Pier Paolo Pasolini

description: Italian film director, poet, writer and intellectual (1922-1975)

14 results

Rome Like a Local

by

Dk Eyewitness

g Local Bars g Contents Google Map BAR ROSI Map 6; Via del Pigneto 117, Pigneto; ///copiers.wanted.endings; 380 908 0195 Things have little changed at this fabled bar since it opened in 1970. The same brown cups and saucers line the counter, Italian starlets still smoulder from their picture frames, and members of the Rosi family continue to serve coffees and aperitivi with a smile. Poet and director Pier Paolo Pasolini was a regular here in his time, and it feels as if he could walk through the door at any moment. g Local Bars g Contents Google Map BAR DEL FICO Map 1; Piazza del Fico 26, Piazza Navona; ///firms.jets.replace; www.bardelfico.com Outside Bar del Fico, under the shade of an ancient fig tree (fico means fig), you’ll see nonni playing intense games of chess.

…

Savour a pizza at SANT’ALBERTO Via del Pigneto 46; www.santalbertopizzeria.com ///peanut.segments.last Carb up at this pizzeria, named after the patron saint of pizza chefs (yes, really). There’s even a choice of crunchy Roman or thick Neapolitan crusts. 3. Stop for an Aperol at NECCI DAL 1924 Via Fanfulla da Lodi 68; www.necci1924.com ///lighten.proceeds.airbag Grab a drink at this local hangout that was once a favourite of filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini. The trees decorated with fairy lights create an atmospheric scene. 4. Dance away at FANFULLA 5/A Via Fanfulla da Lodi 5a; www.fanfulla5a.it ///active.fresh.shrimps Enjoy some solid tunes at this underground club and performance space. There are often film screenings and live performances by bands, poets and DJs, too. 5.

…

Via Braccio da Montone 80; www.cosoroma.business.site ///aura.pointer.sweat Head to this laid-back spot in the early hours for a nightcap. It’s one of the best cocktail bars in town thanks to the creative drinks – Carbonara Sour, anyone? Pasolini murals ///router.retiring.prime Scenes from filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini’s debut film L’Accattone were shot in Pigneto, inspiring numerous Pasolini murals. g Contents OUTDOORS With so much history right on their doorstep, locals can’t help but make the most of the city. Days are spent chilling in piazzas, strolling ancient roads and enjoying the view.

Rome

by

Lonely Planet

Originally it was involved in the publication of sacred music, although it later developed a teaching function, and in 1839 it completely reinvented itself as an academy with wider cultural and academic goals. Today it is one of the world’s most highly respected conservatories, with its own orchestra and chorus. Pier Paolo Pasolini, Master of Controversy Poet, novelist and filmmaker, Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922−75) was one of Italy’s most important and controversial 20th century intellectuals. His works, which are complex, unsentimental and provocative, provide a scathing portrait of Italy’s post-war social transformation. Although he spent much of his adult life in Rome, he had a peripatetic childhood.

…

Pommidoro Trattoria €€ Offline map Google map ( 06 445 26 92; Piazza dei Sanniti 44; meals €50; Mon-Sat, closed Aug; Via Tiburtina, Via dei Reti) Throughout San Lorenzo’s metamorphosis from down-at-heel working-class district to down-at-heel bohemian enclave, Pommidoro has remained the same. A much-loved local institution, it’s a century-old trattoria, with high star-vaulted ceilings, a huge fireplace and outdoor conservatory seating. It was a favourite of controversial film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, and contemporary celebs stop by – from Nicole Kidman to Fabio Cappello – but it’s an unpretentious place with superb-quality traditional food, specialising in magnificent grilled meats. Said Modern Italian €€ Offline map Google map ( 06 446 92 04; Via Tiburtina 135; meals €50; Via Tiburtina, Via dei Reti) Said is one of San Lorenzo’s chicest haunts, housed in a 1920s chocolate factory.

…

One of Hollywood’s most prolific composers, Morricone (b 1928) has worked on more than 500 films, but his masterpiece remains his haunting score for Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly). A unique orchestration of trumpets, whistles, gunshots, church bells, harmonicas and electric guitars, it was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2009. The films of Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922−75) are similarly demanding. A communist Catholic homosexual, he made films that not only reflect his ideological and sexual tendencies but also offer a unique portrayal of Rome’s urban wasteland. A contemporary of both Pasolini and Fellini, Sergio Leone (1929−89) struck out in a very different direction – see the boxed text, Click here .

Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, From the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First

by

Frank Trentmann

Published 1 Dec 2015

To say that consumption is totalitarian, for example, can obviously be challenged by pointing to the very real differences between power in one of Stalin’s labour camps and that exerted by luxury brands, however seductive. More interesting is to explore how such thinking travels in the furrows ploughed by earlier thinkers. The critique of consumerism as a new fascism goes back to the 1960s, to Pier Paolo Pasolini, the Italian film director and writer, and the Marxist émigré Herbert Marcuse. Marcuse warned of the coming of a One-dimensional Man, a book that became a best-selling consumer article in its own right. While Marcuse’s pessimistic diagnosis of social control and repression may have gone out of fashion, a good deal of today’s public debate continues to take its lead from the critique of consumerism that flourished during the post-war boom.

…

In New York, some young families joined together as communes but kept their personal cleaners and private showers: the air-conditioning was always on.158 In Germany, in 1974, a researcher was surprised to find a greater number of TVs, stereos and washers and driers in communal ‘alternative’ flats than in conventional households; some flats had three cars.159 Shared use, then, did not automatically entail simple living. Perversely, it could have the opposite effect, justifying the purchase of more appliances to avoid conflict over who controlled the TV or stereo. By 1973, when the oil crisis hit, consumer culture was thus firmly entrenched. Critical voices did not disappear. Pier Paolo Pasolini, the Italian poet and filmmaker, lamented that television and cars had flattened customs and classes into the same materialist monoculture; the ‘craving to consume’ had led to a ‘new fascism’, degrading the Italian popolo far more than in Mussolini’s day – rather downplaying the way in which leisure had been manipulated under Il Duce.160 In France, Jean Baudrillard offered a new critique of consumer society as a total system of signs, in which people lived under a kind of magical spell, no longer choosing goods for their practical utility but for the images and messages they conveyed.

…

Marcuse, Onedimensional Man. 157. Rainer Langhans & Fritz Teufel, Klau mich (Frankfurt am Main, 1968). 158. Personal information. 159. Gudrun Cyprian, Sozialisation in Wohngemeinschaften: Eine empirische Untersuchung ihrer strukturellen Bedingungen (Stuttgart, 1978), 81–5; the research was conducted in 1974. 160. Pier Paolo Pasolini, Scritti corsari (Milan, 1975/2008), see esp. 9 Dec. 1973, 22–5; and 10 June 1974, 39–44, my translation. 161. Jean Baudrillard, Société de consommation (1970) (English: The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures (London, 1970/98), 27, emphasis in original, my translation. 162. Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Letter to Soviet Leaders (London, 1974), 21–4. 163.

Everything for Everyone: The Radical Tradition That Is Shaping the Next Economy

by

Nathan Schneider

Published 10 Sep 2018

The cave dwellings in Matera, Italy—the Sassi—are said to have been inhabited for nine thousand years. Staggered terraces of masonry facades line ragged cliffs that fall into canyons. After World War II, the Sassi became the country’s most notorious slum, and the government emptied residents into modern apartments on the plateau above. For decades the ancient caves lay empty. Pier Paolo Pasolini and Mel Gibson both filmed movies about Jesus there. In the 1990s, a band of cultured squatters began to move in and renovate, leading the way for a tourist industry in the otherwise sleepy city. UNESCO declared the caves a World Heritage Site; the sides of Matera’s police cars now boast “Cittá dei Sassi.”

World Travel: An Irreverent Guide

by

Anthony Bourdain

and

Laurie Woolever

Published 19 Apr 2021

PUNJAB, INDIA: Certain shots in the train transit scene of the Punjab episode of Parts Unknown were heavily influenced by The Darjeeling Limited (2007), directed by Wes Anderson. ROME, ITALY: For episodes of No Reservations, The Layover, and Parts Unknown, Tony and the crew drew on the films La Dolce Vita (1960), directed by Federico Fellini; Mamma Roma (1962), directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini; and Via Veneto (1964), directed by Giuseppe Lipartiti. SARDINIA, ITALY: Tony looked to the nonviolent, noncriminal aspects of The Godfather (1972), directed by Francis Ford Coppola, in planning the extended family scenes in this episode of No Reservations, which featured the family of his wife, Ottavia.

Stranger Than Fiction: Lives of the Twentieth-Century Novel

by

Edwin Frank

Published 19 Nov 2024

History wouldn’t come out until 1974, and when it did, Morante took the unusual step of pitching in to pay for publication, wanting to keep the price of the book affordable, and let it be known that she had made every effort to keep the language of the book accessible to all. On the cover was a grisly photograph, in what marketers call “action red,” of a dead soldier and, under the title, not as a subtitle but as a shoutline, “A scandal that has lasted a thousand years.” Pier Paolo Pasolini, a close friend of Morante’s, immediately denounced the book’s vulgarity—the way it was published, it may as well have been Gone with the Wind!—and the immense success, domestic and international, that it enjoyed could be seen to corroborate the charge of opportunism. Yet for Morante, the popular form of the book was a serious matter: History was another of the twentieth-century novel’s emergency responses, this time to the whole of the century’s history and to history itself, and she fashioned the book to be popular in the same uncompromising spirit of literary experiment with which Joyce composed Ulysses.

