The Shifts and the Shocks: What We've Learned--And Have Still to Learn--From the Financial Crisis

by Martin Wolf · 24 Nov 2015 · 524pp · 143,993 words

Martin Wolf THE SHIFTS AND THE SHOCKS What we’ve learned – and have still to learn – from the financial crisis Contents List of Figures Preface: Why I

…

BOOK 1. Hyman P. Minsky, Inflation, Recession and Economic Policy (Brighton: Wheatsheaf, 1982), p. xi. 2. Martin Wolf, Fixing Global Finance (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press and Yale University Press, 2008 and 2010). 3. Martin Wolf, Why Globalization Works (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004), ch. 13. 4. The ‘great

…

Institute, ‘Sovereign Wealth Fund Rankings’, http://www.swfinstitute.org/fund-rankings/. 9. The role of the global imbalances in the crisis was the theme of Martin Wolf, Fixing Global Finance (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008 and 2010), especially ch. 8 of the revised edition. See also Òscar Jordà, Moritz

…

the crisis, see Paulson, On the Brink, and Alistair Darling, Back from the Brink: 1,000 Days at Number 11 (London: Atlantic Books, 2011). 5. Martin Wolf, ‘Session 3 (Round Table) Financial Globalisation, Growth and Asset Prices’, in International Symposium: Globalisation, Inflation and Monetary Policy, Banque de France, March 2008, http://www

…

for $2 a Share’, Financial Times, 16 March 2008. 12. Ben White, ‘Buoyant Bear Stearns Shrugs Off Subprime Woes’, Financial Times, 16 March 2007. 13. Martin Wolf, ‘The Rescue of Bear Stearns Marks Liberalisation’s Limit’, Financial Times, 25 March 2008. 14. Paulson, On the Brink, p. 170, and Krishna Guha, Chris

…

2013, http://www.voxeu.org/article/when-time-austerity, provides a compelling analysis of the high cost of fiscal austerity in the UK. See also Martin Wolf, ‘How Austerity has Failed’, New York Review of Books, 11 July 2013, http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2013/jul/11/how-austerity-has-failed

…

research, McKinsey Global Institute, January 2012, http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/mgi/research/financial_markets/uneven_progress_on_the_path_to_growth, p. 3. 60. Martin Wolf, ‘Mind the Gap: Perils of Forecasting Output’, Financial Times, 9 December 2011. 61. Irving Fisher, ‘The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions’, Econometrica (1933). 62

…

’, 26–27 June 2010, http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/2010/to-communique.html. 68. Paul Samuelson, Economics, first edition (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1948). 69. Martin Wolf, ‘The Toxic Legacy of the Greek Crisis’, Financial Times, 18 June 2013, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/b31dd248-d785-11e2-a26a-00144feab7de.html

…

, ‘The Euro: Love it or Leave it?’, 4 May 2010, http://www.voxeu.org/article/eurozone-breakup-would-trigger-mother-all-financial-crises. See also Martin Wolf, ‘A Permanent Precedent’, Financial Times, 17 May 2012, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/614df5de-9ffe-11e1-94ba-00144feabdc0.html. 21. The term ‘Ordoliberalism

…

de Grauwe, ‘The Governance of a Fragile Eurozone’, CEPS Working Documents, Economic Policy, 4 May 2011, http://www.ceps.eu/book/governance-fragile-Eurozone, and Martin Wolf, ‘Be Bold Mario, Put Out that Fire’, Financial Times, 25 October 2011, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/bd60ab78-fe6e-11e0-bac4-00144feabdc0.html

…

.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1410072, p. 248. See also Raguram Rajan, ‘Bankers’ Pay is Deeply Flawed’, Financial Times, 9 January 2008, and Martin Wolf, ‘Why and How should we Regulate Pay in the Financial Sector?’, in Turner et al., The Future of Finance, ch. 9. 58. Adair Turner, The

…

Chief Stays Bullish on Buy-outs’ Financial Times, 9 July 2007, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/80e2987a-2e50-11dc-821c-0000779fd2ac.html. 4. Martin Wolf, Fixing Global Finance (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press and Yale University Press, 2010), especially ch. 8. 5. Herbert Stein, ‘Herb Stein’s Unfamiliar

…

, founded under President William Jefferson Clinton, is distinct from the Council of Economic Advisers, founded in 1946 under President Harry Truman. 7. Lawrence Summers and Martin Wolf, ‘A Conversation on New Economic Thinking’, Bretton Woods Conference, Institute for New Economic Thinking, 8 April 2011, http://ineteconomics.org/video/bretton-woods/larry-summers

