Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future

by

Paul Mason

Published 29 Jul 2015

As a result, social spending by the state – on benefits, subsidies and other income-boosting measures – soared to dysfunctional levels, especially in Europe: from 8 per cent of GDP in the late 1950s to 16 per cent by 1975.26 Over roughly the same period in the USA, Federal spending on welfare, pensions and health doubled to 10 per cent of GDP by the late 1970s. All it needed to tip this fragile system into crisis was a shock. And in August 1971, Richard Nixon delivered one, unilaterally breaking the commitment to exchange dollars for gold, and thereby destroying Bretton Woods. Nixon’s reasons for doing so are well documented.27 As America’s competitors caught up in productivity terms, capital flowed out of the US into Europe, while its trade balance declined. By the late 1960s, with every country engaged in expansionary policies – with high state spending and low interest rates – America had become the big loser from Bretton Woods.

The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order

by

Benn Steil

Published 14 May 2013

Senators Charles Schumer and Lindsey Graham attacked the Chinese practice, declaring that “one of the fundamental tenets of free trade is that currencies should float.” This contradicted not only the intellectual history of economics, but the tenet that guided the United States at Bretton Woods.34 There is a common thread running through White’s blueprint for Bretton Woods in 1944, Nixon’s closing of the gold window in 1971, Rubin’s hailing of the Chinese currency peg in 1998, and Geithner’s condemnation of it in 2009: whether the United States supports fixed or floating exchange rates at any given point in time is determined by which will give it a more competitive dollar.

…

Collado, Emilio (1910–1995). American economist. Department of the Treasury, 1934–36; New York Federal Reserve Bank, 1936–38; Department of State, 1938–46; U.S. executive director of the World Bank, 1946–47. American technical adviser at Bretton Woods. Connally, John (1917–1993). American politician. Democratic governor of Texas, 1963–69; secretary of the Treasury, 1971–2. After Nixon closed the gold window in 1971, Connally famously told European officials that the dollar was “our currency, but your problem.” Cripps, Sir Richard Stafford (1889–1952). British diplomat and politician. Ambassador to the Soviet Union, 1940–42; president of the Board of Trade, 1945–47; minister for economic affairs, 1947; chancellor of the exchequer, 1947–50.

…

Longtime trusted friend of FDR. Had an important symbiotic political relationship with White, on whom he depended for policy formulation and who in turn depended on him for advancement and wider influence. Newcomer, Mabel (1892–1983). American economist. A Vassar professor, she was the only female American delegate at Bretton Woods. Nixon, Richard (1913–1994). American politician. President, 1969–74. As a member of the House Un-American Activities Committee, sparred with White in his August 1948 hearing. In 1950, publicly revealed an incriminating handwritten memo of White’s, given to Nixon by Whittaker Chambers. Effectively ended the Bretton Woods monetary system by ceasing the dollar’s fixed-rate gold convertibility in 1971.

Pivotal Decade: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the Seventies

by

Judith Stein

Published 30 Apr 2010

The American problem, he said, was that there was no central forum for reviewing such proposals.72 But the planning idea was overtaken by the developing currency crisis of the summer of 1971. And the president found a new counselor who offered a cocktail that promised quicker solutions to all of the American problems. THE END OF BRETTON WOODS Nixon’s guru was the former governor of Texas, Democrat John Connally, a protégé of Lyndon Johnson. The son of a sharecropper, the young Connally had honed his political skills at the University of Texas, where he was elected president of the student body. He had been a navy commander during World War II.

…

He reported “that they [the Europeans] did not feel anger as much as anguish that the United States had not arrived with a prepared solution to save the system [Bretton Woods].”86 The administration was divided on the fate of the fixed exchange system. Shultz, like his monetarist mentor Milton Friedman, wanted flexible rates. Volcker and Burns sought to salvage as many of the trees of Bretton Woods as they could. Connally and Nixon, who had neither institutional nor ideological loyalties, were agnostic. Both just wanted to get the job done— reverse the balance of payments, produce prosperity, and reduce unemployment. The bold action, especially the temporary border tax, was the stick to get the Europeans to accept a big shift in exchange rates, trade liberalization, and more help on defense costs.

Samuelson Friedman: The Battle Over the Free Market

by

Nicholas Wapshott

Published 2 Aug 2021

“In practice, most interventions are stupid attempts to defend the indefensible [i.e., usually central banks intervene too late to do anything but protect untenably high currency prices].”8 Faced with firm opposition to allowing the dollar to trade freely on the market from Friedman’s friend Arthur Burns, the president-elect’s principal adviser, Nixon decided to ignore Friedman’s advice and leave things as they were, at least for the time being. Before long, however, America’s Bretton Woods partners began to balk at being dependent upon the U.S. for their currency policies. Nixon appeared to ignore Friedman’s suggestion to abandon Bretton Woods and let the dollar float free, nor did he appear to be much interested in Friedman’s second suggestion: introduction of a negative income tax, which would combine welfare and tax assessments, with those with no or low incomes being given “rebates.”

…

As president, Nixon was confronted with a number of economic issues made worse by the vast public spending on the Vietnam War and the “Great Society” measures to reduce poverty left by Johnson. There was rising inflation, and a balance-of-payments deficit made worse by a weakening dollar and the obligation in the Bretton Woods Agreement for the U.S. to sell gold to other nations at a low price. Nixon was far more concerned about joblessness than inflation. He had inherited from Johnson full employment (3.3 percent unemployed), inflation at 5.3 percent, and interest rates at 4.25 percent, of which he considered low unemployment to be the most important.

…

Friedman and other market economists had always favored a free-floating dollar, one that would allow the market rather than the administration to settle on the price of the nation’s currency. Nixon’s August 1971 declaration effectively killed off Bretton Woods by allowing the U.S. monetary authorities to end their promise to exchange dollars for gold. In March 1973, Nixon formally ended Bretton Woods, leaving the dollar to float freely on the open market. As a means of addressing the balance-of-payments deficit, caused by Americans buying more from abroad than they sold in exports, Nixon also announced in August 1971 the immediate imposition of a 10 percent tariff on all imports.

Fed Up!: Success, Excess and Crisis Through the Eyes of a Hedge Fund Macro Trader

by

Colin Lancaster

Published 3 May 2021

“I’ll start with Paul Volcker, who died yesterday and who is the first one I can remember from my childhood. He was chairman of the Fed under Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan from ‘79 to ‘87, back when you could work for both a Democratic and Republican boss. It was a messy time. America was dealing with oil shocks, the fallout from the Vietnam War, the end of the Bretton Woods system, and then massive tax cuts. Inflation spiked when Nixon decided to leave Bretton Woods, the gold standard. The US dollar’s status as the reserve currency of the world was in serious doubt. Investors were convinced that inflation would never come down and were dumping Treasuries at any price. They bought as much gold as they could.

