Rogue Trader

by Nick Leeson · 21 Oct 2015 · 336pp · 101,894 words

Published by Sphere 978-0-7515-6364-1 Copyright © 1996 Nick Leeson The moral right of the author has been asserted. New Introduction copyright © 2015 Nick Leeson 2: Press Association, 8: Kevin Phillips, 10: Kevin Phillips, 11: Kevin Phillips, 29: Associated Press/Topham, 30: Rex Features, 31: Paul Massey/FSP, 32: Mirror

…

fertile imagination had dreamt the whole thing up… A cracking good read with a brilliant insight into the world of high-powered banking’ Irish News Nick Leeson now lives peacefully on the West Coast of Ireland with his wife Leona and their three children, Kersty, Alex and Mackensey. Nick is an accomplished

…

and corporate governance issues. The team of experienced industry practitioners offer the crucial extension to your own resources that every firm needs. www.riskteam.com nick.leeson@riskteam.com Table of Contents Reviews for Rogue Trader About the Author COPYRIGHT Epigraph Introduction to the 2015 Edition Preface Epigraph PROLOGUE: A Weekend at

…

Conduct Risk and how this can be controlled. Conduct Risk is an amalgam of many things but it is not dissimilar to the problems that Nick Leeson, those before and those after him, presented to the market place. PREFACE T his is the part of the book where you might normally expect

…

. There was no need to whisper, I could hardly hear myself shout. He looked at me and queried: “What size, Nick?” “Any size, Fat Boy!”’ Nick Leeson, General Manager of Baring Futures Singapore June 1992–February 1995 PROLOGUE A Weekend at Kota Kinabalu Saturday 25 February 1995 I t was my birthday

…

nodded and let him draw his own conclusions. ‘It looked that way,’ he smiled with admiration. He was another one who’d been fed the Nick Leeson success story in London, and I couldn’t disappoint him. He was no nearer finding my account than he was a week ago, and he

…

were content to rule their far-flung empires from a calm distance. They needn’t muddy their hands any more. They had people like me, Nick Leeson, twenty-two years old and up from Watford, to do it for them. That was fine by me – I was prepared to get stuck in

…

both… In my view it is critical that we should keep clear reporting lines, and if this office is involved in SIMEX at all, then Nick Leeson should report to Simon Jones and then be responsible for the operations side. If this memo had been taken seriously I would have been installed

…

door frame of his office. ‘Better get back downstairs.’ ‘Fuck!’ I cursed as the lift doors closed behind me. ‘Ash Lewis!’ ‘Can Nick Leeson from Barings please report to reception, Nick Leeson from Barings to reception, please,’ the SIMEX tannoy announced. I straightened my jacket and tie and wiped my hands on my trousers

…

with straightforward systems. Perhaps as a consequence of this both the front and the back office operations are managed and controlled by the General Manager, Nick Leeson. This represents an excessive concentration of powers; companies commonly divide responsibility for initiating, settling and recording transactions among different areas to reduce the possibility of

…

inscrutable silence as Ron stood up and began to talk about the money we were all making. Sure enough, he made particular reference to me. ‘Nick Leeson, whom most of you know and all of you have heard of, runs our operation in Singapore, which I want you all to try to

…

’s Mui Mui for you,’ Linda called out, holding her hand over the mouthpiece, ‘from Coopers & Lybrand.’ This was the call which would kill me. ‘Nick Leeson?’ Her voice was quiet and soft. ‘I’ve been trying to get hold of you. I’m compiling the year-end audit and we’re

…

my birthday. I had to get out of Singapore. I hunched over a desk and looked at the screens. To the outsider I looked like Nick Leeson, the trading superstar who moved the Nikkei this way and that, the gambler with the biggest balls in town. The other dealers would see me

…

buns. The Borneo Post was for sale on the counter. I didn’t expect to see myself on the front cover – but there I was: ‘Nick Leeson, the general manager of Baring (Futures) Singapore, is missing…’ At least there wasn’t a photograph. ‘I’m still hungry,’ I said, unable to sit