…

-and-martin-wolf-new-economic-thinking. 8. Ben Bernanke, Chairman of the Federal Reserve, also stressed the intellectual debt of central bankers to the journalist, Walter Bagehot, in

…

(New York: W. W. Norton, 2012). For a sceptical discussion of the argument that the UK’s pre-crisis level of output was unsustainable, see Martin Wolf, ‘How the Financial Crisis Changed Our World’, 2013 Wincott Memorial Lecture, http://www.wincott.co.uk/lectures/2013.html. 5. International Monetary Fund, ‘The Dog

…

Taylor, ‘When is the Time for Austerity?’, 20 July 2013, Vox, http://www.voxeu.org/article/when-time-austerity. 22. These arguments were developed in Martin Wolf, ‘How Austerity has Failed’, The New York Review of Books, vol. LX, no. 12, 11 July–4 August 2013, pp. 20–22, http://www.nybooks

…

Report 2012/2013, 23 June 2013, http://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2013e.htm. 27. See on this Martin Wolf, ‘The Role of Fiscal Deficits in De-leveraging’, 25 July 2012, http://blogs.ft.com/martin-wolf-exchange/2012/07/25/getting-out-of-debt-by-adding-debt. 28. Robert Kuttner, Debtors’ Prison: The

…

, http://www.social-europe.eu/2014/03/german-constitutional-court. 10. O’Rourke and Taylor, ‘Cross of Euros’, p. 176. 11. This section draws from Martin Wolf, ‘Why the Baltic States are no Model’, Financial Times, 30 April 2013, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/090bd38e-b0c7-11e2-80f9-00144feabdc0.html

…

. 12. Olivier Blanchard, ‘Lessons from Latvia’, 11 June 2013, http://blog-imfdirect.imf.org/2012/06/11/lessons-from-latvia. 13. This section draws from Martin Wolf, ‘The German Model is not for Export’, Financial Times, 7 May 2013, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/aacd1be0-b637-11e2-93ba-00144feabdc0.html

…

-Driven Austerity in the Eurozone and its Implications’, 21 February 2013, http://www.voxeu.org/article/panic-driven-austerity-Eurozone-and-its-implications. See also Martin Wolf, ‘Be Bold, Mario, Put Out that Fire’, Financial Times, 25 October 2011, www.ft.com. 17. Alex Barker ‘Marathon Talks Seal EU Banking Union’, Financial

…

and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2013). 30. Mervyn King, ‘Banking from Bagehot to Basel, and Back Again’, pp. 16–17. 31. This is drawn from Martin Wolf, ‘Failing Elites Threaten our Future’, Financial Times, 14 January 2014, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/cfc1eb1c-76d8-11e3-807e-00144feabdc0.html. References Abiad

…

Be the New Normal’, 15 December 2013, Financial Times. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/87cb15ea-5d1a-11e3-a558-00144feabdc0.html. Summers, Lawrence and Martin Wolf. ‘A Conversation on New Economic Thinking’, Bretton Woods Conference, Institute for New Economic Thinking, 8 April 2011. http://ineteconomics.org/video/bretton-woods/larry-summers

…

-and-martin-wolf-new-economic-thinking. Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and the Markets (London: Penguin, 2004). Taleb, Nassim Nicholas

…

/cms/s/0/614df5de-9ffe-11e1-94ba-00144feabdc0.html. Wolf, Martin. ‘The Role of Fiscal Deficits in Deleveraging’, 25 July 2012. http://blogs.ft.com/martin-wolf-exchange/2012/07/25/getting-out-of-debt-by-adding-debt. Wolf, Martin. ‘Afterword: How the Financial Crises Have Changed the World’, in Robert C

…

Avenue, Parktown North, Gauteng 2193, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England www.penguin.com First published 2014 Copyright © Martin Wolf, 2014 The moral right of the author has been asserted Cover design by Keenan All rights reserved Typeset by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes ISBN: 978

The Economic Consequences of Mr Trump: What the Trade War Means for the World

by Philip Coggan · 1 Jul 2025 · 96pp · 36,083 words

, cbo.gov/publication/61181 13 budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2025/5/19/house-reconciliation-bill-budget-economic-and-distributional-effects-may-19-2025 14 Martin Wolf, ‘The old global economic order is dead’, Financial Times, 6 May 2025, ft.com/content/49e38ee8-f37e-47da-8ee4-1631175d2224 15 Ana Swanson, ‘“Totally silly

