The scramble for Africa, 1876-1912

by

Thomas Pakenham

Published 19 Nov 1991

At the same time Wolseley was struggling up the cataracts of the Nile towards Khartoum, to save Gordon – and the nation’s honour – from defilement by the Mahdi. CHAPTER 13 Too Late? The Sudan 26 September 1884-Z6 January 1883 ‘In the name of God the merciful and compassionate … Those who believed in us as the Mahdi, and surrendered, have been delivered, and those who did not were destroyed…’ Muhammad Ahmad, the Mahdi, to Gordon Pasha of Khartoum, 22 October 1884 ‘From the top of the Serail’, wrote Gordon on 26 September 1884, jotting it down in his journal with the innocence and vulnerability of a small boy writing home to his mother, ‘one commands views all round for miles.’

…

Was he supposed to charm the garrisons out of the Sudan by magic, the baraka of the great pasha, whose feet the Sudanese kissed at Khartoum, crying ‘Sultan’ and ‘Father’. Gordon had strange ideas, but he did not over-estimate the power of his own magic. In those three weeks before the gates of the gaol clanged shut, he had sent increasingly desperate appeals down the line to Baring. To evacuate Khartoum and the other garrisons, both Baring and Gladstone agreed, could not mean a simple policy of ‘skidaddle’ or ‘rat’. For practical as well as moral reasons, they simply could not run away, with the devil to the hindmost. Gordon must hand over the reins to some nominated successor.

…

Second, the great emirs were quarrelling among themselves and seemed to have lost their appetite for battle. No one was anxious to assault Khartoum, although the place was known to be full of loot. Some disaffected sheikhs would even have liked to join Gordon, if they could have done so without abandoning their wives and families. This was the reassurance that Slatin yearned to take to Gordon. With energy and perseverance Khartoum could hold out for months. Knowing the Mahdi’s intentions, Slatin would surely be a godsend to the defence. And perhaps he also envisaged an adventurous trip down-river in one of Gordon’s steamers, to link up with the relief expedition, known to be marching south.

Empire: What Ruling the World Did to the British

by

Jeremy Paxman

Published 6 Oct 2011

The Pall Mall Gazette bellowed that Gordon must be dispatched to Khartoum and soon the entire herd was mooing. In no time, there were crowds in the streets chanting ‘Gordon Must Go!’ and the government caved in. But he was emphatically not being sent there to bag another colony: Gordon was to go to Khartoum, evacuate all those who wished to leave, and then report back. The Foreign Secretary himself came to Charing Cross station to see him off at the start of his journey, although Gladstone’s secretary was wise enough to spot the risks of sending someone like Gordon to a place where he would be beyond any effective control.

…

Characteristically, this was followed, two weeks later, by a message which said the precise opposite: ‘Khartoum is all right. Could hold out for years. CG Gordon. 29.12.84’. This was nonsense. As even the Mahdi knew from the deserters who crossed to his lines, by now almost every living thing that could be eaten – even rats – had been devoured. The waters of the Nile, which had provided a natural defence, were falling all the time. At around three in the morning of 26 January 1885 Khartoum was woken by the sound of tens of thousands of jihadists swarming into the town. It was all over very quickly and very savagely. Gordon’s contempt for his Egyptian troops had been justified, and in their emaciated state they were unable to put up much of a fight anyway.

…

By the turn of the millennium, there was hardly an imperial hero who had not had a few buckets of mud thrown at him. The great explorers of Africa, such as Richard Burton, were racists. Captain Scott had condemned his men to icy deaths in Antarctica by vainglorious bungling. The sexuality of the hero of Khartoum, General Gordon, was suspect. Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Boy Scouts, was cracked. The tone of movies had changed, too. David Lean’s portrayal of a troubled egotist in Lawrence of Arabia (1962) was much less about grand imperial designs than about a romantic, misunderstood loner. The new heroes were the men and women who fought against the British brutes – the Mahatma in Gandhi (1982), the medieval Scottish rebel William Wallace in Braveheart (1995) or the modern Irish revolutionary in Michael Collins (1996).

Ghosts of Empire: Britain's Legacies in the Modern World

by

Kwasi Kwarteng

Published 14 Aug 2011

In keeping with Sudanese custom, the heads of Hicks and his leading officers were presented to the Mahdi and his followers.22 It was then decided by Gladstone’s government in London to evacuate the Egyptian garrison in Khartoum, an operation that Gordon was dispatched to oversee; he arrived on 18 February 1884. Charles Gordon is one of those historical figures of whom many people are dimly aware. This is partly because the role of Gordon was successfully played by Charlton Heston in the 1966 film Khartoum, in which Gordon meets his end on the steps of the palace at Khartoum, surrounded by spear-wielding dervishes. Despite being the subject of a Hollywood blockbuster, Gordon’s life was even more spectacular than any work of creative fiction could depict.