…

newspapers now?’ Lisa came back with a Herald Tribune. My photograph was on the front cover. I couldn’t read the story. I just saw ‘Nick Leeson’ and £600 million losses. I wanted to speak to someone on the phone to find out what was going on. I had a mad wish

…

acquired cult status in Frankfurt. I listened to the German one, and almost jumped out of my skin when I heard the disc jockey say ‘Nick Leeson’. It was some kind of dedication. The track was a German song called ‘Geld, Geld, Geld’, and was sung in the way that Monty Python

…

. ‘Let’s not waste time talking about Barings. They’ve got their problems, we’ve got ours. And my God I could clout you one, Nick Leeson. Just you wait until you’re out of here. You’re going to be in such deep shit from me I can’t even tell

Ugly Americans: The True Story of the Ivy League Cowboys Who Raided the Asian Markets for Millions

by Ben Mezrich · 3 May 2004

are fictitious, including “John Malcolm.” I have used the real names of historical figures or those widely reported in the news, such as Joseph Jett, Nick Leeson, and Richard Li. Otherwise, no character in the book is meant to refer specifically to a real-life person. Also, regarding job titles and positions

…

Yale with a crooked smile and thick red hair, said, “It’s you guys, actually. It’s Carney. Nobody can match his profits. Not even Nick Leeson, Barings’s boy in Singapore. He’s supposed to be good, one of the best, but he’s no Dean Carney, and even he knows

…

“Carney’s told me only good things about his boys in Osaka. You’re making him look real good over here. Tokyo’s answer to Nick Leeson.” Carney and Bill grimaced simultaneously at the mention of the legendary Barings trader in Singapore. Carney waved his thin fingers in the air. “Singapore is

…

were revered like professional athletes or movie stars. Like athletes, they were bought and traded and eventually turned into legends by their less successful colleagues. Nick Leeson, Barings’s boy in Singapore. Dean Carney, the biggest player in Tokyo. And Joe Jett, Kidder’s genius on Wall Street. Locked in the back

…

sex in the back of taxicabs. Other than the big three—football, rugby, and sex—there was only one other subject that dominated the office. Nick Leeson, the star trader stationed in Singapore, whose legend was still growing in tune with the size of his trades. For some of the traders, Leeson

…

self-assured. That important. That big a star. 118 | Ben Mezrich What Malcolm didn’t know was that at that very moment smiling, amiable, relaxed Nick Leeson was sitting on more than one billion dollars of losses. Enough to shake the entire financial world and bring Barings, the oldest, most venerable bank

…

or hide losses. Play nice with everyone else in the sandbox, and don’t cut corners. Because if you do, you’ll end up like Nick Leeson, rotting away for six years in some Singapore prison cell.” “You call that bullshit?” I’d asked. “It sounds like some pretty important lessons.” “It

…

gathered around the table, the pressed business suits and carefully combed hair and leather briefcases brimming with training syllabi and course checklists, I wondered if Nick Leeson had ever been forced to attend one of these seminars. Had Barings’s star trader ever sat through a lecture on business ethics, thinking it

…

the psychology behind them. Because this new class of expats needed to understand that it was the psychology that led people like Joe Jett and Nick Leeson down the paths of disaster. The psychology of the high-stakes gambler. The psychology of the adrenaline junkie, the big-time player, who chased the

…

wrong thrill and the wrong high off the wrong goddamn cliff. “By January of 1995,” Danville droned on, “Nick Leeson, Barings’s star trader in Singapore, had accrued more than 1.3 billion dollars in losses, hidden in an error account he’d named 88888

…

blackjack team. I had an intimate knowledge of one of the most successful group of professional card counters in the world. I didn’t know Nick Leeson, but maybe, just maybe, I knew what made him tick. In card counting, there was a concept called the Big Player. The Big Player was

…

that every professional card counter had wagered in all the casinos in the world over the past year, it would pale in comparison to what Nick Leeson—a twenty-seven-year-old kid sitting at a desk in Singapore—had bet on the Nikkei as of January 1995. In many ways, he

