PageRank

description: algorithm for calculating the authority of a web page based on link structure.

89 results

In the Plex: How Google Thinks, Works, and Shapes Our Lives

by

Steven Levy

Published 12 Apr 2011

The first assigned reading was their own paper, but later in the semester a class was devoted to a comparison of PageRank and Kleinberg’s work. In December, after the final projects were due, Page emailed the students a party invitation that also marked a milestone: “The Stanford Research Project is now Google.com: The Next Generation Internet Search Company.” “Dress is Tiki Lounge wear,” the invitation read, “and bring something for the hot tub.” 2 “We want Google to be as smart as you.” Larry Page did not want to be Tesla’d. Google had quickly become a darling of everyone who used it to search the net. But at first so had AltaVista, and that search engine had failed to improve.

…

Cutts noticed that one nasty site used some clever methods to game Google’s blocking system and score high in search results. “It was an eye-opening moment,” says Cutts. “Page-Rank and link analysis may be spam-resistant, but nothing is spam-proof.” The problem went far beyond porn. Google had won its audience in part because it had been effective in eliminating search spam. But now that Google was the dominant means of finding things on the Internet, a high ranking for a given keyword could drive millions of dollars of business to a site. Sites were now spending time, energy, and technical wizardry to deconstruct Google’s processes and artificially boost page rank. The practice was called search engine optimization, or SEO.

…

But when he told his boss, Dow Jones reasserted itself and hired a lawyer to review the patent, which it refiled in February 1997. (Stanford University would not file its patent for Larry Page’s PageRank system until January 1998.) Nonetheless, Dow Jones did nothing with Li’s system. “I tried to convince them it was important, but their business had nothing to do with Internet search, so they didn’t care,” he says. Robin Li quit and joined the West Coast search company called Info-seek. In 1999, Disney bought the company and soon thereafter Li returned to China. It was there in Beijing that he would later meet—and compete with—Larry Page and Sergey Brin. Page and Brin had launched their project as a stepping-stone to possible dissertations.

Nine Algorithms That Changed the Future: The Ingenious Ideas That Drive Today's Computers

by

John MacCormick

and

Chris Bishop

Published 27 Dec 2011

For readers with a computer science background, Search Engines: Information Retrieval in Practice, by Croft, Metzler, and Strohman, is a good option for learning more about indexing and many other aspects of search engines. PageRank (chapter 3). The opening quotation by Larry Page is taken from an interview by Ben Elgin, published in Businessweek, May 3, 2004. Vannevar Bush's “As We May Think” was, as mentioned above, originally published in The Atlantic magazine (July 1945). Bishop's lectures (see above) contain an elegant demonstration of PageRank using a system of water pipes to emulate hyperlinks. The original paper describing Google's architecture is “The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine,” written by Google's co-founders, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, and presented at the 1998 World Wide Web conference.

…

But one of the most important factors, especially in those early days, was the innovative algorithm used by Google for ranking its search results: an algorithm known as PageRank. The name “PageRank” is a pun: it's an algorithm that ranks web pages, but it's also the ranking algorithm of Larry Page, its chief inventor. Page and Brin published the algorithm in 1998, in an academic conference paper, “The Anatomy of a Large-scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine.” As its title suggests, this paper does much more than describe PageRank. It is, in fact, a complete description of the Google system as it existed in 1998. But buried in the technical details of the system is a description of what may well be the first algorithmic gem to emerge in the 21st century: the PageRank algorithm.

…

As we already know, efficient matching is only half the story for an effective search engine: the other grand challenge is to rank the matching pages. And as we will see in the next chapter, the emergence of a new type of ranking algorithm was enough to eclipse AltaVista, vaulting Google into the forefront of the world of web search. 3 PageRank: The Technology That Launched Google The Star Trek computer doesn't seem that interesting. They ask it random questions, it thinks for a while. I think we can do better than that. —LARRY PAGE (Google cofounder) Architecturally speaking, the garage is typically a humble entity. But in Silicon Valley, garages have a special entrepreneurial significance: many of the great Silicon Valley technology companies were born, or at least incubated, in a garage.

The Googlization of Everything:

by

Siva Vaidhyanathan

Published 1 Jan 2010

Unfortunately, universities have allowed Google to take the lead in and set the terms of the relationship. There is a strong cultural affinity between Google corporate culture and that of academia. Google’s founders, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, THE GOOGL I ZAT I ON OF ME MORY 187 met while pursuing PhDs in computer science at Stanford University.16 The foundational concept behind Google Web Search, the PageRank algorithm, emerged from an academic paper that Brin and Page wrote and published in 1999.17 Page did his undergraduate work at the University of Michigan and retains strong ties with that institution. Some of the most visionary Google employees, such as the University of California at Berkeley economist Hal Varian, suspended successful academic careers to join the company.

…

Many companies have the former. Only Google, Yahoo, and Microsoft have the latter. Of those, Google leads the pack. It’s no accident that Google has enthusiastically scanned and “read” millions of books from some of the world’s largest libraries. It wants to collect enough examples of grammar and diction in enough languages from enough places to generate the algorithms that can conduct naturallanguage searches. Google already deploys some elements of semantic analysis in its search process. PageRank is no longer flat and democratic. When I typed “What is the capital of Norway?” into Google in August 2010, the top result was “Oslo” from the Web Definitions site hosted by Princeton University.

…

Links are a sort of currency on the Web because those who make Web pages usually understand that GOOGL E ’S WAYS A ND ME A N S 63 Google rewards them, but no such ethic exists generally among commercial sites. By relying on PageRank, Google has historically favored highly motivated and Web-savvy interests over truly popular, important, or valid interests. Being popular or important on the Web is not the same as being popular or important in the real world. Google tilts toward the geeky and Webby, as well as toward the new and loud. For example, if you search for “God” on Google Web Search, as I did on July 15, 2009, from my home in Virginia, you could receive a set of listings that reflect the peculiar biases of PageRank.

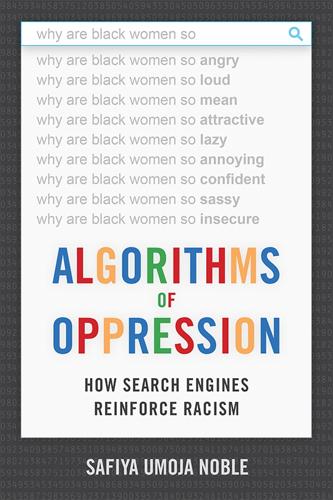

Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism

by

Safiya Umoja Noble

Published 8 Jan 2018

The lawsuit by Search King and PR Network against Google alleged that Google decreased the page rank of its clients in a direct effort to annihilate competition.13 Since Bob Massa, the president of Search King and PR Ad Network, issued a statement against Google’s biased ranking practices, Google’s business practices have been under increased scrutiny, both in the U.S. and globally. Why Public Policy Matters Given the controversies over commercial, cultural, and ethnic representations of information in PageRank, the question that the Federal Trade Commission might ask today, however, is whether search engines such as Google should be regulated over the values they assign to racial, gendered, and sexual identities, as evidenced by the types of results that are retrieved.

…

See also Prodigy Flaherty, Colin, 104 Fleisher, Peter, 128 Ford, Thomas E., 89 Foskett, Anthony Charles, 136 Fouché, Rayvon, 108 France, “Charter of good practices on the right to be forgotten . . . ,” 121 FreePorn.com blog, 87 free speech and free speech protections, 46, 57, 172; corporate, 143 Fuchs, Christian, 162 Fujioka, Yuki, 89 Fuller, Matthew, 54 Furner, Jonathan, 135–36 Galloway, Alex, 148 Gandy, Oscar Jr., 85, 125 Gardner, Tracey A., 59 Gillespie, Tarleton, 26 Golash-Boza, Tanya, 80 Gold, Danny, 120 Goodman, Ellen P., 130 Google: apologies, 6; archives of non-public search results, 122, 129; competitors blocked, 56; critiques of, 28, 33, 36–37, 56, 163–64; data storage policies, 125–29; “diversity problems,” 64–65, 69, 163; mainstream corporate news conglomerates, 49; method of rebuilding index, 189n38; near-monopoly status, 34–36, 86, 156, 188n10, 198n32; privacy policy, 129–30; right to transparency of data removal, 130–31; surplus labor through free use, 162; underemployment of Black women, 69; unlawful page removal policy, 42; wage gap, 2 Google AdWords, 86–87, 106, 116; ‘black girls’ search results, 68, 86–87; cost per click (CPC), 46–47 Google bombing, 46–47, 189n47; George W. Bush and miserable failure, 48; Santorum, Rick, 47, 189n50 Google Books, 50, 86, 191n77; “fair use” ruling, 157 Google Glass: “Glassholes,” 164; neocolonial project, 164 Google Image Labeler, 188n27 Google Image Search, 6 Google Instant, X-rated front-page results, 155 Google Maps, search for “N*gger” yields White House, 6–8 Google PageRank, 11, 38–42, 46–47, 54, 158, 189n48 Google Search, 3–4, 86; algorithm control, 179; autocorrection to “himself,” 142; autosuggestions, 6, 11, 15, 20–21, 24; Black feminist perspective, 30–31; commercial environment influence, 24, 179; computer science for decision-making, 148–49; consumer protection, 188n10; disclaimer, 31, 42, 159; disclaimer for search for “Jew,” 44, 88n24, 143, 189n42; filters for advertisers, 45; front organizations for hate-based groups, 116–17; glitch tagging African Americans as “apes,” 6; image search, 6, 20–23, 191n73; prioritization of its properties, 162; priority ranking, 18, 32, 42, 63, 65, 118, 155, 158; public resource, 50; response to stereotypes, 82; sexism and discrimination, 15–16.

