The Rise of the Network Society

by

Manuel Castells

Published 31 Aug 1996

Thus, the social dimension of the information technology revolution seems bound to follow the law on the relationship between technology and society proposed some time ago by Melvin Kranzberg: “Kranzberg’s First Law reads as follows: Technology is neither good nor bad, nor is it neutral.”104 It is indeed a force, probably more than ever under the current technological paradigm that penetrates the core of life and mind.105 But its actual deployment in the realm of conscious social action, and the complex matrix of interaction between the technological forces unleashed by our species, and the species itself, are matters of inquiry rather than of fate. I shall now proceed with such an inquiry. 1 Gould (1980: 226). 2 Melvin Kranzberg, one of the leading historians of technology, wrote “The information age has indeed revolutionized the technical elements of industrial society” (1985: 42).

…

Cohen, Martin Carnoy, Alain Touraine, Anthony Giddens, Daniel Bell, Jesus Leal, Shujiro Yazawa, Peter Hall, Chu-joe Hsia, You-tien Hsing, François Bar, Michael Borrus, Harley Shaiken, Claude Fischer, Nicole Woolsey-Biggart, Bennett Harrison, Anne Marie Guillemard, Richard Nelson, Loic Wacquant, Ida Susser, Fernando Calderon, Roberto Laserna, Alejandro Foxley, John Urry, Guy Benveniste, Katherine Burlen, Vicente Navarro, Dieter Ernst, Padmanabha Gopinath, Franz Lehner, Julia Trilling, Robert Benson, David Lyon and Melvin Kranzberg. Throughout the past 12 years a number of institutions have constituted the basis for this work. First of all is my intellectual home, the University of California at Berkeley, and more specifically the academic units in which I have worked: the Department of City and Regional Planning, the Department of Sociology, the Center for Western European Studies, the Institute of Urban and Regional Development, and the Berkeley Roundtable on the International Economy.

…

This approach stems from my conviction that we have entered a truly multicultural, interdependent world, which can only be understood, and changed, from a plural perspective that brings together cultural identity, global networking, and multidimensional politics. 1 Recounted in Sima Qian (145–c.89BC), “Confucius,” in Hu Shi, The Development of Logical Methods in Ancient China (Shanghai: Oriental Book Company, 1922), quoted in Qian (1985: 125). 2 See the interesting debate on the matter in Smith and Marx (1994). 3 Technology does not determine society: it embodies it. But nor does society determine technological innovation: it uses it. This dialectical interaction between society and technology is present in the works of the best historians, such as Fernand Braudel. 4 Classic historian of technology Melvin Kranzberg has forcefully argued against the false dilemma of technological determinism. See, for instance, Kranzberg’s (1992) acceptance speech of the award of honorary membership in NASTS. 5 Bijker et al. (1987). 6 There is still to be written a fascinating social history of the values and personal views of some of the key innovators of the 1970s’ Silicon Valley revolution in computer technologies.

The Twittering Machine

by

Richard Seymour

Published 20 Aug 2019

What if, in deliberate abdication of our smartphones, we strolled in the park with nothing but a notepad and a nice pen? What if we sat in a church and closed our eyes? What if we lay back on a lily pad, with nothing to do? Would someone call the police? REFERENCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTES FOREWORD 1. All technology, as the historian Melvin Kranzberg put it . . . Melvin Kranzberg, ‘Technology and History: “Kranzberg’s Laws” ’, Technology and Culture, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Jul., 1986), pp. 544–560. CHAPTER ONE 1. The Museum of Modern Art explains: Paul Klee, Twittering Machine (Die Zwitscher-Maschine) 1922, MoMA: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/37347. 2.

…

Digital image © 2019, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence To the Luddites CONTENTS FOREWORD ONE: WE ARE ALL CONNECTED TWO: WE ARE ALL ADDICTS THREE: WE ARE ALL CELEBRITIES FOUR: WE ARE ALL TROLLS FIVE: WE ARE ALL LIARS SIX: WE ARE ALL DYING CONCLUSION: WE ARE ALL SCRIPTURIENT REFERENCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTES ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS FOREWORD Everything on the computer is writing. Everything on the net is writing in sites, files and protocols. Sandy Baldwin, The Internet Unconscious The Twittering Machine is a horror story, even though it is about technology that is in itself neither good nor bad. All technology, as the historian Melvin Kranzberg put it, is ‘neither good nor bad; nor neutral’.1 We tend to ascribe magical powers to technologies: the smartphone is our golden ticket, the tablet our mystic writing pad. In technology, we find our own alienated powers in a moralized form: either a benevolent genie or a tormenting demon. These are paranoid fantasies, whether or not they seem malign, because in them we are at the mercy of the devices.

Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest

by

Zeynep Tufekci

Published 14 May 2017

A baseball bat may be a potent weapon for murdering one person at a time, but it is not a very efficient tool for mass murder. A machine gun or a bomb, however, is. One can appreciate the impulse to ask that humans shoulder responsibility for their choices, but history shows that technology is not just a neutral tool that equally empowers every potential use, outcome, or person. The historian Melvin Kranzberg perhaps stated this best with his first law of technology: “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral” (my italics).16 Technology alters the landscape in which human social interaction takes place, shifts the power and the leverage between actors, and has many other ancillary effects.

…

There are many parts of the world where there was no electricity just a decade ago, and now where even children have cellphones—and there still may not be electricity, at least not regularly.7 One key lesson from the past is that our familiarity with a new and rapidly spreading technologies is often superficial, and the full ramifications of these technologies are far from worked out. Another lesson is that what appears to empower one group can also empower its adversaries, and introduce novel twists to many dynamics. Historian Melvin Kranzberg’s famous dictum holds true: “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.”8 Neither are technology’s effects static; everything evolves as people invent, innovate, and appropriate technologies for their purposes. This dynamism does not mean that technology provides a level playing field, where each side is equally empowered and equally able to appropriate technologies for its purposes.

…

Brady, and David Collier (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 217–49, for social science; and Judea Pearl, Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), for modeling and inference. 15. George Orwell, “George Orwell: You and the Atomic Bomb,” 1945, http://orwell.ru/library/articles/ABomb/english/e_abomb. 16. Melvin Kranzberg, “Technology and History: ‘Kranzberg’s Laws,’” Technology and Culture 27, no. 3 (1986): 544–60. (Quote is on page 545.) 17. Tarleton Gillespie, Pablo J. Boczkowski, and Kirsten A. Foot, eds., Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, 1st ed. (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2014); Paul M.

The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding From You

by

Eli Pariser

Published 11 May 2011

“‘We just want to do cool stuff,’ was the attitude,” Scott told me later. “ ‘Don’t bother me with this politics stuff.’ ” Technodeterminists like to suggest that technology is inherently good. But despite what Kevin Kelly says, technology is no more benevolent than a wrench or a screwdriver. It’s only good when people make it do good things and use it in good ways. Melvin Kranzberg, a professor who studies the history of technology, put it best nearly thirty years ago, and his statement is now known as Kranzberg’s first law: “Technology is neither good or bad, nor is it neutral.” For better or worse, programmers and engineers are in a position of remarkable power to shape the future of our society.

…

Your Other Rights Are,” Cato Unbound, May 1, 2009, accessed Dec. 16, 2010, www.cato-unbound.org/2009/05/01/peter-thiel/your-suffrage-isnt-in-danger-your-other-rights-are. 185 talked to Scott Heiferman: Interview with author, New York, NY, Oct. 5, 2010. 188 “good or bad, nor is it neutral”: Melvin Kranzberg, “Technology and History: ‘Kranzberg’s Laws,’ ” Technology and Culture 27, no. 3 (1986): 544–60. Chapter Seven: What You Want, Whether You Want It or Not 189 “millions of people doing complicated things”: Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Montfort, The New Media Reader, Vol. 1 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), 8. 189 “yet to be completely correlated”: Isaac Asimov, The Intelligent Man’s Guide to Science (New York: Basic Books, 1965), 190 “you’ve got a problem”: Bill Jay, phone interview with author, Oct. 10, 2010. 191 ads tailored to her: Jason Mick, “Tokyo’s ‘Minority Report’ Ad Boards Scan Viewer’s Sex and Age,” Daily Tech, July 16, 2010, accessed Dec. 17, 2010, www.dailytech.com/Tokyos+Minority+Report+Ad+Boards+Scan+Viewers+Sex+and+Age/article19063.htm. 191 the future of art: David Shields, Reality Hunger: A Manifesto (New York: Knopf, 2010).

