Plato's cave

description: a philosophical allegory by Plato describing people who perceive only the shadows of reality, used to explore themes of knowledge, reality, and perception.

75 results

The Greatest Story Ever Told--So Far

by

Lawrence M. Krauss

Published 21 Mar 2017

Second, he could argue that as the length oscillates, the maximum length of the shadow when the arrow is pointing in one direction will always be exactly the same as the maximum length of the shadow when it is pointing in the other direction. Plato’s cave thus becomes an allegory for far more than he may have intended. Plato’s freed man discovers the hallmarks of the remarkable true story of our own struggle to understand nature on its most fundamental scales of space, time, and matter. We too have had to escape the shackles of our prior experience to uncover profound and beautiful simplifications and predictions that can be as terrifying as they are wonderful. But just as the light beyond Plato’s cave is painful to the eyes at first, with time it becomes mesmerizing.

…

In some sense, Plato’s cave prepared our minds for Einstein’s relativity, though it remained for Einstein’s former mathematics professor Hermann Minkowski to complete the task. Minkowski was a brilliant mathematician, eventually holding a chair at the University of Göttingen. But in Zurich, where he was one of Einstein’s professors, he was a brilliant mathematician whose classes Einstein skipped, because while he was a student, Einstein appeared to have a great disdain for the significance of pure mathematics. Time would change that view. Recall that the prisoners in Plato’s cave also saw from shadows on their wall that length apparently had no objective constancy.

…

I., 132, 148 radiation cosmic microwave background (CMB), 290, 292–93 Dirac’s research on, 98, 114 Einstein’s research on, 81, 89 Planck’s research on, 78–81, 89, 115 radioactivity artificial, 119, 128 Fermi’s research on, 125, 128 human bodies with, 113, 120 types of rays in, 119–20 in uranium, 119 relativity antiparticles and, 97, 100, 102 clocks relative to moving objects (time dilation) research on, 58–61 Dirac’s research on quantum mechanics and, 92, 95, 151 impact of Einstein’s discovery of, 95 Minkowski’s four-dimensional “space-time” theory and, 66–68, 71 Plato’s cave allegory and, 65–66 ruler measurement example of, 65–67 religion compatibility between science and, 21, 22 early pioneers in science and belief in, 21–22, 43 Galileo’s belief about Earth and rest and, 45, 46–47 longing as ultimate motive for exploration in, 6 role of light in, 19–20 renormalization, 105–6 Republic (Plato), 11. See also Allegory of the Cave Riess, Adam, 295 Roosevelt, Franklin D., Einstein’s letter to, 129 Ross, Graham, 204 Royal Institution, 25, 26, 36 Royal Society, 23, 24, 25, 35, 118 Rubbia, Carlo, 251, 252–54, 262, 270 Rutherford, Ernest, 114, 116, 118, 119–20 S “sacred,” concept of the, 2, 14–15 Sakurai, J.

Early Retirement Extreme

by

Jacob Lund Fisker

Published 30 Sep 2010

Sure, they could explain how I should first purchase a "starter home," so I could "upgrade" later. But nobody could or would explain why I should buy a house in the first place. Nobody could or would explain why I should have a career, only that career development was important. There are a few allegories that explain this progression in thinking. The oldest is Plato's Cave.4 In Plato's Cave prisoners have been arranged in a row in a dark cave since childhood. They're chained so that they can't move their bodies, and their heads are restrained too so they can only face forward, towards a wall. They can hear and speak but they can't see each other, nor can they see themselves.

…

A wage slave is a person who is not only economically bound by mortgages, loans, and other obligations, but also mentally bound by an inability to perceive that there are other options available, like the prisoners in Plato's Cave. Their chains are not physical like those of 150 years ago (though they still are in some parts of the world); the chains are mental, which in some sense makes them worse, because it turns the prisoners into their own prison wardens. Like the slaves in Plato's Cave, the only commonly accepted way for one of them to leave is to win the "prison game," which means accumulating at least a million to retire.5 The disenchanted grumble about "the system" or "the man."

…

Having a job so that the bills get paid and one can go back home every night and pass out in front of the TV is what the good life is all about, right? Most people would agree, because most people can't imagine any alternatives. They are, in other words, prisoners chained to the floor in Plato's Cave. To break away mentally, one needs to be conscious of the fact that one is chained to the floor in Plato's Cave. The best way to understand this is to see the cave--that is, your current perspective--from a different perspective--namely, looking into the cave from the outside. Here is what I see. Education and training Children naturally try to emulate their parents, at least in the early years, and for the most part a child's values are a direct reflection of his parents', either conformingly aligned or diametrically opposed.

The Simulation Hypothesis

by

Rizwan Virk

Published 31 Mar 2019

The reality of the world around us is something that philosophers have debated for some time. Thousands of years ago in The Republic, Plato described his analogy of the cave. In this cave, the residents are chained to a wall so they can’t see the world outside; the best they can perceive are shadows of the real world, reflected on the wall of the cave by some light outside. The residents of the cave construct an elaborate idea about what reality is, and Plato surmised that we are like the residents of this cave, seeing only shadows of the real world. Many of the world’s religious traditions tell us that the world around us is an illusion created for our benefit.

…

Finally, we’ll end with a discussion of how the simulation hypothesis may provide the first plausible bridge between two of the most important searches for truth in humanity’s history: those of the scientific community and the mystics who are responsible for the world’s religions. First, before we wrap up on these bigger notes, let’s look at one of the oldest recorded references to the simulation hypothesis in the Western philosophical tradition. Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and the Simulation Hypothesis In his classic work, The Republic, Plato recites the allegory of a den or cave where prisoners are chained to an inside wall with a clear view of a blank wall that is just opposite the entrance. As forms move in front of the cave, the prisoners can see the reflections of those forms on the wall as shadows in front of some source of light.

…

Some Unexplained Areas: God, Angels, NDEs, and UFOs 218 God and The Creation of the Physical World God and the Afterlife Angels AI: Gods and Angels and the Simulation Hypothesis Near-Death Experiences UFOs The Fermi Paradox Jung and Synchronicity OBEs, Remote Viewing, Telepathy and Other “Unexplained” Phenomenon Part IV: Putting it All Together 245 Skeptics and Believers: Evidence of Computation 246 The Categories of Arguments/Experiments A Quick Note About Metaphysical Experiments and Consciousness The Skeptics: The Resource Argument Evidence of Conditional Rendering Experiments for Evidence of Pixels Evidence of Computation: Error-Correcting Codes Quantum Computers, Error Codes, and Quantum Entanglement Quantum Entanglement and Simulation Fractals and Evidence of Computation in Nature Simple Programs and A New Kind of Science Conclusion—the Search for Evidence of Computation The Great Simulation and Its Implications 269 Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and the Simulation Hypothesis What is the Great Simulation and Who Runs It? What Are the Main Elements of the Great Simulation? Conscious Beings or Unconscious Simulations—PCs vs. NPCs The Big Picture: Computation Underlies the Other Sciences Parting Thoughts: Bridging the Great Divide Acknowledgements 292 Index 293 About the Author 308 Part 0 Overview Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one.

Humankind: Solidarity With Non-Human People

by

Timothy Morton

Published 14 Oct 2017

What’s fascinating is that the film opens up a literal passageway from one kind of space to the other, from the realm of engineering to the realm of dreamtime. The wormhole and its filmic cousins (Murph’s room, the tesseract within the black hole and its seemingly inviolable fourth walls, its cinema-screen-like separation of past and present) are the reverse of Plato’s cave, another form of cinema. Plato’s character can’t wait to get out of the cave to see the truth. In Interstellar, the truth lies within the cinema cave, the image for which keeps amplifying and amplifying as the film proceeds. The ship Endurance is one kind of cave. The wormhole is the pivotal instance: it floats in space like a gigantic crystal ball, as if we were able to see a dreaming mind, a mind full of other stars and planets.

…

Claiming that “Marx Already Thought That” means that ecological politics and ethics amount to “saving the Earth,” which means “saving the world,” which means “preserving a reasonably human-friendly environment.” This isn’t solidarity, this is infrastructural maintenance. What is preserved is the cinema in which human desire projection can play on the blank screen of everything else. The cinema is surely a contemporary version of Plato’s cave. The implicit warm, dark, tactile intimacy of such a cave is overlooked if all we want to do is preserve the quality of the shadow play on the walls. And we seem very certain about that shadow play. It has precisely lost a whole dimension of its playful quality, becoming in-flight entertainment, a high-fidelity screen with no flickering, on which we see what we know and know what we see.

