Our Dollar, Your Problem: An Insider’s View of Seven Turbulent Decades of Global Finance, and the Road Ahead

by Kenneth Rogoff · 27 Feb 2025 · 330pp · 127,791 words

social-support taxes, the Putin administration energized the Russian economy and initiated a period of healthy growth.14 Indeed, this is one occasion when the Laffer curve—which claims that cutting tax rates can boost growth so much that government tax revenue rises instead of falls—actually worked. According to the International

…

Krishnamurthy, Arvind, 212, 216 krona (Sweden), 123 krone (Denmark), 47 Krugman, Paul, 24, 122, 280, 281 Kuwait, 221 Kydland, Finn: “Rules Rather than Discretion,” 251 Laffer curve, 22 Lagarde, Christine (President, ECB), 231 Lance Rogoff, Natasha, 21–22, 24, 82, 83, 88, 89, 140, 248 Muppets in Moscow, 24;≈Russian Millennials Speak

Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events

by Robert J. Shiller · 14 Oct 2019 · 611pp · 130,419 words

Bitcoin Narratives 3 2 An Adventure in Consilience 12 3 Contagion, Constellations, and Confluence 18 4 Why Do Some Narratives Go Viral? 31 5 The Laffer Curve and Rubik’s Cube Go Viral 41 6 Diverse Evidence on the Virality of Economic Narratives 53 Part II The Foundations of Narrative Economics 7

…

News and Newspapers, 1850–2019 22 3.3 Frequency of Appearance of Four Economic Theories, 1940–2008 27 5.1 Frequency of Appearance of the Laffer Curve 43 10.1 Frequency of Appearance of Financial Panic, Business Confidence, and Consumer Confidence in Books, 1800–2008 116 10.2 Frequency of Appearance of

…

and history, and offering two examples of narratives that many readers will recognize: (1) the Bitcoin narrative, whose epidemic began in 2009, and (2) the Laffer curve narrative, which went viral mostly in the 1970s and 1980s. Part II provides a list of propositions to help guide our thinking about economic narratives

…

-Baptiste Michel (2013). The same patterns seem to apply to economic theories. In chapter 5 we consider the contagion of one of these narratives, the Laffer curve, a simple model of the relationship between tax rates and the amount of tax revenue collected. But let us first note briefly that these patterns

…

more pervasive narrative constellations, as we will see in the next chapter, which examines the narrative constellations associated with the famous (or infamous) Laffer curve. Chapter 5 The Laffer Curve and Rubik’s Cube Go Viral One of the toughest challenges in the study of narratives is predicting the all-important contagion rates and

…

how this economic narrative went viral provides further insight into how economic narratives lead to real-world results. The Laffer Curve and the Infamous Napkin The Laffer curve is a diagram famously used by economist Art Laffer at a dinner in 1974 to justify the government cutting taxes without cutting expenditures, which would

…

many voters, if the justification were valid. The narrative can be spotted by searching for the words “Laffer curve” (see Figure 5.1). There are two epidemic-like curves (not to be confused with the Laffer curve itself) in succession, the first rising until the early 1980s, the second rising after 2000, when it

…

became involved with another narrative justifying government deficits, associated with the words “modern monetary theory.” The Laffer curve looks like a simple diagram from an introductory economics textbook, with one important difference: it is very famous among the general public. The curve, which

…

work less, thus decreasing national income. The concept sounds like something that most people would find dull and boring. But, somehow, the Laffer curve went viral (Figure 5.1). The Laffer curve described in the narratives that are tallied in the figure owes much of its contagion to the fact that it was used

…

to justify major tax cuts for people with higher incomes. The Laffer curve’s contagion related to fundamental political changes associated with Ronald Reagan, who was elected US president in 1980, and with Margaret Thatcher, who became prime

…

minister in the United Kingdom a year earlier, in 1979. Both were conservatives whose campaigns promised to cut taxes. However, the Laffer curve narrative may not have played a role in France’s election of a socialist president, François Mitterrand, around the same time. An analysis of digitized

…

in France too, but not as much it did in the United States and the United Kingdom. FIGURE 5.1. Frequency of Appearance of the Laffer Curve The economic narrative of Arthur Laffer’s dinner napkin diagram about the effects of taxes on the economy shows a sharp epidemic around 1980 and

…

a secondary epidemic after 2000. Sources: Author’s calculations using data from ProQuest News & Newspapers 1950–2019, Books (Google Ngrams) 1950–2008, no smoothing. The Laffer curve narrative has a striking punch line that comes as a surprise but usually does not provoke any laughter. The narrative goes like this: What is

…

zero. For tax rates between 0% and 100%, some positive amount of tax revenue will be collected. When you connect the points, you have the Laffer curve. And here is the punch line: because the curve has the shape of an inverted U, there are always two tax rates that will collect

…

War I. But then the Mellon name began to fade (outside of Carnegie-Mellon University), and the narrative lost its momentum. The story of the Laffer curve did not go viral in 1974, the reputed year that Laffer first introduced it. Its contagion is explained by an anecdote that was published in