The Formula: How Algorithms Solve All Our Problems-And Create More

by

Luke Dormehl

Published 4 Nov 2014

What the speed limit algorithm experiment mentioned earlier in this chapter shows more than anything is the degree to which assumptions are built into the code that computer programmers write, even when those problems being solved might be relatively mechanical in nature. As technology historian Melvin Kranzberg’s first law of technology states: “Technology is neither good nor bad—nor is it neutral.” Implicit or explicit biases might be the work of one or two human programmers, or else come down to technological difficulties. For example, algorithms used in facial recognition technology have in the past shown higher identification rates for men than for women, and for individuals of non-white origin than for whites.

…

Instead, the tricks . . . resemble tricks of the trade or even magic tricks: clever techniques for accomplishing goals that would otherwise be difficult or impossible.19 While perhaps a well-intentioned distinction, MacCormick’s error is his casual assumption about a sense of algorithmic morality. Stating that algorithms and the goals they aim to accomplish are neither good nor bad (although, to return to Melvin Kranzberg’s first law of technology, nor are they neutral) seems an extraordinarily sweeping and unqualified statement. Nonetheless, it is one that has been made by a number of renowned technology writers. In a controversial 2008 article published in Wired magazine, journalist Chris Anderson announced that the age of big datasets and algorithms equaled what he grandly referred to as “The End of Theory.”

The End of Absence: Reclaiming What We've Lost in a World of Constant Connection

by

Michael Harris

Published 6 Aug 2014

PART 1 * * * Gathering We think we have discovered a grotto that is stored with bewildering treasure; we come back to the light of day, and the gems we have brought are false—mere pieces of glass—and yet does the treasure shine on, unceasingly, in the darkness. —Maurice Maeterlinck CHAPTER 1 This Kills That Technology is neither good nor bad, nor is it neutral. —Melvin Kranzberg SOON enough, nobody will remember life before the Internet. What does this unavoidable fact mean? For those billions who come next, of course, it won’t mean anything very obvious. Our online technologies, taken as a whole, will have become a kind of foundational myth—a story people are barely conscious of, something natural and, therefore, unnoticed.

…

One daughter: Linda Jimi, interview with and e-mail message to author, January 17, 2013. Part 1: Gathering “We think we have discovered”: Maurice Maeterlinck, “La morale mystique,” in The Treasure of the Humble, trans. Alfred Sutro (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1903), 61–62. Chapter 1: This Kills That “Technology is neither good nor bad”: Melvin Kranzberg, “Technology and History: ‘Kranzberg’s Laws,’” Technology and Culture 27, no. 3 (1986): 544–60. a kind of foundational myth: I’m using the broader sense of “myth” here, as defined by Roland Barthes in his 1957 book Mythologies (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1957). “once people get used”: Gary Small and Gigi Vorgan, iBrain: Surviving the Technological Alteration of the Modern Mind (New York: HarperCollins, 2008), 18.

A Brief History of Motion: From the Wheel, to the Car, to What Comes Next

by

Tom Standage

Published 16 Aug 2021

From Horseless to Driverless 12. The Road Ahead Acknowledgments Notes Sources Image Credits Index A Note on the Author INTRODUCTION Many of our technology-related problems arise because of the unforeseen consequences when apparently benign technologies are employed on a massive scale. —MELVIN KRANZBERG, AMERICAN HISTORIAN (1917–95) The story of the dawn of the automotive era traditionally goes something like this. In the 1890s the biggest cities of the Western world faced a mounting problem. Horse-drawn vehicles had been in use for thousands of years, and it was hard to imagine life without them.