…

Judit Bar-Ilan, a professor of information science at Bar-Ilan University, has studied this practice to see if the effect of forcing results to the top of PageRank has a lasting effect on the result’s persistence, which can happen in well-orchestrated campaigns. In essence, Google bombing is the process of co-opting content or a term and redirecting it to unrelated content. Internet lore attributes the creation of the term “Google bombing” to Adam Mathes, who associated the term “talentless hack” with a friend’s website in 2001. Practices such as Google bombing (also known as Google washing) are impacting both SEO companies and Google alike. While Google is invested in maintaining the quality of search results in PageRank and policing companies that attempt to “game the system,” as Brin and Page foreshadowed, SEO companies do not want to lose ground in pushing their clients or their brands up in PageRank.48 SEO is the process of “using a range of techniques, including augmenting HTML code, web page copy editing, site navigation, linking campaigns and more, in order to improve how well a site or page gets listed in search engines for particular search topics,”49 in contrast to “paid search,” in which the company pays Google for its ads to be displayed when specific terms are searched.

Understanding search engines: mathematical modeling and text retrieval

by

Michael W. Berry

and

Murray Browne

Published 15 Jan 2005

Another more well-known, similar, linkage data approach is the PageRank algorithm developed by the founders of Google, Larry Page and Sergey Brin [49]. Page and Brin were graduate students at Stanford in 1998 when they published a paper describing the fundamental concepts of the PageRank algorithm, which later was used as the underlying algorithm that currently drives Google [49]. Unlike the HITS algorithm, where the results are created after the query is made, Google has the Web crawled and indexed ahead of time, and the links within these pages are analyzed before the query is ever entered by the user. Basically, Google looks not only at the number of links to The History of Meat and Potatoes website — referring to the earlier example — but also the importance of those referring links.

…

This problem alone should provide ample fodder for research in large-scale link-based search technologies. 7.2.3 PageRank Summary Similar to HITS, PageRank can suffer from topic drift. The importance of a webpage (as defined by its query-independent PageRank score) does not necessarily reflect the relevance of the webpage to a user's query. Unpopular yet very relevant webpages may be missed with PageRank scoring. Some consider this a major weakness of Google [15]. On the other hand, the query independence of PageRank has made Google a great success in the speed and ease of web searching. A clear advantage of PageRank over the HITS approach lies in its resilience to spamming.

…

If p — 0.85 is the fraction of time that the random walk (or Markov chain) follows an outlink and (1 — p) = 0.15 is the fraction of time that an arbitrary webpage is chosen (independent of the link structure of the web graph), then the derived PageRank vector x or normalized left-hand eigenvector of the modified stochastic (Google) matrix can be shown (with 4 significant decimal digits) to be Here, e? — (I 1 1 1 1) and x^ — e?/5. If the set of webpages judged relevant to a user's query is {1,2,3}, then webpage 3 would be ranked as the most relevant, followed by webpages 1 and 2, respectively. Figure 7.3: PageRank example using the 5-node graph from Figure 7.1. 7.2. PageRank Method 87 A rank-1 perturbation8 of the n x n stochastic matrix A defined by models random surfing of the Web in that not all webpages are accessed via outlinks from other pages.

Life After Google: The Fall of Big Data and the Rise of the Blockchain Economy

by

George Gilder

Published 16 Jul 2018

By every measure, the most widespread, immense, and influential of Markov chains today is Google’s foundational algorithm, PageRank, which encompasses the petabyte reaches of the entire World Wide Web. Treating the Web as a Markov chain enables Google’s search engine to gauge the probability that a particular Web page satisfies your search.5 To construct his uncanny search engine, Larry Page paradoxically began with the Markovian assumption that no one is actually searching for anything. His “random surfer” concept makes Markov central to the Google era. PageRank treats the Internet user as if he were taking a random walk across the Web, which we users know is not what we are doing.

…

Indeed, in a sense omega is the crystalized, concentrated essence of mathematical creativity.” Chapter 3: Google’s Roots and Religions 1. http://citeseer.ist.psu.edu/stats/articles. I counted the Stanford and Google papers. 2. A lucid explanation of PageRank and search technology is John MacCormick, Nine Algorithms that Changed the Future: The Ingenious Ideas that Drive Today’s Computers (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 10–37. 3. Larry Page, hey, virtually all his quotes are accessible on Google! 4. David Gelernter, Mirror Worlds (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992). 5. Page, ibid. 6. If you prefer the text version beyond all the Google search resources on the saga of its inventors and founders, it is lavishly there in Steven Levy’s In the Plex: How Google Thinks, Works, and Shapes our Lives (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), or in the silken New Yorker prose of media-savvy Ken Auletta, Googled: The End of the World as We Know It (New York: Penguin Books, 2010).

…

Although still based in New York, Blockstack chose the Computer Museum in Mountain View, minutes from the Google campus, for its coming-out party: the Blockstack Summit 2017. Its marketing chief, Patrick Stanley, asked me to speak on “Life after Google.” A little more than two weeks before, Ali’s doctoral committee at Princeton had finally approved his dissertation, “Trust-to-Trust Design of a New Internet.” Composed with Shea’s help, it was comparable in its scope and ambition to Larry Page’s “PageRank” thesis at Stanford. Ali makes the case for a new Internet architecture and then declares that, in prototype, it has already been in place for three years, requiring only 44,344 lines of Python software language code.

The Innovators: How a Group of Inventors, Hackers, Geniuses and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution

by

Walter Isaacson

Published 6 Oct 2014

That’s when it dawned on the BackRub Boys that their index of pages ranked by importance could become the foundation for a high-quality search engine. Thus was Google born. “When a really great dream shows up,” Page later said, “grab it!”149 At first the revised project was called PageRank, because it ranked each page captured in the BackRub index and, not incidentally, played to Page’s wry humor and touch of vanity. “Yeah, I was referring to myself, unfortunately,” he later sheepishly admitted. “I feel kind of bad about it.”150 That page-ranking goal led to yet another layer of complexity. Instead of just tabulating the number of links that pointed to a page, Page and Brin realized that it would be even better if they could also assign a value to each of those incoming links.

…

s=Lost+Google+Tapes; John Ince, “Google Flashback—My 2000 Interviews,” Huffington Post, Feb. 6, 2012; Ken Auletta, Googled (Penguin, 2009); Battelle, The Search; Richard Brandt, The Google Guys (Penguin, 2011); Steven Levy, In the Plex (Simon & Schuster, 2011); Randall Stross, Planet Google (Free Press, 2008); David Vise, The Google Story (Delacorte, 2005); Douglas Edwards, I’m Feeling Lucky: The Confessions of Google Employee Number 59 (Mariner, 2012); Brenna McBride, “The Ultimate Search,” College Park magazine, Spring 2000; Mark Malseed, “The Story of Sergey Brin,” Moment magazine, Feb. 2007. 116. Author’s interview with Larry Page. 117. Larry Page interview, Academy of Achievement. 118. Larry Page interview, by Andy Serwer, Fortune, May 1, 2008. 119. Author’s interview with Larry Page. 120. Author’s interview with Larry Page. 121. Author’s interview with Larry Page. 122. Larry Page, Michigan commencement address. 123.

…

In addition to the sources cited below, this section is based on my interview and conversations with Larry Page; Larry Page commencement address at the University of Michigan, May 2, 2009; Larry Page and Sergey Brin interviews, Academy of Achievement, Oct. 28, 2000; “The Lost Google Tapes,” interviews by John Ince with Sergey Brin, Larry Page, and others, Jan. 2000, http://www.podtech.net/home/?s=Lost+Google+Tapes; John Ince, “Google Flashback—My 2000 Interviews,” Huffington Post, Feb. 6, 2012; Ken Auletta, Googled (Penguin, 2009); Battelle, The Search; Richard Brandt, The Google Guys (Penguin, 2011); Steven Levy, In the Plex (Simon & Schuster, 2011); Randall Stross, Planet Google (Free Press, 2008); David Vise, The Google Story (Delacorte, 2005); Douglas Edwards, I’m Feeling Lucky: The Confessions of Google Employee Number 59 (Mariner, 2012); Brenna McBride, “The Ultimate Search,” College Park magazine, Spring 2000; Mark Malseed, “The Story of Sergey Brin,” Moment magazine, Feb. 2007. 116.

I'm Feeling Lucky: The Confessions of Google Employee Number 59

by

Douglas Edwards

Published 11 Jul 2011

But that didn't stop me from casually dropping it into conversations with engineers: "Oh, yeah, that press release is totally orthogonal to the ads we're running on Yahoo." Overture: The name assumed by the advertising network GoTo in October 2001. PageRank: An algorithm used for analyzing the relative importance of pages on the web. Written by, and named for, Google's co-founder Larry Page. PageRank's breakthrough approach was to look at the sites linking to a particular page to determine how many other websites deemed that page authoritative or important. Pay for inclusion: Some search engines accept payment from website owners to guarantee that their sites will be included in search results.