The Friendly Orange Glow: The Untold Story of the PLATO System and the Dawn of Cyberculture

by

Brian Dear

Published 14 Jun 2017

Bitzer had named this system PLATO, and his crowning achievement, the PLATO IV terminal with its gas plasma flat panel touch-sensitive graphical display, supporting internal mirrors and microfiche color slide projection, was indeed a cave of sorts, not unlike the cave in Plato’s allegory. And like Plato’s cave, this “cave” was one whose denizens preferred the depictions on its “wall,” rather than the Technicolor reality going on outdoors. Not only that, but PLATO could be something you belonged to. Something you experienced with others, side by side or virtually through cyberspace. It was something you did, but it was also a place you could hang out in.

…

It was something you did, but it was also a place you could hang out in. Its more obsessed users viewed the actuality of the PLATO experience as dwarfing what one experiences in real life: more interactions, a sense of hyper-accelerated self, poring through content faster than possible in the real world. Like Plato’s cave, the “drawings” on the wall were crude, shadows only, but still PLATO users were undeterred. For instance, pornography. Another inevitable consequence of bringing a lot of people, particularly young people, together into a virtual space online and then providing a variety of open-ended tools at their disposal to be as creative as possible, is the inevitable arrival of pornography.

…

IEEE History Center (New Brunswick, NJ) Oral History Interview by Janet Abbate. Golub, Gene. 1979-06-08. CBI-UM Oral History Interview OH 105 by Pamela McCorduck. Johnson, Roger. 2002-11-29. Interview by James Hutchinson, UIUC ECE. Unpublished. Jones, Steve, and Guillaume Latzko-Toth. 2017. “Out from the PLATO Cave: Uncovering the Pre-Internet History of Social Computing.” Internet Histories 1, nos. 1-2 (2017). Retrieved 2017-05-17 from https://protect-us.mimecast.com/s/mmYrB6c7KDzwhY?domain=tandfonline.com Kay, Alan. 2016-06-21. “Alan Kay Has Agreed to Do an AMA Today.” Hacker News. Retrieved 2016-06-21 from https://news.ycombinator.com/item?

Time of the Magicians: Wittgenstein, Benjamin, Cassirer, Heidegger, and the Decade That Reinvented Philosophy

by

Wolfram Eilenberger

Published 14 Sep 2020

Moore, regarded as one of the most brilliant thinkers and logicians of his time, who, according to Wittgenstein, “shows you how far a man can go who has absolutely no intelligence whatsoever.” How was he to explain the ladder of nonsense thoughts that one had first to climb and then push away in order to see the world as it really is? Hadn’t the wise man from Plato’s cave, once he had reached the light, failed to make his insights comprehensible to the others still trapped deep inside? Enough for today. Enough explanations. Wittgenstein stands up, walks around the table, claps Moore and Russell cordially on the shoulder, and utters the sentence that all aspiring doctors of philosophy must dream about the night before their oral exams: “Don’t worry, I know you’ll never understand it.”

…

Setting our clinical suspicions aside, the notion that his access to the so-called world outside, and to all the others “out there,” was at a fundamental level disturbed or distorted effectively sums up the founding doubt of Western philosophy: Is there something that separates us from the true nature of things? The actual experiences and sensations of others? And if so, who or what could it be? Plato’s parable of the cave already relies on the assumption that the world as we perceive it is in fact one of only shadow and appearance. About two thousand years later, in the actual founding document of modern epistemological and subjective philosophy, René Descartes’s Meditations, written in 1641, we can see an analogy that gives concrete form to Wittgenstein’s simile of the person behind the “closed window.”

…

Because even if the author of the article in the Paris guide that Benjamin cites did not see it, and in all likelihood did not deliberately intend it, it reflects the whole history of metaphysics. It is expounded in what we might call magazine-speak, and is granted a weird afterlife as if by a ghostly hand: just like the shadow plays in Plato’s cave, the displays of commodities in the deep mirrored passageways of the arcades receive “their light from above,” in the form of artificial fire (gaslight). As in Leibniz’s Monadology, even the windowless arcades appear as “a world in miniature.” And as Kant (and of course Marx) would have it, all that maintains these passages through whole buildings—which are themselves only superficially buildings—is the “speculative” will of their owners, “united” for this apparent purpose, if not for anything else.

Life Is Simple: How Occam's Razor Set Science Free and Shapes the Universe

by

Johnjoe McFadden

Published 27 Sep 2021

Plato believed that the Forms or universals are the true reality that exists in an invisible but perfect realm beyond our senses. His system is often known as philosophical realism to denote that Plato, and his followers, believed that Forms or universals are not only real but are the ultimate reality that give rise to our sensory perceptions.vi Plato graphically illustrated his model in his famous Allegory of the Cave in which he compared the human experience to that of people chained facing the wall of a cave lit by a fire. Real objects (analogous to his Forms) pass between them and the fire but the inhabitants of the cave can only perceive their own shadows projected onto the cave wall.

…

He urged his followers to ignore the distorted lens of their senses and instead use their intellect to discover the ‘circular motions, uniform [speed across the sky] and perfectly regular, [that] are to be admitted as hypotheses so that it might be possible to save the appearance presented by the planets’.8 Thus, saving the appearance of the planets, as this quest came to be called, became the primary mission of astronomers for more than two thousand years. The first to take up the challenge of saving the appearance of the heavens was Plato’s pupil, Eudoxus of Cnidus (410–347 BCE) who, in a pattern that will become familiar, added more spheres. Imagine you are standing in Plato’s cave, which lies at the centre of a simplified version of Eudoxus’s model consisting of just a single sphere, which we will represent in Figure 5 as a band-like section of the crystal sphere (though remembering that Eudoxus imagined an entire sphere). Attached somewhere on the inside of the band’s circumference is a bright light, which we will call the ‘Planet’.

…

The addition of the wheel now accounted for the waxing and waning of the planets but how can any kind of wheel swing a planet through a supposedly rock-solid crystal sphere? Ptolemy did not attempt to explain. Even with all this complexity, the motions of the planets did not entirely fit Ptolemy’s model. To fix the problem, he introduced two additional complications. First, he shifted the earth (Plato’s cave in the figure) from the precise centre of the sphere’s rotations to a point, just off-centre, which was called the eccentric. He also quietly dropped the Platonic principle of uniform motion by allowing each planet only to appear to rotate at uniform speed from an imaginary point in space termed the equant.

Fuller Memorandum

by

Stross, Charles

Published 14 Jan 2010

Note that this does not involve potions, pentacles, prayers, eldritch chanting, dressing up in robes and pointy hats, or most (but not all) of the stuff associated with the term in the public mind. No, our magic is computational. The realm of pure mathematics is very real indeed, and the . . . things . . . that cast shadows on the walls of Plato's cave can sometimes be made to listen and pay attention if you point a loaded theorem at them. This is, however, a very dangerous process, because most of the shadow-casters are unclear on the distinction between pay attention and free buffet lunch here. My job--applied computational demonologist--comes with a very generous pension scheme, because most of us don't survive to claim it.

Our Moon: How Earth's Celestial Companion Transformed the Planet, Guided Evolution, and Made Us Who We Are

by

Rebecca Boyle

Published 16 Jan 2024

They had laboratory tables for dissecting animals and large lecture halls where students could hear Aristotle hold court. His successors carried the ideals of the Lyceum into the future and ensured they would reach all the way to the Enlightenment. The American historian Arthur Herman, in his Plato-vs.-Aristotle biography The Cave and the Light, notes that Aristotle saw his philosophy, including his Moon-centric cosmology, as a complete picture of reality. It encapsulated everything. But “by stressing the power of observation as the main source of knowledge, he had let the genie run free,” Herman writes. Others would carry this scientific method forward, make their own observations, and ultimately surpass Aristotle’s neatly packaged cosmos.

…

With the help of a new, unquestioning Christian philosophy, Ptolemy’s Earth-centered cosmos calcified, and for the most part, scholars left it at that. We can thank Saint Augustine of Hippo, in part, for the hold Ptolemy’s idea had over the Western conception of the world order. In the early fifth century C.E., Saint Augustine (354–430) looked inside Plato’s cave and developed a new Christian philosophy. Plato had preferred the playground of thought over actual experiment because he believed our senses and our experiences deceive us of the truth—they are merely the shadows of reality. Augustine’s Neoplatonic Christian philosophy likewise held that facts were merely illustrative of truth, not starting points for experiments that would lead to new questions.

