The Age of Extraction: How Tech Platforms Conquered the Economy and Threaten Our Future Prosperity

by Tim Wu · 4 Nov 2025 · 246pp · 65,143 words

Robinson and Edward Chamberlin argued that imperfect competition or monopoly was the norm and that in reality, Marshall’s perfect competition was a rarity. Even Joseph Schumpeter would write that for most markets, “there seems to be no reason to expect to yield the results of perfect competition,” and that “in the

…

Privacy,” Harvard Law Review 4, no. 5 (1890). BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 15 13. The Persistent Dream of the Self-Correcting Economy Thomas K. McCraw, “Joseph Schumpeter on Competition,” Competition Policy International 8, no. 1 (2012). BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 1 John Kenneth Galbraith, “The Essential Galbraith,” Library of Congress, accessed October

The Road to Ruin: The Global Elites' Secret Plan for the Next Financial Crisis

by James Rickards · 15 Nov 2016 · 354pp · 105,322 words

part of what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He studied law and economics at the University of Vienna. There he was a classmate of Joseph Schumpeter’s and took his Ph.D. with Carl Menger, the father of Austrian economics. During the First World War Somary served as a central banker

…

, Russia, and Germany—are the same. Where is our new Somary? Who is the new raven? Somary also used the historical-cultural method favored by Joseph Schumpeter. In 1913, Somary was asked by the seven great powers of the day to reorganize the Chinese monetary system. He declined the role because he

…

Democracy (1942) Show me the man and I’ll find you the crime. Lavrentiy Beria, chief of the Secret Police (NKVD) under Stalin Schumpeter Reconsidered Joseph Schumpeter’s name conjures the phrase “creative destruction,” his best-known intellectual contribution, one of the most powerful economic insights of the twentieth century, with important

Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages

by Carlota Pérez · 1 Jan 2002

from their first beginnings to the time when they predominate in the structure and behavior of the economy. In his major work, Business Cycles (1939), Joseph Schumpeter, whilst interpreting the major waves of economic growth and technological transformation as ‘successive industrial revolutions’, insisted that these clusters of radical innovations also depended on

Make Your Own Job: How the Entrepreneurial Work Ethic Exhausted America

by Erik Baker · 13 Jan 2025 · 362pp · 132,186 words

-structural methodology of earlier German economists for neglecting the subjective states of economic actors. Austrian economists such as Friedrich von Wieser, Ludwig von Mises, and Joseph Schumpeter began to publish in the journal that Weber and Sombart helped to edit, the Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik, and Weber spent some time teaching

…

the fascination of gambling” which drives the entrepreneur, he wrote in 1914. Rather, “the impulse which drives him forward is the joyful power to create.” Joseph Schumpeter, a younger Austrian economist who studied both with Wieser and with the VfS in Berlin, was especially insistent that the entrepreneur embodied the nonrational psychology

…

as “we” rather than “them” or “it.” This sense of collective purpose flowed from the transformative mission set for the firm by the entrepreneur; as Joseph Schumpeter put it, the entrepreneur per se was distinguished from other kinds of business leaders by his determination to carry out some “new combination” of economic

…

he made a convert of L.J. Henderson.”44 It was in this reading group, typically called the “Pareto circle,” that Henderson and Mayo met Joseph Schumpeter, who moved to the United States to take up a professorship in the Harvard Economics Department in 1932. Like many people, Schumpeter found Henderson’s

…

industries too young yet to be subject to the steady grind of technological improvement. In the Depression era, under the influence of Frank Knight and Joseph Schumpeter, many American economists and other intellectuals learned to describe this process of industrial creativity as “entrepreneurial.” The economic theory of entrepreneurship imported from the German

…

by training, he had made his name in the United States with his wartime writings on totalitarianism and the values of Western industrial society. But Joseph Schumpeter had been a friend of his father in Vienna, and as he began to read widely in the academic literature on management in the mid

…

firms to stake out a “niche” for themselves in the marketplace, where at least for the time being they were insulated from competition. As in Joseph Schumpeter’s account of entrepreneurial “creative destruction,” the principal reward of innovation was a temporary monopoly position—a prospect all the more enticing in an economy

…

Cheetos—just to name 2023 releases.7 Journalists speculate, based on survey data, that Generation Z “may be the most entrepreneurial of all generations.”8 Joseph Schumpeter predicted in the 1940s that the greatest threat to the culture of entrepreneurialism was routinization: the absorption of entrepreneurship by the large corporation as a

…

solidarity, the invidious distinction between the value creation of white strivers and the idleness of the racialized poor. “My attitude toward Hitlerism is so astonishing,” Joseph Schumpeter confessed in his diary in 1939. Having once “attacked everything that Hitler stands for,” he wrote, “now I’m all but partisan and I am

…

, trans. Mortimer Epstein (London: T. F. Unwin, 1915), 203; Friedrich von Wieser, Social Economics, trans. A. Ford Hinrichs (New York: Adelphi, 1927 [orig. 1914]), 324; Joseph Schumpeter, The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle, trans. Redvers Opie (New York: Transaction Publishers, 2012 [trans

…

, February 27, 1938, TT10. 42Dale Carnegie, “Dale Carnegie Says: ‘What a Pleasure Work Is!’” Washington Post, February 6, 1938, TT8. 43As expressed most forcefully by Joseph Schumpeter in his treatment of rationalism and intellectualism in Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. 44Carnegie’s whole success philosophy draws an equivalence between reward and desert; Watts

…

. 8Schrader, Taxi Driver, 32. 9This and all subsequent quotations from Scorsese, Taxi Driver. 10Quoted in Robert Loring Allen, Opening Doors: The Life and Work of Joseph Schumpeter, vol. 2, America (Piscataway, NJ: Transaction, 1991), 66. 11Melinda Cooper, Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism (Princeton, NJ: Zone Books, 2017). 12Priya

…

, 176, 183, 206, 209, 219, 239, 259–60; informal, 217, 239; and innovation, 58, 120, 151; and John Birch, 220; and Joseph Campbell, 158; and Joseph Schumpeter, 52, 58, 62, 234; language of, 6; and managers, 8, 55, 101, 124, 190; and Manifest Destiny, 112; and masculinity, 113; and McDonald’s, 165

…

; and Horatio Alger, 24; and human capitalism, 155; inadequate, 6; informal, 216, 230, 237; and Jay Van Andel, 177; and job creation, 219–20; and Joseph Schumpeter, 65–66; language of, 6, 162; and leadership, 100; and lifestyle commodification, 15; and management, 130, 138, 189; minority, 130; and modernization, 119; New Age

The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times

by Giovanni Arrighi · 15 Mar 2010 · 7,371pp · 186,208 words

. But a dominant state may lead also in the sense that it draws other states onto its own path of development. Borrowing an expression from Joseph Schumpeter (1963: 89), this second kind of leadership can be designated as “leadership against one’s own will” because, over time, it enhances competition for power

…

the additional commitment of resources to stateand war-making involved in the territorial and commercial expansion of empire. In this connection we should note that Joseph Schumpeter’s (1955: 64-5) thesis that precapitalist state formations have been characterized by strong “objectless” tendencies “toward forcible expansion, without definite, utilitarian limits — that is

…

. This was certainly true in the short run, bearing in mind that, in these things, a century is even more of a “short run” than Joseph Schumpeter thought. But in the longer run, it was not the Venetians but the Genoese that went on to promote, monitor, and benefit from the first

…

underlie the recurrence of systemic cycles of accumulation and the transition from one cycle to another. THE “ENDLESS” ACCUMULATION OF CAPITAL 219 Reprise and Preview Joseph Schumpeter (1954: 163) once remarked that, in matters of capitalist development, a century is a “short run.” As it turns out, in matters of development of

…

was only a question of time before the crisis would re-emerge in more troublesome forms. Epilogue: Can Capitalism Survive Success? Some fifty years ago Joseph Schumpeter advanced the double thesis that “the actual and prospective performance of the capitalist system is such as to negative the idea of its breaking down

…

world’s cultures and civilizations. It was nonetheless also possible that the bifurcation would result in endless worldwide chaos. As I put it then, paraphrasing Joseph Schumpeter, before humanity chokes (or basks) in the dungeon (or paradise) of a Western-centered global empire or of an East Asiancentered world-market society, “it