I You We Them

by

Dan Gretton

I was forced to imagine my mother alone in the house and willing herself to eat a bite of something, anything, a bite of peas, and finding herself unable to. With her usual frugality and optimism, she’d put both the can and the dish in the refrigerator, in case her appetite returned. And this is the film director and poet Pier Paolo Pasolini writing to his mother: Only you in all the world know what my / heart always held, before any other love.6 / So I must tell you something terrible to know: / from within your kindness my anguish grew. / You’re irreplaceable. And because you are, / the life you gave me is condemned to loneliness. / And I don’t want to be alone.

…

5 ‘For the week or so before she was hospitalized, my mother couldn’t keep any food down …’ is from ‘Meet Me In St Louis’ by Jonathan Franzen ,New Yorker, 24 December 2001. 6 ‘Only you in all the world know what my heart always held, before any other love …’ is from ‘Prayer to my Mother’ by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Chapter Nineteen: The Wood Pigeons and the Train 1 ‘They’ve taken out insurance against pity …’ from Resurrection by Leo Tolstoy. 2 The historic material on Schmitt and Allianz’s close links to Nazism from various sources, including findings from the main study on this subject, Gerald Feldman’s Die Allianz und die deutsche Versicherungswirtschaft 1933–1945 (Allianz and the German Insurance Business, 1933–1945), published in 2001. 3 The praise for Anne Frank’s diary (‘this apparently inconsequential diary by a child … embodies all the hideousness of fascism, more so than all the evidence of Nuremberg put together’) comes from the Dutch historian Jan Romein, who had read the first manuscript of the diary, before it was published.

Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire

by

Michael Hardt

and

Antonio Negri

Published 1 Jan 2004

The difference of India is much more than that. In fact, this extreme difficulty of expressing it proves to him that the difference of India is ineffable. My fellow Italians, he concludes, I cannot describe India to you. You must go there and experience its enigma yourself. All I can say is, India is India. The other writer, Pier Paolo Pasolini, titles his book The Scent of India (L’odore dell’India) and tries to explain how similar India is. He walks the crowded streets at night in Bombay, and the air is filled with odors that remind him of home: the rotting vegetables left over from the day’s market, the hot oil of a vendor cooking food on sidewalk, and the faint smell of sewage.

Florence & Tuscany

by

Lonely Planet

Top of section Tuscany on Page & Screen TUSCANY IN PRINT In the late Middle Ages, a cheeky chap named Dante Alighieri decided that he would shake up the literary establishment by writing in Italian rather than Latin. In so doing, he laid the foundations for the development of a rich literary culture that continues to nurture both local and foreign writers to this day. Local Voices Decameron on Screen » Decameron Nights (Hugo Fregonese; 1953) » Decameron (Pier Paolo Pasolini; 1971) » Virgin Territory (David Leland; 2007) Prior to the 13th century, all Italian literature was written in Latin. But all that changed with the arrival of Florentine-born Dante Alighieri (c 1265–1321) on the literary scene. One of the founders of the Dolce Stil Novo (Sweet New Style) literary movement, whose members wrote lyric poetry in the Tuscan vernacular, Dante went on to use the local language when writing the epic poem that was to become the first, and greatest, literary work published in the Italian language: La grande commedia (The Great Comedy), published around 1317 and later renamed La divina commedia (The Divine Comedy) by his fellow poet Boccaccio.

Lonely Planet Southern Italy

by

Lonely Planet

It took a direct hit during an Allied air raid on 4 August 1943 and its reconstruction was completed in 1953. Features that did survive the fire resulting from the bombing include part of a 14th-century fresco to the left of the main door and a chapel containing the tombs of the Bourbon kings from Ferdinand I to Francesco II. The church forecourt makes a cameo in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s film Il Decameron (The Decameron), itself based on Giovanni Boccaccio’s 14th-century novel. oCappella SanseveroCHAPEL (map Google map; %081 551 84 70; www.museosansevero.it; Via Francesco de Sanctis 19; adult/reduced €7/5; h9am-7pm Wed-Mon; mDante) It’s in this Masonic-inspired baroque chapel that you’ll find Giuseppe Sanmartino’s incredible sculpture, Cristo velato (Veiled Christ), its marble veil so realistic that it’s tempting to try to lift it and view Christ underneath.

