Blood River: A Journey to Africa's Broken Heart

by

Tim Butcher

Published 2 Jul 2007

In the Victorian era, Stanley was the world's best-known journalist, famous for the scoop of the century - tracking down the Scottish explorer, David Livingstone, in November 1871. The soundbite he came up with was as glib and memorable as any a modern spin doctor could conjure. Stanley's `Dr Livingstone, I presume,' greeting remains so dominant that it has overshadowed his much greater and more significant achievement. It came on his next epic trip to Africa between 1874 and 1877, when he solved the continent's last great geographical mystery by mapping the Congo River. Commissioned jointly by the Telegraph and an American newspaper, The New York Herald, he hacked his way through a swathe of territory never before visited by a white man, crossing the Congo River basin and proving that the continent's previously impenetrable hinterland could be opened up by steamboats on a single, huge river.

…

The RGS had many friends in Zanzibar and they would have sought to block any freelance attempt to track their man. Stanley was right to be suspicious of some of the stuffier attitudes within the RGS. After finding Livingstone in November 1871 at the small settlement of Ujiji on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika, where the 'Doctor Livingstone, I presume?' greeting scene was played out, the two men spent four months together. But Stanley could not persuade Livingstone to return to Zanzibar. So he returned by himself, carrying a bundle of thirty letters and a journal written by Livingstone as proof that he had found the explorer. This was not enough to silence the sniping from many senior members of the RGS.

…

A Royal Navy officer, Commander Verney Lovett Cameron, had been the first European to explore the river. Cameron was one of the great `what if' figures of African exploration, an adventurer of no less ambition than Stanley, but who somehow never quite staked his own place in the public's imagination. He never came up with a soundbite as memorable as `Dr Livingstone, I presume?' Cameron actually beat Stanley to this spot by two years. He, too, had heard tales from the Arab slavers about an immense river somewhere out there to the west. And he, too, was willing to trek through the bush for week after week to check if it were true. But, unlike Stanley, he failed to make the river descent.

Crossing the Heart of Africa: An Odyssey of Love and Adventure

by

Julian Smith

Published 7 Dec 2010

At the lakeshore Stanley pushed through crowds of people and saw a pale, gray-bearded man sitting under a mango tree. He briefly considered running over and embracing him but then decided to walk over deliberately. He took off his hat and uttered one of the most famous lines in journalism: “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” Except he probably didn’t. As Tim Jeal, Stanley’s biographer, writes, the explorer probably thought up his immortal phrase months later. Livingstone didn’t record it in his account of the meeting, and Stanley tore the relevant pages out of his own journal. Either way, the words stuck and helped make Stanley a household name once he returned home.

…

International Journal of African Historical Studies 7, no. 1 (1974): 69–84. Paice, Edward. Lost Lion of Empire: The Life of Cape-to-Cairo Grogan. London: HarperCollins, 2001. Pakenham, Thomas. The Scramble for Africa, 1876–1912. New York: Random House, 1991. “People of Africa’s Past: Ewart Grogan.” Travel Africa, no. 11 (Spring 2000). Pettitt, Clare. Dr. Livingstone, I presume?: Missionaries, Journalists, Explorers, and Empire. London: Profile, 2007. Roberts, Chalmers. “A Wonderful Feat of Adventure.” World’s Work, January 1901. Rocco, Fiametta. The Miraculous Fever-tree: Malaria, Medicine and the Cure That Changed the World. New York: HarperCollins, 2004. Royal Geographical Society.

The Phantom Atlas: The Greatest Myths, Lies and Blunders on Maps

by

Edward Brooke-Hitching

Published 3 Nov 2016

It was a gruelling, three-year mission into the interior of Africa, in which the pair suffered all manner of tropical diseases: several times Burton fell gravely ill and Speke went temporarily blind – he also lost his hearing for a time when a beetle crawled into his ear and he tried to fish it out with a knife. When Burton became too ill to move, Speke continued solo and identified Lake Victoria as the true source in 1858 (much to the disbelief and protest of Burton). The pair feuded for years until in 1874 Henry Morton Stanley (deliverer of the famous and probably invented line ‘Doctor Livingstone I presume?’) circumnavigated the lake and confirmed Speke’s findings. This finally laid the Moon Mountains myth to rest, but the discussion was now as to which mountains served as its basis. In 1940, the writer G. W. B. Huntingford made the case for the range to be identified with Mount Kilimanjaro, but was ridiculed by his peers, though Sir Harry Johnston had made the same argument in 1911, as did Dr Gervase Mathew in 1963.

