Moscow, December 25th, 1991

by Conor O'Clery · 31 Jul 2011 · 449pp · 127,440 words

of the Soviet Union, 1995—1991, president of the Soviet Union, 1990—1991 Gorbacheva, Irina, daughter of Mikhail and Raisa Gorbachev Gorbacheva, Raisa, wife of Mikhail Gorbachev Grachev, Andrey, Gorbachev’s press secretary Grachev, Pavel, army general, sided with Yeltsin in August coup Grishin, Viktor, Moscow party chief, 1967—1985 Kalugin,

…

highest levels (and out of sight of the public) by shouts, tears, reminiscences, and melodrama. It climaxes in a final act of surrender by Mikhail Gorbachev to Boris Yeltsin, two extraordinary men who despised each other and whose interaction shaped modern Russia. In reconstructing the events of this midwinter day, I

…

Sergey Yulyevich Witte in his resignation letter as prime minister in 1906 During his six years and nine months as leader of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev is accompanied everywhere by two plainclothes colonels with expressionless faces and trim haircuts. They are so unobtrusive that they often go unnoticed by the president

…

Soviet Union remains a nuclear superpower. This all changes on December 25, 1991. At 7:00 p.m., as the world watches on television, Mikhail Gorbachev announces that he is resigning. The communist monolith known as the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics is breaking up into separate states. He has no

…

are two contrasting figures whose baleful interaction has changed the globe’s balance of power. It is the culmination of a struggle for supremacy between Mikhail Gorbachev, the urbane, sophisticated communist idolized by the capitalist world, and Boris Yeltsin, the impetuous, hard-drinking democrat perceived as a wrecker in Western capitals.

…

stagnated and then collapsed. The center lost control. On December 25, 1991, the country that defeated Hitler’s Germany simply ceases to exist. In Mikhail Gorbachev’s words, “One of the most powerful states in the world collapsed before our very eyes.” It is a stupendous moment in the story of

…

collapse of the USSR will mark the “end of history,” with the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government. Mikhail Gorbachev created the conditions for the end of totalitarianism, and Boris Yeltsin delivered the death blow. But neither is honored in Russia in modern times as

…

president’s office to record the final hours. The only televised interviews given by the great Russian rivals are to U.S. news channels. Mikhail Gorbachev considers himself a personal friend of President Bush, who in the end tried to help him sustain a reformed Soviet Union. Boris Yeltsin courts the

…

world. There is a clue, however, in Pravda. In a single paragraph on page one, the Communist Party newspaper notes, without comment, that President Mikhail Gorbachev will make a major announcement, live on state television, before the day is out. CHAPTER 2 DECEMBER 25: SUNRISE The heavy snow on the spruce

…

right arm. The wrinkles on her once porcelain complexion reveal the torment of watching her husband shrink in stature day by day. To Raisa, Mikhail Gorbachev is a man of destiny. Indeed many superstitious people have interpreted the distinctive birthmark on his head as an omen. But Mikhail and Raisa themselves

…

morning he has many matters to contemplate, some pleasant, some less so. Today he will emerge triumphant from his long and nasty feud with Mikhail Gorbachev. He acknowledges to himself that the motivations for many of his actions are embedded in his bitter conflict with the Soviet president. Just recently his

…

sensed the dangers and the need for improvement. That was why they had turned to the youngest and most energetic comrade in the top ranks, Mikhail Gorbachev. Born on March 2, 1931, in a village on the fertile steppes of southern Russia, Gorbachev was an earnest communist from his teenage days.

…

atop the Kremlin towers, replacing the copper two-headed eagles, symbols of imperial Russia, which were there in prerevolutionary times. Before entering his office Mikhail Gorbachev leaves the television crew and slips into a small room off the corridor, where his hairdresser, a young woman, is waiting to give him his

…

, he feels, “the environment itself is trying to eject us.” CHAPTER 5 THE STORMING OF MOSCOW Less than a year after he took office, Mikhail Gorbachev summoned Communist Party leaders from all over the Soviet Union to a great congress in the Kremlin. As Moscow city boss, Boris Yeltsin saw to

…

. He undermined the demoralized USSR government by first withholding Russian taxes and then taking ownership of Soviet government ministries and the currency mint. All that Mikhail Gorbachev is left with are titles, a small staff, and the nuclear suitcase. Before Gorbachev’s glasnost, the newspapers were dull, mendacious, and heavily censored.

…

Cuéllar to regard as official agents of the Russian Federation all the diplomats who until that day were Soviet representatives. Only three years ago, Mikhail Gorbachev dazzled the General Assembly with his sweeping vision of a new world order for the twenty-first century that would be regulated by the two

…

President Herzog, and the red flag with hammer and sickle is hoisted over the ancient Russian Compound in Jerusalem. This anomaly arises from a promise Mikhail Gorbachev made two months previously, when he still had some authority, to his Israeli counterpart, Yitzhak Shamir, that he would restore Soviet-Israeli relations broken

…

past the Kievsky Railway Station, around Luzhniki sports stadium, back northeast by Gorky Park, and around the ramparts of the Kremlin two miles distant, where Mikhail Gorbachev is also grabbing a quick lunch and fighting fatigue and the onset of influenza as he prepares for the speech that will mark his transition

…

from Moscow party chief to the junior post of first deputy chairman of the state committee for construction. CHAPTER 9 BACK FROM THE DEAD Mikhail Gorbachev’s warning to Boris Yeltsin in November 1987 that he would never let him into politics again left the former Moscow party chief with a

…

in control of himself.”6 CHAPTER 13 DICTATORSHIP ON THE OFFENSIVE In the wake of the Russian parliament’s declaration of sovereignty in June 1990, Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin had the option of trying to destroy each other or of entering into a political alliance. Something drastic had to be

…

Radio Rossiya, the voice of Yeltsin’s parliament, which had been granted a frequency in December. It had carried factual reports from Lithuania that infuriated Mikhail Gorbachev personally, according to Yeltsin’s radio controller, Oleg Poptsov. Kravchenko protested that shutting it down would cause a scandal. Gorbachev insisted that it be restricted

…

him there, Yeltsin found, “exceeded all my expectations.” CHAPTER 14 DECEMBER 25: MIDAFTERNOON By three o’clock in the afternoon of December 25, 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev is able at last to relax. Everything is ready. There is nothing more to be done in preparation for his farewell address. Ted Koppel and

…

Kremlin office, now ceremonial residence of President Medvedev. Author CHAPTER 18 DECEMBER 25: DUSK With less than sixty minutes left before his resignation address, Mikhail Gorbachev is at last mentally and physically ready. His speech has been printed out for him in large letters to read on air. He is satisfied

…

want to destroy the elected council. The shock therapy Yeltsin is applying to the ailing Russian economy was mooted more than a year earlier when Mikhail Gorbachev flirted with, then abandoned, a five-hundred-day plan to convert the floundering command system to a market economy. One of its authors, Grigory

…

whitewashed Hall of Meetings, where a drugged and distressed Yeltsin was brought from his hospital bed four years ago to be shamed by party leader Mikhail Gorbachev for daring to challenge his leadership and privileges. He is working there with Jean Foglizzo, who arrived in Moscow shortly before as representative of the

…

presence of any Russian journalists or TASS photographers. Neither were there any other Western journalists. Tom greeted me and said to please hang around as Mikhail Gorbachev would talk to CNN after the televised speech. I soon found out it was going to be his resignation speech.” Liu squats in front

…

. “Gorbachev says to them, ‘Nyet, nyet!’”3 “We were about to go live on Russian television and around the world with the resignation of Mikhail Gorbachev, the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and the conveyance of power to Boris Yeltsin,” recalled Johnson. “And I am standing one person away from Gorbachev

…

plan. CHAPTER 23 THE DEAL IN THE WALNUT ROOM The details of the transition of power were worked out during a nine-hour encounter between Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin two days before the Soviet president gave his resignation address on the evening of December 25, 1991.1 After the conspiracy

…

on March 11, 1985, the day after the death of Soviet leader Konstantin Chernenko, that the Politburo of the Communist Party agreed to make Mikhail Gorbachev general secretary of the party and undisputed leader of the Soviet Union. Sitting beneath alabaster chandeliers at the end of the long teakwood table with

…

replacing its Marxist heart.” He believes that the end of the Cold War was made possible because of the bold brand of leadership practiced by Mikhail Gorbachev and President Ronald Reagan. “That Christmas Day, the unimaginable happened,” he wrote. “The Soviet Union disappeared. Without a fight, without a war, without a

…

nuclear button.” All that remains for him “is to clear out some personal effects, some papers.” But Boris Yeltsin has not finished tormenting his rival. Mikhail Gorbachev, like everyone else, expects that the Soviet flag will continue flying over the Senate dome until December 31. Russian and world media were told specifically

…

DECEMBER 27: TRIUMPH OF THE PLUNDERERS Just before 8 a.m. on Friday, December 27, a little over a day and a half after Mikhail Gorbachev announced he was ceasing his activities as president of the USSR, Russian president Boris Yeltsin leaves his apartment at 54 Second Tverskaya-Yamskaya Street, as

…

they stride purposefully along the red runner in the corridor and burst into the anteroom of the presidential office to confront the receptionist on duty. Mikhail Gorbachev has not yet arrived. He has an appointment at 11 a.m. in the presidential office with a group of journalists from the Japanese

…

nuclear nations and in light of Iran’s nuclear ambitions, the hands are moved forward again to six minutes to midnight.) Freed from presidential responsibilities, Mikhail Gorbachev helps Raisa in the evening to put their new homes in order. “We were forced to move to different lodgings within twenty-four hours,”

…

later, after the broadcast of a documentary about ethnic conflict in the Caucasus, which annoys him. The rivals rushed to bring out self-serving biographies: Mikhail Gorbachev—Memoirs and Boris Yeltsin’s Zapiski Prezidenta (Notes of the President), published in English as The Struggle for Russia. Yeltsin gets a $450,000

…

members leap to their feet and give a prolonged standing ovation when he declares, “By the grace of God, America won the Cold War.” Mikhail Gorbachev is deeply offended. Bush’s triumphalism feeds into the perception, already widespread in Russia, that the former Soviet president is to blame for the loss