…

get that,” Akari said. Malcolm grabbed the receiver, assuming it would be Sears on the other end of the line. To his surprise, it was Nick Leeson. “Malcolm,” he started. The connection was fuzzy but still audible. “You guys got a bit shaken up this morning, didn’t you?” It was the

…

stuck in the Nikkei. I put many of the orders through myself.” Sears shook his head, his hair shivering back and forth. “Mr. X is Nick Leeson. Mr. X is us. That’s our money that got lost in the earthquake. That’s our money. We’re all fucked.” The enormity of

…

’d spent in the clutches of a pair of auditors from the Bank of England just two weeks ago—coincidentally, the day the authorities arrested Nick Leeson as he got off a plane in Frankfurt, Germany. The interrogation room at the Barings office hadn’t been much larger than this elevator. Malcolm

…

lessons he had learned, about derivatives and arbitrage, about selling high and buying low. He thought about Joe Jett and his 350-milliondollar grenade, about Nick Leeson and his 1.3-billion-dollar bomb. He thought about Dean Carney and Bill, riding the Nikkei up and down like it was a Maui

…

would stroll in by seven-thirty. The first week, Carney wore a striped trading-floor jacket to the morning bull session, in twisted homage to Nick Leeson, whose photograph was still being splashed across tabloids in London and Tokyo. After the first week, he’d exchanged the stripes for dark Armani, no

…

raising the stakes, increasing the size of his positions to an almost frightening level. On some days he seemed to be channeling the ghost of Nick Leeson, trading so much Nikkei he was affecting the market as a whole. He hadn’t even realized how hard he was hitting the exchange until

…

answers to give, there were no questions being asked. Because often nobody knew who the clients were or where the money was coming from. Like Nick Leeson, hedge funds all seemed to work for Mr. X. “So it isn’t until the end of the year, when you add up your profits

…

. Malcolm’s name was growing in stature, and his short history in Japan wasn’t hurting, either. Ironically, the fact that he had worked for Nick Leeson, then moved on to become one of Carney’s brightest boys, made for good personal PR. He was becoming known as a hot young gunslinger

…

boss. “Anyway,” Sears remarked, as the chairlift swung back and forth in a manufactured cold breeze, “twenty million on a single trade is something even Nick Leeson would have been quite impressed by. Pacific Century Cyberworks getting added to the Hang Seng Index. A private placement of shares to the tracker fund

Day One Trader: A Liffe Story

by John Sussex · 16 Aug 2009

Alan Dickinson, Terry Crawley, Richard Crawley, David Wenman, Nigel Ackerman, Kevin Thomas, Tony Laporta, Danny Jordan, Mark Green and Roger Carlsson from the floor, also Nick Leeson, Matt Blom and Spencer Oliver. Finally Nick Carew Hunt, James Barr and especially John Foyle from Liffe and all the staff at John Wiley & Sons

…

E S T O R Y | 55 arbitrageurs deal in large volumes to generate a good income. The most infamous arbitrager of them all was Nick Leeson. He was supposed to be using arbitrage to profit from differences in the prices of the Nikkei-225 futures contracts listed on the Osaka Securities

…

when a lad from Watford single-handedly bankrupted one of the world’s most famous banks. The words ‘rogue trader’ are synonymous with one man – Nick Leeson. He is not the first or last man to lose hundreds of millions of dollars on the financial markets. Others have followed similarly destructive paths

…

piece of the jigsaw in the Leeson story has been overlooked in what has been written about the man so far. To truly understand the Nick Leeson story you need to know the Mark Green story. Leeson desperately wanted the image of a ballsy star trader. To him this meant one thing

…

splashed across page seven the next day. ‘Trader loses £ 743,000 in 43 minutes,’ proclaimed the headline. The newspaper suggested that the incident echoed the Nick Leeson rogue trading scandal. The image of barrow boys once again going wild on the financial markets was not good for business. At least things could