…

Belatedly, a Gordon Relief Expedition was dispatched in August 1884, under Sir Garnet Wolseley, another powerful figure of this militaristic age. In Khartoum, Gordon was having sleepless nights and was only too aware that his ability to withstand the siege was limited. The denouement came in January 1885, when, at about 3.30 a.m. on Monday the 26th, the Mahdi’s troops made a ‘determined attack’ on the south side of the town. Khartoum fell, according to Kitchener’s account (though he was not there to witness it), because the garrison were too exhausted by their sufferings to put up a proper resistance. Once the rebels had entered the town, there was a general massacre, and the exact fate of General Gordon remains unclear. He was killed, certainly, but differing accounts of his death have been related to this day.

…

As Lord Randolph Churchill told the House of Commons on 16 March 1884, the General was in a dangerous situation, being ‘surrounded by hostile tribes and cut off from communications with Cairo and London’.28 The siege continued, with conditions in Khartoum becoming more and more desperate. The garrison suffered from ‘want of food’, and by December ‘all the donkeys, dogs, cats, rats etc. had been eaten’.29 The slow response from the Gladstone government to the crisis in which Gordon found himself is well known. The Prime Minister was as stubborn as Gordon and seems to have taken a perverse pride in not heeding the popular demand that he immediately send a force to save Gordon.

Heaven's Command (Pax Britannica)

by

Jan Morris

Published 22 Dec 2010

He toyed with the idea of negotiating peace with the Mahdi, and suggested that as an agent of authority the Government should send to Khartoum a notorious former slave-trader, Zubeir Pasha, who had once been Gordon’s bitter enemy, but towards whom he had lately developed, he said, ‘a mystical feeling’. The very name of Zubeir was anathema to the English evangelicals, and Gordon’s quixotic demand for his services was the British public’s first intimation that queer things were likely to happen in Khartoum—his employment, said the Anti-Slavery Society, would be ‘a degradation for England, a scandal to Europe’. Next Gordon began to hint that perhaps after all the Sudan should be reconquered by British arms, if only to guarantee the security of Egypt.

…

A message from the Mahdi put paid to any hope of negotiated settlement: if Gordon surrendered he would save himself and his supporters, ‘otherwise you shall perish with them and your sins and theirs shall be on your head’. Now the tribes to the north of Khartoum, hitherto quiescent, rose in support of the Mahdi. The rebels invested Khartoum itself, and the telegraph line to Cairo was cut. Gordon’s communications with Baring were reduced to messages on scraps of paper, sent out by runner, and Khartoum became a city under siege. Now at least Gordon was explicit. When the British Government got a message through asking why he seemed to be making no attempt to leave Khartoum with the garrison, as instructed, his reply was tart. ‘You ask me to state cause and intention in staying in Khartoum knowing Government means to abandon Sudan, and in answer I say, I stay at Khartoum because Arabs have shut us up and will not let us out.’

…

He could still fight his way out of Khartoum, but he had never tried to do so, and gradually, as the summer of 1884 dragged by, it became dimly apparent to Mr Gladstone’s Government that Gordon was blackmailing them. He had no intention either of withdrawing the garrisons, or even escaping himself: he wanted the British to reconquer the Sudan by force of arms, and he was staking his own person as hostage. If the British public baulked at Zubeir, despised the Egyptians, was not very interested in the future of the Sudan and had little idea where Khartoum was, it would certainly not be prepared to let ‘Chinese’ Gordon, the perfect Christian gentleman, die abandoned and friendless in the heart of Africa.

Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World

by

Niall Ferguson

Published 1 Jan 2002

In 1883 his forces even had the temerity to wipe out, to the last man, a 10,000-strong Egyptian army led by Colonel William Hicks, a retired British officer. After an indignant press campaign led by W. T. Stead, it was decided to send General Charles George Gordon, who had spent six years in Khartoum as the Egyptian Khedive’s Governor of ‘Equatoria’ during the 1870s. Although a decorated veteran of the Crimean War and the commander of the Chinese army that had crushed the Taiping rebellion in 1863–4, Gordon was always regarded by the British political establishment as half mad, and with some reason.* Ascetic to the point of being masochistic, devout to the point of being fanatical, Gordon saw himself as God’s instrument, as he explained to his beloved sister: To each is allotted a distinct work, to each a destined goal; to some the seat at the right-hand or left of the Saviour … It is difficult for the flesh to accept ‘Ye are dead, ye have naught to do with the world.’

…

Charged with evacuating the Egyptian troops stationed in Khartoum, he set off alone, resolved to do the very opposite and hold the city. He arrived on 18 February 1884, by now determined to ‘smash up the Mahdi’, only to be surrounded, besieged and – nearly a year after his arrival – hacked to pieces. While marooned in Khartoum, Gordon had confided to his diary his growing suspicion that the government in London had left him in the lurch. He imagined the Foreign Secretary, Lord Granville, complaining as the siege dragged on: Why, HE said distinctly he could only hold out six months, and that was in March (counts the months).