…

PageRank was Google's assessment of the importance of a page, determined by looking at the importance of the sites that linked to it. So, knowing a page's PageRank could give you a feel for whether or not Google viewed a site as reliable. It was just the sort of geeky feature engineers loved, because it provided an objective data point from which to form an opinion. All happiness and joy. Except that when the "advanced features" were activated, they also gave Google a look at every page a user viewed. To tell you the PageRank of a site, Google needed to know what site you were visiting. The Toolbar sent that data back to Google if you let it, and Google would show you the green bar. The key was "if you let it," because you could also download a version of the toolbar that would not send any data back to Google.

…

"Once we have an index," Craig continued, "we assign a rank to each page based on its importance with our PageRank algorithm. PageRank is Google's secret sauce." "Secret sauce?" I leaned forward to learn what we had that was better than all the other search engines that our founders seemed so quick to dismiss. "PageRank looks at all the pages on the web and assigns a value to them based on who else links to them. The more credible the sites linking to them, the higher the PageRank. That's the first half of the recipe." I wrote "pageRank" under the Ben Franklin spectacles and drew an oval around it. It looked a little like a clown mouth, so I sketched a skull around it and added some Bozo hair on the sides.

The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding From You

by

Eli Pariser

Published 11 May 2011

But when they released the beta site into the wild, the traffic chart went vertical. Google worked—out of the box, it was the best search site on the Internet. Soon, the temptation to spin it off as a business was too great for the twenty-something cofounders to bear. In the Google mythology, it is PageRank that drove the company to worldwide dominance. I suspect the company likes it that way—it’s a simple, clear story that hangs the search giant’s success on a single ingenious breakthrough by one of its founders. But from the beginning, PageRank was just a small part of the Google project. What Brin and Page had really figured out was this: The key to relevance, the solution to sorting through the mass of data on the Web was ... more data.

…

But at times, this attitude can verge on a “Guns don’t kill people, people do” mentality—a willful blindness to how their design decisions affect the daily lives of millions. That Facebook’s button is named Like prioritizes some kinds of information over others. That Google has moved from PageRank—which is designed to show the societal consensus result—to a mix of PageRank and personalization represents a shift in how Google understands relevance and meaning. This amorality would be par for the corporate course if it didn’t coincide with sweeping, world-changing rhetoric from the same people and entities. Google’s mission to organize the world’s information and make it accessible to everyone carries a clear moral and even political connotation—a democratic redistribution of knowledge from closed-door elites to the people.

…

It’s not a matter of math that keeps Google ahead, but the sheer number of people who use it every day. PageRank and the other major pieces of Google’s search engine are “actually one of the world’s worst kept secrets,” says Google fellow Amit Singhal. Google has also argued that it needs to keep its search algorithm under tight wraps because if it was known it’d be easier to game. But open systems are harder to game than closed ones, precisely because everyone shares an interest in closing loopholes. The open-source operating system Linux, for example, is actually more secure and harder to penetrate with a virus than closed ones like Microsoft’s Windows or Apple’s OS X.

Googled: The End of the World as We Know It

by

Ken Auletta

Published 1 Jan 2009

The company’s algorithms not only rank those links that generate the most traffic, and therefore are presumed to be more reliable, they also assign a slightly higher qualitative ranking to more reliable sources—like, for instance, a New York Times story. By mapping how many people click on a link, or found it interesting enough to link to, Google determines whether the link is “relevant” and assigns it a value. This quantified value is known as PageRank, after Larry Page. All this was interesting enough, but where the Google executives really got Karmazin’s attention was when they described the company’s advertising business, which accounted for almost all its revenues. Google offered to advertisers a program called AdWords, which allowed potential advertisers to bid to place small text ads next to the results for key search words.

…

Norman, Design of Everyday Things, Basic Books, 1988. 37 an obsession of Larry’s: author interview with Larry Page, March 25, 2008. 38 disdained games like golf: author interview with Omid Kordestani, April 15, 2008. 38 “two swords sharpening each other”: author interview with John Battelle, March 20, 2008. 38 “they were not”: author interview with Terry Winograd, September 25, 2007. 38 Page and Brin’s breakthrough: Search, John Battelle. 39 “they didn’t have this false respect”: author interview with Rajeev Motwani, October 12, 2007. 39 snuck onto the loading dock: author interview with Terry Winograd: September 16, 2008. 39 “We wanted to finish school”: Page and Schmidt appearance at Stanford, May 1, 2002, available on YouTube. 40 “You guys can always come back”: author interview with Larry Page, March 25, 2008; confirmed in a May 5, 2008 e-mail to the author from Jeffrey Ullman. 40 They chose the name Google: Sergey Brin interview with John Ince on PodVentureZone, January 2000. 40 “two important features”: Page and Brin, “The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine”; a printed version, “The PageRank Citation Ranking: Bringing Order to the Web,” was published January 29, 1998, and is available on the Web. 40 “Brin and Page . . . are expressing a desire”: Nicholas Carr, Big Switch: Rewiring the World, From Edison to Google, W. W. Norton & Company, 2008. 41 “They were . . . part of an engineering tribe”: author interview with Lawrence Lessig, March 30, 2009. 41 “This is going to change the way”: author interview with Rajeev Motwani, October 12, 2007. 41 “free of many of the old prejudices”: Nicholas Negroponte, Being Digital, Alfred A.

…

See Google advertising cookies, use by Google as default search for browsers development of future threats mechanism of on mobile devices name, choosing versus other search engines PageRank Google Ventures “Google Version 2.0: The Calculating Predator,” Google Video Google Voice Googzilla concept Gore, Al on Apple board and Google Google, view of on Steve Jobs Gotlieb, Irwin on ads and smart phones career of on misuse of data observations on Google outlook for future GoTo GrandCentral Gravel, Mike Green initiatives Gross, Bill Grouf, Nick Group M Hands Off the Internet Harik, George Hashim, Smita Health records, Google Health Hecht, Albie Heiferman, Scott Hennessy Stanford L.

Mining of Massive Datasets

by

Jure Leskovec

,

Anand Rajaraman

and

Jeffrey David Ullman

Published 13 Nov 2014

Haveliwala, “Efficient computation of PageRank,” Stanford Univ. Dept. of Computer Science technical report, Sept., 1999. Available as http://infolab.stanford.edu/~taherh/papers/efficient-pr.pdf [6]T.H. Haveliwala, “Topic-sensitive PageRank,” Proc. 11th Intl. World-Wide- Web Conference, pp. 517–526, 2002 [7]J.M. Kleinberg, “Authoritative sources in a hyperlinked environment,” J. ACM 46:5, pp. 604–632, 1999. 1 Link spammers sometimes try to make their unethicality less apparent by referring to what they do as “search-engine optimization.” 2 The term PageRank comes from Larry Page, the inventor of the idea and a founder of Google. 3 They are so called because the programs that crawl the Web, recording pages and links, are often referred to as “spiders.”

…

Imagine, if you will, that the number of movies is extremely large, so counting ticket sales of each one separately is not feasible. 5 Link Analysis One of the biggest changes in our lives in the decade following the turn of the century was the availability of efficient and accurate Web search, through search engines such as Google. While Google was not the first search engine, it was the first able to defeat the spammers who had made search almost useless. Moreover, the innovation provided by Google was a nontrivial technological advance, called “PageRank.” We shall begin the chapter by explaining what PageRank is and how it is computed efficiently. Yet the war between those who want to make the Web useful and those who would exploit it for their own purposes is never over. When PageRank was established as an essential technique for a search engine, spammers invented ways to manipulate the PageRank of a Web page, often called link spam.1 That development led to the response of TrustRank and other techniques for preventing spammers from attacking PageRank.

…

Compute the hubs and authorities vectors, as a function of n. 5.6Summary of Chapter 5 ✦Term Spam: Early search engines were unable to deliver relevant results because they were vulnerable to term spam – the introduction into Web pages of words that misrepresented what the page was about. ✦The Google Solution to Term Spam: Google was able to counteract term spam by two techniques. First was the PageRank algorithm for determining the relative importance of pages on the Web. The second was a strategy of believing what other pages said about a given page, in or near their links to that page, rather than believing only what the page said about itself. ✦PageRank: PageRank is an algorithm that assigns a real number, called its PageRank, to each page on the Web. The PageRank of a page is a measure of how important the page is, or how likely it is to be a good response to a search query.

The Art of SEO

by

Eric Enge

,

Stephan Spencer

,

Jessie Stricchiola

and

Rand Fishkin

Published 7 Mar 2012

To help you understand the origins of link algorithms, the underlying logic of which is still in force today, let’s take a look at the original PageRank algorithm in detail. The Original PageRank Algorithm The PageRank algorithm was built on the basis of the original PageRank thesis (http://infolab.stanford.edu/~backrub/google.html) authored by Sergey Brin and Larry Page while they were undergraduates at Stanford University. In the simplest terms, the paper states that each link to a web page is a vote for that page. However, votes do not have equal weight. So that you can better understand how this works, we’ll explain the PageRank algorithm at a high level. First, all pages are given an innate but tiny amount of PageRank, as shown in Figure 7-1.