The Pentagon's Brain: An Uncensored History of DARPA, America's Top-Secret Military Research Agency

by

Annie Jacobsen

Published 14 Sep 2015

U.S. reconnaissance aircraft patrolled the skies over the South Atlantic. Ships carrying antiaircraft rockets were at the ready, in the unforeseen event of Soviet sabotage. The commander of Task Force 88 sent his final coded message to the ARPA office at the Pentagon, a prearranged indication that the operation was a go at his end. “Doctor Livingstone, I presume?” the commander stated clearly into a ship-to-shore radio microphone. The first test would take place on August 27, 1958. Although no one had a name for it at the time, Operation Argus was the world’s first test of an electromagnetic pulse bomb, or EMP. Halfway across the world, in Switzerland, a remarkable series of events was taking place.

…

Christofilos: His Contributions to Physics, 1–15. 12 “responsible people”: IDA-ARPA Study No. 1, 19. 13 “The group has”: IDA-ARPA Study No. 1, 19. 14 Brazilian Anomaly: Operation Argus 1958, 19. 15 so many moving parts: Ibid., 22-26. 16 missile trajectory: Ibid., 48; list of shipboard tests and remarks, 56. 17 “Doctor Livingstone, I presume?”: Ibid., 34. 18 watched fireworks: Childs, 525. 19 “The President has asked”: Ibid., 521. 20 detection facilities: DARPA: 50 Years of Bridging the Gap, 58. 21 Wissmer examined Lawrence: Childs, 526. 22 had Harold Brown participate: Supplement 5 to “Extended Chronology of Significant Events Leading Up to Disarmament,” Joint Secretariat, Joint Chiefs of Staff, April 21, 1961, (unpaginated), York Papers, Geisel. 23 “I could never”: Childs, 527. 24 Christofilos effect did occur: Argus 1958, 65–68; Interview with Doug Beason, June 2014; “Report to the Commission to Assess the Threat to the United States from Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) Attack,” 161. 25 The telegram marked: Edward Teller, telegram to General Starbird, “Thoughts in Connection to the Test Moratorium,” August 29, 1958, LANL.

Never Enough: The Neuroscience and Experience of Addiction

by

Judith Grisel

Published 15 Feb 2019

A firsthand description suggests what that role might be. The explorer and missionary David Livingstone was on a trip to Africa when he was attacked by a lion. (He is familiar to many by the understated greeting he received from Henry Morton Stanley when Stanley finally located the missing Scot: “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”) Livingstone survived the mauling, and his account dramatically illustrates the role of endorphins in the body. The lion, he wrote, “caught me by the shoulder as he sprang, and we both came to the ground together. Growling horribly close to my ear, it shook me as a terrier dog does a rat.

Heaven's Command (Pax Britannica)

by

Jan Morris

Published 22 Dec 2010

There he lay sick, penniless and exhausted, lost to the world, utterly out of touch with Europe, his mission a failure, his whereabouts one of the mysteries of the age: and there on November 10, 1871, Henry Stanley of the New York Herald, advancing into his camp beneath the Stars and Stripes, with his caravan of porters loaded with bales of food, tents, expensive equipment and ingenious accessories to African travel, walked through the wondering crowd of Arabs, took off his hat, and uttered one of the epic texts of the Victorian age, as sacred to the faithful as it was comic to the irreverent: ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’ ‘“Yes”, he said with a kind smile, lifting his cap slightly.’ 5 Stanley was a Welshman. Born John Rowlands at Denbigh in 1841, he had run away from the workhouse at St Asaph, and shipped as a cabin-boy for the United States. There he was adopted by a kindly cotton-broker, Mr Stanley of New Orleans.