…

Why on earth does he not guard his roads better? What IS to be done? … What that Mahdi is about I cannot make out. Why does he not put all his guns on the river and stop the route? Eh what? ‘We will have to go to Khartoum!’ Why, it will cost millions, what a wretched business! Even more reviled was the British Agent and Consul-General in Egypt, Sir Evelyn Baring, who had opposed Gordon’s mission from the very outset. There was a grain of realism in Gordon’s paranoia. Gladstone, still uneasy at having ordered the occupation of Egypt, had no intention of being drawn into the occupation of Sudan. He repeatedly evaded suggestions that Gordon should be rescued and authorized the despatch of Sir Garnet Wolseley’s relief expedition only after months of prevarication.

Posh Boys: How English Public Schools Ruin Britain

by

Robert Verkaik

Published 14 Apr 2018

Gordon met his grisly end after the siege of Khartoum where he had been sent to evacuate the British garrison. It was here that his refusal to obey an order cost him his life. Instead of relieving the garrison he decided to stay on to fight the Islamist army led by Muhammad Ahmad. After holding out for months in hope of a relief column sent from London, Khartoum’s defences fell. Gordon was killed and his severed head paraded around the city. Ahmad proclaimed himself ruler of Sudan, and established a religious state, the Mahdiyah, which was governed by a harsh enforcement of Sharia law. Out of consideration for his Turkish, Egyptian and Sudanese troops, Gordon had refrained in public from describing his battle with the Mahdi as a religious war, but his diary showed he viewed himself as a Christian champion fighting just as much for God as for Queen and country.

…

In 1874 Major Edmund Musgrave Barttelot followed in his father’s footsteps and entered Rugby School. He then went to Sandhurst, again behind his father, where he was enrolled as an officer in the 7th Royal Fusiliers. After the fall of Gordon at Khartoum the emboldened armies of Muhammad Ahmad, the self-proclaimed Muslim Mahdi, cut off Equatoria and threatened Cairo, key to Britain’s influence in the region. In 1885, Emin Pasha, the governor whom Gordon had personally appointed to office, withdrew further south, to Wadelai near Lake Albert, but was in imminent danger of capture by the Mahdi’s superior forces. The following year, Britain assembled the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, led by Henry Morton Stanley (of ‘Dr Livingstone I presume’ fame) and set about the rescue of Pasha.

Heroic Failure: Brexit and the Politics of Pain

by

Fintan O'Toole

Published 22 Jan 2018

The Politics of Pain

by

Fintan O'Toole

Published 2 Oct 2019

I Never Knew That About London

by

Christopher Winn

Published 3 Oct 2007

Baghdad Without a Map and Other Misadventures in Arabia

by

Tony Horwitz

Published 1 Jan 1991

The Sudanese eventually revolted, under a messianic figure known as the Mahdi, and laid siege to a small British force under the command of Charles George Gordon. “It is a useless place and we could not govern it,” Gordon wrote from Khartoum in 1884. “The Sudan could be made to pay its expenses, but it would need a dictator, and I would not take the post if offered to me.” It wasn't. Instead, Gordon's severed head was offered to the Mahdi, then stuck atop a pole on the banks of the Nile. Thirteen years later, Sudanese dervishes charged out of Khartoum, clad in chain mail, to meet British Catling guns in the battle of Omdurman.

…

A war correspondent of the day wasn't so impressed: “It was not a battle but an execution.” The British hurled the Mahdi's head into the Nile and settled in for sixty more years of dominion. Now, after three decades of independence, Khartoum was a sprawling junkyard of British imperialism. The graves of eighteen-year-old Cameron Highlanders and 1st Grenadiers felled by Dervish spears—or more often by malaria—lay in a weed-infested cemetery at the edge of town. George Gordon's own gunboat rotted on the city's riverbank, unmarked and unremembered, near where the slate-gray waters of the Blue Nile meet the dull dishwater brown of the White Nile. Five miles upstream, naked boys fished from the half-sunk hulls of rusted British paddle-wheelers.

…

Five miles upstream, naked boys fished from the half-sunk hulls of rusted British paddle-wheelers. Khartoum's broad avenues had been laid out at the turn of the century in the shape of a Union Jack, with the streets forming three superimposed crosses. Now the city plan was a tangled, potholed smudge. Trapped in the perpetually stalled traffic, it was impossible to avoid feeling, as George Gordon had, that the only important question in Khartoum was how to “get out of it in honor and in the cheapest way. . . it is simply a question of getting out of it with decency.” At Sudan's Natural History Museum, the Living Collection was mostly dead.

The Gun

by

C. J. Chivers

Published 12 Oct 2010

As the new weapon was receiving its inaugural praise in Maxim’s shop, England was consumed by a long-running difficulty in eastern Africa. The Egyptian province of Sudan had been swept by Islamic rebellion in 1881, and in 1883 Britain had decided to evacuate its citizens and the Egyptian military presence from the capital, Khartoum. A popular officer and former administrator of the province, Major General Charles Gordon, was dispatched to organize the city’s defense and coordinate the exit. He arrived to discover the situation desperate. By midspring 1884 the Islamic forces controlled the approaches to the city, trapping the Egyptian contingent and General Gordon in a siege.