…

goes, Laffer drew his curve on a napkin at the restaurant table. Years later, after Wanniski’s death, his wife found a napkin with the Laffer curve among her late husband’s papers. The National Museum of American History now owns the napkin.9 Museum curator Peter Liebhold writes of this napkin

…

detail like a graph drawn on a napkin might have raised the contagion rate at the beginning of the narrative above the forgetting rate. The Laffer curve embodies a notion of economic efficiency easy enough for anyone to understand. Wanniski suggested, without any data, that we were on the inefficient side of

…

the Laffer curve. The drawing of the Laffer curve seemed to suggest that cutting taxes would produce a huge windfall in national income. To most quantitatively inclined people unfamiliar with economics, this

…

go viral, even though economists protested that the United States was not actually on the inefficient declining side of the Laffer curve.13 However, there may be some situations in which the Laffer curve offers important policy guidance, notably with taxes on corporate profits. A small country that lowers the corporate profits tax rate

…

may see companies moving their headquarters to that country, enough to raise that country’s corporate tax revenue.14 But an objective analysis of the Laffer curve did not lend itself to a punchy story that could have stifled the Laffer epidemic and the relating of it to personal income taxes. To

…

tell the story really well, one must set the scene at a fancy restaurant, with powerful Washington people and a napkin. In the end, the Laffer curve napkin story may have gone viral because of the sense of urgency and epiphany conveyed by the story: the idea was so striking, so important

…

brain, including visual-image processing regions.18 Rubik’s Cube, Corporate Raiders, and Other Parallel Epidemics Another fad appeared around the same time as the Laffer curve. Rubik’s Cube, invented in 1974 by Ernő Rubik, is a puzzle in the form of a cube-shaped stack of multicolored smaller cubes. As

…

people remember these details today, but they do remember that Rubik’s Cube is somehow impressive. Rubik’s Cube was bigger than the Laffer curve on ProQuest News & Newspapers, but smaller than the Laffer curve on Google Ngrams. Both show similar hump-shaped paths through time. Other narratives in the same constellation with the

…

Laffer curve sprang up around the same time. The terms leveraged buyouts and corporate raiders also went viral in the 1980s, often in admiring stories about companies

…

justification for aggressiveness and the pursuit of wealth, and the narratives that exploited the term are most certainly economically significant. The Laffer Curve, Supply-Side Economics, and Narrative Constellations After the Laffer curve epidemic, the Reagan administration (1981–89) reduced the top US federal income tax bracket from 70% to 28%. It also cut

…

US capital gains tax rate from 28% to 20% in 1981 (though it returned to 28% again in 1987 during the Reagan presidency). If the Laffer curve epidemic had even a minor effect on these changes, then it must have had a tremendous impact on output and prices. For these reasons, the

…

Laffer curve is well remembered to this day, but it was only one part of the narrative constellation now known as supply-side economics, which holds that

…

governments can increase economic growth by decreasing regulation and lowering taxes. The term supply-side economics went viral around the same time the Laffer curve did. The Laffer curve contributed to the impact of the many supply-side narratives because it was a particularly powerful narrative. It had good visual imagery in the

…

cuts for higher-income people might serve as an energizer, freeing the supposedly superior people to contribute to society. Celebrities, Quips, and Politics Though the Laffer curve epidemic may have played a role in the election of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, other narratives were surely influential, such as this quip by

…

about how onerous taxes are and that it isn’t just the speaker who is complaining. In short, it seems likely that narratives like the Laffer curve and other supply-side stories touched off an intense public mandate for tax cutting. We might argue, too, that the constellation of narratives about tax

…

encouraged entrepreneurial spirit and risk taking, and they brought about profound changes in the legal structure of the world’s advanced economies. These examples, the Laffer curve and Rubik’s Cube, are just two of a vast universe of narratives. We need to understand their organizing force. The storage points for all

…

of any of the books that Fisher spent years writing. They are in the same league with other colorful phrases such as irrational exuberance and Laffer curve. These words and their effects came from outside the economy, and they are therefore exogenous. Also, anniversaries of past events can resurrect economic narratives. Even

…

Allen’s insights into the Great Depression, John Maynard Keynes’s analysis of the narrative origins of World War II, the Bitcoin narrative, and the Laffer curve narrative. In this part of the book, we consider nine of the most important narrative constellations. These perennial narratives won’t completely go away, and

…

Monitor, October 24, 1951, p. 13. 22. Display ad, Los Angeles Times, July 29, 1991, p. A4. 23. Salganik et al., 2016. Chapter 5: The Laffer Curve and Rubik’s Cube Go Viral 1. Shiller, 1995. 2. Litman, 1983. 3. Jack Valenti, in a speech “Motion Pictures and Their Impact on Society