The Right Side of History

by

Ben Shapiro

Published 11 Feb 2019

But the heroes of Greek legend are those who challenge the fates, seeking to glorify their own independence: Prometheus, Antigone, Achilles . . . even Socrates himself. As famed drama critic Walter Kerr puts it, “Tragedy speaks always of freedom.”6 This tragic quest for knowledge is endemic to Greek thought. It is a tragedy shot through with hope. Plato’s allegory of the cave is the most famous example of striving to reach the light. In that allegory, Plato paints a picture of men chained to a wall in a cave, prevented from seeing the source of light outside the cave; their ignorance restricts them to the belief that “the truth is nothing other than the shadows of artificial things.”

…

Jesus’s story was meant to extend to the entire world. Because Jesus was no longer a Jewish figure in the Christian view, but the material incarnation of the divine, that meant that Jewish law could be abandoned in favor of universalism. As historian Richard Tarnas writes, “That supreme Light, the true source of reality shining forth outside Plato’s cave of shadows, was now recognized as the light of Christ. As Clement of Alexandria announced, ‘By the Logos, the whole world is now become Athens and Greece.’”3 The Judaic notion of God, so focused on law and the Jewish people as God’s torch burning in the darkness through fulfillment of that law, was turned aside.

The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age

by

Tim Wu

Published 14 Jun 2018

The man who described the mood was author John Perry Barlow, who in the 1990s implored those interested in cyberspace to “imagine a place where trespassers leave no footprints, where goods can be stolen an infinite number of times and yet remain in the possession of their original owners, where businesses you never heard of can own the history of your personal affairs, where only children feel completely at home, where the physics is that of thought rather than things, and where everyone is as virtual as the shadows in Plato’s cave.” Everything was fast and chaotic; no position was lasting. One day, AOL was dominant and all-powerful; the next, it was the subject of business books laughing at its many failures. Netscape rose and fell like a rocket that failed to achieve orbit (though Microsoft had something to do with that).

Dawn of the New Everything: Encounters With Reality and Virtual Reality

by

Jaron Lanier

Published 21 Nov 2017

People will spend centuries on the problem, mark my words.16 The established way we cope with very large numbers of concrete possibilities is through abstraction. The open question is whether there’s a more fluid form of concrete expression that can become a practical alternative to abstraction. It’s only imaginable in user interfaces beyond what we know, probably in future versions of VR. Rubble Fills Plato’s Cave Computer science can be thought of as a branch of engineering, or an art, a craft, or even a science. It’s all these things, but mostly, to me, it’s applied philosophy, or better yet, experimental philosophy. Computer scientists have ideas about the meaning of life, and the practices that make life good, and implement those as patterns that will guide the real lives of real people.

…

Poïesis Fascination Versus Suicide Rue Goo Appendix Two: PHENOTROPIC FEVERS (ABOUT VR SOFTWARE) Mandatory Metamorphosis Grace Picture This Sleight Editor and Mapping Variation Phenotropic Trial Run Scale Motivation Role Reversal Expression The Wisdom of Imperfection Resilience Adapt Swing Rubble Fills Plato’s Cave Many Caves, Many Shadows, but Only Your Eyes Appendix Three: DUELING DEMIGODS Not Artificial, but Imaginary The Banality of Weightlessness The Invisible Hand on a Multitouch Screen The Absurdity of Demanding That AI Fix Itself The Humane Use of Human Systems NOTES INDEX ALSO BY JARON LANIER ABOUT THE AUTHOR ILLUSTRATION ACKNOWLEDGMENTS COPYRIGHT Illustration Acknowledgments All images in this book are courtesy of the author with the exception of the following: Photographs by Kevin Kelly, used with permission

Likewar: The Weaponization of Social Media

by

Peter Warren Singer

and

Emerson T. Brooking

Published 15 Mar 2018

He sees real light for the first time, finally understanding the nature of his reality. Yet the prisoners inside the cave refuse to believe him. They are thus prisoners not just of their chains but also of their beliefs. They hold fast to the manufactured reality instead of opening up to the truth. Indeed, it is notable that the ancient lessons of Plato’s cave are a core theme of one of the foundational movies of the internet age, The Matrix. In this modern reworking, it is computers that hide the true state of the world from humanity, with the internet allowing mass-scale manipulation and oppression. The Matrix came out in 1999, however, before social media had changed the web into its new form.

…

The Matrix came out in 1999, however, before social media had changed the web into its new form. Perhaps, then, the new matrix that binds and fools us today isn’t some machine-generated simulation plugged into our brains. It is just the way we view the world, filtered through the cracked mirror of social media. But there may be something more. One of the underlying themes of Plato’s cave is that power turns on perception and choice. It shows that if people are unwilling to contemplate the world around them in its actuality, they can be easily manipulated. Yet they have only themselves to blame. They, rather than the “ruler,” possess the real power—the power to decide what to believe and what to tell others.

…

abstract_id=3048994. 271 approached the task “laterally”: Ibid. 271 “a maze”: Carrie Spector, “Stanford Scholars Observe ‘Experts’ to See How They Evaluate the Credibility of Information Online,” Stanford News Service, Stanford University, October 24, 2017, https://news.stanford.edu/press-releases/2017/10/24/fact-checkers-ouline-information/. 271 “seeking context and perspective”: Ibid. 271 Reality is one: Paul J. Griffiths, An Apology for Apologetics: A Study in the Logic of Interreligious Dialogue (Wipf and Stock, 2007), 46. 272 most important insights: Plato, “The Allegory of the Cave,” Republic, 7.514a2–517a7, trans. Thomas Sheehan, https://web.stanford.edu/class/ihum40/cave.pdf. 273 “believe whatever you want”: The Matrix, directed by the Wachowski Brothers (Warner Bros., 1999). Index A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z A Abbottabad, Pakistan, 53–55 Abdallat, Lara, 213 account suspensions, 92, 235, 236, 242 Active Measures Working Group, 263 Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), 26–27 Advocates for Peace and Urban Unity, 14 Ahmadinejad, Mahmoud, 60 AIDS disinformation campaign, 104, 208 Airbnb, 239 Al Qaeda, 54, 65, 79–80, 149, 234 Alabed, Bana, 214–16 al-Assad, Bashar, 9, 72, 88, 215 al-Awlaki, Anwar, 234 Albright, Jonathan, 113 Alefantis, James, 128 Algeria, 88–89 algorithms, 124, 139, 141, 147, 209, 221, 251 Ali, Muhammad, 254 al-Jabari, Ahmed, 193 Allen, George, 55–57, 58 #AllEyesOnISIS, 5–7, 10 Al-Shabaab, 235 alternative (alt-)right, 133–34, 170, 188–89, 232, 237–39 Al-Werfalli, Mahmoud, 76 Al-Zomor, Aboud, 151 Amazon, 41 America Online, 218–19, 244–45 American Civil War, 30–31 Android, 48 anger, 162–63, 165 Anonymous (hacktivist group), 212–13 anti-Semitism, 146, 190, 198, 238 anti-vaxxers, 124–25 “Anyone Can Become a Troll” (report), 165 Apple, 47–51 Apprentice, The (TV show), 2 apps, 47–48, 58, 101, 200 Arab Spring, 85–87, 126, 183 Arendt, Hannah, 170 Argus Panoptes, 57 arms dealers, 76–77 Armstrong, Matt, 108 Aro, Jessikka, 114 ARPANET, 27, 35–42 historical background, 27–35 Arquilla, John, 182–83 arrests, 91, 92, 100, 200 artificial intelligence, 250, 255–56 Aristotle, 168 Ashley Madison (social network), 59 Asif, Khawaja, 135 astroturfing, 142 AT&T, 26, 31, 37–38 “@” symbol, 36 Athar, Sohaib, 53–55 attacks, on others.

Fool's Gold: How the Bold Dream of a Small Tribe at J.P. Morgan Was Corrupted by Wall Street Greed and Unleashed a Catastrophe

by

Gillian Tett

Published 11 May 2009

A “silo” mentality has come to rule inside banks, leaving different departments competing for resources, with shockingly little wider vision or oversight. The regulators who were supposed to oversee the banks have mirrored that silo pattern, too, in their own fragmented practices. Most pernicious of all, financiers have come to regard banking as a silo in its own right, detached from the rest of society. They have become like the inhabitants of Plato’s cave, who could see shadows of outside reality flickering on the walls but rarely encountered that reality themselves. The chain that linked a synthetic CDO of ABS, say, with a “real” person was so convoluted, it was almost impossible for anybody to fit it into a single cognitive map—be they anthropologist, economist, or credit whiz.

