The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can't Stand Positive Thinking

by

Oliver Burkeman

Published 1 Jul 2012

For all these reasons – and also because it is a conveniently short drive from central Nairobi, with its international airport and comfortable business hotels – Kibera has become a world-famous landmark of suffering. Prime ministers and presidents travel there for photo-opportunities; television news crews come regularly to gawp; and the slum has disproportionately become the focus of hundreds of aid groups, many of them religious, mostly from the United States and Europe. Their names reflect the sense of agonised desperation for which the name ‘Kibera’ has come to stand: the Fountain of Hope Initiative; Seeds of Hope; Shining Hope for Communities; the Kibera Hope Centre; Kibera In Need. But ask Norbert Aluku, a lanky young social worker, born and raised in Kibera, if his childhood there was one of misery and suffering, and he will laugh at you in disbelief.

…

There were numerous other tiny shop-front churches, too, hidden among the homes – dark one-room shacks in which a minister could be seen preaching to an audience of two or three, or playing hymns on a Casio keyboard. But in the opinion of Frankie Otieno, a twenty-two-year-old resident of Kibera who spent his Sundays not worshipping but attending to his various business interests, these smaller churches were essentially scams. ‘In Kibera, a church is a business,’ he said, his easy smile tinged with cynicism. He was sitting on a tattered sofa in the shady main room of his mother’s house in Kibera, drinking Coke from a glass bottle. ‘A church is the easiest way to get money from the aid organisations. One day, you fill up your church with kids – somebody who’s dirty, somebody who’s not eating – and then the organisation comes and sees the church is full, and they take photos to show their sponsors, and they give you money.’

…

This is the difficult truth that strikes many visitors to Kibera, and they struggle for the words to express it, aware that it is open to misinterpretation. Bluntly, Kiberans just don’t seem as unhappy or as depressed as one might have expected. ‘It’s clear that poverty has crippled Kibera,’ observes Jean-Pierre Larroque, a documentary filmmaker who has spent plenty of time there, ‘but it doesn’t exactly induce the pity-inducing cry for help that NGOs, church missions, and charity groups would have you believe.’ What you see instead, he notes, are ‘streets bustling with industry’. Kibera feels not so much like a place of despair as a hotbed of entrepreneurialism.

Money, Real Quick: The Story of M-PESA

by

Tonny K. Omwansa

,

Nicholas P. Sullivan

and

The Guardian

Published 28 Feb 2012

Alube has started at least 15 savings groups, and many in turn have spread the gospel and knowledge to others. Charles Oronje, for example, a skilled furniture maker who lives in Kibera, started the Gatwikera Railway Savings Club in 2004; three years later, the group counted 54 members, many of whom disappeared during the post-election violence. “In my own groups, I have to start very simply,” Lukas told Kim Wilson, a microfinance specialist at The Fletcher School, who visited Kibera. “With ‘dear ones’ [the poorest of the poor] I must begin at the beginning. These members are often new to Kibera, are out of money, frightened, and a little desperate.” The basic group is a merry-go-round, a savings mechanism used by the poor around the world, even in developed countries.

…

Says Betty Mwangi, general manager, Safaricom: “M-PESA is like oxygen to Kenyans.” Imagine 50 other countries with huge proportions of unbanked citizens inhaling a similar breath of fresh air into their economies. Like many residents of Kibera, Mercy, a stocky woman with close-cropped hair and bright eyes, comes from a rural “upcountry” area of Kenya. She moved to Kibera 15 years ago, she says, because of low rent and a relative who could help her find a job and a place to live. Her house is a typical Kibera shack with a corrugated tin roof and mud floor. Bed sheets hang from the ceiling to divide the structure into separate sections to afford a measure of privacy to Mercy and the nine other people who, remarkably, all share the 15’ x 15’ structure.

…

Forget speed, convenience, safety—they just needed cash anyway they could get it. M-PESA payments started coming from the village to the city, particularly the large urban slum settlement of Kibera, a city within the city of Nairobi. Agents found that urban customers were making withdrawals instead of deposits. Once desperate for e-float, agents now scrambled to find cash with the banks closed. Olga Morawczynski, an anthropologist who studied money flows between Kibera and the farming village of Bukura in Western Kenya, observed this dramatic shift. The shift was temporary, but significant—money was flowing at the so-called base of the pyramid, from the poor to the poor.

Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia

by

Anthony M. Townsend

Published 29 Sep 2013

But with the new chart living online in OpenStreetMap, Map Kibera is focused instead on powering new tools that change how the community is represented in the media, and how organizers lobby the government to address local problems. Voice of Kibera, for instance, is a citizen-reporting site built using another open-source tool called Ushahidi. The name means “testimony” in Swahili, and it was developed in 2008 to monitor election violence in Kenya. Voice of Kibera plots media stories about the community onto the open digital map, and allows residents to send in their own reports by SMS. Another Map Kibera effort recruits residents to monitor the progress of infrastructure projects.

…

In 2000 the city began funding the effort and in just two years it had surveyed some two-thirds of Pune’s 450 slum settlements, mapping some 130,000 households. The effort to put Kibera on the map was started by two geeks from the rich world, Erica Hagen and Mikel Maron, who in 2009 joined forces with a trio of Kenyan community-development groups to launch Map Kibera. They recruited a handful of twentysomethings who were active in the community, one from each of the slum’s thirteen villages. With just two days of training in how to use consumer-grade GPS receivers, these volunteer mappers were sent out to traverse Kibera on foot, using their bodies as tools to collect traces of the thousands of streets, alleys, and paths that would form the first-ever digital base map of the thriving community.

…

Using this tool, residents can post reports on the actual state of construction, frequently contradicting the government’s own claims. Over time, slowly but surely, the map is helping shift public perception of Kibera away from flying bags of crap and toward a view of a community of real people. As Maron told me, “People like living in Kibera. What they don’t like is having raw sewage running by their house.”41 Map Kibera represents a shift in how we think about using technology to help poor communities. We can ship all of the laptops we want to the world’s slums, but we can’t force anyone to use them, and even if they do we certainly can’t guarantee it will have the intended impact.

Pax Technica: How the Internet of Things May Set Us Free or Lock Us Up

by

Philip N. Howard

Published 27 Apr 2015

Oksana Grytsenko, “Ukrainians Crowdfund to Raise Cash for ‘People’s Drone’ to Help Outgunned Army,” Guardian, June 29, 2014, accessed September 30, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/29/outgunned-ukrainian-army-crowdfunding-people-drone. 15. “Map Kibera,” accessed June 20, 2014, http://mapkibera.org/. 16. Brian Ekdale, “Slum Tourism in Kibera: Education or Exploitation?” Brian Ekdale’s Blog, July 13, 2010, accessed September 30, 2014, http://www.brianekdale.com/slum-tourism-in-kibera-education-or-exploitation/. 17. Robert Neuwirth, The Hidden World of Shadow Cities, TEDGlobal, 2005, accessed September 30, 2014, http://www.ted.com/talks/robert_neuwirth_on_our_shadow_cities. 18.

…

Authoritarian regimes face the digital dilemma repeatedly: once when deciding whether or not to allow internet access, again when people (invariably) start involving their devices in politics, and yet again when citizens demand access to the latest televisions, phones, and other consumer electronics that constitute the internet of things. Finding Kibera The Map Kibera project in Nairobi, Kenya, is one example of how this process has helped a marginalized community figure out its strengths and understand its needs.15 This act of citizen mapping has made invisible communities visible. And it demonstrates how the internet of things is helping people bring stability to the most anarchic of places.

…

Once there he found a community with immense amounts of economic, cultural, and social capital that had no strong institutions. Kibera is a place where hundreds of thousands of people live. For decades it has been politically invisible because no public map recognized the boundaries of the community, and leaders didn’t pay much attention to its needs. Some people call it Africa’s largest slum, while the people there call it home. Estimates vary about how many people actually live there. Some estimate 170,000, others say upward of a million.16 Whatever the real number is, it is an enormous area and a blank spot on the map until 2009. In fact, many government maps still identify Kibera as a forest. Even Google Maps reveals few details for one of the most crowded and impoverished slums on the planet.

Empty Planet: The Shock of Global Population Decline

by

Darrell Bricker

and

John Ibbitson

Published 5 Feb 2019

But a few kilometers from downtown Nairobi—a short, white-knuckle ride by matatu, the local minibuses Kenyans use to get around—is Kibera. The most populous slum in Africa, and maybe the world, is home to about a quarter million souls.190 Kibera represents the flip side of the dual realities of Nairobi: Downtown. Kibera. The place is an assault on the senses, beginning with an overload of the color red. Red rust stains the tin roofs laid out as far as the eye can see. The muddy soil that tracks between the riot of shacks and makes up the potholed, random dirt roads and paths is red. The smell, for a pampered Westerner, is hard to describe or forget. There are no formal sanitary facilities in Kibera, and open sewers run wherever there is open ground.