The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires

by Tim Wu · 2 Nov 2010 · 418pp · 128,965 words

the promise of the telephone represents a pattern that recurs with a frequency embarrassing to the human race. “All knowledge and habit once acquired,” wrote Joseph Schumpeter, the great innovation theorist, “becomes as firmly rooted in ourselves as a railway embankment in the earth.” Schumpeter believed that our minds were, essentially, too

…

thinker of the twentieth century better understood that such winner-take-all contests were the very soul of the capitalist system than did the economist Joseph Schumpeter, the “prophet of innovation.” Schumpeter’s presence in the history of economics seems designed to displease everyone. His prose, his personality, and his ideas were

…

more generally replace radio, and by implication, destroy the Radio Corporation of America. He was a man who proved it is possible to defy both Joseph Schumpeter’s doctrine of creative destruction and, as he turned RCA into a television company, the adage that you can’t teach old dogs new tricks

…

Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (New York: Routledge, 2006) (1942). For more about his work see Robert Loring Allen, Opening Doors: The Life and Work of Joseph Schumpeter, Volume One—Europe (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1991); on his up-and-down life, see Richard Swedberg’s Schumpeter: A Biography (Princeton, NJ: Princeton

…

University Press, 1991); Thomas K. McCraw, Prophet of Innovation: Joseph Schumpeter and Creative Destruction (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2007). 17. Albert Bigelow Paine, In One Man’s Life: Being Chapters from the Personal & Business Career of

The Nature of Technology

by W. Brian Arthur · 6 Aug 2009 · 297pp · 77,362 words

evolution itself, is by no means new. It has been mooted about by various people for well over 100 years, among them the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter. In 1910 Schumpeter was twenty-seven, and he was concerned not directly with combination and technology but with combination in the economy. “To produce,” he

Good Profit: How Creating Value for Others Built One of the World's Most Successful Companies

by Charles de Ganahl Koch · 14 Sep 2015 · 261pp · 74,471 words

, long before the Internet threatened brick-and-mortar retailers with creative destruction. Successful businesspeople stand on ground that is “crumbling beneath their feet,”2 said Joseph Schumpeter, who taught at Harvard in the 1930s and ’40s and is one of the most important economists of the twentieth century. His observation about the

…

. Chapter 3: QUEENS, FACTORY GIRLS, AND SCHUMPETER 1. Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (New York: Harper Perennial, 2008), p. 67. 2. Cited in “Joseph Schumpeter: In Praise of Entrepreneurs,” Books and Arts section, The Economist, April 28, 2007, p. 94. 3. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, p. 84. 4. Ibid

The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest

by Edward Chancellor · 15 Aug 2022 · 829pp · 187,394 words

of a serpent.6 Proudhon’s rhetoric was high-flown and repetitive, and his economic analysis was not profound. In his History of Economic Analysis, Joseph Schumpeter lamented Proudhon’s complete inability to analyse. Even so, Proudhon had some original proposals. He wanted to nationalize the Banque de France, expand the money

…

importance. For Böhm-Bawerk, interest was ‘an organic necessity’.65 Irving Fisher called interest ‘too omnipresent a phenomenon to be eradicated’.66 In similar vein, Joseph Schumpeter stated that interest ‘permeates, as it were, the whole economic system’.67 The author of Das Kapital, an avowed enemy of interest, agreed with this

…

private seminars of Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk. Among the other seminar attendants were future luminaries of the Austrian school of economics, including Ludwig von Mises, Joseph Schumpeter and Friedrich Hayek. An axiom of the Austrian school was that interest is necessary so that investment and consumption decisions are co-ordinated over time

…

a fall in prices would hinder the curative process of recession and keep the economy in a state of imbalance. As another celebrated Austrian economist, Joseph Schumpeter, put it, deflation ‘restores the health of the monetary system’.75 Any attempt to avoid deflation, said Wilhelm Röpke, would result in ‘a prolongation and

…

in tandem.fn1 ‘Economic maturity is a bogey, the offspring of a body of doctrine both unsubstantiated and insubstantial,’ snorted Terborgh.6 Three years earlier, Joseph Schumpeter had anticipated much of Terborgh’s critique. In Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942), Schumpeter denied contemporary claims that the world was running out of innovations

…

living will come down … enterprising people will pick up the wrecks from less competent people. Andrew Mellon, 1932 In his book Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, Joseph Schumpeter describes capitalism as a ‘process of industrial mutation … that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new

…

or even prolonged stationariness of its economic conditions.’37 A couple of years before the appearance of The Road to Serfdom, Hayek’s Austrian contemporary Joseph Schumpeter published an equally notable book. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942) is best known for introducing the idea of creative destruction (as discussed in Chapter 10

…

: A Critical History of Economical Theory, vol. I (South Holland, Ill., 1959), p. 27. 66. Fisher, Theory of Interest, in Works, IX, p. 3. 67. Joseph Schumpeter, Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle (New Brunswick, NJ, 1983), p. 198. 68. Cited by Jacques

…

. 108. 3. Daniel Defoe, Daniel Defoe: His Life, and Recently Discovered Writings: Extending from 1716 to 1729, ed. William Lee (London, 1869), p. 189. 4. Joseph Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis (New York, 1954), p. 295 5. Ibid., p. 322. 6. John Law, Oeuvres Completes, vol. I, ed. Paul Harsin (Paris, 1934

…

. 73. Alfred Marshall, Official Papers (Cambridge, 1926), p. 19. 74. F. A. Hayek, Prices and Production and Other Works (Auburn, Ala., 2008), p. 5. 75. Joseph Schumpeter, Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle (New Brunswick, NJ, 1983), p. 110. 76. Röpke, Crises and

…

American Economic Association, 9 (1), January 1894: 56–7. 3. Joseph A. Schumpeter, Ten Great Economists: From Marx to Keynes (Oxford, 1969), p. 162. 4. Joseph Schumpeter, Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle (New Brunswick, NJ, 1983), p. 210. 5. James Grant, ‘Shot

…

Critical History of Economical Theory, vol. I (South Holland, Ill., 1959), p. 183. 3. Cassel, Nature and Necessity of Interest, p. 39. 4. Cited by Joseph Schumpeter, Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle (New Brunswick, NJ, 1983), pp. 201–3; Irving Fisher, Elementary

…

Quantitative Easing (London, 2015), p. 133. 2. Arthur E. Monroe, Early Economic Thought: Selected Writings from Aristotle to Hume (Mineola, NY, 2006), p. 301. 3. Joseph Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis (New York, 1954), pp. 300–302. 4. Monroe, Early Economic Thought, p. 304. 5. Ibid., p. 306. 6. Yueran Ma and

The Marginal Revolutionaries: How Austrian Economists Fought the War of Ideas

by Janek Wasserman · 23 Sep 2019 · 470pp · 130,269 words

and socialism and leading exponents of liberal ideology. In the interwar era, a new generation emerged to advance earlier intellectual and ideological efforts. First Mises, Joseph Schumpeter, and Hans Mayer, then Friedrich Hayek, Gottfried Haberler, and Oskar Morgenstern made their reputations by the end of the 1920s. They developed innovative understandings of

…

most prominent example of these confrontations, and it created a counterpole to the hegemonic German approach in Vienna. The Methodenstreit: “A History of Wasted Energies” Joseph Schumpeter, a later member of the Austrian School, rendered a negative judgment of the “debate over methods” in his canonical history of economic thought. He explained

…

English, making it one of the few German works afforded such a treatment. It went through four editions and inspired several generations of scholars, including Joseph Schumpeter, Ludwig von Mises, and Friedrich Hayek. It also provoked ardent detractors. Henry Carey Baird, son of the American economist Henry Carey, called the book “the

…

and its key members Carl Menger, Friedrich von Wieser, and Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk. Bukharin also recognized a rising group, including Ludwig von Mises and Joseph Schumpeter, whom he had met and debated in Böhm’s seminar. The Böhm seminar became a significant site of intellectual disputation in a city famous for

…

Mises—illustrates these dynamics. Each man wrestled with conformity and creativity, viewing his relationship to the Austrian School as a source of inspiration and opposition. Joseph Schumpeter’s Early Successes Johanna Schumpeter always envisioned grand things for her son, Jozsi. A member of a prosperous German Moravian family, she moved to Graz