How the World Works

by

Noam Chomsky

,

Arthur Naiman

and

David Barsamian

Published 13 Sep 2011

on corruption in Mexico discussion with Japanese businessman in East Timor and editors as ruling class Foxman’s letter to Friedman in Gulf war reporting by on Haiti embargo on “hidden transactions” in Latin America importance of reading improvements at improvements limited at Indonesia praised in on “industrial-military complex,” on Israel providing arms to Iran on liberals vs. conservatives (op-ed) on NAFTA on new “populism,” Nicaragua ignored by on Pentagon Papers on plutonium disposal on postmodernism prison labor stories in pro-Clinton story in Romero’s assassination ignored by seen as Chomsky’s “stomping ground,” Shavit op-ed on Vatican’s impact in Latin America on victory in Nicaragua on Vietnam War on workers’ rights in Indonesia New York Times Week in Review New York University NGO Nicaragua Contras drug trade in drug trafficking in example made of fall of Somoza Hurricane Joan in ignored by media land reform in Miskito Indians in National Guard atrocities 1987 peace plan 1990 elections Somocismo without Somoza in Somoza’a rule in US intervention in World Court condemnation of US in Niebuhr, Reinhold Niemann, Sandy 9/11: The Simple Facts 1984 Nitze, Paul Nixon administration Bretton Woods system dismantled during Noriega assassination considered by Nixon, Richard Chile destroyed by CIA and economic policy change by Kissinger on as last liberal president Vietnam “peace treaty” and Nkrumah, Kwame Nobel Peace Prize nonaligned movement nonviolence Noriega, Manuel change from friend to “villain,” charges against on CIA payroll elections stolen by human rights record of North Africans North America, genocide in North American Free Trade Agreement.

The Economists' Hour: How the False Prophets of Free Markets Fractured Our Society

by

Binyamin Appelbaum

Published 4 Sep 2019

But Gardner Ackley, chairman of Johnson’s Council of Economic Advisers, privately warned that America would need to devalue the dollar, too. It was only a matter of timing. Economic Nationalism During the 1968 election campaign, Richard Nixon asked Arthur F. Burns, his top economic adviser, to sound out European governments on the future of Bretton Woods. Burns reported the situation was “very precarious,” but not beyond repair. He urged Nixon to seek a new set of fixed rates. “Let us not develop any romantic ideas about a fluctuating exchange rate,” Burns instructed. Harking back to the 1930s, he warned, “There is too much history that tells us that a fluctuating exchange rate, besides causing a serious shrinkage of trade, is also apt to give rise to international political turmoil.”23 Nixon’s chief diplomat for monetary policy, Paul Volcker, agreed with Burns.

…

The flattery continued in the morning: Burns wrote in his diary that when the President promised all present a Camp David jacket with their name on the front, he, Arthur Burns, received the additional gift of a pair of Camp David glasses.37 That Sunday night, Nixon began his televised speech to the nation by boasting the Vietnam War was going so well that it was time to talk about the economy. There were three problems, he said: unemployment, inflation, and Bretton Woods. To create jobs, Nixon announced billions of dollars in tax cuts. To curb inflation, he announced the first peacetime controls on wages and prices in American history. And to rebalance trade, he announced the United States no longer would guarantee the exchange value of the dollar. The price of a British pound, and every other currency tied to the dollar, was suddenly an open question.

…

He hired the Merc’s first economist and told the man to write Friedman seeking advice, one economist to another, on how to create such a market. Friedman, who made a point of answering almost any letter from almost anyone, wrote back a few weeks later offering encouragement but pointing out the moment was not ripe because changes in exchange rates were rare events under the Bretton Woods system. After Nixon’s speech, Melamed himself wrote to Friedman, persuading the professor to travel from his vacation home in Vermont for a breakfast at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York. There he offered Friedman five thousand dollars to write an endorsement of a new financial market for trading in currency futures.

Every Nation for Itself: Winners and Losers in a G-Zero World

by

Ian Bremmer

Published 30 Apr 2012

The Americans and Europeans had nuclear weapons, but OPEC’s leading members had discovered they had a kill switch that could quickly send Western economies into recession.30 Having made its point, OPEC lifted the embargo in March 1974. The damage to other currencies done by the Bretton Woods peg to a declining U.S. dollar, President Nixon’s decision to “close the gold window,” the havoc wreaked by the oil embargo, and the willingness of America’s European allies to withdraw support for U.S. policy in the Middle East to protect their own oil supplies underlined an emerging reality: Few will follow a leader who isn’t leading toward the promise of peace and prosperity.

Inflated: How Money and Debt Built the American Dream

by

R. Christopher Whalen

Published 7 Dec 2010

He marches out of one life into a new world without any apologies or glancing back.”31 But Sidey’s description of Nixon could have also applied to FDR and to many other modern American politicians. Nixon’s actions were a major repudiation of the original vision of Keynes as well as the other framers of Bretton Woods, none of whom were apologists for inflation or borrowing except in times of emergency. Nixon’s final repudiation of gold and his explicit embrace of deficit spending to ensure full employment was a radical departure from the stated practice of either political party. While Lyndon Johnson established the Great Society programs to fight poverty and improve education, their impact on the federal budget was modest compared to the level of federal spending authorized under President Nixon as part of the Soviet-style New Economic Policy.

…

Nixon admitted at the time that he was not sure of the impact of the decision to close the gold window. Fed Chairman Burns was against closing the gold window, but was in agreement with the other aspects of the Nixon NEP. Connally would say after the summit meeting that when Nixon announced the unilateral United States departure from Bretton Woods: “We have awakened forces that nobody is at all familiar with.” Chairman Burns, for his part, urged Nixon during the discussions not to close the gold window when he announced the other measures, feeling that these policy changes were more than sufficient to stop the outflow of gold. “If we close the window, other countries could double the price of gold.