…

a country in which everyone can feel a citizen.” Varennikov walks free after all charges are dropped and claims that his acquittal is proof of Mikhail Gorbachev’s guilt. In 2008, a year before he dies, the former general presents the case in favor of Stalin in a popular nationwide television

…

Cemetery. Putin, then in the second of two four-year terms as president, declares the day of his funeral a national day of mourning. Mikhail Gorbachev goes to the burial and offers faint praise, extending his condolences “to the family of a man on whose shoulders rested many great deeds for

…

; together with the life of Boris Yeltsin, a piece of his own life had been torn away.” Two years later, at age seventy-eight, Mikhail Gorbachev announces that he is returning to politics with the creation of a new political party, the Independent Democratic Party of Russia, which he cofounds with

…

78. 10 Palazchenko, My Years with Gorbachev and Shevardnadze, 289. 11 Ibid., 189. 12 Beschloss and Talbott, At the Highest Levels, 224-226. 13 Burlatsky, Mikhail Gorbachev-Boris Yeltsin, 41. 14 Brown, The Gorbachev Factor, 102. 15 Chernyaev, My Six Years with Gorbachev, 280. 16 Beschloss and Talbott, At the Highest Levels

…

Nancy Reagan, 400-403,443-446. 11 Bush and Scowcroft, A World Transformed, 6. 12 Gorbacheva, I Hope, 7. 13 Ibid., 180. 14 Dougary, “Mikhail Gorbachev.” 15 Muratov, “Mikhail Gorbachev.” 16 Grachev, Final Days, 187. Chapter 15: Hijacking Barbara Bush 1 Mickiewicz, Changing Channels, 96-97. 2 Shane, Dismantling Utopia, 180. 3 Colton, Yeltsin

…

Raisa’s diary of the coup, 817-824. 7 Dobbs, Down with Big Brother, 391. 8 Bush and Scowcroft, A World Transformed, 532. 9 Muratov, “Mikhail Gorbachev.” 10 Bechloss and Talbott, At the Highest Levels, 444-445. 11 Remnick, Lenin’s Tomb, 495. 12 Khasbulatov, The Struggle for Russia, 170-184.

…

Shakhnazarov, Tsena Svobody, 309. 7 Chernyaev, 1991, diary entry for December 28, 1991. 8 Androunas, “A Letter from Moscow.” 9 Gorbachev, Memoirs, 866. 10 Muratov, “Mikhail Gorbachev.” 11 Chernyaev, 1991, diary entry for December 27, 1991. 12 Gorbacheva, I Hope, photograph. Chapter 29: The Integrity of the Quarrel 1 Martin, “Oleg Looks

…

“I Never Lied to Her, I Couldn’t Now.” 17 Steele, “Russians Say Sorry.” 18 Nemtsov, Ispoved Buntarya, 57. 19 Sandle, Gorbachev, 274. 20 Dougary, “Mikhail Gorbachev.” 21 Putin with Gevorkyan, Timakova, and Kolesnikov, First Person, 94. 22 Interview with BBC, October 28, 2010. BIBLIOGRAPHY Alexandrov, Mikhail. Uneasy Alliance: Relations Between Russia

…

Brzezinski, Zbigniew, and Paige Sullivan, eds. Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States: Documents, Data, and Analysis. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1997. Burlatsky, Fyodor. Mikhail Gorbachev-Boris Yeltsin: Skhvatka [Fight]. Moscow: Sobraniye, 2008. Bush, George, and Brent Scowcroft. A World Transformed. New York: Knopf, 1998. Chernyaev, Anatoly. Byl li u Rossii

…

: Times Books, 1995. Doder, Dusko. Shadows and Whisper: Power Politics Inside the Kremlin from Brezhnev to Gorbachev. New York: Random House, 1986. Dougary, Ginny. “Mikhail Gorbachev: The Man Who Changed the World.” Times (London), September 5, 2009. www.ginnydougary.co.uk/2009/09/07/the-man-who-changed-the-world/ Dunlop

…

Moran, John P. From Garrison State to Nation-State: Political Power and the Russian Military Under Gorbachev and Yeltsin. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2002. Muratov, Dmitry. “Mikhail Gorbachev: I Too Could Have Reigned to My Heart’s Content.” Novaya Gazeta, February 17, 2011. Murray, Donald. A Democracy of Despots. Boulder: Westview Press, 1996

The Last Empire: The Final Days of the Soviet Union

by Serhii Plokhy · 12 May 2014

President George H. W. Bush of the United States, the cautious and often humble leader of the Western world, whose backing of Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev and insistence on the security of the nuclear arsenals prolonged the existence of the empire but also ensured its peaceful demise; Boris Yeltsin, the boorish

…

fall of the Soviet Union, many of the principals in my story have published their memoirs. These include books by George H. W. Bush, Mikhail Gorbachev, Boris Yeltsin, and Leonid Kravchuk, as well as the recollections of their advisers and other participants. While the stories told by eyewitnesses and participants in

…

by suspicion,” read a speech prepared by the president’s staff for the signing of a new treaty to reduce nuclear arsenals. “That year, Mikhail Gorbachev assumed leadership of the Soviet Union, put many monumental changes into motion. He began instituting reforms that basically changed the world. And in the United

…

to describe dissidents. In the Foreign Ministry, Kozyrev was one of the young diplomats who slowly but surely pushed their bosses, Eduard Shevardnadze and Mikhail Gorbachev included, to go on from a broadly defined policy of glasnost to a public embrace of freedom of speech and human rights as internationally recognized

…

, it appeared from Yeltsin’s analysis, might fail militarily but succeed politically. The key figure deciding the fate of the coup might again be Mikhail Gorbachev. In the previous few days, Yeltsin had managed to expose the illegality of the coup and establish his own legitimacy by demanding Gorbachev’s release

…

Cold War superpowers that had competed in the Middle East for decades, funding and arming opposing sides in the Arab-Israeli conflict. George Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev served as official cosponsors of the conference. “President Bush and President Gorbachev request your acceptance of this invitation,” read the letter addressed to potential participants

…

international crisis—the invasion of Kuwait by Saddam Hussein’s Iraq a few months earlier. In Paris, responding to a direct request from President Bush, Mikhail Gorbachev agreed to cosponsor a resolution of the United Nations Security Council authorizing the use of force against Saddam Hussein. Gorbachev overruled his hard-line advisers

…

from office by British voters. Now there were well-grounded fears that Madrid could become the last international conference of another heavyweight in international politics—Mikhail Gorbachev. “Reports [[arrived]] recently that he might not be around long,” recorded Bush in his diary on the eve of his departure for Madrid. “The

…

.’ Watching the live broadcast with my colleagues, I felt that they, like me, were surprised Gorbachev had pulled it off.”38 George Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev at a press conference after signing the START1 agreement on the reduction of nuclear arsenals. Gorbachev managed to persuade his military to agree to unprecedented

…

Bush Presidential Library and Museum) Time is up. Russian prime minister Ivan Silaev and future Ukrainian president Leonid Kravchuk check their watches as a worried Mikhail Gorbachev looks on. In the fall of 1991 Gorbachev found it increasingly difficult to deal with the two largest Soviet republics. Kremlin, Moscow, 1991. (ITAR

…

occasion of Gorbachev’s resignation and declare American victory in the Cold War. (George Bush Presidential Library and Museum) V. VOX POPULI 13 ANTICIPATION MIKHAIL GORBACHEV WAS SITTING in his office at the government resort of Novo-Ogarevo. It was the afternoon of November 25, eleven days after the previous meeting

…

no announcement at all.18 ON NOVEMBER 30, three days after the White House leak and the day before the Ukrainian referendum, President Bush called Mikhail Gorbachev to explain the turn in American policy, of which Gorbachev was already aware. It was a conversation neither leader was looking forward to. When

…

after the signing of the Belavezha Agreement, Boris Yeltsin arrived at the Kremlin in a heavily guarded procession of automobiles. He was coming to see Mikhail Gorbachev, the president of the now allegedly defunct Soviet Union. Yeltsin’s bodyguards were prepared for the worst. Their chief, Colonel Aleksandr Korzhakov, had a

…

Kremlin and reverberated throughout the world, Michael R. Beschloss and Strobe Talbott, two distinguished American foreign policy pundits, boarded a plane for Moscow to interview Mikhail Gorbachev. The invitation had come from people in Gorbachev’s immediate circle. Beschloss, the author of several books on the American presidency, and Talbott, a foreign

…

a party crasher from whom everyone wanted to distance himself.40 17 THE BIRTH OF EURASIA ON DECEMBER 17, THE DAY JAMES BAKER left Moscow, Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin met to discuss the transition of power from Union to Commonwealth authorities. “The presidents agreed that the process of managing the

…

Prime Minister John Major of Britain, and, half an hour before his resignation speech, Hans-Dietrich Genscher, the German foreign minister. In his own memoirs, Mikhail Gorbachev would put a more positive spin on his last supper at the Kremlin: “Together with me were the closest friends and colleagues who shared with

…

though the electoral process. The outcome of the competition between the popularly elected president of Russia, Boris Yeltsin, and the president of the USSR, Mikhail Gorbachev, appointed to his position by parliament—a struggle that reached its crescendo in the last months of 1991—shows the decisive power of electoral politics

…

over the main actors of the drama reconstructed in this book. Mikhail Gorbachev unleashed a reform that showed the predilection of modern revolutions for eating their own children. If the French Revolution was an inspiration to the

…

Bush, “State of the Union Address,” January 28, 1992. C-SPAN http://www.c-spanvideo.org/program/23999-1 2. “Statement on the Resignation of Mikhail Gorbachev as President of the Soviet Union,” December 25, 1991, Bush Presidential Library, Public Papers, http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/research/public_papers.php?id=3790&year

…

Beschloss and Talbott, At the Highest Levels, 415. 13. Beschloss and Talbott, At the Highest Levels, 411–412; “Memorandum of Conversation. Extended Bilateral Meeting with Mikhail Gorbachev of the USSR, July 30, 1991,” Bush Presidential Library, Memcons and Telcons, http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/research/pdfs/memcons_telcons/1991-07-30—Gorbachev%20