Investment: A History

by Norton Reamer and Jesse Downing · 19 Feb 2016

frauds have crippled and even destroyed otherwise well-capitalized financial institutions. While there has been a litany of such episodes, two cases will be explored: Nick Leeson (Barings Bank) and Jérôme Kerviel (Société Générale). The Leeson case will be explored because of its role in the undoing of an old and venerable

…

financial institution, and the Kerviel episode will be discussed because of its sheer size as one of the largest such trading frauds in history. nick leeson and barings bank Nick Leeson was born in 1967 in Watford, England, a working-class town about seventeen miles outside central London. After a short stint as a

…

Fraud by Investment Managers” (working paper, 2011). 88. Stephen J. Brown and Onno W. Steenbeek, “Doubling: Nick Leeson’s Trading Strategy,” Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 9, no. 2 (April 2001): 85–86. 89. Ibid., 86. 90. Nick Leeson, “Biography,” NickLeeson.com, accessed January 2015, http://www.nickleeson.com/biography/full_biography_02.html. 362

…

N. Goetzmann, and Stephen A. Ross. “Survival.” Journal of Finance 50, no. 3 (July 1995): 853–873. Brown, Stephen J., and Onno W. Steenbeek. “Doubling: Nick Leeson’s Trading Strategy.” Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 9, no. 2 (April 2001): 83–99. Buffett, Warren. “The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville.” Hermes (Columbia Business

Lying for Money: How Fraud Makes the World Go Round

by Daniel Davies · 14 Jul 2018 · 294pp · 89,406 words

individual psychology. There are plenty of larger-than-life characters. But there are also plenty of people like Enron’s Jeff Skilling and Baring’s Nick Leeson: aggressively dull clerks and managers whose only interest derives from the disasters they caused. And even for the real craftsmen the actual work is, of

…

the gap, by the way, is to take big risks with the money which hasn’t been stolen yet. This is how ‘rogue’ traders like Nick Leeson tend to expand their concealed losses to levels that blow up banks. But it’s by no means unknown for even a small-time embezzler

…

understands that risk is intrinsic to some part of his or her economic life, but hopes to manage it by delegation to a trusted outsider. Nick Leeson Nick Leeson was luckier than many convicted fraudsters in that he got Ewan McGregor to play him (and Anna Friel to play his wife) in the film

…

tends to suddenly be absent in low-trust societies when a foreign newcomer shows up and starts winning the game at the expense of locals.) Nick Leeson arrived, spent six months sorting through certificates in an office, a further few months hiring lawyers, and managed to turn several million pounds from ‘in

…

of the ‘back office’ record-keeping too. It is no coincidence that this combination of responsibilities is now banned in most financial centres. One of Nick Leeson’s employees, inevitably, made a small(ish) mistake, losing the equivalent of £20,000 in a few minutes by selling a contract when an external

…

, creating the 88888 account was not a false move; it’s a fairly normal thing to do. What made it disastrous was the fact that Nick Leeson, master of the paperwork, was responsible both for administering and reconciling it (in his role as chief of the ‘back office’), making trades that could

…

writing was on the wall, at which point he and his wife tried to escape. A short manhunt ended on the airport tarmac in Frankfurt. Nick Leeson was something of a sad sack compared to lots of major fraudsters. Even if his fraud had worked, all he would have got out of

…

legitimate traders.* The key psychological element is the inability to accept that one has made a mistake; it is not much exaggeration to say that Nick Leeson destroyed a 200-year-old banking dynasty because he didn’t want to say sorry. Leeson did not have an easy life after his fraud

…

at the way Bill Black busted the S&L fraudsters, or the decline of Artur Alves dos Reis, or the failure of Barings to stop Nick Leeson. Let’s start thinking, one last time, about how frauds are made. The fraud triangle In passing at the end of Chapter 8, we started

…

side of the picture, and Inside Job by Stephen Pizzo (McGraw-Hill, 1989) is a fair history of the S&L disaster. Rogue Trader by Nick Leeson (Little, Brown & Co, 1996) is another example of the fraudster autobiography genre, and really needs to be read alongside a more objective history such as