…

circumstances, younger Austrian economists adapted by seeking new means of making their names and assuring their influence. In the final days of the war, Wieser, Joseph Schumpeter, Ludwig von Mises, and others turned from bureaucratic posts to public outlets. They advocated political and economic solutions in newspaper articles, pamphlets, and short books

…

cultural values and enjoyed unparalleled patronage from the RF. In proportion to the country’s size, Austria produced more fellows than any other European country. Joseph Schumpeter, now in Germany, noted the success of the Austrian economists while lamenting German deficiencies. Oskar Morgenstern also observed that Austrians outstripped Germans in international reputation

…

his 1926 death signaled a major loss. The Austrian School had to reinvent itself in trying circumstances. Despite connections in the government and the academy, Joseph Schumpeter, Ludwig von Mises, and Hans Mayer confronted major obstacles in their pursuit of influence. With political access and academic opportunities limited, these men refashioned themselves

…

of the recurrence of periods of depression.” The final product, Prosperity and Depression, was immediately hailed as a seminal contribution. No less an authority than Joseph Schumpeter regarded Haberler’s work as a “masterly presentation of the modern material.” The London Times also acknowledged the work’s significance: “in a mere two

…

was losing its spirit, its Geist. In 1934, Haberler took a position with the League of Nations Economic Section in Geneva. With the support of Joseph Schumpeter, Haberler secured a professorship at Harvard in 1936. This act of generosity was characteristic of Schumpeter. From Cambridge, he helped German intellectuals escape National Socialism

…

that Mises had left to offer.20 If Mises and Hayek found modern economics constraining for their broader social and political projects, Oskar Morgenstern and Joseph Schumpeter grew exasperated by the discipline’s inability to incorporate new trends in mathematics and the social sciences. They, too, found their work underappreciated. Between the

…

to penetrate the more fundamental issues.” Mises and Hayek rejected the work outright, the latter finding it incoherent at best and rude at worst.21 Joseph Schumpeter also fought unsuccessfully against prevailing trends in economics in the name of a more precise science. His 1939 attempt, Business Cycles, met with shrugs. He

…

employment. Despite ample savings and an affordable rent-controlled apartment, his first years in Manhattan were trying. Unlike his younger Austrian colleagues or his contemporary Joseph Schumpeter, Mises did not receive a permanent academic appointment, nor did he garner academic attention for his polemical writing. Eventually he received a series of one

…

neoliberalism, which featured William Rappard, Wilhelm Röpke, and Mises. By the time Haberler applied for jobs in the United States, no less an authority than Joseph Schumpeter called him “the best horse in the Viennese stables.” The elder Austrian attracted Haberler to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he worked for the remainder of his

…

proceeded to excommunicate Austrians who did not fit his understanding of the school. Viennese who did not conform—Rudolf Auspitz, Richard Lieben, and, most crucially, Joseph Schumpeter—were treated as apostates. Gone, too, was the figure who informed much of Kauder’s early knowledge of the Austrian movement: Hans Mayer. The Austrian

…

’s work, which drew a straight line from Menger to Böhm to Mises, Machlup excluded seminal figures like Rudolf Auspitz, Richard Lieben, Emil Sax, and Joseph Schumpeter. He also included American Misesians. Machlup’s friend Herbert Furth rejected this conceptualization: “You know that I consider Hayek the ‘Dean’ of the Austrian School

…

economist, extolled Haberler’s contributions to the Austrian tradition and the economics profession: “Of the three great Austrian economists who elevated world and American economics—Joseph Schumpeter, Friedrich Hayek and Gottfried Haberler—it was Haberler who was the ‘economist’s economist,’ a creative and eclectic advocate of free trade.” Samuelson’s verdict

…

, and Hayek, that phase seemed at an end. He decried the disregard of values, or preanalytic “vision,” in shaping the social analyses of economists. Invoking Joseph Schumpeter, he argued for a broader philosophical perspective that might help social scientists to structure our social reality and imbue it with meaning. Unwittingly Heilbroner evoked

…

, Friedrich von Wieser, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, and especially Carl Menger saw a spike in their popularity in the early 1990s. Last but not least, Joseph Schumpeter became far and away the most popular Austrian. He reached an all-time high in 1993. JSTOR results on scholarly publications suggest similar trends, though

…

common cause with the left in toto. The quest for a progressive Austrianism remains unfulfilled.37 Marginal Revolutionaries In the monumental History of Economic Analysis, Joseph Schumpeter offered a sociological description of intellectual schools that encapsulates the subject of this book: We must never forget that genuine schools are sociological realities—living

…

Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University, Durham, NC. Carl Menger Papers. Karl Menger Papers. Oskar Morgenstern Papers. Harvard University Archives. Cambridge, MA. Alexander Gerschenkron Papers. Joseph Schumpeter Papers. Haus-, Hof-, und Staatsarchiv. Vienna, Austria. Richard Schüller Papers. Hoover Institution Archives. Stanford, CA. Friedrich Hayek Papers. Fritz Machlup Papers. Gottfried Haberler Papers. Karl

…

, Johanna. Markets in the Name of Socialism. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011. Boehm, Stephan. “The Best Horse in the Viennese Stables: Gottfried Haberler and Joseph Schumpeter.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 25, no. 1 (2015): 107–15. Boettke, Peter. “Austrian School of Economics.” In Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, 2nd ed. http://www

…

, 1867–83. ———. “Theses on Feuerbach.” 1845. Translated by Cyril Smith, 2002. Marxists Internet Archive. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/theses. März, Eduard. Joseph Schumpeter: Scholar, Teacher, and Politician. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991. Mataja, Victor. Der Unternehmergewinn. Vienna: Holder, 1884. Mayer, Jane. Dark Money: The Secret History

…

. “A Kirznerian Economic History of the Modern World.” DeirdreMcCloskey.com, June 17, 2011. http://www.deirdremccloskey.com/editorials/kirzner.php. McCraw, Thomas. Prophet of Innovation: Joseph Schumpeter and Creative Destruction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007. McGirr, Lisa. Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American Right. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Profiting Without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All

by Costas Lapavitsas · 14 Aug 2013 · 554pp · 158,687 words

Visions of Inequality: From the French Revolution to the End of the Cold War

by Branko Milanovic · 9 Oct 2023

Capitalism and Its Critics: A History: From the Industrial Revolution to AI

by John Cassidy · 12 May 2025 · 774pp · 238,244 words

A Little History of Economics

by Niall Kishtainy · 15 Jan 2017 · 272pp · 83,798 words

Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government

by Robert Higgs and Arthur A. Ekirch, Jr. · 15 Jan 1987

Innovation and Its Enemies

by Calestous Juma · 20 Mar 2017

Masters of Management: How the Business Gurus and Their Ideas Have Changed the World—for Better and for Worse

by Adrian Wooldridge · 29 Nov 2011 · 460pp · 131,579 words

Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can't Explain the Modern World

by Deirdre N. McCloskey · 15 Nov 2011 · 1,205pp · 308,891 words

Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century

by J. Bradford Delong · 6 Apr 2020 · 593pp · 183,240 words

Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future

by Paul Mason · 29 Jul 2015 · 378pp · 110,518 words

Buying Time: The Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism

by Wolfgang Streeck · 1 Jan 2013 · 353pp · 81,436 words

Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age

by W. Bernard Carlson · 11 May 2013 · 733pp · 184,118 words

The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths

by Mariana Mazzucato · 1 Jan 2011 · 382pp · 92,138 words

Green Tyranny: Exposing the Totalitarian Roots of the Climate Industrial Complex

by Rupert Darwall · 2 Oct 2017 · 451pp · 115,720 words

The Innovation Illusion: How So Little Is Created by So Many Working So Hard

by Fredrik Erixon and Bjorn Weigel · 3 Oct 2016 · 504pp · 126,835 words

Rethinking Capitalism: Economics and Policy for Sustainable and Inclusive Growth

by Michael Jacobs and Mariana Mazzucato · 31 Jul 2016 · 370pp · 102,823 words

Keynes Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics

by Nicholas Wapshott · 10 Oct 2011 · 494pp · 132,975 words

Does Capitalism Have a Future?

by Immanuel Wallerstein, Randall Collins, Michael Mann, Georgi Derluguian, Craig Calhoun, Stephen Hoye and Audible Studios · 15 Nov 2013 · 238pp · 73,121 words