…

, Facebook Shares/Links as a Ranking Factor, Facebook Likes Are Votes, Too, Google+ Shares as a Ranking Factor, Google +1s Are Also an Endorsement, Impact of Google+ on Google Rankings, Ranking, Ranking, Ranking, Ranking, Ranking, Analysis of Top-Ranking Sites and Pages analysis of top-ranking sites and pages, Analysis of Top-Ranking Sites and Pages analyzing ranking factors, Analyzing Ranking Factors, Other Ranking Factors benchmarking current search rankings, Benchmarking Current Rankings critical role of links in, How Search Engines Use Links engagement with website as factor, Measuring Content Quality and User Engagement Facebook Likes affecting, Facebook Likes Are Votes, Too Facebook Shares/links as ranking factors, Facebook Shares/Links as a Ranking Factor getting data from Google, Ranking Google +1s as endorsement, Google +1s Are Also an Endorsement Google+ Shares as ranking factor, Google+ Shares as a Ranking Factor impact of Google+ on Google rankings, Impact of Google+ on Google Rankings influence of links, How Links Influence Search Engine Rankings, How Search Engines Use Links, The Original PageRank Algorithm, The Original PageRank Algorithm, Additional Factors That Influence Link Value, Trust additional factors in link value, Additional Factors That Influence Link Value, Trust original PageRank algorithm, The Original PageRank Algorithm, The Original PageRank Algorithm scenarios where data is helpful, Ranking testing of new ranking factors, How Social Media and User Data Play a Role in Search Results and Rankings tools for data on, Ranking tweets as ranking factors, How big a ranking factor are Tweets?

…

Your competitors are obviously ranking based on the strength of their links, so researching the sources of those links can provide insight into where they derive that value. PageRank of the domain Google does not publish a value for the PageRank of a domain (the PageRank values you can get from the Google Toolbar are for individual pages), but many believe that Google does calculate a Domain PageRank value. Most SEOs choose to use the PageRank of the website’s home page as an estimate of Domain PageRank. You can look at the PageRank of the home page to get an idea of whether the site is penalized and to get a crude sense of the potential value of a link from the site.

Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It

by

Cory Doctorow

Published 6 Oct 2025

Most of these projects went nowhere (most non–20 percent Google projects also went nowhere), but the 20 percent program is responsible for one of Google’s few post-Search, in-house successes: Gmail, invented by Paul Buchheit as a 20 percent project in 2004. Google’s founders came out of academia. Larry Page and Sergey Brin launched the company while completing their grad studies at Stanford. Clearly, some of Google’s cultural deference to technologists reflected the founders’ academic sensibilities—after all, those were the same sensibilities that led to the creation of the PageRank algorithm, which operationalized the academic practice of citation analysis. But from the very beginning, the Google Boys had adult oversight: consummate corporate types like Eric Schmidt, whose presence reassured the company’s investors about its commitment to profit.

…

Not only was Facebook able to operate without spying during that era, but that was also the best era of Facebook, the time when Facebook served you a feed consisting of the things you asked to see, not boosted content and ads (that is, the things Facebook’s shareholders wished you wanted to see). Google Search can be great without spying, too. We know that because the 1998 PageRank paper in which Sergey Brin and Larry Page laid out their plan for a “large-scale hypertextual web search engine” declared that “advertising funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers.” Which is why, during Google’s early years, the company did no commercial surveillance and served the best search results of its entire commercial life.

…

So a search for cat might yield several paid ads from companies hoping for your clicks, followed by several more spam results from keyword stuffers and other improbably successful spammers (or, as they would be called today, search engine optimizers). Between spammers and payola, the search engines were eating themselves from the inside even as parasites consumed them from without. Google had an answer for both pathologies. In “The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine,” better known as the PageRank paper, two Stanford grad students named Larry Page and Sergey Brin set out a method for sorting good web pages from bad ones: citation analysis. This is an idea from academia, where publishing in scholarly journals is a key source of validation and career advancement (hence “publish or perish”).

Programming Collective Intelligence

by

Toby Segaran

Published 17 Dec 2008

Next, you'll see how to make links from popular pages worth more in calculating rankings. The PageRank Algorithm The PageRank algorithm was invented by the founders of Google, and variations on the idea are now used by all the large search engines. This algorithm assigns every page a score that indicates how important that page is. The importance of the page is calculated from the importance of all the other pages that link to it and from the number of links each of the other pages has. Tip In theory, PageRank (named after one of its inventors, Larry Page) calculates the probability that someone randomly clicking on links will arrive at a certain page.

…

Real-Life Examples There are many sites on the Internet currently collecting data from many different people and using machine learning and statistical methods to benefit from it. Google is likely the largest effort—it not only uses web links to rank pages, but it constantly gathers information on when advertisements are clicked by different users, which allows Google to target the advertising more effectively. In Chapter 4 you'll learn about search engines and the PageRank algorithm, an important part of Google's ranking system. Other examples include web sites with recommendation systems. Sites like Amazon and Netflix use information about the things people buy or rent to determine which people or items are similar to one another, and then make recommendations based on purchase history.

…

Because the PageRank is time-consuming to calculate and stays the same no matter what the query is, you'll be creating a function that precomputes the PageRank for every URL and stores it in a table. This function will recalculate all the PageRanks every time it is run. Add this function to the crawler class: def calculatepagerank(self,iterations=20): # clear out the current PageRank tables self.con.execute('drop table if exists pagerank') self.con.execute('create table pagerank(urlid primary key,score)') # initialize every url with a PageRank of 1 self.con.execute('insert into pagerank select rowid, 1.0 from urllist') self.dbcommit( ) for i in range(iterations): print "Iteration %d" % (i) for (urlid,) in self.con.execute('select rowid from urllist'): pr=0.15 # Loop through all the pages that link to this one for (linker,) in self.con.execute( 'select distinct fromid from link where toid=%d' % urlid): # Get the PageRank of the linker linkingpr=self.con.execute( 'select score from pagerank where urlid=%d' % linker).fetchone( )[0] # Get the total number of links from the linker linkingcount=self.con.execute( 'select count(*) from link where fromid=%d' % linker).fetchone( )[0]pr+=0.85*(linkingpr/linkingcount) self.con.execute( 'update pagerank set score=%f where urlid=%d' % (pr,urlid)) self.dbcommit( ) This function initially sets the PageRank of every page to 1.0.

Artificial Unintelligence: How Computers Misunderstand the World

by

Meredith Broussard

Published 19 Apr 2018

“What’s necessary about them can be replicated, but when it comes to more sophisticated robots, they have to be male.”8 Minsky’s world view is even behind the scenes in the founding of Internet search, which most of us use every day. As PhD students at Stanford, Larry Page and Sergei Brin invented PageRank, the revolutionary search algorithm that led to the two founding Google. Larry Page is the son of Carl Victor Page Sr., an artificial intelligence professor at Michigan who would have read Minsky extensively and interacted with him at AI conferences. Larry Page’s PhD advisor at Stanford was Terry Winograd, who counts Minsky as a professional mentor. Winograd’s PhD advisor at MIT was Seymour Papert—Minsky’s longtime collaborator and business partner. A number of Google executives, like Raymond Kurzweil, are Minsky’s former graduate students.

…

Therefore, they built a search engine that would calculate how many incoming links pointed to a given web page, then they ran an equation to generate a ranking called PageRank based on the number of incoming links and the ranking of the outgoing links on a page. They reasoned that web users would act just like academics: each web user would create web pages that linked to other pages that each user considered good. A popular page, one with a large number of incoming links, was ranked higher than a page with fewer incoming links. PageRank was named after one of the grad students, Larry Page. Page and his partner, Sergei Brin, went on to commercialize their algorithm and create Google, one of the most influential companies in the world.

…

For a long time, PageRank worked beautifully. The popular web pages were the good ones—in part because there was so little content on the web that good was not a very high threshold. However, more and more people went online, content swelled, and Google began to make money based on selling advertising on web pages. The search-ranking model was taken from academic publishing; the advertising model was taken from print publishing. As people learned how to game the PageRank algorithm to elevate their position in search results, popularity became a kind of currency on the web. Google engineers had to add factors to search so that spammers wouldn’t game the system.

Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era

by

James Barrat

Published 30 Sep 2013

Much of this increased productivity is due, of course, to the Internet itself. But the vast ocean of information it holds is overwhelming without intelligent tools to extract the small fraction you need. How does Google do it? Google’s proprietary algorithm called PageRank gives every site on the entire Internet a score of 0 to 10. A score of 1 on PageRank (allegedly named after Google cofounder Larry Page, not because it ranks Web pages) means a page has twice the “quality” of a site with a PageRank of 0. A score of 2 means twice the quality as score of 1, and so on. Many variables account for “quality.” Size is important—bigger Web sites are better, and so are older ones.