…

down, these charmers would scribble ‘tickets’ and pass them to a runner, whose job it was to take them down to the equivalent of young Nick Leeson, who would then get on the phone to his counterpart to make sure both sides’ understanding of the trade matched up. One gulps, but actually

…

to be ‘Client X’ was Philippe Bonnefoy, a French hedge fund manager working in the Bahamas who had indeed done a lot of business with Nick Leeson. The eventual inquiries made it clear that he had not been involved in any of the fraud, however, and certainly hadn’t taken the massive

Beautiful security

by Andy Oram and John Viega · 15 Dec 2009 · 302pp · 82,233 words

us first look at a breach with the most dire of consequences: bankruptcy. The breach was actually a succession of breaches perpetrated by one individual, Nick Leeson, over a period of four years that resulted in the collapse of Barings Bank and its ultimate sale to the ING Group for one pound

…

-granddaughter of one of the Barings family. Barings was Queen Elizabeth’s personal bank. Born in 1967 as a working class son of a plasterer, Nick Leeson’s life is a tale of rags to riches to rags, and possibly back to somewhat lesser riches. He failed his final math exam and

…

price of the option (Qcall ) is what the buyer pays to the seller. A short straddle is a trading strategy in which a trader—say, Nick Leeson—sells matching put and call options. Note that a long straddle is a strategy in which the trader buys matching put and call options. For

…

outside of their department or outside of their company because they fear being evaluated against their peers as members of the same market ecosystem. Certainly, Nick Leeson’s account and its contribution to metrics such as those described would have merited at least a yellow rating for access management controls in the

Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, Sixth Edition

by Kindleberger, Charles P. and Robert Z., Aliber · 9 Aug 2011

, although the depositors in the bank were made whole.). Similarly, should the Bank of England have rescued Baring Brothers in 1995 after the rogue trader Nick Leeson in its Singapore branch office had depleted the firm’s capital through hidden transactions in option contracts? The question appears whenever a group of borrowers

…

, some individuals will make a big bet in the hope that a successful outcome will provide an escape from what otherwise would be a disaster. Nick Leeson was a modest functionary – one of five or six employees – in the Singapore office of Baring Brothers, the venerable London merchant bank. Leeson traded options

…

used some of the cash obtained from the SFV’s borrowings to support the price of its own stock. That is more or less a Nick Leeson go-for-broke strategy; if the stock price should fall, then the value of the partnerships would decline and they would be ‘under water’. But

…

; the news triggered a series of failures that reverberated in Liverpool, London, Paris, Hamburg, and Stockholm.20 A kind of mid-nineteenth-century version of Nick Leeson. In September 1929 the Hatry empire in London, a set of investment trusts and operating companies in photographic supplies, cameras, slot machines, and small loans

Trend Following: How Great Traders Make Millions in Up or Down Markets

by Michael W. Covel · 19 Mar 2007 · 467pp · 154,960 words

Barings Bank. The failure of Barings Bank is probably the most often cited derivatives disaster. While the futures market had been the instrument used by Nick Leeson to play the zero-sum game [and] someone made a lot of money being short the Nikkei futures Mr. Leeson was buying.”4 It often

…

, perplexed, said no. “I think we’re bust.” “Is this a crank call?” Killian asked. “There’s a really ugly story coming out that perhaps Nick Leeson has taken the company down.”9 126 Trend Following (Updated Edition): Learn to Make Millions in Up or Down Markets Event #1: 2008 Stock Market

…

in finance at Harvard Business School. Only a few years later, despite the significance of what happened, the events have been forgotten. A rogue trader, Nick Leeson, overextended Barings Bank in the Nikkei 225, the Japanese equivalent to the American Dow, by speculating that the Nikkei 225 would move higher. It tanked

…

blinded to any other option. They keep searching for any type of validation to support their analysis even if they are losing money—just like Nick Leeson. Before the Kobe earthquake in early January 1995, with the Nikkei trading in a range of 19,000 to 19,500, Leeson had long futures

Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and Unknowns in the Dazzling World of Derivatives

by Satyajit Das · 15 Nov 2006 · 349pp · 134,041 words

and the strange goings-on in the business. Ordinary men and women do not trouble themselves about this world. Just occasionally, an event such as Nick Leeson and Barings or LTCM spills over into the news. This infrequent appearance underestimates the importance of the industry and its role in finance. Every one

…

ripples from this strange sphere make it into the tabloids or into the nightly news. It is always a disaster, a large loss. For example, Nick Leeson on his way to prison after having bankrupted Barings. The name – LTCM – appeared briefly as its demise threatened the financial system. Derivatives in all their

…

you are fine; if it moves sharply in any direction then you have a problem, it is not easy to straddle a barbed wire fence. Nick Leeson sold a huge straddle on the Japanese stock market just before it fell sharply after the Kobe earthquake – he was strangled. Nick did leave the

…

. In 1991, Joseph Jett, the head of government bond trading, created phantom trades to show fake trading profits. The losses were $210 million. In 1995, Nick Leeson famously lost £900 million on Nikkei/JGB futures and options trading. Leeson did not try to falsify the valuation. It was difficult as futures prices

…

numbers DEFCON 1 157 The bank is bankrupt. You’re fired. You join the speaker circuit, sharing your experiences with other risk luminaries such as Nick Leeson. There was the ‘quick/slow’, ‘smart/dumb’ scale (I got the impression that speaker was a quick/smart). Risk ‘savages’ appeared; in keeping with the

Snakes and Ladders: The Great British Social Mobility Myth

by Selina Todd · 11 Feb 2021 · 598pp · 150,801 words

with no connection to the public sector, and where older strategies for getting on in life had persisted despite the welfare state. Among them was Nick Leeson. In 1985 eighteen-year-old Nick, the son of a Watford plasterer, got a job as a clerk at Coutts bank. Nick’s mother, who

…

.21 And they were expanding. Those upwardly mobile men who got a foothold in the City usually owed it to the creation of new jobs. Nick Leeson carved out a niche for himself in those branches of speculation that were ‘expanding rapidly, and few people really understood how they worked’. This offered

…

the chance to scale the ladder.22 But rising through the financial hierarchy was far harder for those who began life on a lower rung. Nick Leeson observed that men from public schools or with contacts in the banks quickly became traders on the stock exchange floor, which was where ‘the real

…

finance in very small numbers. The City was a macho world where cut-throat competition was strongly encouraged, bolstered by long drinking sessions after work. Nick Leeson, whose idea of a good night out was to ‘get out there and behave like an animal’, could fit in.24 Women could not. The

…

an outlet in the Thatcherite values of competition and risk-taking. Like some of the technocrats of the 1930s and the managers of the 1950s, Nick Leeson prided himself on ‘never talking about my emotions’ or letting them get in the way of his career. His ‘tough’ persona and ‘confidence’ brought him

…

to a working-class background in the 1960s and 70s had never really permeated some of the elite professions they entered. Despite his macho persona, Nick Leeson was careful to ensure ‘nobody knew where I came from or what I did at weekends. I wore my suit and tie and learned fast

…

: Gender at Work in the City of London, Blackwell, 1997, pp. 50–57. 22 ‘Elitism in Britain – breakdown by profession’, Guardian, 28 August 2014. 23 Nick Leeson, Rogue Trader, Sphere, 2015, online edition (no page numbers). 24 Ibid. 25 Nicola Horlick, Can You Have It All?, Pan, 1998, p. 86. 26 Quoted

Start With Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action

by Simon Sinek · 29 Oct 2009 · 261pp · 79,883 words

Paper Promises

by Philip Coggan · 1 Dec 2011 · 376pp · 109,092 words

A Demon of Our Own Design: Markets, Hedge Funds, and the Perils of Financial Innovation

by Richard Bookstaber · 5 Apr 2007 · 289pp · 113,211 words

How Will You Measure Your Life?