…

/blog/great-napkins-laffer. 10. Peter Liebhold, “O Say Can You See,” http://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/great-napkins-laffer. 11. Arthur B. Laffer, “The Laffer Curve: Past, Present and Future,” January 6, 2004, https://www.wiwi.uni-wuerzburg.de/fileadmin/12010500/user_upload/skripte/ss09/FiwiI/LafferCurve.pdf. 12. Paul Blustein

…

Neighbors: The Social and Cultural Context of European Witchcraft. New York: Penguin. Brill, Alex, and Kevin A. Hassett. 2007. “Revenue-Maximizing Corporate Income Taxes: The Laffer Curve in OECD Countries.” Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute. Brooks, Peter. 1992. Reading for the Plot: Design and Intention in Narrative. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

…

Paper 21703. Kydland, Finn E., and Edward C. Prescott. 1982. “Time to Build and Aggregate Fluctuations.” Econometrica 50(6):1345–70. Laffer, Arthur. 2004. “The Laffer Curve, Past, Present and Future.” Executive Summary Backgrounder No. 1765. The Heritage Foundation. Lahiri, Kajal, and J. George Wang. 2013. “Evaluating Probability Forecasts for GDP Declines

…

G. Galef Jr., eds., Social Learning: Psychological and Biological Perspectives, 51–74. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Mirowski, Philip. 1982. “What’s Wrong with the Laffer Curve?” Journal of Economic Issues 16(3):1815–28. Mitchell, Daniel J. B. 1985. “Wage Flexibility: Then and Now.” Industrial Relations 24(20):266–79. Mitchell

…

of Attention.” In Michael Posner, ed., Cognitive Neuroscience of Attention, 2nd ed., 47–56. New York: Guilford Press. Wanniski, Jude. 1978a. “Taxes, Revenues and the ‘Laffer Curve.’ ” Public Interest 38:3–16, https://www.nationalaffairs.com/storage/app/uploads/public/58e/1a4/c54/58e1a4c549207669125935.pdf. ________. 1978b. The Way the World Works: How

…

and, 129, 131, 135, 144; about Halley’s comet, 124; “Happy Birthday to You” and, 100; about housing market, 227; impact of, 29, 92–93; Laffer curve in, 47–48; names attached to, 94–95; as new context for old narratives, 271; not obvious from archival data, 86; opposing pairs of, 113

…

investors in stock market, 298–99; leading indicators approach and, 125; by mass of people not well-informed, 86 deficit spending: of Hoover administration, 188; Laffer curve and, 42 deflation: in depression of 1920–21, 111, 243–45, 246, 251, 253; gold standard and, 157, 161; in Great Depression, 253; wage cuts

…

of 1920–21 and, 249, 251; wage-price spiral and, 258–60, 261, 263, 264 Lacoste, Jean René, 62, 63 Laffer, Art, 42, 44–45 Laffer curve narrative, xviii, 24, 42–47, 48, 51, 52; exogenous effect on economy, 76; impact on output and prices, 48; in supply-side economics constellation, 47

…

, 176 symbols, reminding people of the narrative, 62 synonyms, different connotations of, 94–95 talk shows, economic narratives spread through, 21 Talleyrand, 172 tax cuts: Laffer curve and, 42, 48, 51; of Reagan administration, 48, 51; supply-side economics and, 48–52 taxes: on corporate profits, 45, 48; Henry George’s single

…

; about technological unemployment, 185; about wage-price spiral, 259–60 visual images: changed in mutated narrative, 108; memory aided by, 45, 46–47; power of Laffer curve narrative and, 45, 48 vivid mental images, jury members’ response to, 78 volatility, and epidemic quality of economic narratives, 5 Vosoughi, Soroush, 96–97 wage

Samuelson Friedman: The Battle Over the Free Market

by Nicholas Wapshott · 2 Aug 2021 · 453pp · 122,586 words

substantial increase in the long run public debt.”28 In 1992, in the fourteenth edition of his primer, Samuelson corrected that assumption, writing that the “Laffer-curve prediction that revenues would rise following the tax cuts has proven false.”29 Samuelson had made a deadly cameo appearance in the debate about the

…

virtues of the Laffer Curve when, in 1971, he gave a lecture at a conference in Chicago titled “Why They are Laughing at Laffer.” “In one of my writings I

…

scope of government. If some poor people get hurt, who said life is fair?”39 For those who fell in behind the logic of the Laffer Curve, tax cuts seemed to be a magic bullet that would solve the discrepancy between taxation and spending without inflicting too much pain. Friedman warned that

…

bring the Cold War to an end by outspending the Soviet Union on defense made balancing the budget impossible. Therefore, despite the promise of the Laffer Curve and “trickle-down economics,” in which the taxes saved by the rich were claimed to eventually benefit those further down the economic food chain, Reagan

…

supply-side economics include Robert Mundell (October 24, 1932–), professor of economics at Columbia University and Nobel Prize winner for economics, 1999; Arthur Laffer, whose Laffer Curve contends that there is a sweet spot at which a reduction in taxation can deliver higher revenues; and Jude Thaddeus Wanniski (June 17, 1936–August