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

by Shoshana Zuboff · 15 Jan 2019 · 918pp · 257,605 words

Big Three in Economics: Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and John Maynard Keynes

by Mark Skousen · 22 Dec 2006 · 330pp · 77,729 words

Capitalism in America: A History

by Adrian Wooldridge and Alan Greenspan · 15 Oct 2018 · 585pp · 151,239 words

The Social Life of Money

by Nigel Dodd · 14 May 2014 · 700pp · 201,953 words

The Great Economists: How Their Ideas Can Help Us Today

by Linda Yueh · 15 Mar 2018 · 374pp · 113,126 words

Crisis Economics: A Crash Course in the Future of Finance

by Nouriel Roubini and Stephen Mihm · 10 May 2010 · 491pp · 131,769 words

What Would the Great Economists Do?: How Twelve Brilliant Minds Would Solve Today's Biggest Problems

by Linda Yueh · 4 Jun 2018 · 453pp · 117,893 words

Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts, and the Death of Freedom

by Grace Blakeley · 11 Mar 2024 · 371pp · 137,268 words

The end of history and the last man

by Francis Fukuyama · 28 Feb 2006 · 446pp · 578 words

Hubris: Why Economists Failed to Predict the Crisis and How to Avoid the Next One

by Meghnad Desai · 15 Feb 2015 · 270pp · 73,485 words

The Classical School

by Callum Williams · 19 May 2020 · 288pp · 89,781 words

23 Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalism

by Ha-Joon Chang · 1 Jan 2010 · 365pp · 88,125 words

Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy in the Aftermath of Crisis

by Anatole Kaletsky · 22 Jun 2010 · 484pp · 136,735 words

Blue Ocean Strategy, Expanded Edition: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant

by W. Chan Kim and Renée A. Mauborgne · 20 Jan 2014 · 287pp · 80,180 words

Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea

by Mark Blyth · 24 Apr 2013 · 576pp · 105,655 words

Can Democracy Work?: A Short History of a Radical Idea, From Ancient Athens to Our World

by James Miller · 17 Sep 2018 · 370pp · 99,312 words

Work in the Future The Automation Revolution-Palgrave MacMillan (2019)

by Robert Skidelsky Nan Craig · 15 Mar 2020

Capital Ideas Evolving

by Peter L. Bernstein · 3 May 2007

Making Sense of Chaos: A Better Economics for a Better World

by J. Doyne Farmer · 24 Apr 2024 · 406pp · 114,438 words

The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order

by Benn Steil · 14 May 2013 · 710pp · 164,527 words

Capital Ideas: The Improbable Origins of Modern Wall Street

by Peter L. Bernstein · 19 Jun 2005 · 425pp · 122,223 words

What's Wrong With Economics: A Primer for the Perplexed

by Robert Skidelsky · 3 Mar 2020 · 290pp · 76,216 words

The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies

by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee · 20 Jan 2014 · 339pp · 88,732 words

Going Solo: The Extraordinary Rise and Surprising Appeal of Living Alone

by Eric Klinenberg · 1 Jan 2012 · 291pp · 88,879 words

A World Without Work: Technology, Automation, and How We Should Respond

by Daniel Susskind · 14 Jan 2020 · 419pp · 109,241 words

The State and the Stork: The Population Debate and Policy Making in US History

by Derek S. Hoff · 30 May 2012

The Great Disruption: Why the Climate Crisis Will Bring on the End of Shopping and the Birth of a New World

by Paul Gilding · 28 Mar 2011 · 337pp · 103,273 words

The Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of Automation

by Carl Benedikt Frey · 17 Jun 2019 · 626pp · 167,836 words

Seven Crashes: The Economic Crises That Shaped Globalization

by Harold James · 15 Jan 2023 · 469pp · 137,880 words

Made to Break: Technology and Obsolescence in America

by Giles Slade · 14 Apr 2006 · 384pp · 89,250 words

The End of Power: From Boardrooms to Battlefields and Churches to States, Why Being in Charge Isn’t What It Used to Be

by Moises Naim · 5 Mar 2013 · 474pp · 120,801 words

The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves

by Matt Ridley · 17 May 2010 · 462pp · 150,129 words

The Internet Is Not the Answer

by Andrew Keen · 5 Jan 2015 · 361pp · 81,068 words

A Pelican Introduction Economics: A User's Guide

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 May 2014 · 385pp · 111,807 words

Sabotage: The Financial System's Nasty Business

by Anastasia Nesvetailova and Ronen Palan · 28 Jan 2020 · 218pp · 62,889 words

Escape From Rome: The Failure of Empire and the Road to Prosperity

by Walter Scheidel · 14 Oct 2019 · 1,014pp · 237,531 words

The Digital Party: Political Organisation and Online Democracy

by Paolo Gerbaudo · 19 Jul 2018 · 302pp · 84,881 words

The New Depression: The Breakdown of the Paper Money Economy

by Richard Duncan · 2 Apr 2012 · 248pp · 57,419 words

Capitalism: Money, Morals and Markets

by John Plender · 27 Jul 2015 · 355pp · 92,571 words

The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World (Hardback) - Common

by Alan Greenspan · 14 Jun 2007

The Evolution of Everything: How New Ideas Emerge

by Matt Ridley · 395pp · 116,675 words

Dual Transformation: How to Reposition Today's Business While Creating the Future

by Scott D. Anthony and Mark W. Johnson · 27 Mar 2017 · 293pp · 78,439 words

The Limits of the Market: The Pendulum Between Government and Market

by Paul de Grauwe and Anna Asbury · 12 Mar 2017

The Paypal Wars: Battles With Ebay, the Media, the Mafia, and the Rest of Planet Earth

by Eric M. Jackson · 15 Jan 2004 · 398pp · 108,889 words

Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century

by Geoffrey Parker · 29 Apr 2013 · 1,773pp · 486,685 words

Prosperity Without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow

by Tim Jackson · 8 Dec 2016 · 573pp · 115,489 words

Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the World

by Branko Milanovic · 23 Sep 2019

Wealth and Poverty: A New Edition for the Twenty-First Century

by George Gilder · 30 Apr 1981 · 590pp · 153,208 words

The Great Race: The Global Quest for the Car of the Future

by Levi Tillemann · 20 Jan 2015 · 431pp · 107,868 words

The Reckoning: Financial Accountability and the Rise and Fall of Nations

by Jacob Soll · 28 Apr 2014 · 382pp · 105,166 words

Against Intellectual Monopoly

by Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine · 6 Jul 2008 · 607pp · 133,452 words

Where Does Money Come From?: A Guide to the UK Monetary & Banking System

by Josh Ryan-Collins, Tony Greenham, Richard Werner and Andrew Jackson · 14 Apr 2012

Markets, State, and People: Economics for Public Policy

by Diane Coyle · 14 Jan 2020 · 384pp · 108,414 words

The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor

by William Easterly · 4 Mar 2014 · 483pp · 134,377 words

How Markets Fail: The Logic of Economic Calamities

by John Cassidy · 10 Nov 2009 · 545pp · 137,789 words

Cheap: The High Cost of Discount Culture

by Ellen Ruppel Shell · 2 Jul 2009 · 387pp · 110,820 words

A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy

by Joel Mokyr · 8 Jan 2016 · 687pp · 189,243 words

The Inner Lives of Markets: How People Shape Them—And They Shape Us

by Tim Sullivan · 6 Jun 2016 · 252pp · 73,131 words

Unelected Power: The Quest for Legitimacy in Central Banking and the Regulatory State

by Paul Tucker · 21 Apr 2018 · 920pp · 233,102 words

Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus: How Growth Became the Enemy of Prosperity

by Douglas Rushkoff · 1 Mar 2016 · 366pp · 94,209 words

Money and Government: The Past and Future of Economics

by Robert Skidelsky · 13 Nov 2018

Value of Everything: An Antidote to Chaos The

by Mariana Mazzucato · 25 Apr 2018 · 457pp · 125,329 words

The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality

by Katharina Pistor · 27 May 2019 · 316pp · 117,228 words

Boom and Bust: A Global History of Financial Bubbles

by William Quinn and John D. Turner · 5 Aug 2020 · 297pp · 108,353 words

The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism

by Joyce Appleby · 22 Dec 2009 · 540pp · 168,921 words

Owning the Earth: The Transforming History of Land Ownership

by Andro Linklater · 12 Nov 2013 · 603pp · 182,826 words

The Great Reset: How the Post-Crash Economy Will Change the Way We Live and Work

by Richard Florida · 22 Apr 2010 · 265pp · 74,941 words

The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Competition

by Jonathan Tepper · 20 Nov 2018 · 417pp · 97,577 words

Rentier Capitalism: Who Owns the Economy, and Who Pays for It?