…

But it lasted only fourteen turns—seventy bullets against thousands of attacking men. A machine gun good only for a moment’s work was not much good at all. The Desert Column fought another engagement en route but Colonel Stewart was wounded and he ceded command. His unit arrived at Khartoum one day late. The city had fallen. General Gordon had been beheaded. His killers displayed their grisly prize by wedging it in the branches of a tree. Colonel Stewart later succumbed to his wounds. London was crestfallen. What was bad for Britain was good for Maxim. Episodes when manual machine guns failed could only aid his cause.

…

A large expeditionary force, more than eight thousand British soldiers accompanied by nearly eighteen thousand Egyptian and African troops, was placed under the command of General Herbert Kitchener. It massed in Egypt and prepared for the arduous trek and river movement up the Nile to destroy the forces of the Khalifa, the Sudanese leader, and reclaim Khartoum. The campaign would serve a second purpose: to avenge the beheading of General Gordon in 1885. A feat of logistics and administration made the final clash possible. Kitchener built a railroad through the desert to keep his soldiers well supplied. An escort of gunboats accompanied them as they traveled upriver. The Maxims were brought overland wrapped in silk, to prevent them from collecting sand and grit.64 By late summer 1898, with the British columns nearing the capital at last, the Khalifa prepared to annihilate them outside Omdurman, on the Nile’s western bank and to Khartoum’s north.

This Sceptred Isle

by

Christopher Lee

Published 19 Jan 2012

He accordingly asked for reinforcements and put forward plans for counter-attack. He was resolved to remain in Khartoum until his self-imposed mission was accomplished. By May of that year, 1884, Gordon was trapped in Khartoum. Public opinion demanded that he should be rescued. The government, with other matters on its mind and obviously dithering, did nothing until it was too late. At last, Gordon’s dilemma became a Cabinet crisis. Gladstone gave in and General Wolseley was ordered to Cairo. He did not arrive in time. When reinforcements and rescue squadrons arrived in Khartoum on 28 October, Gordon was dead and soon would be a martyr. That was in 1885.

Where We Are: The State of Britain Now

by

Roger Scruton

Published 16 Nov 2017

Brit-Myth: Who Do the British Think They Are?

by

Chris Rojek

Published 15 Feb 2008

Shadows of Empire: The Anglosphere in British Politics

by

Michael Kenny

and

Nick Pearce

Published 5 Jun 2018

The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary

by

Simon Winchester

Published 1 Jan 2003

The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia

by

Peter Hopkirk

Published 2 Jan 1991

After Tamerlane: The Global History of Empire Since 1405

by

John Darwin

Published 5 Feb 2008

Europeans reserved a particular loathing (and a special fear) for this Muslim ‘fanaticism’, symptomatic, they thought, of Islam’s arrested development. Its most famous victory in the late nineteenth century was the Mahdist revolt against Egypt’s colonial rule in the Nilotic Sudan, which culminated in 1885 with the capture of Khartoum and the death of General Gordon, the governor-general sent by the Egyptian government (under heavy British pressure) to stage an orderly retreat.95 When the British re-entered the city thirteen years later, after defeating the Mahdist army at Omdurman, Kitchener ordered the bones of the first Mahdi ruler (Muhammad Ahmad, 1844–85) to be thrown in the Nile.

Time Lord: Sir Sandford Fleming and the Creation of Standard Time

by

Clark Blaise

Published 27 Oct 2000

Israel & the Palestinian Territories Travel Guide

by

Lonely Planet

While enjoying little support for their claims, the trustees have provided a walled and attractively landscaped space that is more conducive to contemplation than the alternative site said to be that of the crucifixion, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Biblical significance was first attached to this location by General Charles Gordon (of Khartoum fame) in 1883. Gordon refused to believe that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre could occupy the site of Calvary, and on identifying a skull-shaped hill just north of Damascus Gate he began excavations. The ancient tombs he discovered under the mound further strengthened his conviction that this was the true site.

Diamonds, Gold, and War: The British, the Boers, and the Making of South Africa

by

Martin Meredith

Published 1 Jan 2007

Desperate to resolve the Basutoland quagmire, the Cape government recruited the services of General Charles Gordon, one of the foremost heroes of the Victorian age. A decorated veteran of the Crimean War and commander of the Chinese army that had crushed the Taiping rebellion in 1863-4, Gordon had spent six years in Khartoum during the 1870s serving as governor of Equatoria province in southern Sudan. Gordon saw himself as God’s instrument and believed he possessed mesmeric power over primitive people. The British political establishment regarded him as half mad - ‘inspired and mad’, according to Gladstone. Despite his formidable record, on his return to London he was packed off to Mauritius, in his words to supervise ‘the barracks and drains’ there.

…

Gordon soon fell out with the Cape government and returned to England. The Cape government itself, weakened and impoverished by the Gun War, soon tired of responsibility for Basutoland and passed it back to Britain. Gordon, however, did not forget Rhodes. When he was given a new assignment in Khartoum - this time to evacuate Egyptian troops threatened by the advance of the Mahdi’s Dervish army - Gordon asked Rhodes to join him. Once again, Rhodes declined. When Rhodes heard the news of Gordon’s death in 1885 on the steps of the governor’s residence in Khartoum, dreaming of posthumous glory for himself he remarked: ‘I am sorry I was not with him.’