…

Policy Advisory Board, 1981–1989, dubbed “the Father of Supply-Side Economics.” 25.Laffer on the napkin story, https://www.heritage.org/taxes/report/the-laffer-curve-past-present-and-future. 26.Stein, Presidential Economics, p. 239. 27.Ibid., p. 245. 28.Samuelson, Economics, 7th ed. (1967), p. 343. 29.Samuelson and

…

15th edition (1995), 172 18th edition (2004), 172–73 Capitalism and Freedom commended, 49 on inflation and unemployment, 120 Keynesian economics in, 7, 18–19 Laffer Curve, 206 neoclassical synthesis, 21 Phillips Curve, 115 revisions, 8, 20, 24, 49, 74 on Soviet economy, 218, 219–21 Economic Stimulus Act of 2008, 277

…

, 304 Krugman, Paul, 285, 322 Kuhn, Thomas S., 94, 319 Kuznets, Simon, 29–30, 33, 71, 308 Laffer, Arthur lack of PhD, 206–7, 332 Laffer Curve and taxes, 205, 206, 208, 209, 332 supply-side economics, 205, 206–7, 250, 332 Lawson, Nigel, 245, 247, 337 Lehman Brothers, 275 Leigh-Pemberton

…

on, 32, 79, 85, 155–56, 208, 290 Friedman on tax cuts, 44, 155–56, 208, 209, 211, 252 inflation as hidden tax, 77–78 Laffer Curve and, 205, 206, 208, 209, 332 negative income tax plan, 143, 173, 292 payroll withholding tax, 32–33 progressive income tax, 47 Samuelson on, 85

Wealth and Poverty: A New Edition for the Twenty-First Century

by George Gilder · 30 Apr 1981 · 590pp · 153,208 words

the Reagan era are Alan Reynolds, who is still outwitting all the demand siders in his work Income and Wealth, the irrepressible Arthur Laffer of Laffer curve fame (lower marginal tax rates tend to yield more revenues), and the indefatigably savvy and inspirational Steve Forbes. Most erstwhile supply-side allies, though, are

…

vindication has in any way abated the mockery of his ideas. Most American critics of supply-side economics seem to believe they can disprove the Laffer curve by number-chopping a couple of idiosyncratic episodes. President Clinton raised income tax rates to 39 percent and balanced the budget. Eisenhower maintained a top

…

and directly the converging crises of inflation, innovation, and growth. First, and most important, despite all its mostly irrelevant flaws, was the politically galvanic Laffer curve. The Laffer curve indicates that there are normally two different tax rates that will bring in a particular amount of revenue. For example, a zero rate will bring

…

evidence... not a bit of data”—in this case—no persuasive testimony to indicate that the United States has reached the upper portions of the Laffer curve; that American tax rates are at a point where tax reductions can enlarge revenues. With real tax rates on gains from wealth rising well above

…

tax will bring in no revenue at all. It can choke off commerce without leaving tracks. Rates and revenues at the higher portions of the Laffer curve are inversely proportional; the higher the rates, the less the revenue. Under these circumstances it is irrelevant to allege that the United States bears low

…

any other country. Because Britain and Sweden have very high top income-tax rates that yield little revenue, they have been even further up the Laffer curve in some parts of their tax system than is the United States. But both European countries impose higher rates on the middle classes and lower

…

formation of new companies, but the cuts would increase revenues, as Laffer maintains. France and Italy, on the other hand, could move decisively down the Laffer curve by lowering their phenomenally onerous social-security taxes. These taxes, three-quarters of which are nominally paid by the employer in France, and nine-tenths

…

breakdown of families, and a vast movement into the underground economy.33 Altogether these trends indicate that the U.S. economy is high on the Laffer curve and that cuts in tax rates would cause dramatic shifts from sheltered to taxable activity while also improving productivity and growth. In 1978, as it

…

in the state’s accounts. The only economist who predicted such results was Arthur Laffer. For liberals concerned with the distribution of income, moreover, the Laffer curve offers a promise as seductive as any of the Keynesian strictures against austerity and thrift. Regressive taxes help the poor! It has become increasingly obvious

…

more far-reaching. From it has been developed a new general theory of inflation. Like the Laffer curve, the new theory found its fullest expression outside of the circles of academic economics. Also like the Laffer curve—at least in Wanniski’s hands—the new theory referred as much to the long historic record

…

, eds., The Economics of the Tax Revolt, pp. 110–113; Charles W. Kadlec and Arthur B. Laffer, “The Jarvis-Gann Proposal: An Application of the Laffer Curve,” in ibid., pp. 118–122. 35 According to a Library of Congress study of projections of three econometric models (Wharton, Chase, and DRI), passage of

…

, Larry Kuznets, Simon Kuznets curve Kwakiutl L labor, capitalization of elasticity of Labor Department labor market, equal rights agencies and restrictions labor unions Laffer, Arthur Laffer curve and Lafferite economics Laissez-faire land. See real estate land grant agricultural colleges Lasch, Christopher lasers Latin America Latvia Lauder, Estée Law Enforcement Assistance Administration

