Oscar Wyatt

description: an American businessman convicted of conspiracy to commit wire fraud in relation to the UN's Oil-for-Food Programme.

9 results

The World for Sale: Money, Power and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources

by

Javier Blas

and

Jack Farchy

Published 25 Feb 2021

Theodor Weisser’s company, Mabanaft, used its profits to build one of the world’s largest oil storage businesses, called Oiltanking, which became a multi-billion dollar company with assets across five continents. Other adventurers and businessmen soon elbowed themselves into the oil trading industry. Among them were Gerd Lutter of Marimpex; Oscar Wyatt of Coastal Corporation; David Chalmers of Bayoil; and the Koch brothers. Lutter would spend years courting Soviet and Iranian officials to secure oil deals, supplying South Africa with millions of barrels at the height of apartheid. Wyatt, an American oil tycoon who branched out into trading after his first gas business almost went bankrupt, would be a pioneer of the oil trade between China and the US.

…

Hall had locked in a modest profit using futures to hedge the price; now he could unlock a much bigger gain by selling his oil on the spot market and buying back the lower-priced hedges. Cash was flowing in. ‘We made six, seven, eight hundred million dollars,’ Hall says. The trade wasn’t over, however. The conflict dragged on throughout 1990, and the world’s oil traders followed every twist and turn in real time on CNN. One trader, Oscar Wyatt of Coastal Petroleum, got significantly closer to the action, using his personal relationship with Saddam Hussein to secure the release of two dozen American hostages. Wyatt, a hard-bitten Texan, who had been buying Iraqi oil since 1972, flew in to Baghdad in December 1990 – despite a direct request from the White House not to – and persuaded Saddam to allow him to take back to the US a group of Americans who had been held in Iraq as human shields. 17 The US was edging closer to entering the war, and Hall remained bullish.

…

The UN created the oil-for-food programme: Iraq could sell its crude on the international market, but all the proceeds would go into an account in New York controlled by the UN, and the money would be used to buy food, medicines and a few other necessities. For the international community, it was a way to keep Saddam under control while alleviating the devastating effect of the sanctions on the Iraqi people. The commodity traders were the first in line for Iraqi oil: Oscar Wyatt, the founder of Coastal Petroleum, got the first cargo when the embargo was lifted in 1996. He was an old hand in Iraq: it was Wyatt who had travelled to Baghdad in the middle of the Gulf War in 1990 to rescue the Americans that Saddam had been using as human shields. Soon, he was joined by other traders and oil majors seeking cheaper sources of crude in the tough markets of the late 1990s.

The Predators' Ball: The Inside Story of Drexel Burnham and the Rise of the JunkBond Raiders

by

Connie Bruck

Published 1 Jun 1989

In a deal that started hostile but turned friendly, the Coastal Corporation was acquiring American Natural Resources Company for $2.46 billion—$1.6 billion of it from bank loans and $600 million from Milken’s junk (an amalgam of notes, or debt, with high-yielding interest and preferred stock with high-yielding dividends). Oscar Wyatt, chairman and CEO of Coastal, had become a sudden star. There were lots of people at this conference who were shaking Wyatt’s hand, wishing him luck—and picturing themselves in his shoes. One of them was Nelson Peltz. Just a week earlier, Triangle Industries, a company with a $50 million net worth run by Peltz and Peter May, two unknowns, had made a $456 million bid for National Can, to be wholly financed by Milken’s junk bonds.

…

It must have not only excited but tickled the fancy of Milken, an amateur magician who occasionally does tricks for his friends, to be able to wave this particular wand. The honored guests of this conference, therefore, were the takeover artists and their biggest backers—men like T. Boone Pickens, Carl Icahn, Irwin Jacobs, Sir James Goldsmith, Oscar Wyatt, Saul Steinberg, Ivan Boesky, Carl Lindner, the Belzbergs—and lesser lights about to shine, such as Nelson Peltz, Ronald Perelman, William Farley. The names tend to meld into a kind of raiders’ litany, but they are not all the same. For Milken, they would have separate roles during the coming months, performing discrete functions in a vast, interlocking machine of which he alone would know all the parts.

…

It was an evolving strategy, changing slightly each time it was implemented. Thus far Milken had launched the junk-bond-financed hostile takeover on behalf of T. Boone Pickens, in Mesa’s run at Gulf; Saul Steinberg, in Reliance’s bid for Disney; Carl Icahn, in his bid for Phillips Petroleum; and Oscar Wyatt, in Coastal Corporation’s bid for American Natural Resources (ANR). Only one of these targets, ANR, had actually been acquired—less than a month before Triangle made its offer for National Can. Even for Drexel—home of the underdog and the proverbial outsider—Peltz and May were small-time. All they had to their names was a controlling interest in a tired old vending-machine, wire and cable company, Triangle Industries—its 1984 revenues were $291 million, compared to National Can’s $1.9 billion—plus about $130 million of cash that first L.