…

The men would return for a piece of recycled hardware, or for a part for an older car. Whatever they need is on offer in Kibera, and at a better price than in any modern store. Kibera is also the home for new arrivals—either migrants from the countryside or those moving from other communities. Manhattan a century ago had its Lower East Side; Nairobi today has Kibera. While poverty, terrible sanitation, social pathologies (such as alcohol abuse and teen pregnancies), corruption, and crime are all rampant, these don’t make the community a no-go zone for Kenyans from other parts of Nairobi. Kibera is a distinct center for cultural and commercial interactions, like any historical ethnic enclave in a major Western city.

…

There are no formal sanitary facilities in Kibera, and open sewers run wherever there is open ground. There are also random piles of garbage, with adults, children, and animals picking through them. To Western eyes, Kibera is dystopic, hopeless squalor. Not so for Kenyans. To them, Kibera is a community with a distinct culture and purpose. It is as much Nairobi as the modern downtown. Kibera is also the seat of the traditional economy. It is overrun with informal businesses—food stalls, small grocers, butchers, secondhand clothing stores, repair shops. Some are established stalls or stores, others are just blankets spread out on the ground with whatever is on offer.

The Starfish and the Spider: The Unstoppable Power of Leaderless Organizations

by

Ori Brafman

and

Rod A. Beckstrom

Published 4 Oct 2006

We saw this proliferation of circles firsthand when we visited TAKING ON DECENTRALIZATION Kenya. Just outside of downtown Nairobi, the Kibera slum is the worst in Africa. Joseph, a warm man in his late fifties, was our guide as we walked unpaved streets where a million people live on six hundred crowded acres with no running water, no electricity, and no sewage service. The streets were muddy (at least we told ourselves it was mud), and there was garbage everywhere. The living conditions in Kibera are so harsh that the average life span is thirty-eight years—and dropping. A typical home in the slum is a nine-by-ninefoot tin shack where a family of eight to ten people is crowded together.

…

What could be called the "living room" is typically separated from the "bedroom" by a torn bed-sheet. We went inside several of these homes and for the first time in our lives fully realized what it's like to have absolutely nothing. Although the people of Kibera don't have any of our material comforts, they are starting to see how we live—fancy cars, big houses, fast food. A part of them wants these comforts, but another part of them resents that Western expansion is changing their traditional way of life. In slums like Kibera, the resentment is so strong that at times people turn to extreme measures. If you're living in the slums, you can't start a traditional army, but you can start a circle.

…

If you're living in the slums, you can't start a traditional army, but you can start a circle. Imagine how stunned we were when Joseph, our guide, subtly gestured toward a group of middle-aged men sitting outside a doorway smoking and told us, "Look. Over there. See down that alley? There's an Al Qaeda cell there." Al Qaeda has reached the Kibera slum. Circles can communicate with one another through cell phones and e-mail; a cell in Kibera can now easily and regularly communicate with a cell in Kabul, Munich, or New York. In response to Al Qaeda s attacks, the U.S. government has THE STARFISH AND THE SPIDER hunkered down and become more centralized. This is a big shift from its original roots as a fairly decentralized system.

Lonely Planet Kenya

by

Lonely Planet

However, following Kenyan independence in 1963, housing in Kibera was rendered illegal by the government. But this new legislation inadvertently allowed the Nubians to rent out their property to a greater number of tenants than legally permitted and, for poorer tenants, Kibera was perceived as affordable despite the questionable legalities. Since the mid-1970s, though, control of Kibera has been firmly in Kikuyu hands; the Kikuyu now comprise the bulk of the population. Orientation Kibera is located southwest of central Nairobi. The railway line heading to Kisumu intersects Kibera, though the shanty town doesn’t actually have a station.

…

With the area heavily polluted by open sewers, and lacking even the most basic infrastructure, residents of Kibera suffer from disease and poor nutrition, not to mention violent crime. Although it’s virtually impossible to collect accurate statistics on shanty towns, as the demographics change almost daily, the rough estimates for Kibera are shocking enough. According to local aid workers, Kibera has one pit toilet for every 100 people; the shanty town's inhabitants suffer from an HIV/AIDS infection rate of more than 20%; and four out of every five people living here are unemployed. History The British established Kibera in 1918 for Nubian soldiers as a reward for service in WWI.

…

However, this railway line does serve as the main thoroughfare through Kibera, and you’ll find shops selling basic provisions along the tracks. Visiting the Shanty Town A visit to Kibera is one way to look behind the headlines and, albeit briefly, touch on the daily struggles and triumphs of life in the town; there’s nothing quite like the enjoyment of playing a bit of footy with street children aspiring to be the next Didier Drogba. Although you could visit on your own, security is an issue and such visits aren’t always appreciated by residents. The best way to visit is on a tour. Two recommended companies are Explore Kibera and Kibera Tours. Getting There & Away You can get to Kibera by taking bus 32 or matatu 32c from the Kencom building along Moi Ave.

Blueprint for Revolution: How to Use Rice Pudding, Lego Men, and Other Nonviolent Techniques to Galvanize Communities, Overthrow Dictators, or Simply Change the World

by

Srdja Popovic

and

Matthew Miller

Published 3 Feb 2015

True, toppling Mubarak or Milošević is an amazing achievement, but you don’t have to be groaning under a dictatorship to apply the principles of people power; they are universal, and they apply no matter who you are and what your problem may be. If you still have doubts about the power of ordinary hobbits like our good friend Kathy, consider the residents of Kibera. The biggest slum in Nairobi, Kenya—and by some accounts the largest slum in the world, with as many as ve million people huddling together in squalor—Kibera presented its residents with all the threats you’d expect to nd in one of the world’s worst hellholes. The landscape was terrifying. There was Jamhuri Park, where the bushes were thick and the trees cast a perpetual shadow, making it a favorite spot for local rapists.

…

Then you had the Nairobi dam, which served as a Holiday Inn for bandits, and if you walked down the central Karanja Road on payday, you were almost certain to be robbed. And then there were the ying toilets. Since there wasn’t a widespread or e cient sewer system in the Kibera slum, many residents were forced to do their business in ditches along the streets. But at night, when it was too dangerous for people to dart out of their homes even for a minute in order to relieve themselves, Kiberans simply went to the bathroom in a plastic bag, tied it up, and tossed it out the window: a ying toilet. Needless to say, there were plastic bags everywhere. Kibera, as you could imagine, was not an easy place to live in. In order to survive, you needed to really know your way around.

…

To their delight, many people began adding their own spots to the maps, and soon their database grew to ve hundred data points and then to hundreds and hundreds more. Taking note of the project, the United Nation Children’s Fund got involved and doled out some cash. Soon every resident of Kibera could receive maprelated alerts via text messages sent directly to their cell phones, a service that helped people stay clear of everyday crime and outbreaks of violence in the neighborhood. Block by block, district by district, the Kiberans were reclaiming their community. The young men and women in Kibera are prime examples of people power harnessed to great use. Unlike many of the other examples in this book, these guys didn’t seek out corrupt enemies to overthrow or freedoms to win.

Code Dependent: Living in the Shadow of AI

by

Madhumita Murgia

Published 20 Mar 2024

When we’d met virtually during the coronavirus lockdown two years ago to talk about Sama and his work, Ian had been a skinny kid with a shy smile and a scraggly moustache. Today, he is walking us to his new home which he shares with his wife and four-month-old baby in the heart of Kibera. ‘Things are different,’ he says. The neighbourhood of Kibera in central Nairobi is an informal settlement, or a slum, one of the largest in Africa that houses some of the country’s poorest families. This undercity of a million people is constantly moving, a flowing stream of camaraderie, haggling and humanity. We bob along like paper boats on its currents.

…

Benja, too, was a rabble-rouser for hire, paid by local politicians to throw stones at the police. Now, he has just started his own walking tour company. But he also runs a chicken shop, leads a youth political activist organization and is opening a bar. He’s dabbled in selling water and electricity, lucrative businesses controlled by powerful cartels in Kibera. In his spare time, he’s a youth leader in Lindi, one of Kibera’s villages, where he helps prepare kids for formal office-based jobs. ‘I have been able to instil the Sama spirit and the culture into people that I meet in my area. And it goes on and on.’ Ian says he’s brought friends into formal employment too. ‘One guy, my school friend, was into pickpocketing, each and every day he was involved in these crimes,’ he says.