The Economists' Hour: How the False Prophets of Free Markets Fractured Our Society

by Binyamin Appelbaum · 4 Sep 2019 · 614pp · 174,226 words

. To illustrate the point, Laffer grabbed a cocktail napkin and sketched a curve that looked like the nose of an airplane. Wanniski dubbed it the “Laffer curve” and made it so famous that the Smithsonian museum now displays a replica inscribed by Laffer. The curve illustrated the claim that high tax rates

…

the central claim of supply-side economics, but supply-siders did not regard 100 percent revenue recovery as a universal property of tax cuts. The Laffer curve went up and it went down — some cuts would pay for themselves, others not. And the claim was generally more complicated than “the government will

…

, ref1; and safety rules, ref1, ref2; George Stigler on, ref1; Margaret Thatcher on, ref1; Paul Volcker on, ref1 Laffer, Arthur: forecasting model of, ref1, ref2; Laffer curve, ref1, ref2, ref3; and Proposition ref1, ref2; and Ronald Reagan, ref1, ref2; and supply-side economics, ref1, ref2, ref3, ref4; on taxation, ref1, ref2, ref3

Reaganland: America's Right Turn 1976-1980

by Rick Perlstein · 17 Aug 2020

in the next issue of the Public Interest Wanniski published a head-spinningly ambitious defense of Kemp-Roth’s foundational theory: “The idea behind the ‘Laffer curve’ is no doubt as old as civilization,” he claimed, “but unfortunately politicians have always had trouble grasping it.” He described instances throughout history when tax

…

, October 25, 1977; “The Tax Relief Act of 1977,” First Monday, August 1977. next issue of the Public Interest Jude Wanniski, “Taxes, Revenues, and the ‘Laffer Curve,’ ” Public Interest, Winter 1978. single phone call Stahl, Right Moves, 101; “typical review” is 103; Friedman, 104. Gardner Ackley Collins, More, 177. Franco Modigliani Collins

10% Less Democracy: Why You Should Trust Elites a Little More and the Masses a Little Less

by Garett Jones · 4 Feb 2020 · 303pp · 75,192 words

voter involvement would improve or worsen government outcomes, that means I need to separate out measures of voter involvement from measures of government outcomes. A Laffer Curve for Democracy? In the 1980s, economist Art Laffer—then at the University of Southern California, now a professional economic consultant—drew a picture on a

…

. In economics, any time we see a relationship that can be summed up as an inverted U, we’re pretty likely to call it a Laffer curve–type relationship, in homage to Art Laffer. Fortunately, economists are well equipped to compare costs against benefits, but it means discarding the linear—or at

…

costs—costs that are too often ignored. My contention is that the world’s rich democracies are overall on the wrong side of the democracy Laffer curve, as Figure 1.1 suggests. Practical, nonutopian reforms exist that would: • Make a country slightly less democratic • Likely create substantial long-run economic benefits • Have

…

little or no cost in resources • Be more likely to increase than to diminish widely embraced human rights. FIGURE 1.1. The Democracy Laffer Curve. Just as important—for matters of practicality, if nothing else—countries that enacted these reforms would still look and feel and truly be democratic. After

…

tell which factors seemed more important and which were mere statistical illusions. One of the findings he trumpeted was that there appeared to be a Laffer curve relationship between democracy and long-run economic growth rates. At low levels of democracy, a bit more democracy predicted noticeably higher growth rates. Yet after

…

, future growth will probably be retarded by the political liberalizations that have already occurred in places such as Chile, Korea, and Taiwan.”¹⁷ If Barro’s Laffer curve theory of democracy were widely accepted in academic circles, my case would be halfway proven already. Beyond some point, there would be a clear democracy

…

in exchange for a 300% raise? Well, you might not, but a lot of your neighbors probably would. As it turns out, Barro’s early Laffer curve results for democracy don’t turn up in most of the more recent studies. More sophisticated methods—ones that can compare the same country before

…

independence, which offers the best evidence I know of on the question of whether we’re on the wrong side of the democracy-versus-bureaucracy Laffer curve. But the next largest body of statistical evidence comes from research on the judiciary. The United States in particular, with its fifty states and a

…

the story. It didn’t start with a “D” or an “R.” It probably started with an “E.” Electricity and Telecom Regulation: Top of the Laffer Curve? Government regulators are another area where elections and appointments are two key alternatives. Partly because so many economists and lawyers are deeply involved in these

…

, you’re close to the optimum regardless of your choice. That’s what it looks like when you’re near the top of the democracy Laffer curve: mostly sky. Captured Regulators: A Reason for Worry One risk of appointed regulators is that they’ll end up caving to the demands of industry

…

to be humiliated twice.²⁶ A quadratic equation can take the form of an upside-down U, an inverted parabola, shaped just like the Laffer curve. Recall that a Laffer curve shows that if you start the tax rate off at zero and increase it from there, you’ll generate more tax revenue for a