India's Long Road

by Vijay Joshi · 21 Feb 2017

Sullivan, Kamakshya Trivedi, Maya Tudor, Ravi Vaidya, John Vickers, David Vines, Bhaskar Vira, Arvind Virmani, Jessica Wallack, Michael Walton, Andrew Whitehead, John Williamson, Dominic Wilson, Martin Wolf, Ngaire Woods, Simon Wren-Lewis, and Yogendra Yadav. I have also learned a great deal from my participation in the highly stimulating India Policy Forum

The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival

by Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan · 8 Aug 2020 · 438pp · 84,256 words

for Business Taxation, Working Paper 2017/1. Reproduced with permission. 2In an article entitled ‘Rethink the purpose of the corporation’ (Financial Times, 12 December 2018), Martin Wolf criticises the mantra of shareholder value maximisation, affirming that in the cases of highly leveraged banking the Anglo American model of corporate governance does not

I.O.U.: Why Everyone Owes Everyone and No One Can Pay

by John Lanchester · 14 Dec 2009 · 322pp · 77,341 words

print journalists did speak up in public about the risks building up and the vulnerability of the global financial system. Larry Elliott in The Guardian, Martin Wolf and Gillian Tett in the Financial Times, and even the often overly gung ho Economist all warned about the dangers—and had the satisfaction denied

…

Peston at the BBC—Flanders and Peston have high-quality blogs, in addition to their old-media work; Philip Coggan, John Kay, Gillian Tett, and Martin Wolf at the Financial Times; Larry Elliott at The Guardian; and although as a Nobel Prize winner he is too grand to count, Paul Krugman at

Grave New World: The End of Globalization, the Return of History

by Stephen D. King · 22 May 2017 · 354pp · 92,470 words

such volumes are listed in the bibliography. Those who have offered me advice and inspiration in equal measure on the economic aspects of globalization include Martin Wolf, Gideon Rachman, George Magnus, Shamik Dhar, David Bloom, Simon Williams, Murat Ulgen, Robin Down and Simon Wells. I also owe a debt of gratitude to

Modernising Money: Why Our Monetary System Is Broken and How It Can Be Fixed

by Andrew Jackson (economist) and Ben Dyson (economist) · 15 Nov 2012 · 363pp · 107,817 words

, such concerns have been sidelined. Yet these concerns are becoming more widespread that ever before, with even the chief economics commentator for the Financial Times, Martin Wolf, expressing the view that: “It is the normal monetary system, in which the ‘printing’ of money is delegated to commercial banks, that needs defending. This

The Classical School

by Callum Williams · 19 May 2020 · 288pp · 89,781 words

.9 Historians have noted that under the watchful eye of Colbert there was a clear change in French government policy from what had come before. Martin Wolfe, for instance, finds little evidence of high import tariffs in Renaissance France. By the 17th century that had decisively changed. “The famous mercantilist principle of

Left Behind

by Paul Collier · 6 Aug 2024 · 299pp · 92,766 words

theory: a theory of choice under radical uncertainty’, in Behavior and Brain Sciences, 46, 1–26. 10 The sense of crisis is well captured by Martin Wolf in The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism (2023). The stand-out instance of overconfidence is the Truss–Kwarteng faith in the Panglossian omniscience of financial markets

Broken Markets: A User's Guide to the Post-Finance Economy

by Kevin Mellyn · 18 Jun 2012 · 183pp · 17,571 words

they owe money. The ants and grasshoppers are, in fact, dependent on each other. The formal term global imbalance—a topic that sage economic commentator Martin Wolf often returns to in the pages of the Financial Times as a core threat to global prosperity—is largely one of too much saving in