by Brett Christophers · 17 Nov 2020 · 614pp · 168,545 words

Samuelson Friedman: The Battle Over the Free Market

by Nicholas Wapshott · 2 Aug 2021 · 453pp · 122,586 words

Nervous States: Democracy and the Decline of Reason

by William Davies · 26 Feb 2019 · 349pp · 98,868 words

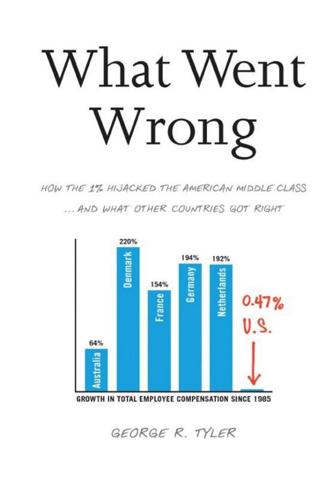

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by George R. Tyler · 15 Jul 2013 · 772pp · 203,182 words

Double Entry: How the Merchants of Venice Shaped the Modern World - and How Their Invention Could Make or Break the Planet

by Jane Gleeson-White · 14 May 2011 · 274pp · 66,721 words

Future Politics: Living Together in a World Transformed by Tech

by Jamie Susskind · 3 Sep 2018 · 533pp

A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things: A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet

by Raj Patel and Jason W. Moore · 16 Oct 2017 · 335pp · 89,924 words

Wall Street: How It Works And for Whom

by Doug Henwood · 30 Aug 1998 · 586pp · 159,901 words

Who's Your City?: How the Creative Economy Is Making Where to Live the Most Important Decision of Your Life

by Richard Florida · 28 Jun 2009 · 325pp · 73,035 words

War and Gold: A Five-Hundred-Year History of Empires, Adventures, and Debt

by Kwasi Kwarteng · 12 May 2014 · 632pp · 159,454 words

Them And Us: Politics, Greed And Inequality - Why We Need A Fair Society

by Will Hutton · 30 Sep 2010 · 543pp · 147,357 words

The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World

by Adrian Wooldridge · 2 Jun 2021 · 693pp · 169,849 words

Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder

by Nassim Nicholas Taleb · 27 Nov 2012 · 651pp · 180,162 words

Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist

by Kate Raworth · 22 Mar 2017 · 403pp · 111,119 words

Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism

by David Harvey · 3 Apr 2014 · 464pp · 116,945 words

The Fair Trade Scandal: Marketing Poverty to Benefit the Rich

by Ndongo Sylla · 21 Jan 2014 · 193pp · 63,618 words

The Economics Anti-Textbook: A Critical Thinker's Guide to Microeconomics

by Rod Hill and Anthony Myatt · 15 Mar 2010

The New Harvest: Agricultural Innovation in Africa

by Calestous Juma · 27 May 2017

The Price of Tomorrow: Why Deflation Is the Key to an Abundant Future

by Jeff Booth · 14 Jan 2020 · 180pp · 55,805 words

Machine, Platform, Crowd: Harnessing Our Digital Future

by Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson · 26 Jun 2017 · 472pp · 117,093 words

The Most Powerful Idea in the World: A Story of Steam, Industry, and Invention

by William Rosen · 31 May 2010 · 420pp · 124,202 words

Reinventing Capitalism in the Age of Big Data

by Viktor Mayer-Schönberger and Thomas Ramge · 27 Feb 2018 · 267pp · 72,552 words

Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire

by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri · 1 Jan 2004 · 475pp · 149,310 words

The Myth of the Rational Market: A History of Risk, Reward, and Delusion on Wall Street

by Justin Fox · 29 May 2009 · 461pp · 128,421 words

Capital Without Borders

by Brooke Harrington · 11 Sep 2016 · 358pp · 104,664 words

Who Needs the Fed?: What Taylor Swift, Uber, and Robots Tell Us About Money, Credit, and Why We Should Abolish America's Central Bank

by John Tamny · 30 Apr 2016 · 268pp · 74,724 words

Giving the Devil His Due: Reflections of a Scientific Humanist

by Michael Shermer · 8 Apr 2020 · 677pp · 121,255 words

Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, From the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First

by Frank Trentmann · 1 Dec 2015 · 1,213pp · 376,284 words

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World

by Niall Ferguson · 13 Nov 2007 · 471pp · 124,585 words

Bad Samaritans: The Guilty Secrets of Rich Nations and the Threat to Global Prosperity

by Ha-Joon Chang · 4 Jul 2007 · 347pp · 99,317 words

The Golden Passport: Harvard Business School, the Limits of Capitalism, and the Moral Failure of the MBA Elite

by Duff McDonald · 24 Apr 2017 · 827pp · 239,762 words

Adam Smith: Father of Economics

by Jesse Norman · 30 Jun 2018

Animal Spirits: The American Pursuit of Vitality From Camp Meeting to Wall Street

by Jackson Lears

Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation

by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber · 29 Oct 2024 · 292pp · 106,826 words

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History

by Kurt Andersen · 14 Sep 2020 · 486pp · 150,849 words

The Power Elite

by C. Wright Mills and Alan Wolfe · 1 Jan 1956 · 568pp · 174,089 words

End This Depression Now!

by Paul Krugman · 30 Apr 2012 · 267pp · 71,123 words

Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr.

by Ron Chernow · 1 Jan 1997 · 1,106pp · 335,322 words

The Haves and the Have-Nots: A Brief and Idiosyncratic History of Global Inequality

by Branko Milanovic · 15 Dec 2010 · 251pp · 69,245 words

The New Geography of Jobs

by Enrico Moretti · 21 May 2012 · 403pp · 87,035 words

Radical Markets: Uprooting Capitalism and Democracy for a Just Society

by Eric Posner and E. Weyl · 14 May 2018 · 463pp · 105,197 words

Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism Is Turning the Internet Against Democracy

by Robert W. McChesney · 5 Mar 2013 · 476pp · 125,219 words

Money: The Unauthorized Biography

by Felix Martin · 5 Jun 2013 · 357pp · 110,017 words

Consumed: How Markets Corrupt Children, Infantilize Adults, and Swallow Citizens Whole

by Benjamin R. Barber · 1 Jan 2007 · 498pp · 145,708 words

European Spring: Why Our Economies and Politics Are in a Mess - and How to Put Them Right

by Philippe Legrain · 22 Apr 2014 · 497pp · 150,205 words

The Third Pillar: How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind

by Raghuram Rajan · 26 Feb 2019 · 596pp · 163,682 words

The Warhol Economy

by Elizabeth Currid-Halkett · 15 Jan 2020 · 320pp · 90,115 words

The End of the Free Market: Who Wins the War Between States and Corporations?

by Ian Bremmer · 12 May 2010 · 247pp · 68,918 words

The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age

by Tim Wu · 14 Jun 2018 · 128pp · 38,847 words

Irrational Exuberance: With a New Preface by the Author

by Robert J. Shiller · 15 Feb 2000 · 319pp · 106,772 words

Milton Friedman: A Biography

by Lanny Ebenstein · 23 Jan 2007 · 298pp · 95,668 words

Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism

by George A. Akerlof and Robert J. Shiller · 1 Jan 2009 · 471pp · 97,152 words

The Job: The Future of Work in the Modern Era

by Ellen Ruppel Shell · 22 Oct 2018 · 402pp · 126,835 words

How to Fix Copyright

by William Patry · 3 Jan 2012 · 336pp · 90,749 words

Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 Dec 2007 · 334pp · 98,950 words