…

Others, particularly in China, are working with city authorities to make urban environments more AV friendly, for example by installing dedicated infrastructure to support AVs, restricting access for other vehicles in some districts, and limiting AV firms’ legal liability in the event of accidents. Should they eventually materialize, robotaxis seem likely to be part of the answer to what comes after the automotive age—but only part of it. So what does the postcar world look like? 12 The Road Ahead Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral. —MELVIN KRANZBERG, AMERICAN HISTORIAN (1917–95) THE LONG HISTORY OF THE END OF THE CAR People have been predicting the end of the automotive era for decades. In 1958, a time that is now remembered as the height of American car culture, John Keats, an American satirist, published The Insolent Chariots. A humorous broadside against the excesses of the American car industry and car culture, it was the sequel to The Crack in the Picture Window, an attack on the sprawl of suburbia.

We Are Data: Algorithms and the Making of Our Digital Selves

by

John Cheney-Lippold

Published 1 May 2017

Through my data alone, I have entered into even more conversations about who I am and what who I am means, conversations that happen without my knowledge and with many more participants involved than most of us could imagine. To make the world according to algorithm is, to paraphrase one of historian Melvin Kranzberg’s laws of technology, neither good nor bad nor neutral.93 But it is new and thus nascent and unperfected. It’s a world of unfastening, temporary subject arrangements that allows a user to be, for example, 23 percent confidently ‘woman’ and 84 percent confidently ‘man’ at the same time. Categories of identity of any sort, quotation-marked or not, might not be superficial, but they also aren’t impossibly profound.

…

Evgeny Dantsin, Thomas Eiter, Georg Gottlob, and Andrei Voronkov, “Complexity and Expressive Power of Logic Programming,” ACM Computing Surveys 33, no. 3 (2001): 374–425; Ian Bogost, Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007); Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Expressive Processing: Digital Fictions, Computer Games, and Software Studies (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009). 92. Kevin Kelly and Derrick de Kerckhove, “4.10: What Would McLuhan Say?,” Wired, October 1, 1996, http://archive.wired.com. 93. Melvin Kranzberg, “Technology and History: ‘Kranzberg’s Laws,’” Technology and Culture 27, no. 3 (1986): 544–560. 94. David Lyon, Surveillance Society: Monitoring Everyday Life (Berkshire, UK: Open University Press, 2001); Daniel Solove, The Digital Person: Technology and Privacy in the Information Age (Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, 2004). 95.

How Not to Network a Nation: The Uneasy History of the Soviet Internet (Information Policy)

by

Benjamin Peters

Published 2 Jun 2016

Leading cyber legal scholar Yochai Benkler has argued for a middle way by observing how online modes of “commons-based peer production” sustain capitalist profit margins through collectivist forms of reputational altruistic communities that do not depend on individual self-interest.11 From the final chapters of Soviet history, we may begin to observe and puzzle through the perennial fact that, for many Western technologists and scholars, the promise of socialist collaboration shines brightest online today—a promise that the Soviet OGAS designers were among the first to foresee. None of the conditions—technological, sociological, economic, or otherwise—for the flourishing of computer networks are necessarily as we may think. As Melvin Kranzberg’s first law of technology holds, technology is neither positive, negative, nor neutral.12 The same holds for society and economy. By looking at failed network projects, I seek to flip science anthropologist and philosopher Bruno Latour’s aphorism that technology is society made durable. We observe in the collapse of the Soviet network projects a lesson for humans who live in a fragile world: society too is technology made temporary.13 The Soviet experience with networks reminds us that although computer networks are prospering today, our modern social assumptions about those networks are no more inevitable or permanent than those of the Soviets.

…

Manuel Castells, End of the Millennium: The Information Age—Economy, Society, and Culture (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1998), 5–68; Lawrence Lessig, Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace (New York: Basic Books, 1999), 3–8. 11. Yochai Benkler, The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006). 12. Melvin Kranzberg, “Technology and History: ‘Kranzberg’s Laws,’” Technology and Culture 27 (3) (1986): 544–560. 13. For Latour’s aphorism, see Bruno Latour, “Technology Is Society Made Durable,” in A Sociology of Monsters: Essays on Power, Technology and Domination, ed. John Law, Sociological Review Monograph No. 38 (London: Routledge, 1991), 103–132.