…

Geithner, Timothy General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) General Motors (GM) bailout bankruptcy organization collapse debt, impact du Pont investment Durant support General Motors Acceptance Corporation (GMAC) bailout credit supply founding Germany Barron attack (Wall Street Journal) central powers, attack (Barron support) WWI debt imposition, impact GI Bill of Rights Gilbert, Clinton (Mirrors of Wall Street) Gilbert, Parker Gilded Age cessation comparison impact trusts, near-bank status Glass, Carter American principle devotion Banking Act sponsorship populist facade proposal Secretary of the Treasury status Glass-Steagall Act Glass-Steagall laws Global currency backing system, problem Global imbalances Global inflation Global marketplace, U.S. advantage Global markets, dollar flow Global payments system, U.S. response Global system, equilibrium Gold Bretton Woods, impact coinage, hard money Jacksonian notion (continuation) coins (specie) confiscation hoarding confiscation conspiracy, relief convertibility Nixon cessation restoration (1879) American resistance return dollar peg, cessation (1971) dollar price, increase exchange FDR, impact greenbacks convertibility, restoration exchange market dynamic movement Fed policy independence impact paper dollars, relationship payment (WWI), promise post-market crisis, Gould operation price fluctuation peak (1869) production purchase, greenbacks (Gould usage) refinement, cyanide process (adoption) reserves bank drain drain seizure Board of Governors complicity stocks, U.S. government holding supply, expansion Goldenweiser, E.A.

The Global Minotaur

by

Yanis Varoufakis

and

Paul Mason

Published 4 Jul 2015

In short, Japan and the Europeans found themselves between a rock and a hard place. Toward the end of 1971, in December, Presidents Nixon and Pompidou met in the Azores. Pompidou, eating humble pie over his destroyer antics, pleaded with Nixon to reconstitute the Bretton Woods system, on the basis of fresh fixed exchange rates that would reflect the new ‘realities’. Nixon was unmoved. The Global Plan was dead and buried, and a new unruly beast, the Global Minotaur, was to fill its place. Once the fixed exchange rates of the Bretton Woods system collapsed, all prices and rates broke loose. Gold was the first: it jumped from $35 to $38 per ounce, then to $42, and then off it floated into the ether.

How to Speak Money: What the Money People Say--And What It Really Means

by

John Lanchester

Published 5 Oct 2014

Countries agreed to fixed exchange rates, tied to the US dollar, which in turn was tied to the ownership of actual, physical gold; the conference also agreed to the creation of the International Monetary Fund and the International Bank of Reconstruction and Development, which was to become the World Bank. The specific aim of the conference was to avoid the “beggar thy neighbor” policies between states that had played such a role in the turmoil of the twentieth century. The Bretton Woods system lasted from 1945 until President Nixon unilaterally took the USA off it on 15 August 1971, an event known as the “Nixon shock,” which reintroduced free-floating currencies. Nixon’s reasons for doing that were linked to the pressures on the US economy created by the Vietnam War and the growing trade deficit; his actions allowed the US dollar to drop in value, which was a help to industry and exports.

War and Gold: A Five-Hundred-Year History of Empires, Adventures, and Debt

by

Kwasi Kwarteng

Published 12 May 2014

He was first and foremost a politician, not a monetary theorist, which was precisely why Nixon had appointed him.47 His instincts on the international stage were strongly nationalistic, which rather undermined the spirit of international co-operation, under American leadership, which had characterized Bretton Woods. His nationalistic poses also chimed well with Nixon’s views of himself as a ‘tough guy’, a man of action and decisiveness. Connally’s assertiveness with international financiers at high-level conferences quickly became the stuff of legend. He described himself, with pompous self-conceit, as the ‘bully boy on the manicured playing fields of international finance’.

…

The place, Greenspan was rather horrified to discover, was ‘filled with piles of old newspapers and all the other clutter of a bachelor apartment’.30 It was during the early 1980s, at the height of the high-interest-rate-induced recession, that some on the right of the Republican Party began to yearn for a return to the gold standard, or at least to the pre-1971 Bretton Woods arrangement. In 1982 Ron Paul, a Texas Congressman, denounced Nixon’s severance of ‘the last link between the dollar and gold’. The ‘present crisis’ had ‘not developed in the past year’, but had been ‘growing for at least a decade’. The ‘10-year experiment with paper money has failed; it is time that the Congress recognize that failure’.

…

As Reinhart and Rogoff have stated in the preface of their empirical study into financial crises, This Time is Different, ‘Although private debt certainly plays a key role in many crises, government debt is far more often the unifying problem across the wide range of financial crises we examine.’6 Government debts, of course, are connected with the stability, or otherwise, of currencies. This is what the Greek crisis taught the world. It is notable that the biggest sovereign debt crisis occurred in the eurozone, given that European monetary union itself was an attempt to restore stability to Europe’s currency in the aftermath of the collapse of Bretton Woods in the early 1970s. Richard Nixon’s closing of the ‘gold window’ therefore had profound consequences. Paper money indisputably contributed to an excess of credit creation and directly to the crisis of 2008, as the mountain of credit turned into an avalanche of bankruptcy. The conclusion is that many participants in the global financial system have dug ‘a debt hole far larger than they can reasonably expect to escape from’.7 This may be an unduly pessimistic judgement.

The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People's Economy

by

Stephanie Kelton

Published 8 Jun 2020

Nixon shocked the world by declaring a temporary suspension of the dollar’s convertibility into gold. A second shock followed in 1973, when Nixon announced that he was making the “temporary” suspension permanent. Nixon’s move was brought about by the realization that the US needed more policy space than was available under Bretton Woods. Announcing the change in policy, Nixon declared: “We must create more and better jobs; we must stop the rise in the cost of living; we must protect the dollar from the attacks of international money speculators.”17 To achieve the first two goals, he proposed tax cuts and a 90-day freeze on prices and wages; to achieve the third, Nixon directed the suspension of the dollar’s convertibility into gold.

…

Committee on Decent Work in Global Supply Chains, “Resolution and Conclusions Submitted for Adoption by the Conference,” International Labour Conference, ILO, 105th Session, Geneva, May–June 2016, www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_489115.pdf. 17. Office of the Historian, “Nixon and the End of the Bretton Woods System, 1971–1973,” Milestones: 1969–1976, history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/nixon-shock. 18. Kimberly Amadeo, “Why the US Dollar Is the Global Currency,” The Balance, December 13, 2019, www.thebalance.com/world-currency-3305931. 19. Brian Reinbold and Yi Wen, “Understanding the Roots of the U.S. Trade Deficit,” St. Louis Fed, August 16, 2019, medium.com/st-louis-fed/understanding-the-roots-of-the-u-s-trade-deficit-534b5cb0e0dd. 20.

The Physics of Wall Street: A Brief History of Predicting the Unpredictable

by

James Owen Weatherall

Published 2 Jan 2013

Zbig: The Life of Zbigniew Brzezinski, America's Great Power Prophet

by

Edward Luce

Published 13 May 2025

In a second shock to both Japan and Europe in August 1971, Nixon said that the US would be exiting the gold standard and slapped a 10 percent surcharge on all imports. The US dollar would no longer be convertible into gold. At a stroke and without consulting his own Treasury Department, let alone the allies, Nixon pulled the plug on the postwar Bretton Woods system. Nixon was making America’s allies poorer and more paranoid at the same time. The Nixon shocks came a few weeks after Brzezinski and Muska had returned from Japan. During their stay in Tokyo, Brzezinski had picked up on Japan’s deep insecurity about America’s direction. Nixon made his two announcements while the Brzezinskis were in Maine.