The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists' Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics

by William R. Easterly · 1 Aug 2002 · 355pp · 63 words

The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine’s Computer Age

by Robert Wachter · 7 Apr 2015 · 309pp · 114,984 words

Leading From the Emerging Future: From Ego-System to Eco-System Economies

by Otto Scharmer and Katrin Kaufer · 14 Apr 2013 · 351pp · 93,982 words

Wasps: The Splendors and Miseries of an American Aristocracy

by Michael Knox Beran · 2 Aug 2021 · 800pp · 240,175 words

Arguing With Zombies: Economics, Politics, and the Fight for a Better Future

by Paul Krugman · 28 Jan 2020 · 446pp · 117,660 words

Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City

by Richard Sennett · 9 Apr 2018

Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution

by Howard Rheingold · 24 Dec 2011

The Capitalist Manifesto

by Johan Norberg · 14 Jun 2023 · 295pp · 87,204 words

Stealth of Nations

by Robert Neuwirth · 18 Oct 2011 · 340pp · 91,387 words

Culture and Imperialism

by Edward W. Said · 29 May 1994 · 549pp · 170,495 words

Open Standards and the Digital Age: History, Ideology, and Networks (Cambridge Studies in the Emergence of Global Enterprise)

by Andrew L. Russell · 27 Apr 2014 · 675pp · 141,667 words

How Asia Works

by Joe Studwell · 1 Jul 2013 · 868pp · 147,152 words

Good Economics for Hard Times: Better Answers to Our Biggest Problems

by Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo · 12 Nov 2019 · 470pp · 148,730 words

Cogs and Monsters: What Economics Is, and What It Should Be

by Diane Coyle · 11 Oct 2021 · 305pp · 75,697 words

The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking and the Future of the Global Economy

by Mervyn King · 3 Mar 2016 · 464pp · 139,088 words

Trust: The Social Virtue and the Creation of Prosperity

by Francis Fukuyama · 1 Jan 1995 · 585pp · 165,304 words

Stuffocation

by James Wallman · 6 Dec 2013 · 296pp · 82,501 words

Finance and the Good Society

by Robert J. Shiller · 1 Jan 2012 · 288pp · 16,556 words

The Green New Deal: Why the Fossil Fuel Civilization Will Collapse by 2028, and the Bold Economic Plan to Save Life on Earth

by Jeremy Rifkin · 9 Sep 2019 · 327pp · 84,627 words

Broken Markets: A User's Guide to the Post-Finance Economy

by Kevin Mellyn · 18 Jun 2012 · 183pp · 17,571 words

Winds of Change

by Peter Hennessy · 27 Aug 2019 · 891pp · 220,950 words

Exceptional People: How Migration Shaped Our World and Will Define Our Future

by Ian Goldin, Geoffrey Cameron and Meera Balarajan · 20 Dec 2010 · 482pp · 117,962 words

The Unbanking of America: How the New Middle Class Survives

by Lisa Servon · 10 Jan 2017 · 279pp · 76,796 words

Creative Intelligence: Harnessing the Power to Create, Connect, and Inspire

by Bruce Nussbaum · 5 Mar 2013 · 385pp · 101,761 words

Bad Money: Reckless Finance, Failed Politics, and the Global Crisis of American Capitalism

by Kevin Phillips · 31 Mar 2008 · 422pp · 113,830 words

The Internet Trap: How the Digital Economy Builds Monopolies and Undermines Democracy

by Matthew Hindman · 24 Sep 2018

Liberalism at Large: The World According to the Economist

by Alex Zevin · 12 Nov 2019 · 767pp · 208,933 words

Adaptive Markets: Financial Evolution at the Speed of Thought

by Andrew W. Lo · 3 Apr 2017 · 733pp · 179,391 words

The Billionaire Raj: A Journey Through India's New Gilded Age

by James Crabtree · 2 Jul 2018 · 442pp · 130,526 words

The Great Wave: The Era of Radical Disruption and the Rise of the Outsider

by Michiko Kakutani · 20 Feb 2024 · 262pp · 69,328 words

The Impulse Society: America in the Age of Instant Gratification

by Paul Roberts · 1 Sep 2014 · 324pp · 92,805 words

The Production of Money: How to Break the Power of Banks

by Ann Pettifor · 27 Mar 2017 · 182pp · 53,802 words

Restarting the Future: How to Fix the Intangible Economy

by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake · 4 Apr 2022 · 338pp · 85,566 words

The People's Republic of Walmart: How the World's Biggest Corporations Are Laying the Foundation for Socialism

by Leigh Phillips and Michal Rozworski · 5 Mar 2019 · 202pp · 62,901 words

As the Future Catches You: How Genomics & Other Forces Are Changing Your Work, Health & Wealth

by Juan Enriquez · 15 Feb 2001 · 239pp · 45,926 words

Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream

by Nicholas Lemann · 9 Sep 2019 · 354pp · 118,970 words

Foolproof: Why Safety Can Be Dangerous and How Danger Makes Us Safe

by Greg Ip · 12 Oct 2015 · 309pp · 95,495 words

The End of Accounting and the Path Forward for Investors and Managers (Wiley Finance)

by Feng Gu · 26 Jun 2016

The Global Auction: The Broken Promises of Education, Jobs, and Incomes

by Phillip Brown, Hugh Lauder and David Ashton · 3 Nov 2010 · 209pp · 80,086 words

Economists and the Powerful

by Norbert Haring, Norbert H. Ring and Niall Douglas · 30 Sep 2012 · 261pp · 103,244 words

The Future of Capitalism: Facing the New Anxieties

by Paul Collier · 4 Dec 2018 · 310pp · 85,995 words

The Politics Industry: How Political Innovation Can Break Partisan Gridlock and Save Our Democracy

by Katherine M. Gehl and Michael E. Porter · 14 Sep 2020 · 627pp · 89,295 words

Growth: A Reckoning

by Daniel Susskind · 16 Apr 2024 · 358pp · 109,930 words

Dealers of Lightning

by Michael A. Hiltzik · 27 Apr 2000 · 559pp · 157,112 words

Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism

by Anne Case and Angus Deaton · 17 Mar 2020 · 421pp · 110,272 words

Imperial Ambitions: Conversations on the Post-9/11 World

by Noam Chomsky and David Barsamian · 4 Oct 2005 · 165pp · 47,405 words

Hacking Capitalism

by Söderberg, Johan; Söderberg, Johan;

Arriving Today: From Factory to Front Door -- Why Everything Has Changed About How and What We Buy

by Christopher Mims · 13 Sep 2021 · 385pp · 112,842 words

The Future Is Faster Than You Think: How Converging Technologies Are Transforming Business, Industries, and Our Lives

by Peter H. Diamandis and Steven Kotler · 28 Jan 2020 · 501pp · 114,888 words

Can It Happen Here?: Authoritarianism in America

by Cass R. Sunstein · 6 Mar 2018 · 434pp · 117,327 words

The Origins of the Urban Crisis

by Sugrue, Thomas J.

The Atlantic and Its Enemies: A History of the Cold War

by Norman Stone · 15 Feb 2010 · 851pp · 247,711 words

Everything Is Obvious: *Once You Know the Answer

by Duncan J. Watts · 28 Mar 2011 · 327pp · 103,336 words

Plutocrats: The Rise of the New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else

by Chrystia Freeland · 11 Oct 2012 · 481pp · 120,693 words

This Could Be Our Future: A Manifesto for a More Generous World

by Yancey Strickler · 29 Oct 2019 · 254pp · 61,387 words

Civilization: The West and the Rest

by Niall Ferguson · 28 Feb 2011 · 790pp · 150,875 words

Open: The Story of Human Progress

by Johan Norberg · 14 Sep 2020 · 505pp · 138,917 words

The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism

by Edward E. Baptist · 24 Oct 2016

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab · 7 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

Ghost Road: Beyond the Driverless Car

by Anthony M. Townsend · 15 Jun 2020 · 362pp · 97,288 words

Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World

by Adam Grant · 2 Feb 2016 · 410pp · 101,260 words

Silicon City: San Francisco in the Long Shadow of the Valley

by Cary McClelland · 8 Oct 2018 · 225pp · 70,241 words

Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires

by Douglas Rushkoff · 7 Sep 2022 · 205pp · 61,903 words

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab and Peter Vanham · 27 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

Money Free and Unfree

by George A. Selgin · 14 Jun 2017 · 454pp · 134,482 words

Prediction Machines: The Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence

by Ajay Agrawal, Joshua Gans and Avi Goldfarb · 16 Apr 2018 · 345pp · 75,660 words