Smarter Than You Think: How Technology Is Changing Our Minds for the Better

by

Clive Thompson

Published 11 Sep 2013

Today, of course, everyday use has so domesticated the technology that nostalgics now regard the telephone as an emotionally vibrant form of communication that the Internet is tragically killing off. This isn’t to say that technology changes nothing for the worse or that these criticisms weren’t partly correct. “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral,” as the technology thinker Melvin Kranzberg pointed out. It’s why each tool needs to be carefully scrutinized on its own merits. The stuff we find merely annoying about a new technology in the short run is often off base, and we can miss the subtler ways it alters patterns of thought in the long run. Personally, I suspect a bigger danger of modern ambient contact is that it reinforces the recency effect—making us feel that information arriving right now is more important than events that happened yesterday, last month, or last century.

…

“A Telephonic Conversation”: Mark Twain, “A Telephonic Conversation,” The Atlantic Monthly, June 1, 1880, accessed March 26, 2013, www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1880/06/a-telephonic-conversation/306078/#. derived from the shout of “halloo”: Baron, Always On, 174. “Technology is neither good nor bad”: Melvin Kranzberg, “Technology and History: ‘Kranzberg’s Laws,’” Technology and Culture 27, no. 3 (July 1986): 544–60. “This binds together by a vital cord”: Briggs and Maverick, The Story of the Telegraph, 22. the “aerial” man . . . mobile phones: Langdon Winner, “Sow’s Ears from Silk Purses,” in Technological Visions: Hopes and Fears That Shape New Technologies, eds.

Exponential: How Accelerating Technology Is Leaving Us Behind and What to Do About It

by

Azeem Azhar

Published 6 Sep 2021

Gig work tells a similar tale: in the UK, a rich country with a well-established formal labour market, gig-working platforms may be seen to unacceptably undermine workers’ rights and protections. In India or Nigeria, the same technologies may bring benefits, as these countries have a more informal work market based on day labour. In other words, it is our choices and our circumstances that determine how technology is actually used. As the historian Melvin Kranzberg put it: ‘The point is that the same technology can answer questions differently, depending on the context into which it is introduced and the problem it is designed to solve.’ But acknowledging that the direction of technology is not preordained doesn’t amount to saying that technology isn’t transformative.

…

Anchang, ‘Satellites Could Soon Map Every Tree on Earth’, Nature, 14 October 2020 <https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02830-3>. 10 This idea was first espoused in 1865 by William Jevons in his essay ‘The Coal Question’. 11 Sheila Jasanoff, The Ethics of Invention (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2016). 12 Melvin Kranzberg, ‘Technology and History: “Kranzberg’s Laws”’, Technology and Culture, 27(3), 1986, pp. 544–560 <https://doi.org/10.2307/3105385>. 13 Jasanoff, The Ethics of Invention. Select Bibliography Acemoglu, Daron, Claire LeLarge and Pascual Restrepo, Competing with Robots: Firm-Level Evidence from France, Working Paper Series (National Bureau of Economic Research, February 2020) <https://doi.org/10.3386/w26738> Acemoglu, Daron, and Pascual Restrepo, Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets, Working Paper Series (National Bureau of Economic Research, March 2017) <https://doi.org/10.3386/w23285> Acton, James M., ‘Cyber Warfare & Inadvertent Escalation’, Daedalus, 149(2), 2020, pp. 133–49 <https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_01794> Agrawal, Ravi, ‘The Hidden Benefits of Uber’, Foreign Policy, 16 July 2018 <https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/07/16/why-india-gives-uber-5-stars-gig-economy-jobs/> [accessed 21 September 2020] Allen, Robert C., ‘Engels’ Pause: Technical Change, Capital Accumulation, and Inequality in the British Industrial Revolution’, Explorations in Economic History, 46(4), 2009, pp. 418–35 <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2009.04.004> Almenberg, Johan, and Christer Gerdes, ‘Exponential Growth Bias and Financial Literacy’, Applied Economics Letters, 19(17), 2012, pp. 1693–96 <https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2011.652772> Anthony, Scott D., ‘Kodak’s Downfall Wasn’t About Technology’, Harvard Business Review, 15 July 2016 <https://hbr.org/2016/07/kodaks-downfall-wasnt-about-technology> [accessed 14 December 2020] ‘Arithmetic, Population and Energy – a Talk by Al Bartlett’ <https://www.albartlett.org/presentations/arithmetic_population_energy.html> [accessed 3 December 2020] Arnold, Carrie, ‘How Computational Immunology Changed the Face of COVID-19 Vaccine Development’, Nature Medicine, 15 July 2020 <https://doi.org/10.1038/d41591-020-00027-9> Arthur, W.