…

‘One guy, my school friend, was into pickpocketing, each and every day he was involved in these crimes,’ he says. ‘When he got the link from me, he joined Sama, he reformed drastically. If I tell you this was the guy, you won’t imagine it, you’ll say I’m lying.’ The mention of crime chastens Benja. He looks at Ian. ‘I wanna move out of Kibera by next year. And I want you to move too.’ ‘It is in my plan, in three years coming, I should be out of Kibera,’ Ian says. ‘But then you have to speed it up.’ Benja cautions him. ‘You have a responsibility to leave. I always told you, hey, you don’t even need to be a team leader at Sama. You can be anything you want in this world. Man, I know you’re going places

Arrival City

by

Doug Saunders

Published 22 Mar 2011

This wattle-and-daub shack is perched amid a lake of similar houses jammed close together across a two-kilometer expanse, separated by narrow alleyways of mud, garbage, and slurries of human waste, a labyrinthine, pungent cluster of almost unimaginably high population density built on hillocks of refuse near the heart of Nairobi. This is the Kianda neighborhood in the Kibera slum, whose inhabitants, numbering close to a million, are perhaps the largest and most infamous slum community in sub-Saharan Africa, subject to disease infestations and bursts of political and gang violence on a terrifying scale. At the end of 2007, Kibera exploded into months of murderous political violence, in which members of the Luo tribe drove Kikuyus out of their neighborhoods, making this an even more ethnically segregated, and dangerous, place. Kibera, like most African slums, is a true arrival city. Though it has existed here for 90 years, created when Kenya’s colonial administration granted some parkland to the homeless Nubian veterans of the First World War, in the post-colonial decades it has become a vital instrument of urbanization, propelling entire villages and districts into the city.

…

This, and the lack of decent employment opportunities for males, leads to thousands of idle young men on the street who turn to theft, drug dealing, or the brewing and selling of homemade liquor to get by, a social stew that prevents Kibera from developing into a successful arrival city. For the privilege of living here, Eunice pays a landlord $17 a month, around half her typical monthly income. The landlord, who rents out hundreds of huts, does not own the land himself; it is municipal land, and his claim to ownership is as ephemeral and insecure as are Eunice’s chances of owning her own property. This lack of secure tenure, more than anything, has contributed to the failure of places like Kibera: If you can’t own your house, it is very hard to rise above your circumstances.20 The solution, in theory at least, is just over the hill.

…

Within sight of Eunice’s shack, rising along the horizon, is a growing cluster of neat, gray, high-rise buildings, with red roofs and small concrete balconies, the site of an expansive slum-redevelopment project, to which Kibera’s residents are, theoretically, to be moved into stable, sanitary, fully-owned apartment housing. It is a project initiated by UN-HABITAT, the United Nations human-settlements agency, whose world headquarters happen to be within walking distance of Kibera. That such a redevelopment project could only be launched three decades after the U.N. set up shop here is telling. That Eunice Orembo believes that she will never live in these houses is even more telling.

Dreaming in Public: Building the Occupy Movement

by

Amy Lang

and

Daniel Lang/levitsky

Published 11 Jun 2012

A few earnest people are talking to some of the DC homeless who stay around the park. I recognize a certain ‘I have come to help Kibera1’ look. And feel ashamed for thinking this. A few cellphones are out, documenting occupation, documenting the homeless. DC is a tourist town. The Kibera-ness of it will not leave me. It is the first time I have felt so close to Kibera while in the States. A man is yelling about Jesus – later in the day, he will yell, ‘Mitt Romney will not save us, Rick Perry will not save us.’ He never says Barack Obama will not save us. * * * I return to McPherson Square with a friend who is bold enough to walk through the park.

…

What he says seems unimportant – too familiar, something already known – but the making too-familiar of others’ narratives is ideological and material violence at its most quotidian. Listening matters. Seeing matters. ‘I speak for the bush’ flashes through my mind. Perhaps the quotidian violence it maps might become less quotidian, less a part of urban modernity. Kibera-ness still nags. * * * I tell my friend I am feeling ungenerous. This is why I see Kibera-ness. But this might not be quite right. Still. I like to pay attention to these moments of unease. We make our way to the Lincoln Memorial, from where a march will ensue to the newly constructed MLK memorial. * * * On our way there, we encounter several joggers – DC is a jogging city – almost all white, almost all male, with a certain busy-ness to them.

…

‘Too many people’ takes on greater significance as we approach the crowds massing around the Lincoln Memorial – mostly black, many with union t-shirts, others sporting t-shirts featuring MLK, Jr. ‘Too many people.’ Kibera-ness beckons. There’s a sense of kinship in the air – groups cluster, families come out together, one seeks inter-generational cohorts. I have been reading Christina Sharpe on Corregidora, about the work of ‘making generations’. I am thinking, now, of the generation-making work taking place through a shared commitment to labor. ‘Workers’ Rights are Human Rights.’ * * * Kibera-ness recedes, as does the US, for a moment, and I think about the courageous Kenyans who occupied the Ministry of Education.2 My frames kaleidoscope: Egypt, Wisconsin, Nairobi, Wangari Maathai.

Planet of Slums

by

Mike Davis

Published 1 Mar 2006

In 1972, Ajegunle contained 90,000 people on 8 square kilometers of swampy land; today 1.5 million people reside on an only slightly larger surface area, and 81 Sharma, Rediscovering Dbaravi, pp. xx, xxvii, 18. 82 James Drummond, "Providing Collateral for a Better Future," Financial Times, 18 October 2001. 83 Suzana Taschner, "Squatter Settlements and Slums in Brazil," pp. 196, 219. 84 Urban Planning Studio, Disaster Resistant Caracas, p. 27. 85 Mohan, Understandingthe DevelopingMetropolis, p. 55. they spend a hellish average of three hours each day commuting to their workplaces.86 Likewise in supercrowded Kibera in Nairobi, where more than 800,000 people struggle for dignity amidst mud and sewage, slum-dwellers are caught in the vise of soaring rents (for chicken-cooplike shacks) and rising transport costs. Rasna Warah, writing for UN-Habitat, cites the case of a typical Kibera resident, a vegetable hawker, who spends almost half her monthly income of $21 on transportation to and from the city market.87 The commodification of housing and next-generation urban land in a demographically dynamic but job-poor metropolis is a theoretical recipe for exactly the vicious circles of spiraling rents and overcrowding that were previously described in late-Victorian London and Naples.

…

The diarrhea associated with AIDS is a grim addition to the problem.80 The ubiquitous contamination of drinking water and food by sewage and waste defeats the most desperate efforts of slum residents to practice protective hygiene. In Nairobi's vast Kibera slum, UNHABITAT's Rasna Warah studied the daily life of a vegetable hawker named Mberita Katela, who walks a quarter mile every morning to buy water. She uses a communal pit latrine just outside her door. It is shared with 100 of her neighbors and her house reeks of the sewage overflow. She constantly frets about contamination of her cooking or washing water — Kibera has been devastated in recent years by cholera and other excrement-associated diseases.81 In Calcutta likewise, there is little that mothers can do about the infamous service privies they are forced to use.

…

In lockstep with the increasing percentage of renters, the most dramatic consequence in the short run has been soaring population density in Third World slums — land inflation in the context of stagnant or declining formal employment has been the piston driving this compression of people. Modern mega-slums like Kibera (Nairobi) and Cite-Soleil (Portau-Prince) have achieved densities comparable to cattle feedlots: crowding more residents per acre into low-rise housing than there were in famous congested tenement districts such as the Lower East Side in the 1900s or in contemporary highrise cores such as central Tokyo and Manhattan.

Progress: Ten Reasons to Look Forward to the Future

by

Johan Norberg

Published 31 Aug 2016

Another important reason given is that schools do not have suitable hygiene facilities.15 The greatest proportion without water and sanitation lives in sub-Saharan Africa. When I walk around Kibera, in Nairobi, Kenya, one of Africa’s largest urban slums, I meet people who have to take an hour or more per day just to locate a water vendor and wait in line to be served. Some pay as much as a tenth or even a fifth of their income to get water. The inhabitants of Kibera were never granted deeds to land, so the buildings are outside the law, with little access to infrastructure and without the security in their possessions that would make investments in these areas possible. Everywhere in Kibera I notice open sewers. When it is raining, the waste flows through the streets.