The Achilles Trap: Saddam Hussein, the C.I.A., and the Origins of America's Invasion of Iraq

by

Steve Coll

Published 27 Feb 2024

“Saddam has not the slightest idea of distracting Clinton” from his domestic policies, Aziz assured Samir Vincent, an Iraqi-born American scientist and businessman who offered to serve as an intermediary between Baghdad and Washington. “Saddam wants to work with Clinton and reach agreements.”[15] Oscar Wyatt, the Texas oilman, also ferried messages from Saddam to the White House that winter. Texas Monthly once described the oilman as Houston’s “orneriest, wiliest, most litigious, most feared, most hated, and most beloved son of a bitch.” Wyatt flew into Iraq in January 1993, on his private jet, to lobby Saddam’s aides for a lucrative concession in Iraqi fields—U.N. resolutions be damned.

…

Saddam held to his refusal, even as he watched the size of Iraq’s economy shrink from $180 billion in 1990 to about $13 billion at the end of 1995, crushed by sanctions and weak oil prices.[5] Nonetheless, Aziz persisted in exploring Oil-for-Food, and Saddam did not stop him. The opportunity to profit from Iraqi oil remained a powerful calling card. Samir Vincent, the Iraqi-born scientist and consultant working for Texas wildcatter Oscar Wyatt, got involved. In 1993, Tongsun Park introduced him to Boutros-Ghali. Park emphasized the need for payments by Iraq to influential friends, to smooth the process. “Some of these people need to be taken care of,” Park said, according to Vincent.[6] Saddam wanted a deal that would maximize Iraq’s control over who profited from Iraqi oil sales and humanitarian imports while minimizing U.N. oversight of the program’s administration inside Iraq.

…

I want to repeat my loyalty to my Arab friends in Iraq. . . . I call on my friends in Iraq to assist in my reelection campaign.”[10] It didn’t work. Albright’s lobbying defeated Boutros-Ghali, clearing the way for the election of Kofi Annan, a Ghanaian diplomat, as his successor. In December, following delays, Oscar Wyatt became the first U.S. oilman to receive an allocation of Iraqi crude under the U.N. program that Boutros-Ghali left as a legacy—eight million barrels. * * * — The role played by wildcatters and influence peddlers in the negotiation of Oil-for-Food partly reflected the prolonged absence of professional diplomacy between Iraq and America.

Oil: Money, Politics, and Power in the 21st Century

by

Tom Bower

Published 1 Jan 2009

Big Oil was accused of profiteering from rationing supplies, and Rich was in the firing line after the seizure on November 4, 1979, of 52 American diplomats in Tehran. His profiteering from America’s humiliation sparked a federal investigation into suspected tax evasion. Rich’s success also aroused the interest of two independent oil traders: Oscar Wyatt, an American famous for running over anyone who got in his way, and John Deuss, alias “the Alligator,” a scarred buccaneer based in Bermuda, born 200 years too late. The son of a Ford plant manager in Amsterdam, Deuss’s early career as a car dealer had ended in bankruptcy. His next occupation was bartering oil between opportunistic producers and South Africa and Israel, both of which were excluded from normal trade by embargoes.

…

Just as Vitol hoped to escape censure for that trade, the directors did not anticipate any repercussions if their company bought Iraqi oil in breach of UN sanctions. Knowing that the sale of Iraqi crude was assured to those refineries that were calibrated to process it, Vitol’s skill was to negotiate with Iraqi officials the amount of dollars to be deposited as “commission” in return for the oil. Like Oscar Wyatt in New York, Vitol knew that those payments, or “surcharges,” broke UN sanctions, but none of the traders involved expected any legal consequences. Faced with such ruthlessness, Jorge Montepeque’s mechanisms to control the traders were, in the opinion of Carl Calabro, Littlejohn’s successor, not “failsafe.”

…

Chevron, in common with Glencore, Vitol and many Russian and Swiss traders, profited from that illegal trade. Vitol would plead guilty in November 2007 to grand larceny, pay a fine of $17.4 million and promise to abandon the cowboy era and legitimize itself because, with crude so expensive, it, like Glencore, needed banks to finance its trade; Oscar Wyatt of Coastal would be fined $11 million and sentenced to one year and a day’s imprisonment; Chevron paid $30 million to settle corruption charges. Trafigura was also swept into the opprobrium. In August 2006, a tanker chartered by the trader had unloaded cargo at Abidjan, in Ivory Coast, and later dumped toxic waste into the ocean.