The Scandal of Money

by

George Gilder

Published 23 Feb 2016

The Alchemists: Three Central Bankers and a World on Fire

by

Neil Irwin

Published 4 Apr 2013

July 22, 1944—Global economic leaders finish a conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, where they agree to a world economic order for the post–World War II globe. August 15, 1971—With the United States struggling to maintain the peg of the dollar to gold as mandated by the Bretton Woods system, President Richard Nixon suspends the gold window. His advisers include Federal Reserve chairman Arthur Burns and Treasury official Paul Volcker. 1978—In Arthur Burns’s final year as Federal Reserve chair, inflation reaches 9 percent. October 6, 1979—In an unscheduled Saturday meeting of Fed policymakers, new chairman Paul Volcker engineers an interest rate hike and a new strategy to tighten the money supply, aiming to bring down inflation.

Trade Wars Are Class Wars: How Rising Inequality Distorts the Global Economy and Threatens International Peace

by

Matthew C. Klein

Published 18 May 2020

Similarly, the U.S. government made a choice to tie the international financial system to the dollar after the end of World War II. At first, issuing the reserve currency was not a burden. It may even have made sense at a time when American production made up nearly half of global output. Those early postwar years, however, were an anomaly. By 1971, the choice made at Bretton Woods had become untenable, so the Nixon administration broke the link to gold. Starting in the 1990s, however, savers in the rest of the world decided that the dollar was the international reserve asset, regardless of any formal commitments. The resulting financial inflows were accommodated by the U.S. political and financial system—with disastrous consequences for Americans.

The New Depression: The Breakdown of the Paper Money Economy

by

Richard Duncan

Published 2 Apr 2012

The Social Life of Money

by

Nigel Dodd

Published 14 May 2014

The work of Aglietta and Orléan makes interesting reading during an era in which currency wars have once again become a leading theme in international relations. In La fin des devises clés (“The end of key currencies”), published in 1986, Aglietta imagined a future in which there would be no leading currency (Aglietta 1986). Writing in the wake of the Bretton Woods collapse, Aglietta suggested that gold—specifically—had been the monetary analogue to religion.42 In this sense, Nixon’s decision to decouple the dollar from gold could be seen as an act of desacralization. Without a religious analogue such as gold, the global monetary system could not operate well because it is built on sovereignty, and therefore the threat of violence.

…

The discussion of primitive accumulation in the last chapter suggested that modern money is underpinned by the national debt, and Graeber’s analysis is broadly consistent with this idea. According to his schema, the latest regime of credit (as opposed to bullion) money began when the Bretton Woods system broke down. Nixon’s decision to leave the gold standard in 1971 initiated a “new phase of financial history” that “nobody completely understands” (Graeber 2011: 362). The post–Bretton Woods era has attracted its fair share of myths and conspiracy theories: specifically about gold, banks, and free markets.

Keynes Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics

by

Nicholas Wapshott

Published 10 Oct 2011

I replied that it might not be worth winning the election at the cost of a major inflation subsequently. Nixon said something like, ‘We’ll worry about that when it happens.’”26 In August 1971, Nixon brought to an end the Bretton Woods fixed-currency regime. If Friedman, an inveterate opponent of Bretton Woods, was given cause to celebrate, it was short-lived: Nixon also imposed a legally binding price and income freeze. “The last time I saw Nixon in the Oval Office, with George Shultz,” Friedman recalled, “President Nixon said to me, ‘Don’t blame George for this silly business of wage and price control.’ . . . I said to him, ‘Oh, no, Mr.

Age of Greed: The Triumph of Finance and the Decline of America, 1970 to the Present

by

Jeff Madrick

Published 11 Jun 2012

It is one thing to freeze prices and wages when the economy is growing modestly, another when it has been stimulated to grow rapidly. Inflation rose quickly under Phase III of the controls program, and this put more pressure on exports and the dollar. The dollar had already been devalued further, and by October 1973 it was likely to be cut again. Finally, the fixed exchange rates of the Bretton Woods agreement were formally abandoned by the Nixon administration altogether. The United States would no longer redeem dollars for gold and the currency would float, as would most others, in an international financial market uncontrolled by government. This eventually led to further declines in the dollar, inflationary because it raised import prices.

…

The Nixon administration’s call for strong economic action appealed to him, and, as discussed, he and Murray Weidenbaum, who reported to him, eagerly developed their plan for the ninety-day freeze on wages and prices. He also became central to the Nixon plans to rewrite the rules of Bretton Woods. Volcker later wrote that he regretted that the Nixon administration did not have a better strategy to follow the ninety-day freeze. He also regretted dismantling the Bretton Woods system since he was more comfortable with a fixed-rate currency system than the floating rates that followed. Though a Democrat, he was not especially liberal, but he also did not trust the financial markets to sort out the complexities of currency values on their own, and did not believe, as Wriston vehemently did, that unregulated interest rates would result in the most efficient allocation of capital.

The Death of Money: The Coming Collapse of the International Monetary System

by

James Rickards

Published 7 Apr 2014

The 1914 collapse was precipitated by the First World War and was followed later by alternating episodes of hyperinflation and depression from 1919 to 1922 before regaining stability in the mid-1920s, albeit with a highly flawed gold standard that contributed to a new collapse in the 1930s. The Second World War caused the 1939 collapse, and stability was restored only with the Bretton Woods system, created in 1944. The 1971 collapse was precipitated by Nixon’s abandonment of gold convertibility for the dollar, although this dénouement had been years in the making, and it was followed by confusion, culminating in the near dollar collapse in 1978. The coming collapse, like those before, may involve war, gold, or chaos, or it could involve all three.

…

On October 25, 2012, the Boeing Corporation conducted a financial war game during an offsite conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. The conference was held at the historic Mount Washington Hotel, famous as the site of the 1944 Bretton Woods conference that established the international monetary system, which prevailed from the end of the Second World War until President Nixon closed the gold window in 1971. Although Boeing is a corporation and not a sovereign state, its interest in financial warfare is hardly surprising. Boeing has employees in seventy countries and customers in 150 countries, and it is one of the world’s largest exporters.