Money: The True Story of a Made-Up Thing

by Jacob Goldstein · 14 Aug 2020 · 199pp · 64,272 words

The Logic of Life: The Rational Economics of an Irrational World

by Tim Harford · 1 Jan 2008 · 250pp · 88,762 words

99%: Mass Impoverishment and How We Can End It

by Mark Thomas · 7 Aug 2019 · 286pp · 79,305 words

Ten Lessons for a Post-Pandemic World

by Fareed Zakaria · 5 Oct 2020 · 289pp · 86,165 words

Masters of Mankind

by Noam Chomsky · 1 Sep 2014

The Party: The Secret World of China's Communist Rulers

by Richard McGregor · 8 Jun 2010

Trading at the Speed of Light: How Ultrafast Algorithms Are Transforming Financial Markets

by Donald MacKenzie · 24 May 2021 · 400pp · 121,988 words

Battling Eight Giants: Basic Income Now

by Guy Standing · 19 Mar 2020

The City

by Tony Norfield · 352pp · 98,561 words

Boom and Bust: A Global History of Financial Bubbles

by William Quinn and John D. Turner · 5 Aug 2020 · 297pp · 108,353 words

The Post-American World: Release 2.0

by Fareed Zakaria · 1 Jan 2008 · 344pp · 93,858 words

Unfinished Business

by Tamim Bayoumi · 405pp · 109,114 words

The Greed Merchants: How the Investment Banks Exploited the System

by Philip Augar · 20 Apr 2005 · 290pp · 83,248 words

Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crises

by Timothy F. Geithner · 11 May 2014 · 593pp · 189,857 words

Revolting!: How the Establishment Are Undermining Democracy and What They're Afraid Of

by Mick Hume · 23 Feb 2017 · 228pp · 68,880 words

Paper Money Collapse: The Folly of Elastic Money and the Coming Monetary Breakdown

by Detlev S. Schlichter · 21 Sep 2011 · 310pp · 90,817 words

The Brussels Effect: How the European Union Rules the World

by Anu Bradford · 14 Sep 2020 · 696pp · 184,001 words

What's Wrong With Economics: A Primer for the Perplexed

by Robert Skidelsky · 3 Mar 2020 · 290pp · 76,216 words

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab and Peter Vanham · 27 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism

by Joyce Appleby · 22 Dec 2009 · 540pp · 168,921 words

The Production of Money: How to Break the Power of Banks

by Ann Pettifor · 27 Mar 2017 · 182pp · 53,802 words

Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist

by Kate Raworth · 22 Mar 2017 · 403pp · 111,119 words

What's Next?: Unconventional Wisdom on the Future of the World Economy

by David Hale and Lyric Hughes Hale · 23 May 2011 · 397pp · 112,034 words

The Corruption of Capitalism: Why Rentiers Thrive and Work Does Not Pay

by Guy Standing · 13 Jul 2016 · 443pp · 98,113 words

The Third Industrial Revolution: How Lateral Power Is Transforming Energy, the Economy, and the World

by Jeremy Rifkin · 27 Sep 2011 · 443pp · 112,800 words

The Growth Delusion: Wealth, Poverty, and the Well-Being of Nations

by David Pilling · 30 Jan 2018 · 264pp · 76,643 words

Propaganda and the Public Mind

by Noam Chomsky and David Barsamian · 31 Mar 2015

The Middleman Economy: How Brokers, Agents, Dealers, and Everyday Matchmakers Create Value and Profit

by Marina Krakovsky · 14 Sep 2015 · 270pp · 79,180 words

Losing Control: The Emerging Threats to Western Prosperity

by Stephen D. King · 14 Jun 2010 · 561pp · 87,892 words

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy That Works for Progress, People and Planet

by Klaus Schwab · 7 Jan 2021 · 460pp · 107,454 words

The Corona Crash: How the Pandemic Will Change Capitalism

by Grace Blakeley · 14 Oct 2020 · 82pp · 24,150 words

Angrynomics

by Eric Lonergan and Mark Blyth · 15 Jun 2020 · 194pp · 56,074 words

The End of Power: From Boardrooms to Battlefields and Churches to States, Why Being in Charge Isn’t What It Used to Be

by Moises Naim · 5 Mar 2013 · 474pp · 120,801 words

Private Island: Why Britain Now Belongs to Someone Else

by James Meek · 18 Aug 2014 · 232pp · 77,956 words

The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy

by Dani Rodrik · 23 Dec 2010 · 356pp · 103,944 words

The World in 2050: Four Forces Shaping Civilization's Northern Future

by Laurence C. Smith · 22 Sep 2010 · 421pp · 120,332 words

Better, Stronger, Faster: The Myth of American Decline . . . And the Rise of a New Economy

by Daniel Gross · 7 May 2012 · 391pp · 97,018 words

Financial Fiasco: How America's Infatuation With Homeownership and Easy Money Created the Economic Crisis

by Johan Norberg · 14 Sep 2009 · 246pp · 74,341 words

Life You Can Save: Acting Now to End World Poverty

by Peter Singer · 3 Mar 2009 · 190pp · 61,970 words

In Spite of the Gods: The Rise of Modern India

by Edward Luce · 23 Aug 2006 · 403pp · 132,736 words

The Sovereign Individual: How to Survive and Thrive During the Collapse of the Welfare State

by James Dale Davidson and William Rees-Mogg · 3 Feb 1997 · 582pp · 160,693 words

