost their way or ran aground because of confusion about where they were. The governments of Portugal, Spain, England, and Holland offered vast rewards to anyone who could solve the longitude problem. It was a challenge of the gravest concern.

Map of a Nation: A Biography of the Ordnance Survey

by

Rachel Hewitt

Published 6 Jul 2011

There were neither lunar-distance tables nor chronometers accurate enough to cope with this task: the rolling of a ship, changes in temperature or variations in air pressure played havoc with the rate of timekeepers. So in 1714 the Board of Longitude set up a competition that offered a prize of £20,000 to anyone who could determine longitude on board ship to within thirty nautical miles of accuracy. Famously a man called John Harrison, who had built his first clock in 1713 at the age of twenty, dedicated himself to the chronometer method of overcoming the longitude problem for over forty years. Between 1730 and the 1770s, this talented craftsmen made five beautiful timekeepers for the competition, for which he eventually received a total of £23,065.

…

It was then that he approached the British with the idea of verifying the precise longitude and latitude of the two royal observatories at Paris and Greenwich. But whereas English astronomers typically preferred to discover these positions by treating the stars as celestial compasses, Cassini de Thury recommended eschewing such ‘positional astronomy’ in favour of using triangulation to discover longitude and latitude by ‘joining up’ the meridian arc that bisected Paris with the Greenwich Observatory. His motives for suggesting the project were manifold. The check on Paris’s longitude and latitude would confirm the accuracy of the Carte de Cassini.

…

In the last decades of the eighteenth century, Thomas threw himself into a dispute that split the scientific community in two. Back in 1714, a governmental body had been established ‘for the Discovery of Longitude at Sea’. Longitude and latitude, those conceptual lines that criss-cross the globe, were the primary means by which mariners oriented their vessels. Latitude was easy to discover according to the height of the sun or various stars above the horizon. But in the eighteenth century longitude was much trickier to establish on board ship. There were two principal ways: because the earth turns on its own axis every twenty-four hours, the sun’s light shifts longitudinally as time passes and therefore a calculation of the time difference between the boat and the home port allows the determination of the distance between them in longitude.

Rage Inside the Machine: The Prejudice of Algorithms, and How to Stop the Internet Making Bigots of Us All

by

Robert Elliott Smith

Published 26 Jun 2019

History Today, www.historytoday.com/duncan-bythell/cottage-industry-and-factory-system 4Maskelyne is most popularly remembered as the nemesis of John Harrison, inventor of the marine watch, who was denied a parliamentary award for this solution to ‘the longitude problem’ for many years, based on evaluations and decisions involving Maskelyne. While this was clearly unfair, as Harrison’s solution was ultimately more effective than the Nautical Almanac; the watches were the supercomputers of their day, and they remained too rare and expensive for use throughout maritime industry. The Nautical Almanac, including tables that implemented Maskelyne’s longitude technique, would continue to be widely used for navigation well into the nineteenth century. 5Mary Croarken, 2003, Mary Edwards: Computing for a Living in 18th-Century England.

…

So while we now view astronomy as a niche hobby, up until the nineteenth century it was one of the most important fields of human endeavour, business as serious as building B-52s during the Cold War, or big-data algorithms today. Finding a computational solution to the longitude problem was the most important challenge in that vital endeavour. English Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne was charged with this challenge, which made him the most important technologist of his time. Maskelyne developed a system for determining one’s longitude, but unfortunately it required the computation of massive tables.4 The secret to Maskelyne’s longitude system is that it is relatively easy to know what time it is in a particular location on the spinning surface of the Earth, because no matter where you are on Earth, as long as weather allows you to see the sun, you can determine the local time (particularly at midday, when the sun is at its maximum height).

…

Finding one’s position on the Earth is hard, because the Earth is spinning. The stars in the sky can help you tell where you are from North to South (latitude), but not from East to West (longitude), because the Earth spins East to West under the canopy of stars. For centuries, this fundamental fact of life meant a substantial risk that merchant ships laden with valuable cargo might go astray, or warships might not arrive at the scene of battle on time, because they couldn’t accurately tell where they were East to West. Modern GPS fixes this longitude problem by placing satellites above the Earth that spin in geostationary orbit so that we can measure against their fixed position (relative to Earth) to determine our location and plot our routes.

Asteroid Hunters (TED Books)

by

Carrie Nugent

Published 14 Mar 2017

But pressure from the other astronomers was mounting (Rule #2: “Share your observations”). Everyone was itching to see this new planet for themselves. Not everyone was being nice about it. Britain’s Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne, has been remembered by history as a bit of a jerk. (If you have read Dava Sobel’s Longitude, you may remember Maskelyne as John Harrison’s nemesis). At this time, he wrote a particularly nasty passage: “There is great astronomical news: Mr. Piazzi, Astronomer to the King of the two Sicilies, at Palermo, discovered a new planet the beginning of this year, and was so covetous as to keep this delicious morsel to himself for six weeks; when he was punished for his illiberality by a fit of sickness . . .”

…

To determine its orbit, astronomers would need as many observations of the asteroid’s position as possible. This would require international cooperation. Some asteroids are only visible from one hemisphere on Earth; it’s possible that tracking would need to be done by astronomers in countries below the equator. And since telescopes can’t look at the Sun, you’d want observatories at different longitudes, so the asteroid could be monitored constantly as night falls around the globe. But even after thousands of observations, there’s still going to be a small amount of uncertainty in where exactly the asteroid is going. Although the orbit might be predicted with extraordinary precision, the chance it has of hitting Earth is expressed as a probability.