…

These three episodes from the past 150 years make the point that gold standards come in many forms and that their success or failure is determined not by gold per se but by the system design and the willingness of participants to abide by the rules of the game. Consideration of a new gold standard begins with the understanding that the old gold standard was never completely left behind. When the Bretton Woods system broke down in August 1971, with President Nixon’s abandonment of gold convertibility by foreign central banks, the gold standard was not immediately deserted. Instead, in December 1971 the dollar was devalued 7.89 percent so that gold’s official price increased from $35 per ounce to $38 per ounce. The dollar was devalued again on February 12, 1973, by an additional 10 percent so that gold’s new official price was $42.22 per ounce; this is still gold’s official price today for certain central banks, for the U.S.

The Sushi Economy: Globalization and the Making of a Modern Delicacy

by

Sasha Issenberg

Published 1 Jan 2007

Nixon responded by devaluing the dollar; under an agreement signed in December 1971, it would trade at 308 yen. In Washington, this move was part of a package of moves to dismantle the postwar global-finance system—the abolition of the gold standard, which led to the end of the Bretton Woods system—that came to be known as “the Nixon Shock.” At Tsukiji, it meant one thing: Overnight, the cost of importing bluefin tuna into Japan fell by 15 percent. Allowed to float freely, Japan’s currency set off on a generation-long upward trajectory against the United States, eventually trading for fewer than 100 yen to the dollar.

Currency Wars: The Making of the Next Gobal Crisis

by

James Rickards

Published 10 Nov 2011

Nixon wrapped his actions in the American flag, going so far as to say, “I am determined that the American dollar must never again be a hostage in the hands of international speculators.” Of course, it was U.S. deficits and monetary ease, not speculators, that had brought the dollar to this pass, but, as with FDR, Nixon was not deterred by the facts. The last vestige of the 1944 Bretton Woods gold standard and the 1922 Genoa Conference gold exchange standard was now gone. Nixon’s New Economic Policy was immensely popular. Press coverage was overwhelmingly favorable, and on the first trading day after the speech the Dow Jones Industrial Average had its largest one-day point gain in its history up until then. The announcement has been referred to ever since as the Nixon Shock.

…

QE programs China’s levels during 1980s and 2011 dollar inflation monetarism and fears of in 1920s Germany and 1930s deflation stagflation in U.S. during 1970s U.S. levels during 1960s and 1980s interdependence, in complex systems interest rates interesting in-between, in complex systems International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA) International Monetary Fund (IMF) Brazil and under Bretton Woods system creation of special drawing rights (SDRs) in currency wars declares end of Bretton Woods system G20 and Germany and gold accumulation from as global central bank global reserve currencies database and Nixon’s import surtax and SDRs international monetary system international trade, gold standard in Iran Ireland “iron rice bowl” welfare policy, China’s 1990s isolation, in economics Israel Italy Jackson, Andrew January effect Japan and gold standard invasions and conquests by and Panic of 1931 rare earth exports skirmish with China trade deficits during 1980s 2011 earthquake/tsunami in Sendai U.S. mortgage crisis and Japanese stocks yen and Nixon’s New Economic Policy yen-dollar relationship after 2011 earthquake in Johnson, Lyndon B.

Powers and Prospects

by

Noam Chomsky

Published 16 Sep 2015

Profit Over People: Neoliberalism and Global Order

by

Noam Chomsky

Published 6 Sep 2011

Magic Internet Money: A Book About Bitcoin

by

Jesse Berger

Published 14 Sep 2020

Chapter 3: Money 4Established by Carl Menger, the father of the Austrian school of economics, and popularized by Ludwig Von Mises and his student, F.A. Hayek, among others. 5In 1971, former US President Richard Nixon undertook a series of economic measures to respond to increasing inflation. The most significant rendered inoperative the existing Bretton Woods system of international financial exchange. It came to be known as the Nixon Shock. 6Occurring between 2007 and 2008, it is considered by many economists to be the most serious financial crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Chapter 4: Growth 7Robert Breedlove, “Bitcoin and the Tyranny of Time Scarcity” The Bitcoin Times online (December 19, 2019). 8Evelyn Cheng, “Bitcoin debuts on the world’s largest futures exchange, and prices fall slightly” CNBC: Markets online (December 17, 2017). 9Ryan Brown, “New York Stock Exchange owner launches futures contracts that pay out in bitcoin” CNBC: Cryptocurrency online (September 23, 2019).

The Age of Cryptocurrency: How Bitcoin and Digital Money Are Challenging the Global Economic Order

by

Paul Vigna

and

Michael J. Casey

Published 27 Jan 2015

After all, there is no fully endorsed international criminal court; the one in The Hague isn’t recognized by Washington. The international realm exists in a state of quasi anarchy—a perfect fit for borderless cryptocurrencies. Some international agreements do stick, such as the Bretton Woods system of pegged currencies established in 1944 amid the crisis of World War II (and ended when President Nixon squelched the gold standard in 1971). Might a cryptocurrency crisis goad governments into another such sweeping agreement? A Bretton Woods II? Those who’ve dreamed of the IMF’s playing an intermediary role in international commerce, who’ve wanted to free the world of its unhealthy dependence on the dollar and to reduce the excessive influence of the Fed and U.S.

Griftopia: Bubble Machines, Vampire Squids, and the Long Con That Is Breaking America

by

Matt Taibbi

Published 15 Feb 2010

OPEC effectively quadrupled prices in a very short period of time, from around three dollars a barrel in October 1973 (the beginning of the boycott) to more than twelve dollars by early 1974. The United States was in the middle of its own stock market disaster at the time, caused in part by the dissolution of the Bretton Woods agreement (the core of which was Nixon’s decision to abandon the gold standard, an interesting story in its own right). In retrospect we ought to have known we were in trouble earlier that year because on January 7, 1973, then–private economist Alan Greenspan told the New York Times, “It is very rare that you can be as unqualifiedly bullish as you can be now.”

Panderer to Power

by

Frederick Sheehan

Published 21 Oct 2009

We are in the wildest inflation since the Civil War.”46 After that climactic finale, a troop of singers and dancers burst into the room to stage the evening’s entertainment: “The Decline and Fall of the Entire World as Seen through the Eyes of Cole Porter.”47 On August 15, 1971, President Nixon announced the United States’s unilateral decision to no longer pay gold to foreign governments for dollars. He blamed speculators.48 He did not give blame where it was due: to the American people and, perhaps foremost, to the decision makers in the Oval Office, who had done a bang-up job of destroying the Bretton Woods agreement. At no time did Nixon acknowledge that the United States had committed the shameful act of default. Nixon also used this opportunity to place wage and price controls on practically every American. The land of the free and the brave was looking anything but. Most Americans were in favor of this initiative by the government—the same government that had shown neither the knowledge nor the backbone to avoid the financial chaos that now engulfed the free world.