Italy

by

Damien Simonis

Published 31 Jul 2010

Click here for reviews. Il Postino (1994) Director: Michael Radford La Dolce Vita (1960) Director: Federico Fellini Ladri di Biciclette (1948) Director: Vittorio de Sica La Vita è Bella (1997) Director: Roberto Benigni Roma Città Aperta (1945) Director: Roberto Rossellini Mamma Roma (1962) Director: Pier Paolo Pasolini Nuovo Cinema Paradiso (1988) Director: Giuseppe Tornatore Pane e Tulipani (2000) Director: Silvio Sordini Caro Diario (1994) Director: Nanni Moretti Il Divo (2008) Director: Paolo Sorrentino TOP READS Before the advent of cinema, writers conveyed the sights, feelings and sensibilities of Italians and their world in print.

…

If sonnets seem flowery to you, try 1975 Nobel laureate Eugenio Montale, who wrings poetry out of the creeping damp of everyday life, or Ungaretti, whose WWI poems hit home with a few searing syllables. His two-word poem seems an apt epitaph: M’illumino d’immenso (I illuminate myself with immensity). Poems by Pier Paolo Pasolini feature the same antiheroes as his films (Click here) — hustlers and prostitutes in postwar Italy, icons of a nation scraping by on its wits and looks. For the bawdiest poetry of all, head to an Italian osteria, where by night’s end cheap wine may inspire raunchy rhymes sung in dialect. Music Italy is known for achievements in opera and classical music, but it’s also adapted international pop, punk and hip hop to local tastes.

…

* * * ITALIAN CINEMA Nitty-Gritty Neorealism Unflinching tales of postwar woe shot in gorgeous yet gritty black and white make Citizen Kane seem like a rough cut, and Francois Truffaut like a latecomer. Ladri di biciclette (The Bicycle Thief), Vittorio de Sica, 1948. A special Oscar was awarded to this film about one father’s doomed attempts to provide for his son without resorting to crime in war-ravaged Rome. Mamma Roma, Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1962. Anna Magnani becomes an allegory for postwar Italy as an aging prostitute trying to make an honest living for herself and her delinquent son. Roma, città aperta (Rome, Open City), Roberto Rossellini, 1945. A story of love, betrayal, survival and resistance in Nazi-occupied Rome, shot and released while the memory of occupation was still raw.

The Eternal City: A History of Rome

by

Ferdinand Addis

Published 6 Nov 2018

Much more than La Strada, it deals with the hard reality of Italian life. The film reveals a Rome blighted by poverty, a city whose famous urban centre was ringed by a desolate periphery of modern slums, whose proud monuments were the night-time haunts of thieves, pimps and prostitutes. Fellini’s guide to this Roman underworld was a writer named Pier Paolo Pasolini, later one of the great figures of Italian cinema in his own right. Pasolini was a man of somewhat scandalous reputation – he had been expelled from the Communist Party following a scandal involving three teenage boys – but he was an acute and passionate observer of Roman street life. He saw, with a poet’s eyes, the beauty and desperation of the Roman poor: a young chestnut seller from Trastevere, dark skinned, hunched over his stove; boys swimming in the Tiber; a hustler selling rotten dogfish from a market stall by Monte Testaccio.

Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can't Explain the Modern World

by

Deirdre N. McCloskey

Published 15 Nov 2011

Surely the Dutch of the Golden Age didn’t actually carry out their painted and poemed project of the virtues? Surely the bourgeois then as now were mere hypocrites, the comically middle-class fools or villains in a Molière play; or, worse, in a Balzac novel; or, worse still, in a late-Dickens novel; or, worst of all, in a Pier Paolo Pasolini or Paolo Virzi film, n’est-ce pas? No, it appears not. Ce n’est pas vrai. Not in Holland, nor in some other places. As a referee of the present volume put it, “being wickedly good at commerce needn’t render people wicked.” Trading did not corrupt, for example, the charity of trade-saturated Holland.

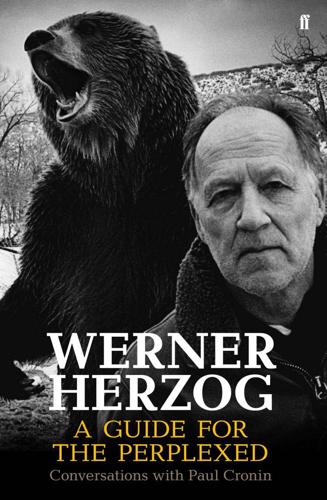

Werner Herzog - a Guide for the Perplexed: Conversations With Paul Cronin

by

Paul Cronin

Published 4 Aug 2014