Makers and Takers: The Rise of Finance and the Fall of American Business

by Rana Foroohar · 16 May 2016 · 515pp · 132,295 words

Meat: A Benign Extravagance

by Simon Fairlie · 14 Jun 2010 · 614pp · 176,458 words

Occupy

by Noam Chomsky · 2 Jan 1994 · 75pp · 22,220 words

Rethinking Capitalism: Economics and Policy for Sustainable and Inclusive Growth

by Michael Jacobs and Mariana Mazzucato · 31 Jul 2016 · 370pp · 102,823 words

Why We Can't Afford the Rich

by Andrew Sayer · 6 Nov 2014 · 504pp · 143,303 words

Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy

by Raghuram Rajan · 24 May 2010 · 358pp · 106,729 words

The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Competition

by Jonathan Tepper · 20 Nov 2018 · 417pp · 97,577 words

Roads to Berlin

by Cees Nooteboom and Laura Watkinson · 2 Jan 1990 · 378pp · 120,490 words

Brexit, No Exit: Why in the End Britain Won't Leave Europe

by Denis MacShane · 14 Jul 2017 · 308pp · 99,298 words

The Nowhere Office: Reinventing Work and the Workplace of the Future

by Julia Hobsbawm · 11 Apr 2022 · 172pp · 50,777 words

Dreams of Leaving and Remaining

by James Meek · 5 Mar 2019 · 232pp · 76,830 words

Don't Be Evil: How Big Tech Betrayed Its Founding Principles--And All of US

by Rana Foroohar · 5 Nov 2019 · 380pp · 109,724 words

The Price Is Wrong: Why Capitalism Won't Save the Planet

by Brett Christophers · 12 Mar 2024 · 557pp · 154,324 words

The Price of Everything: And the Hidden Logic of Value

by Eduardo Porter · 4 Jan 2011 · 353pp · 98,267 words

13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown

by Simon Johnson and James Kwak · 29 Mar 2010 · 430pp · 109,064 words

The World's Banker: A Story of Failed States, Financial Crises, and the Wealth and Poverty of Nations

by Sebastian Mallaby · 24 Apr 2006 · 605pp · 169,366 words

Slowdown: The End of the Great Acceleration―and Why It’s Good for the Planet, the Economy, and Our Lives

by Danny Dorling and Kirsten McClure · 18 May 2020 · 459pp · 138,689 words

All the Money in the World

by Peter W. Bernstein · 17 Dec 2008 · 538pp · 147,612 words

The Undercover Economist: Exposing Why the Rich Are Rich, the Poor Are Poor, and Why You Can Never Buy a Decent Used Car

by Tim Harford · 15 Mar 2006 · 389pp · 98,487 words

Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy in the Aftermath of Crisis

by Anatole Kaletsky · 22 Jun 2010 · 484pp · 136,735 words

A Pelican Introduction: Basic Income

by Guy Standing · 3 May 2017 · 307pp · 82,680 words

Making Globalization Work

by Joseph E. Stiglitz · 16 Sep 2006

The Retreat of Western Liberalism

by Edward Luce · 20 Apr 2017 · 223pp · 58,732 words

Bad Samaritans: The Guilty Secrets of Rich Nations and the Threat to Global Prosperity

by Ha-Joon Chang · 4 Jul 2007 · 347pp · 99,317 words

Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 Dec 2007 · 334pp · 98,950 words

Power Systems: Conversations on Global Democratic Uprisings and the New Challenges to U.S. Empire

by Noam Chomsky and David Barsamian · 1 Nov 2012

Hopes and Prospects

by Noam Chomsky · 1 Jan 2009

Zero-Sum Future: American Power in an Age of Anxiety

by Gideon Rachman · 1 Feb 2011 · 391pp · 102,301 words

The End of Wall Street

by Roger Lowenstein · 15 Jan 2010 · 460pp · 122,556 words

The Economics Anti-Textbook: A Critical Thinker's Guide to Microeconomics

by Rod Hill and Anthony Myatt · 15 Mar 2010

Age of Anger: A History of the Present

by Pankaj Mishra · 26 Jan 2017 · 410pp · 106,931 words

The Internet Is Not the Answer

by Andrew Keen · 5 Jan 2015 · 361pp · 81,068 words

Bad Money: Reckless Finance, Failed Politics, and the Global Crisis of American Capitalism

by Kevin Phillips · 31 Mar 2008 · 422pp · 113,830 words

Nine Crises: Fifty Years of Covering the British Economy From Devaluation to Brexit

by William Keegan · 24 Jan 2019 · 309pp · 85,584 words

Not Working: Where Have All the Good Jobs Gone?