Engines of War: How Wars Were Won & Lost on the Railways

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 1 Nov 2011

The railway network of the Confederate and border states at the outset of the American Civil War, 1861. The railway network of eastern France at the time of the Franco-Prussian War, 1870-1. The detail shows the area around Metz which was a key battleground. The Sudan Military Railway built to allow the British to retake Khartoum thirteen years after the capture of the town and the death of General Gordon in 1885. The railways in southern Africa at the start of the Boer War in 1899. The key railways over which the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5 was fought. The western front in the First World War showing the main railway lines with detail of the Somme.

…

However, in 1884 a start was made on a line at Wadi Haifa, the Nile port on the Egyptian-Sudanese border, by British and Egyptian soldiers and labourers, overseen by a company (about 250 men) of Royal Engineers, but work stopped when the 700 local labourers deserted. The idea was abandoned shortly after, with just fifty miles completed, when news reached Egypt of the fall of Khartoum and the death of General Gordon at the hands of the Mahdi rebels in January 1885. Work also stopped on a separate line which was being built simultaneously to link the Nile with the Red Sea at the port of Suakin. Again the Royal Engineers had been involved but attacks by Dervishes on the mostly Indian labour force led to the abandonment of the project after just twenty miles had been laid, despite the construction of fortified posts at regular intervals along it and the introduction of night patrols using a bulletproof train armed with a 20-pounder gun.

…

With the completion of the railway, ‘though the battle was not yet fought, the victory was won… It remained only to pluck the fruit in the most convenient hour, with the least trouble and at the smallest cost.’15 Indeed, new gunboats were ordered and broken up into sections that could be accommodated on the railway, rebuilt and relaunched on the navigable section of the Nile. Having overcome resistance and conquered the intermediate towns, the final battle took place at Omdurman, fifteen miles from Khartoum, where Churchill was proved correct: the might of the well-supplied British Army easily overcame the enemy despite being hugely outnumbered. The British lost just fifty men, compared with about 10,000 enemy casualties, and Gordon was richly avenged. It was, of course, not only the railway but the whole logistical operation which ensured victory. Churchill described what it took for one box of biscuits to reach the front line from Cairo, involving a dozen changes of mode, including camel as well as boat and train, to cover some 1,150 miles.

The Prince of the Marshes: And Other Occupational Hazards of a Year in Iraq

by

Rory Stewart

Published 1 Jan 2005

From the Ruins of Empire: The Intellectuals Who Remade Asia

by

Pankaj Mishra

Published 3 Sep 2012

Greater: Britain After the Storm

by

Penny Mordaunt

and

Chris Lewis

Published 19 May 2021

Nomads: The Wanderers Who Shaped Our World

by

Anthony Sattin

Published 25 May 2022

Imperial Legacies

by

Jeremy Black;

Published 14 Jul 2019

To the Ends of the Earth: Scotland's Global Diaspora, 1750-2010

by

T M Devine

Published 25 Aug 2011

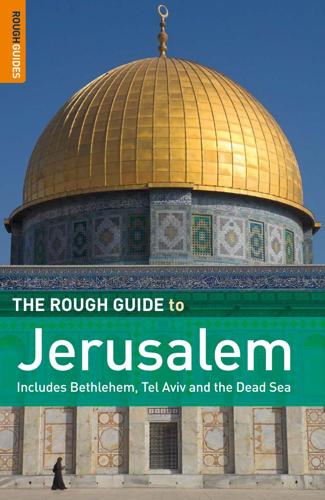

The Rough Guide to Jerusalem

by

Daniel Jacobs

Published 10 Jan 2000

| The downtown area and Nablus Road St Étienne’s Church E as t J e rus al e m Two hundred metres up Nablus Road from the Damascus Gate, along a short alleyway to the east, is the Garden Tomb (Mon–Sat 9am–noon & 2–5.30pm; free; T 02/627 2745, W www.gardentomb.com), regarded by some Protestants as the true site of Christ’s burial. It was first noted by Charles George Gordon, the British general and sometime governor of Sudan (“Gordon of Khartoum”), on a visit to Jerusalem in 1883. Picturing the city as a skeleton, with the Dome of the Rock as the pelvis and Solomon’s Quarries as the ribs, Gordon suggested that the hill to the north of the Damascus Gate was the Golgotha or “place of the skull” referred to in the Gospels, and it was therefore also known as Gordon’s Calvary. The two “eye sockets” of Jeremiah’s Grotto (see opposite) also make the hill look strikingly like a skull.