…

while, but eventually you’ll reach the peak. If the tax rate rises above that level—the top of the Laffer curve—you’ll push so many people into the black market or early retirement or accounting games that the government will start losing revenue. The benefits

…

and costs of widespread citizen voting might be another Laffer curve type of relationship. If voting is purely a universal human right, and not at all a means to an end of good governance, then restricting

…

net benefits of expanding the franchise beyond the highly educated are probably very high, but we should try to find the top of the suffrage Laffer curve, the peak of the body politic’s parabola. We’d be foolish to take Heinlein’s suggestion for voting reform literally, but we should certainly

…

. Hamilton was no defender of 100% pure democracy. In his own way, different from my own, he was looking for the top of the democracy Laffer curve to balance the benefits of citizen influence against the benefits of keeping power from the people, keeping institutions independent of the immediate demands of voters

…

: on central banks and financial crises, 57 Kydland, Finn: on real business cycle (RBC) theory, 55 labor market regulation, 34–35, 74, 75, 76, 100 Laffer curves, 19–22, 65, 81, 117 La Porta, Rafael: on judicial independence and economic freedom, 73–76 Latin American debt crisis, 133 Lawson, Robert: on economic

Keynes Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics

by Nicholas Wapshott · 10 Oct 2011 · 494pp · 132,975 words

would reap the maximum revenue. He illustrated his reasoning by drawing a bell curve on a napkin, showing where the sweet spot might lie. The “Laffer curve” instantly became the hastily drawn device used by economists around Reagan to convince others that tax cuts would boost revenues. Sharply cutting income taxes, the

…

on “demand-led” growth spurred by Keynesian public spending. Laffer was graceful enough to point out that, despite his name being attached to it, the Laffer curve was not his invention and that others, notably Keynes, had beaten him to the punch. “Nor should the argument seem strange that taxation may be

…

time Reagan left office in January 1989 the jobless figure was at 5.3 percent.65 But that was not the whole story. Despite the Laffer curve, the income tax cuts took a sharp toll on revenue. In 1982, Reagan, alarmed by the fast-increasing budget deficit, rescinded various tax breaks on

…

, The Democrats’ Dilemma: Walter F. Mondale and the Liberal Legacy (Columbia University Press, New York, 1995), p. 371. 65 All figures from Arthur Laffer, The Laffer Curve: Past, Present and Future, Executive Summary Backgrounder No. 1765 (Heritage Foundation, Washington, D.C., June 2004). 66 Jerry Tempalski, “Revenue Effects of Major Tax Bills

…

., 2010). Lachmann, Ludwig M. Expectations and the Meaning of Institutions: Essays in Economics, ed. Don Lavoie (Psychology Press, Hove, U.K., 1994). Laffer, Arthur. The Laffer Curve: Past, Present and Future. Executive Summary Backgrounder No. 1765 (Heritage Foundation, Washington, D.C., June 2004). Lawson, Nigel. The View from Number 11 (Bantam Press

…

, 187, 247, 268 Labour Party, 33–34, 38, 58–59, 83, 86, 203, 259, 266, 292 Lachmann, Ludwig M., 109, 122 Laffer, Arthur, 262, 264 Laffer curve, 262, 264 laissez-faire economics, 25, 32, 34–37, 62–64, 150, 162, 163, 222, 243, 316n Laski, Harold, 24 law: —natural, 35, 43–44

Licence to be Bad

by Jonathan Aldred · 5 Jun 2019 · 453pp · 111,010 words

not remember doing so, he apparently grabbed a napkin and drew a curve on it, representing the relationship between tax rates and revenues.fn2 The ‘Laffer curve’ was born and, with it, the idea of ‘trickle down economics’. The key implication which impressed Rumsfeld and Cheney was that, just in the way

…

that the cuts had negligible impact on GDP – and certainly not enough to outweigh the negative effect of the cuts on tax revenues. But the Laffer curve did remind economists that a ‘revenue-maximizing top tax rate’ somewhere between 0 per cent and 100 per cent must exist. Finding the magic number

…

the flaws in bell-curve thinking: Taleb, N. (2010). The Black Swan. London, Penguin. 9. YOU DESERVE WHAT YOU GET On the rise of the Laffer curve and, more generally, the political/cultural shift towards markets in the US: Rodgers, D. (2011). Age of Fracture. Harvard, Harvard University Press. There are several

…

in every country in 2002. 32 Quoted in L. Mcquaig and N. Brooks (2013), The Trouble with Billionaires (London: Oneworld), 204. 33 Laffer, A., The Laffer Curve: Past, Present, and Future, Heritage Foundation Report, 1 June 2004. 34 Quoted in Rodgers, 73. 35 http://www.politico.com/story/2017/05/15/donald

…

Tarski, Alfred, 74–5 taxation and Baumol’s cost disease, 94 and demand for positional goods, 239–41 as good thing, 231, 241–2, 243 Laffer curve, 232–3, 234 new doctrine of since 1970s, 232–4 property rights as interdependent with, 235–6 public resistance to tax rises, 94, 239, 241