by David G. Blanchflower · 12 Apr 2021 · 566pp · 160,453 words

A Pelican Introduction Economics: A User's Guide

by Ha-Joon Chang · 26 May 2014 · 385pp · 111,807 words

Them and Us: How Immigrants and Locals Can Thrive Together

by Philippe Legrain · 14 Oct 2020 · 521pp · 110,286 words

Stuffocation

by James Wallman · 6 Dec 2013 · 296pp · 82,501 words

The Cost of Inequality: Why Economic Equality Is Essential for Recovery

by Stewart Lansley · 19 Jan 2012 · 223pp · 10,010 words

Tightrope: Americans Reaching for Hope

by Nicholas D. Kristof and Sheryl Wudunn · 14 Jan 2020 · 307pp · 96,543 words

The New Enclosure: The Appropriation of Public Land in Neoliberal Britain

by Brett Christophers · 6 Nov 2018

Adam Smith: Father of Economics

by Jesse Norman · 30 Jun 2018

Restarting the Future: How to Fix the Intangible Economy

by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake · 4 Apr 2022 · 338pp · 85,566 words

The Euro: How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe

by Joseph E. Stiglitz and Alex Hyde-White · 24 Oct 2016 · 515pp · 142,354 words

Chokepoints: American Power in the Age of Economic Warfare

by Edward Fishman · 25 Feb 2025 · 884pp · 221,861 words

Globalists

by Quinn Slobodian · 16 Mar 2018 · 451pp · 142,662 words

Shutdown: How COVID Shook the World's Economy

by Adam Tooze · 15 Nov 2021 · 561pp · 138,158 words

MegaThreats: Ten Dangerous Trends That Imperil Our Future, and How to Survive Them

by Nouriel Roubini · 17 Oct 2022 · 328pp · 96,678 words

Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking

by Michael Bhaskar · 2 Nov 2021

There Is Nothing for You Here: Finding Opportunity in the Twenty-First Century

by Fiona Hill · 4 Oct 2021 · 569pp · 165,510 words

Green Swans: The Coming Boom in Regenerative Capitalism

by John Elkington · 6 Apr 2020 · 384pp · 93,754 words

Third World America: How Our Politicians Are Abandoning the Middle Class and Betraying the American Dream

by Arianna Huffington · 7 Sep 2010 · 300pp · 78,475 words

Paper Promises

by Philip Coggan · 1 Dec 2011 · 376pp · 109,092 words

The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking and the Future of the Global Economy

by Mervyn King · 3 Mar 2016 · 464pp · 139,088 words

The Age of Stagnation: Why Perpetual Growth Is Unattainable and the Global Economy Is in Peril

by Satyajit Das · 9 Feb 2016 · 327pp · 90,542 words

Rethinking Islamism: The Ideology of the New Terror

by Meghnad Desai · 25 Apr 2008

House of Debt: How They (And You) Caused the Great Recession, and How We Can Prevent It From Happening Again

by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi · 11 May 2014 · 249pp · 66,383 words

Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer-And Turned Its Back on the Middle Class

by Paul Pierson and Jacob S. Hacker · 14 Sep 2010 · 602pp · 120,848 words

The Trouble With Billionaires

by Linda McQuaig · 1 May 2013 · 261pp · 81,802 words

The Innovation Illusion: How So Little Is Created by So Many Working So Hard

by Fredrik Erixon and Bjorn Weigel · 3 Oct 2016 · 504pp · 126,835 words

The Finance Curse: How Global Finance Is Making Us All Poorer

by Nicholas Shaxson · 10 Oct 2018 · 482pp · 149,351 words

Were You Born on the Wrong Continent?