…

As for Stanley himself, ‘what would I not have given for a bit of friendly wilderness, where, unseen, I might vent my joy in some mad feat, such as idiotically biting my hand, turning a somersault, or slashing at trees, in order to allay those exciting feelings, that were well-nigh uncontrollable’. He did control them, however, not wishing to ‘detract from the dignity of a white man appearing in such extraordinary circumstances’, and so gave his folk-phrase to the language—‘Dr Livingstone, I presume’. Livingstone, it seemed, did not in the least wish to be rescued. Now that fresh supplies were at hand, he wanted only to complete his task. Stanley had other duties to perform, and taking Livingstone’s precious journals with him, and bidding an affectionate and respectful goodbye to the old man, in March 1872 he left for the coast to sublimate his scoop—which very rightly made him celebrated throughout the world.

Them: Adventures With Extremists

by

Jon Ronson

Published 1 Jan 2001

Everywhere I go, I have policemen sitting with me. Now I have a journalist. And he wants to record me, to use my words against me in future days.’ ‘Of course,’ I said, ‘David Livingstone had a journalist along with him too.’ ‘Well,’ replied Dr Paisley, ‘he had a journalist who caught up on him. Mr Dr-Livingstone-I-Presume. And Stanley, as a journalist, took all the glory. As if Livingstone was lost!’ I felt that the best course of action, at that point, was to deride journalism. So I mentioned that Stanley lived to regret uttering those famous words, because the music-hall comedians of the time mocked him for it.

The Battery: How Portable Power Sparked a Technological Revolution

by

Henry Schlesinger

Published 16 Mar 2010

Labor-saving household products that included everything from the first electric iron and electric fan to the sewing machine and toaster were all patented and often publicized. Never mind that many of the products were years, even decades away from practical use, they showed what was possible with the power of electricity. The battery also found some unusual uses. It was said that the African explorer and journalist Henry Morton Stanley (of “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” fame) carried a small battery during his 1870s African expedition that gave tribal leaders a shock when they shook hands in order to instill in them a sense of his superiority and power. When the trick received criticism, one defender wrote, “It is beyond understanding why fault should be found with this harmless and efficient method of teaching a truth.”

Content Provider: Selected Short Prose Pieces, 2011–2016

by

Stewart Lee

Published 1 Aug 2016

And is Gove’s view on the UKIP parents an honest one, born of heartfelt personal experience, or is it, given UKIP’s growing power, politically expedient to confirm to their supporters that they could make fit parents? Deep in a British Library vault, I found a set of late-1880s letters exchanged between the then prime minister, Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, the 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, and the explorer Sir Henry Morton Stanley. Stanley is famous for his catchphrase “Dr Livingstone, I presume”, which finally rang true after decades of irrelevance when, quite by chance, he encountered a physician of that name at Lake Tanganyika in 1871. The letters shed some light on both the possible inspiration for Edgar Rice Burroughs’s classic 1912 novel, Tarzan of the Apes, and on the current UKIP fostering controversy.

Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives

by

Siddharth Kara

Published 30 Jan 2023

He pitched The Herald on the nineteenth-century equivalent of a reality-TV search for Livingstone. He would send dispatches from the field and either find Livingstone or evidence of his death. Stanley eventually found Livingstone sick and weary at Ujiji in November 1871. According to his apocryphal account, he uttered the famous words, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” Stanley spent four months with Livingstone and came to see him as the father he never had. Stanley felt inspired to finish Livingstone’s work by discovering the source of the Nile. On October 17, 1876, he saw the Lualaba River for the first time, at the opposite end of the Congo River system that Diego Cão discovered almost four centuries earlier.

Globish: How the English Language Became the World's Language

by

Robert McCrum

Published 24 May 2010

Stanley, a naturalized American of illegitimate Welsh origin, to search out and interview the famous missionary-explorer, one of Britain’s greatest heroes, who had not been heard from since 1866. After an epic march across ‘Fatal Africa’, Stanley tracked the shy Scots missionary in November 1871 to the shores of Lake Tanganyika where, on first meeting, he uttered the much parodied salute, ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume.’ Thereafter, the threadbare Glaswegian became the kind of homespun imperial celebrity the Victorian media craved. Livingstone, in contrast to Stanley’s crude, and sometimes violent, racism, wanted to transform Africa’s prospects through a combination of trade and the Gospel. His actual achievements were limited, but in the longer term his mission and his myth had lasting consequences.