…

[1].pdf. 14. Strobe Talbott, “Mikhail Gorbachev and George Bush: The Summit Goodfellas,” Time, August 5, 1991. 15. Beschloss and Talbott, At the Highest Levels, 405–406. 16. Jane’s Strategic

…

Politbiuro TsK KPSS po zapisiam Anatoliia Cherniaeva, Vadima Medvedeva, Georgiia Shakhnazarova (1985–1991) (Moscow, 2000), 695–696. 18. “Memorandum of Conversation. Extended Bilateral Meeting with Mikhail Gorbachev of the USSR, July 30, 1991,” Bush Presidential Library, Memcons and Telcons, http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/research/pdfs/memcons_telcons/1991-07-30—Gorbachev%20

…

in Moscow: Bush and Gorbachev Sign Pact to Curtail Nuclear Arsenals, Join in Call for Mid-East Talks,” New York Times, August 1, 1991. 27. Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (New York, 1995), 624. 28. Gorbachev, Memoirs, 624; Cherniaev, Sovmestnyi iskhod, 968–969. 29. Internal Points for Bessmertnykh Meeting, July 28, 1991, James

…

PA, 1997), 305–306; “Dmitriy Timofeyevich Yazov,” The Trip of President Bush to Moscow and Kiev, July 30–August 1, 1991, Bush Presidential Library. 4. Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (New York, 1995), 624–625; Palazhchenko, My Years, 300–301; Michael R. Beschloss and Strobe Talbott, At the Highest Levels: The Inside Story of

…

Levels, 103–104. 25. Gates, From the Shadows, 503; Bush and Scowcroft, A World Transformed, 142–143; Colton, Yeltsin, 172. 26. “Luncheon with President Mikhail Gorbachev of the USSR,” July 30, 1991, Bush Presidential Library, Memcons and Telcons, http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/research/pdfs/memcons_telcons/1991-07-30—Gorbachev%20

…

: The Plot Against the Jewish Doctors, 1948–1953 (New York, 2004), 313–325; Medvedev, Chelovek za spinoi, 147–148; Nikolai Zen’kovich, Mikhail Gorbachev, zhizn’ do Kremlia (Moscow, 2001), 587. 12. Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (New York, 1995), 631; Valentin Varennikov, Nepovtorimoe (Moscow, 2001), vol. 6, pt. 3; Valerii Boldin, Krushnie p’edestala, Shtrikhi

…

21. Dunlop, “The August 1991 Coup and Its Impact on Soviet Politics,” 111; Stepankov and Lisov, Kremlevskii zagovor, 186–187; Krasnoe ili beloe, 251. 22. Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (New York, 1995), 632–640; Anatolii Cherniaev, Sovmestnyi iskhod. Dnevnik dvukh ėpokh, 1972–1991 gody (Moscow, 2008), 982–983; Stepankov and Lisov, Kremlevskii zagovor

…

141–142; Dunlop, “The August 1991 Coup and Its Impact on Soviet Politics.” 23. Bush and Scowcroft, A World Transformed, 531–532; “Telecon with President Mikhail Gorbachev of the USSR,” August 21, 2011, Bush Presidential Library, Memcons and Telcons, http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/research/pdfs/memcons_telcons/1991-08-21—Gorbachev.pdf

…

po zapisiam Anatoliia Cherniaeva, Vadima Medvedeva, Georgiia Shakhnazarova (1985–1991) (Moscow, 2000), 497–498; Vadim Medvedev, V komande Gorbacheva. Vzgliad iznutri (Moscow, 1994), 199–200; Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (New York, 1995), 641. 5. “Press-konferentsiia prezidenta SSSR,” Pravda, August 23, 1991; V Politbiuro TsK KPSS, 497–498. 6. “Rossiiskii trikolor, kak

…

vol. 1, Normativnye akty. Ofitsial’nye soobshcheniia, ed. S. M. Shakhrai (Moscow, 2009), 863; Chugaev and Shcheporkin, “Pravitel’stvo uvoleno, parlament prodolzhaet rabotat’,” 4. 23. Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (New York, 1995), 649–651; Boris Yeltsin, The Struggle for Russia, trans. Catherine A. Fitzpatrick (New York, 1994), 108; Soiuz mozhno bylo sokhranit’, 317

…

Debate over the Union; Nicholas Burns to Ed Hewett, “Response to the Soviet Embassy on the USSR Borders,” April 1, 1991, ibid.; George Bush to Mikhail Gorbachev, draft of August 27, 1991, Bush Presidential Library, Presidential Records, National Security Council, Nicholas R. Burns and Ed A. Hewett Series, USSR Chronological Files:

…

Weapons,” September 27, 1991, Bush Presidential Library, Public Papers, http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/research/public_papers. php?id=3438&year=1991&month=9; Telcon with Mikhail Gorbachev, president of the USSR, September 27, 1991, Bush Presidential Library, Memcons and Telcons, http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/research/pdfs/memcons_telcons/1991-09-27—Gorbachev

…

Scowcroft, A World Transformed, 544–545; Cherniaev, Sovmestnyi iskhod, 990; Pankin, The Last Hundred Days, 107; Bush and Scowcroft, A World Transformed, 547; “Telecon with Mikhail Gorbachev, President of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics,” October 5, 1991, Bush Presidential Library, Memcons and Telcons, http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/research/pdfs/memcons_telcons

…

1994), 219. 9. Gaidar, Dni porazhenii i pobed, 253. 10. Ibid., 256–259, 261–264. 11. Aven and Kokh, “El’tsin sluzhil nam!” 12. Ibid.; Mikhail Gorbachev, Poniat’ perestroiku (Moscow, 2006), 347. 13. Georgii Shakhnazarov, Tsena svobody. Reformatsiia Gorbacheva glazami ego pomoshchnika (Moscow, 1993), 281–282; Soiuz mozhno bylo sokhranit’, 323–324

…

10. 7. Anatolii Cherniaev, Sovmestnyi iskhod. Dnevnik dvukh ėpokh, 1972–1991 gody (Moscow, 2008), 995–996, 1004; Pankin, The Last Hundred Days, 230–232. 8. Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (New York, 1995), 663; “Telcon with Prime Minister Felipe Gonzalez of Spain,” August 19, 1991, Bush Presidential Library, Memcons and Telcons, http://bushlibrary.tamu

…

Izvestiia, November 29, 1991; S. Tsikora, “Ukraina: za den’’ do vystradannoi voli,” Izvestiia, November 29, 1991; Cherniaev, Sovmestnyi iskhod, 1028–1029. 21. Telcon with President Mikhail Gorbachev of the USSR, November 30, 1991, Bush Presidential Library, Memcons and Telcons, http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/research/pdfs/memcons_telcons/1991-11-30—Gorbachev.pdf

…

285; Kravchenko, “Belarus’ na rasput’e.” 32. Kebich, Iskushenie vlast’iu, 202–203. 33. Evgenii Shaposhnikov, Vybor. Zapiski glavnokomanduiushchego (Moscow, 1993), 125–127. 34. Ibid.; Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (New York, 1995), 659; Shakhrai, “Nam udalos’”; Gaidar, “Za riumkoi”; Gaidar, Dni porazhenii i pobed, 148–150; “Belovezhskoe ėkho,” NTV, December 11, 2011. 35

…

, 2000), 736–739; “M. Gorbachev o situatsii v strane i o sebe,” Izvestiia, December 12, 1991; Palazhchenko, My Years, 352. 16. Nikolai Portugalov, Memo to Mikhail Gorbachev, December, 1991, Gorbachev Foundation Archive, fond 5, no. 10866.1. 17. Cherniaev, Sovmestnyi iskhod, 1036; “Gorbachev brosaet vyzov ‘Slavianskomu Soiuzu,’” Izvestiia, December 10, 1991.

…

SEAZ,” Izvestiia, December 19, 1991; Soiuz mozhno bylo sokhranit’, 488–492. 21. Anatolii Cherniaev, Sovmestnyi iskhod. Dnevnik dvukh ėpokh, 1972–1991 gody (Moscow, 2008), 1037; Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (New York, 1995), 660. 22. Boris El’tsin, “My perezhili tragicheskii ėksperiment,” Rossiiskaia gazeta, December 19, 1991. 23. “Kakie rabochie i predstavitel’nye organy

…

25–26. 9. Pavel Palazhchenko, My Years with Gorbachev and Shevardnadze: The Memoir of a Soviet Interpreter (University Park, PA, 1997), 364–366; “Telecon with Mikhail Gorbachev, President of the Soviet Union,” December 25, 1991, Bush Presidential Library, Memcons and Telcons, http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/research/pdfs/memcons_telcons/1991-12-25

…

populiaren. Po krainei mere v Moskve,” Nezavisimaia gazeta, December 19, 1991. 13. Cherniaev, Sovmestnyi iskhod, 1042–1043; Evgenii Shaposhnikov, Vybor. Zapiski glavnokomanduiushchego (Moscow, 1993), 136; Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (New York, 1995), 671–672; Soiuz mozhno bylo sokhranit’, 507; Palazhchenko, My Years, 366–367; O’Clery, Moscow, 231–237. 14. O’Clery, Moscow

…

Gorbachev,” Bush Presidential Library, Presidential Records, National Security Council, Nicholas R. Burns Series, Chronological Files: December 1991, no. 1. Cf. “Statement on the Resignation of Mikhail Gorbachev as President of the Soviet Union,” December 25, 1991, Bush Presidential Library, Public Papers, http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/research/public_papers.php?id=3790&year

…

28, 1991, Bush Presidential Library, Public Papers, http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/research/public_papers.php?id=3792&year=1991&month=12. 22. James Baker to Mikhail Gorbachev, December 29, 1991, James A. Baker Papers, box 110, folder 10. 23. O’Clery, Moscow, 261–262; Cherniaev, Sovmestnyi iskhod, 1043–1044; Grachev, Gorbachev,

…

/conversations/Matlock/matlock-con4.html. 7. George F. Kennan, “Witness to the Fall,” New York Review of Books, November 1995, 7–10, here 7. 8. Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (New York, 1995), 1046. 9. Mark Beissinger, “The Persistent Ambiguity of Empire,” Post-Soviet Affairs no. 11 (1995); Mark R. Beissinger, “Rethinking Empire