…

When you walk around in the mornings you see piles of flying toilets in alleyways and on rooftops, from which people also harvest rainwater. Children play with these wrapped bags as balls during leisure time. The flying toilet contributes to disease and early death in Kibera and many other slums around the world. The most common diseases in Kibera are all environment-related. Infant mortality is three times higher than in the rest of Nairobi. But even a local health worker admits to using the flying toilet all the time: ‘At night, it is so dark in Kibera that you cannot dare to get out of your room since you are not sure if you will fall in one of the abandoned toilets and, as a woman, you can never be sure that you will not be raped.’16 But things are changing even here.

…

Instead of toilets, there are latrines, not much more than holes in the ground with planks across for people to put their feet on. They can be shared by several hundred people, and they are often full of waste and reeking with urine. When they are full, they are emptied into the river. Women are afraid to go, especially at night, and children fear falling inside, which sadly they often do. For all these reasons, Kibera has its own version of ‘Gardyloo!’, called ‘flying toilets’. Kiberans relieve themselves in black polythene bags and at night they throw them away as far from their home as possible. The neighbour in turn sometimes throws it further away, and so on, until it is out of sight. The rain often washes them down into the river.

It's Our Turn to Eat

by

Michela Wrong

Published 9 Apr 2009

I tell my wife: “There's no way, long term, those guys are going to accept to die of hunger when the smell of your chapattis is wafting over the wall.”’ The biggest slum is Kibera, virtually an obligatory stop these days on visiting VIPs' itineraries. Kibera, bizarrely, lies within a tee shot's distance of Nairobi's golf club. Aerial photographs show the neat green medallion that is the club abutting what looks like a brown sea of broken matchsticks, in fact the corrugated-iron mabati roofs of between 800,000 and 1.2 million residents, prompting the immediate mental query: ‘Why don't they just invade?’ Kibera is where the phrase ‘flying toilets’ was added to the English language, a description of the method used to dispose of faeces – dump it in a plastic bag and throw it out of the window – by residents who couldn't be bothered walking to the public latrine.

…

Nairobi's first slums were mono-ethnic, the result of colonial attempts to corral Africans into distinct, controllable areas during the Emergency years. The newer ones started out that way, but the phenomenon didn't last long. Often dubbed a Luo settlement, Kibera itself actually contains forty-two separate tribes, ‘all doing their jig together’, as an official from the UN's Habitat told me. Ethnicity blurred in playgrounds, schools, universities and offices. ‘When people first arrive in Kibera, they initially go to where their people are and look for work. They arrive with nothing, so to cut costs they sleep six to a room. The longer they live together, the more they fuse.

…

Kenyan writer BINYAVANGA WAINANA A brown clod of earth, trailing tufts of grass like a green scalp, suddenly soared through the air and landed on the stage, thrown by someone high on the surrounding slopes. Then another one sailed overhead, this time falling short and hitting the journalists packed against the podium. Then came some sticks, a hail of small stones. The first rows of the crowd hunched their shoulders and hoped it would get no worse: there were plenty of kids up there from Kibera slum, the sprawl of rusty shacks that stretched like an itchy brown sore across the modern city landscape, and they had a nasty habit of using their own excrement as missiles. The mood in the open-air stadium in Uhuru Park on 30 December 2002, a year and a half before that strange meeting in the finance ministry, was on the brink of turning ugly.

City 2.0: The Habitat of the Future and How to Get There

by

Ted Books

Published 20 Feb 2013

Community-based groups like Shack/Slum Dwellers International have enlisted citizens to conduct their own censuses and create their own maps, which they publish on open online platforms, thereby expanding our collective knowledge of cities. Map Kibera, for instance, used youth volunteers with handheld GPS units and the wiki OpenStreetMap to create a detailed map of the most famous informal settlement in Nairobi. Until Map Kibera, most government maps showed the area as a forest. The project revealed the network of paths and roads and showed locations of churches, clinics, and stores. Residents of Kibera are now using the map as a platform to report uncompleted or badly built government projects, countering official reports and often exposing corruption.

…

Residents of Kibera are now using the map as a platform to report uncompleted or badly built government projects, countering official reports and often exposing corruption. Similarly, Transparent Chennai helps informal settlers in the city formerly known as Madras to map their own settlements in relation to (the lack of) government services. These efforts combine local knowledge with technology to engage planners and city leaders. The desolate, official map of Kibera, shown at left from Google Maps, reflects nothing of the dense life visible in Google’s satellite view. These two images were accessed on the same day in December 2012, minutes apart. The use of technology is, like the autocatalytic city, built up incrementally responding directly to needs. Nowhere is the power of this process more pronounced than in transportation.

What's Yours Is Mine: Against the Sharing Economy

by

Tom Slee

Published 18 Nov 2015

More encouragingly, Donovan looks at how some “data geeks” recognized their own myopia in the Map Kibera project, which started as a community-mapping project to trace the massive Nairobi slum. Some questioned the need for the project as “locals [already] knew their surroundings intimately.” Making mapping information available would more likely benefit external parties than the residents themselves. The problems the project seeks to address are what Donovan calls “wicked problems: ill-defined, tangled, and resistant to technological fixes.” However, Although it began as an example of misdiagnosing a wicked problem (Kibera’s poverty and marginalization) as a tame one (insufficient information availability), Map Kibera has admirably grown beyond a reductionist approach; it has expanded to include other forms of activity such as citizen reporting, and has taken steps to ensure local ownership of the project.

…

However, Although it began as an example of misdiagnosing a wicked problem (Kibera’s poverty and marginalization) as a tame one (insufficient information availability), Map Kibera has admirably grown beyond a reductionist approach; it has expanded to include other forms of activity such as citizen reporting, and has taken steps to ensure local ownership of the project. The project has moved beyond a technological goal to a set of social goals. Its list of sponsors, interestingly, includes only non-commercial organizations. Donovan contrasts Map Kibera’s evolution with that of more narrowly technological mapping projects, such as Google’s Map Maker initiatives, which have been accused of unethical “exploitation of open communities.” 49 The danger of such projects is that, by eliminating the illegibility that privileges local knowledge over outsider knowledge, they may allow the already powerful to gain access to community knowledge that was previously hidden from them: to “see like a slum.”

The Health Gap: The Challenge of an Unequal World

by

Michael Marmot

Published 9 Sep 2015

An academic in Kenya, for example, wanted to raze to the ground the slum of Kibera, close to the centre of Nairobi, and transfer to new-build housing, out of town, the half-million people who currently live in Kibera. He had no idea if that was what the people of Kibera wanted, but he knew that the land thus liberated was potentially valuable real estate that, in his view, could be put to ‘better’ use than housing poor people. And the poor people? They should be grateful for what they ended up with. I wish I were caricaturing. To put it in context, Kibera, reportedly the biggest urban slum in Africa, has a lot wrong with it.

…

It is a makeshift settlement, with makeshift housing and substandard or no services. People pay more for a litre of water, collected in a jerrycan, than a litre of water would cost in London. That said, ‘high streets’ have developed. Shops with advertisements for mobile phones are next to food shops and convenience stores, medical clinics and pharmacies. Kibera is a hotbed of crime, to be sure, but it has aspects of community, too, that would take great effort to reproduce elsewhere, in rows of breeze-block new housing, for example. One way to do it better is shown by what the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA – we met it earlier) has done in Ahmedabad in Gujarat.