The Siege of Mecca: The 1979 Uprising at Islam's Holiest Shrine

by

Yaroslav Trofimov

Published 9 Sep 2008

Shiite Muslims believe the Mahdi had already emerged in the ninth century and then vanished to return at the end of the world. Several claimants to the status of Mahdi appeared among the Sunnis in the meantime, including the Sudanese rebel Mohammed Ahmed Sayid Abdullah, whose followers routed the mighty British army and captured Khartoum in 1885, killing General Charles Gordon. Juhayman dedicated to the Mahdi’s imminent arrival one of the seven epistles. Before the promised Mahdi emerges, Juhayman noted in the text, “great discord will occur, and Muslims will be drifting away from the religion”—a condition that, to him, was already painfully obvious.

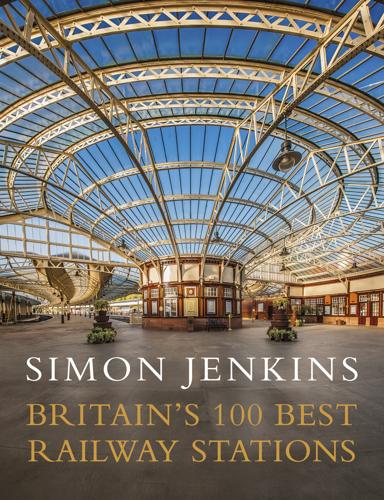

Britain's 100 Best Railway Stations

by

Simon Jenkins

Published 28 Jul 2017

Instead of the intended sixteen platforms there are now just six, from which birds can be heard singing from adjacent gardens. The only note of swagger is the GCR logos that festoon every wall and railing. Marylebone’s discretion meant that it was much used for filming. In the Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night (1964), it stood in for Liverpool Lime Street. In Khartoum (1966), troops left to relieve General Gordon on a train bound for Denham. Odder was the hotel built to accompany Watkin’s modest terminus. The company could not afford one at all and turned to the furnishing magnate Sir Blundell Maple as promoter. His architect was the larger-than-life Colonel Sir Robert Edis, also busy at the Great Eastern (see here).

The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970

by

John Darwin

Published 23 Sep 2009

Empireland: How Imperialism Has Shaped Modern Britain

by

Sathnam Sanghera

Published 28 Jan 2021

Then we have the example of General Gordon, the former Governor-General of the Sudan, who was present at the burning of the Imperial Summer Palace in China, and died in Khartoum in 1885 after being sent back to the country to deal with a Mahdi revolt. A hero to the British people – after he had commanded the army that put down the Taiping Rebellion during the Second Opium War – Gordon was ordered to evacuate the city of Khartoum immediately, before it was overrun by the Mahdist army. Instead, he resolved to stay, possibly in an attempt to rescue every civilian, but with the expectation that the British would send reinforcements. The relief came two days too late and by then Gordon was already dead. The British retreated from the Sudan and the whole exercise proved to be a massive failure.

The English

by

Jeremy Paxman

Published 29 Jan 2013

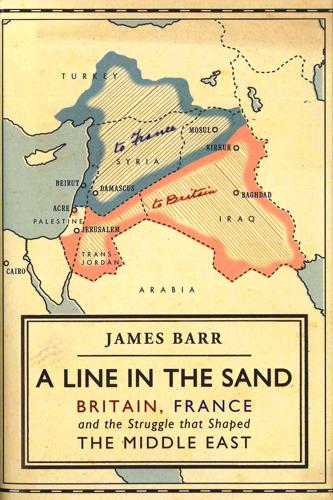

A Line in the Sand: Britain, France and the Struggle for the Mastery of the Middle East

by

James Barr

Published 15 Feb 2011

Culture and Imperialism

by

Edward W. Said

Published 29 May 1994

The Pursuit of Power: Europe, 1815-1914

by

Richard J. Evans

Published 31 Aug 2016

The British were effectively drawn in to occupying Egypt on their own, and stayed not least in order to guard it against a jihad launched by the sheikh Muhammad Ahmad (1844–85), who took the title of ‘Mahdi’ or Redeemer, in neighbouring Sudan. This was the uprising that led in 1885 to the famous incident of the death of General Gordon, whom Isma’il Pasha had appointed Governor of the Sudan, at the Sudanese capital Khartoum. The British expeditionary force sent to rescue Gordon came too late; after his death it withdrew, and Sudan was left alone for the time being. Egypt did not become a British colony, but remained under the control of the Debt Commission. This now became the site of Anglo-French rivalry, encouraged by the Germans, who also sat on the commission.

Blood, Iron, and Gold: How the Railways Transformed the World

by

Christian Wolmar

Published 1 Mar 2010

Despite the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, which took away much of its revenue, the railway was extended to reached Assiut on the banks of the Nile by 1874 and Luxor 340 miles south of Cairo in 1898. Sudan, south of Egypt, had been abandoned in 1885 by the British after the siege of Khartoum which ended with the massacre of Gordon and his army by rebels, led by Mahdi Muhammad Ahmad, a religious leader opposed to Western control of Egypt. A decade later, Kitchener obtained permission from the British government to build the Sudan Military Railway through to Khartoum in order to reconquer the country and defeat the Mahdi rebels.