The Man Who Knew: The Life and Times of Alan Greenspan

by

Sebastian Mallaby

Published 10 Oct 2016

But to attain full employment, the United States had to do the opposite—it had to accept inflation in accordance with the implication of the Phillips curve, which indicated that rising prices could sustainably boost the number of jobs in the economy. As the goal of full employment trumped the fealty to Bretton Woods, rising inflation eroded confidence in the dollar.41 Indeed, by the time Nixon’s advisers gathered at Camp David, the dollar-gold link was close to breaking. The floor was opened to debate. Nixon and his counselors confronted a choice between two options: They could take radical steps to rein in inflation and shore up confidence in the dollar.

…

The way he saw things, the miraculous growth of the postwar era was not the achievement of the invisible hand; rather, it was the result of the international architecture established at the end of World War II, with the United States at its center. “For thirty years, the modern economic system created at the Bretton Woods conference of 1944 has served us well,” Kissinger declared; by creating a framework of stability, it had allowed commerce to flourish. It was hardly surprising that the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, marked by Nixon’s abandonment of the gold peg, was now leading to trouble; it was the job of statesmen to come up with a fresh architecture to replace the old one. Kissinger duly proposed a series of price-stabilizing commodity agreements between producer and consumer nations. “Global interdependence is a reality,” Kissinger averred.

That Used to Be Us

by

Thomas L. Friedman

and

Michael Mandelbaum

Published 1 Sep 2011

Born in Flames

by

Bench Ansfield

Published 15 Aug 2025

America in the World: A History of U.S. Diplomacy and Foreign Policy

by

Robert B. Zoellick

Published 3 Aug 2020

A few years later, Ronald Reagan pursued a very different approach toward the Soviets.93 U.S. allies in the Pacific had more difficulty adjusting to realpolitik and the opening to China. Economic competition and conflicts exacerbated the tension of the strategic shift. Japan’s economy posed a challenge to U.S. producers. The old Bretton Woods currency exchange rates were out-of-date. Nixon applied the boldness of realpolitik to economic arrangements without the finesse and nuance that Kissinger infused into traditional foreign policy. Nixon looked to his treasury secretary, former Texas governor John Connally, to lead on international economics. Connally, an LBJ protégé, succinctly expressed his economic realpolitik: “Foreigners are out to screw us… our job is to screw them first.”94 Reopening the door to China would stand as an achievement in its own right.

Meltdown: How Greed and Corruption Shattered Our Financial System and How We Can Recover

by

Katrina Vanden Heuvel

and

William Greider

Published 9 Jan 2009

The Quiet Coup: Neoliberalism and the Looting of America

by

Mehrsa Baradaran

Published 7 May 2024

Not only did the neoliberal capture of the law abet the massive secondary and tertiary markets of risk built atop mortgages, but—by rescuing and insuring these privately created products during the financial crisis—it conferred new property rights backed by state power. DEBT The decision to end the Bretton Woods Agreement barriers on international capital flows, Richard Nixon had surmised, would allow the United States to tap into the world’s savings, but that didn’t actually happen until the Reagan era. The Reagan administration’s fiscally irresponsible tax cuts and increased military spending led to massive deficits, but its liberalized financial policies converted U.S. debt into a financial product that could be bought and sold by other countries.

The Long Good Buy: Analysing Cycles in Markets

by

Peter Oppenheimer

Published 3 May 2020

1961–1962 ‘Kennedy Slide’: Rising rates from 1959 Cold War tension No - 1966 Inflation following Johnson Great Society programme; Fed raised rates by approximately 1.5% in 1 year No - 1968–1970 Vietnam war and inflation; Fed raised rates to 9% from 4% 2 years before; between the start of 1968 and mid-1968 rates rose by 3% Yes Dec 1969 – Nov 1970 1973–1974 The crash after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system over the previous 2 years, with the associated ‘Nixon Shock’ and USD devaluation under the Smithsonian Agreement 1973 Oil Crisis: Price of oil rose from $3 per barrel to nearly $12 Yes Nov 1973 – Mar 1975 1980–1982 ‘Volcker crash’; the 1979 second oil crisis was followed by strong inflation; the Fed raised its rates from 9% to 19% in six months Yes Jan 1980 – July 1980 Jul 1981 – Nov 1982 1987 Black Monday: Flash Crash: computerised ‘programme trading’ strategies swamped the market; tensions between the US and Germany over currency valuations No - 1990 Gulf War: Iraq invasion of Kuwait; oil prices doubled Yes July 1990 – Mar 1991 2000–2002 Dotcom bubble; technology companies bankruptcy; Enron scandal; 09/11 attacks Yes Mar 2001 – Nov 2001 2007–2009 Housing bubble; sub-prime loan & CDS collapse; US housing market collapse Yes Dec 2007 – Jun 2009 Extending this analysis shows that, on the standard definition (of declines of 20% or more), there have been 27 bear markets in the S&P 500 since 1835 and 10 in the post-war period.

An Extraordinary Time: The End of the Postwar Boom and the Return of the Ordinary Economy

by

Marc Levinson

Published 31 Jul 2016

Nine Crises: Fifty Years of Covering the British Economy From Devaluation to Brexit

by

William Keegan

Published 24 Jan 2019

To work properly, it required controls on movements of capital: such movements can far outweigh the impact of currency flows precipitated by ordinary trade. We have seen the lengths to which the Wilson government went to try to avoid changes, such as the devaluation of the pound in 1967, which were in fact necessary. But when the Bretton Woods system broke down in 1971–73 – with the Nixon administration no longer being prepared to support the rates of other currencies against the US dollar, which was itself devalued – the world embarked on not so much a system as a non-system of ‘floating rates’. Once the major nations embarked on a world of floating exchange rates, there could be wild gyrations in those rates.

Butler to the World: How Britain Became the Servant of Tycoons, Tax Dodgers, Kleptocrats and Criminals

by

Oliver Bullough

Published 10 Mar 2022

And the second, which interlocks elegantly with the first, is that there is no point refraining from bad behaviour until everyone else agrees to do so, because that would achieve nothing. If I don’t steal your money, somebody else will; and there’s no point in me stopping until everyone else does too. Together these two arguments spelled doom for the Bretton Woods system of capital controls. Five months later, President Richard Nixon, infuriated by his inability to control inflation by limiting the amount of currency in circulation, abandoned the US dollar’s peg to gold. From then on, the dollar would be worth whatever someone would pay for it. All dollars became Eurodollars, and the bankers got their solution to the trilemma.