Termites of the State: Why Complexity Leads to Inequality

by Vito Tanzi · 28 Dec 2017

tax rates led to an almost revolutionary change in thinking that brought the supply-side revolution. A politically significant part of that revolution was the Laffer curve, a presumably important economic relationship that was assumed to exist between tax rates and effort and output. That curve would be used by conservative economists

…

mentioned, a popular aspect of the supply-side revolution that would attract a lot of popular and political attention was the “Laffer curve” (see Tanzi, 2014a, for a recent evaluation). The Laffer curve became an article of faith for conservative politicians in the United States, and created strong pressures on governments to reduce tax

…

solve many economic problems, to one that supposed tax cuts would be the solution to many problems. The combination of the assumed impact of the Laffer curve on economic incentives and the concerns about the impact of globalization on taxes on capital incomes set the stage for a frontal attack on the

…

the article. It may have been a coincidence, but the time when the article was published was the same when other developments, such as the Laffer curve and tax theories that started arguing that capital incomes should not be taxed, or should be taxed at lower rates than income from labor, were

…

Termites of the State at present, plus, in many states, the locally imposed income taxes). The common thinking, reinforced by the continuing popularity of the “Laffer curve” has been that these are the income levels where substitution effects must be most pronounced, leading to significant reductions in work incentive and efforts. The

…

individuals exposed to the highest marginal tax rate might be in the part of the Laffer curve where effort and income fall, because of reactions to the high rates. For these people leisure definitely becomes relatively cheaper than work, even though, given

…

it was mainly the marginal tax rates that had come under attack by conservative economists and by those who believed in the relevance of the Laffer curve. There had been less talk about the architecture of the income tax. The 1986 fundamental tax reform introduced by the Reagan administration had sharply reduced

…

(profits, capital gains, dividends, “carried trade,” etc.) could be justified as being in the workers’ longer run interests. This argument complemented that made by the Laffer curve, that lower rates created incentives for citizens to work more. The taxes on incomes from capital sources were progressively reduced, especially in the 1990s, to

…

Institute in the United States, and the Institute of Economic Affairs, in England – also played a role. Important technical tools of that “revolution” were the Laffer curve, rational expectation, and the Ricardian Equivalence hypothesis. Some widely read popular books that Why Worry about Income Distribution? 395 transmitted to the wider public the

…

to reduce structural obstacles, which was often interpreted as a need to reduce taxes, economic regulations, and the power of labor unions. (g) The aforementioned Laffer curve, the largely political device that attracted the attention of economists and politicians to the role that high marginal tax rates might play in reducing incentives

…

to work and to invest, and in reducing the potential growth of economies. The popularity of the Laffer curve, a concept that was easy to understand and to use by noneconomists and by conservative politicians, would lead to the sharp reductions in marginal tax

…

, Dollars, Euros, and Debt: How We Got into the Fiscal Crisis, and How We Get Out of It (London: Palgrave Macmillan). Bibliography 423 2014a, “The Laffer Curve Muddle” in A Handbook of Alternative Theories of Public Economics, edited by Francesco Forte, Ram Mudambi, and Pitro Maria Navarro (Cheltenham: Eduard Elgar), pp. 104

…

Klein, Lawrence, 42 Klein, Naomi, 29 Kornai, Janos, 26 KPMG International, 376 Krugman, Paul, 240–41, 342–43 Kuznets, Simon, 3 Lady Gaga, 351–52 Laffer Curve, 74–76, 363, 373–74, 377, 379, 394–95, 397 Laissez faire, 15–21 abandonment of, 43 criticism of, 3 in Eastern Europe, 35 Index

The Finance Curse: How Global Finance Is Making Us All Poorer

by Nicholas Shaxson · 10 Oct 2018 · 482pp · 149,351 words

Who Needs the Fed?: What Taylor Swift, Uber, and Robots Tell Us About Money, Credit, and Why We Should Abolish America's Central Bank

by John Tamny · 30 Apr 2016 · 268pp · 74,724 words

Money and Government: The Past and Future of Economics

by Robert Skidelsky · 13 Nov 2018

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History

by Kurt Andersen · 14 Sep 2020 · 486pp · 150,849 words

An Extraordinary Time: The End of the Postwar Boom and the Return of the Ordinary Economy

by Marc Levinson · 31 Jul 2016 · 409pp · 118,448 words

Who Owns the Future?

by Jaron Lanier · 6 May 2013 · 510pp · 120,048 words

The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay

by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman · 14 Oct 2019 · 232pp · 70,361 words

Markets, State, and People: Economics for Public Policy

by Diane Coyle · 14 Jan 2020 · 384pp · 108,414 words

Free Money for All: A Basic Income Guarantee Solution for the Twenty-First Century

by Mark Walker · 29 Nov 2015

The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty

by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson · 23 Sep 2019 · 809pp · 237,921 words