You Are Now Less Dumb: How to Conquer Mob Mentality, How to Buy Happiness, and All the Other Ways to Outsmart Yourself

by

David McRaney

Published 29 Jul 2013

Despite his fame, the late 1800s wasn’t a good time to be in need of mental or physical care. Medical school was mostly about anatomy, physiology, and the classics. You drew the insides of things and wondered what they did. You learned where the heart was, how to amputate a leg, and what Plato had to say about his cave. Pretty much everything useful that doctors know today was yet to be discovered or understood. Sore throat? No problem. Tie some peppered bacon around your neck. Hernia? Lie down so you can anally absorb a little tobacco smoke. The Wild West of science and medicine was only just becoming tamed, so in many places there was still debate over things such as washing your hands after dealing with a fetid corpse before inserting them still sticky into the body of a woman giving birth.

…

I think he is, but when he took me and my wife to a philosophy conference, he ended up leaving early so we could go to a juke joint in Columbus, Mississippi, to hear real blues. Bishop taught the first philosophy class I ever took, and like most people where I grew up, there was nothing like that in high school. It was the first time I heard of Plato’s Cave and the death of Socrates. It was definitely the first time I heard someone ask a group of people if free will was real or just wishful thinking. Every class with Bishop ended up with a dozen people shaking their heads and challenging the professor, and he stood up there with his silver bowl cut and cherubic grin just soaking in the ignorance.

Is God a Mathematician?

by

Mario Livio

Published 6 Jan 2009

In fact, to the Pythagoreans, God was not a mathematician—mathematics was God! The importance of the Pythagorean philosophy lies not only in its actual, intrinsic value. By setting the stage, and to some extent the agenda, for the next generation of philosophers—Plato in particular—the Pythagoreans established a commanding position in Western thought. Into Plato’s Cave The famous British mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947) remarked once that “the safest generalization that can be made about the history of western philosophy is that it is all a series of footnotes to Plato.” Indeed, Plato (ca. 428–347 BC) was the first to have brought together topics ranging from mathematics, science, and language to religion, ethics, and art and to have treated them in a unified manner that essentially defined philosophy as a discipline.

Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires

by

Douglas Rushkoff

Published 7 Sep 2022

Once a member of the New York Socialist Party, Lippmann was concerned that people are more apt to believe and react to “the pictures in their heads ” than whatever is really happening in the world outside. Journalism and other media inserts what Lippmann called “a pseudo-environment” between us and the environment in which we are actually living. This pseudo-environment, in turn, stimulates us to act in ways that really do change the world. Like the people in the allegory of Plato’s cave, we’re responding to what amounts to shadows on the wall, and this makes us particularly vulnerable to dangerous despots and demagogues who can create the most compelling pictures. Where the people reforming today’s social media platforms may hope to mitigate the influence of alt-right extremists and conspiracy theorists on our beliefs and behavior, Lippmann and Wilson were concerned about early-twentieth-century nationalists who sought to keep America isolated and turned inward.

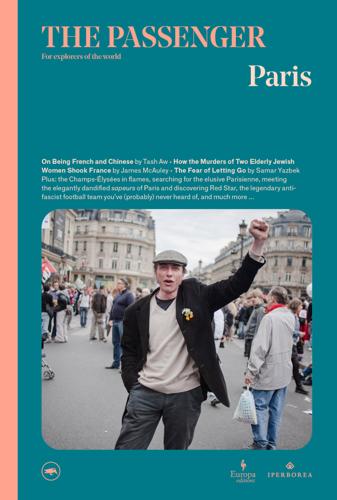

The Passenger: Paris

by

AA.VV.

Published 26 Jun 2021

But the bouquet of a city’s metro will probably be the same. Whenever we find ourselves in a new town for the first time we often take the same approach to sightseeing, maybe by taking photos of monuments to show our friends – which also serves to prove that we’ve actually made the trip. As Susan Sontag wrote in her essay ‘In Plato’s Cave’ (published in 1977 in the collection On Photography): ‘Recently, photography has become almost as widely practiced an amusement as sex and dancing – which means that, like every mass art form, photography is not practiced by most people as an art. It is mainly a social rite, a defense against anxiety, and a tool of power.’

Defending the Free Market: The Moral Case for a Free Economy

by

Robert A. Sirico

Published 20 May 2012

Could this be what the end of freedom looks like? One thing seems certain: something in our world is distracted, disordered, out of joint. We see it all around us and, if we are honest, we find it inside of ourselves as well. So much of the current political and economic debate is like the man in Plato’s cave, mistaking shadows for substance. Talking points are not a philosophy of life nor are they good governance. Strong currents are tugging at us, pulling us away from our moorings, pulling us away from a clear vision of a free and virtuous society—the one that the American Founders envisioned, and that we still hunger for.

Collider

by

Paul Halpern

Published 3 Aug 2009

Studying such excitations would yield valuable information about the size, shape, and other properties of the bulk. Finding evidence of extra dimensions isn’t one of the primary goals of the LHC. However, discovering unseen romping grounds beyond the view stands of our familiar arena would make particle physics a whole new game. Like Plato’s cave dwellers, we’d have to face the possibility that everything around us is a shadow of a greater reality. Yet if, on the other hand, visible space plus time make up all that there is, the quest for extra dimensions would ultimately prove futile. Theorists would need to concoct other explanations for why all the other forces are so much more potent than gravity.

Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle

by

Chris Hedges

Published 12 Jul 2009

The fame of celebrities, wrote Mills, disguises those who possess true power: corporations and the oligarchic elite. Magical thinking is the currency not only of celebrity culture, but also of totalitarian culture. And as we sink into an economic and political morass, we are still controlled, manipulated and distracted by the celluloid shadows on the dark wall of Plato’s cave. The fantasy of celebrity culture is not designed simply to entertain. It is designed to keep us from fighting back. “What Orwell feared were those who would ban books,” Neil Postman wrote:What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one.

Time Travel: A History

by

James Gleick

Published 26 Sep 2016

The physicist and historian Peter Galison puts it this way: “Where Einstein manipulated clocks, rods, light beams, and trains, Minkowski played with grids, surfaces, curves, and projections.” He thought in terms of the most profound visual abstraction. “Mere shadows,” Minkowski said. That was not mere poetry. He meant it almost literally. Our perceived reality is a projection, like the shadows projected by the fire in Plato’s cave. If the world—the absolute world—is a four-dimensional continuum, then all that we perceive at any instant is a slice of the whole. Our sense of time: an illusion. Nothing passes; nothing changes. The universe—the real universe, hidden from our blinkered sight—comprises the totality of these timeless, eternal world lines.

Uncanny Valley: A Memoir

by

Anna Wiener

Published 14 Jan 2020

We gathered on the couches in the center of the office, around a flat-screen television. The television was hooked up to a laptop, and most days, the engineers fed it content, silently streaming nature documentaries and recordings of strangers playing video games. Beers circulated. The CEO sat with his laptop open, working while he watched. The film was a transparent riff on Plato’s Cave, or so the internet said—I had never read Plato. It was also a delicious allegory for techno-libertarianism, and probably LSD. It was easy to see why the movie appealed. Canonically, what hackers accessed was the ability to surveil without consent. I knew the genuine thrill of watching a cross-section of society flow through a system, seeing the high-level, bird’s-eye view—the full map, the traffic, the stream of data pouring down the screen.

Big Data: A Revolution That Will Transform How We Live, Work, and Think

by

Viktor Mayer-Schonberger

and

Kenneth Cukier

Published 5 Mar 2013

Our current big-data world will, before long, look as quaint as the four kilobytes of writeable memory in Apollo 11’s guidance control computer does now. What we are able to collect and process will always be just a tiny fraction of the information that exists in the world. It can only be a simulacrum of reality, like the shadows on the wall of Plato’s cave. Because we can never have perfect information, our predictions are inherently fallible. This doesn’t mean they’re wrong, only that they are always incomplete. It doesn’t negate the insights that big data offers, but it puts big data in its place—as a tool that doesn’t offer ultimate answers, just good-enough ones to help us now until better methods and hence better answers come along.

The Doomsday Calculation: How an Equation That Predicts the Future Is Transforming Everything We Know About Life and the Universe

by

William Poundstone

Published 3 Jun 2019

The Omphalos Scenario How has the simulation hypothesis gained such intellectual currency? Does it merit being taken even a little seriously? The answer has to do with the self-sampling assumption, and with a set of beliefs ingrained in contemporary culture. The notion that the world could be an illusion is as old as philosophy. Plato’s cave, and all that. It was, however, an eminent Victorian, Philip Henry Gosse (1810–1888), who took Plato’s idea to the next level. Gosse was a naturalist who invented the aquarium and corresponded with Darwin on orchids. His 1857 book, Omphalos: An Attempt to Untie the Geological Knot, considers this puzzle: Did Adam and Eve have navels?