The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism

by

Joyce Appleby

Published 22 Dec 2009

Rather than raise taxes, President Lyndon Johnson preferred to have the Federal Reserve print money. This move exacerbated the ongoing weakening of the world’s major currency. The resulting glut made it difficult for the U.S. Treasury to continue to convert dollars into gold as it had promised to do in the Bretton Woods agreement. Johnson’s successor, Richard Nixon, pulled the dollar off the gold standard, in 1971. Now all currencies were free to float. In fact, agitated by worldwide inflation, they splashed around furiously for two years.45 Eroding even faster was American oil production. The United States had supplied almost 90 percent of the oil that the Allies used during World War II.

Financial Market Meltdown: Everything You Need to Know to Understand and Survive the Global Credit Crisis

by

Kevin Mellyn

Published 30 Sep 2009

Global Governance and Financial Crises

by

Meghnad Desai

and

Yahia Said

Published 12 Nov 2003

The parity grid became rigid in the 1960s, and the provision for international liquidity was plagued by the so-called Triffin’s dilemma. Furthermore, capital controls were circumvented by the growth of the Eurodollar market, so that speculative pressures on Sterling became overwhelming in October 1967. This episode originated the agony of the Bretton Woods monetary order, whose coup de grâce was struck by President Nixon on August 15, 1971, when he shut the gold window once and for all. This purely opportunistic political move gave rise to a sea change in the advent of a market-led system. Rejuvenating the IMF after the demise of the Bretton Woods order Following the deceitful Smithsonian Institute Agreement in December 1971, which reset the exchange rate ladder, the IMS had been laid out on a pure Dollar standard.

Liberalism at Large: The World According to the Economist

by

Alex Zevin

Published 12 Nov 2019

Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and Unknowns in the Dazzling World of Derivatives

by

Satyajit Das

Published 15 Nov 2006

Crapshoot Investing: How Tech-Savvy Traders and Clueless Regulators Turned the Stock Market Into a Casino

by

Jim McTague

Published 1 Mar 2011

Broken Markets: A User's Guide to the Post-Finance Economy

by

Kevin Mellyn

Published 18 Jun 2012

Stolen: How to Save the World From Financialisation

by

Grace Blakeley

Published 9 Sep 2019

Inside the House of Money: Top Hedge Fund Traders on Profiting in a Global Market

by

Steven Drobny

Published 31 Mar 2006

It wasn’t until the breakdown of the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1971, and the subsequent decline in the U.S. dollar, that the investment universe again offered the opportunities that spawned the next generation of global macro managers. POLITICIANS AND SPECULATORS Recent history is riddled with examples of politicians attempting to place blame on speculators for shortcomings in their own policies, and the breakdown of Bretton Woods was no exception. When the currency regime unraveled, President Nixon attempted to lay blame on speculators for “waging an all-out war on the dollar.” In truth, his own inflationary policies are more often cited as the underlying problem, with speculators a mere symptom of the problem. As Andres Drobny (Drobny Global Advisors) describes it in his interview: Speculators definitely don’t [drive markets].There’s an old debate in economics as to whether speculators are deviation “dampeners” or deviation “amplifiers.”

A Generation of Sociopaths: How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America

by

Bruce Cannon Gibney

Published 7 Mar 2017

Capitalism 4.0: The Birth of a New Economy in the Aftermath of Crisis

by

Anatole Kaletsky

Published 22 Jun 2010

With homes, factories, and roads no longer threatened by military destruction, the habits of saving and frugality imposed on previous generations by the needs of postwar reconstruction, receded into the past. Five, the demystification of money was a less widely noticed but equally unprecedented event. This process began with the collapse of the Bretton Woods international currency system in 1971. On August 15, 1971, President Nixon closed the “gold window,” where the U.S. Treasury had always stood ready, at least in theory, to convert into gold any dollars presented by foreign governments. Because the dollar had become the sole standard of value for all currencies—even in Communist countries such as China, Russia, and Cuba—after World War II, the decision to sever its official link with gold was momentous.

Water: A Biography

by

Giulio Boccaletti

Published 13 Sep 2021

The Establishment: And How They Get Away With It

by

Owen Jones

Published 3 Sep 2014

The Cold War: A World History

by

Odd Arne Westad

Published 4 Sep 2017

Portfolio Design: A Modern Approach to Asset Allocation

by

R. Marston

Published 29 Mar 2011

During this period, financing was available primarily through loans from national governments and (in the postwar period) international agencies such as the World Bank. Even banks were wary of foreign lending. The third phase began in the early 1970s when capital controls began to be lifted. It was in this period that the so-called Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates came to an end. In 1971, the Nixon Administration ended the dollar’s tie to gold. Over the next few years, many industrial countries allowed their currencies to float vis-à-vis the dollar. With less need to defend their currencies, governments began to relax their capital controls. Some countries lagged behind in this process.

The Vanishing Middle Class: Prejudice and Power in a Dual Economy

by

Peter Temin

Published 17 Mar 2017

He won election to the presidency through a Southern Strategy that appealed to Southern racism and opposition to the Civil Rights Movement. He abandoned Johnson’s War on Poverty and declared a War on Drugs in 1971. He also abandoned the fixed exchange rate of the Bretton Woods system to deal with the strain on the dollar exerted by the expanding war in Vietnam.2 Nixon switched the United States to a floating exchange rate, transferring responsibility for the domestic economy from the federal government, which controls fiscal policy, to the Federal Reserve System, which controls monetary policy. The Fed had been securing the exchange rate for the previous quarter century, and it had to learn how to fulfill its new role.

Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation

by

Byrne Hobart

and

Tobias Huber

Published 29 Oct 2024

Effectively, it internationalized the gold standard, as the International Monetary Fund was tasked with coordinating between countries and intervening in capital flows with the aim of achieving exchange rate stability and equilibrating financial flows. But in 1971, due to increased public debt incurred by the Vietnam War, Great Society programs, and monetary inflation, it became too costly for the US government to back dollars with gold. As a result, the Bretton Woods system—and the convertibility of the US dollar to gold—was terminated. While President Nixon’s “closing of the gold window” was designed to be temporary, the resulting monetary system endured. 20 Divorced from gold’s physicality and unbounded from a reality anchor, the US dollar became a fiat currency—a virtual abstraction. The floating-fiat currency system ushered in the dawn of a new age of total financialization and dematerialized money.

How Markets Fail: The Logic of Economic Calamities

by

John Cassidy

Published 10 Nov 2009

By the early 1970s, under the onslaught of rising government spending, globalization, and growing demand for natural resources, the social contract between workers and corporations that underpinned the postwar boom was fraying badly, and so were other features of the Keynesian settlement, such as modest inflation and the Bretton Woods monetary system. Free market economics offered an intellectual alternative to the Kennedy-Johnson-Nixon consensus, which was known in the United Kingdom as “Butskellism.” Securitization and the rise of the stock market provided an alternative means of mobilizing and disciplining the economy. If corporate managers and government officials couldn’t restructure declining industries, control the budget deficit, and boost languishing profit rates, perhaps financial markets could do the job.