The People vs Tech: How the Internet Is Killing Democracy (And How We Save It)

by

Jamie Bartlett

Published 4 Apr 2018

But the invention of ‘barbed wire’ (sharp metal barbs twisted around a strand of smooth wire, with a second intertwined piece of wire so that the barbs couldn’t slide) meant that huge swathes of land could be enclosed. Roaming buffalo were doomed, which in turn destroyed the Native American way of life (understandably, they nicknamed barbed wire ‘the devil’s rope’).2 Technology, according to the famous professor of technology history, Melvin Kranzberg, is ‘neither good nor bad; but nor is it neutral’. (Public key) encryption is the crypto-anarchist’s barbed wire. It allows people to communicate, browse and transact beyond the reach of government, making it significantly harder for the state to control information, and subsequently, its citizens.

Fully Automated Luxury Communism

by

Aaron Bastani

Published 10 Jun 2019

But the measure of success can’t be the volume of transactions through the price system – to do so would be using the definition of progress that belongs to a world already passing away. 12 FALC: A New Beginning Socialism is not evolution’s last and perfect product or the end of history, but in a sense only the beginning. Isaac Deutscher The relationship between technology and politics is a complicated one. Melvin Kranzberg put it best in his ‘Six Laws of Technology’ when he outlined the first of those laws: ‘Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.’ In other words, how technology is created and used, and to whose advantage, depends on the political, ethical and social contexts from which it emerges.

The Great Wave: The Era of Radical Disruption and the Rise of the Outsider

by

Michiko Kakutani

Published 20 Feb 2024

In this ecosystem, more and more energy is moving from the margins toward the center, from the grassroots upward, from start-ups, protesters, and outsiders—a kind of countermovement to Big Tech’s monopolistic consolidation of power and the efforts of authoritarian leaders to centralize power in their own hands. The historian Melvin Kranzberg once observed that “technology is neither good nor bad, nor is it neutral,” and the same might well be said of the growing influence of outsiders. Some have demonstrated their courage, resolve, and imaginative leadership, like Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky, a former actor and comedian (elected by a landslide in 2019) who rallied the free world around his country after Vladimir Putin launched an unprovoked invasion in early 2022.

Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work

by

Nick Srnicek

and

Alex Williams

Published 1 Oct 2015

David Autor, Frank Levy and Richard Murnane, ‘The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration’, Quarterly Journal of Economics 118: 4 (2003); Amit Basole, ‘Class-Biased Technical Change and Socialism: Some Reflections on Benedito Moraes-Neto’s “On the Labor Process and Productive Efficiency: Discussing the Socialist Project”’, Rethinking Marxism 25: 4 (2013). 112.For one of the earliest arguments to this effect, see Raniero Panzieri, ‘The Capitalist Use of Machinery: Marx Versus the “Objectivists”’, in Slater, Outlines of a Critique of Technology. 113.David F. Noble, Forces of Production: A Social History of Industrial Automation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986); Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume I, transl. Ben Fowkes (London: Penguin, 1990), p. 526. 114.Melvin Kranzberg, ‘Technology and History: ‘‘Kranzberg’s Laws”’, Technology and Culture 27:3 (1986), p. 545. 115.George Basalla, The Evolution of Technology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), p. 7. 116.On how users shape technology, see Nellie Ooudshorn and Trevor Pinch, eds, How Users Matter: The Co-Construction of Users and Technology (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005). 117.Harry Cleaver, ‘Technology as Political Weaponry’, in The Responsibility of the Scientific and Technological Enterprise in Technology Transfer, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1981, pdf available at academia.edu. 118.Even if never used, nuclear weapons are still fundamentally premised on this function. 119.For an incisive reflection on cognitive workers and their relation to other figures of the working class, see Matteo Pasquinelli, ‘To Anticipate and Accelerate: Italian Operaismo and Reading Marx’s Notion of the Organic Composition of Capital’, Rethinking Marxism 26: 2 (2014). 8.