Death of the Liberal Class

by

Chris Hedges

Published 14 May 2010

This militarization, as Sheldon Wolin writes, combines with the cultural fantasies of hero worship and tales of individual prowess, eternal youthfulness, beauty through surgery, action measured in nanoseconds, and a dream-laden culture of ever-expanding control and possibility, to sever huge segments of the population from reality. Those who control the images control us. And while we have been entranced by the celluloid shadows on the walls of Plato’s cave, these corporate forces have effectively dismantled Social Security, unions, welfare, public health services, and public housing—the institutions of social democracy. They have been permitted to pollute the planet, long after we knew the deadly consequences of global warming. We are living through one of civilization’s seismic reversals.

Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It

by

Cory Doctorow

Published 6 Oct 2025

When members of the public complained to Googlers about how their carefully crafted websites were dispreferred by Google’s algorithm, the company line was simple: To get a higher ranking in Google search results, make a better page. The only way to increase your ranking was to improve the informative value of the thing you wanted ranked. It was as though Google believed that it had used a kind of obscure academic mathematical ranking to trace the location of Plato’s cave, and that it had installed a backward-facing camera at its firing line, staring directly at the true forms that cast the shadows on the cave wall. But for Google, the idea that its rankings were math and not judgment was a double-edged sword. Governments of the world are far more likely to defer to the free speech rights of someone expressing judgment than they are about someone solving an equation.

In Our Own Image: Savior or Destroyer? The History and Future of Artificial Intelligence

by

George Zarkadakis

Published 7 Mar 2016

The Scientist as Rebel

by

Freeman Dyson

Published 1 Jan 2006

“The gyroscope that guides a rocket is an emissary from a six-dimensional symplectic world into our three-dimensional one; in its home world its behavior looks simple and natural.” “Even those who see stars ask ‘What is a star?,’ because to see merely with one’s eyes is still very little.” “The image of Plato’s cave seems to me the best metaphor for the structure of modern scientific knowledge; we actually see only the shadows.” “In a world of light there are neither points nor moments of time; beings woven from light would live nowhere and nowhen; only poetry and mathematics are capable of speaking meaningfully about such things.”

Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation

by

Byrne Hobart

and

Tobias Huber

Published 29 Oct 2024

Roger Lowenstein, “The Villain,” The Atlantic, April 2012. 52 Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1994), 2. 53 Referring to the dichotomy between a real and a virtual economy, Baudrillard writes that “the sphere of virtual capital has become so autonomous, so orbitalized, that it can in some cases proliferate—or even devour itself—without leaving any trace… Between the two spheres [of the virtual and the real], there is no longer any communication… It is this break between the two, this loss of a referent on the part of the virtual economy, which enables it to produce prodigious effects, but it is also this which protects the real economy from the catastrophes which may occur in the other sphere.” Baudrillard, Screened Out (London: Verso Books, 2014), 22. 54 Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, 3. 55 While not a sound investing strategy, FOMO does play an important role in innovation-accelerating bubbles, as we’ll see in Chapter 2. 56 From Plato’s cave to Baudrillard’s simulacrum, there is a long tradition of philosophical attempts to escape the simulation. The German Hegelian anthropologist Ludwig Feuerbach, whose critique of Christianity later influenced Marx, Freud, and Nietzsche, anticipated the postmodern critique of simulacra and spectacle, writing, “But for the present age, which prefers the sign to the thing signified, the copy to the original, representation to reality, appearance to essence… truth is considered profane, and only illusion is sacred.

The Radical Fund: How a Band of Visionaries and a Million Dollars Upended America

by

John Fabian Witt

Published 14 Oct 2025

Lippmann began where his teacher Graham Wallas had left off. In modern societies, people come to know things not firsthand, but “second, third, or fourth hand.” “News,” Lippmann wrote, “comes from a distance.” Even worse, it “comes helter-skelter, in inconceivable confusion.”55 Lippmann likened modern citizens to the prisoners in Plato’s cave. We imagine that we understand the forms of things. But all the while we are merely boxing with shadows—with the derivative image of the real thing. As Lippmann put it, the complexity and scale of the modern world create an ever-growing gap between “the world outside and the pictures in our heads.”

…

“institutions”: Walter Lippmann to Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Nov. 18, 1919, in Public Philosopher: Selected Letters of Walter Lippmann, ed. John Morton Blum (Ticknor & Fields, 1985), 132–33. “can prevail”: Walter Lippmann, Liberty and the News (Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1920), 71. 55. “second, third”: Lippmann, “Basic Problem of Democracy,” 620. 56. Plato’s cave: Lippmann, Public Opinion, vii. “world outside”: Ibid., 3. “messengers”: Lippmann, Liberty and the News, 85. “habitual viewpoints”: Lippmann, “Basic Problem of Democracy,” 623. “catchwords”: Ibid., 620. “stereotypes”: Lippmann, Liberty and the News, 54–55. “buzzing confusion”: Ibid., quoting William James, The Principles of Psychology, vol. 1 (Henry Holt, 1913), 488.

The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window Into Human Nature

by

Steven Pinker

Published 10 Sep 2007

Any inventory of human nature is bound to cause some apprehension in hopeful people, because it would seem to set limits on the ways we can think, feel, and interact. “Is that all there is?” one is tempted to ask. “Are we doomed to picking our thinkable thoughts, our feelable feelings, our possible moves in the game of life, from a short menu of options?” It is an anxiety that goes back to Plato’s famous allegory of the prisoners in the cave. Captives are shackled in a grotto, their heads and bodies chained so that they can look only at the rear wall. The cave is a kind of movie theater out of The Flintstones, with a fire behind a balcony on which projectionists hold up cutouts and puppets, which cast moving shadows onto the wall.

…

menstruation, taboo words and mental imagery metaphors abstract concepts expressed in all metaphors as dead body terms for place and direction dead importance of as key to explaining thought and language mixed in neologisms space for time ubiquity of see also conceptual metaphors; literary metaphors Metaphors We Live By (Lakoff and Johnson) Metcalfe, Alan metonymy Michelangelo Michotte, Albert microclasses, semantic middlemen middle voice Miller, Jonathan mind-body dualism minorities: African Americans epithets for Jews and middlemen nouns for momentaneous verbs monkeys Monroe, Marilyn Montagu, Ashley Monty (comic) Monty Python’s Flying Circus morality: causality and intentionality and responsibility Kantian categories and Morning Star morphemes morphology Morrison, Philip and Phyllis motherfucker moving observer and moving time metaphors Mundurukú Murphy, Gregory mutualism mutual knowledge My Fair Lady Nabokov, Vladimir Naked and the Dead, The (Mailer) names, personal fashion cycles for meaning of naming children semantics of see also proper names Nativism, Extreme, see Extreme Nativism natural kinds nature-nurture debate necessity negative evidence negative exceptions negative space neocortex neologisms methods of forming Neologizing Imperative Retort Newell, Allen Newtonian physics New Yorker magazine New York Times Nietzsche, Friedrich nigger 9/11 Nisbett, Richard nominal kinds nouns from adjectives compounding in literary metaphors polysemy and stereotypes turning into verbs see also common nouns; proper names number (grammatical) number (quantity) Nunberg, Geoffrey Nyhan, David oaths object-centered frame objectivity obscenity see also swearing (taboo language) obsessive-compulsive disorder Oedipus Oh-Shit Wave on onomatopoeia Orwell, George Ose, Doug Page, Larry paint paintbrushes Papafragou, Anna Papuan language Parker, Dorothy passive voice past past tense perfective aspect perfect tense Peterson, Scott philosophy: of causality epistemology of language and Linguistic Determinism of meaning moral of names of science Western phonesthesia phonetic symbolism phonological loop physics: intuitive Newtonian quantum relativity and space and time Piatelli-Palmarini, Massimo Pica, Pierre Pile ’Em High Pirahã piss planets Plato’s allegory of the cave plausible deniability pluperfect tense plural nouns Pluto podcast poetic devices politeness cultural differences in deferential as human universal indirect (polite) requests and intellectual consensus sympathetic Politeness Theory political debate: framing in metaphor in polysemy reasoning not affected by of spatial terms Pöppel, Ernst Porter, Cole portmanteau words Portnoy’s Complaint (Roth) Portuguese language possession possessor-raising construction possible worlds Potter, Stephen Potts, Christopher power Powers of Ten pragmatics see also implicature; indirect speech; politeness; Radical Pragmatics predicating versus referring prefixes prenuptial agreements prepositional dative prepositions Presley, Elvis present specious present progressive tense present tense priming probabilistic theories of causality problem isomorphs profanity, see swearing (taboo language) Project Steve promises pronouns: second-person third-person proper names: brand names indexicals compared with meaning of as rigid designators treated as common nouns see also names, personal Proust, Marcel Provine, Robert Pullum, Geoffrey pussy Pustejovsky, James Putnam, Hilary Pygmalion (Shaw) Quang Fuc Dong quantum mechanics Québecois French language queer Quine, W.