…

People always make the assumption: Memepunks, “Google A.I. a Twinkle in Larry Page’s Eye,” May 26, 2006, http://memepunks.blogspot.com/2006/05/google-ai-twinkle-in-larry-pages-eye.html (accessed May 3, 2011). Even the Google camera cars: Streitfeld, David, “Google Is Faulted for Impeding U.S. Inquiry on Data Collection,” New York Times, sec. technology, April 14, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/15/technology/google-is-fined-for-impeding-us-inquiry-on-data-collection.html (accessed May 3, 2012). It doesn’t take Google glasses: In December 2012, Ray Kurzweil joined Google as Director of Engineering to work on projects involving machine learning and language processing.

…

reqstyleid=10&mode=form&rsid=&reqsrcid=ChicagoInterview&more=yes&nameCnt=1 (accessed June 10, 2010). Google’s proprietary algorithm called PageRank: Geordie, “Learn How Google Works: in Gory Detail,” PPC Blog (blog), 2011, http://ppcblog.com/how-google-works/ (accessed October 10, 2011). mankind’s primary tool: Schwartz, Evan, “The Mobile Device is Becoming Humankind’s Primary Tool,” Technology Review, November 29, 2010, http://www.technologyreview.com/news/421826/the-mobile-device-is-becoming-humankinds-primary-tool-infographics-feature/ (accessed December 4, 2011). you merely think of a question: Carr, Nicholas, “When Google Grows Up,” Forbes.com, January 11, 2008, http://www.forbes.com/2008/01/11/google-carr-computing-tech-enter-cx_ag_0111computing.html (accessed March 10, 2011).

What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of Computing

by

Ed Finn

Published 10 Mar 2017

In this way HFT algorithms replace the original structure of value in securities trading, the notion of a share owned and traded as an investment in future economic success, with a new structure of value that is based on process. Valuing Culture The arbitrage of process is central to Google’s business model; one of the world’s largest companies (now in the form of Alphabet Corporation) is built on the valuation of cultural information. The very first PageRank algorithms created by Larry Page and Sergei Brin at Stanford in 1996 marked a new era in the fundamental problem of search online. Brin and Page’s innovation was to use the inherent ontological structure of the web itself to evaluate knowledge.

…

These systems present a limited space of public governance (e.g., allowing Facebook users to promote particular causes through “liking” them), but their seemingly democratic interfaces are facades for the much deeper edifice of algorithmic arbitrage. Facebook, Google, Netflix, and the rest do not often engage in overt censorship, but rather algorithmically curate the content they wish us to see, a process media scholar Ganaele Langlois terms “the management of degrees of meaningfulness and the attribution of cultural value.”54 Like the PageRank algorithm and the many interventions Google makes to prevent its exploitation by anyone other than Google, these systems for arbitrage mix user empowerment with strict informational control to encourage particular behaviors and hide the margins and rough edges away.

…

So too, we now expect the Internet to serve as a utility that provides dependable, and perhaps fungible, kinds of information. PageRank and the complementary algorithms Google has developed since its launch in 1998 started as sophisticated finding aids for that awkward, adolescent Internet. But the company and the web’s spectacular expansion since then has turned their assumptions into rationalizing laws, just as Diderot’s framework of interlinked topics has shaped untold numbers of encyclopedias, indexes, and lists. At some point during the “search wars” of the mid-2000s, when Google cemented its dominance, an inversion point occurred where the observational system of PageRank became a deterministic force in the cultural fabric of the web.