by Thomas Geoghegan · 20 Sep 2011 · 364pp · 104,697 words

Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization

by Branko Milanovic · 10 Apr 2016 · 312pp · 91,835 words

Broke: How to Survive the Middle Class Crisis

by David Boyle · 15 Jan 2014 · 367pp · 108,689 words

Adapt: Why Success Always Starts With Failure

by Tim Harford · 1 Jun 2011 · 459pp · 103,153 words

Because We Say So

by Noam Chomsky

The Fourth Revolution: The Global Race to Reinvent the State

by John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge · 14 May 2014 · 372pp · 92,477 words

Treasure Islands: Uncovering the Damage of Offshore Banking and Tax Havens

by Nicholas Shaxson · 11 Apr 2011 · 429pp · 120,332 words

Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea

by Mark Blyth · 24 Apr 2013 · 576pp · 105,655 words

Before Babylon, Beyond Bitcoin: From Money That We Understand to Money That Understands Us (Perspectives)

by David Birch · 14 Jun 2017 · 275pp · 84,980 words

European Spring: Why Our Economies and Politics Are in a Mess - and How to Put Them Right

by Philippe Legrain · 22 Apr 2014 · 497pp · 150,205 words

More: The 10,000-Year Rise of the World Economy

by Philip Coggan · 6 Feb 2020 · 524pp · 155,947 words

Them And Us: Politics, Greed And Inequality - Why We Need A Fair Society

by Will Hutton · 30 Sep 2010 · 543pp · 147,357 words

Trade Wars Are Class Wars: How Rising Inequality Distorts the Global Economy and Threatens International Peace

by Matthew C. Klein · 18 May 2020 · 339pp · 95,270 words

The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis

by Christiana Figueres and Tom Rivett-Carnac · 25 Feb 2020 · 197pp · 49,296 words

The Upside of Inequality

by Edward Conard · 1 Sep 2016 · 436pp · 98,538 words

The Only Game in Town: Central Banks, Instability, and Avoiding the Next Collapse

by Mohamed A. El-Erian · 26 Jan 2016 · 318pp · 77,223 words

Rentier Capitalism: Who Owns the Economy, and Who Pays for It?

by Brett Christophers · 17 Nov 2020 · 614pp · 168,545 words

Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing

by Josh Ryan-Collins, Toby Lloyd and Laurie Macfarlane · 28 Feb 2017 · 346pp · 90,371 words

Globish: How the English Language Became the World's Language

by Robert McCrum · 24 May 2010 · 325pp · 99,983 words

Poisoned Wells: The Dirty Politics of African Oil

by Nicholas Shaxson · 20 Mar 2007

Money and Government: The Past and Future of Economics

by Robert Skidelsky · 13 Nov 2018

Re-Educated: Why It’s Never Too Late to Change Your Life

by Lucy Kellaway · 30 Jun 2021 · 184pp · 60,229 words

Growth: A Reckoning

by Daniel Susskind · 16 Apr 2024 · 358pp · 109,930 words

The Third Pillar: How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind

by Raghuram Rajan · 26 Feb 2019 · 596pp · 163,682 words

The Meritocracy Trap: How America's Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class, and Devours the Elite

by Daniel Markovits · 14 Sep 2019 · 976pp · 235,576 words

Our Lives in Their Portfolios: Why Asset Managers Own the World

by Brett Chistophers · 25 Apr 2023 · 404pp · 106,233 words

The Dream of Europe: Travels in the Twenty-First Century

by Geert Mak · 27 Oct 2021 · 722pp · 223,701 words

Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism

by Anne Case and Angus Deaton · 17 Mar 2020 · 421pp · 110,272 words

Are Chief Executives Overpaid?

by Deborah Hargreaves · 29 Nov 2018 · 98pp · 27,201 words

The Age of Entitlement: America Since the Sixties

by Christopher Caldwell · 21 Jan 2020 · 450pp · 113,173 words

Servant Economy: Where America's Elite Is Sending the Middle Class

by Jeff Faux · 16 May 2012 · 364pp · 99,613 words

Aftershocks: Pandemic Politics and the End of the Old International Order

by Colin Kahl and Thomas Wright · 23 Aug 2021 · 652pp · 172,428 words

Every Nation for Itself: Winners and Losers in a G-Zero World

by Ian Bremmer · 30 Apr 2012 · 234pp · 63,149 words

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

Kleptopia: How Dirty Money Is Conquering the World

by Tom Burgis · 7 Sep 2020 · 476pp · 139,761 words

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress

by Steven Pinker · 13 Feb 2018 · 1,034pp · 241,773 words

Green Philosophy: How to Think Seriously About the Planet

by Roger Scruton · 30 Apr 2014 · 426pp · 118,913 words

The Euro and the Battle of Ideas

by Markus K. Brunnermeier, Harold James and Jean-Pierre Landau · 3 Aug 2016 · 586pp · 160,321 words