Gorbachev: His Life and Times

by William Taubman

Gorbachev speechwriter in Stavropol. GONZÁLEZ, FELIPE Spanish prime minister, 1982–1996. GOPKALO, PANTELEI Maternal grandfather of Gorbachev. GOPKALO, VASILISA Maternal grandmother of Gorbachev. GORBACHEV, ALEKSANDR Mikhail Gorbachev’s brother. GORBACHEV, ANDREI Paternal grandfather of Gorbachev. GORBACHEV, MARIA Mother of Gorbachev. GORBACHEV, SERGEI Father of Gorbachev. GORBACHEV, STEPANIDA Paternal grandmother of Gorbachev. GORBACHEV

…

a feeling that Russian men frequently admit having. But there were also tensions in the extended family. His paternal grandfather, Andrei Gorbachev, was “very authoritarian,” Mikhail Gorbachev remembers. Andrei and Gorbachev’s father, Sergei, grew estranged, even coming to blows on at least one occasion. But Grandfather Andrei, too, had a soft

…

to the point of arrogance. Gorbachev summarized his own outlook this way: “We were poor, practically beggars, but in general I felt wonderful.”5 Young Mikhail Gorbachev with his maternal grandparents, Pantelei and Vasilisa Gopkalo. THE PREHISTORY OF THE STAVROPOL area where Gorbachev was raised can be traced from the first millennium

…

at least he could return to the capital. The plenum released Yefremov from his Stavropol post and unanimously ratified the selection, made in Moscow, of Mikhail Gorbachev as his successor. The USSR consisted of fifteen republics. Russia, by far the largest, contained eighty-three regions or provinces, dominated by regional party

…

average age was over seventy, November 7, 1980. Left to right: Mikhail Solomentsev, Vladimir Dolgikh, Viktor Grishin, Pyotr Demichev, Mikhail Suslov, Konstantin Chernenko, Leonid Brezhnev, Mikhail Gorbachev, Nikolai Tikhonov, Yuri Andropov, Andrei Kirilenko, Andrei Gromyko. Gorbachev concentrated on his own job—agriculture. The 1978 harvest seemed a fine one, record-breaking, in

…

of the Warsaw Pact’s Standing Consultative Committee, June 11–16, 1988. Left to right clockwise around the table: Erich Honecker, Wojciech Jaruzelski, Nicolae Ceauşescu, Mikhail Gorbachev, Gustáv Husák, Todor Zhivkov. EARLY ON, GORBACHEV’S West European strategy didn’t seem much clearer. His predecessors had hoped to drive a wedge between

…

. Post, “Assessing Leaders at a Distance: The Personality Profile,” in The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003), 83. 17 Mikhail Gorbachev, “Slishkom chasto proshchal,” Novaia gazeta, December 25, 2003, in Karen Karagez’ian and Vladimir Poliakov, eds., Gorbachev v zhizni (Moscow: Ves’ mir, 2016), 64–

…

Narratives and Their Relations to Psychosocial Adaptation in Midlife Adults and Students,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 27, no. 4 (April 2001): 474–85. 3 Mikhail Gorbachev, Zhizn’ i reformy, 2 vols. (Moscow: Novosti, 1995), 1:57. 4 Don P. McAdams, The Person: An Introduction to Personality Psychology (Fort Worth, TX:

…

M. Zdravomyslova, executive director of the Gorbachev Foundation, October 18, 2015, Moscow. 46 Gorbachev, Naedine s soboi, 34. 47 Gorbachev, Zhizn’, 1:45; see also Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (New York: Doubleday, 1995), 28. 48 Gorbachev, Zhizn’, 1:42. 49 Ibid., 43; Gorbachev, Memoirs, 28; Gorbachev, Naedine s soboi, 37; Valentina Lezvina, “

…

zemliakom,” 53. 71 Gorbachev, Zhizn’, 1:51. 72 Kuchmaev, Kommunist s bozhei otmetinoi, 26. 73 Gorbachev, Zhizn’, 1:51; Lezvina, “Razgovor s zemliakom,” 53. 74 Mikhail Gorbachev and Zdeněk Mlynář, Conversations with Gorbachev: On Perestroika, the Prague Spring, and the Crossroads of Socialism, trans. George Shriver (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002

…

; Gorbachev’s talk at George Mason University, March 25, 2009. 79 Gorbachev, Zhizn’, 1:52. 80 Ibid. 81 Brown, Gorbachev Factor, 26–27; Zenkovich, Mikhail Gorbachev, 35. 82 Zenkovich, Mikhail Gorbachev, 35; Lezvina, “Razgovor s zemliakom,” 53. 83 Author’s interview with former Gorbachev classmate, name unknown, July 6, 2005, Krasnogvardeisk, Russia. 84 Kuchmaev

…

Mlynář, Nightfrost in Prague, 25–26. 64 Gorbachev, Zhizn’, 1:66. 65 Ibid., 66–67; Mlynář, Nightfrost in Prague, 27. 66 Gorbachev, Zhizn’, 1:68; Mikhail Gorbachev, “My prosto byli drug dlia druga. Vsiu zhizn’,” Obshchaia gazeta, November 29, 1999. 67 Mamardashvili recollections in Raisa Gorbacheva: Shtrikhi, 18–39. 68 Gorbachev, Naedine

…

Drugoe litso (Moscow: “Respublika,” 1996). 54 Author’s interviews with Ivan Zubenko, July 7, 2005, August 1, 2008, Stavropol. 55 Grigory Gorlov, quoted in Zenkovich, Mikhail Gorbachev, 158. 56 Author’s interview with Nikolai Paltsev, July 5, 2005, Stavropol. 57 Author’s interview with Vitaly Mikhailenko, July 8, 2005, Zheleznovodsk; Mikhailenko, Kakim

…

64 Gorbachev, Memoirs, 131. 65 Gorbachev, Zhizn’, 1:213; Gorbachev, Memoirs, 131–32. 66 Gorbachev, Zhizn’, 1:214–16. 67 Ibid., 218–22; Vitaly Marsov, “Mikhail Gorbachev: Andropov ne poshel by daleko v reformatsii obshchestva,” Nezavisimaia gazeta, November 11, 1992. 68 Cherniaev, Moia zhizn’ i moe vremia, 443–48. 69 Markus Wolf

…

lomat’ cherez koleno, po-kovboiski,” Obshchaia gazeta, April 4, 1996. 96 Gorbachev, Poniat’ perestroiku, 56, 58. 97 Grachev, Gorbachev, 131; Marina Zavada and Yurii Kulikov, “Mikhail Gorbachev: My s Raisoi byli priviazanny drug k drugu na smert’,” Izvestiia, January 12, 2007, http://izvestia.ru/news/320650; also see Bobrova, “Posledniaia ledi.” 98

…

Chernyaev, My Six Years with Gorbachev, 23. 71 Gorbachev, Zhizn’, 2:311–12. 72 Savranskaya, Blanton, and Zubok, Masterpieces of History, 137. 73 Transcript of Mikhail Gorbachev’s Conference with CC CPSU Secretaries, March 15, 1985, ibid., 217–19. 74 See Svetlana Savranskaya, “The Logic of 1989: The Soviet Peaceful Withdrawal from

…

Juli 1990,” in Küsters and Hofmann, Deutsche Einheit, 1342. 79 Spohr and Reynolds, Transcending the Cold War, 221. 80 Aleksandr Galkin and Anatolii Cherniaev, eds., Mikhail Gorbachev i germanskii vopros: Sbornik dokumentov, 1986–1991 (Moscow: Ves’Mir Izdatelstvo, 2006), 495–503; Zelikow and Rice, Germany Unified, 335–38. 81 Beschloss and Talbott

…

Braithwaite’s diary entry, September 14, 1990, in Braithwaite, “Moscow Diary, 1988 to 1992,” 201. 99 Cited in Brutents, Nesbyvsheesia, 425. 100 Galkin and Cherniaev, Mikhail Gorbachev i germanskii vopros, 563. 101 Including grants to support the continuing presence of Soviet troops in East Germany, their withdrawal to the USSR, and their

…

273. 114 Gorbachev, Zhizn’, 2:214–15. 115 Chernyaev’s diary, October 23, 1990, entry, in Sovmestnyi iskhod, 883–84. 116 Gorbachev, Zhizn’, 2:215; “Mikhail Gorbachev—Nobel Lecture,” Nobelprize.org, accessed February 7, 2015, http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1990/gorbachev-lecture.html. CHAPTER 16: TO THE COUP

…

Sovetskii pisatel’, 2001). 2 Anatoly Chernyaev diary, September 13 entry, in Sovmestnyi iskhod, 758; Chernyaev, My Six Years with Gorbachev, 167. 3 Personal communication from Mikhail Gorbachev via Pavel Palazhchenko, January 14, 2016. 4 Chernyaev’s diary, August 3, 1991, entry, in Sovmestnyi iskhod, 969. 5 Raisa Gorbachev’s diary, August 4

…

1993), 204; Amy Knight, Spies without Cloaks: The KGB’s Successors (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996), 19; Vladislav Manakhov, “Valentin Pavlov: ‘Esli khotite sam Mikhail Gorbachev byl i chlenom GKChP,” Pravda, April 12, 1996. 34 John B. Dunlop, “The August 1991 Coup and Its Impact on Soviet Politics,” Journal of Cold

…

98, 207–65. 45 Grachev, Gorbachev, 381, 386. CHAPTER 18: FINAL DAYS: AUGUST–DECEMBER 1991 1 Gorbachev: Izbrannyi (sbornik) (Moscow: Novaia gazeta, 2011), 25–26; Mikhail Gorbachev, Posle kremlia (Moscow: Ves’ mir Izdatelstvo, 2014), 346. 2 Gorbachev: Izbrannyi (sbornik), 26. 3 Excerpt from Chernyaev’s diary, in Raisa: Vospominaniia, 156. 4 Press