Gnomon

by

Nick Harkaway

Published 18 Oct 2017

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

by

Joan Didion

Published 1 Jan 1968

The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance

by

Henry Petroski

Published 2 Jan 1990

The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists

by

Robert Tressell

Published 31 Dec 1913

Egypt Travel Guide

by

Lonely Planet

Egypt Travel Guide

by

Lonely Planet

Egypt

by

Matthew Firestone

Published 13 Oct 2010

The London Compendium

by

Ed Glinert

Published 30 Jun 2004

The Black Nile: One Man's Amazing Journey Through Peace and War on the World's Longest River

by

Dan Morrison

Published 11 Aug 2010

After winning an escalating series of battles against the occupiers, in 1883 the Mahdi’s forces smote an incompetent British-led force of eight thousand Egyptian soldiers (some of them outfitted in heavy chain mail for the desert engagement). In 1885, they hit the jackpot and took Khartoum after a 317-day siege, killing the famed governor-general Charles Gordon, a British war hero and darling of the antislavery movement. Sudan became a Talibanlike state of summary judgment, famine and perpetual war. The flow of slaves from Sudan to Egypt, Turkey and the Arabian Peninsula resumed from a trickle to a flood. And Britain readied its revenge.

A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East

by

David Fromkin

Published 2 Jan 1989

Fearsome Particles

by

Trevor Cole

Published 2 Jan 2006

The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885

by

Pierre Berton

Published 1 Jan 1971

The adoption of the new time system in that first month of 1885 was a relatively minor event as far as newspaper readers were concerned. The world was in a ferment and, for the first time, the new nation had a personal stake in the outcome. Up the steamy cataracts of the Nile a flotilla of boats manned by Canadian voyageurs was slowly making its way on a vain mission to relieve Khartoum and rescue that flawed hero, General Charles Gordon, from the clutches of the Mahdi. This was the nation’s first expeditionary force and it had its origin in the same series of events that helped to launch the idea of a Pacific railway. Its commander was General Garnet Wolseley, who had taken Canadian and British troops across the portages of the Shield to relieve Fort Garry during the Riel uprising of 1869–70.

Unfinished Empire: The Global Expansion of Britain

by

John Darwin

Published 12 Feb 2013

The River at the Centre of the World

by

Simon Winchester

Published 1 Jan 1996

Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory, and the Conquest of Everest

by

Wade Davis

Published 27 Sep 2011

China into Africa: trade, aid, and influence

by

Robert I. Rotberg

Published 15 Nov 2008

Some argue that this position is an outgrowth of China’s fierce protection of its own rights and sovereignty, and its resentment of foreign interference in its domestic affairs. The involvement of Western traders, the Boxer Rebellion, and the general humiliation at the hands of Western interests in the nineteenth century have not been forgotten. In a revealing moment, Zhou Enlai told an audience in Khartoum in 1964 that China was grateful to the Sudanese for killing British General Charles Gordon in 1885. Evidently, Gordon had supervised the burning of the old Beijing Summer Palace in 1860, twenty-five years earlier. More than a century later, Beijing still considered Gordon’s activities an insult to the Chinese people.8 This resentment of outside interference has colored Sino-Russian relations since Nikita Khrushchev and Mao Zedong split in the mid-1950s, and it certainly characterizes China’s response to U.S. criticism of alleged human rights violations.

Jerusalem: The Biography

by

Simon Sebag-Montefiore

Published 27 Jan 2011

Shake Hands With the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda

by

Romeo Dallaire

and

Brent Beardsley

Published 9 Aug 2004

I sat down beside him to try to ease his embarrassment and reassure him he was all right and then sent him to change his pants while I replaced him at his post. The city was largely quiet. Sitting there in the dark, I studied the fence surrounding the compound and visualized hundreds of extremists swarming our headquarters, intent on getting to Faustin. The image made me think of the movie Khartoum, when swarms of dervishes rush the stairs to kill General Gordon and his men. Would my soldiers fight under a UN flag to defend Faustin? For the first time that day I felt truly hopeless and trapped, a feeling I determinedly shunted to one side when the young Ghanaian came back to relieve me. Sometime after midnight, an RPF officer and a platoon of soldiers arrived at our main gate, and Brent was summoned by the Ghanaian guards to talk to the officer, who was cockily wearing a UN blue helmet like a war trophy and demanding to see Faustin.

The River of Lost Footsteps

by

Thant Myint-U

Published 14 Apr 2006

In Bombay in the last few weeks of the year, seventy or so Indian lawyers, educators, and journalists came together to set up the Indian National Congress, the organization that one day, under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi and Pandit Nehru, would help take Burma, as well as India, on the path to independence. For England, 1885 started off quite badly. For months, the slow-motion fall of Khartoum had been reported graphically over the tabloids, and the death of General Charles “Chinese” Gordon in February had set off a wave of anger, much of it directed at the Liberal government of the country’s long-standing prime minister, William Gladstone. General Gordon had won renown in the 1860s in China, where he led the multinational “Ever-Victorious Army” on behalf of the emperor against the Taiping rebels.