When China Rules the World: The End of the Western World and the Rise of the Middle Kingdom

by Martin Jacques · 12 Nov 2009 · 859pp · 204,092 words

Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work

by Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams · 1 Oct 2015 · 357pp · 95,986 words

Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism

by David Harvey · 3 Apr 2014 · 464pp · 116,945 words

Republic, Lost: How Money Corrupts Congress--And a Plan to Stop It

by Lawrence Lessig · 4 Oct 2011 · 538pp · 121,670 words

The Economic Singularity: Artificial Intelligence and the Death of Capitalism

by Calum Chace · 17 Jul 2016 · 477pp · 75,408 words

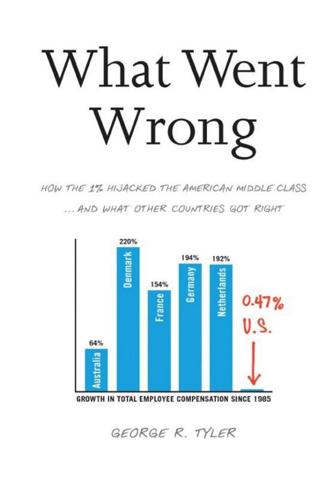

What Went Wrong: How the 1% Hijacked the American Middle Class . . . And What Other Countries Got Right

by George R. Tyler · 15 Jul 2013 · 772pp · 203,182 words

The Making of Global Capitalism

by Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin · 8 Oct 2012 · 823pp · 206,070 words

Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World

by Adam Tooze · 31 Jul 2018 · 1,066pp · 273,703 words

Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown

by Philip Mirowski · 24 Jun 2013 · 662pp · 180,546 words

Who Rules the World?

by Noam Chomsky

The Bankers' New Clothes: What's Wrong With Banking and What to Do About It

by Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig · 15 Feb 2013 · 726pp · 172,988 words

Creative Intelligence: Harnessing the Power to Create, Connect, and Inspire

by Bruce Nussbaum · 5 Mar 2013 · 385pp · 101,761 words

The Rise of the Outsiders: How Mainstream Politics Lost Its Way

by Steve Richards · 14 Jun 2017 · 323pp · 95,492 words

Britannia Unchained: Global Lessons for Growth and Prosperity

by Kwasi Kwarteng, Priti Patel, Dominic Raab, Chris Skidmore and Elizabeth Truss · 12 Sep 2012

Superclass: The Global Power Elite and the World They Are Making

by David Rothkopf · 18 Mar 2008 · 535pp · 158,863 words

The Powerful and the Damned: Private Diaries in Turbulent Times

by Lionel Barber · 5 Nov 2020

The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era

by Gary Gerstle · 14 Oct 2022 · 655pp · 156,367 words

Crisis Economics: A Crash Course in the Future of Finance

by Nouriel Roubini and Stephen Mihm · 10 May 2010 · 491pp · 131,769 words

The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest

by Edward Chancellor · 15 Aug 2022 · 829pp · 187,394 words

Plutocrats: The Rise of the New Global Super-Rich and the Fall of Everyone Else

by Chrystia Freeland · 11 Oct 2012 · 481pp · 120,693 words

The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class

by Joel Kotkin · 11 May 2020 · 393pp · 91,257 words

Civilization: The West and the Rest

by Niall Ferguson · 28 Feb 2011 · 790pp · 150,875 words

The Man Who Knew: The Life and Times of Alan Greenspan

by Sebastian Mallaby · 10 Oct 2016 · 1,242pp · 317,903 words

The Bank That Lived a Little: Barclays in the Age of the Very Free Market

by Philip Augar · 4 Jul 2018 · 457pp · 143,967 words

The Economics of Belonging: A Radical Plan to Win Back the Left Behind and Achieve Prosperity for All

by Martin Sandbu · 15 Jun 2020 · 322pp · 84,580 words

Liberalism at Large: The World According to the Economist

by Alex Zevin · 12 Nov 2019 · 767pp · 208,933 words

The Identity Trap: A Story of Ideas and Power in Our Time

by Yascha Mounk · 26 Sep 2023

Pivotal Decade: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the Seventies

by Judith Stein · 30 Apr 2010 · 497pp · 143,175 words