…

www.gorby.ru/en/. 4 Natali’ia Zelnorova, “Ia nauchilas’ prosto zhit’,” in Raisa: Vospominaniia, 318. 5 Gorbachev, Posle kremlia, 31, 346; Zavada and Kulikov, “Mikhail Gorbachev”; Vladimir Malevannyi, “Molitva bez svechei,” Nezavisimaia gazeta, September 10, 1999, 168 edition, sec. 9, http://www.gorby.ru/gorbacheva/publications/show_25914/; recollections of Aleksandr

…

-Shakh, “Raisa Gorbacheva: Ia nikogda,” ibid., 160. 35 “Mne nikto ne strashen,” Obshchaia gazeta, May 16, 1996. 36 Gorbachev, Posle kremlia, 110. 37 Valerii Vyzhutovich, “Mikhail Gorbachev: K prezidentskim vyboram nuzhno sozdat’ shirokuiu koalitsiiu demokraticheskikh sil,” Izvestiia, December 28, 1995. 38 Marina Shakina, “ ‘V 1991 godu ia byl slishkom samouveren,’ ” Nezavisimaia gazeta

…

, December 12, 1995. 39 Vyzhutovich, “Mikhail Gorbachev.” 40 “Stranu nel’zia lomat’ cherez koleno, po-kovboiski.” 41 “Mne nikto ne strashen.” 42 Ibid. 43 Krementsova, “Liubimaia zhena,” in Raisa: Vospominaniia, 168. 44

…

“Posledniaia ledi,” in Raisa: Vospominaniia, 290. 52 Author’s interview with Luydia Budyka, August 3, 2008, Stavropol. 53 Chiesa and Cucurnia, “Edinstvennaia,” 252–53. 54 Mikhail Gorbachev, Naedine s soboi (Moscow: Grin strit, 2012), 233. Translation here and below draws on working English translation by Pavel Palazhchenko. 55 Author’s interview with

…

fortitude, respected Mikhail Sergeyevich, and to Raisa Maksimovna, courage as she battles her illness and a speedy recovery.” 63 Cited ibid. 64 Zavada and Kulikov, “Mikhail Gorbachev.” 65 Gorbachev, Naedine s soboi, 235–37. 66 Chiesa and Cucurnia, “Edinstvennaia,” 254. 67 Gorbachev, Naedine s soboi, 12–13; author’s interview with

…

. Honestly, I don’t want to live.” Vitaly Mansky, Gorbachev: After the Empire, 2001. 71 Eroshok, “Irina Virganskaia-Gorbacheva,” 116. 72 Zavada and Kulikov, “Mikhail Gorbachev.” 73 “Mikhail Gorbachev: Zhenit’sia ia ne sobiraius’.” 74 Author’s interview with Muratov, May 12, 2013, New York City. 75 As conveyed to former ambassador Matlock, who

…

9, 2007; Irina Gorbachev’s remarks, quoted in Gorbachev, Posle kremlia, 240–41. 94 Lezvina, “Razgovor s zemliakom,” 58. 95 “Soured” cited by Steve Rosenberg, “Mikhail Gorbachev Denounces Putin’s ‘Attack on Rights,’ ” BBC News Europe, March 7, 2014, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-21695314; Gorbachev, Posle kremlia, 267, 269

…

Times, 1992, http://www.nytimes.com/1992/01/29/us/state-union-transcript-president-bush-s-address-state-union.html?pagewanted=all. 104 Anna Beligzhanina, “Mikhail Gorbachev: ‘Ia rad, chto Krym prisoedinilsia k Rossii,’ ” Komsomol’skaia pravda, March 18, 2014, http://msk.kp.ru/print/26207/3093031; Nechepurenko, “Gorbachev on Russia

…

and Ukraine”; Andrei Arkhangelsii, “Mikhail Gorbachev: ‘Nado izmenit’ atmosferu’,” Ogonek, February 2, 2015. 105 Schepp and Sandberg, “I Am Truly and Deeply Concerned.” 106 Author’s interviews with Gorbachev, October 19

…

, 311; Zubok cites N. N. Kozlova, Gorizonty povsednevnosti sovetskoi epokhi: Golosa iz khora (Moscow: Institute of Philosophy, 1996). 3 Vinogradov, “The Paradox of Mikhail Gorbachev,” in Millennium Salute to Mikhail Gorbachev on His 70th Birthday, 46. 4 Jeremi Suri, “To Get Big Things Done We Should Strip Demands on the President,” Dallas Morning Star

…

soveta SSSR, 1990. Devlin, Kevin. Some Views of the Gorbachev Era. Radio Free Europe Research, 1985. RAD Background Report. Galkin, Aleksandr, and Anatolii Cherniaev, eds. Mikhail Gorbachev i germanskii vopros: Sbornik dokumentov, 1986–1991. Moscow: Ves’ mir, 2006. Gorbachev: Izbrannyi (sbornik). Moscow: Novaia gazeta, 2011. Gorbachev, Mikhail. Izbrannye rechi i stat’

…

. Stavropol. OTHER INTERVIEWS A. Benediktov interview with Gorbachev. February 15, 2009. Radio station “Ekho Moskvy.” Cartledge, Bryan. British Diplomatic Oral History Project. 2007. Telen’, Liudmila. “Mikhail Gorbachev: ‘Chert poberi, do chego my dozhili!’ ” Radio svoboda October 22, 2009. Radio station “Ekho Moskvy.” Other interviews are contained in various articles in the Soviet

…

cheloveka, 2006. ———. Neizvestnyi Andropov: Politicheskaia biografiia Iuriia Andropova. Moscow: Prava cheloveka, 1999. Medvedev, Zhores. Gorbachev. New York: W. W. Norton, 1986. A Millennium Salute to Mikhail Gorbachev on His 70th Birthday. Moscow: R. Valent, 2001. Mlynář, Zdeněk. Nightfrost in Prague: The End of Humane Socialism. Translated by Paul Wilson. New York: Karz

…

Free Press, 1991. Zelikow, Philip, and Condoleezza Rice. Germany Unified and Europe Transformed: A Study in Statecraft. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997. Zenkovich, Nikolai. Mikhail Gorbachev: Zhizn’ do Kremlia. Moscow: Olma-Press, 2001. Zubkova, Elena. Russia after the War: Hopes, Illusions and Disappointments, 1945–1957. Translated by Hugh Ragsdale. Armonk, NY

…

October 19, 1991. Berg, Steve. “A Calm Capital Contrasts with a Frantic, Fidgeting Gorbachev-Crazed Twin Cities.” Minneapolis Star Tribune, June 1, 1990. Braterskii, Aleksandr. “Mikhail Gorbachev predstavil svoiu novuiu knigu.” Gazeta.ru, November 21, 2014. Brown, Archie. “The Change to Engagement in Britain’s Cold War Policy.” Journal of Cold War

…

svechei.” Nezavisimaia gazeta, September 10, 1999, 168 edition, sec. 9. http://www.gorby.ru/gorbacheva/publications/show_25914/. Manakhov, Vladislav. “Valentin Pavlov: ‘Esli khotite, sam Mikhail Gorbachev byl i chlenom GKChP.” Pravda, April 12, 1996. Maraniss, David, and John Lancaster. “Chilly Weather, Warm Welcome in the Twin Cities.” Washington Post, June 4

…

, 1990. Marsov, Vitaly. “Mikhail Gorbachev: Andropov ne poshel by daleko v reformatsii obshchestva.” Nezavisimaia gazeta, November 11, 1992. McAdams, Don P., Jeffrey Reynolds, Martha Lewis, Allison H. Patten, and Phillip

…

Life Narratives and Their Relations to Psychosocial Adaptation in Midlife Adults and Students.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 27, no. 4 (April 2001): 474–85. “Mikhail Gorbachev: Zhenit’sia ia ne sobiraius’.” Komsomol’skaia pravda. March 2, 2001. http://www.kp.ru/daily/22504/7900/. Mlynář, Zdeněk. “Il mio compagno di

…

vnutrennogo golosa.” Narodoselenie, no. 1 (2006). Roberts, Steven V. “President Charms Students, But His Ideas Lack Converts.” New York Times, June 1, 1988. Rosenberg, Steve. “Mikhail Gorbachev Denounces Putin’s ‘Attack on Rights.’ ” BBC News Europe, March 7, 2014. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-21695314. Rosenblatt, Robert A. “Gorbachev Tempts

…

“Gorby’s Choice.” Wall Street Journal, December 1, 2007. “Writer Admits Yeltsin Source Is Nonexistent.” Washington Post, September 21, 1989. Zavada, Marina, and Yurii Kulikov. “Mikhail Gorbachev: My s Raisoi byli priviazanny drug k drugu na smert’.” Izvestiia, January 12, 2007. http://izvestia.ru/news/320650. Zubok, Vladislav. “New Evidence on the

The End of the Cold War: 1985-1991

by Robert Service · 7 Oct 2015

7. THE SOVIET QUARANTINE 8. NATO AND ITS FRIENDS 9. WORLD COMMUNISM AND THE PEACE MOVEMENT 10. IN THE SOVIET WAITING ROOM PART TWO 11. MIKHAIL GORBACHËV 12. THE MOSCOW REFORM TEAM 13. ONE FOOT ON THE ACCELERATOR 14. TO GENEVA 15. PRESENTING THE SOVIET PACKAGE 16. AMERICAN REJECTION 17. THE STALLED

Post Wall: Rebuilding the World After 1989

by Kristina Spohr · 23 Sep 2019 · 1,123pp · 328,357 words

homeland, Europe is our future. François Mitterrand, 1987 Peace is not unity in similarity but unity in diversity, in the comparison and conciliation of differences. Mikhail Gorbachev, 1991 Politics needs a sense of the possible, also of what is acceptable to others. Helmut Kohl, 2009 Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Epigraph

…

China’s Economic Reach, 2015 Introduction Economic crisis in the Soviet Union … War in the Gulf … Chaos in Yugoslavia … A Stalinist coup against Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev … Mobilisation across the whole Eastern bloc … Soviet invasion of the Balkans … The West calls up reservists and puts civil defence on highest alert … At dawn

…

triangle that particularly mattered was formed by the Soviet Union, the United States and the Federal Republic of Germany: on one level, the political leaders – Mikhail Gorbachev, George H. W. Bush and Helmut Kohl;[5] on another their foreign ministers – Eduard Shevardnadze, James Baker and Hans-Dietrich Genscher.[6] It was within