The Evolution of Useful Things

by

Henry Petroski

Published 2 Jan 1992

Where practitioners have written or spoken for the record, their works are referenced in my bibliography, as are all those in which I can recall having read support for my thesis. By their example and encouragement, certain writers, engineers, and historians of technology have been especially instrumental in influencing this book, and I must single out Freeman Dyson, Eugene Ferguson, Melvin Kranzberg, and Walter Vincenti for their support. A book naturally takes time and space to write, and I am indebted to a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation for the former and to a carrel in Perkins Library for the latter. I am grateful to my supportive editor, Ashbel Green, and to the many others at Alfred A.

Utopias: A Brief History From Ancient Writings to Virtual Communities

by

Howard P. Segal

Published 20 May 2012

On Plato’s relatively limited influence before Utopia appeared, see John Ferguson, Utopias of the Classical World (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1975), chs. 9–10, 12–13, 18–20. The European Utopias and Utopians and Their Critics 5 6 7 8 On the English Industrial Revolution and its aftermath, see Phyllis Deane, The First Industrial Revolution, 2nd edn. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), a fine survey; Melvin Kranzberg, “Prerequisites for Industrialization,” in Technology in Western Civilization, eds. Kranzberg and Carroll W. Pursell, Jr., 2 vols. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), vol. 1: 217–230, an illuminating comparison of England and France in the eighteenth century and the reasons why the former led the latter into industrialization despite France’s superiority in many ways over England; David S.

Consider the Fork: A History of How We Cook and Eat

by

Bee Wilson

Published 14 Sep 2012

We can all think of examples of more or less pointless pieces of culinary equipment—the melon baller, the avocado slicer, the garlic peeler—to which we can only respond: what was wrong with a spoon, a knife, or fingers? Our cooking benefits from much uncredited engineering, but there have also been gadgets that create more problems than they solve, and others that work perfectly well, but at a human cost. Historians of technology often quote Kranzberg’s First Law (formulated by Melvin Kranzberg in a seminal essay in 1986): “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.” This is certainly true in the kitchen. Tools are not neutral objects. They change with changing social context. A mortar and pestle was a different thing for the Roman slave forced to pound up highly amalgamated mixtures for hours on end for his master’s enjoyment than it is for me: a pleasing object with which I make pesto for fun, on a whim.

Zucked: Waking Up to the Facebook Catastrophe

by

Roger McNamee

Published 1 Jan 2019

Classification: LCC HM743.F33 (ebook) | LCC HM743.F33 M347 2019 (print) | DDC 302.30285—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018048578 While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. Version_1 To Ann, who inspires me every day Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral. —Melvin Kranzberg’s First Law of Technology We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them. —Albert Einstein Ultimately, what the tech industry really cares about is ushering in the future, but it conflates technological progress with societal progress. —Jenna Wortham CONTENTS Also by Roger McNamee Title Page Copyright Dedication Epigraph Prologue 1 The Strangest Meeting Ever 2 Silicon Valley Before Facebook 3 Move Fast and Break Things 4 The Children of Fogg 5 Mr.

The Most Powerful Idea in the World: A Story of Steam, Industry, and Invention

by

William Rosen

Published 31 May 2010

Crafts, “Macroinventions, Economic Growth, and ‘Industrial Revolution’ in Britain and France,” Economic History Review 58, no. 3, 1995. One estimate has the Netherlands with GDP per capita of $2,130 in 1700 and $1,838 in 1820, expressed in 1990 U.S. dollars. 30 In 1789, the year of the Revolution Melvin Kranzberg, “Prerequisites for Industrialization,” in Kranzberg and Pursell, eds., Technology in Western Civilization. 31 By the same year, however Crafts, “Macroinventions, Economic Growth, and ‘Industrial Revolution’ in Britain and France.” 32 Thus, in part because of lower interest rates Kranzberg, “Prerequisites for Industrialization.” 33 Watt was simultaneously a brilliant engineer Pacey, Maze of Ingenuity. 34 Among other things, the project provided Diderot E.