The Long Game: China's Grand Strategy to Displace American Order

by

Rush Doshi

Published 24 Jun 2021

But the muscle memory of the New Deal remained: the United States built federally supported institutions for research and education that made the country a technological leader for decades. Declinism crested in a long, third wave in the 1960s and 1970s that tested the faith of Kissinger, Zumwalt, and countless others in the country’s resilience. The United States went through social unrest and political assassinations; the collapse of Bretton Woods and the arrival of stagflation; the impeachment of President Richard Nixon and the fall of Saigon—all set against the backdrop of Soviet advancement. But eventually even these developments brought adjustment and renewal. Social unrest propelled civil rights reforms, impeachment reaffirmed the rule of law, Bretton Woods’ collapse brought eventual dollar dominance, defeat in Vietnam ended the draft, and the Soviet Union’s Afghan invasion hastened its collapse.

Market Wizards: Interviews With Top Traders

by

Jack D. Schwager

Published 7 Feb 2012

Anatomy of the Bear: Lessons From Wall Street's Four Great Bottoms

by

Russell Napier

Published 18 Jan 2016

As early as 1960, Yale Professor Robert Triffin had warned, in his book Gold and the Dollar Crisis, that the US would be forced to run regular current account deficits to provide the rest of the world with the necessary liquidity to grow. [69] He pointed out that the long-term result of these deficits would be to undermine faith in the dollar as the world reserve currency and thus the stability of the Bretton Woods system itself. Eleven years later, Triffin’s prediction came to pass when, on 15 August 1971, President Nixon declared the US was suspending the redemption of dollars for gold. The US dollar devalued in December 1971, from $35 to $38 an ounce of gold, and early in 1973 it was devalued to $42. By March 1973, any possibility of resurrecting Bretton Woods was dead and the dollar entered free float.

Rogue States

by

Noam Chomsky

Published 9 Jul 2015

The decisions were based on the belief that liberalization of finance may interfere with trade and economic growth, and on the clear understanding that it would undermine government decisionmaking, hence also the welfare state, which had enormous popular support. Not only the social contract that had been won by long and hard struggle, but even substantive democracy, would be damaged by loss of control on capital movements. The Bretton Woods system remained in place through the “golden age” of economic growth and significant welfare benefits. It was dismantled by the Nixon administration, with the support of Britain and others. This was a major factor in the enormous explosion of capital flows in the years that followed. Their composition also changed radically. In 1970, 90 percent of transactions were related to the real economy (trade and long-term investment).

Roller-Coaster: Europe, 1950-2017

by

Ian Kershaw

Published 29 Aug 2018

The Bretton Woods system had been built around a fixed price of gold, 35 dollars per ounce. The weakness of the dollar fostered speculation that the price of gold would rise. It did. By the end of the 1960s gold was selling for more than double the official price. Bretton Woods was no longer sustainable. On 15 August 1971 President Richard Nixon suddenly announced a dramatic shift in American policy: amid a raft of anti-inflationary measures, he suspended the gold convertibility of the dollar. With that move, the Bretton Woods system – the basis of the post-war economy – was dead. Floating exchange rates were the future.

Chokepoints: American Power in the Age of Economic Warfare

by

Edward Fishman

Published 25 Feb 2025

To confront the “speculators” who were “waging all-out war on the American dollar,” Nixon declared that the United States would no longer honor requests to convert dollars for gold. In one fell swoop, the announcement cut down the central pillar of Bretton Woods and essentially forced the global financial system to adopt floating exchange rates. Under Bretton Woods, currency values had been set by agreement among governments; after the “Nixon shock,” they were set by the market. It was the dawn of a new era for the world economy—one in which financial markets, contrary to Keynes’s wishes, would reign supreme. Many contemporary observers viewed the Nixon shock as the end of U.S. economic hegemony.

Year 501

by

Noam Chomsky

Published 19 Jan 2016

Understanding Power

by

Noam Chomsky

Published 26 Jul 2010

The Making of Global Capitalism

by

Leo Panitch

and

Sam Gindin

Published 8 Oct 2012

Saville, eds., Socialist Register 1973, London: Merlin, 1973; Paul Sweezy and Harry Magdoff, “The Doccar Crisis,” Monthly Review 28:1 (May 1973); and Ernest Mandel, Late Capitalism, London: Verso, 1975, esp. Chapter 10. 6 Eric Helleiner in particular has presented the outcome of the Bretton Woods crisis in terms of the American state—well-armed with neoliberal Friedmanite ideas under Nixon and his successors—imposing its free-market will against European and Japanese states who were more prepared to use multilateral capital controls. See his States and the Reemergence of Global Finance, esp. Chapter 5. 7 “The postwar growth of our trading partners was in fact encouraged as a deliberate act of American policy”: Volcker and Gyohten, Changing Fortunes, pp. xv. 8 Andrew Baker, The Group of Seven: Finance Ministries, Central Banks and Global Financial Governance, London: Routledge, 2006, pp. 11, 27. 9 Philip Armstrong, Andrew Glyn and John Harrison, Capitalism Since 1945, Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1991, Data Appendix, Table A2. 10 US Bureau of Economic Analysis, Fixed Assets Accounts, Table 4.2.

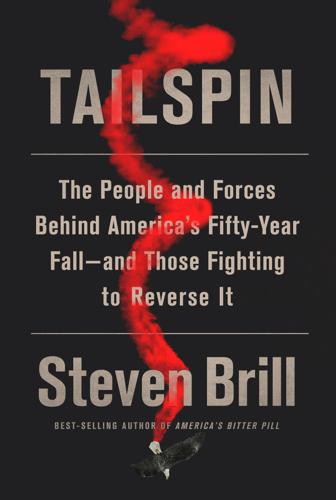

Tailspin: The People and Forces Behind America's Fifty-Year Fall--And Those Fighting to Reverse It

by

Steven Brill

Published 28 May 2018

Deal arbitrage was a pure—and purely vicarious—bet from the sidelines on the bets being made by the raiders. What the company in play actually produced did not matter. Money, itself, became the focus of another betting parlor. In 1971, the collapse of the Bretton Woods international accords—which had locked in the relative value of major currencies since 1944—accompanied by President Richard Nixon’s decision to let the value of the dollar float freely, created a new market for speculating in the fluctuation of exchange rates. With technology emerging to facilitate trades around the world instantaneously, knowledge workers had new pieces of paper (francs, dollars, pounds) to trade for other pieces of paper.

Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World

by

Adam Tooze

Published 31 Jul 2018