…

K., here Gandhi, Mahatma, here, here gangs, here, here Gawande, Atul, here GDP, measurement of, here gender equity, move to, here General Motors, here Georgia, here Gershwin, George, here Glasgow, here, here, here, here, here, here, here combating gang violence, here life expectancy, here, here, here mortality rates, here Glass, Norman, here Gleneagles Summit, here Global Burden of Disease, here global warming, see climate change global wealth, increasing, here Gnarr, Jon, here Goldblatt, Peter, here golf, here Gordon, David, here, here, here, here Gornall, Jonathan, here Göteborg, here Great Gatsby Curve, here Greece, here, here financial crisis and austerity, here, here, here, here green space, here grooming, in apes, here, here Guardian, here Guinea-Bissau, here, here Gunbalanya, here, here, here Hacker, Jacob, here, here Haiti earthquake, here Hampshire, Stuart, here, here HAPIEE studies, here ul Haq, Mahbub, here Hayek, Friedrich von, here health advice, here health and safety regulations, here, here health and well-being boards, here health care systems, here health inequities (definition), here heart disease, here, here, here, here, here, here, here abolition of, here and adverse childhood experience, here, here in Australian aboriginals, here and civil servants, here, here, here and exercise, here and high status, here, here and Japanese migrants, here and job strain, here Hertzman, Clyde, here, here Heymann, Jody, here high blood pressure, here, here, here HIV/AIDS, here, here, here, here homicide, here, here, here Hong Kong, here, here HPA axis, here Human Development Index (HDI), here, here, here, here Hungary, here, here, here Hutton, Will, here Huxley, Aldous, here Hyder, Shaina, here Iceland, here, here, here, here, here ideology, here, here income inequalities, here, here, here, here, here, here India, here, here, here, here average BMI, here caste system and education, here child mortality, here, here, here cotton farmers, here distrust of education system, here income inequalities, here life expectancy, here, here, here, here, here literacy, here scavengers, here, here, here, here see also Kerala infant mortality, here inherited wealth, here Institute of Economic Affairs, here intergenerational earnings elasticity, here International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations, here International Labour Office (ILO), here, here, here, here International Monetary Fund (IMF), here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and impact of structural adjustments, here Ireland, here, here, here, here Israel, here Italy, here, here fertility rate, here maternal mortality, here Jakab, Zsuzsana, here Japan, here, here, here, here life expectancy, here, here, here and team commitment, here, here Japanese-Americans, here, here Jordan, here Judt, Tony, here, here, here Kahneman, Danny, here Kalache, Alex, here, here Karasek, Robert, here Kelly, Yvonne, here Kennedy, Robert, here, here, here Kenya, here, here Kerala, here, here Keynes, John Maynard, here Keynesian economics, here, here, here, here Kibera slum, here King’s Fund, here Kivimaki, Mika, here Kokiri Marae, here, here Krueger, Alan, here Krugman, Paul, here, here Kuznets, Simon, here Labonté, Ron, here labour market flexibility, here Lalonde, Christopher, here Laos, here latency effect, here Lativa, here Lee, J. W., here Lewis, Michael, here Lexington, Kentucky, here libertarians, here, here life expectancy, here, here, here, here among Australian aboriginals, here disability-free, here, here and education, here, here, here, here in former communist states, here and mental health, here and national income, here US compared with Cuba, here Lithuania, here, here, here Liverpool, here, here, here ‘living wage’, here loans, low-interest, here lobbying, here Los Angeles, here ‘lump of labour’ hypothesis, here Lundberg, Ole, here lung cancer, here, here lung disease, here, here, here, here luxury travel, here Macao, here, here McDonald’s, here McMunn, Anne, here Macoumbi, Pascoual, here Madrid, indignados protests, here, here Maimonides, here malaria, here, here, here, here, here Malawi, here male adult mortality, here, here Mali, here, here Malmö, here, here Malta, here Manchester, here, here, here Maoris, here, here, here, here Marmot Review, see Fair Society, Healthy Lives marriage, here Marx, Karl, here maternal mortality, here, here, here maternity leave, paid, here Matsumoto, Scott, here Meaney, Michael, here Medicaid, here Mediterranean diet, here Mengele, Joseph, here mental health, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and access to green space, here and adverse childhood experience, here and austerity, here and fear of crime, here and job insecurity, here and unemployment, here meritocracy, here Mexico, here, here, here, here, here education and cash transfers, here, here Millennium Birth Cohort Study, here, here Minimum Income for Healthy Living, here, here, here Mitchell, Richard, here Modern Times, here Morris, Jerry, here, here Moser, Kath, here Mozambique, infant mortality, here Mullainathan, Sendhil, here Murphy, Kevin, here, here Muscatelli, Anton, here Mustard, Fraser, here Mwana Mwende project, here Nathanson, Vivienne, here Native Americans, here Navarro, Vicente, here NEETs, here, here neoliberalism, here, here, here, here, here Nepal, here, here Neruda, Pablo, here Netherlands, here, here New Guinea, here, here NEWS group, here, here Nietzsche, Friedrich, here, here Niger, here nitrogen dioxide, here, here non-human primates, here Nordic countries and commission report, here and social protection, here, here, here, here, here see also individual countries Norway, here, here, here, here, here, here life expectancy and education, here, here Nottingham, here Nozick, Robert, here obesity, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here in children, here, here and diabetes, here and disincentives, here food corporations and, here genetic and environmental factors in, here and migrant studies, here and rational choice theory, here social gradient in, here, here, here, here in women, here, here Office of Budget Responsibility, here Olympic Games, here opera, here Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), here, here, here, here, here, here, here organisational justice, here Orwell, George, here Osler, Sir William, here Panorama, here Papua New Guinea, here ‘paradox of thrift’, here Paraguay, here, here, here parenting, here, here, here, here and work–life balance, here pay, low, here pensions, here, here, here, here Perkins, Charlie, here Peru, here, here, here physical activity and cognitive function, here green space and, here Pickett, Kate, here Pierson, Paul, here, here Piketty, Thomas, here, here, here, here Pinker, Steven, here Pinochet, General Augusto, here PISA scores, here, here, here, here, here Poland, here, here, here, here Popham, Frank, here Porgy and Bess, here poverty, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and aboriginal populations, here, here absolute and relative, here, here child poverty, here, here, here, here, here and choice, here and early childhood development, here, here effect on cognitive function, here and urban unrest, here and work, here Power, Chris, here pregnancy, here preventive health care, here ‘proportionate universalism’, here puberty, and smoking here public transport, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here Ramazzini, Bernardino, here RAND Corporation, here, here, here rational choice theory, here, here, here rats, and brain development, here Rawls, John, here, here Reid, Donald, here Reinhart, Carmen, here, here reproduction, control over, here retirement, here reverse causation, here Reykjavik Zoo, here Rio de Janeiro, here, here Rogoff, Kenneth, here, here Rolling Stones, here Romania, here Romney, Mitt, here Rose, Geoffrey, here Roth, Philip, here Royal College of Physicians, here Royal Swedish Academy of Science, here Russia, here, here, here and alcohol use, here life expectancy, here, here, here, here Sachs, Jeffrey, here, here St Andrews, here San Diego, here Sandel, Michael, here, here Sapolsky, Robert, here Scottish Health Survey, here Seattle, here Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), here, here, here, here Sen, Amartya, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and Jean Drèze, here, here, here, here serotonin, here sexuality, here, here see also reproduction, control over sexually transmitted infections, here, here Shafir, Eldar, here Shakespeare, William, here, here, here, here Shanghai, here Shaw, George Bernard, here, here Shepherd, Jonathan, here shootings, here Siegrist, Johannes, here Sierra Leone, here, here, here Singapore, here, here Slovakia, here Slovenia, here, here smallpox vaccinations, here Smith, Adam, here Smith, Jim, here smoking, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here declining rates of, here, here and education, here and public policy, here social gradient in, here, here and tobacco companies, here and unemployment, here Snowdon, Christopher, here social cohesion, here, here, here, here, here, here, here social mobility, here, here social protection, here ‘social rights’, here Social Science and Medicine, here Soundarya Cleaning Cooperative, here South Korea, here, here, here, here Spain, here, here, here Spectator, here sports sponsorship, here Sri Lanka, here Stafford, Mai, here Steptoe, Andrew, here Stiglitz, Joseph, here, here, here, here, here stroke, here, here, here structural adjustments, here, here Stuckler, David, here suicide, here, here, here, here, here and aboriginal populations, here, here and Indian cotton farmers, here and unemployment, here, here suicide, attempted, here Sulabh International, here Sun, here Sure Start programme, here Surinam, here Sutton, Willie, here Swansea, here Sweden, here, here, here, here, here, here, here life expectancy and education, here, here male adult mortality, here, here Swedish Commission on Equity in Health, here Syme, Leonard, here, here, here Taiwan, here, here Tanzania, here taxation, here Thailand, here Thatcher, Margaret, here Theorell, Tores, here tobacco companies, here Topel Robert, here Tottenham riots, here Tower Hamlets, here, here Townsend, Peter, here trade unions, here, here, here, here traffic calming measures, here Tressell, Robert, here ‘Triangle that Moves the Mountain’, here, here trickle-down economics, here, here Truman, Harry S., here tuberculosis, here, here, here, here Tunisia, here Turandot, here, here Turkey, here, here Uganda, here, here unemployment, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and mental health, here and suicide, here, here youth unemployment, here, here, here, here UNICEF, here, here United Kingdom alcohol consumption, here capital:income ratio, here and child well-being, here cost of childcare, here and economic recovery, here, here education system, here, here disability-free life expectancy, here founding of welfare state, here health-care system, here income inequalities, here, here literacy levels, here male adult mortality, here PISA score, here politics and economics, here and poverty in work, here, here poverty levels, here, here prison population, here social attitudes, here and social interventions, here social mobility, here ‘strivers and scroungers’ rhetoric, here, here and taxation, here unemployment, here use of tables for meals, here United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), here, here, here, here United States of America air pollution, here, here alcohol consumption, here capital:income ratio, here child poverty, here and child well-being, here cotton subsidies, here and economic recovery, here education system, here, here, here female life expectancy, here and gang violence, here health-care system, here, here income inequalities, here, here, here, here international comparisons, here, here, here lack of paid maternity leave, here life expectancy and education, here male adult mortality, here, here, here maternal mortality, here, here obesity levels, here, here, here, here PISA score, here politics and economics, here and poverty in work, here poverty levels, here prison population, here race and disadvantage, here, here, here, here, here social disadvantage and health, here social mobility, here suicide rate, here and taxation, here US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, here US Department of Justice, here US Federal Reserve Bank, here US National Academy of Science (NAS), here, here, here, here University of Sydney, here urban planning, here Uruguay, here, here, here, here utilitarianism, here, here, here Vågerö, Denny, here valuation of life, here Victoria Longitudinal Study, here Vietnam, here, here violence, here domestic (intimate partner), here, here, here Virchow, Rudolf, here vulture funds, here, here Wales, youth unemployment in, here walking speed, here Washington Consensus, here, here, here welfare spending, here West Arnhem College, here Westminster, life expectancy in, here Whitehall Studies, here, here, here, here, here, here, here wife-beating, here Wilde, Oscar, here, here Wilkinson, Richard, here willingness-to-pay methodology, here, here Wolfe, Tom, here, here women and alcohol use, here and cash-transfer schemes, here A Note on the Author Born in England and educated in Australia, Sir Michael Marmot is Professor of Epidemiology and Public Health at UCL.