Roads to Berlin

by

Cees Nooteboom

and

Laura Watkinson

Published 2 Jan 1990

If he was impatient, you could only tell from his fingers, which occasionally started drumming, as though they had escaped the control of headquarters. Women in the crowd pointed at him, pointed him out to one another, laughed, sometimes ecstatically; you could see it happening, in wave after wave. The others—government, Politburo—were grouped around the two leaders. The figures in the back row had no faces, were mere outlines, shadows from Plato’s cave. In the spring, one of the men had been in the West, where he was applauded as he was now in the East. Back then, for one brief moment, as he stood waving in a car, he had looked like someone who was certain that he had achieved something: he had surrounded the D.D.R. His own country, Poland, Hungary and the West had combined forces to draw a merciless ring around the D.D.R.

Catch and Kill: Lies, Spies, and a Conspiracy to Protect Predators

by

Ronan Farrow

Published 14 Oct 2019

That chance encounter with Oppenheim eventually led him from conservative punditry to producing on MSNBC, and then to a senior producer role on Today. But he always had wider ambitions. He co-authored a series of self-help books called The Intellectual Devotional (“Impress your friends by explaining Plato’s Cave allegory, pepper your cocktail party conversation with opera terms,” read the jacket copy) and boasted that Steven Spielberg had given them out as holiday gifts, “so now I can die happy.” In 2008, he left the network and moved his family to Santa Monica to pursue a career in Hollywood. Referring to journalism, he said, “I had an amazing experience through my 20s doing that but had always loved the movie business, and movies, and drama.”

Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks From the Stone Age to AI

by

Yuval Noah Harari

Published 9 Sep 2024

But for thousands of years humans have been haunted by a much deeper fear. We have always appreciated the power of stories and images to manipulate our minds and to create illusions. Consequently, since ancient times humans have feared being trapped in a world of illusions. In ancient Greece, Plato told the famous allegory of the cave, in which a group of people are chained inside a cave all their lives, facing a blank wall. A screen. On that screen they see projected various shadows. The prisoners mistake the illusions they see there for reality. In ancient India, Buddhist and Hindu sages argued that all humans lived trapped inside maya—the world of illusions.

…

People may wage entire wars, killing others and willing to be killed themselves, because of their belief in this or that illusion. In the seventeenth century René Descartes feared that perhaps a malicious demon was trapping him inside a world of illusions, creating everything he saw and heard. The computer revolution is bringing us face to face with Plato’s cave, with maya, with Descartes’s demon. What you just read might have alarmed you, or angered you. Maybe it made you angry at the people who lead the computer revolution and at the governments who fail to regulate it. Maybe it made you angry at me, thinking that I am distorting reality, being alarmist, and misleading you.

When Einstein Walked With Gödel: Excursions to the Edge of Thought

by

Jim Holt

Published 14 May 2018

Could such worlds ever be visualized by the human imagination? What would it be like to exist in one? Was it just an accident that among all the possible spatial architectures we find ourselves living in a world of three dimensions? Or—an even more heady thought—could it be that we do live in a world with more dimensions, but like the prisoners in Plato’s cave we are too benighted to realize it? “A person who devoted his life to it might perhaps eventually be able to picture the fourth dimension,” wrote Henri Poincaré in the late nineteenth century. He made the task seem rather daunting, but maybe that is because, as a mathematician of peerless spatial intuition himself, he had very high standards.

The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion

by

Jonathan Haidt

Published 13 Mar 2012

Martha Nussbaum (2004) has made this case powerfully, in an extended argument with Leon Kass, beginning with Kass 1997. 24. Popes Benedict XVI and John Paul II have been particularly eloquent on these points. See also Bellah et al. 1985. 25. For example, the Hindu veil of Maya; the Platonic world of Forms and the escape from Plato’s cave. 26. According to data from the American National Election Survey. Jews are second only to African Americans in their support for the Democratic Party. Between 1992 and 2008, 82 percent of Jews identified with or leaned toward the Democratic Party. 27. As I’ll say in chapter 8, it is only recently that I’ve come to realize that conservatives care at least as much about fairness as do liberals; they just care more about proportionality than about equality. 28.

The Attention Merchants: The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads

by

Tim Wu

Published 14 May 2016

Unlike our day of always-on Internet, back then one “jacked in” or perhaps passed through the back of the family wardrobe, and under a made-up name entered an entirely different kind of world populated by strangers, one where none of the usual rules applied. “Imagine,” said the cyber-pioneer John Perry Barlow, “discovering a continent so vast that it may have no end to its dimensions…where only children feel completely at home, where the physics is that of thought rather than things, and where everyone is as virtual as the shadows in Plato’s cave.”4 It was pretty cool stuff for the 1990s, intriguing enough to get AOL and the early web its first user base. In retrospect, however, the concept had its limitations. For one thing, once the novelty wore off, online content was circumscribed by the imagination of its users; that makes it sound unlimited, but in practice that wasn’t the case.

Jihad vs. McWorld: Terrorism's Challenge to Democracy

by

Benjamin Barber

Published 20 Apr 2010

Imagine imagination without words: does it ennoble or debase? Or simply cease to exist? Imagine an ontology, a science of the real, conceived in cyberspace: reality itself is transmuted into a virtual cousin, a species of the extant consisting in equal parts of pretense, illusion, and deception. Virtuality displaces reality, and Plato’s Cave, where flickering shadows dancing on a smoky wall are our only clue to the “real,” becomes the whole of our world. Words open the soul’s window to ideas and the discourse of words is how we grope our way to conversation and, when conversation can be stripped of its inequalities and hidden hegemonies, how we eventually become capable of cooperation, of common life with others, and even of justice.

The Mole People: Life in the Tunnels Beneath New York City

by

Jennifer Toth

Published 14 Jun 1993

How to Do Nothing

by

Jenny Odell

Published 8 Apr 2019

“Let your life be a counter friction to stop the machine.”29 Like Plato with his allegory of the cave, Thoreau imagines truth as dependent on perspective. “Statesmen and legislators, standing so completely within the institution never distinctly and nakedly behold it,” he says. One must ascend to higher ground to see reality: the government is admirable in many respects, “but seen from a point of view a little higher they are what I have described them; seen from a higher still, and the highest, who shall say what they are, or that they are worth looking at or thinking of at all?” As for Plato, for whom the escapee from the cave suffers and must be “dragged” into the light, Thoreau’s ascent is no Sunday stroll in the park.

Galileo's Dream

by

Kim Stanley Robinson

Published 29 Dec 2009

SMITH, Psychoanalytic Roots of Patriarchy BLACK SPACE, the dense spangle of stars. The great bulk of Jupiter, almost entirely sunlit, surreally present to the eye, crawling phyllotaxically with its hundreds of colors and thousands of convolutions— He was sitting in his chair in Hera’s little space boat, which was again rendered invisible—a kind of Plato’s cave through which the cosmos poured in. Below and behind them, the virulent ball that was Io jumped out of the starry blackness. “You’re back,” she noted. Her teletrasporta lay on the floor beside his chair. “Good.” “Where are you going?” he asked. “To Europa, of course.” She looked at him. “We’re still trying to keep Ganymede and his people away.”

A History of Western Philosophy

by

Aaron Finkel

Published 21 Mar 1945

For he says: “Ah, woe is me that the pitiless day of death did not destroy me ere ever I wrought evil deeds of devouring with my lips! … “Abstain wholly from laurel leaves … “Wretches, utter wretches, keep your hands from beans!” So perhaps he had done nothing worse than munching laurel leaves or guzzling beans. The most famous passage in Plato, in which he compares this world to a cave, in which we see only shadows of the realities in the bright world above, is anticipated by Empedocles; its origin is in the teaching of the Orphics. There are some—presumably those who abstain from sin through many incarnations—who at last achieve immortal bliss in the company of the gods: But, at the last, they* appear among mortal men as prophets, song-writers, physicians, and princes; and thence they rise up as gods exalted in honour, sharing the hearth of the other gods and the same table, free from human woes, safe from destiny, and incapable of hurt.