Cataloging the World: Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age

by

Alex Wright

Published 6 Jun 2014

On February 26, 1885, representatives from fourteen European nations concluded a marathon three-month-long conference in Berlin, during which they attempted to sort out their competing claims in Africa. At the time, 80 percent of Africa remained unclaimed by the colonial powers, but the so-called Dark Continent had started to attract considerable interest all over Europe, thanks in part to the sensational reports of explorers like Henry Morton Stanley (of “Dr. Livingston, I presume?” fame). For some Europeans, Africa seemed like a fantastical world, a primordial wilderness promising mystery and adventure. For others, it looked like one big gold mine, both literally and figuratively. For the 50 T he D rea m o f the L ab y rinth increasingly industrialized European powers, the temptations would prove irresistible.

Step by Step the Life in My Journeys

by

Simon Reeve

Published 15 Aug 2019

‘You can have four or five hundred people and only two toilets for all of them.’ I was silent for a while after that. The DRC often left me numb. You can read about a place as much as you like, but only by going and seeing can you truly appreciate both the beauty and the tragedy. The DRC had both in epic quantities. It was explorer Henry Morton Stanley, he of ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume’ fame, who really helped begin the subjugation of the people of the Congo basin. Under the colonial rule of King Leopold II of Belgium 5–10 million people died in what is now the DRC. Some historians argue it is the hidden holocaust. Independence from Belgium was no salvation. The country set sail on its own with just a couple of dozen graduates in the entire country and not a single person with a university degree in law, medicine or engineering.

To the Edges of the Earth: 1909, the Race for the Three Poles, and the Climax of the Age of Exploration

by

Edward J. Larson

Published 13 Mar 2018

Also entering by way of Zanzibar, but no longer up to the rigors of such travel, Livingstone was sick, disoriented, and low on supplies somewhere in the eastern Congo River basin by 1870. Henry Morton Stanley, a Welsh-born journalist sent by the New York Herald to find him, reached the explorer in 1871. “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” Stanley reported asking in an affected British understatement. “Yes, that is my name” came the reply that echoed around the globe.36 Hooked on the fame and money it brought him, Stanley returned to the region once more for the New York Herald and twice for Belgian King Leopold II, who wanted to claim and colonize the Congo.

Empire: What Ruling the World Did to the British

by

Jeremy Paxman

Published 6 Oct 2011

James Gordon Bennett of the New York Herald recognized the commercial potential of a world scoop and Henry Morton Stanley’s marathon journey to discover Livingstone’s fate was the result. Stanley’s celebrated greeting, when he eventually found Livingstone at Ujiji, in what is now western Tanzania – ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’ – guaranteed the immortality of both men. Afterwards, they travelled together for a while, and then Stanley left Livingstone to continue his search for the source of the Nile. One year later, Livingstone was still in Africa, but by now he was a very sick man able to travel only if carried in a litter by his porters.

The Looting Machine: Warlords, Oligarchs, Corporations, Smugglers, and the Theft of Africa's Wealth

by

Tom Burgis

Published 24 Mar 2015

I reached Livingstone House, an angular and imposing twenty-two-story building that was the city’s tallest when it was constructed under white rule and named after the Scottish missionary pioneer immortalized in Western imaginings of Africa through his encounter in 1871 with the British explorer Stanley (‘Dr. Livingstone, I presume?’). Today the skyscraper houses, among other things, Zimbabwe’s ineffectual anticorruption commission. Its proprietors were the same outfit that has snapped up another office complex across town and a hotel that is popular for weddings in the suburbs – the Queensway Group.46 The lobby at Livingstone House was only slightly less grand than that of Luanda One, the Queensway Group’s Angolan skyscraper.