Geek Heresy: Rescuing Social Change From the Cult of Technology

by

Kentaro Toyama

Published 25 May 2015

A Tale of Two Approaches When Smith said, “Talent is universal; opportunity is not,” she was quoting an epigraph from a memoir, It Happened on the Way to War, by former Marine captain Rye Barcott. Barcott was an officer-in-training in 2000 when he visited Kibera, the largest slum in Nairobi, and his eyes were opened to global poverty. Feeling compelled to do something about it, he worked with local residents Tabitha Atieno Festo and Salim Mohamed to found a nonprofit organization called Carolina for Kibera (CFK), which has since been honored for its work by Time magazine and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The organization runs health and education programs and trains youth leaders to solve community problems.

…

If so, I’d be wrong that more technology by itself doesn’t help social causes, but that would also mean that our social system tends toward greater poverty unless new technologies are invented at a breakneck pace. That is an even darker scenario, which, if true, would only further justify the overall thesis of Part 2: that we need to pay more attention to social forces rather than to technological ones. 14.Carolina for Kibera (n.d.). 15.Of course, it’s understandable that corporate spin highlights products even if executives praise employee talent. The problem occurs when the rest of society drinks the Kool-Aid. And it does. I once had a conversation with an influential Harvard development economist in which I mentioned the importance of growing wisdom in people.

…

Informal Sociology: A Casual Introduction to Sociological Thinking. Random House. Caplan, Bryan. (2012). Selfish reasons to have more kids: Why being a great parent is less work and more fun than you think. Basic Books. Carlin, George. (1984). Carlin on campus. HBO, April 19, 1984. Carolina for Kibera. (n.d.). Stories: Steve Juma, http://cfk.unc.edu/ourimpact/stories/. Carr, Nicholas. (2011). The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains. W. W. Norton. CBS News. (2007). What if every child had a laptop? May 20, 2007, www.cbsnews.com/news/what-if-every-child-had-a-laptop/. Center for American Women and Politics. (2014). 2014: Not a landmark year for women, despite some notable firsts.

Left Behind

by

Paul Collier

Published 6 Aug 2024

In the heart of Nairobi sits the enormous Kibera slum. Although covering only one square mile, it is often claimed to be Africa’s most populous slum, the best guess being that about a quarter of a million people live there. Being in the inner city, it could become part of the central business district, which would enhance its contribution to the economy. By one serious estimate, by maintaining its current low-value use the economy is losing future value of around $2 billion. Yet policies are gridlocked because the land ownership is contested. The legal owners of the land in Kibera are a small group of very well-connected people: generals, top civil servants and politicians.

…

It used its power to introduce an invisible land tax. Addis Ababa had experienced growth in such a haphazard manner that to find public land on which apartment blocks could be built it was not necessary to use land on the periphery: there were pockets of empty land well within the city’s boundaries as well as shack-land slums like Kibera. To upgrade shack-land while avoiding the high costs of retrofitting, new infrastructure would need to be installed only once the whole area had been bulldozed, so that rebuilding could be done at scale on a greenfield site. The political economy challenge was to persuade an entire neighbourhood community to move out so that a site could be cleared.

World Travel: An Irreverent Guide

by

Anthony Bourdain

and

Laurie Woolever

Published 19 Apr 2021

It grew up around a British railroad depot during the colonial era, halfway between other British interests in Uganda and the coastal port of Mombasa.” The largest neighborhood in the city is Kibera. “Kibera is massive—around 172,000 people live here. A sprawling warren of homes, places of worship, and small businesses competing for an edge. It houses a great part of Nairobi’s labor force. Meaning, no Kibera? The city grinds to a halt.” Stop by Mama Oliech’s, a small, local chain that distinguishes itself through the use of local wild fish from Lake Naivasha, not the Chinese farmed tilapia that is far more ubiquitous in Nairobi.

Black Code: Inside the Battle for Cyberspace

by

Ronald J. Deibert

Published 13 May 2013

Each LRA-related incident is plotted on a map by type – civilian death, injury, abduction, looting – and once consolidated, the map shows the movements of the LRA across the region, and the scope, scale, and frequency of its actions. Incidents captured by cellphone cameras are linked to specific events on the website as corresponding evidence. In Kibera, Nairobi, Kenya’s largest slum, an experiment in crowd-sourcing data may revolutionize access to basic health care and sanitary services. Conditions in Kibera are dire: most residents are illegal squatters, and local officials regularly withhold basic services, including electricity, sewage treatment, and garbage collection. The most important commodity, water, is extremely scarce – turned on and off by capricious officials, and grossly overpriced by private dealers.

Instant City: Life and Death in Karachi

by

Steve Inskeep

Published 12 Oct 2011

In other words, half of the inhabitants of the largest city of a nation founded by a lawyer—a lawyer whose face and name where everywhere—were now living in the realm of the extralegal. And this was typical of cities across much of the developing world. Karachi’s katchi abadis were rough equivalents of the vast settlement called Kibera that was growing at the edge of Nairobi, or the crowded slum of Dharavi in the heart of Bombay, or the favelas that climbed the steep hillsides of Rio de Janeiro (and which the Athenian planner Doxiadis, in his plan for Rio, had proposed to demolish). Governments were struggling, and often failing, to deal with social and economic change.