…

Therefore the Creator, it would seem, created only illusion and evil. Some Gnostics were so consistent as to adopt this view; but in Plato the difficulty is still below the surface, and he seems, in the Republic, to have never become aware of it. The philosopher who is to be a guardian must, according to Plato, return into the cave, and live among those who have never seen the sun of truth. It would seem that God Himself, if He wishes to amend His creation, must do likewise; a Christian Platonist might so interpret the Incarnation. But it remains completely impossible to explain why God was not content with the world of ideas.

…

Peter Damian, 413 and the Schoolmen, 388–487 in 12th cent., 428–441 in 13th cent., 441–451 two periods of, 303 Catholic vote, 332 Catholicism, 685, 811–812 Catholics, 617–618, 690 emphasize the Church, 346 Cato, Marcus Porcius (the Elder), Roman general and patriot (234–149 B.C.), 236–238, 278, 314, 357 causal laws in physics, 669 causality, causation, 66, 658, 673–674, 717 and Hume, 663, 664–671, 702, 704, 707 and Kant, 715 cause-and-effect, 708 cause(s): and belief, 817, 826 and Aristotle, 169, 182 and Francis Bacon, 543 and Newton, 539 and Plato, 145. See also final cause First Cause prime causes cave, Plato’s, 57, 105, 124, 125–126, 130 Cebes, Greek philosopher (fl. 5th cent, B.C.), 138, 140 Cecil, Sir William (Lord Burghley), English statesman (1520–1598), 541 Cecrops, 265 celibacy, 134, 348, 459 of clergy, 112, 410, 413, 415 Celsus, Roman Platonist philosopher and anti-Christian writer (fl. 2nd cent.), 327–328 censorship, 835 Cephalus, 117 Chalcedon, 116 Council of, 333, 369, 374 Chaldeans, 227, 252 Chalons, 367, 369 Chamber of Deputies (France), 639 chance, 55, 58, 63, 66, 254 change(s), 46, 47, 61, 55, 56, 57, 68 and Bergson, 804–806 denied by Eleatics, 805 and Heraclitus, 43, 45, 48, 805 mathematical conception of, 804, 805, 806 and Parrnenides, 48, 51, 52, 105 and Plato, 105, 143, 158–159.

The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail-But Some Don't

by

Nate Silver

Published 31 Aug 2012

“Strange therefore . . . because he only sees the lowest part of this scale, [he] should from hence infer a defeat of happiness in the whole,” Bayes wrote in response to another theologian.23 Bayes’s much more famous work, “An Essay toward Solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances,”24 was not published until after his death, when it was brought to the Royal Society’s attention in 1763 by a friend of his named Richard Price. It concerned how we formulate probabilistic beliefs about the world when we encounter new data. Price, in framing Bayes’s essay, gives the example of a person who emerges into the world (perhaps he is Adam, or perhaps he came from Plato’s cave) and sees the sun rise for the first time. At first, he does not know whether this is typical or some sort of freak occurrence. However, each day that he survives and the sun rises again, his confidence increases that it is a permanent feature of nature. Gradually, through this purely statistical form of inference, the probability he assigns to his prediction that the sun will rise again tomorrow approaches (although never exactly reaches) 100 percent.

The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect

by

Judea Pearl

and

Dana Mackenzie

Published 1 Mar 2018

Yet it hinders learning systems that operate in environments governed by rich webs of causal forces, while having access merely to surface manifestations of those forces. Medicine, economics, education, climatology, and social affairs are typical examples of such environments. Like the prisoners in Plato’s famous cave, deep-learning systems explore the shadows on the cave wall and learn to accurately predict their movements. They lack the understanding that the observed shadows are mere projections of three-dimensional objects moving in a three-dimensional space. Strong AI requires this understanding. Deep-learning researchers are not unaware of these basic limitations.

A Mathematician Plays the Stock Market

by

John Allen Paulos

Published 1 Jan 2003

With blackjack, however, there is a compelling mathematical explanation for those who care to study it. By contrast an effective technical trading strategy might be found that was beyond the comprehension not only of the people using it but of everyone. It might simply work, at least temporarily. In Plato’s allegory of the cave the benighted see only the shadows on the wall of the cave and not the real objects behind them that are causing the shadows. If they were really predictive, investors would be quite content with the shadows alone and would simply take the cave to be a bargain basement. The next segment is a bit of a lark.

The End of Absence: Reclaiming What We've Lost in a World of Constant Connection

by

Michael Harris

Published 6 Aug 2014

The Kaiser Foundation’s latest numbers tell us that print consumption, outside of reading for school, takes up an average of thirty-eight minutes in every youth’s day (a small but telling drop from forty-three minutes five years earlier). 5. This is, yes, a hyped-up Hollywood version of Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave.” 6. To “an hero” is a synonym for committing suicide that is used by 4chan communities. 7. The gold medal has not been won yet. Smaller prizes are given each year for the “most human computer” in the bunch. 8. Such content will almost definitely be managed more tightly in the future than it is now—perhaps by the government.

Hyperion

by

Dan Simmons

Published 15 Sep 1990

Thus, on Heaven’s Gate, as I dredged bottom scum from the slop canals under the red gaze of Vega Primo or crawled on hands and knees through stalactites and stalagmites of rebreather bacteria in the station’s labyrinthine lungpipes, I became a poet. All I lacked were the words. The twentieth century’s most honored writer, William Gass, once said in an interview; ‘Words are the supreme objects. They are minded things.’ And so they are. As pure and transcendent as any Idea which ever cast a shadow into Plato’s dark cave of our perceptions. But they are also pitfalls of deceit and misperception. Words bend our thinking to infinite paths of self-delusion, and the fact that we spend most of our mental lives in brain mansions built of words means that we lack the objectivity necessary to see the terrible distortion of reality which language brings.

Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age

by

W. Bernard Carlson

Published 11 May 2013

I have borrowed this tension from the allegory of the cave found in The Republic by Plato.15 Plato developed this allegory to illustrate the difference between ignorance and enlightenment, between how ordinary people and philosophers perceived the world and truth. To explain how ordinary people had a limited understanding of the truth, Plato imagined a group of individuals trapped in the cave who were shackled to chairs and their heads locked in braces so they could not turn around and see how light (or truth) came into the cave. Trapped in this way, they spent their lives debating the flickering shadows projected on the wall by people and things passing in front of a fire behind them.

12 Bytes: How We Got Here. Where We Might Go Next

by

Jeanette Winterson

Published 15 Mar 2021

That is the world in our heads – because those are the worlds we live in – but it is also a chance at touching or glimpsing what might be the substance, and not the shadow. Physics is working on the same problems but using other methods. What else was Shakespeare talking about in his beautiful Sonnet 53? What is your substance, whereof are you made, That millions of strange shadows on you tend? Plato’s famous image of the cave, with its shadows on the wall, and its fire mistaken for the sun, isn’t so different from the Hindu, or later the Buddhist, insight into the delusional nature of the reality we take for granted. Plato, though, believed that the human soul is immortal – that it can think after death, know itself, live without its body, and will return.

The Human Cosmos: A Secret History of the Stars

by

Jo Marchant

Published 15 Jan 2020

Being You: A New Science of Consciousness

by

Anil Seth

Published 29 Aug 2021

As with the Copernican revolution, this top-down view of perception remains consistent with much of the existing evidence, leaving unchanged many aspects of how things seem, while at the same time changing everything. This is by no means a wholly new idea. The first glimmers of a top-down theory of perception emerge in ancient Greece, with Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Prisoners, chained and facing a blank wall all their lives, see only the play of shadows cast by objects passing by a fire behind them, and they give the shadows names, because for them the shadows are what is real. The allegory is that our own conscious perceptions are just like these shadows, indirect reflections of hidden causes that we can never directly encounter.

The Quiet Damage: QAnon and the Destruction of the American Family

by

Jesselyn Cook

Published 22 Jul 2024

Be well mom, I’m sorry. 8 SHADOW PLAY —Alice— Deep inside an underground cave, prisoners sit shoulder to shoulder, chained to a partition at their backs. They’ve lived down there from infancy. Above, unseen, their captors use flames and puppets to cast shadow figures onto the wall ahead. To the prisoners, these illusions are real—the only reality they’ve ever known. So begins Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. One day, a single prisoner is unshackled. He’s made to turn around and witness the fiery masquerade over the partition, then he’s taken up out of the cave into the blazing sunlight. It overwhelms and temporarily blinds him. But eventually his eyes adjust. And for the very first time, he sees the world as it truly is, in all its brilliant color and depth and detail.