Extreme Economies: Survival, Failure, Future – Lessons From the World’s Limits

by

Richard Davies

Published 4 Sep 2019

History echoes strongly in Kinshasa, with the roots of economic distrust and self-reliance down to the legacy of two men: a foreign colonial founder, and a home-grown dictator. THE KING, AND THE MESSIAH A ROYAL LIAR Kinshasa has lies and deception in its bedrock. The city was founded by Henry Morton Stanley, a journalist and explorer born in Wales, most famous for his reaction – ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’ – when he found the Scottish explorer, long presumed dead, close to the modern border of Tanzania in 1871. Stanley returned to central Africa in 1874, publishing an account of his travels that sold well across Europe. Unable to finance a third trip in Britain he nonetheless set off again in 1879, this time funded by the International African Association (IAA), a company bankrolled and controlled by King Leopold II of Belgium.

Posh Boys: How English Public Schools Ruin Britain

by

Robert Verkaik

Published 14 Apr 2018

In 1885, Emin Pasha, the governor whom Gordon had personally appointed to office, withdrew further south, to Wadelai near Lake Albert, but was in imminent danger of capture by the Mahdi’s superior forces. The following year, Britain assembled the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, led by Henry Morton Stanley (of ‘Dr Livingstone I presume’ fame) and set about the rescue of Pasha. Major Edmund Musgrave Barttelot was one of eight public school-educated officers and gentlemen explorers who volunteered for the mission. As Stanley’s second in command, he was in charge of the rear column together with an Anglo-Irish gentleman explorer, James Sligo Jameson, an ancestor of the Jameson whiskey family.

Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World

by

Niall Ferguson

Published 1 Jan 2002

I would have run to him, only I was a coward in the presence of such a mob – would have embraced him, only, he being an Englishman, I did not know how he would receive me; so I did what cowardice and false pride suggested was the best thing – walked deliberately up to him, took off my hat, and said: ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume.’ It took an American to take British understatement to its historic zenith. When Stanley’s story broke, it dominated the front pages of the English-speaking world. Yet this was more than just a scoop. It was also a symbolic meeting between two generations: the Evangelical generation that had dreamt of a moral transfiguration of Africa and a new, hard-nosed generation with more worldly priorities.

A Man for All Markets

by

Edward O. Thorp

Published 15 Nov 2016

Over the next couple of years I read books including Gulliver’s Travels, Treasure Island, and Stanley and Livingstone in Africa. When, after an eight-month arduous and dangerous search, Stanley found his quarry, the only European known to be in Central Africa, I thrilled to his incredible understatement, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume,” and I discussed the splendor of the Victoria Falls on the Zambezi River with my father, who assured me (correctly) that they far surpassed our own Niagara Falls. Gulliver’s Travels was a special favorite, with its tiny Lilliputians, giant Brobdingnagians, talking horses, and finally the mysterious Laputa, a flying island in the sky supported by magnetic forces.

The Wizard of Menlo Park: How Thomas Alva Edison Invented the Modern World

by

Randall E. Stross

Published 13 Mar 2007

When he tried to burnish his public image with exaggerated claims of progress in his laboratory, for example, he demonstrated a hunger for credit unknown in his earliest tinkering. The mature Edison, post-fame, is most appealing whenever he returned to acting spontaneously, without weighing what action would serve to enhance his public image. One occasion when Edison cast off the expectations of others in his middle age was when he met Henry Stanley, of “Dr. Livingstone, I presume” fame, and Stanley’s wife, who had come to visit him at his laboratory. Edison provided a demonstration of the phonograph, which Stanley had never heard before. Stanley asked, in a low voice and slow cadence, “Mr. Edison, if it were possible for you to hear the voice of any man whose name is known in the history of the world, whose voice would you prefer to hear?”

The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism

by

Joyce Appleby

Published 22 Dec 2009

A Civil War veteran, a foreign correspondent, and an amateur geographer, Stanley in 1871 accepted an assignment from the New York Herald to find the missing Livingstone. Knowing that Stanley had fought on both sides in the Civil War gives some idea of his versatility. His quest through central Africa took six months, but he had succeeded by the end of the year, when he did in fact greet the missing missionary with the famous salutation “Dr. Livingstone, I presume.” Stanley and Livingstone became household names during the next few years. They stimulated the imagination, the curiosity, and the ambition of Europeans who had come to think of the entire globe as their domain. During the next six years Stanley continued to explore Africa, circumnavigating Lake Victoria.