Skyfaring: A Journey With a Pilot

by

Mark Vanhoenacker

Published 1 Jun 2015

Flying over north London I can see a churchyard in which I sometimes sit with a coffee, where the tomb of John Harrison, “late of Red-Lion Square,” stands. Encouraged by the astronomer Edmund Halley, Harrison developed the “sea clocks” that helped solve the longitude problem, the difficulty with determining one’s east–west position at sea, an achievement so important that the officials who recognized it were known as Commissioners of Longitude. At such moments over London, as we come to the end of the planetwide countdown that every flight to this city effects, our longitude is nearly zero; it may ticktock from west and east and back to west as we cross the Greenwich Meridian in the next minutes of our approach pattern to Heathrow.

…

Transfixed by the ocean, he wrote to his brother that if he had had such an experience of the sea when he was younger, he might have devoted himself to nautical adventures rather than the “pursuits on land” that would bring him his fame and fortune. The captain on Hopkins’s ship, after determining the latitude and longitude, posted this information “where all may see and enter in their journal.” In the cockpit green digits show our longitude and latitude, much as the captain’s notice showed Hopkins the last-known position that he then copied onto his letters, an itinerant and star-sighted address as important a detail to him as the date. Hopkins also wrote about the stars at sea, which have “a serenity and bewitching loveliness in these latitudes such as I have never seen on land.”

…

Before I became a pilot I had the naive sense—a feeling, as opposed to what I’d been taught to the contrary—that most people lived in a world that looked something like where I grew up: small towns, forests, fields, four seasons, hills in some recurring, familiar pattern, the reference of a coastline a few hours away, and the vague gravity of a major metropolis at some similar distance. Today I understand in a direct and visual sense what I learned in school, that humanity is concentrated in a dense set of the lower latitudes of the northern hemisphere, and further in a dense set of longitudes in the eastern hemisphere; and what I have read since school, that ours is an age of cities—small ones as well as the conurbations like Mumbai, Beijing, and São Paulo that dominate the urban earth—in which for the first time a majority of humanity lives. A plane’s center of gravity is a critical piece of information that pilots receive before takeoff; it depends on the weight and location on the aircraft of the passengers, cargo, and fuel.

The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty

by

Daron Acemoglu

and

James A. Robinson

Published 23 Sep 2019

Both the nature of experimentation, with plenty of false starts and a multitude of disparate approaches, and its critical role in innovative breakthroughs are perhaps best illustrated by the quest for a way for ships to tell their longitude at sea. Latitude could be calculated from the stars, but longitude was a bigger challenge. Ships frequently got lost at sea and the problems this caused became all too obvious in October 1707 when four out of a fleet of five British warships returning from Gibraltar miscalculated their longitude and sank on the rocks of the Isles of Scilly. Two thousand sailors drowned. The British government established the Board of Longitude and offered a series of prizes in 1714 to encourage a solution to this problem. It was known that one solution was to have two clocks on board a ship.

…

One set to, say, Greenwich mean time, and another that could be reset to noon each day by the sun at sea. Then one would know the time in Greenwich, and the time where you were. The difference between these times allowed you to calculate longitude. The trouble was that clocks were inaccurate, based on pendulums which got hopelessly out of whack at sea, or made of metals which expanded or contracted under different climatic conditions. The great physicist Isaac Newton, charged by the government to advise them on ways to calculate longitude, was deeply committed to the idea that this must come through astronomy and star positions. Though he agreed that in principle the clock solution worked, in practice it was dead in the water because by reason of the motion of the ship, the Variation of Heat and Cold, Wet and Dry, and the Difference of Gravity in different Latitudes, such a watch hath not yet been made.

…

Along the way he made many profound innovations, for example, using ball bearings for the first time, a technology still used for reducing rotational friction in most machines today. The obsessive search for a solution to longitude and all of the whacky ideas it engendered was was satirized by William Hogarth in a series of paintings called The Rake’s Progress. The last in the series depicts the infamous mental asylum in London, Bedlam, filled with those driven mad by the search for a way to calculate longitude. A consequence of all of this bustling experimentation was greater social mobility. As people from modest backgrounds succeeded in their efforts, they not only made money, but gained greater social recognition.

The Half-Life of Facts: Why Everything We Know Has an Expiration Date

by

Samuel Arbesman

Published 31 Aug 2012

Revealing hidden knowledge through the power of the crowd has been a great idea at almost any time in human history. This is behind the concept of the innovation prize. The British government once offered a prize for the first solution to accurately measure longitude at sea—created in 1714 and awarded to John Harrison in 1773—but this was by no means the first such prize. Other governments had previously offered other prizes for longitude: the Netherlands in 1627 and Spain as early as 1567. They hoped that by getting enough people to work on this problem, the solution—perhaps obtained by drawing on ideas from different fields—would emerge. In 1771, a French academy offered a prize for finding a vegetable that would provide adequate nutrition during a time of famine.

…

Robert Merton, a renowned sociologist of science, argued in “Science, Technology, and Society in Seventeenth-Century England” that the concerns of the English people during this time period affected where the scientists and engineers of that century focused their attentions. It is unsurprising that they were obsessed with the construction of precise timepieces—that is what was needed in order to carefully measure longitude on the high seas, something of an English preoccupation during this time. In addition, Merton argued that it wasn’t just the overall population size that caused innovation, but who these people were: It turns out that a greater percentage of eminent people of that time chose to become scientists rather than officers of the church or to go into the military.

…