…

of the Cold War to a new era. Although this was led by the West, and particularly by US president George Bush, the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev was also willing to buy into the process as part of an effort to reorient the Soviet Union’s official ideology towards the ‘common’ values

…

overly focused on the relationship between the two men at the apex of their respective states. Bush, Kohl and other Western leaders all clung to Mikhail Gorbachev rather than engaging with the deeper problems of the unravelling Soviet Union. At the end of 1991, the USSR totally disintegrated, forcing Bush to take

…

was abuzz that evening. Thousands of New Yorkers and tourists lined the streets, cheering, waving and giving thumbs-up signs behind the police barricades as Mikhail Gorbachev rode down Broadway in a forty-seven-car motorcade. Gorbymania in Manhattan Suddenly, in front of the Winter Garden Theater where the musical Cats was

…

back of his limo and saw four attractive women. I knew that his society had not come that far yet in terms of capitalist decadence.’ Mikhail Gorbachev certainly did not share Donald Trump’s ideal of decadence. Nevertheless, he was clearly fascinated by the market economy. Bystander Joe Peters reckoned that Gorbachev

…

his Fourteen Points in 1918 or since Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill promulgated the Atlantic Charter in 1941 has a world figure demonstrated the vision Mikhail Gorbachev displayed.’[20] But others looked behind the occasion and the rhetoric. The Christian Science Monitor, for instance, drew attention to what Gorbachev did not say

…

. Washington, Moscow and Beijing formed a strategic triangle whose dynamics were always in flux. Bush was well aware that, a year before he assumed office, Mikhail Gorbachev had already formally proposed a summit meeting with the Chinese leadership – the first since Khrushchev and Mao had met in 1959 on the brink of

…

forces of democratic protest and communist oppression collided violently and with dramatic global consequences in China’s Forbidden City. * On 15 May, just before noon, Mikhail Gorbachev landed at Beijing’s airport to begin a historic four-day trip to China. Descending the steps of his blue-and-white Aeroflot jet, he

…

Europe. This was a challenge to the Cold War order as a whole – and one that only the two superpowers could address. After pussyfooting around Mikhail Gorbachev for half a year, George H. W. Bush had no choice but to engage. Chapter 2 Toppling Communism: Poland and Hungary The 4th of June

…

the heart of Europe. Chapter 4 Securing Germany in the Post-Wall World The 3rd of December 1989. It was almost incredible. George Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev, the leaders of the United States and the Soviet Union, sitting together in Malta, relaxed and joking, in a joint press conference at the end

…

-four international leaders gathered at the Kléber International Conference Centre near the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. Top of the list were George Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev, but Kohl, Mitterrand and Thatcher were also there; likewise Havel from Czechoslovakia and Mazowiecki from Poland. All came with their foreign ministers or some other

…

had party coups in the Soviet Union and elections in Britain. Now it seemed to be the other way round.’[207] During the Paris summit, Mikhail Gorbachev was also absorbed by problems at home – indeed the very cohesion of the USSR as a unitary state. The Baltic republics, having all made clear

…

decisive and cool under pressure. The other is detached and quick to give in. Foreign Bush can be stubborn about China, deft toward Europe and Mikhail Gorbachev, gutsy in taking out Manuel Noriega. Domestic Bush trades his tax pledge for nothing.[110] Despite all the plaudits about foreign policy, Bush’s 11

…

the hard work we put in on this relationship’, insisting ‘I am anxious that it stays strong. Some criticise us for staying too close to Mikhail Gorbachev.’ But he assured Shevardnadze, ‘We will deal with him with respect and friendship as long as he is president.’[202] Chapter 7 Russian Revolution The

…

guarantee for us. We will keep working in the country and out to keep cooperation going.’ Bush laughed with relief. ‘Sounds like the same old Mikhail Gorbachev, one full of life and confidence. Once you get back we’ll talk about what to work on since our talks in Moscow.’ ‘OK, George

…

before there was an even greater turn to the right or shift into disintegration’. And the way to that was to ‘maintain our relations with Mikhail Gorbachev’ until successfully completing at least the Gulf mission, the START treaty and ensuring that CFE did not unravel.[150] The policy of sticking with Gorbachev

…

at such moments of world-historical transition. Helmut Kohl, the impresario of German unification, articulated a similar view. ‘These are historically significant years,’ he told Mikhail Gorbachev during their Moscow summit in July 1990. ‘Such years come and go. The opportunities have to be used. If one does not act, they will

…

Reagan’s shoes – still seemed the tongue-tied apprentice, overshadowed by the Soviet leader, a global cult figure. By the end of December 1991, however, Mikhail Gorbachev’s political career was over and his country no longer existed, while George Bush appeared the arbiter of the world’s fortunes. In three short

…

-violent revolution’. Soldiers did shoot into the crowds; tanks rolled down boulevards and into the Square, crushing demonstrators under their tracks. Deng Xiaoping was no Mikhail Gorbachev. He had no compunction about using force to keep communism in power in China. And so 4 June 1989 came to mark a historic divide

…

start in the early months of his presidency, Bush also developed a cordial relationship with his Soviet opposite number: ‘I liked the personal contact with Mikhail Gorbachev,’ he later wrote, ‘I liked him.’[7] As a result, a degree of genuine trust was fostered and this laid the basis for productive statecraft

…

1998 and 29 April 1999, Berlin ‘FCO Witness Seminar: Berlin in the Cold War 1949–1990 & German Unification 1989–1990’. Lancaster House (16 October 2009). ‘Mikhail Gorbachev’s 1988 Address to the UN: 30 Years Later’. SAIS – Johns Hopkins University, Washington DC (6 December 2018). Panel Discussion with Andrei Kozyrev, Pavel Palazhchenko

…

Power and Political Change: Key Issues and Concepts Routledge 2012. For ‘1989’ as the result of ‘reform from above’ by national communist elites sanctioned by Mikhail Gorbachev, see for example Stephen Kotkin with Jan T. Gross Uncivil Society: 1989 and the Implosion of the Communist Establishment Modern Library 2009; Constantine Pleshakov There

…

the Cold War Oxford UP 2014. For a comparison of Soviet and Chinese economic reforms, see Chris Miller The Struggle to Save the Soviet Economy: Mikhail Gorbachev the Collapse of the USSR Univ. of North Carolina Press 2016; Stephen Kotkin ‘Review Essay – The Unbalanced Triangle: What Chinese–Russian Relations Mean for the

…

(89)18), pp. 1–6; and Office Memorandum Christensen to Whittome 4.10.1990 pp. 1–2 Back to text 9. Geir Lundestad ‘“Imperial Overstretch”, Mikhail Gorbachev and the End of the Cold War’ CWH 1, 1 (2000) pp. 1–20; Arne Westad The Global Cold War p. 379 Back to text

…

Chernyaev – Notes from a Meeting of the Politburo 31.10.1988 Archive of the Gorbachev Foundation Moscow (hereafter AGF) Digital Archive Wilson Center (hereafter DAWC); Mikhail Gorbachev Memoirs Bantam 1997 p. 459; Politburo meeting 24.11.1988, printed in V Politbyuro TsK KPSS. Po zapisyam Anatoliya Chernyaeva, Vadima Medvedeva, Georgiya Shakhnazarova, 1985

…

. 433 Back to text 14. See video of UN speech c-span.org/video/?5292-1/gorbachev-united-nations Back to text 15. Address by Mikhail Gorbachev at the UN General Assembly Session (Excerpts) 7.12.1988 CWIHP Archive. See also video of UN speech c-span.org/video/?5292-1/gorbachev

…

-united-nations; and video of ‘Mikhail Gorbachev’s 1988 Address to the UN: 30 Years Later’, Panel Discussion with Andrei Kozyrev, Pavel Palazhchenko, Thomas W. Simons Jr, and Kristina Spohr at SAIS

…

INF treaty. Indeed, Soviet officials now denied that his departure reflected unhappiness in the military over the cutbacks. Back to text 23. See video of ‘Mikhail Gorbachev’s 1988 Address to the UN: 30 Years Later’ youtube.com/watch?v=Mi6NkWIJuzo Cf. Pavel Palazhchenko My Years with Gorbachev and Shevardnadze: The Memoir

…

the NSRs, which he oversaw, were a ‘stalling exercise’ by the Bush administration vis-à-vis the Kremlin. See his commentry on the video of ‘Mikhail Gorbachev’s 1988 Address to the UN: 30 Years Later’ youtube.com/watch?v=Mi6NkWIJuzo. See for NSR 3, NSR 4, NSR 5 fas.org/irp

…

. Politburo meeting 16.7.1987 ‘Following the trip of the delegation of the Supreme Council to China’, printed in V. Politbyuro TsK KPSS p. 207. Mikhail Gorbachev Perestroika: New Thinking for Our Country and the World Collins 1987 Back to text 72. Shakhnazarov quoted in Sergey Radchenko Unwanted Visionaries: The Sovet Failure

…

, 475; cf. Charles Moore Margaret Thatcher: The Authorised Biography, vol. 2 Allen Lane 2015 pp. 240–1 Back to text 98. Record of Conversation between Mikhail Gorbachev and Margaret Thatcher, 6.4.1989, printed in Svetlana Savranskaya et al. (eds) Masterpieces of History: The Peaceful End of the Cold War in Europe

…

text 127. See Notepad Entry of Teimuraz Stepanov-Mamaladze 17.5.1989 HIA-TSMP: Notepad 15.5.1989 DAWC; and Excerpts from the Conversation between Mikhail Gorbachev and Rajiv Gandhi 15.7.1989 AGF DAWC Back to text 128. ‘1,000,000 Protestors Force Gorbachev to Cut Itinerary: The Center of Beijing

…

The End of the Cold War 1985–1991 Pan Books 2015 p. 385. On Gorbachev–Deng ‘58–85’, see also Excerpts from the Conversation between Mikhail Gorbachev and Rajiv Gandhi 15.7.1989 AGF DAWC Back to text 133. Michael Parks & David Holley ‘30-Year Feud Ended by Gorbachev, Deng: Leaders Declare