Digital Wars: Apple, Google, Microsoft and the Battle for the Internet

by

Charles Arthur

Published 3 Mar 2012

(i), (ii), (iii) see also Microsoft Bang & Olufsen (i) Bartz, Carol (i) Basillie, Jim (i) Battelle, John (i), (ii) Bauer, John (i) BBC iPlayer (i) Bechtolsheim, Andy (i), (ii) Beckham, David and Victoria (i) BenQ (i) Berg, Achim (i) Berkowitz, Steve (i), (ii) Best Buy (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Bezos, Jeff (i) Bilton, Nick (i) BlackBerry (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix), (x), (xi) BlackBerry Messenger (i) BlackBerry Storm (i), (ii) Block, Ryan (i) Blodget, Henry (i) Bloomberg (i), (ii) BMG (i) Boeing (i) Boies, David (i), (ii) Bondcom (i) Bountii.com (i) Bowman, Douglas (i) Bracken, Mike (i) Brass, Richard (i) Brin, Sergey (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix) see also Google; Page, Larry Bronfman, Edgar (i) Brunner, Robert (i) Buffett, Warren (i) BusinessWeek (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) Bylund, Anders (i) Carr, Nick (i) Chafkin, Max (i) Chambers, Mike (i) China (i), (ii), (iii) and Apple (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) and Google (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) and Microsoft (i) mobile web browsing (i) China Mobile (i), (ii), (iii) China Unicom (i), (ii) Chou, Peter (i) CinemaNow (i) Cingular and the iPhone (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) and the ROKR (i), (ii) Cisco Systems (i) ClearType (i) Cleary, Danika (i), (ii) CNET (i), (ii), (iii) Colligan, Ed (i), (ii), (iii) Compaq (i), (ii) ComScore (i), (ii), (iii) Cook, Tim (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix), (x) Creative Strategies (i) Creative Technologies (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) Creative Labs (i), (ii) Cringely, Robert X (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Crothall, Geoffrey (i) Daisey, Mike (i), (ii) Dalai Lama (i) Danyong, Sun (i) Daring Fireball (i), (ii) Deal, Tim (i) Dean, Jeff (i) DEC (i) Dediu, Horace (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix), (x), (xi), (xii), (xiii), (xiv) ’Dediu’s Law’ (i) Dell Computer (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix), (x), (xi), (xii), (xiii) Dell DJ (i), (ii), (iii) Dell, Michael (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Design Crazy (i) Deutschman, Alan (i) Digital Equipment Corporation (i) Divine, Jamie (i) Dogfight (i), (ii) Dowd, Maureen (i) Drance, Matt (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Drummond, David (i), (ii) Dunn, Jason (i) EarthLink (i), (ii) eBay (i) Edwards, Doug (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii) Eisen, Bruce (i) Electronic Arts (i) Elop, Stephen (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) EMI (i) eMusic (i) Engadget (i), (ii) Ericsson (i) European Patent Office (i) Evangelist, Mike (i) Evans, Benedict (i) Evslin, Tom (i) Facebook (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi) Fadell, Tony (i), (ii), (iii) Fester, Dave (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) FingerWorks (i), (ii) Fiorina, Carly (i), (ii) Flash (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi) Flowers, Melvyn (i), (ii) Foley, Mary Jo (i), (ii), (iii) Forrester Research (i), (ii) Forstall, Scott (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Fortune (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) Foundem (i) Foxconn Technology (i), (ii), (iii) Fried, Ina (i) Galaxy Tab (i), (ii) Galvin, Chris (i) Gartenberg, Michael (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Gartner (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix), (x), (xi) Gates, Bill (i), (ii), (iii) SPOT watch (i) and Steve Jobs (i), (ii), (iii) see also Ballmer, Steve; Microsoft; Sculley, John Gateway (i), (ii) Gemmell, Matt (i) Ghemawat, Sanjay (i) Gibbons, Tom (i) Gilligan, Amy K (i) Gladwell, Malcolm (i), (ii), (iii) Glass, Ira (i) Glazer, Rob (i) Golvin, Charles (i), (ii) Google (i), (ii), (iii) ‘40 shades of blue’ (i), (ii) AdSense (i) and advertising (i), (ii), (iii) AdWords (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi) Android (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) 4G patent auction (i) China, manufacturing in (i), (ii) and Flash (i) and the iPhone (i), (ii) and Microsoft (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Oracle patent dispute (i) origins of (i), (ii) and standardization (i) and tablets (i), (ii), (iii) antitrust investigation (i) and AOL (i) Bigtable (i), (ii) Buzz (i) Checkout (i) Chinese market (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) google.cn (i) ’Great Firewall’ (i) hacking (i) Chrome (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) Compete (i) confrontation with Microsoft (i), (ii) data, importance of (i) Gmail (i), (ii) Goggles (i) Google Now (i) Google Play (i), (ii) Google+ (i), (ii) hiring policy (i), (ii) Instant (i) Maps (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) location data (i), (ii) users, loss of (i) vector vs raster images (i) market capitalization (i) Music All Access (i) Nest (i) and the New York terrorist attacks 2001 (i) Overture lawsuit (i) PageRank (i), (ii) and porn (i), (ii) profitability of (i) public offering (i) QuickOffice (i) and selling (i) Street View (i), (ii) and Yahoo (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) see also Brin, Sergey; Kordestani, Omid; Meyer, Marissa; Page, Larry; Schmidt, Eric; Silverstein, Craig Googled (i) GoTo.com (i), (ii), (iii) Gou, Terry (i) Grayson, Ian (i) Greene, Jay (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Griffin, Paul (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix), (x) Griffin Technology (i), (ii) Grokster (i), (ii) Gross, Bill (i), (ii) Gruber, John (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) Guardian (i), (ii), (iii) Gundotra, Vic (i), (ii) Hachamovitch, Dean (i) Handango (i) Handspring (i) Harlow, Jo (i) Hase, Koji (i), (ii), (iii) Hauser, Hermann (i) Hedlund, Marc (i) Heiner, Dave (i) Heins, Thorsten (i) Hewlett-Packard (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix), (x), (xi), (xii), (xiii), (xiv), (xv) Hitachi (i) Hockenberry, Craig (i) Hölzle, Urs (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Hotmail (i) HTC (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix) Huawei (i) Hwang, Suk-Joo (i) I’m Feeling Lucky (i) IBM (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi) IDC (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Idealab (i) i-mode (i) Inktomi (i), (ii), (iii) Instagram (i) Intel (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix) Intellectual Ventures (i) Iovine, Jimmy (i) iRiver (i), (ii), (iii) Ive, Jonathan (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix) Jackson, Thomas Penfield (i), (ii), (iii) Java (i), (ii) Jefcoate, Kevin (i) Jha, Sanjay (i) Jintao, Hu (i) Jobs, Steve (i), (ii), (iii) and Bill Gates (i), (ii) death (i) departure from Apple (i) see also Apple; Cook, Tim; Forstall, Scott; Ive, Jonathan; Schiller, Phil Johnson, Kevin (i) Johnson, Ron (i) Jones, Nick (i) Joswiak, Greg (i), (ii) Jupiter Research (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Kallasvuo, Oli-Pekka (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) Khan, Irene (i) Khan, Sabih (i) King, Brian (i), (ii) King, Shawn (i) Kingsoft (i) Kleinberg, Jonathan (i) Knook, Pieter (i), (ii) and competition from China (i) and Microsoft’s antitrust judgment (i) and Pink (i), (ii) and Steve Ballmer (i) and Windows Mobile (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) and the Xbox (i) and Zune (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) Komiyama, Hideki (i) Kordestani, Omid (i), (ii), (iii) Kornblum, Janet (i) Krellenstein, Marc (i) Laakmann, Gayle (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Lawton, Chris (i) Lazaridis, Mike (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Lees, Andy (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii) Lenovo (i), (ii) LG (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi) LimeWire (i), (ii) LinkExchange (i), (ii) Linux (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) Lodsys (i), (ii) Lotus (i), (ii) Lucovsky, Marc (i) Lynn, Matthew (i) Ma, Bryan (i) MacroSolve (i), (ii) Madrigal, Alexis (i) Mapquest (i) Mayer, Marissa (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) Media Metrix (i), (ii), (iii) MeeGo (i) Mehdi, Yusuf (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) Meisel, Ted (i) Microsoft antitrust trial (i), (ii) APIs (i) company split (i) impact of (i) and Apple QuickTime (i) Azure (i) Bing Maps (i) ’Cashback’ (i) China, manufacturing in (i) Chinese market (i) censorship (i) pirating of software (i) confrontation with Google (i), (ii) Courier (i), (ii) Danger (i), (ii), (iii) acquisition by Microsoft (i), (ii), (iii) disintegration of the team (i), (ii), (iii) digital rights management (DRM) of music (i) DirectX (i) and Facebook (i) horizontal system (i) Internet Explorer (i), (ii) Janus (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) ’Keywords’ (i) market capitalization (i) and Netscape (i), (ii) and Nokia (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) ’Pink’ (i), (ii) announcement (i) failure of (i) PlaysForSure (i), (ii), (iii) failure of (i) problems with (i), (ii), (iii) rebranding and end (i) and the Zune (i) Portable Media Center (PMC) (i) potential acquisition of Overture (i), (ii), (iii) ’roadmap’ (i) search (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) and antitrust (i) Bing (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix), (x) launch and crash (i) and Office (i) page design (i) profitability of (i) Project Underdog (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) rebranding (i) Surface tablets (i), (ii), (iii) and tablets (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Flash (i) Windows and ARM (i), (ii) WebTV (i) Windows (i), (ii) Windows Media Audio (i), (ii) Windows Media Player (i), (ii), (iii) Windows Mobile (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi) and Android (i), (ii) decline (i) peak (i) Windows Phone (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) and tablets (i) Windows RT (i) Windows Server (i), (ii), (iii) Xbox (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix) Xbox 360 (ii) Xbox Live Music Marketplace (i) Xbox Music (i) and the Zune (i) and Yahoo search (i), (ii) Zune (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) Christmas 2006 (i) demise of (i) failings of (i) market position (i), (ii) and music in the cloud (i), (ii) and the Xbox (i) Zune Music Store (i), (ii) see also Allard, J; Ballmer, Steve; Gates, Bill; Knook, Pieter; Sculley, John; Sinofsky, Steve; Spolsky, Joel Milanesi, Carolina (i), (ii), (iii) Miller, Trudy (i) Mobile World Congress (i) Morris, Doug (i), (ii) Moss, Ken (i), (ii) Mossberg, Walt (i) Motorola (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi) and Android (i) and the iPhone (i) and iTunes (i), (ii) Motorola Mobility (MMI) (i), (ii) Q phone (i) ROKR (i), (ii), (iii) Mozilla Firefox (i), (ii) Mudd, Dennis (i) Mundie, Craig (i) MusicMatch (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) MusicNet (i), (ii) Myerson, Terry (i) Myhrvold, Nathan (i) Nadella, Satya (i) Namco (i) Napster (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix), (x), (xi) Narayen, Shantanu (i) Navteq (i), (ii) Netscape (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) and Google (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) and Windows (i) (ii), (iii) New York Times (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix) New Yorker (i), (ii) NeXT Computer (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) Nintendo (i), (ii), (iii) and 4G (i) Nokia (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix), (x), (xi), (xii) Apple patent dispute (i), (ii) Communicator (i) and the iPhone (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii) Lumia (i), (ii) and Microsoft (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) N91 (i) and Navteq (i), (ii) and Steve Ballmer (i) and Symbian (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi) touchscreen development (i), (ii) Norlander, Rebecca (i) Norman, Don (i), (ii), (iii) Northern Light (i) Novell (i), (ii), (iii) NPD Group (i), (ii), (iii) O2 (i) Observer (i) Ohlweiler, Bob (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) Ojanpera, Tero (i) Open Handset Alliance (OHA) (i) Oracle (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Overture (i), (ii), (iii) acquisition by Yahoo (i) Google lawsuit (i), (ii) potential acquisition by Microsoft (i), (ii), (iii) Ozzie, Ray (i), (ii) PA Semi (i) Page, Larry (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix), (x), (xi), (xii) see also Brin, Sergey; Google Palm (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) acquisition by Hewlett-Packard (i) Pilot (i) Pre (i) profitability (i), (ii) Treo (i), (ii) Pandora (i) Partovi, Ali (i) Parvez, Shaun (i), (ii) Payne, Chris (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi) see also Microsoft PC World (i) PeopleSoft (i) Pepsi (i), (ii), (iii) Peterschmidt, David (i) Peterson, Matthew (i) ’phablets’ (i) Pixar (i), (ii), (iii) Placebase (i) PressPlay (i), (ii), (iii) Qualcomm (i) Quanta (i) Raff, Shivaun (i), (ii), (iii) Real Networks (i), (ii), (iii) Helix (i) Red Hat (i), (ii) Reindorp, Jason (i) Research In Motion (RIM) (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii) and Android (i), (ii), (iii) and Bing (i), (ii) and the iPhone (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) PlayBook (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) renaming to BlackBerry (i) Rockstar Bidco (i) writeoffs (i) see also BlackBerry Rockstar Bidco (i), (ii) Rosenberg, Scott (i) Rubin, Andy (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) and Flash (i) and Google phones (i) and Motorola Mobility (i), (ii) and touch-based devices (i) see also Google; Microsoft Rubinstein, Jon (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) Samsung (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix), (x), (xi), (xii), (xiii), (xiv), (xv), (xvi), (xvii) SanDisk (i) SAP (i) Sasse, Jonathan (i) Sasser, Cabel (i) Savander, Niklas (i) Schiller, Phil (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), and apps (i) and the iPhone (i) and iPod nano (i), (ii) and Wal-Mart (i) and 4G (i) Schmidt, Eric (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) and Android (i), (ii) and AOL (i) and Google Goggles (i) and the iPhone (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Schmitz, Rob (i) Schoeben, Rob (i) Schofield, Jack (i) Sculley, John (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi) Search (i) SEC (i), (ii) Second Coming of Steve Jobs, The (i) Sega (i) Shaw, Frank (i) Siemens (i) Sigman, Stan (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Silverstein, Craig (i) Sinofsky, Steven (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) see also ARM architecture; Microsoft Slashdot (i), (ii) Snapchat (i) Sony (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi) and digital rights management (DRM) (i) MiniDisc (i), (ii), (iii) PressPlay (i), (ii) Rockstar Bidco (i) Walkman (i), (ii), (iii) Sony Ericsson (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) SoundJam (i) Spindler, Michael (i) Spolsky, Joel (i), (ii), (iii) Spotify (i) Sprint (i) Stac Electronics (i) standards-essential patents (SEPs) (i) Starbucks (i) StatCounter (i) Stephens, Mark (i), (ii) Stringer, Howard (i) Sullivan, Danny (i) Sun Microsystems (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) Super Monkey Ball (i) Symbian (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) apps (i), (ii) and Flash (i) licencing (i) loss of market share (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Tao, Shi (i) Telefónica (i) Thompson, Rick (i) Time Warner (i), (ii) T-Mobile (i), (ii) TomTom (i) Topolsky, Joshua (i) Toshiba (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi) traffic acquisition costs (TACs) (i), (ii) Twitter (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Universal (i), (ii), (iii) US Patent Office (i) Usenet (i) Vanjoki, Anssi (i) Varian, Hal (i) Verizon (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v) Virgin Electronics (i), (ii) Visa (i) Vodafone (i), (ii), (iii) Vogelstein, Fred (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii) Wall Street Journal (i), (ii) Wal-Mart (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Wapner, Scott (i) Warner Music (i) Warren, Todd (i) Washington Post (i), (ii) Watsa, Prem (i) Waze (i) WebM (i), (ii) Wilcox, Joe (i), (ii) Wildstrom, Steve (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) Williamson, Richard (i) Windsor, Richard (i) Winfrey, Oprah (i), (ii) Wired (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi) Wojcicki, Susan (i) WordPerfect (i), (ii) Xiaomi (i) Yahoo (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii), (viii), (ix) Flickr (i) and Google (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) and GoTo (i) and Inktomi (i) and LinkExchange (i) localization (i) and Microsoft (i), (ii) and Overture (i), (ii) Tao, Shi (i) Yandex (i) Yang, Jerry (i), (ii), (iii), (iv) see also Yahoo YouTube (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (v), (vi), (vii) Zander, Ed (i), (ii) ZTE (i), (ii), (iii) Zuckerberg, Mark (i), (ii) see also Facebook Publisher’s note Every possible effort has been made to ensure that the information contained in this book is accurate at the time of going to press, and the publishers and author cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions, however caused.