The Right to Earn a Living: Economic Freedom and the Law

by Timothy Sandefur · 16 Aug 2010 · 399pp · 155,913 words

The Cultural Logic of Computation

by David Golumbia · 31 Mar 2009 · 268pp · 109,447 words

Capitalism and Freedom

by Milton Friedman · 1 Jan 1962 · 275pp · 77,955 words

City: Urbanism and Its End

by Douglas W. Rae · 15 Jan 2003 · 537pp · 200,923 words

People, Power, and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 22 Apr 2019 · 462pp · 129,022 words

The Long Good Buy: Analysing Cycles in Markets

by Peter Oppenheimer · 3 May 2020 · 333pp · 76,990 words

How Much Is Enough?: Money and the Good Life

by Robert Skidelsky and Edward Skidelsky · 18 Jun 2012 · 279pp · 87,910 words

Bezonomics: How Amazon Is Changing Our Lives and What the World's Best Companies Are Learning From It

by Brian Dumaine · 11 May 2020 · 411pp · 98,128 words

Black Box Thinking: Why Most People Never Learn From Their Mistakes--But Some Do

by Matthew Syed · 3 Nov 2015 · 410pp · 114,005 words

The Participation Revolution: How to Ride the Waves of Change in a Terrifyingly Turbulent World

by Neil Gibb · 15 Feb 2018 · 217pp · 63,287 words

The End of Theory: Financial Crises, the Failure of Economics, and the Sweep of Human Interaction

by Richard Bookstaber · 1 May 2017 · 293pp · 88,490 words

Economics Rules: The Rights and Wrongs of the Dismal Science

by Dani Rodrik · 12 Oct 2015 · 226pp · 59,080 words

The Economics of Enough: How to Run the Economy as if the Future Matters

by Diane Coyle · 21 Feb 2011 · 523pp · 111,615 words

The Enigma of Capital: And the Crises of Capitalism

by David Harvey · 1 Jan 2010 · 369pp · 94,588 words

The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter

by David Sax · 8 Nov 2016 · 360pp · 101,038 words

War for Eternity: Inside Bannon's Far-Right Circle of Global Power Brokers

by Benjamin R. Teitelbaum · 14 May 2020 · 307pp · 88,745 words

The Pirate's Dilemma: How Youth Culture Is Reinventing Capitalism

by Matt Mason

The Misfit Economy: Lessons in Creativity From Pirates, Hackers, Gangsters and Other Informal Entrepreneurs

by Alexa Clay and Kyra Maya Phillips · 23 Jun 2015 · 210pp · 56,667 words

MacroWikinomics: Rebooting Business and the World

by Don Tapscott and Anthony D. Williams · 28 Sep 2010 · 552pp · 168,518 words

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

by Thomas Piketty · 10 Mar 2014 · 935pp · 267,358 words

Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science (Fully Revised and Updated)

by Charles Wheelan · 18 Apr 2010 · 386pp · 122,595 words

Financial Fiasco: How America's Infatuation With Homeownership and Easy Money Created the Economic Crisis

by Johan Norberg · 14 Sep 2009 · 246pp · 74,341 words

House of Debt: How They (And You) Caused the Great Recession, and How We Can Prevent It From Happening Again

by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi · 11 May 2014 · 249pp · 66,383 words

The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking

by Saifedean Ammous · 23 Mar 2018 · 571pp · 106,255 words

Social Capital and Civil Society

by Francis Fukuyama · 1 Mar 2000

Kings of Crypto: One Startup's Quest to Take Cryptocurrency Out of Silicon Valley and Onto Wall Street

by Jeff John Roberts · 15 Dec 2020 · 226pp · 65,516 words

The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save It

by Yascha Mounk · 15 Feb 2018 · 497pp · 123,778 words

Genentech: The Beginnings of Biotech

by Sally Smith Hughes

Automation and the Future of Work

by Aaron Benanav · 3 Nov 2020 · 175pp · 45,815 words

No Such Thing as a Free Gift: The Gates Foundation and the Price of Philanthropy

by Linsey McGoey · 14 Apr 2015 · 324pp · 93,606 words

Virtual Competition

by Ariel Ezrachi and Maurice E. Stucke · 30 Nov 2016

Common Wealth: Economics for a Crowded Planet

by Jeffrey Sachs · 1 Jan 2008 · 421pp · 125,417 words

The Future of the Professions: How Technology Will Transform the Work of Human Experts

by Richard Susskind and Daniel Susskind · 24 Aug 2015 · 742pp · 137,937 words

Security Analysis

by Benjamin Graham and David Dodd · 1 Jan 1962 · 1,042pp · 266,547 words

Everything for Everyone: The Radical Tradition That Is Shaping the Next Economy

by Nathan Schneider · 10 Sep 2018 · 326pp · 91,559 words

Plenitude: The New Economics of True Wealth

by Juliet B. Schor · 12 May 2010 · 309pp · 78,361 words

The Autonomous Revolution: Reclaiming the Future We’ve Sold to Machines

by William Davidow and Michael Malone · 18 Feb 2020 · 304pp · 80,143 words

Cryptoeconomics: Fundamental Principles of Bitcoin

by Eric Voskuil, James Chiang and Amir Taaki · 28 Feb 2020 · 365pp · 56,751 words

Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right

by Jennifer Burns · 18 Oct 2009 · 495pp · 144,101 words

The Dying Citizen: How Progressive Elites, Tribalism, and Globalization Are Destroying the Idea of America

by Victor Davis Hanson · 15 Nov 2021 · 458pp · 132,912 words

Green Swans: The Coming Boom in Regenerative Capitalism

by John Elkington · 6 Apr 2020 · 384pp · 93,754 words

How Capitalism Saved America: The Untold History of Our Country, From the Pilgrims to the Present

by Thomas J. Dilorenzo · 9 Aug 2004 · 283pp · 81,163 words

The Captured Economy: How the Powerful Enrich Themselves, Slow Down Growth, and Increase Inequality

by Brink Lindsey · 12 Oct 2017 · 288pp · 64,771 words

The Googlization of Everything:

by Siva Vaidhyanathan · 1 Jan 2010 · 281pp · 95,852 words

Fully Automated Luxury Communism

by Aaron Bastani · 10 Jun 2019 · 280pp · 74,559 words

The Scandal of Money

by George Gilder · 23 Feb 2016 · 209pp · 53,236 words

More From Less: The Surprising Story of How We Learned to Prosper Using Fewer Resources – and What Happens Next

by Andrew McAfee · 30 Sep 2019 · 372pp · 94,153 words

A World Without Email: Reimagining Work in an Age of Communication Overload

by Cal Newport · 2 Mar 2021 · 350pp · 90,898 words

The Coming Wave: Technology, Power, and the Twenty-First Century's Greatest Dilemma

by Mustafa Suleyman · 4 Sep 2023 · 444pp · 117,770 words

Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking

by Michael Bhaskar · 2 Nov 2021

The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class

by Joel Kotkin · 11 May 2020 · 393pp · 91,257 words

The Blockchain Alternative: Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy and Economic Theory

by Kariappa Bheemaiah · 26 Feb 2017 · 492pp · 118,882 words

Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty

by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson · 20 Mar 2012 · 547pp · 172,226 words

The Great Surge: The Ascent of the Developing World

by Steven Radelet · 10 Nov 2015 · 437pp · 115,594 words

Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle

by Chris Hedges · 12 Jul 2009 · 373pp · 80,248 words

The Upside of Inequality

by Edward Conard · 1 Sep 2016 · 436pp · 98,538 words

How Democracy Ends

by David Runciman · 9 May 2018 · 245pp · 72,893 words

China's Disruptors: How Alibaba, Xiaomi, Tencent, and Other Companies Are Changing the Rules of Business

by Edward Tse · 13 Jul 2015 · 233pp · 64,702 words

SuperFreakonomics

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 19 Oct 2009 · 302pp · 83,116 words

Merchants of Truth: The Business of News and the Fight for Facts

by Jill Abramson · 5 Feb 2019 · 788pp · 223,004 words

Who Stole the American Dream?

by Hedrick Smith · 10 Sep 2012 · 598pp · 172,137 words

The Global Minotaur

by Yanis Varoufakis and Paul Mason · 4 Jul 2015 · 394pp · 85,734 words

Fed Up: An Insider's Take on Why the Federal Reserve Is Bad for America

by Danielle Dimartino Booth · 14 Feb 2017 · 479pp · 113,510 words

Miracle Cure

by William Rosen · 14 Apr 2017 · 515pp · 117,501 words

The botany of desire: a plant's-eye view of the world

by Michael Pollan · 27 May 2002 · 273pp · 83,186 words

The Firm

by Duff McDonald · 1 Jun 2014 · 654pp · 120,154 words

Red Flags: Why Xi's China Is in Jeopardy

by George Magnus · 10 Sep 2018 · 371pp · 98,534 words

Tory Nation: The Dark Legacy of the World's Most Successful Political Party

by Samuel Earle · 3 May 2023 · 245pp · 88,158 words

The Last Tycoons: The Secret History of Lazard Frères & Co.