by Christensen, Clayton M., Dillon, Karen and Allworth, James · 15 May 2012

Money and Government: The Past and Future of Economics

by Robert Skidelsky · 13 Nov 2018

Trading and Exchanges: Market Microstructure for Practitioners

by Larry Harris · 2 Jan 2003 · 1,164pp · 309,327 words

I.O.U.: Why Everyone Owes Everyone and No One Can Pay

by John Lanchester · 14 Dec 2009 · 322pp · 77,341 words

Trend Commandments: Trading for Exceptional Returns

by Michael W. Covel · 14 Jun 2011

How to Speak Money: What the Money People Say--And What It Really Means

by John Lanchester · 5 Oct 2014 · 261pp · 86,905 words

The London Compendium

by Ed Glinert · 30 Jun 2004 · 1,088pp · 297,362 words

Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making for an Unknowable Future

by Mervyn King and John Kay · 5 Mar 2020 · 807pp · 154,435 words

Ethics in Investment Banking

by John N. Reynolds and Edmund Newell · 8 Nov 2011 · 193pp · 11,060 words

The Bankers' New Clothes: What's Wrong With Banking and What to Do About It

by Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig · 15 Feb 2013 · 726pp · 172,988 words

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk

by Satyajit Das · 14 Oct 2011 · 741pp · 179,454 words

How the City Really Works: The Definitive Guide to Money and Investing in London's Square Mile

by Alexander Davidson · 1 Apr 2008 · 368pp · 32,950 words

Other People's Money: Masters of the Universe or Servants of the People?

by John Kay · 2 Sep 2015 · 478pp · 126,416 words

Adapt: Why Success Always Starts With Failure

by Tim Harford · 1 Jun 2011 · 459pp · 103,153 words

Principles of Corporate Finance

by Richard A. Brealey, Stewart C. Myers and Franklin Allen · 15 Feb 2014

Systematic Trading: A Unique New Method for Designing Trading and Investing Systems

by Robert Carver · 13 Sep 2015

Unknown Market Wizards: The Best Traders You've Never Heard Of

by Jack D. Schwager · 2 Nov 2020

The Unknowers: How Strategic Ignorance Rules the World

by Linsey McGoey · 14 Sep 2019

Making It Happen: Fred Goodwin, RBS and the Men Who Blew Up the British Economy

by Iain Martin · 11 Sep 2013 · 387pp · 119,244 words

The Spider Network: The Wild Story of a Math Genius, a Gang of Backstabbing Bankers, and One of the Greatest Scams in Financial History

by David Enrich · 21 Mar 2017 · 513pp · 141,153 words

Rule Britannia: Brexit and the End of Empire

by Danny Dorling and Sally Tomlinson · 15 Jan 2019 · 502pp · 128,126 words

How I Became a Quant: Insights From 25 of Wall Street's Elite

by Richard R. Lindsey and Barry Schachter · 30 Jun 2007

Liars and Outliers: How Security Holds Society Together

by Bruce Schneier · 14 Feb 2012 · 503pp · 131,064 words

The Greed Merchants: How the Investment Banks Exploited the System

by Philip Augar · 20 Apr 2005 · 290pp · 83,248 words

When Things Start to Think

by Neil A. Gershenfeld · 15 Feb 1999 · 238pp · 46 words

McMafia: A Journey Through the Global Criminal Underworld

by Misha Glenny · 7 Apr 2008 · 487pp · 147,891 words

Inside the House of Money: Top Hedge Fund Traders on Profiting in a Global Market

by Steven Drobny · 31 Mar 2006 · 385pp · 128,358 words

Adaptive Markets: Financial Evolution at the Speed of Thought

by Andrew W. Lo · 3 Apr 2017 · 733pp · 179,391 words

Broke: How to Survive the Middle Class Crisis

by David Boyle · 15 Jan 2014 · 367pp · 108,689 words

After the Music Stopped: The Financial Crisis, the Response, and the Work Ahead

by Alan S. Blinder · 24 Jan 2013 · 566pp · 155,428 words

I Never Knew That About London

by Christopher Winn · 3 Oct 2007 · 395pp · 94,764 words

The Reckoning: Financial Accountability and the Rise and Fall of Nations

by Jacob Soll · 28 Apr 2014 · 382pp · 105,166 words

Capitalism: Money, Morals and Markets

by John Plender · 27 Jul 2015 · 355pp · 92,571 words

The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking and the Future of the Global Economy