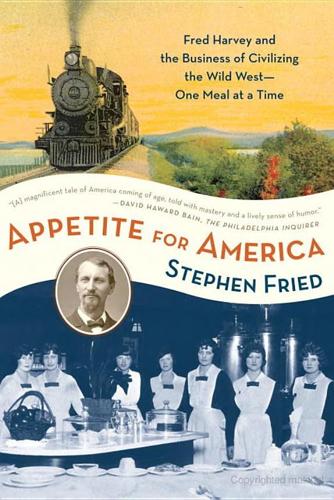

Appetite for America: Fred Harvey and the Business of Civilizing the Wild West--One Meal at a Time

by

Stephen Fried

Published 23 Mar 2010

Louis Democrat: The article appeared in the April 16, 1867, edition. The reporter was Henry Stanley, who went on to his own renown as the journalist later sent to the jungles of Africa to find the lost Scottish explorer David Livingstone; it was he who spoke—or at least claimed that he spoke—the immortal words “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” $4,485.22: Harvey, Nov. 28, 1868, entry, 1867 datebook, DHC. “physical disability”: July 1864 draft registry for St. Joseph, Mo., line 14, National Archives and Record Center. “Started out this morning”: Harvey, Jan. 7, 1869, entry, 1869 datebook, DHC. “equal parts spirits”: Harvey, undated entries, 1879–1880 datebook, DHC.

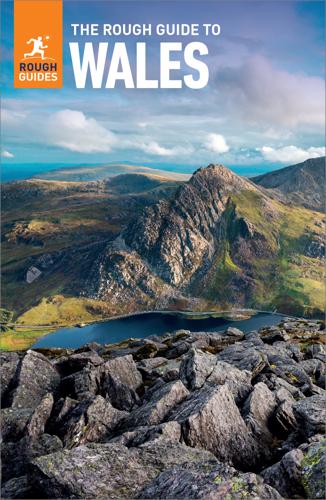

The Rough Guide to Wales

by

Rough Guides

Published 14 Oct 2024

. ££ Denbigh and around The castle ruins dominating the Vale of Clwyd eight miles north of Ruthin herald DENBIGH (Dinbych), in medieval times a fortified hill town, which still tumbles down towards its old centre where the Wednesday market takes place. High Street is lined by a pleasing array of colonnaded medieval buildings which, thankfully, haven’t been over-restored, helping retain the feel of a working town. In front of the County Hall (built in 1572, and now the library) stands a new statue of Henry Morton “Dr Livingstone, I presume?” Stanley, born near the castle in 1841. From High Street, Broomhill Lane (with various artistic installations) climbs through the crumbling Burgess Gate, the town’s former northern entry, to the vast grassy ward of ruined Denbigh Castle. Denbigh Castle Castle Lane, LL16 3NB • April–Oct daily 10am–5pm; Nov–March Sat-Sun 10am–4pm • Charge; CADW • http://cadw.gov.wales/visit/places-to-visit/denbigh-castle For a long time, the River Clwyd formed the border between England and Wales, guarded here by a now-vanished Welsh castle, which probably gave the town its name, meaning “small fort”.

Africa: A Biography of the Continent

by

John Reader

Published 5 Nov 1998

His public was becoming anxious, so the New York Herald dispatched the journalist Henry Morton Stanley (who had emigrated from Britain to the United States at the age of seventeen) to Africa with the simplest of directives but the most challenging of assignments: ‘Find Livingstone.’13 Stanley found the doctor at Ujiji, on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, in November 1871, and secured himself an entry in every dictionary of quotations with the greeting: ‘Doctor Livingstone, I presume.’ Their meeting reinforced popular interest in Africa, while Stanley's report that Livingstone, already unwell, intended to continue his explorations of the Great Lakes prompted the Royal Geographical Society to dispatch a relief column, under the leadership of Verney Lovett Cameron, a naval officer who had sailed with Britain's anti-slavery squadron.