…

This ebook published in 2014 by Kogan Page Limited 2nd Floor, 45 Gee Street London EC1V 3RS UK www.koganpage.com © Charles Arthur, 2012, 2014 E-ISBN 978 0 7494 7204 7 Full imprint details Contents Introduction 01 1998 Bill Gates and Microsoft Steve Jobs and Apple Bill Gates and Steve Jobs Larry Page, Sergey Brin and Google Internet search Capital thinking 02 Microsoft antitrust Steve Ballmer The antitrust trial The outcome of the trial 03 Search: Google versus Microsoft The beginnings of search Google Search and Microsoft Bust Link to money Boom Random access Google and the public consciousness Project Underdog Preparing for battle Do it yourself Going public Competition Cultural differences Microsoft’s relaunched search engine Friends Microsoft’s bid for Yahoo Google’s identity The shadow of antitrust Still underdog 04 Digital music: Apple versus Microsoft The beginning of iTunes Gizmo, Tokyo iPod design Marketing the new product Meanwhile, in Redmond: Microsoft iPods and Windows Music, stored Celebrity marketing iTunes on Windows iPod mini The growth of iTunes Music Store Apple and the mobile phone Stolen!

…

They had wanted to call it ‘Googol’ (an enormous number –10 to the hundredth power – to represent the vastness of the net, but also as a mathematical in-joke; Page and Brin love maths jokes). But that was taken. They settled on ‘Google’. Had Gates known about them, he might have worried, briefly. But there was no way Gates could have easily known about it – except by spending lots and lots of time surfing the web. The scientific paper describing how Google chose its results wasn’t formally published until the end of December 1998; a paper describing how ‘PageRank’, the system used to determine what order the search results should be delivered in – with the ‘most relevant’ (as determined by the rest of the web) first – wasn’t deposited with Stanford University’s online publishing service until 1999.15 The duo incorporated Google as a company on 4 September 1998, while they were renting space in the garage of Susan Wojcicki.

Machines of Loving Grace: The Quest for Common Ground Between Humans and Robots

by

John Markoff

Published 24 Aug 2015

In one sense the company began as the quintessential intelligence augmentation, or IA, company. The PageRank algorithm Larry Page developed to improve Internet search results essentially mined human intelligence by using the crowd-sourced accumulation of human decisions about valuable information sources. Google initially began by collecting and organizing human knowledge and then making it available to humans as part of a glorified Memex, the original global information retrieval system first proposed by Vannevar Bush in the Atlantic Monthly in 1945.11 As the company has evolved, however, it has started to push heavily toward systems that replace rather than extend humans. Google’s executives have obviously thought to some degree about the societal consequences of the systems they are creating.

…

(Wiener), 75, 211 GOFAI (Good Old-Fashioned Artificial Intelligence), 108–109, 186 “Golemic Approach, The” (Felsenstein), 212–213 “golemics,” 75, 208–215 Google Android, 43, 239, 248, 320 autonomous cars and, 35–45, 51–52, 54–59, 62–63 Chauffeur, 43 DeepMind Technologies and, 91, 337–338 Google Glass, 23, 38 Google Now, 12–13, 341 Google X Laboratory, 152–153 Human Brain Project, 153–154 influence of early AI history on, 99 Kurzweil and, 85 PageRank algorithm, 62, 92, 259 robotic advancement by, 241–244, 248–255, 256, 260–261 70-20-10 rule of, 39 Siri’s development and, 314–315 Street View cars, 39, 42–43, 54 X Lab, 38, 55–56 Gordon, Robert J., 87–89 Gou, Terry, 93, 248 Gowen, Rhia, 277–279 Granakis, Alfred, 70 Grand Challenge (DARPA), 24, 26, 27–36, 40 “Grand Traverse,” 234 Green, David A., 80 Grendel (rover), 203 Grimson, Eric, 47 Gruber, Tom, xiii–xiv, 277–279, 278, 282–297, 310–323, 339 Grudin, Jonathan, 15, 170, 193, 342 Guzzoni, Didier, 303 hacker culture, early, 110–111, 174 Hart, Peter, 101–102, 103, 128, 129 Hassan, Scott, 243, 259–260, 267, 268, 271 Hawkins, Jeff, 85, 154 Hayon, Gaby, 50 Hearsay-II, 282–283 Heartland Robotics (Rethink Robotics), 204–208 Hecht, Lee, 135, 139 Hegel, G.

…

A student in computer science first at the State University of New York at Buffalo, he then entered graduate programs in computer science at both Washington University in St. Louis and Stanford, but dropped out of both programs before receiving an advanced degree. Once he was on the West Coast, he had gotten involved with Brewster Kahle’s Internet Archive Project, which sought to save a copy of every Web page on the Internet. Larry Page and Sergey Brin had given Hassan stock for programming PageRank, and Hassan also sold E-Groups, another of his information retrieval projects, to Yahoo! for almost a half-billion dollars. By then, he was a very wealthy Silicon Valley technologist looking for interesting projects. In 2006 he backed both Ng and Salisbury and hired Salisbury’s students to join Willow Garage, a laboratory he’d already created to facilitate the next generation of robotics technology—like designing driverless cars.

The Internet Is Not the Answer

by

Andrew Keen

Published 5 Jan 2015

It’s something that has only occurred in one or two places in the whole course of human history,”77 Moritz says in describing this personal revolution engineered by data factories like Google, Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, and Yelp. It seems like a win-win for everyone, of course—one of those supposedly virtuous circles that Sergey Brin and Larry Page built into PageRank. We all get free tools and the Internet entrepreneurs get to become superrich. KPCB cofounder Tom Perkins, whose venture fund has made billions from its investments in Google, Facebook, and Twitter, would no doubt claim that the achievement of what he called Silicon Valley’s “successful one percent” is resulting in more jobs and general prosperity.

…

The end result of this gigantic math project was an algorithm they called PageRank, which determined the relevance of the Web page based on the number and quality of its incoming links. “The more prominent the status of the page that made the link, the more valuable the link was and the higher it would rise when calculating the ultimate PageRank number of the web page itself,” explains Steven Levy in In the Plex, his definitive history of Google.62 In the spirit of Norbert Wiener’s flight path predictor device, which relied on a continuous stream of information that flowed back and forth between the gun and its operator, the logic of the Google algorithm was dependent on a self-regulating system of hyperlinks flowing around the Web.

…

In vivid contrast with Amazon, Google’s profits were also astonishing. In 2012, its operational profits were just under $14 billion from revenues of $50 billion. In 2013, Google “demolished” Wall Street expectations and returned operational profits of over $15 billion from revenues of nearly $60 billion.71 Larry Page’s response to John Doerr’s question when they first met in 1999 had turned out to be a dramatic underestimation of just “how big” Google could become. And the company is still growing. By 2014, Google had joined Amazon as a winner-take-all company. It was processing around 40,000 search queries each second, which computes into 3.5 billion daily searches or 1.2 trillion annual searches.

Thinking Machines: The Inside Story of Artificial Intelligence and Our Race to Build the Future

by

Luke Dormehl

Published 10 Aug 2016

In this way, working towards achieving consciousness in a machine is a little like the way Google is perfecting their search engine. Larry Page and Sergey Brin began at Stanford with their PageRank algorithm, which remains the kernel of the Google empire. PageRank ranked pages according to the quality and number of incoming links to each page. But while PageRank remains a crucially important algorithm, Google has since enhanced it with 200 different unique signals, or what it refers to as ‘clues’, which make informed guesses about what it is that users are looking for. As Google engineers explain, ‘These signals include things like the terms on websites, the freshness of content [and] your region,’ in addition to PageRank.