Age of Greed: The Triumph of Finance and the Decline of America, 1970 to the Present

by Jeff Madrick · 11 Jun 2012 · 840pp · 202,245 words

Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy

by Daron Acemoğlu and James A. Robinson · 28 Sep 2001

The Age of Entitlement: America Since the Sixties

by Christopher Caldwell · 21 Jan 2020 · 450pp · 113,173 words

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

Cryptoassets: The Innovative Investor's Guide to Bitcoin and Beyond: The Innovative Investor's Guide to Bitcoin and Beyond

by Chris Burniske and Jack Tatar · 19 Oct 2017 · 416pp · 106,532 words

A Generation of Sociopaths: How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America

by Bruce Cannon Gibney · 7 Mar 2017 · 526pp · 160,601 words

How to Speak Money: What the Money People Say--And What It Really Means

by John Lanchester · 5 Oct 2014 · 261pp · 86,905 words

Broken Markets: How High Frequency Trading and Predatory Practices on Wall Street Are Destroying Investor Confidence and Your Portfolio

by Sal Arnuk and Joseph Saluzzi · 21 May 2012 · 318pp · 87,570 words

Two Nations, Indivisible: A History of Inequality in America: A History of Inequality in America

by Jamie Bronstein · 29 Oct 2016 · 332pp · 89,668 words

Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science (Fully Revised and Updated)

by Charles Wheelan · 18 Apr 2010 · 386pp · 122,595 words

Abundance

by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson · 18 Mar 2025 · 227pp · 84,566 words

The Economic Singularity: Artificial Intelligence and the Death of Capitalism

by Calum Chace · 17 Jul 2016 · 477pp · 75,408 words

An Empire of Wealth: Rise of American Economy Power 1607-2000

by John Steele Gordon · 12 Oct 2009 · 519pp · 148,131 words

When to Rob a Bank: ...And 131 More Warped Suggestions and Well-Intended Rants

by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner · 4 May 2015 · 306pp · 85,836 words

Nine Crises: Fifty Years of Covering the British Economy From Devaluation to Brexit

by William Keegan · 24 Jan 2019 · 309pp · 85,584 words

Debt: The First 5,000 Years

by David Graeber · 1 Jan 2010 · 725pp · 221,514 words

Nomads: The Wanderers Who Shaped Our World

by Anthony Sattin · 25 May 2022 · 412pp · 121,164 words

Basic Economics

by Thomas Sowell · 1 Jan 2000 · 850pp · 254,117 words

Arguing With Zombies: Economics, Politics, and the Fight for a Better Future

by Paul Krugman · 28 Jan 2020 · 446pp · 117,660 words

The Winner-Take-All Society: Why the Few at the Top Get So Much More Than the Rest of Us

by Robert H. Frank, Philip J. Cook · 2 May 2011

Hawai'I Becalmed: Economic Lessons of the 1990s

by Christopher Grandy · 30 Sep 2002 · 145pp · 43,599 words

Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World

by Adam Tooze · 31 Jul 2018 · 1,066pp · 273,703 words

The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution

by Francis Fukuyama · 11 Apr 2011 · 740pp · 217,139 words

Traffic: Why We Drive the Way We Do (And What It Says About Us)

by Tom Vanderbilt · 28 Jul 2008 · 512pp · 165,704 words

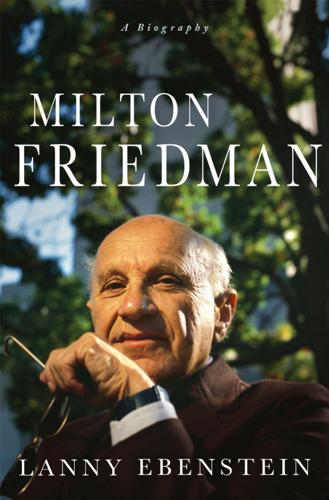

Milton Friedman: A Biography

by Lanny Ebenstein · 23 Jan 2007 · 298pp · 95,668 words

The omnivore's dilemma: a natural history of four meals

by Michael Pollan · 15 Dec 2006 · 467pp · 503 words

Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea

by Mark Blyth · 24 Apr 2013 · 576pp · 105,655 words

My Start-Up Life: What A

by Ben Casnocha and Marc Benioff · 7 May 2007 · 207pp · 63,071 words

The Social Animal: The Hidden Sources of Love, Character, and Achievement

by David Brooks · 8 Mar 2011 · 487pp · 151,810 words

Rentier Capitalism: Who Owns the Economy, and Who Pays for It?

by Brett Christophers · 17 Nov 2020 · 614pp · 168,545 words

One Up on Wall Street

by Peter Lynch · 11 May 2012

Economic Gangsters: Corruption, Violence, and the Poverty of Nations

by Raymond Fisman and Edward Miguel · 14 Apr 2008

The Once and Future Liberal: After Identity Politics

by Mark Lilla · 14 Aug 2017 · 91pp · 24,469 words

The Centrist Manifesto

by Charles Wheelan · 18 Apr 2013 · 104pp · 30,990 words