…

China–Soviet Ties Are Normalised’ LAT 16.5.1989 Back to text 134. Soviet transcript of meeting between Mikhail Gorbachev and Deng Xiaoping (Excerpts), 16.5.1989 DAWC. For a Chinese version of the record of conversation see also DAWC Back to text 135. Ibid

…

text 147. GHWBPL Telcon of Kohl–Bush talks 15.6.1989 Oval Office p. 1 Back to text 148. See Excerpts from the Conversation between Mikhail Gorbachev and Rajiv Gandhi 15.7.1989 AGF DAWC Back to text 149. State Department Bureau of Intelligence and Research ‘China: Aftermath of the Crisis’ 27

…

Burying Mao: Chinese Politics in the Age of Deng Xiaoping Princeton UP 1996 pp. 18–20 Back to text 167. Excerpts from the Conversation between Mikhail Gorbachev and Rajiv Gandhi 15.7.1989 AGF DAWC Back to text 168. Note by Vladimir Lukin regarding Soviet–Chinese Relations 22.8.1989 GARF f

…

’ NYT 5.7.1989. On the French perspective of Gorbachev’s Paris visit, see Bozo Mitterrand pp. 60–3 Back to text 56. Speech by Mikhail Gorbachev to the Council of Europe in Strasbourg – ‘Europe as a Common Home’ 6.7.1989 Council of Europe – Parliamentary Assembly Official Report 41st ordinary session

…

(1990–1991)’ Revue internationale et stratégique 82 (2011/2) pp. 18–28; Andrei Grachev ‘From the Common European Home to European Confederation: François Mitterrand and Mikhail Gorbachev in Search of a Road to a Greater Europe’ in Bozo et al. (eds) Europe and the End of the Cold War. For an external

…

text 201. Kohl cited in Apple Jr ‘East and West Sign Pact to Shed Arms in Europe’ Back to text 202. Speech by Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev to the Second Summit of CSCE Heads of State or Government in Paris 19.11.1990 osce.org/mc/16155?download=true Back to text

…

a Soviet Role in Middle East Peace Talks’ NYT 11.9.1990 Back to text 99. ‘Joint News Conference of President Bush and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev in Helsinki, Finland’ 9.9.1990 APP. See also Bill Keller ‘Junior Partner No More, Gorbachev Raises Role to Major Player in Crisis’ NYT 11

…

property’, see Michael Dobbs ‘Gorbachev Rebukes Estonia on Soviet “Crisis”’ WP 28.11.1988. See also Brown Seven Years p. 203 Back to text 17. Mikhail Gorbachev Sobranie Sochinenii vol. 14 (April–June 1989) Ves’ Mir 2009 p. 295 Back to text 18. See IMFA-AWP JSSE B3/F3 Teresa Ter-Minassian

…

.1991; Francis X. Clines ‘Rally Takes Kremlin Terror and Turns It into Burlesque’ NYT 29.3.1991 Back to text 137. Matlock Autopsy p. 471; Mikhail Gorbachev The August Coup: The Truth and the Lessons HarperCollins 1991 p. 13; Entries 14.3.1991 and 20.3.1991 The Diary of Anatoly S

…

. 1–8 Back to text 182. Remarks at the Arrival Ceremony in Moscow 30.7.1991 APP; The President’s News Conference with Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev in Moscow 31.7.1991 APP Back to text 183. Soviet Record of Main Content of Conversation between Gorbachev and Bush, First Private Meeting, Moscow

…

here pp. 876–7. No US transcript of this discussion has been released Back to text 184. The President’s News Conference with Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev in Moscow 31.7.1991 APP. Cf. Keith Badger ‘Soviet Trade Favor Costs US Little’ NYT 31.7.1991 Back to text 185. TLSS doc

…

APP Back to text 4. ‘Dawn of a New Era’ NYT 2.2.1992 Back to text 5. Bush’s Statement on the Resignation of Mikhail Gorbachev as President of the Soviet Union 25.12.1991 APP Back to text 6. The President’s News Conference 26.12.1991 APP Back to

…

B. 350 List of Illustrations Here Gorbymania in Manhattan, 7 December 1988 (Richard Drew/AP/Shutterstock) Here George H. W. Bush with Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, Governors Island, 7 December 1988 (Courtesy Ronald Reagan Library) Here George and Barbara Bush in the Forbidden City, 25 February 1989 (Diana Walker/The LIFE

The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and Its Dangerous Legacy

by David Hoffman · 1 Jan 2009 · 719pp · 209,224 words

the center of the drama are two key figures, both of them romantics and revolutionaries, who sensed the rising danger and challenged the established order. Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the Soviet Union, abhorred the use of force and championed openness and "new thinking" in hopes of saving his troubled country

…

this situation their actions were perfectly justified because in accordance with international regulations the aircraft was issued with several notices to land at our airfield." Mikhail Gorbachev, a younger, rising star among the aging Politburo members, said, "The aircraft remained above our territory for a long time. If it went off track

…

tons of anthrax a year. 28 ---------- 6 ---------- THE DEAD HAND In the final weeks of his life, Andropov had few visitors. One of them was Mikhail Gorbachev, the youngest member of the Politburo, who had been Andropov's protege. They met for the last time in December 1983. "When I entered his

…

most promising candidates was a member of the younger generation, a man with a broader view--Mikhail Gorbachev.27 ---------- PART ---------- TWO ---------- 8 ---------- "WE CAN'T GO ON LIVING LIKE THIS" Five weeks after Reagan was reelected, Mikhail Gorbachev and his wife, Raisa, were driven from London through rolling English farmland to Chequers, the elegant

…

Reagan what Gorbachev had said to her: "Tell your friend President Reagan not to go ahead with space weapons."13 To understand the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev, who, with Reagan, would change the world in the years ahead, we must first reach back a half century into the tumultuous events that confronted

…

televised speech on March 23, 1983. [Ray Lustig/Washington Post] The nuclear accident at Chernobyl in April 1986 was a turning point for Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. [Reuters] Marshal Sergei Akhromeyev, chief of the Soviet General Staff, played a key role in Gorbachev's drive to slow the arms race. [RIA Novosti

…

, devilishly challenging, often defying a chance to declare absolute success. In trying to prevent something, the most consequential and terrifying metric was failure. ---------- EPILOGUE ---------- When Mikhail Gorbachev shook hands for the first time with Ronald Reagan at Geneva on November 19, 1985, the two superpowers had amassed about sixty thousand nuclear warheads

…

from several interviews as well as his eventful eight years in office, and my understanding further enriched by publication of his memoir and private diary. Mikhail Gorbachev granted two interviews for this book, and I benefited from his memoir and extensive writing and public speaking. Anatoly Chernyaev gave me his personal recollections

…

thousand tons, Penza five hundred tons and Stepnogorsk three hundred tons, for a total of eighteen hundred a year. CHAPTER 6: THE DEAD HAND 1 Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (New York: Doubleday, 1996), p. 152. 2 Angus Roxburgh, The Second Russian Revolution (London: BBC Books, 1991), p. 17; and Archie Brown, The Gorbachev

…

where otherwise noted, Margaret Thatcher's recollections are from her memoir, The Downing Street Years (New York: HarperCollins, 1993), pp. 452-453, and 459-463. Mikhail Gorbachev's recollections are chiefly from his Memoirs in English and in Russian, Zhizn' i reformi, two vols. (Moscow: Novosti, 1995). In some cases, as noted

…

, 1996), p. 329. 2 Reagan diary, April 19, 1985. Reagan acknowledged in his memoir, "I can't claim that I believed from the start that Mikhail Gorbachev was going to be a different sort of Soviet leader." Reagan, An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990), p. 614. 3 Reagan, An American

…

Smolny speech was two days later. Serge Schmemann, "First 100 Days of Gorbachev: A New Start," New York Times, June 17, 1985, p. 1. 4 Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (Moscow: Novosti, 1995), p. 201. 5 Chernyaev, p. 33, and diary May 22, 1985. 6 Chernyaev, p. 29, and diary April 11, 1985. 7

…

was published in 2006, V Politburo TsK KPSS: Po Zapisyam Anatolia Chernyaeva, Vadima Medvedeva, Georgiya Shakhnazarova, 1985-1991 (Moscow: Alpine Business Books, 2006). 16 See Mikhail Gorbachev: Selected Speeches and Articles(Moscow: Progress, 1987), p. 341. 17 National Security Decision Directive 196, Nov. 1, 1985. 18V Politburo, p. 32. 19United States Nuclear

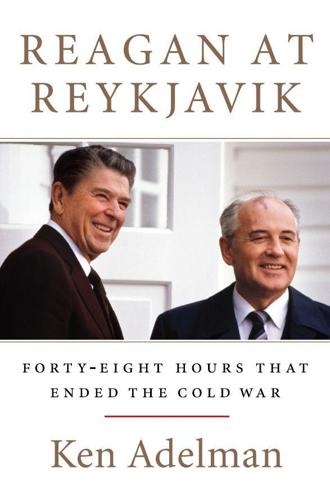

Reagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold War

by Ken Adelman · 5 May 2014 · 372pp · 115,094 words

island, in a reputedly haunted house with rain lashing against its windowpanes, where they experience the most amazing things. The summit between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev on October 11 and 12, 1986, was like nothing before or after—with its cliffhanging plot, powerful personalities, and competing interpretations over the past quarter

…

interpretation will be laid out in the final chapter, bolstered by such standard methods of substantiation as expert witnesses, evidence, and logic. One such witness, Mikhail Gorbachev, has been clear over the years. U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz, at Reagan’s side during Reykjavik, had a conversation with the last

…

home, he was ready to take on the world. That morning he was headed to Iceland, of all places, to negotiate about nuclear weapons with Mikhail Gorbachev. Negotiating was something Reagan loved to do, something he felt he was good at doing, something he most wanted to do with a Soviet leader

…

during Politburo meetings and then made assignments to its members. In essence, he was Gorbachev’s all-purpose notetaker and task-tracker. IN OCTOBER 1986 MIKHAIL Gorbachev was, like Ronald Reagan, at the height of his power. But unlike Reagan, who had been dubbed “the Teflon President” and who appeared worry-free