Geek Heresy: Rescuing Social Change From the Cult of Technology

by

Kentaro Toyama

Published 25 May 2015

Ellul could see no easy solution: “It is not a matter of getting rid of it, but, by an act of freedom, of transcending it. How is this to be done? I do not yet know.”21 Not Good, Not Bad, Not Neutral Utopians and skeptics have catchy rhetoric, but most reasonable people can see that the truth is neither Star Trek nor Brave New World. It’s probably a mixture of both. Melvin Kranzberg, a historian of technology, embraced technology’s apparent contradictions. “Technology,” he wrote in 1986, “is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.”22 This enigmatic statement captures what is probably the most common view among scholars of technology today: Its outcomes are context-dependent.

The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom

by

Evgeny Morozov

Published 16 Nov 2010

“Symbols Do Not Create Meaning—Activities Do; or, Why Symbolic Anthropology Needs the Anthropology of Technology.” Anthropological Perspectives on Technology (2001): 77-86. ———. “Technological Dramas.” Science, Technology & Human Values 17, no. 3 (1992): 282. Pool, Ithiel de Sola. Technologies of Freedom. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983. Post, Robert C. “Missionary: An Interview with Melvin Kranzberg.” American Heritage of Invention & Technology 4, no. 3 (1989). ———. “No Mere Technicalities: How Things Work and Why It Matters.” Technology and Culture 40, no. 3 (1999): 607-622. Postman, Neil. “Informing Ourselves to Death.” Speech at the German Informatics Society, October 11, 1990. Pursell, C.

The State and the Stork: The Population Debate and Policy Making in US History

by

Derek S. Hoff

Published 30 May 2012

Myrick Freeman III (New York: W. W. Norton, 1973), 205–11. 38. Richard A. Easterlin, “[Comments on] Thurow and Singer Papers,” in Economic Growth Controversy, ed. Weintraub, Schwartz, and Aronson, 203. 39. Wilfred Beckerman, In Defence of Economic Growth (London: Jonathan Cape, 1974). 40. For example, see Melvin Kranzberg, “Can Technological Progress Continue to Provide for the Future?” in Economic Growth Controversy, ed. Weintraub, Schwartz, and Aronson, 74–75. 41. Richard Zeckhauser, “The Risks of Growth,” in No-Growth Society, ed. Olson and Landsberg, 103–18, quotation on 109. 42. Cited in Garrett Hardin, The Ostrich Factor: Our Population Myopia (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 14.

Chief Engineer

by

Erica Wagner

Bridge to the Future: A Centennial Celebration of the Brooklyn Bridge. New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1984. Landau, Sarah Bradford, and Carl, W. Condit. Rise of the New York Skyscraper 1865–1913. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996. Latimer, Margaret, Brooke Hindle, and Melvin Kranzberg, eds. Bridge to the Future: A Centennial Celebration of the Brooklyn Bridge. New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1984. Latimer, Margaret. Two Cities: New York and Brooklyn the Year the Great Bridge Opened. Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Educational & Cultural Alliance, 1983. Lopate, Philip, ed.

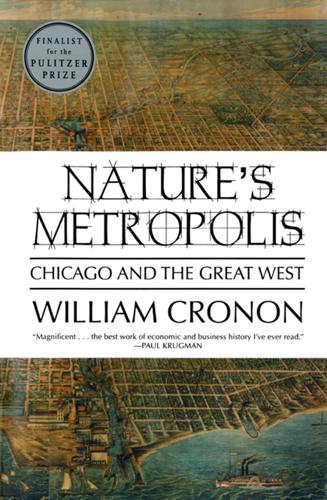

Nature's Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West

by

William Cronon

Published 2 Nov 2009

Kohlmeyer, “Lumber Distribution and Marketing,” in Davis, Encyclopedia of Forest History, 365–70. Historically, Mississippi Valley standards had evolved from those of Chicago, so in an indirect sense Chicago did contribute to the eventual adoption of uniform grading standards. 109.Carl W. Condit, “Buildings and Construction,” in Melvin Kranzberg and Carroll W. Pursell, Jr., eds., Technology in Western Civilization, vol. 1 (1967), 370. See also Walker Field, “A Re-examination into the Invention of the Balloon Frame,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 2, no. 4 (Oct. 1942): 3–29, which discusses the forerunners of Taylor’s church; and Frank Alfred Randall, History of the Development of Building Construction in Chicago (1949).