The Rough Guide to Egypt (Rough Guide to...)

by

Dan Richardson

and

Daniel Jacobs

Published 1 Feb 2013

Guests included Lawrence of Arabia, who stayed here at the beginning of World War One, and at the end of the war, Australian soldiers celebrated with a massive pillow fight on the hotel’s grand staircase. Lord Carnarvon, who financed the excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb, died in his room here in 1923, supposedly a victim of the pharaoh’s curse, and other guests included American journalist Henry Morton Stanley, of “Dr Livingstone, I presume” fame. In 1941, Orde Wingate, the eccentric military genius who later led the British commandos known as Chindits against the Japanese in Burma, attempted suicide in his room here by stabbing himself in the neck with a Bowie knife. Luckily for Britain’s southeast Asian war effort, he failed.

The Pursuit of Power: Europe, 1815-1914

by

Richard J. Evans

Published 31 Aug 2016

In 1859 he sailed to New Orleans, jumped ship, and found a job with a rich trader called Henry Stanley, who eventually adopted him. Henry Morton Stanley fought on both sides in the American Civil War, then became a journalist, which led to his engagement by the legendary editor of the New York Herald, James Gordon Bennett Jr. (1841–1918), to find the missing British missionary David Livingstone (1813–73). ‘Dr. Livingstone, I presume?’ – Stanley’s reputed greeting to the missionary when he finally caught up with him in 1871 in a remote part of Africa near Lake Tanganyika – entered legend as a classic example of cool understatement. In 1874 the Herald commissioned Stanley to trace the course of the river Congo from its source to the sea; starting out with a company of 356, he eventually arrived at the mouth of the river with only 114 left, none of them European.

Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, From the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First

by

Frank Trentmann

Published 1 Dec 2015

Once imperial tastes had formed, people were unlikely to respond to pleas to ‘buy local’, as the Colonial Office learnt the hard way in the inter-war years.136 In the era of the ‘new imperialism’ in the 1880s–’90s, imperial symbols and slogans gained ground in advertising. The craze for African explorer H. M. Stanley (‘Dr Livingstone, I presume’) was an advertiser’s dream. Stanley appeared in ads for soap and Bovril, and sipped tea with the Emin Pasha in his tent at Kavalli, on the southern shore of Lake Albert. ‘Stanley: “Well, Emin, old fellow, this Cup of the United Kingdom Tea Company’s Tea makes us forget all our troubles.” Emin: “So it does, my boy.”’

Principles of Corporate Finance

by

Richard A. Brealey

,

Stewart C. Myers

and

Franklin Allen

Published 15 Feb 2014

Could you apply the parity formula to a call and put with different exercise prices? 5. Put–call parity There is another strategy involving calls and borrowing or lending that gives the same payoffs as the strategy described in Problem 3. What is the alternative strategy? 6. Option payoffs Dr. Livingstone I. Presume holds £600,000 in East African gold stocks. Bullish as he is on gold mining, he requires absolute assurance that at least £500,000 will be available in six months to fund an expedition. Describe two ways for Dr. Presume to achieve this goal. There is an active market for puts and calls on East African gold stocks, and the rate of interest is 6% per year. 7.

Great Britain

by

David Else

and

Fionn Davenport

Published 2 Jan 2007

Return to beginning of chapter BLANTYRE pop 17,300 One of Scotland’s most famous sons is David Livingstone, the epitome of the Victorian missionary-explorer, who opened up central Africa to European influence in the 19th century. After disappearing for several years during an expedition to the source of the Nile, he was famously ‘found’ by American newspaper reporter Henry Stanley in 1871, with the immortal words ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’. Visitors with an interest in Africa shouldn’t miss the absorbing David Livingstone Centre (NTS; 01698-823140; 165 Station Rd; adult/child £5/4; 10am-5pm Mon-Sat, 12.30-5pm Sun Easter-Dec), set in Livingstone’s birthplace, which tells the story of his life. In 30 years it’s estimated he travelled 29,000 miles through central Africa, mostly on foot – the sheer tenacity of the man was incredible.