The Reckoning: Financial Accountability and the Rise and Fall of Nations

by

Jacob Soll

Published 28 Apr 2014

Cosimo was a man of two worlds, for he had one foot in the Middle Ages and the other in the Renaissance, which he helped invent. Although some Neo-Platonists saw all formal knowledge as an element of holiness, others believed that some learning was inferior and beneath the interest of the noble, Platonic elite. Merchant and noble values began to clash. Plato’s allegory of the cave, which described a lower cave people being ruled by an intellectual elite who through the wisdom of their souls sought the good of the republic, was a model not only for secular education and culture but also for political elitism.18 The Neo-Platonic ideal of human glory based on artistic, cultural, and political achievement did not always leave a place for the gritty practical matters of business.

The Transformation Of Ireland 1900-2000

by

Diarmaid Ferriter

Published 15 Jul 2009

Their labours revealed the extent to which many of the ‘pillars’ of Irish society – including the Church, the controllers of state power and the family – had not been scrutinised sufficiently. They also exposed the degree to which, despite the attention given to cultural studies, modernity and national identity, the analysis of class and economic issues had been neglected. It also seemed that many of the labels associated with particular years of Irish history – ‘Plato’s cave’ (the period of the Second World War), ‘The decade of the vanishing Irish’ (the 1950s) and the ‘Best of decades’ (the 1960s)1 – were not satisfactory in the light of ongoing research and newly available sources, while there was still a tendency to begin general histories of Ireland in the twentieth century between the years of 1912 and 1922 rather than in 1900.

The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer

by

Siddhartha Mukherjee

Published 16 Nov 2010

The Age of AI: And Our Human Future

by

Henry A Kissinger

,

Eric Schmidt

and

Daniel Huttenlocher

Published 2 Nov 2021

The emerging AI age is increasingly posing epochal challenges to today’s concept of reality. In the West, the central esteem of reason originated in ancient Greece and Rome. These societies elevated the quest for knowledge into a defining aspect of both individual fulfillment and collective good. In Plato’s Republic, the famed allegory of the cave spoke to the centrality of the quest. Styled as a dialogue between Socrates and Glaucon, the allegory likens humanity to a group of prisoners chained to the wall of a cave. Seeing shadows cast on the wall of the cave from the sunlit mouth, the prisoners believe them to be reality.

Kissinger: A Biography

by

Walter Isaacson

Published 26 Sep 2005

“I’ve only been able to change a few places in the vicinity of Beijing,” Mao replied. Rather than discoursing on his worldview, Mao conveyed his thoughts through a bantering Socratic dialogue that guided his guests, with deceptive casualness, toward his conclusions. His elliptical comments seemed to Kissinger like the shadows on the wall of Plato’s cave, in that they reflected reality but did not encompass it. For the rest of the week, Chinese officials would cite Mao’s phrases from the hour-long meeting as being concrete guidance verging on gospel. The most important matter of substance, or so almost everyone thought, was Taiwan. In his elliptical fashion, Mao opened the way to a resolution by noting a truth so obvious that others had ignored it: Taiwan was not, in fact, the most important matter of substance between the two nations.

The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in an Age of Distraction

by

Matthew B. Crawford

Published 29 Mar 2015

If they prevailed, they trickled down and settled as articles of faith, or cultural reflexes. One must deploy sharp implements to clear these away and recover a more immediate intelligibility to life. Philosophizing politically is not something you do only after you have figured things out, like Plato’s philosopher returning to the cave. It is how you figure things out to begin with. AN OVERVIEW OF THE ARGUMENT In the course of thinking about attention, we found that we had to reconsider the boundaries of the self through the idea of cognitive extension. As embodied beings who use tools and prosthetics, the world shows up for us through its affordances; it is a world that we act in, not merely observe.

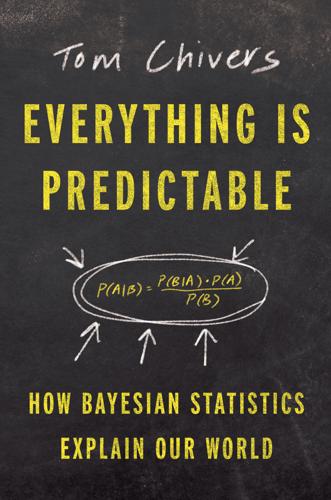

Everything Is Predictable: How Bayesian Statistics Explain Our World

by

Tom Chivers

Published 6 May 2024

Our perception is the commingling of that bottom-up stream with the top-down one. The two constrain each other—if the top-down priors are strong, then it requires precise, strong evidence from the senses to overturn them. Scholars have wondered how we perceive the world for thousands of years. Plato’s famous allegory of the cave is about perception. Prisoners are chained up in a cave, facing a wall on which the shadows of a puppet play are cast by a fire behind them. The prisoners, who have never seen anything else, think the shadows are reality, and give names to the shadows.1 For Plato, our perception of the world is like that: we don’t see reality as it is, but a shadow of it, mediated through our senses.

The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life

by

Alice Schroeder

Published 1 Sep 2008

In Security Analysis, Principles, and Technique (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1934), Benjamin Graham and Dodd stressed that there is no single definition of “intrinsic value,” which depends on earnings, dividends, assets, capital structure, terms of the security, and “other” factors. Since estimates are always subjective, the main consideration, they wrote—always—is the margin of safety. 16. The apt analogy to Plato’s cave was originally made by Patrick Byrne. 17. Often this was because the kind of undervalued stocks he liked were illiquid and could not be purchased in large positions. But Buffett felt that Graham could have followed a bolder strategy. 18. Interview with Jack Alexander. 19. Interview with Bill Ruane. 20.

The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World's Most Popular Drug

by

Bennett Alan Weinberg

and

Bonnie K. Bealer

Published 5 Dec 2000

In the dialectic of Socrates, the goal was similar: to treat of the ordinary aspects of life with the hope of achieving an understanding beyond imagination (eikasia), sense perception (pistis), and even reason (dianoia), to reach an intuitive understanding of the Forms, the illumination of the soul that Plato called noesis. Like the Bodhisattva of Buddhist tradition, who after his enlightenment returns from the Void to lead his fellow creatures on the Path away from suffering, the philosopher of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, after escaping to see the world illuminated by the light of the Good, returns to teach the way of liberation to his still ignorant compatriots. (Plato does not use these four words for the degrees of knowing consistently throughout the Republic. However, this is the scheme he sets up to accompany the Allegory of the Cave.) 5.

Cosmos

by

Carl Sagan

Published 1 Jan 1980

The Pythagoreans delighted in the certainty of mathematical demonstration, the sense of a pure and unsullied world accessible to the human intellect, a Cosmos in which the sides of right triangles perfectly obey simple mathematical relationships. It was in striking contrast to the messy reality of the workaday world. They believed that in their mathematics they had glimpsed a perfect reality, a realm of the gods, of which our familiar world is but an imperfect reflection. In Plato’s famous parable of the cave, prisoners were imagined tied in such a way that they saw only the shadows of passersby and believed the shadows to be real—never guessing the complex reality that was accessible if they would but turn their heads. The Pythagoreans would powerfully influence Plato and, later, Christianity.

The Voice of Reason: Essays in Objectivist Thought

by

Ayn Rand

,

Leonard Peikoff

and

Peter Schwartz

Published 1 Jan 1989

Sickening: How Big Pharma Broke American Health Care and How We Can Repair It

by

John Abramson

Published 15 Dec 2022

When applied to publications reporting the results of commercially funded clinical research, the source of most of the scientific evidence doctors rely on, the techniques of EBM mask the lack of transparency of the data that remain below the waterline. Looked at another way, when the discipline of EBM is combined with the falsely empowering belief that the skills of EBM allow full evaluation of published research, doctors are placed in much the same predicament as the prisoners in Plato’s allegory — chained in a dark cave, mistaking the shadows cast on the cave wall in front of them for reality. Well-meaning doctors mistakenly assume that the reports of clinical studies in peer-reviewed medical journals are accurate and complete distillations of study data; they are unaware that the published results are incompletely vetted, often commercially biased selections from the totality of data.

In Covid's Wake: How Our Politics Failed Us

by

Stephen Macedo

and

Frances Lee

Published 10 Mar 2025