…

in 1986.” It was not an auspicious start to a critical weekend. Friday, October 10, 1986 Keflavik International Airport, Iceland, 1:18 p.m. When Mikhail Gorbachev stepped off his plane, a sudden gust of wind on that raw, blustery day made him grab his gray fedora and falter a bit, almost

…

beside me, and said, “It’s no deal.” With iconic moments in history, it is often hard to reconstruct exactly what happened. Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev leaving that small room—after more than ten and a half hours of what Gorbachev later called “debates that became very pointed in their last

…

of church bells across Berlin. Bernstein called it “a historic moment sent from above.” (Zentralbild ADN/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images) On June 10, 2004, Mikhail Gorbachev unexpectedly appeared in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol to pay his last tribute to Ronald Reagan, lying in state. After standing a few

…

on the legitimacy of the Soviet system suddenly seemed like small potatoes. Ronald Reagan was no longer the main person undermining the regime’s foundations. Mikhail Gorbachev was. WHILE TENSIONS WERE WAXING in Moscow, they were waning in Washington. Iran-Contra had stripped Ronald Reagan of the sparkle he had in the

…

voice of God—announced: “The president of the United States and the general secretary of the Communist party of the Soviet Union.” Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev entered the East Room side by side, having strolled down the long red carpet of the Cross Hall adorned with the haunting portrait of John

…

of that era, was sublime in understatement when acknowledging “little understanding in the Warsaw Pact for Hungary’s decision.” THE NEXT MONTH, ON October 7, Mikhail Gorbachev went to Berlin to help celebrate the fortieth anniversary of that Communist regime. Gorbachev greeted the seventy-seven-year-old East German leader, Erich Honecker

…

unhappy past. There were problems aplenty. But given the one problem they had faced for more than forty years, these were problems they welcomed. MEANWHILE, MIKHAIL GORBACHEV WAS facing problems he did not welcome. Much to his historic glory, the Soviet leader allowed the 1989 revolutions to take their course without sending

…

fourth paragraph, and several sentences into it at that, when I read the most shocking news of all: “Marshal Sergei Akhromeyev, military adviser to President Mikhail Gorbachev and former armed forces chief of staff, had committed suicide.” Dobbs allocated only two of his twenty-five paragraphs to Akhromeyev, not mentioning that he

…

life. I struggled until the end. AKHROMEYEV 24 AUGUST 1991 Just recently, I learned that there may be a third suicide note, one written to Mikhail Gorbachev, which may be released after Gorbachev’s death. If such a letter exists, it could reveal Akhromeyev’s involvement with the coup and motivation for

…

a classic mystery thriller à la Agatha Christie, then the question naturally arises, “Who done it?” In this case, we know who—Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev. But we are less sure of the “it.” Now, long after the political theater has ended, just how—and how much—did Reykjavik matter? To

…

conference at the Reagan Library entitled “A World Without Nuclear Weapons” featuring statements by the U.N. secretary general, the prime minister of Japan, and Mikhail Gorbachev. The keynoter was, once again, Shultz, who began his talk by asking all those present to give a rousing three cheers for Reagan and what

…

before, lamented what might have been. Their lament raises the fascinating “what if” parlor game known as counter-factual history. What if Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev had signed an agreement eliminating all their nuclear weapons at Reykjavik? In counter-factual history, we can never know. After all, it’s tough enough

…

contention, to which I subscribe, is backed by testimony of key participants and beneficiaries, by logic, and by evidence. First, a bit of expert testimony. Mikhail Gorbachev—as expert a witness as you could get—said explicitly that from Reykjavik sprang the “elimination of the Cold War.” To him, “Reykjavik marked a

…

no one else he would rather be than Ronald Reagan and no role he would rather play than president of the United States. Gorbachev Revisited Mikhail Gorbachev is likewise sui generis. He’s unique by the extent of his being reviled at home and revered abroad and by his being heralded for

…

love.” He fixed those bright eyes on Nancy, and then slowly closed them. She considered it the greatest gift ever. When the news reached Moscow, Mikhail Gorbachev hailed President Reagan for paving “the way for the end of the Cold War.” In New York, Henry Kissinger said simply that “Ronald Reagan ended

…

, and wording for this project—as she has throughout all our projects, including that of sharing a life together. Notes INTRODUCTION 1 “Truly Shakespearean passions”: Mikhail Gorbachev, letter to the prime minister of Iceland, the mayor of Reykjavik, and participants of the seminar on the tenth anniversary of the summit, September 10

…

U.S. Improvised,” Washington Post, February 16, 1987. 2 “wearying and grueling arguments”: Ibid. 2 “no one can continue to act as he acted before”: Mikhail Gorbachev, Reykjavik: Results and Lessons (Moscow, 1990). 3 “No summit since Yalta”: Don Oberdorfer, From the Cold War to a New Era: The United States and

…

. SATURDAY IN REYKJAVIK 82 According to legend: The legend and history are summarized by Astporsdottir from Icelandic sources. 83 wine-colored blotch: Eleanor Hoover, “Whatever Mikhail Gorbachev’s Other Worries, the Birthmark on His Head Isn’t One of Them,” People, November 18, 1985; “Photographs Show Mark on Gorbachev’s Head,” Associated

…

,” University of Virginia, Miller Center, October 13, 1986, http://millercenter.org/president/speeches/detail/5865. 207 The general secretary opened: The speech is contained in Mikhail Gorbachev, Reykjavik: Results and Lessons (Moscow, 1990). All italics in the text are mine, not his. 209 The top administration troika: The figures on U.S

…

president: Taken from Reykjavik newspapers in June 2004, as reported and translated by Astporsdottir. 335 In an op-ed piece for the New York Times: Mikhail Gorbachev, “A President Who Listened,” New York Times, June 7, 2004. 337 nearly a hundred and forty years earlier: Rudolph Bush, “A Time to Remember,” Chicago

…

, “Ronald Reagan 1911–2004: Our Final Hail to the Chief,” Newsday, June 12, 2004. 337 the state funeral: I was startled to read later that Mikhail Gorbachev was there at the funeral, since neither Carol nor I saw him that morning. Otherwise, I would have gone over and greeted him. 337 musical

…

, Todor, 280 About the Author Ken Adelman was President Ronald Reagan’s arms control director. He was at Reykjavik during the 1986 superpower summit with Mikhail Gorbachev, and accompanied President Reagan at three superpower summits in all. He has also served as a U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and as

Chernobyl: The History of a Nuclear Catastrophe

by Serhii Plokhy · 1 Mar 2018 · 465pp · 140,800 words

conflicting political actors in Ukraine—the Ukrainian communist establishment and the nascent democratic opposition—discovered a common interest in opposing Moscow, and especially Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. In December 1991, when Ukrainians voted for their country’s independence, they also consigned the mighty Soviet Union to the dustbin of history—it was

…

. And yet, with the communist religion in crisis, it suddenly appeared to have found a new messiah in a relatively young, energetic, and charismatic leader: Mikhail Gorbachev. This was to be the fifty-four-year-old Gorbachev’s first congress as general secretary of the party, and he was well aware that

…

presented an interesting spectacle whose main features went back to Stalin’s times. At ten in the morning, the party’s Politburo members, led by Mikhail Gorbachev, marched to the podium. Like most people, Briukhanov knew them from their portraits, which were displayed on public buildings all over the Soviet Union. Among

…

interview with Briukhanov appeared in the newspaper without that warning.23 2 ROAD TO CHERNOBYL ON THE evening of March 6, 1986, as the invigorated Mikhail Gorbachev hosted a reception in the Kremlin Palace for the foreign guests of the congress—most of them representatives of communist parties who had come to

…

deliver products to the construction site in a timely fashion. Kyzyma had learned media tactics long before the era of glasnost, or openness, declared by Mikhail Gorbachev and his reformers. In the spring of 1980, Kyzyma and Briukhanov were summoned to Moscow to report to the deputy prime minister of the all

…

that did not matter. Ostensibly, work on the weekend closest to Lenin’s birthday was a volunteer activity, but in reality, party officials demanded it. Mikhail Gorbachev skipped the occasion, as he was on an official visit to the German Democratic Republic, pushing his “acceleration” ideas there, but his compatriots did not

…

:00 a.m. on April 26, awakening the most powerful man in the land, the general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev. The message was that there had been an explosion and fire at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, but the reactor was intact. Gorbachev’s first

…

of April 27 by Vladimir Dolgikh, the Central Committee secretary in charge of the energy sector.10 On the morning of April 28, Dolgikh informed Mikhail Gorbachev and the entire Soviet leadership in person that Unit 4 had been destroyed by the blast and had to be buried. The process had begun

…

to deal with the Chernobyl explosion as well. Original silence about the Chernobyl accident at home and abroad also followed the Ozersk pattern. In 1986, Mikhail Gorbachev, Nikolai Ryzhkov, and their subordinates in Moscow and Kyiv had a model they could follow not only for dealing with the nuclear disaster, but also

…

the imposition of martial law in Poland. Now they were finally being resumed as a result of the first meeting between President Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev in Geneva in December 1985. There the two leaders had sized each other up and decided, despite major ideological and philosophical differences, that they could

…

suspected, the Chernobyl nuclear plant was part of a military-run program.12 On the next day, April 30, Soviet diplomats delivered a message from Mikhail Gorbachev to Ronald Reagan. The message confirmed that the accident had taken place. “They say that a leak of radioactive material has required the partial evacuation

…

was acknowledged, although it was called not a city but a settlement; and the public was assured that radiation levels were being closely monitored. As Mikhail Gorbachev, Nikolai Ryzhkov, and their Politburo colleagues released limited information on the disaster, their main challenge was to balance the desire to maintain a degree of

…

ensembles dressed in traditional Ukrainian costumes and young people carrying portraits of Marx, Engels, and Lenin, as well as photos of Politburo members, starting with Mikhail Gorbachev. The marchers are lightly dressed: it is a warm, sunny morning. Many came with small children; some fathers are seen bearing them on their shoulders

…

agents were busy confiscating leaflets that, in their opinion, contained “tendentious fabrications about the consequences of the accident at the Chernobyl atomic energy station.”31 Mikhail Gorbachev never took responsibility for what happened in Kyiv that day, but he did later admit that holding the parade was a mistake. “Rallies were not

…