The Secret World of Oil

by

Ken Silverstein

Published 30 Apr 2014

If you don’t have it, you can’t run your country.” Key brokers who emerged in the post-1973 OPEC world included: Marc Rich, who founded the giant commodities firm Glencore (see Chapter 3); Hany Salaam, a Lebanese middleman who made numerous deals for Occidental Petroleum Corporation during the days of Armand Hammer, its former chairman; and Oscar Wyatt, a Houston oilman and corporate raider who was sentenced to a year in prison in 2007 in connection with the UN oil-for-food scandal. One of the more colorful of that era’s fixers was John Deuss, who once owned his own tanker fleet, and who during the 1980s smuggled vast quantities of oil to South Africa’s apartheid regime, then under an international trade embargo imposed by the United Nations.

Billion Dollar Whale: The Man Who Fooled Wall Street, Hollywood, and the World

by

Tom Wright

and

Bradley Hope

Published 17 Sep 2018

Then, he set about laundering the proceeds of his stake sale to Mubadala through yet another corporate acquisition, and Goldman, of course, would be involved. Low had been deepening his connections at Goldman, and had gotten to know Hazem Shawki, the bank’s Dubai-based head of investment banking, who heard pitches from the Malaysian. One of them involved a plan for Low to take over Coastal Energy, a Houston firm controlled by legendary Texas oilman Oscar Wyatt Jr. Low, informally advised by Goldman, approached Coastal in 2012 about a takeover, but the firm didn’t believe he could come up with cash and told him to find a bigger partner. Now armed with cash from the Park Lane sale, Low returned with none other than IPIC, the Abu Dhabi fund controlled by Khadem Al Qubaisi, who had helped funnel money out from the first 1MDB bonds sold by Goldman.

The Asylum: The Renegades Who Hijacked the World's Oil Market

by

Leah McGrath Goodman

Published 15 Feb 2011

“Whoever these spies are, they’re getting in the way of trading in the oil ring. Nobody wants to stand near them. The whole floor is moving away, so you have these two guys standing there basically trying to do trades by themselves.” He asked around and found out both men worked for Texas oil man and corporate raider Oscar Wyatt Jr. Until being incarcerated in 2007 for sluicing kickbacks to Saddam Hussein’s regime, Wyatt led a charmed life, running Coastal Corp., an oil company he sold to Texas competitor El Paso Corp. in 2001 for $24 billion, after repeatedly inflaming the U.S. Justice Department by inking foreign oil deals with countries like Libya.

Den of Thieves

by

James B. Stewart

Published 14 Oct 1991

That year's guest list was practically a who's-who of self-made multimillionaires of the 80s: Merv Adelson, Norman Alexander, Henry Kravis, George Roberts, Boone Pickens, John Kluge, Fred Carr, Marvin Davis, Barry Diller, William Farley, Harold Geneen, Rupert Murdoch, Steve Ross, Ron Perelman, Peter Grace, Sam Heyman, Carl Icahn, Ralph Ingersoll, Irwin Jacobs, William McGowan, David Mahoney, Martin Davis, John Malone, Peter Ueberroth, David Murdock, Jay and Robert Pritzker, Samuel and Mark Belzberg, Carl Lindner, Nelson Peltz, Saul Steinberg, Craig McCaw, Frank Lorenzo, Peter May, Steve Wynn, James Wolfensohn, Oscar Wyatt, Gerald Tsai, Roger Stone, Harold Simmons, Sir James Goldsmith, Mel Simon, Henry Gluck, Ray Irani, Peter Magowan, Alan Bond, Ted Turner, Robert Maxwell, Kirk Kerkorian. Mingling with them were key Drexel corporate finance and bond salesmen, such as Siegel, Ackerman, and Dahl. Boesky arrived, accompanied by two bodyguards.

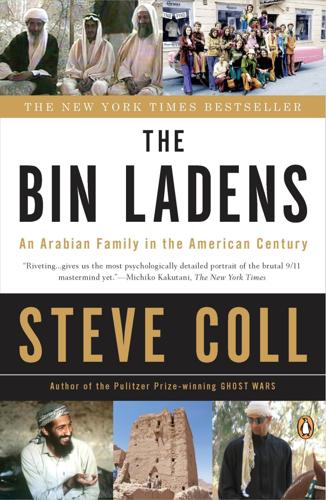

The Bin Ladens: An Arabian Family in the American Century

by

Steve Coll

Published 29 Mar 2009

Reagan was a master of the theatrical and ceremonial aspects of his office, and he prepared to put on a show. Up the White House driveway they strolled on the chilly night of February 11—Yogi Berra, the New York Yankees manager; Vice President George Bush; Linda Gray, star of Dallas, the television series about oil barons; Oscar Wyatt, the genuine Texas oil baron; the actress Sigourney Weaver; and Donald and Ivana Trump. “It’s exciting. It’s Americana. It’s Ronald Reagan,” joked Saturday Night Live comedian Joe Piscopo, who was also on the state dinner’s guest list. “The king of Saudi Arabia came here to see how a real king lives, I suppose.”14 Saudi royals do not travel on official business with their wives, so the king escorted Abdulaziz, his eleven-year-old son by Princess Jawhara Al-Ibrahim.