…

Human Rights Commission Hurricane Katrina Hussain, Altaf Hussein ibn Ali (grandson of Prophet Mohammed) Hyatt Regency Hotel Icon Tower Ilyas, Ghulam Ilyas, Najeeb Ilyas, Waqas Inchon India: British divisions among populace Hindus’ migration to independence of Pakistan’s wars with partition of Indian National Congress Indonesia Indus River Indus River Valley industrialization instant cities populations of Investment Advisory Centre of Pakistan Iqbal, Khuram Iran Iraq Babylon ruins in Islam in creation of Pakistan see also Muslims Islam, Zia-ul Islamabad Istanbul IT Tower Jalil, Nasreen Jamaat-e-Islami Jamali, Seemin Jihad jihadi organizations Jinnah, Fatima Jinnah, Muhammad Ali birth of death of tomb of Jinnah Ground Jinnah International Airport road to Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre February 5, 2010 bombing and Jinnah Road as Bandar Road Jubilee Cinema Jundallah Kabul Kamal, Mustafa background of construction projects of Karachi: airport road in alternative government in bird sellers in building boom in 1950s as capital of Pakistan central city and suburban planning and development commuting and electricity supply in ethnic diversity in government in Kamal’s construction projects in literacy in migrants and refugees in monsoons in in 1947 parks in, see parks poor in population growth and expansion of post-traumatic stress suffered in press in religious diversity in seaport of socio-economic survey of transportation and traffic in types of conflicts in unauthorized settlements (katchi abadis) in violence in, see violence water supply in Karachi Boat Club Karachi Gymkhana Karachi Monorail Karachi Municipal Corporation (KMC) Building (old city hall) protesters at Karachi Press Club Karachi University katchi abadis (unauthorized settlements) Kaur, Bibi Inder Kennedy, John F. Kennedy Center Khan, Akhtar Hameed Khan, Ishrat Ul Ebad Khan, Mahboob Khan, Nawaz Khan, Nichola Khan, Wahab Khan, Yahya Khattab, Raja Umer Khuhro, M. A. Kibera kidnappings Kishwar, Romana Korangi Kothari Parade Kumail, Mohammad Kumeli, Abbas Lagos Lahore Landhi land mafias (land grabbers) Langley, James Lari, Yasmeen Larkana Lebanon Lighthouse Bazaar Lighthouse Centre Lighthouse Cinema literacy London Los Angeles, Calif. Love Line Bridge Lyari Macao Machar Colony mafias land Malik, Rehman Malik, Zain Manghopir Road Mawdudi, Abul A’la Mawdudi, Maulana McCartt, Steve Medellín megacities Memon, Sharfuddin “Bobby,” Memon Masjid Memons Mexico City migrants and refugees in Karachi in Pakistan reverse migration and Mirza, Iskander Mithidar Mohajirs Gutter Baghicha and Mohammad, Fawaz Mohammed, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Prophet monsoons Mountbatten, Louis MQM (Muttahida Qaumi Movement) Alibhai and Ashura fires and Gutter Baghicha and name change of MQM Haqiqi Mumbai murders Musharraf, Pervez Muslim League Muslim League National Guards Muslims Ahmadi extremist Memon migration to Pakistan Shia, see Shia Muslims; Shia processions Sufi Sunni, see Sunni Muslims Nader, Mohammad Nader, Shaheen Naim, Mufti Nairobi Napier, Robert Narindas, Makwana National Arms Navi Mumbai Naweed, Baseer nazims Nehru, Jawaharlal New Delhi New Karachi News International newspapers New York, N.Y.

Whole Earth Discipline: An Ecopragmatist Manifesto

by

Stewart Brand

Published 15 Mar 2009

His research strategy was to learn the relevant language and then live for months as a slum resident—in Rocinha (one of seven hundred favelas in Rio de Janeiro), in Kibera (a squatter city of 1 million outside Nairobi), in the Sanjay Gandhi Nagar neighborhood of Mumbai, and in Sultanbeyli, a now fully developed squatter city of 300,000 with a seven-story city hall, outside Istanbul. In each seemingly scary shantytown, Neuwirth found he could just walk in, ask around, find a place to rent, and start making friends. In Kibera he was the only white person for miles, and no one cared. He was frightened just once, when city police in Rio threatened him, apparently because he had neglected to bribe them.

Work: A History of How We Spend Our Time

by

James Suzman

Published 2 Sep 2020

Many of the most recent chapters in the story of Homo sapiens’ transformation into an urban species are written in the improvised, often chaotic freehand of crowded shanty towns which, like Havana, bloom on the fringes of the developing world’s cities and towns. Up to 1.6 billion people now live in slums and shanty towns. The largest – like Kibera in Kenya, Ciudad Neza outside Mexico City, Orangi Town in Pakistan and Mumbai’s Dharavi – have populations counted in millions and are in some ways cities-within-cities. Their spidery thoroughfares stretch for mile after unplanned mile and have grown so fast that the best local municipal authorities have been able to do is scurry frantically behind them, clipboards in hand, trying to calculate how much it would cost and whether it is possible to retrofit basic services like water, sewerage and electricity.

…

Index aardvarks here, here abiogenesis here Abrahamic religions here, here Académie des Sciences here acetogens here Acheulean hand-axes here, here, here Adam and Eve here, here adenosine triphosphate (ATP) here advertising here Africa, human expansion out of here agriculture and the calendar here, here catastrophes here and climate change here, here human transition to here inequality as consequence of here and investment here Natufians and here, here, here, here productivity gains here, here, here, here, here proportion employed in here spread of here and urbanisation here Akkadian Empire here Alexander the Great here American Federation of Labor here American Society of Mechanical Engineers here animal domestication here, here, here, here, here animal tracks here animal welfare here animals’ souls here anomie here anthrax here Anthropocene era here anti-trust laws here ants here, here, here Aquinas, Thomas here, here, here archery here Archimedes here, here, here Aristotle here, here, here, here Arkwright, Richard here armies, standing here Aronson, Ben here artificial intelligence here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here ass’s jawbone here asset ownership here AT&T here Athens, ancient here, here aurochs here Australian Aboriginals here, here, here, here, here Australopithecus here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here automation here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here Aztecs here baboons here Baka here BaMbuti here, here, here, here, here bank holidays here, here Bantu civilisations here barter here, here, here, here, here Batek here Bates, Dorothea here beer here, here, here, here, here bees here, here, here, here Belgian Congo here, here Bergen Work Addiction Scale here Biaka here billiards here biodiversity loss here, here, here birds of paradise here bison, European here Black-Connery 30-Hours Bill here Blombos Cave here, here Blurton-Jones, Nicholas here boa constrictors here boats, burning of here Bolling Allerød Interstadial here, here, here Boltzmann, Ludwig here boredom here, here Boucher de Crèvecœur de Perthes, Jacques here, here bovine pleuropneumonia here bowerbirds here, here brains here, here, here increase in size here and social networks here Breuil, Abbé here Broca’s area here Bryant and May matchgirls’ strike here bubonic plague here ‘bullshit jobs’ here butchery, ancient here Byron, Lord here Calico Acts here Cambrian explosion here cannibalism here caps, flat here carbon dioxide, atmospheric here, here cartels here Çatalhöyük here, here Cato institute here cattle domestication of here as investment here cave paintings, see rock and cave paintings census data here CEOs here, here, here, here, here, here cephalopods here cereals, high-yielding here Chauvet Cave painting here cheetahs here, here, here child labour here childbirth, deaths in here Childe, Vere Gordon here, here, here, here chimpanzees here, here, here, here, here, here, here China here, here, here, here, here, here Han dynasty here medical licensing examination here Qin dynasty here services sector here, here Shang dynasty here, here Song dynasty here value of public wealth here Chomsky, Noam here circumcision, universal here Ciudad Neza here clam shells here Clark, Colin here, here climate change here, here, here see also greenhouse gas emissions Clinton, Bill here clothing, and status here Club of Rome here, here coal here Coast Salish here, here cognitive threshold, humans cross here, here ‘collective consciousness’ here ‘collective unconscious’ here colonialism here commensalism here Communism, collapse of here Conrad, Joseph here consultancy firms here Cook, Captain James here cooking here, here, here coral reefs here Coriolis, Gaspard-Gustave here coronaviruses here corporate social responsibility here Cotrugli, Benedetto here cotton here, here, here credit and debt arrangements here Crick, Francis here crop rotation here cyanobacteria here, here Cyrus the Great here Darius the Great here Darwin, Charles here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here debt, personal and household here deer here, here demand-sharing here Denisovans here Descartes, René here, here, here, here DeVore, Irven here Dharavi here diamonds here, here diamphidia larvae here Dinka here division of labour here, here, here DNA here, here, here mitochondrial here dogs here, here, here, here, here, here domestication of here Lubbock’s pet poodle here Pavlov’s here wild here, here double-entry bookkeeping here dreaming here Dunbar, Robin here, here Durkheim, Emile here, here, here, here Dutch plough here dwellings drystone-walled here mammoth-bone here earth’s atmosphere, composition of here earth’s axis, shifts in alignment of here East India Company here, here ‘economic problem’ here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here economics ‘boom and bust’ here definitions of here, here formalists v. substantivists here fundamental conflict within here ‘trickle-down’ here ecosystem services here Edward III, King here efficiency movement here egalitarianism here, here, here, here, here, here egrets here Egypt, Roman here, here Egyptian Empire here einkorn here Einstein, Albert here elands here, here elderly, care of here, here, here, here elephants here, here, here, here, here, here energy-capture here, here, here Enlightenment here, here, here, here Enron here Enterprise Hydraulic Works here, here entropy here, here, here, here, here, here EU Working Time Directive here Euclid here eukaryotes here eusociality here, here evolution here, here and selfish traits here see also natural selection Facebook here, here Factory Acts here, here factory system here, here famines and food shortages here, here fertilisers here, here fighting, and social hierarchies here financial crisis (2007–8) here, here financial deregulation here fire, human mastery of here, here, here, here, here see also cooking fisheries here flightless birds here foot-and-mouth disease here Ford, Henry here, here, here, here, here fossil fuels here, here, here, here, here, here, here Fox, William here foxes here, here bat-eared here Franklin, Benjamin here, here, here, here, here, here, here free markets here, here, here free time (leisure time) here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here freeloaders here, here, here Freud, Sigmund here Frey, Carl, and Michael Osborne here funerary inscriptions here Galbraith, John Kenneth here, here Galileo here Gallup State of the Global Workplace report here Garrod, Dorothy here, here gazelle bones here, here genomic studies here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and domesticated dogs here geometry here gift giving here Gilgamesh here glacial periods here, here gladiators here Gladwell, Malcolm here globalisation here Göbekli Tepe here, here Gompers, Samuel here Google here Google AlphaGO here Gordon, Wendy here Gorilla Sign Language here gorillas here, here, here, here see also Koko Govett’s Leap here Graeber, David here, here granaries here graves here graveyards, Natufian here Great Decoupling here, here Great Depression here, here, here ‘great oxidation event’ here, here Great Zimbabwe here greenhouse gas emissions here, here see also climate change Greenlandic ice cores here grewia here Grimes, William here Gurirab, Thadeus here, here gut bacteria here Hadzabe here, here, here, here, here, here, here Harlan, Jack here harpoon-heads here Hasegawa, Toshikazu here Health and Safety Executive here health insurance here Heidegger, Martin here Hephaistos here Hero of Alexandria here Hesiod here hippopotamuses here Hitler, Adolf here hominins, evidence for use of fire here Homo antecessor here Homo erectus here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here Homo habilis here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here Homo heidelbergensis here, here, here, here, here Homo naledi here horses here, here wild here household wealth, median US here housing, improved here human resources here, here, here Humphrey, Caroline here Hunduism here hunter-gatherers, ‘complex’ here hyenas here, here, here, here, here immigration here Industrial Revolution here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here inequality here, here, here, here, here in ancient Rome here influenza here ‘informavores’ here injuries, work-related here Institute of Bankers here, here Institute of Management here intelligence here, here evolution of here interest here internal combustion engine here, here Inuit here, here, here, here Iroquois Confederacy here Ituri Forest here jackals here Japan here, here, here jealousy, see self-interest jewellery here, here, here, here, here Ju/’hoansi here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and animals’ souls here contrasted with ‘complex hunter-gatherers’ here contrasted with farming communities here, here, here creation mythologies here and ‘creatures of the city’ here and demand-sharing here, here egalitarianism here, here, here, here, here, here energy-capture rates here life expectancy here and mockery here village sizes here Jung, Carl Gustav here kacho-byo (‘manager’s disease’) here kangaroos here Karacadag here karo jisatsu here, here karoshi here, here Kathu Pan hand-axes here, here, here Kavango here Kellogg, John Harvey here Kellogg, Will here Kennedy, John F. here Keynes, John Maynard here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here Khoisan here, here, here Kibera here Kish here Koko here, here, here Kubaba, Queen here Kwakwaka’wakw here, here labour/debt relationships here labour theory of value here Lake Eyasi here Lake Hula here Lake Turkana here, here language arbitrary nature of here evolution of here Gossip and Grooming hypothesis here, here Grammaticalisation theory here processing here Single Step theory here langues de chat (cat’s tongues) here latifundia here le Blanc, Abbé Jean here leatherwork here Lee, Richard Borshay here, here, here, here, here leisure activities here leisure time, see free time Leopold II, King of the Belgians here, here Lévi-Strauss, Claude here, here, here, here Liebenberg, Louis here life expectancy here, here life on earth, evolution of here lignin here Limits to Growth, The here lions here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here literacy, see writing living standards, rising here Loki here, here London neighbourhoods here longhouses here Louis XIV, King of France here Louis XVI, King of France here Löwenmensch (Lion Man) sculpture here Lubbock, Sir John here, here Luddites here, here, here Luoyang (Chengzhou) here, here luxury goods here McKinsey and Co. here, here, here ‘malady of infinite aspirations’ here Malthus, Rev.