by Mervyn King · 3 Mar 2016 · 464pp · 139,088 words

The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World

by Niall Ferguson · 13 Nov 2007 · 471pp · 124,585 words

How Markets Fail: The Logic of Economic Calamities

by John Cassidy · 10 Nov 2009 · 545pp · 137,789 words

Swimming With Sharks: My Journey into the World of the Bankers

by Joris Luyendijk · 14 Sep 2015 · 257pp · 71,686 words

State-Building: Governance and World Order in the 21st Century

by Francis Fukuyama · 7 Apr 2004

Barometer of Fear: An Insider's Account of Rogue Trading and the Greatest Banking Scandal in History

by Alexis Stenfors · 14 May 2017 · 312pp · 93,836 words

Masters of Management: How the Business Gurus and Their Ideas Have Changed the World—for Better and for Worse

by Adrian Wooldridge · 29 Nov 2011 · 460pp · 131,579 words

The Cost of Inequality: Why Economic Equality Is Essential for Recovery

by Stewart Lansley · 19 Jan 2012 · 223pp · 10,010 words

Risk Management in Trading

by Davis Edwards · 10 Jul 2014

The Devil's Derivatives: The Untold Story of the Slick Traders and Hapless Regulators Who Almost Blew Up Wall Street . . . And Are Ready to Do It Again

by Nicholas Dunbar · 11 Jul 2011 · 350pp · 103,270 words

Evil by Design: Interaction Design to Lead Us Into Temptation

by Chris Nodder · 4 Jun 2013 · 254pp · 79,052 words

Wait: The Art and Science of Delay

by Frank Partnoy · 15 Jan 2012 · 342pp · 94,762 words

The Weightless World: Strategies for Managing the Digital Economy

by Diane Coyle · 29 Oct 1998 · 49,604 words

The Bank That Lived a Little: Barclays in the Age of the Very Free Market

by Philip Augar · 4 Jul 2018 · 457pp · 143,967 words

The Money Machine: How the City Works

by Philip Coggan · 1 Jul 2009 · 253pp · 79,214 words

The Accidental Theorist: And Other Dispatches From the Dismal Science

by Paul Krugman · 18 Feb 2010 · 162pp · 51,473 words

Flash Crash: A Trading Savant, a Global Manhunt, and the Most Mysterious Market Crash in History

by Liam Vaughan · 11 May 2020 · 268pp · 81,811 words

How to Kick Ass on Wall Street

by Andy Kessler · 4 Jun 2012 · 77pp · 18,414 words

Why I Left Goldman Sachs: A Wall Street Story

by Greg Smith · 21 Oct 2012 · 304pp · 99,836 words

Global Governance and Financial Crises

by Meghnad Desai and Yahia Said · 12 Nov 2003

Billion Dollar Whale: The Man Who Fooled Wall Street, Hollywood, and the World

by Tom Wright and Bradley Hope · 17 Sep 2018 · 354pp · 110,570 words

When the Money Runs Out: The End of Western Affluence

by Stephen D. King · 17 Jun 2013 · 324pp · 90,253 words

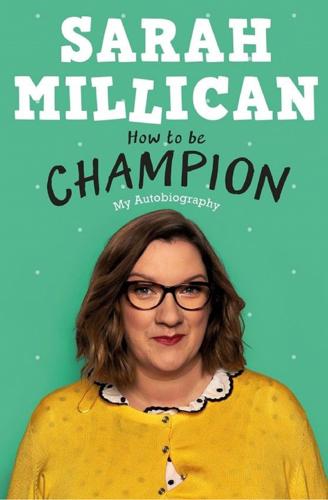

How to Be Champion: My Autobiography

by Sarah Millican · 16 Apr 2018 · 227pp · 81,467 words