The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East

by

Robert Fisk

Published 2 Jan 2005

Certainly it boasted another potential Islamic “monster” for the West. Hassan Abdullah Turabi, the enemy of Western “tyranny,” a “devil” according to the Egyptian newspapers, was supposedly the Ayatollah of Khartoum, the scholarly leader of the National Islamic Front which provided the nervous system for General Omar Bashir’s military government. Indeed, Bashir’s palace boasted the very staircase upon which General Charles Gordon had been cut down in 1885 by followers of Mohamed Ahmed ibn Abdullah, the Mahdi, who like bin Laden also demanded a return to Islamic “purity.” But when I went to talk to Turabi in his old English office, he sat birdlike on a chair, perched partly on his left leg that was hooked beneath him, his white robe adorned with a tiny patterned scarf, hands fluttering in front of a black beard that was now flecked with white.

…

In need, surely, of a leader who did not speak in this language of surrender; in need of a warrior leader, someone who had proved he could defeat a superpower. Was this not what the Mahdi had believed himself to be? Did the Mahdi not ask his fighters on the eve of their attack on Khartoum whether they would advance against General Gordon even if two-thirds of them should perish? But like almost every other Arab state, Sudan re-created itself in a looking glass for the benefit of its own leaders. Khartoum was the “capital city of virtues,” or so the large street banners claimed it to be that December. Sometimes the word “virtues” was substituted with the word “values,” which was not quite the same thing.

Andrew Carnegie

by

David Nasaw

Published 15 Nov 2007

Frommer's Israel

by

Robert Ullian

Published 31 Mar 1998

England: Seven Myths That Changed a Country – and How to Set Them Straight

by

Tom Baldwin

and

Marc Stears

Published 24 Apr 2024

The Rough Guide to Egypt (Rough Guide to...)

by

Dan Richardson

and

Daniel Jacobs

Published 1 Feb 2013

Soldier, Sailor, Frogman, Spy, Airman, Gangster, Kill or Die: How the Allies Won on D-Day

by

Giles Milton

Published 25 Jan 2019

Lord Lovat’s childhood had been built upon such tales: Major Baden-Powell’s irregular forces smashing the siege of Mafeking; Sir Alfred Gaselee’s heroic relief of the Peking legations; Sir Garnet Wolseley marching his redcoats towards Khartoum. The latter was a colourful example of what could go wrong if you didn’t reach your destination in time. Sir Garnet arrived to discover General Gordon’s severed head stuck on the end of a pike. Lovat always kept half an eye on the narrative and this one ticked all the boxes. When he finally came to write his version of events he would prove himself a master storyteller, recounting a tale splashed with high drama.

Lords of the Desert: The Battle Between the US and Great Britain for Supremacy in the Modern Middle East

by

James Barr

Published 8 Aug 2018

Although the British feared that the Free Officers were a front for some more extreme organisation, on the day after the coup a senior British diplomat, John Hamilton, went to see Neguib to tell him that his government viewed the takeover as an internal matter and would only intervene if foreign lives were threatened. To Neguib, who had been born and brought up in British-run Khartoum, the experience was oddly familiar. ‘Y’know Hamilton,’ he reminisced, as he copied out what the British diplomat was telling him, ‘this reminds me of taking dictation at Gordon College.’27 It appears that the Free Officers had not considered what to do about the king, who was in Alexandria. After reports reached them that he had asked the British to intervene, they briefly considered court-martialling and shooting him, before Ali Maher intervened.

Liberalism at Large: The World According to the Economist

by

Alex Zevin

Published 12 Nov 2019

‘But bad as some of its features may have been’, surely they ‘would be glad to return to it’ – given the ‘paralysis of industry’, ‘growth of official corruption’, ‘revival of torture’, ‘diminishing security of life and property’, and ‘other Oriental abominations’.46 Any new regime in Cairo would, meanwhile, be submitted to all the powers of Europe for ‘sanction’ – a point to which it returned even as it cheered the rout of Arabi by 31,000 Anglo-Indian troops in September.47 Here tutelage proved unavoidable: ‘we have tried to govern Egypt through its treasury, and the attempt has failed.’48 So during the ‘temporary occupation’ that followed, the paper tinkered with different policies to make ‘financial control’ both inconspicuous and inescapable.49 In practice, the Economist rarely paused to draw a critical breath between colonial wars, even when these arose from the unintended consequences of a previous one. Invading Egypt further weakened the Khedival ruling structure, for example, opening the door to a rebellion in Egypt’s own southern colony of Sudan. When the capital Khartoum fell to the jihadi forces of the Mahdi in 1885, the paper demanded vengeance – in uncharacteristically shrill tones – for a no less messianic figure, General Gordon, who had stayed in the city despite orders to evacuate: ‘The Englishmen in the Soudan have shown the best qualities of the national character, and their achievements will always hold a conspicuous place in the annals of British heroism.’50 More typical of the Economist’s justification of British imperial greed was the case it made a few months later for the seizure of the rest of Burma not already coloured red, and the destruction of a monarchy and monkhood that had structured its society for over a millennium.