The Participation Revolution: How to Ride the Waves of Change in a Terrifyingly Turbulent World

by

Neil Gibb

Published 15 Feb 2018

“Nothing stops a bullet like a job,” says Father Boyle, neatly summing up Homeboys’ social mission. In September 2012, the United Nations Settlements Program announced the launch of “block by block”, an initiative designed to encourage people to re-imagine 300 run-down public spaces across the globe using Minecraft; its first area of focus being the Kibera slum in Nairobi, Kenya. This project is something that Lisa is particularly interested in. She was trained as a designer in Taipei but wasn’t able to find any meaningful work. The UN initiative has suggested a means for her and her friends to start to use Minecraft to develop and pitch ideas for urban renewal back in Taiwan – something her network of Minecraft co-creators had started to explore.

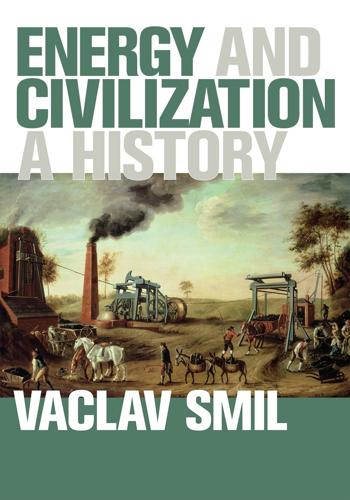

Energy and Civilization: A History

by

Vaclav Smil

Published 11 May 2017

Figure 6.16 Utilitarian but revolutionary: the Xerox Alto desk computer, released in 1973, was the first nearly complete embodiment of the basic features characteristic of all later PCs (Wikimedia photograph). Figure 6.17 A declining energy intensity of the GDP has been a universal feature of maturing economies. Based on data in Smil 2003 and USEIA 2015d. Figure 6.18 Kibera, one of Nairobi’s largest slums (Corbis). Kenya’s per capita use of modern energies averages about 20 GJ/year, but slum dwellers in Africa and Asia consume as little as 5 GJ/year, or less than 2% of the U.S. mean. Figure 6.19 A Shanghai high-rise apartment building with air conditioners for virtually every room (Corbis).

…

In 1950 only about 250 million people, or one-tenth of the global population, living in the world’s most affluent economies consumed more than 2 t of oil equivalent (84 GJ) a year per capita—yet they claimed 60% of the world’s primary energy (excluding traditional biomass). By the year 2000, such populations numbered nearly a quarter of all mankind and claimed nearly three quarters of all fossil fuels and electricity. In contrast, the poorest quarter of humanity used less than 5% of all commercial energies (fig. 6.18). Figure 6.18 Kibera, one of Nairobi’s largest slums (Corbis). Kenya’s per capita use of modern energies averages about 20 GJ/year, but slum dwellers in Africa and Asia consume as little as 5 GJ/year, or less than 2% of the U.S. mean. By 2015, thanks to China’s rapid economic growth, the share of the global population consuming more than 2 t of oil equivalents jumped to 40%, the greatest equalization advance in history.

Beautiful Solutions: A Toolbox for Liberation

by

Elandria Williams, Eli Feghali, Rachel Plattus

and

Nathan Schneider

Published 15 Dec 2024

LEARN MORE WEBSITE English-language website for Muungano wa Wanavijiji. muungano.net REPORT “Muungano Nguvu Yetu (Unity is Strength)” by Kate Lines and Jack Makau. (2017) iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/10807IIED.pdf DOCUMENTARY A Muungano Story by Al Jazeera. (2017) youtu.be/PEeOvWz9gxw SOLUTION INFORMAL SETTLEMENT NETWORKS People stand and talk in front of informal storefront units as others walk along a dirt road in the Kibera slum of Nairobi, Kenya. Photo by Ninaras (CC BY-SA 4.0). OVERVIEW Residents in informal urban settlements are forming organizations and networks to demand their human rights and improve their quality of life. THE INDUSTRIALIZATION OF CITIES IN THE GLOBAL South has spurred economic growth. But that growth often does not appear in the incomes of the poor and working-class people whose work makes industrialization possible.

Refuge: Transforming a Broken Refugee System

by

Alexander Betts

and

Paul Collier

Published 29 Mar 2017

Kenyan politicians are extremely reluctant to consider self-reliance or even increased socio-economic participation for refugees. But at times there have been glimmers of hope. For example, despite anti-refugee rhetoric from the Minister of Defence and the Minister of Home Affairs, a new group of elected Kenyan MPs, led by Kenneth Okoth, MP for Kibera, the Nairobi slum area, has begun to educate politicians about refugees and organize visits of MPs to Dadaab. Gradually there are small glimmers of improvement. For example, with support from the World Bank and UNHCR, Kenya has agreed to open a new camp in the Turkana Valley for some of its Sudanese refugees: Kalobeyei.