by William D. Cohan · 25 Dec 2015 · 1,009pp · 329,520 words

Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy

by Raghuram Rajan · 24 May 2010 · 358pp · 106,729 words

The Shifts and the Shocks: What We've Learned--And Have Still to Learn--From the Financial Crisis

by Martin Wolf · 24 Nov 2015 · 524pp · 143,993 words

Bean Counters: The Triumph of the Accountants and How They Broke Capitalism

by Richard Brooks · 23 Apr 2018 · 398pp · 105,917 words

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything

by David Christian · 21 May 2018 · 334pp · 100,201 words

Where Good Ideas Come from: The Natural History of Innovation

by Steven Johnson · 5 Oct 2010 · 298pp · 81,200 words

The Master Algorithm: How the Quest for the Ultimate Learning Machine Will Remake Our World

by Pedro Domingos · 21 Sep 2015 · 396pp · 117,149 words

The Great Depression: A Diary

by Benjamin Roth, James Ledbetter and Daniel B. Roth · 21 Jul 2009 · 408pp · 94,311 words

Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities

by Alain Bertaud · 9 Nov 2018 · 769pp · 169,096 words

Driverless: Intelligent Cars and the Road Ahead

by Hod Lipson and Melba Kurman · 22 Sep 2016

Race Against the Machine: How the Digital Revolution Is Accelerating Innovation, Driving Productivity, and Irreversibly Transforming Employment and the Economy

by Erik Brynjolfsson · 23 Jan 2012 · 72pp · 21,361 words

Fully Grown: Why a Stagnant Economy Is a Sign of Success

by Dietrich Vollrath · 6 Jan 2020 · 295pp · 90,821 words

Pathfinders: The Golden Age of Arabic Science

by Jim Al-Khalili · 28 Sep 2010 · 467pp · 114,570 words

Television Is the New Television: The Unexpected Triumph of Old Media in the Digital Age

by Michael Wolff · 22 Jun 2015 · 172pp · 46,104 words

The Power of Gold: The History of an Obsession

by Peter L. Bernstein · 1 Jan 2000 · 497pp · 153,755 words

Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 11 Apr 2005 · 339pp · 95,988 words

The Glass Half-Empty: Debunking the Myth of Progress in the Twenty-First Century

by Rodrigo Aguilera · 10 Mar 2020 · 356pp · 106,161 words

In Defense of Global Capitalism

by Johan Norberg · 1 Jan 2001 · 233pp · 75,712 words

The Rise and Fall of Nations: Forces of Change in the Post-Crisis World

by Ruchir Sharma · 5 Jun 2016 · 566pp · 163,322 words

Dead Companies Walking

by Scott Fearon · 10 Nov 2014 · 232pp · 71,965 words

The Rise of the Quants: Marschak, Sharpe, Black, Scholes and Merton

by Colin Read · 16 Jul 2012 · 206pp · 70,924 words

Makers

by Chris Anderson · 1 Oct 2012 · 238pp · 73,824 words

Factory Man: How One Furniture Maker Battled Offshoring, Stayed Local - and Helped Save an American Town

by Beth Macy · 14 Jul 2014 · 473pp · 140,480 words

Why Wall Street Matters

by William D. Cohan · 27 Feb 2017 · 113pp · 37,885 words

The Future of Ideas: The Fate of the Commons in a Connected World

by Lawrence Lessig · 14 Jul 2001 · 494pp · 142,285 words

The New Class Conflict

by Joel Kotkin · 31 Aug 2014 · 362pp · 83,464 words

Dark Pools: The Rise of the Machine Traders and the Rigging of the U.S. Stock Market

by Scott Patterson · 11 Jun 2012 · 356pp · 105,533 words

Overhaul: An Insider's Account of the Obama Administration's Emergency Rescue of the Auto Industry

by Steven Rattner · 19 Sep 2010 · 394pp · 124,743 words

The Chaos Machine: The Inside Story of How Social Media Rewired Our Minds and Our World

by Max Fisher · 5 Sep 2022 · 439pp · 131,081 words

Rogue State: A Guide to the World's Only Superpower

by William Blum · 31 Mar 2002

The Great Divergence: America's Growing Inequality Crisis and What We Can Do About It

by Timothy Noah · 23 Apr 2012 · 309pp · 91,581 words

The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness

by Morgan Housel · 7 Sep 2020 · 209pp · 53,175 words

Making the Future: The Unipolar Imperial Moment

by Noam Chomsky · 15 Mar 2010 · 258pp · 63,367 words

Endless Money: The Moral Hazards of Socialism

by William Baker and Addison Wiggin · 2 Nov 2009 · 444pp · 151,136 words

The Making of an Atlantic Ruling Class

by Kees Van der Pijl · 2 Jun 2014 · 572pp · 134,335 words

Lab Rats: How Silicon Valley Made Work Miserable for the Rest of Us

by Dan Lyons · 22 Oct 2018 · 252pp · 78,780 words

The Cost of Inequality: Why Economic Equality Is Essential for Recovery

by Stewart Lansley · 19 Jan 2012 · 223pp · 10,010 words

The AI Economy: Work, Wealth and Welfare in the Robot Age

by Roger Bootle · 4 Sep 2019 · 374pp · 111,284 words

The Penguin and the Leviathan: How Cooperation Triumphs Over Self-Interest

by Yochai Benkler · 8 Aug 2011 · 187pp · 62,861 words

The Weightless World: Strategies for Managing the Digital Economy

by Diane Coyle · 29 Oct 1998 · 49,604 words

The Wisdom of Crowds

by James Surowiecki · 1 Jan 2004 · 326pp · 106,053 words

With Liberty and Dividends for All: How to Save Our Middle Class When Jobs Don't Pay Enough

by Peter Barnes · 31 Jul 2014 · 151pp · 38,153 words

The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970

by John Darwin · 23 Sep 2009

The Streets Were Paved With Gold

by Ken Auletta · 14 Jul 1980 · 407pp · 135,242 words

Future Tense: Jews, Judaism, and Israel in the Twenty-First Century

by Jonathan Sacks · 19 Apr 2010 · 305pp · 97,214 words

How to Own the World: A Plain English Guide to Thinking Globally and Investing Wisely

by Andrew Craig · 6 Sep 2015 · 305pp · 98,072 words

The True and Only Heaven: Progress and Its Critics

by Christopher Lasch · 16 Sep 1991 · 669pp · 226,737 words

America in the World: A History of U.S. Diplomacy and Foreign Policy

by Robert B. Zoellick · 3 Aug 2020

The Joys of Compounding: The Passionate Pursuit of Lifelong Learning, Revised and Updated

by Gautam Baid · 1 Jun 2020 · 1,239pp · 163,625 words

The Social Animal: The Hidden Sources of Love, Character, and Achievement

by David Brooks · 8 Mar 2011 · 487pp · 151,810 words

Eat People: And Other Unapologetic Rules for Game-Changing Entrepreneurs

by Andy Kessler · 1 Feb 2011 · 272pp · 64,626 words

Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War

by Robert Coram · 21 Nov 2002 · 548pp · 174,644 words

The Tyranny of Nostalgia: Half a Century of British Economic Decline

by Russell Jones · 15 Jan 2023 · 463pp · 140,499 words

Free Speech And Why It Matters

by Andrew Doyle · 24 Feb 2021 · 137pp · 35,041 words

Radicals Chasing Utopia: Inside the Rogue Movements Trying to Change the World

by Jamie Bartlett · 12 Jun 2017 · 390pp · 109,870 words

Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy

by Jonathan Taplin · 17 Apr 2017 · 222pp · 70,132 words

Company: A Short History of a Revolutionary Idea

by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge · 4 Mar 2003 · 196pp · 57,974 words

Superminds: The Surprising Power of People and Computers Thinking Together

by Thomas W. Malone · 14 May 2018 · 344pp · 104,077 words