…

To find a specific word or phrase from the index, please use the search feature of your ebook reader. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) 2, 228, 242–4 2045 Initiative 217 accountability issues 240–4, 246–8 Active Citizen 120–2 Adams, Douglas 249 Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) 19–20, 33 Affectiva 131 Age of Industry 6 Age of Information 6 agriculture 150–1, 183 AI Winters 27, 33 airlines, driverless 144 algebra 20 algorithms 16–17, 59, 67, 85, 87, 88, 145, 158–9, 168, 173, 175–6, 183–4, 186, 215, 226, 232, 236 evolutionary 182–3, 186–8 facial recognition 10–11, 61–3 genetic 184, 232, 237, 257 see also back-propagation AliveCor 87 AlphaGo (AI Go player) 255 Amazon 153, 154, 198, 236 Amy (AI assistant) 116 ANALOGY program 20 Analytical Engine 185 Android 59, 114, 125 animation 168–9 Antabi, Bandar 77–9 antennae 182, 183–5 Apple 6, 35, 56, 65, 90–1, 108, 110–11, 113–14, 118–19, 126–8, 131–2, 148–9, 158, 181, 236, 238–9, 242 Apple iPhone 108, 113, 181 Apple Music 158–9 Apple Watch 66, 199 architecture 186 Artificial Artificial Intelligence (AAI) 153, 157 Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) 226, 230–4, 239–40, 254 Artificial Intelligence (AI) 2 authentic 31 development problems 23–9, 32–3 Good Old-Fashioned (Symbolic) 22, 27, 29, 34, 36, 37, 39, 45, 49–52, 54, 60, 225 history of 5–34 Logical Artificial Intelligence 246–7 naming of 19 Narrow/Weak 225–6, 231 new 35–63 strong 232 artificial stupidity 234–7 ‘artisan economy’ 159–61 Asimov, Isaac 227, 245, 248 Athlone Industries 242 Atteberry, Kevan J. 112 Automated Land Vehicle in a Neural Network (ALVINN) 54–5 automation 141, 144–5, 150, 159 avatars 117, 193–4, 196–7, 201–2 Babbage, Charles 185 back-propagation 50–3, 57, 63 Bainbridge, William Sims 200–1, 202, 207 banking 88 BeClose smart sensor system 86 Bell Communications 201 big business 31, 94–6 biometrics 77–82, 199 black boxes 237–40 Bletchley Park 14–15, 227 BMW 128 body, machine analogy 15 Bostrom, Nick 235, 237–8 BP 94–95 brain 22, 38, 207–16, 219 Brain Preservation Foundation 219 Brain Research Through Advanced Innovative Neurotechnologies 215–16 brain-like algorithms 226 brain-machine interfaces 211–12 Breakout (video game) 35, 36 Brin, Sergey 6–7, 34, 220, 231 Bringsjord, Selmer 246–7 Caenorhabditis elegans 209–10, 233 calculus 20 call centres 127 Campbell, Joseph 25–6 ‘capitalisation effect’ 151 cars, self-driving 53–56, 90, 143, 149–50, 247–8 catering 62, 189–92 chatterbots 102–8, 129 Chef Watson 189–92 chemistry 30 chess 1, 26, 28, 35, 137, 138–9, 152–3, 177, 225 Cheyer, Adam 109–10 ‘Chinese Room, the’ 24–6 cities 89–91, 96 ‘clever programming’ 31 Clippy (AI assistant) 111–12 clocks, self-regulating 71–2 cognicity 68–9 Cognitive Assistant that Learns and Organises (CALO) 112 cognitive psychology 12–13 Componium 174, 176 computer logic 8, 10–11 Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) 96–7 Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI) 168, 175, 177 computers, history of 12–17 connectionists 53–6 connectomes 209–10 consciousness 220–1, 232–3, 249–51 contact lenses, smart 92 Cook, Diane 84–6 Cook, Tim 91, 179–80 Cortana (AI assistant) 114, 118–19 creativity 163–92, 228 crime 96–7 curiosity 186 Cyber-Human Systems 200 cybernetics 71–4 Dartmouth conference 1956 17–18, 19, 253 data 56–7, 199 ownership 156–7 unlabelled 57 death 193–8, 200–1, 206 Deep Blue 137, 138–9, 177 Deep Knowledge Ventures 145 Deep Learning 11–12, 56–63, 96–7, 164, 225 Deep QA 138 DeepMind 35–7, 223, 224, 245–6, 255 Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) 33, 112 Defense Department 19, 27–8 DENDRAL (expert system) 29–31 Descartes, René 249–50 Dextro 61 DiGiorgio, Rocco 234–5 Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) 31 Digital Reasoning 208–9 ‘Digital Sweatshops’ 154 Dipmeter Advisor (expert system) 31 ‘do engines’ 110, 116 Dungeons and Dragons Online (video game) 197 e-discovery firms 145 eDemocracy 120–1 education 160–2 elderly people 84–6, 88, 130–1, 160 electricity 68–9 Electronic Numeric Integrator and Calculator (ENIAC) 12, 13, 92 ELIZA programme 129–30 Elmer and Elsie (robots) 74–5 email filters 88 employment 139–50, 150–62, 163, 225, 238–9, 255 eNeighbor 86 engineering 182, 183–5 Enigma machine 14–15 Eterni.me 193–7 ethical issues 244–8 Etsy 161 Eurequa 186 Eve (robot scientist) 187–8 event-driven programming 79–81 executives 145 expert systems 29–33, 47–8, 197–8, 238 Facebook 7, 61–2, 63, 107, 153, 156, 238, 254–5 facial recognition 10–11, 61–3, 131 Federov, Nikolai Fedorovich 204–5 feedback systems 71–4 financial markets 53, 224, 236–7 Fitbit 94–95 Flickr 57 Floridi, Luciano 104–5 food industry 141 Ford 6, 230 Foxbots 149 Foxconn 148–9 fraud detection 88 functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) 211 Furbies 123–5 games theory 100 Gates, Bill 32, 231 generalisation 226 genetic algorithms 184, 232, 237, 257 geometry 20 glial cells 213 Go (game) 255 Good, Irving John 227–8 Google 6–7, 34, 58–60, 67, 90–2, 118, 126, 131, 155–7, 182, 213, 238–9 ‘Big Dog’ 255–6 and DeepMind 35, 245–6, 255 PageRank algorithm 220 Platonic objects 164, 165 Project Wing initiative 144 and self-driving cars 56, 90, 143 Google Books 180–1 Google Brain 61, 63 Google Deep Dream 163–6, 167–8, 184, 186, 257 Google Now 114–16, 125, 132 Google Photos 164 Google Translate 11 Google X (lab) 61 Government Code and Cypher School 14 Grain Marketing Adviser (expert system) 31 Grímsson, Gunnar 120–2 Grothaus, Michael 69, 93 guilds 146 Halo (video game) 114 handwriting recognition 7–8 Hank (AI assistant) 111 Hawking, Stephen 224 Hayworth, Ken 217–21 health-tracking technology 87–8, 92–5 Healthsense 86 Her (film, 2013) 122 Herd, Andy 256–7 Herron, Ron 89–90 High, Rob 190–1 Hinton, Geoff 48–9, 53, 56, 57–61, 63, 233–4 hive minds 207 holograms 217 HomeChat app 132 homes, smart 81–8, 132 Hopfield, John 46–7, 201 Hopfield Nets 46–8 Human Brain Project 215–16 Human Intelligence Tasks (HITs) 153, 154 hypotheses 187–8 IBM 7–11, 136–8, 162, 177, 189–92 ‘IF THEN’ rules 29–31 ‘If-This-Then-That’ rules 79–81 image generation 163–6, 167–8 image recognition 164 imagination 178 immortality 204–7, 217, 220–1 virtual 193–8, 201–4 inferences 97 Infinium Robotics 141 information processing 208 ‘information theory’ 16 Instagram 238 insurance 94–5 Intellicorp 33 intelligence 208 ambient 74 ‘intelligence explosion’ 228 top-down view 22, 25, 246 see also Artificial Intelligence internal combustion engine 140–1, 150–1 Internet 10, 56 disappearance 91 ‘Internet of Things’ 69, 70, 83, 249, 254 invention 174, 178, 179, 182–5, 187–9 Jawbone 78–9, 92–3, 254 Jennings, Ken 133–6, 138–9, 162, 189 Jeopardy!

…

The result was surrealistic landscapes which seemed to owe more to Salvador Dalí or H. P. Lovecraft than Google co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin. The team allowed the neural network to accentuate whatever eccentricities it discovered. Instructed to maximise the elements found in each image, Deep Dream created trippy flights of fancy. Given an image and asked to classify it and then add more detail, the neural network became trapped in strange, fascinating feedback loops. Clouds were associated with birds, and Deep Dream sought to make them ever more ‘birdlike’. A photograph of a clear sky would rapidly be filled with Google’s idealised avians, as though the world’s most powerful search engine had suddenly decided to become a graffiti artist.

Bold: How to Go Big, Create Wealth and Impact the World

by

Peter H. Diamandis

and

Steven Kotler

Published 3 Feb 2015